1. Introduction

GRAPHS are mathematical structures that stem from pairwise interactions between entities, which are widely used in a diverse range of domains. Due to their expressive power in modeling relational data, graph generative models (GGMs), with the goal of learning the underlying statistical patterns of observed graphs and generating new samples, have attracted significant attention [

1]. This capability has enabled impactful applications across various domains, including scientific research, social network analysis, and protein design [

2].

In general, we focus on two broad categories of graphs [

3] widely adopted in GGMs: (1) Geometric graphs, typically consisting of a large set of small graphs (e.g., chemical compounds or protein graphs) [

2]. (2) Scale-free graphs, which are typically large graphs (possibly with several components) where node degrees follow a power-law distribution. These graphs are often generated by the temporal evolution of nodes, as seen in social networks or user-item bipartite graphs [

4].

Naturally, the algorithms used for these two types of graphs differ significantly due to their differing structural formation mechanisms [

5]. To achieve unbiased coverage of the entire set of relevant graphs, GGMs can be accordingly categorized into two probabilistic modeling methods: (1) For scale-free graphs, early works focused primarily on statistical-based simulation models, which encode hypothesized rules for network formation [

6,

7]. These models aim to replicate key topological properties observed in real-world networks, such as power-law degree distribution. More recently, LLM-based simulators have revisited these classical mechanisms by directly simulating interactions between nodes through language-guided roles and rules [

8,

9]. Unlike traditional statistical-based simulation, which relies on predefined rules for graph generation, LLM-based role-play agents simulate human-like interactions, where the evolution of the graph is governed by dynamic and context-sensitive interactions. However, the need for tailored models to capture different properties of scale-free graphs complicates the integration of these methods into a unified framework. (2) For geometric graphs, given their smaller scale and rich supervisory information, deep learning-based generative models have become the dominant approach. With the rise of deep learning, techniques such as auto-regressive (AR) models, variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), normalizing flows, and denoising diffusion models have become popular for learning expressive graph distributions and generating high-quality samples [

2].

In recent years, substantial progress has been made in GGMs, leading to a comprehensive and diverse range of methods in the literature. However, despite the fundamental differences in graph categories and generation mechanisms, existing surveys often overlook these distinctions [

10,

11]. To address this gap, we present a comprehensive survey that systematically categorizes GGMs based on graph categories (geometric vs. scale-free) and probabilistic modeling methods (simulation-based vs. deep learning-based). As shown in the

Awesome-Graph-Generation resource

1, we present a comprehensive review of the field to help the community track its progress. The rest of the survey is organized as follows:

In

Section 2 and

Section 3, we introduce a three-axis taxonomy of GGMs, encompassing their target graph categories, graph attribute modality and probabilistic modeling methods. In

Section 4, we further delve into the specific model architectures employed within each framework, including neural network architectures and modeling strategies. In

Section 5, we summarize and categorize the evaluation metrics used to assess GGMs. In

Section 6, we present the various applications of GGMs. Finally, in

Section 7, we discuss open challenges and promising research directions.

Figure 1.

The organization of this survey. Our survey systematically examines GGMs across five key aspects: graph types categorization, probabilistic modeling methods, model architectures, evaluation metrics and applications. For each aspect, we discuss both geometric graph generators and scale-free graph generators, analyzing their unique characteristics and challenges.

Figure 1.

The organization of this survey. Our survey systematically examines GGMs across five key aspects: graph types categorization, probabilistic modeling methods, model architectures, evaluation metrics and applications. For each aspect, we discuss both geometric graph generators and scale-free graph generators, analyzing their unique characteristics and challenges.

1.1. Related Works

Existing surveys relevant to our topic fall into three strands.

Statistical-based GGMs

The first strand synthesizes graph generation from classical graph theory [

3]. These surveys emphasize random graph models and analytical properties, but they predate the modern wave of deep generative neural networks for graphs.

Deep learning-based GGMs

The second strand reviews neural generative models for graphs, offering complementary emphases and taxonomies. For example, [

10,

12] primarily categorize methods by backbone paradigms: auto-regressive, autoencoder-based, RL-based and etc. While [

1] analyzes techniques for both unconditional and conditional generation. [

13] focuses on diffusion-based graph generators.

LLM-based social simulation

This strand surveys LLM-based social simulation, focusing on comparisons to traditional agent-based modeling [

8,

14]. These works examine how interactions and social influence propagate over network structures (with nodes as individuals and edges as relations). But they rarely focus on the formation and topology of the social networks.

Despite their breadth, the above strands share two blind spots. First, existing surveys rarely classify the graph dataset themselves. In practice, graph categories imply different inductive biases that necessitate distinct GGMs, yet current surveys treat these regimes uniformly. Second, existing surveys neglect LLM-based GGMs. Growing interest in LLM-based agent simulation has elevated network evolution to a central role. Yet to our knowledge, no survey unifies this emerging research [

15]. To address these gaps, we propose: (a) a graph-category-centric taxonomy that distinguishes between geometric, scale-free, and general graphs; (b) a systematic organization of the probabilistic modeling methods, neural network architectures, and modeling strategies in GGMs; and (c) the first structured survey of LLM-based GGMs, analyzing their unique capabilities compared to conventional GGMs while identifying future directions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of two graph categories: (1) Geometric Graph, (2) Scale-Free Graph. Each graph category is illustrated with representative types of graphs, highlighting their distinct structural formation mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Comparison of two graph categories: (1) Geometric Graph, (2) Scale-Free Graph. Each graph category is illustrated with representative types of graphs, highlighting their distinct structural formation mechanisms.

2. Preliminaries

Formally, for one given graph dataset

, a Graph Generative Model (GGM) can be abstractly represented as

where

p denotes the probabilistic modeling method that defines the data distribution

, and

A denotes the model architecture that parameterizes and learns this distribution. In the following sections, we systematically describe the categorization and construction of

,

p, and

A.

2.1. Graph Category

This survey focuses on the two most representative categories of graph datasets commonly used in GGMs: geometric graphs and scale-free graphs. Other graph structures, such as those derived from text clustering or semantic relations, knowledge graphs, abstract syntax trees, and workflow DAGs, are excluded due to their task-specific nature and distinct structural characteristics.

Geometric Graph

A geometric graph is a graph whose vertices correspond to points in a geometric space (typically

, often

or 3), and whose edges are determined by geometric or spatial relationships between these points [

16]. In practical applications, geometric graphs arise in domains such as molecular modeling (e.g., atoms as 3D points connected by bonds), protein structure analysis, and transportation networks. For geometric graph datasets, we typically observe a set of

M graphs, denoted by

. GGMs seek to learn the underlying data distribution

and synthesize new samples

.

Scale-Free Graph

Compared to geometric graphs, scale-free graphs are rare in practice [

17]. A scale-free graph is characterized by a power-law degree distribution, where a few nodes act as high-degree hubs while most nodes have small degrees [

18]. Such networks commonly arise in social and technological domains. For scale-free graph datasets, typically only one large graph (

) is given. Therefore, the goal of the generation model is to learn the distribution of the single large graph

and generate a new graph

.

In both cases, GGMs that sample from the learned distribution must preserve essential topological patterns (e.g., connectivity, motifs) and attribute correlations (e.g., node/edge features). The distinct formation mechanisms of graph categories require different designs for GGMs.

2.2. Graph Representation

One graph G is defined as a quadruple , where is the node set with N nodes, each node is associated with an a-dimensional attribute vector . These encodings are organized in a matrix . is the edge set, representing pairwise connections between nodes, each edge is associated with b-dimensional attribute vector . Similarly, a matrix groups the one-hot encoding of each edge. We use to denote the adjacency matrix. In graph generation models, the graph representation can mainly be categorized into two types: sequential representation and matrix representation.

