1. Introduction

With the rapid population growth and the development of energy-intensive technologies, the consumption of energy is rapidly increasing in the world. The excessive usage of traditional energy sources such as natural gas, fossil fuels and coal results in serious global climate changes and pollution. Thus, the exploration and development of renewable and clean energy, such as solar and wind power, are being driven by researchers and engineers [

1]. Due to the intermittent nature of these renewables, novel devices for energy storage with superior performance and excellent reliability are urgently necessary to meet the growing energy requirement, including fuel cells, lithium and sodium batteries, aqueous Zn-ion batteries, as well as supercapacitors [

2]. These devices are expected to have not only large energy densities but also high specific power [

3]. Among these devices, supercapacitors (SCs), also called electrochemical capacitors, have been intensively investigated because of their many advantages, with the distinctive features of fast charging and discharging rate, as well as long cycle life [

4].

SCs have drawn much attention from researchers because of the increasing energy consumption in many fields from large to small scale devices such as electric vehicles and portable devices, etc. They have capability to bridge short-term power fluctuations and provide rapid charge-discharge cycles [

5]. The structure of SCs is primarily comprised of three components, i.e. electrodes, separators, and electrolytes [

6]. The general performance of SCs hinges on the basic properties of the electrode materials. Due to with the different mechanism of energy storage, SCs can be easily classified into three types, i.e., pseudo-capacitors, electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs), and hybrid SCs [

7]. Pseudo-capacitors store energy through reversible charge transport between the interfaces of electrode and electrolyte companied by redox chemical reactions [

8], while EDLCs store charges by physically electrostatic ion adsorption, thus enabling quick charging/discharging rates [

9]. A hybrid capacitor means that it is composed of two electrodes (for example EDLC and pseudocapacitor) with different potential windows to obtain a wider operation voltage and a higher energy density than any single one. Thus, many attempts have been made to enhance the electrochemical performance of SCs through modification or designing novel electrode materials.

Since the performance of SCs strongly depends on advanced electrode materials, it is widely accepted that a porous structure with a large specific surface area and a high conductivity of electrode materials is beneficial for rapid charge transfer. Thus, a variety of carbon materials with rich resources, abundant pores, diverse structures, and good conductivity are popularly employed as electrode materials of SCs [

10]. Meanwhile, an electrode material derived from biomass materials is of interest in the research regarding green and sustainable development concepts. Thus, biomass-derived carbon (BDC) is a new kind of environmentally friendly carbon material that has well-developed and easy controlled structures [

11]. Compared with traditional high-cost precursors from industry products to prepare carbon materials, the pyrolysis method using renewable biomass precursors as sources can obtain much cheaper BDC for energy storage fields, and the by-product gases can be readily used for power generation [

12]. To prepare carbon materials for SCs, it is more sustainable than the conventional route [

13].

Currently, a variety of biomass sources – including plants, animals, and microorganisms – have been reported as practical precursors of BDC for SCs electrodes [

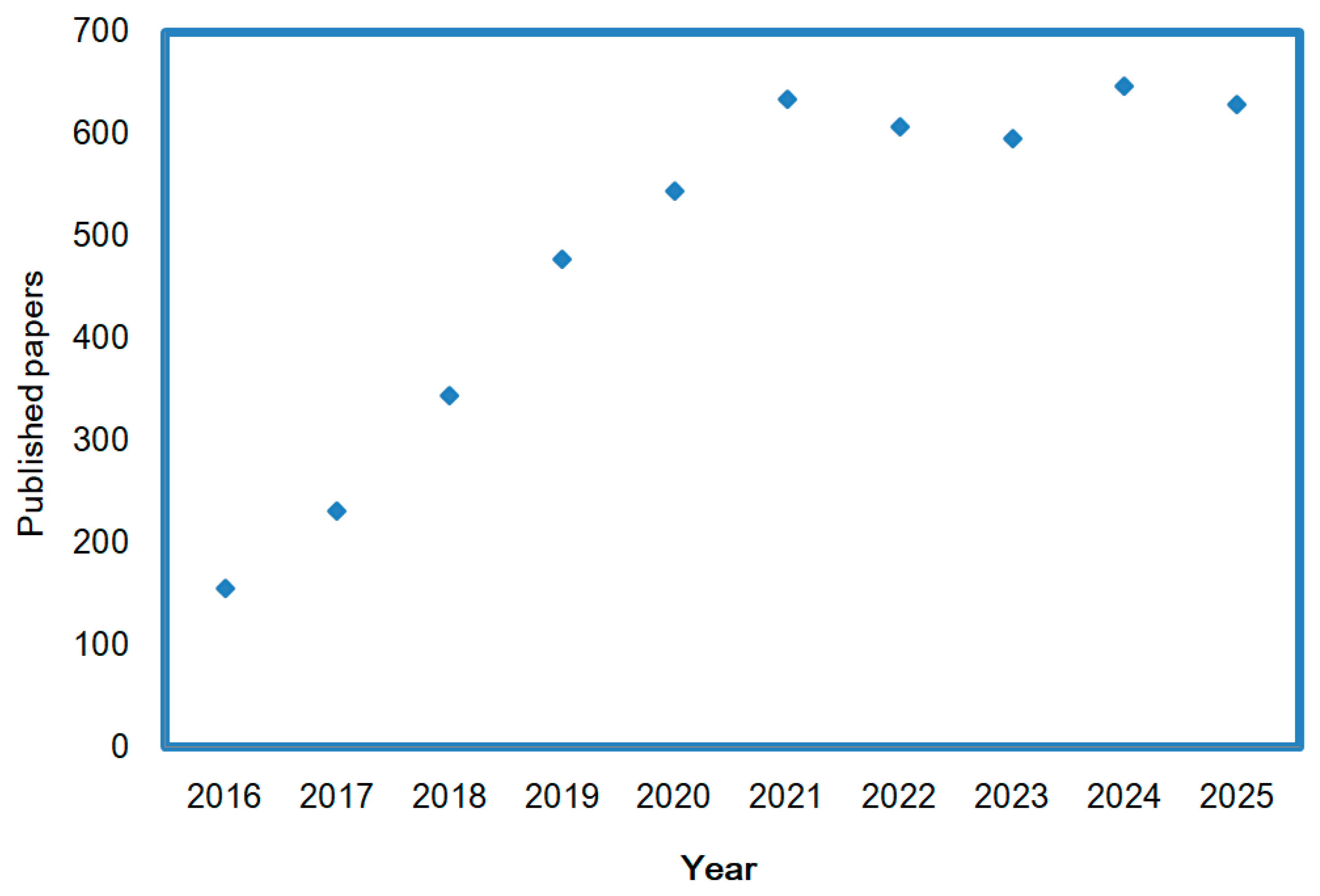

14]. As per Web of Science, the trend of recently published papers on the topics of SCs and biomass-based carbon from 2016 to 2025 is exhibited in

Figure 1. It is shown that SCs related to BDC have been a continuous area of interest, with ongoing research focusing on the electrolyte materials. Meanwhile, there are also many comprehensive review papers related to BDC for energy storage [

15,

16,

17]. As a simple review, the main attention of this work will focused on the latest reports during the last three years from 2023 to 2025. We hope to provide researchers better understanding on the recent progress and challenges, uncovering the possible research direction in future.

2. Energy Storage Mechanism of Supercapacitors

2.1. Pseudocapacitors

For SCs, the term of “pseudocapacitance” is closely related to surface redox reactions and the capacitive effect can be easily observed by analyzing the cyclic voltammetric curves [

18]. Previously, ruthenium oxide was the subject of in-depth research as a very promising electrode material for pseudocapacitors. It applies Faradaic electro-sorption, intercalation, and oxidation-reduction processes to realize charge storage. At the electrode surface and adjacent regions, the active electrode materials and the electrolytes have rapid and reversible redox reactions. Pseudocapacitors strongly rely on high-energy electrode materials that can be metal compounds (oxides, hydroxides or sulfides) and conducting polymers. Although pseudocapacitors can usually demonstrate a significantly higher specific capacitance than EDLCs, the electrode of pseudocapacitors may suffer from volume changes during the rapid charge/discharge cycles, thus leading to reduced cycling life, poor rate capability and mechanical stability.

2.2. EDLC Capacitors

Different from pseudocapacitors, EDLCs can store energy at the interface between electrode and electrolyte through physical adsorption of ions, thus forming an electrical double layer, which involves fast and highly reversible physical processes [

19]. The energy storage of EDLCs is based on the intrinsic shell area and atomic charge partition length. Thus, it can make the SCs suitable for typical applications requiring high power density. Since there is not any electrochemical reaction, EDLCs have a rather lower safety risk than lithium-ion batteries. Thus, its energy density is much lower than that of lithium-ion batteries.

For ELDCs, during the charging process, the ions in electrolyte are attached to electrodes to generate an electric double layer on the surface. When discharging, the stored charge is released when ions move back into the electrolyte. If the surface area of the electrode is larger, then more charge can be stored on it. During the past decades, researchers thus thought that the best method to increase the specific capacitance of EDLCs was to increase the specific surface area of electrode materials, and that activated carbon (AC) was still the most widely used electrode material for EDLCs because of its high surface area and low cost. AC materials are usually obtained from carbon-rich organic precursors through a heat treatment in an inert atmosphere or thermal pyrolysis (carbonization), followed with an activation process to generate abundant porosity [

20]. To carbonize biomass materials, pyrolysis carbonization and hydrothermal carbonization are two commonly used methods. Pyrolysis is performed in an inert or limited oxygen atmosphere at elevated temperatures. The hydrothermal process yields a partially carbonized product, called hydrochar, which has a high density of oxygen-containing groups, a low degree of condensation, and poorly developed porosity with a low specific surface area. The activation process can make bio-char exhibit a larger specific surface area and more developed pores, where environmentally friendly physical activation with steam, air or CO

2 and complicated chemical activation by alkalis, salts and acids are usually involved. Among various kinds of activation reagents, KOH is the most wildly used chemical. However, the combined carbonization and activation (one-pot) process can be also performed, as reported elsewhere [

21]. AC precursors can be natural renewable resources, such as wood, plants, fossil fuels and their derivatives such as pitch or coal, or synthetic polymers.

Certain key characteristics from AC must be closely concerned, because they basically determine the electrochemical properties, such as pore size distribution, specific surface area, electrical conductivity, and integration with the electrolyte. The future development of carbon-based SC electrodes will increasingly depend on the sustainability and renewability goals. Compared with the synthetic and non-renewable precursors, biomass-based AC can offer more sustainable and scalable options for SC electrodes with much lower prices.

3. Various Sources of Biomass-Derived Carbon Precursors

Biomass precursors for AC mainly include plants, animal bones and excreta, as well as microorganisms, in which most substance can be used to prepare porous carbon materials due to its high carbon content.

Plants, predominantly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, are often used to prepare AC because plants have evolved over tens of thousands of years with plenty of resources in the world. Cellulose, lignin and sucrose were mixed and ground to simulate ternary biomass carbonaceous precursors for the synthesis of porous AC, as reported by Xue

et al [

22]. Plant-based biomass is particularly attractive due to its abundant reserves, rapid regeneration, and diverse sources. Animal bones and excreta have been also taken as biomass precursors for AC by researchers currently. Using them as precursors not only protects the environment, but also prepares layered porous carbon with high specific surface areas and polyatomic doping. Microorganisms, have also obtained much attention as a precursor for the preparation of porous carbon because of their subcellular structures like plants and animals. Among these three kinds of precursors, using plants as AC precursors is favored by researchers due to the wide range of sources and short growth periods. The biomass residues from plants including leaves, nut shells, and nuts are also sustainable and enriched with lignin and cellulose. The advantages and shortcomings of the three kind precursors are mainly summarized by Hu et al [

23], as shown in

Table 1.

