1. Introduction

The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a multi-ligand receptor of the immunoglobulin family, belonging to MHC class III [

1]. The full-length form of RAGE (FL-RAGE) has one V-type domain, two C-type domains, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail. The V-type domain has two glycosylation sites and is responsible for binding most extracellular ligands [

2]. The cytoplasmic tail is considered essential for intracellular signaling. Originally, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) were identified as the primary RAGE agonists, however, a wide range of additional ligands have since been discovered, including the HMGB1 protein, members of the S100 protein family, extracellular matrix components such as collagen I and II, and beta-amyloids [

3]. Intracellular signaling, initiated by ligand binding with RAGE, includes the activation of NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinase, PI3K/AKT, GTPase and protein kinase C pathways [

4]. In addition to membrane-bound ones, truncated soluble RAGE isoforms have also been identified, which represent the RAGE ectodomain and are formed by proteolytic cleavage of FL-RAGE or by alternative splicing [

5,

6].

High levels of RAGE expression are characteristic of embryonic tissues, where its primary function is to control organogenesis. This receptor is particularly important for the development and maturation of the central nervous system [

7] and lungs [

8]. In most differentiated adult cells, such as cardiomyocytes, neurons, and immune cells, RAGE is expressed at a low basal level under normal physiological conditions [

9]. Among all differentiated tissues, only pulmonary ones express uncommonly high basal levels of RAGE. Localized predominantly in the basal membrane of type 1 alveolar cells, this protein plays an important role in maintaining a flattened morphology, which ensures efficient gas exchange and alveolar stability [

10]. Although the mechanisms underlying high levels of RAGE expression in the lungs are not fully understood, recent studies indicate that RAGE is an important mediator in many inflammatory lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis [

11], asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, or allergic airway inflammation [

12]. Chronic inflammatory diseases such as diabetes, cancer, neurodegenerative and vascular pathologies are characterized by elevated RAGE protein expression, caused primarily by accumulation of RAGE ligands. Thus, increased expression of RAGE in the retina, in particular in Müller cells, or in renal cells, including podocytes, mesangial cells, and endothelial cells, plays a leading role in the development of diabetic retinopathy [

13] and nephropathy [

14]. RAGE signaling in cells like neurons, microglia, and astrocytes is involved in the development of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [

15].

Current research on RAGE as a therapeutic target focuses on soluble RAGE (sRAGE), anti-RAGE antibodies, and small-molecule RAGE inhibitors. Based on their mechanism of action, RAGE inhibitors are classified into two groups: those targeting the extracellular region of the receptor and those targeting its intracellular domain. A specific RAGE inhibitor used in this study, FPS-ZM1, is selected from over 5,000 compounds containing a tertiary amide. FPS-ZM1 readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and blocks beta-amyloid binding to RAGE by interacting with the V- domain of RAGE, without interfering with beta-amyloid binding to other receptors [

16]. Evidence suggests that FPS-ZM1 may have a therapeutic potential in several disease models, including diabetes [

17], cancer [

18], and neurodegenerative disorders [

19]. In cultured rat primary microglia, FPS-ZM1 significantly suppressed AGEs-induced inflammation and oxidative stress [

19]. In an in vitro murine cell model of diabetes, FPS-ZM1 partially attenuated AGE-induced increases in ROS production and inflammatory stress [

17]. In a mouse xenograft model, FPS-ZM1 suppressed primary tumor growth and tumor angiogenesis, and prevented metastasis compared with controls [

18].

Although the vector of studying the RAGE biological functions is obviously shifted towards research into its role in pathological conditions, undoubtably, mechanisms mediated by this multiligand receptor play a significant physiological role outside the context of pathologies associated with excessive formation of AGEs. Data are accumulating on the significant role of RAGE in maintaining the functional activity of the immune system, maintaining homeostasis and tissue reparation. Thus, RAGE plays a critical role in the maturation and mobilization of dendritic cells [

20]. Animal models have shown the involvement of RAGE signaling in adult neurogenesis and into the regeneration of injured skeletal muscles [

21].

Research interest in the regulatory role of RAGE in realization of biological functions by the most numerous cells of the immune system, neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes, PMNLs), is primarily associated with their contribution to the development of diabetic complications. Indeed, microbial persistence, greater susceptibility to infections, relapses, and an increased risk of mortality from infectious diseases, due to impaired granulocyte immunity, are characteristic of diabetic patients. Overexpression of RAGE in neutrophils induced by the interaction of these cells with AGEs, suppresses the neutrophil extravasation and pathogen-killing abilities. Consequently, neutrophils cannot effectively stimulate the formation of the inflammatory belt needed to remove necrotic tissues and defend against foreign microorganisms within diabetic chronic wounds [

22]. Neutrophil pretreatment with glycated albumin inhibited elevation of intracellular calcium levels promoted by fMLP, causing a defective signal processing and, consequently, a reduction the responses of these cells to chemotactic stimulus [

23]. However, the available data on the role of RAGE in the control of AGE-independent effector functions of neutrophils are still quite scarce and sometimes ambiguous. The difficulties in forming clear ideas on this issue are related to the fact that neutrophils not only express membrane RAGE [

24], but are also capable of active secretion of its ligands, most notably S100A12 and HMGB1 [

25]. The aim of this study was to investigate the expression of the RAGE protein in peripheral neutrophils of healthy donors and the involvement of RAGE in the control of the effector functions of human neutrophils during their interaction with gram-negative

S. typhimurium bacteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dextran T-500 was from Pharmacosmos (Holbæk, Denmark). Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with magnesium but without calcium, Hank’s balanced salt solution with calcium and magnesium but without Phenol Red and sodium hydrogen carbonate (HBSS), Iron containing superoxide-dismutase (Fe-SOD) from E. coli, Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium (L6511), N-Formyl-L-methionyl-L-Leucyl-L-Phenylalanine (fMLP), FPS-ZM1 (Calbiochem®) were purchased from Sigma (Steinheim, Germany). Fibrinogen from human plasma and 4,5-Diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA) were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). 6-carboxy-2,7 dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (Carboxy-H2DCF-DA), Dihydroethidium (DHE) and Fura-2 AM, Anti-RAGE Recombinant Mouse Monoclonal Antibody [2A11] (Invitrogen) and Goat anti-Mouse IgG Superclonal Recombinant Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Human AGER (Advanced Glycosylation End Product Specific Receptor) ELISA Kit was purchased from ELK Biotechnology (Sugar Land, TX, USA).

Bacteria (strain S. typhimurium IE 147) were obtained from the collection of the N.F. Gamaleya National Research Center for Epidemiology and Microbiology (Moscow, Russia). Bacteria were grown in Luria–Bertani broth to a concentration of 1 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. Bacteria were opsonized immediately before the experiment in 10% (v/v) donor serum for 30 min at 37°C followed by washing with PBS.

2.2. Neutrophil Isolation

Human peripheral neutrophils were isolated from the citrate-anticoagulated blood of healthy volunteers by previously described standard technique [

26]. Experimental and the subject consent procedures were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Lomonosov Moscow State University, Application # 6-h, version 3, Bioethics Commission meeting # 131-d held on May 31, 2021.

Briefly, after dextran sedimentation allowing the removal of erythrocytes, neutrophils were isolated from leukocyte-rich plasma by centrifugation through Ficoll-Paque (1.077 g/mL), followed by hypotonic lysis of the remaining erythrocytes and double washing with PBS. Neutrophils (96–97% purity, 98–99% viability as established by trypan blue staining) were then suspended at 2x107 cells/mL D-PBS containing 1 mg/mL glucose and stored at room temperature.

2.3. Intracellular Free Calcium Ion Concentration ([Ca2+]i) Assessment

To detect changes in [Ca2+]i, the ratiometric calcium-sensitive fluorescent dye fura-2 AM was used. The manufacturer’s instructions were partially adapted to work with neutrophils. Briefly, isolated PMNLs (107 cells/mL) were incubated with 1 µM fura-2 AM in Ca2+-free Dulbecco’s PBS for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, cells were pelleted (200 g, 10 min), washed once with PBS, and resuspended in Dulbecco’s PBS. Immediately before the experimental procedure, labeled cells were resuspended in pre-warmed HBSS medium supplemented with 0,01 M HEPES (HBSS/HEPES), seeded in fibrinogen-coated 96-well black F-bottom plates, and treated according to the experimental design at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Reagent injectors integrated into the reader platform were used for stimuli addition. Changes in fluorescence emitted at 510 nm were measured when exited by both 380 nm (for Ca2+-free dye) and 335 nm (for Ca2+-bound dye) every 0.6 s. Manipulations were performed on a CLARIOstar multimode microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA) and the MARS data analysis software package version 3.30 from BMG Labtech was used to process the data obtained. [Ca2+]i shifts were judged by changes in the ratio of fluorescence intensities produced by excitation at two wavelengths. Data were quantified using areas under the kinetic curves (AUC) above the baseline.

