Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

21 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus and Its Effect on Humans

1.2. Concept of Misinformation Analysis

1.3. YouTube – A Globally Popular Social Media Platform and a Source of Misinformation

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Misinformation Analysis on YouTube

2.2. Review of Misinformation Analysis on YouTube in the context of COVID-19

- (a)

- Lack of focus on topic modeling: Several works in this field [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] have focused on content analysis of YouTube videos. However, none of the prior works in this field have analyzed the video descriptions associated with YouTube videos to interpret the underlying topics and associated themes of misinformation.

- (b)

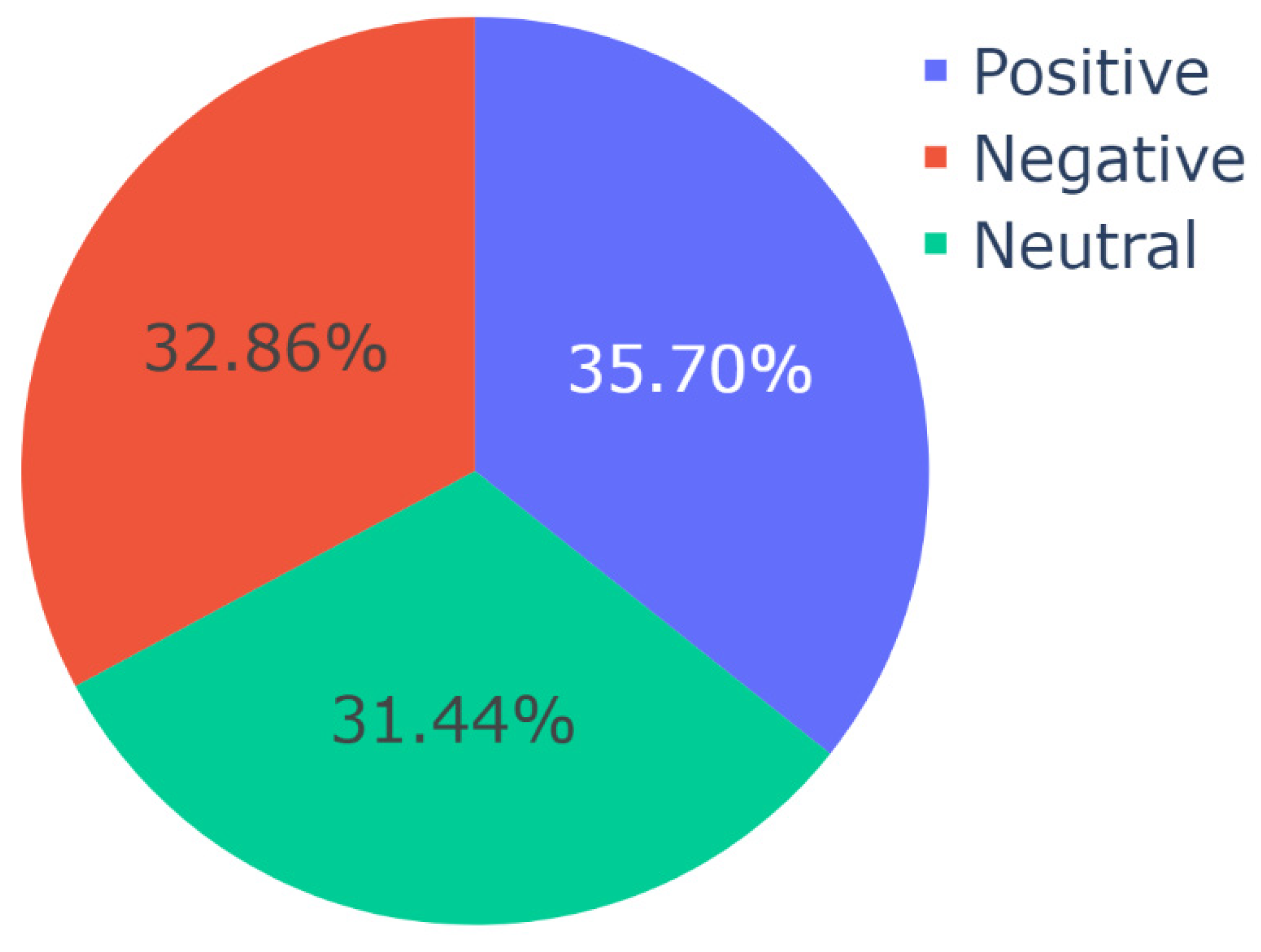

- Lack of focus on sentiment analysis related to specific themes or focus areas of misinformation dissemination on YouTube: A prior work in this field [70] performed sentiment analysis in the context of misinformation about COVID-19 on YouTube. However, that work evaluated the sentiment by considering all the videos in a collective manner and did not take into account the sentiment related to different topics or themes of misinformation those videos or the video descriptions focused on. Furthermore, that work [70] did not analyze the variations in sentiments related to different topics or themes of misinformation those videos or the associated video descriptions focused on.

- (c)

