1. Introduction

The plausibility that vaccines cause autism requires an explanation why 30 of 31 vaccinated children don’t have autism. That explanation is susceptibility. Toxicity is as much a function of susceptibility as it is exposure. Massive media campaigns that downplay the risk of aluminium toxicity, especially in vaccines, have obviated the perception of a need to identify risk factors. But if aluminium is causal, then identifying children at risk before injecting them with aluminium containing vaccines might mitigate the epidemic without compromising public vaccination programs.

The toxic potential of aluminium is indisputable. Aluminium has no biological function in plants, insects, or animals. Its ability to alter “biological water dynamics” disrupts many biological processes [

1]. Aluminium particles in vaccines might be construed as innocuous because they are poorly soluble [

2]. However, solvated aluminium cations affect biological structures and processes in micro-molar concentrations by forming complexes with critical oxygen-donor ligands [

3]. Aluminium competes with endobiotic cations such as magnesium, calcium, and iron [

4]. Target ligands include phosphate, citrate, transferrin [

5], calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) [

6], and the intracellular calcium transport protein, calmodulin [

7]. Modern studies show the nexus of acute aluminium toxicity to be impaired gut absorption and renal wasting of phosphate [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Although aluminium is ubiquitous in the environment, recognized toxicity is fairly uncommon. Nearly all children in the United States are exposed to aluminium in vaccines. Yet, 30:31 children don’t have autism [

12]. This might be used to dismiss that aluminium causes autism. But assuming aluminium to be causal, the explanation can only be susceptibility due to failed defenses.

Defenses include intact epithelial barriers, limited absorption by the skin and gut, and expedient excretion. Aluminium exposures such as during hemodialysis or by injection in vaccines circumvent protective physical barriers making aluminium 100% bioavailable [

13]. The final defense is expedient excretion. Aluminium excretion depends upon stable phosphate homeostasis, normal PTH levels, and abundant citrate in the glomerular filtrate.

This review investigates the role of PTH in aluminium toxicity and the notion that the risk is not limited to CKD. At the outset, this requires clarifying the confusing dichotomy that PTH is a factor in aluminium toxicity, yet aluminium reduces PTH. Fortuitously, the review also revealed evidence for a male gender bias and susceptibility.

Caution is indicated if disorders of phosphate homeostasis impair aluminium excretion. The risk of the remediation determines the standard of evidence [

14]. Thus, given the gravity of autism and the risk-free preventive measures, the evidence presented indicates judicious use and correcting such conditions before elective exposures to aluminium.

2. Materials and Methods

Purpose. At the outset, a systematic review was intended to reconcile why hPTH is a problem if aluminium decreases PTH. A narrative review seemed appropriate to on proceeding to find supporting evidence that hPTH is the susceptibility factor and to explain the gender ratio in autism.

Scope. The review was limited to assessing the effect of disordered phosphate homeostasis on aluminium excretion. An extensive assessment of aluminium distribution to the tissues driven by hPTH exceeds the limitations of this paper. Example disorders of phosphate homeostasis included CKD, primary hPTH, X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), hypophosphatemia of leprosy (HOL), and vitamin D insufficiency. The entire differential diagnosis is relevant, but exceeds the limitations of this paper.

Search Methods. Many search terms were used such as “aluminium parathyroid hormone”, “hypophosphatemia aluminium toxicity”. Google Scholar was the primary search engine. Google AI was useful for quickly identifying primary sources. Forward and backward citation tracking was used.

Criteria for Selection of Papers. A conscious effort was made to avoid selection bias. Papers were selected for relevance, peer review, and propensity to influence clinical practice and health policy. Papers included experimental reports, meta-analyses, case reports and series, reviews, and evidence-based hypotheses. Countervailing papers refuting hypotheses were sought and included. Queries with no results were noted. Problematic papers using fallacies were included for discussion. Anonymous articles, speculative hypotheses without testability, and superfluous secondary sources were omitted.

Formulation of Conclusions. Conclusions were formulated from the standpoint that empirical and rational approaches both have value when taken appropriately. Hypotheses are backed by evidence and are testable.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review of the Relationship Between Aluminium and Parathyroid Hormone

Alfrey, et al. (1976): There was significantly higher aluminium content in the bone and brain of CKD patients suffering encephalopathy compared with controls [

15].

Significance: This controlled observation implicated aluminium as a necessary cause of emerging encephalopathy among patients receiving hemodialysis. Encephalopathy among non-dialyzed patients proved that low glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was a contributing but not necessary cause. Non-dialyzed patients generally have higher GFRs. Yet, although the aluminium content in tissues was not as high in non-dialyzed patients, it was present in cause sufficient concentrations that were significantly higher than controls. An unknown factor had to be causing aluminium retention in some uremic patients but not others.

Mayor, et al. (1977): The tissue distribution of aluminium in dialysis patients with fatal encephalopathy correlated with the distribution of aluminium in rats fed aluminium after exogenous PTH administration. PTH and tissue aluminium concentrations were highly correlated in deceased dialysis patients [

16].

Significance: PTH was identified as a necessary contributor to aluminium retention. Oral aluminium in the presence of hPTH is sufficient to cause aluminium toxicity without kidney disease.

Mayor, et al. (1978): High concentrations of aluminium were found in serum, whole blood, and tissues of patients with renal insufficiency. Evidence showed that aluminium is neurotoxic among dialysis patients and suggested the sources can be both oral and parenteral aluminium.

Significance: The effect of hPTH may have explained why some dialysis patients exposed to high parenteral aluminium concentrations were developing encephalopathy but others did not [

17].

Mayor, et al. (1980): A controlled experiment using rats with healthy kidneys confirmed a role for hPTH in aluminium toxicity. They fed aluminium to control rats and test rats after administering exogenous PTH. Control rats with normal PTH and fed aluminium did not accumulate any aluminium in brain or body tissues. Test rats fed aluminium after exogenous PTH accumulated significantly more aluminium than controls. Retained aluminium persisted in brain tissues well after oral aluminium was discontinued and until the exogenous PTH was finally withdrawn after ten days [

18].

Significance: The Mayor experiment was monumental. The experimental design didn’t replicate uremia and secondary hPTH. It replicated primary hPTH. Thus, kidney disease is not a necessary cause for aluminium retention; toxicity can occur in any disorder causing hPTH. Aluminium will accumulate and reside in the brain and body tissues as long as PTH remains high, and even after dosages of aluminium are discontinued. Brain aluminium egress did not require a chelating agent. Residual brain aluminium may dissipate when PTH returns to normal, but not before causing significant injury and creating a histological mystery how it happened. Finally, aluminium absorption, distribution, and excretion are under hormonal influence.

Alfrey, et al. (1980): Aluminium tissue concentration was measured in 123 cadavers. The cadavers included a control group, a group of non-dialyzed uremic patients who died of something else, and a group of dialyzed patients who died of renal encephalopathy. The control tissues had low aluminium concentrations. Aluminium concentrations were increased in the bone and liver of most uremic non-dialyzed patients, and increased in all tissues of every dialysis patient who died of renal encephalopathy.

Significance: Encephalopathy may occur when rapid aluminium loading exceeds the rate at which bone sequesters aluminium, and the surplus accumulates in the liver and brain [

19]. Unbeknownst to them, the rate of aluminium loading may have exceeded phosphate-regulating endopeptidase, X-linked (PHEX) enzyme expression - to be discussed later.

Gournot-Wittmer, et al. (1981): Bone aluminium content and distribution were compared between two groups of uremic patients. One group had biopsy-proven osteomalacia with negligible bone resorption. The other group was selected for osteitis fibrosa without mineralization defects. They concluded that aluminium may induce vitamin D-resistant osteomalacia only in the absence of severe secondary hPTH. PTH may be involved in aluminium-induced bone mineralization defects [

20].

Significance: Hormonal influence on aluminium distribution and excretion was well established by this time.

Mayor, et al. (1981): Varying aluminium in the potable water supply could account for sporadic local outbreaks of dialysis encephalopathy. On review of prior papers, they wrote that aluminium intoxication may be a function of “several disease processes converging to a common clinical presentation.” One of the disease processes mentioned was phosphate depletion [

21].

Significance: The paper indicated an emerging awareness that preexisting hypophosphatemia is a risk factor. They cited a seminal letter from Pierides, et al. (1976) published in The Lancet that implicated preexisting hypophosphatemia as a risk for aluminium intoxication [

22].

Mayor et al. (1983): The authors wrote explicitly that “considerable evidence argues against the concept that tissue aluminium accumulation occurs as a simple consequence of renal failure.”

Significance: The specific mechanisms of toxicity were not completely understood. However, they recognized that other factors besides impaired renal function contribute to aluminium toxicity in CKD [

23].

Burnatowska-Hledin, et al. (1983): Smaller exposures to aluminium than what occur during CKD treatment such as in the diet and medications are a cause for concern. Impaired renal function is not necessary for aluminium retention and toxicity.

Significance: They issued a prescient warning about the likelihood that toxicity can occur in populations other than those with renal disease [

24]. They probably resolved the autism epidemic before it ever happened. This full text of this paper cannot not be located. But the abstract withstands as evidence that the warning was issued.

Cannatta, et al. (1983): They followed 25 patients on a dialysis unit accidentally exposed to aluminium in the dialysate. Upon discovery, the average plasma aluminium concentration was increased, calcium was increased, and PTH was decreased. Two months later, average plasma aluminium and calcium returned to baseline, and PTH increased back to normal. This gave rise to a hypothesis that increased plasma calcium inhibits PTH excretion during aluminium intoxication event [

25].

Significance: It’s true that hypercalcemia inhibits PTH secretion. But it would also be proven later that aluminium stimulates CaSR which down-regulates PTH secretion inappropriately [

26], regardless of how low plasma calcium concentration may be. Their finding indicated awareness that aluminium decreases PTH only after the injurious toxic effects have commenced.

Morrissey, et al. (1983): Application of aluminium to bovine chief cells directly inhibited parathyroid secretion. The investigators didn’t know how this happens [

26].

Significance: It was clearly evident that aluminium inhibits PTH secretion inappropriately during states of hypophosphatemia.

3.2. Reconciling the Aluminium-PTH Dichotomy

The papers referenced above tell us the following: (1) Aluminium toxicity ensues before it reaches a sufficient concentration to inhibit PTH secretion. (2) Aluminium decreasing PTH is not encouraging. In fact, it may be an ominous sign of increasing toxicity. Although aluminium inhibits PTH secretion, it does so inappropriately. (3) Aluminium toxicity is primarily a phosphate wasting disease. (4) Hypophosphatemia prevails throughout the event, even after aluminium impairs PTH release.

