Introduction

In the 1980s and 1990s, as a result of the international economic situation and the questioning of post- Fordism, the Western regions most severely affected by waves of deindustrialisation were prompted to recon- sider the role of ‘human capital’, culture, and social networks based on the value of individuals (fablabs and third places, such as knowledge exchange, barter, or knowledge-sharing systems) as drivers of social cohesion capable of revitalising these territories (Florida, 1995; Woolcock, 1998). This change in perception, transfor- ming former industrial wastelands into places with new potential, has led to a slow shift in public policies supporting cinema, as part of the emergence of a new domain of public action, the so-called ‘cultural and creative’ sectors, and their corollary: the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) (namely cinema, audiovisual, video games, publishing, the digital economy, etc.), a term originally derived from the Marxist critique of cultural industries and now backed by the management theories of the 1990s, which made ‘creativity’ and

‘participation’ the managerial and organisational imperatives of a world in which everyone can dream of being an artist-worker (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999; Menger, 2003). Some observers explain this shift by the transition from traditional cultural industries to so-called ‘content’ industries linked to ICT, media conver- gence, and the emerging platform economy (Mi`ege, 2000), generating an explosion in the demand for skilled artistic labour and ‘content creators’. In this situation, where culture is tasked with the economic and social renewal of regions, the issue of technical equipment – and particularly film studios – is gradually emerging as a matter of major public interest in the Western countries that suffered most from the deindustrialisation of the 1980s and 1990s. In France, however, this new direction, and the new hopes it brings, barely conceals a long period of disinvestment (Duval, 2016; Daumas, 2007). In the 1980s, the major French film studios – such as those in Boulogne-Billancourt, Joinville, and E´pinay – entered a multifactorial crisis. Competing with the studios of the former ORTF dedicated to television production, traditional studios also suffered a form of latent desertion resulting from the new aesthetics of auteur cinema, which, in the wake of the New Wave, favoured shooting on location, which was less expensive and perceived as more authentic (Lecler, 2010). Therefore, during these decades, the CNC’s intervention policy remained firmly focused on supporting works – with advances on receipts as the flagship measure – and audiovisual production companies – via the automatic support account and COSIP (Gimello-Mesplomb, 2025). The studio was then perceived as a service provider, one expense among many in the cost of making a film, far from the industrial facility whose expansion and modernisation should be supported by public aid. In fact, strictly speaking, there is no public policy in France dedicated to film production facilities, as the sites are almost entirely owned by private operators, with a few notable exceptions where local authorities are the owners (the Victorine Studios are owned by the city of Nice, La Montjoie is managed by a semi-public company, and the Pˆole Pixel in Lyon is partly operated by Rhˆone-Alpes Cin´ema).

What is more, at the turn of the 2000s, the digitisation and dematerialisation of image production and distribution methods disrupted established arrangements (Chantepie & Le Diberder, 2005), altering the very definition of the studio. The contemporary studio is no longer limited to being a simple film set; rather, it resembles a service hub that combines sets, production workshops, post-production and animation facilities, backlots, equipment suppliers, training organisations, and sometimes accommodation for crews. This organisation responds to the unprecedented intensification of audiovisual production on a global scale, fuelled by the growth of SVoD platforms and the popularity of series.

However, the few existing public instruments for supporting studios, although vital for the sustainability of certain sites, have proved fragmented and ineffective in the face of international competition. They have led to competition between territories, without an overarching vision, and have proved insufficient to cover the heaviest investments (construction of new large-scale sets, purchase of expensive technological equipment, development or extension of backlots). It is this legacy – ageing studio facilities, the lack of a coherent national policy for technical industries, and the fragmentation of local aid – that forms the backdrop to the diagnosis made in 2019 by Serge Siritzky in his report Les studios de tournage, un enjeu primordial pour la production en France (Film studios, a key issue for the competitiveness of film production in France). It is this same observation that makes the French government’s massive and direct intervention via the France 2030 ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ call for projects in 2022 both necessary and unprecedented in the recent history of French film policy.

1. From the Siritzky Report (2019) to the Publication of the ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ Call for Projects (2022)

In May 2019, in a report submitted to the CNC and Film France, ‘Film studios, a key issue for production in France’, Serge Siritzky, a leading figure in cinema exhibition (his father owned a network of cinemas that was seized by Vichy and sold to Continental, the future UGC), made a stark observation: French studios are lagging far behind in terms of space (with only 58,000 m², the country remains far behind competitors such as the United Kingdom, which has 360,000 m², Hungary and Germany), equipment (limited backlots, sets that are too small) and economic structure (dependence on rentals, high labour costs), which undermines their attractiveness in the face of competition from their main European neighbours. The report recommends strong public mobilisation to modernise French facilities and turn them into an ‘international hub’ for film shoots. Siritzky summarises the role that public authorities must play in supporting the structuring and governance of the sector. The report’s findings are echoed within the state apparatus, in a rather favourable economic climate where demand for content is exploding due to the rise of video-on-demand (SVoD) platforms and where international competition to host film shoots is intensifying. The diagnosis of France’s structural under-equipment thus became a shared concern, which the Covid-19 crisis a few months later would illustrate (increased use of platforms by content creators, a surge in online sales of cultural products, and consumption of French-language series). Rather than giving rise to an immediate and isolated sectoral response, this concern was incorporated into a broader government reflection on economic sovereignty and the reindustrialisation of the country in the field of audiovisual content production. Thus, two years after these observations, the government’s response took the form of a call for projects entitled ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ (GFI), an initiative directly stemming from the ‘France 2030’ investment programme for the future (PIA). Announced in October 2021, this comprehensive plan mobilises EU54 billion to modernise key sectors such as energy, aeronautics, and the automotive industry, through new methods and industrialisation, with the aim of making France a leader in these fields. Coordinated by the General Secretariat for Investment (SGPI) under the authority of the Prime Minister, this programme provides the financial support and political guidance that had previously been lacking for large-scale intervention in favour of the technical industries of cinema and audiovisual production. The credit line dedicated to studios, animation, and training (as well as reducing the carbon footprint of film shoots) aims to meet the sharp increase in demand for works in the cinema, audiovisual, and video games markets; it has been allocated EU350 million between now and 2030. The primary objective is to trigger an industrial leap forward by doubling the surface area of film sets to 153,000 m2 and quadrupling that of backlots (permanent outdoor sets) to 187,000 m2, in order to position France at the forefront of continental Europe. This material growth is accompanied by an unprecedented acceleration in training for careers in audiovisual creation, in order to provide the human capital required by these new facilities. This entire boom is organised according to a logic of territorial consolidation around regional centres of excellence in the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) and a PEPR (Priority Research Programme and Equipment) with a budget of EU25 million over a period of six years, managed by the CNRS acting as operator: the PEPR ICCARE – Cultural and Creative Industries. Finally, this programme is guided by two cross-cutting objectives: a requirement for ecological responsibility to reduce the sector’s carbon footprint, and the search for direct socio-economic benefits for the regions in terms of job creation, economic activity, and tourist appeal. The specifications of the GFI call for proposals reflect the recommendations of the 2019 Siritzky report: to encourage the creation of service hubs combining large studios, training, and technical and digital skills. The stated objective is to ‘double production and training capacities’—a very large ‘x2’ is mischievously featured on the CNC’s communication materials—double the surface area of the sets, and quadruple the backlots to meet European standards. This plan also aims to support training organisations associated with professions in high demand in these sectors, in order to position France as ‘the European leader in film shooting and digital production’. At the close of the call for projects, 175 applications were submitted for 68 projects selected in 12 regions. The underlying objectives of this reindustrialisation policy are twofold. On the one hand, it aims to satisfy a demand for cultural sovereignty in the face of the influence of SVoD platforms on domestic image consumption and its corollary, the serialisation of production; and, on the other hand, it aims to restore a fleet of studios that are costly to maintain. In short, the studio policy pursued by La Grande Fabrique de l’Image can be seen as a response to two pressures: growing demand for audiovisual content and international competition.