2.4. ROS Assessment

Total superoxide anion (O

2-.) production was detected by measuring hydroxyethidium (EOH) fluorescence [

27]. PMNLs were suspended in HBSS/HEPES supplemented with 10 µg/mL DHE and divided into fibrinogen-coated wells of 96-well black F-bottom plates (4x10

5 cells/well) followed by incubation, at 37 °C, in 5% CO

2 in accordance with experimental protocol. To detect the intracellular O

2-. pool, Fe-SOD (100 U/mL) was added to the probes. Fluorescence intensity was measured 40 min after adding stimuli using a CLARIOstar microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 370 and 567 nm, respectively.

Cytoplasmic ROS production was monitored by measuring green fluorescence of H2DCF oxidation product according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, PMNLs were incubated with 2.5 µM Carboxy-H2DCF-DA for 60 min at RT, followed by washing with PBS. Cells were then resuspended in HBSS/HEPES, divided into fibrinogen-coated wells of a 96-well black F-bottom plates (4x105 cells/well) and incubated at 37 °C, in 5% CO2 in accordance with experimental protocol. Fluorescence intensity was measured 40 min after adding stimuli using a CLARIOstar microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 535 nm, respectively.

2.5. Nitric Oxide (NO) Detection

NO production was monitored by measuring green fluorescence of triazolofluorescein (DAF-2T), the reaction product of DAF-2 with NO. PMNLs were incubated with 5 µM DAF-2 DA for 60 min, at room temperature, followed by washing with PBS. Loaded PMNLs were then resuspended in HBSS/HEPES, divided into fibrinogen-coated wells of a 96-well plate (4x105 cells/well) and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in accordance with experimental protocol. Fluorescence intensity was measured 40 min after adding stimuli using a CLARIOstar microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 535 nm, respectively.

2.6. Phagocytosis Assessment

PMNLs (10

6 cells in 1 mL aliquots of HBSS/HEPES) supplemented or not with FPS-ZM1, were incubated in Eppendorf tubes for 5 min at 37 °C, 5% CO

2 with continuous stirring. Then, opsonized FITC-labeled

S. typhimurium bacteria were added, so that their multiplicity of infection (MOI) was approximately 20, for further 10 min incubation under the same conditions. PMNLs were then collected by centrifugation at 200 g, 4°C and resuspended in cold PBS followed by flow cytometry (excitation of 488 nm, emission of 525 nm) on SinoCyte X Flow Cytometer (Biosino Medical Technology Co., Ltd, Suzhou City, China). To differentiate between internalized and surface-bound bacteria, trypan blue (TB), at a working concentration of 1 mg/mL, was used for quenching surface FITC fluorescence [

28]. Both relative amounts of PMNLs involved in phagocytosis and fluorescence intensities reflecting an average number of bacteria captured per cell were estimated. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and results were visualized with GraphPad Prism

2.7. sRAGE Detection in Cell Culture Supernatants

Quantitative assessment of sRAGE in PMNLs supernatants was performed using a commercial ELISA kit. Briefly, PMNLs (106 cells/1 mL HBSS/HEPES per probe) were seeded in fibrinogen-coated 24-well plates and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in accordance with experimental protocol. After the required incubation time, the supernatants were collected, the cells were precipitated by centrifugation at 200 g, 10 min, 4 °C, and the supernatant was centrifuged again at 10000 g, 20 min, 4 °C. Subsequent manipulations were carried out in strict accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density (absorbance at 450 nm (Abs450)) was measured using a CLARIOstar microplate reader. Abs450 values were converted into sRAGE concentrations using sRAGE standard curve.

2.8. Analysis of RAGE Cellular Localization by Immunofluorescence Microscopy

PMNLs (106 cells/1 mL HBSS/HEPES) were seeded on fibrinogen-coated coverslips placed in Petry dishes and incubated for not more than 5 min at 37 C, 5% CO2. The supernatants were then carefully removed followed by fixation (cold 2.5 % paraformaldehyde PFA) in PBS, containing 0.5 % BSA, 10 min, 4 °C). After removing the fixative solution and washing, samples intended for intracellular antigen staining were permeabilized with ice-cold acetone (3 min), and then rehydrated with PBS. All samples were then blocked for 1 h with 1 % BSA/PBS, incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-RAGE antibody (1:100 dilution in 0.1 % BSA/PBS), rinsed thoroughly with blocking solution, followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse antibodies (1:1500 dilution in 0.1 % BSA/PBS) for 4 h at 4°C. Nuclei were stained with 0.2 μg/ml Hoechst 33342. The samples were visualized by Olympus IX83 fluorescence microscope (provided by the Moscow State University Development Program).

2.9. Flow Cytometry Analysis of RAGE Cellular Expression

Isolated PMNLs cells were transferred to Hanks' solution and collected immediately (for resting PMNLs samples) or after 30 min of incubation under conditions corresponding to the experimental protocol. The collected cells were fixed with cold 2.5 % PFA in PBS, containing 0.5 % BSA (10 min, 4 °C) and washed. The cells were then permeabilized with digitonin (10 µg/mL PBS, 10 min, RT), except for the sample intended for membrane RAGE staining. All samples were then blocked for 1 h with 1 % BSA/PBS, incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-RAGE antibody (1:100 dilution in 0.1 % BSA/PBS), rinsed thoroughly with blocking solution, followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse antibodies (1:1500 dilution in 0.1 % BSA/PBS) for 4 h at 4°C. Fluorescence (ex 488/em 525) was measured on SinoCyte Flow Cytometer. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and results were visualized with Graph-Pad Prism.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.4.3 software. A P -value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. RM One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used to quantify data on [Ca2+]-flux, phagocytosis, sRAGE secretion and flow-cytometric RAGE expression. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s (for between groups differences) or Dunnett’s (for within groups differences) were used to quantify data on ROS/RNS assessment.

