Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A Missing Link: The Role of Vitamin C in Insulin Sensitivity

- synthesizing carnitine[24]

1.2. Cortisol, Stress, and Insulin Coupling

1.3. A Unified Model: The Insulin–Cortisol–Vitamin C (ICV) Axis

1.4. Purpose of This Review

2. Physiology of Insulin Regulation

2.1. Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS)

2.2. Non-Glucose Mediators of Insulin Secretion

- Incretins (GLP-1, GIP)

- Amino acids and dietary proteins

- Free fatty acids (FFAs)

2.3. Insulin Sensitivity and Tissue Uptake

- skeletal muscle

- adipose tissue

- liver (indirectly via suppression of hepatic glucose output)

- physical activity

- mitochondrial function

- oxidative stress

- inflammation

- adipokines (adiponectin, leptin)

- magnesium sufficiency

- stress hormones (especially cortisol)

2.4. Insulin Resistance: A Multifactorial Process

- Oxidative stress

- Inflammation

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- Lipotoxicity / Ectopic fat

- Circadian disruption

- Chronic stress & cortisol elevation

2.5. Insulin Variability and Fluctuations Matter

2.6. Vitamin C as a Modulator of Insulin Physiology

- Support of GLUT4 activation and glucose uptake, partly through antioxidant protection of skeletal muscle and pancreatic β-cells, and through improved mitochondrial redox status[9].

- Augmentation of endothelial nitric oxide activity, mediated by preservation of tetrahydrobiopterin and reduction of NO oxidative degradation, which improves insulin-mediated vasodilation and tissue glucose delivery[30].

- Supplementation lowers fasting glucose, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HbA1c, and serum insulin in type 2 diabetes, suggesting improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity[96].

3. Evidence Linking Vitamin C Status and Insulin Sensitivity

3.1. Observational Evidence: Vitamin C Levels Inversely Correlate with Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome

3.2. Interventional Trials: Vitamin C Supplementation Improves Glycemic Control and Insulin Biomarkers

3.3. Mechanistic Studies Demonstrating Improvements in Insulin Signaling

- Reduction of Oxidative Stress: Vitamin C decreases reactive oxygen species that otherwise impair insulin receptor substrate (IRS) phosphorylation and downstream signaling, thereby maintaining insulin responsiveness[93].

3.4. Endothelial Function: Vitamin C Enhances NO Bioavailability and Insulin-Mediated Vasodilation

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Effects: Vitamin C Reduces Cytokines That Impair Insulin Signaling

3.6. Summary of Evidence

- reduction of oxidative stress

- enhancement of GLUT4 activation and glucose uptake

- mitochondrial support and metabolic flexibility

- improvement of endothelial NO-dependent vasodilation

- suppression of inflammatory pathways that impair insulin receptor activity

4. The Insulin–Cortisol–Vitamin C (ICV) Axis: A Unified Regulatory Framework

4.1. Bidirectional Coupling Between Insulin and Cortisol

4.2. The Central Role of Vitamin C in Adrenal Physiology and Cortisol Regulation

4.3. Vitamin C as a Regulator of Insulin Sensitivity

- oxidative stress reduction

- preservation of insulin receptor function

- enhancement of GLUT4-mediated glucose uptake

- mitochondrial redox support

- maintenance of endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability

- suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines

4.4. Integration of Insulin, Cortisol, and Vitamin C: A Systems Physiology Model

4.4.1. Core Relationships

- Cortisol → Insulin: cortisol elevation increases glucose output and insulin secretion.

- Insulin → Cortisol: hyperinsulinemia amplifies central HPA-axis activation and promotes visceral adiposity, further elevating cortisol.

- Cortisol → Vitamin C: cortisol directly increases intracellular vitamin C levels by stimulating the synthesis of vitamin C transporters and resulting in an anti-inflammatory impact in cells and tissues.

- Vitamin C → Cortisol: vitamin C regulates cortisol synthesis and shutdown; deficiency prolongs cortisol elevation.

- Vitamin C → Insulin: vitamin C improves insulin sensitivity via oxidative stress reduction, GLUT4 facilitation, mitochondrial support, and endothelial function.

- Insulin → Vitamin C: hyperglycemia and oxidative load increase vitamin C turnover, depleting tissue reserves.

4.4.2. The Dysregulation Cycle

- 1.

- Stress → cortisol ↑

- 2.

- Cortisol ↑ → glucose ↑ → insulin ↑

- 3.

- Insulin ↑ → oxidative stress ↑ → vitamin C depletion

- 4.

- Vitamin C ↓ → impaired cortisol regulation + reduced insulin sensitivity

- 5.

- Cycle repeats, leading to entrenched metabolic dysfunction.

- persistently high insulin despite low-carbohydrate diets

- stress-related metabolic deterioration

- mitochondrial dysfunction

- endothelial dysfunction

- BHRT instability (via SHBG alterations, thyroid conversion issues, and altered adrenal output)

- heterogeneity in response to GLP-1 receptor agonists

- metabolic syndrome and fatigue syndromes refractory to standard treatment

4.5. Clinical Relevance of the ICV Axis

- Low-carb nonresponders

- elevated cortisol

- low vitamin C status

- increased oxidative stress

- inflammation or sleep disruptionThe ICV model explains persistent insulin resistance in this subgroup.

- BHRT instability

- SHBG levels

- free estrogen/testosterone

- progesterone sensitivity

- thyroid conversion

- Metabolic syndrome & cardiometabolic risk

- hyperinsulinemia

- central adiposity

- endothelial dysfunction

- hypertension

- dyslipidemia

- GLP-1 agonist variability

4.6. Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

- biomarker development (vitamin C status, cortisol rhythms, oxidative stress indices)

- clinical trials (vitamin C repletion + stress modulation + metabolic therapy)

- personalized medicine approaches integrating diet, micronutrition, and endocrine regulation