2. 2000-2010: Global Competition to Attract Film Shoots, but Efforts in France Focused Mainly on Tax Credits

If France is striving, through this appeal, to make up for an obvious structural deficit, it is because compe- tition has been raging since the early 2000s, and especially since 2010, between the major Western countries to attract film shoots and, with them, the hoped-for windfall of their direct and indirect financial bene- fits. Two studies commissioned by the CNC from private consulting firms in September 2011 and October 2014 had already highlighted this trend (Hamac Conseils & Mazars, 2014). In the same vein, a report at the time by Ernst & Young for the CNC, entitled d’impot (Evaluation of tax credit schemes: the case of the French film industry), concluded that ”for the reasons already mentioned, France does not appear to be competitive compared to countries with financial tools to reduce the bill or countries practising social dumping ” (Ernst & Young & CNC, 2014), particularly Belgium and its Tax Shelter (a tax loophole in the Belgian Income Tax Code (Article 194ter) designed to encourage investment in cultural works by companies subject to corporation tax). In 2018, MP Joel Giraud, author of a parliamentary report on the issue, made the same observation, stating that ”today, there are no fewer than thirteen foreign schemes that can be considered more attractive than French tax credits”, once again identifying the Belgian Tax Shelter as the main competitor (National Assembly, 2018). However, these reports make little or no mention of the term ”studio” and do not specifically address France’s capacity to host film shoots. The government’s efforts remain focused on tax incentives to attract productions, but without addressing the infrastructure itself — sets, studios, backlots — (CNC/EY, 2014). This omission is all the more surprising given that this infras- tructure is essential to the logistical and territorial competitiveness of productions. At the time, the CNC responded to France’s need to move upmarket in terms of hosting film shoots, with a mainly quantitative approach based on the effects of a tax credit presented as the main economic lever, but without considering the practical aspects of the issue: capacity, occupancy rates, surface area, competitiveness of infrastructure compared to countries with large studios, etc. This situation can be explained in large part by the way the CNC is organised. The institutional architecture of the Centre national du cinema et de l’image animee (CNC), established in 1946, is still based today on a traditional segmentation of its activities by ”sectors”, a perfectly understandable choice given the context of cultural and industrial reconstruction that France was experiencing in 1946, in the midst of the Marshall Plan, but which today may raise questions about its relevance: cinema, audiovisual, video (physical and dematerialised) and video games are thus supported separately. This siloed organisation, although rational in view of the technical monopolies and historical dis- tribution channels specific to each medium, nevertheless reveals its limitations in the face of the challenges of digital convergence (multi-screens) and the rise of the main SVoD platforms operating in France (Netflix, Disney+ and Prime Video in particular) in financing an audiovisual ecosystem where the boundaries be- tween cinema, TV series, video games and even traditional publishing (”augmented” books based on films, etc.) are becoming increasingly blurred. Nevertheless, this sectoral approach has been perpetuated by the State’s main financial intervention tools. Tax credits, which in the 2000s and 2010s were the main pillar of support for film shoots, are themselves calibrated for separate sectors: The Cinema Tax Credit (CIC) for French-initiated works; the Audiovisual Tax Credit (CIA) for fiction, documentaries or animation intended for television; the Video Game Tax Credit (CIJV); and finally the International Tax Credit (C2I) to attract foreign film shoots. Thus, by targeting its aid towards specific ”finished products” (Creton, 2024) in order to comply with European regulations on state aid, particularly in terms of the territorialisation of expenditure (all tax credits must be granted to works and not to industries or companies, otherwise they would be capped at de minimis levels), the CNC’s support system ( ) has, unintentionally, favoured a logic of the work over a logic of industrial tools for decades. The implicit objective of public support has remained fixed on the production of cultural objects with high symbolic value, intended to shine at major international festivals or compete for prestigious awards (Gimello-Mesplomb, 2015, 2025). In doing so, the system values content, the artistic ’software’, and relegates the productive apparatus, the industrial ’hardware’, to a peripheral role. The creation of the Commission superieure technique de l’image et du son (CST) in 1944, two years before the CNC, is particularly symptomatic of this hierarchy of values. By outsourcing technical expertise to a separate entity, operating under association status, and confining it to an advisory and standardisation role, the public authorities institutionalised a dissociation between creation (the content) and technology (the form). Today, the CST certainly plays a role in promoting technical quality and innovation, but it is not integrated into the core of the film industry’s strategy. It advises, but it does not co-decide on infrastructure investment policy.

3. Breaking Down ‘Organisational Silos’ in Cinema and the Creative Industries. An Old Pipe Dream

However, the traditional distinction between cinema, television, advertising, and video games is becoming increasingly blurred in modern production facilities: the same film set or visual effects studio can now be used interchangeably by these different sectors. This functional versatility renders the idea of studios and post- production companies as simple providers of compartmentalised services an anachronism. This perception is all the more outdated given that video-on-demand platforms are investing heavily in unified production facilities, as evidenced by the long-term agreement signed by Netflix with Shepperton Studios in the United Kingdom in 2019 (Netflix, 2019). Thinking of studios as key infrastructure for the national audiovisual industry therefore requires moving away from a logic of separating activities.

The idea of bringing together actors in a sector within a given territory is not new in French industrial policy. Twenty years before the GFI, an initial call for projects aimed at creating ‘competitiveness clusters’ was launched in December 2004, the results of which, in the audiovisual field, were examined in the thesis of geographer Bruno Lusso. Lusso analysed (Lusso, 2011, 2013, 2014) how the networking of diverse actors in the sector (professionals, institutions, schools, digital companies) contributed, in the early 2000s, to the emergence of ‘transmedia clusters’ and ‘clusters’ in cities such as Lille, Lyon, and Marseille. Lusso defines these groups as ‘professional associations seeking to break down the silos between audiovisual, video games and digital’, acting as ‘intermediaries’ to stimulate cooperation and innovation (Lusso, 2013). According to the definition given at the time by DATAR, then operating on behalf of the government for this first call for proposals (four other waves of calls would follow between 2004 and 2026), ‘a competitiveness cluster brings together companies, research laboratories and training establishments in the same territory’. This philosophy is similar to that promoted by the Grande Fabrique de l’Image (Great Image Factory) – with the exception of research laboratories (which are the subject of France 2030 PEPR, this time targeting ‘programmes’ rather than ‘structures’, i.e., laboratories). These partners are invited (and given tax incentives) to work together horizontally ‘in order to develop synergies and increase their competitiveness in a particular sector’, with the close involvement of local authorities. The stated objective of the competitiveness clusters was to increase competitiveness, encourage job creation, and support vulnerable regions, while combating relocation. This system is directly inspired by the concept of ‘industrial clusters’ analysed by Michael Porter (1990), with its desire to move beyond the organisation of work in isolation towards coordinated operations and shared tools.

4. Audiovisual Competitiveness Clusters: The Ancestors of the Grande Fabrique de l’Image ?

4.1. A Re-Enchanted Vision of the Studio: From Industrial Tool to Creative Hub

Long perceived as the dusty remnants of a bygone industrial golden age in the era of SVoD and online image consumption, film studios have, as we have seen, been undergoing a conceptual renaissance over the past decade. This renewed interest is part of a broader movement, analysed by sociologists such as Michel Lallement who, in his book L’age du faire (The Age of Doing), sees the emergence of third places—fablabs, ‘creative’ campuses, living labs, film studios—as spaces for collective creation and innovation (Lallement, 2015). From this perspective, studios are imbued with a renewed imaginary: that of active hubs where the real wealth is no longer just the technological equipment, but the human capital concentrated there that ultimately collaborates on collective projects. It is precisely this conception of the studio that is promoted by the ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ plan and subsequent France 2030 initiatives, such as the 2023 call for projects for ‘regional hubs for cultural and creative industries’. The stated objective is no longer to subsidise buildings, but to ‘catalyse ecosystems’ by designing studios as ‘clusters’ or ‘hubs’ whose function is to connect talent and projects in one place. This ambition was affirmed by Frederique Bredin, then President of the CNC, in 2019, when the Siritzky report was Published: ‘The challenge now is to make our country a filming hub for productions from around the world.’ By once again placing the emphasis on human capital, this reindustrialisation policy seeks to reconnect with the foundational utopia of cluster theory that once guided the establishment of competitiveness clusters.

