1. Introduction

We live in an era defined by digital technology, in which artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly become an omnipresent and essential tool, reshaping fundamental aspects of daily life. From how we consume information to how we interact socially, make decisions, or manage our emotions, AI is increasingly embedded in multiple domains at an unprecedented pace and depth. Its use has become so common that it often goes unnoticed, even though its effects are increasingly decisive [

1,

2].

From a theoretical perspective, this phenomenon can be understood through the Theory of Technological Mediation, developed by Peter-Paul Verbeek [

3], who argues that technologies are not merely neutral tools but mediating agents that shape human experience, world perception, and interpersonal relationships. According to this theory, technological artifacts—such as AI systems—intervene in human interpretation, action, and morality, shaping the ways in which we think, feel, and make decisions. Rather than conceiving technology as something “external” to the human being, Verbeek proposes understanding it as a co-constructor of the human, that is, as a constitutive part of contemporary experience.

From the lens of technological mediation, these results can be understood as examples of “hermeneutic mediations,” in which AI functions as an interpretive filter that helps individuals make sense of their emotional experiences. Rather than replacing the human therapeutic relationship, these technologies transform how psychological support is accessed, generating a new form of shared agency between humans and machines [

3].

The educational field offers an equally fertile ground to observe this phenomenon. Systems such as Jill Watson, the virtual assistant developed at the Georgia Institute of Technology, or adaptive learning–based intelligent tutors (for example, Knewton or Duolingo Max), illustrate how AI mediates learning processes and teacher–student interactions. Liu et al. [

4] and Brown et al. [

5] document how these systems increase student motivation and autonomy by providing immediate and personalized feedback. In Verbeek’s theoretical terms, these constitute “practical mediations,” in which technology guides action and transforms educational practice itself.

Therefore, this type of more human and empathetic interaction has opened new opportunities to apply AI in areas that were once considered sensitive, such as mental health, emotional well-being, and academic or educational contexts [

4,

5,

6]. Proposals that integrate virtual assistants into psychological support programs or personalized educational interventions are becoming more frequent. Indeed, some studies have shown that these virtual assistants can help reduce mild mental health symptoms such as anxiety or depression, particularly when used in brief, accessible, and low-cost interventions [

7,

8].

However, this technological revolution also raises important questions about its real scope and ability to benefit everyone equally. Perceptions of AI’s effectiveness, reliability, and usefulness are not always positive, and multiple personal, social, and cultural factors influence its actual impact. Significant disparities exist in access, trust, and the way different population groups integrate these tools into their daily lives [

9,

10].

One group facing greater challenges in this digital landscape is people with disabilities. Far from being a homogeneous category, disability encompasses a diversity of physical, sensory, intellectual, and psychosocial conditions that may significantly influence interactions with digital systems. In many cases, these technologies are not designed with universal accessibility in mind, nor do they consider the specific needs of this population, creating functional, semantic, and emotional barriers [

11,

12]. Failure to address these needs risks digitally excluding certain groups from the benefits of AI, potentially exacerbating pre-existing inequalities and restricting fundamental rights such as participation, communication, and access to mental health services [

13,

14].

Within this context, young people with disabilities represent a group of particular interest. On the one hand, as digital natives, they are highly familiar with digital tools, which can foster empowerment, social inclusion, and improved emotional well-being [

15,

16]. On the other hand, they continue to face structural and attitudinal barriers that prevent equal access to technological platforms and emotional support resources that meet their needs [

17,

18]. Difficulties accessing conversational AI systems, combined with the limited emotional sensitivity of some models, may increase the risk of social isolation and restrict autonomy during critical stages of personal development [

19].

By contrast, students without disabilities generally enjoy better conditions of access, usage experience, and participation in digital environments. This allows them to use AI-based tools more independently and frequently, contributing to a more natural integration of these technologies into their daily lives [

20]. Comparing both groups—students with and without disabilities—makes it possible to identify not only access gaps or differences in perceived usefulness but also opportunities to design truly inclusive technologies that adapt to human diversity from their earliest stages of development [

21,

22].