4.7. Summary of Section 4

5. Integrating the ICV Axis Into Existing BHRT Frameworks

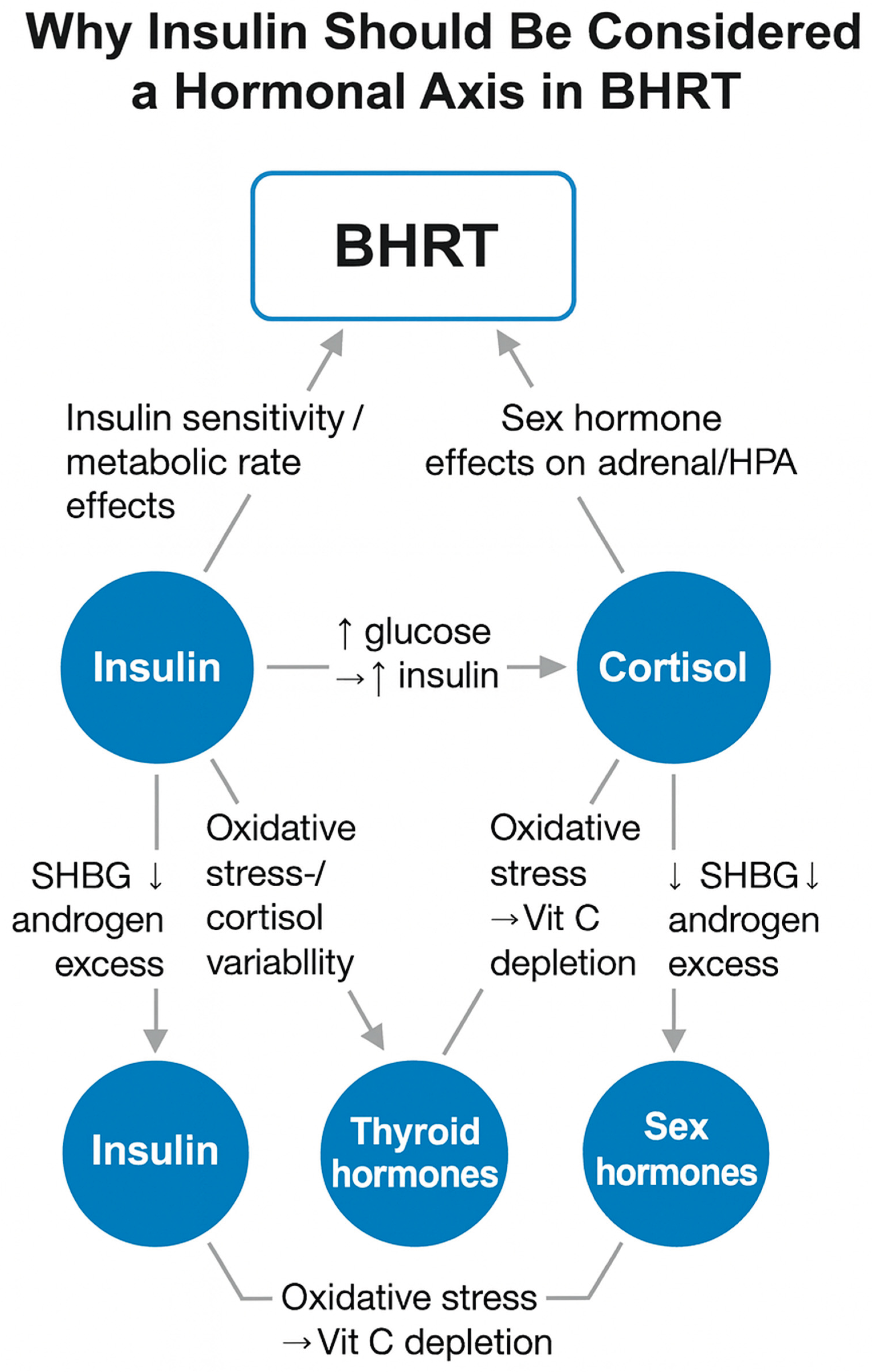

5.1. Why Insulin Should Be Considered a Hormonal Axis in BHRT

5.2. How Cortisol Links Insulin and Sex Hormone Physiology

5.3. A Critical Missing Component: Vitamin C in BHRT Physiology

5.4. Why Existing BHRT Models Fail Without Insulin–Cortisol–Vitamin C Integration

- inconsistent symptom improvement

- persistent fatigue

- continued weight gain

- elevated inflammatory markers

- fluctuating hot flashes or night sweats

- unstable mood

- reduced libido

- plateaued metabolic progress

5.5. Practical Integration: Updating BHRT to the ICV Model

- Legend:

- Blue circles = key hormonal/metabolic nodes

- Blue rounded rectangle = BHRT regulatory inputs

- Gray arrows = primary directional influences

- Dashed arrows (if present) = feedback effects

- Labels = dominant mechanistic pathways (e.g., ↑ glucose → ↑ insulin; oxidative stress → vitamin C depletion; SHBG ↓ → androgen excess)

5.6. Summary: Why This Is a Landmark Advancement in BHRT

- more effective interventions

- fewer treatment failures

- better metabolic outcomes

- improved patient resilience

- a unified model connecting nutrition, hormones, stress physiology, and redox biology

6. Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

6.1. Implications for Endocrinology and BHRT Practice

6.2. Implications for Metabolic and Nutritional Medicine

6.3. Implications for Cardiometabolic and Chronic Disease Care

6.4. Implications for Lifestyle, Stress, and Circadian Medicine

6.5. A New Conceptual Lens for Integrative Orthomolecular Medicine (IOM)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rains, J.L.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative Stress, Insulin Signaling, and Diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 2011, 50, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.L.; Goldfine, I.D.; Maddux, B.A.; Grodsky, G.M. Are Oxidative Stress−Activated Signaling Pathways Mediators of Insulin Resistance and β-Cell Dysfunction? Diabetes 2003, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin, O.; Raz, M.; Tendler, A.; Bar, A.; Korem Kohanim, Y.; Milo, T.; Alon, U. A New Model for the HPA Axis Explains Dysregulation of Stress Hormones on the Timescale of Weeks. Mol Syst Biol 2020, 16, e9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.A.; Stromin, J.I.; Steenkamp, N.; Combrinck, M.I. Understanding the Relationships between Physiological and Psychosocial Stress, Cortisol and Cognition. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1085950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.S.; Doom, J.R.; Farrell, A.K.; Carlson, E.A.; Englund, M.M.; Miller, G.E.; Gunnar, M.R.; Roisman, G.I.; Simpson, J.A. Life Stress and Cortisol Reactivity: An Exploratory Analysis of the Effects of Stress Exposure across Life on HPA-Axis Functioning. Dev Psychopathol 2021, 33, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Kluwe, B.; Lazarus, S.; Teruel, M.N.; Joseph, J.J. Cortisol and Cardiometabolic Disease: A Target for Advancing Health Equity. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2022, 33, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, R.A.; Kivimäki, M.; Kumari, M.; Steptoe, A. Diurnal Cortisol Patterns, Future Diabetes, and Impaired Glucose Metabolism in the Whitehall II Cohort Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maury, E.; Ramsey, K.M.; Bass, J. Circadian Rhythms and Metabolic Syndrome: From Experimental Genetics to Human Disease. Circ Res 2010, 106, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.-Y.; Ima-Nirwana, S. Vitamin C: A Review on Its Role in the Management of Metabolic Syndrome. Int J Med Sci 2020, 17, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ding, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y. Vitamin C and Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, M.; Ghaffari, G.; Hashemipour, M.; Mostofizadeh, N.; Koushki, A.M. Effect of Long-Term Vitamin C Intake on Vascular Endothelial Function in Diabetic Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study. J Res Med Sci 2016, 21, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.A.; Keske, M.A.; Wadley, G.D. Effects of Vitamin C Supplementation on Glycemic Control and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People With Type 2 Diabetes: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.M.; Harrison, F.E. Role of Vitamin C in the Function of the Vascular Endothelium. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 19, 2068–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beglaryan, N.; Hakobyan, G.; Nazaretyan, E. Vitamin C Supplementation Alleviates Hypercortisolemia Caused by Chronic Stress. Stress Health 2024, 40, e3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, P.E. Vitamin C: An Essential “Stress Hormone” during Sepsis. J Thorac Dis 2020, 12 (Suppl 1), S84–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooraei, N.; Fathi, M.; Edalat, L.; Behnaz, F.; Mohajerani, S.A.; Dabbagh, A. Effect of Vitamin C on Serum Cortisol after Etomidate Induction of Anesthesia.

