1. Introduction

Marine ecotourism has been a new development strategy over the last ten years to balance economic growth, environmental conservation, and benefits to the coastal community. This is based on the community-based ecotourism paradigm, where local people are included and equitable benefits are redistributed (Snyman, 2017; Stronza & Gordillo, 2008). Marine ecotourism will promote environmental conservation and empower the local population (Rahman et al., 2022). Economic gains will be felt directly by the population in a just and equal way (Bax et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, the crucial factor in success is the ability of local communities to control the economic value chain of tourism (Kunjuraman, 2022; Scheyvens, 1999). Welfare inequalities in Indonesia also exist because market conditions, fluctuating demand, and economic domination by external actors have made abundant marine resources available, yet market access is limited (Groeneveld, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on tourism, as the national economy contracted by 2.1%, 14.1% of businesses suspended operations, and 11.6% reduced personnel. Hotel occupancy rates decreased to 28.07%, compared with 56.73% in 2020 and 2021, respectively, and the number of foreign arrivals to the country decreased by 75% in 2020 and 61.57% in 2021 (BPS-Indonesia Statistics Agency, 2021). The income of coastal communities that relied on tourism fell drastically. Numerous small, and medium enterprises (SMEs), such as tourism service providers, homestays, culinary, and handicraft manufacturers, were closed or shut down, putting local economies under pressure (Baghel, 2022; Kawulur et al., 2021).

Simultaneously, the digital transformation has turned into a productivity factor, a market growth driver, and a resiliency driver. Digital marketing, e-commerce, and cashless payments help to improve performance of SMEs because of its cost-efficiency, exposure, and customer relations (Radicic & Petković, 2023; Smith & Brown, 2020). Digitalization boosts empowerment by making market-related information more accessible, more effective in managing the organization, and more autonomous in decision-making (Barba-Sánchez et al., 2024). Online payment systems, reservation systems, and social media are digital channels which are used in tourism to assist the local providers to discover the tourists, reduce the information asymmetry, and access a wider market (Sigala, 2018; Zvaigzne et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the potential in the coastal regions has not been maximized because of the digital illiteracy, lack of infrastructure, and administrative obstacles (Apriani et al., 2023). The United Nations Development Program discovered that the digital ecosystem in North Minahasa is still skewed when it comes to infrastructures, literacy, and uptake, and, thus, digitalization is a challenge facing coastal SMEs (UNDP, 2024).

Though studies have explored the concepts of SME digitalization and marine ecotourism independently, most lack examination of their interrelation in enhancing coastal welfare (Mardianton et al., 2024; Marolt et al., 2025; Purnomo & Purwandari, 2025). The concept of digitalization in community-based marine tourism has not been studied in depth regarding its concurrent effects on empowerment and long-term well-being (Kurniawati et al., 2022). Though the literature identifies obstacles to the digital transformation of SMEs, the solutions offered are abstract and lack contextualization for the coastal sector (Amrullah et al., 2025; Rupeika-Apoga & Petrovska, 2022). Furthermore, no study has been explicitly examined the mediating role of local economic empowerment in linking SME digitalization and marine ecotourism to community welfare, as well as the moderating role of government support in strengthening this relationship.

The existence of the above-mentioned study proves a considerable level of mediating a sustainable tourism variable in the community empowerment (Khalid et al., 2019; Wani et al., 2024; Yang & Kim, 2023), but the government mediates the relationship between the use of technologies and performance of the SME (Kurniawan et al., 2023; Kyal et al., 2022; Seow et al., 2021). The measures presented in Indonesia have digitalized SMEs and empowered the coastal communities. It is not, however, being implemented effectively because of the structure, such as institutional coordination, poor infrastructure, and insufficient digital literacy (Nurlukman et al., 2025; Seow et al., 2021). The current literature is concentrated on modifying digital SME ecosystem models to the coastal location, where literacy levels are high, and infrastructure is well-developed (Aminullah et al., 2024). There is still a significant barrier in the digital divide of urban and coastal SMEs, which inhibits inclusive growth (Morris et al., 2022; Richmond et al., 2017).

The paper addresses the gaps by providing an integrative model of marine ecotourism (ME) and SME digitalization (SD) to improve the welfare of the local community (LCW), through SME empowerment (SE) and mediated by government support (GS). The novelty of the model is that it explores the causal relationships that explain how and in what condition these drivers lead to improvement of community welfare. As an example, North Minahasa can be applicable to the practical application of empirical evidence in repeating it in other related areas of the coast. The research will contribute to the body of knowledge of digital economy, community-based ecotourism and empowerment through an integrative structure approach. Practically, the results can inform the sustainable coastal development policy, as they can develop SME empowerment measures, improve connectivity, and establish synergistic governments. So, this research aims to investigate local economic empowerment’s mediating role in MSME digitalization and marine ecotourism’s influence on coastal community welfare, and government support’s moderating role in these relationships in North Minahasa.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoritical Foundation

Community-based ME development inherently creates demand for local goods and services, ranging from accommodation and culinary products to tour guiding (Phelan et al., 2020). The direct involvement of the community in this tourism value chain provides them with access to productive resources and opportunities to participate in decision-making, which is the main point of economic empowerment (Citra, 2017), (Amrullah et al., 2025). Other studies have found that sustainable tourism development has a significant positive impact on community empowerment (Wani et al., 2024) and can enhance economic indicators such as employment, growth, and income (Y. Chen et al., 2023), (Manzoor et al., 2019). Therefore, the hypothesis is formulated as follows: H1: ME has a positive and significant effect on SE.

Digitalization enables MSMEs to overcome geographical barriers, access wider markets, and improve operational efficiency (Purnomo et al., 2024). When coastal MSMEs adopt digital technology, they acquire new skills (digital marketing, online financial management) and access to previously unattainable information resources. This increases their capacity and independence, which are key elements of economic empowerment (Aminullah et al., 2024). Other studies have shown that digital platform-based empowerment of SMEs can strengthen the economic independence of coastal communities (Doktoralina et al., 2025), (Purnomo & Purwandari, 2025). Thus, the second hypothesis is: H2: SD has a positive and significant effect on SE.

2.2. Marine Ecotourism, Digitalization, and Coastal Community Welfare

Marine ecotourism is conceptually viewed as a sustainable tourism development strategy that integrates coastal environmental conservation with local community empowerment through the active participation of local communities in destination management, enabling economic benefits to be directly experienced by local residents (Masud, 2017). A study found a strong and significant correlation between the level of marine ecotourism development and the level of local community welfare (Sausan et al., 2023). Similarly, another finding has indicated that the presence of ecotourism in an area has a positive impact on the socio-economic life of the surrounding population, especially when managed properly (Tuasikal, 2020; Yanuar, 2017). A case study in the border region of Kalimantan (Sajingan Besar) showed that the utilization of waterfall ecotourism potential has successfully absorbed the poor local workforce and reduced regional isolation through infrastructure improvements, while also increasing village community income (Erusani & Fitriasari, 2022). Therefore, the following hypothesis can be formulated: H3: ME has a positive and significant impact on LCW.