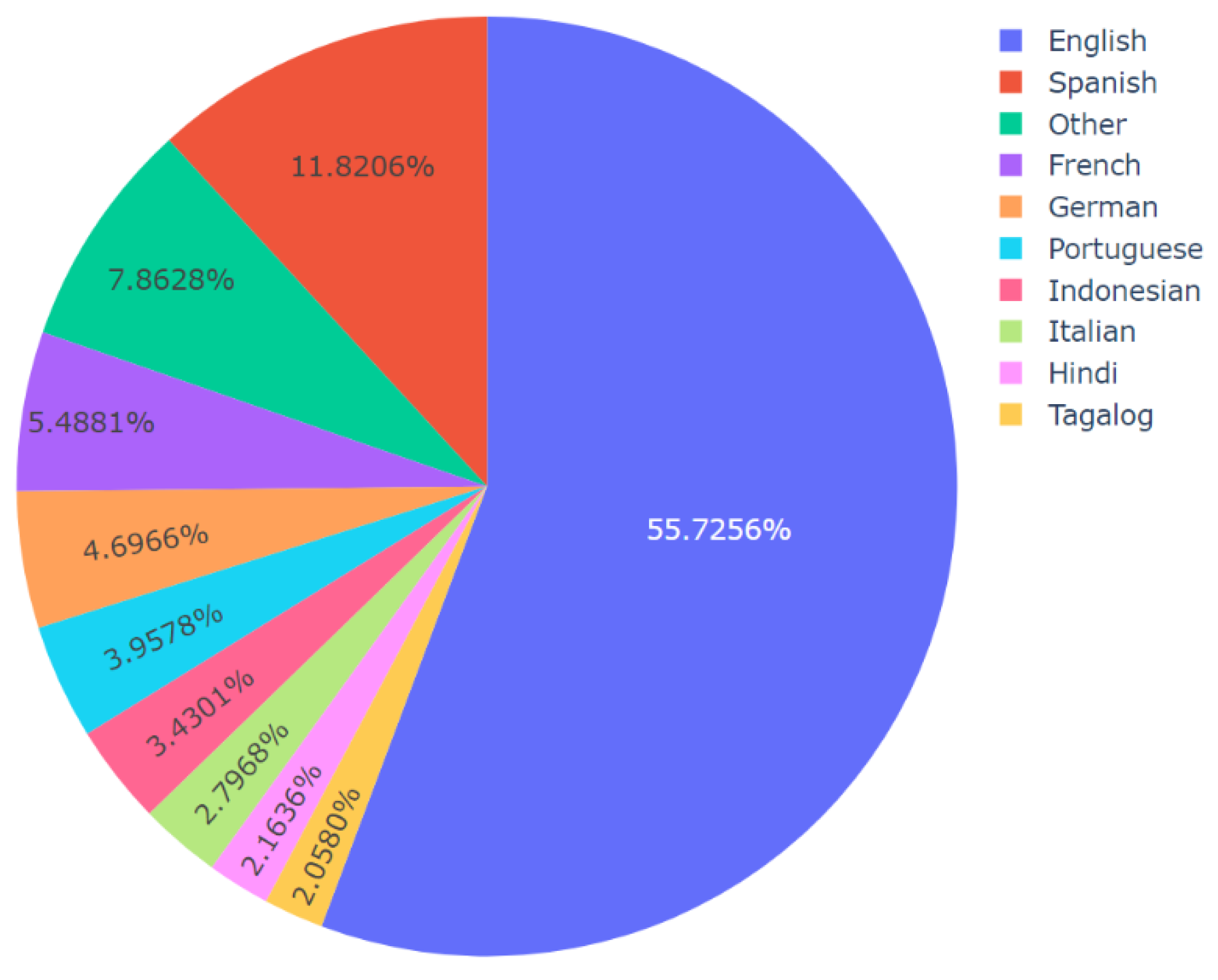

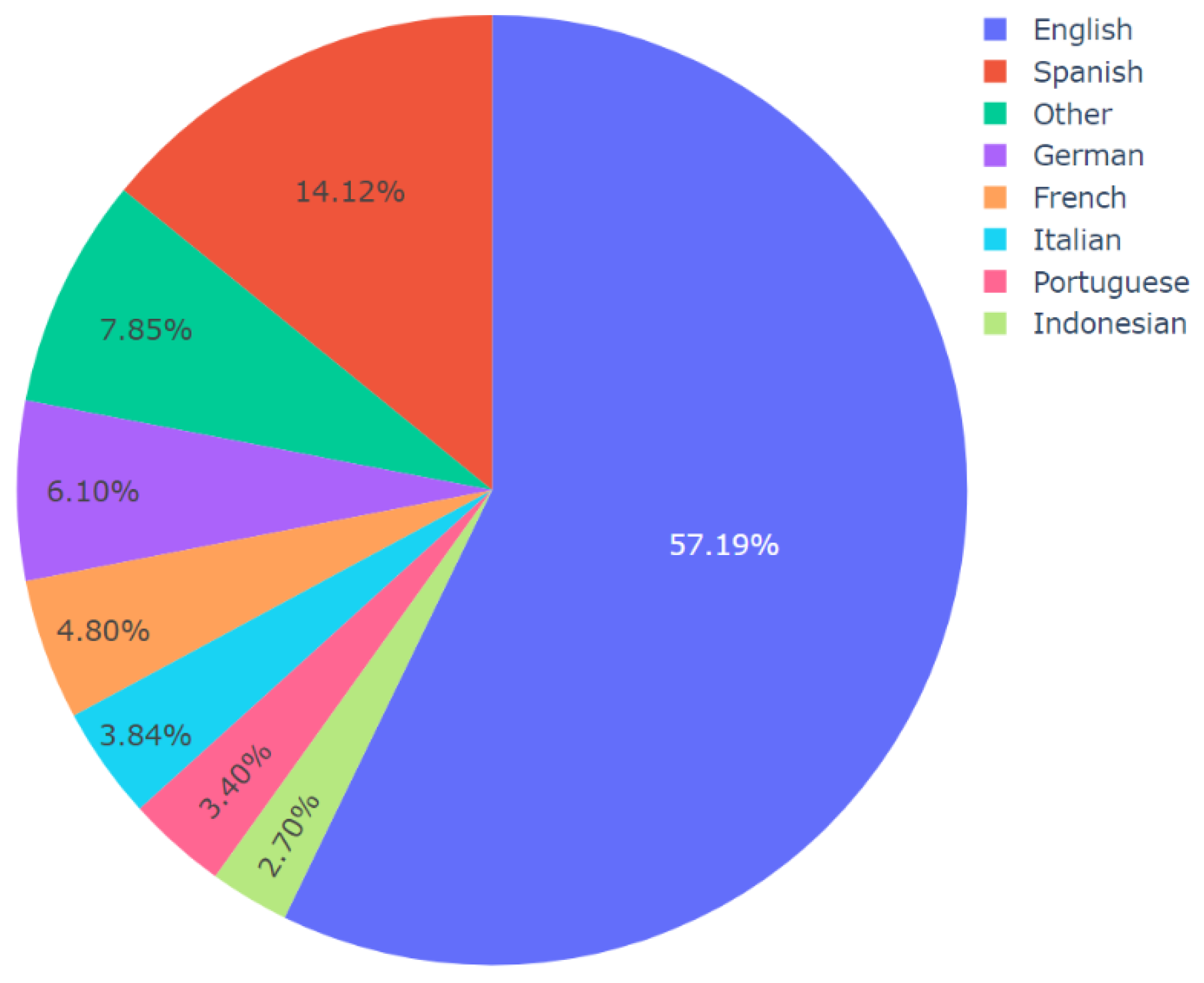

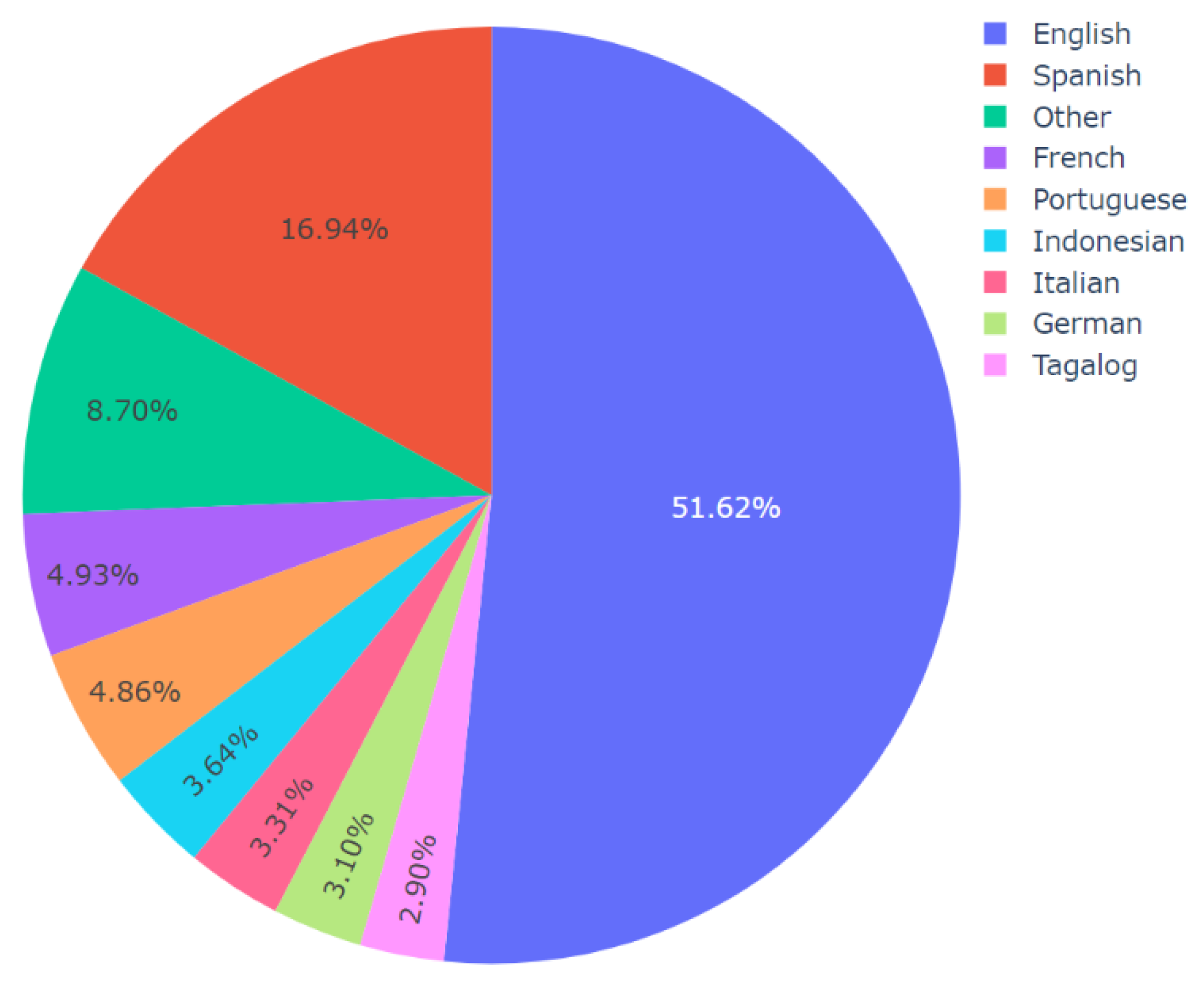

- Lack of focus on the detection and analysis of the language used in video descriptions of YouTube videos: YouTube allows the usage of multiple languages in video descriptions at the time of publication of videos. As a result, this social media platform has attracted content creators from different parts of the world who use different languages in their video descriptions. None of the prior works in this field have focused on the detection of languages used in the descriptions of videos containing misinformation or identifying trends of the same.

- (d)

- Lack of a study that took into account a considerably high number of YouTube videos: The prior works in this field, for instance, the works of Quinn et al. [73], Basch et al. [72], Li et al. [9, 67], Dutta et al. [69], Donzelli et al. [70], Christodoulou et al. [75], Serrano et al. [74], Calvo et al. [68], Machado et al. [71], and Xie et al. [76] analyzed 77, 100, 150, 150, 240, 560, 1000, 1672, 1890, 3318, and 4445 YouTube videos respectively. The number of YouTube videos investigated in these studies does not represent a considerable percentage of the total number of videos containing misinformation about COVID-19 that have been published on YouTube since the beginning of this pandemic.

