1. Introduction

Financial markets are greatly affected by monetary policy, especially through changes in the Fed’s funds rate. Interest rate cuts help lower capital costs, boost business investment, and stimulate consumer spending, all of which, taken together, help to boost equity market values. Bernanke and Blinder [

1] and Taylor [

2] discussed how changes in interest rates are transmitted to the real economy, which in turn affects financial markets and asset prices, from theoretical and empirical perspectives, respectively. Furthermore, Bernanke and Kuttner [

3] empirically demonstrated that reductions in interest rates correlate with substantial positive responses in the stock market, principally via mechanisms such as equity risk premium compression and alterations in investor mood. While the impact of monetary policy on equity markets is well-documented, less is known about how different mutual fund investment types, including value funds and growth funds, react to these policy changes. By nature, growth funds invest in companies with great future profit potential; therefore, their values are quite sensitive to variations in the discount rate used for far future cash flows. Estep [

4] used the Break-Even Time (BET) concept to show that high price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio stocks, which are usually high-growth companies, have a present value that is especially sensitive to changes in interest rates. In contrast, value stocks grounded in near-term earnings and stable dividends demonstrate greater resilience to such shifts, making them less sensitive to interest rate changes.

The concept of equity duration may explain this asymmetric sensitivity, since growth stocks can be viewed as longer-duration assets than value stocks [

5]. Growth and value funds differ in their asset composition, cash flow profiles, and sensitivity to monetary policy shocks. Growth funds primarily invest in companies with higher expected earnings growth rates, as their value is primarily derived from cash flows over a longer period. Therefore, these funds are more sensitive to changes in discount rates [

6]. This interest rate sensitivity comes from the discounted cash flow (DCF) model. In contrast, value funds invest in companies with stable earnings and undervalued fundamentals. Lower discount rates have less of an impact on value stocks, as their valuations are more dependent on short-term cash flows. Consequently, growth funds are more affected by interest rate cuts, while value funds react more moderately.

While this theoretical difference is commonly recognized, few empirical studies systematically examine the performance of different fund styles under real monetary shocks. Literature reviews reveal a lack of in-depth analysis of how mutual stock funds with distinct investment styles (e.g., growth funds and value funds) respond to interest rate changes. Previous research has largely focused on stock indices and bond markets, lacking empirical studies at the fund level that consider both raw and risk-adjusted returns over different periods. In addition, many studies neglect the fund’s response over time and typically do not use dynamic risk-adjusted performance measures.

We bridge these gaps by systematically investigating how the U.S. Federal Reserve’s interest rate cuts during the 2019–2020 easing cycle affected the performance of value and growth funds with different investment styles in equity mutual funds. The 2019 to 2020 interest rate cut cycle is worth studying because it occurred on the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, when interest rates were low and valuations were high. Unlike typical recession easing, this cycle involved proactive measures that were not driven by a crisis. This provides a unique opportunity to study how policy affects asset valuations. Applying an event study methodology, we analyze and compare the abnormal returns (AR) and cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) over the 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year preceding and following three critical policy events. In addition to raw returns, we also incorporate static and dynamic risk-adjusted measures, such as Sharpe ratio (SR), Jensen’s alpha (α), volatility, and beta (β) coefficients, with particular emphasis on their 30-day rolling versions to reflect fund dynamics under different periods and market changes. These rolling measures (30-day window) capture the time-varying dynamics of funds’ response to policy shocks. Finally, a set of regression models within the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) framework is constructed to separate the impact of monetary policy on different fund styles and investment horizons, while controlling systematic market risk. These are rarely seen in mutual fund literature, but they help us understand how funds behave over time. This method allows us to tell the difference between temporary volatility and persistent performance trends following policy changes. More detailed information is included in the “Methodology” section.

This dual-focus approach helps to more clearly distinguish between fund responses to interest rate changes at the discount rate and the broader impact of market-level monetary easing policies. Based on the DCF theory, which implies growth-oriented assets are interest-rate-elastic due to their reliance on future earnings, this analysis examines the extent to which such theoretical expectations manifest as enduring disparities in realized performance. Therefore, this study fills a gap in existing literature that seldom controls time-varying responses at the fund level or uses dynamic measures of performance. The findings offer empirical insights into transmission mechanisms of monetary policy at the fund level and contribute to portfolio strategy, fund risk management, and the broader understanding of how monetary policy shapes asset performance across different investment styles.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Hypotheses

This study aims to clarify the following key hypotheses based on the above objectives:

Hypothesis 1: Growth funds are more sensitive and experience a larger performance boost than value funds in response to interest rate cuts.

Hypothesis 2: The positive impact of rate cuts on equity fund performance is more pronounced in a shorter term (30-day event window) but gradually diminishes over longer time windows (6 months and 1 year).

Hypothesis 3: Reducing interest rates corresponds to notable increments in risk-adjusted performance, especially for funds that emphasize growth, as indicated by increasing SR and α.

The following section constructs a theoretical framework for the interplay between monetary policy, asset pricing, and mutual fund performance. The study uses classical asset valuation theory, modern asset pricing models, and well-established performance evaluation metrics to assess the differential impact of interest rate changes on value and growth equity mutual funds.

3.2. Asset Valuation and Discounting

The fundamental principle of asset valuation is that the present value of any financial asset is determined based on the discounted sum of its expected future cash flows. The basic present value model is expressed as:

Where is the present value of the asset, is denotes the expected cash flow at time t, and r represents the discount rate.

The discount rate consists of two main components: risk-free rate and risk premium, which balances market risk and uncertainty. U.S. Treasury yield typically represents the risk-free rate [

26]. A decline in interest rates directly reduces the risk-free component of the discount rate. Assuming expected cash flows remain unchanged, this leads to an increase in present value, thereby driving up asset prices. Thus, the sensitivity of asset prices to changes in interest rates depends on the duration of expected cash flows and the magnitude of the discount adjustment. Financial assets with longer-term cash flow durations have a higher valuation sensitivity to interest rate cuts [

27].