The digitalization of SMEs has been proven to boost income and local economic growth. Internet access and e-commerce in rural areas have a positive impact on household economic welfare (Erusani & Fitriasari, 2022). The adoption of digital technology in rural ecotourism directly contributes to improving community welfare (Ji & Deng, 2025). Direct marketing to consumers through an online platform allows for higher income that can be used to improve quality of life, such as on health and education (Prasetyo & Kamil, 2023; Purnomo et al., 2024). A study in China found that internet use among rural households significantly increased household income and expenditure (Ma et al., 2020). Similar studies found that rural e-commerce development programs have significantly improved the income and welfare of rural residents in poor areas of China (Wen et al., 2024). Digitalization opens up access for rural SMEs to broader markets and more efficient supply chains, allowing local products to be sold at competitive prices and in larger volumes. This stimulates the village economy through multiplier effects: increased MSME turnover, local labor absorption, and higher household income (Royani et al., 2025). Therefore, the hypothesis is H4: SD has a positive and significant effect on LCW.

SLA views that household or community welfare as an outcome of strengthening livelihood assets (human, social, natural, physical, and financial capital) built through local economic activities. These frameworks emphasize that when access and capabilities on those five capitals are improved through local-based economic strategies, then livelihood outcomes (including income, resilience, and quality of life) also improve (Natarajan et al., 2022). In the tourism and rural context, local economic empowerment can ensure that economic benefits are more effectively captured at the community level. Cross-study findings show a consistent positive relationship between empowerment (local economy) and the achievement of sustainable community development (Khalid et al., 2019). In Indonesia, quantitative studies on Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDes) program found that strengthening village economic institutions was positively and significantly associated with village development progress, as measured by the Village Development Index (IDM). In addition, it also encouraged local job creation; both of which directly contribute to improving village household welfare (Ultari, 2024). Studies on rural-based tourism emphasize that when local economic activities (production, services, marketing) grow and are linked to tourism demand, there is a real improvement in community welfare indicators (Utomo et al., 2020). In line with this, the asset-based, sustainable local economic development approach demonstrates that interventions leveraging asset-based capacity and local uniqueness are more effective in improving quality of life, as they strengthen the endogenous economic-social foundations of the community (Kammer-Kerwick et al., 2022). Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is H5: SE has a positive and significant effect on LCW.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Local Economic Empowerment

In Community Empowerment Theory (CET), the impact of external interventions (such as tourism development on community welfare often does not occur directly, but rather through the empowerment process in the first place (Perkins; & Zimmerman, 1995). ME provides economic opportunities, however, these opportunities can only be transformed into sustainable welfare when local communities are empowered to capture and manage them (Khalid et al., 2019). Without empowerment, economic benefits may only be enjoyed by external investors, while local communities remain marginalized (Wani et al., 2024). Based on this argument, a mediation hypothesis is formulated, H6: SE significantly mediates the effect of ME on LCW.

Similarly, the availability of digital technology does not necessarily guarantee improved welfare, as technology is merely a tool. Its benefits can only be maximized when the local communities are empowered to use it productively. The process of digital adoption drives improvements in skills, access to information, and business independence, all of which are at the core of economic empowerment (Martínez-Peláez et al., 2023). This empowerment process then becomes a bridge to transform technology access into increased income, social capital, and an improved quality of life. Without the empowerment process, technology may only be used for consumptive rather than productive purposes (Ritzer, 2015). Therefore, the mediation hypothesis is: H7: SE significantly mediates the effect of SD on LCW.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Government Support

According to Institutional Theory, the institutional environment can strengthen or weaken the relationships among variables within a system (Chu et al., 2018). Government support (GS) acts as an institutional catalyst. The positive influence of ME and SD on SE is expected to be stronger when GS is active. Government-led digital training programs can accelerate the empowerment process driven by technology adoption(Chu et al., 2018). Pro-community tourism zoning policies ensure that the benefits of tourism are genuinely experienced by local communities, thus strengthening empowerment (Kyal et al., 2022). Conversely, when GS is weak or absent, the ecotourism development effort and digitalization at the grassroots level may progress slowly and be less effective in empowering the community (Kurniawan et al., 2023). Therefore, a moderation hypothesis is formulated, H8: GS positively moderates the influence of ME and SD on LCW.

