3.1. Characteristics of Postural Defects According to Author’s Typology

Taking the normative ranges of thoracic kyphosis (42°-55°) and lumbar lordosis (33°-47°) into account it is possible to distinguish nine clinically significant types of body posture, resulting from the combination of the values of both spinal curvatures. These configurations include postures characterised by reduced thoracic kyphosis coexisting with reduced, normal or increased lordosis (K < 42°; L < 33°; 33° ≤ L ≤ 47°; L > 47°). Similarly, for kyphosis within the normative range (42° ≤ K ≤ 55°), postures with reduced, normal or increased lumbar lordosis are distinguished. The last set includes configurations in which kyphosis is increased (K > 55°), while lordosis can demonstrate values below, within or above the norm (L < 33°; 33° ≤ L ≤ 47°; L > 47°). This classification model allows for unambiguous categorisation of posture based on precise morphological criteria, constituting an important point of reference in clinical assessment, diagnostic planning and biomechanical analysis of postural disorders (

Table 1).

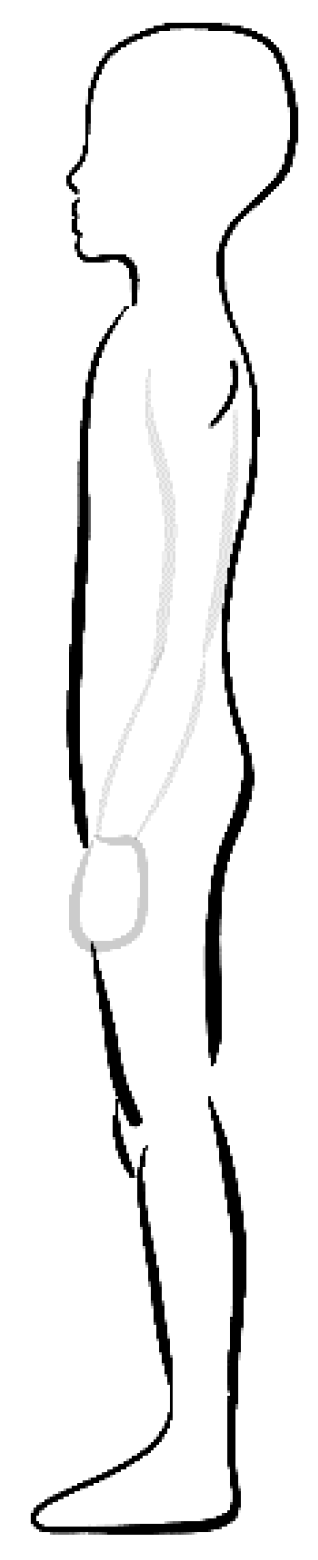

In recent years, the incidence of this type of posture has intensified, and in the subject-literature, it is increasingly emphasized that modern environmental conditions—especially limited physical activity and greater exposure to static positions—contribute to the flattening of physiological spine curvatures [

29,

30,

31]. In the school-aged population, this configuration occurs in approximately 16% of children, making it one of the most common types of incorrect posture [

8].

Such a pattern reflects the predominance of global muscles over segmental ones, which leads to increased stiffness and reduced effectiveness of postural control [

28,

29]. This is characterised by flattening of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis, causing reduced load absorption and stiff trunk function. Hyperactivity of the thoracic erector spinae and dominance of the scapular retractors (middle trapezius, rhomboids) coexist with hypoactivity of the serratus anterior and weakened function of the pectoral muscles, which contributes to impaired scapulocostal rhythm [

30,

31]. In the cervical segment, a typical “head-forward” pattern is observed—head protrusion, decreased cervical lordosis, compensatory upper cervical extension and overloading of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles, with simultaneous weakness of the longus colli/capitis [

32,

33]. In the lumbar-pelvic region, decreased lordosis coexists with posterior pelvic tilt, hyperactivity of the rectus abdominis and hamstrings, as well as hypoactivity of the local stabilisers (transversus abdominis, multifidus). Weakness of the iliopsoas and lumbar erector spinae reduces the ability to maintain stabilisation and proper movement segmentation [

34,

35]. The gluteus maximus often exhibits increased tonus, while the gluteus medius and minimus are weakened, which impairs hip joint control and affects compensation during weight-bearing of the lower limbs [

36,

37]. The hips tend to flex due to posterior pelvic tilt and shortened hamstrings. Slight deflection or increased stiffness is observed in the knee joint, which is a reaction to a backwards shift in centre of gravity and a compensatory increase in hamstring tension [

38]. Shifting the load axis leads to foot supination, reduced gastrocnemius/soleus activity, and limited foot adaptation during the stance phase [

39]. This pattern is associated with trunk stiffness, neck and lower back pain, restricted thoracic rotation, shallow upper rib breathing and reduced postural efficacy. These disturbances impede postural adaptation in dynamic conditions and promote the development of global compensations [

40].