5. ‘Studio-elation’ as a Doctrine

5.1. The Studio as a ‘Creative Cluster’: A New Industrial Utopia?

The idea of the film studio as a hub of creativity is illuminated by a necessary return to the origins of the concept of clusters. British economist Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) can be considered the precursor of this theory. In his Principles of Economics (1890), he coined the concept of the ‘industrial district’ after observing concentrations (clusters) of specialised industries in 19th-century England, such as cutlery in Sheffield and textiles in Lancashire. Marshall concluded that the geographical proximity of companies in the same sector produced ‘external economies’, i.e., productivity gains that do not stem from a firm’s internal organisation but from the local environment. He identified three main competitive advantages resulting from concentration: access to a pooled market for labour, the availability of specialised suppliers and services, and knowledge spillovers, which he described using the metaphor of quasi-osmotic diffusion, thereby promoting the production of new products.

In the 20th century, this Marshallian legacy was revisited and adapted to post-industrial economies by authors such as Michael Porter, Richard Florida, and Allen J. Scott. For Porter, the cluster is above all a tool for promoting the competitiveness of businesses, regions, and nations. He superimposed a neo-productivist dimension on the concept of the district, inherited from the new managerial thinking of the 1980s and 1990s: clustering must automatically increase productivity and the ability to design (co-create) new products (Porter, 1980). According to Porter, a cluster is ‘a network of geographically close and interdependent businesses and institutions, linked by common industries, technologies and know-how’ (Porter, 1990), a definition that partly matches the realities of a film studio in a digital context. Building on its territorial roots, the cluster aims to mobilise factors of competitiveness and increase the capacity of companies to produce new products (Suire, 2013).

Urban sociologist Richard Florida reverses this logic. According to him, it is not the grouping of companies that drives a region’s growth, but the human capital concentrated there. In his book The Rise of the Creative Class (2002), he takes the opposite view to Porter’s theory, arguing that the economic prosperity of cities depends on their ability to attract and retain members of the ‘creative class’ (scientists, engineers, artists, professionals, etc.). Florida argues that these individuals choose where to live based primarily on quality of life rather than employment opportunities. Companies, needing these skills, would then logically follow this movement by establishing themselves as close as possible to these employment niches. Economic clustering is therefore the consequence, not the cause, of a concentration of talent. What matters to Florida is the aggregation of the ‘3 Ts’: Talent (a stimulating environment), Technology (technological facilities and a culture of experimentation), and Tolerance (open-mindedness, diversity).

Geographer Allen J. Scott, a specialist in cultural industries, takes a middle ground between these two approaches. His research on ‘creative cities’ (Scott, 2000) describes cultural clusters as ‘nexuses’ (connection points) where flexible production networks are organised. The production of a film, a subject on which

Scott has written extensively, particularly in the urban context of Hollywood, is the result of the temporary combination of the skills of multiple small subcontracting companies. More descriptive than prescriptive, Scott reintegrates the Marshallian dimension by emphasising the division of labour within the district.

In France, these three authors are regularly cited in urban planning projects based on cultural and cre- ative industries. While Allen J. Scott enjoys unquestionable academic recognition among geographers and planners, as evidenced by his receipt of the Vautrin-Lud Prize in 2003, it is Michael Porter’s approach that has most directly influenced urban planning policies. His name was used as a leading intellectual endorse- ment in the preparatory documents for competitiveness clusters from the summer of 2004 onwards. The DATAR report accompanying the call for proposals for competitiveness clusters states that the definition of a cluster is ‘provided by Michael Porter, an economist at Harvard Business School, whose reputation has contributed to the dissemination of the concept and its widespread consideration by policymakers in many countries’ (DATAR, 2004: 89). Some analysts note that the notion of an ‘industrial cluster’, championed in the competitiveness cluster programme, is ultimately a pale imitation of the cluster model already tried and tested in Quebec (Bouinot, 2007; Gadille, 2008). Nearly twenty years after the competitiveness cluster experiment, La Grande Fabrique de l’Image is continuing this intellectual lineage by focusing on a single objective: to synthesise these approaches; by making the studio the heart of an ecosystem that must attract talent (Florida) while remaining a tool for competitiveness (Porter), the GFI goes beyond the simple logic of ‘clustering’ to hint at a policy of territorial ‘studiorisation’.

5.2. ‘Clusterisation’ of Studios or ‘Studiorisation’ of Clusters?

Logically, as with the competitiveness cluster policy, the GFI’s approach is once again largely based on the cluster theory popularised by Michael Porter. The expected benefits of such concentrations are manifold: by bringing together studios, audiovisual and animation companies, and training organisations on the same site, the aim is to stimulate creativity, increase productivity, and enhance human capital (Lusso, 2013). While the grouping of studios and film schools is not an entirely new phenomenon—one thinks of the historical proximity of the Bry-sur-Marne studios to the INA and, for a time, the ENS Louis-Lumiere; or Luc Besson’s Cite du Cinema project—these configurations were often isolated initiatives or opportunistic cohabitations. They were frequently driven by local authorities, particularly regional authorities, which oversee the Campus des metiers et des qualifications (CMQ) vocational training centres. The originality of ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ lies precisely in the fact that, for the first time, it gives these groupings national coherence and scope by systematically linking production and training. This approach is reflected in several concrete projects across the country. In Hauts-de-France, the OMC Campus project in Tourcoing directly links the creation of new studios with the establishment of a training centre. In Nouvelle-Aquitaine, the expansion of Bordeaux Studios in Illac is organically linked to the establishment of a campus for the 3iS school (Institut International de l’Image et du Son). The same logic can be found in the Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur (PACA) region, with the establishment of the Ecole des Nouvelles Images in Avignon or, further south, with the extension of Provence Studios in Martigues, which incorporates a partnership with training organisations, including the Kourtrajme school in Marseille.

5.3. ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ and the Construction of Inclusive Training Ecosystems

The link between production tools and training equipment is the central focus of the ‘La Grande Fabrique de l’Image’ programme. The breakdown of the 68 winners announced in early 2023 is clear on this point: there are 11 film studios, 12 animation studios, 6 video-game studios, and 5 special-effects studios, as well as a particularly high number of 34 training organisations (Government, 2023). The GFI’s specifications set out quantitative objectives: to double the annual number of graduates in the sector from 5,700 to 10,300, and to increase the number of jobs from 50,000 to 92,000. The geographical distribution of projects is largely based on existing balances. While two-thirds of the winners are located outside the Ile-de-France region, the remaining third are located there, confirming its pre-existing weight in the industry. The distribution in other regions also follows a logic of consolidating recognised hubs, such as in Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur, a historic location for film shoots (Studios de la Victorine) and training (Cannes, Nice). However, the example of the Occitanie region highlights a complementary approach, which could be described as ‘clusterisation by anchoring’, consisting of building hubs around already established productions. Highly successful daily television series, such as Un si grand soleil (France 2) and Nouveau jour (M6) filmed in Montpellier and its surroundings, Demain nous appartient (TF1) in Sete, and Ici tout commence (TF1) in Saint-Laurent- d’Aigouze, act as real ‘driving forces’ at the local level. They justify the construction of the Pics Studio project (in the municipalities of Saint-Gely-du-Fesc, Fabregues, and Perols), certified by the GFI, and the extension of the France.tv studios in Vendargues. This production facility is accompanied by a substantial training component. The region is home to institutions specialising in video games and animation, such as the IDEM Creative Arts School (Perpignan) and, above all, ArtFX, whose campuses (Montpellier, Lille, Paris) rank it among the world’s best schools in the visual-effects sector (The Rookies, 2023). In the cinema and audiovisual sector, two GFI winners stand out in close proximity to filming locations: the Travelling school (Montpellier, Sete), which is adding virtual-production modules to its offering, and D.E.F.I Production (Toulouse), an association that facilitates access to technical cinema professions for people from a variety of social and geographical backgrounds.

6. Critical Perspectives. The Grande Fabrique de l’Image Between Cluster Utopia and Realities on the Ground

While cluster theory provides an appealing framework for interpreting the GFI programme, its application raises several questions. The attempt to reconcile objectives of economic competitiveness with those of initial and continuing training is not without tension. Some observers, such as the Court of Auditors, ask whether this ‘desire for international competitiveness’ might erode the ‘cultural ambitions of French policies’ (Court of Auditors, 2024). In fact, a number of difficulties are inherent in establishing these creative clusters, a form of organisation with which France still has limited experience.

