1. Introduction

Radiated noise from gearbox housings significantly affects the noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH) performance of automotive drivetrains. Walls that vibrate, such as housing panels, often dominate noise radiation, as housing flexural modes are readily excited by gear-mesh forces transmitted via bearings and shafts. Efforts to reduce gearbox housing noise have largely focused on structural modifications such as stiffeners or topology optimization. For instance, Ümütlü et al. compared basic, cross, and cellular housing designs with internal stiffeners (while keeping mass constant) and demonstrated reductions in vibration and noise via finite-element analysis. Similarly, studies combining modal–acoustic approaches with topology optimization have targeted low-noise gearbox housings, validated by experiments [

1].

Despite extensive research on NVH-reduction via design, the effect of manufacturing tolerances in wall thickness—a source of geometric variability—has not been systematically examined. Driot et al. used statistical methods (Taguchi and Monte Carlo) to evaluate how manufacturing errors such as misalignment and tooth-profile deviations affect critical rotational speed variability, but wall thickness was not considered [

2]. Werner et al. investigated real-world housing deviations using 3D scanning to introduce manufacturing deviations into modal models, including wall-thickness deviations; however, their focus lay on validating models, not on quantifying acoustic effects [

3]. More broadly, reviews of NVH optimization and production tolerances in mechanical systems suggest that geometric variability can impact dynamic behavior [

4], yet none specifically address wall thickness tolerance effects in gearbox NVH.

Therefore, while structural modifications and general geometric tolerances have received attention, no study to date has quantified the influence of wall thickness variability (±10%) on gearbox housing radiated noise. This gap motivates the present numerical investigation using modal scaling and Monte Carlo simulation to evaluate this specific tolerance effect.

Our specific objectives are to: (i) quantify dB-level differences between tolerance-limit geometries. (ii) assess robustness to structural damping. (iii) estimate production-relevant spread using Monte Carlo analysis.2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies require that ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis was based on the mechanical relationship between wall thickness and structural stiffness. For thin plates and shells, the bending stiffness D is proportional to

, where E is Young’s modulus and h is wall thickness [

5]. Consequently, modal frequencies fn scale approximately linearly with h. A ±10% change in thickness was therefore represented by proportional scaling of all modal frequencies in the model.

A simplified multi-mode structural–acoustic model was developed to represent the dominant vibration modes in the 800–1300 Hz range of the gearbox housing. Each mode was modelled as a single-degree-of-freedom oscillator with its own natural frequency and structural damping ratio. Wall thickness variation was incorporated by applying the scaling factor to all modal frequencies simultaneously. Three deterministic cases were evaluated:

All cases used identical material properties and damping (ζ=1.5%). The excitation was a unit-amplitude harmonic force, and the radiated sound power was estimated from the surface velocity magnitude using structural–acoustic coupling relationships [

6,

7].

To evaluate production-relevant variability, a Monte Carlo simulation with N=500N samples was performed. Wall thickness values were drawn from a truncated normal distribution with a standard deviation of 3%, constrained to the ±10% tolerance band. The analysis focused on the 980–1020 Hz range near the central resonance.

Manufacturing tolerance values for comparison were taken from ISO 2768 and ISO 286 [

8,

9], as well as industry data for sheet-metal thickness variability [

10,

11]. Typical industrial practice for thin-gauge materials (<3 mm) specifies tolerances of ±1% to ±10%, or ±0.05 mm to ±0.20 mm depending on thickness and grade. These tolerance ranges informed the chosen ±10% variation for the simulations.

Calculation of decibel levels: The surface velocity results obtained from the model were converted to a decibel scale using

where v is the calculated RMS surface velocity and

is the chosen reference velocity. In this study, the reference was taken as the RMS velocity at the main resonance peak of the nominal wall thickness case (h=

). This normalization ensured that the values presented in the figures represent the relative differences between wall thickness variants on a dB scale.

For the Monte Carlo analysis, the average level within the 980–1020 Hz frequency band was calculated for each sample, and the difference relative to the nominal case was expressed in decibels.

The radiated noise level is estimated from the structural surface velocity amplitude using structural–acoustic coupling relationships. A constant radiation efficiency (σ=1) is assumed for the frequency range of interest, corresponding to a baffled flat panel approximation. This approach yields proportional changes in radiated sound power level from proportional changes in RMS surface velocity. Modal contributions from each dominant mode are calculated separately and combined using linear superposition of complex amplitudes.