- Panahi, J.R.; Paknezhad, S.P.; Vahedi, A.; Shahsavarinia, K.; Laleh, M.R.; Soleimanpour, H. Effect of Vitamin C on Adrenal Suppression Following Etomidate for Rapid Sequence Induction in Trauma Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2023, 23, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patak, P.; Willenberg, H.S.; Bornstein, S.R. Vitamin C Is an Important Cofactor for Both Adrenal Cortex and Adrenal Medulla. Endocr Res 2004, 30, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmann, A.; Möbius, K.; Hiller, H.H.; Oelkers, W.; Bähr, V. Ascorbate Depletion Prevents Aldosterone Stimulation by Sodium Deficiency in the Guinea Pig. Eur J Endocrinol 1995, 133, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Saxena, J.; Srivastava, V.K.; Kaushik, S.; Singh, H.; Abo-El-Sooud, K.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Jyoti, A.; Saluja, R. The Interplay of Oxidative Stress and ROS Scavenging: Antioxidants as a Therapeutic Potential in Sepsis. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Xu, Y.; Liehn, E.A.; Rusu, M. Vitamin C as Scavenger of Reactive Oxygen Species during Healing after Myocardial Infarction. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Kunert, K. The Ascorbate-Glutathione Cycle Coming of Age. J Exp Bot 2024, 75, 2682–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Anee, T.I.; Parvin, K.; Nahar, K.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M. Regulation of Ascorbate-Glutathione Pathway in Mitigating Oxidative Damage in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouche, C.J. Ascorbic Acid and Carnitine Biosynthesis. Am J Clin Nutr 1991, 54 (6 Suppl), 1147S–1152S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumailley, L.; Bourassa, S.; Gotti, C.; Droit, A.; Lebel, M. Vitamin C Modulates the Levels of Several Proteins of the Mitochondrial Complex III and Its Activity in the Mouse Liver. Redox Biol 2022, 57, 102491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.; Min, S.; Huang, J.; Zou, M.; Zhou, D.; Liang, Y. High-Dose Vitamin C Promotes Mitochondrial Biogenesis in HCT116 Colorectal Cancer Cells by Regulating the AMPK/PGC-1α Signaling Pathway. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2025, 151, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan Nair, V.; Huehn, J. Impact of Vitamin C on the Development, Differentiation and Functional Properties of T Cells. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp) 2024, 14, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, G.; Negro, M.; Parimbelli, M.; Pecoraro, M.; Perna, S.; Liguori, G.; Rondanelli, M.; Cena, H.; D’Antona, G. The Long History of Vitamin C: From Prevention of the Common Cold to Potential Aid in the Treatment of COVID-19. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 574029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesahat, F.; Norouzi, E.; Seifati, S.M.; Hamidian, S.; Hosseini, A.; Zare, F. Impact of Vitamin C on Gene Expression Profile of Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Male Partners of Couples with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Int J Inflam 2022, 2022, 1222533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uscio, L.V. d’; Milstien, S.; Richardson, D.; Smith, L.; Katusic, Z.S. Long-Term Vitamin C Treatment Increases Vascular Tetrahydrobiopterin Levels and Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity. Circ Res 2003, 92, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddei, S.; Virdis, A.; Ghiadoni, L.; Magagna, A.; Salvetti, A. Vitamin C Improves Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilation by Restoring Nitric Oxide Activity in Essential Hypertension. Circulation 1998, 97, 2222–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J.A.; Sutherland, W.H.F.; McCormick, M.P.; Jong, S.A. de; McDonald, J.R.; Walker, R.J. Vitamin C Improves Endothelial Dysfunction in Renal Allograft Recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001, 16, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitani, F.; Ogishima, T.; Mukai, K.; Suematsu, M. Ascorbate Stimulates Monooxygenase-Dependent Steroidogenesis in Adrenal Zona Glomerulosa. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2005, 338, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Iguchi, T.; Itoh, N.; Okamoto, K.; Takagi, T.; Tanaka, K.; Nakanishi, T. Ascorbic Acid Transported by Sodium-Dependent Vitamin C Transporter 2 Stimulates Steroidogenesis in Human Choriocarcinoma Cells. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Park, S. A Causal Relationship between Vitamin C Intake with Hyperglycemia and Metabolic Syndrome Risk: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Hosseini, F.; Namkhah, Z.; Mohammadi, S.; Salamat, S.; Nadery, M.; Yarmand, S.; Zamani, M.; Wong, A.; Asbaghi, O. The Effects of Vitamin C Supplementation on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2023, 17, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schernthaner-Reiter, M.H.; Wolf, P.; Vila, G.; Luger, A. The Interaction of Insulin and Pituitary Hormone Syndromes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T.C.; Hasson, R.E.; Ventura, E.E.; Toledo-Corral, C.; Le, K.-A.; Mahurkar, S.; Lane, C.J.; Weigensberg, M.J.; Goran, M.I. Cortisol Is Negatively Associated with Insulin Sensitivity in Overweight Latino Youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, 4729–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, E.B.; Islam, J.; Buettner, C. Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Induced Insulin Resistance: Focus on Adipose Tissue Function and Lipid Metabolism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2014, 43, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Maleki, M.; Butler, A.E.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Stress and Insulin Resistance. EXCLI J 2022, 21, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, M.; Takei, M.; Ishii, H.; Sato, Y. Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion: A Newer Perspective. J Diabetes Investig 2013, 4, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plecitá-Hlavatá, L.; Jabůrek, M.; Holendová, B.; Tauber, J.; Pavluch, V.; Berková, Z.; Cahová, M.; Schröder, K.; Brandes, R.P.; Siemen, D.; Ježek, P. Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion Fundamentally Requires H2O2 Signaling by NADPH Oxidase 4. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa Maheshvare, M.; Raha, S.; König, M.; Pal, D. A Pathway Model of Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in the Pancreatic β-Cell. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1185656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, L. Biphasic Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion over Decades: A Journey from Measurements and Modeling to Mechanistic Insights. Life Metab 2025, 4, loae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.K. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Applications of GLP-1 and Dual GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1431292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimann, F.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Hodge, D.; Gribble, F.M. Cellular Mechanisms Governing Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Secretion. Peptides 2020, 125, 170206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J.; Rosenkilde, M.M. GIP as a Therapeutic Target in Diabetes and Obesity: Insight From Incretin Co-Agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, e2710–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Krause, M. Nutritional Regulation of Insulin Secretion: Implications for Diabetes. Clin Biochem Rev 2012, 33, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, C. Mechanisms of Amino Acid-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in Congenital Hyperinsulinism. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2013, 45, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Kawamata, Y.; Harada, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Fujii, R.; Fukusumi, S.; Ogi, K.; Hosoya, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Uejima, H.; Tanaka, H.; Maruyama, M.; Satoh, R.; Okubo, S.; Kizawa, H.; Komatsu, H.; Matsumura, F.; Noguchi, Y.; Shinohara, T.; Hinuma, S.; Fujisawa, Y.; Fujino, M. Free Fatty Acids Regulate Insulin Secretion from Pancreatic Beta Cells through GPR40. Nature 2003, 422, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-F. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in the Endocrine Regulation of Glucose Metabolism: Insight from Gastrointestinal-Pancreatic-Adipose Interactions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 956277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honka, M.-J.; Latva-Rasku, A.; Bucci, M.; Virtanen, K.A.; Hannukainen, J.C.; Kalliokoski, K.K.; Nuutila, P. Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle, Adipose Tissue and Liver: A Positron Emission Tomography Study. Eur J Endocrinol 2018, 178, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadt, A.; Al-Hasani, H. Glucose Transporters in Adipose Tissue, Liver, and Skeletal Muscle in Metabolic Health and Disease. Pflugers Arch 2020, 472, 1273–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chutia, H.; Lynrah, K.G. Association of Serum Magnesium Deficiency with Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Lab Physicians 2015, 7, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Tripathy, D. Skeletal Muscle Insulin Resistance Is the Primary Defect in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32 (suppl_2), S157–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, S.; Kushner, H.; Falkner, B. Low Dietary Magnesium Is Associated with Insulin Resistance in a Sample of Young, Nondiabetic Black Americans*. Am J Hypertens 1999, 12, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooren, F.C.; Krüger, K.; Völker, K.; Golf, S.W.; Wadepuhl, M.; Kraus, A. Oral Magnesium Supplementation Reduces Insulin Resistance in Non-Diabetic Subjects - a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011, 13, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Sahebkar, A.; Rodríguez-Morán, M.; Guerrero-Romero, F. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on the Effects of Magnesium Supplementation on Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose Control. Pharmacol Res 2016, 111, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, E.; Iozzo, P.; Virtanen, K.A.; Honka, M.-J.; Bucci, M.; Nuutila, P. Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle Insulin-Mediated Glucose Uptake in Insulin Resistance: Role of Blood Flow and Diabetes. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018, 108, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOERSMA, G.J.; HEURLING, K.; PEREIRA, M.J.; JOHANSSON, E.; LUBBERINK, M.; KATSOGIANNOS, P.; SKRTIC, S.; KULLBERG, J.; AHLSTRÖM, H.; ERIKSSON, J.W. Glucose Uptake in Muscle, Visceral Adipose Tissue, and Brain Strongly Predict Whole-Body Insulin Resistance in the Development of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2018, 67 (Supplement_1), 1790-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, E.J.; Diamond-Stanic, M.K.; Marchionne, E.M. Oxidative Stress and the Etiology of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 2011, 51, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrle, S.; Hsu, W.H. The Etiology of Oxidative Stress in Insulin Resistance. Biomed J 2017, 40, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangvarasittichai, S. Oxidative Stress, Insulin Resistance, Dyslipidemia and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. World J Diabetes 2015, 6, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadi, A.; Bellia, A.; Di Daniele, N.; Meloni, M.; Lauro, R.; Della-Morte, D.; Lauro, D. The Molecular Link between Oxidative Stress, Insulin Resistance, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Target for New Therapies against Cardiovascular Diseases. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2022, 62, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorenza, M.; Onslev, J.; Henríquez-Olguín, C.; Persson, K.W.; Hesselager, S.A.; Jensen, T.E.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.P.; Hostrup, M.; Bangsbo, J. Reducing the Mitochondrial Oxidative Burden Alleviates Lipid-Induced Muscle Insulin Resistance in Humans. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadq4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesupatham, A.; Saraswathy, R. Role of Oxidative Stress in Prediabetes Development. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 43, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangwung, P.; Petersen, K.F.; Shulman, G.I.; Knowles, J.W. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Insulin Resistance, and Potential Genetic Implications: Potential Role of Alterations in Mitochondrial Function in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergi, D.; Naumovski, N.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Abeywardena, M.; O’Callaghan, N.; Lionetti, L.; Luscombe-Marsh, N. Mitochondrial (Dys)Function and Insulin Resistance: From Pathophysiological Molecular Mechanisms to the Impact of Diet. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.K.; Turner, N. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance: An Update. Endocr Connect 2015, 4, R1–R15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Mei, Z.; Deng, Y. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Diabetes Mellitus and Complications: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Cell Death Dis 2025, 16, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Roles of Diacylglycerols and Ceramides in Hepatic Insulin Resistance. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2017, 38, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowska, E.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A. The Role of Ceramides in Insulin Resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szendroedi, J.; Yoshimura, T.; Phielix, E.; Koliaki, C.; Marcucci, M.; Zhang, D.; Jelenik, T.; Müller, J.; Herder, C.; Nowotny, P.; Shulman, G.I.; Roden, M. Role of Diacylglycerol Activation of PKCθ in Lipid-Induced Muscle Insulin Resistance in Humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 9597–9602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leproult, R.; Holmbäck, U.; Van Cauter, E. Circadian Misalignment Augments Markers of Insulin Resistance and Inflammation, Independently of Sleep Loss. Diabetes 2014, 63, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, F.; De Vito, F.; Cassano, V.; Fiorentino, T.V.; Sciacqua, A.; Hribal, M.L. Circadian Clock Desynchronization and Insulin Resistance. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.T.; Kondo, T.; Ashry, A.; Fu, Y.; Okawa, H.; Sawangmake, C.; Egusa, H. Effect of Circadian Clock Disruption on Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Yang, J.N.; Garcia, J.I.; Myers, S.; Bozzi, I.; Wang, W.; Buxton, O.M.; Shea, S.A.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. Endogenous Circadian System and Circadian Misalignment Impact Glucose Tolerance via Separate Mechanisms in Humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, E2225–E2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Chauhan, R.; Devi, S. Biological Connection of Circadian Rhythm and Insulin Resistance: A Review. Biological Rhythm Research 2025, 56, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaupere, C.; Liboz, A.; Fève, B.; Blondeau, B.; Guillemain, G. Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Induced Insulin Resistance. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, L.; Ye, J.; Niu, X.; Jiang, H.; Gan, S.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Z. Metabolic Syndrome Associated with Higher Glycemic Variability in Type 1 Diabetes: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in China. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Shen, R.; Zhang, M. Glycemic Variability in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Case-Control Study. Ann Med 2025, 57, 2548976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, J.E.; Moro, C.; Ravussin, E. Metabolic Flexibility and Insulin Resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008, 295, E1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscemi, S.; Verga, S.; Cottone, S.; Azzolina, V.; Buscemi, B.; Gioia, D.; Cerasola, G. Glycaemic Variability and Inflammation in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. Acta Diabetol 2009, 46, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, A.A.; Perelman, D.; Park, H.; Wu, Y.; Jha, A.; Sharp, S.; Celli, A.; Ayhan, E.; Abbasi, F.; Gloyn, A.L.; McLaughlin, T.; Snyder, M.P. Prediction of Metabolic Subphenotypes of Type 2 Diabetes via Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Machine Learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2025, 9, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiso, K.; Shayo, S.C.; Kawade, S.; Hashiguchi, H.; Deguchi, T.; Nishio, Y. Repeated Glucose Spikes and Insulin Resistance Synergistically Deteriorate Endothelial Function and Bardoxolone Methyl Ameliorates Endothelial Dysfunction. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0263080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Node, K.; Inoue, T. Postprandial Hyperglycemia as an Etiological Factor in Vascular Failure. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2009, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koska, J.; Schwartz, E.A.; Mullin, M.P.; Schwenke, D.C.; Reaven, P.D. Improvement of Postprandial Endothelial Function After a Single Dose of Exenatide in Individuals With Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Recent-Onset Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1028–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Tsai, M.-F.; Thorat, R.S.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, X.; Sandhu, A.K.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B.M. Endothelial Function and Postprandial Glucose Control in Response to Test-Meals Containing Herbs and Spices in Adults With Overweight/Obesity. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 811433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, E.; Bruno, R.S. Postprandial Hyperglycemia on Vascular Endothelial Function: Mechanisms and Consequences. Nutr Res 2012, 32, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kc, S.; Cárcamo, J.M.; Golde, D.W. Vitamin C Enters Mitochondria via Facilitative Glucose Transporter 1 (Glut1) and Confers Mitochondrial Protection against Oxidative Injury. FASEB J 2005, 19, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besse-Patin, A.; Estall, J.L. An Intimate Relationship between ROS and Insulin Signalling: Implications for Antioxidant Treatment of Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Cell Biol 2014, 2014, 519153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picklo, M.J.; Thyfault, J.P. Vitamin E and Vitamin C Do Not Reduce Insulin Sensitivity but Inhibit Mitochondrial Protein Expression in Exercising Obese Rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2015, 40, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Frampton, C.; Lunt, H. Metabolic Syndrome Is Associated with Increased Vitamin C Requirements in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrition Research 2025, 141, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleiner, J.; Schaller, G.; Mittermayer, F.; Bayerle-Eder, M.; Roden, M.; Wolzt, M. FFA-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction Can Be Corrected by Vitamin C. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 87, 2913–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashor, A.W.; Lara, J.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effect of Vitamin C on Endothelial Function in Health and Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Atherosclerosis 2014, 235, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami-Ardekani, M.; Shojaoddiny-Ardekani, A. Effect of Vitamin C on Blood Glucose, Serum Lipids & Serum Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Indian J Med Res 2007, 126, 471–474. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Huang, X.-J.; Chen, G.-X. Current Understanding of Glucose Transporter 4 Expression and Functional Mechanisms. World J Biol Chem 2020, 11, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albaik, M.; Sheikh Saleh, D.; Kauther, D.; Mohammed, H.; Alfarra, S.; Alghamdi, A.; Ghaboura, N.; Sindi, I.A. Bridging the Gap: Glucose Transporters, Alzheimer’s, and Future Therapeutic Prospects. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T.Y.; Otsuka, M.; Arakawa, N. Ascorbate Indirectly Stimulates Fatty Acid Utilization in Primary Cultured Guinea Pig Hepatocytes by Enhancing Carnitine Synthesis123. The Journal of Nutrition 1994, 124, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigler, N.; Saccà, L.; Sherwin, R.S. Synergistic Interactions of Physiologic Increments of Glucagon, Epinephrine, and Cortisol in the Dog: A MODEL FOR STRESS-INDUCED HYPERGLYCEMIA. J Clin Invest 1979, 63, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, R.A.; Matthews, D.E.; Bier, D.M.; Sherwin, R.S. Role of Counterregulatory Hormones in the Catabolic Response to Stress. J Clin Invest 1984, 74, 2238–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.J.; Golden, S.H. Cortisol Dysregulation: The Bidirectional Link between Stress, Depression, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2017, 1391, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamba, A.; Daimon, M.; Murakami, H.; Otaka, H.; Matsuki, K.; Sato, E.; Tanabe, J.; Takayasu, S.; Matsuhashi, Y.; Yanagimachi, M.; Terui, K.; Kageyama, K.; Tokuda, I.; Takahashi, I.; Nakaji, S. Association between Higher Serum Cortisol Levels and Decreased Insulin Secretion in a General Population. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0166077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, M.; Kawagoe, N.; Kameyama, C.; Kondou, Y.; Igarashi, M.; Ueshiba, H. Association of Serum Cortisol with Insulin Secretion and Plasma Aldosterone with Insulin Resistance in Untreated Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2025, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, R.; Kluwe, B.; Odei, J.B.; Echouffo Tcheugui, J.B.; Sims, M.; Kalyani, R.R.; Bertoni, A.G.; Golden, S.H.; Joseph, J.J. The Association of Morning Serum Cortisol with Glucose Metabolism and Diabetes: The Jackson Heart Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 103, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Vella, A. Glucose Metabolism in Cushing’s Syndrome. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2020, 27, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Auchus, R.J. Cushing Syndrome, Hypercortisolism, and Glucose Homeostasis: A Review. Diabetes 2025, 74, 2168–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-X.; Cummins, C.L. Fresh Insights into Glucocorticoid-Induced Diabetes Mellitus and New Therapeutic Directions. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, M.; Burén, J.; Ruge, T.; Myrnäs, T.; Eriksson, J.W. Glucocorticoids Down-Regulate Glucose Uptake Capacity and Insulin-Signaling Proteins in Omental But Not Subcutaneous Human Adipocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89, 2989–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamov, E.V.; Purnell, J.Q.; Fleseriu, M. Glucocorticoid Receptor Antagonism as a New “Remedy” for Insulin Resistance-Not There Yet! J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, e2447–e2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapela, S.P.; Simancas-Racines, D.; Montalvan, M.; Frias-Toral, E.; Simancas-Racines, A.; Muscogiuri, G.; Barrea, L.; Sarno, G.; Martínez, P.I.; Reberendo, M.J.; Llobera, N.D.; Stella, C.A. Signals for Muscular Protein Turnover and Insulin Resistance in Critically Ill Patients: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, H.; Lee, I.H.; Du, J.; Mitch, W.E. Endogenous Glucocorticoids and Impaired Insulin Signaling Are Both Required to Stimulate Muscle Wasting under Pathophysiological Conditions in Mice. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louard, R.J.; Bhushan, R.; Gelfand, R.A.; Barrett, E.J.; Sherwin, R.S. Glucocorticoids Antagonize Insulin’s Antiproteolytic Action on Skeletal Muscle in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994, 79, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, P.S.; Miles, J.M.; Gerich, J.E.; Haymond, M.W. Increased Proteolysis. An Effect of Increases in Plasma Cortisol within the Physiologic Range. J Clin Invest 1984, 73, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, Z.; Hu, J.; Du, J.; Mitch, W.E. Insulin Resistance Accelerates Muscle Protein Degradation: Activation of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway by Defects in Muscle Cell Signaling. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 4160–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akalestou, E.; Genser, L.; Rutter, G.A. Glucocorticoid Metabolism in Obesity and Following Weight Loss. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscaro, M.; Giacchetti, G.; Ronconi, V. Visceral Adipose Tissue: Emerging Role of Gluco- and Mineralocorticoid Hormones in the Setting of Cardiometabolic Alterations. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012, 1264, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, M.; Bredella, M.A.; Tsai, P.; Mendes, N.; Miller, K.K.; Klibanski, A. Lower Growth Hormone and Higher Cortisol Are Associated with Greater Visceral Adiposity, Intramyocellular Lipids, and Insulin Resistance in Overweight Girls. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2008, 295, E385–E392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould Bessi, N.; Touahria Miliani, Y.; Damou, R.; EL Mehdaoui, M.A.; Kemache, A.; Ait Abdelkader, B. Association between 8 a.m. Cortisol Levels and Insulin Resistance in Healthy Individuals from Algiers. Obesity Medicine 2025, 58, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.-X.; Xiao, H.-B.; Wang, S.-S.; Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Wang, W.; Dong, J. Investigation of the Relationship Between Chronic Stress and Insulin Resistance in a Chinese Population. J Epidemiol 2016, 26, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzarino, A.I.; Hamer, M.; Gaze, D.; Collinson, P.; Steptoe, A. The Association between Cortisol Response to Mental Stress and High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Plasma Concentration in Healthy Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 62, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vage, A.; Gormley, G.; Hamilton, P.K. The Effects of Controlled Acute Psychological Stress on Serum Cortisol and Plasma Metanephrine Concentrations in Healthy Subjects. Ann Clin Biochem 2025, 62, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, J.; Zhang, P.; Luo, X.; Chen, S.; Tian, B.; Tan, S.; Wang, Z.; Han, X.; Tian, L.; Li, C.-S.R.; Hong, L.E.; Tan, Y. Abnormal Cortisol Profile during Psychosocial Stress among Patients with Schizophrenia in a Chinese Population. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 18591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadi, A.; Andreadi, S.; Todaro, F.; Ippoliti, L.; Bellia, A.; Magrini, A.; Chrousos, G.P.; Lauro, D. Modified Cortisol Circadian Rhythm: The Hidden Toll of Night-Shift Work. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhefkova, N.; Sládek, M.; Sumová, A.; Dubsky, M. Circadian Dysfunction and Cardio-Metabolic Disorders in Humans. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, L.A.; Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S.M.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Bradfield, C.A.; Malecki, K.M.C. Circadian Disruption, Clock Genes, and Metabolic Health. J Clin Invest 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, J.L.; D’souza, A.M.; Teich, T.; Tsushima, R.; Riddell, M.C. Exogenous Glucocorticoids and a High-Fat Diet Cause Severe Hyperglycemia and Hyperinsulinemia and Limit Islet Glucose Responsiveness in Young Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3197–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pofi, R.; Othonos, N.; Marjot, T.; Bonaventura, I.; Barrett, A.; White, S.; Miller, H.; Potter, T.; Bailey, M.; Eastell, R.; Gossiel, F.; Woods, C.; Hazlehurst, J.M.; Hodson, L.; Tomlinson, J.W. Dose-Dependent and Tissue-Specific Adverse Effects of Exogenous Glucocorticoids: Insights for Optimizing Clinical Practice. J Endocrinol Invest 2025, 48, 2067–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Rodrigues, B. Glucocorticoids Produce Whole Body Insulin Resistance with Changes in Cardiac Metabolism. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2007, 292, E654–E667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sen, C.; Goswami, A. Effect of Vitamin C on Adrenal Suppression by Etomidate Induction in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Card Anaesth 2016, 19, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, P.J.; Harris, S.E.; Aldern, K.A. The Role of Ascorbic Acid in the Function of the Adrenal Cortex: Studies in Adrenocortical Cells in Culture. Endocrinology 1985, 117, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patani, A.; Balram, D.; Yadav, V.K.; Lian, K.-Y.; Patel, A.; Sahoo, D.K. Harnessing the Power of Nutritional Antioxidants against Adrenal Hormone Imbalance-Associated Oxidative Stress. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1271521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campión, J.; Milagro, F.I.; Fernández, D.; Martínez, J.A. Vitamin C Supplementation Influences Body Fat Mass and Steroidogenesis-Related Genes When Fed a High-Fat Diet. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2008, 78, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idahor, C.O.; Ogunfuwa, O.; Ogbonna, N.; Adigwe, A.; Ogbeide, O.A. Beyond Fluid Therapy: The Role of Vitamin C, Steroids, and Thiamine in Sepsis Management. Cureus 2025, 17, e84666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meščić Macan, A.; Gazivoda Kraljević, T.; Raić-Malić, S. Therapeutic Perspective of Vitamin C and Its Derivatives. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, S.R.; Yoshida-Hiroi, M.; Sotiriou, S.; Levine, M.; Hartwig, H.-G.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Eisenhofer, G. Impaired Adrenal Catecholamine System Function in Mice with Deficiency of the Ascorbic Acid Transporter (SVCT2). The FASEB Journal 2003, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Méndez, R.; Rivas-Arancibia, S. Vitamin C in Health and Disease: Its Role in the Metabolism of Cells and Redox State in the Brain. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.M.; Qu, Z.; Meredith, M.E. Mechanisms of Ascorbic Acid Stimulation of Norepinephrine Synthesis in Neuronal Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012, 426, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, B.; Schmitz, A.E.; Rodrigues, A.L.S.; Dafre, A.L.; Cunha, M.P. The Role of Vitamin C in Stress-Related Disorders. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2020, 85, 108459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senmaru, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Okada, H.; Asano, M.; Fukui, M.; Nakamura, N.; Obayashi, H.; Kondo, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Ishigami, A.; Hasegawa, G. Pancreatic Insulin Release in Vitamin C-Deficient Senescence Marker Protein-30/Gluconolactonase Knockout Mice. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2012, 50, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Zou, C.; Cai, Y.; He, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhu, H.; Qv, M.; Chao, Y.; Xu, C.; Tang, L.; Wu, X. Vitamin C Deficiency Induces Hypoglycemia and Cognitive Disorder through S-Nitrosylation-Mediated Activation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β. Redox Biol 2022, 56, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, T.O.; Yusuf, A.B.; Danjuma, J.K.; Usman, B.M.; Ishiaku, Y.M. Mechanistic Links between Vitamin Deficiencies and Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2021, 8, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, T.E. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Vitamin C: A Powerful Anti-Aging Combination. Orthomolecular Medicine News Service 2025, 21. Available online: https://orthomolecular.org/resources/omns/v21n66.shtml.