From this perspective, there is an inverse relationship between asset prices and interest rates. If interest rates fall even slightly, the present value of these long-term cash flows could rise substantially. This would boost the valuation of growth stocks and mutual funds. The Fed implements monetary policy in financial markets by adjusting interest rates [

3].

For mutual funds, the underlying securities they hold determine their net asset value (NAV). Therefore, the theoretical mechanism linking interest rates and asset prices directly influences the performance of mutual funds, especially those holding longer-term equity securities. However, an empirical question remains as to whether monetary easing (especially interest rate cuts) significantly improves the performance of value funds. Therefore, this study aims to empirically identify and quantify this differential effect during periods of Fed rate cuts.

3.3. Event Study Methodology

In empirical finance, the event study approach is a fundamental tool for assessing how policy or discrete economic events affect asset prices. It is based on the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), which assumes that markets can quickly incorporate new information into prices. In this framework, AR is the difference between the actual return and the expected return during the event window. The formula is as follows:

Where represents the AR of fund i on day t. represents the actual return of fund i at date t. represents the fund’s expected return at date t, usually using a benchmark model, such as the CAPM or a market model.

These differences increase over time, yielding the CAR, defined as:

Where and are the start and end of the event window. CAR calculates the overall abnormal impact of an event on fund i, while the sum of events aggregates the daily ARs within the window.

MacKinlay [

28] formalized this methodology and demonstrated its applicability to corporate, monetary, and political domains. This study utilizes the event window around interest rate cut announcements to assess the short-term and long-term responses of mutual funds. This method is particularly well-suited to monetary policy announcements because of their discrete nature, timeliness, and market volatility.

The event study framework can identify differences in fund performance that cannot be explained by general market volatility. We calculate the AR relative to the expected return of a CAPM-based benchmark model for each defined event window.