3. Results

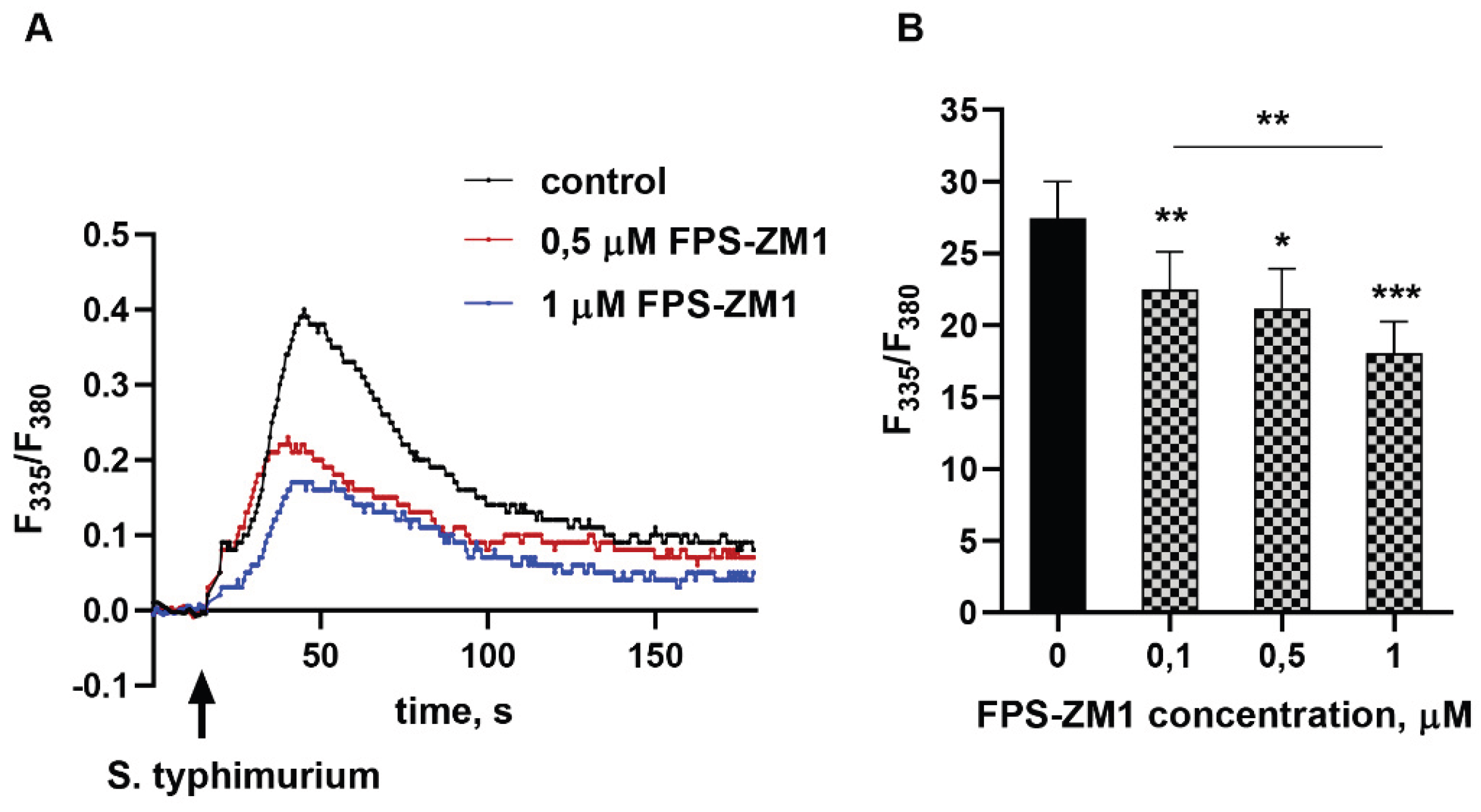

3.1. Sensory Role of RAGE in the Interaction of Neutrophils with Bacteria

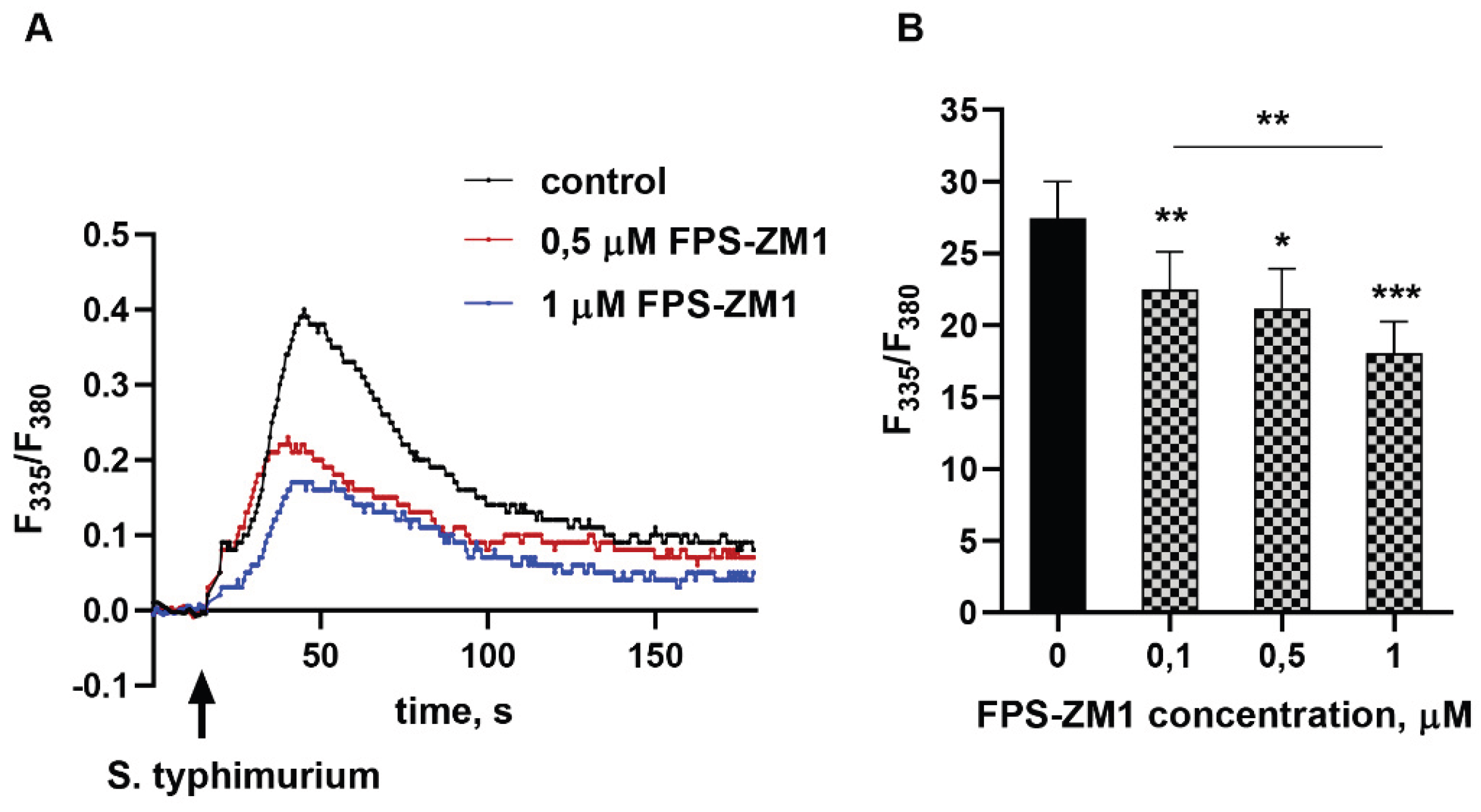

Neutrophil interaction with a pathogen or soluble stimulus almost always results in a transient increase in cytosolic calcium ion concentration. Ca

2+ acts as a universal intracellular messenger, essential for the initiation of the vast majority of effector functions of these cells. Treatment of cells with the RAGE inhibitor FPS-ZM1 immediately before addition of bacteria dose-dependently reduces the amplitude of the [Ca

2+] spike (

Figure 1).