6.1. The Creative Cluster, a Concept That Is Still Poorly Defined

Firstly, the very notion of a cluster, on which the GFI programme is premised, suffers from an unstable definition, creating the risk of endorsing an overly expansive meaning whereby, in the eyes of public decision- makers, ‘everything becomes a cluster’, from studios to alternative third places. Researchers Sylvie Chalaye and Nadine Massard highlight the difficulty of producing a rigorous assessment because several concepts overlap:

Developing a dashboard to monitor clusters and assess their impact requires accounting for the diversity of clusters. While this diversity of forms and practices is generally recognised and supported by numerous monographs, systematic approaches to illuminate this diversity remain rare. Some studies draw on the various notions of territorialised productive networks found in the literature (districts, technopoles, innovation environments, regional innovation systems, etc.), but the proliferation of these notions, which refer more or less to the same concepts (territorialised aspect, interactions, learning dynamics), does not make this approach straightforward. This is all the more the case given that these conceptual notions are compounded by those derived from policies implemented and based on clusters: Local Productive Systems (LPS), competitiveness clusters, economic or scientific clusters in certain regions, etc. (Chalaye & Massard, 2009).

This observation of ‘theoretical vagueness’ is shared by Divya Leducq and Bruno Lusso (2011), for whom the exact boundaries of the cluster and its corollary, the ‘innovative cluster’, remain unclear within the scientific community. This lack of conceptual precision makes it all the more difficult to assess the effects of policy, especially since studies of earlier forms of clustering in France (notably Local Productive Systems) have not consistently demonstrated any significant impact on productivity.

Secondly, although the programme aims to avoid ‘spreading resources too thinly’, the distribution of its 68 winners across twelve regions tends to consolidate existing clusters (mainly in Ile-de-France, the Mediter- ranean arc, and the North). This orientation can be explained by the salience of a criterion of primary importance for live-action shooting: the availability of a skilled local workforce, without which the addi- tional costs associated with production expenses can become prohibitive. However, this logic reproduces the effect of ‘clustering the winners’ (Fontagne et al., 2010), which can exacerbate regional inequalities.

Finally, the conditions for accessing the programme are also being questioned. In a 2024 report, the Court of Auditors noted that the minimum required investment amounts (EU1 million for digital, EU10 million for film studios) rendered 15 out of 175 applicants ineligible. The financial court regrets that these thresholds, although justified by the pursuit of a ‘scale-up’, have in fact ‘led small innovative structures to give up applying’ (Court of Auditors, 2024). An analysis of the 107 rejected applications, and of their geographical distribution, could usefully complement this diagnosis by producing a comparative map of the territories mobilised for this call and those ultimately selected.

6.2. Assessing the Economic Impact of Film Shoots: A Lack of Data and Calculation Methods

In France, film and audiovisual productions benefit from a tax credit—set at 30% and 25% of eligible expenditure, respectively—capped at EU30 million, a measure whose cost in the 2025 budget is estimated at EU389 million, representing a 50% increase on 2019. This measure, regularly debated, is defended by the CNC, which emphasises the significant multiplier effect of film shoots on the local economy. Yet the promise of this knock-on effect lacks robust empirical support. The figures sometimes advanced—whether a monetary ratio (EU1 of public aid potentially generating between EU5 and EU7 in local spending) or an employment ratio (2,000 direct jobs creating 5,000 indirect jobs)—are not grounded in any validated methodology. Although the 2020 Finance Act introduced a requirement for an annual report evaluating these tax credits, the quality of the data produced remains questionable, particularly with regard to the estimation of indirect jobs, which is not anchored in a territorial reference study. By way of comparison, the Research Tax Credit (CIR), another major tax expenditure in the state budget, has been subject to more thorough evaluations. Studies conducted by France Strategie and the National Commission for the Evaluation of Innovation Policies (CNEPI) indicate that one euro of CIR borne by the state generates, on average, between EU1.2 and EU1.5 in additional R&D expenditure by companies, and little more. The most optimistic models estimate a maximum effect of EU6.5, but only in theoretical scenarios. These analyses also indicate that the effect tends to diminish over time.

Therefore, the discourse on the ‘local windfall’ generated by the economic spin-offs of film shoots, on which the GFI bases a large part of its objectives, remains largely speculative, owing to the absence of rigorous, methodologically grounded assessments capable of substantiating their purported effects on the local economy and employment.

6.3. Training Needs Identified from a Limited Sample of 40 Schools, Most of Them in the Private Sector

The emphasis on training—aimed at increasing the number of annual graduates from 5,700 to 10,300— raises a further set of questions. The needs assessment—as set out, for instance, for the “profession” (sic) of screenwriter (CNC/GFI, 2022)—indicates that the GFI’s rationale prioritises not a simple quantitative expansion to address labour shortages, but rather a qualitative reorientation of skills in response to industrial reconfigurations driven by streaming platforms. Accordingly, the GFI no longer seeks to train traditional film screenwriters but instead to cultivate “content creators” attuned to the constraints of serial writing and industrialised production for television, Netflix, or YouTube.

This shift is visible across all occupations identified as priorities: we observe the emergence of the “craftsman- manager” profile, marked by versatility and the capacity to move between creative and managerial roles, embodying the figure of the worker in post-Fordist capitalism. This corresponds to the observations of

Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello who, in Le nouvel esprit du Capitalisme (1999), describe the rise of a “connectionist” ethos centred on employability, flexibility, and project-based work. It also echoes Pierre- Michel Menger’s Portrait de l’artiste en travailleur (2003), in which he analyses how transformations of capitalism are reshaping creative work, requiring artists to become “entrepreneurs of their own careers.” For screenwriters working within studios, this entails mastering collective writing in writers’ rooms, commissioned work, and standardised formats, but also—above all—the rise of the showrunner: the creative project manager overseeing both writing and production.

In this light, the limited representation of traditional public training programmes (university degrees in film or performing arts oriented towards aesthetics, or audiovisual BTS diplomas) in the GFI’s analysis is unsurprising. With rare exceptions, these public programmes are not presently structured to provide the managerial and industrial skills expected to complement initial creative training. This prioritisation of skills, which privileges private schools considered more responsive, is not without contradictions. The GFI’s stated goal of social diversification clashes with the tuition fees charged by these institutions. The GFI estimates an average annual fee of EU6,000, a figure that underestimates the reality: according to 3is Education, in 2025, fees range from EU6,000 to EU12,000 per year for an audiovisual diploma. This raises concerns about accessibility for talented students and about the economic sustainability of enlarging the pool of audiovisual professionals as envisaged by the French government.

Apart from the three national public schools (La Femis, Louis-Lumiere, and ENSAV Toulouse), the GFI analysis mentions only one public university programme (Aix-Marseille Universite). A more complete picture would require a systematic review of all public audiovisual training programmes, including those run by consular institutions (Chambers of Trades, Chambers of Commerce and Industry), which have developed detailed expertise concerning local labour-market needs. The fragmented character of the CNC and GFI mapping of training opportunities is also apparent in its omissions. In Occitanie, for example, the absence of references to degrees offered by established public universities is striking, especially as these are long integrated into certified studios and linked to professions identified as priorities. ENSAV in Toulouse (an internal school of Universite Jean Jaures) offers programmes directly aligned with the targeted fields of stage and set design—such as the Master 1 XR in Castres and the Master Archi Decor/VFX in Toulouse—at modest tuition costs (around EU700 for three years, compared with EU900 at Louis-Lumiere and EU1,200 at La Femis). Similarly, the Master 2 programme in “Production Professions” (MPCA) at Universite Paul- Valery Montpellier 3 and the “Production” course at ENSAV are absent from the analysis.

The explanation lies in the CNC’s needs-assessment document produced for the call for proposals: the observed sample included only 40 schools, most of them private or non-profit, as suggested by the low rate of employment-outcome reporting (a requirement for public programmes evaluated by Hceres). The report noted: “Out of a panel of 40 schools observed, only 27 communicate the employment rates of their graduates, and sometimes only for certain courses” (CNC/GFI, 2022, p. 8). This weakness in the sample was confirmed in 2024 by the Court of Auditors, which reviewed the preparation of the call for projects during the COVID crisis, criticising both an “insufficient needs analysis” and a “rush to get the project off the ground” (Court of Auditors, 2024, p. 78). By basing its assessment on a network of private schools with high tuition fees, the GFI inadvertently introduced an economic barrier that contradicted its stated ambition to broaden the talent pool.

