1. Introduction

Conducting polymers are utilized in many technologies including energy storage, optoelectronics, and sensing due to their tunable electrical conductivity and electrochemical properties.[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT: PSS) is benchmark material in this class, due for its high stability, processability in aqueous dispersions, excellent electrical and mechanical features.[

8,

9] Especially over the past two decades, PEDOT:PSS has been widely applied in coatings, transparent electrodes, sensors, and as an electrode material in electrochemical capacitors which are often referred to as supercapacitors (SCs).[

10,

11,

12]

PEDOT:PSS is a mixed ion-electron conductor, where PEDOT chains provide electronic conductivity and PSS chains provides charge neutrality and ionic transport. This structure enables rapid redox-driven charge storage, making PEDOT:PSS ideal for high-performance SC electrodes.[

13,

14] Therefore, researchers have utilized its solution processability and mechanical flexibility to develop SCs in various configurations, including symmetric,[

15] asymmetric,[

16] microscale,[

17] and hybrid designs.[

18] For instance, a symmetric SC with PEDOT: Nafion achieve ~98.7% capacitance retention after 1,000 cycles.[

19] Asymmetric designs, such as MnO₂/PEDOT on activated carbon cloth paired with carbon, expanded the voltage window, enhancing energy density without compromising power.[

20] Micro-SCs printed with AC/PEDOT:PSS composites exhibit areal capacitances of ~29.5 mF cm⁻², nearly double that of carbon-only devices (~15.7 mF cm⁻²), with ~85% retention after 5,000 cycles.[

21] Flexible formats, such as reduced graphene oxide (rGO)–PEDOT:PSS films and carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced composites, offer high areal capacitance, low internal resistance, and robust cycle life.[

22,

23] These advancements highlight PEDOT:PSS composite as a versatile platform, tunable with carbon nanomaterials, metal oxides, or secondary dopants to optimize power, energy, flexibility, and durability.

Despite progress in the engineering PEDOT-based SCs, the synthesis of PEDOT:PSS remains a challenge for sustainable chemistry. Conventional polymerization of EDOT uses toxic and corrosive reagents like FeCl₃ [

24] generating metal waste [

25,

26] or sophisticated electrochemical setups that conflict with sustainable chemistry principles.[

27] Moreover, commercial PEDOT:PSS production involves separate synthesis of PEDOT and PSS, followed by mixing, making it a non-straightforward multi-step process.[

28,

29]

Photopolymerization offers a more sustainable alternative, leveraging light to initiate reactions without metal catalysts.[

30,

31,

32] Benefits include energy efficiency, elimination of toxic and corrosive oxidants, spatiotemporal control (key for 3D printing applications),[

33] and intrinsic doping.[

34,

35] Our group previously demonstrated photochemical oxidative polymerization of EDOT under both UV and visible light using an organic photoinitiator in ethanol,[

36] light-driven copolymerization reactions of EDOT with

ε−caprolactone[

37] and 9-ethylcarbazole monomers[

38] producing a conductive scaffold and a black-to-transmissive electrochromic copolymer, respectively. Very recently, we reported the photochemical

in situ synthesis of PEDOT-coated polydopamine as a SC electrode material with improved ion transport and thus, better capacitive performance compared to previously obtained PEDOT-based SC electrode materials.[

39]

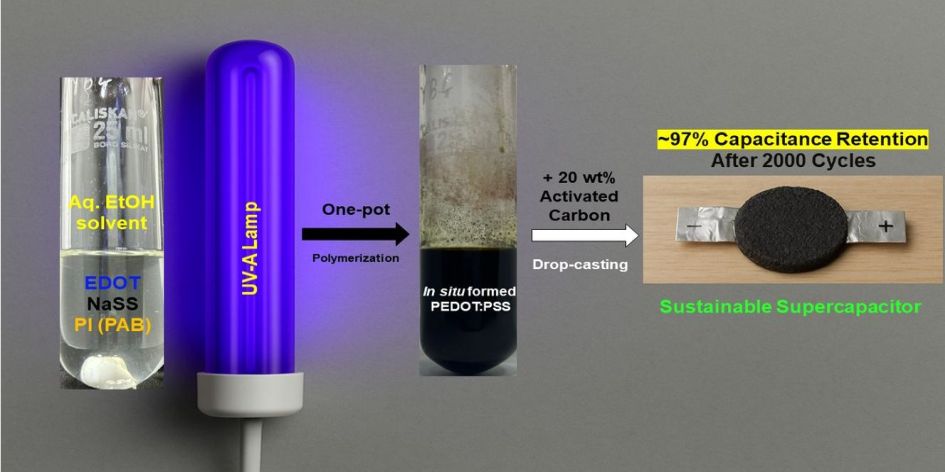

Building on these advances, the present work introduces a straightforward one-pot photopolymerization method for the synthesis of PEDOT: PSS, by simultaneously polymerizing EDOT and NaSS (sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) monomers using phenacyl bromide (PAB) under UV-A light in a green solvent system. While hybrid systems have been reported that use conventional chemical oxidants (e.g., FeCl

3 for EDOT polymerization in parallel with a separate photopolymerization mechanism for a functionalized PSS scaffold[

40], a fully light-driven, metal-free synthesis from simple monomers remains elusive. The primary objective of this work is to demonstrate that this sustainable synthesis route yields a high-quality material capable of delivering exceptional long-term electrochemical performance, as measured by supercapacitor cycling durability. The success of this approach is crucial for establishing green chemistry pathways for future high-performance, sustainable energy storage components.