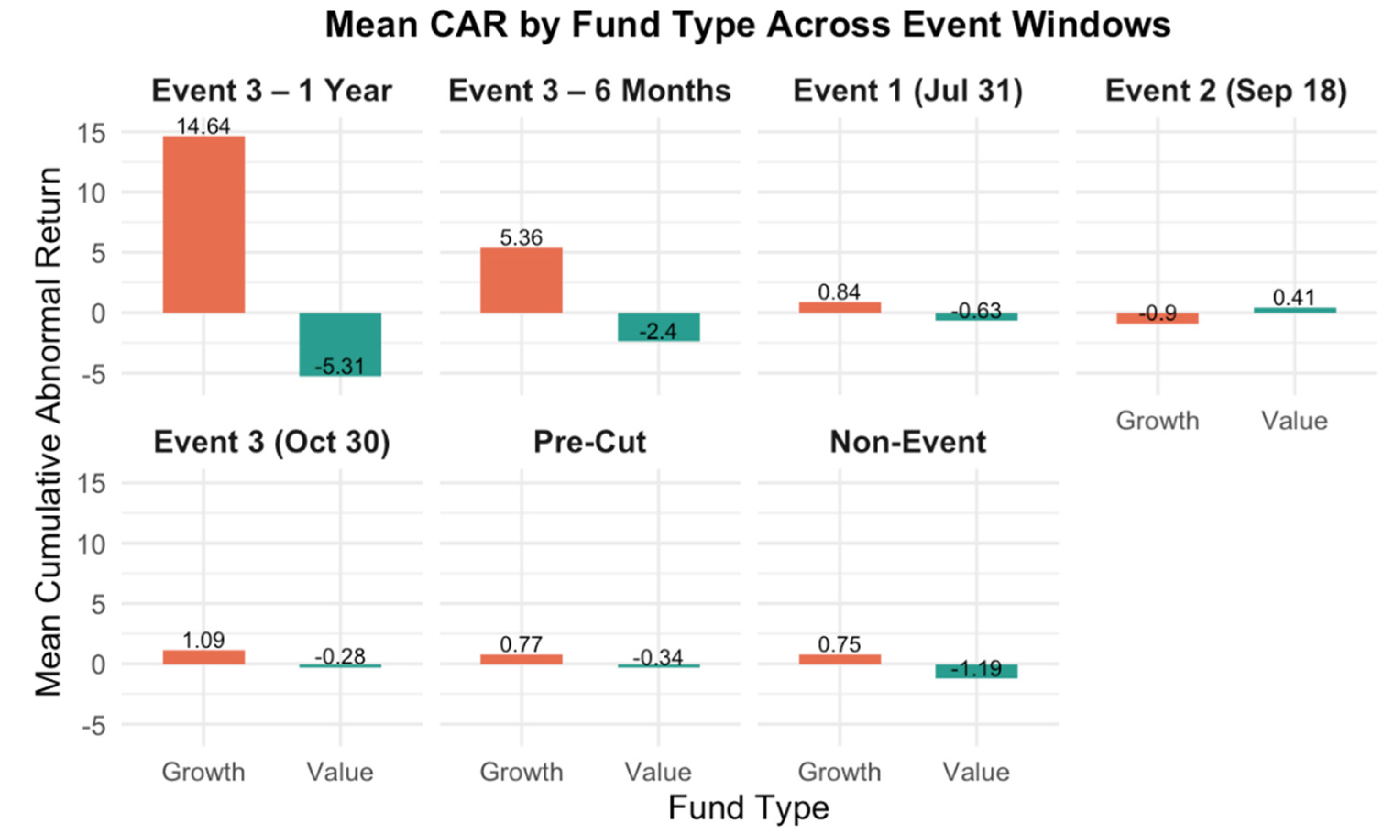

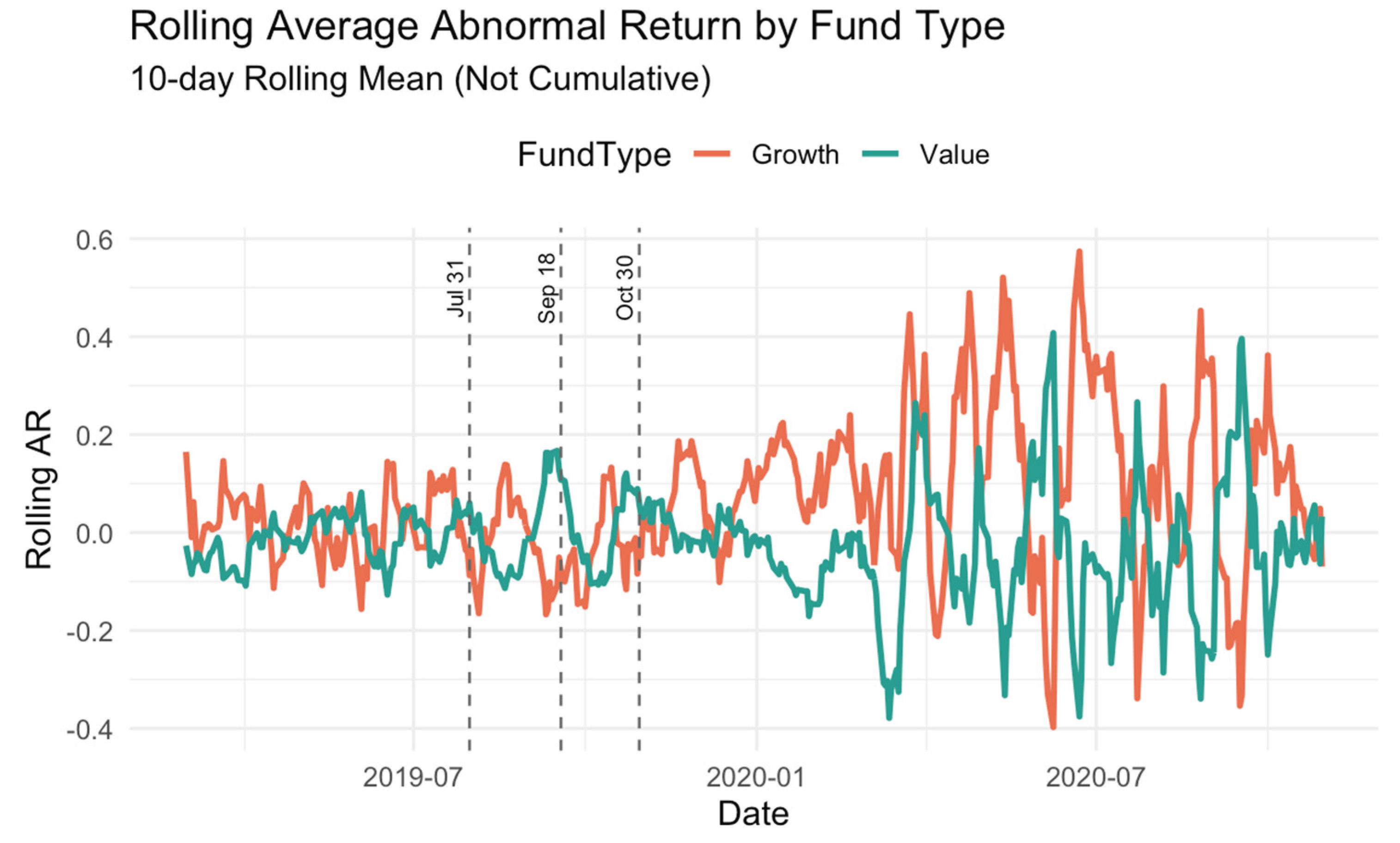

Appendix C Figure A3 shows the 10-day rolling average AR of growth and value mutual funds. Growth funds exhibit higher positive AR after 2020, indicating that value funds are more market-responsive than growth funds.

To measure the aggregate impact of policy announcements, we construct CARs for the three event windows surrounding the Fed’s rate cut. We use static β coefficients estimated based on full-sample regressions, especially for short-term event windows. This is because rolling estimates are noisy over a short period of time. We use rolling β better to identify time-varying market risk exposures over the long-term window. To test the benchmark, we also create a pre-interest rate cut window (July 1st -31st) and a non-event period that covers all dates except the event window. We consider the 30 days before the rate cut as a sub-window of the broader event window, i.e., the 30 days before the Fed decides to cut rates. In contrast to the non-event period, this window covers all time frames outside the defined event window. ANOVA and t-tests are then used to compare CARs across styles and periods, and to distinguish between differential effects. In addition, we combine ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions that incorporate style and period interactions. We estimate a pooled OLS model of CAR based on fund style, cycle indicators, and their interactions:

Where is CAR of the ith fund on day t within the ±30-day window; is a dummy variable for value funds (Value=1, Growth=0); and are indicator variables for non-event and event windows, respectively (Pre-Cut is the benchmark); measures the marginal difference of value funds relative to growth funds in each period.

To explore whether growth and value funds react differently to each rate cut, we estimate separate cross-sectional regressions of 30-day CAR on fund style for each event date

:

Where if fund i is value (0 if Growth).

To assess the persistence of the impact of monetary policy, we use dynamic AR with rolling β to calculate CARs for two long-term maturities following the October 30, 2019, rate cut: 6 months (as of April 30, 2020) and 1 year (as of October 30, 2020). Since events 1 and 2 occur after other policy adjustments, the long-run CAR may be disturbed. Therefore, the long-run regression analysis does not include the long-run CAR. For each horizon

, we estimate the cross-sectional model:

Where if fund i is value (0 if Growth).

Heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator, type 1 (HC1), for robustness checks, is used in all models. We perform a studentized Breusch-Pagan (BP) test (p < 0.001) on each model to validate heteroskedasticity. Therefore, the reported coefficients are all estimates under robust standard errors (SE).

We construct the following cross-sectional regression model to assess the difference in performance between growth and value funds after excluding market risk.

are the 30-day CARs obtained by accumulating the CAPM ARs. is the fund style indicator variable, which is taken as 1 for growth and 0 for value; can be taken in two ways: For the static β, which is CAPM β from a one-time regression of the full sample, another, the rolling β used CAPM regression with a rolling window of 30 or 60 days in the past to extract day-by-day β. Also, we do the robustness check with the HC1 method.