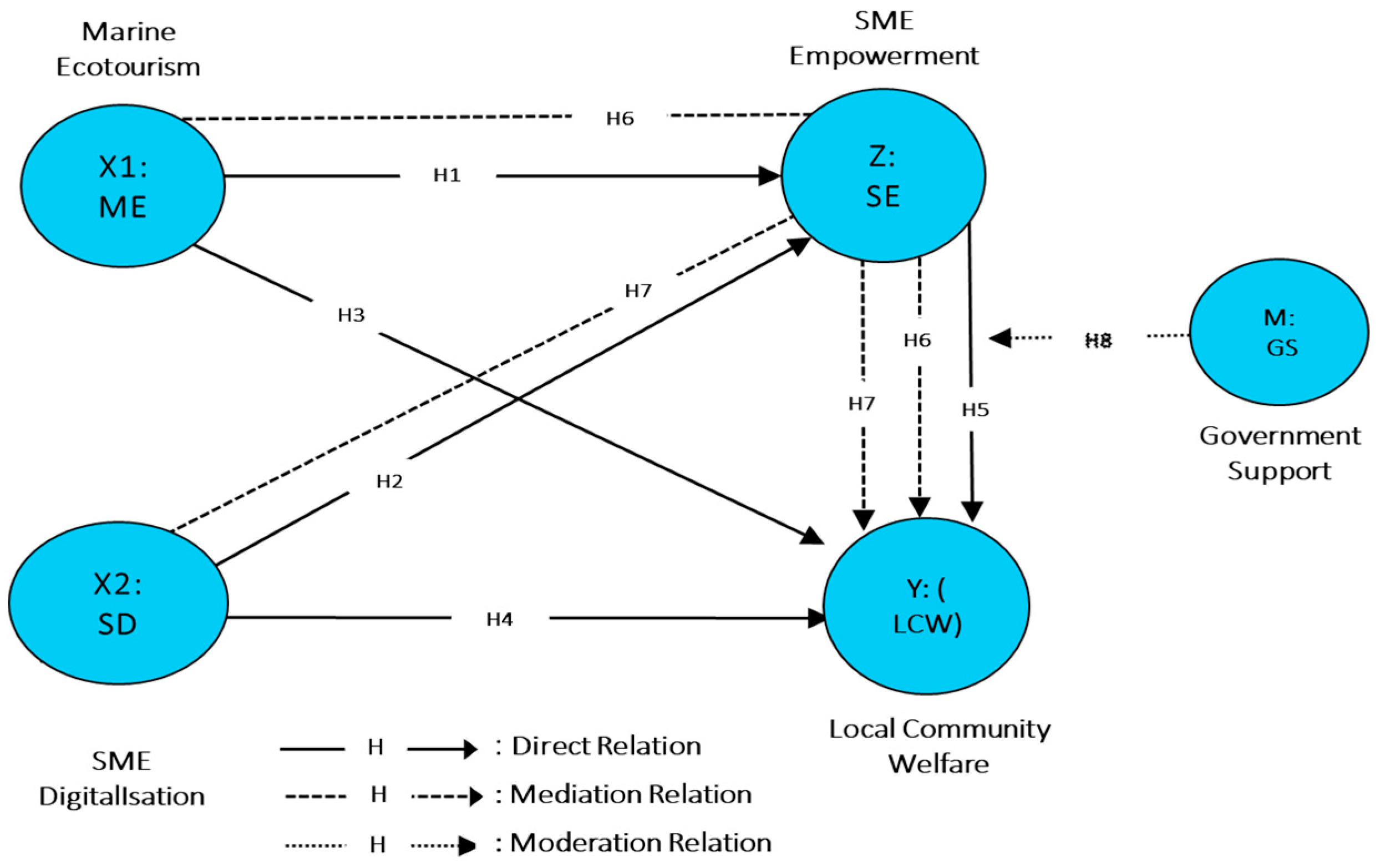

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Setting

This study employed a quantitative approach with an explanatory cross-sectional survey design to examine the influence and causal relationship among the variables specified in the conceptual model.

The study was conducted in Budo Ecotourism, Budo village, North Minahasa Regency, North Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. As a marine tourism village, Budo is also known as an alternative gateway to the famous Bunaken Marine Park. This is due to its location facing a group of islands such as Bunaken, Siladen, Mantehage, and Nain, which can be reached in approximately 30 minutes by boat. Covering an area of approximately 423 hectares, the village is largely comprised of mangrove ecosystems that dominate its coastal landscape.

3.2. Population and Sample

The research population comprised coastal MSME owners and marine tourism entrepreneurs in North Minahasa Regency, North Sulawesi. The research sample consisted of 312 respondents selected using purposive sampling. The selection criteria included: (1) MSME owners or founders operating in coastal areas and involved in the marine tourism value chain (such as tourism service providers, homestays, local cuisine, and souvenir crafts); and (2) have been running their business for at least 2 years to ensure sufficient experience. This approach was selected due to the limitations of a formal sampling framework and the need to ensure that respondents possessed relevant knowledge aligned with the study’s context. The sample size was 10 times the number of indicators (27 indicators x 10 = 270). The questionnaire was distributed to 400 respondents across Budo village and neighboring coastal villages, and 312 valid responses were collected. Since the questionnaire distribution area represents a leading ecotourism destination, the sample reflects the diverse conditions of MSMEs and marine tourism in North Minahasa.

3.3. Instrument and Data Collection Method

The research instrument was in the form of structured questionnaires developed based on a literature review on key variables. Each latent variable was operationalized into a set of questions or statements (indicators) measured on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 being “Strongly Disagree” to 5 being “Strongly Agree”. The questionnaires consisted of five main parts according to its variable: (1) Marine Ecotourism, (2) MSME Digitalization and Innovation, (3) Local Economic Empowerment, (4) Local Community Welfare, and (5) Government Support. Each question was adapted from conceptual definitions and indicators from previous research (

Table 1), then adjusted for the North Minahasa local setting. Prior to distribution, the content validity was reviewed by three experts (academics and tourism/MSME practitioners) to ensure that the questions accurately represented the measured construct and were easily understood by respondents. After minor revisions to the wording based on experts’ feedback, the final questionnaires were then used for the main data collection.

All variables were measured as reflective constructs using a 1–5 Likert scale. Each respondent’s score for a variable was the average of the indicator scores. A higher score meant that the respondent’s evaluation of the construct was more positive/strong. The table above summarizes the definitions and operationalization of variables according to the literature review, which formed the basis for the development of this research survey instrument. All indicators were phrased positively; where a high level of agreement indicated a more desirable condition (e.g., the higher the agreement that “household income has increased,” the higher the perceived welfare). The validity and reliability of the measurement of each variable were assessed prior to final data analysis, as discussed in the methods section.

Data were collected using a field survey method. The research team, assisted by local enumerators, visited coastal villages and marine tourism centers in North Minahasa. Questionnaires were personally handed to selected respondents and completed through structured interviews (to ensure a high response rate and clear understanding of the questions). This face-to-face approach also minimized non-response and allowed for immediate clarification if respondents had difficulty in understanding certain statements. All respondents provided informed consent before participating and were guaranteed confidentiality regarding their identity and business information.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data obtained from the questionnaire was analyzed quantitatively using Structural Equation Modeling–Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) with SmartPLS version 4. This approach was selected because allows the analysis of complex structural models involving latent variables and multiple indicators, and does not require normal distribution assumption. The PLS-SEM method was also selected for its predictive-oriented nature and robustness for medium sample sizes. In addition, this method has the ability to avoid identification problems that often arise in Covariance-Based SEM when the model includes numerous latent variables and indicators. SEM-PLS analysis was conducted in three stages:

-

Outer Model (Measurement Model) Evaluation

This stage aimed to ensure that the instruments accurately measure the intended constructs. Testing was carried out through: Convergent validity, with an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value ≥ 0.5; Construct reliability, using Composite Reliability (CR ≥ 0.7) and Cronbach’s Alpha (≥ 0.6); and Discriminant validity, to ensure that each construct is unique and different from one another, assessed through the HTMT ratio (< 0.90) and the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

-

Inner Model (Structural Model) Evaluation

Once the measurement model was declared valid and reliable, the relationships between latent variables in the structural model were tested. This testing included included: R-square (R²) to see how well the independent variables explain the dependent variables; f square (f²) to assess the magnitude of the effect between variables; and

-

Significance Test (Path coefficients)

Significance test as well as hypothesis testing were conducted using the bootstrapping technique with 5,000 subsamples to obtain t-statistics values. Significance was determined at α = 0.05 and t > 1.96.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Sample Profile

The sample consisted of 312 marine tourism entrepreneurs operating in the Budo village area and its surroundings regions with quotas determined based on the population framework covering accommodation, trade/food stalls, and MSME’s (

Table 2).