4. Carbon Electrodes Prepared from Different Biomass Resources

To achieve a high specific capacitance for EDLCs, one of the important criteria is the use of carbon-based electrode materials with both large specific surface areas and high conductivity. The common strategy to convert biomass to porous AC usually involves carbonization followed by various activation processes. Thus, the function of activator is to generate additional pores and enhance the surface area of carbon, increasing the activation temperature leading to a rise in specific surface area [

24]. Some important conditions on the activation process have been investigated by researchers. For example, Hegde

et al [

25] reported that KOH activated Tectona grandis at different temperatures (650–850 °C) to obtain porous carbon and that the one treated at 850 °C had the highest surface area, the largest pore volume and the highest specific capacitance of 572 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 in 6 M KOH among them. Other biomass solid such as spent coffee grounds [

26], thistle [

27], cotton stalks [

28], peanut shell [

29], mangifera indica leaf [

30], hemp hurd sticks [

31], abutilon theophrasti [

32], banana leaves [

33], pistachio shells [

34], walnut green seedcases [

35], cynomorium songaricum [

36], grapevine [

37], cotton meal [

38], almond shells [

39], semen ziziphi spinosae [

40], waste bamboo fibers [

41], ceiba speciosa flowers [

42], tea leaves [

43], zanthoxylum armatum seeds [

44], camphor leaves [

45], sugarcane bagasse [

46], and sawdust [

47] were also reported for the preparation of carbon electrodes.

4.1. Plant-Derived Carbon Electrodes

Plants have their own advantages for producing porous carbons, including abundant resources, unique cell structures, short growth periods, and low costs. Thus, they are the most suitable biomass precursors. They are organic materials made up of elements such as carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, et al, and have substantial amounts of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, where these substances create tissues with complex 3D channel structures. Their fruits, flowers and shells are also potential precursors. Meanwhile, different plants have different distributions of mineral elements and microstructure networks.

N and O co-doped porous carbon originated from waste eucalyptus bark could be synthesized via a combination of heteroatom doping assisted by molten salt (KCl/LiCl) and KOH activation at 600 °C [

48]. The optimized electrode with a high surface area of 1719.15 m

2 g

−1 showed a high specific capacitance of 483.5 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 in 1 M H

2SO

4 as electrolyte. Three different chemical activators (KOH, K

2CO

3 and CuCl

2) and C/KOH ratios on the pore structure and electrochemical properties of carbon prepared from camellia seed shells were investigated by Yang

et al [

49], where KOH was the most effective to the formation of the porous structure. It provided a significant exploration for the high-value application of the agricultural waste. Dong

et al [

50] also prepared porous carbon by activating discarded sunflower plates using various alkaline activators (KOH, K

2CO

3 and KCl) at different temperatures. The effect of KOH was still the most effective for SC electrodes, though it was highly corrosive and could have adverse impacts on the equipment and the environment.

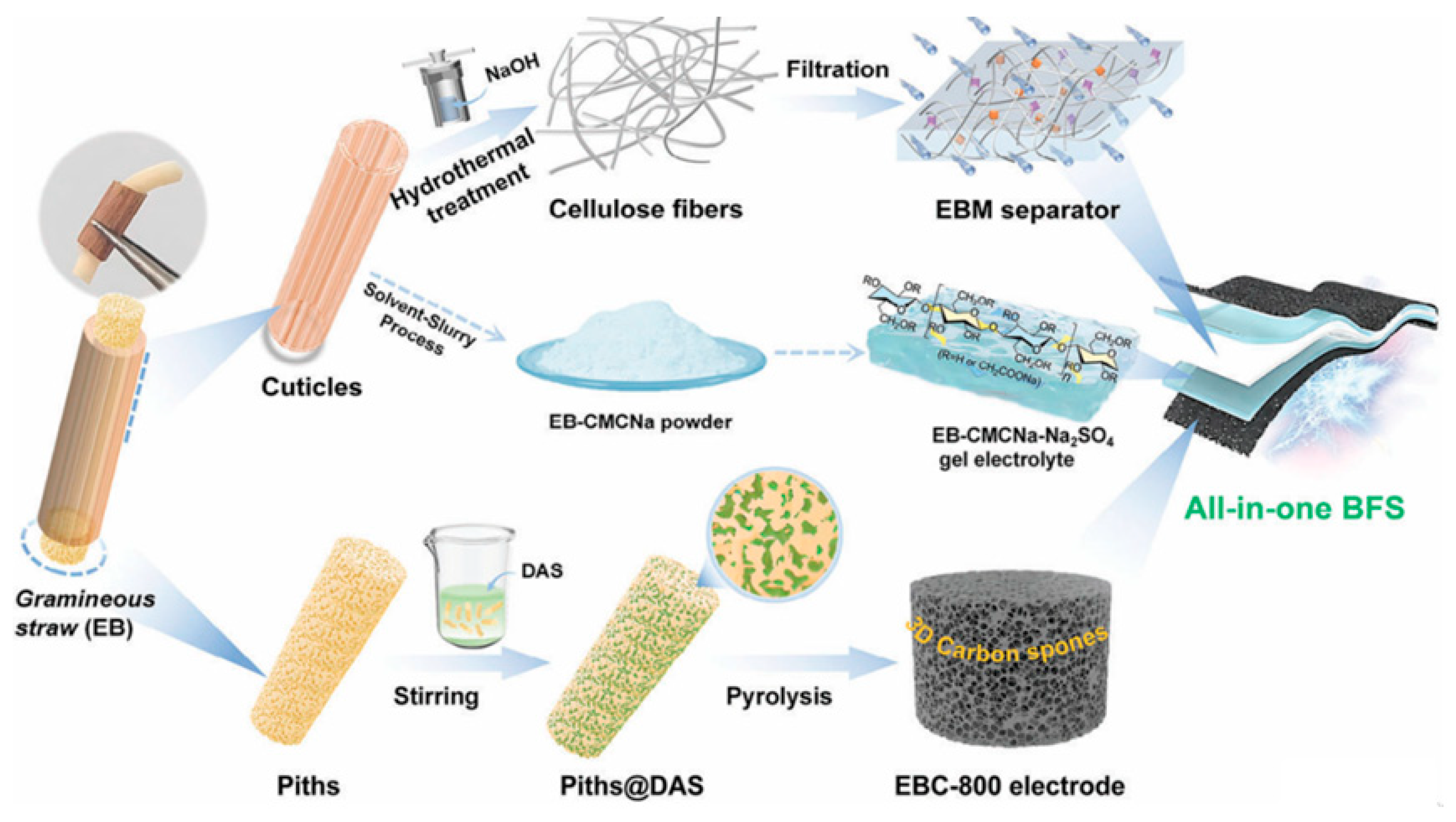

Some gramineous straws have been employed to fabricate porous carbon electrodes for SCs because there are several hundred million tons of various plant straws available across the world every year. Recently, Liu

et al [

51] reported that all the key components of flexible SCs including electrode, separator, and electrolyte could be all made from the eulaliopsis binate (EB) straw, as schematically shown in

Figure 2. By ingeniously utilizing the structures and composition features of different parts from EB, the reported method realized the multiple utilization of EB biomass for SCs. The symmetrical SCs assembled with EB-based carbon electrodes and separators had a high specific capacitance (356 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1) and excellent rate capability in the KOH electrolyte. This work shed novel light on the fully utilization of biomass for SCs. However, its preparation process was somewhat sophisticated.

Fully utilizing the chemical compatibility between ramie chain and phenolic chain, a self-crosslinked strategy to effectively build the high-yield ramie derived carbon was reported by Wang

et al [

52]. The ramie embedded with KOH molecules underwent condensation reaction with the phenolic hydroxyl group in the phenolic resin, well keeping the ramie structure. The presence of ammonium groups accelerated the self-crosslinked reaction to produce large aggregation chains and form a cross-linked structure. Thus, the above process could enhance the carbon yield to above 31%, much higher than pure ramie carbon (3.56%) and pure phenolic carbon (15.22%). The carbon electrode delivered a specific capacitance of 39.03 F g

−1 at 40 A g

−1 in 1 M organic electrolyte. Moso bamboo could be treated by a combination of hydrothermal carbonization and activation to produce 2D porous carbon which had cross-linked carbon nanosheets, hierarchical porous structures, and highly electrochemically active oxygenic groups [

53]. The rich oxygen groups in carbon were beneficial for enhanced energy storage capability, because the oxygen groups had a positive influence on the adsorption of potassium ions in the electrolyte. It showed a specific capacitance of 409.5 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 and kept 308.33 F g

−1 at 20 A g

−1.

4.2. Microorganisms-Based Carbon

Most researchers use animal bones and excreta as biomass precursors. As the structure of animal bone is a natural composite chiefly composed of inorganic minerals and organic matrix. The organic substance is carbon and nitrogen sources, which make them rich in heteroatoms doping. Recently, a honeycomb-like hierarchical porous carbon material was prepared by a self-template coupled dual-hydroxide (NaOH/KOH) activation strategy using mantis shrimp shell as the precursor, as reported by Wei

et al [

54]. The activation conditions were optimized, and the optimal material had a high surface area up to 2465 m

2 g

−1 and a high specific capacitance of 300.3 F g

−1 at 0.05 A g

−1. There were plenty of oxygen-containing groups and nitrogen species, which could contribute to some pseudocapacitance. A high-surface-area carbon material was prepared from waste marine sponge using the pyrolysis technique, where the high specific surface area of 519.82 m

2 g

−1 and oxygen/nitrogen groups on the carbon surface contributed to ion storage and pseudocapacitive behavior with a specific capacitance of 287.33 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 [

55].

Silk is fine soft lustrous fibers produced by a silkworm, it is also reported as a precursor of carbon. An immiscible liquid-mediated method was reported to improve the ionic conductivity of silk-derived nitrogen-doped porous carbon electrodes, where silk was deconstructed in LiBr solution to prepare silk protein solution and NaCl as a template during the followed freeze-drying process [

56]. The introduction of immiscible organic liquid into the carbon promoted the ion transport in the inner pores of the electrodes. A composite of iron oxide quantum dots-modified carbon derived from silk fibroin was also prepared by hydrothermal synthesis, where FeO

x dots were evenly anchored with the carbon material as conductive carrier, which made it have excellent rate performance and cycle performance [

57].

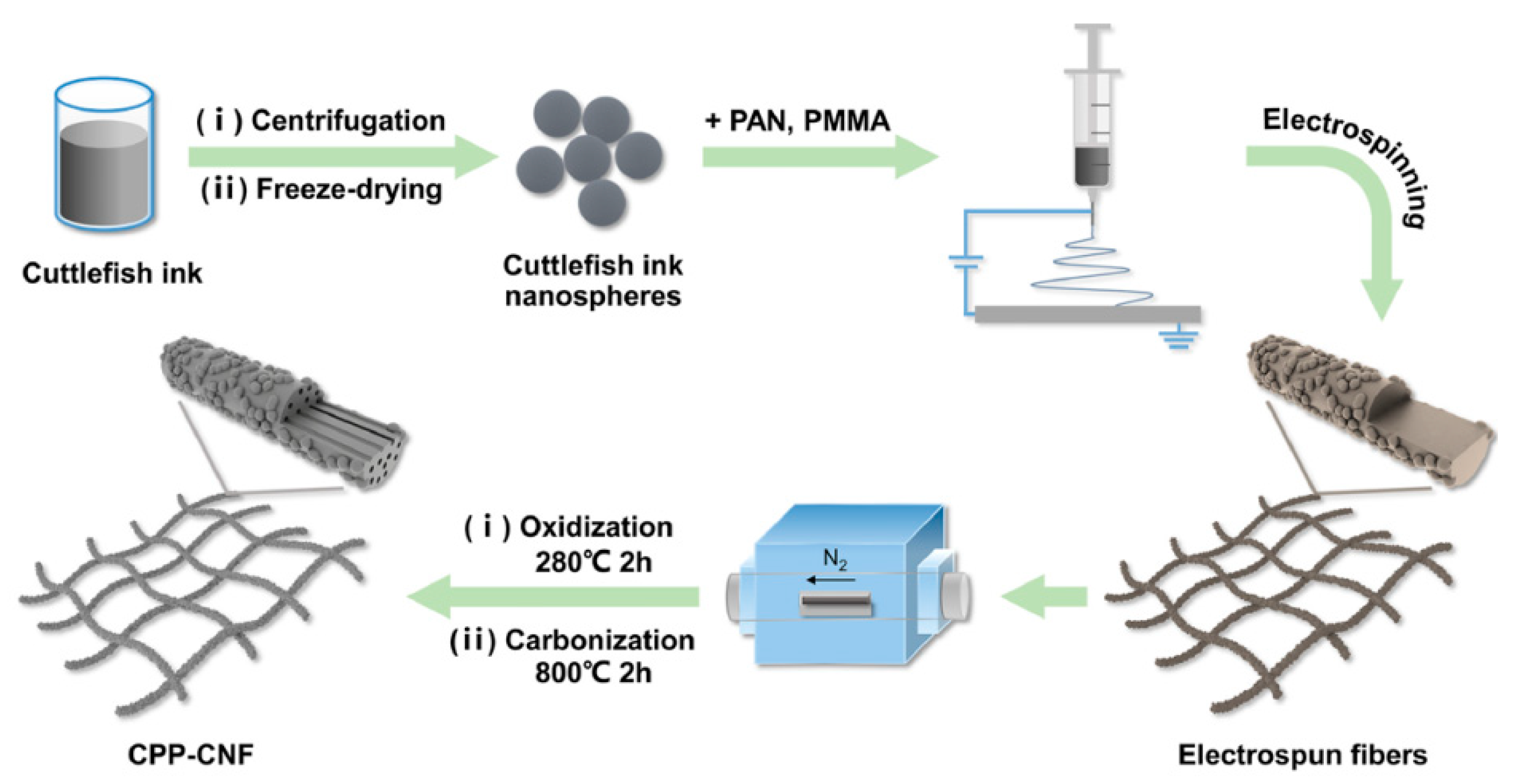

Carbon nanofibers prepared by electrospinning with a single polymer usually have a simple solid structure with a low specific surface area and porosity, thus resulting in a low specific capacitance. Cuttlefish ink as a main structural unit of self-supporting fibers was reported [

58]. The porous carbon nanofibers were prepared by electrospinning and carbonizing the mixture of cuttlefish ink, polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), as schematically shown in

Figure 3. Cuttlefish ink could significantly enrich the pore structure and make it good flexibility, constructing necklace-like carbon nanofibers. Due to the hollow channels, large specific surface area, and high nitrogen content, the flexible carbon nanofiber electrode had a specific capacitance of 364.8 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1.

