Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Principle Formulations and Calculations

2.1. Principal and General Relations

2.2. Comparison with the Experimental Data

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. The Action

3.2. The Hamiltonian

3.3. Field Equations

3.4. The Particle’s Spin

3.5. Multi-Particle System

4. Atomic Energy Spectrum

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pires, C.A.D.S.; Rodrigues Da Silva, P.S. Scalar scenarios contributing to (g-2)μ with enhanced Yukawa couplings. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 64, 117701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Ureña, M.A.; Hernández-Tomé, G.; Tavares-Velasco, G. Anomalous magnetic and weak magnetic dipole moments of the τ lepton in the simplest little Higgs model. Eur. Phys. J. C 2017, 77, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Conto, G.; Pleitez, V. Electron and muon anomalous magnetic dipole moment in a 3-3-1 model. J. High Energ. Phys. 2017, 2017, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, C.; Patra, S.; Pritimita, P.; Senapati, S.; Yajnik, U.A. Neutrino mass, mixing and muon g-2 explanation in U(1)Lμ-Lτ extension of left-right theory. J. High Energ. Phys. 2020, 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calibbi, L.; López-Ibáñez, M.L.; Melis, A.; Vives, O. Muon and electron g-2 and lepton masses in flavor models. J. High Energ. Phys. 2020, 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutgeb, J.; Mager, J.; Rebhan, A. Holographic QCD and the muon anomalous magnetic moment. Eur. Phys. J. C 2021, 81, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Sáez, B.; Ghorbani, K. Singlet scalars as dark matter and the muon (g-2) anomaly. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 823, 136750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadeddu, M.; Cargioli, N.; Dordei, F.; Giunti, C.; Picciau, E. Muon and electron g-2 and proton and cesium weak charges implications on dark Zd models. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, L011701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.T.; Nha, N.H.T.; Nguyen, T.P.; Phuong, L.T.T.; Hue, L.T. Decays h→eaeb, eb→eaγ, and (g-2)e,μ in a 3-3-1 model with inverse seesaw neutrinos. PTEP 2022, 2022, 093B05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya, K.; Bashir, A.; Miramontes, A.S.; Roig, P. Dyson-Schwinger equations and the muon g-2. Supl. Rev. Mex. Fis. 2022, 3, 020709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Iguro, S.; Kitahara, T.; Lang, M.S. Current status of the muon g-2 interpretations within two-Higgs-doublet models. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 115012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, D. Muon anomalous magnetic dipole moment in a low scale type I see-saw model. Nucl. Phys. B 2023, 994, 116306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Meng, L.; Yue, Y. Electron and muon anomalous magnetic moments in the Z3-NMSSM. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 035043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, P. Nonlocal QED and lepton g-2 anomalies. Eur. Phys. J. C 2024, 84, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Geng, C.Q.; Wu, J. Unitarity bounds on the massive spin-2 particle explanation of muon g-2 anomaly. Eur. Phys. J. C 2024, 84, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdelyi, B.A.; Gröber, R.; Selimovic, N. Probing New Physics with the Electron Yukawa coupling. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breit, G. Does the Electron Have an Intrinsic Magnetic Moment? Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 984–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusch, P.; Foley, H.M. The Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Phys. Rev. 1948, 74, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. On Quantum-Electrodynamics and the Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Phys. Rev. 1948, 73, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusch, P. The Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Nobel Lecture 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.L.; Marciano, W.J. Lepton Dipole Moments; Vol. 20, Advanced Series on Directions in High Energy Physics, World Scientific, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Hanneke, D.; Fogwell, S.; Gabrielse, G. New Measurement of the Electron Magnetic Moment and the Fine Structure Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Myers, T.; Sukra, B.; Gabrielse, G. Measurement of the Electron Magnetic Moment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 071801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. Quantum Electrodynamics. II. Vacuum Polarization and Self-Energy. Phys. Rev. 1949, 75, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karplus, R.; Kroll, N.M. Fourth-Order Corrections in Quantum Electrodynamics and the Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Phys. Rev. 1950, 77, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataev, A.L. Analytical eighth-order light-by-light QED contributions from leptons with heavier masses to the anomalous magnetic moment of electron. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 013010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Heinzl, T. Measuring vacuum polarization with high-power lasers. HPLSE 2016, 4, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morte, M.D.; Francis, A.; Gülpers, V.; Herdoíza, G.; Von Hippel, G.; Horch, H.; Jäger, B.; Meyer, H.B.; Nyffeler, A.; Wittig, H. The hadronic vacuum polarization contribution to the muon g-2 from lattice QCD. J. High Energ. Phys. 2017, 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, A.; Kamleh, W.; Young, R.; Zanotti, J.; Horsley, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Perlt, H.; Rakow, P.; Schierholz, G.; Stüben, H. Anomalous magnetic moment of the muon with dynamical QCD+QED. EPJ Web Conf. 2020, 245, 06035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérardin, A. The anomalous magnetic moment of the muon: status of lattice QCD calculations. Eur. Phys. J. A 2021, 57, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelko, S.; Nikolskii, A.; Voronin, V. Soft gluon fields and anomalous magnetic moment of muon. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 2022, 49, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, D.; Reyes, E.; Fazio, R. Hadronic Light-by-Light Corrections to the Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment. Particles 2024, 7, 327–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, S. Calculation of lepton magnetic moments in quantum electrodynamics: A justification of the flexible divergence elimination method. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 036012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporta, S.; Remiddi, E. Analytic QED Calculations of the Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Electron. In Advanced Series on Directions in High Energy Physics; World Scientific, 2009; Vol. 20, pp. 119–156. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M. The anomalous magnetic moment of the electron. Contemp. Phys. 2009, 50, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Nio, M. Tenth-order electron anomalous magnetic moment: Contribution of diagrams without closed lepton loops. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 033006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Nio, M. Theory of the Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Electron. Atoms 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, F. The 47 years of muon g-2. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2004, 52, 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.P.; De Rafael, E.; Lee Roberts, B. Muon (g-2): experiment and theory. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2007, 70, R03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jegerlehner, F.; Nyffeler, A. The muon g-2. Phys. Rep. 2009, 477, 1–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegerlehner, F. The Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Muon; Vol. 274, Springer Tracts in Modern Physics, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logashenko, I.B.; Eidelman, S.I. Anomalous magnetic moment of the muon. Phys.-Usp. 2018, 61, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Asmussen, N.; Benayoun, M.; Bijnens, J.; Blum, T.; Bruno, M.; Caprini, I.; Carloni Calame, C.; Cé, M.; Colangelo, G.; et al. The anomalous magnetic moment of the muon in the Standard Model. Phys. Rep. 2020, 887, 1–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzi, A.; Khaw, K.S.; Yoshioka, T. Muon g-2: A review. Nucl. Phys. B 2022, 975, 115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillard, D.P.; Albahri, T.; Allspach, D.; Anisenkov, A.; Badgley, K.; Baeßler, S.; Bailey, I.; Bailey, L.; Baranov, V.A.; Barlas-Yucel, E.; et al. Measurement of the Positive Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment to 0.20 ppm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 161802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillard, D.; Albahri, T.; Allspach, D.; Anisenkov, A.; Badgley, K.; Baeßler, S.; Bailey, I.; Bailey, L.; Baranov, V.; Barlas-Yucel, E.; et al. Detailed report on the measurement of the positive muon anomalous magnetic moment to 0.20 ppm. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 032009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.J. Divergence of Perturbation Theory in Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 631–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, I. From Euler’s play with infinite series to the anomalous magnetic moment. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsanyi, S.; Fodor, Z.; Guenther, J.N.; Hoelbling, C.; Katz, S.D.; Lellouch, L.; Lippert, T.; Miura, K.; Parato, L.; Szabo, K.K.; et al. Leading hadronic contribution to the muon magnetic moment from lattice QCD. Nature 2021, 593, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athron, P.; Fowlie, A.; Lu, C.T.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, B. Hadronic uncertainties versus new physics for the W boson mass and Muon g-2 anomalies. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crivellin, A.; Mellado, B. Anomalies in particle physics and their implications for physics beyond the standard model. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, M. Exact classical approach to the electron’s self-energy and anomalous g-factor. Europhys. Lett. 2024, 147, 20001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, M. Yukawa Cut-Offs to Model the Muon Self-Interaction. Contemp. Math. 2025, 6, 4762–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, R.; Aoyama, T.; Balzani, E.; Bashir, A.; Benton, G.; Bijnens, J.; Biloshytskyi, V.; Blum, T.; Boito, D.; Bruno, M.; et al. The anomalous magnetic moment of the muon in the Standard Model: an update. Phys. Rep. 2025, 1143, 1–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillard, D.P.; Albahri, T.; Allspach, D.; Annala, J.; Badgley, K.; Baeßler, S.; Bailey, I.; Bailey, L.; Barlas-Yucel, E.; Barrett, T.; et al. Measurement of the Positive Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment to 127 ppb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 135, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. ; Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2018 results: VI. Cosmological parameters. A & A 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATRIN Collaboration. ; Aker, M.; Batzler, D.; Beglarian, A.; Behrens, J.; Beisenkötter, J.; Biassoni, M.; Bieringer, B.; Biondi, Y.; Block, F.; et al. Direct neutrino-mass measurement based on 259 days of KATRIN data. Science 2025, 388, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2018 CODATA Value: electron mass and muon mass. The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST, 2019.