3. Results and Discussion

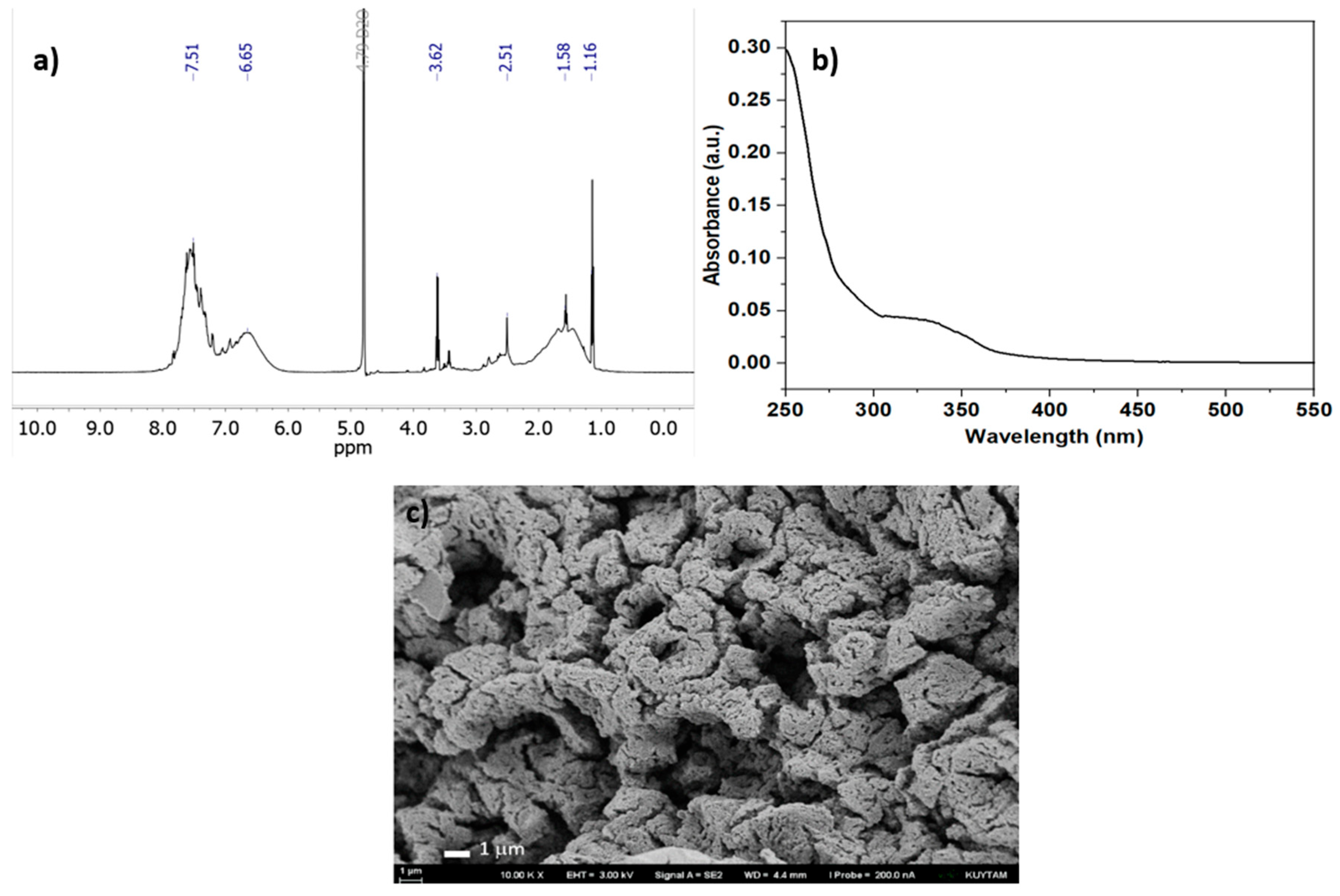

3.1.1. Photopolymerization of NaSS

As a control experiment, sodium 4-styrenesulfonate (NaSS) was exposed to UV-A light (~365 nm) in the presence of phenacyl bromide (PAB) initiator (with no EDOT added), resulting in successful homopolymerization of NaSS into poly (sodiumstyrene sulfonate) (PSS). As our group previously demonstrated the capability of PAB to initiate the polymerization of styrene under UV-A light, mechanistically, PAB undergoes Norrish Type I photolysis, generating radical species (bromine and phenacyl radicals) that add to the vinyl group of NaSS and propagate a chain-growth polymerization to form the PSS backbone.[

44] Consistent with this radical-mediated process, the reaction yielded a water-soluble beige-colored PSS that was confirmed by