4.3. Microorganisms-Originated Carbon

Microorganisms can be classified into bacteria, algae, and fungus, consisting of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic and amino acids. Fungal biomass as a raw material to produce carbon has attracted the attention of several research groups due to the rapid growth of fungi and the large amount of chitin in its structure [

59]. Meanwhile, fungal biomass is applied in the biosynthesis of nanoparticles and the process is also called green synthesis. Bazzana

et al [

59] reported a sustainable electrode material for SCs by anchoring Ag nanoparticles onto carbon derived from fungal biomass. Compared with plants, microorganisms are less popularly used as porous carbon precursors. In microorganism-based precursors, mushrooms and algae are the major precursors in the recent reports.

N, S co-doped porous carbon prepared from needle-mushroom by one-step fast pyrolysis process was reported by Guo

et al [

60]. The fast pyrolysis would lead to a fast release of volatile matters, resulting in the coalescence of some micropores into the more developed pore structure. Porous carbon with abundant meso-pores had been prepared by using waste Ganoderma as a precursor, which was then selected as a supporting material to grow in-situ NiMoO

4/CoMoO

4 nano-flower balls on its surface via hydrothermal method to obtain a composite [

61]. The composite electrode had a large specific capacitance of to 802 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1.

Enteromorpha prolifera has adverse effects on marine ecological balance. It is a common seaweed whose large-scale growth has been observed under conditions of water eutrophication. Li

et al [

62] activated it using different activators, including KOH, ZnCl

2 and H

3PO

4, and systematically evaluated their carbon properties. The KOH-activated carbon still exhibited better electrochemical performance than the others, with a specific capacitance of 256 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. Li

et al [

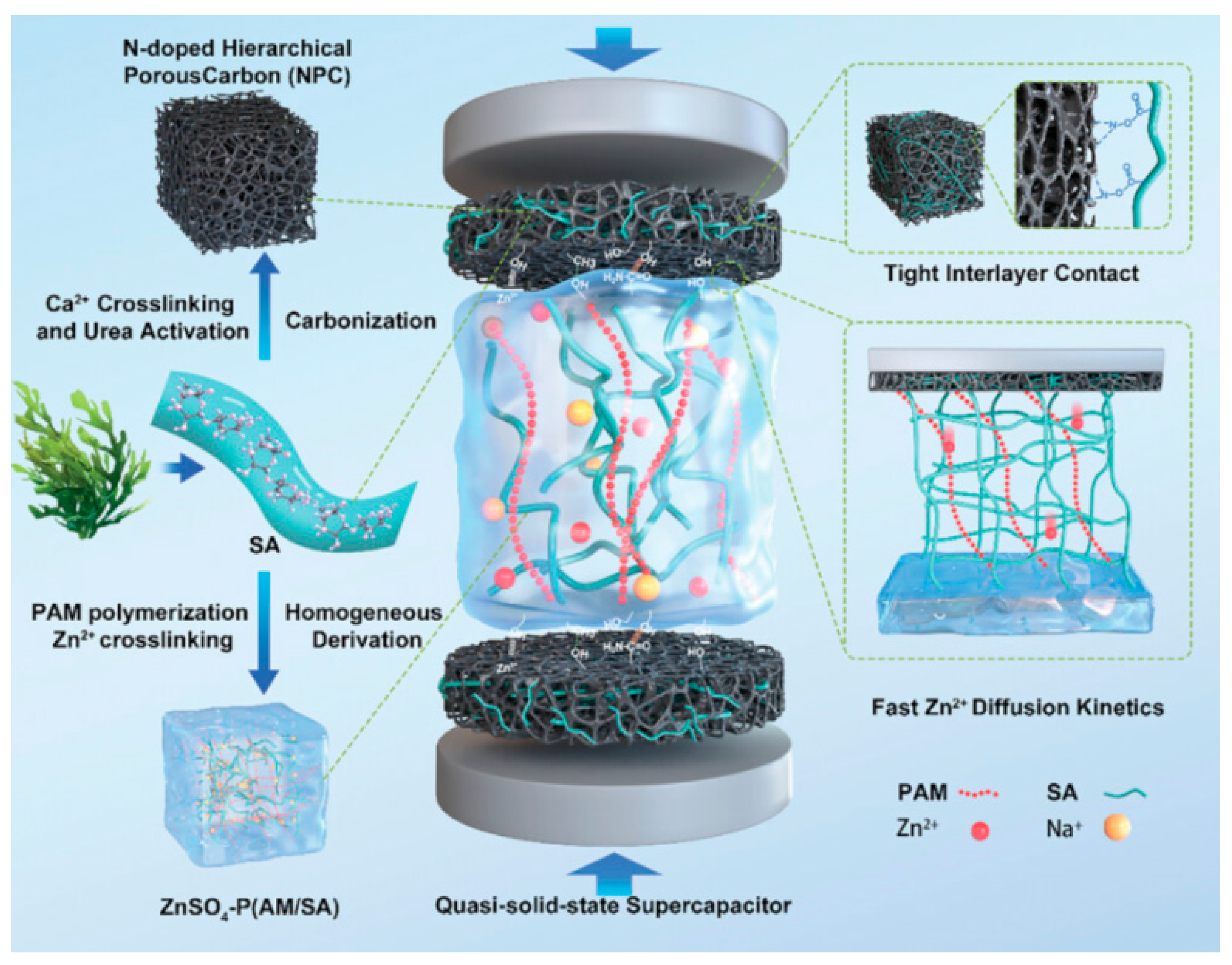

63] reported a strategy to prepare high-energy quasi-solid-state SCs, where electrode materials, binder, and electrolyte were entirely derived from sodium alginate, as schematically shown in

Figure 4. N-doped porous carbon with hierarchical pores and a high nitrogen content could be synthesized by the direct in-situ carbonization of Ca

2+−crosslinked alginate hydrogel and urea. Sodium alginate (SA) with abundant hydrophilic groups as a binder could improve water wettability and reduce resistance. The interpenetrating alginate and polyacrylamide (PAM) network of the ZnSO

4 electrolyte enhanced the mechanical strength, electrolyte retention rate, and ionic conductivity. The supercapacitor delivered a specific capacitance of 180 F g

−1 at 0.25 A g

−1. This work highlights the high-value utilization of sodium alginate for high-energy SCs.

The abundance of heteroatoms in microorganisms implies that they are suitable for the preparation heteroatom-doped carbon. A natural heteroatom doping strategy was reported, using bamboo and spiral algae as carbon sources, and spiral algae as a natural heteroatom (N, O, S) dopant [

64]. N/O/S co-doped porous carbon was prepared by the co-pyrolysis of spiral algae and bamboo, which was a simple synthesis route. After potassium acetate activation coupling natural heteroatom doping, the resultant porous carbon had a capacitance of 320.4 F g

−1 (0.5 A g

−1). Spiral algae was also used as the raw material through a strategy combining one-step carbonization method, hard template technique and activation approach to prepare multi-heteroatom self-doped carbon [

65]. Self-sourced nitrogen-doped carbon was also prepared using algae-derived bio-oil distillation residue as the raw material [

66].

4.4. Other Biomass-Based Carbon Electrodes

In addition to above three kinds of biomass precursors, other biomass-based porous carbon materials are also reported for SCs electrode. Some biomass waste materials are highly advantageous for the production of porous carbon due to its abundant, cost-effective, and renewable nature. They may contain a large number of heteroatoms (including nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P), sulfur (S), oxygen (O), etc.) in their natural structure, which can make a self-doping process. For instance, distiller grains are a byproduct generated during the process of liquor production. Han

et al [

67] reported that distiller grains powder was carbonized and activated by KOH to produce N/O self-doped activated carbon. A large number of pores were formed by direct activation, which provided a lot of active sites for electrolyte adsorption. The carbon material exhibited a high specific capacitance of 345.2 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. A high-surface-area carbon material with multiple heteroatoms doping was derived from rapeseed meals by hydrothermal carbonization and high-temperature activation [

68]. It showed a high surface area of 3291 m

2 g

−1 and was doped with nitrogen (1.05 at.%), oxygen (7.4 at.%), phosphorus (0.31 at.%), and sulfur, exhibiting a specific capacitance of 416 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. The carbon was self-doped with heteroatoms due to the abundance of components present in it. Spent mushroom substrates were also employed to prepared porous carbon electrodes for SCs by pre-carbonization and activation processes [

69]. Rose petals were selected and activated by K

2CO

3 to prepare porous carbon and it had a specific capacitance of 320.8 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 [

70].

A solid-phase activation method was introduced by Geng

et al [

71] to prepare O-functionalized porous carbon with embedded graphene-like structures with D(+)-glucose as a precursor. The porous carbon had a very high surface area (3572 m

2 g

−1) with rich oxygenated functional groups on surface when it was activated by KOH at 500 °C, where the activation agent introduced oxygen functional groups on the carbon surface. The optimized material showed a high specific capacitance of 305 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 and 207 F g

−1 at 10 A g

−1.

5. Strategies to Improve the Specific Capacitance of Biomass-Derived Carbon

The limited energy density of SCs still significantly hinders the commercial viability. Despite their numerous benefits, the specific capacitance of biomass-based carbon electrodes must be further increased in order to meet the future demands of SCs. There are some strategies that have been developed by researchers to further improve the specific capacitance of biomass derived carbon (BDC). In the following section, we will introduce the recently developed strategies to enhance the energy storage ability related to BDC electrodes.

5.1. Doping with Heteroatoms

Although SCs made of carbon electrodes have been commercialized, the low energy density has still limited their widespread application to a large extent. Heteroatom doping has proved effective in improving the electrochemical properties of carbon-based electrodes for SCs, because the incorporation of heteroatoms (such as N, S, P, etc.) into BDC has been demonstrated to improve the surface wettability, and enhance the electrode-electrolyte interaction.

Nitrogen is one of the most popularly used heteroatoms to dope BDC in order to obtain an enhanced specific capacitance. N-doping in the carbon skeleton is easily carried out due to the similar covalent radius of carbon (0.77 Å) and nitrogen (0.74 Å). Nitrogen atoms do not alter the fundamental structure of carbon materials significantly. The electronegativity of nitrogen atoms guides the conduction of induced current within the carbon skeleton, thereby enhancing the stability between particles. N-doped BDC from red beetroot was prepared by heating pre-carbonized powder, KOH and urea in a nitrogen atmosphere at 800 °C [

72]. Compared with the samples without N-doping and KOH activation, the N-doped BDC had a larger specific surface area with a sponge-like structure and a higher specific capacitance of 492 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 in 1 M Na

2SO

4 electrolyte. Similarly, N-doped activated carbon from marula nutshell was obtained by KOH treatment and using melamine as a nitrogen source through ex-situ doping [

73]. It exhibited a specific capacitance of 350 F g

−1 in 6 M KOH and 248 F g

−1 in 2.5 M KNO

3 electrolyte. It was reported that KOH treatment could change the states of N atoms in the carbon materials. By the one-step KOH activation of houttuynia cordata and melamine, nitrogen-doped porous BDC could be synthesized and the etching effect of KOH promoted the conversion of N-Q (quaternary N) to N-6 (pyridinic N) and N-5 (pyrrolic N) [

74]. The carbon electrode has a specific capacitance of 220.54 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 with a high specific surface area of 2491.5 m

2 g

−1. The N-doped carbon prepared from hazelnut shell as electrode materials showed a specific capacitance of 334 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1 [

75]. The authors claimed that these nitrogen-containing functional groups endowed the material with large pseudo-capacitance.