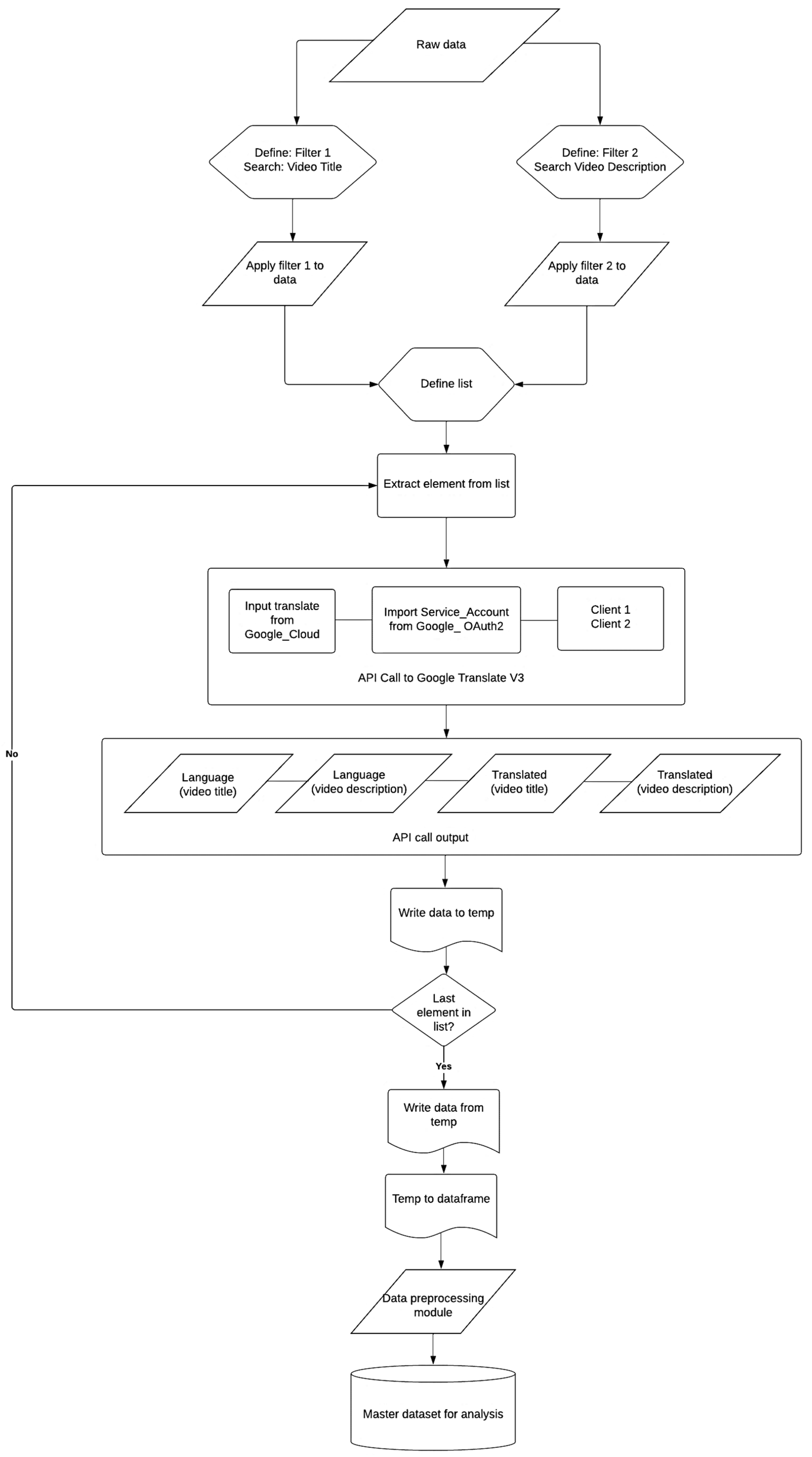

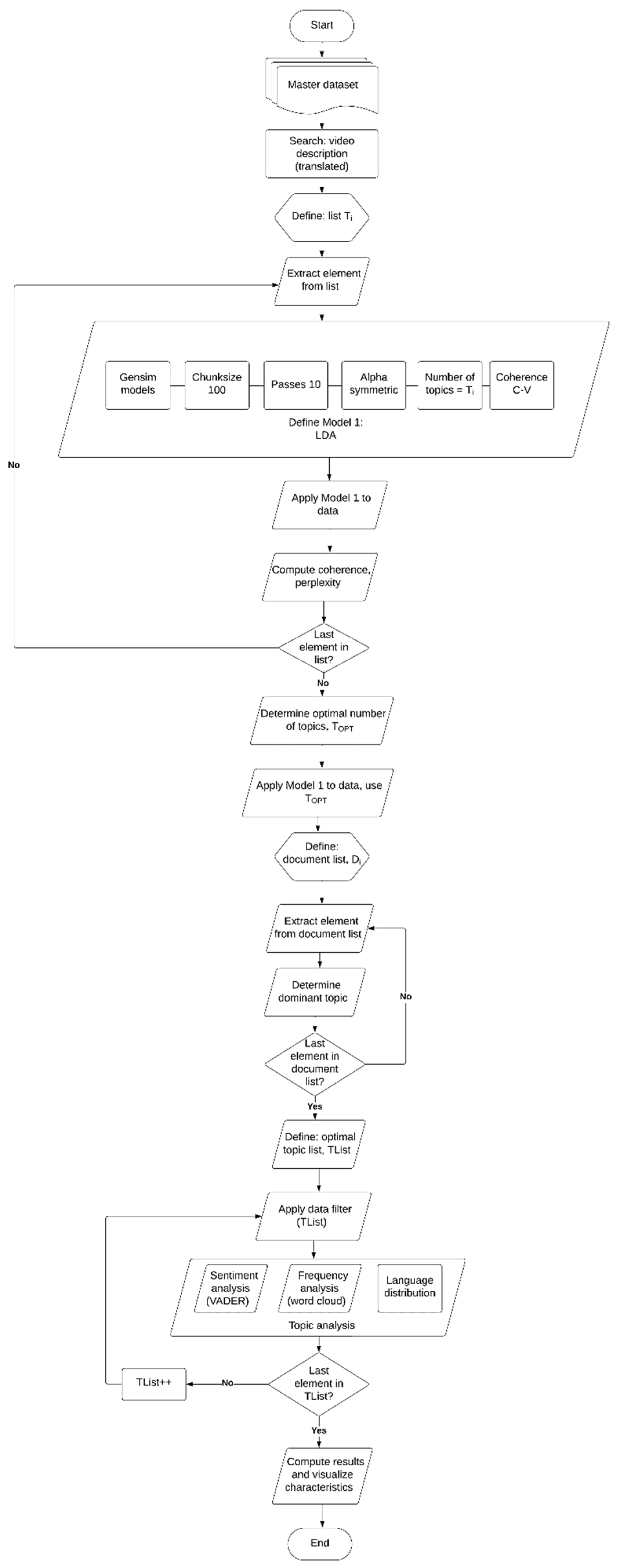

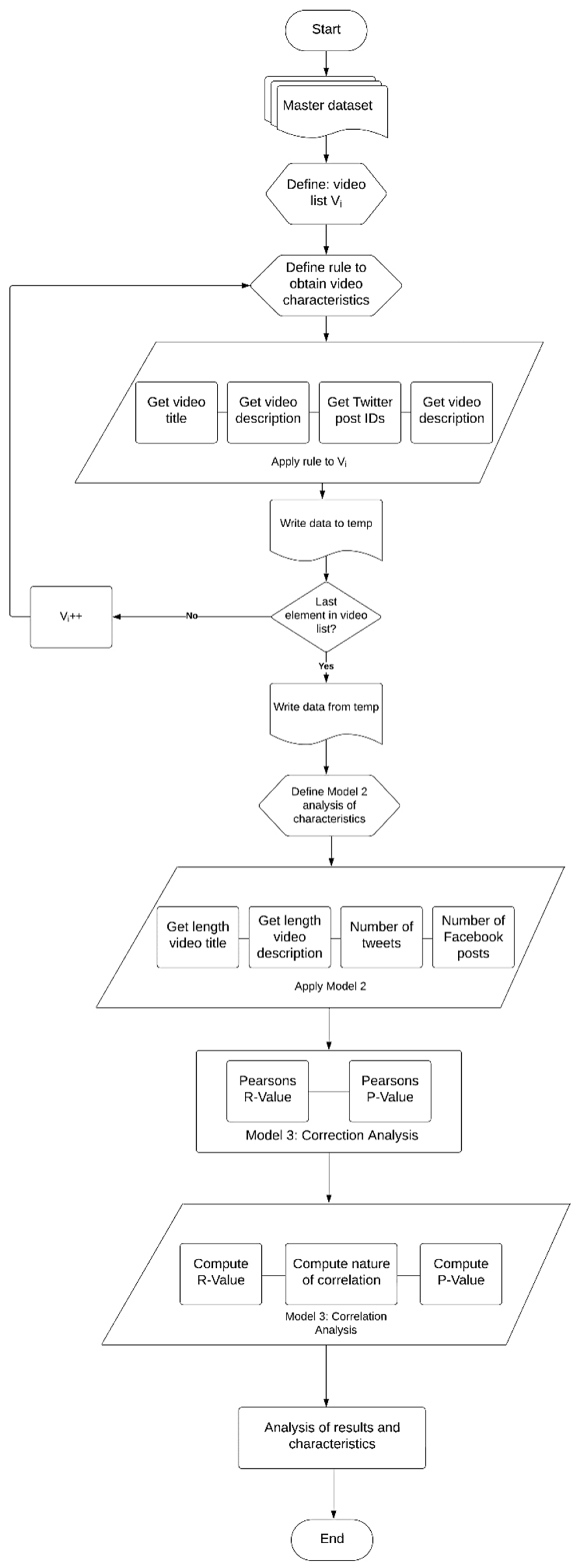

3. Methodology

- Select a multinomial distribution for each topic z from a Dirichlet distribution with parameter .

- For every document d, select a multinomial distribution from a Dirichlet distribution with parameter .

- In document d, for each word w, select a topic z, such that z from the multinomial distribution .

- Select w from the multinomial distribution .