1H NMR spectroscopy in D

2O (

Figure 2a), which showed the emergence of broad aromatic proton signals in the ~6-7.5 ppm region and the disappearance of the monomer’s vinylic proton peaks (~5.2–5.8 ppm), indicating consumption of double bonds belonging to NaSS monomer. UV–Vis analysis of the product further demonstrated only UV absorptions (with a characteristic benzene-ring band observed around 250 nm), and no significant visible-light absorption (

Figure 2b). Furthermore, GPC analysis indicated the presence of high molecular weight PSS species (

Mn = 285 kDa) with a dispersity of

Ɖ= 1.66 (

Figure S3). According to SEM micrograph (

Figure 2c), PSS shows a highly porous and irregular surface morphology. The polymer is composed of interconnected granular and sponge-like aggregates, with numerous open voids and channel-like features. The absence of well-defined crystalline features is consistent with the amorphous nature of PSS, as previously confirmed by powder X-ray diffractograms in the literature.[

45] Importantly, such a morphology could enhance ion-accessible surface area, a property relevant when PSS is used as a polyelectrolyte dopant in conductive polymer complexes such as PEDOT:PSS.

3.1.1. Light-Induced One-Pot Synthesis and Characterization of PEDOT:PSS

Homopolymerization of NaSS experiment confirms that NaSS is indeed photochemically reactive under the same UV-A/PAB conditions, supporting the one-pot PEDOT:PSS synthesis pathway as the homopolymerization of EDOT under the same conditions was previously demonstrated by our group.[

36] In the main reaction, NaSS can undergo

in situ radical polymerization to form PSS concurrently alongside the photooxidative polymerization of EDOT initiated by bromine radicals, thereby providing a readily-formed polyanionic PSS matrix that both dopes and stabilizes the growing PEDOT chains.

Light-induced polymerization of EDOT in the presence of NaSS and PAB was successful in yielding PEDOT:PSS without any additional chemical oxidant. The reaction mixture’s rapid color change from colorless to first dark blue and then to dark green and finally to black under UV-A irradiation confirmed the quick formation of conjugated polymer chains. In contrast, no polymer was formed when the mixture was kept in the dark, underscoring that photoactivation of PAB is essential for the polymerization.

Based on our previous findings of laser-flash photolysis,[

39] we propose that the photogenerated bromine radicals abstract an electron to produce radical cations on EDOT, which then couple to form PEDOT chains in step-growth fashion. Simultaneously, NaSS monomers can polymerize through the initiation of both phenacyl and bromine radicals, forming PSS chains or attach as side-groups, effectively and

in situ doping the PEDOT with sulfonate anions. The overall result is a doped PEDOT:PSS network formed in one pot (

Scheme 1).

This methodology offers several noteworthy advantages such as (i) Mild Conditions: The polymerization proceeds at room temperature under light, avoiding the heating often required in chemical oxidations. (ii) Green Solvent: Ethanol/Water mixture is used as the medium, which is an environmentally benign solvent system. (iii) No Hazardous Oxidants: Traditional oxidants like FeCl₃ or persulfates are replaced by an organic photoinitiator, simplifying purification since the major byproducts is non-toxic and highly soluble acetophenone that can easily be removed during precipitation. (iv) In Situ Doping: Because the PSS is synthesized during polymerization, the resulting PEDOT is obtained directly in its doped state (with PSS⁻ counter anions), eliminating the need for a separate synthesis/doping step to achieve conductivity. Overall, all these features make this photopolymerization method a compelling new approach for PEDOT:PSS.

Table 1.

Sustainability-focused comparison of PEDOT:PSS synthesis methods.

Table 1.

Sustainability-focused comparison of PEDOT:PSS synthesis methods.

| Method |

Oxidant / Initiator |

Solvent System |

Byproducts & Waste |

Process Features & Sustainability Impact |

| This Work (Photochemical) |

Organic Photoinitiator (Phenacyl Bromide) |

Benign (Ethanol/Water) |

Acetophenone (Non-toxic, readily removed) |

One-Pot, in situ Doping: Eliminates need for separate blending. Metal-free process avoids hazardous waste. Enables spatiotemporal control for 3D printing. |

| Conventional Chemical |

Corrosive Oxidants (e.g., FeCl₃, persulfates) |

Aqueous / Acidic |

Generates metal waste/corrosive byproducts. |

Multi-Step: Often requires separate synthesis and blending of PEDOT and PSS. Product requires extensive purification to remove metal contaminants. |

| Electrochemical |

Applied Potential (Electricity) |

Electrolyte Solution |

No major chemical waste |

Setup-Intensive: Requires sophisticated electrochemical setups and a conductive substrate. Not scalable for bulk ink/powder synthesis. |

Excess of the photoinitiator (PAB) (compared to EDOT and NaSS) was necessary for a significant NaSS conversion since equimolar amounts of PAB resulted in unreacted monomer (NaSS) present in PEDOT:PSS that was confirmed by

1H NMR spectroscopy (

Figure S4). The photochemically obtained PEDOT:PSS having a gravimetric monomer conversion of 42%, is a dark-blue to black colored, powdery solid that disperses well in water due to the PSS content (

Figure S5).