Shortened muscles: SCM, suboccipitals, thoracic erector spinae, middle trapezius, rhomboids, rectus abdominis, hamstrings, gluteus maximus.

Elongated muscles: longus colli/capitis, serratus anterior, pectoralis major/minor, upper trapezius, iliopsoas, rectus femoris, lumbar erector spinae, TA, multifidus, gastrocnemius/soleus, gluteus medius/minimus [

28]. This pattern includes trunk stiffness, neck and lumbar pain, limited thoracic rotation and shallow upper rib breathing. This may include impaired pelvic stabilisation, reduced postural efficacy, rapid fatigability in static positions, as well as a tendency to supinate the feet and overload the hindfoot. The pattern induces global compensations and reduced movement efficiency [

41].

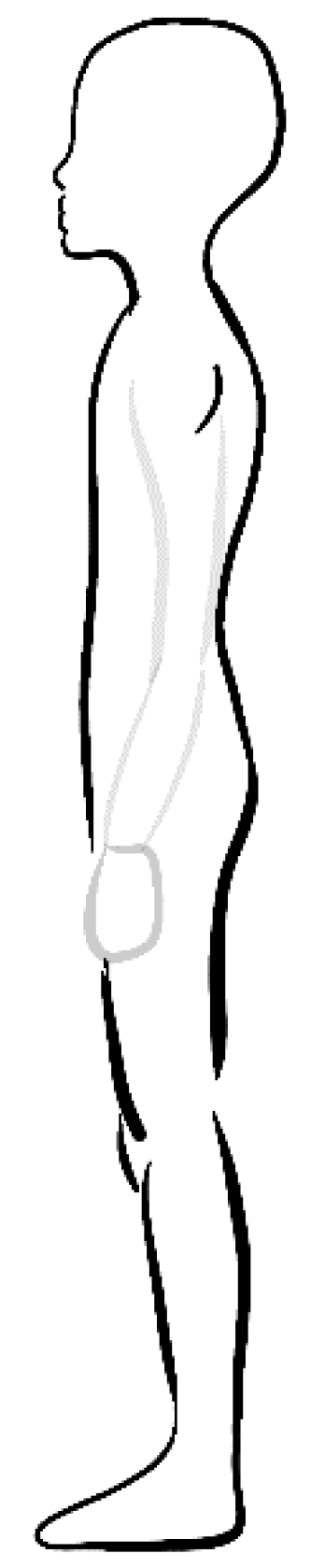

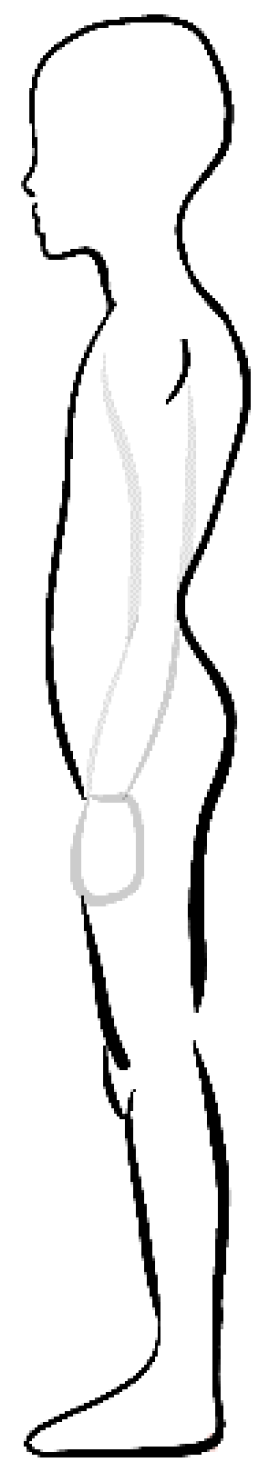

Figure 1.