This study stems from the need to move beyond the traditional analytical focus—often limited to users without disabilities—to adopt a more inclusive and representative perspective. It proposes a comparative analysis to explore how perceptions of AI usefulness, particularly as an emotional and informational support resource, differ among students with diverse personal conditions. It also examines how frequency of use influences these perceptions, and whether a bidirectional relationship exists: whether sustained use leads to more favorable perceptions, or whether an initially positive view drives continued use [

9].

From this standpoint, the study seeks to contribute to a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the role AI can play in the emotional and communicative lives of young people, especially those historically marginalized in the design of emerging technologies.

This general objective is broken down into the following specific objectives:

1.To describe the level of familiarity with and current use of AI technologies among students with and without disabilities.

2.To compare perceptions of AI usefulness between students with disabilities and those without disabilities.

3.To analyze the relationship between perceived usefulness and frequency of AI use in both groups.

Based on these objectives, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. Students without disabilities will report higher levels of familiarity and frequency of AI use compared to students with disabilities.

H2. Significant differences exist in the perceived usefulness of AI as an informational and emotional support tool between students with and without disabilities.

H3. Direct experience with AI systems will mediate the relationship between disability status and perceived usefulness, such that greater use reduces differences between groups.

H3.1. Students with disabilities will report greater perceived barriers to AI use (e.g., accessibility, emotional adequacy, semantic understanding), which will negatively impact their perception of usefulness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study was conducted with a sample of 358 university students aged 16 to 30 (M = 22.4; SD = 4.1), residing in urban and semi-urban areas. Of the total sample, 88 participants (24.6%) identified as having a disability, while 270 (75.4%) reported no disability. Participants were recruited through partnerships with higher education institutions, social organizations, and community platforms, ensuring diversity in profiles and contexts.

Key sociodemographic variables such as gender and age were balanced across groups.in terms of gender 53.1% were women (n = 190) and 46.9% men (n = 168), proportions that were consistent in both groups. The average age was 22.1 years (SD = 4.2) in the disability group and 22.5 years (SD = 4.1) in the non-disability group.

Participants were enrolled in various academic disciplines. The most represented fields were Social Sciences (30.2%), Health Sciences (24.3%), Engineering and Technology (22.6%), Economics and Business (13.7%), and Arts and Humanities (9.2%). The distribution across fields was similar in both groups, reinforcing the comparative homogeneity of the sample.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the ample by Disability Status.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the ample by Disability Status.

| |

Variable |

Total (n = 358) |

With disability (n = 88) |

Without disability (n = 270) |

| Gender |

Women |

190 (53.1%) |

47 (53.4%) |

143 (53.0%) |

| Men |

168 (46.9%) |

41 (46.6%) |

127 (47.0%) |

| Age (M, SD) |

|

22.4 (4.1) |

22.1 (4.2) |

22.5 (4.1) |

| |

Social Sciences |

108 (30.2%) |

27 (30.7%) |

81 (30.0%) |

| |

Health Sciences |

87 (24.3%) |

20 (22.7%) |

67 (24.8%) |

| Field of study |

Engineering & Technology |

81 (22.6%) |

20 (22.7%) |

61 (22.6%) |

| |

Economics & Business |

49 (13.7%) |

12 (13.6%) |

37 (13.7%) |

| |

Arts & Humanities |

33 (9.2%) |

9 (10.2%) |

24 (8.9%) |

2.2. Instruments

A self-developed instrument was designed to collect basic participant information, including gender, age, disability status, and academic field.

Data were gathered using a Likert-scale questionnaire (1 = Never, 5 = Very frequently), structured into three sections addressing familiarity, frequency of use, and perceived usefulness of AI for informational and emotional support.

Familiarity with AI. This section explored participants’ prior knowledge and exposure to AI. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants rated how familiar they felt with the concept, whether they had received training, their understanding of how AI works, and how often they seek information about advancements in the field. This section assessed participants’ subjective sense of closeness to AI.

Frequency of AI use. Participants reported how often they used various AI-enabled applications or platforms in daily life, including virtual assistants (e.g., Siri, Alexa), mental health apps, chatbots, educational tools, or entertainment platforms. Responses, also on a Likert scale, provided a map of participants’ real and routine engagement with AI technologies.