Table 2 presents the demographic profile. Female entrepreneurs played a central role in entrepreneurship, slightly more dominant than their men counterparts. In terms of owner age, most business owners fell between 30 and 65 yo (years old). Regarding business age, most have been operated for more than five years, reflecting a combination of established and new entrepreneurs. Regarding monthly income, most respondents reported earnings ranging from IDR 3 million to 7.5 million per month. This figure suggests that businesses are still dominated by micro-small scale, with relatively good resilience (many having operated for more than five years) but ample room for income growth remains.

Digital devices are merely used as tools for communication, marketing, and simple transactions. The majority of entrepreneurs (73%) utilize internet access for promotion, delivery, and reservations. In contrast, computers or laptops were only used by 27% of the respondents, generally for bookkeeping or more complex online store management purposes. This pattern indicates that the basic digital foundation has been established (smartphones and internet access), however, advanced digital capabilities are still limited by device costs, skills, and connectivity quality.

4.2. Pilot Test

Based on the pilot test involving 30 respondents, most instrument items were found to be valid and the construct formed were reliable. Of the initial 27 items, 25 items were retained while 2 were eliminated. The ME construct retained all 5 items, SD retained 6 items, and SE retained 5 items (all valid, α > 0.7). Two items from the LCW construct were eliminated (LCW5 and LCW6, invalid, α < 0.7). After revision, all constructs met the validity criteria (r > 0.30) and reliability criteria (α > 0.70). This indicates that the revised instrument possessed good measurement quality and was suitable for further analysis.

4.3. Outer Model Assessment

4.3.1. Construct Loading

Table 3 presents the outer loading values for each indicator in the ME, SD, SE, LCW, and GS constructs. According to the measurement standard, an outer loading value of ≥0.70 is considered ideal and indicates a valid or high-quality indicator for measuring the construct. Thus, all indicators across the five constructs meet the convergent validity requirements. All indicators have values above 0.7, indicating very strong loadings and sufficient statistical contribution in measuring each construct.

4.3.2. Composite Reliability and Discriminant Validity

As shown in

Table 4, the research instrument is confirmed to be both reliable and valid. All constructs have Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability above 0.7 with Average Variance Extracted (AVE) > 0.50. This means that internal consistency and convergent validity are fulfilled.

Discriminant validity was also confirmed, as the AVE root value of each construct was greater than the inter-construct correlations (Fornell-Larcker criteria), and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) values were below the threshold of 0.90 (

Table 5). Overall, the measurement instruments used in this study met all the required critical parameters and demonstrated excellent measurement quality, and thus it is deemed valid and reliable. Therefore, the tested model is trustworthy for further structural analysis.

4.4. Structural Model

4.4.1. Collinearity Evaluation

All constructs in

Table 6 show VIF values < 5 for all indicators. Thus, no collinearity issues were detected.

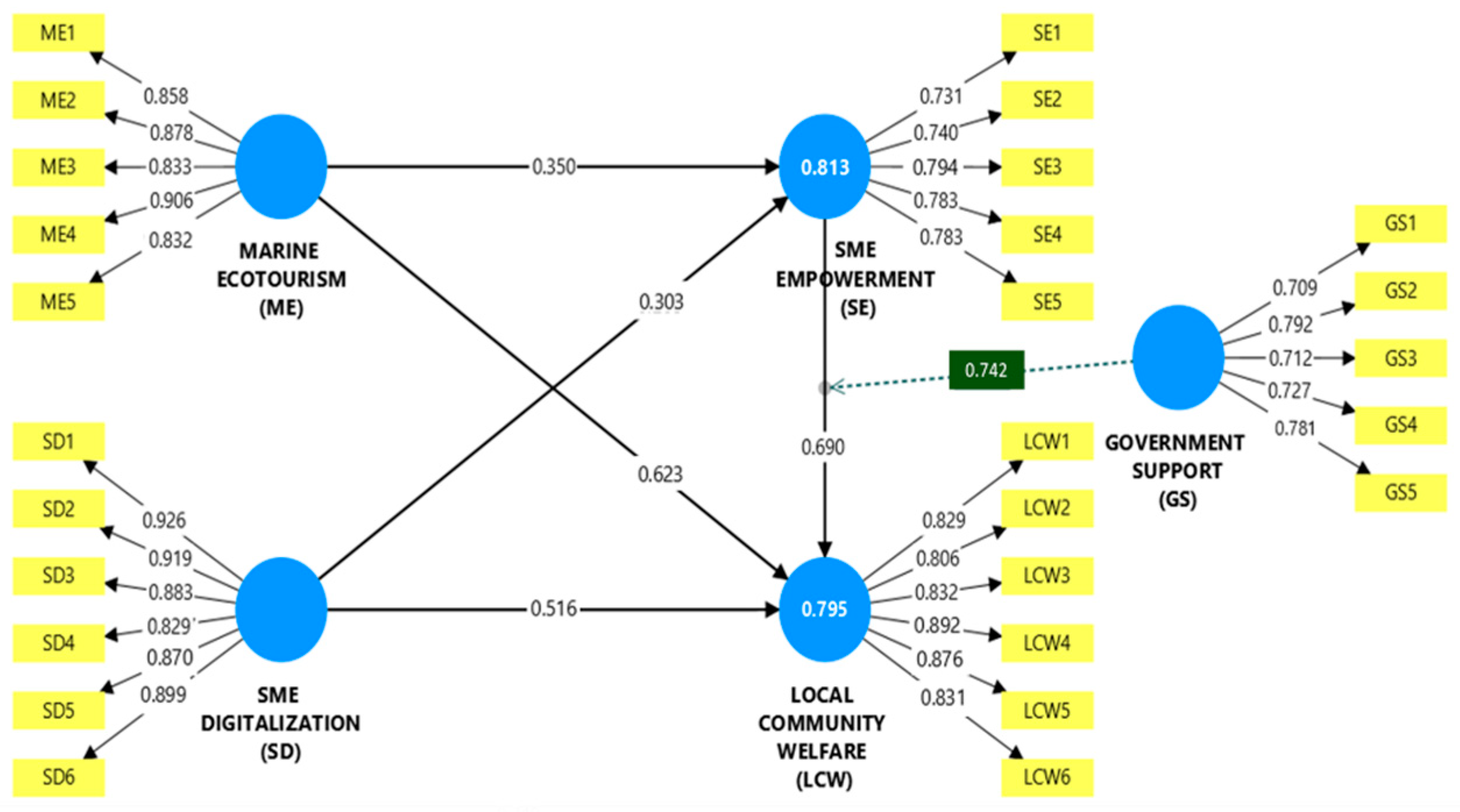

4.4.2. R-Square and f-Square

The overall model demonstrated a high R-square for the endogenous variables SE of 0.813 and LCW of 0.795 (

Table 7), indicating that 79.5%–81.3% of the variance is explained by the model.