The GPC traces indicated a number-average molecular weight

Mn = 2300 g/mol and a relatively narrow molecular weight distribution with a dispersity index of

Ɖ= 1.4 (

Figure S6), signifying the detection of PEDOT species more than PSS. While GPC revealed a high apparent molecular weight for the homopolymer PSS (

Figure S3), whereas the PEDOT:PSS complex displayed a substantially lower molecular weight. We attribute this difference to both chemistry and GPC hydrodynamics. First, radical homopolymerization of NaSS under UV-A/PAB yields high-molecular-weight PSS, while photochemical oxidative coupling of EDOT intrinsically produces short PEDOT chains (limited by chain-transfer/termination), so the PEDOT fraction is genuinely low-

Mw. Second, upon complexation the PEDOT:PSS forms compact ionic nanocomplexes; relative to free PSS of the same mass, exhibiting smaller hydrodynamic volume and stronger column interactions, causing later elution and underestimation of

Mw in PMMA-calibrated GPC.

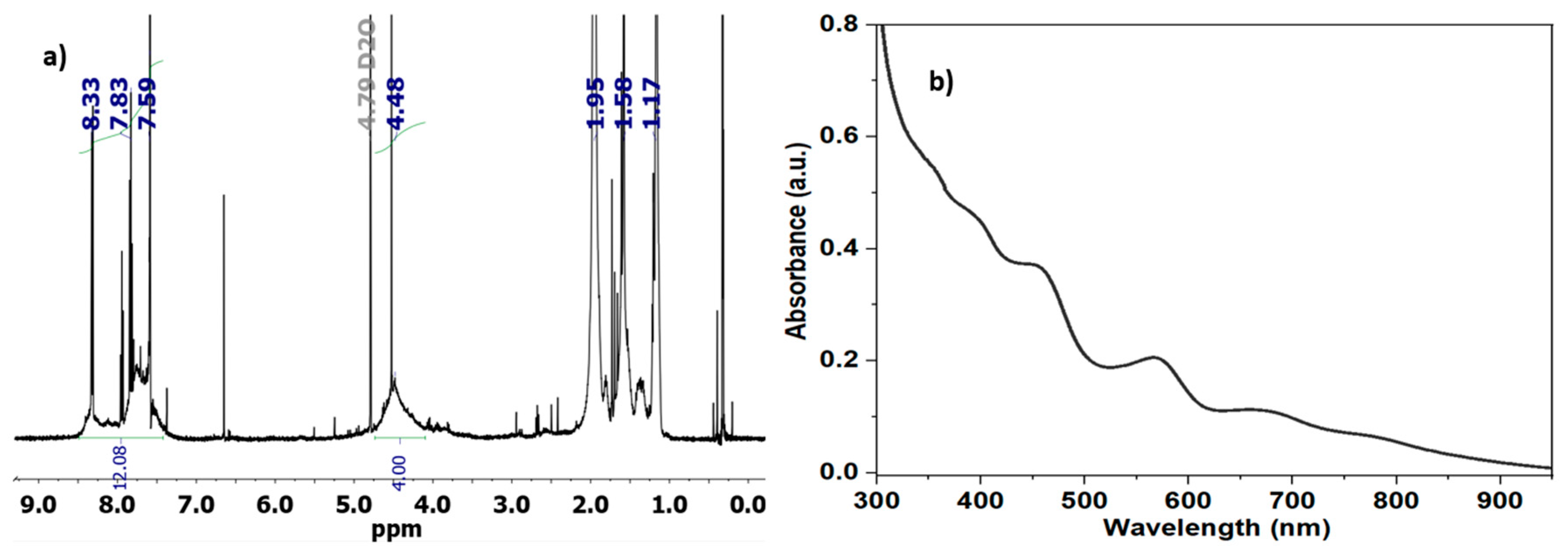

1H NMR spectrum of the photochemically obtained PEDOT:PSS (

Figure 3a) revealed broadening of peaks corresponding to the ethylenedioxy protons (-O-CH

2-) of the PEDOT repeating unit at ~4.2-4.4 ppm, as well as aromatic signals in the 7.5–8.3 ppm range attributed to the hydrogens of the PSS dopant. The absence of peaks for the monomers (EDOT’s vinyl protons around 6.3 ppm and NaSS styrenic protons around 5.5 ppm) indicates successful polymerization. Semi-quantitative integration of the PSS aromatic and PEDOT ethylenedioxy regions (4 H vs 4 H) yields a PEDOT:PSS molar ratio on the order of 1:3, similar to commercially available charge-balanced PEDOT:PSS solution sold under the name Clevios™ P VP AI 4083.[

46]

13C NMR signals are often undetectable in PEDOT:PSS solution, making solid-state CP/MAS the standard method for structural characterization.[

47] In this context, the solution-state ¹³C NMR spectrum obtained in our study provides rare complementary evidence of both PEDOT and PSS backbones, even though the resonances are broad, consistent with the conductive, partially doped state of the polymer. ¹³C NMR spectrum of the photopolymerized PEDOT:PSS (

Figure S7) displayed broad resonances centered at δ ≈ 128 ppm, corresponding to the aromatic carbons of the PSS matrix, along with distinct signals at δ ≈ 65–70 ppm assigned to the ethylenedioxy groups (–O–CH₂–) of PEDOT. Importantly, no vinyl carbon signals were observed in the δ 120–140 ppm region, confirming complete consumption of EDOT and NaSS monomers. The broad nature of the peaks is characteristic of conducting polymers in the doped state, where delocalized polarons shorten relaxation times.[