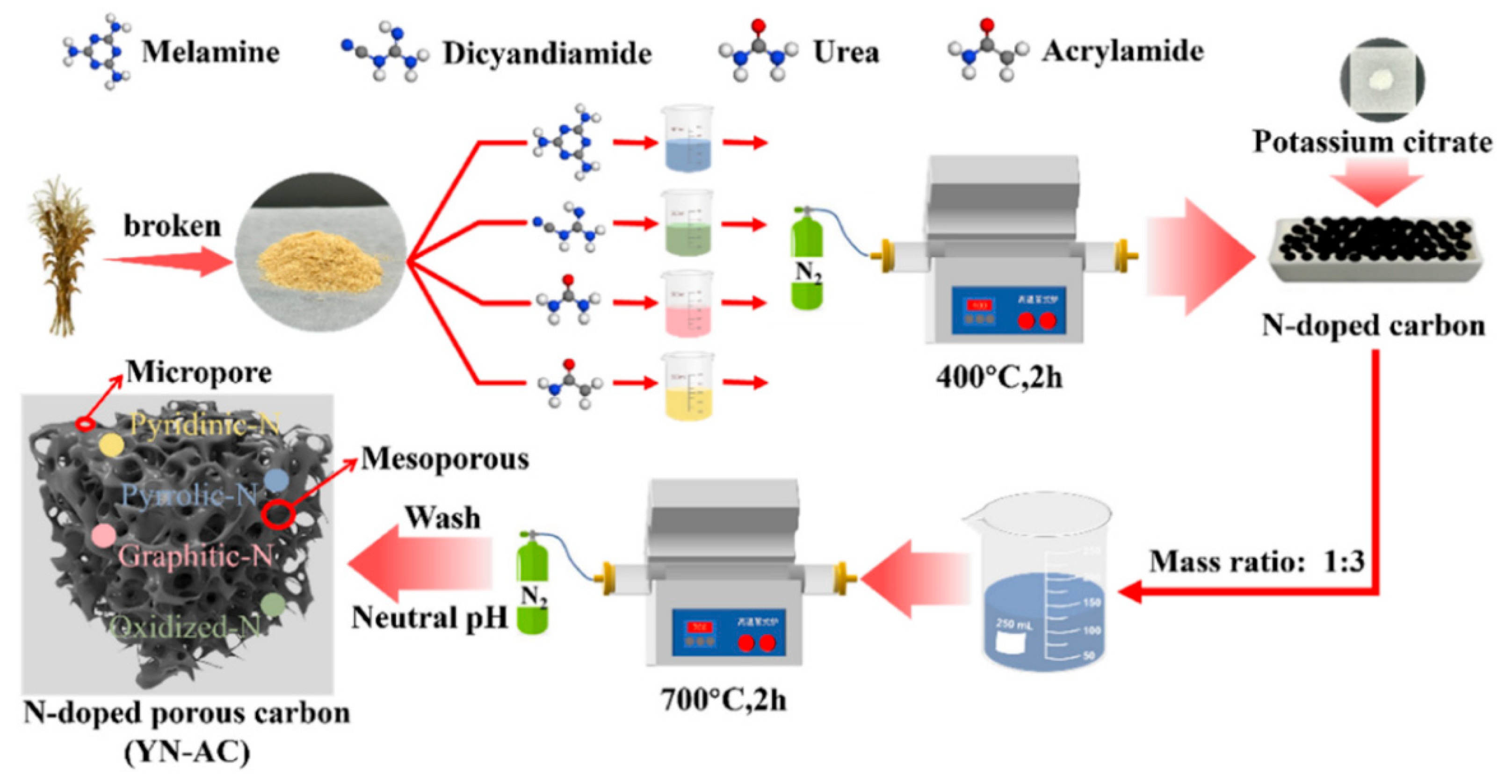

More recently, Chen

et al [

76] compared four different nitrogen sources and investigated different nitrogen species, in order to determine the most suitable nitrogen source for biomass-carbon SCs, where Job’s tears straw was a biomass precursor, as schematically shown in

Figure 5. The results showed that melamine was the most suitable for biomass-based SCs with a high surface nitrogen content of 4.54%, and the pyrrole nitrogen provided greatly contribution to the capacitor performance. Numerical calculation showed that the large amount of pyrrole nitrogen provided by melamine played an important role in improving the adsorption of electrolyte ions, thus delivering a specific capacitance of 349.3 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1. The relationship between pyrrolic N content and the electrochemical properties of porous hydrothermal carbon by utilizing grapevine as the carbon source was explored by Li

et al [

77], where coffee residue, rich in heteroatoms, was chosen as the doping agent. They found that excessive N doping led to the conversion of pyrrolic N into graphitic N, reducing the effect of heteroatom doping.

In addition to nitrogen, other heteroatoms including P and S were also applied to dope carbon. The introduction of heteroatoms (P) and oxygen surface functionalities into the cellulose allowed for the tuning of electrochemical performance of SCs, where honeydew peel was a source of carbon [

78]. The high phosphorous doping degree enabled the transportation of ions at higher current rates. P-doping on carbon could be also achieved by hydrothermal treatment with orthophosphoric acid and carbon from coconut husk [

79]. Meanwhile, S-doped carbon electrode was also carried out [

80].

Compared with single-atom doping, polyatomic doping can improve the compatibility between carbon and electrolytes with significant synergistic effects. Thus, multi-atom doping was also reported in recent papers. B/N co-doped micro/meso carbon composites prepared with wheat straw based cellulose nanofibers had desirable content of N and B dopants, showing a specific capacitance of 433.4 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 [

81]. N/P co-doped BDC derived from sugarcane bagasse synthesized by hydrothermal method with subsequent KOH activation and carbonization, had a special hierarchical porous structure, a high surface area and large interlayer spacing, and exhibited a high specific capacitance of 356.4 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1, where melamine and NaH

2PO

4 were dopants [

82]. N/O co-doped BDC originated from garlic peels was fabricated by pre-carbonization combined with KHCO

3/melamine activation [

83]. The high contents of N and O could enhance the wettability of carbon materials and introduce additional pseudocapacitance. It achieved a specific capacitance of 396.25 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 with good rate capability. N/O co-doped BDC originated from rapeseed stalks also showed a high specific surface area of 3085 m

2 g

−1 and a specific capacitance of 354.7 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 [

84], where N was naturally present heteroatoms in the biomass. N/S co-doped paper fiber carbon foam was prepared by a foaming technique and thiourea doping [

85]. The optimized material showed a specific capacitance of 245.24 F g

−1 at 0.1 A g

−1. Carbon materials co-doped with N and P for their application as electrodes in SCs was carried out through conventional chemical activation with H

3PO

4 and using chitosan with different molecular weights (low, medium, and high) as a N-containing natural precursor [

86]. N,S co-doped porous carbon by carbonization of waste sugarcane bagasse fibers in the presence of N

2H

4 and H

2S as sources of nitrogen and sulfur, respectively, followed by liquid-phase and gas-phase activation processes was performed [

87]. A remarkable large surface area of 2455.6 m

2 g

−1 and a specific capacitance of 405.67 F g

−1 at 0.2 A g

−1 were achieved for the carbon.

B/N/P co-doped porous carbon was prepared by hydrothermal method combined with KOH activation using orange peel as a raw material for SCs electrodes [

88], where (NH

4)

2HPO

4 and boric acid were used as dopants. It had high specific capacitances of 318.8 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 and 289 F g

−1 at 5 A g

−1, with only 6.4% capacitance loss after 10000 cycles. Above results from recent papers indicate that heteroatoms doping can enhance the performance of BDC. The electrochemical properties and doping agents of heteroatoms are summarized in

Table 2. It can be seen that most BDC electrodes display high specific capacitances, higher than 200 F g

−1. However, different dopants should be involved during the preparation process. Some dopants can be completely decomposed into gases at the elevated temperatures, such as urea, melamine etc. However, some will have residual after doping. Thus, an additional purification process is necessary and it will inevitably improve the final production cost.

5.2. Designing Novel Composites

BDC with a 3D interconnected porous structure can provide a continuous channel and shorten the diffusion path length for electrolyte ions. Though it has high cycling stability and excellent rate capability, but suffers from a relatively low energy density and low specific capacitance. In order to enhance the energy density, it is an effective method to deposit a pseudocapacitive substance into the carbon electrodes. Thus, a composite consisting of BDC and guest materials is expected to have improved energy storage capacity. The guest substance contributes to the high specific capacitance, and the carbon skeleton prevents the aggregation and ensures rapid transfer of electrolyte ions. Recently, various new composites have been prepared for SCs electrodes, such as NiCo layered double hydroxide (LDH) grown on peanut-shell based carbon [

89], NiCo

2S

4/carbon derived from Zanthoxylum bungeanum branches [

90], MnCO

3/mango peel biomass-derive carbon [

91], NiCo-LDH/MnO

2@carbon from wood [

92], NiO/carbon from sugarcane bagasse [

93], NiO/carbon from putranjiva seeds [

94], and NiO/walnut shell-based carbon [

95].

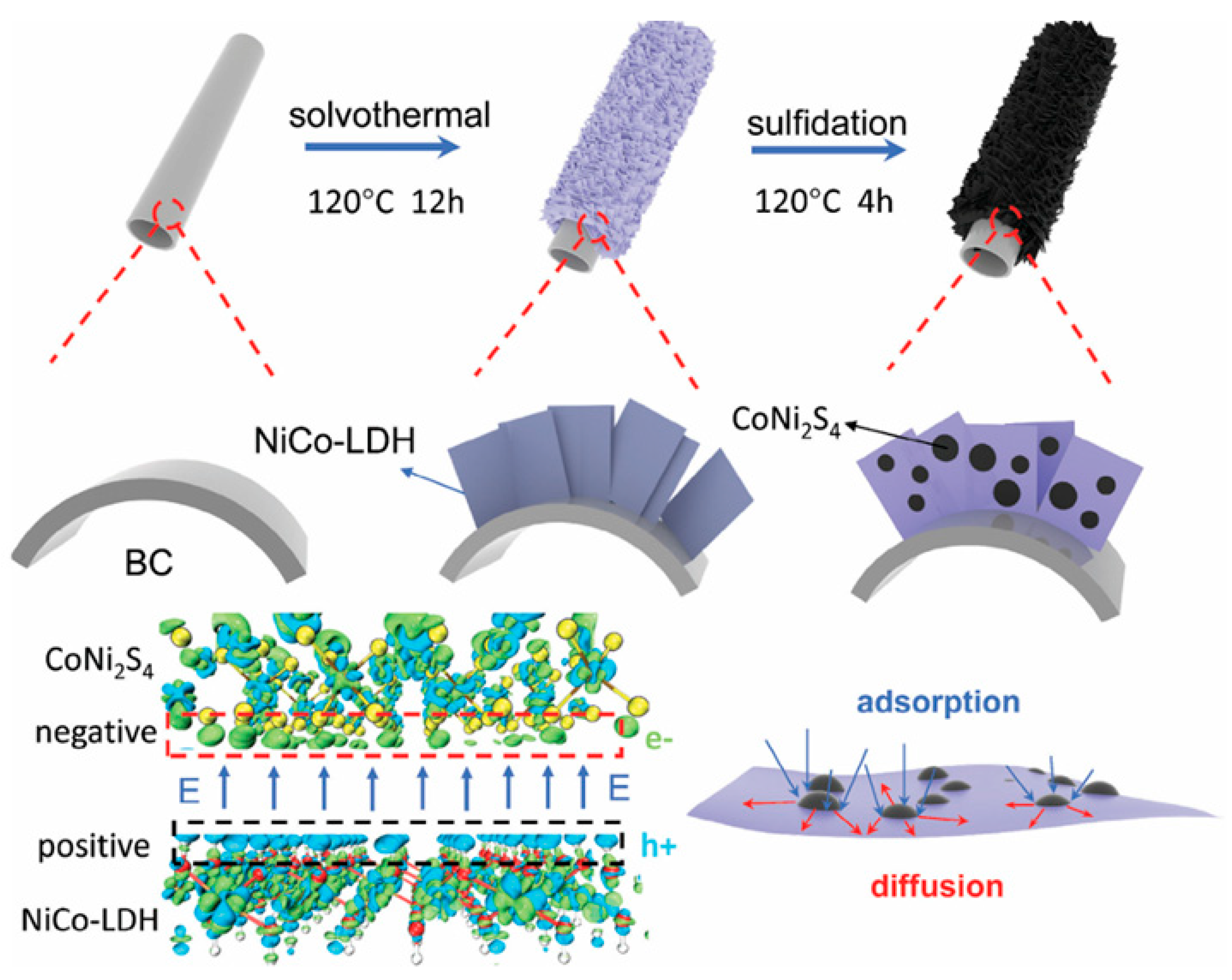

In addition to above metal oxides and hydroxides, some metal sulfides have been chosen to prepare composites with biomass-based carbon. An activated hollow tubular biomass carbon (BC) derived from typha orientalis was employed as a conductive substrate for the uniform growth of NiCo-LDH nanosheets [