Based on Cohen’s f² effect size guidelines, the relationships among constructs in this model showed moderate to large effect sizes. No effects fall within the small category, as all f² values were ≥ 0.18 (

Table 8).

4.4.3. Model Fit

The SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) indicator was used to evaluate the overall model fit. The SRMR values for both the saturated and estimated models were 0.046. An SRMR value below 0.08 indicates a good fit, meaning that the discrepancy between the empirical covariance and the model covariance is very small. This indicates that the model structure is consistent with the observed data (e.g., there is no significant misspecification).

4.4.4. Hypotheses Test

Direct Path. The bootstrapping method was used to calculate the

t and

p values of the path coefficients. The results of the direct path analysis through bootstrapping tested the significance of hypotheses H1–H7. In general,

Table 9 shows that most of the direct relationships between variables are significant in accordance with the predicted direction of influence. However, H3 and H4 were found to be insignificant (Unsupported).

Indirect Path. The mediating effect of SE in indirect relationships (H6 and H7) showed that both results have significant indirect effect on LCW via SE (

Table 10). This confirms that SE acts as a significant mediator connecting the exogenous variables (ME and SD) with the endogenous variable LCW.

Moderator Effect. The moderation effect test in Table 11 indicate that GS plays a significant role in strengthening the relationship between SE on LCW. The path coefficient value of 0.479 for the GS × SE → LCW relationship with t-statistics values > 1.96 and p-values < 0.05, indicates a statistically significant relationship.

Figure 2.

Empirical model of the relationship between ME and SD on LCW with SE Mediation and GS Moderation role.

Figure 2.

Empirical model of the relationship between ME and SD on LCW with SE Mediation and GS Moderation role.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal the relationship pattern between ME, SD, SE, and LCW. In general, the findings support the hypothesis that ME and SD can increase LCW, however, this impact occurs mainly through the SE mechanism. In other words, SE acts as a crucial bridge that transforms digitalization and ecotourism initiatives into improved community welfare. These findings are consistent with the CET (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995) and SLA (Anani, 1999; S. Chen et al., 2021) frameworks, which emphasize that the benefits of development programs will be sustainable only when local communities have the capacity and control to capture these economic opportunities. In addition, GS was found to strengthen these relationships, in line with Institutional Theory (Scott, 2013), which highlights the role of the institutional environment in influencing the effectiveness of development innovations.

ME was found to significantly increase SE (

Table 9). This implies that the participation of coastal SMEs in ME in North Minahasa has strengthened their capacity, skills, and involvement in local economic activities. This aligns with CET’s view that active participation in local initiatives increases community control and independence. It also supports studies showing that sustainable tourism development has a positive impact on local community empowerment (Wani et al., 2024). Similarly, community involvement in the ecotourism value chains (such as providing homestays, culinary services, and tour guiding) offers access to productive resources and economic decision-making opportunities, which are central to empowerment (Citra, 2017; Phelan et al., 2020). In the context of Budo, the presence of marine ecotourism has fostered skill transfer (e.g., dive guiding training or homestay management training) and expanded networks (through interaction with tourists and industry players). This in turn increases local residents’ confidence and business capacity. This corresponds with the concepts of psychological and economic empowerment, where ecotourism can empower communities when they are fully involved in planning and receive direct economic benefits(Scheyvens, 1999). Therefore, this finding (H1 supported) reinforces the theoretical foundation that community-based ecotourism can act as a catalyst for local economic empowerment, a key prerequisite for sustainable coastal development.

The test results for H2 confirm that SD has a significant positive effect on SE (

Table 9). The adoption of digital technology by Budo ecotourism businesses on the coast of North Minahasa has been proven to improve their skills and capacity, such as online marketing capabilities, market information access, and operational efficiency. By utilizing the internet, e-commerce, and social media, local SMEs have been able to overcome geographical barriers and expand their market reach. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that the use of digital platforms increases the economic independence of coastal communities through increased knowledge and business networks (Doktoralina et al., 2025),(Purnomo & Purwandari, 2025). From the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) perspective, the success of digitalization in empowering local SMEs indicates that entrepreneurs are willing to adopt technology because they perceive its usefulness (e.g., increased sales, cost savings) and find the technology relatively easy to use in their daily operations. According to TAM theory (Davis, 1989), this perceived usefulness drives actual technology usage and ultimately leads to positive outcomes. In other words, in coastal areas that were previously digitally marginalized, digitalization now acts as a “new enabler” – providing SMEs greater access to knowledge and autonomy in managing their businesses. This expands the digital inclusion literature by providing empirical evidence that digital transformation can improve empowerment among marginalized communities, provided that the local contexts support technology adoption.

Consistent with the theoretical expectations of SLA and CET, this study found a strong positive relationship between SE and LCW (H5 supported). Higher empowerment was reflected by improved skills, capital access, market access, and local business independence, followed by an increase in community household welfare (measured by income, education, health, etc.). This finding aligns with the SLA framework, in which strengthening the five livelihood capitals (human, social, financial, physical, natural) through local economic activities leads to improved livelihood outcomes such as income and quality of life. This is supported by previous studies that report a consistent positive relationship between community empowerment and the achievement of sustainable community development(Khalid et al., 2019). A study in Indonesia found that strengthening village economic institutions (e.g., BUMDes) is significantly associated with an increase in the Village Development Index and local job creation(Ultari, 2024). With H5 confirmed, it can be concluded that local economic empowerment is a key factor that independently leverages coastal community welfare. Theoretically, this reinforces CET with quantitative evidence that when communities possess greater capabilities and control over their economic resources, they can improve their own standard of living. In the coastal context, this emphasizes the importance of investing in local capacity building—such as entrepreneurship training, microfinance access, and community organization—as strategies for improving welfare without over-reliance on external actors.