Burnatowska-Hledin, et al. (1985) reconciled the PTH-aluminium dichotomy. Plasma aluminium inhibits phosphate reabsorption by the kidneys regardless of PTH, plasma pH, and cyclic AMP influence, but more likely due to pre-existing phosphate concentration [

10]. The investigators did not have as much information available on phosphate homeostasis as we have today. But they did know that aluminium was inhibiting PTH secretion inappropriately during a phosphate wasting event. Aluminium uncouples physiological parathyroid feedback control on plasma phosphate and calcium concentration. Any hope of maintaining calcium by way of higher PTH diminishes when aluminium inhibits PTH secretion. Aluminium reducing PTH secretion, a consequence of a deepening state of toxicity, could result in hypocalcemic seizures.

The early pioneers didn’t know about fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) and PHEX enzyme. The old school taught that PTH was directly responsible for regulating phosphate excretion [

27]. They could not have known before 2000 that FGF23 exists [

28], before 2004 that FGF-23 is the primary regulating hormone for phosphate excretion [

29], and before 1995 that PHEX enzyme inhibits phosphate over-excretion [

30]. But they knew enough to avoid using aluminium.

Ultimately, the discovery of CaSR in 1993 [

31] and subsequent studies on the effect of aluminium on CaSR confirmed how aluminium decreases PTH. Aluminium is a weak agonist for CaSR. Aluminium stimulates CaSR as if it was calcium, which inhibits PTH secretion. PTH suppression by aluminium is dosage dependent. It suppressed PTH secretion at a higher concentration in chief cell cultures than what is minimally sufficient to achieve toxicity [

6]. Aluminium also decreased PTH synthesis in rats [

32], but perhaps not as significantly as it stimulates CaSR to inhibit PTH secretion inappropriately.

3.3. Aluminium Toxicity and Phosphate Wasting

3.3.1. Aluminium Toxicity Is Primarily a Phosphate Wasting Event

Many authors recognize that phosphate binding with aluminium in the gut can cause hypophosphatemia due to limited absorption. But few papers cover hypophosphatemia due to renal wasting after aluminium injection. A couple of papers reported that after infusion alone, aluminium reduces phosphate concentration [

8,

10]. Aluminium might inhibit phosphate conservation by way of renal tubular reabsorption due to inadequate phosphate required for oxidative phosphorylation that, in-turn, powers reabsorption [

8].

Oral aluminium reduces plasma phosphate by forming insoluble complexes with phosphate in the gut that the gut can’t absorb. Conversely, plasma aluminium is likely to be excreted in similar fashion by forming insoluble complexes with phosphate in the renal tubules that the tubules cannot reabsorb.

Despite strident proclamations of aluminium safety, there were no published papers found that entertain the influence that injected aluminium has on renal phosphate handling during pre-existing states of hypophosphatemia. But from what we can glean from existing papers, efficient aluminium excretion requires an ample supply of phosphate whether hypophosphatemia is preexisting or made worse by aluminium infusion (to be discussed in more detail later).

Hypophosphatemia as a susceptibility factor in autism would necessarily be pre-existing. That, coupled with decreased phosphate absorption after normal dietary aluminium exposures and increased phosphate wasting by the kidneys enhances susceptibility following inter-muscular or intravenous aluminium administration.

3.3.2. Over-Treatment of Hyperphosphatemia in CKD

Hypophosphatemia has been known as the central feature of aluminium toxicity for a century [

33]. Considering the severity of hyperphosphatemia in CKD patients, the idea that over-treatment with oral aluminium is possible demonstrates the power of ingested aluminium to cause hypophosphatemia.

Only a few papers reported hypophosphatemia in uremic patients due to over-treatment. Lichtman, et.al. (1969) reported on a case of hypophosphatemia after oral aluminium gel ingestion in a uremic patient [

34]. King, et al. (1981) recognized that over-treatment in CKD may cause hypophosphatemia [

35]. Andreoli, et al. (1984) found in a case series that non-dialyzed uremic infants are especially susceptible to toxicity after oral administration [

36]. The revised practice of avoiding aluminium while treating CKD during the early 1980s may have obviated the need for further research on over-treatment of hyperphosphatemia in CKD.

3.3.3. Phosphate Loss in Healthy Populations

The literature is replete with papers about aluminium-induced hypophosphatemia in healthy people after oral exposure. For example, Dent and Winter (1974) reported on a case of hypophosphatemia causing symptomatic osteomalacia following excessive aluminium antacids in an otherwise healthy patient [

37]. Since then, many case reports too numerous to mention describe aluminium intoxication in healthy people following use of aluminium containing antacids.

4. Discussion

The purpose at the outset of this query was to reconcile why PTH is associated with aluminium retention, yet aluminium decreases PTH in patients with uremia. The preceding review resolved that question and established that aluminium toxicity is a phosphate wasting disease. But the review also opened a floodgate of compelling information further implicating aluminium in autism causation. A narrative review seemed more appropriate upon proceeding.

The discussion takes a macro view of aluminium toxicity, an assessment of phosphatropic and calciotropic hormonal influence on aluminium excretion. An extensive review of PTH control on aluminium trajectory to the tissues exceeds the scope of this paper. But a brief discussion later may provide insight on the poorly understood aluminium flux across cellular membranes [

38]. The distribution of PTH receptors seems to determine aluminium trajectory to the tissues during a toxic event.

But first, pre-existing hypophosphatemia is synergistic with renal aluminium retention [

10]. Aluminium perpetuates hypophosphatemia, hypophosphatemia perpetuates aluminium retention, and a vicious circle ensues. Hypophosphatemia acidifies the plasma [

39,

40]. Lower plasma pH increases citrate reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubules [

41,

42]. As citrate is metabolized, aluminium uses phosphate as a secondary chelator, sacrificing even more phosphate. Aluminium then becomes available for reabsorption in the loop of Henle [

11,

43]. Rising plasma aluminium reduces the rate of aluminium filtration [

11].

There are many other causes of acidosis and hypocitraturia that might impair aluminium excretion. Acidosis need not to be present for hypocitraturia to occur. Hypocitraturia can also be caused by CKD, diarrhea, malabsorption, excessive exercise, ketogenic diets, hypokalemia, high salt diet, several medications, and other causes [

44]. These, and the many causes for acidosis may all be risk factors for endemic aluminium intoxication. But the run-away risk factor for epidemic aluminium intoxication that we may have been calling autism would be hypophosphatemia secondary to vitamin D insufficiency.

4.1. A Novel Hypothesis Explaining the Male Gender Bias and Susceptibility to Aluminium Toxicity

4.1.1. Disorders of Phosphate Homeostasis

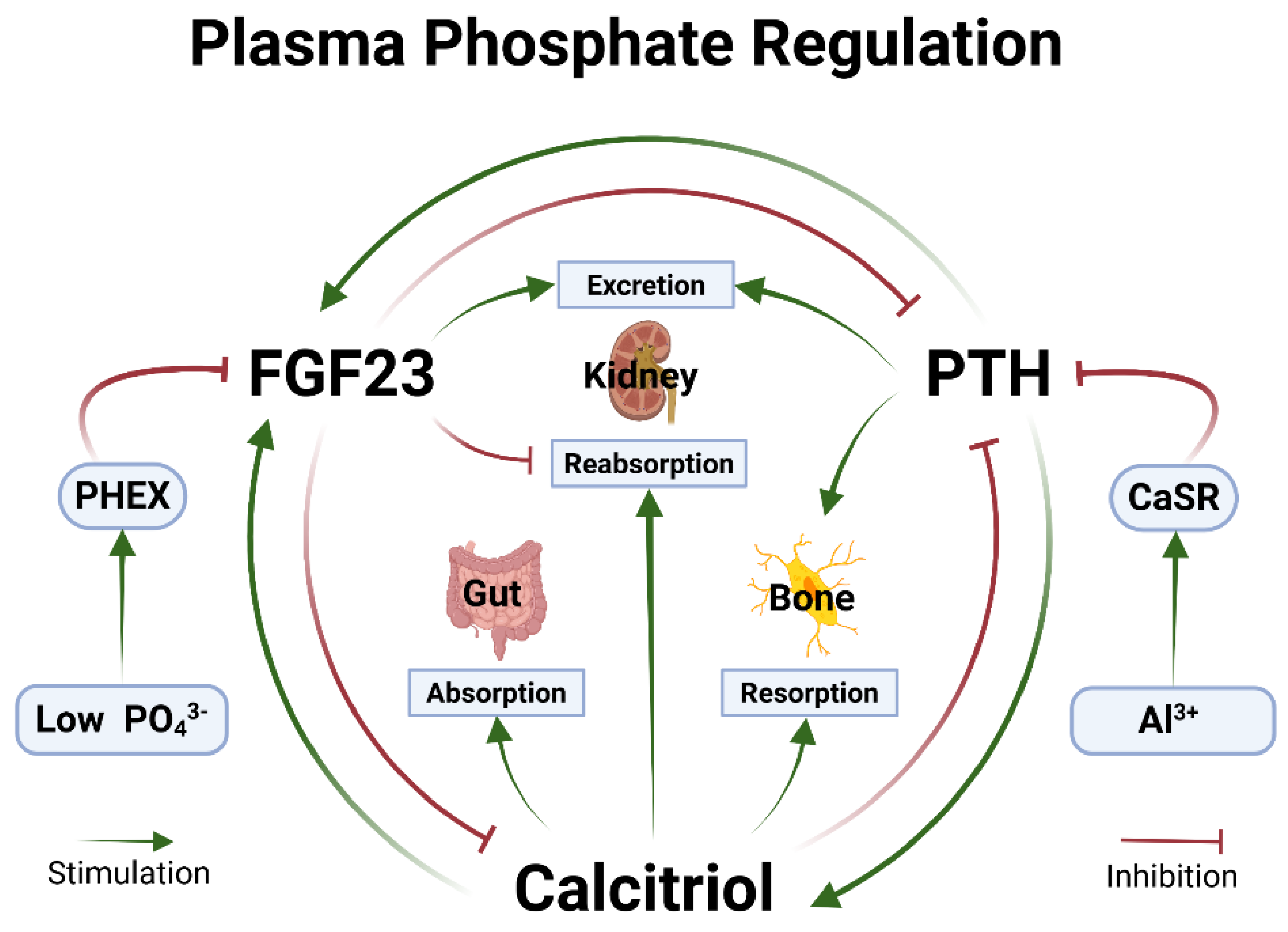

Disruptions in the hormonal control of phosphate homeostasis underlie susceptibility to aluminium toxicity and the male gender bias. Normal phosphate homeostasis is illustrated in

Figure 1. Five disorders that cause persistent hypophosphatemia were selected for review later. The association between disorders of phosphate homeostasis and autism is well established [

45,

46]. These disorders may be preexisting and become worse as aluminium leaches from adjuvant particulates [

47] after repeated vaccine injections. An underlying tendency towards hypophosphatemia may render a child susceptible to aluminium toxicity after dosing that is well tolerated otherwise.