| Algorithm 1: Determine the optimal number of topics |

|

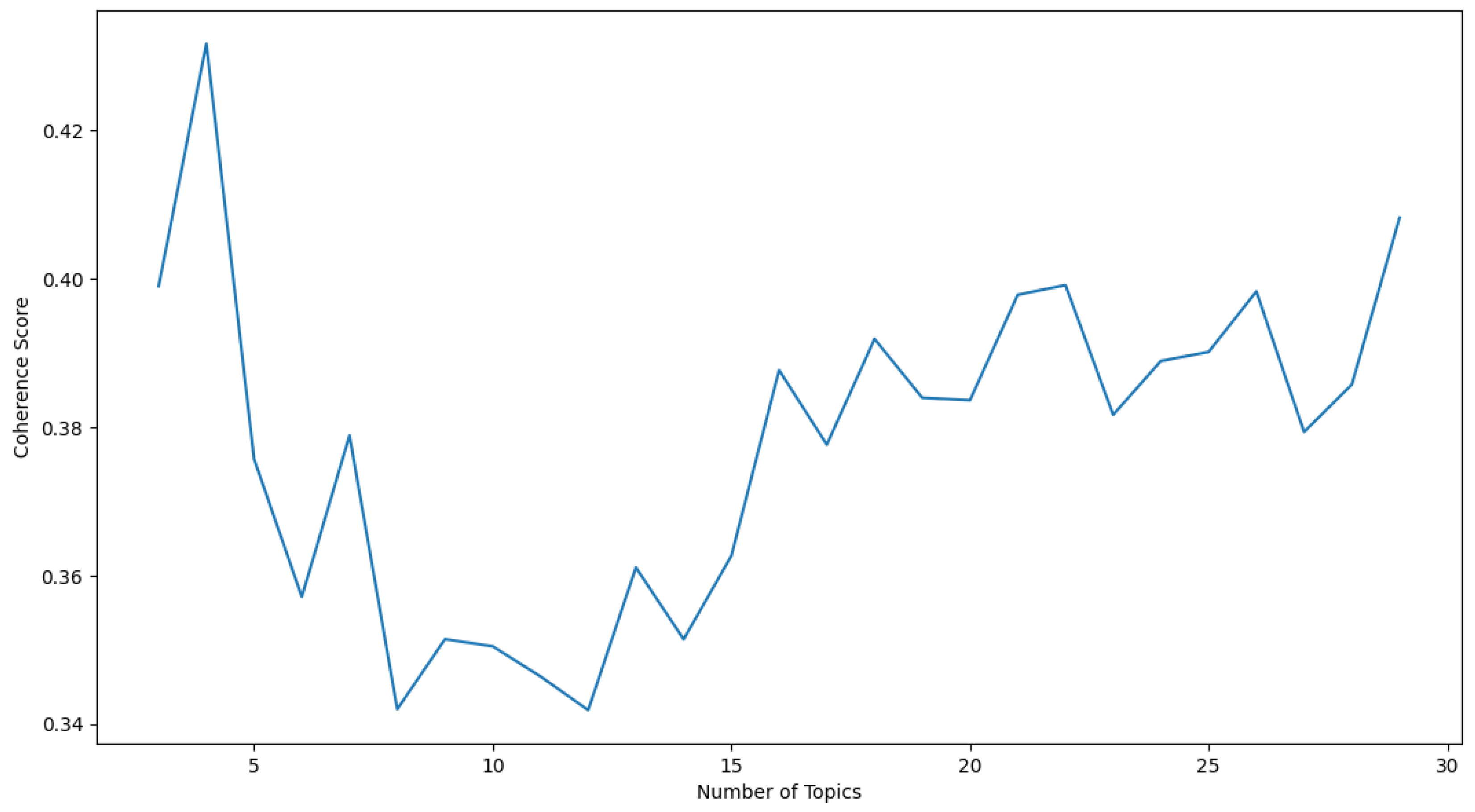

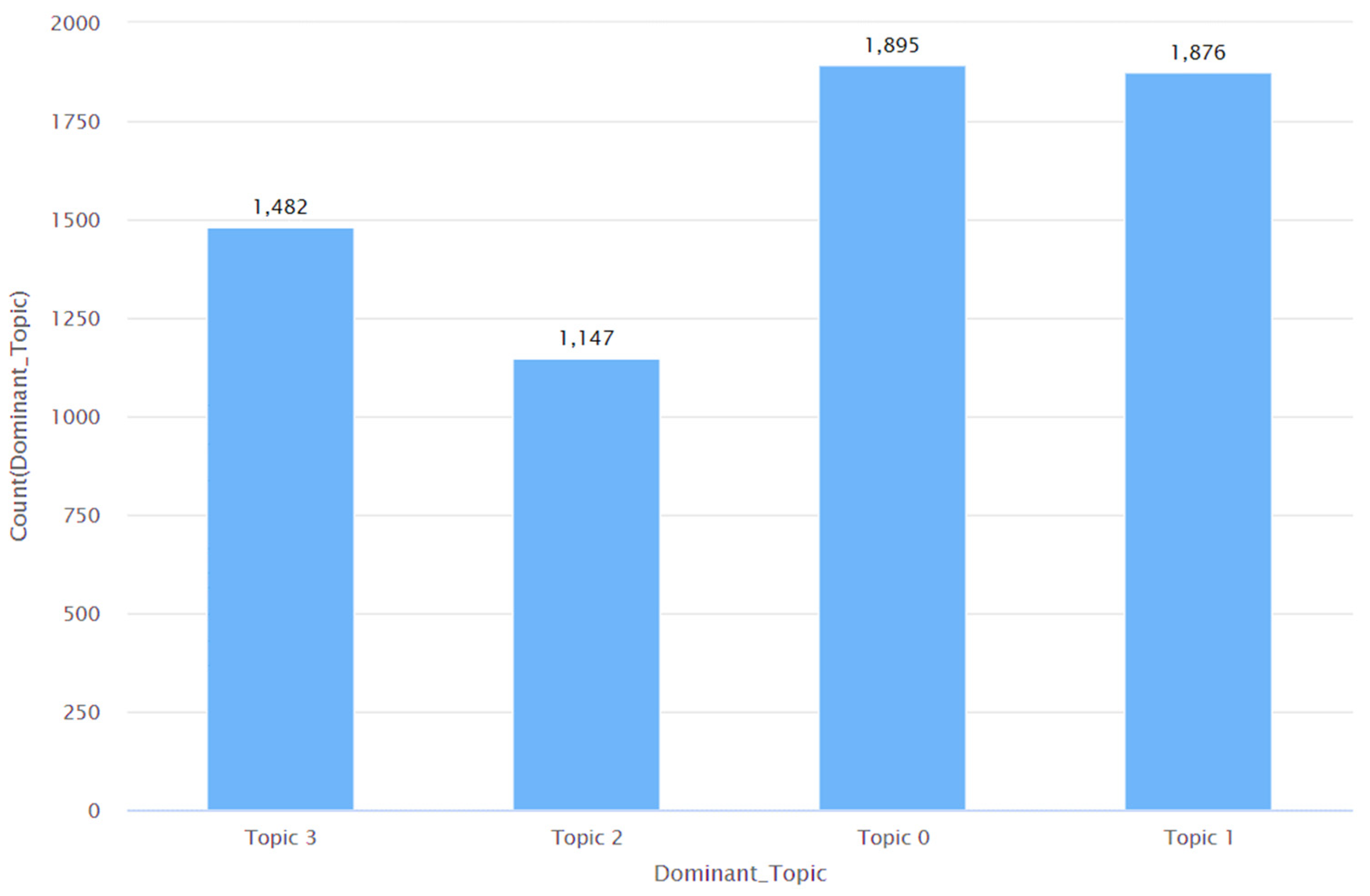

Input: Misinformation CSV Dataset Output: LDA model topics, coherence scores, perplexity, and a plot of coherence scores nltk, re, numpy, pandas, gensim, spacy, matplotlib := Import libraries df := Read Input CSV into DataFrame data := Convert 'final_description' column to list for each item in data do: item ← clean (text) address missing values end of for loop def sent_to_words(sentences): for each item in sentence do: yield(gensim.utils.simple_preprocess(str(sentence), deacc=True)) end of function data_words := tokenize the cleaned data bigram_mod = gensim.models.phrases.Phraser(bigram) trigram_mod = gensim.models.phrases.Phraser(trigram) data_words_nostops ← stopwords from data_words data_words_bigrams ← Apply bigram model to data_words_nostops nlp := Load Spacy English model for lemmatization def lemmatization(texts, allowed=['noun', 'adj', 'verb', 'adv']): texts_out = [] for each item in data do: data_lemmatized ← lemmatize token return texts end of for loop end of function id2word := Create dictionary from data_lemmatized corpus := Create corpus from data_lemmatized lda_model := Build LDA model with corpus and id2word for each number of topics from 3 to 30 do: lda_model_temp := build LDA model with current number of topics coherence_score ← coherence score of lda_model_temp perplexity ← model's perplexity end of for loop plot coherence scores against the number of topics opt_lda_model := Build an LDA model with 4 topics coherence_lda ← coherence score of opt_lda_model df_topic_sents_keywords := Extract dominant topics, percentage contributions, and keywords for each document df_dominant_topic := Convert df_topic_sents_keywords to DataFrame and reset index data := Initialize empty list for CSV data For each document in df_dominant_topic do: temp := Extract document number, dominant topic, topic percentage contribution, keywords, and text Append temp to data Write data to CSV file |

| Algorithm 2: Determine the dominant topic per video description |

|

Input: Misinformation CSV Dataset Output: LDA model topics, coherence scores, perplexity, and a plot of coherence scores nltk, re, numpy, pandas, gensim, spacy, matplotlib := Import libraries df := Read Input CSV into DataFrame data := Convert 'final_description' column to list def sent_to_words(sentences): for each item in sentence do: yield(gensim.utils.simple_preprocess(str(sentence), deacc=True)) end of function data_words := tokenize the cleaned data bigram_mod = gensim.models.phrases.Phraser(bigram) trigram_mod = gensim.models.phrases.Phraser(trigram) data_words_nostops ← stopwords from data_words data_words_bigrams ← Apply bigram model to data_words_nostops nlp := Load Spacy English model for lemmatization def lemmatization(texts, allowed=['noun', 'adj', 'verb', 'adv']): texts_out = [] for each item in data do: data_lemmatized ← lemmatize token return texts end of for loop end of function def determine_dominant_topic(): for each row_list in enumerate(ldamodel[corpus]) do: row = row_list[0] if ldamodel.per_word_topics else row_list sort (row) for each prop_topic in enumerate(row): if loop var is 0: wp = ldamodel.show_topic(topic_num) lists1 = int(topic_num), round(prop_topic, 4), topic_keywords final.append(lists1) else: break end of for loop topics_df = df(cols=[Dominant_Topic, Perc_Contribution, Topic_Keywords]) concatenate cols end of for loop end of function for each document in df_dominant_topic do: tmp.append(Document_No) tmp.append(Dominant_Topic) tmp.append(Topic_Perc_Contrib) tmp.append(Keywords) tmp.append(Text) append temp to data end of for loop write data to CSV file |