This haste was also reflected in local media reporting. In October 2022, for instance, La Provence announced works at the Martigues studios “thanks to the support of France 2030,” six months before the official results were published. According to the CNC, which was asked by the Court of Auditors to clarify the matter, this article had confused the France 2030 project with a previous EU800,000 subsidy received under a different programme (Court of Auditors, 2024, p. 79).

6.4. Attracting More Film Shoots? An Old Dream and a Complex Administrative Process

Although France is seeking to consolidate its autonomy in terms of film production and post-production facilities, it remains heavily dependent on the international market. In 2025, for example, the amount allocated to tax credits for foreign film shoots in the national finance bill decreased from EU220 million in 2024 to an estimated EU110 million in 2025. This reduction does not reflect a deliberate withdrawal of state support but is largely attributable to external factors such as the 2024 American strikes and the slowdown in investment by SVoD platforms. This paradox underscores the fact that France, aside from its daily programming for French television and films intended for its domestic market, invests in production facilities in order to attract international demand over which it has limited control.

This raises the question of the “mechanical” effect often attributed to the expansion of studio space. In terms of overall studio capacity, France currently lags behind Hungary, Germany, and the United Kingdom, with 58,000 m2 compared to 360,000 m2. Would an increase in available space automatically generate more film shoots in France, given that the country’s tax credit for foreign (and even domestic) productions remains less competitive than those of its neighbours? During the preparation of the Grande Fabrique de l’Image call for projects in 2021, the CNC commissioned three sectoral studies from McKinsey to verify Serge Siritzky’s 2019 diagnosis. Yet these studies revealed a striking contradiction: the government, through the SGPI in charge of France 2030, sought to build new production facilities even though the average occupancy rate of French studios was already relatively low (around 60%), well below that of European competitors such as the United Kingdom (95%) and Germany (80%).

This low yield can be explained by several structural weaknesses. According to the Siritzky report, the “artisanal” nature of French production hampers the continuous scheduling of studio use. A further obstacle lies in insufficiently diversified commercial models: 80–90% of French studios’ revenues come from shooting activity, compared with 50% in the United Kingdom, where complementary services play a significant eco- nomic role. Despite these shortcomings—and uncertainties surrounding land ownership—public authorities have nonetheless endorsed the creation of additional studio capacity, arguing that in France even a studio with a low occupancy rate serves as a powerful driver of regional economic activity and employment.

Another hypothesis may also account for the low occupancy rate: the limited attractiveness of the tax incentives offered by the French government, particularly the International Tax Credit (credit d’impot in- ternational, C2I). While France currently ranks fourth in Europe in terms of available studio space, it falls outside the European top ten in terms of the appeal of its international tax credit, which has been compre- hensively reformed only twice since its creation in 2004. The first reform, in 2009, raised the C2I rate from 10% to 20% and increased the ceiling to EU4 million. The second, in 2016, raised the rate to 30% of eligible expenditure and set a ceiling of EU30 million per work. A 10% bonus for productions involving a significant share of visual effects (VFX) was introduced in 2021.

By contrast, Belgium’s Tax Shelter offers a highly attractive rate of 45–54% (with an average net return to the producer of 48%). To gain a leading position among European countries competing for foreign film shoots, while continuing to modernise its studio infrastructure, France would, according to some estimates, need to increase its C2I rate from 30% to 40% and raise certain eligible expenditure ceilings. Ireland, for instance, applies a ceiling of PS125 million, whereas the French ceiling, established nearly a decade ago, has not kept pace with rising production budgets, which by 2025 are approximately 20% higher than in 2016.

To date, the French ceiling has never been reached, largely because only about 60% of foreign production spending is considered eligible due to the restricted base. Above-the-line costs are excluded, and certain categories of expenditure—such as transport and meals—are capped. Even with a rate of 40%, the ceiling would only be reached if eligible expenditure amounted to EU75 million out of a total budget of EU125 million. Yet according to the EY study (2023, p. 21), spending located in France represents on average only 50% of the total budget, which restricts the number of international projects able to reach the ceiling to a very small fraction.

The areas for improvement identified by industry professionals currently focus on three points:

Broadening the base, particularly by making extra-European above-the-line expenditure eligible;

Raising the ceilings applicable to certain expenditure categories; and

In the case of the domestic audiovisual tax credit (credit d’impot audiovisuel, CIA), increasing the rate to 30% in combination with a higher per-minute ceiling, which is currently too low for high value-added series.

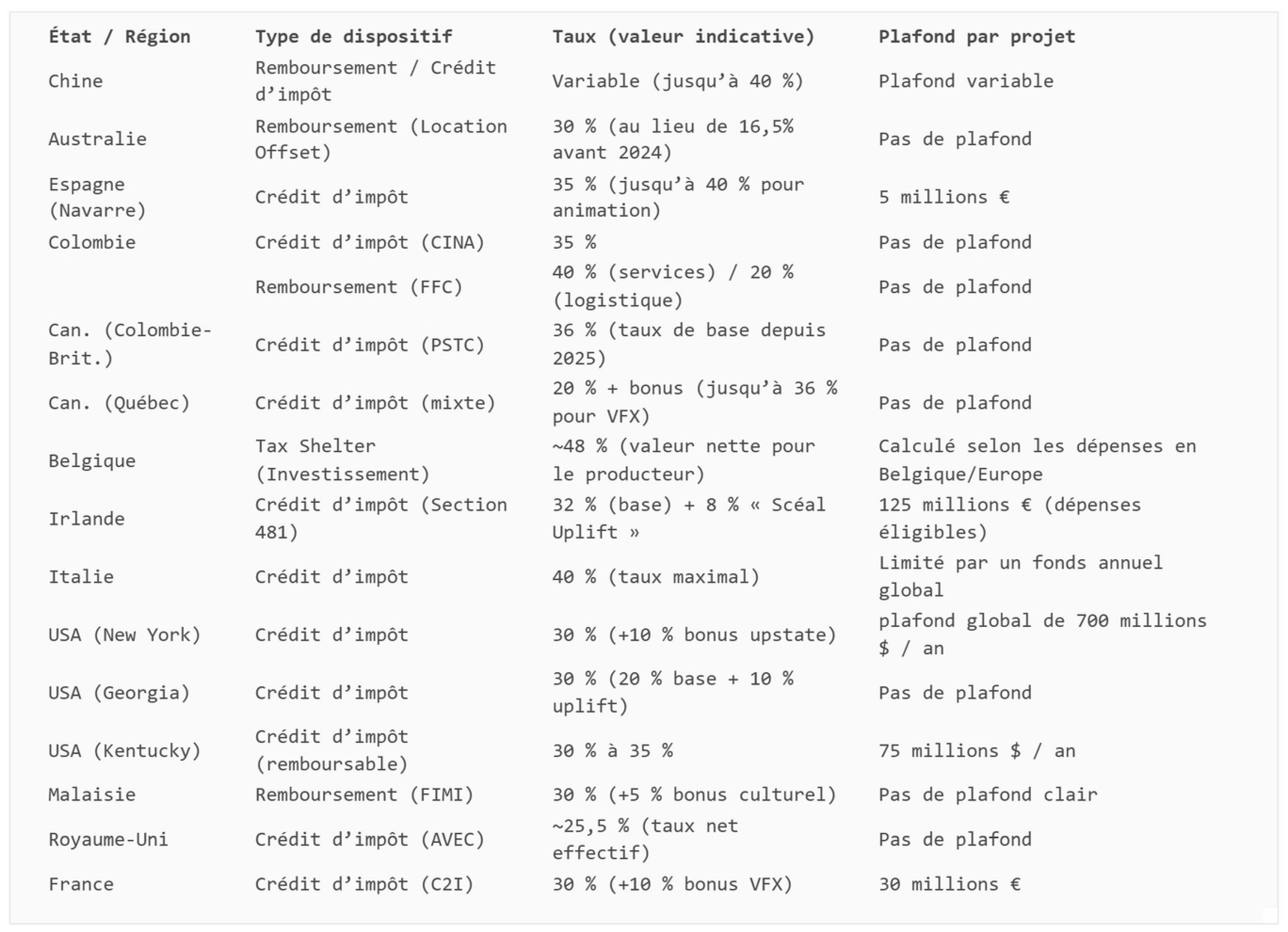

Figure 1.

