Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Species Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Phenotypic Assays

2.4. Chromosomal Modifications in LPS Biosynthesis

2.5. Molecular Detection of Resistance Genes

2.6. Detection of Virulence-Associated Genes in K. pneumoniae

2.7. Molecular Epidemiology and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.8. Characterization of Outer Membrane Proteins and Sequencing of ompK35 and ompK36 Genes

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Colistin Resistance in CRKP Isolates and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile

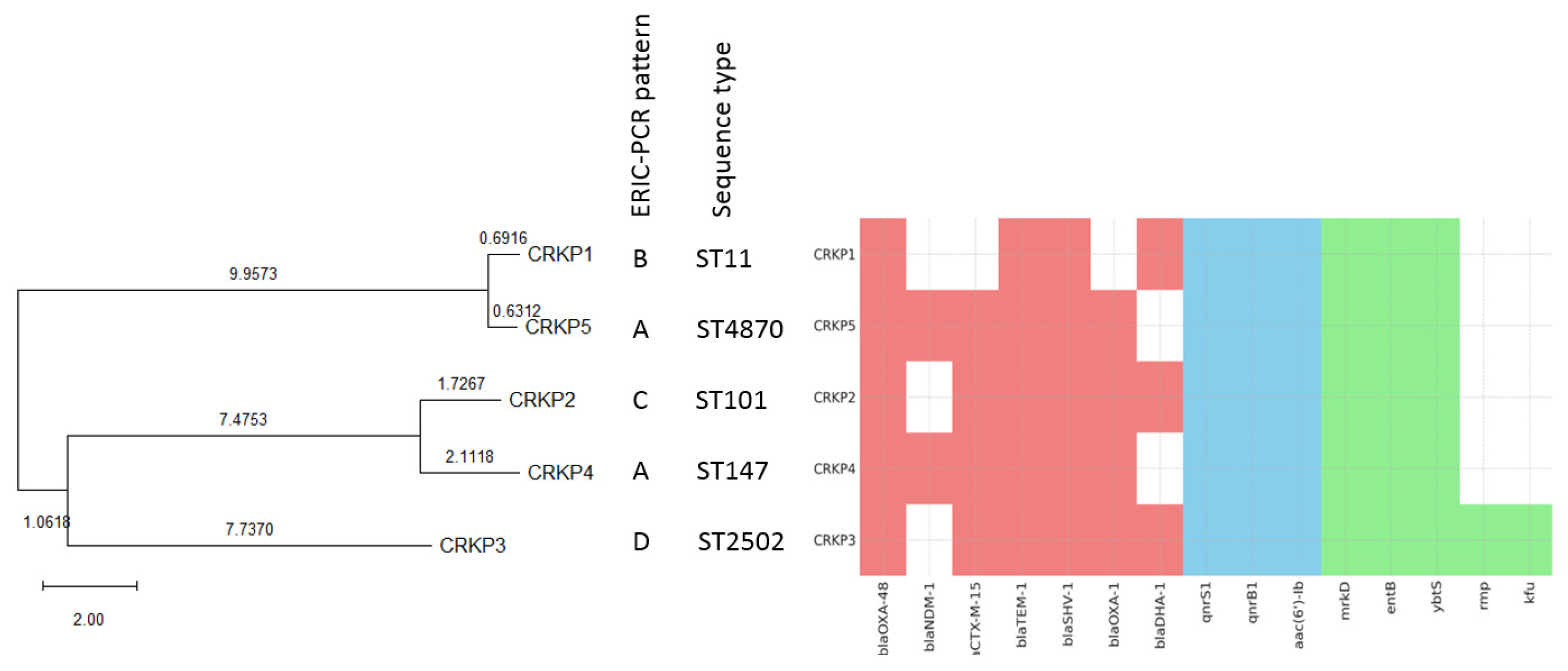

3.2. Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

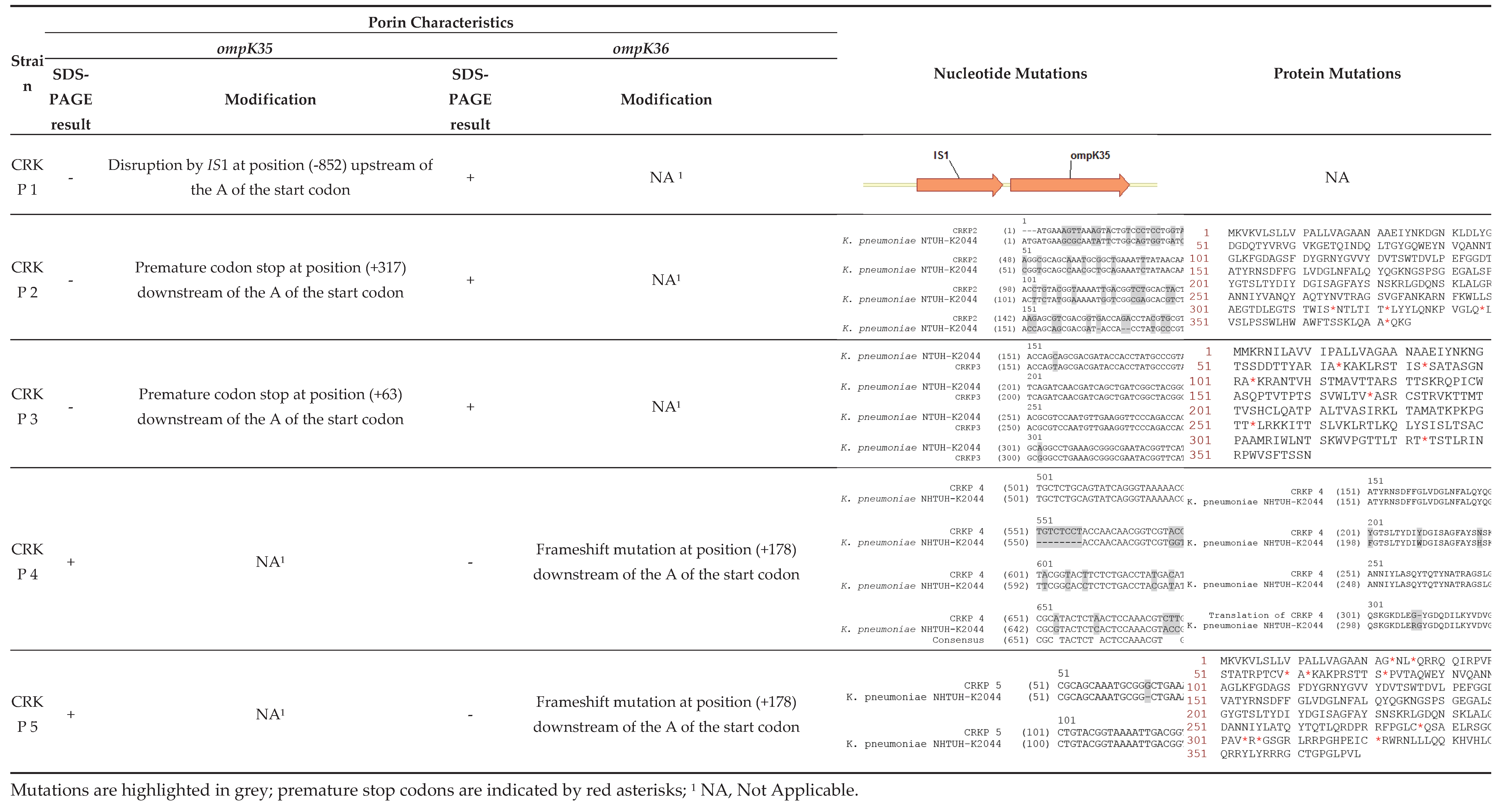

3.3. Porin Expression and ompk35/ompk36 Alterations

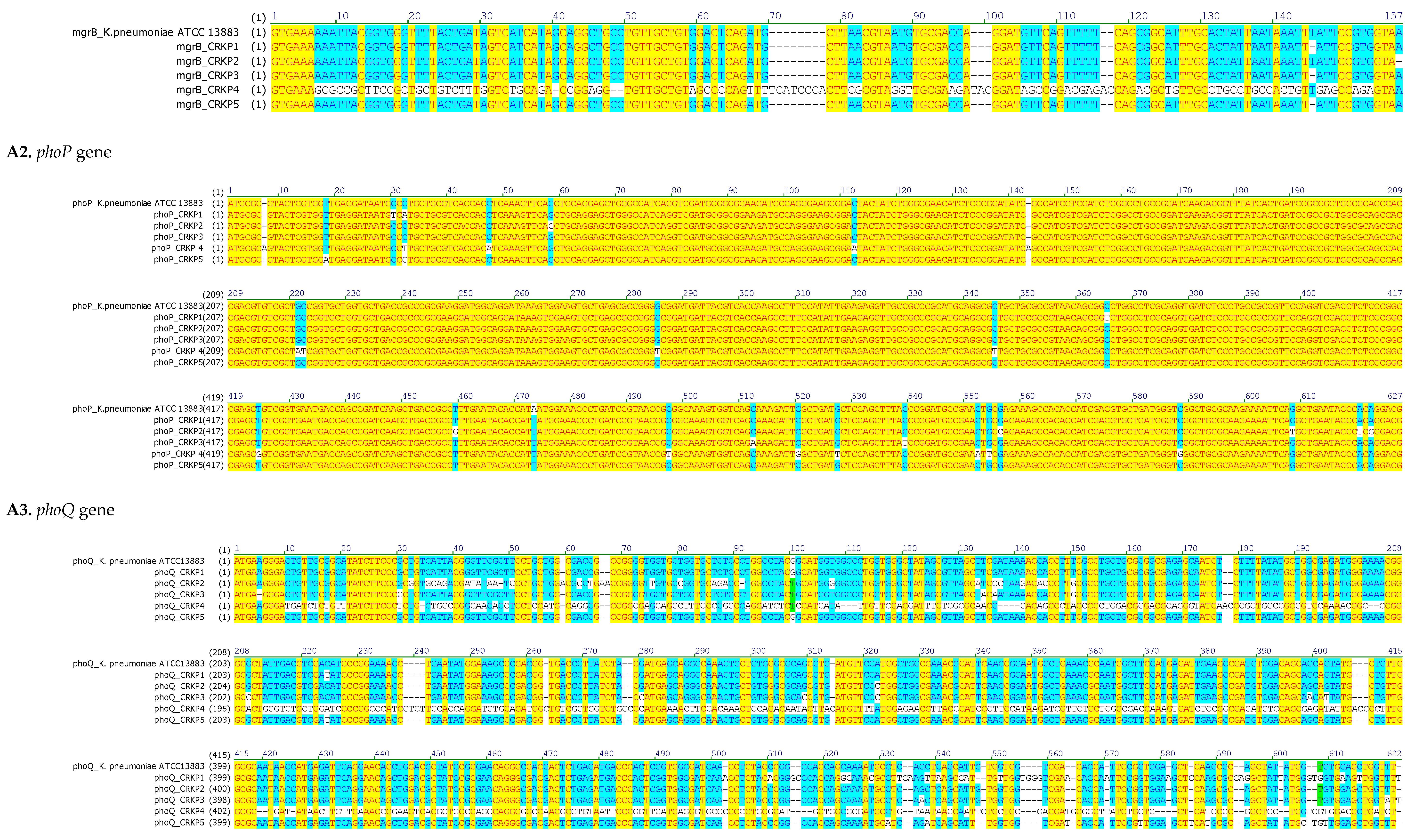

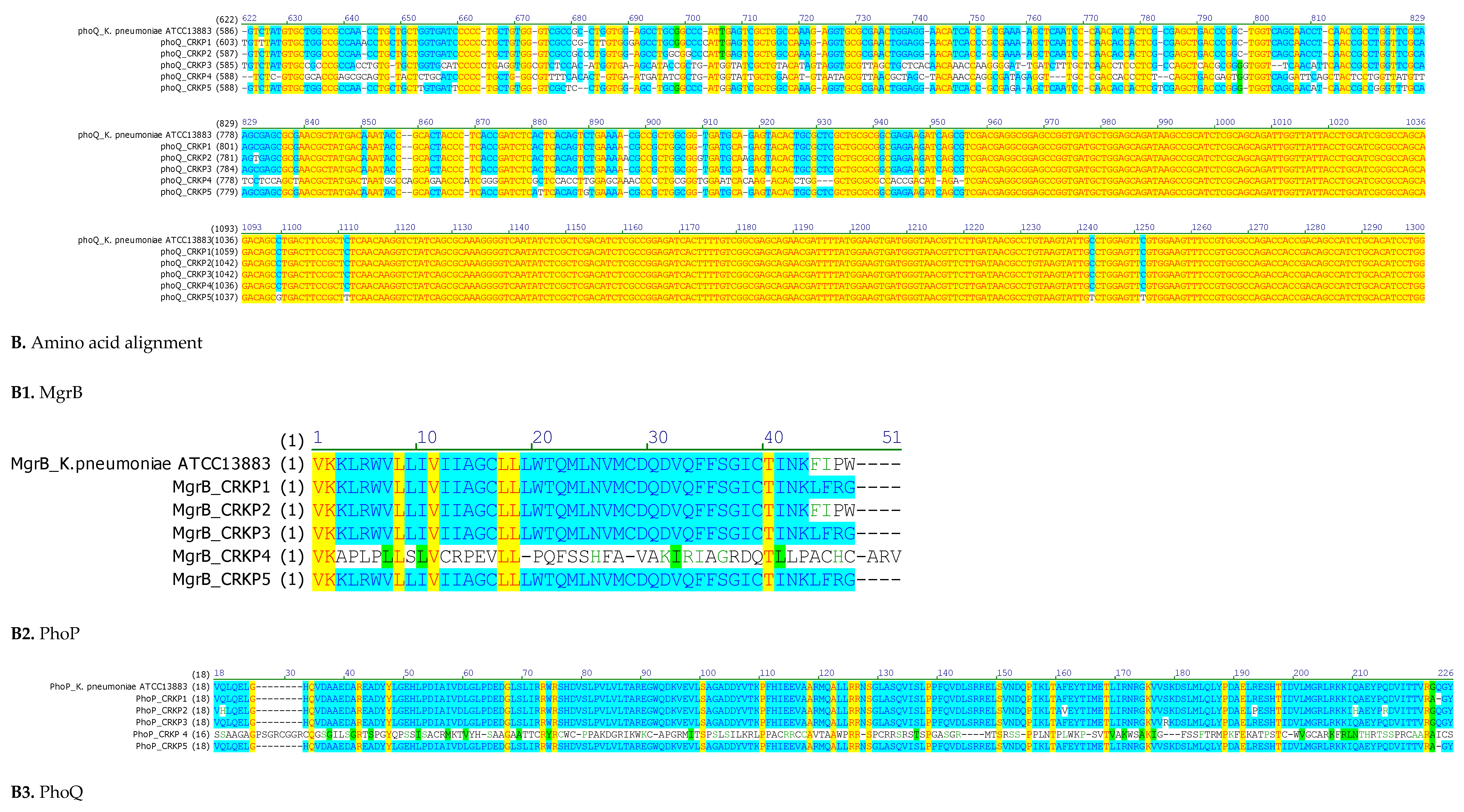