Reduced thoracic kyphosis, reduced lumbar lordosis (K < 42°; L < 33°).

Figure 1.

Reduced thoracic kyphosis, reduced lumbar lordosis (K < 42°; L < 33°).

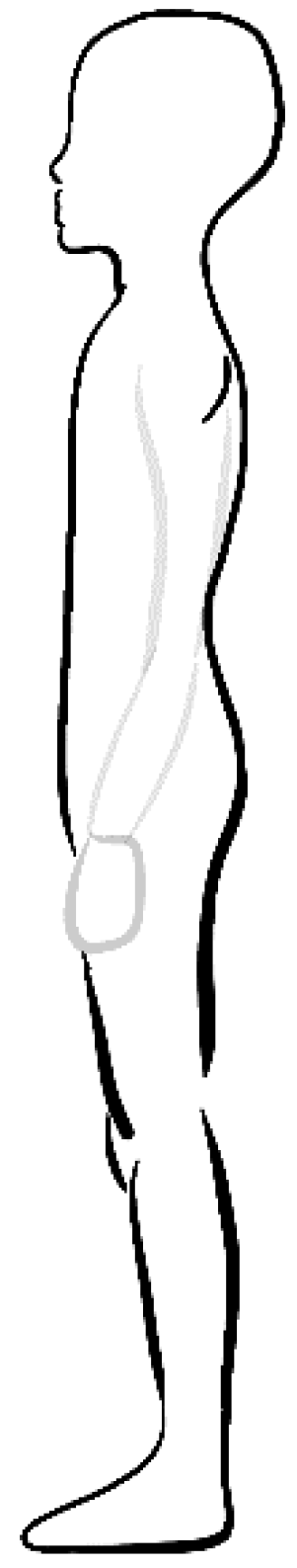

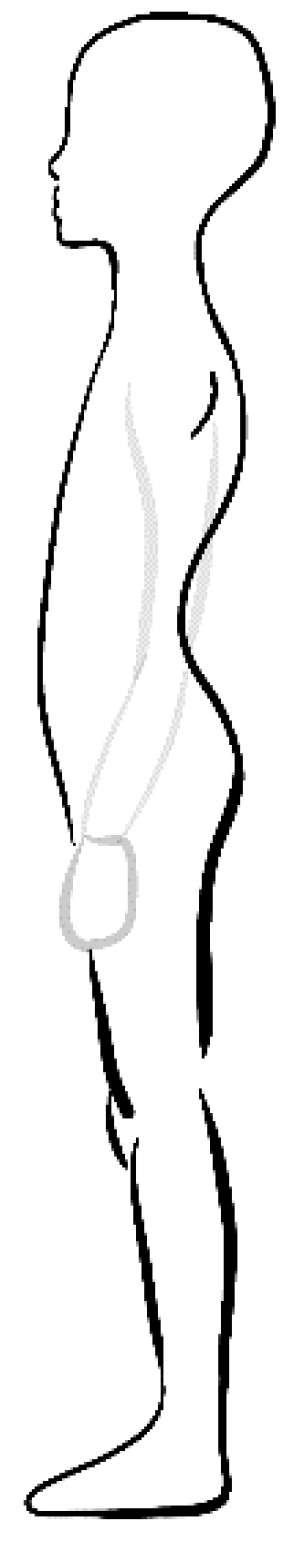

This type of posture is characterised by a flattening of physiological thoracic kyphosis, with preserved normal lumbar lordosis (

Figure 2). The defect occurs in approximately 22% of children [

8]. The pattern indicates a predominance of the global muscles of the shoulder girdle and trunk with weakened segmental control, which affects the quality of thoracic spine alignment. It is characterised by flattening of the thoracic spine with preserved lumbar lordosis [

30,

31,

32]. Reduced kyphosis results from dominance of the thoracic erector spinae and predominance of the middle trapezius and rhomboids, which maintain the scapula in retraction and slight depression. The serratus anterior and pectoralis major/minor remain elongated and hypoactive, which disrupts normal scapulocostal rhythm. In the cervical spine, head protrusion and decreased lordosis are often noted, with excessive activity of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles as well as weakness of the longus colli/capitis. Lumbar lordosis is preserved, but segmental stabilisers (transversus abdominis, multifidus) may be weakened, which favours compensatory activity of the global muscles. The hip joint is usually closer to neutral position, with a slight tendency to flex [

33]. The knee joint typically exhibits a stiff, slightly flexed or neutral position, resulting from a posterior shift of the centre of gravity as well as insufficient pelvic and hip control. The lower limbs usually do not exhibit as strong compensation as in the case of posterior tilt; however, flattening of the thoracic segment can disrupt trunk balance and foot loading. The gluteus maximus is usually normal or shows a slight increase in stabilising tonus, while the gluteus medius may be hypoactive because of limited pelvic control in the frontal plane.