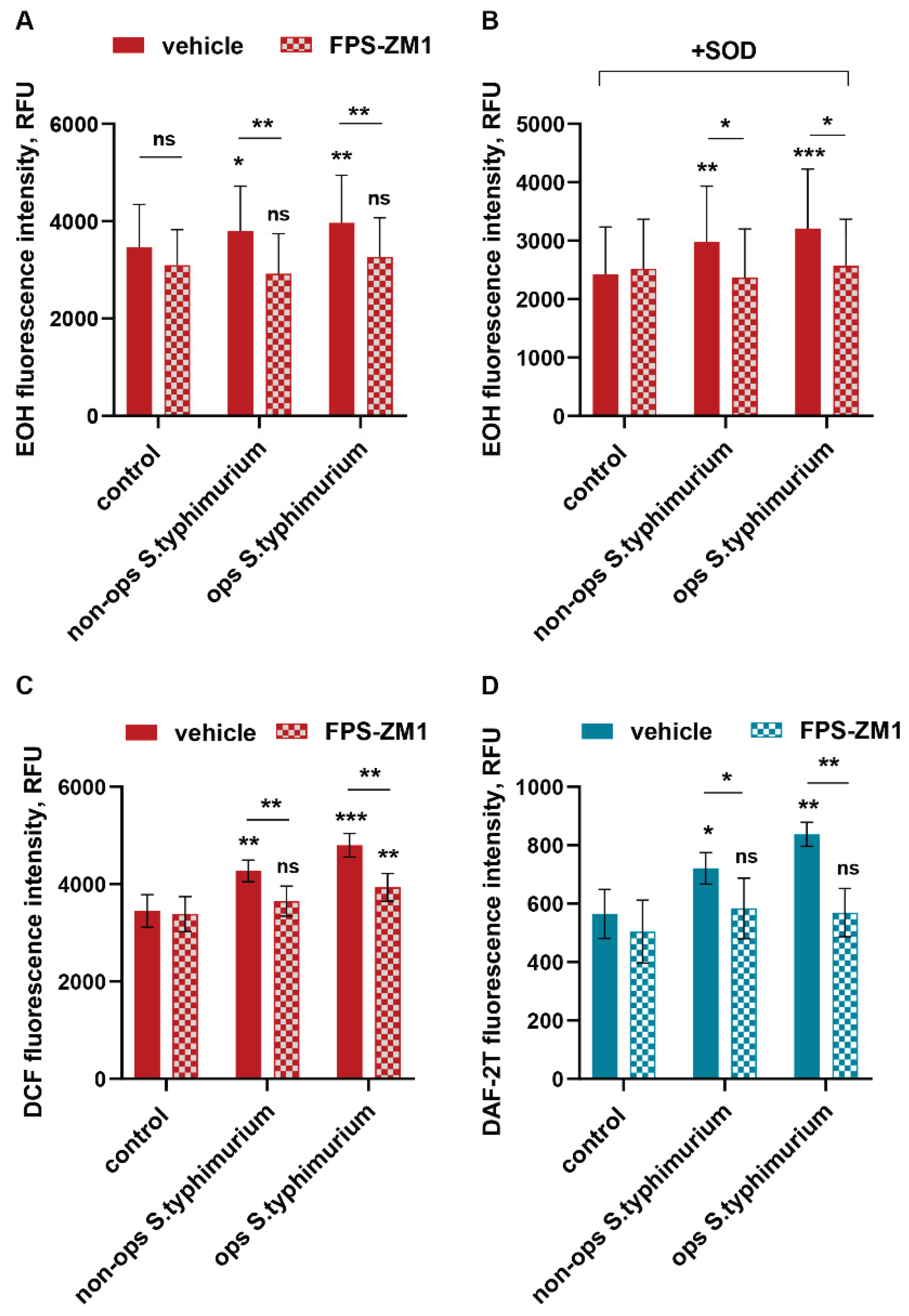

Elevated calcium levels are critical for the assembly of the multiprotein NADPH oxidase complex, both in the plasma and granule/phagosomal membranes [

29], which plays a key role in the granulocyte response to infection. Activation of NADPH oxidase in response to neutrophil contact with a pathogen, or in response to soluble stimuli, leads to the formation of large quantities of superoxide anion, which is converted into more aggressive forms of ROS. Using dihydroethidium, we showed that blocking RAGE with a specific inhibitor suppresses superoxide production (both total and intracellular, as assessed in the presence of SOD) by neutrophils interacting with bacteria (

Figure 2AB). This also leads to a decrease in the pool of intracellular oxidants, which is detected by the non-selective fluorescent probe H

2DCFH-DA (

Figure 2C). The RAGE inhibition effect was present for both non-opsonized and opsonized with donor serum bacteria, indicating the involvement of this receptor in the mechanisms of both “non-immune” (with a predominant role of pattern recognition receptors) and “immune” (principally mediated by opsonins) pathogen recognition. 2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein oxidation occurs not only due to superoxide-anion by-products (e.g. hydroxyl and peroxy radicals) but also by reactive nitric oxide derivatives: •NO and ONOO- [

30]. Neutrophilic granulocytes constitutively express inducible NO-synthase (iNOS). Nitric oxide, abundantly produced by neutrophils during their interaction with bacteria and bacterial metabolic products, in particular, with lipopolysaccharides, performs both microbicidal and regulatory functions. iNOS activation, unlike NADPH oxidase, is not a calcium-dependent process [

31]. However, by recording the fluorescence of triazolofluorescein, we showed that inhibition of RAGE prevents the activation of neutrophil iNOS in response to the addition of bacteria (

Figure 2D).

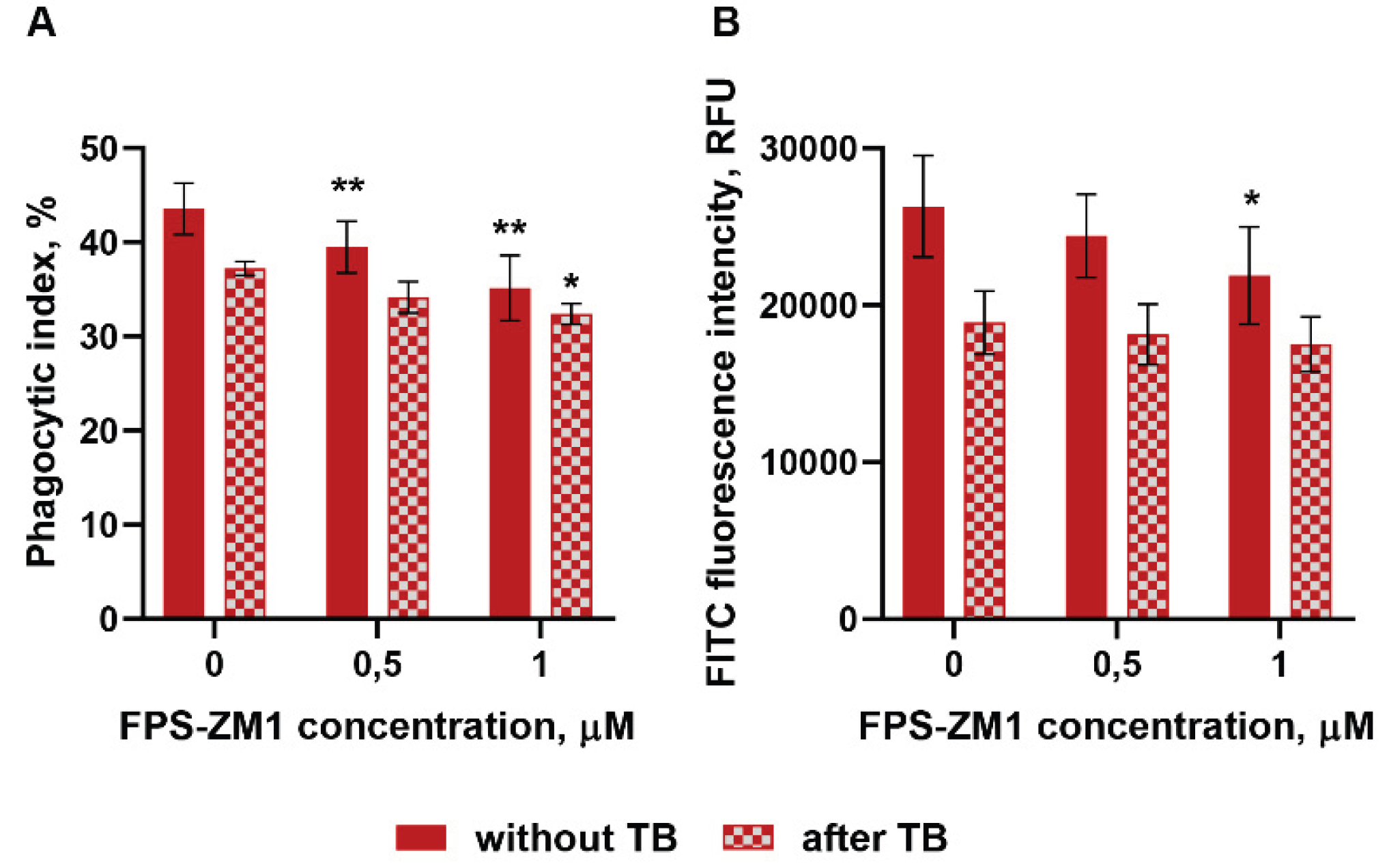

Being disassembled in resting PMNLs the cytosolic NADPH oxidase components are targeted to plasma or phagosomal membranes at the moment of action of a soluble stimulus or during phagocytosis. The RAGE receptor plays a significant role in the implementation of phagocytic activity of non-professional phagocytes [

32]. Achouiti et al. demonstrated a significant reduction in the phagocytic capacity of peripheral neutrophils isolated from RAGE

-/- knockout mice [

33]. We assessed how the phagocytic activity of human neutrophils changes under conditions of RAGE inhibition. Short-term pretreatment of cells with FPS-ZM1 reduces both the number of phagocytic neutrophils in the population (

Figure 3A) and the number of bacteria per phagocyte (

Figure 3B), affecting mainly the initial stage – pathogen attachment of to the plasma membrane (

Figure 3B, without TB).