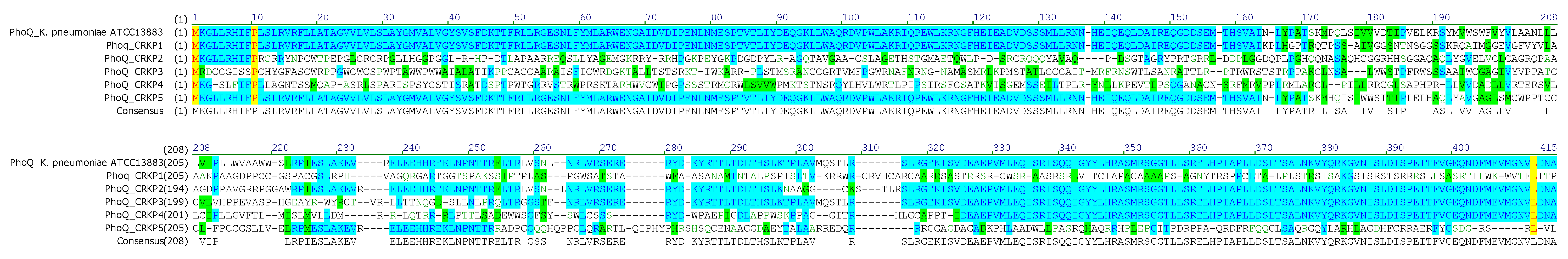

3.4. Chromosome-Mediated Colistin Resistance: Mutations in mgrB, phoP and phoQ

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CIM | Carbapenem Inactivation Method |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CRKP | Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| DDST | Double Disk Synergy Test |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ERIC-PCR | Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum β-lactamase |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization–Time of Flight |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MEGA | Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| NDM | New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase |

| OMP | Outer membrane protein |

| PBA | Phenylboronic acid |

| PMQR | Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| ST | Sequence type |