Shortened muscles: SCM, suboccipitals, thoracic erector spinae, middle trapezius, rhomboids.

Elongated muscles: longus colli/capitis, serratus anterior, pectoralis major/minor, upper trapezius, gluteus medius, and partially segmental stabilizers (TA, multifidus) [

28]. Thoracic spine stiffness, limited trunk rotation, neck pain resulting from suboccipital muscle overload and shallow upper rib breathing are observed. Effective scapular function and shoulder girdle stabilisation are hindered, which can lead to neck and shoulder overloading as well as reduced economy of upper limb movement. Lumbar lordosis remains stable, but global trunk mobility and functional flexibility become restricted [

34].

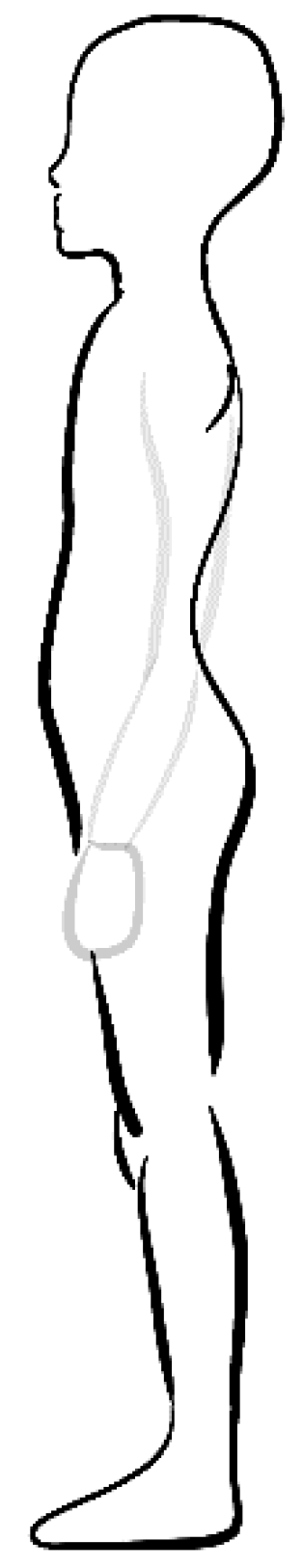

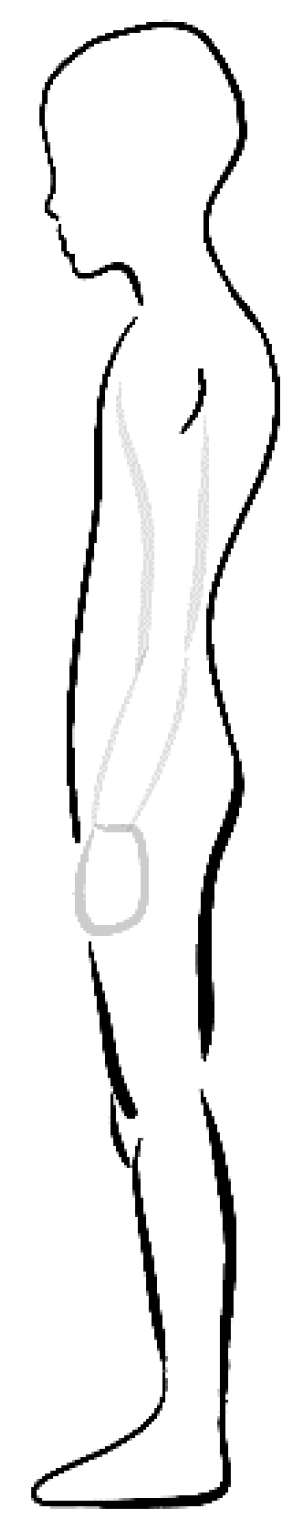

This pattern reflects the predominance of global extensor mechanisms in the lumbar and global retraction patterns of the thoracic spine, with reduced activity of segmental stabilizers. It combines flattening of the thoracic spine with increased lumbar lordosis (

