1. Introduction

In most developed countries, children’s exposure to digital media is a pervasive phenomenon both within and outside the school environment [

1].The term “digital media exposure” refers to the consumption of digital content through visual, verbal, or visuoverbal devices [

2], with the latter often categorized as “screen media”. Screen media exposure encompasses the time spent engaging with any type of screen, whether interactive (e.g., smartphones, tablets, video games, computers, or other portable technologies) or non-interactive (e.g., television) [

3].

Numerous studies have documented the negative physical and psychological consequences of excessive screen use. Prolonged exposure to digital screens has been associated with sedentary behaviors, which are strongly linked to reduced physical fitness, increased obesity, elevated blood pressure, and a higher risk of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents [

4,

5]. Furthermore, excessive screen use in children aged 0 to 7 years has been correlated with sleep disturbances [

6], aggressive behavior, and poorer outcomes in reading comprehension, short-term memory, language acquisition, and vocabulary development by the ages of five and six[

7]. These developmental impairments can contribute to disordered eating patterns, academic difficulties [

8], and diminished executive functioning [

9]. Ultimately, these cumulative effects can lead to significantly poorer academic performance, potentially compromising educational outcomes in both the medium and long term.

Conversely, some studies highlight the potential benefits of technology use among toddlers, particularly when employed for educational purposes through tools such as computers, tablets, and smartphones [

2]. Other research has demonstrated advantages in social and intellectual well-being, such as through online learning, and its utility in facilitating communication for children with disabilities [

10]. Given these conflicting findings, further studies are necessary to elucidate the effects of digital media and address whether the central issue lies in excessive screen time, the nature of screen usage, or other contributing variables.

Most studies linking digital media use with sedentary lifestyles in preschoolers emphasize the risks of excessive usage without categorically condemning it. They often discuss the association between sedentary behaviors and poorer motor skills, disrupted sleep patterns, and reduced physical activity [

11] For instance, it has been reported that nearly 40 million children under the age of five are affected by childhood obesity [

12]. Among the contributing factors, excessive digital media use combined with reduced time allocated to physical activity or sports is particularly significant. Studies suggest that increased screen time correlates with unhealthier dietary habits and lifestyle profiles in school-aged children (8–17 years) [

13]

To mitigate these issues, it is essential to establish healthy routines from early childhood. The first years of life represent a critical period of rapid cognitive and physical development. During this time, routines and lifestyles are formed, providing the foundation for future habits, even though they may evolve over time. Ensuring that children develop appropriate relationships with physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep during this stage is crucial to establishing a foundation for lifelong health [

14]

To preserve and enhance the health of children under five years of age, the United Nations (UN) has issued general recommendations [

15]. These include a minimum of 180 minutes of physical activity (PA) per day, with at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA, 10–13 hours of good-quality sleep, and less than one hour of sedentary screen time (ST). These guidelines stand in stark contrast to the pervasive overuse of screens observed in both school and home environments. Additionally, the UN provides age-specific guidelines for healthy sleep durations: children aged 3–5 years should sleep 10–13 hours (including naps), and children aged 6–13 years are advised to sleep 9–12 hours nightly [

15].

In terms of screen time, both the UN and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [

16] recommend limiting ST for young children. For children aged 2–5 years, screen use should not exceed one hour on weekdays or three hours over the weekend. For children older than six years, ST should be limited to a maximum of 120 minutes daily, accompanied by the promotion of healthy habits and reduced engagement in screen-based activities.

There is a notable lack of information regarding how variables such as age and sex influence ST, sleep duration, and PA in young children, particularly those aged 3–7 years. Although some studies have examined differences in ST and bedtime patterns between weekdays and weekends in preschoolers, they fail to account for variability within specific age groups or between sexes [

17]. Moreover, excessive ST during a child’s first year has been associated with an increased risk of developmental delays by age two, particularly in communication skills, and similar impacts have been observed among teenagers and young adults [

18,

19] Other research has indicated a relationship between excessive ST in children under four years and developmental outcomes, though these findings often consider additional variables such as dietary habits [

20].