96]. After a partial in situ sulfidation process, CoNi

2S

4 could be embedded in the interlayer of NiCo-LDH nanosheets. The synthesis process of the trinary composite is schematically shown in

Figure 6. The unique heterostructure enhanced ion adsorption capacity, leading to a significant improvement in ion/electron reaction kinetics, and the robust BC framework prevented electrode degradation. The combination of NiCo-LDH/BC and CoNi

2S

4 resulted in the formation of p-n heterojunctions, showing a refined energy-band structure with smaller bandgaps. The island-like CoNi

2S

4 could also generate more active edges. These typical advantages enable the composite electrode to achieve a high specific capacity (1655.75 C g

−1 at 1 A g

−1). A hybrid capacitor assembled with it and activated carbon achieved a high energy density of 95.57 Wh kg

−1 at 866.61 W kg

−1. A composite of 3D N-doped porous carbon coupled with nickel-iron sulfide nanoparticles was fabricated by a simple pyrolysis process, as reported by Sun

et al [

97], with chitosan as a carbon precursor. The composite exhibited excellent charge storage capacity owning to the integration of binary nickel-iron sulfides and 3D hierarchical porous structure, with a specific capacitance of 2812.4 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1. Nickel-iron sulfide nanoparticles in the porous carbon could offer rich reaction sites for reduction and oxidation to improve the charge storage.

In addition to psudocapacitive materials, some carbon materials were also selected to make composites using BDC as a component. A lignin depolymerization product was mixed with phenol and formaldehyde to generate a lignin-based phenolic resin [

98]. The lignin-based phenolic resin carbon had a 3D linkage structure and graphitized structure that improved charge mobility, and it showed a specific capacitance of 108.2 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. A carbon aerogel was prepared with cellulose fibers, graphene oxide and polyimide nanofibers, and it showed excellent compressibility, flexibility and cycling stability as SCs electrodes [

99]. The biowaste of litchi seed was used to synthesize 3D activated carbon by carbonization and activation [

100]. Then, a 3D composite was synthesized as a negative electrode by combining 1D multiwalled carbon nanotubes and 2D reduced graphene oxide sheets with the 3D activated carbon as a supporting matrix. The new 3D composite had a specific capacitance of 320 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 in a 6 M KOH electrolyte. Similarly, 3D activated carbon was also used as a substrate to grow zinc cobalt sulfide nanoparticles as a positive electrode [

100]. Finally, asymmetric capacitors based on above two electrodes exhibited promising electrochemical performance, with enhanced energy density, high cycling stability, and high capacitance. More recently, Cheng

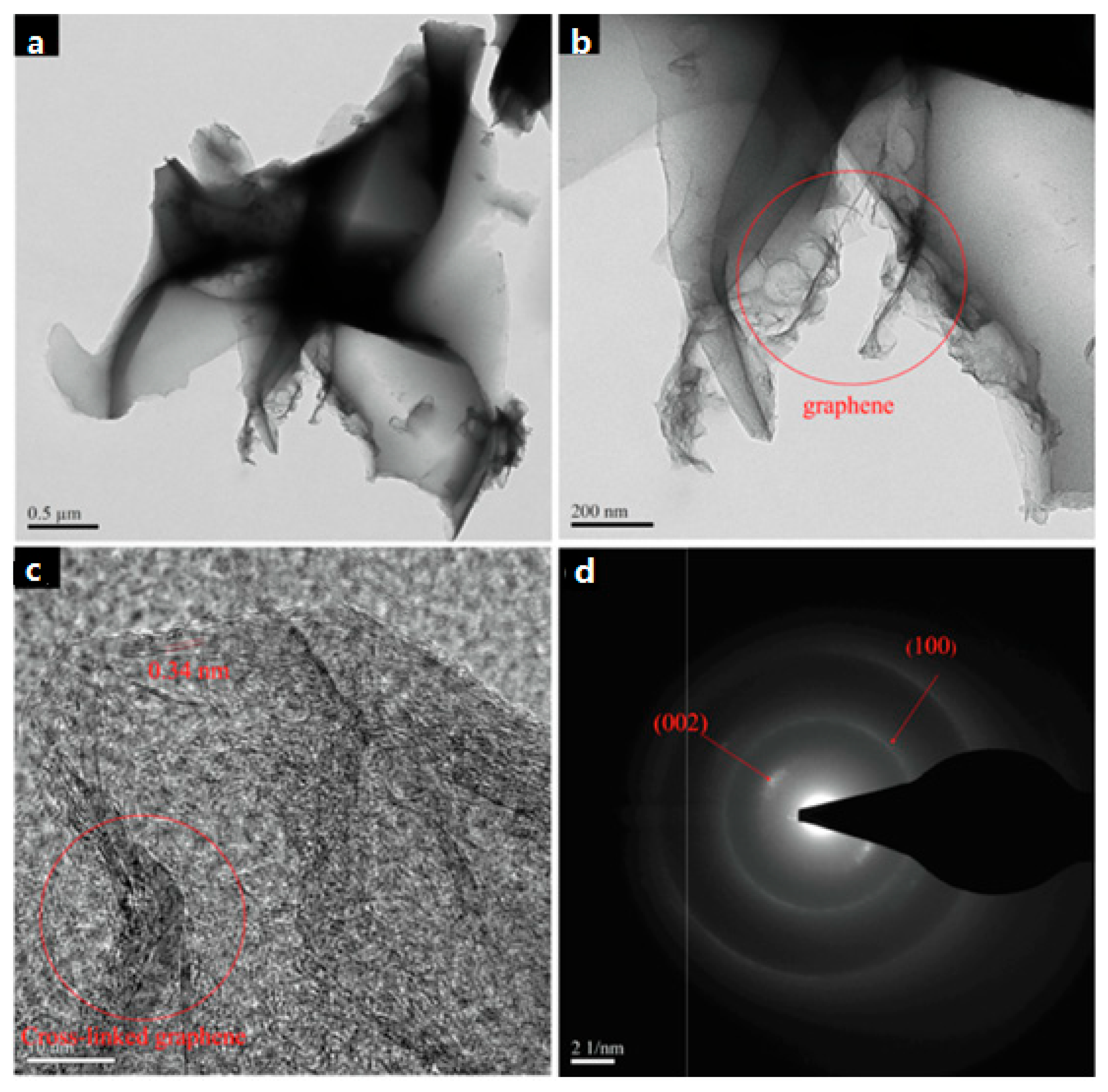

et al [

101] applied jute fibers as a precursor and fabricated activated carbon by the combination of hydrothermal method and activation process. They discovered that multilayer graphene spontaneously formed on the edge or surface of activated carbon during the activation process by KOH, as shown in

Figure 7. The composite had a specific capacitance of 220 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1. In Figures 7a,b, it can be proved that graphene forms on the surface or edge of BDC. A high resolution TEM (HRTEM) image in

Figure 7c confirms the existence of multilayer graphene and shows graphite interplanar spacing (0.34 nm). The corresponding electron diffraction pattern in

Figure 7d shows graphite (002) and (100) diffractive planes. KOH could do a favor for generating graphene, in addition to micropores.

Even some conductive polymers were also coupled with BDC to synthesize composite electrodes. For example, Lv

et al [

102] reported a binary composite in which psudocapacitive polypyrrole was deposited on the hierarchical porous BDC originated from Chinese fir to improve its energy density and specific capacitance. The weight-specific capacitance of the optimal electrode was 374.1 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. Thus, some guest materials including psudocapacitive, carbon-based and conductive polymeric materials have applied to incorporate with biomass carbon, in order make it provide high conductivity and guarantee rapid transfer of electrolyte ions. Due to the obviously difference of guest materials and biomass precursor, the electrochemical performance of the resultant composites is varied to a large extent.

5.3. Innovative Processes

The production of carbon from biomass usually involves two sequential steps, i.e. carbonization and activation. Carbonization is the thermal decomposition of biomass under high-temperature and oxygen-free conditions, chiefly including pyrolysis, hydrothermal and microwave-assisted carbonization, with pyrolysis being the most widely used. Activation processes can be frequently categorized into two approaches, chemical and physical activation. He

et al [

103] employed four different methods to prepare BDC to systematically investigate the effects of preparation processes (one-step/two-step) using walnut shells as the raw material. The effects of synthesis processes, heating rate, and carbonization temperature on the product yield, electrochemical performance, and economic benefits were investigated. In addition to above traditional conditions, some novel processes are also developed by researchers to improve the electrochemical behavior. The chief purpose of these processes is to modify the surface functional groups and porosity of carbon materials, because the surface of BDC plays a significant role in determining its specific capacitance. To improving the surface area of carbon materials, it is crucial to ensure the presence of a well-developed pore structure in carbon. BDC can inherit the precursor structure by tuning the functional surfaces during the carbonization process, resulting in the product delivering high capacitance and long-term stability.

KOH is a common activation agent in producing porous carbon due to its good ability to generate a substantial specific surface area. It is more effective than both H

3PO

4 and ZnCl

2 to activate pre-carbonized peanut shell [

104]. Physically activated carbon through gaseous CO

2 activation at 850 °C was reported by Ahmad

et al [

105] with date seed biomass as the precursor, where the activated one had a low specific surface area of 659.56 m

2 g

−1. Though, physical activation is of environmental benefits, its efficiency is lower than the chemical method.

The surface modification of BDC has been reported by using chemicals and air oxidization. The acid functionalized carbon made from the inner skin of arachis hypogaea significantly outperformed the non-functionalized one, showing a fourfold increase in specific capacitance [

106]. Two different modification methods were applied by using camphor tree as the carbon precursor [

107]. Through the chemical activation by nitric acid, the nitrogen functional groups had been generated on the surface of carbon. After treatment by copper chloride, the specific surface of carbon could be enlarged. The electrochemical measurements indicated that the carbon after above two treatments had high specific capacitances. Mesoporous BDC prepared from coconut fibers by H

3PO

4-assisted hydrothermal pretreatment combined with a low KOH-to-hydrochar ratio activation [

108]. The hydrothermal treatment could increase the micropores of the activated carbon by hydrolyzing the β-glycosidic linkage of hemicelluloses and the aryl ether bond of lignin. The followed KOH activation would develop a large number of mesopores and oxygen groups on surface. The carbon electrode had a specific capacitance of 315.5 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. A coordinated regulation method consisting of carbonization at 450 °C, ZnCl

2 activation at 400-800 °C and air oxidation at 200-350 °C could efficiently improve the physicochemical structure and electrochemical properties of BDC from bamboo. The additional air oxidation on the basis of 600 °C activation showed the most outstanding optimization effect, which could be even further strengthened by the increased oxidation temperature in air, as reported by Qin

et al [

109]. Air oxidation following 600 °C activation could improve the mesoporous rate, and simultaneously introduce more oxygen-containing groups such as carbonyl (C=O) and carboxyl (–COOH) groups, as evidenced from XPS analysis. The optimized sample had a specific capacitance of 256 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1.

