Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

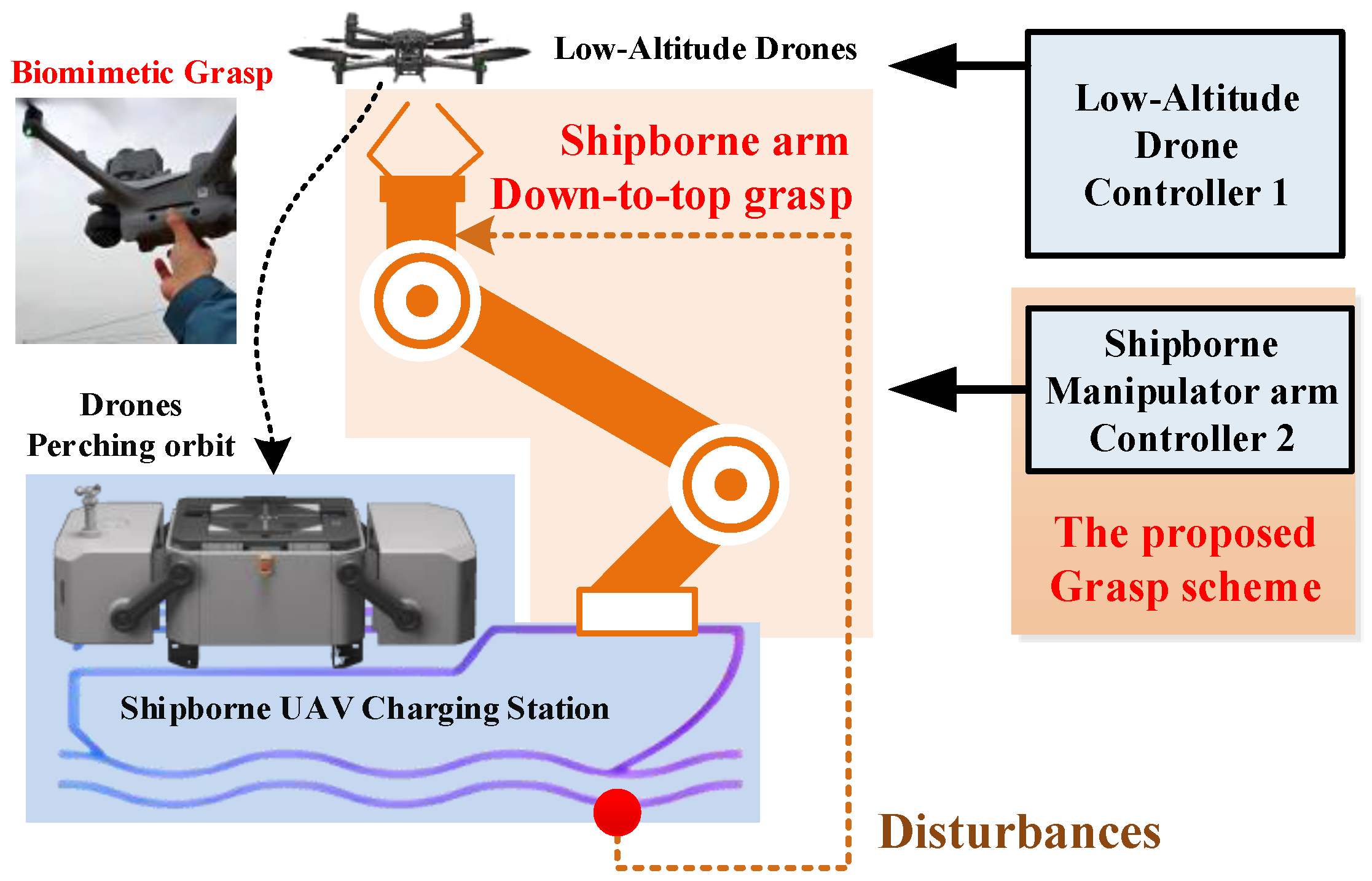

1. Introduction

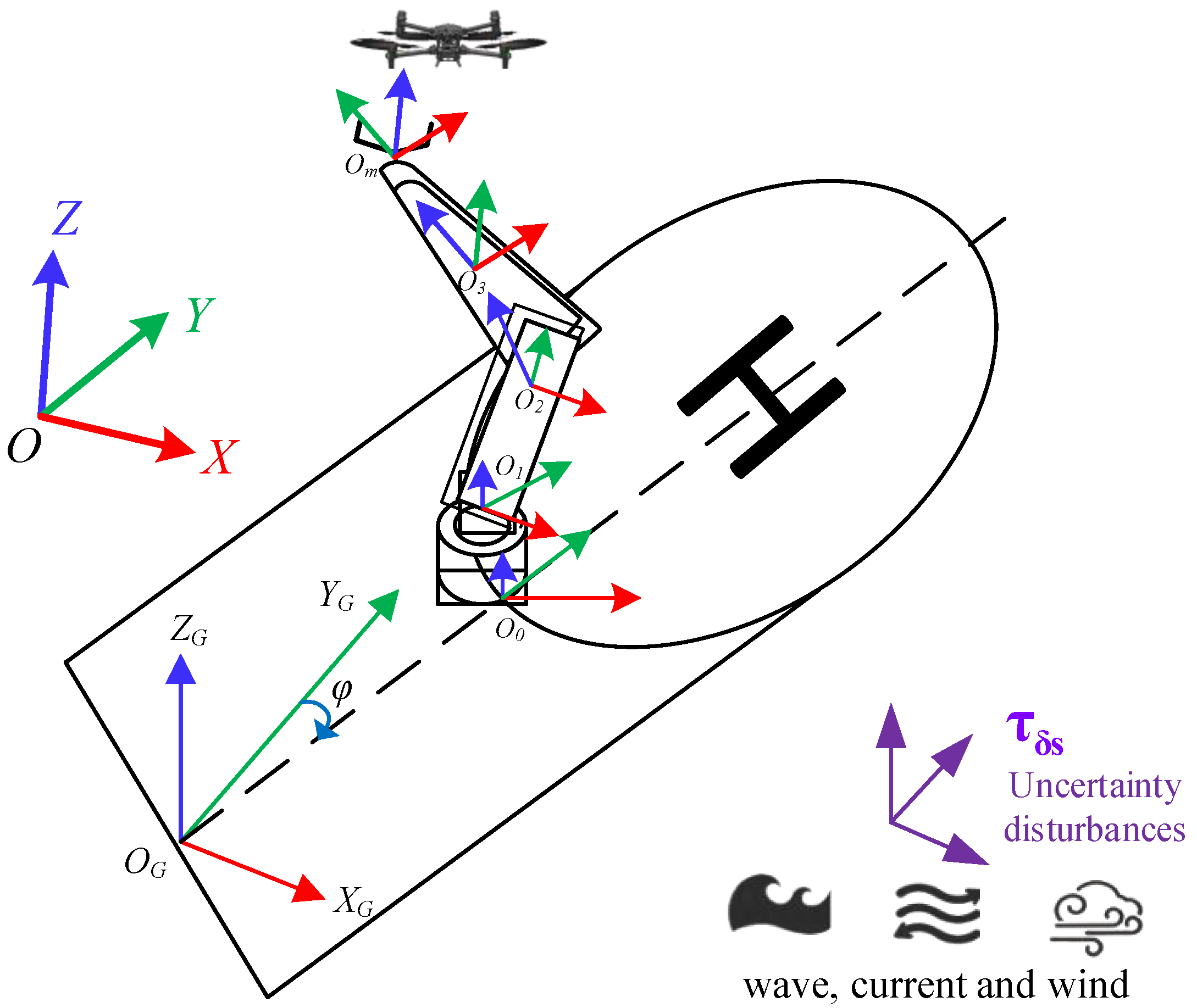

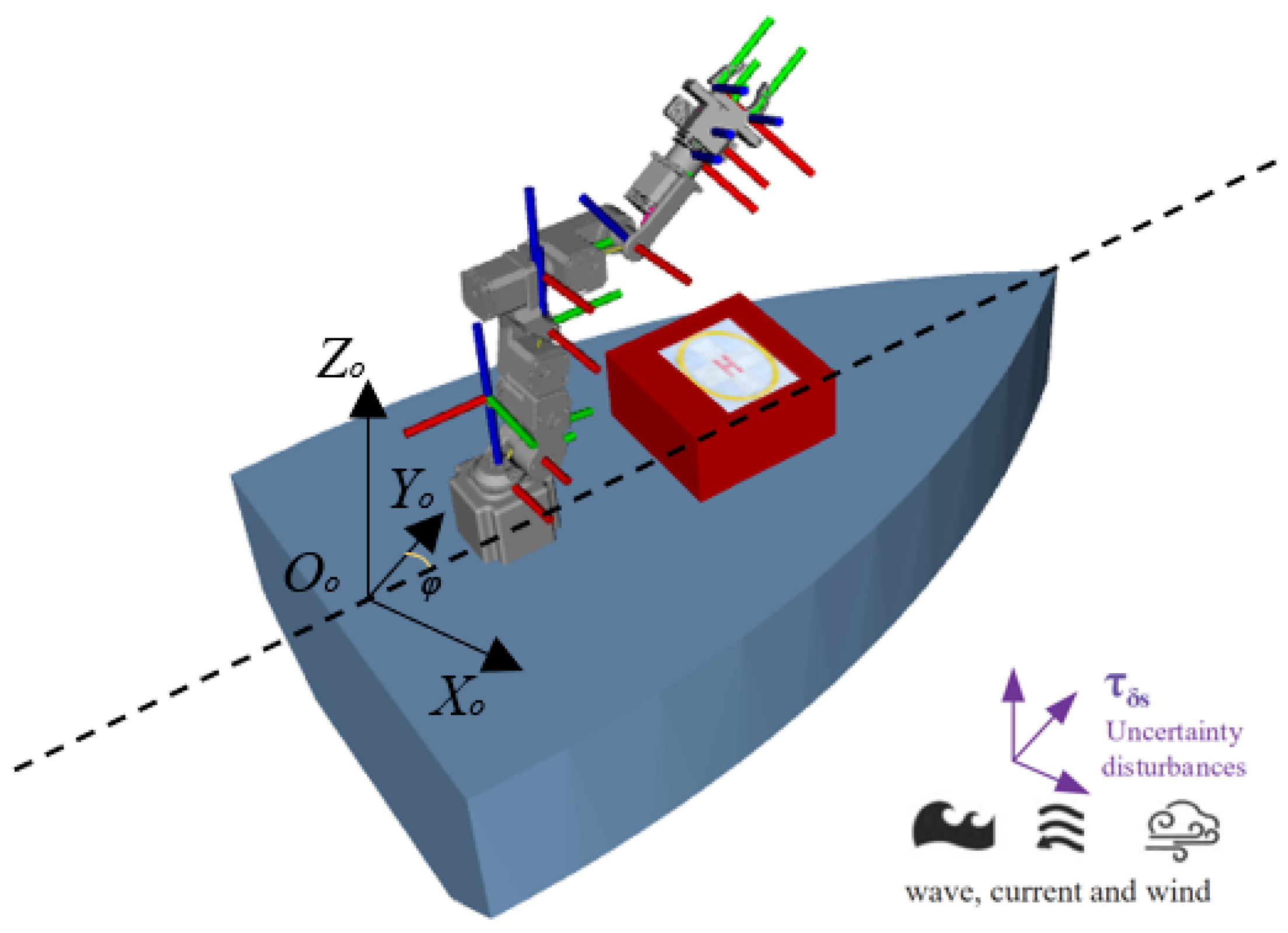

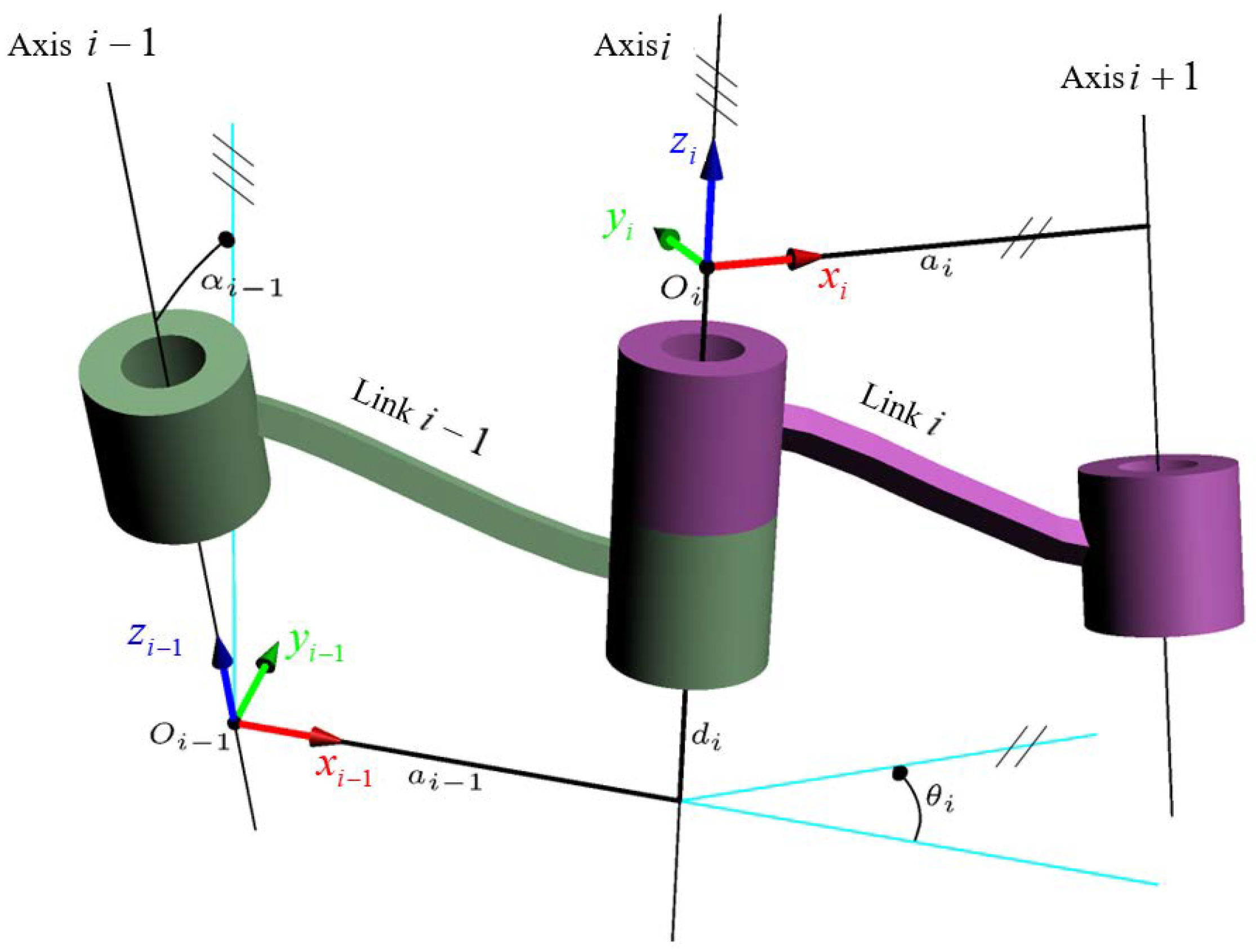

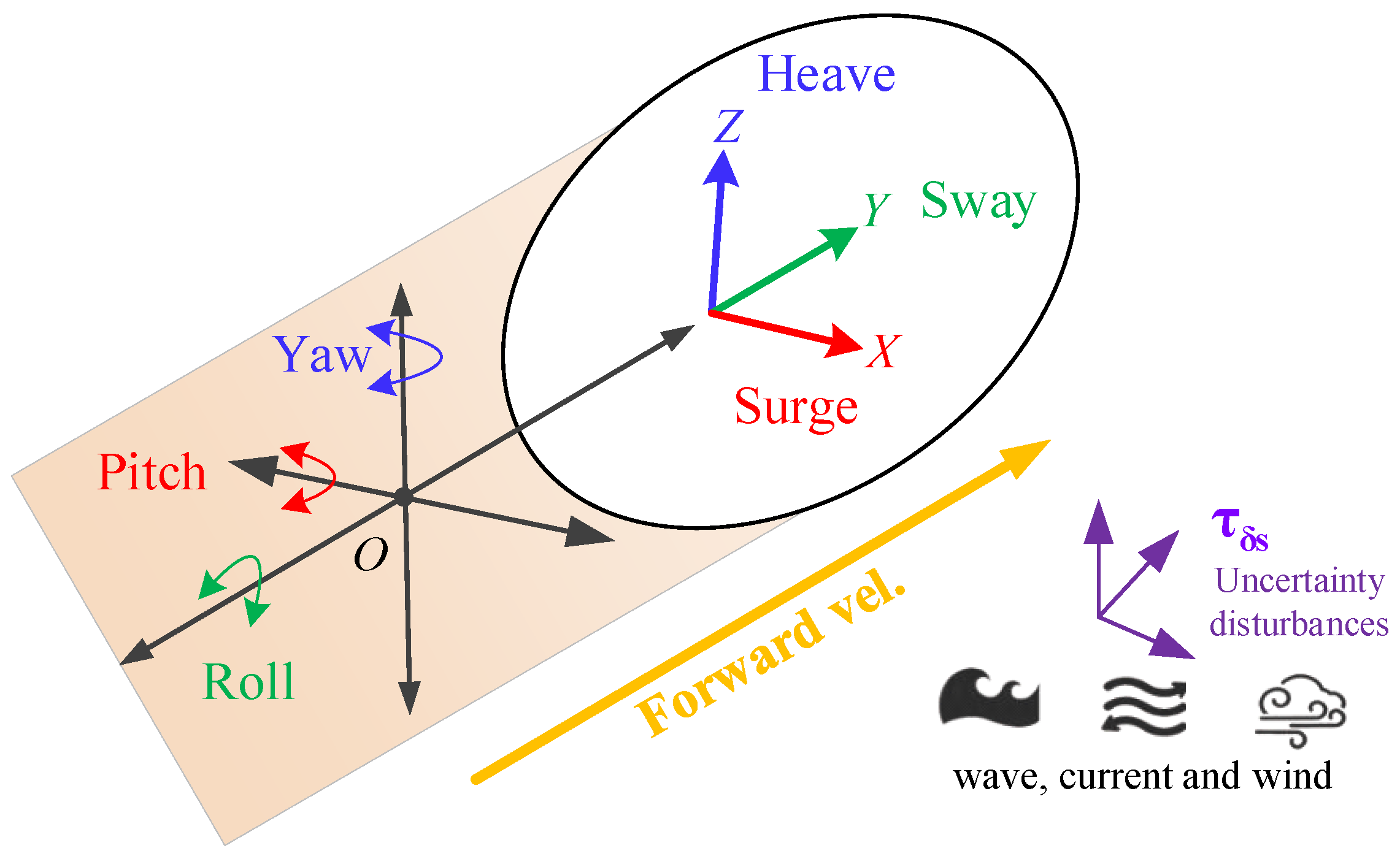

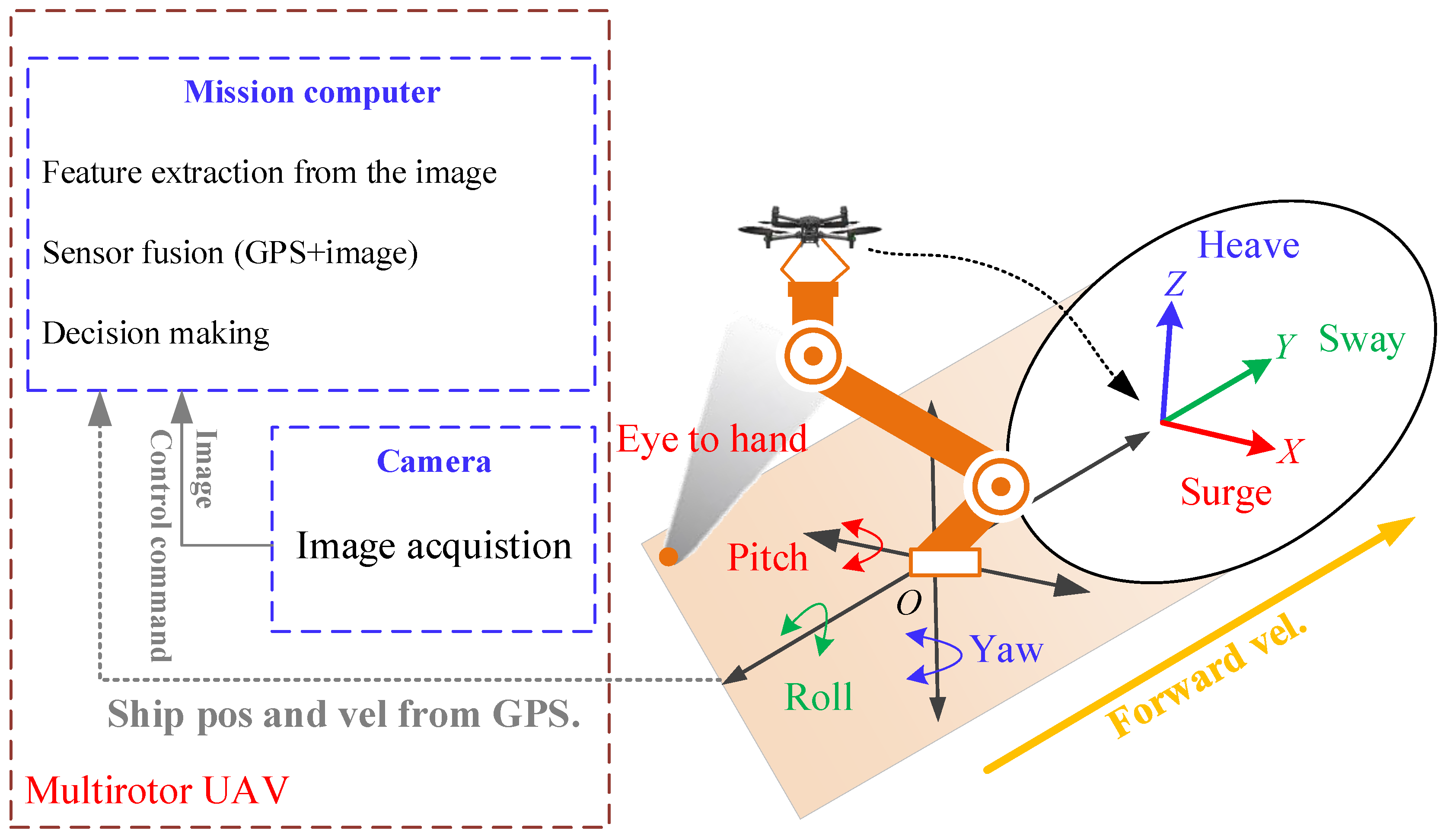

2. Global Dynamic Model and Global Jacobian Matrix

2.1. Global Dynamics of the Shipborne Grasping Arm

2.2. Global Jacobian Matrix and Kinematics of the Shipborne Grasping Arm

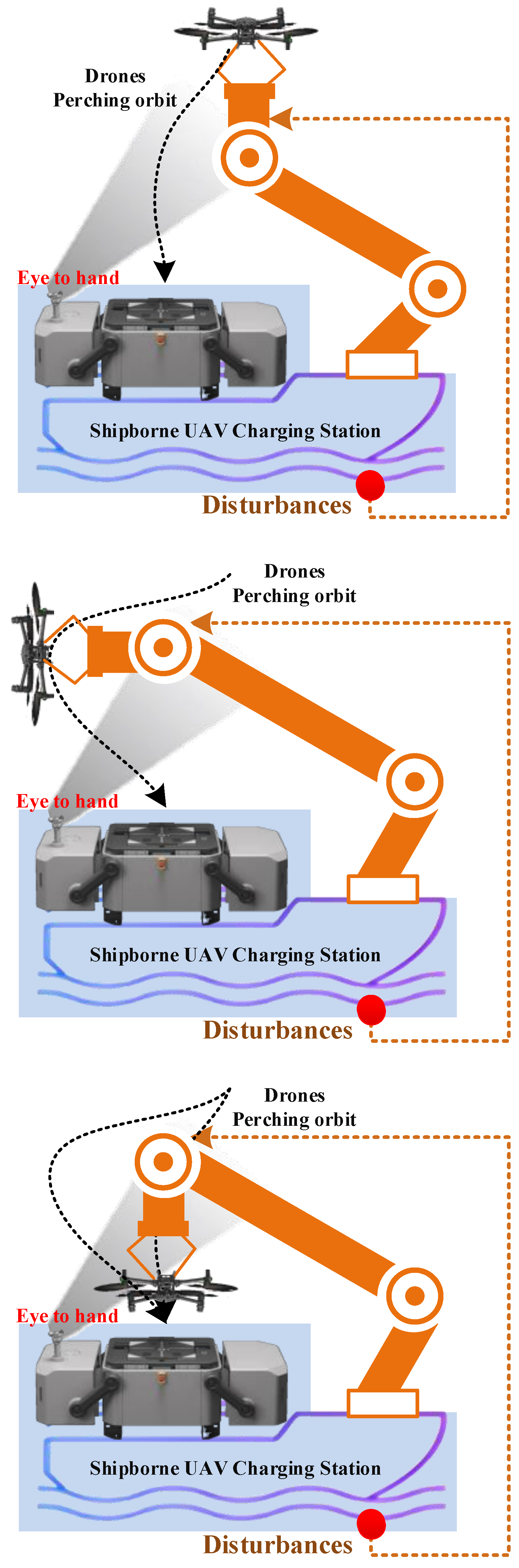

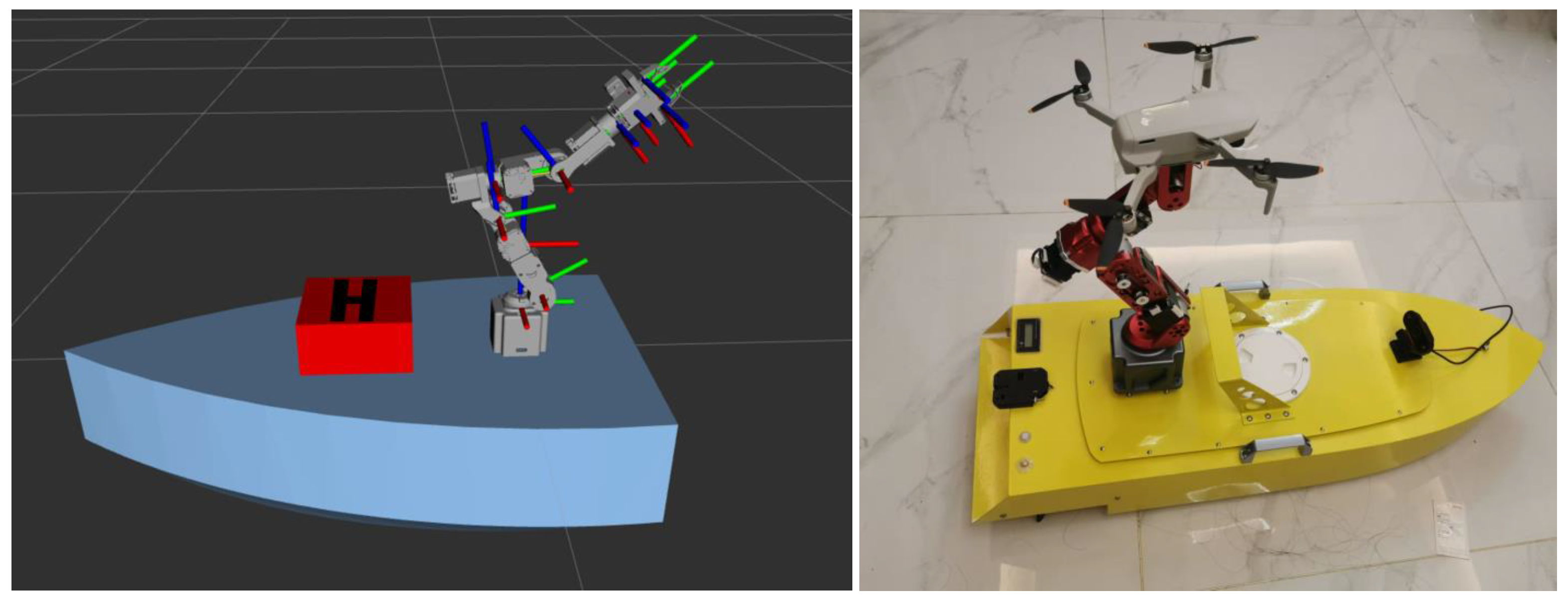

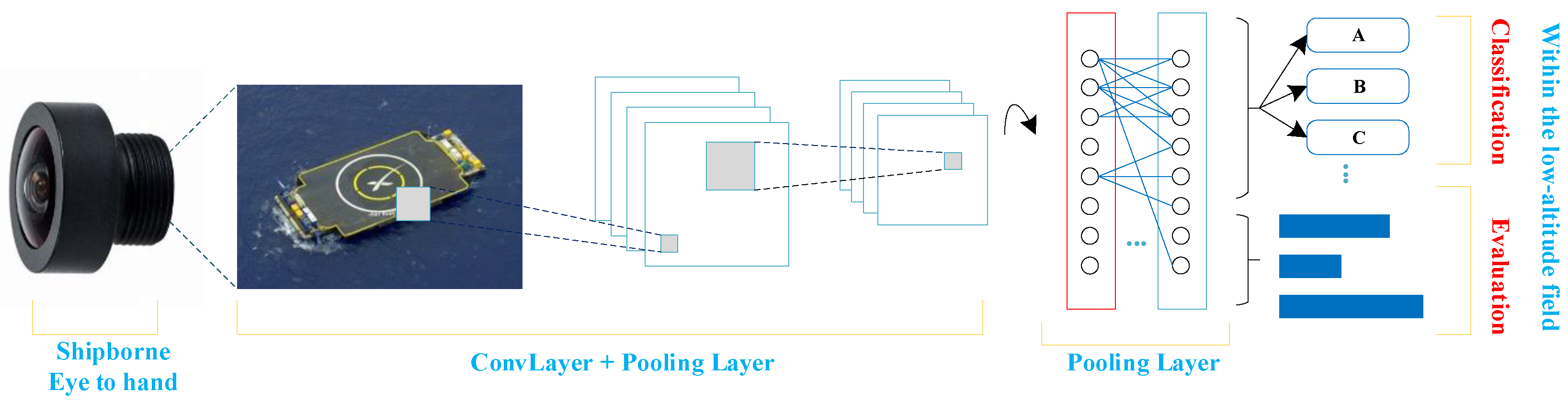

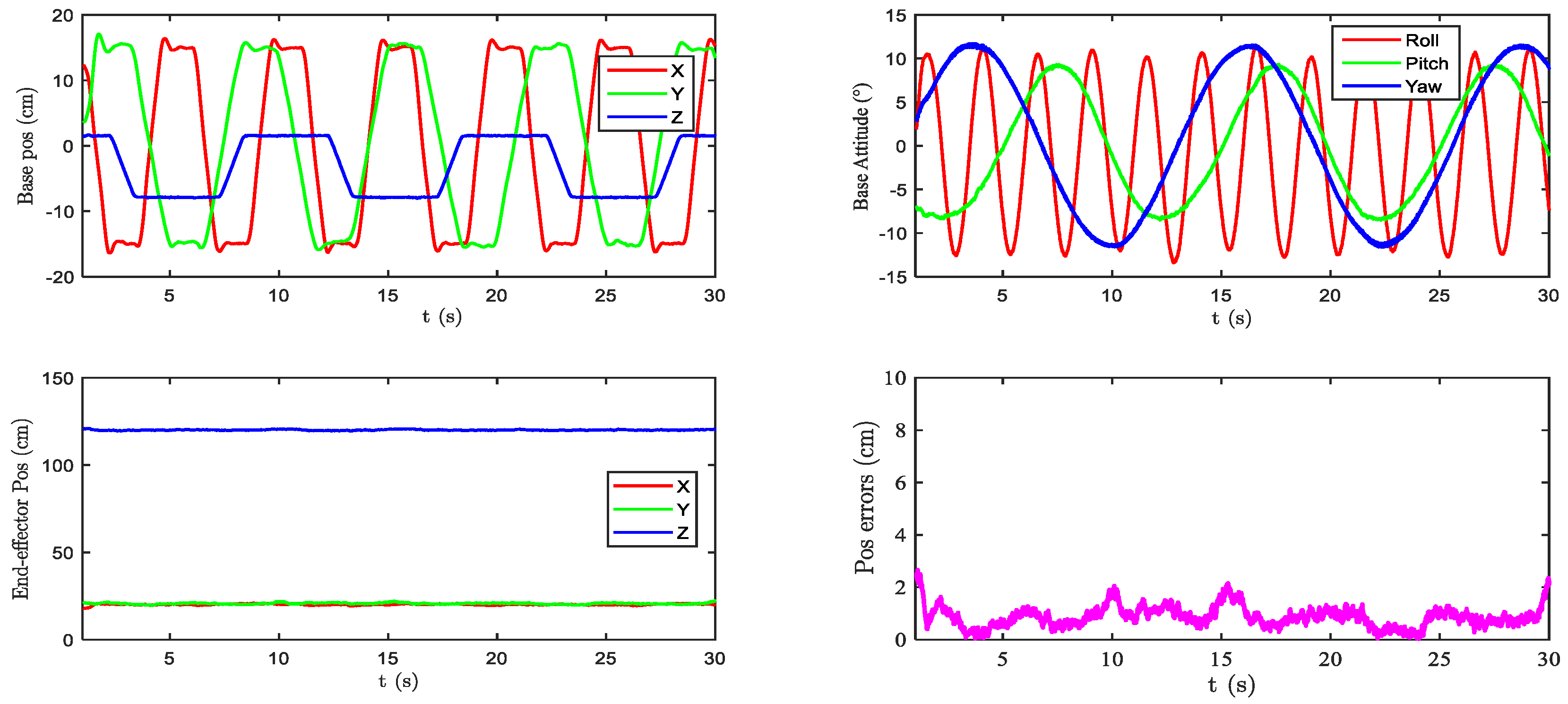

3. Proposed Grasp Docking Paradigm and Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riboldi, C.E.D.; Fanchini, L. Assessing the Technical–Economic Feasibility of Low-Altitude Unmanned Airships: Methodology and Comparative Case Studies. Aerospace 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Loianno, G.; Daniilidis, K.; Kumar, V. Visual Servoing of Quadrotors for Perching by Hanging From Cylindrical Objects. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2016, 1, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, K.; Lyu, X.; Song, H.; Stork, J.A.; Dollar, A.M.; Kragic, D.; Zhang, F. Perching and resting—A paradigm for UAV maneuvering with modularized landing gears. Science Robotics 2019, 4, 6637–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tian, H.; Wang, D.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Cai, S.; et al. Electrically active smart adhesive for a perching-and-takeoff robot. Science Advances 2023, 9, 3133–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, P.; Nohooji, H.R.; Voos, H. Constrained Trajectory Optimization and Force Control for UAVs with Universal Jamming Grippers. Research Square 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Ai, J. Runway-Free Recovery Methods for Fixed-Wing UAVs: A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Choi, J.; Bae, G.; Oh, H. Autonomous ship deck landing of a quadrotor UAV using feed-forward image-based visual servoing. Aerospace science and technology 2022, 130, 107869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, F.; Xie, B.; Ren, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Hybrid Camera Array-Based UAV Auto-Landing on Moving UGV in GPS-Denied Environment. Remote Sensing 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippiello, V.; Mebarki, R.; Ruggiero, F. Visual coordinated landing of a UAV on a mobile robot manipulator. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR); 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, D.; Zanchettin, A.; Simovic, A.; Delmerico, J.; Scaramuzza, D. Vision-based autonomous quadrotor landing on a moving platform. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security and Rescue Robotics (SSRR); 2017; pp. 