Perceived usefulness of AI. This section assessed how students evaluated AI’s usefulness in two key dimensions: informational and emotional support. For informational support, items examined whether participants considered AI helpful in providing clear, useful, and timely information and whether they saw it as valuable for learning or productivity. For emotional support, items measured whether AI interactions felt comforting, whether responses seemed empathetic, and whether participants sometimes preferred AI over human support. Responses were rated on a 5-point agreement scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree), capturing nuanced perceptions.

Table 2.

Dimensions and items of the questionnaire on familiarity, frequency of use, and perceived usefulness of artificial intelligence (AI).

Table 2.

Dimensions and items of the questionnaire on familiarity, frequency of use, and perceived usefulness of artificial intelligence (AI).

| Dimension |

Items |

| 1. Familiarity with AI |

- How familiar do you feel with the term artificial intelligence?

- Have you used applications or platforms with AI?

- Do you consider that you understand how AI based technologies work?

- Have you received information or training about AI?

- How often do you seek information about AI advancements? |

| 2. Frequency of AI use |

- Use of virtual assistants (Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant)

- Use of chatbots for inquiries or digital support

- Use of AI-based wellness or mental health apps

- Use of AI for educational or study-related tasks

- Use of AI for entertainment or socialization |

| 3. Perceived usefulness of AI |

Informational support

- AI helps me obtain useful information quickly

- AI-generated responses are clear and accurate

- I use AI to complement my learning or studies

- AI facilitates access to hard-to-find resources

- AI improves my academic or personal productivity

Emotional support

- AI provides me with emotional support when I need it

- I feel comfortable expressing emotions through AI

- AI responses to emotional topics are empathetic and appropriate

- AI can help reduce feelings of loneliness or isolation

- I prefer using AI for certain emotional topics rather than talking to people |

| |

|

2.3. Psychometric Properties of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire developed for this study demonstrated adequate validity and reliability, supporting its use as an instrument to assess familiarity, usage, and perceived usefulness of AI among university students with and without disabilities.

Content validity was ensured through review by three experts in educational technology, psychology, and digital accessibility. They evaluated the clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of the items for the target population, making lexical and structural adjustments as needed. The final version was understandable and culturally appropriate for both students with and without disabilities, with neutral language and adaptability to accessible formats.

To verify psychometric properties, sample adequacy was first tested using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Results showed a KMO of .840 and a Bartlett’s significance of .001, indicating that the sample size was adequate and the covariance matrix suitable for factor analysis. An exploratory factor analysis (principal components extraction with varimax rotation) revealed a clear two-factor structure: informational usefulness and emotional usefulness. These two factors explained 34.2% and 29% of the variance, respectively, accounting for 63.2% of the total variance, thus supporting construct validity. To reinforce construct validity, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was subsequently conducted. The CFA results indicated an adequate fit for the three-factor model, with fit indices of CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.045 (90% CI: 0.032–0.058), and SRMR = 0.038. All standardized factor loadings were significant (p < 0.001) and exceeded 0.50, confirming that each item consistently measured its corresponding theoretical dimension.

Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to estimate internal consistency. The AI familiarity subscale yielded an alpha of 0.81, indicating acceptable homogeneity across items. The frequency of use scale obtained an alpha of 0.84, while the perceived usefulness scale showed even higher reliability, with an overall alpha of 0.89. At the subscale level, informational usefulness had an alpha of 0.86, and emotional usefulness an alpha of 0.82, demonstrating strong internal consistency in both domains.

These results indicate that the questionnaire consistently and reliably measures the intended constructs, reinforcing its suitability for use in similar studies with young populations in educational contexts.

Prior to the main study, the instrument was piloted with a sample of 85 students with similar demographics, allowing potential comprehension issues to be identified and item wording refined. The final version of the questionnaire was administered online and in accessible formats, ensuring inclusivity for participants with different levels of functionality.

2.4. Procedure

Data collection was carried out over three months in 2025, following approval from an institutional ethics committee and with informed consent from all participants (or legal guardians when required).

