Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

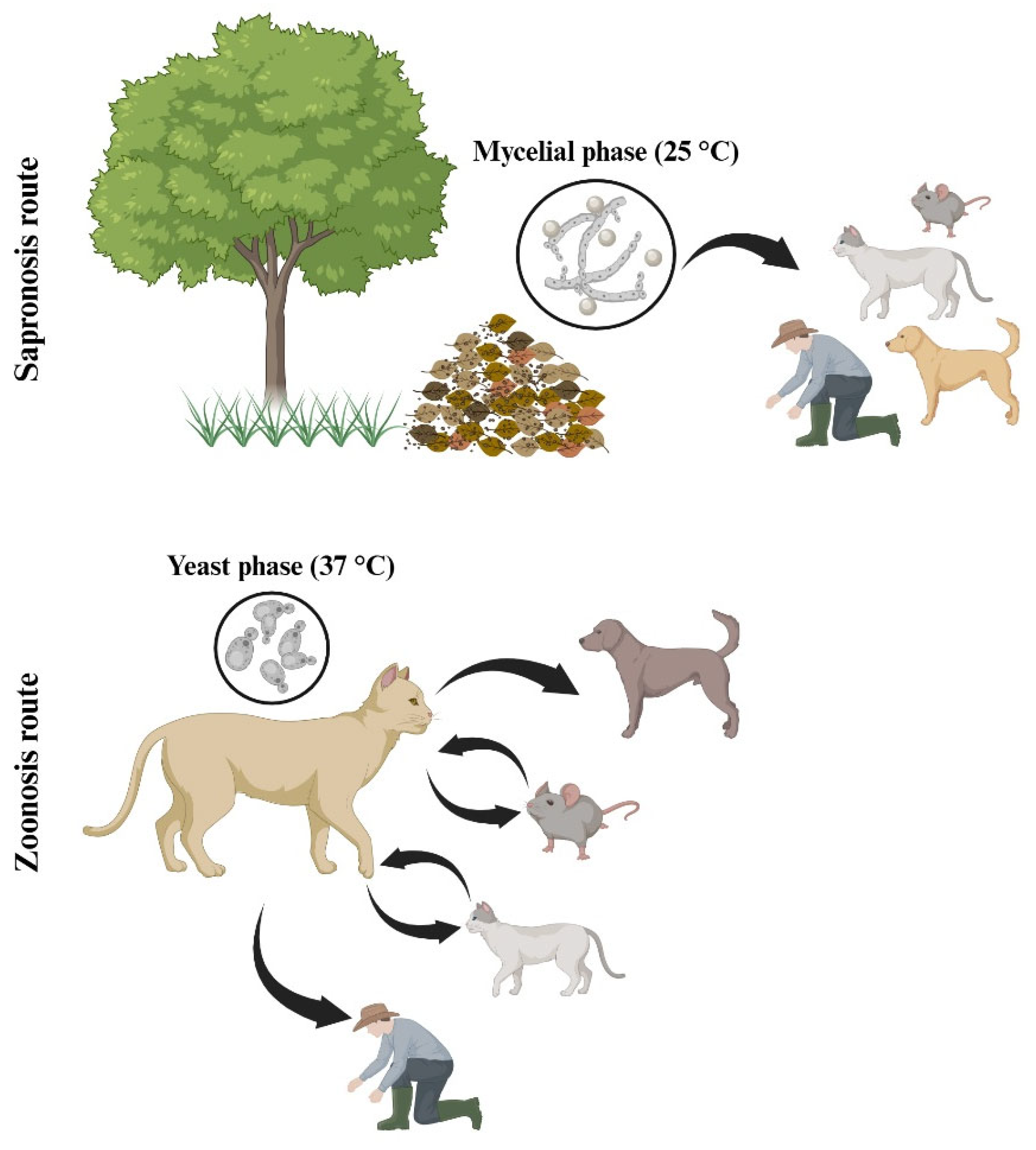

Sporothrix schenckii is a thermodimorphic fungus and one of the main etiological agents of sporotrichosis, a globally distributed subcutaneous mycosis that primarily affects the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and lymphatic system. Historically regarded as the classical species within the Sporothrix pathogenic clade, S. schenckii remains a clinically relevant pathogen and an important biological model for studying fungal dimorphism, virulence, and host–pathogen interactions. Major virulence factors include melanin production, thermotolerance, hydrolytic enzymes, and adhesins, all of which contribute to its survival and dissemination within the host. Clinically, S. schenckii causes a broad spectrum of manifestations ranging from fixed and lymphocutaneous cutaneous forms to disseminated and extracutaneous infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. This species exhibits a cosmopolitan distribution with endemic foci in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, and can be transmitted through both sapronotic and zoonotic routes. Diagnosis relies on fungal isolation, molecular identification, and histopathological examination, whereas treatment mainly involves itraconazole, potassium iodide, and amphotericin B for severe cases. This review integrates current knowledge on the biology, virulence, immune response, epidemiology, and treatment of S. schenckii, providing an updated overview of its significance as a medically important fungal pathogen with global relevance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biological Aspects