Figure 3). This pattern fuses reduced thoracic kyphosis with increased lumbar lordosis and occurs in approximately 5% of children [

8]. The configuration reflects the predominance of global extensor mechanisms and reduced integration regarding the axis of the body, leading to impaired adjustment and balance responses. Reduced kyphosis results from overactivity of the thoracic erector spinae and scapular retractors (middle trapezius, rhomboids), with concomitant hypoactivity of the serratus anterior and secondary lengthening of the pectoralis major/minor. A consequence of this is limited thoracic mobility and impaired scapular-costal coordination. In the cervical spine segment, protraction of the head, shallowing of central lordosis and compensatory extension of the upper cervical segment (C0-C2) are observed [

34]. This arrangement favours dominance of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles and inhibition of the longus colli/capitis, which disrupts craniocervical integration and the precision of balance reactions.

Increased lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt reflect the predominance of the iliopsoas, rectus femoris and lumbar erector spinae over the local stabilisers (transversus abdominis, multifidus). Segmental lumbar stabilisation is reduced and postural control relies on global stiffness. Weakness of the gluteus maximus and medius limits pelvic and hip stabilisation. Extension strategies dominate in the hip joints, which increases loading on the anterior compartment and intensifies kinematic compensations. An anterior shift of the centre of gravity increases forefoot loading and promotes pronation of the feet, requiring compensatory activation of the gastrocnemius, soleus and tibialis posterior. Hyperextension is common in the knee joint, representing a passive stabilisation strategy when proximal control is ineffective.

Shortened muscles: thoracic erector spinae, middle trapezius, rhomboids, iliopsoas, rectus femoris, lumbar erector spinae, gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis posterior, sternocleidomastoid, suboccipitals.

Elongated muscles: serratus anterior, pectoralis major/minor, upper trapezius, longus colli/capitis, rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis, multifidus, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius [

28,

35,

36]. Clinically, hyperextended posture, limited trunk rotation, overloading of the cervical and lumbar spine as well as postural control disorders result from dominance of global extension patterns.