| Algorithm 3: Sentiment Analysis (using VADER) per Topic |

|

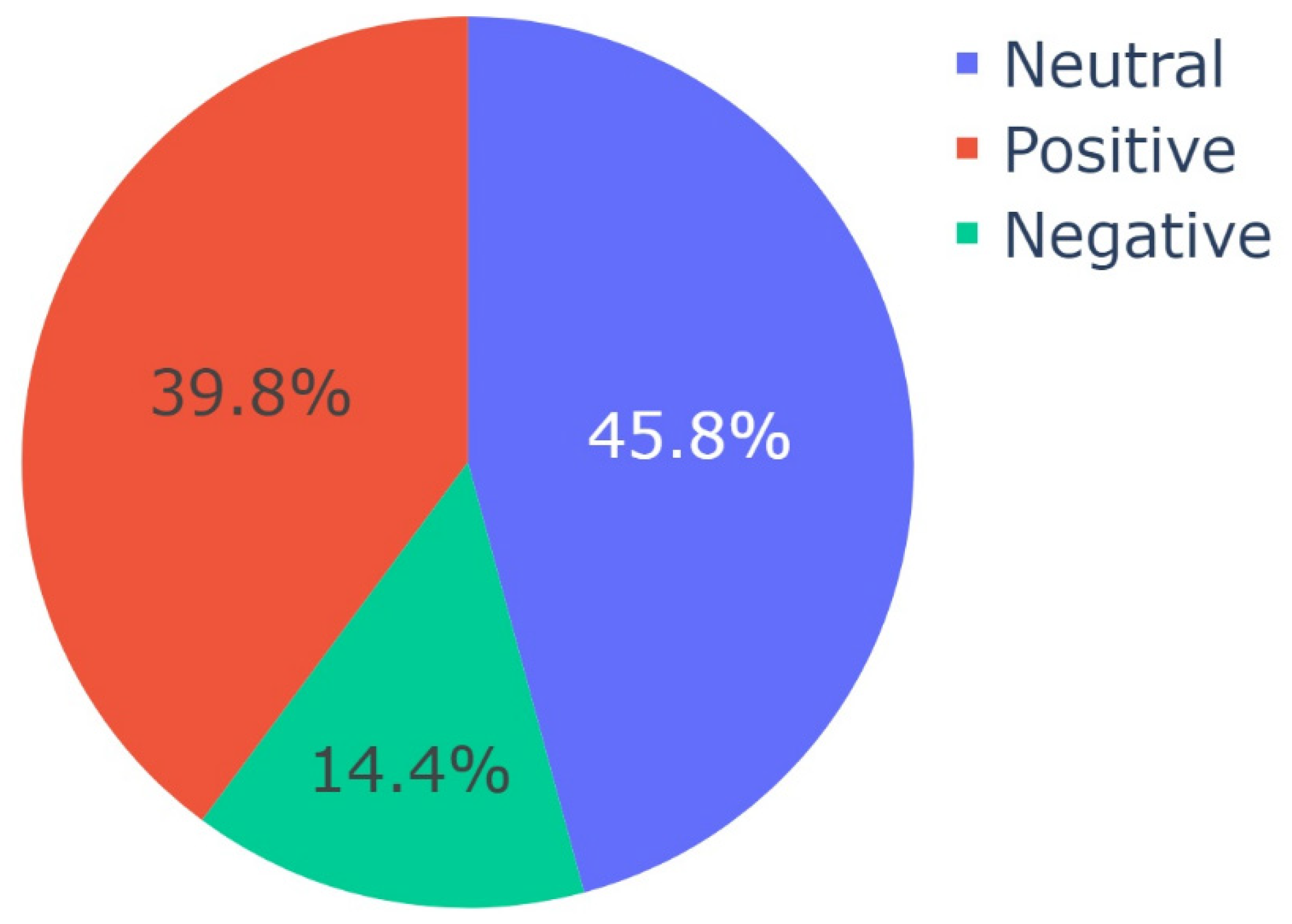

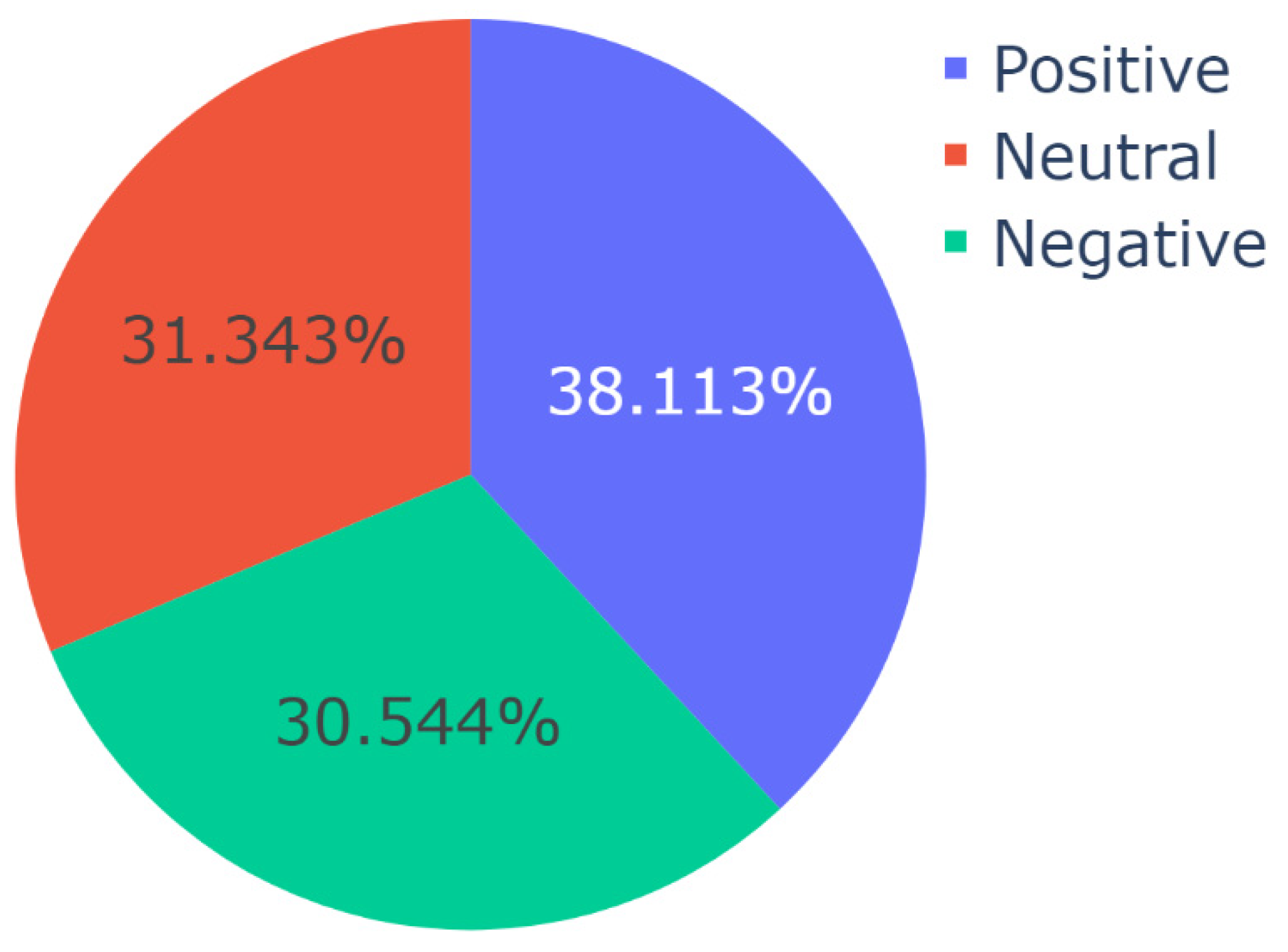

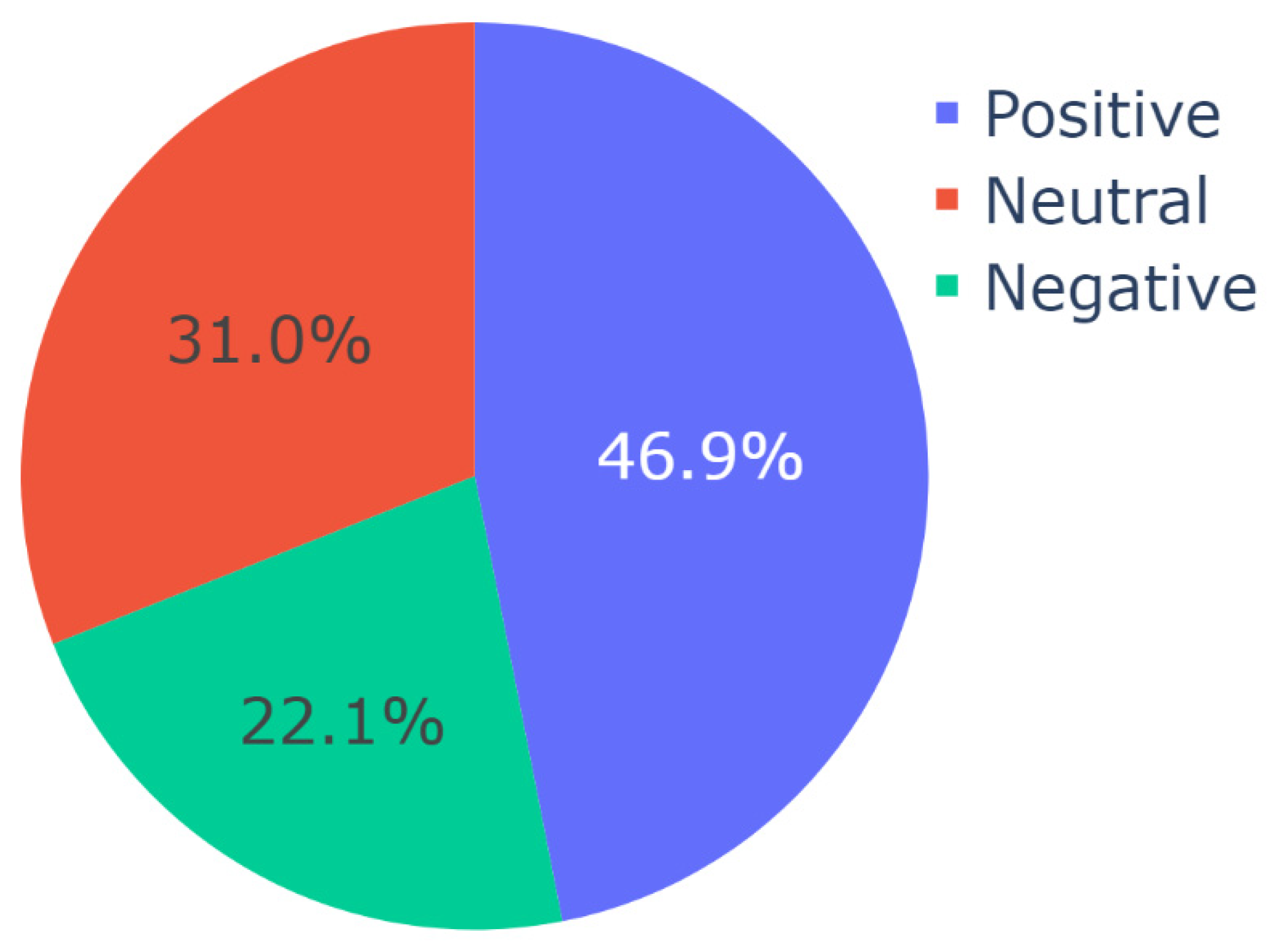

Input: CSV with Translated Video Descriptions Output: Pie charts of sentiment distribution per topic Import SentimentIntensityAnalyzer from vaderSentiment.vaderSentiment Import pandas, plotly.express sid_obj := Initialize SentimentIntensityAnalyzer ex := Read input CSV into DataFrame sentences := Convert 'final_description' column of ex to list topics := Convert 'Dominant_Topic' column of ex to list for each unique topic in topics do: sentiment := initialize list for each index i in the range of sentences do: if current topic equals topics at index i then: sentiment_dict := get polarity scores from sid_obj if sentiment_dict['compound'] ≥ 0.05 then: append "Positive" to sentiment else if sentiment_dict['compound'] ≤ -0.05 then: append "Negative" to sentiment else: append "Neutral" to sentiment end of for loop value := create list for sentiment fig := Initialize pie chart with value as values and sentiment as names save fig end of for loop |