To test whether the style effect varies with a fund’s market sensitivity, we estimate cross-sectional interaction models of the following form:

Where is the 30-day CAR for fund i (static event windows). ∈ {0,1} equals 1 for Growth funds, 0 for Value. is the fund’s systematic risk exposure, measured both as Static CAPM beta over the full sample, and 30-day rolling CAPM beta, estimated via OLS in a moving window. The interaction term captures whether the style effect (growth vs. value) changes with market sensitivity. All models employ HC1-robust SEs to address heteroskedasticity, as confirmed by studentized BP tests.

3.4. Capital Asset Pricing Model

This study uses the CAPM as the underlying risk-adjustment framework to differentiate the impact of market-wide risk factors on fund performance. The CAPM assumes that the expected return of an asset is a linear function of its sensitivity to systematic market risk and is expressed as follows.

Where

is the expected return on asset i,

is the risk-free rate,

is the asset’s beta, and the

is the expected return on the market portfolio [

29].

In empirical applications, the CAPM framework provides a benchmark for measuring fund performance after adjusting for market risk exposure. The framework allows for rigorous tests of performance metrics to distinguish returns attributable to skill from those attributable to market changes [

30]. A fund’s alpha, representing the excess return over its beta-implied benchmark, serves as a measure of a fund manager’s ability or pricing efficiency [

15].

3.5. Risk-Adjusted Performance: Sharpe Ratio and Jensen’s Alpha

Risk-adjusted performance metrics allow for differences in volatility and market risk to be accounted for in performance comparisons. The SR and a are two common metrics. Sharpe [

14] proposed the SR to calculate the excess return per unit of risky investment. Its expression is:

Where is the fund’s average return, is the risk-free rate, and is the standard deviation (SD) of returns. The SR shows how well a fund compensates investors for their total risk (including systematic and idiosyncratic risk).

By contrast, a assesses the AR for exposure to systematic risk and is derived from the CAPM framework.

Where is a of asset, is realized return of asset, is risk-free rate, is beta of asset, and is realized return of the market.

A positive alpha indicates that a fund outperforms its risk-adjusted benchmark, implying that the fund manager has good exposure or superior management skills over the sample period [

15]. By integrating these two metrics, we can get a more complete picture of mutual fund performance. a evaluates whether returns are commensurate with market risk, and the SR measures risk-return efficiency. Both methods are particularly important during periods of monetary easing, when volatility and investor sentiment can fluctuate rapidly.

3.6. Rolling Performance Measures and Time-Varying Risk

Traditional performance assessment typically assumes constant risk exposure and constant return distribution. However, financial markets can exhibit abnormal volatility, heteroskedasticity, and changes in investor behavior when macroeconomic events such as interest rate changes occur [

31]. This study uses rolling window techniques of the SR, a, and β to capture these dynamics. Specifically:

The rolling SR expression is:

Where and are the mean and SD of returns over a rolling window up to time t.

Additionally, Christopherson et al. [

32] used rolling regression to identify changes in fund strategies. For the rolling a, the time-varying alpha can be represented by repeatedly estimating CAPM regression over rolling sub-periods, using the formula:

Where is the a of fund i at time t, represents the fund’s excess return adjusted for systematic risk. is fund’s i actual return at t, is risk-free rate of return at t, is the fund’s systematic exposure to the market estimated in the rolling window, is the actual return of the market at t; denotes the market risk premium.

Meanwhile, rolling β coefficients are analogous to rolling CAPM regressions to reflect changing market risk exposures. Ferson and Schadt [

33] introduced the methodology of time-varying β coefficients to assess conditional performance. Repeated regressions are conducted over a rolling window to estimate the sensitivity of each fund’s returns to changes in market returns. The expression is:

Where is the real rate of return earned by the fund p in time t, is the profitability of the market at time t, is the risk-free rate of return, usually using the current short-term Treasury rate. is denotes systematic risk exposure and excess market returns. is the rolling β coefficient at time t, which shows the fund’s dynamic sensitivity to market changes, is the rolling intercept term, which indicates the trend of excess return over the time window, and is the error term, which captures the unexplained part of the model.

By using rolling calculations over a 30-day window, this study provides a more detailed understanding of how fund risk and performance evolve in response to policy changes. Rolling calculations can better reveal risk exposure or short-term performance fluctuations than static metrics, which may miss or ignore these factors entirely.

