Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 91E45; 91E10

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Well-Being

1.2. Personal Construct Psychology

1.3. Feature-Based Approach to Modeling Psychological Well-Being

2. Mathematical Foundations

2.1. Formalization of the Similarity Self/Ideal Index

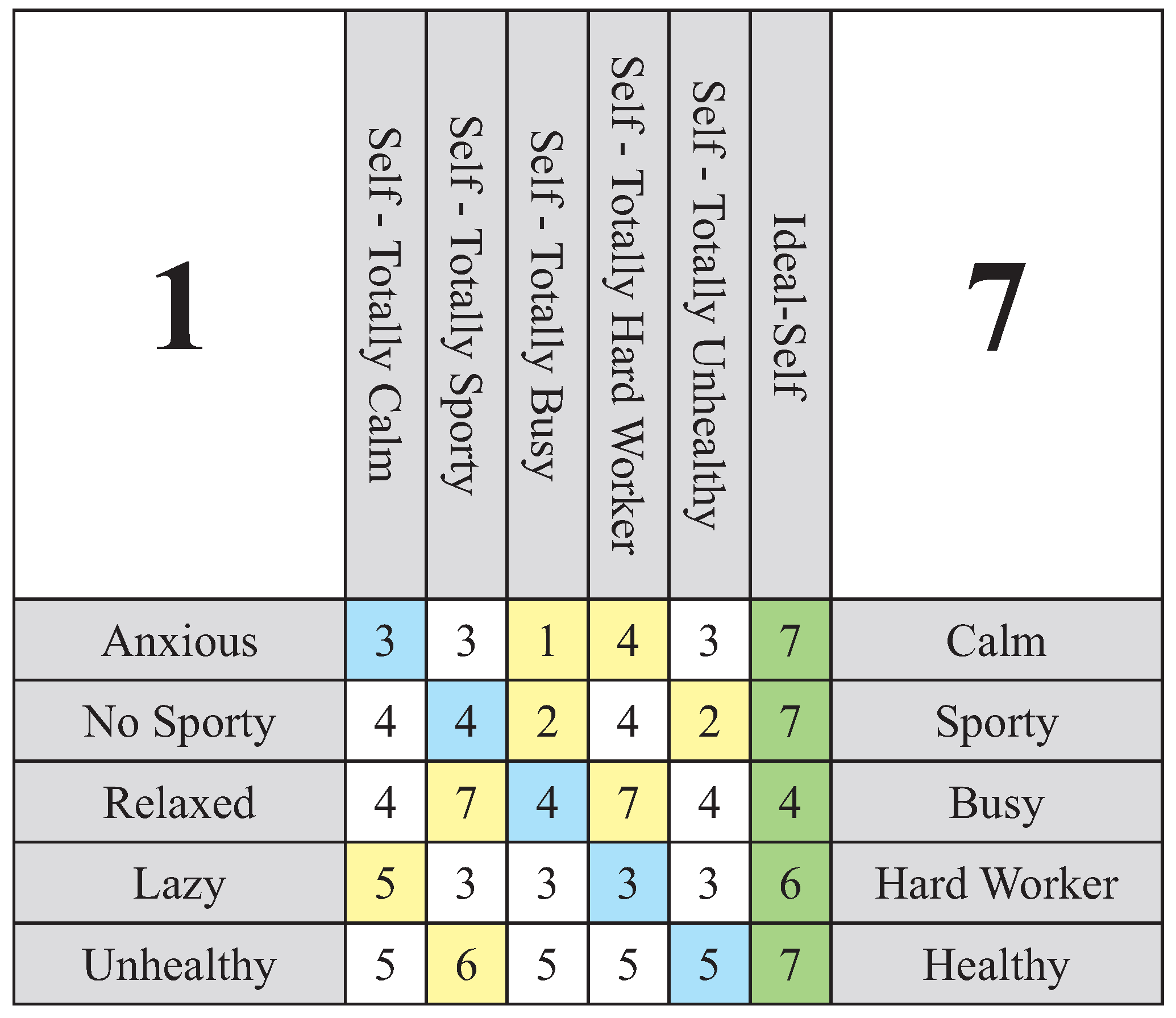

- (i)

- The sign of the score, , which represents the qualitative nature of the attribute. It indicates the specific pole of the construct with which the individual identifies.

- (ii)

- The absolute value of the score, , which quantifies the intensity or salience of the attribute. It measures how strongly the individual endorses that particular pole.

