Introduction

Background and Context

Since technological development has changed how people communicate. In this process, many new social media platforms, such as TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram, have gained many users and improved impact in digital marketing. These platforms have become increasingly popular. And their influence is growing which shapes how users think and act. Ten years ago, there were no recommendation systems or AI driven content platforms. Today algorithmic recommendation systems and AI driven content platforms decide what the user sees. The fast growth of the platforms reshape user buying habits by digital communication. This trend shift makes digital marketing more important. People have more exploration in digital marketing in recent years.

Social media has become a major communication tool, and it strongly affects consumer decision-making and ignites the user’s desire to purchase. Social media can amply marketing effects and push a surge in digital marketing investment, with global social-media advertising expected to reach $276.72 billion by 2025 (Statista, 2024). At the same time, platforms support highly interactive user participation. In Chipotle’s #GuacDance challenge activity, user created more than 250,000 videos and receive 430 million views, substantially increasing engagement and brand visibility (Williams, 2019).

Problem Statement

Since social media provides access to a board information. It can also expose users, especially younger audiences, to persuasive or misleading content. Teenagers and children are not mature intellectually and psychologically. They are more easily influenced by trends and engaging online content. Research shows that up to 95% of adolescents ages 13–17 use at least one social media platform (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023), and 40% of children ages 8–12 do as well (Office of the Surgeon General, 2023).

Meanwhile, empirical studies show that young adults react strongly to product-related content online. One research indicates that looking at tobacco-related content can spark curiosity and can push audience to try e-cigarettes (Lee et al. 2021). The increased exposure to e-cigarette-related content posted by online influencers is related to the increased frequency of e-cigarette use among young people and their more positive views on nicotine. (Vogel et al., 2024). Teenagers also find vaping imagery socially appealing, with positive feelings increasing their likelihood of trying these products (Venrick et al., 2022). Thus, these findings suggest that online content can change attitudes and behavior of users. And they emphasized the importance of understanding how textual cues influence online communication.

Purpose of the Study

To reduce the large amount annotation for spotting harmful content, this project uses a large language model (LLM) to predict hashtags based on texture data. After comparing the LLM predictions with the human-assigned hashtags, the result can be split to match and mismatch. This study will run logistic regression based on the sentiment features, like sentiment scores. The regression analysis helps the study to figure out whether sentiment cues can explain the mismatch. It can use coefficient of sentiment features to find language patterns that can affect hashtag accuracy. If useful indicators are found, these sentiment features could be built into future LLMs to help them detect harmful content more effectively and with less human input.

This study analyzes YouTube video descriptions to assess whether sentiment features— specifically LIWC and VADER scores—help explain mismatches between human-assigned hashtags and LLM-predicted hashtags. By analyzing the emotional tone, motivational cues, and affective intensity in each description, the study tests whether these sentiment signals influence the model’s ability to infer the intended hashtag category. The analysis investigates whether affective language contributes to explaining mismatch between human and LLM-generated labels. An LLM classifier is used to generate predicted labels, while sentiment features are used solely to evaluate whether they predict mismatch versus match outcomes. The goal is to determine whether emotional or motivational language meaningfully contributes to discrepancies in hashtag selection, thereby informing how linguistic signals may affect both algorithmic classification and human labeling in the context of harmful content detection.

Although prior research demonstrates that exposure to online content can shape behavior, we still know little about how individual words or phrases show harmful meaning in social- media text. Platforms are different in content structure and algorithmic delivery, creating variability in how harmful content is presented and amplified (Narayanan, 2023). From experimental results, they also show that algorithm-driven mechanism significantly influences user’s engagement and exposure (Guess et al., 2023). To identify harmful content, especially through textual elements, such as descriptions and hashtags, remains challenging. The decision processes behind how creators choose hashtags and how certain language may hide or signal harmful intent are still poorly understood. This mechanism is particularly important for content, especially for tabaco-related content. Margolis et al. (2018) reports that increasing exposure to e-cigarette advertisement is connected to curiosity among the youth. It also raised susceptibility among the youth. Other studies show that young people who expose to tobacco- or e-cigarette related content on social media have higher odds of e-cigarette susceptibility and initiation (Lee et al., 2023; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024).

Understanding the linguistic signals embedded in creator texture metadata can enhance public-health interventions and improve algorithmic detection of harmful content.

Literature Review

Linguistic and Affective Factors Underlying Discrepancies

Understanding why large language models (LLMs) generate labels that differ from those chosen by human annotators requires tools that can systematically capture emotional tone, linguistic cues, and psychological meaning within text. Two of the most widely used tools—LIWC and VADER—provide interpretable affective and linguistic features that can reveal patterns underlying LLM–human disagreement.

LIWC provides a framework, based on psychology, to detect linguistic signals. It includes cognitive, emotional, and motivational states etc.... Its categories—such as affective processes, reward, anxiety, or cognitive mechanism words—capture subtler linguistic patterns that may influence how humans interpret meaning (Boyd et al., 2022). When used to compare LLM and human labels, LIWC can highlight whether discrepancies emerge in texts containing heightened emotional language, conflicting motivational cues, or ambiguous stance-related signals. For example, mismatches may occur more often in descriptions with high emotional complexity or mixed emotional categories, which LIWC identifies reliably even when LLMs do not.

VADER, designed specifically for social-media text, captures polarity and intensity while handling slang, capitalization, emojis, and informal grammar (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014). Prior research shows that VADER performs better than traditional lexicons on short online posts but still fails when sarcasm, implicit affect, or cultural meaning shape sentiment (Reagan et al., 2017). These same contexts also produce high LLM–human disagreement—making VADER’s polarity and intensity scores useful indicators of whether mismatches arise from ambiguous or low-intensity emotional content. When VADER scores fall in a mid-range (e.g., slightly positive or slightly negative), LLMs are more likely to diverge from human label choices.

Integrating LIWC and VADER features into discrepancy analysis also helps interpret LLM errors in a transparent manner. Studies comparing lexicon-based outputs with machine-learning predictions show that combining dictionary features with model assessments improves the ability to explain where and why misclassification occurs—especially in emotionally ambiguous text (Reagan et al., 2017; Öhman & Persson, 2021). LIWC and VADER serve as diagnostic tools: if a human-assigned hashtag reflects emotional stance or community meaning that the LLM misses, these lexicons can reveal the underlying linguistic and psychological cues associated with discrepancy.

Finally, human factors further contribute to mismatch. Because LIWC and VADER quantify emotion at the lexical level, they provide stable measurements where human interpretations differ, helping identify whether discrepancies arise from LLM limitations or from inherent ambiguity in the text itself. In summary, prior research indicates that LIWC and VADER offer complementary, interpretable metrics that help diagnose why LLM-generated labels diverge from human-assigned ones. By quantifying emotional tone, intensity, and psychological cues, these tools provide a transparent way to analyze the linguistic sources of disagreement and support more reliable evaluation of LLM affective performance.

Limitations and Research Gaps

Although LIWC and VADER provide interpretable sentiment indicators, prior research consistently shows that lexicon-based tools struggle to capture the subtle emotional cues, informal expressions, and culturally shaped language common in social-media text (Öhman & Persson, 2021). These challenges are same as issues identified in recent sentiment-analysis research. Jim et al. (2024) review modern NLP sentiment systems and show that both lexicon-based and deep-learning approaches face difficulties with implicit sentiment, sarcasm, and culturally embedded language. These challenges are mirrored in behavioral research, which also documents similar sources of variability Cero, Luo, and Falligant (2024) show that lexicon-based sentiment tools often fail to capture domain-specific meanings, subtle affect, and context-dependent emotional cues. Because these dictionaries treat each word the same in every context, they miss subtle meanings and often mislabel weak or ambiguous emotions.

Another challenge comes from the fact that human labeling is often subjective. Because emotional expression and perception are highly subjective, annotations from different raters often diverge — especially for implicit, context-dependent, or low-intensity emotions (Tavernor, El-Tawil, & Mower-Provost, 2024). Additionally, sentiment lexicons such as LIWC and VADER are optimized for English and may fail to capture culturally embedded meanings or community-specific language practices, which are widespread in diverse creator communities (Blodgett et al., 2020).

These limitations reveal key gaps in existing research. Prior work has not systematically examined whether sentiment cues help explain why LLM predictions diverge from human assigned hashtags, nor has it tested whether affective language contributes to mismatches in creator-generated metadata such as hashtags. Despite the sentiment analysis almost used to understand online text, their potential interact with disagreement between LLM model and human are not clearly, leaving a critical dimension of automated content labeling unexplored.

By directly evaluating whether LIWC and VADER scores predict mismatches between human and LLM-generated hashtags, the present study addresses this gap. It provides empirical evidence that if sentiment-based features can account for model–human discrepancies, thereby clarifying the limits of affective lexicons in automated content classification. This contribution highlights the need for future work to move beyond sentiment tools and incorporate richer linguistic indicators—such as semantic similarity, topical structure, and embedding-based representations—that more accurately capture the cues driving both human hashtag choices and LLM interpretations.

Methods

Research Question

Based on prior research, that emotional nuance and language context can make automated text classification complicated. This study further examines whether sentiment-based linguistic features help to explain discrepancies between human-assigned and LLM-predicted hashtags. The research question is:

Do LIWC and VADER sentiment cues help explain mismatches between LLM-predicted and human-assigned hashtags?

Hypothesis Testing

This research question focuses on whether emotional tone, affective intensity, or motivational language in video descriptions influence the alignment between human hashtag choices and model predictions. If sentiment-related cues shape how humans label content but are interpreted differently by the model, posts with stronger or more complex emotional signals may be more prone to mismatch. The study therefore tests the following null hypothesis:

H₀: Posts with stronger LIWC or VADER sentiment scores will show greater differences between human and LLM hashtags.

To examine this relationship, I will use binary mismatch as dependent variable to build a logistic regression model, LIWC and VADER sentiment features as the independent variables, and text length included as a control. Positive and statistically significant coefficients for LIWC or VADER features would indicate that stronger emotional cues increase the likelihood of mismatch. According coefficient and significant of independent variables, model can suggest whether affective language contribute to prediction errors.

This hypothesis assumes that emotionally rich or motivational language introduces ambiguity or contextual nuance that makes it more challenging for the LLM to infer the hashtag category intended by human creators. By evaluating these associations, this analysis provides insight into whether affective features could eventually serve as useful signals for improving future LLM systems. Particularly those sentiment features can be used in content moderation workflows or automated detection of harmful, misleading, or risk-relevant material.

Data

This study uses “Train set” from the Public Health Advocacy Dataset (PHAD), a publicly available collection of social media videos related to tobacco products (Blodgett. The dataset includes videos extract from TikTok and YouTube using tobacco-related search hashtags such as #tobacco, #vaping, #ecigarette, #nicotinepouches, #smoking, and #swisher. The PHAD “Train Set contains ten JSON files: three from TikTok (scraped using #tobacco, #ecigarette, and #nicotinepouches) and seven from YouTube (scraped using a broader set of tobacco-related hashtags). Each record provides text descriptions, platform metadata, engagement features, and human-assigned hashtags.

My research focuses on YouTube videos and four hashtags, which are central to the classification task. Because of my VM capacity limits, the number of hashtag categories was reduced. In this analysis, I selected only four JSON files from YouTube (#cigarette, #vaping, #tobacco, #swisher). After combining and cleaning datasets, the metadata includes 1586 records. There are multiple steps applied to metadata before model steps. The dataset was further filtered to include clean text with (1) a non-empty text description, (2) keep multiple human-assigned hashtag, (3) clean text data by remove irregular format. The final dataset contains three main columns: text (video description), hashtag (human-assigned hashtags), and label (a numeric code for the hashtag category, 1–4). The text column is used both for generating LLM-predicted hashtags and for calculating LIWC and VADER sentiment scores.

Outcome Variable: Prediction Status (Match/Mismatch)

The prediction status variable is constructed by comparing the human-assigned hashtag category with the label predicted by an LLM-based text classifier. The test procedure consists of two main steps. The first step begins by generating LLM predictions. Each video description is classified using a supervised text-classification model implemented through the Unsloth pipeline (adapted from the “Text classification with Unsloth” script). The model is trained to assign one of four hashtag classes—cigarette, vaping, tobacco, or swisher—based solely on the textual description. Creator-assigned hashtags are first mapped to numeric labels (1–4) and serve as the ground-truth class for each record. After training, the LLM produces a predicted label for each description, related to the hashtag category it determines to be the best match.

The second step involves directly comparing labels produced by the LLM with those assigned by human content creators. It can determine whether the LLM successfully reproduced the creator’s intended hashtag category. After the comparison, I can create a binary outcome, where 0 indicates a match between the predicted and human labels and 1 indicates a mismatch. This approach transforms the original four-class classification task into a binary indicator of agreement versus disagreement (prediction status binary). This binary variable serves as the dependent variable (Match/Mismatch) in the logistic regression models and subsequent evaluation analyses.