3. Results

3.1. Frequency Response Changes

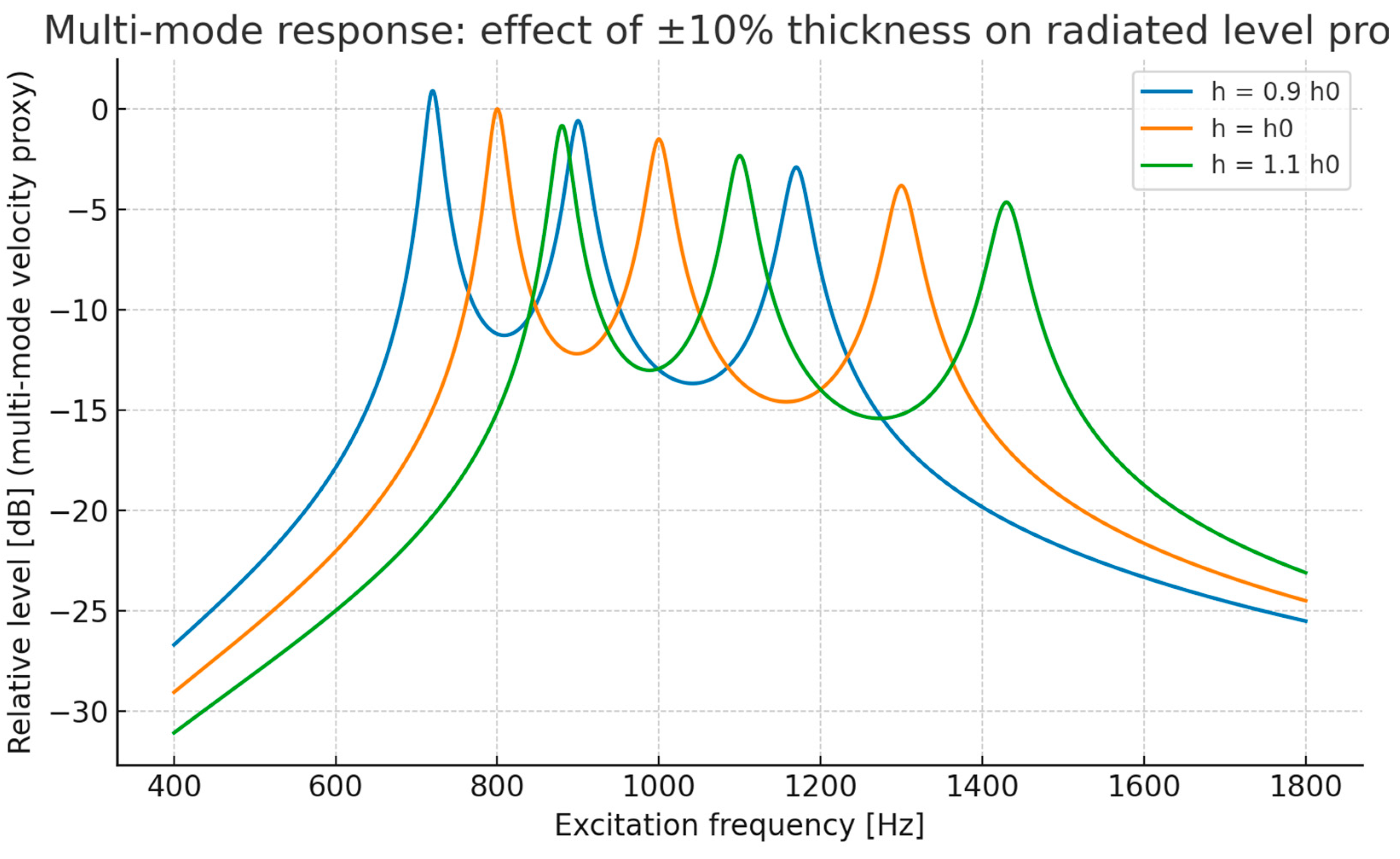

The simulated frequency responses for the three wall thickness cases are shown in

Figure 1. A ±10% change in wall thickness caused a proportional shift in modal frequencies and noticeable changes in peak amplitudes within the resonance region. In the 950–1050 Hz band, the maximum level difference between the extreme cases reached 20.9 dB, while the average difference across the band was 3.34 dB.