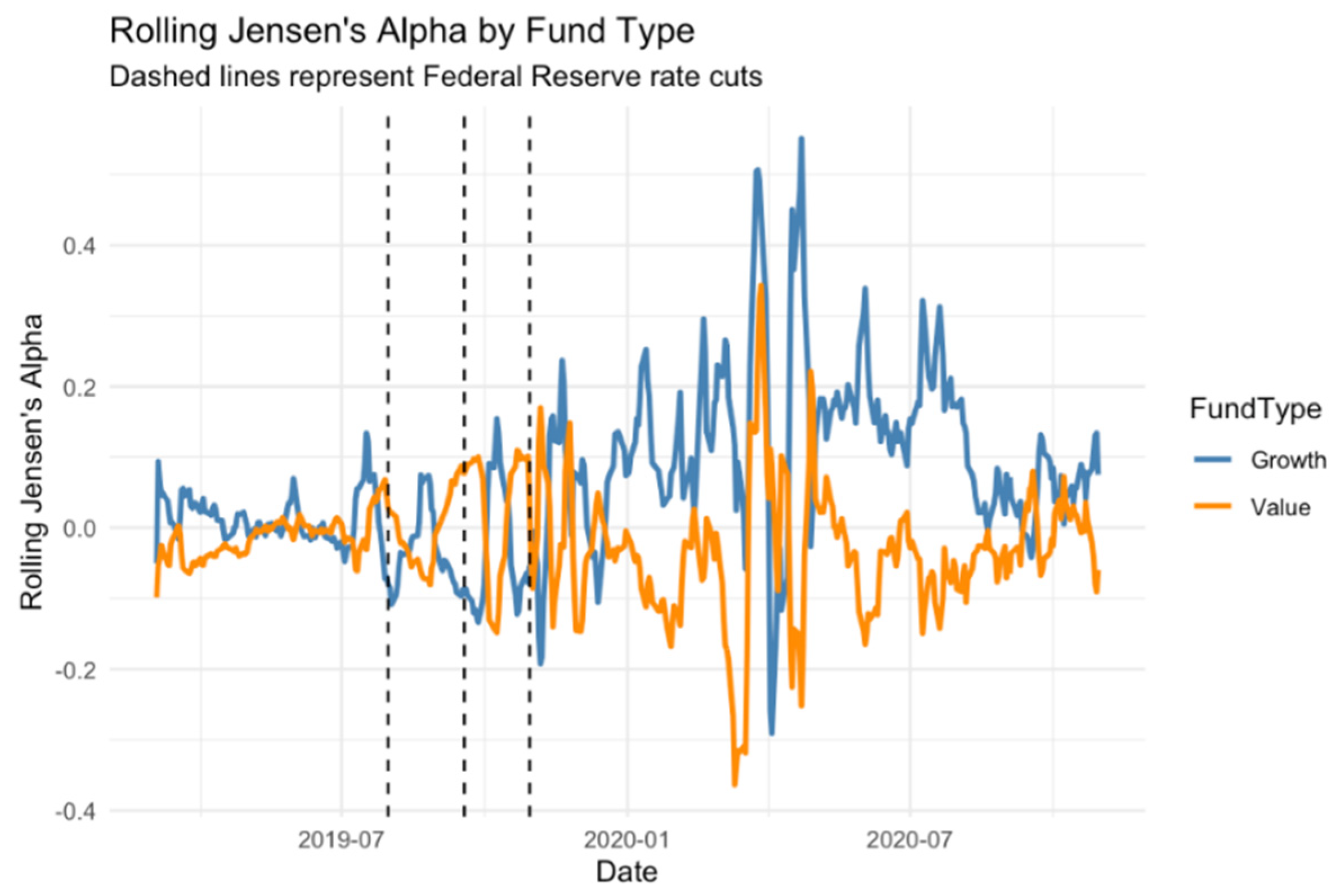

Therefore, this study uses rolling alphas and SRs to demonstrate the emergence and dissipation of the performance advantage of growth funds versus value funds under different monetary policy regimes. In addition, this is consistent with more econometric approaches that identify time-varying parametric models and conditional risk. This dynamic approach can also reveal whether, when, and how monetary easing affects fund returns and volatility.

3.7. Data Sources and Sample Selection

This study focuses on three consecutive rate cuts implemented by the Fed between March 2019 and October 2020 (July 31, September 18, and October 30, 2019). This time frame was chosen for four main reasons: (1) availability of high-frequency, high-quality mutual fund data suitable for both static and rolling measurements; (2) simplicity of a common easing cycle, which is separable from interventions triggered by crises; (3) occurrence at a time preceding extensive unconventional policies like quantitative easing, thus making it ideal for identifying rate cuts effects; (4) the presence of multiple, clustered events allows for robust event study design across repeated windows.

To assess the impact of the Fed’s rate cut on mutual fund performance, we select six well-known equity mutual funds and categorize them into growth and value funds. The growth funds include Vanguard Growth Index Fund Admiral Shares (VIGAX), Fidelity Growth Company Fund (FDGRX), and T. Rowe Price Blue Chip Growth Fund (TRBCX). These funds are more sensitive to economic stimulus measures such as interest rate cuts because of their emphasis on high expected earnings growth and large-cap allocations. In contrast, value funds include the Vanguard Value Index Fund Admiral Shares (VVIAX), Dodge & Cox Stock Fund (DODGX), and American Funds Washington Mutual Investors Fund (AWSHX). These funds focus on fundamentally driven pricing, stable dividends, and low valuations, and are therefore less sensitive to monetary policy shocks.

Daily adjusted closing prices and return series for all funds are obtained from Seeking Alpha [

34] with fund returns calculated using the log difference of adjusted prices to account for dividends and stock splits. For more information, see

Table 1.

Furthermore, we use the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) Volatility Index (VIX) and the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (SPX) as benchmarks to account for the overall market impact, sourced from Seeking Alpha [