Predictor Variables: LIWC Features

Prior research shows that LIWC affective ambiguity and subtle emotional cues can contribute to mismatches between human and model judgments. Building on this work, the present study examines whether sentiment cues help explain hashtag mismatch in tobacco-related YouTube descriptions. Earlier studies suggest that emotional or motivational signals can form how viewers interpret content, which may lead to discrepancies between human-assigned and LLM-generated hashtags. Accordingly, this analysis tests whether LIWC and VADER sentiment features—including a custom LIWC harm lexicon—predict differences between human and model hashtag choices.

Sentiment-related predictors were extracted from each video description. LIWC features include affective tone, positive emotion, and negative emotion. Besides that, I added a supplemental harmful-language lexicon to capture linguistic cues that may produce the appeal of tobacco products. Prior research suggests that emotional and motivational language can affect audience psychology, reduce perceived risk, or increase curiosity.

Because harmful or motivational language may influence how creators label tobacco-related content, this study defines such language using a tailored conceptual framework. I operationalize “harmful” linguistic cues as words or phrases that signal desire, reward, or curiosity, grouping them into thematic categories such as States (e.g., need, want, acquire) and Motives (e.g., reward, allure, curiosity). Terms like “have to,” “want,” “get,” “win,” “like,” and “look for” were included, and the frequency of words within each category was summed to create a composite LIWC harm score. This structure allows the analysis to quantify how motivational or curiosity-oriented language may contribute to increased interest in tobacco-related content.

Predictor Variables: VADER Features

VADER sentiment features included the compound polarity score as well as the proportions of positive, negative, and neutral sentiment expressed in each text description. Together, these indicators capture the emotional tone of the content and function as key predictors for evaluating whether affective signals contribute to mismatches between model-generated and human-assigned hashtags.

Exploratory Data Analysis

To understand whether sentiment-based features help explain mismatches between human and LLM-predicted hashtags, I will start with descriptive visualizations. They were generated and embedded in following analysis. These plots illustrate how LIWC and VADER sentiment cues behave across the four hashtag and whether they differ between matched and mismatched cases.

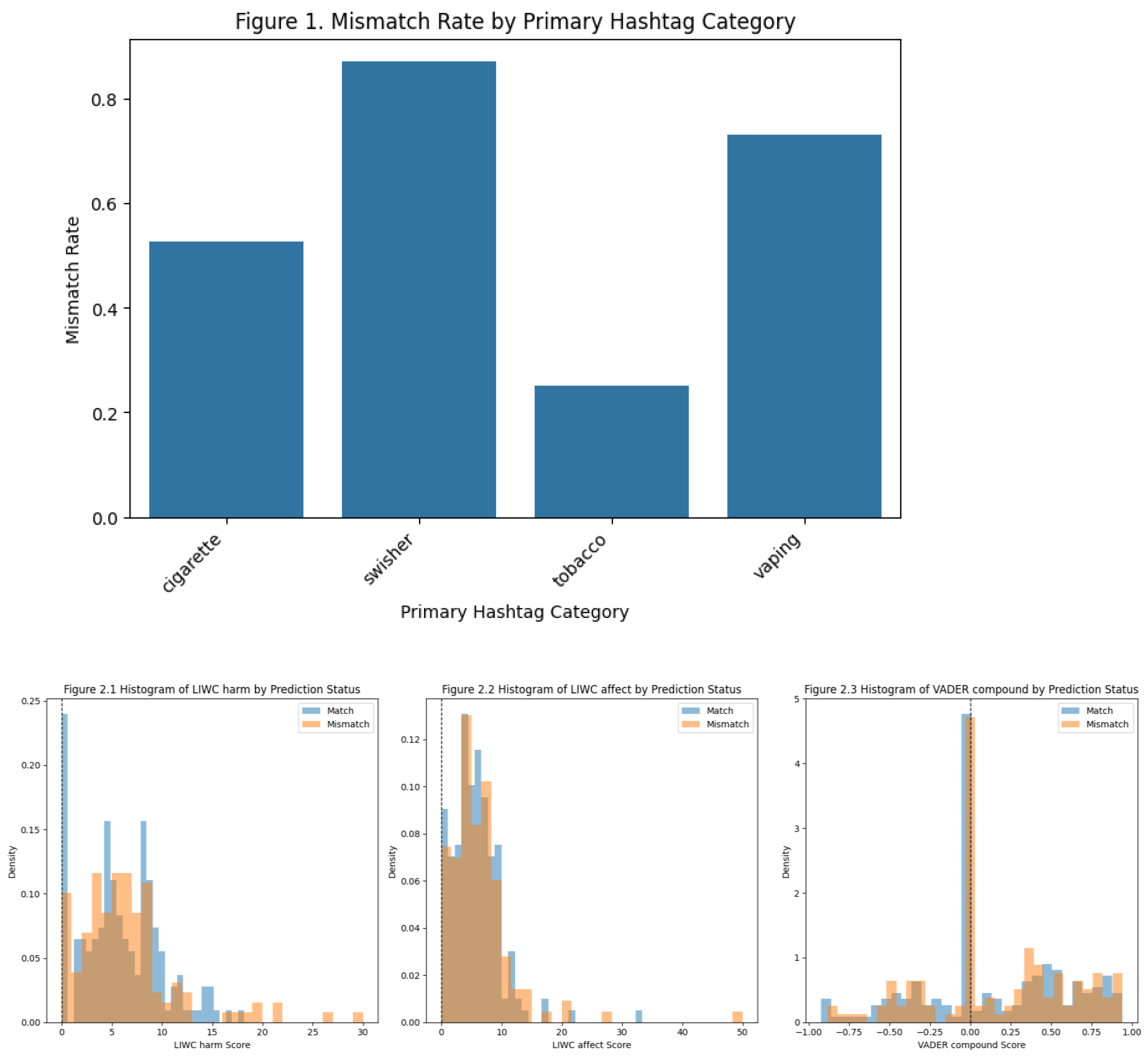

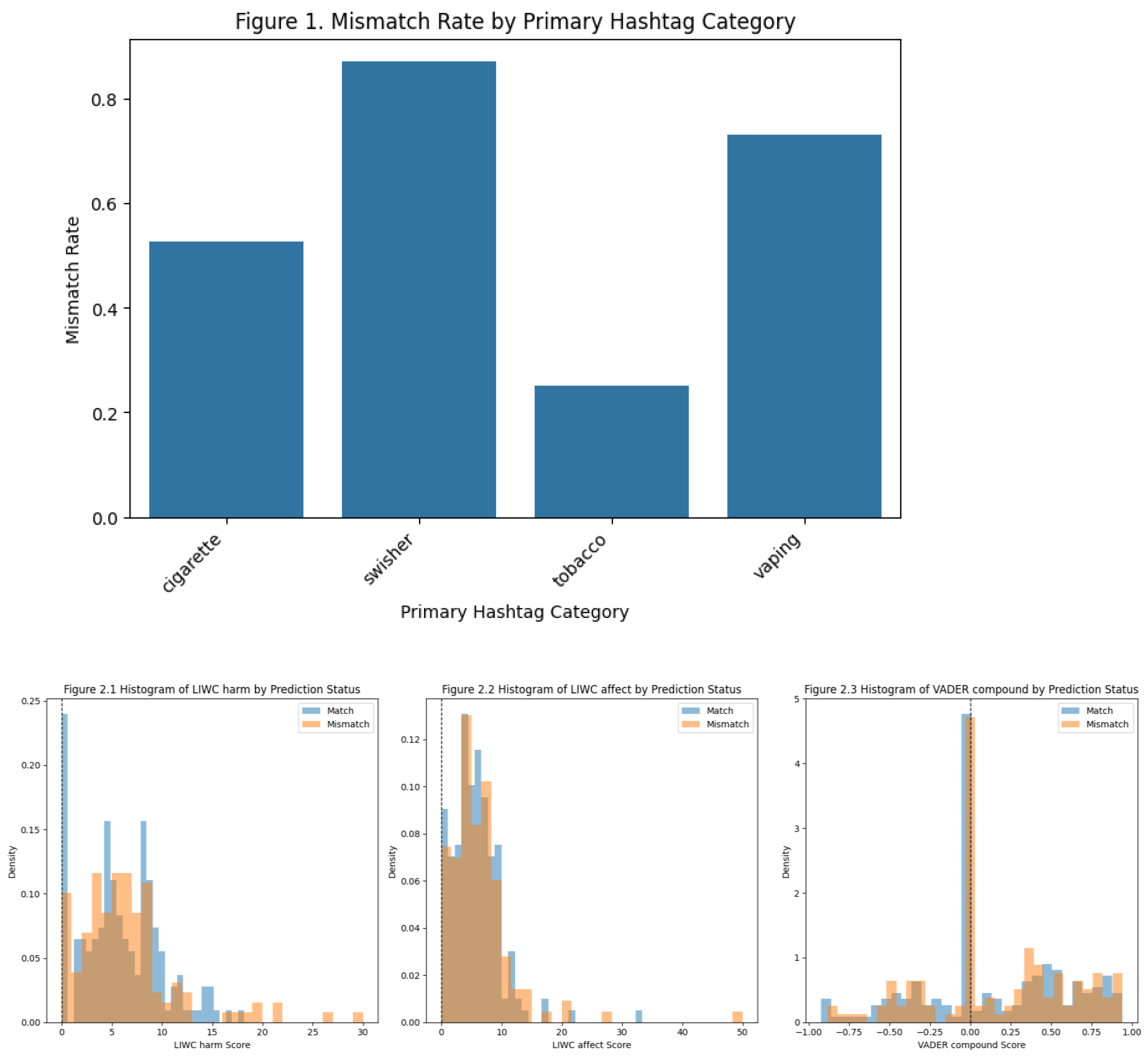

The bar chart highlights substantial variation in mismatch rates across the four primary hashtag categories. This variation indicates that the LLM does not perform uniformly across different types of tobacco-related content. Instead, some categories consistently align more closely with human-assigned hashtags, while others produce far higher disagreement. This pattern suggests that category-specific semantic characteristics meaningfully influence model accuracy.

The tobacco category shows the highest mismatch rate (over 70%), because it is a broad label that covers many contexts, making it harder for the model to infer the hashtag. In contrast, swisher has the lowest mismatch rate, reflecting its specificity as a brand-related term with clearer and more consistent lexical cues. The cigarette and vaping categories fall in the middle, with moderate mismatch levels that reflect their semi-specific but still contextually diverse usage. Figure 1. shows that mismatch rates depend heavily on the semantic specificity of the hashtag category: broad or ambiguous labels lead to greater disagreement, while more distinctive categories yield better model–human alignment.

