1. Introduction

The relationship between 24-hour movement behaviours (24-HMBs), comprising physical activity (PA), sedentary behaviour (SB), sleep (SL), and cognitive development in adolescents, has garnered increasing attention within the scientific community. Cognitive functions, including executive function, memory, and attention, undergo significant maturation during adolescence and are closely intertwined with lifestyle-related behaviours [

1,

2].

A substantial body of evidence demonstrates that physical activity, particularly when cognitively engaging, enhances executive function domains, including inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, in adolescents. For instance, Mao et al. [

3] found that PA interventions incorporating cognitive challenges significantly improved executive function outcomes, especially when sustained over longer durations. These effects are also observed in populations with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs); Tao et al. [

4] demonstrated moderate-to-substantial improvements in executive function via mind–body and multi-component PA, and Song et al. [

5] further reported gains in inhibitory control among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Hu et al. [

6] also observed marked enhancement of executive function in adolescents with obesity following combined aerobic and resistance training.

In terms of memory, increased levels of PA have been positively associated with working memory, particularly in adolescents from underserved urban environments [

7]. Martín-Martínez et al. [

8] similarly reported improvements in working memory and cognitive flexibility through structured PA in physically inactive adolescents. Furthermore, Tao et al. [

4] confirmed that multi-component PA interventions improve memory functions in adolescents with NDDs. Sleep duration and quality are also critical for cognitive performance. Meta-analytical evidence suggests that 7–8 hours of sleep yields optimal cognitive outcomes [

1], with excessive or insufficient sleep associated with cognitive decline. Richards et al. [

2] found peak cognitive performance at approximately seven hours of sleep, while Adelantado-Renau et al. [

9] linked high sleep quality to superior academic outcomes. Cognitive-behavioural interventions have been shown to enhance both sleep quality and associated cognitive benefits [

10]. The relevance of sleep extends to long-term memory consolidation and attentional capacity in adolescents [

11], though this effect varies by age group [

12]. By contrast, sedentary behaviour is associated with more nuanced cognitive processes. Some forms of SB, such as screen-based activities, have been associated with impaired memory and attention, whereas others may be neutral or even beneficial, depending on the content [

13,

14,

15]. High screen time has been linked to symptoms of inattention and planning difficulties [

16,

17], with reduced P300 amplitudes indicating adverse effects on neurocognitive functioning [

14]. Nonetheless, Wang et al. [

18] suggest that regular PA may mitigate these negative effects, emphasising the importance of a balanced behavioural profile.

Emerging evidence also points to interaction effects. Several studies suggest a potentially synergistic combined influence of physical activity and sleep. Adolescents who engage in regular PA and maintain adequate SL demonstrate superior cognitive performance, including enhanced working memory and academic functioning [

19]. Wong et al. [

20] further observed that sufficient sleep moderated the relationship between PA and cognitive response times. Sleep, therefore, not only contributes independently but also enhances the efficacy of PA interventions on cognition. Conversely, insufficient sleep exacerbates behavioural and cognitive challenges [

21,

22]. Sleep education and schedule-based interventions have improved both sleep and academic performance [

22]. Current literature, however, exhibits several limitations. Most notably, studies often examine PA, SB, or SL in isolation, thereby overlooking the compositional nature of 24-HMBs. As reported by Taylor et al. [

23] and Liu et al. [

24], adolescents who meet integrated 24-HMB guidelines perform better on fluid intelligence tasks, yet adherence remains critically low [

25]. Moreover, regional disparities exist in the evidence base, with Central and Eastern European populations, including Slovak adolescents, being underrepresented [

26].

Measurement bias further complicates existing findings. Although widely used, self-report instruments such as the PAQ-A are prone to overestimation, particularly in younger and female populations [

27,

28]. Triantafyllidis et al. [

29] and Nigg et al. [

30] advocate for increased use of objective measures, such as accelerometry, to improve data validity. Finally, studies frequently rely on generalised academic indicators or intelligence scores, neglecting cognitive subdomains such as attention control and visual memory [

5,

15]. This limited scope may obscure important behavioural–cognitive interactions. Moreover, adolescents from marginalised or clinically diverse backgrounds, e.g., those with NDDs or from low socio-economic settings, remain underrepresented despite potentially greater benefit from targeted interventions [

23,

4].

In response to these gaps, the present study investigates how three 24-HMBs—physical activity (PA), sedentary behaviour (SB), and sleep (SL)—relate to cognitive functions (IQ, attention, and visual memory) in Slovak adolescents aged 15–19 years. In addition, the study examines the validity of self-reported PA using the PAQ-A compared to accelerometer data and explores the interaction between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sleep on cognitive performance. The study addresses four main research questions: (1) How does adherence to 24-HMB guidelines differ by sex and age? (2) How are specific behaviours (sleep duration, MVPA, sedentary bouts) associated with attention, memory, and IQ? (3) Do sleep and MVPA interact to produce synergistic benefits for cognitive performance? (4) How well does self-reported PA (PAQ-A) reflect objectively measured MVPA?

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study included 82 adolescents aged 15 to 19 years (mean age = 16.67 years, SD = 1.07). The sample comprised 32 males (M = 16.72 years, SD = 1.13) and 50 females (M = 16.64 years, SD = 1.05). Participants were recruited from secondary schools during a typical academic year using convenience sampling. Participation was voluntary, and no financial incentives were offered. Adolescents were eligible if they were enrolled in regular schooling, were able to participate in usual daily activities, and did not report any acute illness on the day of testing. Participants were stratified by age as follows: n = 12 were aged 15 years, n = 32 were aged 16 years, n = 24 were aged 17 years, and n = 14 were aged 18–19 years. Only participants with complete cognitive testing, a valid PAQ-A questionnaire, and sufficient accelerometer data were included in the analysis.

Cognitive Assessment

Sustained attention and concentration were assessed using the Kučera Attention Concentration Test [

31]. This cancellation task requires participants to cross out specific target symbols among visually similar distractors within a fixed time limit. The test yields indices of processing speed, accuracy, error rate, and psychomotor tempo and has been widely used in Czech and Slovak school-aged and adolescent populations. Contemporary psychodiagnostic manuals provide norms and interpretive guidelines for their use in older children and adolescents [

32]. In the present study, we used the total number of correctly marked items and the number of errors as primary attention outcomes, with higher correct scores indicating better performance.