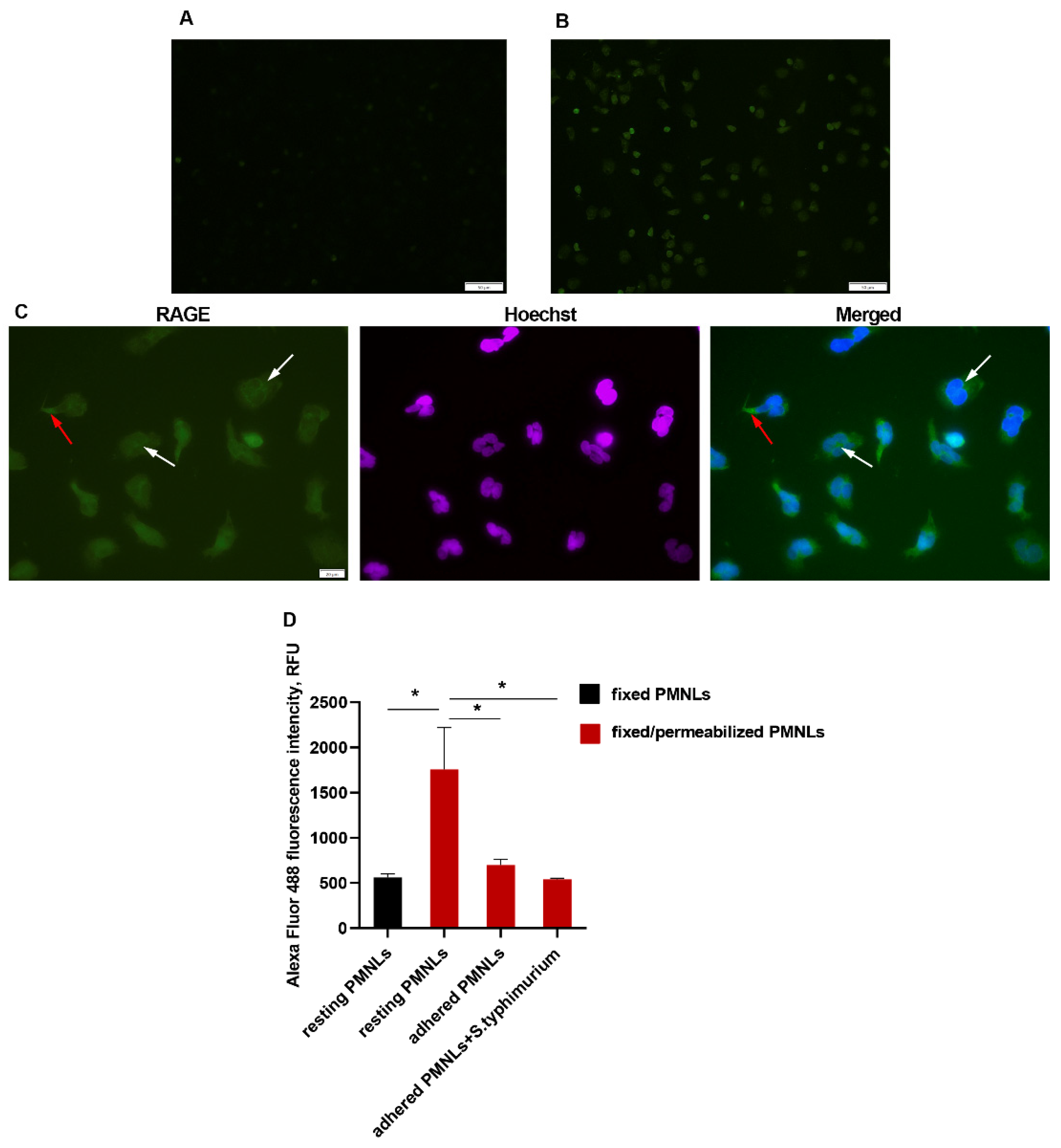

3.2. Neutrophils Express Low Membrane-Bound and Abundant Intracellular RAGE

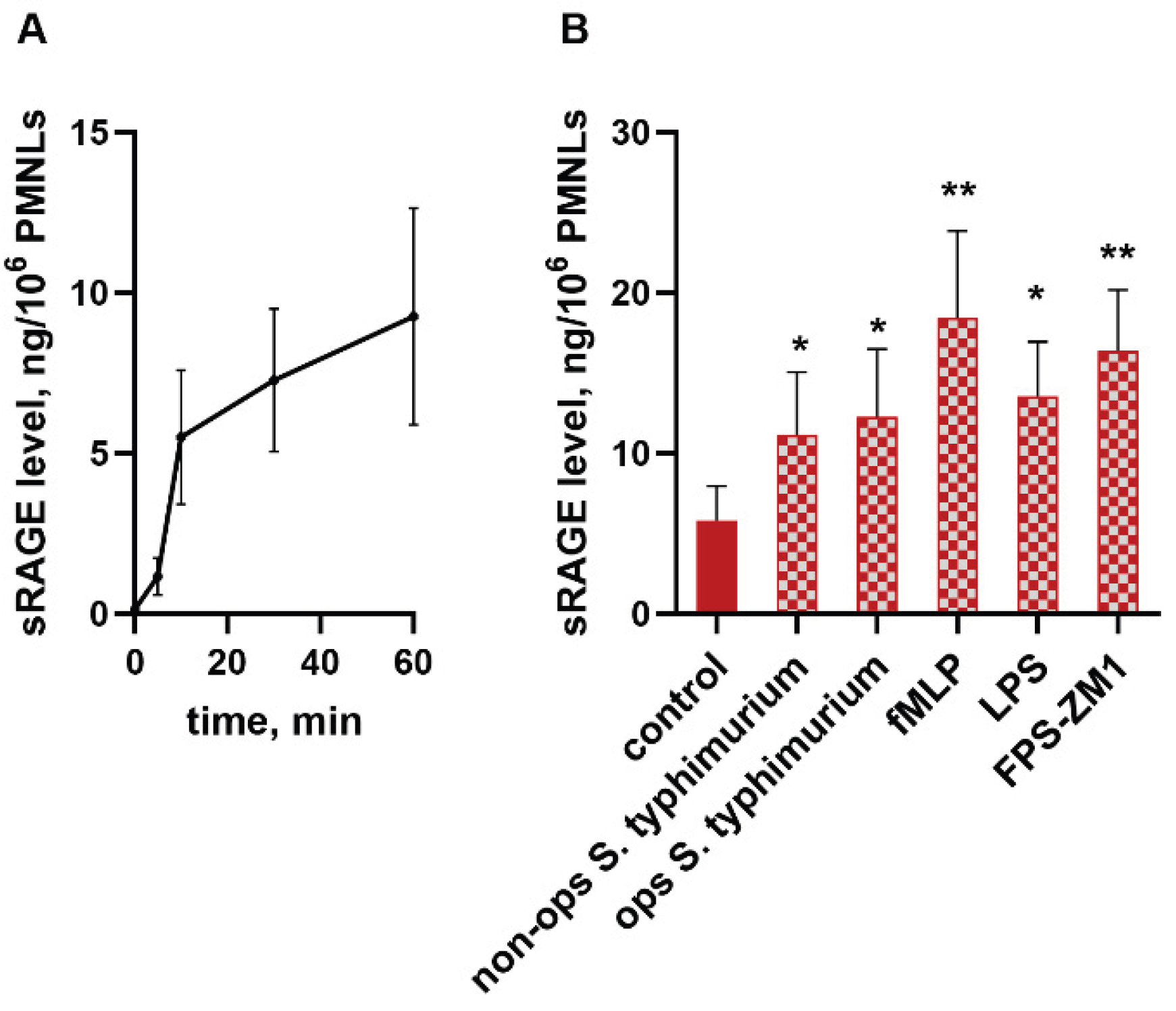

We have previously shown that interaction with S. typhimurium bacteria dramatically increases transcription of the RAGE protein in neutrophils [

34]. Moreover, it turned out that cell attachment to a fibrinogen-coated substrate is accompanied by the accumulation of sRAGE in the pericellular environment (

Figure 4). The kinetic curve of sRAGE release in control samples indicates the process to be most intensive in the first 10 minutes of incubation (

Figure 4A).