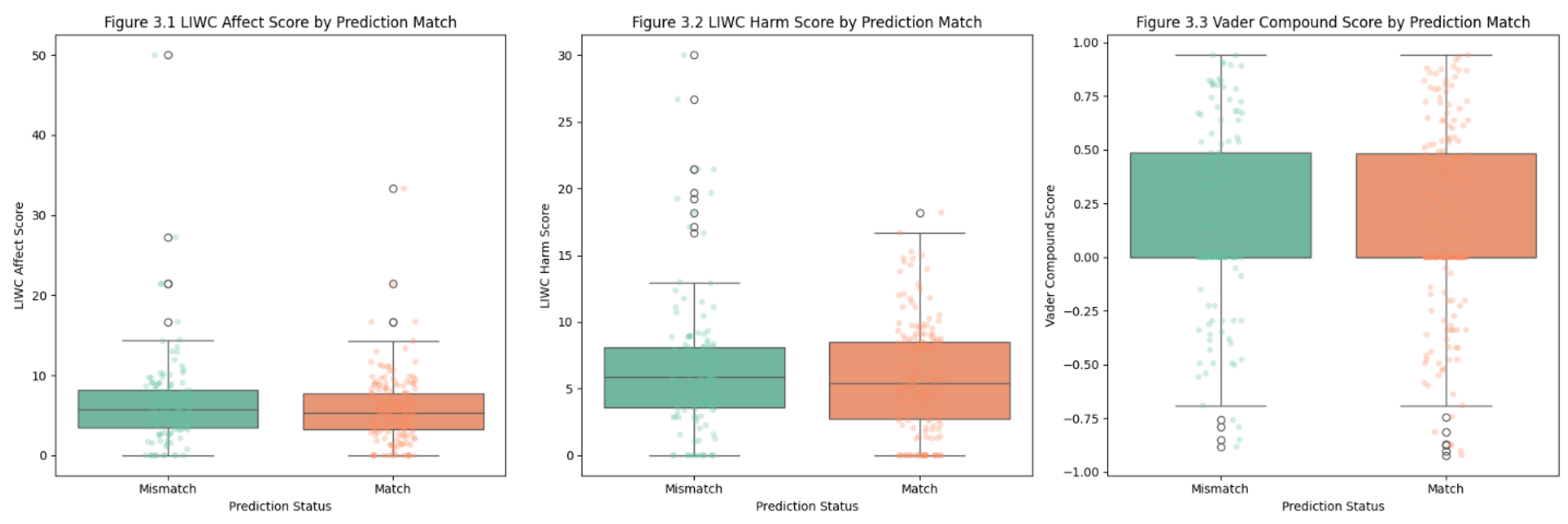

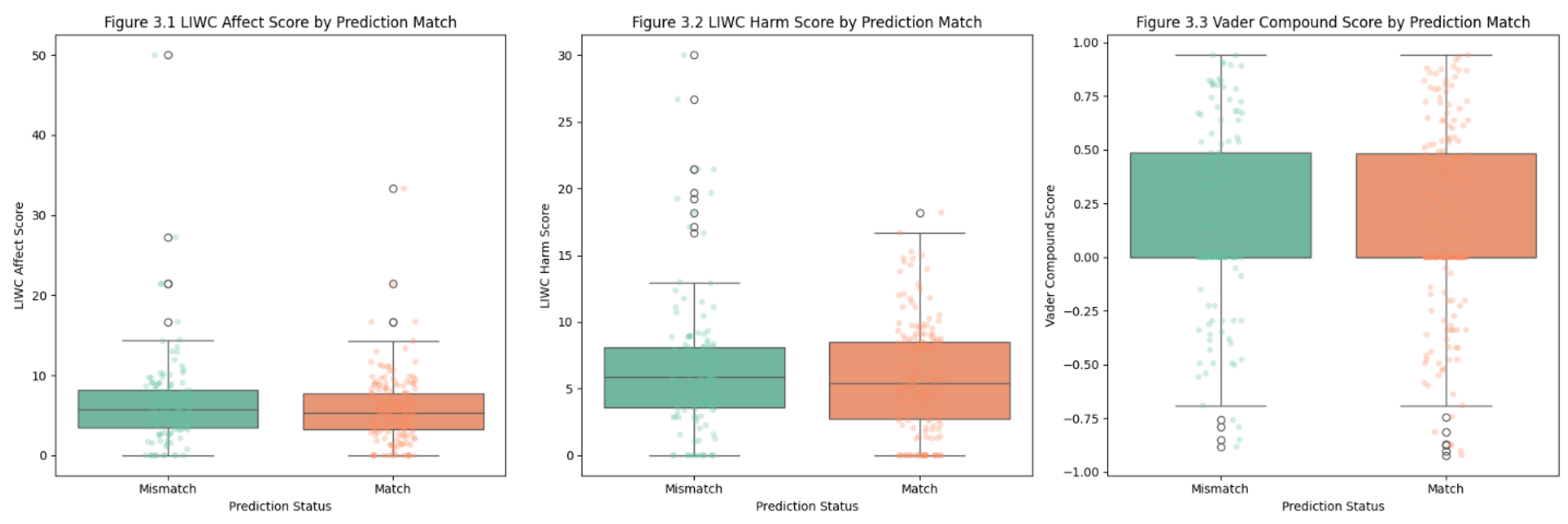

The histograms of LIWC harm, LIWC affect and VADER compound score by prediction status can show high level vision of sentiment cues. Because LIWC harm is a created lexicon structure. LIWC affect stands for affective tone score, which is the sum of positive emotion and negative emotion sum. VADER compound score as well as the sum of positive, negative, and neutral sentiment score.

LIWC harm scores show that the Match and Mismatch groups share highly similar distributional patterns. Both groups cluster in the lower to mid-range of harm-related language, with densities peaking between approximately 3 and 10. Although mismatched cases show slightly more density around the mid-range, this difference is small and inconsistent, and both groups contain occasional outliers with very high harm scores. The substantial overlap across the distributions suggests that the presence of motivational or attraction-related language does not meaningfully distinguish matched from mismatched predictions.

A similar pattern that appears in the LIWC affects histogram. The Match and Mismatch groups exhibit almost identical shapes, with most observations falling within the 5 to 12 range of emotional language. Both distributions peak at comparable values and share similar spreads, indicating that emotional intensity or tone does not reliably influence whether the model correctly predicts the human-assigned hashtag. There is no visual evidence that higher levels of affective language increase classification difficulty for the LLM.

The histogram of VADER compound sentiment strength these conclusions. The histogram of VADER compound sentiment strength these conclusions. Scores of both groups concentrate around zero. That means many descriptions convey neutral sentiment. The distribution of Match and Mismatch keep overlapping across negative, neutral, and positive regions. No evidence appears to associate with increasing mismatch rate. This shows that the sentiment score of the text (whether positive or negative) does not affect the model’s performance.

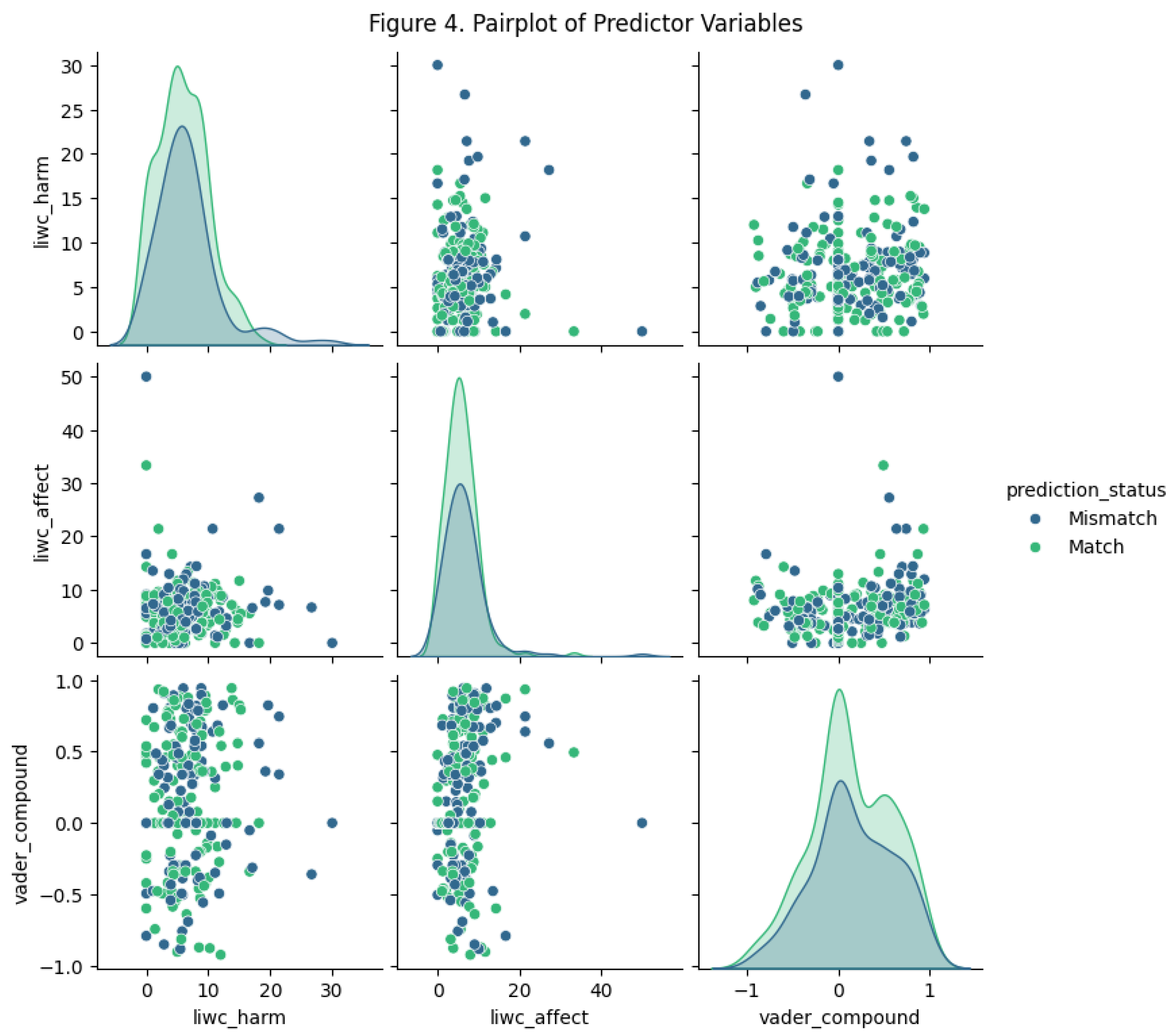

The LIWC affect boxplot exhibits that the Match and Mismatch groups share highly similar distributions. Both categories exhibit nearly identical medians and interquartile ranges, and their spread of affective scores is almost the same. Although a few extreme outliers appear in both groups, these cases are limited and scattered. The strong overlap between the two distributions indicates that the emotional tone captured by LIWC affect does not meaningfully influence the model’s predicted.

A similar conclusion emerges from the LIWC harm boxplot. The Match and Mismatch groups again display comparable medians and variability, with most observations clustering in the lower harm-score range. While both groups contain several posts with higher harm scores, these outliers do not appear disproportionately in either category. This pattern suggests that the presence of motivational, attraction-related, or curiosity-oriented language is not systematically associated with LLM prediction errors. The model performs similarly across descriptions with low and high harm content. For mismatch group, more outliers show in plot. One potential reason is that text length affects the score. Some short descriptions have harm lexicon structures.

The VADER compound sentiment boxplot reveals a slight but still limited difference. Matched predictions show a modestly higher median compound score, suggesting that posts with somewhat more positive sentiment may be slightly easier for the model to classify correctly. However, the distributions still overlap substantially, and both groups include posts across the full range of positive and negative sentiment. Negative outliers appear in both categories, further illustrating that polarity alone does not drive mismatch outcomes.