Figure 1.

Phosphate homeostasis. Plasma PO

43- concentration varies normally during dynamic metabolic states. Minimum PO

43- concentration is a function of PTH and/or calcitriol effect on kidney reabsorption and bone or gut to absorb PO

43- into the plasma. FGF23 acts on the kidneys to excrete PO

43- when it’s high. PHEX enzyme checks FGF23 to prevent over-excretion preventing hypophosphatemia [

50]. Al

3+ stimulates CaSR inappropriately to inhibit PTH secretion (See text).

Abbreviations: Al3+ - Aluminium cation;

CaSR - Calcium sensing receptor;

FGF23 - Fibroblast growth factor-23;

PHEX - Phosphate regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X-chromosome;

PO43-- Phosphate;

PTH - Parathyroid hormone;

RTC - Renal tubular cells. Created in BioRender. Kette, S. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/tds9db2.

Figure 1.

Phosphate homeostasis. Plasma PO

43- concentration varies normally during dynamic metabolic states. Minimum PO

43- concentration is a function of PTH and/or calcitriol effect on kidney reabsorption and bone or gut to absorb PO

43- into the plasma. FGF23 acts on the kidneys to excrete PO

43- when it’s high. PHEX enzyme checks FGF23 to prevent over-excretion preventing hypophosphatemia [

50]. Al

3+ stimulates CaSR inappropriately to inhibit PTH secretion (See text).

Abbreviations: Al3+ - Aluminium cation;

CaSR - Calcium sensing receptor;

FGF23 - Fibroblast growth factor-23;

PHEX - Phosphate regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X-chromosome;

PO43-- Phosphate;

PTH - Parathyroid hormone;

RTC - Renal tubular cells. Created in BioRender. Kette, S. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/tds9db2.

4.1.2. Normal Excretion of Aluminium

Normal aluminium excretion requires citrate and phosphate in the renal tubules. Aluminium is carried mostly by transferrin and other proteins, and in complexes with citrate and phosphate in the plasma. Citrate is instrumental in shuttling aluminium from transferrin, the primary plasma aluminium transporter, through ligand exchange [

48]. Complexes of aluminium with citrate can readily pass through the glomerular filter [

4]. Citrate is the primary anion that carries aluminium safely into the bladder with minimal reabsorption [

11,

49].

4.1.3. Metabolic Acidosis Due to Hypophosphatemia Increases Citrate Metabolism

The kidney tubules will reabsorb aluminium without adequate citrate in the glomerular filtrate. As plasma phosphate concentration decreases, plasma pH decreases, and citrate availability in the renal tubules decreases.

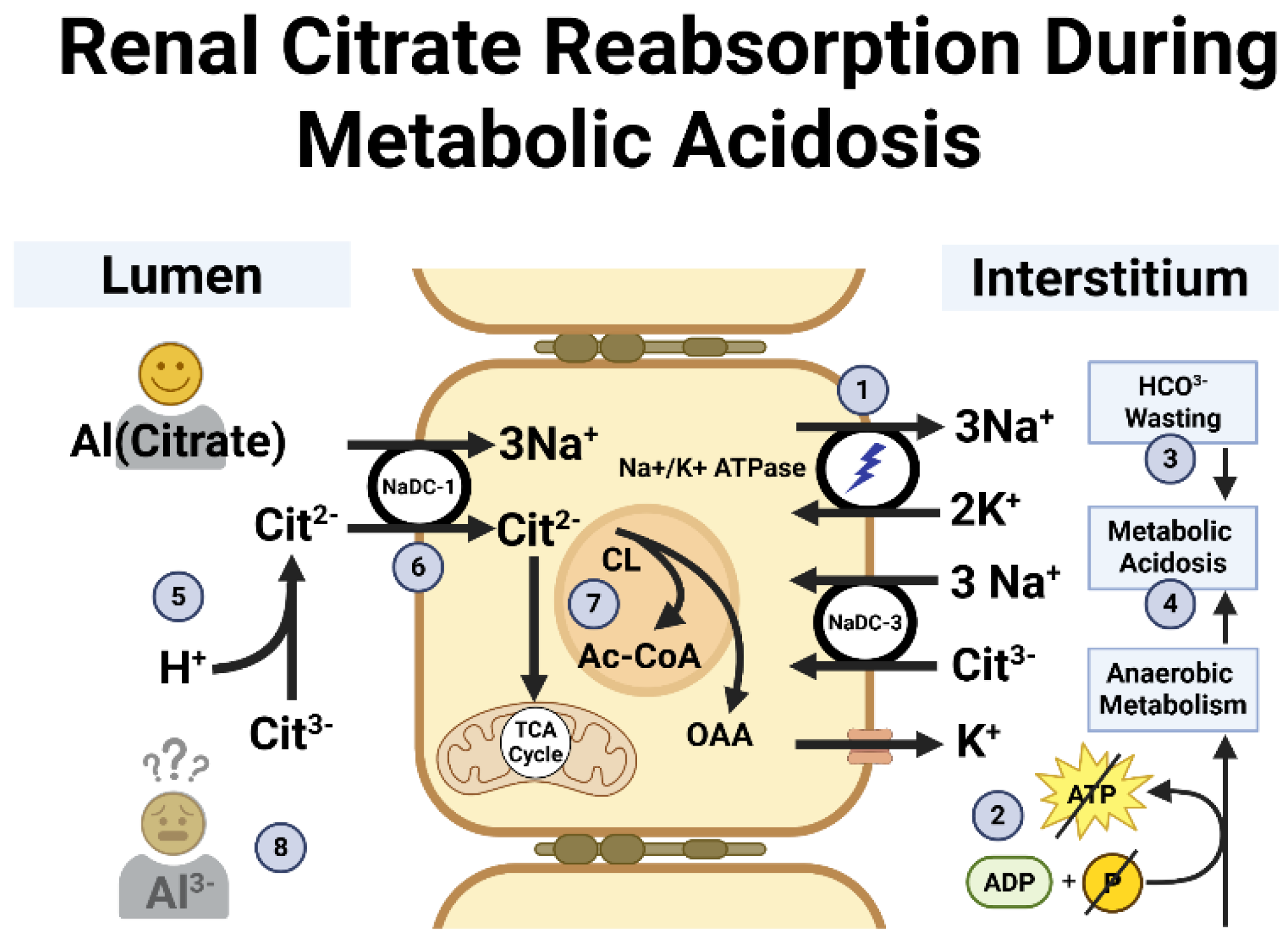

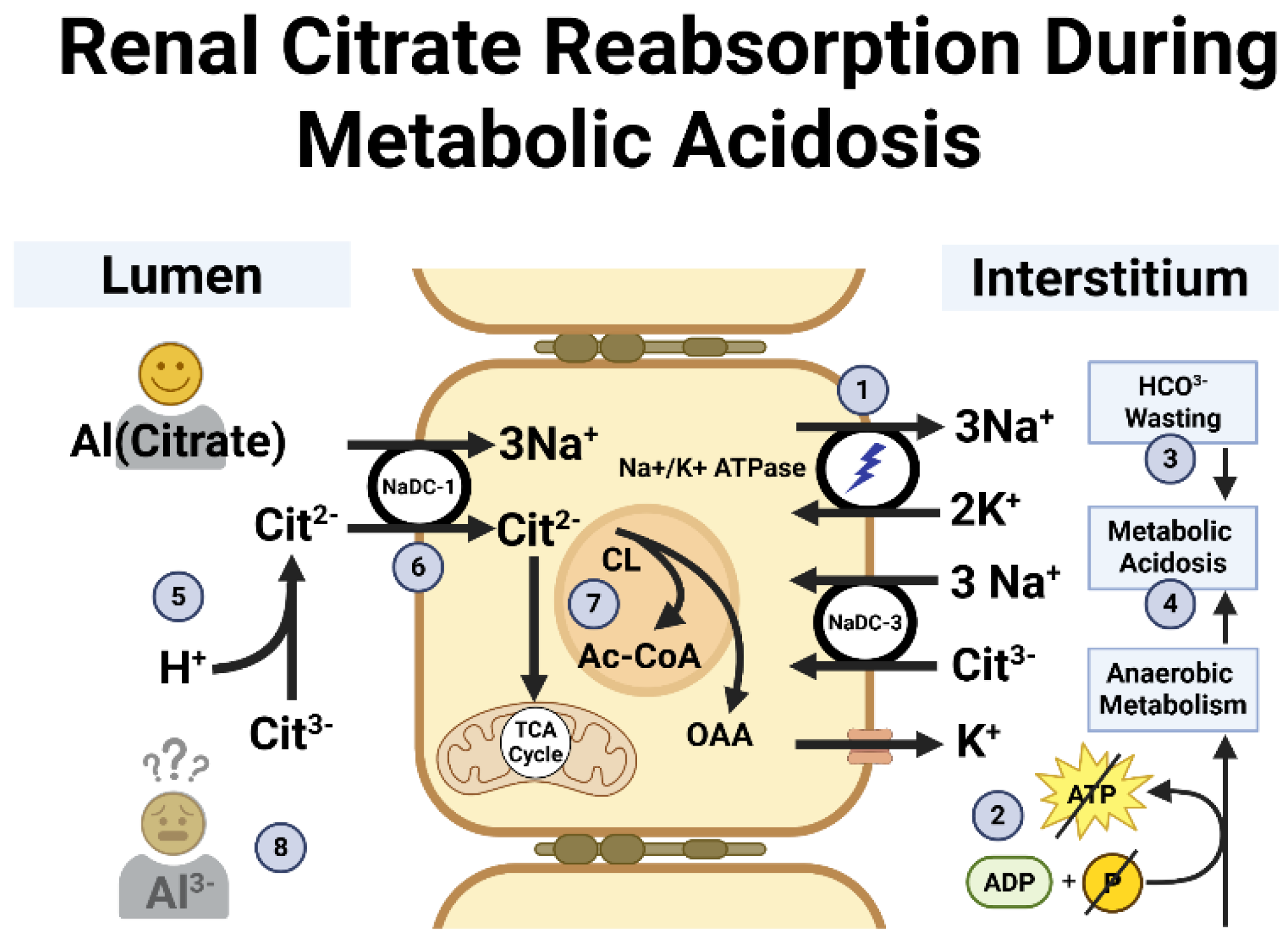

Figure 2 illustrates the function of renal cell handling of citrate during states of metabolic acidosis. Low phosphate supply impairs conversion of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which then causes anaerobic metabolism [

39]. This causes a drop in plasma pH. Also, metabolic acidosis results because hPTH causes bicarbonate wasting [

50].