The addition of bacteria, as well as soluble bacterial-derived stimuli - lipopolysaccharide, and the chemotactic peptide fMLP, stimulates sRAGE release. A surprising finding was the ability of the FPS-ZM1 inhibitor we used in this study to dramatically enhance the formation of an extracellular sRAGE pool (

Figure 4B). There are two main pathways for the formation of soluble RAGE: shedding by membrane receptor metalloproteinases and formation by alternative splicing. To determine which mechanism is more likely to occur in neutrophils, RAGE protein was visualized using immunofluorescence microscopy. In resting neutrophils (cultured for no more than 5 minutes on a fibrinogen-coated substrate), membrane RAGE expression was extremely low (

Figure 5A). However, membrane permeabilization allows visualization of large amounts of the antigen localized within the cell (

Figure 5B,C), primarily in the perinuclear space (

Figure 5C, white arrows), most likely in the endoplasmic reticulum located there, as well as RAGE accumulation in areas of cell adhesion to the substrate (

Figure 5C, red arrows). Quantitative assessment of cellular RAGE expression by flow cytometry confirmed the microscopy results and was consistent with the ELISA data, confirming a decrease in the amount of cell-bound RAGE during adhesion and under the influence of bacteria (

Figure 5D).

4. Discussion

Data on the role of RAGE in regulating neutrophil responses to pathogens are still inconsistent, and there are clear differences between animal models and human cells, even though the RAGE protein is highly conserved across mammals [

35]. In RAGE

-/- mice, several studies showed a weakened immune response in bacterial pneumonia, including reduced neutrophil phagocytosis, while the response to intranasally delivered LPS was reported to be unchanged [

33]. At the same time, the lipid A moiety of LPS can bind to the V domain of mouse RAGE [

36], and RAGE has been implicated in LPS-induced NF-κB activation and disruption of the endothelial barrier in humans [

37]. Liliensiek et al. further showed that, although adaptive immune responses in RAGE

-/- mice are similar to those in wild-type animals, reduced mortality in septic shock suggests that RAGE signaling is a key regulator of innate immune cell activity [

38]. These observations highlight the complex and context-dependent contribution of RAGE to innate immunity.

In neutrophils from healthy donors, we found extremely low levels of RAGE at the plasma membrane in the resting state, but our data clearly show that the full-length receptor still plays an important sensory role. Inhibition of RAGE with FPS-ZM1 strongly reduced the rapid rise in cytosolic [Ca²⁺] that normally follows contact with bacteria. This early calcium signal is known to control many neutrophil effector functions, including activation of NADPH oxidase. RAGE can modulate calcium signaling through several mechanisms, including effects on transient receptor potential (TRP) channels that mediate calcium entry across the plasma membrane [

39], and these channels are important for neutrophil chemotaxis and inflammatory responses [

40]. Because Ca²⁺ depletion abolishes NADPH oxidase activity [

41], it is consistent that blocking RAGE leads to a strong decrease in both total and intracellular superoxide production in response to bacteria.

Our data also show that RAGE inhibition suppresses the formation of reactive nitrogen species in neutrophils. Although iNOS activation is considered Ca²⁺-independent [

31], FPS-ZM1 prevented the increase in NO production triggered by bacteria. This suggests that RAGE signaling contributes to the coordinated activation of both ROS and RNS pathways during neutrophil–pathogen interaction, possibly through regulators shared by NADPH oxidase and iNOS. Similar RAGE-dependent reductions in oxidative stress have been reported in animal models, where FPS-ZM1 reduced oxidative damage in neuronal tissues in the presence of excessive amyloid β, a canonical RAGE ligand. Thus, our results support the idea that RAGE is a central hub that integrates multiple signals and couples pathogen recognition to oxidative and nitrosative effector mechanisms in neutrophils.

In line with data from RAGE

-/- mice, which show reduced phagocytic activity of neutrophils [

33], we observed that short-term treatment with FPS-ZM1 decreased both the proportion of phagocytic cells and the number of bacteria internalized per cell. The strongest effect was seen at the stage of bacterial attachment to the neutrophil surface.

A key finding of our study is the dynamic regulation and dual behavior of RAGE in neutrophils. On one hand, we show that full-length RAGE acts as a sensor that supports calcium mobilization, NADPH oxidase activation, NO production, and phagocytosis. On the other hand, we observed rapid accumulation of soluble RAGE (sRAGE) in the extracellular environment when neutrophils adhere to a fibrinogen-coated surface and when they are stimulated with bacteria, LPS, or fMLP. The kinetics of this release, with a peak during the first 10 minutes, suggest that sRAGE may function as a fast negative-feedback mechanism. sRAGE can act as a decoy receptor by binding RAGE ligands in the extracellular space, thereby limiting further activation of membrane RAGE on neutrophils and other surrounding cells. The ability to form large amounts of sPAGE in response to inflammation is known for alveolar epithelial cells; however, unlike neutrophils, which, according to our observations, release it from intracellular store, the formation of sPAGE in the lungs is ensured mainly by proteolytic cleavage of FL-RAGE [

42].

The paradoxical effect of FPS-ZM1 further supports this model. While pharmacological inhibition of RAGE reduces calcium signaling, ROS/RNS production, and phagocytosis, it simultaneously amplifies the release of sRAGE. Immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry indicate that resting neutrophils contain large intracellular pools of RAGE, mainly in the perinuclear area, likely corresponding to the endoplasmic reticulum and associated secretory pathways. During adhesion and stimulation, the amount of cell-bound RAGE decreases, and sRAGE accumulates in the medium. Increased sRAGE production in the presence of FPS-ZM1 may reflect compensatory mechanism aimed at restoring RAGE signaling or at further dampening it by raising the concentration of decoy receptor.

Taken together, our findings support a model in which neutrophil RAGE has a dual role. At the plasma membrane, full-length RAGE functions as a pattern-recognition and co-receptor that helps to translate the encounter with gram-negative bacteria into key effector responses: calcium mobilization, oxidative burst, NO production, and efficient phagocytosis. At the same time, neutrophils actively generate and release sRAGE, which may limit or spatially confine RAGE-dependent signaling by sequestering ligands and by reducing the amount of membrane receptor through shedding. In this way, RAGE contributes both to the rapid activation and to the subsequent regulation of neutrophil responses, helping to balance antimicrobial defense with protection of host tissues from excessive oxidative and inflammatory damage.

Despite this study having several limitations, i.e. experiments were performed using neutrophils from healthy donors, and only one bacterial species and one pharmacological inhibitor were tested, the relative contribution of proteolytic shedding and alternative splicing to sRAGE formation in neutrophils has not been assessed, our data provide new insight into how RAGE shapes neutrophil biology. They show that targeting RAGE, for example with FPS-ZM1 or other small-molecule inhibitors, not only reduces damaging oxidative and nitrosative responses but also affects phagocytosis and sRAGE release. In clinical settings, such dual effects may be beneficial in conditions dominated by sterile inflammation and oxidative damage but could be harmful if strong antibacterial defense is required. A better understanding of the balance between membrane RAGE and sRAGE in neutrophils, and of how this balance changes in vivo during infection and in chronic diseases, will be essential for the rational design of RAGE-targeted therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.G and G.F.S.; methodology, E.A.G., G.M.V., T.V.G. and Y.M.R.; software, E.A.G.; investigation, E.A.G., S.V.N, G.M.V. and S.I.G.; resources, G.M.V, T.V.G, and Y.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.G., S.V.N., and G.F.S.; writing—review and editing, E.A.G and G.F.S.; supervision, G.F.S.; funding acquisition, G.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The experiments were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Lomonosov Moscow State University, Application # 6-h version 3, approved during the Bioethics Commission meeting # 131-d held on 31 May 2021 for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Moscow State University Development Program PNR5 for providing access to the to the SinoCite Flow cytometer and Olympus IX83 microscope.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RAGE |

receptor for advanced glycation end products |

| AGEs |

advanced glycation end products |

| HMGB1 |

high mobility group box 1 |

| PMNLs |

polymorphonuclear leukocytes |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| RNS |