48] These observations verify the successful

in situ photopolymerization of EDOT and NaSS.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed (

Figure S8) to investigate the surface chemistry and elemental composition of the PEDOT:PSS powder and compare the PEDOT:PSS ratio with the one calculated from NMR spectrum. The XPS survey scan confirmed the presence of the three primary elements expected for a PEDOT:PSS blend: carbon (C 1s), oxygen (O 1s), and sulfur (S 2p). The quantitative analysis of the survey scan, showed a high carbon content (71.49%) and a significant presence of oxygen (19.16%) and sulfur (5.67%). The analysis also detected minor amounts of sodium (Na 1s) (3.04%) and bromine (Br 3p) (0.63%). While Na is present in most of the PEDOT:PSS as residual,[

49] bromine likely remains as a residual impurity from the oxidative polymerization of EDOT, where bromide salts are present as counter-ions to positively charged PEDOT species. To determine the molar ratio of PEDOT to PSS, a high-resolution scan of the S 2p core level was conducted. The spectrum was successfully deconvoluted into two distinct doublets, corresponding to two different chemical environments for sulfur (

Figure S9). A doublet with the S 2p

3/2 peak centered at a lower binding energy (~162 eV) was assigned to the sulfur atoms in the thiophene ring of the PEDOT component. This low binding energy is characteristic of non-oxidized, aromatic sulfur [

50] A second doublet with the S 2p

3/2 peak at a higher binding energy (~166 eV) was assigned to the highly oxidized sulfur atoms in the sulfonate group (−SO

3−) of the PSS component. The integral areas of these two doublets were used to quantify the relative abundance of each polymer on the powder’s surface. The analysis revealed that the PEDOT peak contributed 23.4% and the PSS peak contributed 76.6% to the total S 2p signal area, corresponding to a surface molar ratio of PEDOT:PSS = 1:3.2. This result is in good agreement with the ratio determined by NMR analysis (1:3), though the slight difference might be due to the surface-sensitive nature of XPS compared to the bulk analysis of NMR.

UV-Vis absorption spectrum measured for PEDOT:PSS in water displayed a peak between 600-900 nm characteristic of doped PEDOT (

Figure 3b). This broad absorption extending from the visible into the near-infrared region is typical for highly conjugated polymer chains in a doped (conductive) state. The similarity of this spectrum to commercial PEDOT:PSS dispersions further confirms the successful

in situ photopolymerization of EDOT and NaSS.[

51]

In the IR data of the photochemically obtained PEDOT:PSS (

Figure S10), the combination of strong SO₃⁻ bands (PSS) near 1180 cm

−1 with the C–O–C (ethylenedioxy) near 1200 cm

−1 and thiophene signature peaks at 700-900 cm

−1 region verifies the formation of the PEDOT:PSS.[

52] The broadened, intense absorption in the 1200–1500 cm⁻¹ region is consistent with doped PEDOT (polaronic character) aligning with the UV–Vis tail into the visible–NIR. Overall, the IR data corroborate successful one-pot photopolymerization of EDOT and NaSS.

The wettability of the electrode surfaces was assessed by water contact angle (WCA) measurements (

Figure S11). The pristine PEDOT:PSS electrode exhibited a low contact angle of 21°, indicative of its high hydrophilicity, which can be attributed to the presence of sulfonate groups in PSS that promote strong interactions with water. Upon incorporation of 20 wt% activated carbon (PEDOT:PSS/AC composite), the contact angle increased slightly to 26°, reflecting a modest reduction in hydrophilicity due to the relatively hydrophobic nature of carbon surfaces. Nevertheless, both values fall within the hydrophilic regime ensuring effective electrolyte wetting and facilitating ion transport at the electrode/electrolyte interface.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveals the nanoscale morphology of the photochemically synthesized PEDOT:PSS (

Figure 4a,b). The image displays a heterogeneous distribution of PEDOT-rich domains embedded within the PSS matrix. The darker, higher-contrast regions correspond to the π-conjugated PEDOT backbone, whereas the lighter, diffuse areas represent the amorphous and insulating PSS component. The observed morphology suggests the formation of interconnected PEDOT clusters with sizes ranging between approximately 50–200 nm, which are uniformly distributed throughout the sample. Such a nanophase-separated structure is characteristic of PEDOT:PSS[

53] and plays a crucial role in its electrical properties: the percolated PEDOT domains facilitate charge transport, while PSS ensures colloidal stability and film formation. This nanoscale morphology is advantageous for applications in energy storage, as it maximizes interfacial contact, improves charge mobility, and enhances electrochemical accessibility.[

54] The absence of large aggregates or phase segregation further supports that photopolymerization yields a homogeneous polymer network, which is expected to contribute to the improved electrochemical stability.