To compensate for the tendency toward acidosis, the kidney tubules will reabsorb and metabolize citrate. Acid-base balance and expression of the Na

+-dicarboxylate cotransporter control citrate reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubules [

40,

42]. Extreme hypophosphatemia causes metabolic acidosis [

39,

40]. But hypophosphatemia need not be extreme as plasma pH falls decrementally and may be compensated during the process. Nevertheless, citrate is less available to chelate aluminium efficiently in the glomerular filtrate when PTH is sufficiently high.

Figure 2.

Renal tubular cell handling of citrate in response to low phosphate and metabolic acidosis.

1. The Na+/K+ ATPase pump powers the system by creating an electrochemical gradient that facilitates Cit

2- entry into the cell.

2. Low phosphate impairs conversion of ADP to ATP causing anaerobic metabolism [

39].

3. hPTH causes renal HCO

3- wasting [

50].

4. Lactate and α-β-hydroxybutyric acid accumulate [

39].

5. H

+ surplus favors Cit

2-.

6. Na

+-dicarboxylate cotransporter transfers Cit

2- into the cell.

7. Intracellular Cit

2- metabolism [

41,

42].

8. Cit

3- is unavailable to escort Al

3- to the bladder for safe excretion (See text).

Abbreviations: Ac-CoA - Acetyl CoA; ADP - adenosine diphosphate; Al

3- - Aluminium cation; ATP - Adenosine triphosphate; Cit

2- - Citrate anion in dicarboxylate form; Cit

3- - Citrate anion in tricarboxylate form; CL - Citrate lyase; H

+ - Hydrogen/proton; HCO

3- - Bicarbonate; hPTH - Hyperparathyroidism K

+ - Potassium; Na

+ - Sodium; NaDC - Sodium/dicarboxylate cotransporter; Na+/K+ ATPase - Sodium-potassium pump; OAA - Oxaloacetate; phosphate - Phosphate; TCA - Tricarboxylic acid. Created in BioRender. Kette, S. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/v3s49lm.

Figure 2.

Renal tubular cell handling of citrate in response to low phosphate and metabolic acidosis.

1. The Na+/K+ ATPase pump powers the system by creating an electrochemical gradient that facilitates Cit

2- entry into the cell.

2. Low phosphate impairs conversion of ADP to ATP causing anaerobic metabolism [

39].

3. hPTH causes renal HCO

3- wasting [

50].

4. Lactate and α-β-hydroxybutyric acid accumulate [

39].

5. H

+ surplus favors Cit

2-.

6. Na

+-dicarboxylate cotransporter transfers Cit

2- into the cell.

7. Intracellular Cit

2- metabolism [

41,

42].

8. Cit

3- is unavailable to escort Al

3- to the bladder for safe excretion (See text).

Abbreviations: Ac-CoA - Acetyl CoA; ADP - adenosine diphosphate; Al

3- - Aluminium cation; ATP - Adenosine triphosphate; Cit

2- - Citrate anion in dicarboxylate form; Cit

3- - Citrate anion in tricarboxylate form; CL - Citrate lyase; H

+ - Hydrogen/proton; HCO

3- - Bicarbonate; hPTH - Hyperparathyroidism K

+ - Potassium; Na

+ - Sodium; NaDC - Sodium/dicarboxylate cotransporter; Na+/K+ ATPase - Sodium-potassium pump; OAA - Oxaloacetate; phosphate - Phosphate; TCA - Tricarboxylic acid. Created in BioRender. Kette, S. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/v3s49lm.

4.1.4. Aluminium Needs Another Anion to Remain Solvated if Citrate Is Metabolized

Although citrate dominates phosphate in the competition for aluminium binding [

5], aluminium excretion requires phosphate in the glomerular filtrate as a backup chelator. Once in the filtrate, aluminium can form insoluble complexes with phosphate that the tubules don’t reabsorb. Normally, aluminium phosphate is a component of the amorphous sediment seen on microscopic examination during urinalysis [

52]. But if plasma phosphate concentration is too low, then phosphate concentration in the glomerular filtrate is too low [

51]. If both phosphate and citrate are insufficient, anions fixed to calcium transporters on renal cells may be the only ligands remaining to attract aluminium. Ultimately, aluminium reabsorption happens in the loop of Henle [

11,

43,

49].

Reasoning that supports the notion that phosphate escorts aluminium to the bladder as a secondary chelator is based on the principle by which oral aluminium binds with phosphate in the gut. But in the kidney, precious phosphate is excreted as aluminium phosphate, thus being sacrificed for the noble cause to excrete aluminium. The costly tradeoff is a nudge favoring the deepening state of hypophosphatemia.

4.1.5. Demand for PHEX Enzyme to Stop Phosphate Wasting Exceeds the Rate of Expression

The basis of the hypothesis for a male gender bias in aluminium toxicity is that the high demand for PHEX enzyme imposed by low plasma phosphate concentration exceeds the rate of supply. PHEX enzyme takes time for synthesis. There was no evidence found that osteocytes hold sufficient PHEX enzyme in storage. It is more likely expressed on demand. If the demand exceeds the rate of expression, then FGF23 remains disinhibited and inappropriate phosphate excretion may increase. Subsequently, plasma pH decreases, renal citrate resorption and metabolism increase, normal aluminium chelation with citrate decreases, phosphate is sacrificed, and aluminium becomes more available for reabsorption.

4.1.6. The X-Linked Female Protective Effect

There is nothing novel about a possible female X-linked causal effect in autism. Mendes, et al. (2025) entertained the possibility. They proposed several candidate genes including FGF23. But it is more conceivable that FGF23 mutations would cause hyperphosphatemia. Although they didn’t identify PHEX, autism is associated with hypophosphatemia [

45,

46].

PHEX enzyme supply is more limited in boys because PHEX gene is located on the X chromosome. Off-handed reasoning that suggests girls have a double dose of PHEX gene expression holds true. Lyonization is a process during female embryonic development where the redundant X chromosome is deactivated to prevent double X gene dosing. But not all genes are fully Lyonized [

53]. The PHEX gene is among those that variably escape Lyonization in girls [

54].

The duplicated PHEX gene may have undergone more complete Lyonization in vaccinated girls with autism, whereas, the duplicated PHEX gene may have escaped Lyonization in fully vaccinated girls without autism. This could be tested using unaffected fully vaccinated girls as a control group, however it would be difficult to control for aberrant phosphate homeostasis that may have occurred during the earlier years of the child’s life.

HOL provides evidence that the supply of PHEX enzyme in girls is more abundant than in boys. Girls would be more able to satisfy the high demand for PHEX enzyme created when aluminium exposure and pre-existing hypophosphatemia converge. This may very well explain the gender bias in autism.

The CDC reported that the gender ratio in autism decreased from 4.2:1 in 2018 to 3.8:1 in 2022. They attributed the converging gender ratio to improved identification in girls [

12]. On the other hand, if convergence of the gender ratio is attributed to increasing aluminium exposure, this would be consistent with the hypothesis that the demand for PHEX enzyme exceeds the rate of supply. Increasing aluminium exposures may eventually overwhelm the X-linked female protective factor in more girls. The gender ratio could converge to 1:1 as prevalence approaches 100% if aluminium exposures continue to increase.

4.1.7. Other Factors Can Inhibit PHEX Expression

Other factors may compound the problem of limited PHEX enzyme expression. They include but may not be limited to hPTH, activated vitamin D [

55], and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [

56]. This opens Pandora’s box of risk factors for phosphate wasting. TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine that is increased in viral and bacterial infections. Aluminium itself induces TNF-α secretion [

57]. Maybe pediatricians should wait until sick children are well before injecting them with aluminium. Any mechanism for inhibition of PHEX enzyme expression probably increases susceptibility to aluminium intoxication.

The remainder of this paper provides further explanations, evidence, and citations supporting this hypothesis and why it was missed. It is tedious but necessary to review selected disorders of phosphate homeostasis and aluminium toxicity. There are many others too numerous for review here.

4.2. Selected Disorders of Phosphate Homeostasis

Acquired and genetic disorders of phosphate homeostasis may alter the toxicokinetics of aluminium. Disorders selected for focused review include CKD, primary hPTH, XLH, HOL, and vitamin-D insufficiency.

Table 1 summarizes them. HOL is omitted from

Table 1 because data is insufficient due to it being such a rare disease.

4.2.1. Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD patients on dialysis were especially prone to aluminium toxicity during the early 1970’s. It was termed, “dialysis dementia” before aluminium in the dialysate solution was found to be the cause. Like autism, speech loss was a common presenting symptom. Patients were reported to express frustration with the loss of speech and inability to communicate before the disease progressed to dementia [

58].

Authors casually writing about aluminium safety often remark that CKD patients are the only individuals at risk for aluminium toxicity. They typically presume that toxicity is caused by aluminium not passing the glomerulus. But aluminium is small enough that it easily passes through the glomerulus [

11]. Phosphate, however is retained because it is a large molecule and because of nephron loss in kidney disease. Aluminium does not pass the glomerulus as readily because of its attraction to unfilterable phosphate and other high molecular mass complexes which are trapped in the plasma. Plasma citrate facilitates aluminium passing through the filter in such case [

48], where aluminium then becomes available for excretion or reabsorption in the loop of Henle [

11,

43,

49].