| Algorithm 4: Language Distribution Analysis per Topic |

|

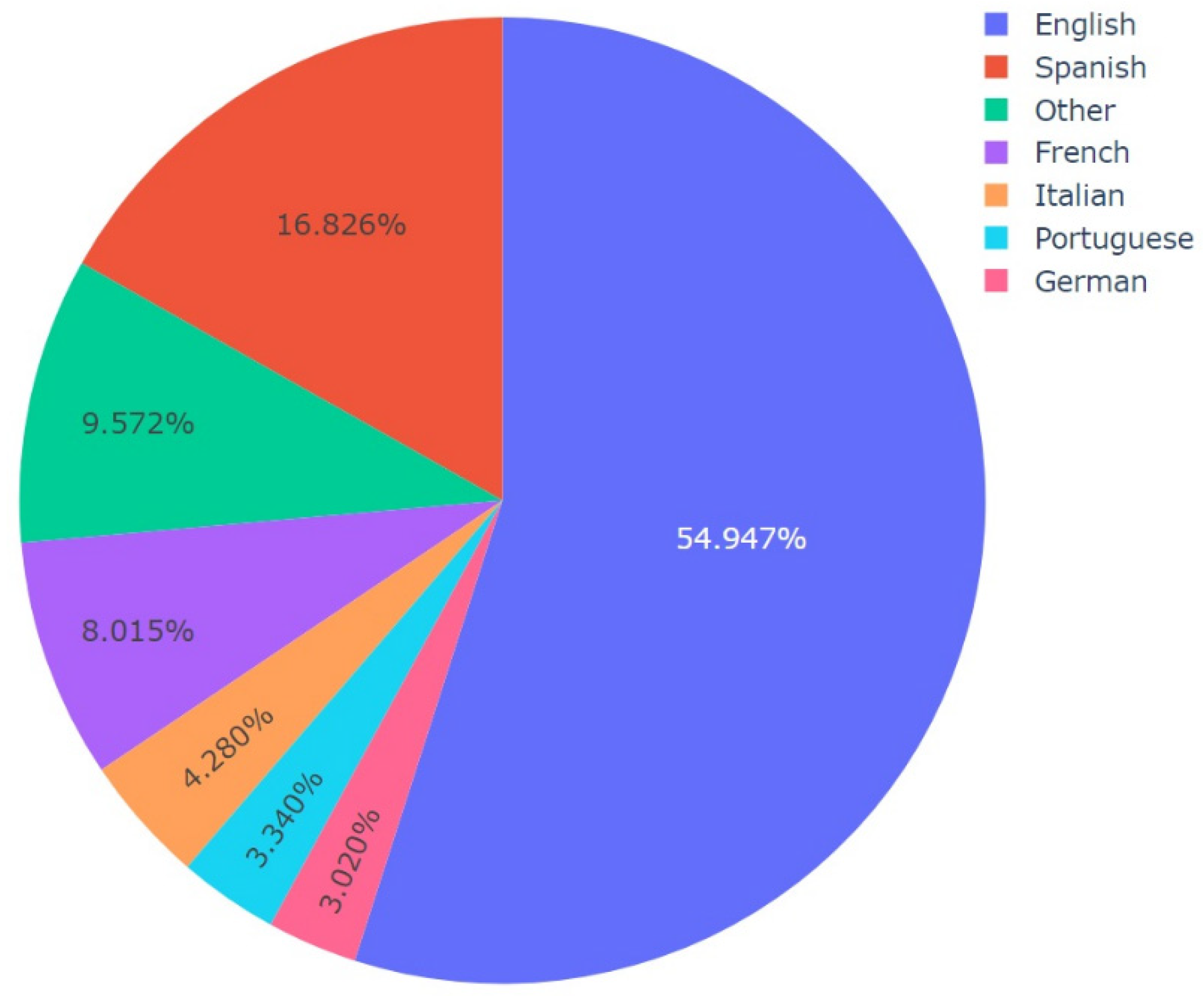

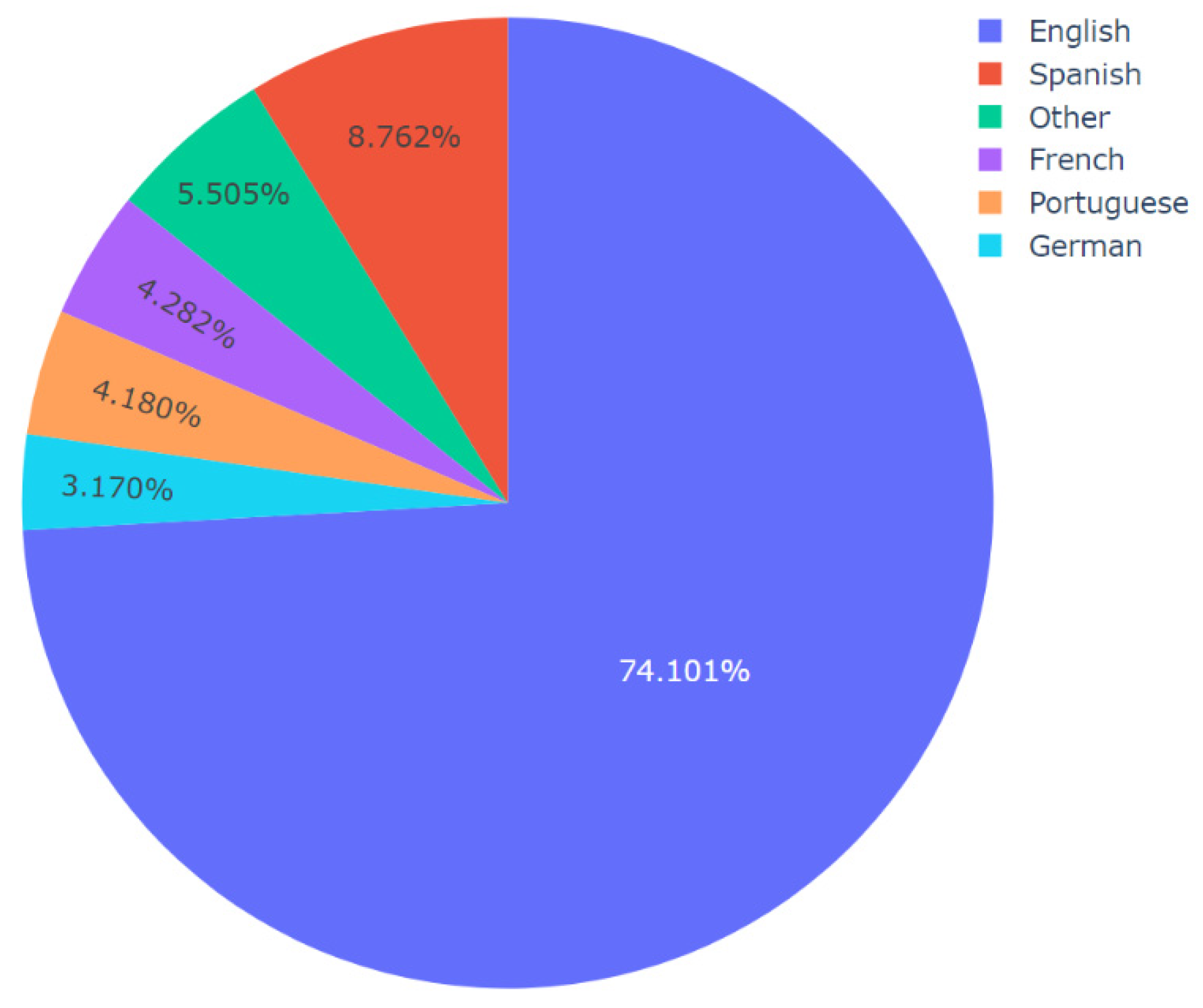

Input: Dataset CSV including predicted topics and languages Output: Pie chart visualizations of language distribution for each topic, saved as images import pandas df := Read dataset CSV topics := Convert 'Predicted_Topic' column of df to list languages := Convert 'Final_Language' column of df to list for each unique topic in topics do: language_count := dictionary for language counts in current topic filtered_languages := Filter languages (topic = current topic) for each language in filtered_languages do: increment count of language in language_count dictionary end of for loop threshold := define threshold other_count := initialize to 0 for each language, count in language_count do: if count/total number of languages < threshold then: increment other_count by count remove language from language_count if other_count > 0 then: language_count['Other'] := other_count values := extract counts from language_count names := extract languages from language_count fig := Initialize pie chart with values as counts and names as languages save fig as image with a filename indicating the topic end of for loop |

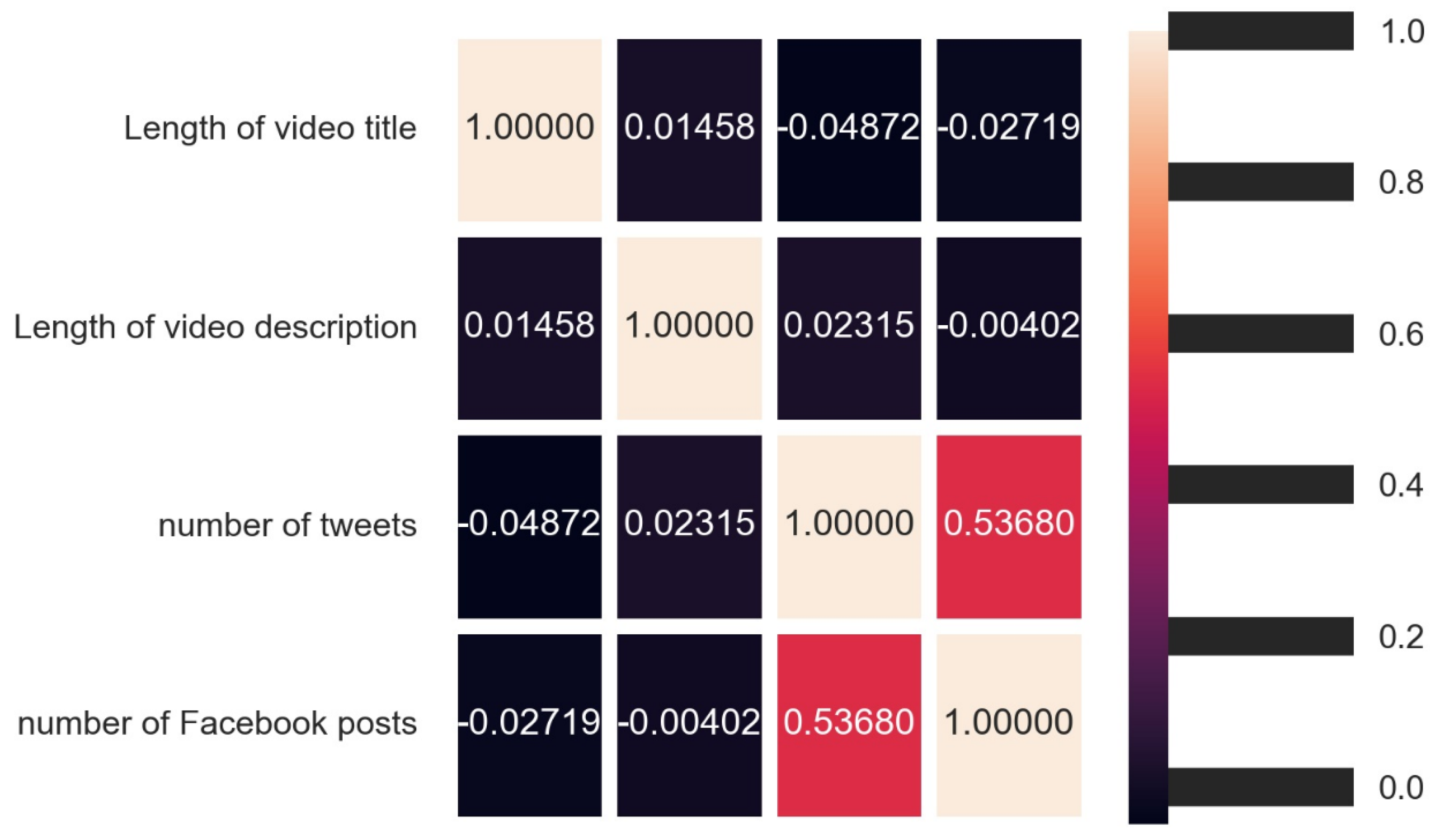

| Algorithm 5: Correlation Analysis for Video Characteristics |

|

Input: Correlation DB CSV Output: correlation matrix, heatmap, and statements of statistical significance Import numpy, pandas, matplotlib.pyplot, csv Import scipy.stats, seaborn dataset := Read Correlation DB CSV into DataFrame corr := Calculate Pearson correlation matrix from the dataset print(corr) def check_correlation(col1, col2): stat := Calculate Pearson correlation between column_1 and column_2 p_value := Get the p-value from the stat If (p_value < 0.05) then: print (correlation between <col1> and <col2> is statistically significant) end of function check_correlation ('Length of video title', 'Length of video description') check_correlation ('Length of video title', 'number of tweets') check_correlation ('Length of video title', 'number of Facebook posts') check_correlation ('Length of video description', 'number of tweets') check_correlation ('Length of video description', 'number of Facebook posts') check_correlation ('number of tweets', 'number of Facebook posts') initialize figure size and dpi for the plot plot := draw heatmap with correlation matrix, annotation, and line width display plot |

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [CrossRef]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Miraz, M.H.; Ali, M.; Excell, P.S.; Picking, R. A Review on Internet of Things (IoT), Internet of Everything (IoE) and Internet of Nano Things (IoNT). In Proceedings of the 2015 Internet Technologies and Applications (ITA); IEEE, 2015.

- Bujnowska-Fedak, M.M.; Waligóra, J.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. The Internet as a Source of Health Information and Services. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 1–16 ISBN 9783030327873.