General intellectual ability was measured using the Test of Intellectual Potential (TIP) developed by Říčan [

33]. The TIP is a nonverbal reasoning test that assesses fluid intelligence through 29 figural series, in which participants identify the missing element based on the underlying rules governing the sequence. Raw scores can be converted to IQ or standardized scores using age-appropriate norms, which are available for older school-age children and adolescents and are still recommended as part of cognitive test batteries in Central European settings [

32]. In this study, age-standardized IQ scores derived from the TIP served as the primary indicator of general intellectual ability.

Short-term visual memory was assessed with the Meili Visual Memory Test [

34,

35]. Participants view a matrix of pictorial stimuli for 1 min, then have 5 min to freely recall and write down as many items as they can remember. The total number of correctly recalled items reflects the capacity of primary visual memory and the predominant visual memory style. Normative data and administration guidelines for adolescents are provided in recent Slovak methodological materials [

35]. Higher scores indicate better short-term visual memory performance.

Assessment of 24-Hour Movement Behaviours

Objective physical activity (PA), sedentary behaviour (SB), and sleep were assessed using wrist-worn triaxial accelerometers (ActiGraph wGT3X-BT, ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA). Participants wore the device on the non-dominant wrist for seven consecutive days, 24 h/day, during a typical school week, removing it only for water-based activities. Devices were initialized according to manufacturer recommendations. Raw acceleration data were processed in R using the GGIR package (v3.0-3) [

36], which performs auto-calibration, detection of non-wear time, and derivation of time spent in different intensity categories. Age-specific cut-points and processing thresholds for youth were based on Hildebrand et al. [

37] and related work on wrist-worn accelerometry in children and adolescents, allowing the extraction of time spent in sleep, SB, light PA, moderate PA, vigorous PA, and moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA).

Self-reported PA was assessed using the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) [

38]. The PAQ-A is a self-administered, 7-day recall instrument designed for 14–19-year-olds that captures general levels of MVPA during the school year. It consists of 9 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, covering activities at school, during physical education, in leisure time, and on weekends. The PAQ-A has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ≈ 0.75–0.82) and moderate correlations with objective MVPA in adolescent samples [

38,

39].

Procedure

Data collection took place during regular school weeks across all age groups. Testing sessions were scheduled during school hours in collaboration with school administrators. After receiving information about the study, participants (and their legal guardians for minors) provided written informed consent. Cognitive assessments were administered first, in small groups, in a quiet classroom environment under standardised conditions by trained research staff (a psychologist or trained graduate students). The order of tests was kept consistent across classes to reduce order effects. Immediately after the cognitive tests, participants completed the PAQ-A questionnaire, with researchers available to clarify any uncertainties. At the end of the classroom session, accelerometers were distributed and fitted on the non-dominant wrist. Participants received written and oral instructions to wear the device continuously for seven days (including nights), removing it only for bathing, showering, or swimming. After the monitoring period, devices were collected at school and data were downloaded, anonymised, and checked for completeness and signal quality before analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Four specific research questions (RQ1–RQ4) guided the analytical procedures, each aligned with a distinct statistical approach. To address RQ1, the sample was compared by sex (male vs. female) and age group (15, 16, 17, 18–19 years). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to identify differences in key movement behaviour variables: time spent in MVPA, SB, and total sleep duration. Distribution plots were used to examine adherence to internationally recognised thresholds—namely, ≥60 minutes/day of MVPA, <8 hours/day of sedentary time, and ≥8 hours/night of sleep. Effect sizes (r) were reported to interpret the magnitude of group differences.

To investigate RQ2, bivariate associations between movement behaviours (MVPA, SB, sleep duration and timing, bouted variables, and peak-activity indices) and cognitive scores (IQ from the TIP, accuracy and errors from the Attention Concentration Test, and visual memory recall) were examined using Spearman’s rank-order correlation (ρ). A non-parametric approach was selected due to violations of normality in multiple variables. Correlation coefficients were interpreted based on both statistical significance (p < 0.05) and practical relevance (ρ ≥ 0.30 considered moderate).

For RQ3, participants were categorised into four behavioural profiles based on MVPA level (sufficient vs. insufficient) and sleep duration (sufficient vs. insufficient) according to established cut-offs (60 minutes/day for MVPA; 480 minutes/night for sleep). Using this grouping, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to compare IQ, attention, and memory outcomes across the four profiles. If omnibus test results were significant, post hoc Mann–Whitney U tests with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons were conducted to examine pairwise differences.

To address RQ4, the PAQ-A summary score and accelerometer-derived MVPA (min/day) were compared using the Bland–Altman method, providing the mean difference (bias) and 95% limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 SD). In addition, MVPA estimates from PAQ-A and accelerometry, as well as the magnitude of overestimation, were compared across age categories using the Kruskal–Wallis H test, followed by post-hoc Mann–Whitney U tests where appropriate. All analyses were performed in Python 3.11.9 using the packages pandas (2.2.2), SciPy (1.13.1), and statsmodels (0.14.2). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with effect sizes reported alongside p-values where applicable.

Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT, SciSpace AI) were used solely to improve the clarity of the manuscript text and to generate partial graphic interpretations. All AI-assisted text was carefully checked and revised by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final content.