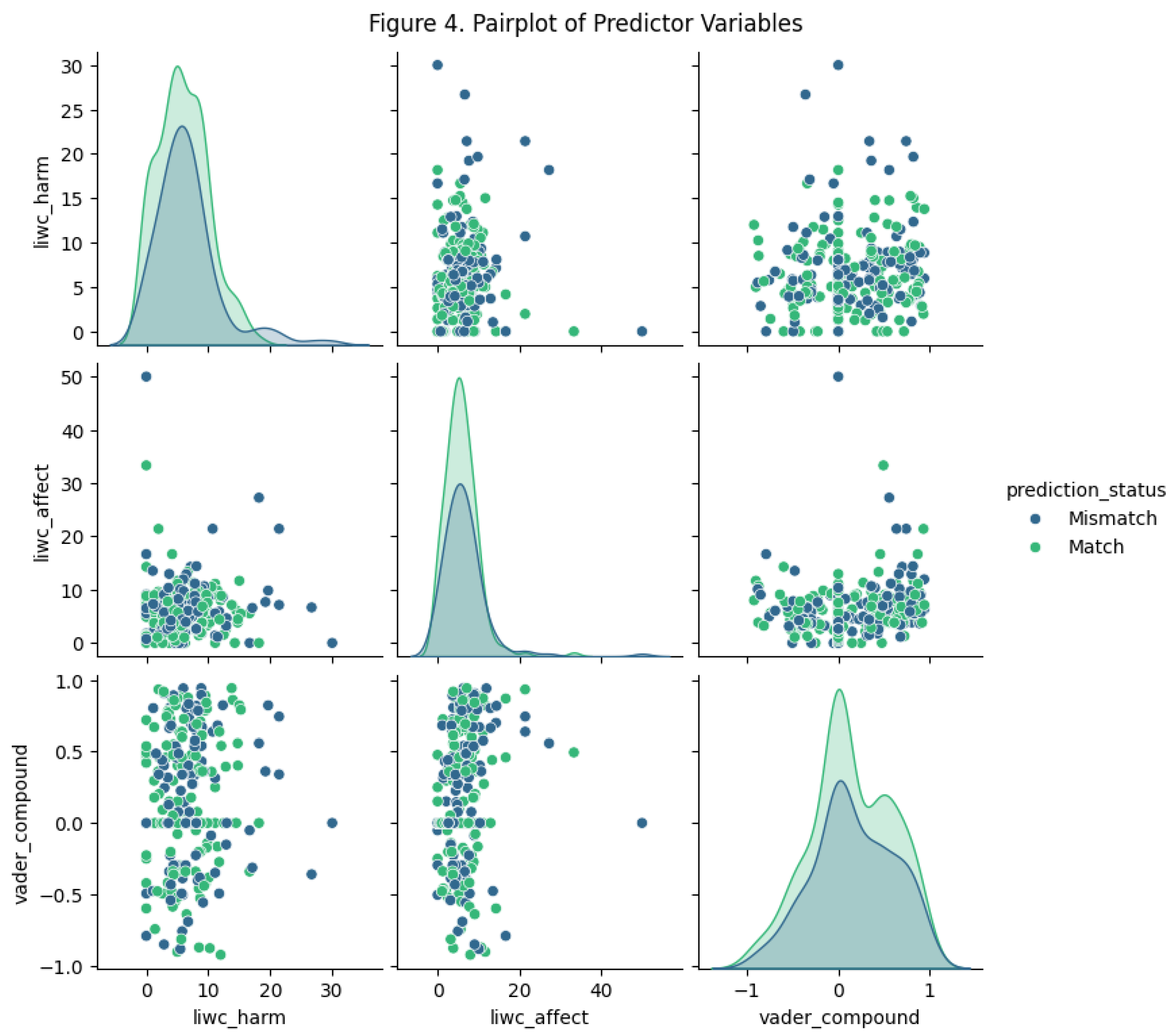

Relationship Between Predictor Variables

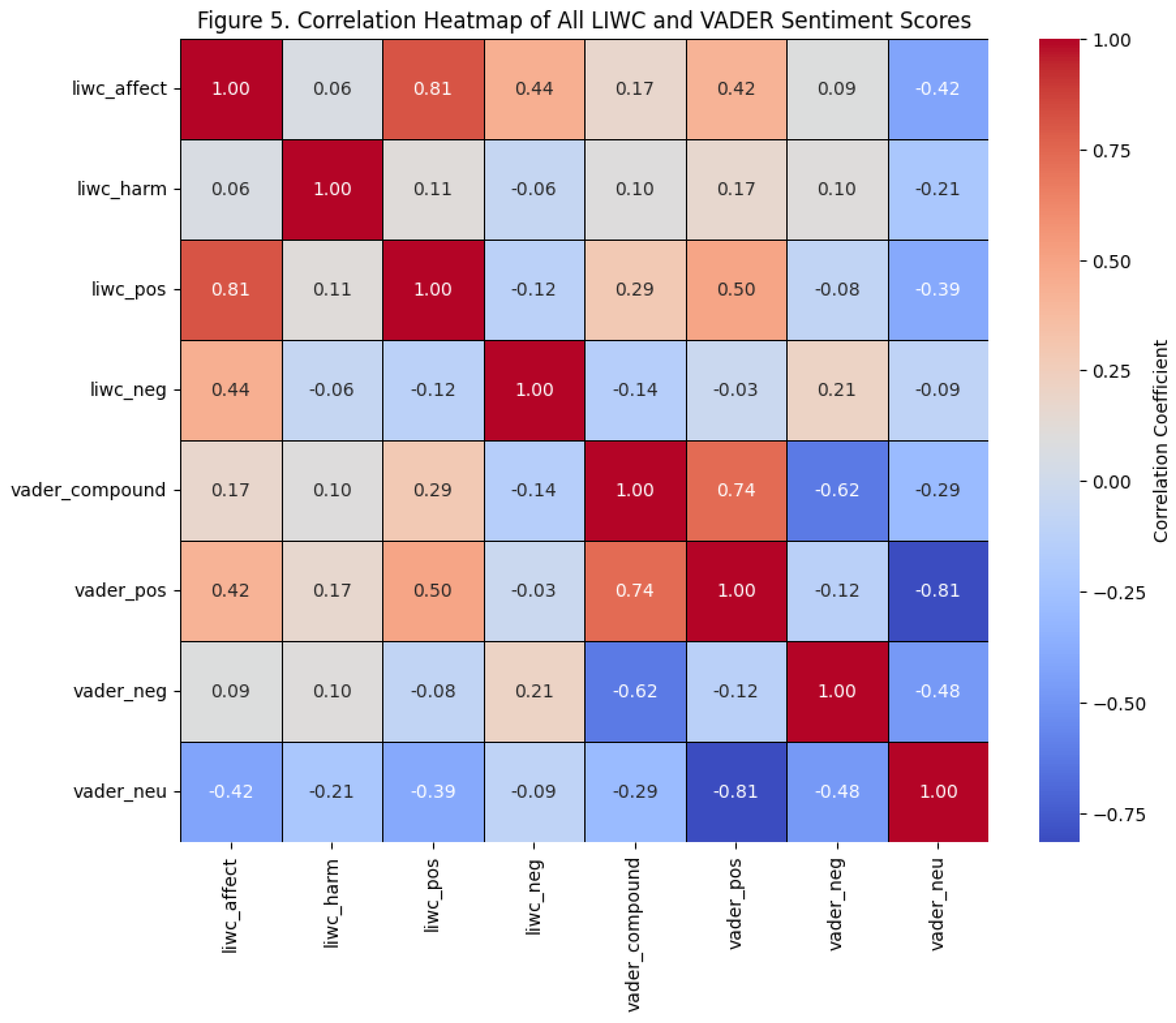

Across the entire pairplot, the blue (Mismatch) and green (Match) points are heavily mixed together. None of the scatterplots show clustering or separation by prediction status. This indicates that LIWC harm, LIWC affect, and VADER compound scores do not meaningfully in differentiate between two groups. LIWC harm scores, LIWC affect scores and the VADER compound scores do not separate the two groups. implying that sentiment-based cues are not driving classification errors. The scatterplots have no clear upward or downward trends. LIWC harm does not correlate strongly with LIWC affect, and neither feature shows noticeable association with VADER compound sentiment. This indicates that the predictors capture independent aspects of the text. All of them are vary independently rather than forming a single coherent emotional dimension. This independence helps explain why combining these sentiment measures does not improve mismatch prediction.

The diagonal density plots reveal that the Match and Mismatch groups share nearly identical distributions for all three sentiment variables. For LIWC harm and LIWC affect, the peaks and spreads are almost indistinguishable. For VADER compound, matched posts appear slightly more positive on average, but the distributions still overlap extensively. This strong similarity across distributions reflects that emotional, motivational, or polarity-based language is expressed at comparable levels regardless of whether the model assigns the correct hashtag.

The scatterplots include posts with unusually high harm or affect scores, as well as highly negative VADER sentiment scores. These outliers are present in both Match and Mismatch categories. The absence of concentration of mismatches at these extreme values suggests that the model is not disproportionately challenged by highly emotional or strongly polarized descriptions. Instead, mismatches occur throughout the sentiment range, the evidence shows that sentiment intensity alone does not predict classification errors.

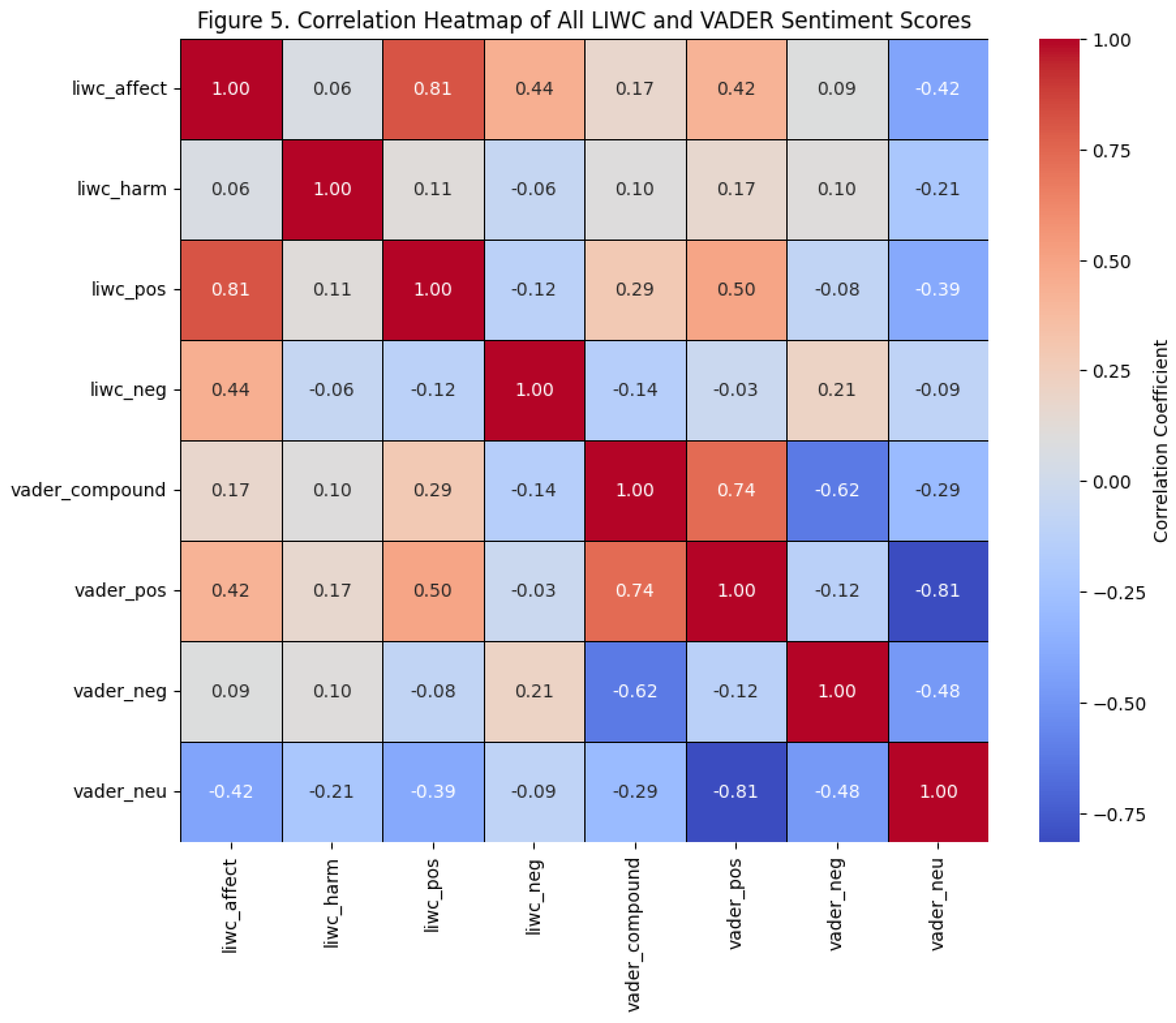

Before fitting the logistic regression model, I will plot the heatmap to check multicollinearity among the independent variables. LIWC affect, for example, is derived from the sum of LIWC positive and negative emotion, while VADER compound reflects a weighted combination of positive, neutral, and negative sentiment. Since LIWC harm is a custom lexicon that captures motivational or attraction-related language rather than polarity, I first needed to determine which sentiment variables should be retained or removed to avoid redundancy in the model.

The correlation heatmap reveals several clear patterns. LIWC affect and LIWC positive emotion show a very strong positive correlation, indicating that posts with more general affective language also contain more explicitly positive terms. LIWC affect also correlates moderately with LIWC negative emotion, suggesting that affective expression in this dataset includes both positive and negative cues rather than one dominant direction.

LIWC harm, however, shows only weak correlations with all LIWC and VADER sentiment variables. This indicates that harm-related language represents a distinct linguistic construct rather than a traditional sentiment signal. Posts can use motivational wording without being emotionally polarized, which explains why LIWC harm behaves independently of other sentiment features.

The VADER sentiment measures show the strongest internal consistency. VADER compound correlates strongly with VADER positive and negatively with both neutral and negative sentiment, reflecting how the compound score summarizes polarity. VADER positive and VADER neutral also exhibit a strong negative correlation, indicating that texts high in positivity tend to contain fewer neutral elements.

Correlations between LIWC and VADER are modest. While LIWC affect and LIWC positive correlate moderately with VADER positive sentiment, other cross-system relationships—such as LIWC negative with VADER negative—remain weak. This suggests that LIWC and VADER encode emotional information through different theoretical frameworks and therefore provide complementary rather than overlapping insights.