| TCS | Two-component system |

References

- Mohammadpour, D.; Memar, M.Y.; Leylabadlo, H.E.; Ghotaslou, A.; Ghotaslou, R. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae: A Comprehensive Review of Phenotypic and Genotypic Methods for Detection. The Microbe 2025, 6, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Song, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, H. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella: Advances in Detection Methods and Clinical Implications. Infect Drug Resist 2025, 18, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial Activity, Susceptibility Testing, and Resistance Mechanisms Encoded by Plasmids or Chromosomes. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017, 30, 557–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, S.; Alharbi, J.; Alattas, B.; Alotaibi, D.; Althibaiti, N.; Alharbi, J.; SafirAldeen, A.; Alqurashi, I.; Wali, S. Promising Future of Novel Beta-Lactam Antibiotics Against Bacterial Resistance. DDDT 2025, Volume 19, 9185–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayh, G.; Nsibi, F.; Abdallah, K.; Abbes, O.; Fliss, I.; Messadi, L. Phenotypic and Molecular Study of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli Isolates Expressing Diverse Resistance and Virulence Genes from Broilers in Tunisia. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferjani, S.; Maamar, E.; Ferjani, A.; Meftah, K.; Battikh, H.; Mnif, B.; Hamdoun, M.; Chebbi, Y.; Kanzari, L.; Achour, W.; et al. Tunisian Multicenter Study on the Prevalence of Colistin Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Gram Negative Bacilli: Emergence of Escherichia Coli Harbouring the Mcr-1 Gene. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengui, M.; Trabelsi, R.; Gdoura, R.; Hamieh, A.; Zerrouki, H.; Rolain, J.-M.; Hadjadj, L. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Gram-Negative Bacteria in Southern Tunisia: Focus on ESBL, Carbapenem and Colistin Resistance. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2025, 133, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaidane, N.; Bonnin, R.A.; Mansour, W.; Girlich, D.; Creton, E.; Cotellon, G.; Chaouch, C.; Boujaafar, N.; Bouallegue, O.; Naas, T. Genomic Insights into Colistin-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae from a Tunisian Teaching Hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e01601–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). 2014.

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Twenty-Third Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-S23 2013.