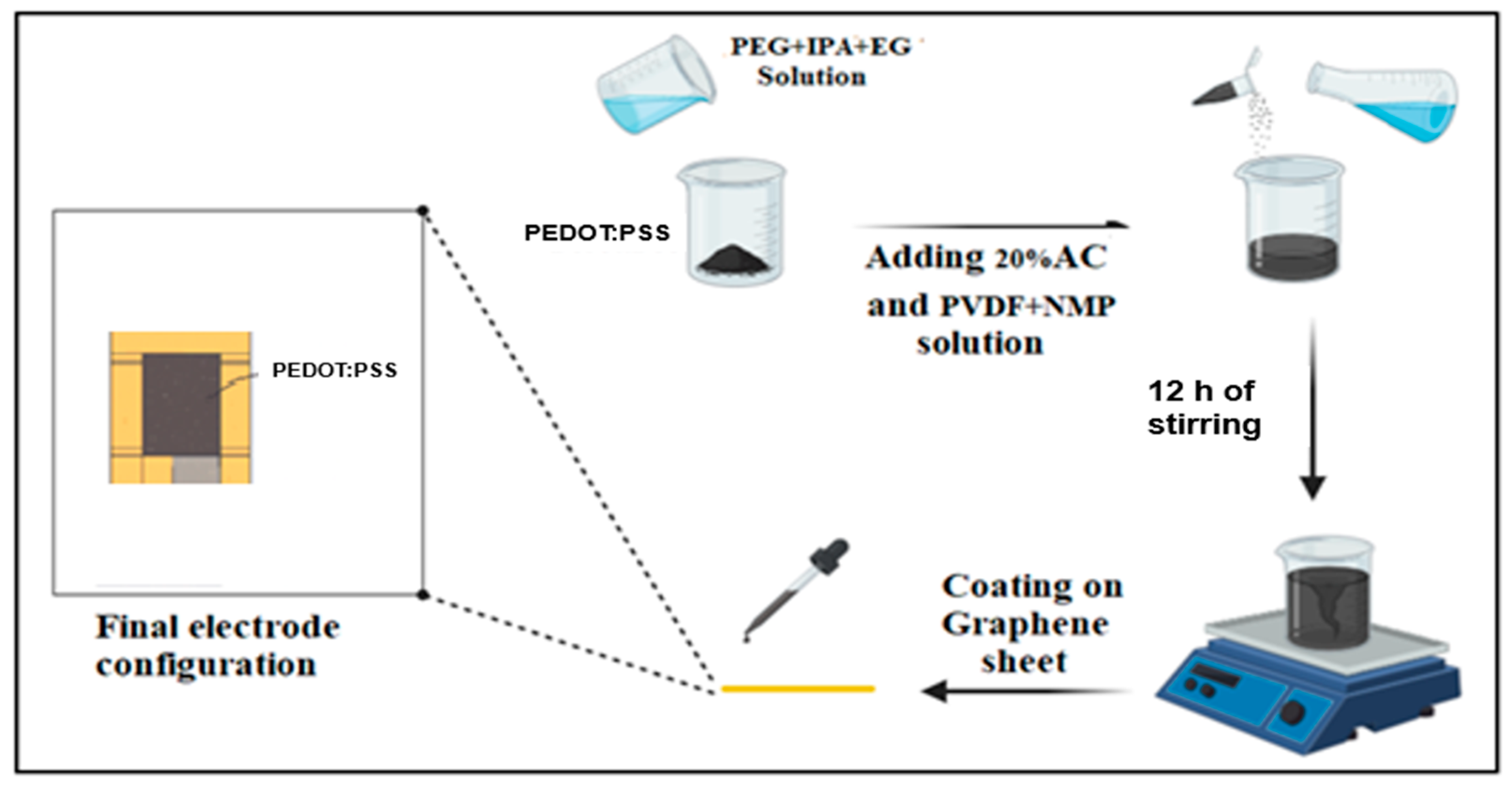

We added 20 wt% activated carbon to the photochemically prepared PEDOT:PSS to exploit the complementary charge-storage mechanisms: the carbon contributes large double-layer capacitance from its high surface area, whereas PEDOT:PSS supplies electronic conductivity and pseudocapacitance. This hybridization is well-known to balance surface-driven and redox-driven storages, yielding higher specific capacitance and better cycling stability than pristine PEDOT:PSS in electrical storage applications.[

13] Surface area of AC used in this experiment was calculated using BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) testing using the gas sorption data acquisition and reduction and calculated as 794 g/m

2 confirming the high porosity and suitability of AC as an electrochemical double-layer charge storage component (

Figure S12). The morphology of the photochemically obtained PEDOT:PSS and its combination with 20 wt% activated carbon (AC) (PEDOT: PSS/AC) was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (

Figure 5a,b).

The SEM micrograph of pristine photopolymerized PEDOT:PSS (

Figure 5a) reveals a relatively smooth and compact granular surface, with polymer domains forming a continuous film but displaying limited porosity. Such morphology is characteristic of pristine PEDOT:PSS, where PEDOT-rich grains are embedded within a PSS-rich matrix, yielding a dense structure with modest surface area.[

55] In contrast, the PEDOT:PSS composite containing 20 wt% activated carbon (PEDOT:PSS/AC) exhibits a distinctly rougher and more heterogeneous texture, with numerous voids, and particle-like features visible across the surface (

Figure 5b). The AC particles are well integrated within the polymer matrix, creating an interconnected porous network. This microstructure is expected to increase electrolyte accessibility and ion diffusion pathways, while PEDOT:PSS acts as a conductive binder that electrically bridges the carbon particles. Overall, SEM analysis confirms that incorporation of AC transforms the morphology from a compact polymer film into a highly porous, composite network, a change that should theoretically result in improved electrochemical performance.