Participants completed the questionnaire either in person or digitally, with appropriate support provided for those requiring assistance—particularly students with visual or intellectual disabilities. Sessions were supervised to address questions and ensure response quality.

Statistical analyses included ANOVA tests to compare perceptions and frequency of use between students with and without disabilities, as well as across disability types. Effect sizes were calculated to determine the practical significance of differences, and correlations were conducted to examine relationships between perceived usefulness and AI use.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were processed using SPSS (version 28.0). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were first computed for sociodemographic variables and questionnaire indicators, to profile the sample and assess familiarity, use, and perceptions of AI among students with and without disabilities.

Group differences in familiarity, frequency of use, and perceived usefulness of AI were examined using one-way ANOVA, with significance set at p < .05. When significant differences were found, effect sizes were calculated using partial eta squared (η2p), following conventional benchmarks (0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, 0.14 = large).

To explore relationships between perceived usefulness and AI usage frequency, Pearson correlation analyses were performed, considering both the strength and direction of associations. Linear regression analyses were also conducted to assess whether frequency of use predicted perceived usefulness in both groups and to identify possible moderating or mediating variables.

3. Results

3.1. Objective 1: To Describe the Level of Familiarity and Current Use of AI Technologies Among Students with and Without Disabilities

To address this objective, ANOVA was applied to compare mean levels of AI familiarity and usage between students with and without disabilities. Disability status (yes = 1, no = 0) served as the independent variable, while dependent variables were: (a) AI familiarity (measured on a 5-point scale), and (b) frequency of AI use in daily life (ordinal scale transformed into a continuous variable).