- Van Der Zwaluw, K.; De Haan, A.; Pluister, G.N.; Bootsma, H.J.; De Neeling, A.J.; Schouls, L.M. The Carbapenem Inactivation Method (CIM), a Simple and Low-Cost Alternative for the Carba NP Test to Assess Phenotypic Carbapenemase Activity in Gram-Negative Rods. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, P.D.; Simner, P.J. Phenotypic Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms from Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2018, 56, e01140–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.; Rekatsina, P.D.; Hatzaki, D.; Plachouras, D.; Souli, M.; Giamarellou, H. Evaluation of Different Laboratory Tests for the Detection of Metallo- -Lactamase Production in Enterobacteriaceae. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2008, 61, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallenne, C.; Da Costa, A.; Decré, D.; Favier, C.; Arlet, G. Development of a Set of Multiplex PCR Assays for the Detection of Genes Encoding Important β-Lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2010, 65, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Dortet, L.; Bernabeu, S.; Nordmann, P. Genetic Features of BlaNDM-1 -Positive Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 5403–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacoby, G.A.; Strahilevitz, J.; Hooper, D.C. Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance. Microbiol Spectr 2014, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Martínez, M.; Miró, E.; Ortega, A.; Bou, G.; González-López, J.J.; Oliver, A.; Pascual, A.; Cercenado, E.; Oteo, J.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; et al. Molecular Identification of Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzymes in Clinical Isolates of Escherichia Coli Resistant to Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid Isolated in Spain. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2015, 46, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyrouthy, R.; Robin, F.; Lessene, A.; Lacombat, I.; Dortet, L.; Naas, T.; Ponties, V.; Bonnet, R. MCR-1 and OXA-48 In Vivo Acquisition in KPC-Producing Escherichia Coli after Colistin Treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e02540–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafeuille, E.; Decré, D.; Mahjoub-Messai, F.; Bidet, P.; Arlet, G.; Bingen, E. OXA-48 Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolated from Libyan Patients. Microbial Drug Resistance 2013, 19, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, I.G.; Chowdhury, M.A.; Huq, A.; Jacobs, D.; Martins, M.T.; Colwell, R.R. Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus Sequences and the PCR to Generate Fingerprints of Genomic DNAs from Vibrio Cholerae O1, O139, and Non-O1 Strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 1995, 61, 2898–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diancourt, L.; Passet, V.; Verhoef, J.; Grimont, P.A.D.; Brisse, S. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Nosocomial Isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 4178–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Martínez, L.; Conejo, M.C.; Pascual, A.; Hernández-Allés, S.; Ballesta, S.; Ramírez De Arellano-Ramos, E.; Benedí, V.J.; Perea, E.J. Activities of Imipenem and Cephalosporins against Clonally Related Strains of Escherichia Coli Hyperproducing Chromosomal β-Lactamase and Showing Altered Porin Profiles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 2534–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, Z.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.; Fernandez Martinez, M.; Landolsi, S.; Ferjani, S.; Maamar, E.; Saidani, M.; Slim, A.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Boutiba-Ben Boubaker, I. Role of Association of OmpK35 and OmpK36 Alteration and blaESBL and/or blaAmpC Genes in Conferring Carbapenem Resistance among Non-Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2018, 52, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzairue, L.I.; Rabaan, A.A.; Adewumi, F.A.; Okolie, O.J.; Folorunso, J.B.; Bakhrebah, M.A.; Garout, M.; Alfouzan, W.A.; Halwani, M.A.; Alamri, A.A.; et al. Global Prevalence of Colistin Resistance in Klebsiella Pneumoniae from Bloodstream Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, W.; Haenni, M.; Saras, E.; Grami, R.; Mani, Y.; Ben Haj Khalifa, A.; El Atrouss, S.; Kheder, M.; Fekih Hassen, M.; Boujâafar, N.; et al. Outbreak of Colistin-Resistant Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Tunisia. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2017, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aris, P.; Robatjazi, S.; Nikkhahi, F.; Amin Marashi, S.M. Molecular Mechanisms and Prevalence of Colistin Resistance of Klebsiella Pneumoniae in the Middle East Region: A Review over the Last 5 Years. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2020, 22, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Morand, S.; Rolain, J.-M. Mechanisms of Polymyxin Resistance: Acquired and Intrinsic Resistance in Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, Y.; Tekerekoğlu, M.S.; Kuzucu, Ç.; Yakupoğullari, Y. The Effects of Colistin on Imipenem MICs in OXA-48 Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates: An In-Vitro Study. mjima 2021. [CrossRef]