General Aspects

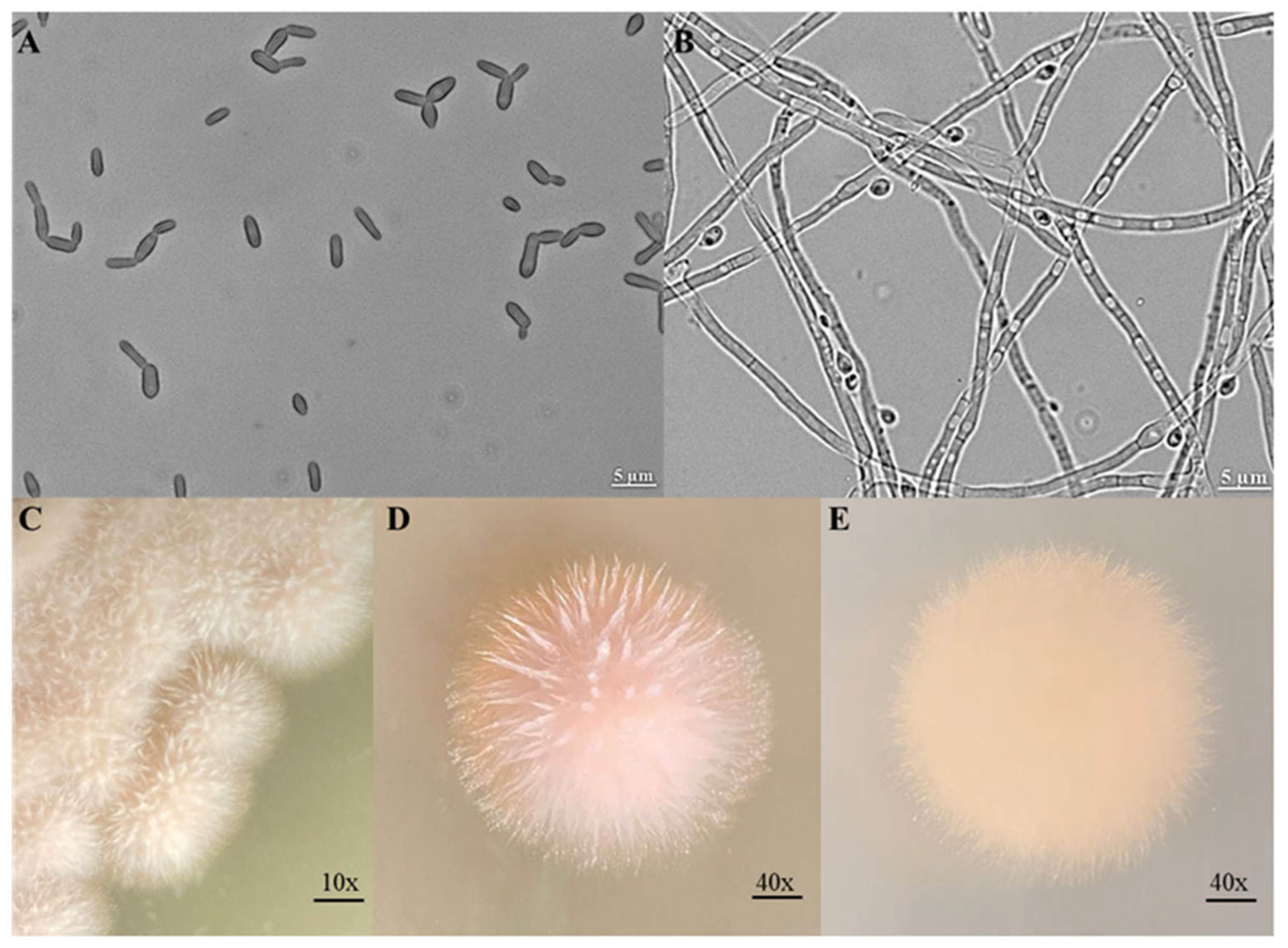

Morphology

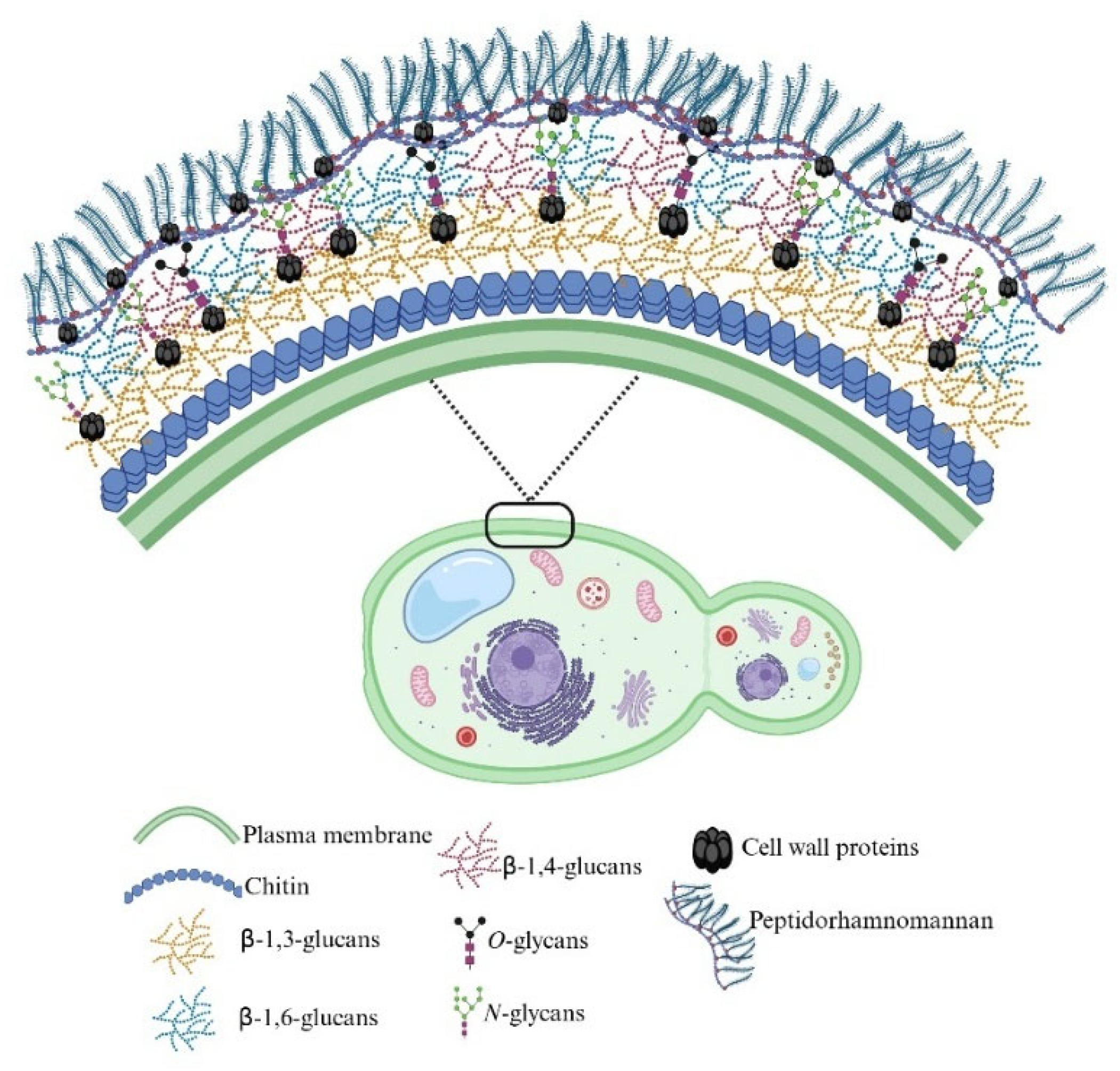

Cell Wall

Genome

3. Virulence Factors

4. Immune Response Against S. schenckii

5. Sporotrichosis Associated with Sporothrix schenckii

Domestic Animals’ Infection by Sporothrix schenckii

6. Identification and Diagnostic

7. Treatment

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Bonifaz, A. Sporothrix and Sporotrichosis. In Current Progress in Medical Mycology, Mora-Montes, H.M., Lopes-Bezerra, L.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 309–331. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Romero, E.; Reyes-Montes M del, R.; Perez-Torres, A.; Ruiz-Baca, E.; Villagomez-Castro, J.C.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Flores-Carreon, A.; Toriello, C. Sporothrix schenckii complex and sporotrichosis, an emerging health problem. Future Microbiol 2011, 6, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Beer, Z.W.; Duong, T.A.; Wingfield, M.J. The divorce of Sporothrix and Ophiostoma: solution to a problematic relationship. Stud Mycol 2016, 83, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Bonifaz, A.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Mochizuki, T.; Li, S. Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol 2015, 53, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Montes, H.M.; Dantas Ada, S.; Trujillo-Esquivel, E.; de Souza Baptista, A.R.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M. Current progress in the biology of members of the Sporothrix schenckii complex following the genomic era. FEMS Yeast Res 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchecopaz, A.N.; Lanza, N.; Toscanini, M.A.; Devoto, T.B.; Pola, S.J.; Daneri, G.L.; Iovannitti, C.A.; Cuestas, M.L. Sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis in Argentina: Case report, molecular identification and in vitro susceptibility pattern to antifungal drugs. J Mycol Med 2020, 30, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, M.O.; Poester, V.R.; Trápaga, M.R.; Stevens, D.A. Sporothrix brasiliensis: epidemiology, therapy, and recent developments. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Montes, H.M. Special Issue “Sporothrix and Sporotrichosis 2.0”. J Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremião, I.D.F.; Martins da Silva da Rocha, E.; Montenegro, H.; Carneiro, A.J.B.; Xavier, M.O.; de Farias, M.R.; Monti, F.; Mansho, W.; de Macedo Assunção Pereira, R.H.; Pereira, S.A.; et al. Guideline for the management of feline sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis and literature revision. Braz J Microbiol 2021, 52, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T.C. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 165rv113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Montes, H.M. Special Issue “Sporothrix and Sporotrichosis”. J Fungi (Basel) 2018, 4, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Castro, R.; Pinto-Almazán, R.; Arenas, R.; Sánchez-Cárdenas, C.D.; Espinosa-Hernández, V.M.; Sierra-Maeda, K.Y.; Conde-Cuevas, E.; Juárez-Durán, E.R.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Carrillo-Casas, E.M.; et al. Epidemiology of clinical sporotrichosis in the Americas in the last ten years. J Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, M.D.; Batista-Duharte, A.; Portuondo, D.; Quinello, C.; Bonne-Hernández, R.; Carlos, I.Z. Sporothrix schenckii complex biology: environment and fungal pathogenicity. Microbiology (Reading) 2014, 160, 2352–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimon, R.; Cano, J.; Gené, J.; Sutton, D.A.; Kawasaki, M.; Guarro, J. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol 2007, 45, 3198–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Barros, M.B.; Schubach, A.O.; de-Vasconcellos Carvalhaes De-Oliveira, R.; Martins, E.B.; Teixeira, J.L.; Wanke, B. Treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis with Itraconazole—Study of 645 patients. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orofino-Costa, R.; Macedo, P.M.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol 2017, 92, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; de Hoog, G.S.; de Cássia Pires, D.; Brihante, R.S.; Sidrim, J.J.; Gadelha, M.F.; Colombo, A.L.; de Camargo, Z.P. Genetic diversity and antifungal susceptibility profiles in causative agents of sporotrichosis. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamez-Castrellón, A.K.; Romeo, O.; García-Carnero, L.C.; Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Virulence factors in Sporothrix schenckii, one of the causative agents of sporotrichosis. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2020, 21, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hektoen, L.; Perkins, C.F. Refractory subcutaneous abscesses caused by Sporothrix schenckii. A new pathogenic fungus. J Exp Med 1900, 5, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marimon, R.; Gené, J.; Cano, J.; Guarro, J. Sporothrix luriei: a rare fungus from clinical origin. Med Mycol 2008, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.B.d.L.; de Almeida Paes, R.; Schubach, A.O. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011, 24, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Zhang, Y.; Nino-Vega, G.; Rodrigues, A.M.; de Camargo, Z.P.; de Hoog, S. Sporotrichosis between 1898 and 2017: The evolution of knowledge on a changeable disease and on emerging etiological agents. Med Mycol 2018, 56, S126–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasamoelina, T.; Maubon, D.; Raharolahy, O.; Razanakoto, H.; Rakotozandrindrainy, N.; Rakotomalala, F.A.; Bailly, S.; Sendrasoa, F.; Ranaivo, I.; Andrianarison, M.; et al. Sporotrichosis in the highlands of Madagascar, 2013-2017(1). Emerg Infect Dis 2019, 25, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovikkai, D.; Maitrisathit, W.; Srisuttiyakorn, C.; Vanichanan, J.; Thammahong, A.; Suankratay, C. Sporotrichosis: the case series in Thailand and literature review in Southeast Asia. Med Mycol Case Rep 2020, 27, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Schubach, A.; Costa, R.O. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2006, 78, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Caban, J.; Gonzalez-Velazquez, W.; Perez-Sanchez, L.; Gonzalez-Mendez, R.; Rodriguez-del Valle, N. Calcium/calmodulin kinase1 and its relation to thermotolerance and HSP90 in Sporothrix schenckii: an RNAi and yeast two-hybrid study. BMC Microbiol 2011, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentín-Berríos, S.; González-Velázquez, W.; Pérez-Sánchez, L.; González-Méndez, R.; Rodríguez-Del Valle, N. Cytosolic phospholipase A2: a member of the signalling pathway of a new G protein alpha subunit in Sporothrix schenckii. BMC Microbiol 2009, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Jiménez, D.; Pérez-García, L.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.; Mora-Montes, H. Role of the fungal cell wall in pathogenesis and antifungal resistance. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2012, 6, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carnero, L.C.; Salinas-Marín, R.; Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Wrobel, K.; Wrobel, K.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Niño-Vega, G.A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. The Heat shock protein 60 and Pap1 participate in the Sporothrix schenckii-host interaction. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Bezerra, L.M. Sporothrix schenckii cell wall peptidorhamnomannans. Frontiers in Microbiology 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gaviria, M.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Baptista, A.R.S.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Silencing of MNT1 and PMT2 shows the importance of O-linked glycosylation during the Sporothrix schenckii-host interaction. J Fungi (Basel) 2025, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ramírez, L.A.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Márquez-Márquez, A.; Vargas-Macías, A.P.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Silencing of ROT2, the encoding gene of the endoplasmic reticulum glucosidase II, affects the cell wall and the Sporothrix schenckii-host interaction. J Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Casas-Flores, S.; de Almeida, J.R.F.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; López-Ramírez, L.A.; Jannuzzi, G.P.; Trujillo-Esquivel, E.; Estrada-Mata, E.; Almeida, S.R.; Franco, B.; et al. Silencing of OCH1 unveils the role of Sporothrix schenckii N-linked glycans during the host-fungus interaction. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ramírez, L.A.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Silencing of Sporothrix schenckii GP70 reveals its contribution to fungal adhesion, virulence, and the host-fungus interaction. J Fungi (Basel) 2024, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.A.; Kubitschek-Barreira, P.H.; Teixeira, P.A.C.; Sanches, G.F.; Teixeira, M.M.; Quintella, L.P.; Almeida, S.R.; Costa, R.O.; Camargo, Z.P.; Felipe, M.S.S.; et al. Differences in cell morphometry, cell wall topography and Gp70 expression correlate with the virulence of Sporothrix brasiliensis clinical isolates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Kubitschek-Barreira, P.H.; Fernandes, G.F.; de Almeida, S.R.