Regarding the direct influence of ME and SD on welfare, hypotheses H3 and H4 were not found to be significant. This indicates that in this model, ME and SD do not directly show a significant influence on the coastal community welfare. This finding contrasts with many previous studies that generally report a direct positive impact. A previous study found a strong correlation between the level of marine ecotourism development and community welfare (Sausan et al., 2023), and rural e-commerce programs in China successfully increased household income and welfare of poor villagers (Wen et al., 2024). However, in this study, such direct effects were not statistically significant. This difference can be explained by reviewing the contextual conditions and mediation processes. From the CET perspective, marine ecotourism in Budo does not automatically improve welfare because most of its benefits are still captured by external parties or a small group of actors; with limited local involvement. When local communities are not fully involved in the ownership and management of ecotourism, much of the tourism revenue flows out to external actors and are not reflected in household welfare. Without empowerment, local communities may remain marginalized even as tourism grows (Wani et al., 2024). This reflects the situation in North Minahasa, where Likupang-Budo ecotourism area is growing, yet financial benefits may not be evenly distributed to local residents. Similarly, H4 was not significant, suggesting that adopting technology alone does not automatically improve welfare if it is not accompanied by sufficient utilization capacity. Technology is merely a tool; its economic impact can be materialized only when utilized effectively by skilled human resources. In this study, infrastructure and digital literacy constraints likely act as barriers. The UNDP (2024) report on the Likupang destination reveals that the digital ecosystem in North Minahasa remains uneven in terms of internet connectivity, infrastructure support, and user capabilities. As a result, digital transformation, which should have been an accelerator of growth, has instead become a new challenge for coastal SMEs. This explains why digitalization has not yet had a direct impact on welfare: SMEs may have started to go digital, but the scale and quality of its utilization are insufficient to increase household income. Another factor to consider is time and the learning curve. The economic impact of digitalization may take longer to materialize, whereas this survey is cross-sectional and captures only a single point in time. The nonsignificant direct effects of ME and SD emphasize an important argument: without empowerment and institutional support, the potential benefits of tourism and technology may not be realized for local communities. Thus, this study provides a new nuance to the literature: while supporting previous findings on the positive potential of ecotourism and digitalization, it also underlines the critical conditions required for these potentials to be truly realized into real improvements in community welfare.

The mediation analysis results support the role of local economic empowerment as a key mediating variable. Although H3 and H4 (direct effects) were not significant, the mediation hypotheses H6 and H7 were supported: both marine ecotourism and SME digitalization have a significant positive impact on welfare through empowerment. In other words, ME and SD indirectly improved coastal welfare, with empowerment acting as a mechanism for transmitting benefits. This mechanism aligns with the logic of Community Empowerment Theory (Perkins; & Zimmerman, 1995), which states that external interventions will only change welfare if the local community is first empowered. Empowerment to be a significant mediator in the relationship between development programs and community quality of life, particularly in the sustainable tourism sector (Khalid et al., 2019; Yang & Kim, 2023). The confirmation of H6 and H7 in this study provides the latest empirical support for this argument. In North Minahasa, it appears that the presence of ecotourism and digital technology results in improved welfare only when the community acquires the skills required to seize the opportunities. For example, Budo ecotourism can increase local income if residents are trained to manage homestays or guide tourists, and digital platforms can raise business revenues if SMEs are confident to market their products online. These mediation findings align with the study in India, which demonstrated that the impact of tourism projects on residents’ income is weak without the mediation of citizen capacity building (Wani et al., 2024). From an SLA perspective, this also implies that ecotourism and digitalization strengthen human and social capital assets (through knowledge, networks, confidence) and financial capital (through market access), which then drive livelihood outcomes in the form of welfare. In terms of theoretical implications, this study emphasizes the importance of incorporating empowerment variables into development program evaluation models. Focusing solely on direct effects may obscure the underlying processes; as shown here, local empowerment is the essential component that transforms program inputs into tangible benefits for communities.

One of the results of this research is that Government Support (GS) has a significant positive moderating effect on the interaction between SME Empowerment (SE) and Local Community Welfare (LCW). The outcome aligns with the Institutional Theory (Scott, 2013) that will be applied in this research, in which formal institutional aspects, including government policies and programs, establish an enabling environment that governs the consequences of organizational and community-level behaviors. Our observation indicates that GS does not constitute a background phenomenon solely, but rather a dynamical institutional driver (Kurniawan et al., 2023). Even though SME empowerment is a vital determinant of welfare, its impact depends on the institutional context. This makes Kurniawan et al. argument even more significant, as the authors highlight the importance of government facilitation for SME development. This is elaborated in our study, which demonstrates the operation of this facilitation: the enhancement of the translation of empowerment into in-roofed welfare benefits.

Moreover, this result offers a more detailed outlook than the earlier studies. For example, unlike a research assumed that poor institutional backing prevents grassroots efforts (Kyal et al., 2022), our research empirically shows that strong institutional backing is an effective amplifier. Empowering local SMEs (a bottom-up process) has been best achieved when a conducive top-down institutional environment accompanies it. This synergy is crucial. For example, government digital training programs, as noted by Chu et al. (2018), can help already empowered SMEs better embrace digital tools and, consequently, increase their income and, in turn, community well-being. Equally, zoning pro-community tourism policies, as proposed by Kyal et al. (2022), would ensure that external forces do not erode the economic yields generated by empowered tourism SMEs.

In terms of novelty and scientific contribution, this study successfully addresses a literature gap by integrating two strategic domains—SME digitalization and marine ecotourism—into a single empirical framework. Previous studies have tended to examine the role of digitalization and ecotourism separately, while this research presents a holistic understanding of how the two synergize to improve coastal welfare through empowerment. Another novelty lies in the explicit testing of the mediating role of local empowerment and the moderating role of government support. To date, there has been little research testing similar models, particularly within the Indonesian coastal community contexts. Thus, these findings enrich the theory of community empowerment and sustainable development.

This study empirically confirms that local economic empowerment is the key mechanism determining whether digitalization and tourism initiatives succeed in improving welfare. It also confirms the importance of institutional context by demonstrating the catalytic effect of government support within community development models. Beyond its theoretical contributions, this study also offers significant practical implications.

For policymakers in North Minahasa and other coastal areas, these results imply that SME digital transformation and ecotourism development efforts should be designed in parallel with local empowerment and capacity-building programs. For example, providing digital marketing training for MSME actors, involving communities in destination management, and ensuring that tourism policies are inclusive for local residents. Without such integrated strategies, digitalization and tourism may fail to achieve their ultimate goal of equitable welfare improvement. Conversely, with appropriate empowerment and institutional support, SME digitalization and marine ecotourism can serve as effective levers for coastal welfare, as evidenced by this study.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that the synergy between MSME digitalization and marine ecotourism development holds great potential for improving the welfare of coastal communities. However, this effect does not occur directly; it is transmitted through local economic empowerment and strengthened by effective government support. Empirical findings indicate that the digitalization of small businesses and ecotourism activities in North Minahasa contribute significantly to increasing community capacity in terms of skills, market access, and economic independence. Accordingly, local economic empowerment serves as a key element that transforms technology- and tourism-based initiatives into tangible benefits for coastal community welfare.

This study extends the understanding of the CET and the SLA by providing empirical evidence that community welfare is not solely determined by the presence of economic opportunities (such as tourism or digitalization), but rather by local capacity to seize those opportunities. Meanwhile, the moderating effect of government support strengthens the validity of Institutional Theory, confirming that policies, infrastructure, and public training serve as an enabling environment that determines the success of the empowerment process. The practical implication is that effective coastal development strategies should integrate digital innovation, sustainable ecotourism development, and community-based empowerment programs into a single integrated policy model.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design of this study does not capture dynamic changes over time. Future longitudinal studies could be employed to assess how the impacts of digitalization and empowerment gradually evolve toward welfare. Second, this study focuses on a single district (North Minahasa), which has distinctive social and economic characteristics; therefore, generalizing the results to other coastal regions should be done with caution. Further research involving cross-regional comparisons (comparative studies) is recommended to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the varying impacts across regions.