- Norton, L.; Shannon, C.; Gastaldelli, A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin: The Master Regulator of Glucose Metabolism. Metabolism 2022, 129, 155142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessari, P. Stepwise Discovery of Insulin Effects on Amino Acid and Protein Metabolism. Nutrients 2023, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.; Joy, N.V.; Carrillo Sepulveda, M.A. Biochemistry, Insulin Metabolic Effects. In StatPearlsStatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525983/.

- Bitoska, I.; Krstevska, B.; Milenkovic, T.; Subeska-Stratrova, S.; Petrovski, G.; Mishevska, S.J.; Ahmeti, I.; Todorova, B. Effects of Hormone Replacement Therapy on Insulin Resistance in Postmenopausal Diabetic Women. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2016, 4, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Members, M. New Meta-Analysis Shows That Hormone Therapy Can Significantly Reduce Insulin Resistance. Available online: https://menopause.org/press-releases/new-meta-analysis-shows-that-hormone-therapy-can-significantly-reduce-insulin-resistance (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Aroda, V.R.; Christophi, C.A.; Edelstein, S.L.; Perreault, L.; Kim, C.; Golden, S.H.; Horton, E.; Mather, K.J. Circulating Sex Hormone Binding Globulin Levels Are Modified with Intensive Lifestyle Intervention, but Their Changes Did Not Independently Predict Diabetes Risk in the Diabetes Prevention Program. BMJ Open Diab Res Care 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.N.; Nestler, J.E.; Strauss, J.F.; Wickham, E.P. Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012, 23, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, I.R.; McKinley, M.C.; Bell, P.M.; Hunter, S.J. Sex Hormone Binding Globulin and Insulin Resistance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013, 78, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Liang, W.; Xie, Q. Resistance to the Insulin and Elevated Level of Androgen: A Major Cause of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateguana, N.B.; Janes, A. The Contribution of Hyperinsulinemia to the Hyperandrogenism of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Journal of Metabolic Health 2019, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unluhizarci, K.; Karaca, Z.; Kelestimur, F. Role of Insulin and Insulin Resistance in Androgen Excess Disorders. World J Diabetes 2021, 12, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Eshmawy, M.M.; Hegazy, A.; El-Baiomy, A.A. Relationship Between IGF-1 and Cortisol/ DHEA-S Ratio in Adult Men With Diabetic Metabolic Syndrome Versus Non-Diabetic Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 2011, 1, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhong, Y.; Xue, Q.; Wu, M.; Deng, X.; O Santos, H.; Tan, S.C.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Jiao, P. Impact of Dehydroepianrosterone (DHEA) Supplementation on Serum Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1): A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Exp Gerontol 2020, 136, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, M.M.; Smit, R.A.J.; Trompet, S.; Heemst, D. van; Noordam, R. Thyroid Signaling, Insulin Resistance, and 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017, 102, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, D.A.; Ortiz, R.M. Thyroid Hormones and the Potential for Regulating Glucose Metabolism in Cardiomyocytes during Insulin Resistance and T2DM. Physiol Rep 2021, 9, e14858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, X.; Cui, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, G. Associations between Sensitivity to Thyroid Hormones and Insulin Resistance in Euthyroid Adults with Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, K.; Rawashdeh, O.; Olejniczak, I.; Pilorz, V.; Assis, L.V.M. de; Osorio-Mendoza, J.; Oster, H. Endocrine Regulation of Circadian Rhythms. npj Biol Timing Sleep 2025, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, N.A.; Yuen, F.; Butt, W.Z.; Liu, P.Y. Sleep and Circadian Regulation of Cortisol: A Short Review. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res 2021, 18, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauter, E.; Blackman, J.D.; Roland, D.; Spire, J.P.; Refetoff, S.; Polonsky, K.S. Modulation of Glucose Regulation and Insulin Secretion by Circadian Rhythmicity and Sleep. J Clin Invest 1991, 88, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Anwar, H.; Sohail, M.U.; Ali Shah, S.M.; Hussain, G.; Rasul, A.; Ijaz, M.U.; Nisar, J.; Munir, N.; Shahzad, A. The Association between Serum Cortisol, Thyroid Profile, Paraoxonase Activity, Arylesterase Activity and Anthropometric Parameters of Undergraduate Students under Examination Stress. Eur J Inflamm 2021, 19, 20587392211000884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrowski, K.; Kahaly, G.J. Stress and Thyroid Function—From Bench to Bedside. Endocr Rev 2025, 46, 709–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.R.; Prakash, P.; Keshari, J.R.; Kumari, R.; Prakash, V. Assessment of Serum Cortisol Levels in Hypothyroidism Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e50199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattu, V.K.; Chattu, S.K.; Burman, D.; Spence, D.W.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. The Interlinked Rising Epidemic of Insufficient Sleep and Diabetes Mellitus. Healthcare (Basel) 2019, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, Y.; Upender, R.P. Sleep Disturbance and Metabolic Dysfunction: The Roles of Adipokines. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.M.; Qu, Z.-C.; Nazarewicz, R.; Dikalov, S. Ascorbic Acid Efficiently Enhances Neuronal Synthesis of Norepinephrine from Dopamine. Brain Res Bull 2013, 90, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Dellanoce, C.; Vezzoli, A.; Mrakic-Sposta, S.; Malnati, M.; Beretta, A.; Accinni, R. Antioxidant Activity with Increased Endogenous Levels of Vitamin C, E and A Following Dietary Supplementation with a Combination of Glutathione and Resveratrol Precursors. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Lu, M.; Dudek, E.; Reddan, J.; Taylor, A. Vitamin C and Vitamin E Restore the Resistance of GSH-Depleted Lens Cells to H2O2. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2003, 34, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tram, N.K.; McLean, R.M.; Swindle-Reilly, K.E. Glutathione Improves the Antioxidant Activity of Vitamin C in Human Lens and Retinal Epithelial Cells: Implications for Vitreous Substitutes. Current Eye Research 2021, 46, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorsan, H.; Simbar, M.; Tehrani, F.R.; Fathi, F.; Mosaffa, N.; Riazi, H.; Akradi, L.; Nasseri, S.; Bazrafkan, S. The Effectiveness of Antioxidant Therapy (Vitamin C) in an Experimentally Induced Mouse Model of Ovarian Endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2022, 18, 17455057221096218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; He, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Liu, L.; Sun, S.; Ma, S.; Rodriguez Esteban, C.; Fu, X.; Zhao, G.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; Zhang, W.; Qu, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, G.-H. Vitamin C Conveys Geroprotection on Primate Ovaries. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1723–1740.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatone, C.; Di Emidio, G.; Battaglia, R.; Di Pietro, C. Building a Human Ovarian Antioxidant ceRNA Network “OvAnOx”: A Bioinformatic Perspective for Research on Redox-Related Ovarian Functions and Dysfunctions. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.-M.; Stout, A.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Leppert, P.C. Ascorbic Acid Status in Postmenopausal Women with Hormone Replacement Therapy. Maturitas 2002, 41, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin C. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Compounded Bioidentical Menopausal Hormone Therapy. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-consensus/articles/2023/11/compounded-bioidentical-menopausal-hormone-therapy (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Greendale, G.A.; Sternfeld, B.; Huang, M.; Han, W.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C.; Ruppert, K.; Cauley, J.A.; Finkelstein, J.S.; Jiang, S.-F.; Karlamangla, A.S. Changes in Body Composition and Weight during the Menopause Transition. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBane, S.E.; Borgelt, L.M.; Barnes, K.N.; Westberg, S.M.; Lodise, N.M.; Stassinos, M. Use of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy in Menopausal Women: An Opinion Statement of the Women’s Health Practice and Research Network of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E.; Division, H. and M.; Policy, B. on H.S.; Therapy, C. on the C.U. of T.P. with C.B.H.R.; Jackson, L.M.; Parker, R.M.; Mattison, D.R. The Safety and Effectiveness of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy. In The Clinical Utility of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy: A Review of Safety, Effectiveness, and UseNational Academies Press (US), 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562865/.