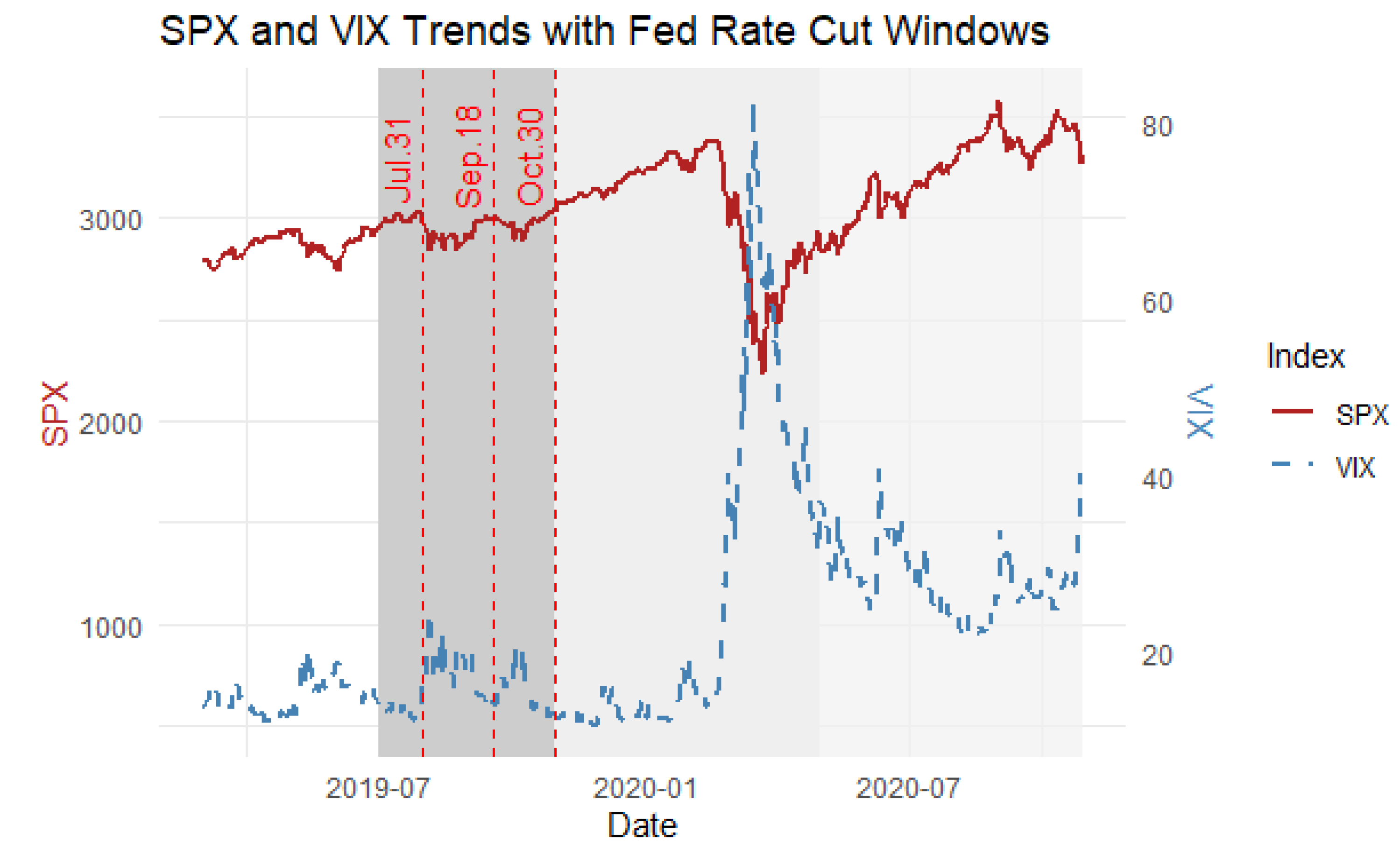

34], which helps contextualize mutual fund behavior within broader market dynamics. For trends in the benchmarks (SPX and VIX) during the study period, please refer to

Appendix C Figure A1, which illustrates that SPX remained relatively stable throughout the event window, while VIX was volatile thereafter, during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While NASDAQ [

35] provides broader market indicators, we use the Federal funds rate (FFUNDS) to represent the monetary policy stance. Unlike stock prices, FFUNDS does not exhibit daily percentage changes, as it reflects a fixed-income rate that adjusts infrequently. Studies analyzing the impact of interest rates on asset prices use first-order differences (∆ FFUNDS) rather than percentage returns [

3]. Our study computes first-order differences of FFUNDS to track monetary policy shifts. We calculate the required risk-free rate within a CAPM framework using the FRED database of 3-month Treasury Bill rates (TB3MS) [

36]. To ensure the continuity of the sample data, the monthly TB3MS series is populated using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) and linearly interpolated to daily frequencies. The final decimalized daily series is used for all risk-adjusted performance estimates.

This sample construction ensures that the funds selected are indexed, actively managed, or liquid, and fit each investment style. To ensure representativeness, comparability, and analytical robustness based on the event-based and risk-adjusted return analysis, the sample is designed using a balanced mix of fund styles, validated sources, and composite market benchmarks.

3.8. Time Window Definition

To systematically evaluate the impact of interest rate cuts on mutual fund performance, this study adopts a multi-perspective event study framework. This study defines both short-term and long-term windows to capture the immediate effects and persistent adjustments of monetary policy shocks across distinct fund styles. In addition, exploring these windows provides a clear understanding of whether the market reactions are concentrated around the announcement date or evolve gradually over time.

This study examines short-term impacts using symmetric event windows centered on each of the 2019 Fed rate cut announcements: July 31st, September 18th, and October 30th. For each event, we construct a window spanning [-30, +30] trading days around the event date.

For the short-term analysis, three symmetric event windows are constructed around the Fed’s 2019 rate cut announcements on July 31, September 18, and October 30, each spanning ±30 trading days. These windows capture pre-announcement anticipation and immediate post-announcement adjustments, aligning with standard event study methodology [

28]. AR and CAR are computed within these windows to quantify the direct valuation effects of rate cuts.

To explore the long-term effects, two extended post-event windows are defined using the final rate cut on October 30, 2019, as the anchor point: one from October 30, 2019 to April 30, 2020 (6 months), and another from October 30, 2019 to October 30, 2020 (1 year). These windows allow for analysis of performance persistence, particularly in terms of risk-adjusted measures such as SR and a. This approach also facilitates a comparison between short-term market reactions and long-term absorption of monetary easing, offering insights into the durability of style-specific fund performance.

This window structure allows for broader economic correlation and event-specific granularity. Long-term windows are used to examine variations in fund response patterns, while short-term windows are used to limit announcement effects. The use of multiple overlapping and non-overlapping windows enhances the reliability and credibility of empirical inferences.

3.9. Variable Construction

To put into practice the theoretical concepts and empirical models presented in the previous chapters, this study constructs a comprehensive set of variables to capture fund-level performance, risk exposure, and policy response dynamics. These variables are designed to support both event-based and risk-adjusted analysis.

The logarithmic difference of daily returns is calculated for each mutual fund after adjustment. Expected returns are derived using both static and dynamic approaches based on the CAPM framework. Static estimates are based on the full sample β coefficients, while dynamic estimates are based on 30-day rolling window regressions. These techniques enable time-varying estimates of β, alpha, and AR that adapt to changes in fund behavior and risk exposure over the policy cycle.

SRs and α are computed on a static and rolling basis, respectively, to quantify risk-adjusted performance. The SR on a 30-day rolling basis applies realized 30-day return volatility, and the rolling alpha is the intercept from a rolling CAPM regression. These rolling structures can be used for performance sensitivity analysis in a changing market environment. Event-related variables consist of multiple window dummies, each indicating whether the date is pre-event, post-event, or within the window. These factors allow for a direct assessment of the short-term and long-term impact of policies on fund outcomes.