3. Results

3.1. Adherence to 24-Hour Movement Behavior Guidelines and Sex-Based Differences in Movement Behaviors

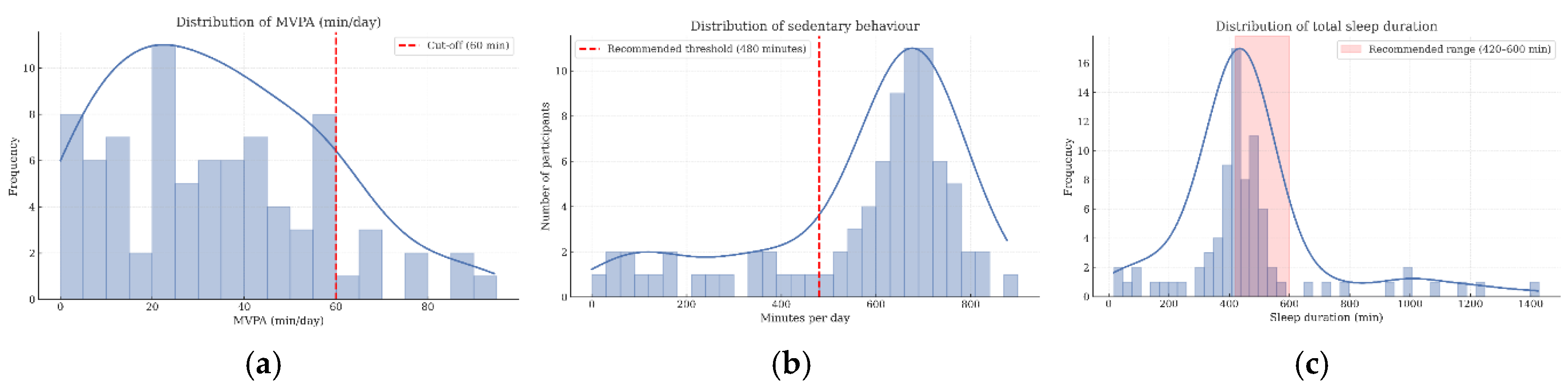

Overall adherence to the 24-hour movement behavior guidelines was low in the total adolescent sample (

Table 1). Sedentary behavior levels were notably high, with most participants exceeding the recommended threshold of <480 minutes per day. The distribution of sedentary time clustered between 600 and 750 minutes (10–12.5 hours). Only 23.2% of participants met the sedentary behavior guideline (

Figure 1b). Boys showed higher compliance (43.8%) than girls (10%), indicating longer sitting among females. Sleep duration was similarly suboptimal. The median sleep time was 433 minutes per night (7 hours), and most participants failed to meet the minimum recommendation of 480 minutes (8 hours) (

Figure 1c). The peak of the distribution ranged from 400 to 460 minutes (6.5 to 7.5 hours). Nearly two-fifths (39%) experienced short sleep (≤420 minutes), while 48.8% achieved adequate sleep and 12.2% reported long sleep durations. Girls showed higher compliance with sleep recommendations (56%) than boys (37.5%), suggesting sex-related differences in nightly recovery patterns. Regarding moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), the distribution was left-skewed (

Figure 1a), with most participants engaging in 10–40 minutes per day. The median daily MVPA was 32.9 minutes, and only 11% of the total sample met the≥60 minutes per day guideline. The lowest compliance was observed among 18–19-year-olds (7.1%), and no 15-year-olds met the MVPA recommendation. In terms of guideline adherence across behaviors, 15-year-olds had the lowest compliance with both MVPA and sedentary time recommendations, whereas 16-year-olds showed the lowest proportion of adolescents with adequate sleep. Overall, adolescents demonstrated a pattern of insufficient physical activity, prolonged sedentary time, and inadequate sleep, underlining the need to address these 24-hour movement imbalances during adolescence.

Mann–Whitney U tests revealed significant sex-based differences across several behavioral variables (

Table 2). Girls showed significantly higher time in sedentary bouts of 0–1 min (r = 0.363), 10–30 min (r = 0.282), and 1–10 min (r = 0.423), all p < 0.05. Total sedentary behavior was also higher among girls compared to boys (p = 0.026, r = 0.246). For low physical activity (LPA), girls again demonstrated higher engagement in very short bouts of 0–1 min (r = 0.355), 10–30 min (r = 0.274), 1–10 min (r = 0.415), and total LPA (r = 0.364), with all differences reaching statistical significance. Moderate physical activity (MPA) showed similar trends: girls had higher engagement in 0–1-minute bouts (r = 0.299) and greater total MPA (r = 0.314). Girls also accumulated more MVPA in 5–10-minute bouts (r = 0.331) and higher total MVPA (r = 0.308). Peak activity metrics confirmed higher levels in girls during the most active 60-minute (r = 0.316) and 30-minute (r = 0.318) periods, as well as greater cumulative activity during the most active 5- and 10-hour blocks (r = 0.278 and r = 0.256, respectively). Collectively, these results indicate that, in this sample, girls accumulated more time in both sedentary and active behaviors than boys, highlighting nuanced sex-based differences in the distribution of 24-hour movement behaviours.