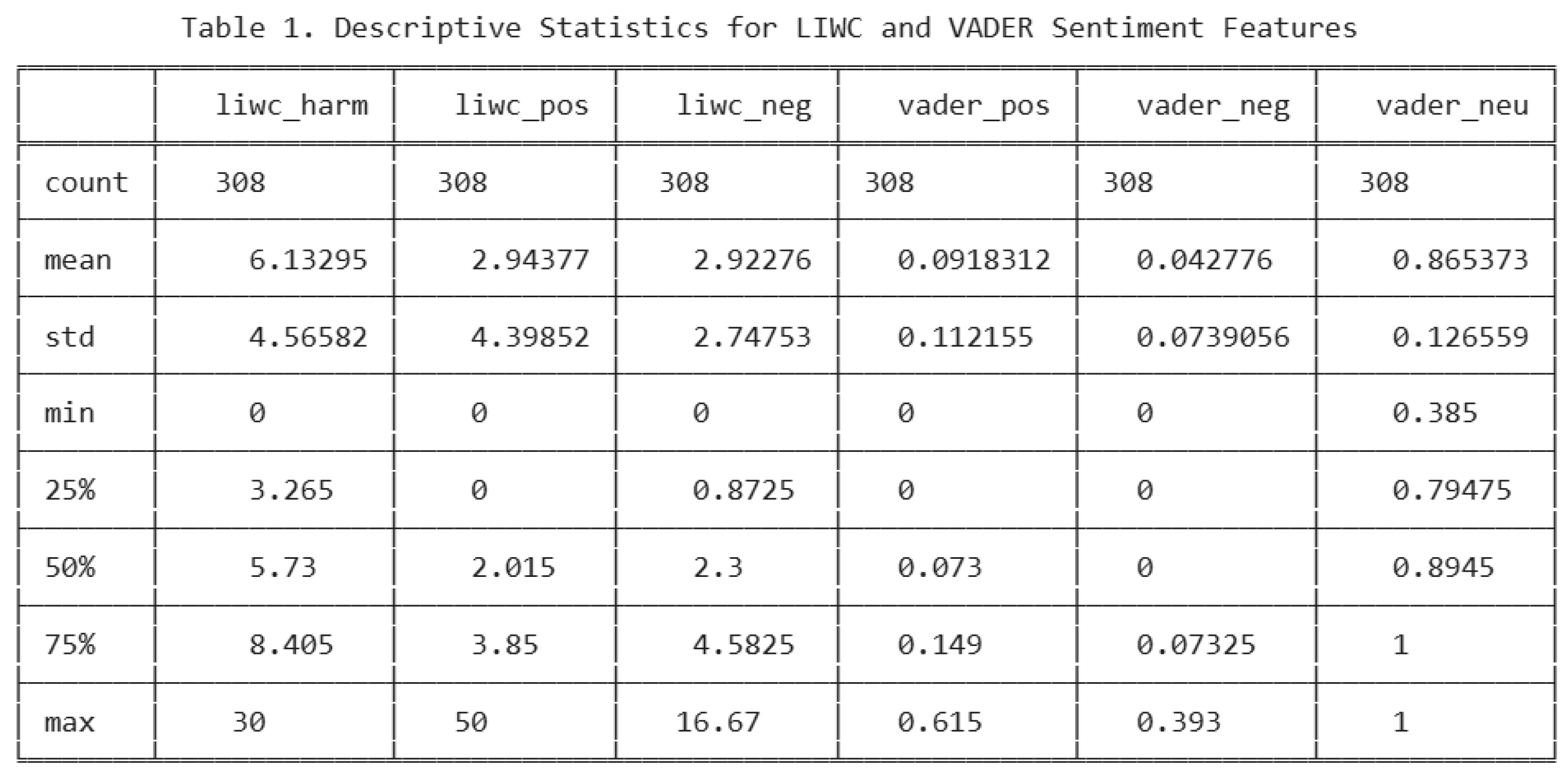

In summary, the heatmap highlights three key patterns: (1) LIWC affect and LIWC positive emotion form a single emotional cluster; (2) VADER sentiment features show strong internal coherence; and (3) LIWC harm functions independently from traditional sentiment cues. Although LIWC affect represents a useful broad emotional measure in prior research, the present study focuses on more specific sentiment dimensions. Therefore, LIWC affect is excluded from the model due to collinearity with LIWC positive and negative emotion. VADER compound also was removed and retain the more detailed components. As a result, the logistic regression model includes the following predictors: liwc_harm, liwc_pos, liwc_neg, vader_pos, vader_neu, and vader_neg. Then, I examined the descriptive statistics for each of these variables.

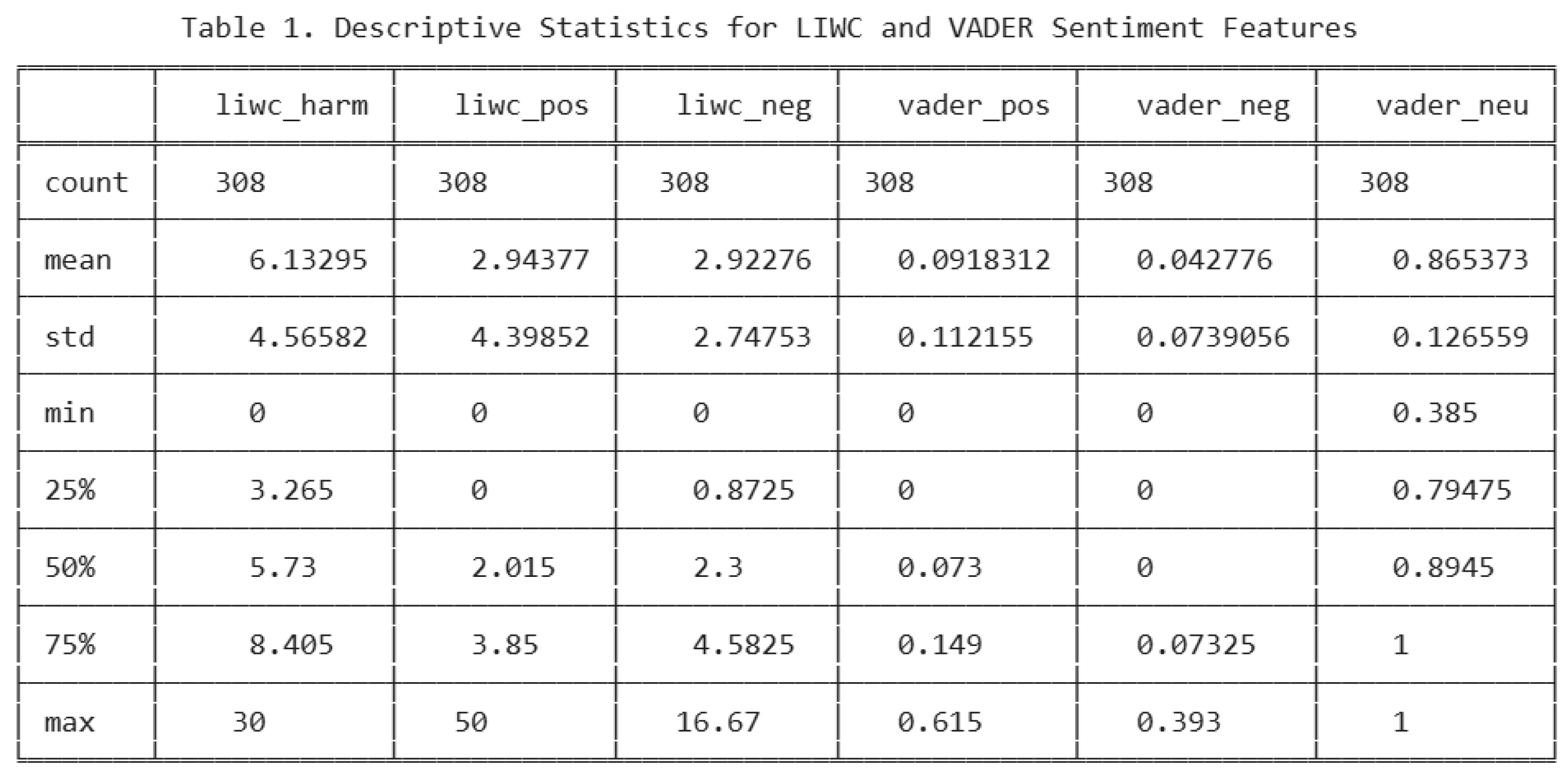

These descriptive statistics show that the dataset contains mostly neutral, low-emotion descriptions with moderate levels of motivational or attraction-related language. LIWC harm demonstrates steady presence but not extreme variation, while LIWC positive and negative emotions contain rare but substantial outliers. VADER sentiment confirms a strong neutral tone across the dataset, with limited examples of high positive or negative polarity. Collectively, these patterns suggest that the emotional and motivational features present in the dataset are not strong or consistently varied enough to meaningfully distinguish matched from mismatched predictions—a conclusion supported by later model results.