3.2. Damping Sensitivity

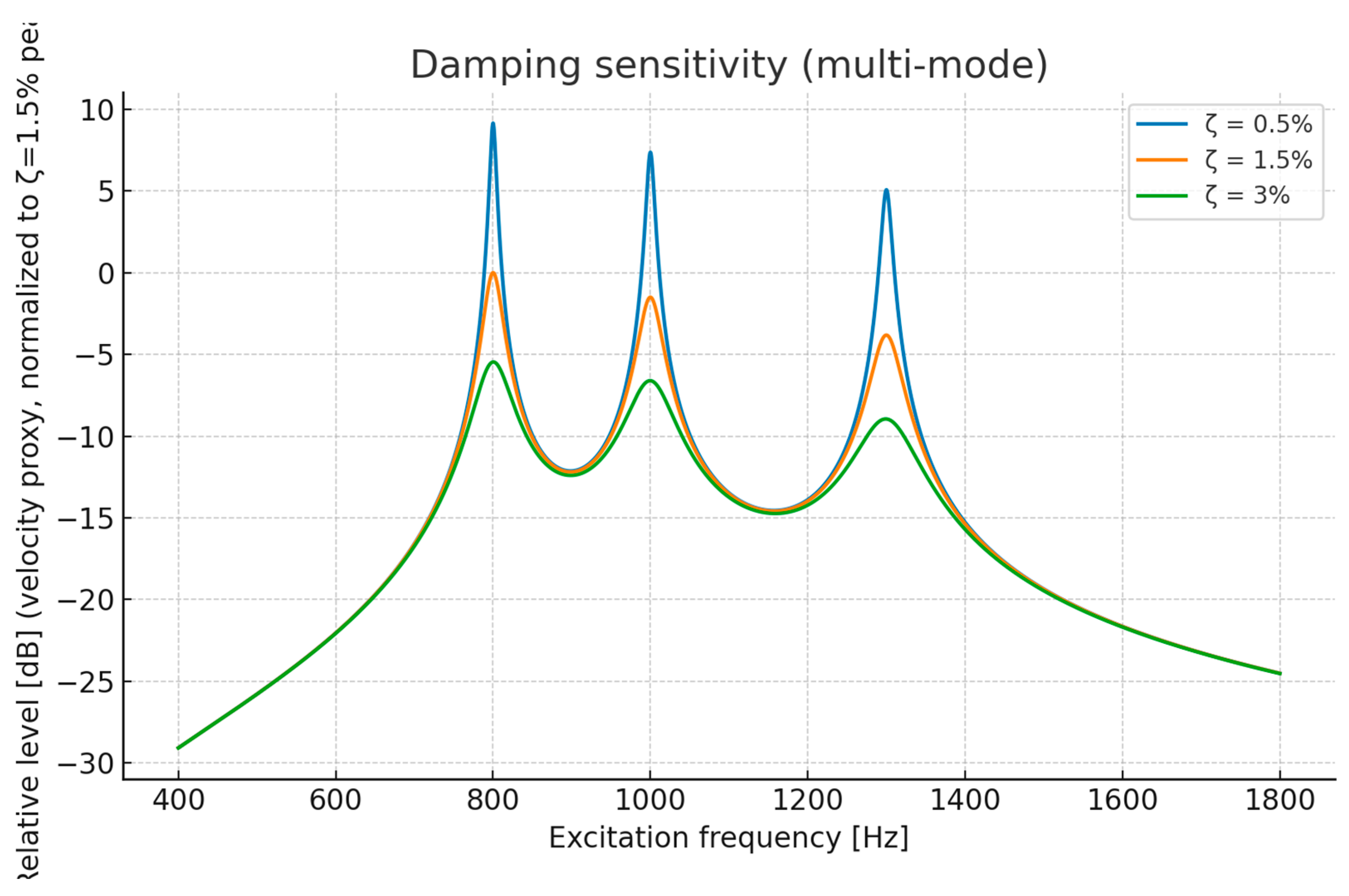

Figure 2 presents the damping sensitivity for the nominal wall thickness case at ζ=0.5%, 1.5%, and 3.0%. Increasing damping reduced absolute peak amplitudes but did not eliminate the relative differences caused by wall thickness variation. Even at the highest damping level, the resonance structure and modal spacing remained evident.