3.2. Associations Between Movement Behaviors and Cognitive Performance

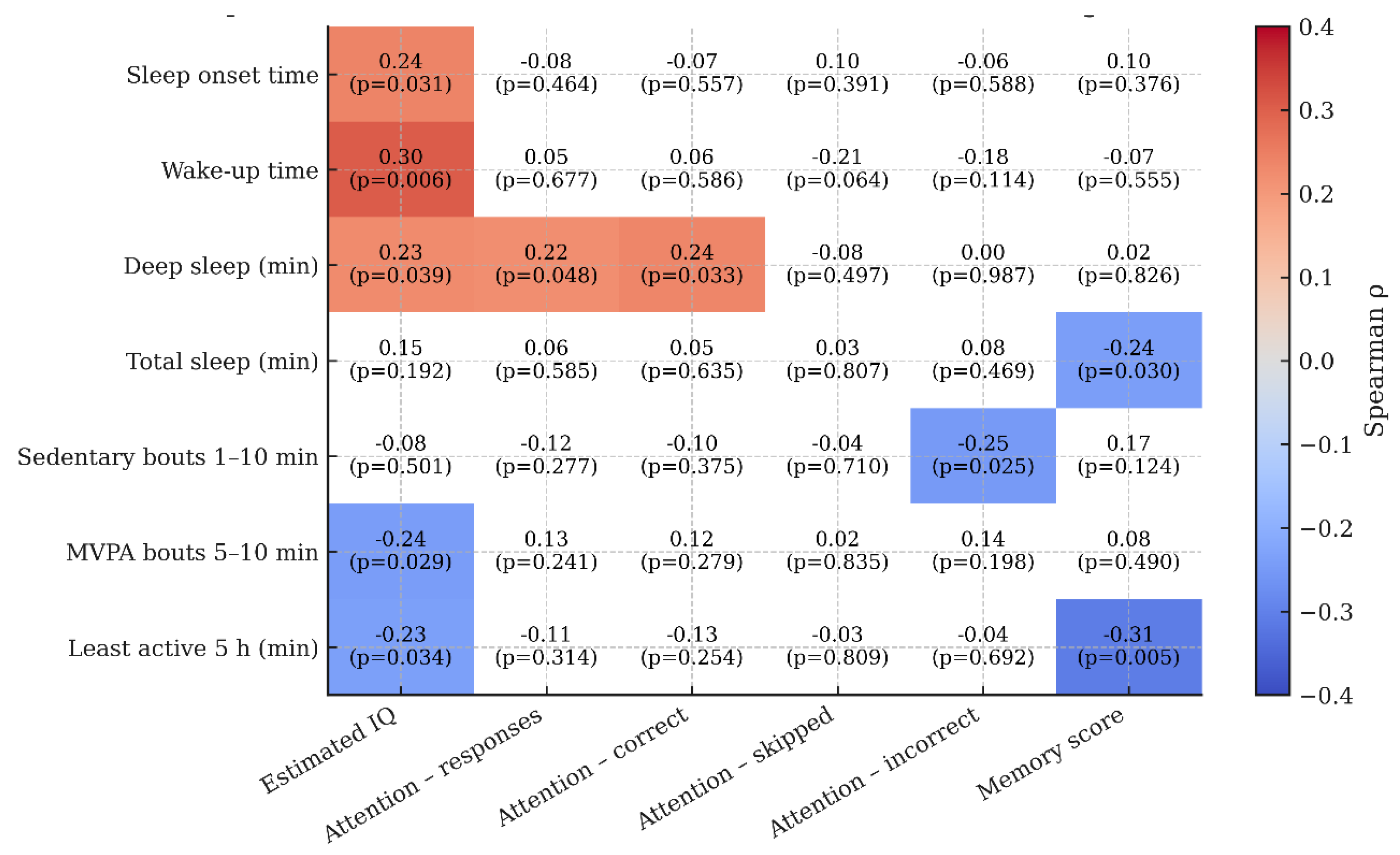

Spearman correlation analysis identified several significant associations between sleep and activity variables and cognitive outcomes. Later sleep onset and wake-up times were positively related to estimated IQ, and longer deep sleep was modestly associated with higher IQ and better attention performance, as reflected in both the number and the correctness of responses. In contrast, total sleep duration was negatively associated with memory scores. With respect to activity, a greater number of sedentary bouts lasting 1–10 minutes was negatively correlated with the number of incorrect attention responses. MVPA accumulated in 5–10-minute bouts was inversely associated with estimated IQ. Higher values of the least active 5-hour period were also negatively related to both estimated IQ and memory scores. Full correlation coefficients and p-values are presented in

Figure 2.