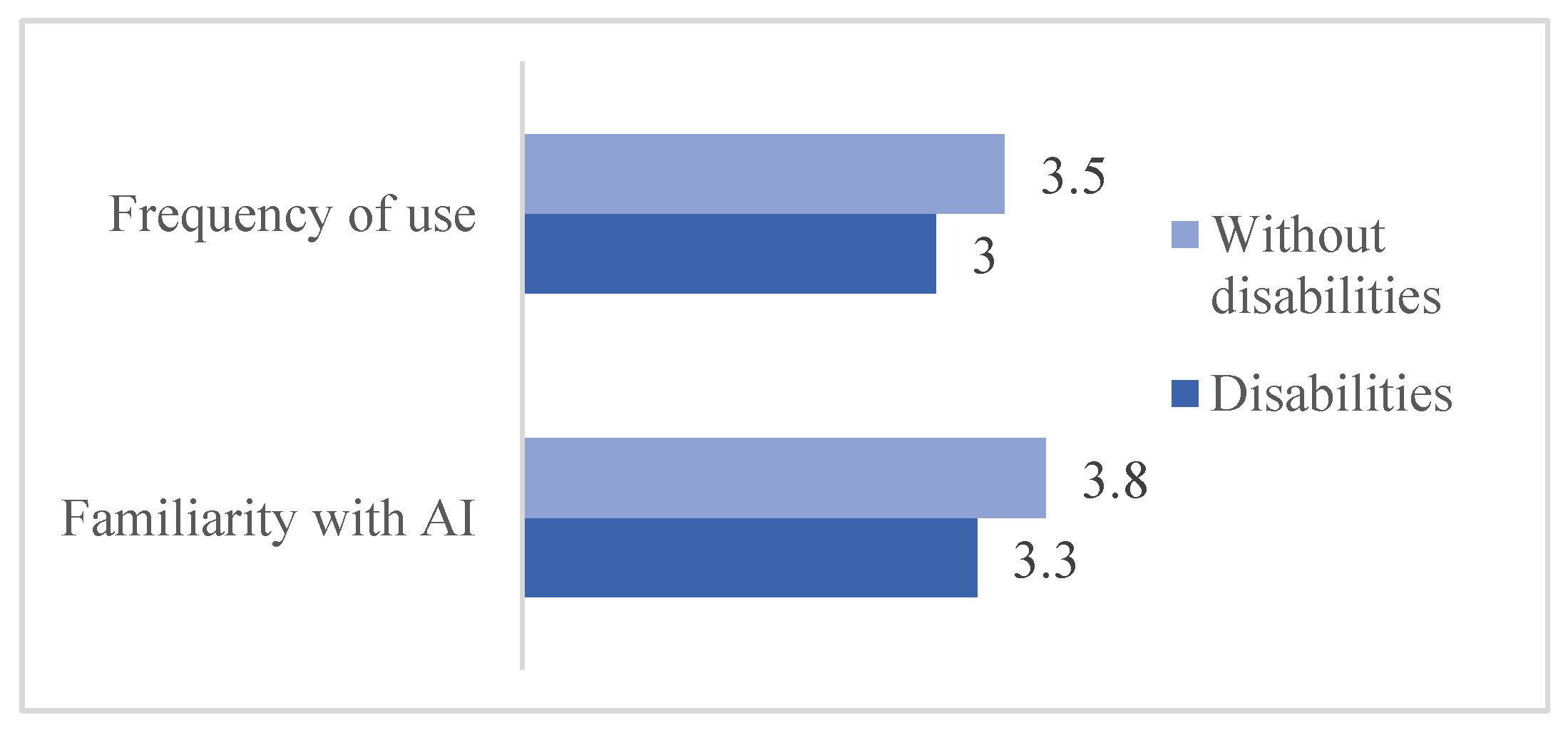

Results revealed statistically significant differences between groups in both variables. Students without disabilities reported significantly higher familiarity (M = 3.8, SD = 0.9) and frequency of use (M = 3.5, SD = 0.8) compared to their peers with disabilities (familiarity: M = 3.3, SD = 1.0; use: M = 3.0, SD = 0.9). The analysis showed small but meaningful effect sizes, with a magnitude of η2 = .13 for familiarity and η2 = .44 for frequency of use.

These findings suggest that, although both groups engage with AI technologies, students without disabilities have a more consolidated usage experience, which may influence subsequent perceptions of usefulness.

Figure 1.

Comparison of AI familiarity and use by disability status.

Figure 1.

Comparison of AI familiarity and use by disability status.

3.2. Objective 2: Comparing Perceptions of Usefulness Between Students with and Without Disabilities

Statistical analyses revealed significant differences between young people with and without disabilities regarding their perception of the usefulness of AI, both in its informational and emotional dimensions, as well as in the overall score.

First, with regard to informational support, students without disabilities reported a higher perception of usefulness (M = 3.7; SD = 0.8) compared to their peers with disabilities (M = 3.4; SD = 0.9). This difference was statistically significant (t(356) = 2.98, p < .05), with a small-to-moderate effect size (d = 0.36). This indicates that students without disabilities find AI to be a more efficient resource for accessing information, complementing their studies, and improving their academic productivity.

Regarding emotional support, a significant difference was also observed between groups (t(356) = 2.17, p < .05), with a lower mean reported by the group with disabilities (M = 2.9; SD = 1.0) compared to the group without disabilities (M = 3.2; SD = 0.9). Although the effect size was more modest (d = 0.28), the data suggest that individuals with disabilities may encounter greater barriers in experiencing AI as an empathetic or emotionally satisfying resource. This could be due to frustrating interaction experiences, accessibility limitations, or a lack of personalization in system responses.

Finally, when considering the overall usefulness of AI (composite mean of both dimensions), a significant difference was once again found between groups (t(356) = 3.16, p < .05), with an effect size close to moderate (d = 0.39). This finding reinforces the idea of a structural gap in AI use, whereby young people with disabilities perceive fewer benefits from these technologies, both in terms of information access and emotional support.

Although these differences are not extreme in magnitude, they are consistent and significant and should be understood not as a reflection of an inherent limitation of the group with disabilities, but as the result of technological, cognitive, and contextual barriers that hinder an equitable user experience. In this sense, the findings align with the social model of disability, showing that the inequalities perceived in the usefulness of AI are not inherent to the individual but arise from a design that has yet to adequately consider user diversity.

Table 3.

Comparison of AI familiarity and use by disability status.

Table 3.