Electrical conductivity measurements on pressed pellets of the doped polymer revealed a remarkable electrical conductivity of 323.7 S/cm for the PEG–IPA–EG-treated, photochemically synthesized PEDOT:PSS. This improvement arises from the synergistic influence of PSS, the mixed solvent system (PEG, EG and IPA) and the advantages of photopolymerization under mild conditions. In the PEDOT:PSS composite, PSS acts as both a polyanionic dopant and a structural template, stabilizing oxidized PEDOT chains and facilitating extended π-conjugation. The PEG–IPA–EG post-treatment further reorganizes the microstructure by partially removing or redistributing the insulating PSS phase, enhancing phase separation and promoting π–π stacking among PEDOT-rich domains. Additionally, PEG assists in maintaining film flexibility and suppressing crack formation, while EG and IPA improve chain alignment and carrier mobility. Together with the defect-minimizing nature of photopolymerization, these effects yield a highly interconnected conductive network, explaining the over two orders of magnitude increase in conductivity compared to pristine PEDOT. Notably, when 20 wt% activated carbon (AC) was incorporated, the conductivity dramatically increased to 2623 S/cm, owing to the formation of enhanced interfacial charge transfer between PEDOT chains and the graphitic AC network.

3.2.1. Electrochemical Behavior of PEDOT:PSS and PEDOT:PSS/AC Electrodes

Prior to the incorporation of activated carbon (AC), the pristine PEDOT:PSS-based solution comprising PEG, EG, IPA, and PVDF/NMP was subjected to electrochemical analysis to establish a baseline performance profile. This preliminary evaluation was critical to understand the intrinsic electrochemical behavior of the binder–polymer matrix in the absence of electrochemically active fillers. Establishing this reference performance allowed for a more accurate assessment of the functional role and performance enhancement contributed by each additive.

Initial electrochemical measurements were conducted using a three-electrode configuration connected to a potentiostat system. As a first step, pristine PEDOT:PSS was tested alone to establish its baseline electrochemical response.

Figure 6a presents the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the pristine electrode material without activated carbon, recorded at scan rates ranging from 25 to 200 mV/s. The CV profiles have shapes that deviate from ideal capacitive behavior, indicating a combination of electric double-layer capacitance and pseudocapacitive contributions from the PEDOT:PSS matrix. As the scan rate increases, the current response also increases proportionally, which is a typical signature of good electrochemical reversibility and surface-limited charge storage.

Nevertheless, the anodic current response is more pronounced compared to the cathodic branch. This asymmetry can be attributed to the p-type nature of PEDOT, where oxidation (doping) processes in the positive potential region are more efficient than reduction (dedoping) processes in the negative range. Additionally, the PSS matrix restricts ion transport during dedoping, further lowering the cathodic response. As a result, the charge storage is mainly dominated by the anodic side. The relatively narrow enclosed area and low current densities, particularly at low scan rates (e.g., 25 mV/s), demonstrate that the energy storage capability of pristine PEDOT:PSS is limited. This highlights the necessity of incorporating high-surface-area materials such as activated carbon to enhance the double-layer charge storage and improve the overall specific capacitance.

Figure 6b depicts the

versus

plot obtained from the cyclic voltammetry data of the pristine PEDOT:PSS electrode. The linear fitting of the data yields a slope of approximately 0.4. In electrochemical systems, this parameter provides insight into the dominant charge storage mechanism: slope close to 0.5 indicates diffusion-controlled behavior, whereas a value near 1 suggests a surface-confined (capacitive) process. The observed slope of 0.40 thus confirms that the electrochemical response of PEDOT:PSS is primarily governed by ion diffusion within the electrode bulk rather than by purely capacitive surface reactions. The PEDOT:PSS electrode modified with 20 wt% activated carbon (AC) exhibited a significant enhancement in electrochemical performance, as shown in the

Figure 6c–f by the CV, GCD, and kinetic analysis results.

CV curves in

Figure 6c shows that the incorporation of AC led to a more rectangular and symmetric shape across various scan rates, indicating an increased capacitive character and faster charge propagation at the electrode–electrolyte interface. The galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements confirmed this improvement as seen in

Figure 6d, revealing a specific capacitance of 25 F/g, which is higher than that of pristine PEDOT:PSS.

Figure 6e illustrates the

versus

plot for the composite showed a slope of approximately 0.50, compared to 0.40 for the unmodified electrode. This shift in slope suggests a transition from a predominantly diffusion-controlled process toward a more balanced or mixed mechanism, with greater contribution from surface-controlled (capacitive) charge storage. The increased slope is attributed to the porous structure and high surface area of AC, which facilitate better electrolyte accessibility and more efficient ion transport, thereby improving the overall kinetics of the system.