reactive nitrogen species |

| fMLP |

N-Formyl-L-methionyl-L-Leucyl-L-Phenylalanine |

| LPS |

lipopolysaccharides |

References

- Sparvero, L.J.; Asafu-Adjei, D.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Amin, N.; Im, J.; Rutledge, R.; Lin, B.; Amoscato, A.A.; Zeh, H.J. , et al. RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts), RAGE ligands, and their role in cancer and inflammation. J Transl Med 2009, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikrishna, G.; Huttunen, H.J.; Johansson, L.; Weigle, B.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Rauvala, H.; Freeze, H.H. N -Glycans on the receptor for advanced glycation end products influence amphoterin binding and neurite outgrowth. J Neurochem 2002, 80, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.M.; Yan, S.D.; Yan, S.F.; Stern, D.M. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest 2001, 108, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Park, S.; Lakatta, E.G. RAGE signaling in inflammation and arterial aging. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009, 14, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raucci, A.; Cugusi, S.; Antonelli, A.; Barabino, S.M.; Monti, L.; Bierhaus, A.; Reiss, K.; Saftig, P.; Bianchi, M.E. A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). FASEB J 2008, 22, 3716–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonekura, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sakurai, S.; Petrova, R.G.; Abedin, M.J.; Li, H.; Yasui, K.; Takeuchi, M.; Makita, Z.; Takasawa, S. , et al. Novel splice variants of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products expressed in human vascular endothelial cells and pericytes, and their putative roles in diabetes-induced vascular injury. Biochem J 2003, 370, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, O.; Brett, J.; Slattery, T.; Cao, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.X.; Nagashima, M.; Lundh, E.R.; Vijay, S.; Nitecki, D. , et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a cellular binding site for amphoterin. Mediation of neurite outgrowth and co-expression of rage and amphoterin in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 25752–25761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.M.; Kirkham, M.N.; Beck, L.B.; Campbell, C.; Alcorn, H.; Bikman, B.T.; Arroyo, J.A.; Reynolds, P.R. Temporal RAGE Over-Expression Disrupts Lung Development by Modulating Apoptotic Signaling. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 14453–14463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, Y.K.; Basir, R.; Talib, H.; Tie, T.H.; Nordin, N. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and its involvement in inflammatory diseases. Int J Inflam 2013, 2013, 403460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, M.; Fujiwara, N.; Hirabayashi, S.; Ohno, H.; Iida, J.; Makita, K.; Hata, Y. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I lung alveolar cells. Genes Cells 2004, 9, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englert, J.M.; Hanford, L.E.; Kaminski, N.; Tobolewski, J.M.; Tan, R.J.; Fattman, C.L.; Ramsgaard, L.; Richards, T.J.; Loutaev, I.; Nawroth, P.P. , et al. A role for the receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2008, 172, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oczypok, E.A.; Perkins, T.N.; Oury, T.D. All the "RAGE" in lung disease: The receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is a major mediator of pulmonary inflammatory responses. Paediatr Respir Rev 2017, 23, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Fan, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. RAGE plays key role in diabetic retinopathy: a review. Biomed Eng Online 2023, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Zhang, D.D.; Wang, Y.N.; Tan, Y.Q.; Yu, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.Y. AGE/RAGE in diabetic kidney disease and ageing kidney. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 171, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinscherf, N.A.; Pehar, M. Role and Therapeutic Potential of RAGE Signaling in Neurodegeneration. Curr Drug Targets 2022, 23, 1191–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, R.; Singh, I.; Sagare, A.P.; Bell, R.D.; Ross, N.T.; LaRue, B.; Love, R.; Perry, S.; Paquette, N.; Deane, R.J. , et al. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 1377–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.X.; Yu, H.T.; Tan, Y.; Lin, Q.; Keller, B.B.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, L. Engineered cardiac tissues: a novel in vitro model to investigate the pathophysiology of mouse diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, T.; Drews-Elger, K.; Ergonul, A.; Miller, P.C.; Braley, A.; Hwang, G.H.; Zhao, D.; Besser, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, H. , et al. Targeting of RAGE-ligand signaling impairs breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Ma, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Yin, Q.; Hong, Y.; Hou, X.; Liu, X. RAGE-Specific Inhibitor FPS-ZM1 Attenuates AGEs-Induced Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress in Rat Primary Microglia. Neurochem Res 2017, 42, 2902–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, K.; Vetter, S.W.; Alam, Y.; Hasan, M.Z.; Nath, A.D.; Leclerc, E. Role of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE) and Its Ligands in Inflammatory Responses. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorci, G.; Riuzzi, F.; Giambanco, I.; Donato, R. RAGE in tissue homeostasis, repair and regeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1833, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ye, J.; Song, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, M.; Dong, J.; Lu, S. Effects of advanced glycation end products on neutrophil migration and aggregation in diabetic wounds. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 12143–12159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insuela, D.; Coutinho, D.; Martins, M.; Ferrero, M.; Carvalho, V. Neutrophil Function Impairment Is a Host Susceptibility Factor to Bacterial Infection in Diabetes. In Cells of the Immune System, 2020; 10.5772/intechopen.86600.