Comparison of AI familiarity and use by disability status.

| Dimension |

Group |

M (SD) |

t(356) |

p |

Cohen’s d |

| Informational support |

With disability |

3.4 (0.9) |

2.98 |

.003 |

0.36 |

| Without disability |

3.7 (0.8) |

| Emotional support |

With disability |

2.9 (1.0) |

2.17 |

.031 |

0.28 |

| Without disability |

3.2 (0.9) |

| Overall usefulness |

With disability |

3.15 (0.85) |

3.16 |

.002 |

0.39 |

| Without disability |

3.48 (0.78) |

3.3. Objective 3: Analyzing the Relationship Between Perceived Usefulness and Frequency of AI Use in Both Groups

To analyze this objective, a bivariate Pearson correlation was conducted between frequency of use and perceived usefulness, both for the total sample and by group. In addition, a linear regression model with interaction was applied to evaluate whether disability status moderated this relationship.

Results showed a moderate positive correlation in the total sample (r = .42, p < .001), indicating that the more frequently AI is used, the higher its perceived usefulness. When disaggregated by group, the relationship was stronger among students without disabilities (r = .45) than among students with disabilities (r = .29), although both were statistically significant.

The moderated regression analysis confirmed a significant interaction effect between AI use and disability status (β interaction = -0.19, p < .05), suggesting that the impact of frequency of use on perceived usefulness is weaker among students with disabilities.

Table 4.

Moderated linear regression: interaction between use and disability.

Table 4.

Moderated linear regression: interaction between use and disability.

| Predictors |

β |

t |

p |

| Frequency of use |

0.38 |

7.44 |

< .001 |

| Disability (0 = no, 1 = yes) |

-0.15 |

-2.88 |

.004 |

| Use × Disability (interaction) |

-0.19 |

-2.32 |

.021 |

| Model R2

|

0.27 |

|

|

4. Discussion

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into higher education has transformed learning dynamics, generating new opportunities and challenges for university students [

1,

3,25]. Within this context, the present study identified three motivational profiles toward AI use (Academic-High, Balanced, and Emotional-Informational) and explored their relationship with resilience dimensions: personal and social competence, self-discipline, and self-acceptance [

12,

13,

18].

The results of this study provide a positive outlook on how university students—both with and without disabilities—engage with AI when using it as an informational and emotional resource. Through a comparative approach, it was possible to identify significant differences not only in the degree of familiarity and use of these technologies but also in how their usefulness is perceived in everyday life.

One of the clearest findings is that students without disabilities reported considerably higher levels of familiarity and frequency of use of AI-based tools. This result is consistent with existing evidence showing that people with disabilities often face more obstacles in accessing digital technologies [

13,

14]. Although multiple digital solutions have been developed in recent years with the goal of improving accessibility, structural barriers still persist that hinder equitable adoption. Digital environments often fail to adequately respond to the diverse functional, cognitive, and emotional needs of this population.

Regarding perceived usefulness, the group without disabilities also provided more favorable assessments. This can partly be explained by their greater experience and familiarity with these tools. Individuals who use technologies more frequently tend to be more aware of their advantages—such as quick access to information, academic support, or even a sense of companionship during times of stress or uncertainty. Furthermore, people who face fewer technical or communication barriers tend to have smoother and more satisfactory interactions with AI systems, which reinforces a positive perception of their usefulness. These findings align with other studies warning that non-inclusive technology design tends to widen the digital divide, excluding those who could benefit the most from adapted tools [

12,

20].

Nevertheless, it is important to note that students with disabilities were not entirely reluctant toward AI use, nor did they perceive it negatively—rather, their perceptions were more moderate. This nuance reflects that this group also recognizes the potential value of these technologies, even though their experience is limited by factors such as usability or lack of personalization.

At this point, it is crucial that developers, educational institutions, and technology policymakers view accessibility not as a complement, but as a fundamental design principle from the outset. Including diverse perspectives from the early stages of technological development not only improves the experience of those currently facing barriers but also contributes to building fairer, more sensitive, and more sustainable digital environments for all of society.