- Patel, P.; Patil, S.; Kaur, N. Estrogen and Metabolism: Navigating Hormonal Transitions from Perimenopause to Postmenopause. J Midlife Health 2025, 16, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.D.; Daniels, K.R.; Barner, J.C.; Carson, J.J.; Frei, C.R. Effectiveness of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy: An Observational Cohort Study. BMC Womens Health 2011, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, R.; Shuster, L.; Smith, R.; Vincent, A.; Jatoi, A. Counseling Postmenopausal Women about Bioidentical Hormones: Ten Discussion Points for Practicing Physicians. J Am Board Fam Med 2011, 24, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K.; Neuenschwander, P.F.; Kurdowska, A.K. The Effects of Compounded Bioidentical Transdermal Hormone Therapy on Hemostatic, Inflammatory, Immune Factors; Cardiovascular Biomarkers; Quality-of-Life Measures; and Health Outcomes in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women. Int J Pharm Compd 2013, 17, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- admin How Bioidentical HRT Impacts Diabetes Risk. Available online: https://womenshormonenetwork.org/2024/02/22/how-bioidentical-hrt-impacts-diabetes-risk/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cooper, B.C.; Burger, N.Z.; Toth, M.J.; Cushman, M.; Sites, C.K. Insulin Resistance with Hormone Replacement Therapy: Associations with Markers of Inflammation and Adiposity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007, 196, 123.e1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, S.R.; Allolio, B.; Arlt, W.; Barthel, A.; Don-Wauchope, A.; Hammer, G.D.; Husebye, E.S.; Merke, D.P.; Murad, M.H.; Stratakis, C.A.; Torpy, D.J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, 364–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.H. Clinical and Technical Aspects in Free Cortisol Measurement. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2022, 37, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, T.; Elahi, A.; Wijns, W.; Shahzad, A. Cortisol Detection Methods for Stress Monitoring in Connected Health. Health Sciences Review 2023, 6, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donin, A.S.; Dent, J.E.; Nightingale, C.M.; Sattar, N.; Owen, C.G.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Perkin, M.R.; Stephen, A.M.; Jebb, S.A.; Cook, D.G.; Whincup, P.H. Fruit, Vegetable and Vitamin C Intakes and Plasma Vitamin C: Cross-Sectional Associations with Insulin Resistance and Glycaemia in 9-10 Year-Old Children. Diabet Med 2016, 33, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VA.Gov | Veterans Affairs. Available online: https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/tools/hormone-replacement-therapy.asp (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Weinstock, D. The Menopause Society: Hormone Therapy Statement. Available online: https://www.obgproject.com/2022/11/21/north-american-menopause-society-releases-2017-hormone-therapy-statement/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Committee on the Clinical Utility of Treating Patients with Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine The Clinical Utility of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy: A Review of Safety, Effectiveness, and Use; National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2020. https://doi.org/10.17226/25791. Available online: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25791.

- Kleis-Olsen, A.S.; Farlov, J.E.; Petersen, E.A.; Schmücker, M.; Flensted-Jensen, M.; Blom, I.; Ingersen, A.; Hansen, M.; Helge, J.W.; Dela, F.; Larsen, S. Metabolic Flexibility in Postmenopausal Women: Hormone Replacement Therapy Is Associated with Higher Mitochondrial Content, Respiratory Capacity, and Lower Total Fat Mass. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2024, 240, e14117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unlu, Y.; Vinales, K.L.; Hollstein, T.; Chang, D.; Cabeza de Baca, T.; Walter, M.; Krakoff, J.; Piaggi, P. The Association between Gut Hormones and Diet-Induced Metabolic Flexibility in Metabolically Healthy Adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2023, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).