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; de Camargo, Z.P. Immunoproteomic analysis reveals a convergent humoral response signature in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. J Proteomics 2015, 115, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; García-Carnero, L.C.; Kubitschek-Barreira, P.H.; Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Belmonte-Vázquez, J.L.; de Almeida, J.R.; A, J.G.-I.; Curty, N.; Villagómez-Castro, J.C.; Peña-Cabrera, E.; et al. Analysis of some immunogenic properties of the recombinant Sporothrix schenckii Gp70 expressed in Escherichia coli. Future Microbiol 2019, 14, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Clavijo-Giraldo, D.M.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; García-Carnero, L.C.; López-Ramírez, L.A.; Niño-Vega, G.A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Influences of the culturing media in the virulence and cell wall of Sporothrix schenckii, Sporothrix brasiliensis, and Sporothrix globosa. J Fungi (Basel) 2020, 6, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos-Duno, H.L.; Barreto, L.A.; Alvarez-Aular, Á.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; Franco, B.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Niño-Vega, G.A. Comparison of cell wall polysaccharide composition and structure between strains of Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 726958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Walker, L.A.; Niño-Vega, G.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Neves, G.W.P.; Villalobos-Duno, H.; Barreto, L.; Garcia, K.; Franco, B.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; et al. Cell walls of the dimorphic fungal pathogens Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis exhibit bilaminate structures and sloughing of extensive and intact layers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006169–e0006169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; Pérez-García, L.A.; Mellado-Mojica, E.; López, M.G.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Lópes-Bezerra, L.M.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto and Sporothrix brasiliensis are differentially recognized by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.M.; de Almeida, L.G.; Kubitschek-Barreira, P.; Alves, F.L.; Kioshima, E.S.; Abadio, A.K.; Fernandes, L.; Derengowski, L.S.; Ferreira, K.S.; Souza, R.C.; et al. Comparative genomics of the major fungal agents of human and animal sporotrichosis: Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, B.H.; Ramírez-Prado, J.H.; Neves, G.W.P.; Torrado, E.; Sampaio, P.; Felipe, M.S.S.; Vasconcelos, A.T.; Goldman, G.H.; Carvalho, A.; Cunha, C.; et al. Ploidy determination in the pathogenic fungus Sporothrix spp. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 284. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rementeria, A.; López-Molina, N.; Ludwig, A.; Vivanco, A.B.; Bikandi, J.; Pontón, J.; Garaizar, J. Genes and molecules involved in Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Rev Iberoam Micol 2005, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.A.C.; de Castro, R.A.; Nascimento, R.C.; Tronchin, G.; Pérez Torres, A.; Lazéra, M.; de Almeida, S.R.; Bouchara, J.-P.; Loureiro y Penha, C.V.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M. Cell surface expression of adhesins for fibronectin correlates with virulence in Sporothrix schenckii. Microbiology 2009, 155, 3730–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Paes, R.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Oliveira, M.M.E.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. Phenotypic characteristics associated with virulence of clinical isolates from the Sporothrix complex. BioMed Res Int 2015, 2015, 212308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, O.C.; Figueiredo, C.C.; Pereira, B.A.; Coelho, M.G.; Morandi, V.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M. Adhesion of the human pathogen Sporothrix schenckii to several extracellular matrix proteins. Braz J Med Biol Res 1999, 32, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, O.C.; Bouchara, J.P.; Renier, G.; Marot-Leblond, A.; Chabasse, D.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M. Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry analysis of fibronectin and laminin binding to Sporothrix schenckii yeast cells and conidia. Microb Pathog 2004, 37, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Baca, E.; Toriello, C.; Pérez-Torres, A.; Sabanero-López, M.; Villagómez-Castro, J.C.; López-Romero, E. Isolation and some properties of a glycoprotein of 70 kDa (Gp70) from the cell wall of Sporothrix schenckii involved in fungal adherence to dermal extracellular matrix. Med Mycol 2009, 47, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, S.R. Therapeutic monoclonal antibody for sporotrichosis. Front Microbiol 2012, 3, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Rosa, D.; Gezuele, E.; Calegari, L.; Goñi, F. Excretion-secretion products and proteases from live Sporothrix schenckii yeast phase: immunological detection and cleavage of human IgG. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2009, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Aviles, L.; Valentin-Berrios, S.; Gonzalez-Mendez, R.R.; Rodriguez-Del Valle, N. Functional, genetic and bioinformatic characterization of a calcium/calmodulin kinase gene in Sporothrix schenckii. BMC Microbiol 2007, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvizu-Rubio, V.J.; García-Carnero, L.C.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Moonlighting proteins in medically relevant fungi. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, R. The INT1 of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol 1998, 6, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Lopez, R.; Park, H.; Myers, C.L.; Gil, C.; Filler, S.G. Candida albicans Ecm33p is important for normal cell wall architecture and interactions with host cells. Eukaryot Cell 2006, 5, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandini, S.; Stringaro, A.; Arancia, S.; Colone, M.; Mondello, F.; Murtas, S.; Girolamo, A.; Mastrangelo, N.; De Bernardis, F. The MP65 gene is required for cell wall integrity, adherence to epithelial cells and biofilm formation in Candida albicans. BMC Microbiology 2011, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lü, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Zhou, H.; Yan, J.; Du, T.; Jin, C. N-Glycosylation of Gel1 or Gel2 is vital for cell wall β-glucan synthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lee, M.J.; Solis, N.V.; Phan, Q.T.; Swidergall, M.; Ralph, B.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Sheppard, D.C.; Filler, S.G. Aspergillus fumigatus CalA binds to integrin α(5)β(1) and mediates host cell invasion. Nat Microbiol 2016, 2, 16211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, N.; Latgé, J.P.; Mouyna, I. Members of glycosyl-hydrolase family 17 of A. fumigatus differentially affect morphogenesis. J Fungi (Basel) 2018, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, B.R.; Zuyderduyn, S.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Marra, M.; Jones, S.J.; Perfect, J.R.; Kronstad, J. Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during experimental cryptococcal meningitis. Eukaryot Cell 2003, 2, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilhante, R.S.N.; de Aguiar, F.R.M.; da Silva, M.L.Q.; de Oliveira, J.S.; de Camargo, Z.P.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Pereira, V.S.; Serpa, R.; Castelo-Branco, D.; Correia, E.E.M.; et al. Antifungal susceptibility of Sporothrix schenckii complex biofilms. Med Mycol 2018, 56, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Herrera, R.; Flores-Villavicencio, L.L.; Pichardo-Molina, J.L.; Castruita-Domínguez, J.P.; Aparicio-Fernández, X.; Sabanero López, M.; Villagómez-Castro, J.C. Analysis of biofilm formation by Sporothrix schenckii. Med Mycol 2021, 59, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, G.M.P.; Borba-Santos, L.P.; Vila, T.; Ferreira Gremião, I.D.; Pereira, S.A.; De Souza, W.; Rozental, S. Sporothrix spp. biofilms impact in the zoonotic transmission route: feline claws associated biofilms, itraconazole tolerance, and potential repurposing for miltefosine. Pathogens 2022, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Hou, B.; Zhang, Z. Map of dimorphic switching-related signaling pathways in Sporothrix schenckii based on its transcriptome. Mol Med Rep 2021, 24, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Zhang, X.; Gao, S.; You, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L. Transcriptome analysis of dimorphic fungus Sporothrix schenckii exposed to temperature stress. Int Microbiol 2021, 24, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hou, B.; Wu, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Han, S. Two-component histidine kinase DRK1 is required for pathogenesis in Sporothrix schenckii. Mol Med Rep 2018, 17, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Hgc1, a novel hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein regulates Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis. Embo j 2004, 23, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebaara, B.W.; Langford, M.L.; Navarathna, D.H.; Dumitru, R.; Nickerson, K.W.; Atkin, A.L. Candida albicans Tup1 is involved in farnesol-mediated inhibition of filamentous-growth induction. Eukaryot Cell 2008, 7, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornitzer, D. Regulation of Candida albicans Hyphal Morphogenesis by Endogenous Signals. J Fungi (Basel) 2019, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magditch, D.A.; Liu, T.B.; Xue, C.; Idnurm, A. DNA mutations mediate microevolution between host-adapted forms of the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, e1002936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, B.J.; Pham, T.; Xie, X.; Ristow, L.C.; Krysan, D.J.; Lin, X. The RAM signaling pathway links morphology, thermotolerance, and CO(2) tolerance in the global fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Elife 2022, 11, e82563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnie, J.P.; Carter, T.L.; Hodgetts, S.J.; Matthews, R.C. Fungal heat-shock proteins in human disease. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2006, 30, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, T.; Yu, C.; Sun, S. Candida albicans heat shock proteins and Hsps-associated signaling pathways as potential antifungal targets. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabri, J.; Rocha, M.C.; Fernandes, C.M.; Campanella, J.E.M.; Cunha, A.F.D.; Del Poeta, M.; Malavazi, I. The heat shock transcription factor HsfA plays a role in membrane lipids biosynthesis connecting thermotolerance and unsaturated fatty acid metabolism in Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0162723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabri, J.H.T.M.; Rocha, M.C.; Fernandes, C.M.; Persinoti, G.F.; Ries, L.N.A.; Cunha, A.F.d.; Goldman, G.H.; Del Poeta, M.; Malavazi, I. The heat shock transcription factor HsfA is essential for thermotolerance and regulates cell wall integrity in Aspergillus fumigatus. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havel, V.E.; Wool, N.K.; Ayad, D.; Downey, K.M.; Wilson, C.F.; Larsen, P.; Djordjevic, J.T.; Panepinto, J.C. Ccr4 promotes resolution of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response during host temperature adaptation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell 2011, 10, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polke, M.; Hube, B.; Jacobsen, I.D. Candida survival strategies. Adv Appl Microbiol 2015, 91, 139–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanero López, M.; Flores Villavicencio, L.L.; Soto Arredondo, K.; Barbosa Sabanero, G.; Villagómez-Castro, J.C.; Cruz Jiménez, G.; Sandoval Bernal, G.; Torres Guerrero, H. Proteases of Sporothrix schenckii: Cytopathological effects on a host-cell model. Rev Iberoam Micol 2018, 35, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carissimi, M.; Stopiglia, C.D.O.; Souza, T.; Corbellini, V.A.; Scroferneker, M. Comparison of lipolytic activity of Sporothrix schenckii strains utilizing olive oil-rhodamine B and tween 80. Tecno-Lógica 2007, 11, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi, R.; Sanada, T.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H. Isolation and properties of extracellular proteinases from Sporothrix schenckii. J Bacteriol 1987, 169, 4104–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gácser, A.; Trofa, D.; Schäfer, W.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Targeted gene deletion in Candida parapsilosis demonstrates the role of secreted lipase in virulence. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 3049–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, D.M.; Yang, N.; Wang, W.K.; Shen, Y.F.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.H. A novel cold-active lipase from Candida albicans: cloning, expression and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12, 3950–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.; Borelli, C.; Korting, H.C.; Hube, B. Hydrolytic enzymes as virulence factors of Candida albicans. Mycoses 2005, 48, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, M.A.K.; de Almeida, J.R.F.; Jannuzzi, G.P.; Cronemberger-Andrade, A.; Torrecilhas, A.C.T.; Moretti, N.S.; da Cunha, J.P.C.; de Almeida, S.R.; Ferreira, K.S. Extracellular vesicles from Sporothrix brasiliensis are an important virulence factor that induce an increase in fungal burden in experimental sporotrichosis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossato, L.; Moreno, L.F.; Jamalian, A.; Stielow, B.; de Almeida, S.R.; de Hoog, S.; Freeke, J. Proteins potentially involved in immune evasion strategies in Sporothrix brasiliensis elucidated by ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry. mSphere 2018, 3, e00514–00517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, E.S. Pathogenic roles for fungal melanins. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000, 13, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xia, Y. Melanin in fungi: advances in structure, biosynthesis, regulation, and metabolic engineering. Microbial Cell Factories 2024, 23, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Paes, R.; Figueiredo-Carvalho, M.H.G.; Brito-Santos, F.; Almeida-Silva, F.; Oliveira, M.M.E.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. Melanins protect Sporothrix brasiliensis and Sporothrix schenckii from the antifungal effects of terbinafine. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0152796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris-Jones, R.; Youngchim, S.; Gomez, B.L.; Aisen, P.; Hay, R.J.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Casadevall, A.; Hamilton, A.J. Synthesis of melanin-like pigments by Sporothrix schenckii in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect Immun 2003, 71, 4026–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.F.; dos Santos, P.O.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Sasaki, A.A.; Burger, E.; de Camargo, Z.P. Characterization of virulence profile, protein secretion and immunogenicity of different Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto isolates compared with S. globosa and S. brasiliensis species. Virulence 2013, 4, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Hernández, A.K.; Gómez-Gaviria, M.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Differential recognition of clinically relevant Sporothrix species by human granulocytes. J Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenardon, M.D.; Munro, C.A.; Gow, N.A. Chitin synthesis and fungal pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 2010, 13, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alvarez, J.A.; Perez-Garcia, L.A.; Flores-Carreon, A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. The immune response against Candida spp. and Sporothrix schenckii. Rev Iberoam Micol 2014, 31, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, T.N.; Fierer, J. Innate immune receptors and defense against primary pathogenic fungi. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gaviria, M.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; García-Carnero, L.C.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Differential recognition of Sporothrix schenckii, Sporothrix brasiliensis, and Sporothrix globosa by human monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. Infect Drug Resist 2023, 16, 4817–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kischkel, B.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.; Taborda, C.P.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Dos Santos, J.C.; Netea, M.G. Differential recognition and cytokine induction by the peptidorhamnomannan from Sporothrix brasiliensis and S. schenckii. Cell Immunol 2022, 378, 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamez-Castrellón, A.K.; van der Beek, S.L.; López-Ramírez, L.A.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Lozoya-Pérez, N.E.; van Sorge, N.M.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Disruption of protein rhamnosylation affects the Sporothrix schenckii-host interaction. Cell Surf 2021, 7, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Carnero, L.C.; Martínez-Duncker, I.; Gómez-Gaviria, M.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Differential recognition of clinically relevant Sporothrix species by human mononuclear cells. J Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Carnero, L.C.; Lozoya Pérez, N.E.; González Hernández, S.E.; Martínez Álvarez, J.A. Immunity and treatment of sporotrichosis. J Fungi (Basel) 2018, 4, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassá, M.F.; Saturi, A.E.; Souza, L.F.; Ribeiro, L.C.; Sgarbi, D.B.; Carlos, I.Z. Response of macrophage Toll-like receptor 4 to a Sporothrix schenckii lipid extract during experimental sporotrichosis. Immunology 2009, 128, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegranci, P.; de Abreu Ribeiro, L.C.; Ferreira, L.S.; Negrini Tde, C.; Maia, D.C.; Tansini, A.