Comparison of the main international tax incentives for production (2025) - Sources: author, based on data from film commissions and national government agencies (including CNC, BFI, Screen Aus- tralia, Screen Ireland, Creative BC, Proim´agenes Colombia, Comisi´on F´ılmica Colombia, Invest in Navarra, Taxshelter.be, Irish Statute Book, Film in Malaysia and Georgia Department of Revenue).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the main international tax incentives for production (2025) - Sources: author, based on data from film commissions and national government agencies (including CNC, BFI, Screen Aus- tralia, Screen Ireland, Creative BC, Proim´agenes Colombia, Comisi´on F´ılmica Colombia, Invest in Navarra, Taxshelter.be, Irish Statute Book, Film in Malaysia and Georgia Department of Revenue).

In 2019, an analysis conducted by HBO highlighted structural tensions in the global production infrastructure market, estimating global demand at 2,000 film sets against an available supply of only 1,000 (HBO, 2019). In the same year, Los Angeles—the city with the highest concentration of studios worldwide—recorded an average occupancy rate of more than 90% for its sets. France, by contrast, was already lagging significantly in both capacity and occupancy rates.

This situation created a direct risk of the relocation of studio-based segments of high-budget productions, attracted by more competitive infrastructure in Germany or the Czech Republic, a phenomenon that can result in a loss of tax revenue for producing countries. Up to now, French domestic tax credits, while not particularly successful in attracting foreign film shoots, have nevertheless helped to limit relocations of French productions—particularly since 2015 and the case of Luc Besson’s Val´erian, which was ultimately filmed in France thanks to a special amendment inserted into the finance bill submitted to the Council of State that year.

Nevertheless, this tension underscores the importance of adopting a comprehensive approach that takes into account not only available studio space and its occupancy rate but also taxation—in particular, the tax credits offered to attract both French and foreign productions, with the aim of maximising the utilisation of existing facilities. A consistent studio-support policy would therefore require the coordination of three interdependent factors: (1) the availability of infrastructure, (2) its occupancy rate, and (3) the attractiveness of tax incentives designed to sustain demand and underpin the sector’s economic model.

However, the current French administrative framework makes the implementation of such an integrated approach difficult in practice. The principal obstacle lies in the fragmentation of responsibilities among multiple agencies with distinct mandates, which illustrates the administrative complexity of support for the sector:

Studio premises are primarily owned by private operators;

The financing of new infrastructure, under France 2030 and the GFI, is managed by the General Secretariat for Investment (SGPI) and the Caisse des D´epˆots;

Training for future creative talent is split between the Ministry of Education (audiovisual BTS pro- grammes and private institutions under contract) and the Ministry in charge of Higher Education (university audiovisual and film studies programmes);

Support for the production of works themselves falls under the CNC (Ministry of Culture);

Finally, tax credits, the main fiscal instrument, are the responsibility of Bercy (Ministry of Economy and Finance).

This fragmented structure, in which no single body has an overarching perspective, hampers coordination between the various mechanisms and prevents the development of a coherent and unified policy for the sector.

6.5. Limitations Specific to Inter-Professional Collaborations Within Studios

Transposing the innovative cluster model to the studio—an approach promoted by La Grande Fabrique de l’Image—ultimately runs up against the fragmentation inherent in the French audiovisual sector, which is characterised by a multiplicity of professions, statuses, and stakeholder approaches. Coordinating work across branches (production, post-production, animation, video games, visual effects, training) remains a persistent challenge, as the cultural and creative industries are themselves compartmentalised into “silos,” each with its own cycles, economic structures, and professional cultures. Geographical proximity alone does not guarantee the smooth conduct or outcomes of joint work. Value-sharing and intellectual property regularly generate points of friction already observed in audiovisual competitiveness clusters (Lusso, 2011 & 2014). Furthermore, the heavy reliance of these existing clusters on public funding (local authorities and now France 2030) constitutes a structural vulnerability, with the risk of adding further layers to the administrative mille- feuille noted above. The shortcomings identified in the design of the call for projects are mirrored in the institutional difficulties of its principal historical actor, the CNC, which is itself ill-prepared to undertake such an industrial shift.

6.6. A CNC Ill-Prepared to Return to Supporting Technical Industries

The governance strategy of La Grande Fabrique de l’Image highlights the CNC’s (French National Film Centre) paradoxical position vis-`a-vis new industrial configurations in the audiovisual sector. The CNC was indeed involved in the programme: it participated in defining requirements, reviewing the technical aspects of applications, and selecting winners. It was not, however, the initiator. As noted above, programme mana- gement was entrusted to the Secr´etariat G´en´eral pour l’Investissement (SGPI, within the Prime Minister’s office) and to an operator, the Caisse des D´epˆots – Banque des Territoires. This configuration is not unique to the GFI and reflects the overall philosophy of the France 2030 plan. Within this scheme, the CNC—without being the final decision-making body—was responsible for implementing the process with the winners.

This situation illustrates the CNC’s difficulty—historically designed as an administration supporting creation—in adapting to sectoral reconfigurations marked by the preponderance of serialisation and rising demand for filming facilities. The institution thus found itself effectively “in tow” to an industrial movement that it had not incorporated into its own guidelines. The Siritzky report is particularly revealing in this respect: its author, Serge Siritzky, acknowledged on his blog, three years after publication, that the CNC had shown only marginal interest in the portion of his study devoted specifically to studios: “The CNC had participated in the financing of this study, but without showing any real interest in it” (Siritzky, 2022).

The CNC’s initial response, in January 2020, was a “Studio Plan” backed by very limited funding (EU1 million “to encourage ambitious projects to modernise film studios,” according to CNC President Dominique Boutonnat); subsequently, under the Recovery Plan, the “modernisation shock” programme allocated a budget of EU10 million for the same objective. The government’s shift towards the “studio cluster” model, as part of France 2030, compels the CNC to change its paradigm and, above all, its scale of intervention relative to its traditional approach and financial capacity. It must move from a logic of supporting “works” and “sectors” to one of structuring an integrated industrial “sector.”

The recent reorganisation of the CNC’s technical division is a significant development. Historically, the CNC’s technical department—dedicated to the technical industries—had limited prerogatives and resources compared with the powerful film and audiovisual directorates, which focused more on supporting content. The emergent doctrine, under France 2030, now recognises that these domains are not only fields of artistic creation but also genuine industries (the cultural and creative industries, or CCIs) requiring high-performance production tools to compete globally. For a country whose productive base is a recurrent concern, this industrial turn in cinema policy represents a historic turning point. Today, the CNC is compelled to assimilate rapidly an industrial culture it had largely neglected in favour of a creator-centred approach. This shift recalls its mission prior to 1959, when, between 1946 and 1959, the CNC operated under the supervision of the Ministry of Industry.

Conclusion

As this reflection on La Grande Fabrique de l’Image draws to a close, it is worth recalling its trajectory: despite trial and error, ambiguities, and perhaps also limitations, the France 2030 La Grande Fabrique de l’Image call for projects remains an instructive example of the turning point experienced by French cinema and its technical industries since the early 2020s. Although the resulting “French model” of the studio is more likely to resemble a cluster of activities supported by public funds—in the manner of competitiveness clusters—than an organic cluster in Porter’s sense, it nonetheless offers valuable insight into ongoing changes. In less than five years, the technical tools of French cinema have shifted from an adjustment variable to the cornerstone of an industrial policy embedded in France 2030. This change rests on three intertwined levers:

(1) the budgetary protection of the cultural and creative industries, now included in the state budget; (2) the spread of the “studio” paradigm and its corollary, the “third place,” across the creative economy; and

(3) the sometimes tense coexistence of this productivist approach with the auteurist legacy of the “cultural exception.”