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Peng, X.; Wang, H.; Niu, W.; Zheng, X. UAV autonomous tracking and landing based on deep reinforcement learning strategy. Sensors 2020, 20, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, B. Grasping Low-Altitude Drones Technology for Shipborne UAV Charging Stations. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 15th International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER), Shanghai, China, July 2025; pp. 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grlj, C.G.; Krznar, N.; Pranjić, M. A Decade of UAV Docking Stations: A Brief Overview of Mobile and Fixed Landing Platforms. Drones 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Ma, Y.; Malekian, R.; Yan, X.; Li, Z. A novel cooperative platform design for coupled USV–UAV systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 15, 4913–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakakis, N.A.; Stamadianos, T.; Marinaki, M.; Marinakis, Y. The electric vehicle routing problem with drones: An energy minimization approach for aerial deliveries. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 2022, 4, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachayappan, M.; Sudhakar, V. A Solution to Drone Routing Problems using Docking Stations for Pickup and Delivery Services. Transportation Research Record 2021, 2675, 1056–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Probe Dynamics Direct Control for Aerial Recovery With Preassigned Docking Performance. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2022, 58, 3509–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, D.; Tan, M.; Yu, J. Implementation of Autonomous Docking and Charging for a Supporting Robotic Fish. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2023, 70, 7023–7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, B.R.; Mahmoudian, N. Simulation-Driven Optimization of Underwater Docking Station Design. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2020, 45, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K.; Goh, B.; Chai, O.K. Fuzzy Docking Guidance Using Augmented Navigation System on an UAV. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2015, 40, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, D.; Wang, L.; Jia, T. Electrical Aircraft Ship Integrated Secure and Traverse System Design and Key Characteristics Analysis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2603–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welschehold, T.; Dornhege, C.; Paus, F.; Asfour, T.; Burgard, W. Coupling mobile base and end-effector motion in task space. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Madrid, Spain, December 2018; pp. 7158–7163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Gao, B.; Zhao, D.; Sheng, H.; Liu, C. A Grasping Configuration Planning Method Inspired by the Geometric Fermat Point. Industrial Robot 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, B.; Hu, A.; Xu, W.; Shen, H.; He, J. Design of a Reconfigurable Gripper With Rigid-Flexible Variable Fingers. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2025, 30, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissi, M.; Moumen, Y.; Berrich, J.; Bouchentouf, T.; Bourhaleb, M.; Rahmoun, M. Autonomous solar USV with an automated launch and recovery system for UAV: State of the art and Design. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Control, Optimization and Computer Science (ICECOCS); IEEE, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, G.; Ma, Y.; Malekian, R.; Yan, X.; Li, Z. A novel cooperative platform design for coupled USV–UAV systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 15, 4913–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lopez, J.L.; Pestana, J.; Saripalli, S.; Campoy, P. An approach toward visual autonomous ship board landing of a VTOL UAV. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2014, 74, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Er, M.J.; Gao, W.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, T. Composite trajectory tracking of a ship-borne manipulator system based on full-order terminal sliding mode control under external disturbances and model uncertainties. Ocean Engineering 2023, 267, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Son, H. Adaptive fixed-time control of autonomous VTOL UAVs for ship landing operations. Journal of the Franklin Institute 2020, 357, 6175–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fang, S.; Li, J.; Gao, B. An Adaptive Dual-Docking Force Control of Ship-Borne Manipulators for UAV-Assisted Perching. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 14th International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER), Copenhagen, Denmark, July 2024; pp. 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notations | Values | Units |

| Degrees of freedom | 6 | |

| Grasp workspace | ||

| End-effector payload | ||

| UAV (DJI mini) weight | ||

| Camera depth range | 1.0 | |

| Ship size |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).