Sequential Representation

In sequential representation,

G is represented by a sequence of components

, where each

is a generation unit. The distribution

is the joint (or conditional) probability over these components. The components are hierarchically defined: (1) Node-level:

represents a single node, capturing atomic building blocks for graph construction [

19]. (2) Edge-level:

corresponds to an edge, encoding pairwise connections between nodes [

20,

21]. (3) Motif-level:

encodes a higher-order subgraph pattern (e.g., triangles, cliques, or star motifs) as a

k-tuple of nodes

, enabling the generation of complex structural motifs [

22]. This hierarchical decomposition enables flexible control over the generation process, allowing for progressive refinement from coarse-grained structures to fine-grained details. This kind of graph representation is more widely used in auto-regressive generation models [

19,

23], where the graph is constructed sequentially by conditioning on previously generated components. A critical aspect of sequential representation is the ordering of components

S. The choice of ordering strategy (e.g., breadth-first traversal [

24], depth-first traversal [

25] or random walk [

26]) directly impacts the model’s ability to generate structurally valid graphs.

Matrix Representation

The matrix representation encodes the graph

G using its adjacency matrix

, where

if

and 0 otherwise. Matrix representation is widely used in one-shot generation models [

27,

28,

29], where the entire graph is generated in a single step. These approaches leverage the adjacency matrix

A and attribute matrices (e.g.,

for node features) as inputs. Despite their efficiency in encoding global structure, matrix representations face scalability challenges for large

N, as their memory complexity scales quadratically

due to the adjacency matrix. Consequently, matrix-based models are often restricted to small-scale graphs, such as molecular or protein structures, where

N remains modest.

3. Probabilistic Modeling

To generate these three types of graphs, two core probabilistic modeling methods have emerged. Firstly,

deep learning-based models, which use neural architectures to learn and sample complex graph distributions automatically [

3]. They are particularly effective for multi-graph settings (e.g., geometric graphs) where rich supervision enables expressive modeling. Some models treat both geometric and scale-free graphs similarly by learning from sampled subgraphs of scale-free graphs, making them applicable to general graphs. Secondly,

simulation-based models, which instantiate predefined mechanisms (e.g., preferential attachment) to reproduce target network characteristics [

30]. Recent LLM-based simulation models develop stable interaction patterns for graph generation through LLM-based agents [

31]. These models are especially suitable for single graph settings (e.g., scale-free graphs), where scalability and controllability are crucial.

Building upon this foundation, we propose a three-axis taxonomy for graph generative models as illustrated in

Figure 1. Firstly, GGMs are classified by the types of graphs they generate: geometric, scale-free, or general graphs (including both geometric and scale-free). Secondly, they are categorized based on the attributes of the generated graphs, including non-attribute, categorical/numeric attributes, and textual attributes, reflecting the increasing complexity and richness of graph information. Finally, they are grouped by their underlying probabilistic modeling methods, namely deep learning-based and simulation-based approaches. All models are organized chronologically to highlight methodological advancements.

3.1. Deep Learning-Based Probabilistic Modeling

Deep learning-based probabilistic modeling can be broadly divided into two paradigms:

explicit and

implicit probabilistic modeling [

32]. Explicit models define explicit density forms and allow exact likelihood inference of graph data. This family includes auto-regressive models, Variational Autoencoders (VAE), and flow-matching models.

In contrast, implicit models directly learn a transformation from the prior to the data distribution [

33]. Classical approaches in this category include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and diffusion models.

Auto-regressive Models

Given an input sequential representation

S of a graph

G, at step

i, auto-regressive models [

34] learn the conditional probability distribution

over graph components using the chain rule of probability, where

represents the subsequence of graph components prior to step

i.

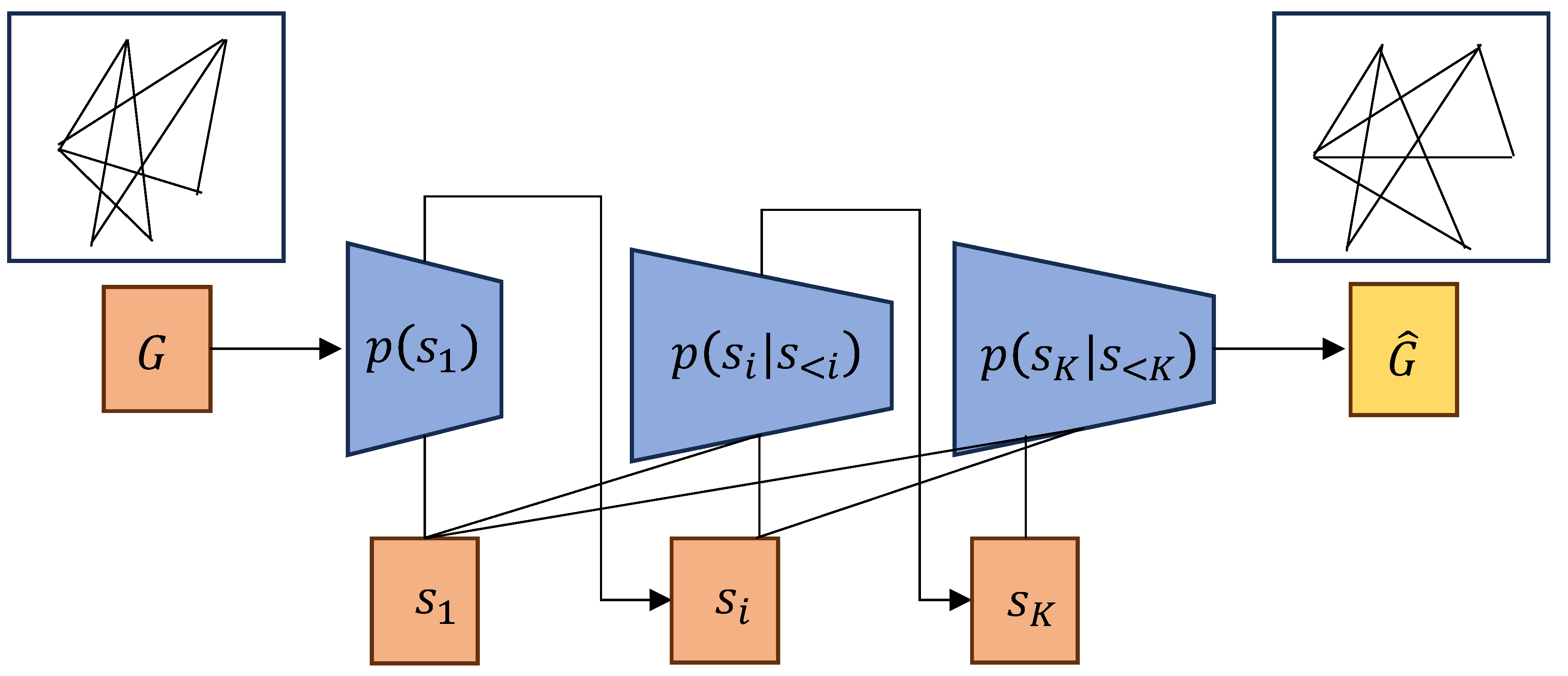

Figure 3.

Auto-regressive models for graph generation. The model generates the next component based on the previously generated components .

Figure 3.

Auto-regressive models for graph generation. The model generates the next component based on the previously generated components .

Auto-regressive models are commonly employed for sequential graph representation [

19,

23], where the input sequence consists of nodes, edges, or motifs, and the model predicts the next node or edge based on the previously generated sequence. Specifically, this model factorizes the generation process into sequential steps, each determining the next action based on the current subgraph. The general formulation of auto-regressive models is expressed as:

This approach enables the flexible generation of graphs with varying structures and sizes, typically through the sequential sampling of nodes, edges or motifs. Representative works, such as GraphRNN [

19] and NetGAN [

26], utilize an node-list sequential representation, which add new nodes one at a time before connecting these nodes with edges to the previously generated components. In contrast, models like BiGG [

20] utilize an edge-list sequential representation and employ a tree-structured auto-regressive approach for generating the edges associated with each node. GraphGPT(2) [

35] employs a motif-list based representation, which translates graphs into sequences of tokens representing nodes, edges, and attributes in a reversible manner using Eulerian paths.

VAE Models

Figure 4.

VAE models for graph generation.

Figure 4.