In addition to surface modification, some novel treatments on the fresh biomass by chemical method can also enhance chemical performance and activation effect. Recently, Li

et al [

110] treated wheat straw using a Fenton reagent of Fe

3+ and H

2O

2 to obtain a crumbly and porous 3D structure. The presence of iron ions appeared to promote more hydroxyl radicals in the H

2O

2 solution, which enhanced the oxidation of the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in the wheat straw, and destroyed the network structure of original macromolecules. After carbonization and activation, a hierarchical porous material was achieved, with a high specific surface area of 3440 m

2 g

−1 and a high specific capacitance of 425.2 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. Similarly, Yang

et al [

111] also prepared porous carbon materials by pretreating biomass with Fe

3+/H

2O

2 Fenton-like reagent using agricultural waste biomass. The hydroxyl radicals could oxidize the biomass, increasing the porosity and improving the followed activation efficiency. The prepared carbon electrode had a specific capacitance of 349 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1.

Some novel methods were also reported to control the pore structure of BDC. The liquefaction process can degrade high molecular solids into low molecular liquid products with active groups. A solid–liquid state conversion was realized under the liquefaction condition of the green organic solvent polyethylene glycol (PEG400) using soybean straw as a raw material and further in-situ doping the N and S liquid phase under hydrothermal reaction [

112], improving the active sites of soybean straw liquefaction products. The pore structure of the obtained carbon was controlled with non-toxic potassium citrate. In the three-electrode system test, the carbon exhibited a specific capacitance of 220 F g

−1 at 0.5 A g

−1. The hydrogel-controlled carbonization of glucose was applied to produce porous carbon with high surface areas and controllable pore structures, where polyacrylamide was used as the pore-forming agent, and pore structures could be controlled by the polyacrylamide content [

113]. The porous carbon had a specific capacitance of 441 F g

−1 at 0.25 A g

−1. Apple waste-derived carbon was synthesized using a two-step method including carbonization and chemical activation with KMnO

4, where KMnO

4 served not only as an activator for porosity but also enhanced electrochemical performance by forming rich oxygen-rich groups [

114].

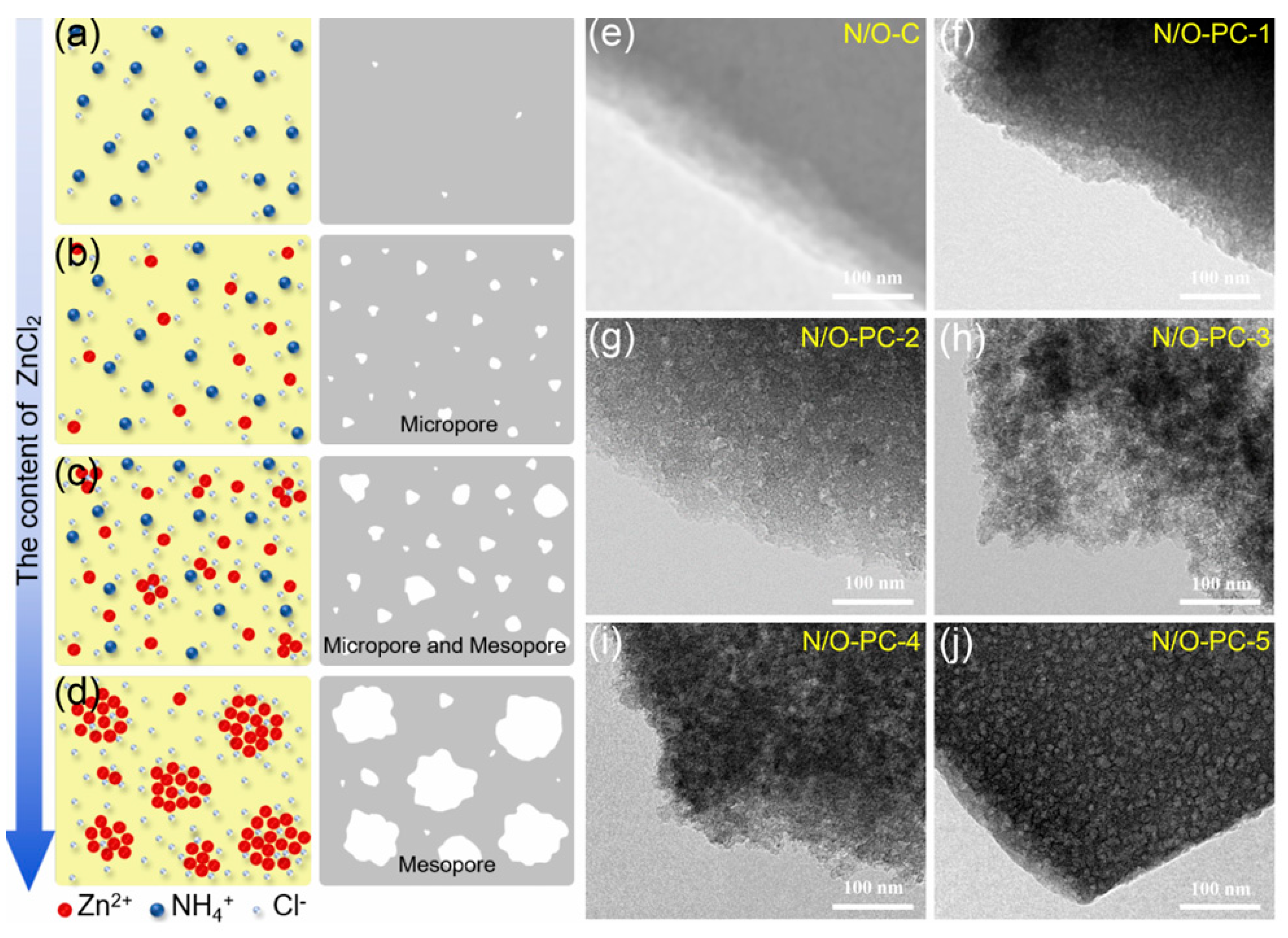

Jiang

et al [

115] reported a N/O co-doped hierarchical porous carbon material synthesized through a one-step carbonization and activation treatment of biomass Chinese yam using ZnCl

2 as an activating agent, with NH

4Cl and dopamine from the Chinese yam serving as the nitrogen sources. By changing the aggregation degree of zinc-containing hydrolysates in biomass and the subsequent release of large amounts of gas, the carbon had rich interconnected micropores and controllable small-sized mesopores. As schematically shown in Figures 8a–d, the aggregated zinc containing substances grow larger with increasing ZnCl

2 content and act as an activator, etching carbon atoms to form a uniform mesoporous structure. TEM images in Figures 8e–j show the creation of numerous micropores and mesopores in carbon matrix. By the precise control of pore structure and surface area, the electrode materials could achieve rapid ion transport and enhanced charge storage capabilities. Due to the micropore-dominant pore structure, high nitrogen and oxygen contents, a high gravimetric specific capacitance of 414 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 was achieved. More recently, Narayanan

et al [

116] reported that the chemical treatment of KOH-activated carbon from grape marc with ZnCl

2 would lead to the expansion of micropores into mesopores.

5.4. Improving Graphitic Degree

Generally, fresh plant precursors, consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, play a vital role in the polymorphism of BDC, because they essentially influence the graphitization degree of carbon. Cellulose derived carbon having parallel hydrogen bond networks has the remarkable crystallinity for the improvement of electrical conductivity. The existence of hemicellulose in biomass strongly hinders the lateral growth of carbon crystals, and the presence of lignin extensively forms amorphous carbon. Thus, BDC usually exhibit an amorphous nature. Both the low graphitization degree and content in carbon will reduce its conductivity. It is still crucial for conductive BDC to rationally develop highly graphitized microcrystal, because it will form excellent conductive networks for increasing conductivity. The creation of a graphitic framework in BDC is frequently used to improve electrical conductivity and electrochemical properties. For example, annealing the carbon derived from pumpkin skin under H

2 atmosphere could improve the specific surface area and create a graphitic-like hierarchical structure with mesopores [

117]. This graphitization of porous carbon enhanced ion transport and helped to improve the electrical conductivity of the carbon materials.

Figure 8.

(a–d) Schematic diagrams illustrating the generation of (a) almost nonporous structure, (b) microporous structure, (c) microporous and mesoporous structure, and (d) mesoporous structure, resulting from the different dispersions of zinc-containing materials by varying the amounts of ZnCl

2; (e–j) TEM images of carbon materials [

115].

Figure 8.

(a–d) Schematic diagrams illustrating the generation of (a) almost nonporous structure, (b) microporous structure, (c) microporous and mesoporous structure, and (d) mesoporous structure, resulting from the different dispersions of zinc-containing materials by varying the amounts of ZnCl

2; (e–j) TEM images of carbon materials [

115].

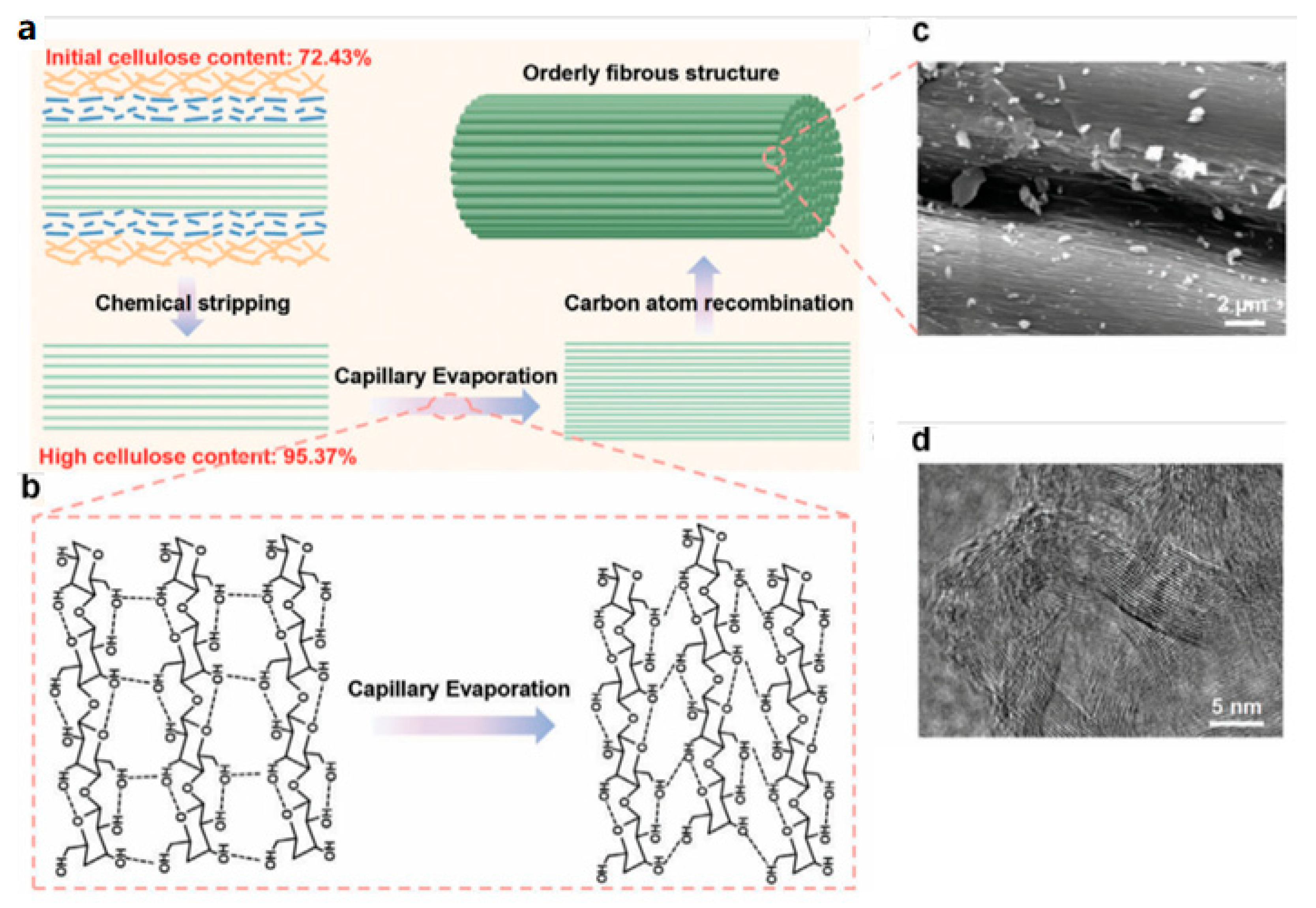

Regulating the content of cellulose in biomass can modulate the graphitization degree of BDC. Wang

et al [

118] applied a simple capillary evaporation strategy to prepare high-dense conductive carbon with ramie as precursor. This chemically stripped ramie having a high content of cellulose (95.37%), improving the intrinsic properties including electrical conductivity, surface area, pore volume and compacted density, as illustrated in

Figure 9. Figures 9a,b schematically show the strategy of preparation and dense cellulose molecules, where hydroxyl and superoxide anions produced by peroxyformic acid solution can depolymerize and dissolve lignin and hemicellulose, improving the content of cellulose. A typical SEM (

Figure 9c) and a high resolution TEM image (

Figure 9d) display the obviously ordered structure after carbonization, proving the reorganization of carbon atoms during pyrolysis. A capacitor prepared using the high-conductive carbon had a high energy density of 9.01 Wh L

−1 at the power density of 25.87 kW L

−1, improving the electrochemical stability and volume performance. Similarly, cellulose nanofibrils linked with lignin and acted as skeleton of lignin/cellulose aerogels, which could regulate the graphitization degree of the carbon and manage the specific surface area and pore structure. The optimal electrode displayed a high specific capacitance of 178 F g

−1 at 0.2 A g

−1 in a two electrode system [

119].