The capacitive contribution of the PEDOT: PSS/AC (20%) electrode was further quantified as a function of scan rate, and the results are illustrated in the

Figure 6f. At a low scan rate of 25 mV/s, the capacitive contribution was approximately 20%, indicating that the charge storage process at this rate is predominantly diffusion-controlled. However, as the scan rate increased, the capacitive behavior became more pronounced, reaching nearly 80% at 200 mV/s. This trend highlights a fundamental characteristic of hybrid electrode materials: at low scan rates, ions have sufficient time to diffuse into the bulk of the electrode, activating deeper redox sites; whereas at high scan rates, only surface-accessible sites participate, favoring capacitive (surface-limited) charge storage. The increased capacitive dominance at higher scan rates in the composite electrode confirms the effectiveness of activated carbon in enhancing the surface kinetics and fast electrochemical response of the system. Such behavior is desirable for high-power applications where rapid charge/discharge capability is essential.

In order to systematically evaluate the electrochemical performance of PEDOT:PSS/AC, a two-cell system was fabricated. The active material was prepared strictly following the procedure outlined in

Figure 1, ensuring consistency in the fabrication process, and subsequently subjected to electrochemical characterization. The electrochemical tests were conducted using a cellulose-based electrolyte, which had been impregnated with 1M H

2SO

4, and the assembled cells were subsequently subjected to detailed electrochemical characterization.

The CV curves of symmetric devices constructed by PEDOT:PSS/AC electrodes, acquired at various scan rates between 25 and 200 mV/s within a potential range of -0.5 to 0.5 V, are shown in

Figure 7a. Ideal capacitive behavior and effective charge storage are indicated by the curves which are approximately rectangular shape. As the scan rate increases, the enclosed region of the CV curves expands and the current response increases, indicating an increase in the capacitive contribution. Higher scan rates (e.g., 200 mV/s) show a little distortion from the rectangular shape, however this departure is primarily due to internal resistance and ion diffusion restrictions. Overall, the findings demonstrate that throughout a broad range of scan rates, the PEDOT:PSS/AC electrode retains its quick charge-discharge capability and stable capacitive properties.

Figure 7b shows the galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) profiles of device measured at different current densities (10–160 mA/g) within the potential window of –0.5 to 0.5 V. The curves exhibit a nearly symmetric triangular shape, indicating a typical capacitive behavior and efficient charge–discharge reversibility. Based on the discharge profiles, a specific capacitance of ~8 F/g was calculated at a low current density of 10 mA/g. Furthermore, the almost identical charging and discharging times reflect a high Coulombic efficiency, confirming the promising electrochemical reversibility of the electrode. The absence of an evident IR drop further demonstrates the good conductivity and low internal resistance of the composite electrode.

Figure 7c depicts the Nyquist plot of the device measured in the frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz (inset: enlarged high-frequency region). The intercept at the real axis corresponds to the solution resistance (R

s), which is found to be relatively small, indicating good ionic conductivity of the cellulose/H

2SO

4 electrolyte. The absence of a pronounced semicircle in the high-frequency region suggests a low charge-transfer resistance (R

ct), further confirming efficient electron/ion transport at the electrode–electrolyte interface. At low frequencies, the plot exhibits an almost vertical line, which is characteristic of ideal capacitive behavior and efficient ion diffusion. These EIS results highlight the favorable electrochemical kinetics and low internal resistance of the PEDOT:PSS/AC composite electrodes in the device.

The log(i)–log(v) relationship for the symmetric device derived from CV measurements at various scan speeds is displayed in

Figure 7d. The linear fit has an outstanding correlation coefficient (R

2 = 0.99) and a slope (b-value) of 0.60. Given that a surface-controlled capacitive process is indicated by a b-value of 1.0 and a diffusion-controlled process by a b-value of 0.5, the obtained slope of 0.6 implies that the charge storage in the sandwich device results from a mixed mechanism. Specifically, capacitive surface redox contributions and diffusion-limited ion intercalation coexist, with capacitive effects being marginally more significant. The desired characteristics of pseudocapacitive electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors are in line with this hybrid behavior.

Figure 7e illustrates the capacitive contribution ratio of the PEDOT:PSS/AC electrode at different scan rates, calculated at a potential of 0.15 V. The capacitive contribution increases progressively from 33% at 10 mV/s to 63% at 200 mV/s. This trend indicates that at higher scan rates, the charge storage is increasingly dominated by capacitive processes rather than diffusion-controlled contributions. Such behavior demonstrates the excellent rate capability of the electrode, as it can sustain fast charge–discharge processes with minimal diffusion limitations.

Figure 7f presents the Ragone plot of the PEDOT:PSS/AC electrode in comparison with other energy storage and conversion systems. The results indicate that the device exhibits an intermediate performance between conventional capacitors and batteries, delivering a promising balance of high-power density and moderate energy density, which is characteristic of pseudocapacitive materials. Furthermore, the long-term cycling stability shown in

Figure 7g demonstrates that the electrode retains ~97% of its initial capacitance after 2000 continuous charge–discharge cycles. This excellent retention confirms the durability and structural stability of the composite, highlighting its potential for practical supercapacitor applications.