Many studies have also focused on excessive screen use among young children during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, these data face significant limitations, as children’s current lifestyles differ considerably from their experiences during the pandemic. Thus, such findings may not accurately represent the present reality. Notably, these studies emphasize that parental decision-making largely determines screen-viewing practices at these ages. As such, educational initiatives regarding health recommendations from organizations concerned with children’s well-being should primarily target parents [

21,

22].

Despite the breadth of research on this topic, there remains a critical gap in studies specifically addressing preschool and early elementary school children, with consideration of both age and sex differences. Given the ongoing controversy and insufficient conclusive data, this study aims to examine the screen media use habits, sleep duration, and PA patterns of children aged 3–7 years during weekdays, on typical school days, and weekends. Additionally, the study seeks to identify significant differences based on age and sex and to determine whether these behaviors align with the UN’s recommendations.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

A total of 243 parents were analysed in this study.

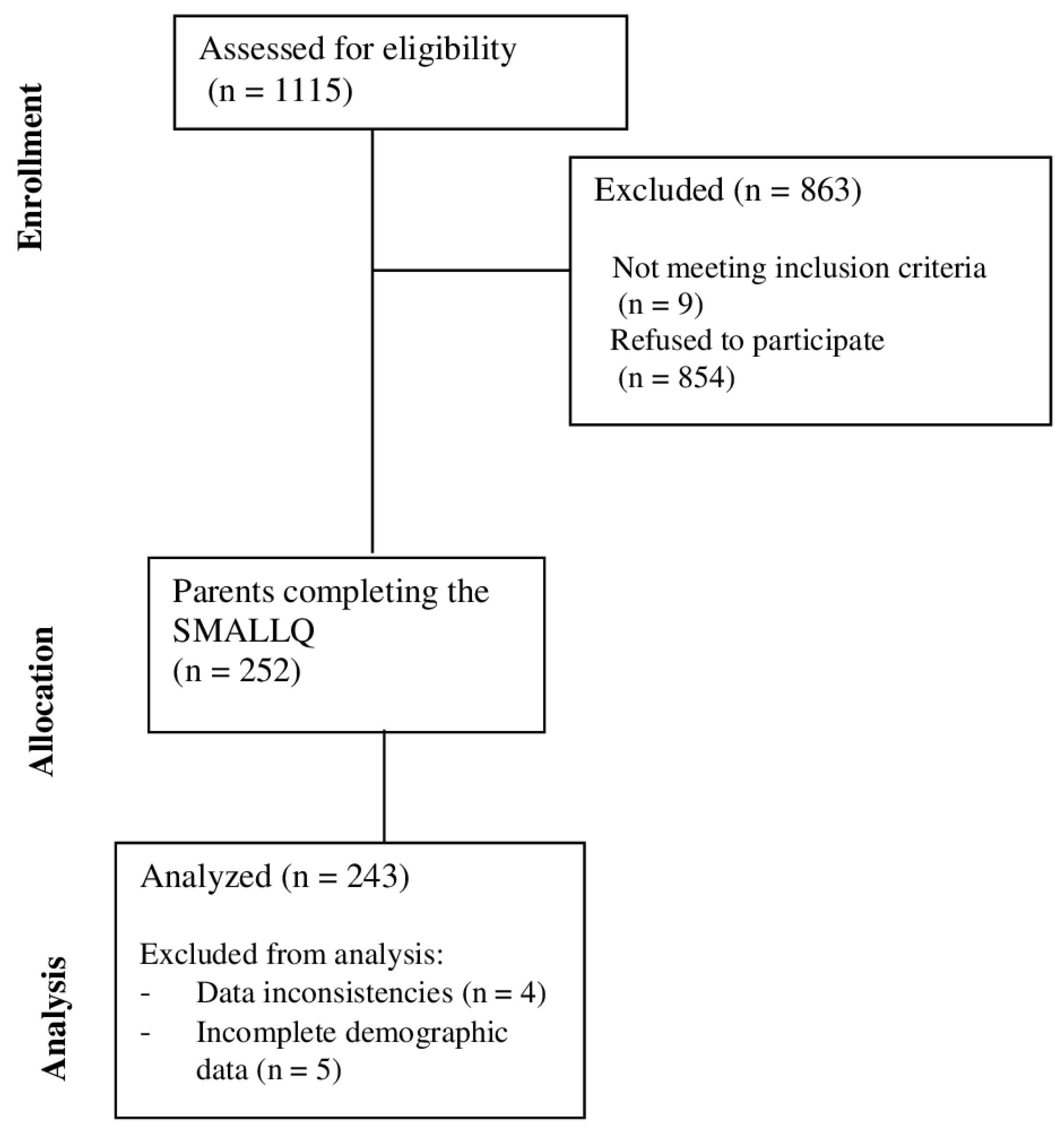

Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram for the prospective cohort study.

3.2. Screen Time, Physical Activity, and Sleep Duration by Age and Sex

Descriptive data and ANOVAS’ results are shown in

Table 1.

ANOVA analyses of ST based on age group revealed a significant effect on weekdays (F(1, 241) = 4.348, p = 0.038, η² = 0.018), with the preschool group spending more time on digital media, but no significant effect on weekends (p = 0.353). Gender did not have a significant impact on ST at either age (p > 0.05).

Regarding PA, age was found to significantly influence activity levels on both weekdays (F(1, 241) = 4.046, p = 0.045, η² = 0.017) and weekends (F(1, 241) = 4.238, p = 0.041, η² = 0.017), with younger children being more active. Gender had no significant effect on PA at any age (p > 0.05).