Unlike the other disorders selected for review, CKD causes hyperphosphatemia. PTH becomes elevated as the result of hypocalcemia in CKD. There is evidence, however, of hypophosphatemia occurring in CKD due to over-treatment with aluminium used as gut phosphate binders as mentioned earlier. It is possible in these cases that aluminium induced hypophosphatemia seen in CKD was reducing plasma pH, increasing citrate reabsorption, and eliminating citrate as a chelator to escort aluminium to the bladder. Hypocitraturia is common in CKD and may actually be the primary problem that causes aluminium retention in some of these patients [

59].

There is no report of a male gender bias in aluminium toxicity due to CKD. This should be expected because aluminium excretion is impaired due to poor filtration. Furthermore, unlike impaired excretion due to renal tubular reabsorption, there is no call for PHEX enzyme to inhibit FGF-23 during a state of hyperphosphatemia. There is evidence of a link between kidney disease and developmental disabilities, autism and unspecified behavioral changes [

60,

61,

62].

4.2.2. Primary Hyperparathyroidism

The underlying problem in primary hPTH is inappropriate PTH secretion. It is caused by parathyroid gland tumors and hyperplasia [

63,

64]. It can be caused by several other problems, for example, mutation of the gene that expresses CaSR [

65]. Mayor, et al. (1980) actually reproduced primary hPTH using exogenous PTH in healthy rats when performing the landmark experiment to ascertain the role of PTH in uremic patients with aluminium toxicity [

18]. This experiment proved that CKD is not the only disease that predisposes people to aluminium toxicity. PTH in excess by any means causes hypophosphatemia and hypercalcemia. PTH acts directly on proximal convoluted tubules and to some degree, indirectly by prompting FGF23 to inhibit phosphate reabsorption [

63,

64,

66,

67]. Primary hPTH is rare in children [

68]. There was no information linking it with autism. But it is associated with cognitive impairment and dementia [

69].

4.2.3. X-Linked Hypophosphatemia

This causes X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. The primary driver in XLH is uninhibited FGF23. The PHEX gene expresses PHEX enzyme [

30]. PHEX enzyme inhibits FGF-23 normally when plasma phosphate concentration subsides to a desirable concentration [

50]. In XLH, mutations in the PHEX gene cause poor quality or absent PHEX enzyme expression [

30,

70]. FGF-23 is uninhibited in XLH resulting in hypophosphatemia.

A demographic study on XLH with 579 XLH patients found that 64% were female [

71]. Other papers report no differences in severity based upon gender [

72,

73]. This might weaken the hypothesis off-hand. However, a series of 38 radiologic examinations of untreated adults showed men to be more severely affected by bone changes [

74]. The genotype of XLH does not correspond with the severity of phenotype expression in women. The explanation is unclear, but perhaps variable X chromosome inactivation in women and gene dosing is involved [

70].

Genetic autism causation enthusiasts should look here. XLH is an X-linked dominant inherited disorder. There is no father to son transmission. There are at least 729 PHEX variants that impart a spectrum of severity in presentation of the disease [

70]. XLH isn’t a terribly common disorder, so there will not be sufficient data linking XLH and autism. However, there is a case report of XLH wherein the authors hypothesized that 10-15% of autism can be attributable to PHEX gene variants. This estimation was based on the percentage of autism classified genetically as “syndromal autism” [

75].

4.2.4. Hypophosphatemia of Leprosy

Like XLH, the driver in HOL is uninhibited FGF23. It is reasonable to believe that the supply of PHEX enzyme in girls can be up to twofold more abundant than previously discussed. The pathophysiology of HOL provides stronger evidence of a limited supply of PHEX enzyme in boys and variably in some girls. HOL is a natural experiment that helps to prove the case.

Mycoplasma leprae inhibits PHEX enzyme expression in osteocytes and Schwann cells [

76,

77]. The profound hypophosphatemia seen in HOL causes skeletal malformations resulting in a 2:1 gender bias toward males for physical disability [

78]. Although

Mycoplasma leprae infection is rare, it illustrates the greater potential for PHEX enzyme depletion in boys.

4.2.5. Vitamin D Insufficiency

Vitamin D insufficiency must be distinguished from calcitriol insufficiency. Calcitriol is the hormone form of vitamin D. There is a myriad of problems converting vitamin D to calcitriol such as mutated genes that express the necessary enzymes. Also, calcitriol can be plentiful yet ineffective due to abnormal receptor sites. In vitamin D insufficiency, calcitriol is insufficient because there is insufficient vitamin D available to convert [

79,

80]. Children with dark skin are at particularly high risk [

81]. The prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency is 42.4% of black and 4.2% of white women of child bearing age [

82]. This may explain the skewed race ratio in autism [

12].

Plasma phosphate concentration is low in vitamin D insufficiency due to reduced phosphate resorption from bone and poor absorption by the gut. Simultaneously, FGF23 remains highly active under excessive PTH stimulation causing inappropriate phosphate excretion when plasma concentration is already low [

83]. This is worrisome when aluminium reduces plasma phosphate concentration even more. And when children run low on PHEX enzyme to inhibit FGF23 over-secretion, aluminium toxicity may result.

Table 2 summarizes the proposed causal cascade leading to toxicity.

Although any disorder of calcium and phosphate homeostasis may confer the risk of aluminium toxicity, vitamin D insufficiency is the

sine qua non for the autism epidemic. Innumerable papers cover the link between autism and vitamin D insufficiency. Pioneers in this research led by Grant and Cannell have recognized the strong link between vitamin D insufficiency and autism [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. Their work highlights observations that U.S. autism exceptional student educational enrollment rates are generally higher among less sun exposed populations such as those in northern states.

4.3. Is Aluminium Distribution to the Tissues Determined by Parathyroid Hormone Receptors?

Although the primary focus of this paper is the synergy between aluminium and preexisting disorders causing hypophosphatemia, the value of assessing the distribution of aluminium to the tissues might provide evidence of the role that PTH plays in aluminium retention and toxicity. Not only are hypophosphatemia, acidosis, hypocitraturia and aluminium retention downstream effects of hPTH (discussed throughout this paper), PTH alters aluminium trajectory to the tissues according to the distribution of PTH receptors.

Bago, et al. (2008, 2009) identified locations in the brainstem of PTH2 receptors [

90,

91]. The distribution of PTH2 receptors may reflect the mapping of brainstem deficits observed clinically in autism cases as described by McGinnis, et al. (2013) and others [

92,

93,

94,

95]. The manner in which calcium enters the brain might also explain how aluminium enters the brain, and we know that it does [

96,

97]. Exley and Mold (2013) provide excellent insights on how this might happen [

38].

The very fact that PTH drives aluminium to the brain [

18] and other tissues suggests that aluminium follows calcium channels under PTH control [

4]. PTH is the master hormone for calcium homeostasis and the driver of calcium to the cells. There is also evidence that aluminium may follow iron pathways after being carried by transferrin [

4,

13]. But PTH isn’t known to mediate iron transport.

There are a few PTH/calcitriol-controlled calcium transport channels that are candidates for hijacking by aluminium. Store-operated calcium entry is a PTH controlled calcium pathway [

98]. Calcitriol, when activated by PTH, mediates paracellular transport of calcium across tight junctions [

99]. PTH action to convert vitamin D to calcitriol activates endothelial transient receptor potential vanilloid 5 (TRPV5) and TRPV6 [

100]. These TRPV channels may mediate aluminium flux across gut epithelium [

101], thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, and distal convoluted tubules [

67]. Aluminium must necessarily pass through TPRV6 calcium channels in order to interact with calmodulin, an integral part of this mostly ion specific channel [

7].

TPRV5 and TPRV6 are thought to be highly calcium specific [

102]. However, over-expression can lead to cadmium and zinc toxicity [

103]. Peng, et al. (1999) used xenopus oocytes to determine whether other cations can pass into the TRPV6 gateway. Sodium, calcium, and barium can pass. Other ions tested included magnesium, gadolinium, lanthanum, iron, copper, lead cadmium, cobalt, zinc and nickel [

104,

105]. Aluminium was not tested. There was no other evidence found that proves trans-cellular gateways for aluminium. However, literature search did reveal that a xenopus is a water frog, with claws [

106].

4.4. How it Was Missed

4.4.1. The “ADME” Acronym

ADME is a teaching tool used in toxicology and pharmacology to impress upon students the rigid requirement to evaluate every one of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of a substance. The aluminium debate and the bulk of messaging on aluminium safety focuses only on administration (which also entertains the degree of exposure). The need for attention to safe excretion has been neglected.

4.4.2. Administration and Dosage; Proof of Safety

The notion that aluminium in vaccines has been proven safe merely by claims of low dosing and the ostensible lack of evidence of any harm violates logic because an absence of evidence proves nothing [

107]. In this case, establishment vaccine scientists claim aluminium has been proven safe for one and all based simply on low exposures. Never mind susceptibility. Keith, et al. (2007) reviewed aluminium toxicokinetics in childhood vaccines with an implicit assumption that aluminium is always safely excreted [

108]. Mitkus, et al. (2013) proclaimed the childhood vaccine schedule to be universally safe based upon minimum risk levels derived from adult data. There were no exceptions considered for individuals susceptible to aluminium toxicity [

109].

Lyons-Weiler and Ricketson (2018) is the most outstanding paper that enumerates aluminium body burden imposed upon children by the vaccine schedule. It considers a child’s body weight in calculating a more realistic minimum risk level of aluminium in pediatric vaccine practice [

110]. McFarland, et al. (2020) assessed infant aluminium exposure through vaccines and environment. The CDC recommended vaccine schedule alone exceeds safe exposure levels, environmental exposure notwithstanding [

111]. While the modes of administration and degree of exposure are exquisitely relevant, aluminium metabolism and excretion are also important because therein lies the susceptibility.

4.4.3. Metabolism and Excretion; Evidence Ignored

The reassurance of safety based on absence evidence requires not looking, ignoring evidence to the contrary, or low research testing sensitivity [

107]. The lack of attention to aluminium distribution and excretion is amazing considering its extensive use in vaccines, medicines, and cosmetics. Noteworthy papers on the safety profile of aluminium are available on-line and are quite comprehensive. The U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s (ATSDR) most recent update bears a review on susceptibility to infections after aluminium exposure and children’s susceptibility to toxins in general. ATSDR did not address metabolic or genetic susceptibilities to aluminium intoxication [

112]. Krewski, et.al. (2007) did cite papers supporting that people with CKD, pregnancy, and premature birth are at higher risk due to impaired excretion [

113]. But there were no papers found that specifically address disorders of phosphate homeostasis as susceptibility factors except that of kidney disease. Some authors may infer that aluminium toxicity in CKD is caused by it’s not passing through the glomerulus making it the only risk factor. This is simply incorrect. The truth is that any disorder with high PTH and hypophosphatemia confers susceptibility.