VAE models for graph generation.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [

36] provide a robust framework for data representation by learning a probabilistic mapping between the graph domain and a latent space. Specifically, a graph encoder

maps input graphs

G to a low-dimensional continuous latent representation

, while a graph decoder

reconstructs the graph from sampled latent variables [

27]. This formulation approximates the intractable posterior distribution

through a variational approximation

, which is optimized via the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO):

where the first term (reconstruction loss) measures the fidelity of graph reconstruction, and the second term (KL divergence) enforces the latent distribution to align with a prior

, typically a standard Gaussian. Graph-structured VAEs (GraphVAEs) typically parameterize the encoder and decoder using graph neural networks (GNNs), such as GCNs [

37] or GATs [

38], to capture relational inductive biases. Notable variants include: NeVAE [

39], which incorporates masking strategies to ensure chemical validity in molecular graph generation; Graphite [

40], which integrates spectral graph convolutions into both encoder and decoder, leveraging permutation invariance and locality in node representations; MiCaM [

41], which uses an iterative subgraph merging algorithm based on frequency to identify frequent molecular fragments (motifs) and their inter-connections.

While these methods excel in static graph generation, where node/edge structures remain fixed. However, real-world graphs are inherently dynamic: their topologies and features evolve over time [

11]. To address this, recent works like VRDAG [

42] introduce temporal modeling capabilities, which employs a bidirectional message-passing mechanism to encode both structural and attribute information, combined with a recurrence state updater to capture temporal dependencies in graph generation.

Figure 5.

Flow matching models for graph generation.

Figure 5.

Flow matching models for graph generation.

Flow Matching Models

Normalizing flows estimate the density of graph data

by establishing an invertible and deterministic mapping between latent variables and graph structures via the change of variables theorem [

43]. These models employ a sequence of invertible functions

to transform a simple prior distribution

(e.g., a standard Gaussian) into a complex data distribution

. The inverse function

enables graph generation by transforming latent samples back into the data space. For a graph

, the forward transformation is defined as:

where

is sampled from the prior, and

represents the latent variable corresponding to the graph

G. During training, the log-likelihoods of observed graph samples are maximized to update the parameters of the forward transformations

:

The determinant of the Jacobian (det) in normalizing flows quantifies how a learnable transformation alters the volume of the data space. MoFlow [

44] is an early work that adopts a two-step generation process, which first generates molecular bonds (edges) using a Glow-based flow and then predicts atom types (nodes) through a graph-conditional flow conditioned on the bond structure. A subsequent post-processing correction ensures chemical validity by resolving structural issues such as invalid valencies. Building on this, GraphDF [

45] leverages discrete normalizing flows based on invertible modulo shift transforms to map latent variables to graph structures, achieving exact invertibility and mitigating the limitations inherent in continuous relaxation approaches. Most recently, GGFlow [

46] introduces discrete flow matching with optimal transport, and incorporates an edge-augmented graph transformer to directly model interactions among chemical bonds, thereby further improving molecular graph generation.

GAN Models

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are a class of implicit generative models that have achieved significant success in the computer vision domain and have since been extended to graph data [

47]. A typical GAN framework consists of a generator, which learns to produce synthetic graphs from random noise, and a discriminator, which aims to distinguish generated graphs from real ones. The generator

and discriminator

are trained in an adversarial min-max objective functions:

To address the unique challenges of graph data, including structural dependencies, permutation invariance, and conditional graph generation, various GAN-based models have been proposed. For example, GraphGAN [

24] models vertex connectivity through adversarial learning, while NetGAN [

26] generates graphs by learning the distribution of biased random walks with a recurrent neural-network-based generator and a discriminator, optimized using the Wasserstein GAN objective. CONDGEN [

48] further advances this direction by integrating variational methods with adversarial training, enabling conditional graph generation based on semantic contexts and achieving permutation-invariant output. Despite these advances, GAN-based models for graphs still face several limitations such as training instability, convergence difficulties, and mode collapse, motivating ongoing research for more robust and scalable solutions [

49].

Figure 6.

GAN models for graph generation.

Figure 6.

GAN models for graph generation.

Diffusion Models

Diffusion models generate data by defining a forward process that gradually adds Gaussian noise to the input data

over

T steps, producing a sequence of noisy samples

, with the noise at each step controlled by a schedule

(commonly Gaussian). The forward process is defined as:

where

represents the conditional distribution of the noisy data

given the previous state

, and

controls the amount of noise added at each step. As

, the final state

approaches a standard Gaussian distribution. To sample from the data distribution, this process is reversed by learning an approximate reverse transition

, since the true reverse kernel

is generally intractable. A neural network is trained to parameterize the reverse generative process as

where

represents the learned denoising transition used to iteratively reconstruct clean graphs from noise. Training optimizes a variational lower bound (VLB) on the data log-likelihood, expressed as

Three major paradigms of diffusion models have emerged, each addressing probabilistic modeling through distinct methodologies [

13]. Score Matching with Langevin Dynamics (SMLD), represented by DeepRank-GNN [

50], trains a score function to estimate the gradient of the log data density and employs Langevin dynamics for sampling, prioritizing efficiency in high-dimensional spaces. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM), represented by Digress [

51], formalize the reverse process probabilistically, drawing on principles from nonequilibrium thermodynamics to iteratively denoise data. Score-based Generative Models (SGM), represented by GraphGDP [

52] and GDSS [

28], generalize discrete-time diffusion to continuous-time formulations via stochastic differential equations, offering enhanced flexibility for modeling complex temporal and spatial dependencies. Although these diffusion-based models have demonstrated strong sample quality and stable training, they remain computationally intensive due to the large number of reverse diffusion steps required for generation, typically making them slower than GANs and VAEs [

53].

Figure 7.

Diffusion models for graph generation.

Figure 7.

Diffusion models for graph generation.

Deep learning-based generative models employ diverse training objectives as summarized in

Table 1. VAEs approximate data log-likelihood through the ELBO in Equation (

2), representing an approximate maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) approach. Flow Matching and AR models directly maximize exact likelihood via sequential probability decomposition, explicitly modeling graphs in their respective formulations in Equations (

1) and (

3). GANs adopt adversarial training between generator and discriminator networks, following the objective in Equation (

4). Diffusion models optimize either the VLB for reverse diffusion processes in Equation (

5) or employ score matching techniques to estimate gradients of data distributions [

28], with recent advancements enhancing stability and efficiency [

54].

3.2. Simulation Based Probabilistic Modeling

Deep learning-based graph generators rely on high-quality reference data to train robust GGMs. However, obtaining real-world graph data remains challenging due to confidentiality constraints, legal restrictions, and the high cost of data collection. Furthermore, these models often face scalability issues for large-scale graph generation [

10].

To overcome this limitation, simulation-based random graph generators offer a scalable alternative. Random graph models are essential for analyzing complex networks, aiding in understanding, controlling, and predicting various phenomena [

30]. Historically, such approaches can be divided into two categories:

statistical-based simulation and

LLM-based simulation. Early models design predefined statistical rules to generate graphs with target properties. Recent advances in LLM-based agent simulations have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in autonomous decision-making, enabling the dynamic simulation of interaction processes within complex networks [

8,

55]. These models are increasingly recognized as a novel paradigm for text-attributed graph generation.

Statistical-based Simulation

Early graph generators assume real-world networks adhere to predefined structural rules (e.g., degree distributions, clustering patterns) and employ probabilistic sampling to replicate target properties. Three foundational properties have emerged as pivotal in scale-free graph generation: (1) The first key property is the small-world phenomenon. Watts and Strogatz [

56] showed that many real-world networks exhibit high clustering: two nodes are more likely to connect if they share neighbors. They introduced a tunable small world model that rewires a regular lattice to interpolate between order and randomness. (2) The second key property of scale-free graphs emphasized in recent work is shrinking diameter, where network diameter decreases to a constant value over time [

57]. The Forest Fire model [

57] explains this behavior through a modified preferential attachment process known as community-guided attachment. Subsequently, [

58] proposed a social affiliation network model which extended this idea by modeling network evolution via bipartite representations of agents and communities, naturally reproducing heavy-tailed degree distributions, community structure, and shrinking diameter. (3) The third key property of scale-free graphs is their heavy-tailed degree distribution, first highlighted by Albert and Barabási [

7]. The Barabási-Albert (BA) model [

7] formalizes this through preferential attachment, where new nodes connect to existing nodes with probability proportional to their degree (

), resulting in a "rich-get-richer" dynamic that produces power-law degree distributions

(where

). Edge copying models [

59] extend this principle by simulating local growth mechanisms, where new nodes select a prototype node uniformly at random, then probabilistically copy a fraction of its edges. The prototype selection probability remains proportional to degree (

), implicitly enforcing power-law scaling while introducing local clustering.