3.3. Cognitive Outcomes Across Combined Sleep and MVPA Profiles

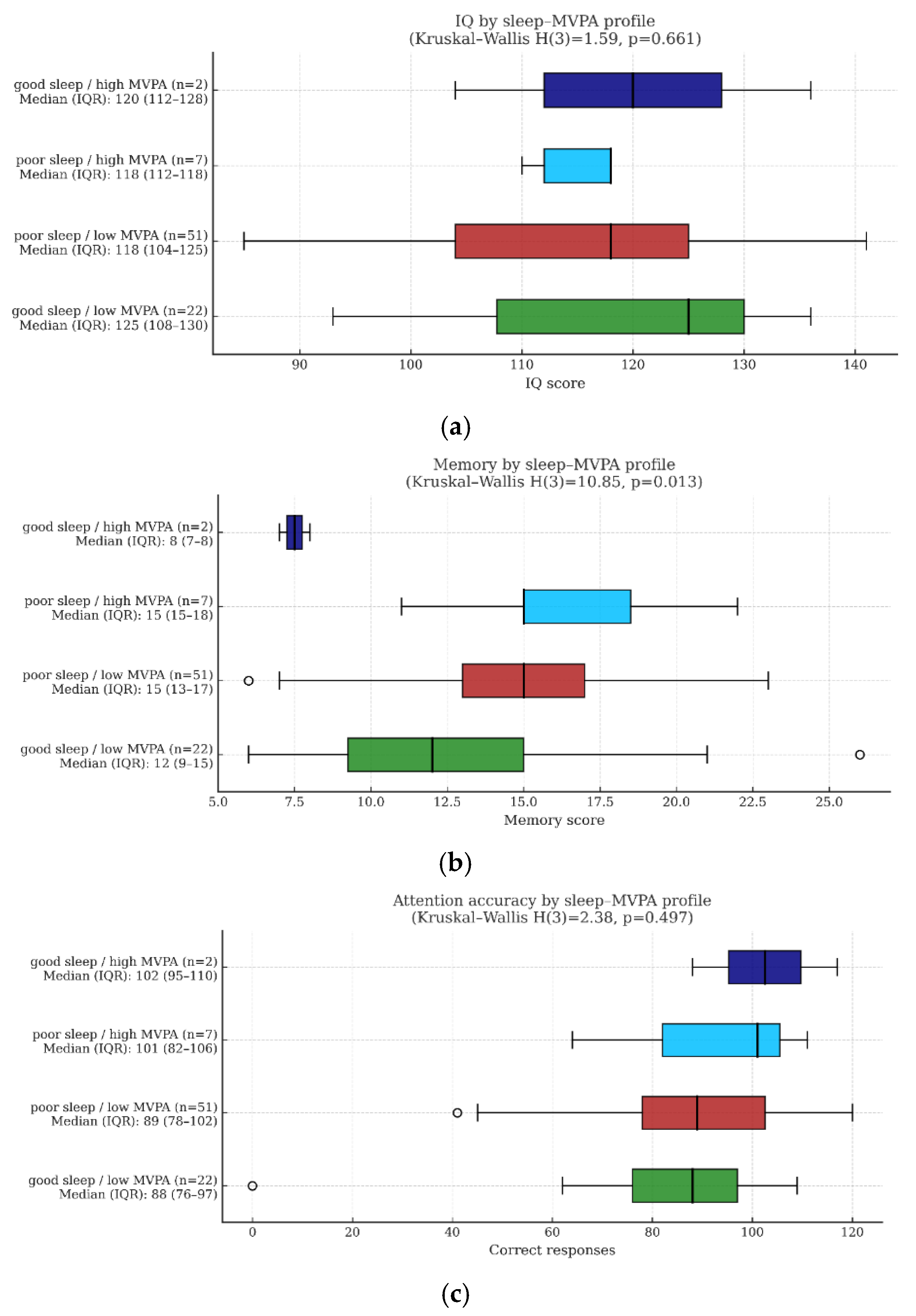

This section presents differences in cognitive performance based on combinations of sleep and MVPA behaviours. Participants were categorized into four behavioural profiles based on sleep duration (adequate vs. poor) and MVPA (high vs. low) thresholds (

Figure 3). For memory, a Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences between profiles, H(3) = 10.85, p = 0.013, η² = 0.13. The Poor Sleep / High MVPA and Poor Sleep / Low MVPA groups both showed the highest median memory scores (Mdn = 15, IQR = 15–18 and 13–17, respectively), whereas the Good Sleep / High MVPA group had the lowest memory performance (Mdn = 8, IQR = 7–8, n = 2). Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc tests, however, did not identify any statistically significant pairwise differences between profiles. For attention, no significant differences were observed between groups, H(3) = 2.38, p = 0.497, η² = 0.03. Median attention scores ranged from 88 (IQR = 76–97, good sleep / low MVPA, n = 22) to 102 (IQR = 95–110, good sleep / high MVPA, n = 2). IQ scores also did not differ significantly across profiles, H(3) = 1.59, p = 0.661, η² = 0.02. The highest median IQ was observed in the Good Sleep / Low MVPA group (Mdn = 125, IQR = 108–130, n = 22), whereas both poor sleep profiles showed lower median values (Mdn = 118, IQR = 112–118 and 104–125, respectively). In this sample, combined sleep–MVPA profiles were thus associated with differences in memory in the overall Kruskal–Wallis test, whereas IQ and attention did not differ significantly between behavioural profiles.

3.4. Agreement Between PAQ-A and Objective MVPA Measures

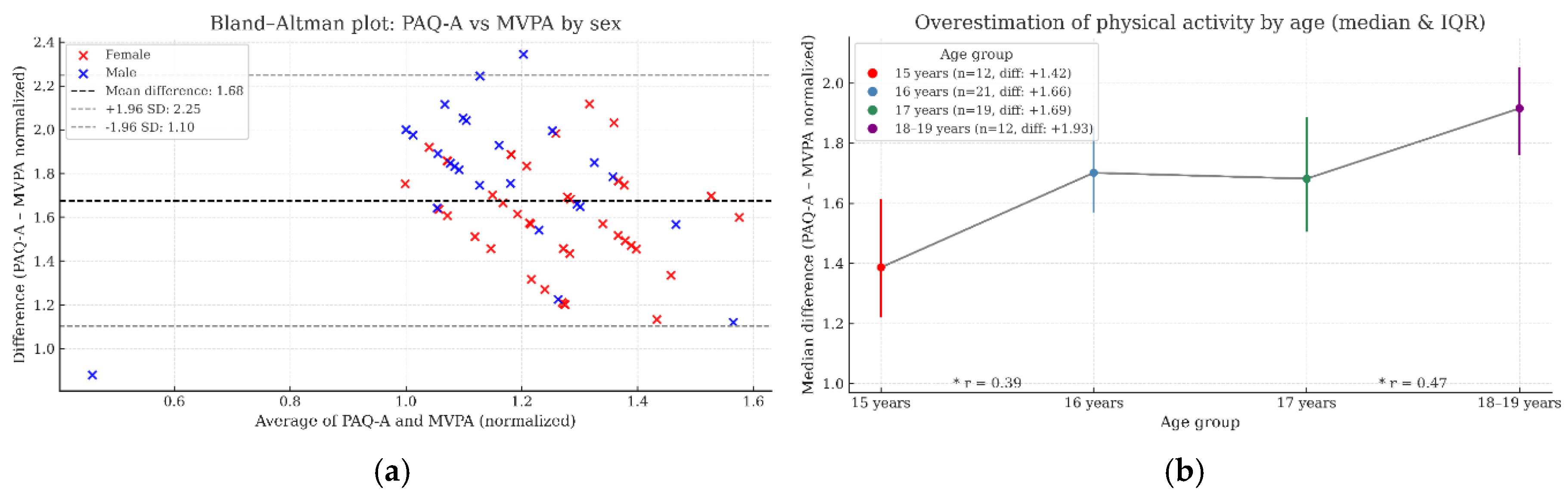

The comparison between self-reported PAQ-A scores and accelerometer-based MVPA indicated systematic overestimation. Bland–Altman analysis (

Figure 4a) revealed a mean difference of +1.68 units (SD = 0.29), with 95% limits of agreement from +1.10 to +2.25. Females showed greater overestimation (mean = +1.76) than males (mean = +1.57). This difference was statistically significant (U = 427.0, p = 0.008, r = 0.36). Age-based analysis (

Figure 4b) showed a progressive increase in overestimation: 15 years: +1.42; 16 years: +1.66; 17 years: +1.69; 18–19 years: +1.93. A Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed significant differences (H(3) = 18.17, p = 0.0004). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences between 15–16 (p = 0.01, r = 0.39) and 17–18/19-year-olds (p = 0.003, r = 0.47). These findings suggest that overestimation of MVPA increases with age and is more pronounced among females, underscoring the importance of accounting for sex and age when interpreting self-reported physical activity in adolescence.