- Aoyama, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Nio, M. Tenth-Order QED Contribution to the Electron g-2 and an Improved Value of the Fine Structure Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 111807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labzowsky, L.N.; Goidenko, I. Chapter 8 QED theory of atoms. In Theoretical and Computational Chemistry; Elsevier, 2002; Vol. 11, pp. 401–467. [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, K.; Vainshtein, A. Theory of the Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment; Vol. 216, Springer Tracts in Modern Physics, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Özgüven, Y.; Billur, A.A.; İnan, S.C.; Bahar, M.K.; Köksal, M. Search for the anomalous electromagnetic moments of tau lepton through electron-photon scattering at CLIC. Nucl. Phys. B 2017, 923, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. Classical theory of radiating electrons. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1938, 167, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milonni, P.W. The Quantum Vacuum: An Introduction to Quantum Electrodynamics; Elsevier Science: San Diego, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 4 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dodig, H. Direct Derivation of Liénard-Wiechert Potentials, Maxwell’s Equations and Lorentz Force from Coulomb’s Law. Mathematics 2021, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, W.; Reinhardt, J. Field Quantization; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C.; Dupont-Roc, J.; Grynberg, G. Photons and atoms: Introduction to quantum electrodynamics; Physics textbook, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison, I.J.R.; Hey, A.J.G. Gauge theories in particle physics: a practical introduction, 5th ed ed.; CRC press: Boca Raton, Fla, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D.J.; Schroeter, D.F. Introduction to quantum mechanics, 3rd ed ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C.; Diu, B.; Laloë, F. Quantum mechanics. Volume 1: Basic concepts, tools, and applications, 2 ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C.; Diu, B.; Laloë, F. Quantum mechanics. Volume 2: Angular momentum, spin, and approximation methods, 2 ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, 2020. [Google Scholar]