Later advancements, such as the affiliation network model [

58], unify preferential attachment and edge copying to jointly reproduce power-law degrees and community structure. Moreover, exponential random graph models (ERGMs), also known as

models [

60], constitute a foundational class of statistical frameworks for analyzing and generating social networks. ERGMs define the probability distribution over the space of graphs

with

N nodes by weighting graph statistics

(e.g., edge counts, triangle densities, degree distributions) via parameters

. Each graph

is assigned probability

where

is the normalizing constant ensuring probabilities sum to 1.

Figure 8.

Scalable graph generators based on statistical-based simulation. The left figure shows the graph growth mechanism based on preferential attachment, where edges of new node are added to the graph based on the degree of existing nodes. The right figure shows the graph growth mechanism based on edge coping, where edges of new node are added coping edges of chosen node prototype.

Figure 8.

Scalable graph generators based on statistical-based simulation. The left figure shows the graph growth mechanism based on preferential attachment, where edges of new node are added to the graph based on the degree of existing nodes. The right figure shows the graph growth mechanism based on edge coping, where edges of new node are added coping edges of chosen node prototype.

LLM-based Simulation

With LLMs demonstrating advanced capabilities in human-like responses and autonomous planning [

14], they have emerged as a new paradigm for simulation across diverse domains, including education [

61], social dynamics [

62], and economics [

63]. Particularly, LLM-based multi-agent systems excel in simulating complex interactions, motivating the development of LLM-driven graph generators for dynamic, text-attributed graphs where temporal node and edge formation emerges organically from agent behaviors [

8,

31]. Early efforts in LLM-driven graph generation focused on capturing fundamental properties like degree power-law distributions, small-world phenomenon and community structure [

64,

65], with frameworks such as LLM4GraphGen [

55] formalizing graph synthesis as a textual prompting task. Subsequent works, including IGDA [

66], introduced iterative reasoning mechanisms to model causal relationships in graph evolution, while [

67] explored additional social graph characteristics in political domain. However, these approaches often lack realism due to oversimplified interaction pattern and scalability, typically limited to fewer than 100 agents. Recently, GAG [

68] adopts LLM agents to generate dynamic social graphs attributed to text by large-scale multi-agent simulations, which scales to graphs with 100,000 nodes or 10 million edges. Building on GAG, GraphMaster [

69] extends graph generation beyond social networks, proposing a multi-agent framework with specialized agents that collaboratively optimize graph synthesis process.

4. Model Architecture

Probabilistic modeling defines the underlying generation mathematical formulation, while the model architecture serves as the backbone for learning graph representations and capturing complex dependencies. The latter comprises two components: neural network architectures, which parameterize the model; and modeling strategies, which determine how graphs are represented and generated.

4.1. Neural Network Architecture

Neural network architectures play a crucial role in graph generation models by providing the necessary representational capacity to capture complex dependencies and structures inherent in graph data. Different architectures are suited to various types of probabilistic modeling methods, as summarized in

Table 2. Below, we discuss several prominent neural network architectures commonly employed in graph generation tasks.

Feedforward Neural Networks

Feedforward Neural Networks (FFN), also referred to as multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), represent the most basic form of neural networks. They are particularly effective for input data that can be represented as fixed-size vectors, such as node or edge attributes. Models like NeVAE [

39] and GraphVAE [

27] employ FNNs to learn latent representations of graphs, which are sampled to generate new graphs. Specifically, NeVAE uses an MLP-based probabilistic encoder that aggregates information from a variable number of hops for each node into an embedding vector. Coupled with a decoder, this approach can generate molecular structures by predicting the spatial coordinates of atoms. Furthermore, FNNs are utilized in human motion generation tasks, as in MoGlow [

114] and MotionDiffuse [

127], where they generate motion sequences based on learned representations of temporal human motion graphs.

Graph Neural Network

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are specialized architectures designed to operate on graph-structured data, enabling the modeling of complex relational dependencies among nodes and edges. GNNs leverage message-passing mechanisms to aggregate information from neighboring nodes, allowing them to capture both local and global graph structures. Initial works like GRAN [

23], Graphite [

40], MiCaM [

41] integrated GNNs as decoders within AR, VAE, or flow matching models for molecular graph generation. MolFlow [

44] innovatively replaced traditional affine transformations with graph convolution layers [

37] for node representations, and adopt Glow [

163] for edge generation, enabling topology-aware invertible mappings for molecular graphs. For GAN-based GGMs, GCPN [

123] utilized GCNs to model subgraph topology and scaffold interactions in the generator, with a discriminator validated actions (e.g., node connections, edge types, termination signals) to ensure structural feasibility. GDSS [

28] employs message-passing GNNs as link predictors within a score-based diffusion framework, enhancing generation stability and fidelity by iteratively refining noisy graph structures through learned gradient scores.

Recurrent Neural Network

Recurrent neural network (RNN), due to their ability to process sequential data through hidden state dynamics, are particularly suited for graph generation tasks with sequential representations. GraphRNN [

19] exemplifies this paradigm through a two-tiered architecture: a graph-level RNN maintains the state of the growing graph and generates new nodes, while an edge-level RNN generates the edges for newly generated node. Building upon this foundation, the MolecularRNN [

72] extends GraphRNN for generating graphs with node and edge types. Tigger [

21] adapts the auto-regressive paradigm for dynamic graph generation by decomposing temporal interaction graphs into temporal random walks. Tigger employs RNNs to learn sequential patterns in temporal random walks, with synthetic walk sequences later reconstructed into dynamic graphs through post-processing.

Long Short-Term Memory Network

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, a specialized variant of RNNs, further advance graph generation by addressing long-term dependency challenges inherent in sequential modeling. Like standard RNNs, LSTMs process graphs as stepwise sequences but excel in scalability for large-scale graphs due to their memory-cell design. For edge-sequential representation, GEEL [

74] employs LSTM to model the generation of edges in a graph, which reduces vocabulary complexity via gap encoding and bandwidth constraints. It further extends to attributed graphs through grammar-based adaptations, ensuring scalable and structured generation aligned with edge counts. For node-sequential representation, OLR [

73] employs LSTM to learn node-wise dependencies, introducing a regularization term that enforces invariance of hidden states to node ordering permutations. Moreover, LSTM has been applied to dynamic graph generation tasks, such as TG-GAN [

119], which uses LSTM to help GAN-based GGMs for continuous-time temporal graph generation, by modeling the deep generative process for truncated temporal random walks and their compositions. It models truncated temporal random walks by jointly capturing edge sequences, timestamp, and node attributes through LSTM modules. A complementary discriminator combines recurrent architectures with time-node encodings to distinguish synthetic sequences from real-world temporal patterns.

Other Architectures

Beyond the mainstream architectures discussed earlier, several non-typical frameworks have been proposed to address specialized challenges in graph generation. For statistical-based simulation, classical algorithms such as the Barabási-Albert (BA) model [

7] and Erdős-Rényi (ER) model [

6] define explicit generative rules that produce graphs with characteristic structural properties, including scale-free degree distributions and random connectivity patterns. For deep learning-based generative models, D2G2 [

88] integrates factorized bayesian models of dynamic graphs to generate temporally coherent graph snapshots, enabling the modeling of evolving network structures over time. MolGrow [

115] adopts a flow-based generative model using the RealNVP architecture [

166], which ensures efficient sampling and exact likelihood estimation through invertible transformations. MoGlow [

114] adopts the Glow architecture and extends it to model controllable motion sequences. Grammar-VAE [

100] incorporates probabilistic context-free grammars (PCFGs) to enforce chemical validity in molecular graph generation. By representing discrete graph structures as parse trees derived from context-free grammar rules, it guarantees syntactically valid chemical configurations. PCFG assigns probabilities to each production rule in the grammar, and thus defines a probability distribution over parse trees and, consequently, over valid molecular graphs.