3.3. Statistical Spread Due to Tolerances

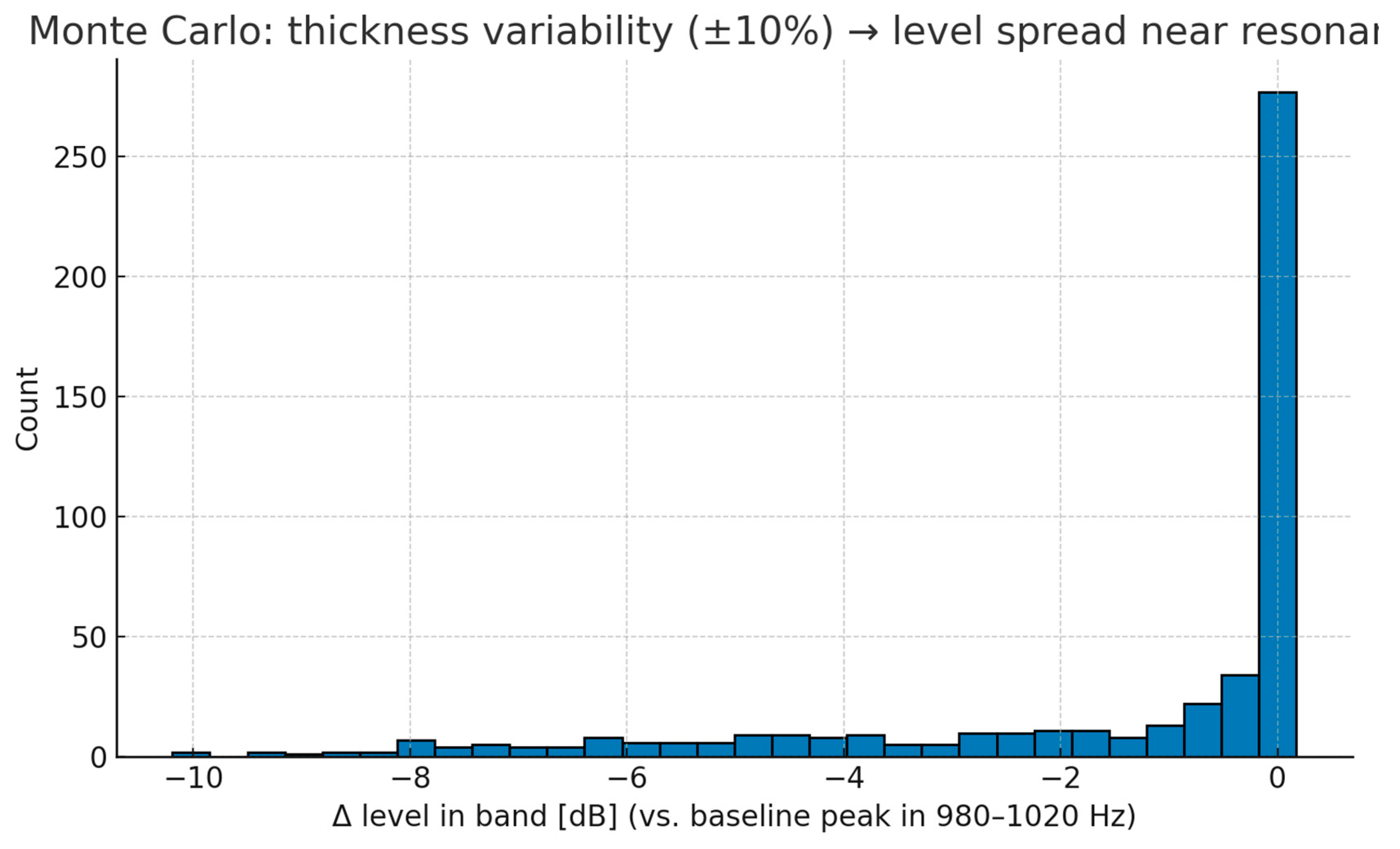

Monte Carlo analysis of 500 simulated thickness values within the ±10% tolerance range produced the distribution shown in

Figure 3. The mean change in the 980–1020 Hz band was 0.54 dB, with a standard deviation of 1.15 dB. The 5th–95th percentile range extended from −1.30 dB to +2.54 dB. While the average effect was modest, certain combinations produced differences exceeding 2 dB, which is large enough to contribute to unit-to-unit NVH variation in production.

4. Discussion

The numerical results confirm that wall thickness tolerances within standard manufacturing limits can significantly influence the radiated noise of gearbox housing, particularly in frequency ranges close to structural resonances. A ±10% thickness change was shown to proportionally shift modal frequencies, which in turn altered the dynamic response and radiated noise levels. The observed differences—up to 20.9 dB between extreme cases—are large enough to affect perceived NVH quality.

Compared with previous NVH studies on gearbox housings [

6,

7,

12], this work isolates thickness variability as a single parameter and quantifies its impact using deterministic and statistical simulations. Earlier research addressed geometry, damping treatments, and material modifications, but few have systematically evaluated the effect of wall thickness tolerances despite their occurrence in production [

10,

11].