Author Contributions

E.N.W.: Conceptualisation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. A.L.C.P.L.: Conceptualisation, Visualisation, Supervision. Y.M.: Data Curation, Supervision, Resources. D.S.I.S.: Methodology, Software, Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI, LPPM, grant number 203/UN12.13/LT/2023 and “The APC was funded by UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI, LPPM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Institute for Research and Community Service, Sam Ratulangi University with protocol code: 21/54 (survey), and 22/15 (FGD).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives, the voluntary nature of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. To ensure confidentiality, all data were anonymized, and no personally identifiable information was collected.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to confidentiality agreements with the participating organization and to protect the privacy of the research participants. Requests for access to the dataset can be directed to the Institute for Research and Community Service, Sam Ratulangi University, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis, subject to a data-sharing agreement and approval from the participating organization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Rector of UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI for funding this research through the RTUU 2023 scheme. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Chat GPT and Scopus AI for the purposes of literature search, summarization, improve language and readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.:

Abbreviations

| ME |

Marine Ecotourism |

| SD |

SME’s Digitalization |

| SE |

SME Empowerment |

| LCW |

Local Community Welfare |

| GS |

Government Support |

| SLA |

Sustainable Livelihoods Approach |

| CET |

Community Empowerment Theory |

| TAM |

Technology Acceptance Model |

References

- Aminullah, E., Fizzanty, T., Nawawi, N., Suryanto, J., Pranata, N., Maulana, I., Ariyani, L., Wicaksono, A., Suardi, I., Azis, N. L. L., & Budiatri, A. P. (2024). Interactive Components of Digital MSMEs Ecosystem for Inclusive Digital Economy in Indonesia. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 487–517. [CrossRef]

- Amrullah, A., Adi Junaidi, M., & Walid Sugandi, Y. B. (2025). Community Empowerment Strategies in Developing Sustainable Marine Tourism at Kahona Beach. JMET: Journal of Management Entrepreneurship and Tourism, 3(2), 236–249. [CrossRef]

- Anani, K. (1999). Sustainable governance of livelihoods in rural Africa: A place-based response to globalism in Africa. Development (Basingstoke), 42(2), 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Apriani, R., Putra, P. S., Muzayanah, F. N., & Avionita, V. (2023). Obstacles Advancing Msmes in Indonesia’s Coastal Areas to Support Economic Growth in the Digital Era. International Conference on Business, Accounting, Banking, and Economics (ICBABE 2022), 349–357. [CrossRef]

- Baghel, D. (2022). Resilience of MSMEs during the pandemic. In International handbook of disaster research (pp. 1–14). Springer.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Meseguer-Martínez, A., Gouveia-Rodrigues, R., & Raposo, M. L. (2024). Effects of digital transformation on firm performance: The role of IT capabilities and digital orientation. Heliyon, 10(6). [CrossRef]

- Bax, N., Novaglio, C., Maxwell, K. H., Meyers, K., McCann, J., Jennings, S., Frusher, S., Fulton, E. A., Nursey-Bray, M., Fischer, M., Anderson, K., Layton, C., Emad, G. R., Alexander, K. A., Rousseau, Y., Lunn, Z., & Carter, C. G. (2022). Ocean resource use: building the coastal blue economy. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 32(1), 189–207. [CrossRef]

- BPS-Indonesia Statistics Agency. (2021). Analisis Hasil Survei Dampak COVID-19 terhadap Pelaku Usaha (Analysis of COVID-19 Impact Survey Results on Business Actors). BPS.

- Chen, S., Sun, X., & Su, S. (2021). A study of the mechanism of community participation in resilient governance of national parks: With wuyishan national park as a case. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(18). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhang, J., & Chen, H. (2023). An economic analysis of sustainable tourism development in China. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(4), 2227–2242. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z., Xu, J., Lai, F., & Collins, B. J. (2018). Institutional theory and environmental pressures: The moderating effect of market uncertainty on innovation and firm performance. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 65(3), 392–403. [CrossRef]

- Citra, I. P. A. (2017). Strategi Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Untuk Pengembangan Ekowisata Wilayah Pesisir Di Kabupaten Buleleng. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial Dan Humaniora, 6(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Doktoralina, C. M., Abdullah, M. A. F., Febrian, W. D., & Maulana, D. (2025). Empowering Coastal SMEs: A Digital Transformation Model to Enhance Competitiveness and Sustainability. Quality - Access to Success, 26(206), 422–427. [CrossRef]

- Erusani, S., & Fitriasari, E. T. (2022). Ecotourism Development to Grow the Social Economy and the Welfare of Local Communities in the Indonesia-Malaysia Border Region. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 8(4), 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, R. A. (2020). Welfare economics and wicked problems in coastal and marine governance. Marine Policy, 117, 103945. [CrossRef]

- Ji, X., & Deng, B. (2025). Digital Technology Driving Sustainable Development in Rural Ecotourism. Economics \& Management Review, 6(1).

- Kammer-Kerwick, M., Takasaki, K., Kellison, J. B., & Sternberg, J. (2022). Asset-Based, Sustainable Local Economic Development: Using Community Participation to Improve Quality of Life. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17, 3023–3047. [CrossRef]

- Kawulur, A. F., Mawitjere, N., & Kawulur, H. (2021). Business competitiveness of small medium enterprise in pandemic era Covid-19 (Case study on souvenir business in the special economic area of tourism Likupang, North Sulawesi Province, Indonesia). Journal of International Conference Proceedings, 4(1), 173–178.