4.2. Modeling Strategy

After learning the probability distributions of observed graphs’ latent representations, GGMs sample synthetic graphs from

. Specifically, the post-processing process includes two dimensions:

generation strategies and

sampling strategies, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

Generation Strategy

Due to the discrete, high dimensional, and unordered nature of graph data representations, GGMs typically employ two main strategies: one-shot generation and sequential generation [

10].

One-shot generation, typically paired with matrix-based representations, generate the entire graph in a single step, offering computational efficiency by avoiding sequential dependencies on node ordering. This approach is particularly widely adopted in VAE, Flow, Diffusion-based models for geometric graph generation. For example, Digress [

51] generate the entire graph structure in one step by predicting the adjacency matrix and node features simultaneously. Similarly, flow-based models like MoFlow [

44] and ChemFlow [

101] generate molecular graphs in a single pass.

While one-shot graph generation offer computational efficiency, they face critical limitations in flexibility compared to sequential representations, particularly in generating large-scale graphs (e.g., social networks). Firstly, output space complexity. Generating a graph with N nodes requires the model to output values to fully define its adjacency matrix. Second, non-unique representations. In general graph generation tasks, a graph with N nodes admits up to equivalent adjacency matrices due to arbitrary node orderings.

Sequential generation has proven particularly effective for scale-free graphs, where iterative node or edge additions align naturally with edge-list or node-list sequential representations [

19,

20,

77]. Pioneering work like GraphRNN [

19] formalized this approach, using recurrent networks to generate nodes and edges sequentially while capturing complex structural dependencies. Extensions such as MTM [

167] further refine temporal dynamics by incorporating motif-list sequential representations to model evolving graph patterns. Recent advancements have also adapted edge-list sequential representations to dynamic graph generation, demonstrating their utility in downstream tasks like link prediction [

76].

Sampling Strategy

In graph generation, sampling plays a crucial role in determining how synthetic graphs are produced. Since generation tasks often require control over specific graph properties or contextual conditions, two primary sampling strategies are commonly employed: random sampling and conditional sampling [

10]. Random sampling involves drawing latent codes from a learned distribution

, producing graphs without explicit control over their structural or properties. In contrast, conditional sampling aims to sample the latent code to generate new graphs with desired properties [

48]. As shown in

Figure 9, such constraints can encompass semantic objectives, structural patterns, graph-level property or node/edge-level attributes.

Semantic conditions involve natural language prompts that guide generating graphs with desired textual description. Early work focused on extracting graph-structured representations from text [

169] or generating graphs based on specified semantic description [

127,

170]. More recently, pre-trained language models have been integrated into conditional generation frameworks; GraphGPT(1) [

77] and LGGM [

143] encode textual prompts and align them with graph embeddings to enforce semantic consistency during generation.

Structural conditions refer to the constraints on the graph structure, such as the number of nodes, edges, or specific connectivity patterns. Random graph models like FastSGG [

151] explicitly enforce degree distribution constraints, while ROLL-Tree [

150] ensures scale-free property of generated graphs. Darwini [

171] further incorporates degree-dependent clustering coefficient distributions, enabling scalable synthesis of graphs that mirror real-world networks while varying size. These approaches are critical for domains requiring strict adherence to domain-specific structural norms.

Property conditions extend structural constraints by incorporating categorical or quantitative attributes of graphs(e.g., hydrophobicity, protein validity). Deep learning models often embed these properties into training objectives via loss functions [

94,

98]. For example, GGDiff [

172] frames conditional diffusion as a stochastic control problem, dynamically adjusting sampling process to generate graphs of target properties.

Edge/Node attributes enforce constraints on discrete or continuous node/edge features (e.g., labels, embeddings). EDGE [

29] generates graphs by first sampling node types and then constructing graphs conditioned on these attributes, while GraphMaker [

130] generalizes this to large attributed graphs by decoupling attribute and structure generation. However, most frameworks struggle with high-dimensional attributes (e.g., text embeddings), often truncating dimensions to fit model limits [

76]. Since real-world graphs often contain high-dimensional attributes [

173], such as node- or edge-level textual features [

173], generating such graphs has attracted increasing attention. LLM-based GGMs [

68,

69] simulate text-driven interactions through agent-based modeling, enabling the organic emergence of complex graph structures.

5. Evaluation

The evaluation of GGMs encompasses three main paradigms: statistic-based metrics, neural-based metrics, and downstream task performance. Statistic-based metrics quantify generation quality by comparing distributions of structural features and domain-specific attributes between generated and real graphs. To overcome their inability to capture high-level semantics, neural-based metrics employ deep models like graph neural networks to extract unified graph representations, enabling comprehensive evaluation of attributed graphs. Finally, downstream evaluation tests practical utility in scenarios including data augmentation, pre-training, and conditional generation, ensuring functional value beyond statistical similarity. These three approaches form a complementary, multi-faceted evaluation framework.

Table 3.

Summary of Statistic-based Metrics for GGMs Across Tasks. Each dataset is cited with its original proposing paper.

Table 3.

Summary of Statistic-based Metrics for GGMs Across Tasks. Each dataset is cited with its original proposing paper.

| Graph Type |

Domain |

Evaluation Metrics |

Datasets |

| Molecule Graph |

Chemistry |

Atom Stability, Molecule Stability,

Validity, Uniqueness, Novelty, Diversity,

FCD

Coverage,

AMR,

PlogP,

Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness,

Synthetic Accessibility,

Dipole Moment, Polarizability,

HOMO Energy, LUMO Energy,

Orbital Energy Gap, Heat Capacity |

QM9 [174]

ZINC [175],

MOSES [176],

ChEMBL [177],

CEPDB [178],

PCBA [179],

GEOM-Drugs [180] |

| Protein Graph |

Biology |

Contact Accuracy, Perplexity,

Fitness |

Enzymes [180,181],

Lobster [182],

Protein [183] |

| Geo-Spatial or Spatial Graph |

Engineering |

RMSE, NRMSE of OD Matrix,

JSD of OD Flow Volumes,

CPC |

LODES [184],

METR-LA [185] |

| Human Motion Graph |

Computer Vision |

MSE, NPSS,

NDMS, PCK,

FID, IS

|

PiGraphs [186],

Human3.6M [187] |

| Social Graph |

Social Science |

Power-law Exponent Gap, Claw Count,

Wedge Count, KOL Distribution |

TwitterNet [188] |

| User-item Bipartite Graph |

Recommendation |

MMR, Hit Rate,

Recall@k

|

MovieLens [189] |

| Synthetic Graph |

N/A |

Degree, Clustering Coefficient,

Spectral Eigenvalues,

Orbit Counts

|

ER [6],

BA [7],

|

5.1. Statistic-Based Metric

For generative models aiming to capture the distribution of real-world graph data, evaluation primarily focuses on comparing statistical property distributions between generated and reference graphs. Common graph statistic-based metrics include the degree distribution (the probability distribution of per-node connection counts), motif counts (subgraphs recurring within or across networks), clustering coefficient (the extent of local node aggregation), orbit counts and etc.

For distributional comparison of statistic-based metrics, researchers often evaluate the graph generation performance by the standard Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) between generated and reference graphs

[

190],

where

is a general kernel function, usually use RBF kernel following [

19]:

where

is pairwise distance, specifically, GraphRNN [

19] employs the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) over the set of graph statistics. In addition to MMD, other works use root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) [

191] or mean absolute error (MAE) [

192] as alternative distance metrics. Since graphs encompass distinct structural or attribute priors, statistic-based metrics are inherently domain-specific. We summarize evaluation metrics and datasets for seven graph types in

Table 3, with dataset details in

Table 4. Detailed descriptions of the metrics and datasets are provided in Appendix.