Finally, SL was significantly affected by age on weekends (F(1, 241) = 4.217, p = 0.041, η² = 0.017), but not on weekdays (p = 0.579). Gender also had no significant effect on SL (p > 0.05).

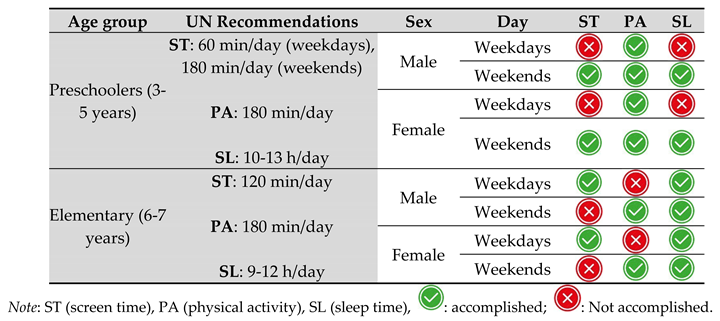

3.3. Compliance with UN Recommendations

Based on the data provided, a comparison was made with the UN recommendations for ST, PA, and SL for children, categorized by age and sex (

Table 2).

Among preschoolers aged 3 to 5, ST on weekdays significantly exceeds the recommended 60-minute limit, averaging over 95 minutes for males and 107 minutes for females. On weekends, although the recommended limit is more lenient at 180 minutes, both groups approach this threshold, suggesting a persistent issue with sedentary behavior (males: 167 minutes, females: 163 minutes). For elementary school children aged 6 to 7, ST remains within the acceptable range of 120 minutes on weekdays, particularly for females, who average just 67.5 minutes. However, on weekends, both sexes exceed the 120-minute recommendation, with males averaging 164 minutes and females 138 minutes, highlighting a pattern of increased media consumption on free days.

PA presents a contrasting trend. While preschoolers fall short of the recommended 180 minutes on weekdays, with males averaging 146 minutes and females 143 minutes, their activity levels improve considerably on weekends. Both groups surpass the recommendation (males: 330 minutes, females: 297 minutes), indicating that weekends provide more opportunities for active play. However, this increase may not fully compensate for the weekday deficits. In terms of PA, elementary school children show mixed compliance. On weekdays, neither males nor females reach the recommended 180 minutes, averaging approximately 116 minutes. However, their activity levels improve significantly on weekends, with both groups engaging in well over the suggested amount (males: 248 minutes, females: 279 minutes).