- Khalid, S., Ahmad, M. S., Ramayah, T., Hwang, J., & Kim, I. (2019). Community empowerment and sustainable tourism development: The mediating role of community support for tourism. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(22). [CrossRef]

- Kunjuraman, V. (2022). Community-based ecotourism managing to fuel community empowerment? An evidence from Malaysian Borneo. Tourism Recreation Research, 47(4), 384–399. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, Maulana, A., & Iskandar, Y. (2023). The Effect of Technology Adaptation and Government Financial Support on Sustainable Performance of MSMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cogent Business and Management, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, E., Kohar, U. H. A., Meiji, N. H. P., Handayati, P., & Ilies, D. C. (2022). Digital Transformation for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises to Develop Sustainable Community-Based Marine Tourism. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 11(3), 1118–1127. [CrossRef]

- Kyal, H., Mandal, A., Kujur, F., & Guha, S. (2022). Individual entrepreneurial orientation on MSME’s performance: the mediating effect of employee motivation and the moderating effect of government intervention. IIM Ranchi Journal of Management Studies, 1(1), 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W., Nie, P., Zhang, P., & Renwick, A. (2020). Impact of Internet use on economic well-being of rural households: Evidence from China. Review of Development Economics, 24(2), 503–523. [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Asif, M., & Zia, M. (2019). The Contribution of Sustainable Tourism to Economic Growth and Employment in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3785), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Mardianton, M., Amar, S., & Irianto, A. (2024). Empowering Mangrove Ecotourism: Integrating Governance, Community, and Technology for Sustainable Coastal Development. Journal of Ecohumanism, 3(8), 3153–3167. [CrossRef]

- Marolt, M., Lenart, G., Kljajić Borštnar, M., & Pucihar, A. (2025). Exploring Digital Transformation Journey Among Micro, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Systems, 13(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Peláez, R., Ochoa-Brust, A., Rivera, S., Félix, V. G., Ostos, R., Brito, H., Félix, R. A., & Mena, L. J. (2023). Role of Digital Transformation for Achieving Sustainability: Mediated Role of Stakeholders, Key Capabilities, and Technology. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(14). [CrossRef]

- Masud, M. M. (2017). Community-based ecotourism management for sustainable development of marine protected areas in Malaysia. Ocean and Coastal Management, 136, 104–112. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J., Morris, W., & Bowen, R. (2022). Implications of the digital divide on rural SME resilience. Journal of Rural Studies, 89(November 2020), 369–377. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N., Newsham, A., Rigg, J., & Suhardiman, D. (2022). A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Development, 155, 105898. [CrossRef]

- Nurlukman, A. D., Fadli, Y., & Wahyono, E. (2025). Ecotourism for coastal slum alleviation: A strategic approach to achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Tangerang, Indonesia. Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review, 5(2), e02793--e02793. [CrossRef]

- Perkins;, D. D., & Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Empowerment Theory, Research, and Application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. D., & Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A., Ruhanen, L., & Mair, J. (2020). Ecosystem services approach for community-based ecotourism: towards an equitable and sustainable blue economy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1665–1685. [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, A. S., & Kamil, A. (2023). Digitalisasi UMKM pada Sektor Pariwisata Laut Pesisir Utara Madura di Masa Pandemi Covid-19. Competence: Journal of Management Studies, 17(2), 24–40. [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, S., Nurmalitasari, N., & Nurchim, N. (2024). Digital transformation of MSMEs in Indonesia: A systematic literature review. Journal of Management and Digital Business, 4(2), 301–312. [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, S., & Purwandari, S. (2025). A Comprehensive Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprise Empowerment Model for Developing Sustainable Tourism Villages in Rural Communities: A Perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland), 17(4). [CrossRef]

- Radicic, D., & Petković, S. (2023). Impact of digitalization on technological innovations in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 191(December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. K., Masud, M. M., Akhtar, R., & Hossain, M. M. (2022). Impact of community participation on sustainable development of marine protected areas: Assessment of ecotourism development. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(1), 33–43.

- Richmond, W., Rader, S., & Lanier, C. (2017). The “digital divide” for rural small businesses. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 19(2), 94–104. [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G. (2015). Automating prosumption: The decline of the prosumer and the rise of the prosuming machines. Journal of Consumer Culture, 15(3), 407–424. [CrossRef]

- Royani, N., Mitasari, D., Masitoh, G., & Fitri, T. I. (2025). Analisis dampak digitalisasi umkm terhadap pertumbuhan ekonomi lokal di indonesia. Jurnal Sharia Economica, 4(2), 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R., & Petrovska, K. (2022). Barriers to sustainable digital transformation in micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises. Sustainability, 14(20), 13558. [CrossRef]

- Sausan, M. F., Indriana, H., & Purwandari, H. (2023). Pengembangan Ekowisata Bahari dan Kesejahteraan Masyarakat Lokal pada Masa Pandemi Covid-19 The Development of Marine Ecotourism and The Local Communities Walfare during the Covid-19 Pandemi. Jurnal Sains Komunikasi Dan Pengembangan Masyarakat, 07(01), 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. (1999). Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management, 20(2), 245–249. [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Sage publications.

- Seow, A. N., Choong, Y. O., & Ramayah, T. (2021). Small and medium-size enterprises’ business performance in tourism industry: the mediating role of innovative practice and moderating role of government support. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 29(2), 283–303. [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2018). Implementing social customer relationship management: A process framework and implications in tourism and hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(7), 2698–2726. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., & Brown, A. (2020). Digital transformation in SMEs: A systematic literature review. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(3), 321–338.

- Snyman, S. L. (2017). The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in southern Africa. In Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Principles and impacts in developing countries (p. 22). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A., & Gordillo, J. (2008). Community views of ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 448–468. [CrossRef]

- Tuasikal, T. (2020). Strategi pengembangan ekowisata pantai Nitanghahai di desa Morela, kabupaten Maluku Tengah. Jurnal Agrohut, 11(1), 33–42.

- Ultari, T. (2024). The Role of Village-Owned Enterprises ( BUMDes ) in Village Development: Empirical Evidence from Villages in Indonesia. The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning, VIII(2), 256–280. [CrossRef]

- UNDP. (2024). Indonesia Digital Ecosystem Assesment 2024. 1–47. https://www.undp.org/indonesia/publications/study-report-indonesia-digital-ecosystem-assessment-2024.

- Utomo, S. H., Wulandari, D., Narmaditya, B. S., Ishak, S., Prayitno, P. H., Sahid, S., & Qodri, L. A. (2020). Rural-based tourism and local economic development: evidence from Indonesia. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 31(3), 1161--1165. [CrossRef]

- Wani, M. D., Dada, Z. A., & Shah, S. A. (2024). The impact of community empowerment on sustainable tourism development and the mediation effect of local support: a structural equation Modeling approach. Community Development, 55(1), 50–66. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H., Qiu, A., & Huang, Y. (2024). Impact of e-commerce development on rural income: Evidence from counties in revolutionary old areas of China. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 35(2), 345–367. [CrossRef]

- Yang, E., & Kim, J. (2023). Sustainable tourism development in a host community: The mediating role of community resilience in response to disasters and crises. International Journal of Tourism Research, 25(5), 527–541. [CrossRef]

- Yanuar, V. (2017). Ekowisata berbasis masyarakat wisata alam pantai Kubu (Community Based Ecotourism Nature The Kubu Beach). Ziraa’ah, 42(3), 183–192. https://ppj.uniska-bjm.ac.id/?p=3193.

- Zvaigzne, A., Mietule, I., Kotane, I., Sprudzane, S., & Bartkute-Norkuniene, V. (2023). Digital innovations in tourism: the perceptions of stakeholders. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 15(5), 528–537. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).