- Katip, W.; Oberdorfer, P.; Kasatpibal, N. Effectiveness and Nephrotoxicity of Loading Dose Colistin–Meropenem versus Loading Dose Colistin–Imipenem in the Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii Infection. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovich, T.; Adams-Haduch, J.M.; Tian, G.-B.; Nguyen, M.H.; Kwak, E.J.; Muto, C.A.; Doi, Y. Colistin-Resistant, Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Belonging to the International Epidemic Clone ST258. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 53, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Yan, Q.; Liu, W. Prevalence and Molecular Characteristics of Colistin-Resistant Isolates among Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Central South China: A Multicenter Study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2025, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, M.P.; Martinez, R.; Brito, B.; García, P.; Legarraga, P.; Wozniak, A. Chromosome-Mediated Colistin Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Escherichia Coli: Mutation Analysis in the Light of Genetic Background. IDR 2023, Volume 16, 6451–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziri, O.; Dziri, R.; Ali El Salabi, A.; Chouchani, C. Carbapenemase Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria in Tunisia: History of Thirteen Years of Challenge. IDR 2020, Volume 13, 4177–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, Z.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.; Maamar, E.; Fernandez Martinez, M.; Ferjani, S.; Hammami, S.; Harbaoui, S.; Genel, N.; Arlet, G.; Saidani, M.; et al. An Outbreak of NDM-1-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Associated with OmpK35 and OmpK36 Porin Loss in Tunisia. Microbial Drug Resistance 2018, 24, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, A.; Haenni, M.; Bouallègue, O.; Saras, E.; Chatre, P.; Chaouch, C.; Boujâafar, N.; Mansour, W.; Madec, J.-Y. Dynamics and Molecular Features of OXA-48-like-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Lineages in a Tunisian Hospital. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2020, 20, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrër, A.; Poirel, L.; Eraksoy, H.; Cagatay, A.A.; Badur, S.; Nordmann, P. Spread of OXA-48-Positive Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates in Istanbul, Turkey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52, 2950–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argente, M.; Miró, E.; Martí, C.; Vilamala, A.; Alonso-Tarrés, C.; Ballester, F.; Calderón, A.; Gallés, C.; Gasós, A.; Mirelis, B.; et al. Molecular Characterization of OXA-48 Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains after a Carbapenem Resistance Increase in Catalonia. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2019, 37, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, X.; Jia, X.; Yu, W.; Cui, Y.; Yang, R.; Xia, W.; et al. Emergence of Colistin-Resistant Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae (CoR-HvKp) in China. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2022, 11, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, B.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, X.; Chen, S.; Ni, M.; Hu, Y. Mobile Plasmid Mediated Transition From Colistin-Sensitive to Resistant Phenotype in Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 619369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannatelli, A.; Giani, T.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Di Pilato, V.; Arena, F.; Conte, V.; Tryfinopoulou, K.; Vatopoulos, A.; Rossolini, G.M. MgrB Inactivation Is a Common Mechanism of Colistin Resistance in KPC-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae of Clinical Origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 5696–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordham, S.M.E.; Mantzouratou, A.; Sheridan, E. Prevalence of Insertion Sequence Elements in Plasmids Relating to mgrB Gene Disruption Causing Colistin Resistance in Klebsiella Pneumoniae. MicrobiologyOpen 2022, 11, e1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeili, M.; Javani, A.; Moradi, J.; Jafari, Z.; Feizabadi, M.M.; Babaei, E. MgrB Alterations Mediate Colistin Resistance in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates from Iran. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogry, F.A.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Sultan, I.; Haq, Q. Mohd. R. Current Update on Intrinsic and Acquired Colistin Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 677720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Strain ID | Ward | Specimen Type | Isolation Date | Age (Years)/Gender | Underlying Disease | Antibiotic Treatment | Outcome | |

| 1 | CRKP 1 | ICU1 | Pulmonary | 2013 | 27/M2 | Respiratory distress | Tigecycline, Gentamicin, Ceftazidime | Improved | |

| 2 | CRKP 2 | Orthopedics | Catheter | 2015 | 84/F3 | Polytraumatism | Amoxicillin+clavulanate | Improved | |

| 3 | CRKP 3 | ICU1 | Catheter | 2015 | 75/M2 | Respiratory distress | Vancomycin, Imipenem, Rifampin, Amikacin, Colistin, Fosfomycin | Died | |