SL patterns among preschoolers also raise concerns. On weekdays, both males and females sleep slightly below the minimum recommended 10 hours, averaging around 9.7 and 9.6 hours, respectively. Weekends show slight improvement, with average sleep durations slightly exceeding the lower limit of 10 hours (males: 10.2 hours, females: 10.1 hours). SL among elementary school children remains consistently within the recommended range of 9 to 12 hours per night. Both sexes maintain adequate sleep patterns on weekdays and weekends. On weekdays, males sleep 9.7 hours and females 9.5 hours. On weekends, the results show slight increases (males: 9.8 hours, females: 9.9 hours), suggesting that sleep routines may be more established at this age.

4. Discussion

This study investigated screen use habits, sleep patterns, and physical activity in children, considering the day of the week (weekday vs. weekend), age group (preschoolers vs. first grade of elementary school), and sex (males vs. females) within an urban context in a Mediterranean city in Spain.

The findings align with existing literature, indicating that age plays a more critical role than sex in shaping these lifestyle behaviors during early childhood. Significant age-related differences were observed across all studied variables, with younger children engaging in more physical activity and sleeping longer on weekends compared to older children. These results are consistent with previous research suggesting that PA levels tend to decline as children grow older [

25]. Similarly, the age-related decrease in sleep duration observed in this study aligns with established developmental patterns, as sleep needs naturally diminish with age [

12].

Sex differences in physical activity and sleep were not observed in this sample, which contrasts with previous studies reporting higher PA levels in boys compared to girls [

26]. This absence of significant differences may be attributed to the relatively young age of the participants, as sex-related disparities in activity and sleep behaviors often become more pronounced during later childhood and adolescence.

Our findings indicate that the average screen time for children in the sample frequently exceeds the guidelines recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the United Nations. This elevated ST may contribute to a higher prevalence of sedentary behavior, which has been consistently associated with reduced physical fitness and an increased risk of obesity in children [

4,

5]. Research indicates that prolonged screen exposure is associated with detrimental effects, including reduced physical activity as well as psychosocial and developmental challenges such as impaired social skills, lower academic performance, and behavioral problems [

7,

8]. Despite these concerns, it is important to acknowledge that screen media, when used appropriately and in moderation, can serve as a valuable educational resource, supporting the development of cognitive and communication skills [

2]. These findings highlight the need for more nuanced guidelines that consider both the type and context of screen use, rather than focusing exclusively on duration. Nonetheless, adherence to recommended screen time limits remains essential.

Physical activity levels in this sample demonstrated a significant decline with increasing age, from 3–4 years to 5–6 years. These findings align with previous research indicating that engagement in physical activity, exercise, and sports tends to decrease as children grow older [

25]. These early years are critical for establishing healthy lifestyle habits. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), children under the age of 5 should engage in at least 180 minutes of physical activity daily [

15]. For preschool-aged children (3–5 years), the data largely comply with the UN recommendations for physical activity and sleep duration. However, screen time exceeds the recommended limit on weekends, with both male and female preschoolers spending more than three hours per day on screens during this period. For elementary school-aged children (6–13 years), the data indicate non-compliance with the physical activity recommendation, as children in this group engage in less than the required 180 minutes of daily activity. While their screen time remains within the recommended limits, sleep duration falls slightly below the 9–12 hour guideline but still aligns closely with the lower end of the recommended range.

The reduced physical activity observed in the older group may be attributed to their structured daily routines, as elementary school children tend to spend more time in organized activities compared to younger children. This structured schedule may limit opportunities for free play and active exploration, both of which are critical for physical and cognitive development [

14]. These results underscore the need for interventions to promote physical activity and sports in this age group.