This shift is first evident within the CNC itself, which is now compelled to catch up and integrate an industrial logic into its actions that is not (or rather no longer) natural to it. The recent appointment of Guillaume de Menthon, from Bry Studios, to chair the “technical resources commission” ( ) created in 2023, is a strong gesture. Designed to award grants on qualitative grounds in support of the entire technical value chain, this commission aims, in the words of CNC President (in 2023) Dominique Boutonnat, to integrate “the challenges of innovation with those of competitiveness, independence, decarbonisation and creativity.” Admittedly, support for technical industries already existed at the CNC, previously split between the CIT (Financial Support for Technical Industries) and RIAM (Research and Innovation in Audiovisual and Multimedia). Yet more than an administrative detail, this institutionalisation signals a doctrinal change that may be described as historic: filming and post-production infrastructure is no longer the subject of more or less exceptional “plans” assembled in haste, but has become a permanent strategic priority. In other words, technical industries are no longer seen as an adjustment variable, but as a pillar of French sovereignty and competitiveness.

However, this internal shift is only the visible part of a movement extending far beyond the walls of the CNC. It forms part of a groundswell led by the State through the France 2030 plan, which is orchestrating the transition of cinema from a traditional support system to a genuinely integrated industrial policy: that of the “Cultural and Creative Industries” (CCIs), a sector in the process of consolidating its scope and nascent policy. With a national acceleration strategy worth EU400 million over 2021–2025, its research component (ICCARE), and dedicated Territorial Hubs, this policy makes the grouping of creative activities—already evident in the animation sector—the nerve centre of the system: the place where investment, technology, human capital, and ultimately value creation are concentrated. The same tendency appears in other calls for proposals directly or indirectly related to CCIs: the call for “Innovative ticketing solutions”; the calls for projects for an “Augmented experience of the performing arts” and for the “Digitisation of heritage and architecture”; and, above all, the “Fabriques de territoires” (Territorial Factories), “Tiers lieux” (Third Places), and “Manufactures de proximite” (Local Manufacturing) schemes operated by the Agence nationale de la cohesion des territoires (ANCT) in conjunction with the France Tiers Lieux association, which adopt an explicitly Porterian definition of the Third Place as a creative cluster and “innovation studio.” With EU45 million in funding, the “New Places, New Connections” programme has supported the development of 300 third places—half located in priority neighbourhoods identified by urban policy and the other half in rural areas and outside major urban centres. To date, nearly 220 “Fabriques de Territoires” have been certified across France. Better still, the term “studio” has spread to other segments of the economy. It appears in calls for the creation of Bpifrance’s French Tech Acceleration I and II funds, designed to invest directly in acceleration structures: “start-up studios.” These start-up studios—intended to incubate start- ups—are also known as start-up factories, company builders, or venture builders, thereby reinforcing an image of innovation directly modelled on the studio. Here we see, in concrete form, the connection between the semantics of innovation and those of creativity, to which the term “studio” has hitherto been indebted.

Yet this industrial and creative transition is not without resistance. The government’s difficulty in articu- lating a comprehensive national strategy for cultural and creative industries seems to stem from persistent ideological and administrative frictions, particularly between the SGPI and the French Ministry of Culture. In a country where support for cinema has long been synonymous with defending the “cultural exception” centred on the figure of the author, proclaiming the “technical quality” of French studios as a pillar of national competitiveness and a source of new creativity is a powerful gesture. Yet in doing so, the doctrine that we have described in this article as “studiorisation” paradoxically revives an imaginary long thought to be past. By making industrial tools the new temple of creation, it recalls the celebrated cinema of ”Qualite francaise” during the 1930s to 1950s, characterised precisely by the primacy of studio shooting and the pro- motion of technical know-how (Gimello-Mesplomb, 2014; Montarnal, 2018; Vincendeau, 2024; Sellier, 2024). Only time will tell whether this return to industrial order will succeed in reconciling itself with the artistic legacy of auteur theory, on which the doctrine of support for French cinema has rested since the mid-1950s.

References

- Asheim, B., Cooke, P., & Martin, R. (2006). The rise of the cluster concept in regional analysis and policy: A critical assessment. In B. Asheim, P. Cooke, & R. Martin (Eds.), Clusters and regional development: Critical reflections and explorations (pp. 1–19). Routledge.

- Banks, M. (2017). Creative justice: Cultural industries, work and inequality. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Becattini, G. (1981). Le district industriel: milieu creatif (pp. 147–164). Eres. [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F., & Parkinson, M. (Eds.). (1993). Cultural policy and urban regeneration. The West European experience. Manchester University Press.

- Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, E. (1999). Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme. Gallimard.

- Bouinot, J. (2007). Les poles de competitivite: le recours au modele des clusters ? Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, Chronique d’economie geographique, document 4961.

- Braczyk, H.-J., Fuchs, G., & Wolf, H.-G. (1999). Multimedia and regional economic restructuring. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Chalaye, S., & Massard, N. (2009). Les clusters: Diversite des pratiques et mesures de performance. Revue d’economie industrielle, 128, 153–176. [CrossRef]

- Chantepie, P., & Le Diberder, A. (2010). Revolution numerique et industries culturelles. La Decouverte. Creton, L. (2024). L’economie du cinema en 50 fiches. Armand Colin.

- Daumas, J.-C. (2007). Dans la boite noire des districts industriels. In J.-C. Daumas, Prenom Lamard, & Prenom Tissot (Eds.), Les territoires de l’industrie en Europe (1750–2000): Entreprises, regulations, trajectoires (pp. 9–34). Presses universitaires de Franche-Comte.

- Duval, J. (2012). Critique d’une analyse economique du cinema. Revue Francaise de Socio-Economie, 10(2), 137–153. [CrossRef]

- Duval, J. (2016). Conclusion: L’autonomie en question. In Le cinema au XXe siecle: Entre loi du marche et regles de l’art (pp. 249–269). CNRS Editions.

- Fontagne, L., Koenig, P., Mayneris, F., & Poncet, S. (2010). Clustering the winners: The French policy of competitiveness clusters (CEPII Working Paper No. 2010-18). CEPII.

- Gadille, M. (2008). Le tiers comme agent de reflexivite et accelerateur d’apprentissages collectifs: le cas du dispositif des poles de competitivite. Humanisme et entreprise, 289, 61–79.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2025). Hundred years of French Film Policy (1925–2025). Power, policy, and aes- thetic values within state intervention for film production in France https://shs.hal.science/halshs- 04824374v1. ¡halshs-04824374¿ HAL.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2025). Le studio comme nouvelle doctrine des Industries Culturelles et Creatives ? Une analyse du dispositif ¡¡ La grande fabrique de l’image ¿¿ (France 2030). Mise au point , 21, URL : http:.

- //journals.openedition.org/map/8669 ; DOI : . [CrossRef]

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2024) The Invention of the Spectator : How has Early film Spectatorship shaped Audience and Reception Theory. Selected Writings (1900s-1910s). New York - London: OpenCulture Academic Publishing, p. 230. [CrossRef]

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2021). Foreword. In Charlie Michael. French Blockbusters: Cultural Politics of a Transnational Cinema, Edinburgh University Press, pp.xiv-xviii, 2021, Traditions in World Cinema, 9781474484275. ¡10.1515/9781474424240¿. ¡hal-04464754¿.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2014). La “qualite” comme clef de voute de la politique francaise du cinema: Retour sur la genese du regime de soutien selectif a la production de films (1953–1959). In D. Vezyroglou (Ed.), Le cinema: une affaire d’Etat 1945–1970 (pp. 55–75). La Documentation francaise / Comite d’histoire du ministere de la Culture. ¡halshs-00997949¿.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2012). Trois nouvelles ¡¡ zones grises ¿¿ au prisme des evolutions sociotechniques du cinema: economie de la notoriete, incertitude et phenomenes de traines. Mise au Point, 4(4), 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2003). The economy of 1950s popular French cinema. Studies in French Cinema, 2006, 6 (2), pp.141-150. ¡halshs-01808380¿.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. (2000). Enjeux et strategies de la politique de soutien au cinema francais. Un exemple: la Nouvelle Vague. Sciences de l’information et de la communication. Universite Toulouse le Mirail, 2000. Francais. ¡NNT : 2000TOU20056¿. ¡tel-05389657¿.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. (2019). The cultural industries (4th ed.). Sage.