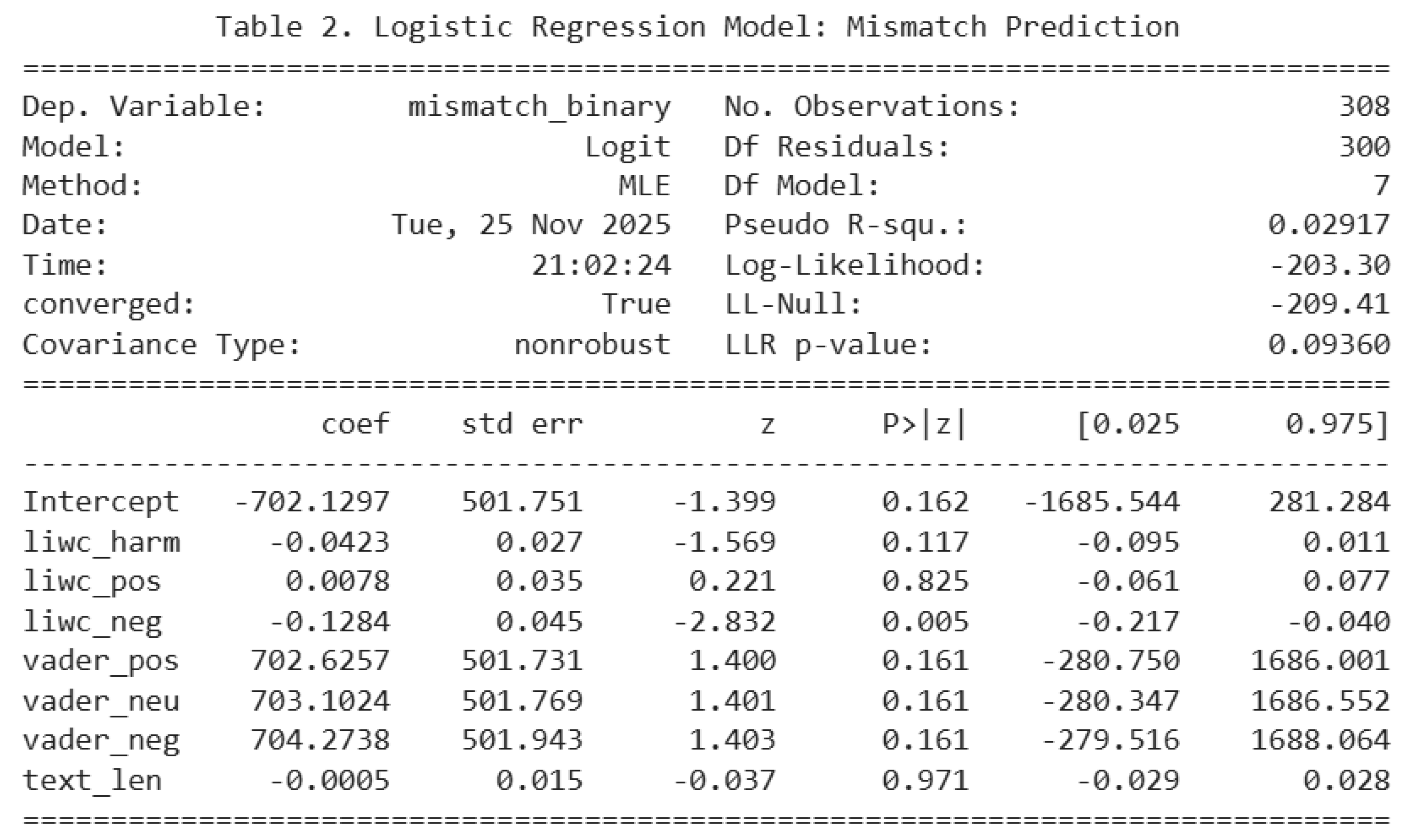

Model and Results

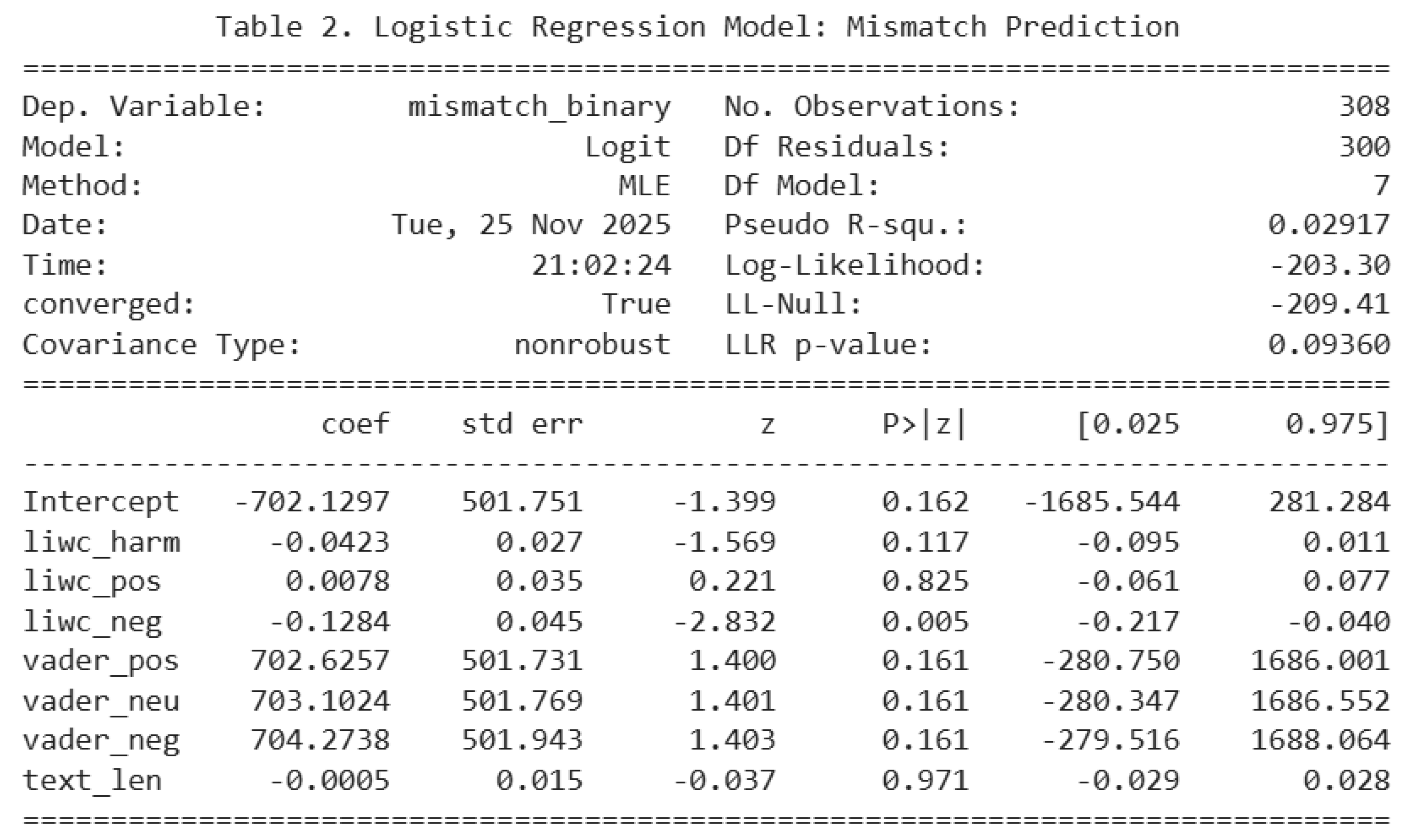

The logistic regression model examines whether LIWC and VADER sentiment features predict whether the LLM’s hashtag classification matches the human label. The results show the model prediction is very limited, with a pseudo-R² of 0.029, indicating that sentiment-based predictors explain only about 3% of the variance in mismatch outcomes. In model’s likelihood ratio test (LLR p = 0.093), p value is not significance, suggesting that the set of predictors does not meaningfully improve prediction in the null model. Several individual coefficients are small in model, nonsignificant, and centered near zero. For example, LIWC harm (β = −0.042, p = 0.117), LIWC positive emotion (β = 0.0078, p = 0.825), and VADER compound-related components (vader_pos, vader_neu, vader_neg all p > 0.14) do not significantly predict mismatch. These results show that neither emotional intensity nor VADER sentiment polarity meaningfully affects whether the LLM model agrees with human hashtags. In other words, sentiment—positive, negative, or motivational—does not make the LLM model prediction more or less likely to be wrong.

From Table 2., the only significant predictor is LIWC negative emotion (β = −0.128, p = 0.005). This coefficient suggests that posts containing slightly more negative emotional language are less likely to produce mismatches. From plot, the effect is extremely small, and the confidence interval is very close to zero. That indicates even though it is statistically detectable, it has little practical importance. This may reflect minor wording patterns in how bacco content is described rather than a meaningful predictive signal.

The large coefficients for VADER neutral, positive, and negative are numerically unstable and reflect scaling rather than meaningful effects. Their large standard errors and wide confidence intervals establish that these predictors do not significantly influence mismatch likelihood. Text length also shows no significant (β ≈ 0, p = 0.971), suggesting that longer descriptions do not improve or reduce model accuracy.

In conclusion, the results of logistic regression provide strong evidence that sentiment features do not meaningfully predict mismatches between human and model hashtags. Emotional tone, polarity, and motivational cues appear to have little role in the LLM’s classification errors. This finding same as earlier descriptive and visualization results, supporting the conclusion that mismatches are driven by factors other than sentiment—such as semantic ambiguity, topic breadth, or contextual complexity.

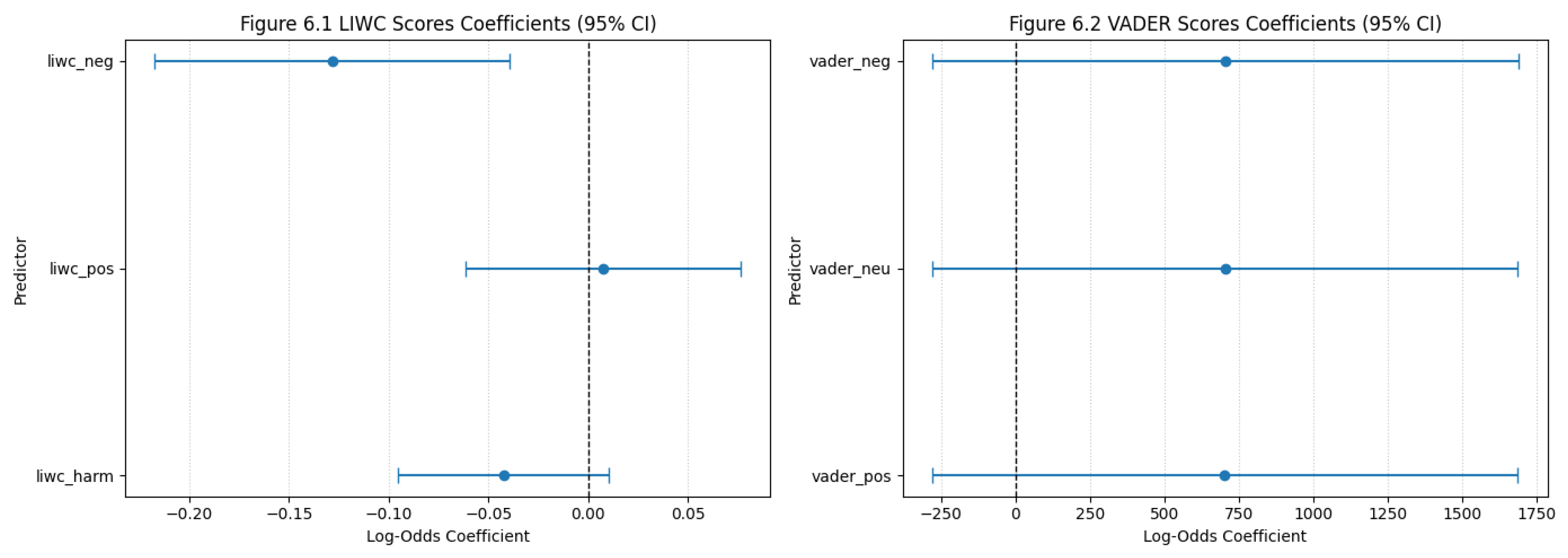

Model Explanation and Diagnostics

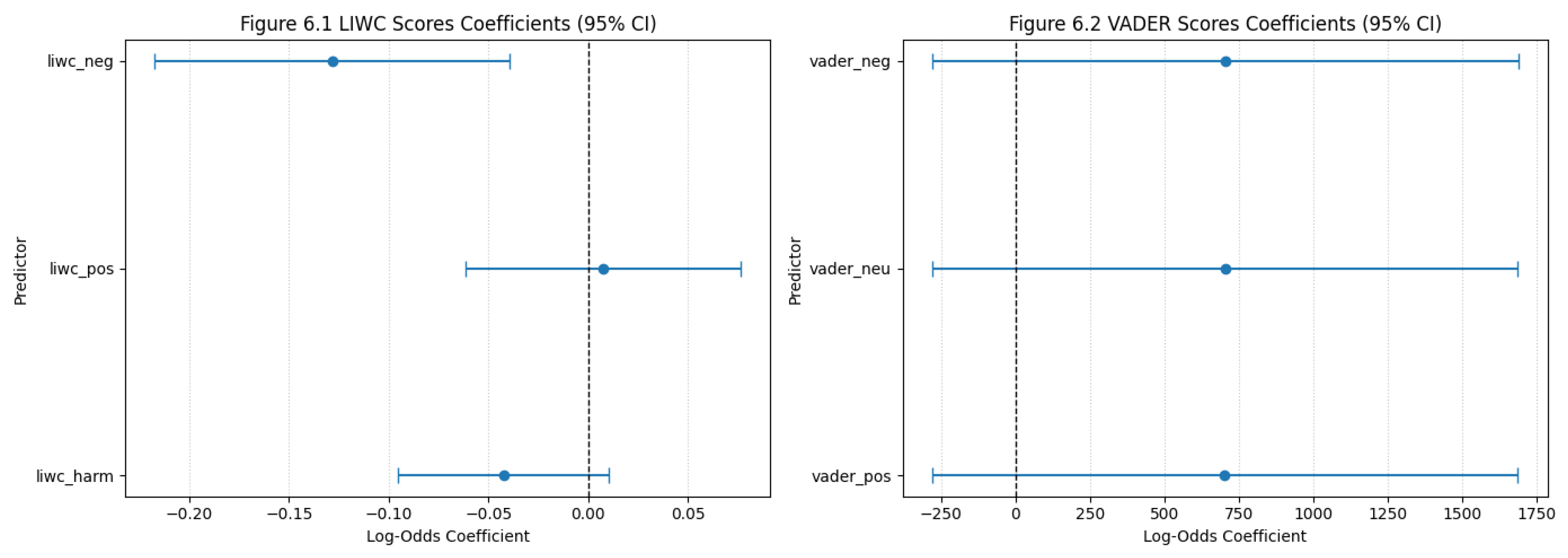

The LIWC coefficient plot shows that all three LIWC predictors—liwc_harm, liwc_pos, and liwc_neg—have very small effects, with coefficients close to zero. For LIWC harm and LIWC positive emotion, the confidence intervals cross zero, meaning they have no meaningful influence on mismatch likelihood. Their confidence interval cross positive and negative values, so they do not consistently increase or decrease mismatches. Although liwc_neg is statistically significant, its effect is extremely small (about −0.13), so posts with slightly more negative wording are only marginally less likely to produce mismatches, and the impact is too small in the model.

The VADER coefficient plot shows very large values for vader_pos, vader_neg, and vader_neu, but these numbers are meaningless because VADER scores’ rage is only between 0 and 1, which makes the estimates unstable. All confidence intervals cross zero, showing that none of the VADER features significantly predict mismatch outcomes. The wide uncertainty means the model cannot determine whether these effects are positive, negative, or nonexistent. This aligns with earlier findings that most descriptions are highly neutral, giving VADER little variation to detect.