| 4 | CRKP 4 | ICU1 | Pulmonary | 2015 | 32/M2 | Polytraumatism | Gentamicin, Imipenem, Colistin, Vancomycin, Ciprofloxacin | Improved | |

| 5 | CRKP 5 | ICU | Wound | 2015 | 24/M2 | Polytraumatism | Amoxicillin+clavulanate, Gentamicin, Imipenem, Fosfomycin, Colistin, Ciprofloxacin | Improved |

| Strain | Resistance Patterns | Phenotypic Assays | MICs* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MHT1 | CIM2 | EDTA3 | PBA4 | E-Test Strips | VITEK | Broth Microdilution Method | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ETP20 | IMP21 | MEM22 | AMP5 | AMC6 | TZP7 | CXM8 | FOX9 | CTX10 | CAZ11 | FEP13 | AMK14 | 19GM | NAL15 | CIP16 | TGC18 | SXT17 | COL23 | ||||||||||

| CRKP 1 | AMP5, AMC6, TZP7, CXM8, FOX9, CTX, 10 CAZ11, CRO12, FEP13, AMK14, NAL15, 16CIP, SXT1717 | + | + | - | - | >32 | 24 | 24 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥128 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≤1 | 16 | ≤1 | ≥32 | ≥4 | 1 | ≥320 | 32 | ||||

| CRKP 2 | AMP5, AMC6, TZP7, CXM8, FOX9, CTX10, CAZ11, CRO12, FEP13, AMK14, GM19, NAL15, 16CIP, SXT17 | + | + | - | - | >32 | 4 | 12 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥128 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 16 | ≥16 | ≥32 | ≥4 | 2 | 40 | 16 | ||||

| CRKP 3 | AMP5, AMC6, TZP7, CXM8, FOX9, CTX10, CAZ11, CRO12, FEP13, AMK14, GM19, NAL15, 16CIP, TGC18, SXT17 | + | + | - | - | >32 | 4 | 6 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥128 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 16 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥16 | ≥32 | ≥4 | 2 | ≥320 | 8 | ||||

| CRKP 4 | AMP5, AMC6, TZP7, CXM8, FOX9, CTX10, CAZ11, CRO12, FEP13, GM, NAL15, 16CIP, TGC18, SXT17 | + | + | + | - | 32 | 12 | 16 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥128 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 16 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥32 | ≥4 | 4 | ≥320 | 8 | ||||

| CRKP 5 | AMP5, AMC6, TZP7, CXM8, FOX9, CTX10, CAZ11, CRO12, FEP13, GM, NAL15, 16CIP, TGC18, SXT17 | + | + | + | - | 2 | 2 | 1 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥128 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥32 | ≥4 | 4 | ≥320 | 8 | ||||

| Strain | mgrB Mutations | Predicted Effect | phoP Mutations | Predicted Effect | phoQ Mutations | Predicted Effect |

| CRKP1 | ΔT132 | Frameshift →Altered protein sequence | C29T; C31A; C363T | AA substitutions | C219T; InsA486; InsGC, 498-499 | Premature stop codon at AA 175 |

| CRKP2 | None | Intact MgrB | G57C; T457G; G554C | AA substitutions | T32G; C35G; A36C; T37A; T38G; ΔC48; InsA58; InsAA65-66; ΔC91 |

Premature stop codon at AA 41 |

| CRKP3 | ΔT132 | Frameshift → altered protein sequence | A471T; C510A; C537T | AA substitutions | ΔA5; G29C; T130A; ΔC611 | Frameshift → altered protein sequence |

| CRKP4 | Multiple point mutations; ΔA42, ΔCC48-49 |

Premature stop at AA19 | InsA7; C32T; C47A; C112A; InsA143 | Premature stop codon at AA7 | C10T; T11G; G12A; T14C; G15T; G17T; C19T; A20T ; ΔT34 ; ΔGCC105-106-107 | Premature stop codon at AA 4 |

| CRKP5 | ΔT132 | Frameshift → altered protein sequence | T17A; C31G | AA substitutions | C219T; C512A; C517A; ΔG527; InsT538 | Premature stop codon at AA 207 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).