Catalytic graphitization using transition metals is still a powerful approach to enhance the degree of graphitization at low temperatures. However, a catalyst must be present in the carbon matrix and it is finally removed by subsequent purification. The use of boron as catalyst could greatly enhance the graphitization process at relatively low temperatures, thereby improving the electrochemical performance of carbon electrodes. It was first report with boron as catalyst [

120]. Highly graphitized BDC using pure boron as a catalyst and logging residues from pine tree as a carbon source could be prepared [

120]. Compared with the sample without boron, the boron-treated sample exhibited far more graphitic layers in its structure, delivering a specific capacitance of 144 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. Similarly, the presence of K

2FeO

4 as bifunctional catalytic activator significantly contributed to enhance the graphitization degree and the formation of micropores with peanut shells as a biomass feedstock [

121]. The optimal carbon had a specific capacitance of 339.25 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. The increased conductivity of graphitic carbon is expected to reduce the resistance of carbon electrodes, typically suitable for the application of high current densities.

5.5. Unique Preparation Methods

The popular method to prepare BDC for SCs involves carbonization followed with activation. High-efficiency and environmentally friendly preparation methods are becoming a focal point of attention. Thus, some one-step methods to prepare BDC have been developed more recently. With broad bean shells as a raw material, nitrogen/oxygen self-doped BDC could be successfully synthesized via a one-pot activation strategy employing a mixed salt system of potassium carbonate and potassium citrate, under two-stage programmed pyrolysis conditions [

122]. Due to the inherent heteroatoms in biomass, the BDC material achieved a specific capacitance of 376.1 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1 in 6 M KOH. Zhang

et al [

123] also reported a one-step method for the preparation of nitrogen and phosphorus co-doped porous BDC from chitosan, with phosphoric acid as an activator, phosphorus source, and cross-linking agent, where chitosan was the carbon matrix and a nitrogen source. The resultant carbon exhibited a specific capacitance of 350 F g

−1 at 1 A g

−1. Bamboo waste-derived N, P co-doped porous carbon could be fabricated by a facile one-step carbonization and activation approach, where K

2CO

3, urea, and Na

2HPO

4 and bamboo cellulose were heated at 600 °C for 2 hours [

124]. It could be used as the positive electrode of zinc-ion hybrid capacitors.

There are also some novel methods developed by researchers. These methods are strongly dependent on the special features of the precursor. For the biomass materials with low ignition points and flammable features, such as cotton, dandelion, and catkin, hierarchical porous carbon could be rapidly prepared using them as precursors by flame burning carbonization in air with the assistance of molten salt (K

2CO

3-KCl) as fire retardant [

125]. The salts played the role of activator and templates. The porous carbon had a large specific surface area and abundant heteroatoms doping, and had a high specific capacitance of 367 F g

−1 in 6 M KOH. Meanwhile, a new electrolyte of K

2CO

3-glycol-arginine was developed to show a large voltage window in a wide temperature range from −25 to 100 °C. Wang

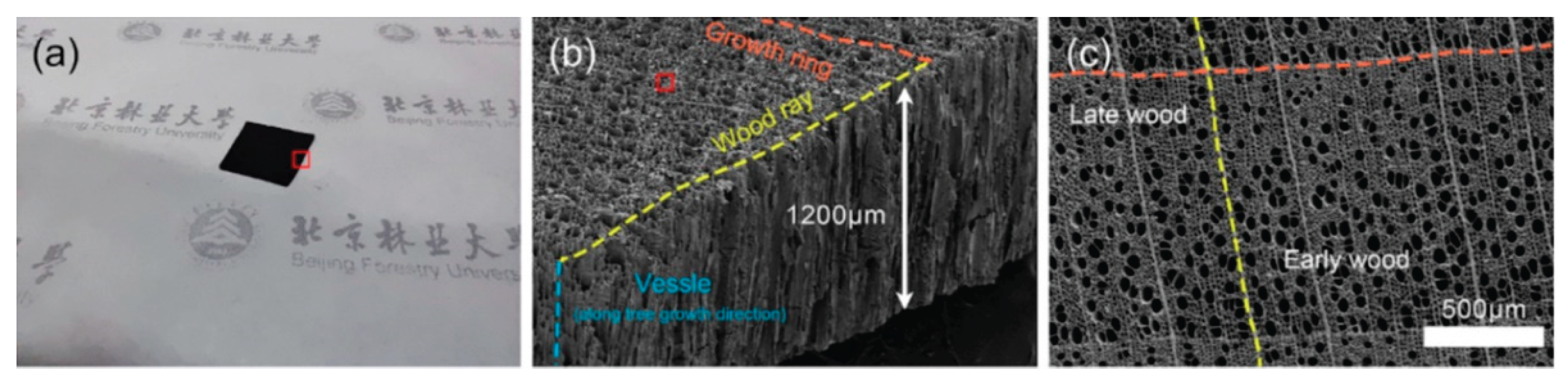

et al [

126] applied an environmentally friendly activation method for the preparation of free-standing carbon electrodes from basswood. An ultra-thick carbon electrode (1200 μm) with a high specific surface area of 766 m

2 g

−1 and a multiscale pore structure could be successfully fabricated, as displayed in

Figure 10.

Figure 10a marks the scanned area of the carbon electrode. An isometric view in

Figure 10b demonstrates the preservation of the natural structure of wood. A top view SEM image of the wood electrode in

Figure 10c shows a growth ring, showcasing the diffuse-porous nature of basswood. This characteristic endows superior water transport efficiency in both earlywood and latewood areas. The electrode demonstrated a specific capacitance of 211 F g

−1 at a current density of 1 mA cm

−2 in 6 M KOH.

Meanwhile, a new heating approach with rapid rates was used to treat biomass materials. Wang

et al [

127] reported the rapid production of N, O-doped porous carbon via electromagnetic pyrolysis using enteromorpha as a carbon source. Compared with the conventional pyrolysis, the ultra-fast heating and quenching processes, coupled with the use of a closed high-pressure environment in electromagnetic pyrolysis, could improve the degree of interaction between carbon precursors and the activator (KOH) and physical activators. The resultant carbon had porous structures with high surface areas and high-level heteroatom doping.

6. Future Directions and Conclusions

In this review paper, we delved into the recent research related to porous carbon from biomass for supercapacitors, especially occurred in the last three years. This work highlights the significant roles of BDC for energy storage application. Biomass materials are very good and renewable resources for preparing porous carbon as supercapacitor electrodes, because biomass is the most abundant renewable resource on Earth. The full utilization of biomass wastes can not only boost the economy but also effectively reduce environmental pollution.

Among the key factors influencing BDC electrochemical performance, specific surface areas and pore structures play critical roles. Thus, advanced porous BDC of excellent supercapacitive performance can be synthesized by using chemical activation methods using some typical chemicals such as KOH to adjust surface area and graphitization degree. However, it has little control over the pore geometry, pore size and pore connection. The corrosive features under elevated temperatures are harmful to environment, equipment and workers. Thus, physical activation is more suitable for large scale production with negligible environmental impacts, though its activation efficiency is not as prominent as that of the chemical method and its consumed energy is quite more than that of the chemical process.

Considering the diversity of biomass resources, the BDC from animal bones and excreta is of rich heteroatoms and by-products, and thus additional complicated processes are necessary to purify it. Microorganisms are not popularly used as raw materials of BDC due to its high cost. Thus, plants and their derivatives are more suitable for commercialization, because they have rapid growth rates and wealth of pipeline structures along the growth direction, guaranteeing abundant supply, low cost, porous features and high performance. The agricultural residue and food industrial wastes as the source of BDC are cheap and abundant. The fundamental research on the relationship between biomass composition and the electrochemical properties of resulting carbon is needed. It will be a good case to do this kind of study with cellulose-, lignin- and hemicellulose-derived carbon materials. However, the chemical compositions content is different from various plants organs. For some plants, they may contain some bits of inorganics (such as Ca, K, Mg, Na, Fe, Mn and Si) during the growth and it is hard to remove it such as SiO2 by the conventional purification method. Meanwhile, the ratio of mineral elements in biomass is varied depended on the biomass species or organs and the soil. Thus, the mass specific capacitance of BDC will be reduced due to presence of the inert impurities. To obtain advanced BDC materials, a purification process will be inevitable.

The methods to improve the specific capacitance of BDC have been well developed. Part of heteroatom doping in the BDC material can enhance its wettability and pseudocapacitive behavior. However, some heteroatom sources can be self-sourced and some are additional added. The doping content is not easily controlled, typically for the former case, because of the diverse chemical compositions. The dopants after treatment without any residual are especially welcome. Though the composites of BDC serving as a structural scaffold and guest pseudocapacitive materials such as metal oxides, metal sulfides, and conductive polymers, can have higher specific capacitances than single BDC, the chiefly electrochemical shortcomings of pseudocapacitive materials still exist.

These new processes developed to prepare or treat BDC are mainly to well control the pore structure in BDC particles and functional groups on the surface. Researchers are interested in the effects of pore size, specific surface area and surface chemistry on the electrochemical behavior of BDC. Investigating the diffusion process of ions in hierarchical pore structures is still of significance. These functional groups on carbon surface can endow a little pseudo-capacitance, however, its contribution is not very prominent.

A high graphitization degree will lead to a small specific surface area and an undeveloped pore structure, as well as a hydrophobic surface. Thus, there should be a balance state between the graphitization degree and pore structure in order to maximize the electrochemical performance. Compared with the thermal treatment under much high temperatures, catalytic graphitization with transition metal as catalyst is a more efficient route to prepare BDC with a certain graphitization degree. In addition to, modifying the mass content of cellulose in the biomass can modulate the graphitization degree of BDC.

Although the two-step process including pyrolysis and activation has been well accepted by researchers, some special processes are also explored and the main aim is to improve the efficiency. Some methods are designed and it is strongly dependent on the special features of the biomass precursor. In addition to improving the specific capacitance, the energy density of SCs can be also enhanced by widening the operation voltage by using ionic liquids as electrolytes or configuring asymmetric capacitors.

There are considerable economic and technical challenges to overcome for BDC in supercapacitor application. The reported BDC electrode materials with good supercapacitive performance are mostly prepared at the lab scale. There is an urgent need to carry out scale-up research to meet the further development of the technology. During the large scale production of BDC, the biomass with cheap and abundant sources like agriculture waste and food industrial by-product (e.g., coconut shells, bamboo, and straw) is very promising. However, the homogeneity of the resultant BDC should be also paid much attention because of the variation of the chemical compositions originated from the growth conditions and regions. Future advancements related to BDC for SCs tightly depend on improving processing technologies and cost-effective production methods.