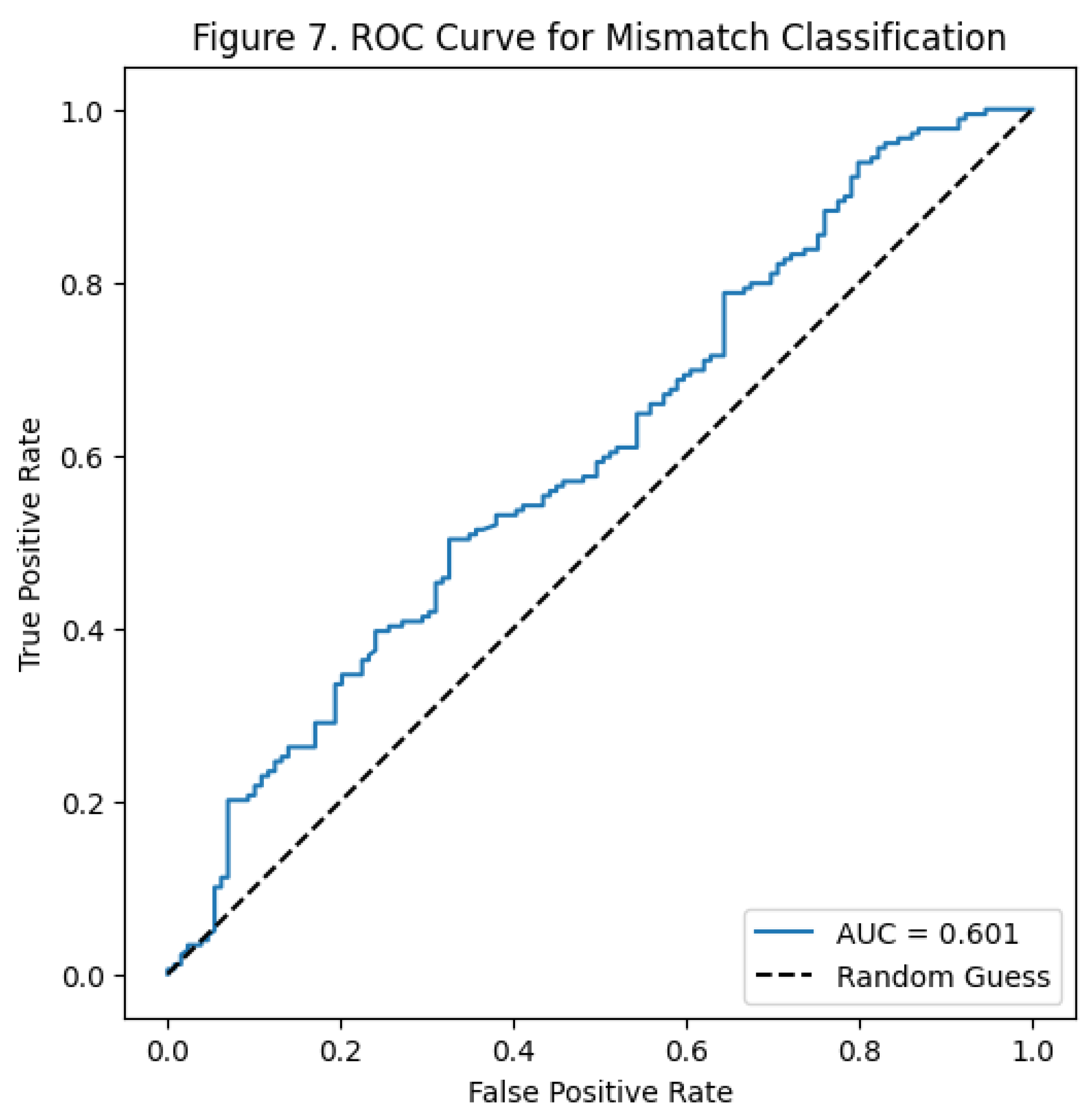

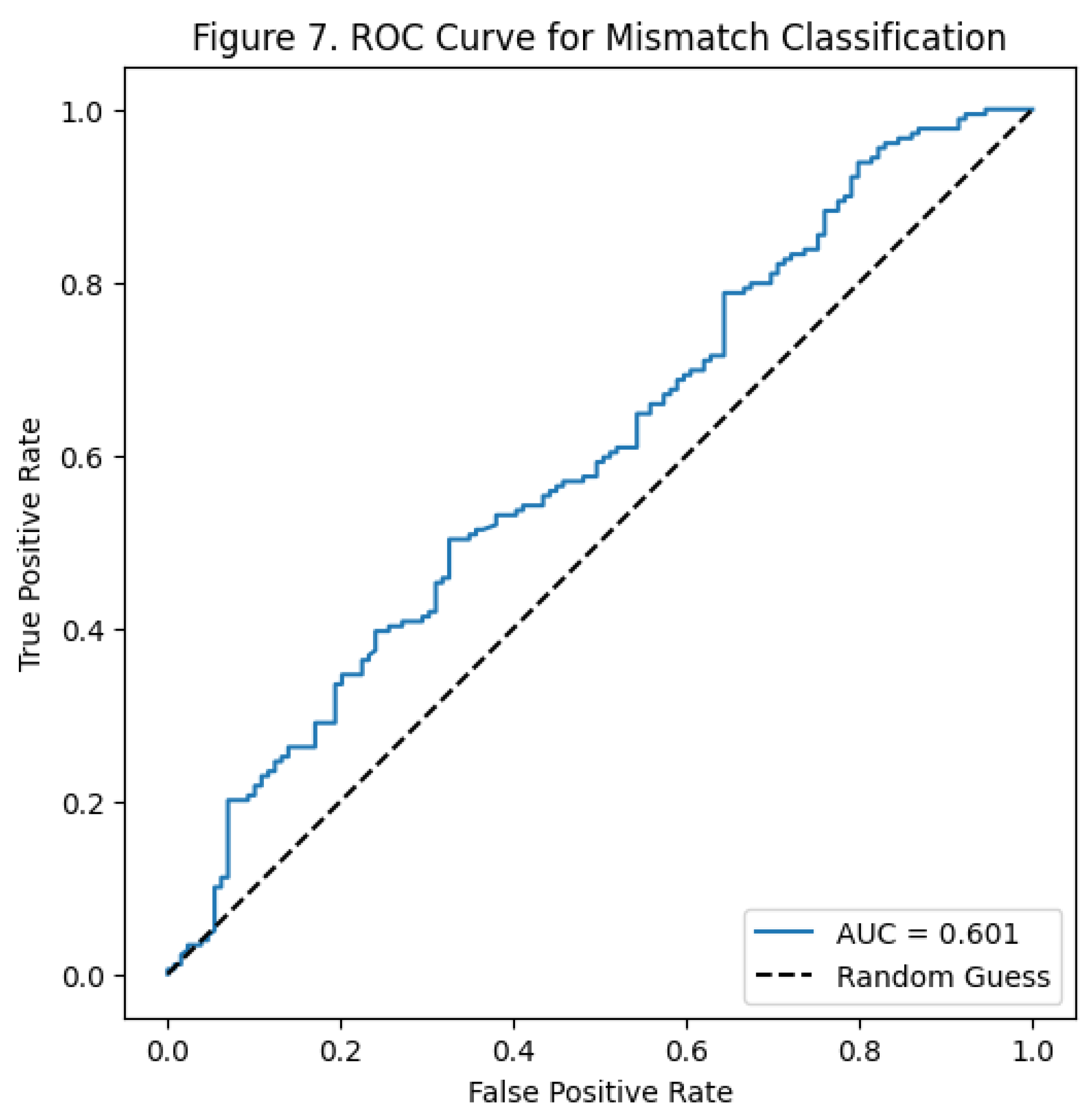

Collectively, both LIWC and VADER coefficient plots show that sentiment-based features, whether emotional tone, harm language, or polarity—do not meaningfully influence whether the LLM predicts the human hashtag correctly. LIWC effects are minimal, and VADER effects are unstable. These results validate the conclusion that mismatches are driven by other factors, such as semantic ambiguity or topic complexity, rather than sentiment cues. After checking the coefficients, I evaluated the model’s predictive ability from ROC plot. The ROC curve sits only a little above the diagonal reference line, which represents

The ROC curve sits only a little above the diagonal reference line, which represents random guessing. A strong model would rise sharply toward the upper-left corner, but this curve is flat and shallow, showing that the model has weak ability to separate matched from mismatched posts. This means the predictors do not provide strong or consistent signals for identifying mismatch cases.

The AUC value of 0.601 shows that the model works a little better than random chance. The AUC value above 0.60 means the model has weak ability to predict. The low score tells us that the sentiment-based features do not help to tell mismatches from matches. The results match the previous findings. The small coefficients, large confidence intervals and similar sentiment patterns mean no explainable between matched and mismatched groups. Even when combined in a logistic model, sentiment features do not improve prediction. Emotional tone, polarity, and harm-related language do not drive mismatch outcomes; instead, factors like semantic ambiguity, contextual complexity, or topic breadth are more likely responsible. Although the ROC curve and AUC summarize how well the model predict mismatch cases, to assess model’s predicted probabilities are accurate, the next step is to examine the calibration plot.