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Placeres, M.C.; Carlos, I.Z. The predominance of alternatively activated macrophages following challenge with cell wall peptide-polysaccharide after prior infection with Sporothrix schenckii. Mycopathologia 2013, 176, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, T.d.C.; Ferreira, L.S.; Alegranci, P.; Arthur, R.A.; Sundfeld, P.P.; Maia, D.C.G.; Spolidorio, L.C.; Carlos, I.Z. Role of TLR-2 and fungal surface antigens on innate immune response against Sporothrix schenckii. Immunol Invest 2013, 42, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassá, M.F.; Ferreira, L.S.; Ribeiro, L.C.; Carlos, I.Z. Immune response against Sporothrix schenckii in TLR-4-deficient mice. Mycopathologia 2012, 174, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.M.; Gow, N.A.; Brown, G.D. Pattern recognition: recent insights from Dectin-1. Curr Opin Immunol 2009, 21, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco Dde, L.; Nascimento, R.C.; Ferreira, K.S.; Almeida, S.R. Antibodies against Sporothrix schenckii enhance TNF-α production and killing by macrophages. Scand J Immunol 2012, 75, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Du, W.; Liang, Z.; Li, M.; Wu, R.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Huang, H. Chitin-rich heteroglycan from Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto potentiates fungal clearance in a mouse model of sporotrichosis and promotes macrophages phagocytosis. BMC Microbiol 2021, 21, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, D.C.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Ferreira, L.S.; Manente, F.A.; Portuondo, D.L.; Vellosa, J.C.; Polesi, M.C.; Batista-Duharte, A.; Carlos, I.Z. Response of cytokines and hydrogen peroxide to Sporothrix schenckii exoantigen in systemic experimental infection. Mycopathologia 2016, 181, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.S.; Neto, E.H.; Brito, M.M.; Silva, J.S.; Cunha, F.Q.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. Detrimental role of endogenous nitric oxide in host defence against Sporothrix schenckii. Immunology 2008, 123, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martinez, R.; Wheeler, M.; Guerrero-Plata, A.; Rico, G.; Torres-Guerrero, H. Biosynthesis and functions of melanin in Sporothrix schenckii. Infect Immun 2000, 68, 3696–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Beltran, S.; Perez-Torres, A.; Coronel-Cruz, C.; Torres-Guerrero, H. Phagocytic receptors on macrophages distinguish between different Sporothrix schenckii morphotypes. Microbes Infect 2012, 14, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miranda, L.H.M.; Santiago, M.A.; Frankenfeld, J.; Reis, E.G.D.; Menezes, R.C.; Pereira, S.A.; Gremião, I.D.F.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Conceição-Silva, F. Neutrophil oxidative burst profile is related to a satisfactory response to itraconazole and clinical cure in feline sporotrichosis. J Fungi (Basel) 2024, 10, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdan, F.F.; Faleiros, J.C.; Ferreira, L.S.; Monnazzi, L.G.; Maia, D.C.; Tansine, A.; Placeres, M.C.; Carlos, I.Z.; Santos-Junior, R.R. Dendritic cell are able to differentially recognize Sporothrix schenckii antigens and promote Th1/Th17 response in vitro. Immunobiology 2012, 217, 788–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uenotsuchi, T.; Takeuchi, S.; Matsuda, T.; Urabe, K.; Koga, T.; Uchi, H.; Nakahara, T.; Fukagawa, S.; Kawasaki, M.; Kajiwara, H.; et al. Differential induction of Th1-prone immunity by human dendritic cells activated with Sporothrix schenckii of cutaneous and visceral origins to determine their different virulence. Int Immunol 2006, 18, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgarbi, D.B.; da Silva, A.J.; Carlos, I.Z.; Silva, C.L.; Angluster, J.; Alviano, C.S. Isolation of ergosterol peroxide and its reversion to ergosterol in the pathogenic fungus Sporothrix schenckii. Mycopathologia 1997, 139, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remer, K.A.; Brcic, M.; Jungi, T.W. Toll-like receptor-4 is involved in eliciting an LPS-induced oxidative burst in neutrophils. Immunol Lett 2003, 85, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, J.R.; Kaihami, G.H.; Jannuzzi, G.P.; de Almeida, S.R. Therapeutic vaccine using a monoclonal antibody against a 70-kDa glycoprotein in mice infected with highly virulent Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. Med Mycol 2015, 53, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuondo, D.L.; Batista-Duharte, A.; Ferreira, L.S.; Martínez, D.T.; Polesi, M.C.; Duarte, R.A.; de Paula, E.S.A.C.; Marcos, C.M.; Almeida, A.M.; Carlos, I.Z. A cell wall protein-based vaccine candidate induce protective immune response against Sporothrix schenckii infection. Immunobiology 2016, 221, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba-Fierro, C.A.; Pérez-Torres, A.; López-Romero, E.; Cuéllar-Cruz, M.; Ruiz-Baca, E. Cell wall proteins of Sporothrix schenckii as immunoprotective agents. Revista Iberoamericana de Micología 2014, 31, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carnero, L.C.; Pérez-García, L.A.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; Reyes-Martínez, J.E.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Current trends to control fungal pathogens: exploiting our knowledge in the host-pathogen interaction. Infect Drug Resist 2018, 11, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz, A.; Vázquez-González, D. Diagnosis and treatment of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis: What are the options? Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hagen, F.; Stielow, B.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Samerpitak, K.; Zhou, X.; Feng, P.; Yang, L.; Chen, M.; Deng, S.; et al. Phylogeography and evolutionary patterns in Sporothrix spanning more than 14 000 human and animal case reports. Persoonia 2015, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; de Hoog, G.S.; de Camargo, Z.P. Sporothrix species causing outbreaks in animals and humans driven by animal-animal transmission. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremião, I.D.F.; Miranda, L.H.M.; Reis, E.G.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Pereira, S.A. Zoonotic epidemic of sporotrichosis: cat to human transmission. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabello, V.B.S.; Almeida, M.A.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R.; Almeida-Paes, R.; de Macedo, P.M.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. The historical burden of sporotrichosis in Brazil: a systematic review of cases reported from 1907 to 2020. Braz J Microbiol 2022, 53, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, N.P.; Maphanga, T.G.; Zulu, T.G.; Patel, J.; Walaza, S.; Jacobs, C.; Ebonwu, J.I.; Ntuli, S.; Naicker, S.D.; Thomas, J. An outbreak of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis among mine-workers in South Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0004096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, S.; Stephenson, I.; Jenkins, D.R.; Wiselka, M.J.; Johnson, E.M. Disseminated Sporothix schenckii in a patient with AIDS. J Infect 2005, 51, e73–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Vergara, M.L.; Maneira, F.R.; De Oliveira, R.M.; Santos, C.T.; Etchebehere, R.M.; Adad, S.J. Multifocal sporotrichosis with meningeal involvement in a patient with AIDS. Med Mycol 2005, 43, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.T.; de Castro, A.P.; Baby, C.; Werner, B.; Filus Neto, J.; Queiroz-Telles, F. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis in a patient with AIDS: report of a case. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2002, 35, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, H.L., Jr.; Lettnin, C.B.; Barbosa, J.L.; Dias, M.C. Spontaneous resolution of zoonotic sporotrichosis during pregnancy. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2009, 51, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, H.T.; Sullivan, E.; Crum-Cianflone, N.F. Sporotrichosis as an unusual case of osteomyelitis: A case report and review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep 2016, 11, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Tellez, I.; Deep, A.E.; Nolasco, D.; Holgado, W.; Bustamante, B. Sporotrichosis in Peru: description of an area of hyperendemicity. Clin Infect Dis 2000, 30, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Essayag, S.; Delgado, A.; Colella, M.T.; Landaeta-Nezer, M.E.; Rosello, A.; Perez de Salazar, C.; Olaizola, C.; Hartung, C.; Magaldi, S.; Velasquez, E. Epidemiology of sporotrichosis in Venezuela. Int J Dermatol 2013, 52, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, F.; Jakubovic, H.; Alabdulrazzaq, S.; Alavi, A. A case of sporotrichosis infection mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum and the role of tissue culture in diagnosis: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2020, 8, 2050313x20919600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriello, C.; Brunner-Mendoza, C.; Ruiz-Baca, E.; Duarte-Escalante, E.; Pérez-Mejía, A.; Del Rocío Reyes-Montes, M. Sporotrichosis in Mexico. Braz J Microbiol 2021, 52, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Acevedo, L.C.; Zuleta-González, M.C.; Gómez-Guzmán Ó, M.; Rúa-Giraldo Á, L.; Hernández-Ruiz, O.; McEwen-Ochoa, J.G.; Urán-Jiménez, M.E.; Arango-Arteaga, M.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; Evangelista de Oliveira, M.M.; et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Colombian clinical isolates of Sporothrix spp. Biomedica 2023, 43, 216-228. Biomedica 2023, 43, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Feng, P.; Hoog, G.S. Global ITS diversity in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. In Fungal Divers; 2013.