- Collison, K.S.; Parhar, R.S.; Saleh, S.S.; Meyer, B.F.; Kwaasi, A.A.; Hammami, M.M.; Schmidt, A.M.; Stern, D.M.; Al-Mohanna, F.A. RAGE-mediated neutrophil dysfunction is evoked by advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2002, 71, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; A, X.; Wang, Y.; Cui, W.; Li, H.; Du, J. S100a8/a9 released by CD11b+Gr1+ neutrophils activates cardiac fibroblasts to initiate angiotensin II-Induced cardiac inflammation and injury. Hypertension 2014, 63, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandrov, D.A.; Zagryagskaya, A.N.; Pushkareva, M.A.; Bachschmid, M.; Peters-Golden, M.; Werz, O.; Steinhilber, D.; Sud'ina, G.F. Cholesterol and its anionic derivatives inhibit 5-lipoxygenase activation in polymorphonuclear leukocytes and MonoMac6 cells. FEBS J 2006, 273, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshavariya, H.M.; Dusting, G.J.; Selemidis, S. Analysis of dihydroethidium fluorescence for the detection of intracellular and extracellular superoxide produced by NADPH oxidase. Free Radic Res 2007, 41, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerknes, R.; Bassoe, C.F. Phagocyte C3-mediated attachment and internalization: flow cytometric studies using a fluorescence quenching technique. Blut 1984, 49, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granfeldt, D.; Samuelsson, M.; Karlsson, A. Capacitative Ca2+ influx and activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst. Different regulation of plasma membrane- and granule-localized NADPH-oxidase. J Leukoc Biol 2002, 71, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiniers, M.J.; van Golen, R.F.; Bonnet, S.; Broekgaarden, M.; van Gulik, T.M.; Egmond, M.R.; Heger, M. Preparation and Practical Applications of 2',7'-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein in Redox Assays. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 3853–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, F.; Carey, L.B.; Sun, C.; Ling, K.; Tachikawa, H.; Fujita, M.; Gao, X.D.; Nakanishi, H. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) mediates phagocytosis in nonprofessional phagocytes. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achouiti, A.; de Vos, A.F.; van 't Veer, C.; Florquin, S.; Tanck, M.W.; Nawroth, P.P.; Bierhaus, A.; van der Poll, T.; van Zoelen, M.A. Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE) Serves a Protective Role during Klebsiella pneumoniae - Induced Pneumonia. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0141000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viryasova, G.M.; Golenkina, E.A.; Hianik, T.; Soshnikova, N.V.; Dolinnaya, N.G.; Gaponova, T.V.; Romanova, Y.M.; Sud’ina, G.F. Magic Peptide: Unique Properties of the LRR11 Peptide in the Activation of Leukotriene Synthesis in Human Neutrophils. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterenczak, K.A.; Nolte, I.; Murua Escobar, H. RAGE splicing variants in mammals. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 963, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Harashima, A.; Saito, H.; Tsuneyama, K.; Munesue, S.; Motoyoshi, S.; Han, D.; Watanabe, T.; Asano, M.; Takasawa, S. , et al. Septic shock is associated with receptor for advanced glycation end products ligation of LPS. J Immunol 2011, 186, 3248–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Guo, X.; Huang, X.; Huang, Q. RAGE Plays a Role in LPS-Induced NF-kappaB Activation and Endothelial Hyperpermeability. Sensors (Basel) 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liliensiek, B.; Weigand, M.A.; Bierhaus, A.; Nicklas, W.; Kasper, M.; Hofer, S.; Plachky, J.; Grone, H.J.; Kurschus, F.C.; Schmidt, A.M. , et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) regulates sepsis but not the adaptive immune response. J Clin Invest 2004, 113, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.X.; Thompson, C.B. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najder, K.; Musset, B.; Lindemann, O.; Bulk, E.; Schwab, A.; Fels, B. The function of TRP channels in neutrophil granulocytes. Pflugers Arch 2018, 470, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, J.; Bueb, J.L.; Tolle, F.; Brechard, S. Calcium signaling and regulation of neutrophil functions: Still a long way to go. J Leukoc Biol 2020, 107, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonchuk, J.G.; Silverman, E.K.; Bowler, R.P.; Agusti, A.; Lomas, D.A.; Miller, B.E.; Tal-Singer, R.; Mayer, R.J. Circulating soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) as a biomarker of emphysema and the RAGE axis in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015, 192, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Inhibition of RAGE suppresses the transient increase in neutrophil cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration induced by cell-bacteria interaction. Fura-2 AM-loaded PMNLs were preincubated for 5 min without additives (control (A) or zero FPS-ZM1 concentration (B)) or with FPS-ZM1 in concentrations indicated. Then non opsonized S. typhimurium bacteria (MOI ~20) were injected automatically. Fluorescence intensities (335 nm/510 nm and 380 nm/510 nm) began to be recorded before bacteria injection, and measurements continued for 3 min after. A. Typical curves of [Ca2+]i changes (ratio F335/F380) after adding bacteria to untreated (black) and pre-treated with FPS-ZM1 in indicated concentrations (red, blue) PMNLs. B. AUC (means±SEM) for a three-minutes interval after bacteria addition to untreated (solid black) or pre-incubated with FPS-ZM1 in concentrations indicated (black and grey) PMNLs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for pair of data indicated or compared to control (zero FPS-ZM1) value; N=3.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of RAGE suppresses the transient increase in neutrophil cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration induced by cell-bacteria interaction. Fura-2 AM-loaded PMNLs were preincubated for 5 min without additives (control (A) or zero FPS-ZM1 concentration (B)) or with FPS-ZM1 in concentrations indicated. Then non opsonized S. typhimurium bacteria (MOI ~20) were injected automatically. Fluorescence intensities (335 nm/510 nm and 380 nm/510 nm) began to be recorded before bacteria injection, and measurements continued for 3 min after. A. Typical curves of [Ca2+]i changes (ratio F335/F380) after adding bacteria to untreated (black) and pre-treated with FPS-ZM1 in indicated concentrations (red, blue) PMNLs. B. AUC (means±SEM) for a three-minutes interval after bacteria addition to untreated (solid black) or pre-incubated with FPS-ZM1 in concentrations indicated (black and grey) PMNLs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for pair of data indicated or compared to control (zero FPS-ZM1) value; N=3.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of RAGE effectively prevents the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in neutrophils interacting with bacteria. DHE-stained without (A) or with SOD (B), or H2DCF-DA-loaded (C), or DAF-2 DA-loaded (D) PMNLs were pre-incubated for 5 min without additives (solid pattern) or in the presence of 1 µM FPS-ZM1 (mesh pattern). Then non opsonized or opsonized S. typhimurium bacteria (MOI ~20) were added to all probes except control ones. Presented are means ± SEM of fluorescence intensity values measured at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for pairs of data indicated or compared to corresponding control values.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of RAGE effectively prevents the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in neutrophils interacting with bacteria. DHE-stained without (A) or with SOD (B), or H2DCF-DA-loaded (C), or DAF-2 DA-loaded (D) PMNLs were pre-incubated for 5 min without additives (solid pattern) or in the presence of 1 µM FPS-ZM1 (mesh pattern). Then non opsonized or opsonized S. typhimurium bacteria (MOI ~20) were added to all probes except control ones. Presented are means ± SEM of fluorescence intensity values measured at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for pairs of data indicated or compared to corresponding control values.

Figure 3.

The RAGE receptor is involved in the implementation of phagocytic activity of neutrophils. PMNLs were pre-incubated for without additives or with FPS-ZM1 followed by opsonized FITC-labeled bacteria S. typhimurium addition for 10 min. Presented are pooled flow cytometry data (means ± SEM) with numbers of phagocytizing (i.e., FITC-positive cells), as a percentage of the total number of PMNLs in the sample (A) and fluorescence intensities of FITC-positive subpopulations (B) without (solid pattern) or after (mesh pattern) TB quenching. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to corresponding control values; N=3.

Figure 3.

The RAGE receptor is involved in the implementation of phagocytic activity of neutrophils. PMNLs were pre-incubated for without additives or with FPS-ZM1 followed by opsonized FITC-labeled bacteria S. typhimurium addition for 10 min. Presented are pooled flow cytometry data (means ± SEM) with numbers of phagocytizing (i.e., FITC-positive cells), as a percentage of the total number of PMNLs in the sample (A) and fluorescence intensities of FITC-positive subpopulations (B) without (solid pattern) or after (mesh pattern) TB quenching. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to corresponding control values; N=3.

Figure 4.

Neutrophil adhesion to a fibrinogen-coated substrate, by itself and in the presence of stimuli, is accompanied by intense release of sRAGE into the extracellular space. PMNLs were incubated for desired period of time (5 – 60 min) (A) or 30 min (B) in fibrinogen-coated wells without additives (A; B – control) or in the presence of non-opsonized or opsonized S. typhimurium (MOI ~ 20), 0.01 µM fMLP, 100 ng/mL LPS or 1 µM FPS-ZM1 (as indicated on B). At the end of the incubation, the concentration of sRAGE in the supernatants was determined by ELISA. The dynamics of the increase in the concentration of free RAGE in untreated cells over time is presented on A. Average values (means ± SEM) of sRAGE content in PMNLs supernatants after 30 min of cultivation are presented on B (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to control value, N=5).

Figure 4.

Neutrophil adhesion to a fibrinogen-coated substrate, by itself and in the presence of stimuli, is accompanied by intense release of sRAGE into the extracellular space. PMNLs were incubated for desired period of time (5 – 60 min) (A) or 30 min (B) in fibrinogen-coated wells without additives (A; B – control) or in the presence of non-opsonized or opsonized S. typhimurium (MOI ~ 20), 0.01 µM fMLP, 100 ng/mL LPS or 1 µM FPS-ZM1 (as indicated on B). At the end of the incubation, the concentration of sRAGE in the supernatants was determined by ELISA. The dynamics of the increase in the concentration of free RAGE in untreated cells over time is presented on A. Average values (means ± SEM) of sRAGE content in PMNLs supernatants after 30 min of cultivation are presented on B (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to control value, N=5).

Figure 5.

A-C Membrane and intracellular RAGE expression in resting neutrophils. A. Membrane RAGE expression (green) by resting PMNLs (non-permeabilized cells). B,C. Immunofluorescence images (RAGE, both intracellular and membrane, – green, nuclei – blue) of resting PMNLs after permeabilization. D. PMNLs (106 cells per probe) without any treatment (resting PMNLs) or after 30 min incubation on fibrinogen-coated substrate without additives or with S. typhimurium bacteria (MOI ~ 20) (adhered PMNLs) were collected, fixed with 2.5 % PFA and permeabilized (except “resting PMNLs” sample presented in black) followed immunofluorescence RAGE staining and analysis by flow cytometry. Presented are average fluorescence intensity values (means ± SEM). *p < 0.05 for pairs of data indicated, N=3.

Figure 5.

A-C Membrane and intracellular RAGE expression in resting neutrophils. A. Membrane RAGE expression (green) by resting PMNLs (non-permeabilized cells). B,C. Immunofluorescence images (RAGE, both intracellular and membrane, – green, nuclei – blue) of resting PMNLs after permeabilization. D. PMNLs (106 cells per probe) without any treatment (resting PMNLs) or after 30 min incubation on fibrinogen-coated substrate without additives or with S. typhimurium bacteria (MOI ~ 20) (adhered PMNLs) were collected, fixed with 2.5 % PFA and permeabilized (except “resting PMNLs” sample presented in black) followed immunofluorescence RAGE staining and analysis by flow cytometry. Presented are average fluorescence intensity values (means ± SEM). *p < 0.05 for pairs of data indicated, N=3.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).