4.4.4. The Unheeded Warning

The lion’s share of papers on the PTH-aluminium link emanated from Michigan State University. In the hallmark paper, Burnatowska-Hledin, et al. (1983) wrote explicitly that smaller exposures than what occur during CKD treatment such as in the diet and medications are also causes for concern, that impaired kidney function is not necessary for aluminium retention and toxicity. They explicitly warned about the likelihood that toxicity can occur in populations other than those with renal disease. As noted earlier, they probably solved the mystery of the autism epidemic long before it happened. Efforts to locate that paper were futile, including contacting the lead author. Nonetheless, the abstract is irrefutable evidence that the warning was issued [

24].

But the warning continues to be ignored. Heretofore, a commonly quoted justification for unlimited use of aluminium in vaccines is as follows: “

The widespread use of aluminum adjuvants can be attributed in part to the excellent safety record based on a 70-year history of use.” [

114]. This logic, based on

circulus in probando, reads that aluminium is safe because we use it a lot and we use it a lot because it is safe [

115]. This works as long as we comply with the implicit requirement to dismiss valid evidence of risk as “theoretical concerns” [

116]. Industry scientists recently reiterated their intent to use aluminium into infinity and beyond without limitations or precautions using the same line of reasoning [

117].

4.4.5. Susceptibility must be Considered in Population Study Designs

Andersson, et al. (2025) collected data on 1.38 million vaccinated Danish children to assess hazard ratios for several autoimmune, allergic, and neurodevelopmental outcomes. They divided the vaccinated children into exposure groups distinguished from each other by 1 mg increments of injected aluminium by the age of two years. They averaged the hazard ratios between adjacent groups having no more than 1 mg difference in exposure. This methodology failed to detect concerning hazard ratios between the groups. They did not calculate the hazard ratio between the lowest and highest dosage groups [

118]. But even that could fail to demonstrate increased risk in the higher dose groups. Susceptibility factors might place children in the lowest dosage groups at high risk. The study design lacked any accounting for susceptibility. Yet, lay and social media pundits echoed the conclusion that aluminium was proven to be safe for one and all.

Forty years ago, when medical practice was controlled by physicians, nephrologists had sufficient evidence and the wisdom to stop using aluminium in uremic patients. They did not need to prove the Michaelis-Minton constant for aluminium and calcium transport protein in xenopus oocytes [

104]. Physicians must assert control of their practices once again, and resume treating individuals instead of populations.

5. Conclusions

This review explicates the hypothesis of a male gender bias and susceptibility to aluminium toxicity. Disorders of phosphate homeostasis probably confer risk at exposure levels that are otherwise well tolerated. Girls are likely to be protected by their ability to express more PHEX endopeptidase on the duplicate X chromosome whereas boys only have one X chromosome. Nevertheless, efforts to identify environmental causes of autism should continue regardless of how compelling this hypothesis may be.

CKD is currently the only recognized risk factor for aluminium toxicity due to limited filtration of aluminium bound by phosphate in the plasma. But susceptibility to aluminium toxicity extends beyond that caused by kidney disease. hPTH by any other means can impair aluminium excretion due to reabsorption of filtered aluminium. In either case, hPTH drives retained aluminium to body tissues. However, some paper titles appear contradictory because aluminium also reduces PTH. The dichotomy leads to a hasty dismissal that hPTH has a role in aluminium toxicity. In fact, aluminium reducing PTH during an intoxication event may be ominous. A systematic review of literature to resolve the contradiction incidentally revealed compelling evidence that might explain the autism epidemic better than “increased awareness”.

Any preexisting disorder with hPTH, subsequent phosphate wasting, metabolic acidosis, or hypocitraturia probably confers susceptibility. Hypophosphatemia is a hallmark of aluminium toxicity. Low phosphate concentration acidifies the plasma which, in-turn, increases citrate reabsorption by the kidney tubules. But citrate is the primary aluminium chelator in the glomerular filtrate. As citrate is metabolized, aluminium reabsorption increases in the loop of Henle. Ultimately, PTH receptor distribution determines the trajectory of aluminium to the tissues during an intoxication event.

The male-biased gender ratio in autism may be explained by a more limited supply of the enzyme expressed by the PHEX gene. PHEX enzyme is required to limit phosphate wasting. If the duplicated PHEX gene in girls variably escapes inactivation, then expression of PHEX enzyme confers a protective effect in most, but not all girls.

Vitamin D insufficiency, the second most common cause of secondary hPTH, would be the sine qua non for the autism epidemic. This is illustrated by a higher prevalence of autism among non-white children and those living in less sun exposed climates. The hypothesis of susceptibility and the reason for the gender ratio presented herein is consistent with the model that autism has environmental causation with genetically mediated susceptibility.

Although this paper might contribute to the conclusion that aluminium is a sufficient cause for the autism epidemic, it does not stand alone as a justification to conclude that aluminium containing vaccines are the sole cause [

14]. Aluminium exposures according to the childhood vaccine schedule may be a major contributing cause. But other sources of aluminium can contribute to toxicity. Furthermore, this paper is not a recommendation for or against vaccination practice. Parents are advised to consult with their pediatricians on any concerns about vaccine safety. Vaccines notwithstanding, empirical research on susceptibility to aluminium toxicity and development of pre-vaccination screening standards are needed.

It is important, however, to consider that pre-vaccination screening may have limited benefits. First, aluminium has a bi-modal mechanism of toxicity. It has direct toxic effects such as that seen in CKD and perhaps immediately following a battery of childhood vaccines. It is also immunotoxic where autoimmunity may result [

119,

120]. A given aluminium load may not precipitate symptoms of

acute toxicity yet be sufficient to cause delayed autoimmunity. As for autoimmunity, there may be no safe level of exposure. Risk screening will merely prevent acute toxic effects in susceptible babies. Second, most neonates have physiologically high PTH within 24 hours of birth, peaking at seven days, and gradually decreasing until plasma calcium, phosphate, and calcitonin normalize [

121]. Therefore, pre-screening newborns would be fruitless because almost all of them might not meet criteria for safe vaccination. Fortunately, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice has removed the aluminium containing hepatitis B birth dose from the recommended childhood vaccine schedule. Finally, pre-natal aluminium containing antacids, maternal dietary aluminium and vaccines, and post-natal dietary aluminium exposure may be cause sufficient among susceptible populations. Pre-vaccination screening would not prevent these exposures.

We are years away from safely deploying alternative adjuvants due to the time needed for research and development, and safety and efficacy trials. In the meantime, we should not wait while another generation of children suffers from the risk of aluminium intoxication.

Effective pre-vaccine screening for susceptibility to aluminium toxicity should not obviate the need for continued development of alternative vaccine adjuvants or enable a continuing increase of aluminium burden by expanding the vaccine schedule. To the contrary, eliminating non-essential immunizations during childhood such as the aluminium containing hepatitis B vaccine will make way for safer administration of the more essential childhood vaccines.

Until more empirical evidence becomes available, the risk of the remedy determines the standard of evidence for causation. The standard of evidence is low because there is no risk in taking these measures to mediate the autism epidemic [

14]. Therefore, we should recognize the immediate need to avoid unnecessary aluminium exposure. Where necessary elective use and unavoidable exposures are concerned, pre-vaccination screening and correcting disorders that confer susceptibility should be considered before proceeding.

The gravity of the problem demands this approach. If the weight of current evidence meets a higher standard that indicates permanent changes in vaccination practice, then pediatricians should never send another afflicted child home with a psychiatric diagnosis.

Highlights

Al reducing PTH during a toxic event does so inappropriately. It is not reassuring. In fact, it may be an ominous sign of a deepening state of toxicity.

Pre-existing risk for Al toxicity extends beyond that of kidney disease. Recognized risks should also include all conditions causing hPTH, hypophosphatemia, and hypocitraturia.

Citrate is the primary chelator for aluminium in urine. Hypophosphatemia causes decreased plasma pH which in turn increases reabsorption of citrate in the kidneys. phosphate, a secondary chelator, may not be sufficient, thereby allowing aluminium retention and toxicity.

Boys are at higher risk due to the inability to meet demands for PHEX endopeptidase to control phosphate wasting. Variable X-chromosome inactivation in girls confers variable protection. Vitamin D insufficiency places people with dark skin at higher risk.

Hyperphosphatemia drives aluminium retention by the kidneys. PTH and its receptors determine aluminium distribution to the tissues during a toxic event.

Recognizing and treating high risk conditions before administering Al containing vaccines should reduce the risk for toxicity. People with history of disordered phosphate homeostasis and hPTH should avoid unnecessary Al exposures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Aluminum is spelled “aluminium” to acknowledge scientists investigating the autism epidemic with unwavering integrity despite significant personal sacrifice.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest relevant to this research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDC |

U.S. Centers for Disease Control |

| Al |

Aluminium |

| Al3+

|

Aluminium (cation) |

| Ca2+

|

Calcium (cation) |

| CaSR |

Calcium sensing receptor |

| Cit3-

|

Citrate (anion) |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| GFR |

Glomerular filtration rate |

| HOL |

Hypophosphatemia of leprosy |

| hPTH |

Hyperparathyroidism |

| PHEX |

Phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases, X-linked |

| PO43-

|

Phosphate (anion) |

| PTH |

Parathyroid hormone |

| XLH |

X-linked hypophosphatemia |

| ATSDR |

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry |

References

- Shaw CA, Seneff S, Kette SD, Tomljenovic L, Oller JW, Davidson RM. Aluminum-induced entropy in biological systems: Implications for neurological disease. J Toxicol. 2014 Oct 2; 2014:491316. PMID: 25349607. [CrossRef]

- Marrack P, McKee AS, Munks MW. Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009 Apr; 9:287–93. PMID: 19247370. [CrossRef]

- Martin RB. The chemistry of aluminum as related to biology and medicine. Clin Chem. 1986 Oct 1; 32:1797–806. PMID: 3019589. [CrossRef]

- DeVoto E, Yokel RA. The biological speciation and toxicokinetics of aluminum. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Nov 1; 102:940–51. PMID: 9738208. [CrossRef]

- Harris WR, Wang Z, Hamada YZ. Competition between transferrin and the serum ligands citrate and phosphate for the binding of aluminum. Inorg Chem. 2003 Apr 16; 42:3262–73. PMID: 12739968. [CrossRef]

- Spurney RF, Pi M, Flannery P, Quarles LD. Aluminum is a weak agonist for the calcium-sensing receptor. Kidney Int. 1999 May; 55:1750–8. PMID: 10231437. [CrossRef]

- Siegel N, Haug A. Aluminum interaction with calmodulin: Evidence for altered structure and function from optical and enzymatic studies. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 1983 Apr 14; 744:36–45. PMID: 6299365. [CrossRef]

- Ondreicka R, Ginter E, Kortus J. Chronic toxicity of aluminium in rats and mice and its effects on phosphorous metabolism. Occup Environ Med. 1966 Oct 1; 23:305–12. PMID: 5926895. [CrossRef]

- Ondreicka RU, Kortus JO, Ginter EM. Aluminum, its absorption, distribution, and effects on phosphorus metabolism. In: Skoryna SC, Waldron-Edward D, editors. Intest. Absorpt. Met. Ions Trace Elem. Radionucl. Part II, New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1971.