- Dooley, D.P.; Bostic, P.S.; Beckius, M.L. Spook house sporotrichosis: a point-source outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with hay bale props in a halloween haunted house. Archives of Internal Medicine 1997, 157, 1885–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz, A.; Morales-Peña, N.; Tirado-Sánchez, A.; Jiménez-Mendoza, D.R.; Treviño-Rangel, R.J.; González, G.M. Atypical sporotrichosis related to Sporothrix mexicana. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz, A.; Tirado-Sánchez, A.; Paredes-Solís, V.; Cepeda-Valdés, R.; González, G.M.; Treviño-Rangel, R.J.; Fierro-Arias, L. Cutaneous disseminated sporotrichosis: clinical experience of 24 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018, 32, e77–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Duncker, I.; Mayorga-Rodríguez, J.; Gómez-Gaviria, M.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.A.; Baruch-Martínez, D.A.; López-Ramírez, L.A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Phenotypic immunological profiling and antifungal susceptibility of Sporothrix schenckii clinical isolates from a hyperendemic region in western Mexico. Med Mycol 2025, 63, myaf073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushiro, R. Epidemiology and ecology of sporotrichosis in Japan. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 1984, 257, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieosilapatham, P.; Chuamanochan, M.; Chiewchavit, S.; Saikruatep, R.; Amornrungsun, E.; Preechasuth, K. Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto related to zoonotic transmission in Thailand. Med Mycol Case Rep 2023, 41, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Liu, Y.; Ning, Q.; Wu, S.; Su, S.; Zheng, D.; Ma, S.; Zou, J.; Yang, M.; Hu, D.; et al. A case of chronic wounds caused by Sporothrix schenckii infection was rapidly detected by metagenomic next generation sequencing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhong, M.; Gyawali, K.R.; Pan, W.; Xu, M.; Huang, H.; Huang, X. Current situation of sporotrichosis in China. Future Microbiol 2024, 19, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhan, P.; Jiang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Y.; Fan, X.; Sun, J.; de Hoog, S. Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of Sporothrix species in Jiangxi, central China. Med Mycol 2019, 57, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, K.I.; Sharma, N.L.; Kanga, A.K.; Mahajan, V.K.; Ranjan, N. Isolation of Sporothrix schenckii from the environmental sources of cutaneous sporotrichosis patients in Himachal Pradesh, India: results of a pilot study. Mycoses 2007, 50, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinprayoon, U.; Jermjutitham, M.; Tirakunwichcha, S.; Banlunara, W.; Tulvatana, W.; Chindamporn, A. Conjunctival sporotrichosis from cat to human: Case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2020, 20, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.M.; Tang, J.J.; Gill, P.; Chang, C.C.; Baba, R. Cutaneous sporotrichosis: a six-year review of 19 cases in a tertiary referral center in Malaysia. Int J Dermatol 2012, 51, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal Azam, N.K.; Selvarajah, G.T.; Santhanam, J.; Abdul Razak, M.F.; Ginsapu, S.J.; James, J.E.; Suetrong, S. Molecular epidemiology of Sporothrix schenkii isolates in Malaysia. Med Mycol 2020, 58, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismer, H.F.; Hull, P.R. Prevalence, epidemiology and geographical distribution of Sporothrix schenckii infections in Gauteng, South Africa. Mycopathologia 1997, 137, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, L.; Weber, R.J.; Puryear, S.B.; Bahrani, E.; Peluso, M.J.; Babik, J.M.; Haemel, A.; Coates, S.J. Disseminated cutaneous and osteoarticular sporotrichosis mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019, 6, ofz395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendrasoa, F.A.; Ranaivo, I.M.; Sata, M.; Razanakoto, N.H.; Andrianarison, M.; Ratovonjanahary, V.; Raharolahy, O.; Rakotoarisaona, M.; Rasamoelina, T.; Andrianarivelo, M.R.; et al. Osteoarticular sporotrichosis in an immunocompetent patient. Med Mycol Case Rep 2021, 32, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Mota, A.C.O.; Jesus, G.R.; Rocha, M.D.G.; Durço, D.; Rezende, L.; Silva, A.; Vilar, F.C.; Bollela, V.R.; Martinez, R. Disseminated sporotrichosis with osteoarticular involvement in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a case report. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2024, 57, e008092024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubach, T.M.; de Oliveira Schubach, A.; dos Reis, R.S.; Cuzzi-Maya, T.; Blanco, T.C.; Monteiro, D.F.; Barros, B.M.; Brustein, R.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; Fialho Monteiro, P.C.; et al. Sporothrix schenckii isolated from domestic cats with and without sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mycopathologia 2002, 153, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangkaew, L.; Yurayart, C.; Limsivilai, O.; Chen, C.; Kasorndorkbua, C. Cutaneous sporotrichosis in a stray cat from Thailand. Med Mycol Case Rep 2019, 23, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.S.; Kano, R. Feline sporotrichosis in Asia. Braz J Microbiol 2021, 52, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremião, I.D.; Menezes, R.C.; Schubach, T.M.; Figueiredo, A.B.; Cavalcanti, M.C.; Pereira, S.A. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med Mycol 2015, 53, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, L.; Gillett, S.; Ames, Y.; Krockenberger, M.; Malik, R. Zoonotic feline sporotrichosis: a small case cluster in Perth, Western Australia, and a review of previous feline cases from Australia. Aust Vet J 2024, 102, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.A.; Passos, S.R.; Silva, J.N.; Gremião, I.D.; Figueiredo, F.B.; Teixeira, J.L.; Monteiro, P.C.; Schubach, T.M. Response to azolic antifungal agents for treating feline sporotrichosis. Vet Rec 2010, 166, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, L.H.M.; Silva, J.N.; Gremião, I.D.F.; Menezes, R.C.; Almeida-Paes, R.; Dos Reis É, G.; de Oliveira, R.V.C.; de Araujo, D.; Ferreiro, L.; Pereira, S.A. Monitoring fungal burden and viability of Sporothrix spp. in skin lesions of cats for predicting antifungal treatment response. J Fungi (Basel) 2018, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mothé, G.; Reis, N.; Melivilu, C.; Junior, A.; Santos, C.; Dieckmann, A.; Dantas Machado, R.L.; Rocha, E.; Baptista, A. Ocular lesions in a domestic feline:: a closer look at the fungal pathogen Sporothrix brasiliensis. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science 2021, 58, e183219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubach, T.M.; Schubach, A.; Okamoto, T.; Barros, M.B.; Figueiredo, F.B.; Cuzzi, T.; Fialho-Monteiro, P.C.; Reis, R.S.; Perez, M.A.; Wanke, B. Evaluation of an epidemic of sporotrichosis in cats: 347 cases (1998-2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004, 224, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Cabo, J.F.; de las Heras Guillamon, M.; Latre Cequiel, M.V.; Garcia de Jalon Ciercoles, J.A. Feline sporotrichosis: a case report. Mycopathologia 1989, 108, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, R.; Okubo, M.; Siew, H.H.; Kamata, H.; Hasegawa, A. Molecular typing of Sporothrix schenckii isolates from cats in Malaysia. Mycoses 2015, 58, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, H.H. The current status of feline sporotrichosis in Malaysia. Med Mycol J 2017, 58, E107–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessee, I.; Barber, E.; Petro, E.; Lindemann, S.; Buss, B.; Santos, A.; Gade, L.; Lockhart, S.R.; Sexton, D.J.; Chiller, T.; et al. Sporotrichosis cluster in domestic cats and veterinary technician, Kansas, USA, 2022. Emerg Infect Dis 2024, 30, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Sato, H.; Watanabe, S.; Takahashi, H.; Koide, K.; Hasegawa, A. Sporothrix schenckii isolated from a cat in Japan. Mycoses 1996, 39, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara Wilka Leal Silva, M.A.M. , Pedro Henrique Marques Barrozo, Jacqueline da Silva Brito, Caio Cezar Nogueira de Souza, Marcely Karen Santos do Rosário, Caroliny do Socorro Brito Santos, Alzira Alcantara Mendes Queiroz Neta, Fernanda Monik Silva Martins, Leonildo Bento Galiza da Silva, Lívia Medeiros Neves Casseb, Andréa Maria Góes Negrão, Mylenna de Cássia Neves Guimarães, Andrea Viana da Cruz, Alexandre do Rosário Casseb. First report of fungal Sporothrix schenckii complex isolation from feline with possible zoonotic transmission in the city of Belém, Pará, Brazil: Case report. Research, Society and Development 2022, 11, e26311225551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubach, T.M.; Schubach, A.; Okamoto, T.; Barros, M.B.; Figueiredo, F.B.; Cuzzi, T.; Pereira, S.A.; Dos Santos, I.B.; Almeida Paes, R.; Paes Leme, L.R.; et al. Canine sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: clinical presentation, laboratory diagnosis and therapeutic response in 44 cases (1998-2003). Med Mycol 2006, 44, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafarchia, C.; Sasanelli, M.; Lia, R.P.; de Caprariis, D.; Guillot, J.; Otranto, D. Lymphocutaneous and nasal sporotrichosis in a dog from southern Italy: case report. Mycopathologia 2007, 163, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, P.G.; Figueiredo, A.B.F.; Gremião, I.D.F.; de Miranda, L.H.M.; da Silva Antonio, I.M.; Boechat, J.S.; de Sá Machado, A.C.; de Oliveira, M.M.E.; Pereira, S.A. Successful treatment of canine sporotrichosis with terbinafine: case reports and literature review. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prazeres Júnior, F.R.; Moreira, A.C.; Medeiros, N.O.; Carmo, M.C.C.; Lima, M.P.S. Sporotrichosis in guinea pig (Cavia porcellu) - case report]. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia 2024, 76, e13132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Zaini, F. Sporotrichosis in Iran: A mini review of reported cases in patients suspected to cutaneous leishmaniasis. Curr Med Mycol 2015, 1, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carolis, E.; Posteraro, B.; Sanguinetti, M. Old and new insights into Sporothrix schenckii complex biology and identification. Pathogens 2022, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.M.; Almeida-Paes, R.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Zancope-Oliveira, R.M. Molecular identification of the Sporothrix schenckii complex. Rev Iberoam Micol 2014, 31, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chung, W.H.; Hung, S.I.; Ho, H.C.; Wang, Z.W.; Chen, C.H.; Lu, S.C.; Kuo, T.T.; Hong, H.S. Detection of Sporothrix schenckii in clinical samples by a nested PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, R.; Miller, D.; Campos-Macias, P. Epidemiological data and molecular characterization (mtDNA) of Sporothrix schenckii in 13 cases from Mexico. Int J Dermatol 2007, 46, 177–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criseo, G.; Romeo, O. Ribosomal DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of environmental Sporothrix schenckii strains: comparison with clinical isolates. Mycopathologia 2010, 169, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.M.; Sampaio, P.; Almeida-Paes, R.; Pais, C.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Zancope-Oliveira, R.M. Rapid identification of Sporothrix species by T3B fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50, 2159–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Li, F.; Gong, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, F. Development and evaluation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction for fast diagnosis of sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix globosa. Med Mycol 2020, 58, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.M.; Santos, C.; Sampaio, P.; Romeo, O.; Almeida-Paes, R.; Pais, C.; Lima, N.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. Development and optimization of a new MALDI-TOF protocol for identification of the Sporothrix species complex. Res Microbiol 2015, 166, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Gonçalves, S.S.; de Carvalho, J.A.; Borba-Santos, L.P.; Rozental, S.; Camargo, Z.P.d. Current progress on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of sporotrichosis and their future trends. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, V.K. Sporotrichosis: an overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol Res Pract 2014, 2014, 272376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, C.A.; Bustamante, B.; Chapman, S.W.; Pappas, P.G. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, L.M.; Soares, B.M.; de Assis Santos, D.; Da Silva Barros, M.E.; Hamdan, J.S. In vitro susceptibility of isolates of Sporothrix schenckii to amphotericin B, itraconazole, and terbinafine: comparison of yeast and mycelial forms. Can J Microbiol 2006, 52, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borba-Santos, L.P.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Gagini, T.B.; Fernandes, G.F.; Castro, R.; de Camargo, Z.P.; Nucci, M.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Ishida, K.; Rozental, S. Susceptibility of Sporothrix brasiliensis isolates to amphotericin B, azoles, and terbinafine. Med Mycol 2015, 53, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.W.; Pappas, P.; Kauffmann, C.; Smith, E.B.; Dietze, R.; Tiraboschi-Foss, N.; Restrepo, A.; Bustamante, A.B.; Opper, C.; Emady-Azar, S.; et al. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy and safety of two doses of terbinafine (500 and 1000 mg day(-1)) in the treatment of cutaneous or lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis. Mycoses 2004, 47, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francesconi, G.; Francesconi do Valle, A.C.; Passos, S.L.; de Lima Barros, M.B.; de Almeida Paes, R.; Curi, A.L.; Liporage, J.; Porto, C.F.; Galhardo, M.C. Comparative study of 250 mg/day terbinafine and 100 mg/day itraconazole for the treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis. Mycopathologia 2011, 171, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Zaitz, C.; Framil, V.M.; Muramatu, L.H. Cutaneous sporotrichosis treatment with potassium iodide: a 24 year experience in São Paulo State, Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo 2011, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, P.M.; Lopes-Bezerra, L.M.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R.; Orofino-Costa, R. New posology of potassium iodide for the treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis: study of efficacy and safety in 102 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015, 29, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, B.; Campos, P.E. Endemic sporotrichosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2001, 14, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba-Santos, L.P.; Vila, T.; Rozental, S. Identification of two potential inhibitors of Sporothrix brasiliensis and Sporothrix schenckii in the Pathogen Box collection. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0240658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroonvuthiphong, V.; Bangphoomi, N. Therapeutic alternatives for sporotrichosis induced by wild-type and non-wild-type Sporothrix schenckii through in vitro and in vivo assessment of enilconazole, isavuconazole, posaconazole, and terbinafine. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoko, P.; Picard, J.; Howard, R.L.; Mampuru, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. In vivo antifungal effect of Combretum and Terminalia species extracts on cutaneous wound healing in immunosuppressed rats. Pharm Biol 2010, 48, 621–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.F.; de Siqueira Hoagland, B.; do Valle, A.C.; Fraga, B.B.; de Barros, M.B.; de Oliveira Schubach, A.; de Almeida-Paes, R.; Cuzzi, T.; Rosalino, C.M.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; et al. Sporotrichosis in HIV-infected patients: report of 21 cases of endemic sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Med Mycol 2012, 50, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Almazán, R.; Sandoval-Navarro, K.A.; Damián-Magaña, E.J.; Arenas, R.; Fuentes-Venado, C.E.; Zárate-Segura, P.B.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C. Relationship of sporotrichosis and infected patients with HIV-AIDS: an actual systematic review. J Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, J.R.; Santiago, K.L.; Kaihami, G.H.; Maranhão, A.Q.; de Macedo Brígido, M.; de Almeida, S.R. The efficacy of humanized antibody against the Sporothrix antigen, gp70, in promoting phagocytosis and reducing disease burden. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, S.R. Advances in vaccine development against sporotrichosis. Curr Trop Med Rep 2019, 6, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Della Terra, P.P.; Gremião, I.D.; Pereira, S.A.; Orofino-Costa, R.; de Camargo, Z.P. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 813–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virulence factors | Organism | Protein |