Each variable is constructed using the R programming language. A complete dictionary of all 38 dataset variables, including the internal processing steps and code-based construction logic, can be found in the full list of variables and definitions in

Appendix A Table A1, while the key variable definitions in

Table 2 provide a summary of the core variables and their mathematical definitions.

3.10. Risk-Adjusted Performance Analysis

This study uses risk-adjusted metrics to assess the performance of mutual funds to complement the analysis of ARs. The SR measures average excess return per unit of total risk (SD), which is particularly sensitive to changes in volatility associated with policy events. In addition, a is derived from the CAPM framework, which separates the portion of a fund’s return that cannot be explained by market volatility and indicates the ability or strategic advantage of the fund manager in the event of a change in monetary policy. The expression is shown in

Table 2.

At the fund level, both metrics are estimated using two approaches: static estimation, which averages performance over the entire sample period, and rolling estimation using a 30-day moving window to observe changes in policy interventions. The rolling methodology is particularly well-suited to capturing short-term increases or decreases in performance associated with policy changes or macroeconomic uncertainty. These rolling statistics are calculated using consistent window lengths and are consistent across all funds and dates.

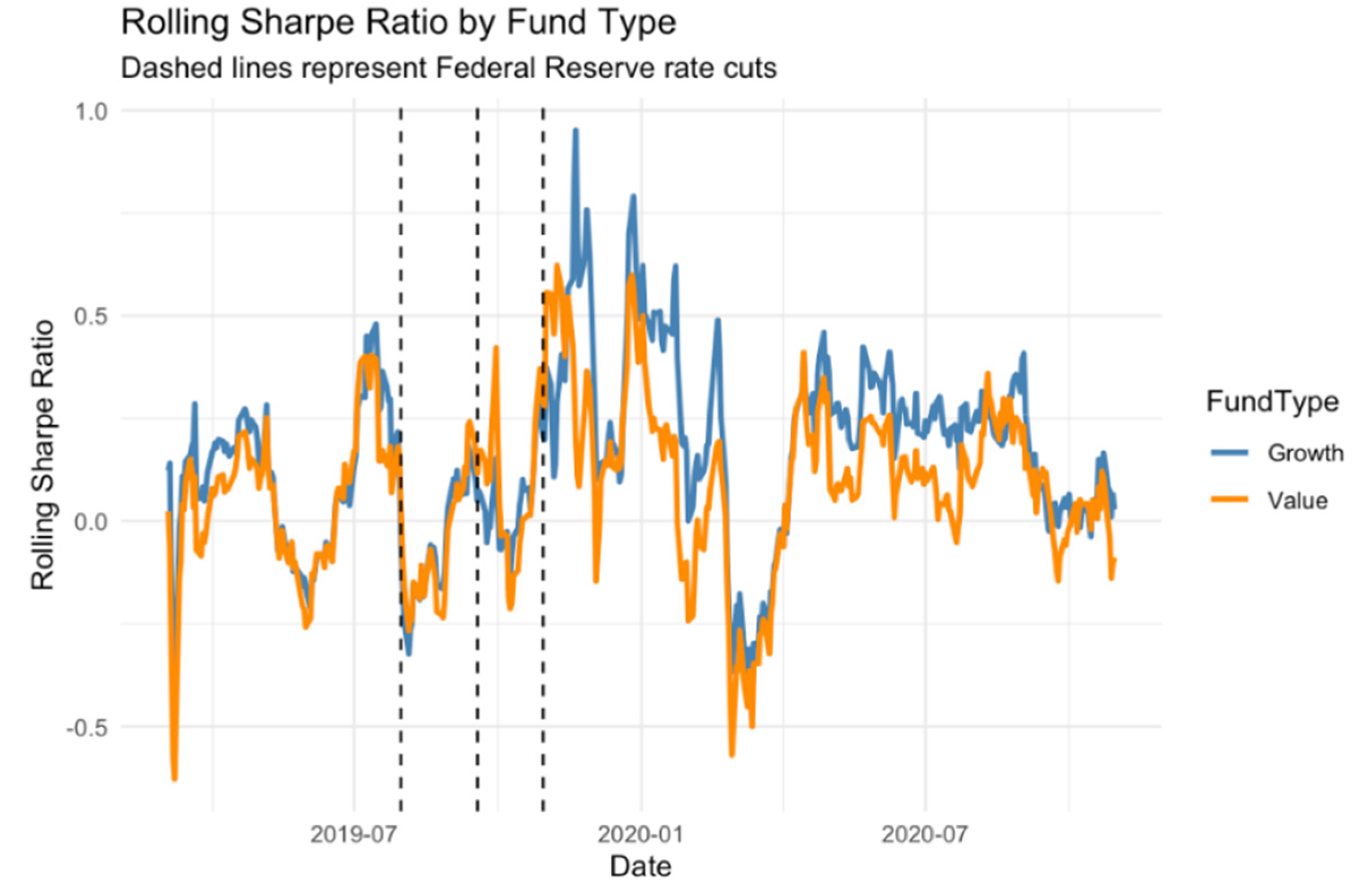

We summarize the results for growth and value funds separately to assess the differences between investment styles. Subsequently, the results section presents rolling estimates of the SR and a. In addition, descriptive statistics are used to summarize their distributions. The use of these dynamic indicators allows us to assess whether monetary easing has been of great benefit to growth funds in terms of risk-adjusted returns.

3.10.1. Sharpe Ratio Regression Framework

Using static and rolling SRs as dependent variables, this study estimates a set of structured linear regression models to determine whether there is a systematic difference in the risk-adjusted performance of growth and value funds, particularly in respect to monetary policy intervention.

Table 3 summarizes the modeling framework and outlines the use of each model.

The first is the cross-sectional model (S1), which uses static SRs computed on the entire sample for baseline comparisons. After adjusting for return volatility, it confirms that growth funds outperform value funds.