4. Discussion

Behavioral Compliance and Sex- and Age-Based Differences

The present findings underscore a critical issue in adolescent health: the low adherence to the 24-hour movement behavior guidelines across the sample. Only 11% of participants met the recommended threshold of 60 minutes of daily MVPA, while less than a third achieved sufficient sleep duration (≥8 hours per night). Moreover, sedentary behavior was markedly excessive, with most adolescents exceeding 10 hours per day. This general pattern of non-compliance provides a foundational context for interpreting the cognitive outcomes reported in this study.

Consistent with global trends [

41], these results reflect a growing concern regarding declines in physical activity, suboptimal sleep, and prolonged sedentary time among youth. A recent meta-analysis found that only about 7.1% of children and adolescents globally meet all three movement behavior guidelines [

25]. Subgroups such as those with ADHD, disabilities, or obesity report even lower compliance [

42], compounding their vulnerability to cognitive and psychosocial difficulties.

Importantly, sex-based differences in movement behaviors were observed in both our data and the recent literature. Boys tend to engage in more vigorous physical activity and are more likely to meet MVPA guidelines [

43], while girls typically spend more time in sedentary activities, particularly during morning or school-related periods [

44]. Our data confirmed that females reported longer durations across multiple sedentary bout categories and higher light activity levels, suggesting more fragmented movement throughout the day.

Age-related patterns indicated generally poorer adherence in mid-to-late adolescence, with 18–19-year-olds showing the lowest MVPA compliance, 15-year-olds having the lowest combined compliance for MVPA and sedentary time, and 16-year-olds the lowest proportion achieving adequate sleep. These findings align with evidence of age-related declines in MVPA and increases in sedentary time throughout adolescence [

45,

46]. Although some studies report slightly longer sleep duration in late adolescence, this may coexist with increased sleep fragmentation and delayed bedtimes, negatively affecting sleep quality [

47,

48].

These behavioral trends have meaningful implications for interpreting the results of RQ2–RQ4. The imbalance in subgroup sizes—especially the small number of participants meeting both MVPA and sleep criteria—likely limited the statistical power to detect group-based differences in cognitive performance. Furthermore, any associations observed must be interpreted within the context of a behaviorally suboptimal sample, in which cognitive benefits associated with healthy 24-hour behaviors may be attenuated or obscured.

Validity of Self-Reported Physical Activity (PAQ-A) in Adolescents

The present findings reveal a systematic overestimation of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) when self-reported using the PAQ-A compared with accelerometer-based measurements. The observed mean difference and narrow confidence intervals in the Bland–Altman analysis suggest that the PAQ-A tends to inflate physical activity levels across the sample. This trend is consistent with previous research indicating moderate criterion validity of the PAQ-A when validated against objective tools, such as accelerometers [

53,

54]. These discrepancies may arise from the PAQ-A’s recall-based nature and the cognitive demands placed on adolescents to summarize activity across multiple contexts.

Sex-based differences further underscore the variability in reporting accuracy. Female participants exhibited significantly greater overestimation of MVPA than males, a finding consistent with evidence that self-reported physical activity in adolescents is often overestimated and may be particularly susceptible to social desirability bias among females [

55,

56]. While boys typically engage in more MVPA [

43], their reporting appears more aligned with accelerometer-based data. This sex-specific bias emphasizes the importance of stratified analysis in studies utilizing self-report tools.

Age-related trends were also observed, with older adolescents (18–19 years) showing the highest levels of overestimation. Although previous literature suggests that cognitive maturity may enhance the accuracy of self-reports among older youth [

54], our findings do not support this assumption. Instead, the increase in sedentary behaviors with age and possible disengagement from structured physical activities may complicate accurate recall and lead to inflated estimations. This highlights a developmental paradox in which cognitive growth does not necessarily translate into improved self-monitoring of movement behaviors.

Overall, these results call into question the validity of using PAQ-A as a stand-alone measure of MVPA in adolescents, particularly when precise behavioral estimates are required. While the tool shows acceptable internal consistency and test-retest reliability in various populations [

57,

39], its criterion validity appears insufficient for high-stakes or intervention studies without objective corroboration. Researchers and practitioners should consider combining self-reports with device-based methods or applying statistical correction models to account for systematic overestimation, especially in female and older adolescent subgroups.

Future research should aim to refine culturally adapted versions of the PAQ-A and explore machine learning or hybrid models that integrate subjective and objective inputs. Additionally, educational interventions targeting metacognitive skills related to activity awareness may enhance adolescents’ ability to report physical activity more accurately. These findings reinforce the broader recommendation to triangulate data sources when assessing movement behaviors in youth populations.

Limitations

This study presents several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes any causal inferences regarding the relationship between 24-hour movement behaviours and cognitive performance. Second, the relatively small and region-specific sample may limit generalizability, particularly to broader adolescent populations with differing socio-environmental contexts. Third, while the use of both objective (accelerometry) and subjective (PAQ-A) methods strengthens ecological validity, self-reported data were subject to response bias and overestimation, especially among older adolescents and females. Additionally, despite employing validated cognitive tests, these tools may not capture the full spectrum of executive functioning, processing speed, or working memory. Finally, the limited statistical power reduced the sensitivity to detect small-to-moderate effects, especially in stratified or post hoc comparisons (e.g., dual adherence to MVPA and sleep guidelines).

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence on the associations between 24-hour movement behaviours (physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep) and cognitive abilities in adolescents. Despite low adherence rates to movement guidelines, the findings suggest modest associations between specific 24-hour movement patterns (particularly sleep timing and deep sleep duration) and selected cognitive outcomes. Given the small sample size and cross-sectional design, these associations should be interpreted as preliminary rather than definitive evidence that partial guideline compliance directly enhances fluid intelligence, attention, or memory. The integration of objective and subjective measures highlighted discrepancies in adolescent self-reporting, underlining the importance of triangulated data in behavioural surveillance. The results reinforce the relevance of balanced, daily movement patterns as a modifiable determinant of adolescent cognitive development and advocate for region-specific monitoring systems in Central and Eastern Europe. Future longitudinal and intervention-based research is warranted to explore causal pathways and inform sustainable health-promotion strategies tailored to adolescent populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K. and D.DZ.; methodology, P.K., B.R., and D.DZ.; formal analysis, P.K.; investigation, P.K., M.T., and E.CH.; data curation, P.K. and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.; writing—review and editing, B.R., L.H., M.T., E.CH. and D.DZ.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, D.DZ. and B.R.; project administration, P.K.; funding acquisition, B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences (VEGA), grant number 1/0481/22, entitled “Relationship between motor docility and cognitive abilities of pupils.”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Commission of the University of Prešov (protocol code ECUP032023PO, approval date: March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. For participants under 18 years of age, written informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians prior to participation.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating schools, students, and their teachers for their cooperation during data collection. The authors also acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by the Faculty of Sports at the University of Prešov, Slovakia. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, version 5.1) and SciSpace AI to improve the clarity of the text and assist with interpreting graphical outputs. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 24-HMBs |