5.2. Neural-Based Metric

Purely statistic-based metrics have three key limitations [

190]: (1) They produce multiple disjoint scores, complicating model selection. (2) They focus on topology, while under-representing node/edge attributes and missing semantic information. (3) Higher-order statistics (e.g., subgraph counts, spectral distances) are computationally expensive and inefficient. To address these issues, recent work proposes neural-based metrics for evaluating the quality of generative models. [

193,

194] propose untrained neural networks for static graph feature extraction. Building on this, subsequent studies [

190,

195] demonstrate that random graph neural networks can serve as feature extractors for synthetic and real graphs, and then compute a scalar score by applying distances (e.g., MMD, cosine similarity) to the embeddings. Empirical results demonstrate that these neural metrics effectively capture both topology and attribute.

Dynamic graph generation has recently garnered increasing attention [

76]. Early evaluation protocols apply static graph metrics by discretize dynamic graphs into static snapshots. This approach has several drawbacks: (1) it treats temporally dependent events as independent, ignoring temporal evolution; (2) it lacks a unified score sensitive to both attributes and topology; (3) it requires multiple, incomparable metrics; (4) it materializes each snapshot, leading to high runtime and poor scalability. To address these limitations, the JL-metric [

196] is proposed as a dynamic graph evaluation method. It uses dynamic GNNs as temporal encoders to capture the joint evolution of node states and topology, enabling end-to-end assessment without snapshot decomposition. Recently, the Graph Embedding Metric [

197] further improves JL-metric, incorporating textual information from node attributes alongside dynamic GNNs. This method jointly models the evolution of both textual attributes and graph structure, providing a unified evaluation of text-attributed dynamic graph generation.

5.3. Downstream Task

Beyond distributional similarity to reference graphs, a complementary line of work evaluates generated graphs by their utility on downstream tasks. Rather than directly matching structures, these protocols assess the practical usefulness of generated graphs in standard graph learning scenarios. Under this evaluation framework, the generated graphs are primarily assessed across five types of downstream tasks: (1) Machine learning tasks involving graph generation evaluate whether synthetic graphs can substitute reference graphs in training discriminative models, with performance ratios near 1 indicating comparability in topology and attributes [

130]. (2) Data augmentation tasks address data sparsity, particularly for long-tail categories [

198]. (3) Robust graph generation tasks enhance graph resilience against noise, such as in relation extraction, with frameworks like LLM-CG [

199] improving robustness and detecting anomalous structures. (4) Generative pretraining tasks leverage self-supervised graph generation to boost downstream performance, including link prediction, node classification and etc [

91,

143]. (5) Conditional graph generation focuses on synthesizing graphs that meet specific conditions, crucial in applications like drug discovery, with methods such as ChemFlow [

101] and Next-Mol [

145] generating molecular structures based on target properties or protein interactions for drug design.

6. Application

Building upon

Section 3, we categorize and discuss real-world applications of GGMs in alignment with their probabilistic modeling methods. Deep learning-based GGMs automatically learn complex graph data distributions, excelling in high-fidelity applications like molecule design, protein engineering, and transportation network modeling. In contrast, simulation-based GGMs capture graph evolution through predefined rules or agent behaviors, making them ideal for social network analysis and recommender systems, where interpretability and dynamic modeling are key. These paradigms complement each other, advancing graph generation in scientific and social science research applications.

6.1. Deep-Learning Based Graph Generator

Deep learning-based probabilistic modeling for graph-structured data have emerged as a transformative force across diverse domains, especially in geometric graph generation. This section explores six key applications of graph generation: (1) molecule generation, (2) protein design, (3) transportation network modeling, (4) human motion prediction, (5) dynamic graph modeling, and (6) general graph modeling. These advancements underscore the critical role of GGMs in addressing high-dimensional combinatorial challenges under domain-specific constraints.

Molecule Generation

In molecular graph generation, molecules are graphs: atoms as nodes, bonds as edges [

200]. The goal is chemically valid structures with desirable properties, spanning 2D and 3D molecule generation. 2D molecule generation focuses on constructing a standard molecular graph. Most existing methods fall into several categories based on their generative paradigms. Auto-regressive models, such as GraphAF [

82], MolecularRNN [

72], and Lingo3DMol [

84], generate atoms and bonds sequentially, capturing the step-by-step formation of molecules. VAE-based methods, such as JT-VAE [

93], learn a latent space to encode and decode molecular graphs while enforcing chemical validity. Diffusion-based approaches, like Digress [

51], model the generation process as a denoising trajectory from noise to structured molecules. Flow-based models, such as GraphCNF [

104], GraphNVP [

95], and GGFlow [

46], use invertible transformations to map between molecular graphs and latent distributions, enabling efficient and tractable generation. While 3D molecule generation can be regarded as the construction of a special type of graph, where each node represents an atom characterized by atom type and 3D coordinates. Edges are bonding relationships and inferred based on pairwise distances between atoms. Most models use diffusion- or flow-based generative methods. For example, EDM [

131] was the first to apply diffusion models for 3D molecule generation, followed by models such as GeoLDM [

128] and CDGS [

133], which build upon this paradigm. Alternatively, methods like ENF [

102], EquiFM [

103], GeoBFN [

105], and GOAT [

109] utilize flow-based models to generate 3D molecular graphs. Recently, Uni-3DAR [

85] introduced an auto-regressive framework for 3D molecule generation and also achieved competitive results.

Protein Design

Protein generation tasks have also become an essential branch of graph generation research. The 3D structures of proteins are formed by the folding of amino acid sequences and can be naturally represented as graphs, where each node typically corresponds to an amino acid, and edges are defined between residues that are either spatially close in 3D space or sequentially adjacent [

201]. AlphaFold 3 [

202] introduced a diffusion-based generative framework capable of predicting full-atom coordinates of biomolecular complexes. Due to limitations in computational scale and complexity, more studies have primarily focused on generating partial protein structures or lower-level structural representations. For example, in antibody design tasks, current methods [

203] aim to generate only the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), which are then combined with external structure prediction models to obtain complete antibody structures. Other works, such as [

203,

204], focus on generating peptides, which are smaller in scale and structurally simpler. At even lower levels of structural representation, recent methods [

205,

206] generate 2D contact maps, which are subsequently decoded into 3D conformations. In addition, works like [

207,

208] utilize tertiary or secondary structural information as guidance for protein sequence generation.

Table 4.

Summary of commonly used datasets in deep-learning-based, statistical simulation-based and LLM simulation-based graph generation models (GGMs). Columns: #Graphs (number of graphs), #Nodes (average node count per graph; ranges [a, b], alternates (b) denoting commonly observed preprocessed sizes, or for bipartite graphs a/b for user/item counts respectively), #Edges (average; N/S = not specific), whether nodes/edges have attributes ( = text-attributed), source, and representative models. Numerical values are normalized to thousands (k) or millions (M).

Table 4.