Model S4 uses a rolling 30-day SR, regressed on fund style, to capture the dynamics of performance over time. This formula can document the change in risk-return efficiency of different types of funds during and after the policy adjustment period. Models S4_w1 to S4_w5 replicate rolling Sharpe regressions within a discrete event window. These windows include six months and one year after the event, as well as three short-term windows before and after each rate cut. These regressions indicate whether the advantage of growth funds strengthens or weakens during each monetary event.

The core model S5 introduces dummy variables for three time periods (pre-cuts, non-events, and events) and relates them to fund style. This identifies how growth and value funds perform in different monetary environments and provides key evidence of the cyclical sensitivity of fund styles.

Model S6 adds rolling volatility and contemporaneous indicators of market returns to control for other drivers of fund performance. This helps to differentiate between style effects by moderating short-term noise and macro risk.

Finally, model S8_interact analyzes the more complex relationship between style and rolling market returns. How do growth funds perform when the market is trending upward? This reflects the duration-based valuation theory in an environment of monetary easing. Interpretation of the results is based on economic magnitude and statistical significance, focusing on the style coefficients and key interaction terms across time partitions.

3.10.2. Jensen’s Alpha Regression Framework

This study constructs a series of a regression models based on the CAPM framework to assess the impact of monetary policy on risk-adjusted performance. These models use time series and panel structures to compute static and rolling a value for growth and value funds. Furthermore, they incorporate multiple control variables and interaction terms.

The analysis begins with a benchmark model (model lm_model2 in

Table 4), which compares the average a of the various fund styles. This serves as a benchmark for CAPM-based differences in style performance. To provide a dynamic view of style-sensitive risk-adjusted performance, we calculate rolling alpha over a 30-day window (lm_model4) to account for time variation.

By introducing a market return control variable (lm_model3) and an interaction term between fund style and excess market returns (lm_model3_interact), the subsequent model allows for the assessment of heterogeneous responses to market volatility. We add rolling volatility as a control variable (lm_model6) and interact it with fund style to assess the sensitivity to style-related volatility shocks (lm_model6_interact). This further accounts for risk conditions.

Furthermore, we use an event window interaction model (lm_model12_interact) to analyze the impact of policies at specific points in time. The model estimates whether the Jensen alpha changes within a discrete window centered around each rate cut. Finally, a cycle-level interaction model called lm_model14 analyzes alpha performance under a broader set of regimes (pre-cuts, non-event periods, and event periods) to identify differences in style conditional on the stage of monetary policy.

Table 4 contains all model specifications, variable structures, and estimation purposes. This structured framework allows for comparing a dynamics across different market and policy environments.

5. Summary

This research presents a systematic and multi-perspective examination of the effect of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s interest rate reductions throughout the 2019–2020 easing cycle on the performance of equity mutual funds with different investment styles. Using a combination of the event study approach, risk-adjusted performance measures, and regression-based estimation, we derive some important insights.

Growth Fund Outperformance: Growth mutual funds consistently outperform value funds in both short-term and long-term windows, in terms of AR and risk-adjusted metrics (SR and α), reflecting their heightened sensitivity to changes in discount rate stemming from their longer-duration cash flow structures.

Durability of the Growth Premium: The growth premium remains significant over both 6-month and 1-year windows, suggesting that monetary easing leads to persistent revaluation effects and sustained investor flows beyond short-term market reactions.

Behavioral Amplification: Beyond valuation effects, investor behaviors such as increased risk appetite and style-based reallocations (such as yield chasing) further reinforce growth fund outperformance.

Regression Validation of Style-Market Interaction: Regression models confirm that the growth premium persists after controlling market risk and volatility. The interaction effect reveals the growth funds’ pro-cyclicality, with elevated SR during market upturns and diminished performance during high volatility.

Jensen Alpha Sensitivity: While growth funds exhibit lower average α due to their structural exposure to macro risk, they generate higher α in accommodative policy phases, though this edge is not always sustained over longer horizons.

The study has some limitations, pointing out the way for future refinement and extension. First, this analysis focuses on only six representative mutual stock funds: three growth funds and three value funds. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings, even though these funds are carefully selected for their large asset bases, institutional reputations, and consistent investment styles. Although this “typical sample, in-depth analysis” approach is a best practice for event studies, a larger and more diversified fund sample would enhance external validity and cross-sectional robustness.

Second, the study focuses exclusively on the three major rate cuts in 2019, omitting rate hike episodes, fiscal stimulus, and other macroeconomic shocks. Therefore, the findings are only applicable to an easing cycle and may not generalize to tightening environments. Future research should examine asymmetric responses to interest rate hikes to capture the full sensitivity spectrum of fund styles.

Third, the long-term windows were inevitably included with the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, introducing external volatility that may confound pure monetary policy effects. Such exogenous shocks may have amplified or confounded the policy impact, complicating explanations attributable only to changes in interest rates. Although this period offers a natural experiment on crisis-policy interaction, controlling for pandemic shocks, such as using dummies or excluding extreme months, could help to more clearly separate the effects of interest rates.

Fourth, the CAPM framework used in this study provides an easy-to-understand benchmark but neglects potentially influential style factors. Using multifactor models, such as Fama-French’s five-factor models, would improve explanatory power and contribute to a deeper understanding of performance attribution.

Finally, while this study focuses on official FOMC dates, the choice of event windows may still involve subjectivity. Incorporating market-based expectations to isolate “unexpected” monetary shocks could help distinguish between anticipated and surprise effects in future research.

Overall, future research could be extended to (1) increase the sample of mutual funds to cover more investment styles and strategies; (2) consider interest rate hike events to assess policy asymmetries; (3) use causal inference techniques, such as double-differencing or macro-control variables, to improve identification; (4) study multifactor models or quantile regressions to identify distributional effects; and (5) investigate fund responses under different monetary policy regimes. These extensions would enhance the theoretical depth and practical relevance of understanding mutual fund responses to monetary policy.