The analysis of sleep habits revealed a significant decrease in sleep duration with age, particularly during weekends. These results align with previous research suggesting that the sleep requirements for children naturally decline as they grow older [

27]. Despite this trend, the findings indicate that a substantial proportion of children aged 5–6 fail to meet the recommended sleep duration of 10–13 hours. This insufficient rest may contribute to a range of adverse outcomes, including behavioral problems, cognitive difficulties, and an increased risk of obesity [

6]. The relationship between excessive screen time and reduced sleep has been extensively documented in the literature [

11]. Excessive screen use, particularly before bedtime, can disrupt melatonin production—a hormone crucial for regulating sleep cycles [

4]. This disruption may result in delayed sleep onset, reduced sleep duration, or even poorer sleep quality. The findings of this study confirm that children with higher screen time tend to have shorter sleep durations. These observations underscore the need for interventions aimed at reducing screen exposure, especially during the hours leading up to bedtime, to foster healthier sleep habits.

The study aimed to explore potential relationships among physical activity, screen time, and sleep. The findings suggest a complex interplay forming a vicious cycle that reinforces sedentary behavior and contributes to the rising prevalence of childhood obesity and related health issues. Increased ST is associated with reduced PA and shorter sleep durations, perpetuating a cycle with detrimental effects on children’s health. Excessive ST not only reduces opportunities for PA and sport but also disrupts sleep patterns, fostering a sedentary lifestyle and weight gain. This interdependence of behaviors has been corroborated by other studies, which highlight their significant short- and long-term impacts on children’s well-being [

12]. Given this relationship, it is evident that a comprehensive and multidimensional approach is essential to promote healthier lifestyle behaviors in young children. Interventions should focus on increasing opportunities for physical activity and ensuring sufficient sleep while simultaneously addressing excessive screen time. Engaging parents and legal guardians is crucial, as they play a pivotal role in establishing and reinforcing healthy routines. These habits should emphasize regular PA, limited ST, and the creation of an optimal environment for sleep. To break the cycle of sedentary behavior and associated health risks, interventions must target both children and their caregivers. Strategies should include setting clear limits on ST, encouraging active play, and fostering consistent and adequate sleep patterns. By cultivating an environment that prioritizes health and well-being, these efforts can significantly improve children’s long-term lifestyle behaviors and overall quality of life.

The study presented several methodological limitations that must be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the sample was geographically restricted to a mediterranean urban context (Valencia, Spain). The geographical, climatic, and socio-economic characteristics of the analyzed context may influence the generalizability of the results, as these variables act as moderators of the dependent variables studied. Furthermore, the data on dependent variables ST, PA, and SL were based on parental reports, which may be subject to recall bias or inaccuracies, potentially affecting the reliability of the data. Another limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which captures only a single snapshot of behaviors at a specific point in time. This approach limits the ability to draw conclusions about causal relationships between the variables. Furthermore, the study’s focus on children aged 3 to 7 years restricts the findings to a particular developmental stage, which may not be applicable to children in other age groups.

Given these limitations, future research should address several key areas. Expanding the sample to include a larger and more diverse group of participants would enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, utilizing objective measures, such as device usage tracking or direct observation, would provide more accurate data on screen time, physical activity, and sleep patterns. A longitudinal approach would also be valuable, as it would facilitate the examination of long-term effects and causal relationships.

Further studies should investigate the long-term impact of screen time on both the physical and mental health of children. Additionally, exploring the effects of different types of screen content—such as educational versus recreational material—on development could provide important insights. Finally, developing comprehensive guidelines that consider both the duration and purpose of screen use could help mitigate potential negative impacts on young children’s well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H. and A.P.; Methodology, F.H., A.P. and M.Y.H.C.; Software, F.H., A.P. and M.Y.H.C.; Validation, F.H., A.P. and M.Y.H.C.; Formal Analysis, F.H., P.T. and A.P.; Investigation, A.P., P.T., L.E, D.C. and F.H.; Resources, A.P., P.T., L.E, D.C. and F.H.; Data Curation, P.T.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, F.H., P.T. and A.P.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.P., P.T., L.E, D.C., F.H and M.Y.H.C.; Supervision, F.H. and A.P.; Project Administration, F.H. and A.P.; Funding Acquisition, F.H. and A.P.