Summary of commonly used datasets in deep-learning-based, statistical simulation-based and LLM simulation-based graph generation models (GGMs). Columns: #Graphs (number of graphs), #Nodes (average node count per graph; ranges [a, b], alternates (b) denoting commonly observed preprocessed sizes, or for bipartite graphs a/b for user/item counts respectively), #Edges (average; N/S = not specific), whether nodes/edges have attributes ( = text-attributed), source, and representative models. Numerical values are normalized to thousands (k) or millions (M).

| Graph Type |

Probabilistic Modeling |

Name |

# Graphs |

# Nodes |

#Edge |

Node Attr. |

Edge Attr. |

Source |

Model Used |

| Geometric |

| molecular |

deep-learning based |

QM9 |

133.9K |

18 |

19 |

✓ |

✓ |

[174] |

[27,29,82,87,110,116,143,209,210,211] |

| molecular |

deep-learning based |

ZINC250k |

250K |

23 |

25 |

✓ |

✓ |

[175] |

[25,72,94,96,110,111,143,209,211,212,213] |

| protein |

deep-learning based |

Lobster |

100 |

53 |

52 |

|

|

[182] |

[20,25,28,51,74,214] |

| protein |

deep-learning based |

Enzymes |

600 (587) |

15 |

149 |

|

|

[180,181] |

[23,25,51,74,143,214] |

| protein |

deep-learning based |

Protein |

1.1K (918) |

1.6k |

646 |

|

|

[183] |

[20,25,28,51,74,143,214,215] |

| geo-spatial |

deep-learning based |

California |

1 |

7.9k |

2.6M |

|

✓ |

[216] |

[83] |

| geo-spatial |

deep-learning based |

Massachusetts |

1 |

2.4k |

58.2k |

|

✓ |

[216] |

[83] |

| geo-spatial |

deep-learning based |

Texas |

1 |

7.9k |

756.2k |

|

✓ |

[216] |

[83] |

| synthetic, spatial |

deep-learning based |

Planar |

200 |

64 |

N/S |

|

|

[217] |

[28,74,214] |

| synthetic, spatial |

deep-learning based |

Grid |

100 |

[100, 400] |

N/S |

|

|

[19] |

[20,51,215] |

| synthetic, spatial |

deep-learning based |

DRG Graph |

1 |

N/S |

N/S |

|

|

[218] |

[219] |

| synthetic, spatial |

deep-learning based |

DWR Graph |

1 |

N/S |

N/S |

|

|

[218] |

[219] |

| Scale-free |

| synthetic, social |

deep-learning based |

SBM |

200 |

[20, 40] |

N/S |

|

|

[217] |

[20,25,28,74,214,215] |

| synthetic, social |

deep-learning based |

Ego |

500 |

[60, 160] |

N/S |

|

|

[19] |

[19,29,40,82,215,220,221,222,223] |

| synthetic, social |

deep-learning based |

Community |

757 |

[50, 399] |

N/S |

|

|

[19] |

[19,29,82,215,220,221] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

Polblogs |

1 |

1.2K |

16.7K |

|

|

[224] |

[29,215,225] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

DBLP |

1 |

17.8K |

51.1K |

|

|

[226] |

[124,126,143,227] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

WIKI |

1 |

9.2K |

157.4K |

|

|

[228] |

[21,76,124] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

Facebook |

1 |

1.0K |

53.5K |

|

|

[229] |

[168] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

Citeseer |

1 |

3.3K |

4.7K |

✓ |

|

[230] |

[25,40,91,129,168,215] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

Cora |

1 |

2.7K |

5.4K |

✓ |

|

[231] |

[25,26,29,40,91,129,168,215,232] |

| |

statistical-based simulation |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

[153] |

| social |

deep-learning based |

Enron Emails |

1 |

785 |

5.8K |

|

|

[233,234] |

[235] |

| |

statistical-based simulation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[22,236] |

| social |

statistical-based simulation |

ego-Twitter |

1 |

81,306 |

1.8M |

✓ |

|

[229] |

[151] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

WARRIORS |

1 |

100.0K |

285.0K |

|

|

[158] |

[158] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

IMDb-text |

1 |

125.7K |

1.5M |

|

|

[197] |

[197] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

Cora-text |

1 |

48.8K |

110.8K |

|

|

[231] |

[68,197] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

WeiboTech |

1 |

20.7K |

109.3K |

|

|

[197] |

[197,237] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

WeiboDaily |

1 |

66.5K |

354.1K |

|

|

[197] |

[197,237] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

Metoo |

1 |

1.0K |

31.9K |

|

|

[238] |

[239,240] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

Roe |

1 |

1.0K |

121.5K |

|

|

[241] |

[239,240] |

| social |

LLM-based simulation |

Twitter |

1 |

1.0M |

30.2M |

|

|

[242] |

[242] |

| user-item bipartite |

LLM-based simulation |

Movielens-1M |

1 |

6.0K/3.9K |

1.0M |

✓ |

✓ |

[189] |

[154,243] |

| user-item bipartite |

LLM-based simulation |

Amazon review |

1 |

54.4M/48.2M |

571.5M |

✓ |

|

[244] |

[155,243,245] |

| user-item bipartite |

LLM-based simulation |

Steam |

1 |

2.6M/15.4K |

7.8M |

✓ |

|

[246] |

[243,247] |

| user-item bipartite |

LLM-based simulation |

Lastfm |

1 |

1.9K/17.6K |

92.8K |

|

|

[248] |

[249,250,251] |

Transportation Network Modeling

Spatial graphs, or specifically geo-spatial graphs, model dynamic interactions in transportation systems, captured through an OD matrix that quantifies trip volumes and encodes connectivity [

252,

253]. GGMs jointly capture the temporal and spatial distributions of spatial graphs, enabling their application to multivariate time series forecasting in transportation networks. For example, STGEN [

125] learns the multi-modal distribution of spatial graphs by modeling the distribution of spatio-temporal walks using a novel heterogeneous probabilistic sequential model. This allows it to generate GPS coordinates for spatial graphs that align with real-world geographic maps.

Human Motion Prediction

In human motion graph generation, models need to reconstruct occluded or incomplete skeletal markers in historical data. MGCU [

254] extracts hierarchical spatial-temporal features using a multi-scale graph computational unit that models interactions across joint hierarchies. CSGN [

255] employs a graph-based framework to holistically generate entire motion sequences rather than auto-regressive sequential prediction, transforming latent vectors sampled from a Gaussian process into skeletal trajectories. MoGlow [

114] and MotionDiffuse [

127] leverage auto-regressive normalizing flows with FFN-based architectures to model motion sequences. Building upon MoGlow [

114], ST-GCN-2 [

256] integrates spatial graph convolutional networks to explicitly encode human skeletal topology within normalizing flows, uses a spatial graph convolutional network to extract features from past motion sequences.

Dynamic Graph Modeling

Most existing methods focus on static graphs, while many real-world graphs are dynamic, with nodes, edges, and attributes evolving over time. Recent advancements in dynamic graph learning have primarily targeted discrete-time dynamic graphs (DTDGs) and continuous-time dynamic graphs (CTDGs), with significant progress made through dynamic graph neural networks (DGNNs) [

257,

258]. These models excel in discriminative tasks such as future link prediction and node classification. In contrast, generative dynamic graph learning, which aims to synthesize realistic dynamic graph structures, remains in its nascent stage. Early works primarily focus on DTDGs, generating graph snapshots through spatiotemporal embedding learning akin to static graph generation [

23,

26]. Recent advances have shifted toward CTDGs, enabling fine-grained temporal modeling that better aligns with real-world application requirements [

21,

124]. Recent work is beginning to explore attribute-aware generation. VRDAG [

42] implements node feature generation through graph-based VAEs, while DG-Gen [

76] models edge attributes via joint conditional probability distributions. However, the field currently lacks standardized benchmarks, as most works directly adopt datasets designed for discriminative tasks [

21,

124].

General Graph Modeling

Recent years have witnessed unprecedented success achieved by Large Generative Models (LGMs) [

259]. The key to their success lies in their usage of the world knowledge inherited from the pre-training stage. Compared with the recent LGMs in NLP and computer vision, exploration into LGMs for graphs remains limited. Notably, LLGM [

143] proposes a large-scale training paradigm that uses a large corpus of graphs (over 5000 graphs) from 13 domains, offers superior zero-shot generative capability to existing graph generative models. Similarly, G2PT [

260] processes an auto-regressive transformer architecture that learns graph structures through edge-list based sequential representation on graphs in different graph domains.

6.2. Simulation-Based Graph Generator

In contrast to deep learning-based GGMs, simulation-based GGMs prioritize capturing the dynamic evolution of scale-free graphs, such as social graphs and user-item bipartite graphs. This section explores three prominent real-world applications of scalable GGMs, including social network analysis and recommender systems.

Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis (SNA) is foundational in computational social science, with simulation-based graph models emerging as powerful tools for real-world network dynamics. We highlight three key SNA applications: (1) Network pattern understanding. Statistical probabilistic modeling enables the discovery of emergent topological patterns, offering insights into their formation mechanisms. The Barabási-Albert (BA) model [

7] employs preferential attachment to generate scale-free networks. Similarly, edge-copying models [

59] simulate processes like gene duplication in biological networks, reflecting structural conservation through node neighborhood replication. (2) Network evolution modeling. Graph evolution simulations are instrumental in studying dynamic processes. Recent advances integrate LLM-based agents to simulate human-like behaviors for large-scale social network evolution, particularly in online social environments. Studies leverage either real data [

159,

239], or synthetic user profiles [

68] to initialize networks. Hybrid approaches, such as OASIS [

160], combine limited real-world relationships with synthetic data, while others employ homophily-driven assumptions to connect similar users [

162]. (3) Influence maximization. Identifying key opinion leaders (KOLs) within social networks is essential for effective information dissemination and marketing strategies. Simulation-based graph generators can model the influence diffusion process through networks, enabling researchers to pinpoint nodes with the greatest potential for widespread information propagation. Early graph generation studies often relied on IC/LT models to simulate influence propagation and identify key nodes [

261]. More recent work has shifted toward using LLM-based agents to simulate user behaviors and interactions within social networks. These models simulate influence propagation to study information diffusion and dynamic attitude shifts in response to events, such as opinion leadership dynamics [

9] and rumor spread [

157]. (4) Policy analysis. Simulation-based graph generators provide a controlled environment to evaluate the impact of various policies on social networks. In economic domains, frameworks like SRAP-Agent [

156] simulate decision-making under resource allocation policies, enabling policy evaluation through synthetic network interactions.

Recommender System

In recommender systems, predicting user-item interactions fits a bipartite graph: users and items as separate node sets, edges for ratings, purchases, or clicks [

262]. LLM-driven simulations build controllable user-item interaction environments, enabling analysis of recommender challenges that resist traditional approaches. (1) Addressing sparsity and cold-start challenges. Traditional collaborative filtering methods struggle with sparse data, especially for new users or items. Simulation-based approaches alleviate this by generating realistic interactions for cold-start scenarios. For example, the Lusifer environment [

263] uses LLM agents to update user states dynamically and generate feedback for new items, directly targeting the cold-start problem. Similarly, LLM-powered user simulators [

165] address sparse training data by combining logical preference reasoning with data-driven statistics to simulate reliable behaviors for underrepresented users and items. (2) Modeling preference evolution. Static bipartite graphs cannot model evolving user preferences and item popularity. Simulation frameworks address this by embedding temporal patterns into graph generation. SUBER [

264] employs LLM-based agents to simulate user behavior trajectories, generating dynamic bipartite graphs that capture preference changes over time. In contrast to modeling individual users, RecAgent [

154] incorporates social interactions where users influence others’ preferences. RecUserSim [

265] extends this approach by incorporating memory and behavioral modules in conversational settings to model evolution across dialogue interactions. Agent4Rec [

243] shows how generative agents with personalized profiles and memory can simulate diverse long-term user behaviors.

7. Future Opportunity

We explore several promising future opportunities, including improving scalability of deep learning models, enhancing controllability with target properties, advancing multimodal graph generation using diverse data sources, and establishing more robust and generalizable evaluation metrics.

Scalability

Deep learning-based GGMs capture complex high-order dependencies but suffer from super-linear time complexity, limiting them to small graphs. Only a handful of approaches achieve linear time complexity (O(M)) [

20,

29]. Simulation-based models scale linearly to millions of nodes but rely on oversimplified assumptions, causing unrealistic topologies. As illustrated in

Figure 1, simulation-based models dominate large-scale graph generation due to their efficiency, while deep learning-based excel in capturing complex, real-world graph statistics.Bridging this gap requires hybrid frameworks that combine scalability and expressiveness.

Controllability

Existing GGMs provide limited control beyond basic graph-level statistics. While domains such as molecule and protein design require constraint satisfaction [

266,

267,

268,

269], and social networks demand behavior-aligned structures [

9,

55]. Control interfaces that encode prior knowledge are crucial. Moreover, current methods still lack semantic and functional control of node and edge attributes.

Multimodality

Real-world graphs include rich multimodal information (e.g., text, attributes, temporal signals). As illustrated in

Figure 1, recent research has progressively advanced the attribute modalities of generated graphs, evolving from non-attributed structures to categorical/numeric attributes, and ultimately to textual or multimodal representations [

68,

270]. Challenges persist in effectively capturing attributed graphs, such as textual descriptions, OD flows, and molecule types, which are crucial for generating results that are both structurally sound and semantically meaningful [

1].

Evaluation

Like generative models for image and language, graph generation lacks unique ground truth, making evaluation inherently difficult. Neural-based metrics capture structure but do not scale; statistic-based metrics miss important properties [

190]. Many domains also require costly or domain-specific validation [

271]. More robust, efficient, and standardized evaluation protocols are needed.

8. Conclusion

This survey provides a systematic overview of graph generative models (GGMs). First, we propose a novel taxonomy that categorizes GGMs by target graph categories (geometric vs. scale-free), generated attribute modality (non-attribute, categorical/numeric, or textual), and probabilistic modeling methods (deep learning-based vs. simulation-based). For geometric graphs, we analyze how deep learning-based GGMs leverage advanced architectures to capture structural dependencies; For scale-free graphs, we show how simulation-based approaches effectively model network growth mechanisms. Additionally, we examine model architectures and evaluation metrics across different graph categories, analyzing their strengths and limitations in various application scenarios. Finally, we identify four key research directions: improving scalability, enhancing controllability, advancing multimodal graph generation, and developing robust evaluation metrics. This survey aims to provide a foundational reference for researchers in graph generation by consolidating recent advances and offering structured insights into this rapidly evolving field.

References

- Guo, X.; Zhao, L. A Systematic Survey on Deep Generative Models for Graph Generation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 5370–5390. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cen, J.; Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Kong, X.; Jiao, R.; Yu, Z.; Xu, T.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; et al. A survey of geometric graph neural networks: Data structures, models and applications. CoRR arXiv:2403.00485 2024.

- Bonifati, A.; Holubová, I.; Prat-Pérez, A.; Sakr, S. Graph Generators: State of the Art and Open Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv., CSUR 2021, 53, 36:1–36:30. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wu, S.; Xu, G.; Li, Q. Dynamic graph evolution learning for recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proc. Int. ACM SIGIR Conf. Res. Dev. Inf. Retr., SIGIR, 2023, pp. 1589–1598.

- Sakr, S.; Pardede, E., Eds. Graph Data Management: Techniques and Applications; IGI Global, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Erdos, P.; Rényi, A.; et al. On the evolution of random graphs. Publ. math. inst. hung. acad. sci 1960, 5, 17–60.

- Barabási, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 1999, 286, 509–512.

- Mou, X.; Ding, X.; He, Q.; Wang, L.; Liang, J.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Lin, J.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.; et al. From Individual to Society: A Survey on Social Simulation Driven by Large Language Model-based Agents. CoRR arXiv:2412.03563 2024, [2412.03563]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Yan, R. A Large-scale Time-aware Agents Simulation for Influencer Selection in Digital Advertising Campaigns. CoRR arXiv:2411.01143 2024, [2411.01143]. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S. A Survey on Deep Graph Generation: Methods and Applications. In Proceedings of the Learning on Graphs Conf., LoG, 2022, Vol. 198, p. 47.

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, P.; Zhu, W. Deep Learning on Graphs: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 249–270. [CrossRef]

- Faez, F.; Ommi, Y.; Baghshah, M.S.; Rabiee, H.R. Deep Graph Generators: A Survey. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 106675–106702. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Tang, J.; Li, Q. Generative Diffusion Models on Graphs: Methods and Applications. In Proceedings of the Proc. Int. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell., IJCAI, 2023, pp. 6702–6711. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Lan, X.; Li, N.; Yuan, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, F.; Li, Y. Large language models empowered agent-based modeling and simulation: A survey and perspectives. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1–24.

- Hao, G.; Wu, J.; Pan, Q.; Morello, R. Quantifying the uncertainty of LLM hallucination spreading in complex adaptive social networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16375.

- Pach, J. Geometric graph theory. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series 1999, pp. 167–200.

- Broido, A.D.; Clauset, A. Scale-free networks are rare. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1017.