- Burnatowska-Hledin M, Klein AM, Mayor GH. Effect of aluminum on the renal handling of phosphate in the rat. Am J Physiol - Ren Physiol. 1985 Jan 1; 17. PMID: 2982276.

- Shirley DG, Lote CJ. Renal handling of aluminium. Nephron Physiol. 2005 Sep 19; 101:99–103. PMID: 16174991. [CrossRef]

- Shaw KA. Prevalence and early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 and 8 years. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2025 Apr 17; 74:1–22. PMID: 40232988. [CrossRef]

- Yokel RA, McNamara PJ. Aluminium toxicokinetics: An updated MiniReview. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008 Apr 7; 88:159–67. PMID: 11322172. [CrossRef]

- Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? J R Soc Med. 1965 May; 58:295–300. PMID: 14283879. [CrossRef]

- Alfrey AC, LeGendre GR, Kaehny WD. The dialysis encephalopathy syndrome. Possible aluminum Intoxication. N Engl J Med. 1976 Jan 22; 294:184–8. PMID: 1244532. [CrossRef]

- Mayor GH, Keiser JA, Makdani D, Ku P. Aluminum absorption and distribution: effect of parathyroid hormone. Science. 1977 Sep 16; 197:1187–9. PMID: 897661. [CrossRef]

- Mayor GH, Keiser JA, Sanchez TV, Sprague SM, Hook JB. Factors affecting tissue aluminum concentration. Abstract. J Dial. 1978; 2:471–81. PMID: 374433. [CrossRef]

- Mayor GH, Sprague SM, Hourani MR, Sanchez TV. Parathyroid hormone-mediated aluminum deposition and egress in the rat. Kidney Int. 1980 Jan; 17:40–4. PMID: 7374019. [CrossRef]

- Alfrey AC, Hegg A, Craswell P. Metabolism and toxicity of aluminum in renal failure. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980 Jul; 33:1509–16. PMID: 7395774. [CrossRef]

- Cournot-Witmer G, Zingraff J, Plachot JJ. Aluminum localization in bone from hemodialyzed patients: Relationship to matrix mineralization. Kidney Int. 1981 Sep; 20:375–85. PMID: 7300127. [CrossRef]

- Mayor GH, Sprague SM, Sanchez TV. Determinants of tissue aluminum concentration. Am J Kidney Dis. 1981 Nov; 1:141–5. PMID: 7036718. [CrossRef]

- Pierides AM, Ward MK, Kerr DNS. Haemodialysis encephalopathy: Possible role of phosphate depletion. The Lancet. 1976 Jun 5; 307:1234–5. PMID: 58272. [CrossRef]

- Mayor GH, Burnatowska Hledin MA. Impaired renal function and aluminum metabolism. Fed Proc. 1983 Oct 1; 42:2979–83. PMID: 6617895.

- Burnatowska-Hledin MA, Kaiser L, Mayor GH. Aluminum, parathyroid hormone, and osteomalacia. Abstract. Spec Top Endocrinol Metab. 1983 Jan 1; 5:201–26. PMID: 6422572.

- Cannata JB, Junor BJR, Briggs JD, Fell GS, Beastall G. Effect of acute aluminium overload on calcium and parathyroid-hormone metabolism. The Lancet. 1983 Mar 5; 321:501–3. PMID: 6131212. [CrossRef]

- Morrissey J, Rothstein M, Mayor G, Slatopolsky E. Suppression of parathyroid hormone secretion by aluminum. Kidney Int. 1983; 23:699–704. PMID: 6308327. [CrossRef]

- Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1976.

- Huang X, Jiang Y, Xia W. FGF23 and phosphate wasting disorders. Bone Res. 2013 Jun 28; 1:120–32. PMID: 26273497. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, et al. Targeted ablation of FGF23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004 Feb 15; 113:561–8. PMID: 14966565. [CrossRef]

- Francis F, Hennig S, Korn B, Reinhardt R, de Jong P, Poustka A, et al. A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X–linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Nat Genet 1995 112. 1995; 11:130–6. PMID: 7550339. [CrossRef]

- Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, Lombardi M, Butters R, Kifor O, et al. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid and kidney: New insights into the physiology and pathophysiology of calcium metabolism. Nature. 1993 Dec 9; 366:575–80. PMID: 8255296. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Corte C, Fernández-Martín JL, Barreto S, Gómez C, Fernández-Coto T, Braga S, et al. Effect of aluminium load on parathyroid hormone synthesis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001 Apr 1; 16:742–5. PMID: 11274267. [CrossRef]

- Underhill FP, Peterman FI. Studies in the metabolism of aluminum. Am J Physiol-Leg Content. 1929 Sep 1; 90:40–51. [CrossRef]

- Lichtman MA, Miller DR, Freeman RB, Lockwood C, Abel V. Erythrocyte adenosine triphosphate depletion during hypophosphatemia in a uremic subject. Abstract. N Engl J Med. 1969 Jan 30; 280:240–4. PMID: 4236189. [CrossRef]

- King SW, Savory J, Wills MR. Aluminum toxicity in relation to kidney disorders. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1981 Jul; 11:337–42. PMID: 7023347.

- Andreoli SP, Bergstein JM, Sherrard DJ. Aluminum intoxication from aluminum-containing phosphate binders in children with azotemia not undergoing dialysis. Abstract. N Engl J Med. 1984 Apr 26; 310:1079–84. PMID: 6708989. [CrossRef]

- Dent CE, Winter CS. Osteomalacia due to phosphate depletion from excessive aluminum hydroxide ingestion. Br Med J. 1974 Mar 23; 1:551–2. PMID: 4817190. [CrossRef]

- Exley C, Mold MJ. The binding, transport and fate of aluminium in biological cells. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015 Apr 1; 30:90–5. PMID: 25498314. [CrossRef]

- Knochel JP. Hypophosphatemia. West J Med. 1981 Jan; 134:15–26. PMID: 7010790.

- Osis G, Webster KL, Harris AN, Lee HW, Chen C, Fang L, et al. Regulation of renal naDC1 expression and citrate excretion by NBCe1-a. Am J Physiol - Ren Physiol. 2019 Aug 1; 317:F489–501. PMID: 31188034. [CrossRef]

- Unwin RJ, Capasso G, Shirley DG. An overview of divalent cation and citrate handling by the kidney. Nephron - Physiol. 2004; 98:15–20. PMID: 15499218. [CrossRef]

- Hering-Smith KS, Hamm LL. Acidosis and citrate: Provocative interactions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Sep; 29:1720–50. PMID: 30370301. [CrossRef]

- Burnatowska-Hledin MA, Mayor GH, Lau K. Renal handling of aluminum in the rat: clearance and micropuncture studies. Https://DoiOrg/101152/Ajprenal19852492F192. 1985 Aug 1; 18. PMID: 4025553. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman JM, Assimos DG. Hypocitraturia: pathophysiology and medical management. Rev Urol. 2009; 11:134–44. PMID: 19918339.

- Nangliya VL, Sunder S, Sharma A, Ahuja L. Study of serum calcium and phosphorus level in autism spectrum disorder patients and Its correlation with severity of disease. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2022 Feb 25; 14:515-521.

- Afroz S, Siddiqi UR, Mahruba N, Shahjadi S, Begum S. Serum calcium and phosphate in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Bangladesh Soc Physiol. 2020 Dec 23; 15:72–7. [CrossRef]

- Lan J, Feng D, He X, Zhang Q, Zhang R. Basic properties and development status of aluminum adjuvants used for vaccines. Vaccines. 2024 Oct 18; 12:1187. PMID: 39460352. [CrossRef]

- Hémadi M, Miquel G, Kahn PH, El Hage Chahine JM. Aluminum exchange between citrate and human serum transferrin and interaction with transferrin receptor 1. Biochemistry. 2003 Mar 18; 42:3120–30. PMID: 12627980. [CrossRef]

- Shirley DG, Walter MF, Walter SJ, Thewles A, Lote CJ. Renal aluminium handling in the rat: A micropuncture assessment. Clin Sci. 2004 Aug; 107:159–65. PMID: 15053741. [CrossRef]

- Bergwitz C, Jüppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med. 2010 Feb 18; 61:91–104. PMID: 20059333. [CrossRef]

- Payne RB. Renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate (TmP/GFR): Indications and interpretation. Ann Clin Biochem. 1998 Mar; 35:201–6. PMID: 9547891. [CrossRef]

- D’haese PC, Van De Vyver FL, De Wolff FA, De Broe E. Measurement of aluminum in serum, blood, urine, and tissues of chronic hemodialyzed patients by use of electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. Clin Chem. 1985 Jan; 1:24–9. PMID: 3965215.

- Carrel L, Brown CJ. When the Lyon(ized chromosome) roars: ongoing expression from an inactive X chromosome. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2017 Nov 5; 372:1–15. PMID: 28947654. [CrossRef]

- Migeon BR. X-linked diseases: susceptible females. Genet Med. 2020 Jul 1; 22:1156–74. PMID: 32284538. [CrossRef]

- Alos N, Ecarot B. Downregulation of osteoblast Phex expression by PTH. Bone. 2005 Oct; 37:589–98. PMID: 16084134. [CrossRef]

- Uno JK, Kolek OI, Hines ER, Xu H, Timmermann BN, Kiela PR, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor α in down-regulation of osteoblast PHEX gene expression in experimental murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006 Aug; 131:497–509. PMID: 16890604. [CrossRef]

- Campbell A, Yang EY, Tsai-Turton M, Bondy SC. Pro-inflammatory effects of aluminum in human glioblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2002 Apr 12; 933:60–5. PMID: 11929636. [CrossRef]

- Denker, Bradley M., Chertow, Glenn M., Owens, Wiilliam F., Jr. Chapter 57, Hemodialysis. The Kidney, vol. 2. 6th ed., Philadlphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000., p. 2419–20.