The analysis of the second objective, a direct comparison between groups using t-tests, revealed significant differences in perceptions of AI usefulness, with a small-to-moderate effect size. Although these differences are not extreme, their systematic and repeated nature suggests the existence of a stable gap in symbolic and functional access to these technologies. This disparity cannot be attributed solely to individual variables, such as personal interest or technological familiarity, but likely reflects a more complex interplay of social, technological, and educational inequalities shaping digital experiences across groups.

From this perspective, the social model of disability is highly relevant, as it emphasizes that the barriers faced by people with disabilities do not arise from the disability itself but from environments that fail to adequately accommodate human diversity [

17,

18].

Regarding the third objective, the study explored the relationship between perceived usefulness and AI use frequency. Correlational results revealed a positive association in both groups, suggesting a feedback mechanism: students who use AI more frequently tend to perceive it as more useful, and positive perceptions, in turn, encourage more intensive use. However, moderated regression analysis showed that this effect was significantly weaker in the group with disabilities. This could be interpreted as a warning sign: in this group, frequent use does not always translate into a better experience or more positive perception, possibly due to accessibility barriers or unmet expectations.

Notwithstanding, it is important to recognize the limitations of this study. First, as a cross-sectional study, it only captures associations at a specific point in time, without allowing causal inferences or understanding changes over time. Second, participation was voluntary, meaning that respondents may have had particular interests or experiences with AI. This could introduce bias, as non-participants may hold different views or behaviors, limiting representativeness. Third, the group of students with disabilities was smaller than the group without disabilities, which reduces the strength of generalizations. Furthermore, disabilities were not differentiated by type, so we cannot determine whether, for example, students with visual impairments experience AI differently than those with intellectual or auditory disabilities. Lastly, the study was conducted in a specific cultural and educational context—university students in one region—which limits generalization to other educational levels, age groups, or cultural settings.

Despite these limitations, the findings provide valuable insights and encourage cautious interpretation while pointing toward future research with broader and more diverse designs.

Theoretically, these results make a meaningful contribution to technology acceptance models, particularly the TAM (Technology Acceptance Model) proposed by Davis [

23] and later extended by Venkatesh et al. [

24]. While widely validated, the present findings suggest that TAM could be enriched by incorporating variables specific to accessibility, emotional support, and users’ sociotechnological contexts. Technology adoption processes are not neutral, and explanatory models must reflect the diversity of user experiences.

Practically, the results highlight key areas for intervention. First, educational institutions play a strategic role in democratizing access to AI tools—not only by providing technology but also through training initiatives that promote critical digital literacy and awareness of ethical and inclusive AI use. Second, AI developers—particularly those designing applications for informational, educational, or emotional support purposes—must integrate cognitive, sensory, and affective accessibility criteria from the earliest design stages. This involves adapting interfaces, revising language, interaction formats, response times, and providing alternative communication channels.

Moreover, the potential of AI as an emotional support resource should not be overlooked. While these technologies cannot replace professional mental health interventions, they can play an important complementary role—serving as a bridge to specialized services or offering everyday companionship. For this to be beneficial for students with disabilities, interactions with AI must not be perceived as additional sources of stress or exclusion. In this sense, truly empathetic AI must necessarily be accessible AI.

Finally, the findings of this study open multiple avenues for future research. It is essential to examine differences by disability type, since the experience of a student with a visual impairment is not comparable to that of a student with a psychosocial or cognitive disability. Additional variables such as technological self-efficacy, trust in AI, or social support should also be included, as they can significantly influence the relationship between use, perception, and satisfaction. Longitudinal studies would further help capture changes over time, offering a more dynamic perspective on technology appropriation processes.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that artificial intelligence is perceived as a useful resource by university students with and without disabilities, both in its informational and emotional support dimensions. However, differences observed in perceived usefulness and frequency of use highlight the existence of significant barriers limiting equitable adoption of these technologies.

The positive relationship identified between perceived usefulness and frequency of use reinforces the importance of improving user experience to foster effective adoption. Future strategies should focus on eliminating technical and design obstacles, fostering inclusion from the development stage, and promoting a technological culture sensitive to functional diversity.