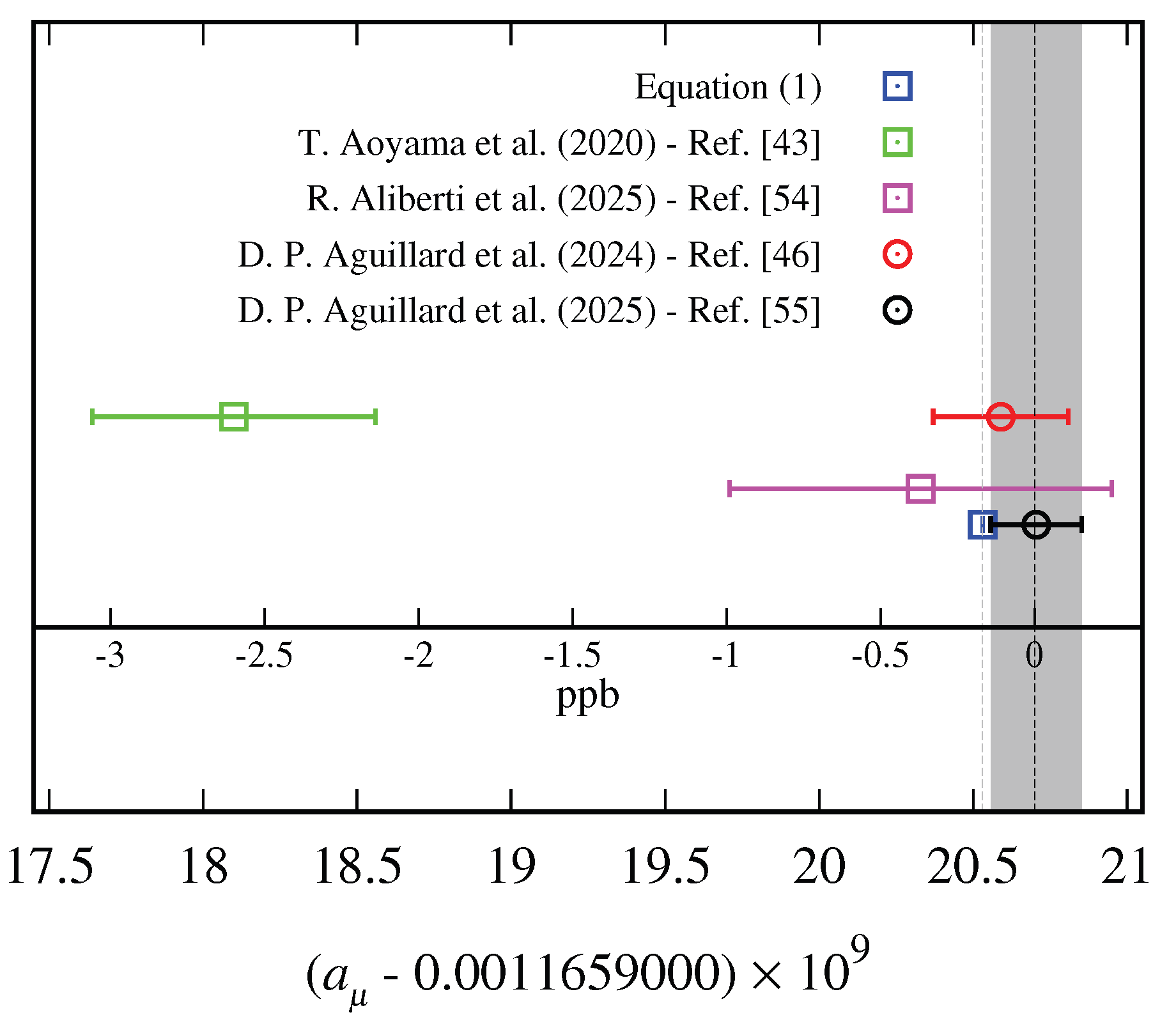

| Approach | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Exact | Equation (1) | |

| SM | R. Aliberti et al. [54] | |

| FNAL (Run-1-6) | D. P. Aguillard et al. [55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).