- Zhao, Y.C.; Zhao, M.; Song, S. Online Health Information Seeking Behaviors among Older Adults: Systematic Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e34790. [CrossRef]

- Madathil, K.C.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J.; Greenstein, J.S.; Gramopadhye, A.K. Healthcare Information on YouTube: A Systematic Review. Health Informatics J. 2015, 21, 173–194. [CrossRef]

- Gabarron, E.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Armayones, M.; Lau, A.Y.S. Identifying Measures Used for Assessing Quality of YouTube Videos with Patient Health Information: A Review of Current Literature. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2013, 2, e6. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.O.-Y.; Bailey, A.; Huynh, D.; Chan, J. YouTube as a Source of Information on COVID-19: A Pandemic of Misinformation? BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002604. [CrossRef]

- Tomlein, M.; Pecher, B.; Simko, J.; Srba, I.; Moro, R.; Stefancova, E.; Kompan, M.; Hrckova, A.; Podrouzek, J.; Bielikova, M. An Audit of Misinformation Filter Bubbles on YouTube: Bubble Bursting and Recent Behavior Changes. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Srba, I.; Moro, R.; Tomlein, M.; Pecher, B.; Simko, J.; Stefancova, E.; Kompan, M.; Hrckova, A.; Podrouzek, J.; Gavornik, A.; et al. Auditing YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm for Misinformation Filter Bubbles. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst. 2023, 1, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Kirdemir, B.; Agarwal, N. Exploring Bias and Information Bubbles in YouTube’s Video Recommendation Networks. In Complex Networks & Their Applications X; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 166–177 ISBN 9783030934125.

- Osman, W.; Mohamed, F.; Elhassan, M.; Shoufan, A. Is YouTube a Reliable Source of Health-Related Information? A Systematic Review. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, S.; Ding, J.; Mazhar, L.; Khosa, F. Entering the Misinformation Age: Quality and Reliability of YouTube for Patient Information on Liposuction. Plast. Surg. (Oakv.) 2023, 31, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Brachtenbach, T.; Cardenas, R.; Pate, H.; Solis, L.; Chinnery, L.; Bowers, A.; Vassar, M. YouTube: Searching for Answers about Breast Cancer. Breast Dis. 2020, 39, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Perez-Rosas, V.; Loeb, S.; Mihalcea, R. Towards Automatic Detection of Misinformation in Online Medical Videos. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Onder, M.E.; Zengin, O. YouTube as a Source of Information on Gout: A Quality Analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yesudhas, D.; Srivastava, A.; Gromiha, M.M. COVID-19 Outbreak: History, Mechanism, Transmission, Structural Studies and Therapeutics. Infection 2021, 49, 199–213. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yan, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase from COVID-19 Virus. Science 2020, 368, 779–782. [CrossRef]

- Shereen, M.A.; Khan, S.; Kazmi, A.; Bashir, N.; Siddique, R. COVID-19 Infection: Emergence, Transmission, and Characteristics of Human Coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 91–98. [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Hu, N.; Lou, J.; Chen, K.; Kang, X.; Xiang, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Liu, N.; Liu, D.; et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 Infection in Beijing. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Alimohamadi, Y.; Sepandi, M.; Taghdir, M.; Hosamirudsari, H. Determine the Most Common Clinical Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene 2020, 61, E304. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.R.; Martin, M.R.; Martin, J.D.; Kuhn, P.; Hicks, J.B. Modeling the Onset of Symptoms of COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Vraga, E.K.; Bode, L. Defining Misinformation and Understanding Its Bounded Nature: Using Expertise and Evidence for Describing Misinformation. Polit. Commun. 2020, 37, 136–144. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Ecker, U.; Lewandowsky, S. Misinformation and How to Correct It. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 1–17.

- van der Linden, S. Misinformation: Susceptibility, Spread, and Interventions to Immunize the Public. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 460–467. [CrossRef]

- Almaliki, M. Online Misinformation Spread: A Systematic Literature Map. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Information System and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Del Vicario, M.; Bessi, A.; Zollo, F.; Petroni, F.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Stanley, H.E.; Quattrociocchi, W. The Spreading of Misinformation Online. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 554–559. [CrossRef]

- Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance; Proctor, R., Schiebinger, L.L., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, 2008.

- Diethelm, P.; McKee, M. Denialism: What Is It and How Should Scientists Respond? Eur. J. Public Health 2008, 19, 2–4. [CrossRef]

- Altay, S.; Berriche, M.; Acerbi, A. Misinformation on Misinformation: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 205630512211504. [CrossRef]

- Biggest Social Media Platforms 2023 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Top Websites in the World - Top Rankings October 2023 Available online: https://www.semrush.com/website/top/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Mohsin, M. 10 YouTube Statistics That You Need to Know in 2023 Available online: https://www.oberlo.com/blog/youtube-statistics (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Countries with the Highest Monthly Traffic Volume to Youtube.com 2022 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1357163/youtube-global-monthly-visits-by-country/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Blogger, G.M.I. YouTube Statistics 2023 [Users by Country + Demographics] Available online: https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/youtube-users-statistics/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Average Daily Time Spent on Social Media (Latest 2023 Data) Available online: https://www.broadbandsearch.net/blog/average-daily-time-on-social-media (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- YouTube App User Engagement in Selected Markets 2022 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1287283/time-spent-youtube-app-selected-countries/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- ChannelMeter YouTube’s Top Countries Available online: https://medium.com/@ChannelMeter/youtubes-top-countries-47b0d26dded (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Global YouTube User Distribution by Gender 2023 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1287032/distribution-youtube-users-gender (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Global YouTube User Age & Gender Distribution 2023 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1287137/youtube-global-users-age-gender-distribution/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- YouTube Penetration in Selected Countries and Territories 2023 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1219589/youtube-penetration-worldwide-by-country/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Posner, M. YouTube Amplifies Misinformation and Hatred, but Here’s What We Can Do about It Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelposner/2022/06/17/youtube-amplifies-misinformation-and-hatred-but-heres-what-we-can-do-about-it/?sh=496312b51592 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Milmo, D. YouTube Is Major Conduit of Fake News, Factcheckers Say Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jan/12/youtube-is-major-conduit-of-fake-news-factcheckers-say (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Pandey, A.; Patni, N.; Singh, M.; Sood, A.; Singh, G. YouTube as a Source of Information on the H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38, e1–e3. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Poudel, D.; Karmacharya, P.; Pathak, A.; Mahmood, M.; Aryal, M.; Donato, A. Youtube as a Source of Information on Ebola Virus Disease. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 7, 306. [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.; Das, D.; Barman, B.; Borah, P. Are Internet Videos Useful Sources of Information during Global Public Health Emergencies? A Case Study of YouTube Videos during the 2015–16 Zika Virus Pandemic. Pathog. Glob. Health 2018, 112, 320–328. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.S.; D’Souza, S.; Strand, N.; Anderson, A.; Vogt, M.N.P.; Olatoye, O. YouTube as a Source of Medical Information on the Novel Coronavirus 2019 Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 935–942. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Sounderajah, V.; Daniels, E.; Acharya, A.; Clarke, J.; Yalamanchili, S.; Normahani, P.; Markar, S.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. The Reliability and Quality of YouTube Videos as a Source of Public Health Information Regarding COVID-19 Vaccination: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e29942. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.; Juneja, P.; Mitra, T. Measuring Misinformation in Video Search Platforms: An Audit Study on YouTube. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 4, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, P.; Bhuiyan, M.M.; Mitra, T. Assessing Enactment of Content Regulation Policies: A Post Hoc Crowd-Sourced Audit of Election Misinformation on YouTube. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- Yoon, H.Y.; You, K.H.; Kwon, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Rha, S.Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Lee, S.-C. Understanding the Social Mechanism of Cancer Misinformation Spread on YouTube and Lessons Learned: Infodemiological Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e39571. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Rauchfleisch, A.; Córdova, Y. Comparative Approaches to Mis/Disinformation| Fighting Zika with Honey: An Analysis of YouTube’s Video Recommendations on Brazilian YouTube. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 19.

- Tang, L.; Fujimoto, K.; Amith, M. (tuan); Cunningham, R.; Costantini, R.A.; York, F.; Xiong, G.; Boom, J.A.; Tao, C. “Down the Rabbit Hole” of Vaccine Misinformation on YouTube: Network Exposure Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23262. [CrossRef]

- Betschart, P.; Pratsinis, M.; Müllhaupt, G.; Rechner, R.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Gratzke, C.; Schmid, H.-P.; Zumstein, V.; Abt, D. Information on Surgical Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia on YouTube Is Highly Biased and Misleading. BJU Int. 2020, 125, 595–601. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Trang, T.; Doong, J.; Kang, S.; Chien, A.L. Misinformation Is Prevalent in Psoriasis-Related YouTube Videos. Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 22. [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Sengupta, S.; Butaney, M.; Macaluso, J.N., Jr; Czarniecki, S.W.; Robbins, R.; Braithwaite, R.S.; Gao, L.; Byrne, N.; Walter, D.; et al. Dissemination of Misinformative and Biased Information about Prostate Cancer on YouTube. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 564–567. [CrossRef]

- Goobie, G.C.; Guler, S.A.; Johannson, K.A.; Fisher, J.H.; Ryerson, C.J. YouTube Videos as a Source of Misinformation on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 572–579. [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, S.; Maheswaran, Y.; Chan, C.; Hanna, L.; Ashrafian, H.; Markar, S.R.; Sounderajah, V.; Alverdy, J.C.; Darzi, A. Misinformation about the Human Gut Microbiome in YouTube Videos: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e37546. [CrossRef]

- Selvi, I.; Baydilli, N. An Analysis of Misleading YouTube Videos on Urological Conditions: What to Do about the Danger of Spreading Misinformation of the YouTube Videos? World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 885–886. [CrossRef]

- Kobilke, L.; Markiewitz, A. The Momo Challenge: Measuring the Extent to Which YouTube Portrays Harmful and Helpful Depictions of a Suicide Game. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1. [CrossRef]

- Inwood, O.; Zappavigna, M. Ambient Affiliation, Misinformation and Moral Panic: Negotiating Social Bonds in a YouTube Internet Hoax. Discourse Commun. 2021, 15, 281–307. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, K.; Kempegowda, P. Appraising Unmet Needs and Misinformation Spread about Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in 85,872 YouTube Comments over 12 Years: Big Data Infodemiology Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e49220. [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.; Porter, E.K.; Lee, U.J. Examination of Information and Misinformation about Urinary Tract Infections on TikTok and YouTube. Urology 2022, 168, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Taylor, J.; Borin, J.F.; Mihalcea, R.; Perez-Rosas, V.; Byrne, N.; Chiang, A.L.; Langford, A. Fake News: Spread of Misinformation about Urological Conditions on Social Media. Eur. Urol. Focus 2020, 6, 437–439. [CrossRef]