24-hour movement behaviours |

| ADHD |

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| IQ |

intelligence quotient |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| LPA |

light physical activity |

| MPA |

moderate physical activity |

| MVPA |

moderate-to-vigorous physical activity |

| NDDs |

neurodevelopmental disorders |

| PA |

physical activity |

| PAQ-A |

Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents |

| SB |

sedentary behaviour |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| SL |

sleep |

| TIP |

Test of Intellectual Potential |

| VEGA |

Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences |

References

- Wu, L.; Sun, D.; Tan, Y. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of sleep duration and the occurrence of cognitive disorders. Sleep Breath. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.; Inslicht, S.S.; Metzler, T.J.; Mohlenhoff, B.S.; Rao, M.N.; O’Donovan, A.; Neylan, T.C. Sleep and cognitive performance from teens to old age: More is not better. Sleep 2017. [CrossRef]

- Mao, F.; Huang, F.; Zhao, S.; Fang, Q. Effects of cognitively engaging physical activity interventions on executive function in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Yang, Y.; Wilson, M.; Chang, J.R.; Liu, C.; Sit, C.H.P. Comparative effectiveness of physical activity interventions on cognitive functions in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Fan, B.; Wang, C.; Yu, H. Meta-analysis of the effects of physical activity on executive function in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. PLoS ONE 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yin, H.; Cui, L.; Shen, Q.-Q. An experimental study of the effects of exercise intervention on executive function in obese adolescents. Int. J. Phys. Act. Health 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mala, J.; McGarry, J.; Riley, K.E.; Lee, E.C.H.; DiStefano, L.J. The relationship between physical activity and executive functions among youth in low-income urban schools in the Northeast and Southwest United States. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martínez, I.; Chirosa-Ríos, L.J.; Reigal-Garrido, R.E.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Juárez-Ruiz-de-Mier, R.; Guisado-Barrilao, R. Efectos de la actividad física sobre las funciones ejecutivas en una muestra de adolescentes. An. Psicol. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Adelantado-Renau, M.; Beltran-Valls, M.R.; Migueles, J.H.; Artero, E.G.; Legaz-Arrese, A.; Capdevila-Seder, A.; Moliner-Urdiales, D. Associations between objectively measured and self-reported sleep with academic and cognitive performance in adolescents: DADOS study. J. Sleep Res. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Blake, M.J.; Sheeber, L.; Youssef, G.J.; Raniti, M.; Allen, N.B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adolescent cognitive-behavioral sleep interventions. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Prehn-Kristensen, A.; Göder, R. Sleep and cognition in children and adolescents. Z. Kinder Jugendpsychiatr. Psychother. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tham, E.K.H.; Jafar, N.K.; Koh, C.T.R.; Goh, D.Y.T.; Broekman, B.F.; Cai, S. Sleep duration trajectories and cognition in early childhood: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D. The effects of sedentary behavior on memory and markers of memory function: A systematic review. Physician Sportsmed. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.J.; Keith, L.; Santopetro, N.J.; Burani, K.; Hajcak, G. Associations between physical activity, sedentary time, and neurocognitive function during adolescence: Evidence from accelerometry and the flanker P300. Prog. Brain Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Oeckel, V.V.; Poppe, L.; Deforche, B.; Brondeel, R.; Miatton, M.; Verloigne, M. Associations of habitual sedentary time with executive functioning and short-term memory in 7th and 8th grade adolescents. BMC Public Health 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suchert, V.; Pedersen, A.; Hanewinkel, R.; Isensee, B. Relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sedentary behavior in adolescence: A cross-sectional study. ADHD Atten. Def. Hyperact. Disord. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, J.; Zheng, K.; Shi, M.; Huang, T. Is sedentary behavior associated with executive function in children and adolescents? A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Luo, J. Can physical activity counteract the negative effects of sedentary behavior on the physical and mental health of children and adolescents? A narrative review. Front. Public Health 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Shen, F.; Bu, Y. Physical activity promotes the development of cognitive ability in adolescents: The chain mediating role based on self-education expectations and learning behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.L.; Cheung, G.W.L.; Lau, E.Y.Y. Interaction of sleep and regular exercise in adolescents’ and young adults’ working memory. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.-T.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zou, L.; Chi, X.; Jiao, C. Does more sedentary time associate with higher risks for sleep disorder among adolescents? A pooled analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mazza, S.; Royant-Parola, S.; Schröder, C.; Rey, A. Sommeil, cognition et apprentissage chez l’enfant et l’adolescent. Bull. Acad. Natl. Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Kong, C.; Zhang, Z.; Herold, F.; Ludyga, S.; Healy, S.; Gerber, M.; Cheval, B.; Pontifex, M.B.; Kramer, A.F.; et al. Associations of meeting 24-h movement behavior guidelines with cognitive difficulty and social relationships in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactive disorder. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shi, P.; Jin, T.; Feng, X. Associations between meeting 24 h movement behavior guidelines and cognition, gray matter volume, and academic performance in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Arch. Public Health 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, N.; Haapala, E.A. Association between meeting 24-h movement guidelines and health in children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jurakić, D.; Pedišić, Ž. Hrvatske 24-satne preporuke za tjelesnu aktivnost, sedentarno ponašanje i spavanje: prijedlog utemeljen na sustavnom pregledu literature [Croatian 24-hour guidelines for physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: A proposal based on a systematic literature review]. Medicus 2019, 28(2), 143–153.