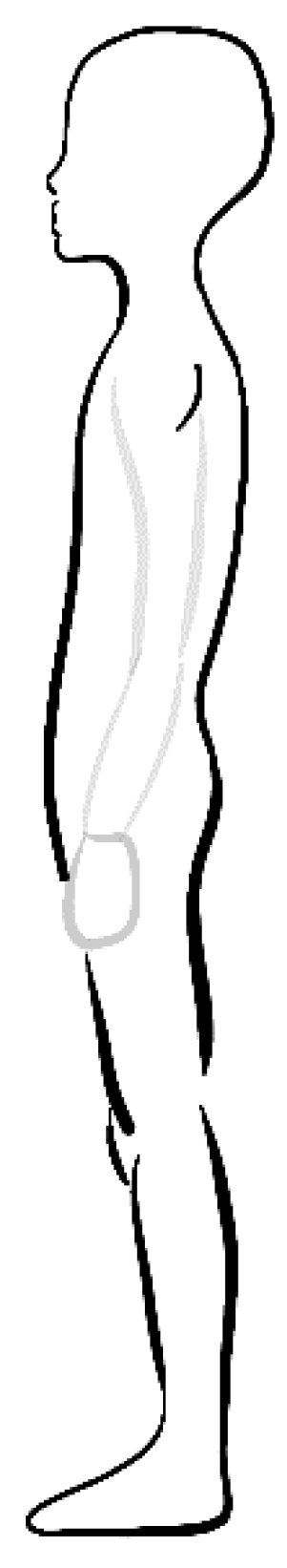

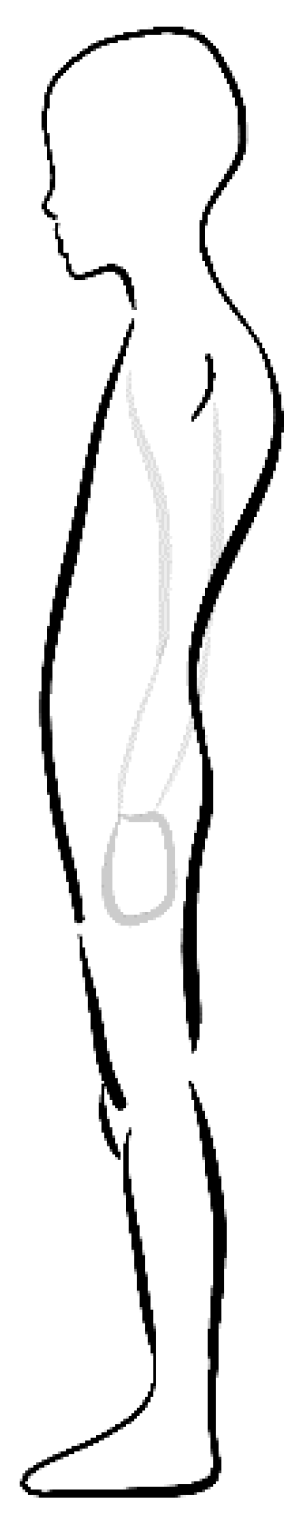

This postural type is characterised by a normal degree of thoracic kyphosis with reduced lumbar lordosis (

Figure 4). It occurs in approximately 6% of children [

8]. The given pattern indicates the predominance of global lumbopelvic flexion strategies with weakened activity of segmental central stabilizers. It is characterised by normal thoracic kyphosis with a shallowing of lumbar lordosis, reflecting the predominance of lumbopelvic flexion patterns and weakened central stabilisation mechanisms. Posterior pelvic tilt results from overactivity of the rectus abdominis and hamstrings, while local stabilizers (transversus abdominis, multifidus) remain hypoactive, limiting the ability to generate pressor control of the trunk. Although thoracic kyphosis remains physiological, compensatory stiffness of the lower segments reduces trunk segmentation and decreases the effectiveness of adjustment responses in a dynamic environment. In the cervical spine, head protraction and decreased cervical lordosis are frequently observed, leading to the dominance of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles. Weakness of the longus colli/capitis disrupts craniocervical integration, impairs head-to-trunk adjustment responses, and limits sagittal balance precision. In the lumbar spine, decreased lordosis, elongated iliopsoas and lumbar erector spinae, as well as weakened segmental mechanisms reduce the ability of forward and backward control, which affects the quality of balance responses concerning the entire axis of the body. Hypoactivity of the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius impairs hip and pelvic stabilisation—key reference points in antigravity posture. Flexion dominates in the hips, increasing reliance on trunk compensation in balance strategies. A posterior shift of the centre of gravity promotes foot supination and reduced gastrocnemius/soleus activity. A slight flexion strategy is common in the knees, representing a passive stabilisation response to proximal postural control failure. This pattern results in reduced efficiency of the lower segment balance responses and limited adaptation to load-bearing tasks.

Shortened muscles: rectus abdominis, hamstrings, sternocleidomastoid, suboccipitals and sometimes the gluteus maximus (tonic tension).

Elongated muscles: iliopsoas, rectus femoris, lumbar erector spinae, transversus abdominis, multifidus, gluteus medius/minimus, longus colli/capitis, gastrocnemius and soleus [

28]. A person with this pattern exhibits shallow lumbar lordosis and posterior pelvic tilt, which contribute to low back pain, weakened central stabilisation and ineffective hip extension. Head protrusion leads to neck strain and compensatory work of the global muscles reduces trunk flexibility. Loading the hindfoot and a tendency to supinate can cause ankle strain and balance disorders [

42].

This is the only normal type of body posture. It is characterised by correct degrees of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis (

Figure 5). It occurs in approximately 29% of subjects [

8]. This suggests that 71% of subjects have defective body posture types [

8]. The pattern is characterised by the harmonious cooperation of global and segmental muscles, allowing for optimal maintenance of spinal curvatures and effective postural control. It reflects the correct configuration of spinal curvatures, in which thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis are within the physiological range. This trunk positioning promotes effective load transfer, optimal shock absorption as well as full cooperation of global and local muscles. Balance between the activity of the thoracic erector spinae, scapular stabilisers and abdominal muscles ensures proper postural control without excessive compensation. In the cervical spine, a neutral head position is most often observed with preserved cervical lordosis and balance between the deep (longus colli/capitis) and global muscles (sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius) [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. In the pelvic and lumbar regions, segmental stabilisers—the transversus abdominis and multifidus—work together with the gluteus maximus and medius, ensuring proper stabilisation of the body’s core. The lower limbs demonstrate harmonious functioning with proper foot loading and a stable longitudinal arch. There are no significant advantages related to length or tension. Local and global muscle function is balanced, and any minor symmetries are physiological in nature. There is a lack of patterns typical for dysfunction: neither shortening that induces compensation nor lengthening which leads to decreased stability. The person demonstrates balanced posture, proper mobility and trunk stability, and no characteristic overloads resulting from changes in spinal curvature. The muscular system functions effectively, and the risk of compensation or overloading of the neck, thoracic spine or lumbar spine is minimal. Movements are fluid, economical and do not produce typical pain symptoms [

43].