- Albarracin, D.; Romer, D.; Jones, C.; Hall Jamieson, K.; Jamieson, P. Misleading Claims about Tobacco Products in YouTube Videos: Experimental Effects of Misinformation on Unhealthy Attitudes. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e229. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.O.-Y.; Pastukhova, E.; Brandts-Longtin, O.; Tan, M.G.; Kirchhof, M.G. YouTube as a Source of Misinformation on COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008334. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, D.; Cano-Orón, L.; Llorca-Abad, G. COVID-19 Vaccine Disinformation on YouTube: Analysis of a Viewing Network. Commun. Soc. 2022, 35, 223–238. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Beriwal, N.; Van Breugel, L.M.; Sachdeva, S.; Barman, B.; Saikia, H.; Nelson, U.-A.; Mahdy, A.; Paul, S. YouTube as a Source of Medical and Epidemiological Information during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study of Content across Six Languages around the Globe. Cureus 2020. [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, G.; Palomba, G.; Federigi, I.; Aquino, F.; Cioni, L.; Verani, M.; Carducci, A.; Lopalco, P. Misinformation on Vaccination: A Quantitative Analysis of YouTube Videos. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018, 14, 1654–1659. [CrossRef]

- Tokojima Machado, D.F.; Fioravante de Siqueira, A.; Rallo Shimizu, N.; Gitahy, L. It-Which-Must-Not-Be-Named: COVID-19 Misinformation, Tactics to Profit from It and to Evade Content Moderation on YouTube. Front. Commun. 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Basch, C.E.; Basch, C.H.; Hillyer, G.C.; Meleo-Erwin, Z.C.; Zagnit, E.A. YouTube Videos and Informed Decision-Making about COVID-19 Vaccination: Successive Sampling Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e28352. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, E.K.; Fenton, S.; Ford-Sahibzada, C.A.; Harper, A.; Marcon, A.R.; Caulfield, T.; Fazel, S.S.; Peters, C.E. COVID-19 and Vitamin D Misinformation on YouTube: Content Analysis. JMIR Infodemiology 2022, 2, e32452. [CrossRef]

- Medina Serrano, J.C.; Papakyriakopoulos, O.; Hegelich, S. NLP-Based Feature Extraction for the Detection of COVID-19 Misinformation Videos on YOuTUbe. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on NLP for COVID-19 at ACL 2020; Verspoor, K., Cohen, K.B., Dredze, M., Ferrara, E., May, J., Munro, R., Paris, C., Wallace, B., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2020.

- Christodoulou, C.; Salamanos, N.; Leonidou, P.; Papadakis, M.; Sirivianos, M. Identifying Misinformation on YouTube through Transcript Contextual Analysis with Transformer Models. arXiv [cs.CL] 2023.

- Xie, J.; Chai, Y.; Liu, X. An Interpretable Deep Learning Approach to Understand Health Misinformation Transmission on YouTube. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 55th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS 2022; IEEE Computer Society, 2022; pp. 1470–1479.

- Vayansky, I.; Kumar, S.A.P. A Review of Topic Modeling Methods. Inf. Syst. 2020, 94, 101582. [CrossRef]

- Movahedi Nia, Z.; Bragazzi, N.; Asgary, A.; Orbinski, J.; Wu, J.; Kong, J. Mpox Panic, Infodemic, and Stigmatization of the Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual Community: Geospatial Analysis, Topic Modeling, and Sentiment Analysis of a Large, Multilingual Social Media Database. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wheldon, C.; Dunn, A.G.; Tao, C.; Huo, J.; Zhang, R.; Prosperi, M.; Guo, Y.; Bian, J. Mining Twitter to Assess the Determinants of Health Behavior toward Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in the United States. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 225–235. [CrossRef]

- Pruss, D.; Fujinuma, Y.; Daughton, A.R.; Paul, M.J.; Arnot, B.; Albers Szafir, D.; Boyd-Graber, J. Zika Discourse in the Americas: A Multilingual Topic Analysis of Twitter. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216922. [CrossRef]

- Odlum, M.; Lee, H.; Broadwell, P.; Kuang, D.; Yoon, S. What Can We Learn about the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Outbreak from Tweets? Big Data Inf. Anal. 2017, 2, 7–7. [CrossRef]

- Missier, P.; Romanovsky, A.; Miu, T.; Pal, A.; Daniilakis, M.; Garcia, A.; Cedrim, D.; da Silva Sousa, L. Tracking Dengue Epidemics Using Twitter Content Classification and Topic Modelling. In Current Trends in Web Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 80–92 ISBN 9783319469621.

- Chen, L.; Hossain, K.S.M.T.; Butler, P.; Ramakrishnan, N.; Prakash, B.A. Flu Gone Viral: Syndromic Surveillance of Flu on Twitter Using Temporal Topic Models. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining; IEEE, 2014.

- Knuutila, A. A Dataset of Covid-Related Misinformation Videos and Their Spread on Social Media Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4557828.

- Package Google.Cloud.Translation.V3 Available online: https://cloud.google.com/translate/docs/reference/rpc/google.cloud.translation.v3 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Jelodar, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and Topic Modeling: Models, Applications, a Survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 15169–15211. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Croft, W.B. LDA-Based Document Models for Ad-Hoc Retrieval. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Tsytsarau, M.; Palpanas, T. Survey on Mining Subjective Data on the Web. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2012, 24, 478–514. [CrossRef]

- Saberi, B.; Saad, S. Sentiment Analysis or Opinion Mining: A Review Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/296919524.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9783031021459.

- Medhat, W.; Hassan, A.; Korashy, H. Sentiment Analysis Algorithms and Applications: A Survey. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2014, 5, 1093–1113. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. Recognizing Contextual Polarity in Phrase-Level Sentiment Analysis. Proc. HLT/EMNLP’05, Vancouver, Canada 2005, 347–354.

- Do, H.H.; Prasad, P.W.C.; Maag, A.; Alsadoon, A. Deep Learning for Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis: A Comparative Review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 118, 272–299. [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Rao, Y.; Wu, L.; Sun, L. Issues and Challenges of Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022, 13, 845–863. [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A Parsimonious Rule-Based Model for Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Text. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2014, 8, 216–225. [CrossRef]

- Veena, G.; Vinayak, A.; Nair, A.J. Sentiment Analysis Using Improved Vader and Dependency Parsing. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT); IEEE, 2021.

- Nguyen, H.; Veluchamy, A.; Diop, M.; Iqbal, R. Comparative Study of Sentiment Analysis with Product Reviews Using Machine Learning and Lexicon-Based Approaches. SMU Data Science Review 2018, 1, 7.

- Franzese, M.; Iuliano, A. Correlation Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology; Elsevier, 2019; Vol. 1–3, pp. 706–721 ISBN 9780128114322.

- Sedgwick, P. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient. BMJ 2012, 345, e4483–e4483. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tong, Y.; Ji, Q. Active Image Labeling and Its Application to Facial Action Labeling. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008; pp. 706–719 ISBN 9783540886853.

- Woods, D.D.; Dekker, S.; Cook, R.; Johannesen, L.; Sarter, N. Behind Human Error; 2nd Edition.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2017; ISBN 9781315568935.

| Video Number | Video Description |

|---|---|

| Topic 0, Theme: Promotion and Outreach Efforts | |

| Video #1 | Subscribe and ring the bell to be notified of a new video La chl |

| Video #2 | Please share the video with your friends and acquaintances so that this current information spreads like an avalanche. Follow us on our Teleg |

| Video #3 | Please like share and Subscribe the Channel friends |

| Video #4 | If you like this video, subscribe and a little click on the little hand at the bottom of the video would make me very happy Thank you |

| Video #5 | Be aware from Corona Virus but Don t Panic Share as much as you can Subscribe our channel |

| Topic 1, Theme: Treatment for COVID-19 | |

| Video #1 | Coronavirus has a cure, the light is born at the end of the tunnel Sucesso Brasil Covid has a cure |

| Video #2 | Allama Zameer Akhtar Naqvi talks about coronavirus treatment |

| Video #3 | CHLOROQUINE THE CURE FOR COVID Today the announced a possible cure for You heard it on The HighWire first |

| Video #4 | According to Patanjali the new Ayurvedic medicine Coronil From Patanjali developed by the team can cure a COVID patient in five to days Ref news o |

| Video #5 | Message from Doctor Merci Blanco to the mayor of Bogotá on how to eliminate CORONAVIRUS with Chlorine Dioxide |

| Topic 2, Theme: Conspiracy Theories regarding COVID-19 | |

| Video #1 | The Corona Virus was produced intentionally to close the Borders to produce the World Crisis Famine and War Everything Depends on Us if We Return to D |

| Video #2 | In this diabolical plan, you will best see how all the NOM actors from the press, the medical system, the international system of those days, experts and |

| Video #3 | Everything that has been handled with the pandemic has been a well-forged lie coordinated from the highest sphere of power in the world, a great manipulation. |

| Video #4 | This coronavirus has been created for a long time but it has only now spread around the world |

| Video #5 | False Pandemic increasingly evident HY MICROCHIP will be the next thing to fuck up human life with suffocating hypercontrol, you want it because it will be time |

| Topic 3, Theme: COVID-19 and Politics | |

| Video #1 | Infection models that garunteed MILLIONS DEAD in usa alone That all politicians used got our economy destroyed now we must open up msm is lying to us to push |

| Video #2 | They are African Leaders selling us into Slavery Agian Lockdown Ban Lifted in Ghana Good or Bad |

| Video #3 | Why governors are denying treatment for covid |

| Video #4 | Approved by the Ministry of Health of Bolivia, more and more people use it |

| Video #5 | The president of Madagascar Andry Rajoelina has officially launched a local herbal remedy claimed to prevent and cure the novel coronavirus Tests have been |

| Work | Content Analysis |

Correlation Analysis | Sentiment Analysis | Topic Modeling | Topic Specific Sentiment Analysis |

Topic Specific Language Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinn et al. [73] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Basch et al. [72] | ✓ | |||||

| Li et al. [9] | ✓ | |||||

| Li et al. [67] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Dutta et al. [69] | ✓ | |||||

| Donzelli et al. [70] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Christodoulou et al. [75] | ✓ | |||||

| Serrano et al. [74] | ✓ | |||||

| Calvo et al. [68] | ✓ | |||||

| Machado et al. [71] | ✓ | |||||

| Xie et al. [76] | ✓ | |||||

| Thakur et al. [this work] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Work | Number of Videos Analyzed |

|---|---|

| Quinn et al. [73] Basch et al. [72] Li et al. [9] Li et al. [67] Dutta et al. [69] |

77 100 150 150 240 |

| Donzelli et al. [70] Christodoulou et al. [75] Serrano et al. [74] Calvo et al. [68] Machado et al. [71] Xie et al. [76] |

560 1000 1672 1890 3318 4445 |

| Thakur et al. [this work] | 8122 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).