In summary, the specific surface area, pore structure, surface groups, heteroatom doping, graphitization degree of BDC play crucial roles in determining the electrochemical performance. These synergistic approaches that combine theoretical modeling with experimental validation to guide the design of BDC with enhanced structural and electrochemical properties are urgently required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., J.X. and J.C.; methodology, A.L.; formal analysis, A.L.; resources, J.C.; data curation, J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.; writing—review and editing, J.C.; visualization, J.X.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the significant science and technology projects of LongMen Laboratory in Henan Province (231100221100).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Senthil, C; Lee, C.W. Biomass-derived biochar materials as sustainable energy sources for electrochemical energy storage devices. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 137, 110464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiolari, L.; Sampo, M.; Lamberti, A.; Amici, J.; Francia, C.; Bodoardo, S.; Bella, F. Integrated energy conversion and storage devices: Interfacing solar cells, batteries and supercapacitors. Energy Storage Materials 2022, 51, 400–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Han, X.; Zhang, C.; He, S.; Liu, K.; Hu, J.; Yang, W.; Jian, S.; Duan, G. Activation of biomass-derived porous carbon for supercapacitors: A review. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 35, 109007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Parveen, N.; Ansari, M.; Alsulaim, G.; Alam, M.; Khan, M.; Umar, A.; Hussain, I.; Zhang, K. Exploring recent advances in the versatility and efficiency of carbon materials for next generation supercapacitor applications: A comprehensive review. Progress in Materials Science, 2025, 154, 101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Gui, L.; Lu, C. Recent progress and future directions of biomass-derived hierarchical porous carbon: designing, preparation, and supercapacitor applications. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 3523–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lv, T.; Qiu, J. High mass-loading biomass-based porous carbon electrodes for supercapacitors: review and perspectives. Small 2023, 19, 2300336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Si, Y.; Zhao, C.; Chen, T.; Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, K. Biomass-derived carbon applications in the field of supercapacitors: Progress and prospects. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2024, 495, 153311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, W; Wang, X. ; Liu, F. Recent research of core–shell structured composites with NiCo2O4 as scaffolds for electrochemical capacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 393, 124747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zheng, J.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Ding, Y.; Han, J.; Jiang, S.; He, S. Pore engineering: Structure-capacitance correlations for biomass-derived porous carbon materials. Materials & Design 2023, 229, 111904. [Google Scholar]

- Sonu; Rani, G. ; Pathania, D.; Abhimanyu; Umapathi, R.; Rustagi, S.; Huh, Y.; Gupta, V.; Kaushik, A.; Chaudhary, V. Agro-wasteto sustainable energy: A green strategy of converting agricultural waste to nano-enabled energy applications. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 875, 162667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, R.; Periasamy, A.P.; Schlee, P.; Herou, S.; Titirici, M.M. Lignin: A sustainable precursor for nanostructured carbon materials for supercapacitors. Carbon 2023, 207, 172–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, B.; Yang, G.; He, S.; Jiang, S.; Yang, H.; Han, J.; Li, X.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Q. Progress of 0D biomass-derived porous carbon materials produced by hydrothermal assisted synthesis for advanced supercapacitors. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2025, 685, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Biomass-derived carbon: synthesis and applications in energy storage and conversion. Green Chemistry, 2016, 18, 4828–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lee, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; He, S.; Han, J.; Ahn, J.; Cheong, J.; Jiang, S.; Kim, I. Inspired by wood: thick electrodes for supercapacitors. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 8866–8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hou, H.; Xu, W.; Duan, G.; He, S.; Liu, K.; Jiang, S. Recent progress in carbon-based materials for supercapacitor electrodes: a review. Jourmal of Materials Science 2021, 56, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, A.; Badhulika, S. Effect of self-doped heteroatoms on the performance of biomass-derived carbon for supercapacitor applications. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 480, 228830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Ma, L. Recent progress of biomass-derived carbon materials for supercapacitors. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 451, 227794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, Q.; Gao, S.; Tang, G.; Liu, K.; He, S.; Huang, C. Biomass derived carbon as binder-free electrode materials for supercapacitors. Carbon 2019, 155, 706–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; He, H.; Lv, T.; Qiu, J. Fabrication of biomass-based functional carbon materials for energy conversion and storage. Materials Science and Engineering: Report 2023, 154, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y. One-pot synthesis of biomass-derived porous carbons for multipurpose energy applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 6211–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Lu, L.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, B.; Zeng, X.; Xie, Y.; Ye, X. Preparation and outperformance of supercapacitive activated carbon from ternary biomass simulant. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yan, M.; Jiang, J.; Huang, A.; Cai, S.; Lan, L. , Ye, K.; Chen, D.; Tang, K.; Zuo, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Tang, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; He, Xi, Qiao, L.; Zhao, Y. A state-of-the-art review on biomass-derived carbon materials for supercapacitor applications: From precursor selection to design optimization. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 912, 169141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaiammart, N.; Vignesh, V.; Thu, M.M.; Eiad-ua, A.; Maiyalagan, T.; Panomsuwan, G. Chemically activated carbons derived from cashew nut shells as potential electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Carbon Resources Conversion 2025, 8, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.S.; Bhat, B.R. Biomass waste-derived porous graphitic carbon for high-performance supercapacitors. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 76, 109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmpes, N.; Tantis, I; Alsmaeil, A.W.; Aldakkan, B.S.; Dimitrakou, A.; Karakassides, M.A.; Salmas, C.E.; Giannelis, E.P. Elevating waste biomass: supercapacitor electrode materials derived from spent coffee grounds. Energy & Fuels 2025, 39, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Ni, C.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Fabrication of three-dimensional CuS2@CoNi2S4 core–shell rod-like structures as cathode and thistle-derived carbon as anode for hybrid supercapacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 465, 143024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, A.; Ma, R.; Guo, C.; Ding, X.; Feng, P.; Jia, D.; Xu, M.; Ai, L.; Guo, N.; Wang, L. Regulating the specific surface area and porous structure of carbon for high performance supercapacitors. Applied Surface Science 2023, 615, 156267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, W.; Hassan, M.; Pan, Y.; Guan, G.; Lopez-salaz, N.; Khalil, A. Sulfur and nitrogen co-doping of peanut shell-derived biochar for sustainable supercapacitor applications. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 991, 174452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.S.; Bhat, B.R. Sustainable energy storage: Mangifera indica leaf waste-derived activated carbon for long-life, high-performance supercapacitors. RSC Adv., 2024, 14, 8028–8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakshi, M.; Mujeeb, A.; Whale, J.; Evans, R.; Aughterson, R.; Hinde, P.; Ariga, K.; Shrestha, L. Synthesis of Porous Carbon Honeycomb Structures Derived from Hemp for Hybrid Supercapacitors with Improved Electrochemistry. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yang, X.; She, Z.; Wu, Q.; Shi, K.; Xie, Q.; Ruan, Y. Ultrahigh-surface-area and N,O co-doping porous carbon derived from biomass waste for high-performance symmetric supercapacitors. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 3110–3120. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, D.; Varadharajan, H.; Venugopal, I.P. Biomass-derived porous carbon from banana leaves for efficient supercapacitor applications – An experimental analysis. Biomass and Bioenergy 2025, 201, 108104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jrad, E.B.H.; Elmouwahidi, A.; Garcia, E.B.; Marin, F.C.; Dridi, C. Biosynthetized activated carbon for sustainable supercapacitors development using aqueous and solid state electrolytes. Journal of Power Sources 2025, 654, 237871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.F.; Huang, Y.Y.; Fan, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, P.; Lei, F.; Feng, Y.; Li, K.; Huang, Q. Dry-ball-milling-assisted activation of porous carbon derived from walnut green seedcases for high-performance supercapacitors and efficient adsorption of methylene blue. Diamond & Related Materials 2025, 159, 112724. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Wang, S.; Sheng, S. From Cynomorium songaricum residues to supercapacitors: A novel utilization strategy for biomass solid waste. Biomass and Bioenergy 2025, 202, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Re, D.; Tian, Y.; Shang, Z. Glucose-assisted grapevine-based ultrahigh microporosity activated hydrochar materials for supercapacitor electrodes. Renewable Energy 2025, 253, 123669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Wang, T.; Chen, B.; Wu, D. Lignin-Derived Deep Eutectic Solvent Gel Electrolytes Paired With Porous Carbon Electrodes for Advanced Supercapacitor Application. Small 2025, 21, 2500473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Bengoa, L.; Gonzalez-Gil, R.; Gomez-Romero, P. Optimization of porous carbon structure through high-temperature pyrolysis for enhanced electrochemical performance of supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2025, 536, 146722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, R.; Chen, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Pan, Y.; Wang, C. Potassium ferrioxalate mediated dual graphitization and activation of Semen Ziziphi Spinosae derived hierarchical carbon for high-performance supercapacitors. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 130, 117453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, X. Preparation of high specific surface area porous carbon from waste bamboo fiber for high performance supercapacitors. Biomass and Bioenergy 2025, 202, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Fu, Y.; Lei, W.; Chang, J. Preparation of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped tubular porous carbon derived from Ceiba speciosa flowers for supercapacitors. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 112, 115536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.; Khan, F.; Ayoub, Z.; Jain, A.; Gull, A. Recycling biowaste into energy storage: waste tea leaves-derived hierarchical porous activated carbon for supercapacitors. Journal of Power Sources 2025, 655, 237969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, D.; Aryal, S.; Shrestha, K.; Mishra, P.; Shrestha, T.; Homagai, P.; Oli, H.; Shrestha, R. Study of the electrochemical performance of Zanthoxylum armatum seed-derived potassium hydroxide-assisted activated carbon as a negatrode material for supercapacitor applications. Mater. Adv., 2025, 6, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Chen, Z.; Jin, R.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Lin, X.; Peng, Y. Sustainable synthesis of hierarchical porous carbon from deoiled camphor leaves via cellulase hydrolysis and potassium bicarbonate activation for high-performance supercapacitors. Bioresource Technology 2025, 433, 132730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Hossain, S.; Choudhury, A.; Yang, D.; Ali, S.; Mohsin, M. Synthesis of activated N/O/S-codoped porous carbon from waste sugarcane bagasse cellulose for high energy density solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2025, 147, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; He, N.; Xie, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Wang, K.; Pan, H.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Q. Tailoring waste sawdust-derived porous carbon through varying glycosidic bond cleavage: Analysis of pore structure mechanism and applications in supercapacitors and dye removal. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2025, 191, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Feng, Q.; Wang, D.; Ma, D. A combination of heteroatom doping engineering assisted by molten salt and KOH activation to obtain N and O co-doped biomass porous carbon for high performance supercapacitors. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 960, 170785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Peng, J.; Lei, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, P.; Zeng, J.; Yi, C.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X. Activated carbon derived from the Agricultural waste camellia seed shell for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Kang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Sun, T.; Deng, F.; Liu, D. Sunflower plate-derived activated porous carbon for high-performance supercapacitors: The structure-performance relationship based on activator regulation. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ye, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Fang, W.; Qiu, J. All-in-one biomass-based flexible supercapacitors with high rate performance and high energy density. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qu, Y.; Bai, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Q.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Yang, W. High-yield ramie derived carbon toward high-performance supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2024, 120, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Xia, J.; Yan, D.; Diao, R.; Zha, Z.; Qi, F.; Ma, P. Biomass-based 2D porous carbon with cross-linked nanosheets via co-hydrothermal pretreatment for high-performance supercapacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 519, 165145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Qiu, B.; Xu, L.; Qin, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Wei, F.; Lv, Y. High performance hierarchical porous carbon derived from waste shrimp shell for supercapacitor electrodes. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, S. Sustainable carbon from marine sponge waste for high-performance supercapacitors: Surface-specific insights on glassy carbon and boron-doped diamond electrodes. Diamond & Related Materials 2025, 158, 112659. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xue, S.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Ou, Y.; Zhu, B.; Demir, M. Silk-derived nitrogen-doped porous carbon electrodes with enhanced ionic conductivity for high-performance supercapacitors. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 645, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, Q.; Feng, W.; Li, S.; Huo, L.; Guo, Z.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Y. Iron oxide quantum dots-modified biomass carbon: enabling high-performance supercapacitors. Adv. Sustainable Syst. 2025, e00624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lian, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, H. Flexible porous carbon nanofibers derived from cuttlefish ink as self-supporting electrodes for supercapacitors. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 599, 234216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzana, M.; Ribeiro, T.; Ladislao, M.; Saczk, A. Dias, E.; Silva, J.; Bufalo, T. Fungi-derived Ag nanoparticle-anchored carbon electrode material toward electrochemical supercapacitors. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2025, 996, 119362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]