- Kitsopanidou, K., & Layerle, S. (2020). Introduction. In H. Fleckinger, K. Kitsopanidou, & S. Layerle (Eds.), Metiers et techniques du cinema et de l’audiovisuel. Sources, terrains, methodes (pp. 15–26). Peter Lang.

- Leducq, D., & Lusso, B. (2011). Le cluster innovant: conceptualisation et application territoriale. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, Espace, Societe, Territoire, document 521.

- Lecler, R. (2010). La mue des ¡¡ gaspilleurs de pellicule ¿¿. Ou comment les cineastes militants ont rehabilite la notion d’auteur (1968–1981). Raisons politiques, 39(3), 29–61. [CrossRef]

- Liefooghe, C. (2009). La creativite: une ressource pour le developpement economique d’une region de tradition industrielle ? Paper presented at XLVI? colloque de l’ASRDLF, Clermont-Ferrand, 15 pp.

- Lusso, B. (2013, 1er novembre). Pˆoles transm´edia, actions d’interm´ediation et construction de liens au sein de l’industrie du multim´edia des aires m´etropolitaines de Lille, Lyon et Marseille. Revue Interventions.

-

´economiques, 48. Consult´e le 7 juillet 2025. [CrossRef]

- McRobbie, A. (2015). Be creative: Making a living in the new culture industries. Polity.

- Marichez, N. (2024, 1er juillet). Ombres et lumi`ere: approches g´eographiques des tournages de films et de s´eries et de leur impact sur le territoire dans le Nord-Pas-de-Calais et en Wallonie (Doctoral dissertation). Universit´e de Lille. Disponible sur Theses.fr.

- Menger, P.-M. (2003). Portrait de l’artiste en travailleur: m´etamorphoses du capitalisme. Seuil. Mi`ege, B. (2000). Les industries du contenu face `a l’ordre informationnel. PUG.

- Montarnal, J. (2018). La Qualit´e fran¸caise: un mythe critique ? L’Harmattan.

- Observatoire de France Tiers-Lieux. (2025, juillet). Panorama de la recherche sur les tiers-lieux en France (Cahiers de recherche de France Tiers-Lieux, n° 1). France Tiers-Lieux. https://www.editionsbdl.com/wp- content/uploads/2025/07/Cahiers_de_recherche_de_France_Tiers-Lieux.pdf.

- Porter, M. E. (1998). On competition. Harvard Business Review Press. Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press.

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press. Power, D., & Scott, A. J. (Eds.). (2004). Cultural industries and the production of culture. Routledge.

- Raffin, F. (2023). Faire en commun. In M.-P. Bouchaudy & F. Lextrait (Dirs.), (Un) ab´ec´edaire des friches.

- (pp. 77–78). Sens & Tonka.

- Raffin, F. (2023). La culture dionysiaque des friches culturelles et ses influences sur les tiers-lieux culturels. Culture & Mus´ees, 45 | 2025. http://journals.openedition.org/culturemusees/12557 https://doi. org/10.4000/141ch.

- Raffin, F. (2025, juillet). Culture du faire dans les tiers-lieux et ´evolution de l’action publique: L’institutionnalisation culturelle comme processus de couplage. Cahiers de recherche de l’Observatoire des tiers-lieux.

- Ross, A. (2009). Nice work if you can get it: Life and labor in precarious times. NYU Press.

- Rot, G. (2019). Planter le d´ecor. Une sociologie des tournages. Presses de Sciences Po.

- Rot, G. (2023). Hi´erarchies au travail sur les plateaux de tournage. Germinal, 6(1), 266–277.

- Scott, A. J. (2000). The cultural economy of cities: Essays on the geography of image-producing industries. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Scott, A. J. (2005). On Hollywood: The place, the industry. Princeton University Press.

- Scott, A. J. (2006). Creative cities: Conceptual issues and policy questions. Journal of Urban Affairs, 28(1), 1–17.

- Sellier, G. (2024). Le culte de l’auteur: Les d´erives du cin´ema fran¸cais. La Fabrique.

- Sennett, R. (1998). The corrosion of character: The personal consequences of work in the new capitalism.

- W. W. Norton.

- Siritzky, S. (2022, 17 janvier). L’enjeu majeur du tournage en studio. Blog Siritz. https://siritz.com/editorial/lenjeu-majeur-du-tournage-en-studio/.

- Siritzky, S. (2021, 6 avril). Choc de modernisation pour les studios. Blog Siritz. https://siritz.com/ editorial/choc-de-modernisation-pour-les-studios/.

- Siritzky, S. (2019, 14 mai). Les studios de tournage, un enjeu primordial pour la production en France.

- (Rapport command´e par le CNC et Film France). CNC / Film France.

- Suire, R., & Vicente, J. (2013). Lock in or lock out? How structural properties of knowledge networks affect regional resilience. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(1), 199–219. [CrossRef]

- Talbot, D. (2013). Clusterisation et d´elocalisation: Les proximit´es construites par Thales Avionics. Revue fran¸caise de gestion, 234(5), 15–26.

- Vincendeau, G. (2024). Cin´ema th´eˆatral: stardom and performance in the tradition of quality. French Screen Studies, 25(1–2), 100–124. [CrossRef]

- Assembl´ee nationale. (2019). Rapport d’information n° 1172 sur l’application des mesures fiscales [Rapport Gouriau] (15? l´egislature).

- Borne, E´. (2023, 4 juillet). R´ef´er´e relatif au Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC) – R´ef. S2023-0769. Cour des comptes.

- Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC), & Ernst & Young. (2014). E´valuation des dispositifs de cr´edit d’impˆot.

- Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2020, 16 janvier). Le CNC lan- ce un “plan studios” pour moderniser les plateaux de tournage fran¸cais [Communiqu´e de pres- se]. https://www.cnc.fr/professionnels/actualites/le-cnc-lance-un--plan-studios--pour- moderniser-les-plateaux-de-tournage-francais_1111847.

- Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2023, juillet). E´valuation de l’impact des cr´edits d’impˆot relevant du CNC de 2017 `a 2021 (´etude prospective). CNC / EY Consulting.

- Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2022). Appel `a projets La Grande Fabrique de l’image – Plan France 2030. CNC.

- Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2022). E´tude de besoins – studios de tournage (GFI). CNC.

- Cour des comptes. (2023). Observations d´efinitives: Le Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC) (S2023-0722).

- Cour des comptes. (2024, mars). Les cr´edits exceptionnels `a la culture et aux industries cr´eatives. Cour des comptes.

- Cour des comptes. (2025). Le budget de l’E´tat en 2024 – Investir pour la France de 2030. Cour des comptes. DATAR – D´el´egation interminist´erielle `a l’Am´enagement du Territoire et `a l’Attractivit´e R´egionale. (2004).

-

La France, puissance industrielle: une nouvelle politique industrielle par les territoires – E´tude prospective.

- La Documentation franc¸aise.

- Ernst & Young, & Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2014). E´valuation des dispositifs de cr´edit d’impˆot (cin´ema, audiovisuel, international, jeu vid´eo).

- Ernst & Young, & Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2023). E´valuation de l’impact des cr´edits d’impˆot relevant du CNC (2017–2021).

- Ernst & Young, & Centre national du cin´ema et de l’image anim´ee (CNC). (2025, 10 juillet). E´valuation de l’impact des cr´edits d’impˆot relevant du CNC de 2017 `a 2023.

- Hamac Conseils, & Mazars. (2014). E´tude comparative des cr´edits d’impˆots en Europe et au Canada: cin´ema, audiovisuel, jeux vid´eo.

- Inspection g´en´erale des finances, & Inspection g´en´erale des affaires culturelles. (2018). Rapport sur l’´evaluation des divers cr´edits d’impoˆts g´er´es par le minist`ere de la Culture.

- Minist`ere de la Culture, & Secr´etariat g´en´eral pour l’investissement (SGPI). (2023). Dossier de presse – Annonce des laur´eats de l’appel `a projets “La Grande Fabrique de l’image” du plan France 2030.

- Netflix. (2019, July 3). Netflix creates UK production hub at Shepperton Studios [Communiqu´e de presse].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).