This type of posture is characterised by a normal degree of thoracic kyphosis accompanied by increased lumbar lordosis (

Figure 6). It occurs in approximately 12% of subjects [

8]. This pattern reflects the dominance of global extension mechanisms in the lumbopelvic segment and the insufficiency of central stabilisation. Anterior pelvic tilt increases the activity of the iliopsoas, rectus femoris and lumbar erector spinae, perpetuating hyperextension and reducing segmentation ability. The local stabilisers (transversus abdominis, multifidus) remain elongated and hypoactive, which impairs tonus control and the precision of adjustment responses. In the cervical spine, normal or slightly protruded head positioning can be observed. The dominance of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles compensates for the anterior shift of the trunk, disrupting craniocervical mechanisms and balance responses. The gluteus maximus and gluteus medius muscles are elongated and weakened, which compromises hip stabilisation [

43,

44,

45]. A tendency to extend the hip joint occurs, increasing anterior compartment overload and limiting functional flexion during gait. Hyperextension is common in the knee joint, representing a passive stabilisation strategy with insufficient proximal control. Anterior shift of the centre of gravity increases forefoot loading and promotes foot pronation. This results in compensatory activation of the gastrocnemius, soleus and tibialis posterior. The foot loses the ability to precisely modulate stiffness during the stance phase, reducing the efficacy of balance responses.

Shortened muscles: iliopsoas, rectus femoris, lumbar erector spinae, gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis posterior.

Elongated muscles: transversus abdominis, multifidus, rectus abdominis, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, partially longus col-li/capitis. Clinically, hyperextended posture, lumbar overload, weakened pelvic stabilisation and ineffective balance reactions are predominant.

This type of posture is characterised by increased thoracic kyphosis accompanied by decreased lumbar lordosis (

Figure 7). It occurs in approximately 1% of subjects [

8]. The pattern demonstrates a predominance of global flexion strategies in the shoulder girdle and trunk and weakening of segmental central stabilisation, leading to loss in segmented movement. This pattern combines excessive thoracic kyphosis with decreased lumbar lordosis, indicating a predominance of flexion patterns and reduced integration of antigravity mechanisms. Increased kyphosis results from hyperactivity of the pectoralis major/minor and weakness of the back muscles (thoracic erector spinae, middle/lower trapezius, rhomboids), which limits trunk rotation and worsens postural responses. In the cervical spine, head protraction, decreased medial lordosis and compensatory upper cervical extension occur [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Dominance of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles, along with weakened longus colli/capitis, disrupts head-trunk integration and sagittal balance responses. In the lumbopelvic segment, decreased lordosis and posterior pelvic tilt result from tension in the rectus abdominis and hamstrings, as well as hypoactivity of the local stabilisers (transversus abdominis, multifidus). Weakened iliopsoas and lumbar erector spinae limit the generation of central stabilisation. The gluteus maximus and medius are hypoactive, reducing hip stability. Flexion dominates in the hips, weakening control during weight-bearing tasks. The knees typically exhibit slight flexion, being a passive stabilising strategy in the case of poor proximal control. A posterior shift in centre of gravity promotes foot supination and reduced gastrocnemius/soleus activity. The foot has limited stiffness modulation capacity, which reduces the effectiveness of balance responses.

Shortened muscles: pectoralis major/minor, rectus abdominis, hamstrings, sternocleidomastoid, suboccipitals.

Elongated muscles: thoracic erector spinae, trapezius (middle/lower), rhomboids, iliopsoas, lumbar erector spinae, transversus abdominis, multifidus, longus colli/capitis, gluteus maximus/medius, gastrocnemius/soleus [

28]. Clinically, the following symptoms predominate: thoracic stiffness, cervical and lumbar overloads, limited central stabilisation and ineffective balance reactions [

46].