The Monte Carlo analysis indicates that the average effect of thickness variability is modest (≈0.54 dB in the main resonance band), but extreme cases can reach 2.54 dB. Such differences, although numerically small, are perceptible in critical NVH evaluations and may contribute to unit-to-unit variation observed in end-of-line testing. This finding aligns with field observations where seemingly identical gearboxes exhibit slight acoustic differences despite meeting all dimensional specifications.

Damping sensitivity results suggest that increasing structural damping reduces overall amplitudes but does not fully mitigate the influence of wall thickness variation. Consequently, simply adding damping may not be a sufficient countermeasure. Instead, incorporating thickness variation into early-stage design sensitivity analyses can enable targeted strategies such as modal detuning—shifting resonances away from dominant excitation orders—or localized stiffening in acoustically sensitive regions.

Overall, the findings underscore the need to integrate realistic manufacturing variability into NVH-focused design workflows. This approach can help manufacturers reduce production spread, improve acoustic robustness, and avoid costly late-stage design modifications.

5. Conclusions

This study quantified the influence of wall thickness tolerances on the radiated noise of gearbox housings using a simplified multi-mode structural–acoustic model and Monte Carlo simulations. The main conclusions are:

Modal frequency sensitivity – A ±10% change in wall thickness produced proportional modal frequency shifts, resulting in measurable differences in radiated noise when excitation frequencies coincided with resonance.

Magnitude of variation – The maximum difference in the 950–1050 Hz resonance band reached 20.9 dB between extreme cases, with an average change of 3.34 dB.

Statistical spread – Monte Carlo analysis showed mean changes of 0.54 dB and extremes up to 2.54 dB within the tolerance range, indicating that manufacturing variability can contribute to unit-to-unit NVH differences.

Damping effects – Higher structural damping reduced peak amplitudes but did not eliminate the impact of wall thickness variation, confirming that damping alone is not a complete countermeasure.

The study addressed all aspects set out in the Introduction. The analyses quantified the decibel-level differences caused by wall thickness variation, examined their persistence under varying structural damping, and characterised the statistical spread expected under production tolerances through Monte Carlo simulation.

Engineering implication: Wall thickness tolerances, even when compliant with industry standards, can have a non-negligible effect on gearbox NVH performance. Including realistic tolerance variations in early-stage design and sensitivity analyses can improve acoustic robustness, reduce production spread, and minimize the risk of late-stage NVH issues.

References

- Ümütlü, R. C., Hizarcı, B., Dalbicer, Ç., Öztürk, H., & Kiral, Z. (2019). Effect of inner stiffeners on vibration and noise levels of gearbox housing without changing the mass. Journal of Measurements in Engineering, 7(2), 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Driot, N., Rigaud, E., & Perret Liaudet, J. (2007). Variability of critical rotational speeds of gearbox by misalignment and manufacturing errors [arXiv preprint]. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0701064.

- Werner, D. (2020). Validation of multibody NVH gearbox calculations with 3D scan-derived manufacturing deviations. In Proceedings of ISMA2020 and USD2020. Leuven, Belgium.

- Werner, D., Scurria, L., Di Lorenzo, E., Graf, B., Neher, J., & Wender, B. (2020). Validation of multibody NVH gearbox calculations with order based modal analysis and measurement of operational bearing forces. In Proceedings of ISMA 2020: International Conference on Noise and Vibration Engineering / USD 2020 (Leuven, Belgium).

- Rao, S. S. (2017). Mechanical vibrations (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Lee, J., & Singh, R. (2009). Prediction of gearbox radiated noise using coupled structural–acoustic finite element analysis. Noise Control Engineering Journal, 57(4), 350–365. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H., & Peng, Z. (2019). Gearbox housing structural modification for vibration and noise reduction. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 133, 106248. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. (2010). ISO 286-1: Geometrical product specifications (GPS) — ISO code system for tolerances on linear sizes — Part 1: Basis of tolerances, deviations and fits. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO. https://www.iso.org/standard/45975.html.

- International Organization for Standardization. (1989). ISO 2768-1: General tolerances — Part 1: Tolerances for linear and angular dimensions without individual tolerance indications. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO. https://www.iso.org/standard/7451.html.

- Tripar Inc. (2024). Sheet metal thickness guide [White paper]. Montreal, Canada: Tripar Inc. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://www.triparinc.com/sheet-metal-thickness-guide/.

- Vandf Engineering. (2024). Sheet metal thickness tolerances [Technical data]. Portsmouth, UK: Vandf Engineering. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://www.vandf.co.uk/design-data/sheet-metal-thickness-tolerances/.

- Kim, S., Lee, Y., & Kim, M. (2016). Structural optimization for NVH improvement of an automotive transmission housing. Applied Acoustics, 105, 76–83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).