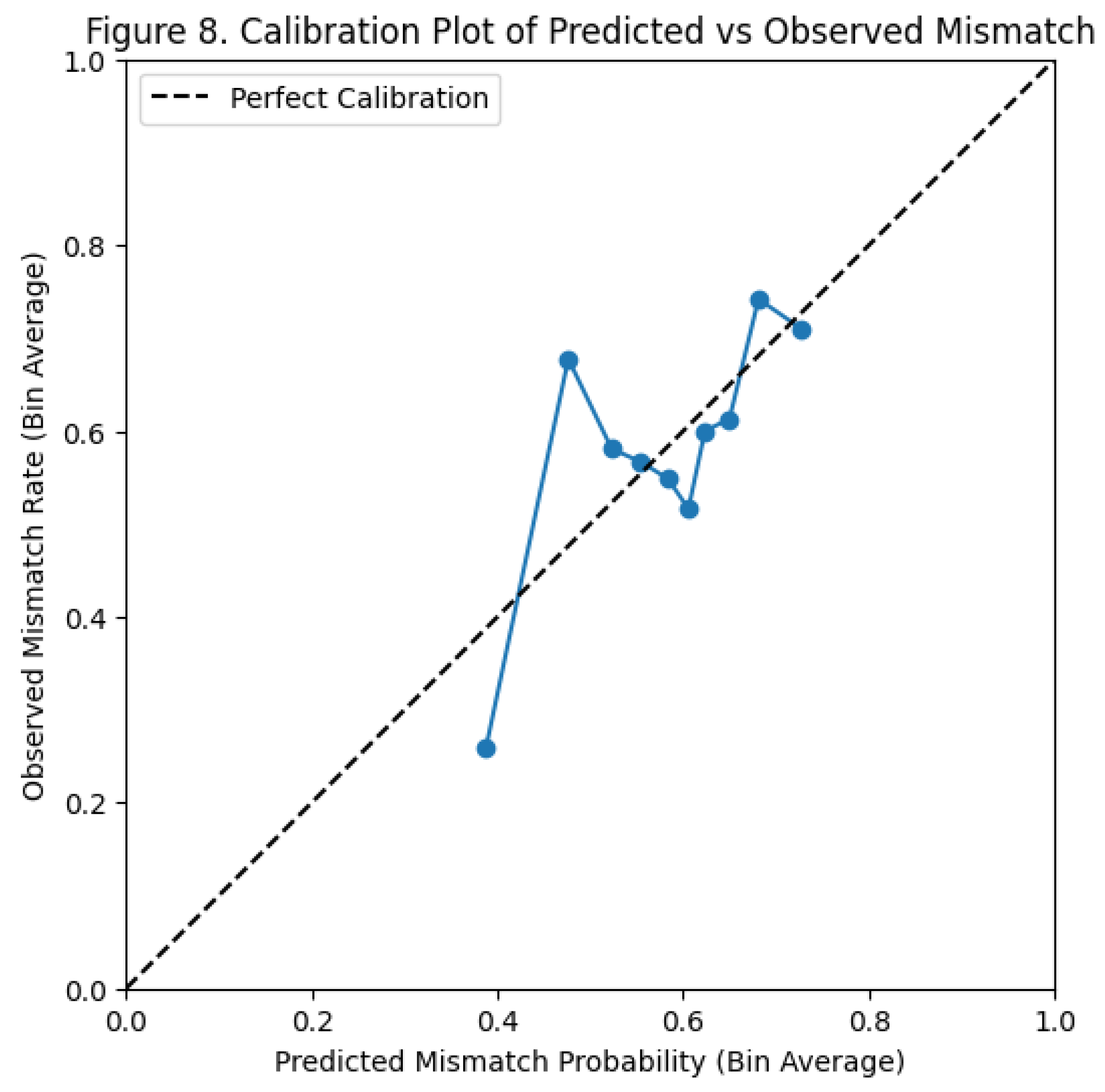

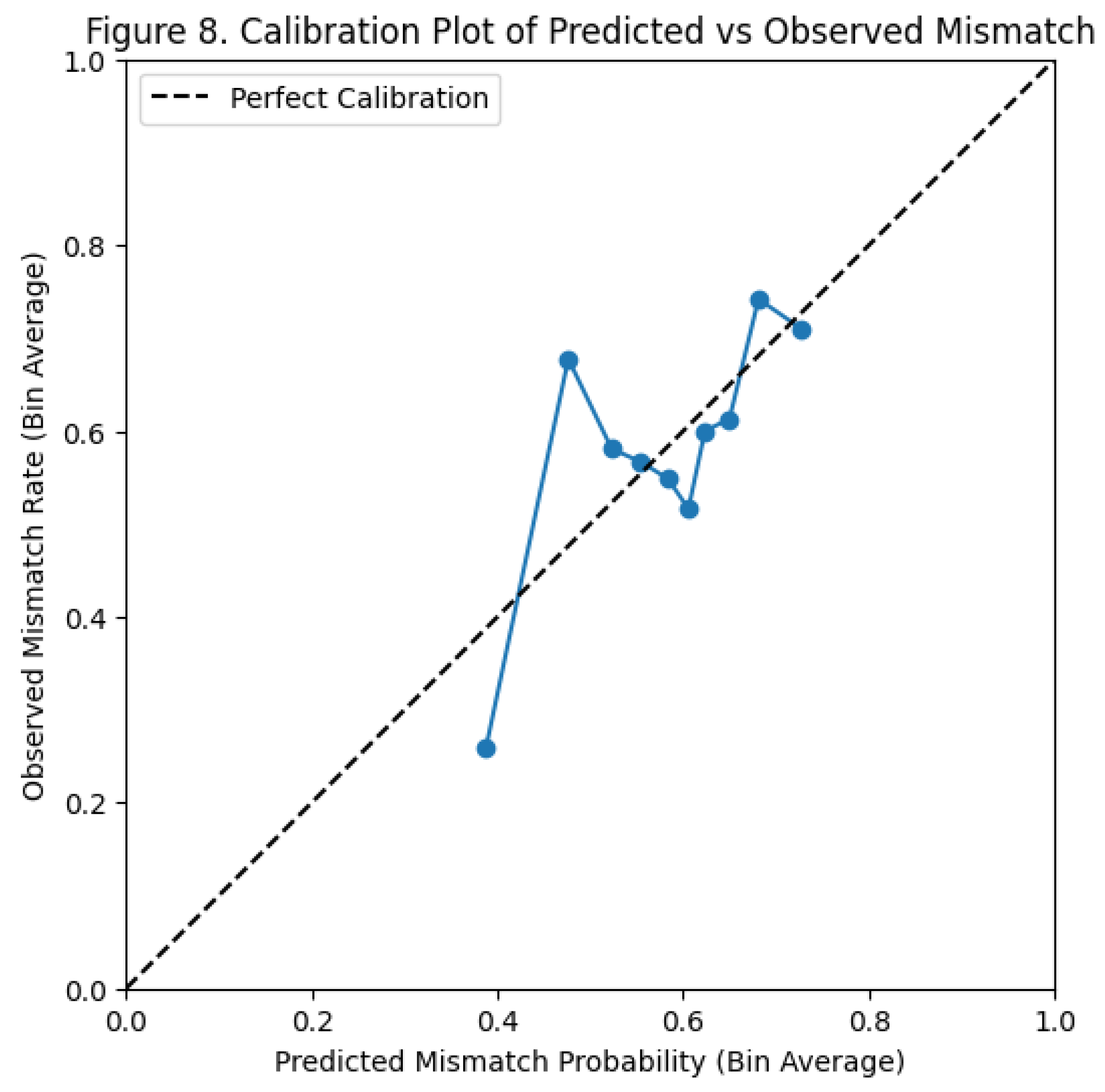

The calibration plot compares the model’s predicted mismatch probabilities with the actual mismatch rates. In a well-calibrated model, the points would line up along the diagonal, meaning predictions match real outcomes. In this plot, the points fall above and below the line, showing that the model does not reliably match predicted probabilities to actual mismatch frequencies.

Across the bins, predicted probabilities range from about 0.40 to 0.75, but the relationship with the true mismatch rate is inconsistent. At lower predicted values (around 0.40), the model underestimates the real mismatch rate, which rises above 0.60 in some bins. In the mid-range (around 0.55–0.60), the observed mismatch rate fluctuates around the predictions, showing instability. At higher predicted values (around 0.70–0.75), the model comes somewhat closer to the diagonal but still deviates, indicating that even high-confidence predictions are not consistently accurate.

The jagged shape of the curve shows that the model is poorly calibrated and produces noisy probability estimates. It does not consistently overpredict or underpredict mismatches—its predictions vary irregularly. This matches earlier ROC and coefficient results, showing that sentiment features do not provide stable signals for predicting mismatches, and the model’s probability estimates should not be viewed as reliable.

Conclusion

This study examined whether sentiment-based linguistic cues—measured using LIWC emotion categories and VADER polarity scores—help explain mismatches between human-assigned and LLM-predicted hashtags for YouTube tobacco-related video descriptions. Across all analyses, the results consistently show that sentiment signals do not meaningfully predict when the model will fail to match the creator’s chosen hashtag.

Exploratory analyses showed that mismatch rates differed across hashtag categories, but these differences were caused by category specificity, not emotional language. Wide-category hashtag such as tobacco showed high disagreement, whereas specific hashtag like swisher aligned much more closely with model predictions. This suggests that semantic ambiguity and category breadth—not sentiment—pose the main challenge for the classifier. Similarly, distributions of LIWC harm, LIWC affect, and VADER scores showed heavy overlap between matched and mismatched posts, indicating that emotional tone, polarity, or motivational cues do not differentiate correctly from Mismatch predictions.

The logistic regression model reinforced these findings. Sentiment-based predictors had minimal and nonsignificant effects, explaining only about 3% of the variance in mismatch outcomes. LIWC negative emotion showed a statistically detectable but very small effect, offering little practical value. VADER predictors were unstable and uninformative, reflecting the neutral tone of most descriptions. Model diagnostics supported this interpretation: the ROC curve indicated weak discrimination (AUC ≈ 0.60), and the calibration plot showed inconsistent probability estimates, confirming that sentiment features cannot reliably separate mismatch from match.

In summary, the results provide strong evidence that emotional, motivational, and polarity-based language does not influence whether the LLM reproduces human hashtag choices. Instead, mismatches appear to arise from broader semantic factors—such as category ambiguity, contextual complexity, or topic diversity—rather than sentiment signals. Future work should explore richer linguistic features, such as semantic similarity measures, topic structure, or embedding-based representations, which may better capture the cues that shape human hashtag choices and LLM interpretations. Incorporating these features may improve automated hashtag prediction and enhance applications in content moderation, health communication, and risk-related media surveillance.

General Discussion

The pattern across analyses is clear: sentiment cues do not meaningfully predict mismatch outcomes between human and LLM-generated hashtags. Although mismatch rates varied across categories, this variation reflected differences in semantic specificity rather than emotional tone. Broad categories like tobacco produced high disagreement, while more precise labels such as swisher showed much better alignment. This indicates that classification challenges arise from category ambiguity, not from sentiment in the text.

Sentiment visualizations supported this conclusion. Matched and mismatched posts showed nearly identical distributions across LIWC affect, LIWC harm, and VADER polarity scores. The logistic regression model confirmed this pattern, with sentiment predictors explaining very little variance and offering no reliable predictive power. Additional diagnostics, including ROC and calibration curves, showed weak discrimination and inconsistent probability estimates, further demonstrating that sentiment is not a useful signal for detecting mismatches.

Overall, these findings show that emotional or motivational language does not affect the models ability to reproduce human hashtag choices. Instead, mismatches are caused by ambiguity, topic complexity or contextual nuance. Future work should add into semantic features, like embeddings, topic models or contextualized representations that can better capture the cues guiding hashtag selection. I also notice that sentiment alone does not reliably explain mismatches or detect content. To effectively identify harmful material and protect vulnerable users, we need to analyze broader aspects of word context, not just sentimental tone.

Code Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Kayden Jordan for providing access to the LIWC scoring resources and for offering guidance that strengthened the linguistic analysis in this study. I also acknowledge the developers of the LIWC-22 dictionary (Boyd, Ashokkumar, Seraj, & Pennebaker, 2022), which supported the computation of linguistic features in this project. In addition, I thank the developers of the Unsloth text classification script, whose publicly available code enabled the implementation of the LLM prediction model (Unsloth AI, 2024)

References

- Blodgett, J.; Yang, K.; Stokes, R.; Galiatsatos, P.; 1. Public Health Advocacy Dataset (PHAD). University of Arkansas Computer Vision and Image Understanding (CVIU) Lab. n.d. Available online: https://uark-cviu.github.io/projects/PHAD/#annotations.

- Blodgett, S. L.; Barocas, S.; Daumé, H., III; Wallach, H. Language (technology) is power: A critical survey of “bias” in NLP. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020; pp. 5454–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R. L.; Ashokkumar, A.; Seraj, S.; Pennebaker, J. W. The development and psychometric properties of LIWC-22; University of Texas at Austin, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth and Tobacco Use. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/php/data-statistics/youth-data-tobacco/index.html.

- Cero, I.; Luo, J.; Falligant, J. M. Lexicon-based sentiment analysis in behavioral research. Perspectives on behavior science 2024, 47(1), 283–310. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40614-023-00394-x. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guess, A. M.; Malhotra, N.; Pan, J.; Barberá, P.; Allcott, H.; Brown, T.; Tucker, J. A. How do social media feed algorithms affect attitudes and behavior in an election campaign? Science 2023, 381(6656), 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutto, C. J.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2014, Vol. 8(No. 1), 216–225. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14550. [CrossRef]

- Jim, J. R.; Talukder, M. A. R.; Malakar, P.; Kabir, M. M.; Nur, K.; Mridha, M. F. Recent advancements and challenges of NLP-based sentiment analysis: A state-of-the-art review. Natural Language Processing Journal 2024, 6, 100059. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949719124000074. [CrossRef]

- Jim, J. R.; Talukder, M. A. R.; Malakar, P.; Kabir, M. M.; Nur, K.; Mridha, M. F. Recent advancements and challenges of NLP-based sentiment analysis: A state-of-the-art review. Natural Language Processing Journal 2024, 6, 100059. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949719124000074. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. Digital 2020: Global Digital Overview 2020, 10. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview.

- Kemp, S. Digital 2025: Global Overview Report 2025, 11. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2025-global-overview-report.

- Lee, J; Krishnan-Sarin, S; Kong, G. Social Media Use and Subsequent E-Cigarette Susceptibility, Initiation, and Continued Use Among US Adolescents. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2023/22_0415.htm.

- Lee, J.; Tan, A. S.; Porter, L.; Young-Wolff, K. C.; Carter-Harris, L.; Salloum, R. G. Association between social media use and vaping among Florida adolescents, 2019. Preventing chronic disease 2021, 18, E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, K. A.; Donaldson, E. A.; Portnoy, D. B.; Robinson, J.; Neff, L. J.; Jamal, A. E-cigarette openness, curiosity, harm perceptions and advertising exposure among U.S. middle and high school students. Preventive Medicine 2018, 112, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, A. Understanding social media recommendation algorithms. Journal of Digital Media & Policy 2023, 14(1), 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon General. Social media and youth mental health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594759/.

- Öhman, E. The validity of lexicon-based sentiment analysis in interdisciplinary research. In Proceedings of the workshop on natural language processing for digital humanities, 2021, December; pp. 7–12. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2021.nlp4dh-1.2/.

- Öhman, E.; Persson, J. The limits of lexicon-based sentiment analysis for social media text. Journal of Language Technology and Computation 2021, 36(2), 45–63. Available online: https://jltec.org/articles/2021-limitations-sentiment-analysis.

- Reagan, A.J.; Mitchell, L.; Kiley, D.; et al. The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes. EPJ Data Sci. 2016, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Social media advertising spending worldwide from 2017 to 2025. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271406/advertising-revenue-of-social-networks-worldwide/.

- Tavernor, J.; El-Tawil, Y.; Mower-Provost, E. The whole is bigger than the sum of its parts: Modeling individual annotators to capture emotional variability. arXiv. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.11956.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social media and youth mental health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sg-youth-mental-health-social-media-advisory.pdf.

- University of Arkansas CVIU Lab. Public Health Advocacy Dataset (PHAD) [Dataset]. n.d. Available online: https://uark-cviu.github.io/projects/PHAD/#annotations.

- Unsloth, AI. Unsloth: Efficient fine-tuning for large language models. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/unslothai/unsloth.

- Venrick, S. J.; Kelley, D. E.; O’Brien, E.; Margolis, K. A.; Navarro, M. A.; Alexander, J. P.; O’Donnell, A. N. U.S. digital tobacco marketing and youth: A narrative review. Preventive Medicine Reports 31 2022, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, E. A.; Barrington-Trimis, J. L.; Vassey, J.; Soto, D.; Unger, J. B. Young adults’ exposure to and engagement with tobacco-related social media content and subsequent tobacco use. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2024, 26 Supplement 1, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R. Chipotle smashes TikTok records with #GuacDance challenge. Marketing Dive. 2 August 2019. Available online: https://www.marketingdive.com/news/chipotle-smashes-tiktok-records-with-guacdance-challenge/560102/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).