S. schenckii (Locus tag) |

E-value* | Similarity (%)* |

| Adhesins | Candida albicans | Als 1-9 | No found | - | - |

| Eap1 | No found | - | - | ||

| Ecm33 | SPSK_05317 | 6e-46 | 73 | ||

| Hwp1 | No found | - | - | ||

| Iff4 | No found | - | - | ||

| Int1 | SPSK_07346 | 8e-52 | 50 | ||

| Mp65 | SPSK_05120 | 1e-38 | 74 | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | RodA RodB |

No found | - | - | |

| AspF2 | No found | - | - | ||

| CalA | SPSK_05470 | 2e-94 | 71 | ||

| Scw11 | SPSK_04001 | 3e-137 | 69 | ||

| Gel1 | SPSK_05276 | 0 | 70 | ||

| Gel2 | SPSK_04169 | 2e-159 | 99 | ||

| Mp1 | No found | - | - | ||

| AfCalAp | No found | - | - | ||

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Cfl1 | No found | - | - | |

| Cpl1 | No found | - | - | ||

| Mp98 | SPSK_03393 | 2e-24 | 44 | ||

| Biofilm | C. albicans | Bcr1 | SPSK_01505 | 2e-24 | 76 |

| Brg1 | SPSK_05129 | 1e-13 | 78 | ||

| Efg1 | SPSK_07078 | 1e-57 | 65 | ||

| Hsp90 | SPSK_08698 | 0 | 85 | ||

| Ndt80 | SPSK_09140 | 3e-09 | 37 | ||

| Rob1 | SPSK_03010 | 7e-08 | 54 | ||

| Csr1 | SPSK_08605 | 1e-33 | 57 | ||

| C. neoformans | Lac1 | SPSK_03091 | 3e-24 | 60 | |

| Ure1 | SPSK_00695 | 0 | 99 | ||

| Cap59 | SPSK_09241 | 5e-15 | 50 | ||

| Hydrolytic enzymes | C. albicans | Lip5-8 | SPSK_03375 | 1e-60 | 86 |

| Sap1-8 | SPSK_06273 | 2e-52 | 53 | ||

| Plb1-3 | SPSK_01063 | 4e-145 |

57 | ||

| A. fumigatus | Pep1 | SPSK_02149 | 0 | 60 | |

| Pep2 | SPSK_00526 | 0 | 85 | ||

| Ap1 | SPSK_07865 | 8e-94 | 97 | ||

| CtsD | SPSK_01559 | 6e-82 | 58 | ||

| PlaA | SPSK_02253 | 2e-136 | 50 | ||

| Dimorphism | C. albicans | Cph1 | SPSK_07311 |

3e-72 | 78 |

| Hgc1 | SPSK_05321 |

4e-21 | 42 | ||

| Nrg1 | SPSK_00519 |

1e-10 | 55 | ||

| Tup1 | SPSK_02314 | 1e-139 |

67 | ||

| C. neoformans | Mob2 | SPSK_01925 |

9e-44 |

57 | |

| Cbk1 | SPSK_06025 | 1e-178 |

68 | ||

| Tao3 | SPSK_02910 | 4e-129 |

44 | ||

| Sog2 | SPSK_03988 | 9e-113 |

51 | ||

| Thermotolerance | C. albicans | Hsp60 | SPSK_01586 | 0 | 87 |

| Hsp104 | SPSK_08586 | 0 | 65 | ||

| Ssa1 | SPSK_08625 | 0 | 88 | ||

| Ssb1 | SPSK_03121 | 0 | 87 | ||

| A. fumigatus | CrgA | SPSK_09995 | 6e-42 | 79 | |

| Sch9 | SPSK_10850 | 0 | 71 | ||

| Hsf1 | SPSK_08498 | 7e-96 | 48 | ||

| BiP/Kar2 | SPSK_04019 | 0 | 87 | ||

| Ssc70 | SPSK_03148 | 0 | 88 | ||

| Hsp88 | SPSK_00430 | 0 | 75 | ||

| BiP | SPSK_06078 | 0 | 69 | ||

| Lhs1/Orp150 | SPSK_02198 | 0 | 61 | ||

| Hsp90 | SPSK_08698 | 0 | 91 | ||

| C. neoformans | Ccr4 | SPSK_07136 |

2e-141 |

53 | |

| Immune evasion | C. albicans | Hgt1 | SPSK_06192 | 7e-116 | |

| Hmx1 | No found | - | - | ||

| Msb2 | SPSK_07127 |

9e-18 |

44 | ||

| Pra1 | No found | - | - | ||

| Rbt5 | No found | - | - | ||

| Sit1 | SPSK_02970 | 5e-150 |

64 | ||

| A. fumigatus | Hyp1/RodA | No found | - | - | |

| Pksp/Alb1 | SPSK_00653 | 0 | 60 | ||

| C. neoformans | Rim101 | SPSK_07198 |

2e-36 |

70 | |

| Melanin production | A. fumigatus | Fet3 | SPSK_07279 | 0 | 68 |

| TilA | SPSK_04101 | 6e-168 |

62 | ||

| Dihydrogeodin/laccase | SPSK_07219 | 2e-99 |

46 | ||

| Cell wall synthesis | C. albicans | Fks1 | SPSK_01365 | 2e-79 | 78 |

| Dpm3 | SPSK_02816 | 2e-19 |

63 | ||

| Pmt2 | SPSK_08548 | 0 | 65 | ||

| A. fumigatus | ChsG | SPSK_06989 | 0 | 76 | |

| ChsA | SPSK_08492 | 1e-112 |

88 | ||

| ChsF | SPSK_04841 | 2e-74 |

95 | ||

| Dpm2 | SPSK_08145 | 2e-32 | 83 | ||

| Pmt1 | SPSK_05892 | 0 | 72 | ||

| Pmt4 | SPSK_08628 | 0 | 78 | ||

| Kre2/Mnt1 | SPSK_09069 | 0 | 88 | ||

| Ktr4 | SPSK_05332 | 0 | 74 | ||

| Och1 | SPSK_03245 | 1e-37 |

51 | ||

| Mnn9 | SPSK_09403 | 9e-158 | 75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).