- Martínez-Gómez, D.; Martínez-de-Haro, V.; Pozo, T.; Welk, G.J.; Villagra, A.; Calle, M.E.; Marcos, A.; Veiga, O.L. Fiabilidad y validez del cuestionario de actividad física PAQ-A en adolescentes españoles. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2009. [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, A.G.; Janssen, I. Difference between self-reported and accelerometer measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in youth. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, A.; Alexiadis, A.; Soutos, K.; Fischer, T.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D. Comparison between self-reported and accelerometer-measured physical activity in young versus older children. Digital 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nigg, C.R.; Burg, X.; Lohse, B.; Cunningham-Sabo, L. Accelerometry and self-report are congruent for children’s moderate-to-vigorous and higher intensity physical activity. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kučera, M. Test koncentrace pozornosti: Příručka [Attention Concentration Test: Manual]; Psychodiagnostické a Didaktické Testy: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1980.

- Svoboda, M.; Krejčířová, D.; Vágnerová, M. Psychodiagnostika dětí a dospívajících [Psychodiagnostics of Children and Adolescents]; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 2021.

- Říčan, P. Test intelektového potenciálu [Test of Intellectual Potential]; Psychodiagnostické a Didaktické Testy: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1971.

- Meili, R. Faktorenanalyse und Denkpsychologie. Acta Psychol. 1961, 19, 346–347. [CrossRef]

- Šebeňa, R. Metódy experimentálnej psychológie: Návody na cvičenia z kognitívnej psychológie [Methods of Experimental Psychology: Manuals for Cognitive Psychology Exercises]; Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika: Košice, Slovakia, 2021; 132 pp.

- Migueles, J.H.; Rowlands, A.V.; Huber, F.; Sabia, S.; Van Hees, V.T. GGIR: A research community–driven open source R package for generating physical activity and sleep outcomes from multi-day raw accelerometer data. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2019, 2, 188–196. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, M.; Van Hees, V.T.; Hansen, B.H.; Ekelund, U. Age group comparability of raw accelerometer output from wrist- and hip-worn monitors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 1816–1824. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, K.C.; Crocker, P.R.E.; Donen, R.M. The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) and Adolescents (PAQ-A) Manual; College of Kinesiology, University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2004.

- Wyszyńska, J.; Matłosz, P.; Podgórska-Bednarz, J.; Herbert, J.; Przednowek, K.; Baran, J.; Dereń, K.; Mazur, A. Adaptation and validation of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) among Polish adolescents: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, E.; Heussler, H.; Gunnarsson, R. Defining Short and Long Sleep Duration for Future Paediatric Research: A Systematic Literature Review. J. of Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12839. [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Haegele, J.A.; Wu, Y.; Li, C. Meeting the 24-hour movement guidelines and outcomes in adolescents with ADHD: A cross-sectional observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhong, P.; Dang, J.; Liu, Y.; Shi, D.; Hu, P.; Ma, J.; Dong, Y.; Song, Y.-F. Associations between combinations of 24-h movement behaviors and physical fitness among Chinese adolescents: Sex and age disparities. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.R.; Goodman, A.; Page, A.S.; Sherar, L.B.; Esliger, D.W.; van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Andersen, L.B.; Anderssen, S.A.; Cardon, G.; Davey, R.; et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: The International Children’s Accelerometry Database (ICAD). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Collings, P.J.; Wijndaele, K.; Corder, K.; Westgate, K.; Ridgway, C.L.; Sharp, S.J.; Dunn, V.; Goodyer, I.M.; Ekelund, U.; Brage, S. Magnitude and determinants of change in objectively measured physical activity, sedentary time and sleep duration from ages 15 to 17.5 y in UK adolescents: The ROOTS study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kontostoli, E.; Jones, A.; Pearson, N.; Foley, L.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Atkin, A.J. Age-related change in sedentary behavior during childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Gu, D. Prospective associations between adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines and mental well-being in Chinese adolescents. J. Sports Sci. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhong, J. Independence and sex differences in physical activity and sedentary behavior trends from middle adolescence to emerging adulthood: A latent class growth curve analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022. [CrossRef]

- Naz, I.; Naz, F.; Bardaie, N.; Aslam, M.; Chaudhary, M.S.; Abid, M.; Habib, M.A. Physical activity and sleep patterns as determinants of academic performance in secondary school teenagers: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Insights–J. Health Rehabil. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ramer, J.D.; Santiago-Rodriguez, M.E.; Vukits, A.J.; Bustamante, E.E. The convergent effects of primary school physical activity, sleep, and recreational screen time on cognition and academic performance in grade 9. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lemes, V.B.; Gaya, A.R.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, F.; Martins, C.; Fochesatto, C.F.; Cristi-Montero, C. Physical fitness plays a crucial mediator role in relationships among personal, social, and lifestyle factors with adolescents’ cognitive performance in a structural equation model: The Cogni-Action Project. Front. Pediatr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Castelli, D.M. Physical activity, fitness, and cognitive function in children and adolescents. In Sport and Fitness in Children and Adolescents—A Multidimensional View; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Erdim, L.; Ergün, A.; Şişman, F.N. Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A): A psychometric evaluation in a Turkish sample. Sağlık Bilim. Değer 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, A.; Sumaryanti, S.; Arovah, N.I. The validity and reliability of the Physical Activity Questionnaires (PAQ-A) among Indonesian adolescents during online and blended learning schooling. Teor. Metod. Fiz. Vikhov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Taber, D.R.; Stevens, J.; Evenson, K.R.; Ward, D.S.; Poole, C.; MacDonald, J.M.; Sirard, J.R.; Murray, D.M. The effect of a physical activity intervention on bias in self-reported activity. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 316–322. [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; McAuley, E.; DiStefano, C. Is social desirability associated with self-reported physical activity? Prev. Med. 2005, 40, 735–739. [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.; Zainudin, N.H.; Zawi, M.K. Validity and reliability of the modified Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) among Malaysian youth. Sports Athl. J. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).