This posture type is characterised by increased thoracic kyphosis accompanied by normal lumbar lordosis (

Figure 8). It occurs in approximately 4% of subjects [

8]. This pattern demonstrates the dominance of global flexion patterns in the upper trunk, with weakened segmental thoracic control and central stabilisation. It is characterised by excessive thoracic kyphosis with preserved lumbar lordosis. Excessive thoracic flexion results from predominance of the pectoralis major/minor and weakness of the posterior thoracic muscles, including the thoracic erector spinae, middle/lower trapezius and rhomboids. Increased kyphosis limits the rotational mobility of the thorax and impairs trunk adjustment responses in the sagittal and transverse planes. In the cervical spine, head protraction and compensatory upper neck extension are observed in response to anterior trunk shift. The dominance of the sternocleidomastoid and suboccipital muscles with weakened longus colli/capitis disrupts head-trunk integration and reduces the precision of balance responses. In the lumbar-pelvic segment, lordosis remains normal, but local stabilizers (transversus abdominis, multifidus) exhibit reduced activity. This leads to a decrease in the quality of segmental control and limits the ability to stabilise the lumbar spine during weight-bearing tasks. The gluteus maximus and medius muscles are weakened, reducing hip stability in the frontal plane and affecting adjustment responses. A tendency towards neutral or slight flexion is noted in the hips, resulting from trunk compensation for excessive kyphosis. In the knees, slight flexion strategies predominate, constituting passive stabilisation with limited proximal control. A posterior shift in centre of gravity promotes foot supination and reduced activity of the gastrocnemius/soleus. The foot exhibits limited stiffness modulation, which hinders stance phase adaptation and compromises balance responses.

Shortened muscles: pectoralis major/minor, sternocleidomastoid, suboccipitals.

Elongated muscles: thoracic erector spinae, trapezius (middle/lower), rhomboids, longus colli/capitis, gluteus maximus/medius, transversus abdominis, multifidus, gastrocnemius/soleus. Clinically, flexed upper trunk posture, cervical overload, limited thoracic mobility and reduced balance response efficiency are predominant.

This pattern clearly demonstrates the dominance of global muscles over those segmental, leading to dissociation of trunk function and limited ability for precise postural control. This occurs in approximately 7% of subjects [

8]. It is characterised by simultaneous deepening of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis, reflecting a clear dissociation of trunk function: dominance of global flexion patterns in the thoracic spine and global extension patterns in the lumbar spine, with reduced integration of segmental stabilisers (

Figure 9). Excessive kyphosis results from predominance of the pectoralis major/minor and a weakening of the posterior thoracic band (thoracic erector spinae, middle/lower trapezius, rhomboids), which limits trunk rotation and worsens adjustment reactions. In the cervical spine, head protraction and compensatory upper neck extension are observed. The global muscles controlling head position remain dominant—sternocleidomastoid and suboccipitals—while the segmental stabilisers (longus colli/capitis) are hypoactive. This results in impaired head-trunk integration and causes reduced balance accuracy. In the lumbar-pelvic region, increased lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt reflect the predominance of the global hip extensors and flexors (iliopsoas, rectus femoris, lumbar erector spinae) over the segmental muscles of central stabilisation (transversus abdominis, multifidus). This pattern increases extension stiffness and reduces the ability to exercise local segmental control. Weakness of the gluteus maximus and medius further reduces hip stability and impairs balance responses in the lower limb. The hips are dominated by extension, which overloads the anterior compartment of the joint and limits the range of functional flexion. Hyperextension is common in the knees, a passive stabilisation strategy used when proximal control is ineffective. Anterior shifting of centre of gravity causes increased forefoot loading and foot pronation, which activates the global calf muscles (gastrocnemius, soleus) and posterior tibialis in a compensatory function. The foot loses its ability to precisely modulate stiffness, reducing the effectiveness of balance responses and load adaptation.

Shortened muscles: pectoralis major/minor, sternocleidomastoid, suboccipitals, iliopsoas, rectus femoris, lumbar erector spinae, gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis posterior.

Elongated muscles: thoracic erector spinae, trapezius (middle/lower), rhomboids, longus col-li/capitis, transversus abdominis, multifidus, gluteus maximus/medius [

28]. Clinically, a pattern based on global tension, cervical and lumbar overloads, limited thoracic mobility and ineffective balance reactions of the loaded lower limbs are observed. This pattern reflects the dominance of global muscles over local stabilisers, which limits the effectiveness of postural control and predisposes to overloading in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine [

42].