- Borrego Utiel FJ, Herrera Contreras I, Merino García E, Moriana Domínguez C, Ocaña Pérez E, García Cortés MJ. Hypocitraturia is present when renal function is impaired in diverse nephropathies and is not related with serum bicarbonate levels. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022 Jun; 54:1261–9. [CrossRef]

- Whitney DG, Schmidt M, Bell S, Morgenstern H, Hirth RA. Incidence rate of advanced chronic kidney disease among privately insured adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Feb 27; 12:235–43. PMID: 32161503. [CrossRef]

- Clothier J, Absoud M. Autism spectrum disorder and kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021 Oct 1; 36:2987–95. PMID: 33340339. [CrossRef]

- Samy El-Farsy M, Elhossiny RM, Samir N, Elgendy D, Wafeeq Abdelaziz A. Association of autism spectrum disorder with pediatric kidney disease. Al-Azhar J Pediatr. 2024 Apr 1; 27:3881–6. [CrossRef]

- Alexander J, Nagi D. Isolated hypophosphataemia as an early marker of primary hyperparathyroidism. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2021 May 13; 2021:1–5. PMID: 34152284. [CrossRef]

- Lanske B, Razzaque MS. Molecular interactions of FGF23 and PTH in phosphate regulation. Kidney Int. 2014 Jan 1; 86:1072–4. PMID: 25427080. [CrossRef]

- Murphy H, Patrick J, Báez-Irizarry E, Lacassie Y, Gómez R, Vargas A, et al. Neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism caused by homozygous mutation in CASR: A rare cause of life-threatening hypercalcemia. Eur J Med Genet. 2016 Feb 6; 59:227–31. PMID: 26855056. [CrossRef]

- Torres PAU, De Brauwere DP. Three feedback loops precisely regulating serum phosphate concentration. Kidney Int. 2011 Sep 1; 80:443–5. PMID: 21841832. [CrossRef]

- Alexander RT, Dimke H. Effects of parathyroid hormone on renal tubular calcium and phosphate handling. Acta Physiol. 2023 Mar 9; 238:1–16. PMID: 36894509. [CrossRef]

- George J, Acharya SV, Bandgar TR, Menon PS, Shah NS. Primary hyperparathyroidism in children and adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2010 Feb 20; 77:175–8. PMID: 20091382. [CrossRef]

- Lourida I, Thompson-Coon J, Dickens CM, Soni M, Kuźma E, Kos K, et al. Parathyroid hormone, cognitive function and dementia: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2015 May 1; 10:e0127574. PMID: 26010883. [CrossRef]

- Ohata Y, Ishihara Y. Pathogenic variants of the PHEX gene. Endocrines. 2022 Aug 8; 3:498–511. [CrossRef]

- Ariceta G, Beck-Nielsen SS, Boot AM, Brandi ML, Briot K, de Lucas Collantes C, et al. The International X-Linked Hypophosphatemia (XLH) Registry: First interim analysis of baseline demographic, genetic and clinical data. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023 Dec 1; 18:1–17. PMID: 37752558. [CrossRef]

- Whyte MP, Schranck FW, Armamento-Villareal R. X-linked hypophosphatemia: a search for gender, race, anticipation, or parent of origin effects on disease expression in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 Nov 1; 81:4075–80. PMID: 8923863. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rubio E, Gil-Peña H, Chocron S, Madariaga L, de la Cerda-Ojeda F, Fernández-Fernández M, et al. Phenotypic characterization of X-linked hypophosphatemia in pediatric Spanish population. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021 Dec 1; 16:1–12. PMID: 33639975. [CrossRef]

- Hardy DC, Murphy WA, Siegel BA, Reid IR, Whyte MP. X-linked hypophosphatemia in adults: Prevalence of skeletal radiographic and scintigraphic features. Abstract. Radiology. 1989 May 1; 171:403–14. PMID: 2539609. [CrossRef]

- Joel V, Hans H, Dirk D. Autism and X-linked hypophosphatemia: A possible association? Indian J Hum Genet. 2010 Jan 1; 16:36–8. PMID: 20838491. [CrossRef]

- Silva SRB, Tempone AJ, Silva TP, Costa MRSN, Pereira GMB, Lara FA, et al. Mycobacterium leprae downregulates the expression of PHEX in Schwann cells and osteoblasts. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010 Aug; 105:627–32. PMID: 20835608. [CrossRef]

- Boiça Silva SR, Illarramendi X, Tempone AJ, Silva PHL, Nery JAC, Monteiro AMV, et al. Downregulation of PHEX in multibacillary leprosy patients: Observational cross-sectional study. J Transl Med. 2015 Sep; 13:1–8. PMID: 26362198. [CrossRef]

- De Paula HL, De Souza CDF, Silva SR, Martins-Filho PRS, Barreto JG, Gurgel RQ, et al. Risk factors for physical disability in patients with leprosy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 1; 155:1120–8. PMID: 31389998. [CrossRef]

- Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017 Jun 1; 18:153–65. PMID: 28516265. [CrossRef]

- Bikle DD. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem Biol. 2014 Mar 20; 21:319–29. PMID: 24529992. [CrossRef]

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul 1; 96:1911–30. PMID: 21646368. [CrossRef]

- Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, Gillespie C, Hollis BW, Looker AC, et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Jul 1; 76:187–92. PMID: 12081833. [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto S. Phosphate metabolism and vitamin D. BoneKEy Rep. 2014 Feb 5; 3:4–597. PMID: 24605214. [CrossRef]

- Cannell JJ. Autism and vitamin D. Med Hypotheses. 2007 Aug 15; 70:750–9. PMID: 17920208. [CrossRef]

- Kočovská E, Fernell E, Billstedt E, Minnis H, Gillberg C. Vitamin D and autism: Clinical review. Res Dev Disabil. 2012 Sep 1; 33:1541–50. PMID: 22522213. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa GA, AL-Ayadhi LY. Reduced serum concentrations of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in children with autism: Relation to autoimmunity. J Neuroinflammation. 2012 Dec; 9:686. PMID: 22898564. [CrossRef]

- Grant WB, Cannell JJ. Autism prevalence in the United States with respect to solar UV-B doses: An ecological study. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013 Jan 1; 5:159–64. PMID: 24494049. [CrossRef]

- Cannell JJ, Grant WB. What is the role of vitamin D in autism? Dermatoendocrinol. 2013 Jan 1; 5:199–204. PMID: 24494055. [CrossRef]

- Cannell JJ. Vitamin D and autism, what’s new? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017 Jun 1; 18:183–93. PMID: 28217829. [CrossRef]

- Bagó AG, Palkovits M, Usdin TB, Seress L, Dobolyi A. Evidence for the expression of parathyroid hormone 2 receptor in the human brainstem. Ideggyogyaszati Szle. 2008 Mar 30; 61:123–6. PMID: 18459453.

- Bagó AG, Dimitrov E, Saunders R, Seress L, Palkovits M, Usdin TB, et al. Parathyroid hormone 2 receptor and its endogenous ligand tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues are concentrated in endocrine, viscerosensory and auditory brain regions in macaque and human. Neuroscience. 2009 May 3; 162:128–47. PMID: 19401215. [CrossRef]

- Baizer JS. Functional and neuropathological evidence for a role of the brainstem in autism. Front Integr Neurosci. 2021 Oct 20; 15:70–84. PMID: 34744648. [CrossRef]

- Seif A, Shea C, Schmid S, Stevenson RA. A Systematic review of brainstem contributions to autism spectrum disorder. Front Integr Neurosci. 2021 Nov 1; 15:760116. PMID: 34790102. [CrossRef]

- Herbert MR. Autism: The centrality of active pathophysiology and the shift from static to chronic dynamic encephalopathy. Autism Oxidative Stress Inflamm. Immune Abnorm., CRC Press; 2010., p. 343-387.

- Mcginnis WR, Audhya T, Edelson SM. Proposed toxic and hypoxic impairment of a brainstem locus in autism. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2013 Dec 11; 10:6955–7000. PMID: 24336025. [CrossRef]

- Mold M, Umar D, King A, Exley C. Aluminium in brain tissue in autism. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2018 Mar 1; 46:76–82. PMID: 29413113. [CrossRef]

- Exley C, Clarkson E. Aluminium in human brain tissue from donors without neurodegenerative disease: A comparison with Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and autism. Sci Rep. 2020 May 8; 10:1–7. PMID: 32385326. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Xu L, Wu Y, Shen H, Lin Z, Fang Y, et al. Parathyroid hormone promotes human umbilical vein endothelial cell migration and proliferation through Orai1-mediated calcium signaling. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Mar 16; 9. PMID: 35369318. [CrossRef]

- Areco VA, Kohan R, Talamoni G, Tolosa De Talamoni NG, Peralta López ME. Intestinal Ca2+ absorption revisited: A molecular and clinical approach. World J Gastroenterolgy. 2020 Jun 28; 26:3344–64. [CrossRef]

- Moccia F, Berra-Romani R, Tanzi F. Update on vascular endothelial Ca2+ signalling [sic]: A tale of ion channels, pumps and transporters. World J Biol Chem. 2012; 3:127. PMID: 22905291. [CrossRef]

- Van Abel M, Hoenderop JGJ, Bindels RJM. The epithelial calcium channels TRPV5 and TRPV6: Regulation and implications for disease. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005 Apr 4; 371:295–306. PMID: 15747113. [CrossRef]

- Yelshanskaya MV, Nadezhdin KD, Kurnikova MG, Sobolevsky AI. Structure and function of the calcium-selective TRP channel TRPV6. J Physiol. 2021 May 1; 599:2673–97. PMID: 32073143. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs G, Montalbetti N, Franz MC, Graeter S, Simonin A, Hediger MA. Human TRPV5 and TRPV6: Key players in cadmium and zinc toxicity. Cell Calcium. 2013 Oct 1; 54:276–86. PMID: 23968883. [CrossRef]