To advance inclusive applications of AI, future research should embrace interdisciplinary approaches, account for diverse user profiles, and explore psychological, technological, and social variables influencing AI use and perceptions. In this way, the opportunities offered by AI can be ensured to empower users rather than becoming new forms of exclusion.

Author Contributions

RS: FGC, and CL conceptualized the study. CL and JGC curated the data. RS and CL conducted formal analysis. RS, FGC, and JGC carried out the investigation. RS and FGC developed the methodology. RS and FGC administered the project and provided resources. JGC handled software development. FGC and RS supervised the work. RS and JGC validated the data and results. CL was responsible for visualization. RS and CL wrote the original draft, and FGC and JGC contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Alicante (protocol code UA-2025 -09-22_2).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Mitchell, T. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. National Science Foundation; 2021. Disponible en: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/27644/AI-work-public-release-slides.pdf.

- Franganillo, J. La inteligencia artificial generativa y su impacto en la creación de contenidos mediáticos. Methaodos Rev Cienc Soc. 2023, 11, m231102a10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, PP. What Things Do: Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design; University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, M.; Xu, S.; Liu, H.; Zahid, H. Generative Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT-4) and Social Media Impact on Academic Performance and Psychological Well-Being in China’s Higher Education. Eur J Educ. 2025, 60, e12835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. Changes in Public Perception of ChatGPT: A Text Mining Perspective Based on Social Media. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2025, 41, 8265–8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Liu, Y.; Singh, K. Artificial intelligence in education: Challenges and ethical implications of adaptive learning. Comput Educ Rev. 2023, 39, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Park, Y.; Wang, H. The mediating effect of user satisfaction and the moderated mediating effect of AI anxiety on the relationship between perceived usefulness and subscription payment intention. J Retail Consum Serv. 2025, 84, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, F.; Doherty, A.; Lacey, G. Using Artificial Intelligence in Infection Prevention. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2020, 12, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Tan, S.; Yang, L.; Lei, J. Preparing for AI-enhanced education: Conceptualizing and empirically examining teachers’ AI readiness. Comput Human Behav. 2023, 146, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Chatterjee, S.; Mariani, M. Applications of generative AI. Technovation. 2024, 133, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS (WHO). La inteligencia artificial y la inclusión de las personas con discapacidad. 2022. Disponible en: https://unric.org/es/resumen-de-la-onu-sobre-la-inteligencia-artificial-y-la-inclusion-de-las-personas-con-discapacidad/.

- Alper, S.; Raharinirina, S. Assistive Technology for Individuals with Disabilities: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. J Spec Educ Technol. 2021, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguelles, E. Ventajas y desventajas del uso de la Inteligencia Artificial en el ciclo de las políticas públicas. Acta Univ. 2023, 33, e3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñacoba, A.; Muñoz, A.; Parra, L.; González, C. Afrontando la exclusión y la brecha digital mediante un uso humano de las TIC. Cuad Pensam. 2023, 36, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, L.; Rodríguez, L.; Herrero, M.; Veloso, A. Nuevas tecnologías aplicadas a la inclusión. ICONO 14 Rev Cient Comun Tecnol Emerg. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.; Montesdeoca, D.; Robles, A.; Vera, R. Inclusión y Diversidad: Innovaciones Tecnológicas. Rev Social Fronteriza. 2024, 4, e45476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotán, A.; Márquez, J.; Álvarez, K.; Gallardo, J. Recursos tecnológicos y formación docente. Eur Public Soc Innov Rev. 2024, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Screpnik, C. Tecnologías digitales en la educación inclusiva. UTE Teach Technol. 2024, 2, e3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonschot, M.; de Witte, L.; Reichrath, E.; Buntinx, W.; Curfs, L. Community participation of people with an intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009, 53, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaño, M.; Duarte, N. Una revisión sistemática del uso de la inteligencia artificial en la educación. Rev Colomb Cir. 2024, 39, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, X.; Díaz, F. Integrating generative AI in knowledge building. Comput Educ Artif Intell. 2023, 5, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, F.; Hulgo, J.; Molina, S.; Sánchez, N.; Núñez, A. Educación Inclusiva: Recursos Tecnológicos. Digital Publisher CEIT. 2025, 10, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).