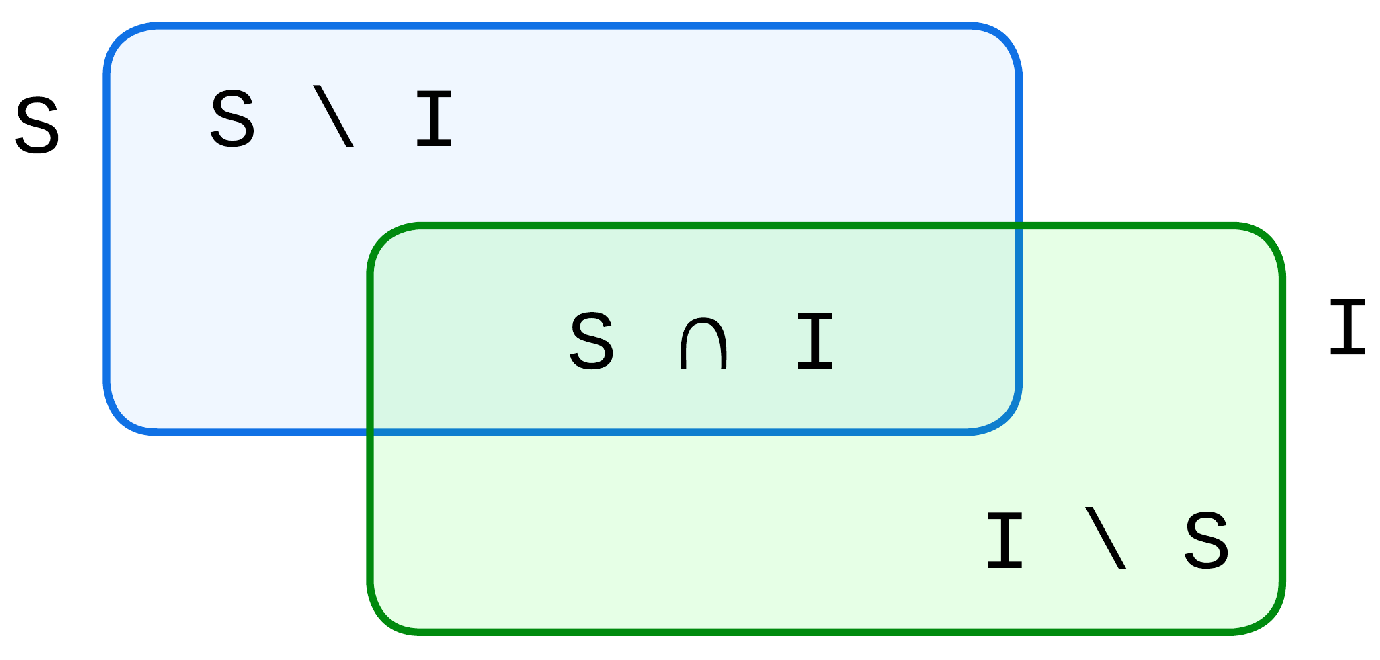

- (i)

- The set of shared attributes, where both self and ideal align on the same pole:

- (ii)

- The set of attributes distinctive to the Self-Now (discrepancies):

- (iii)

- The set of attributes distinctive to the Ideal-Self (aspirations):

2.2. Properties of the SSI Index

- (i)

- Lower Bound (): Since the numerator, , is non-negative and the denominator is a sum of non-negative terms (assuming ), the entire fraction must be non-negative.

- (ii)

- Upper Bound (): To prove the upper bound, we must show that the numerator is less than or equal to the denominator:

- (i)

- Maximum Similarity: The index attains its maximum value of 1 if and only if the Self-Now and Ideal-Self vectors are congruent on all constructs, meaning for every construct i, .

- (ii)

- Complete Mismatch: The index attains its minimum value of 0 if and only if the set of shared attributes is empty ().

- (i)

-

Maximum Similarity: (⇒) Assume . This implies that the numerator and denominator of the SSI formula are equal, which requires that . Since and the magnitude functions are non-negative, this holds if and only if and . The condition for an attribute to be included in the disjoint sets is . For the magnitudes of these sets to be zero, it must be that for every i where , both and . This is equivalent to stating that there is no construct for which and have opposite signs. Thus, for all i, .(⇐) Assume that for every construct i, . This implies that for all i, the product . According to the definitions, the disjoint sets and only contain attributes where . Therefore, the only attributes that could possibly belong to these sets are those where (i.e., where and/or ). In such cases, the magnitudes and contributed to the sums and are zero. Consequently, and . The SSI formula simplifies to:(assuming , the non-trivial case). This establishes the biconditional relationship between and pole congruence.

- (ii)

-

Complete Mismatch: (⇒) Assume . Given that the denominator is non-negative, this equality requires the numerator to be zero: . The magnitude function is a sum of non-negative terms . The sum can only be zero if the set over which the sum is taken, , is empty.(⇐) Assume . From Definition 5, if the set of shared attributes is empty, its magnitude must be 0. Substituting this into the SSI formula yields:Provided that at least one attribute exists in either or (the non-trivial case), the denominator will be positive, and thus .This establishes the biconditional relationship between and .

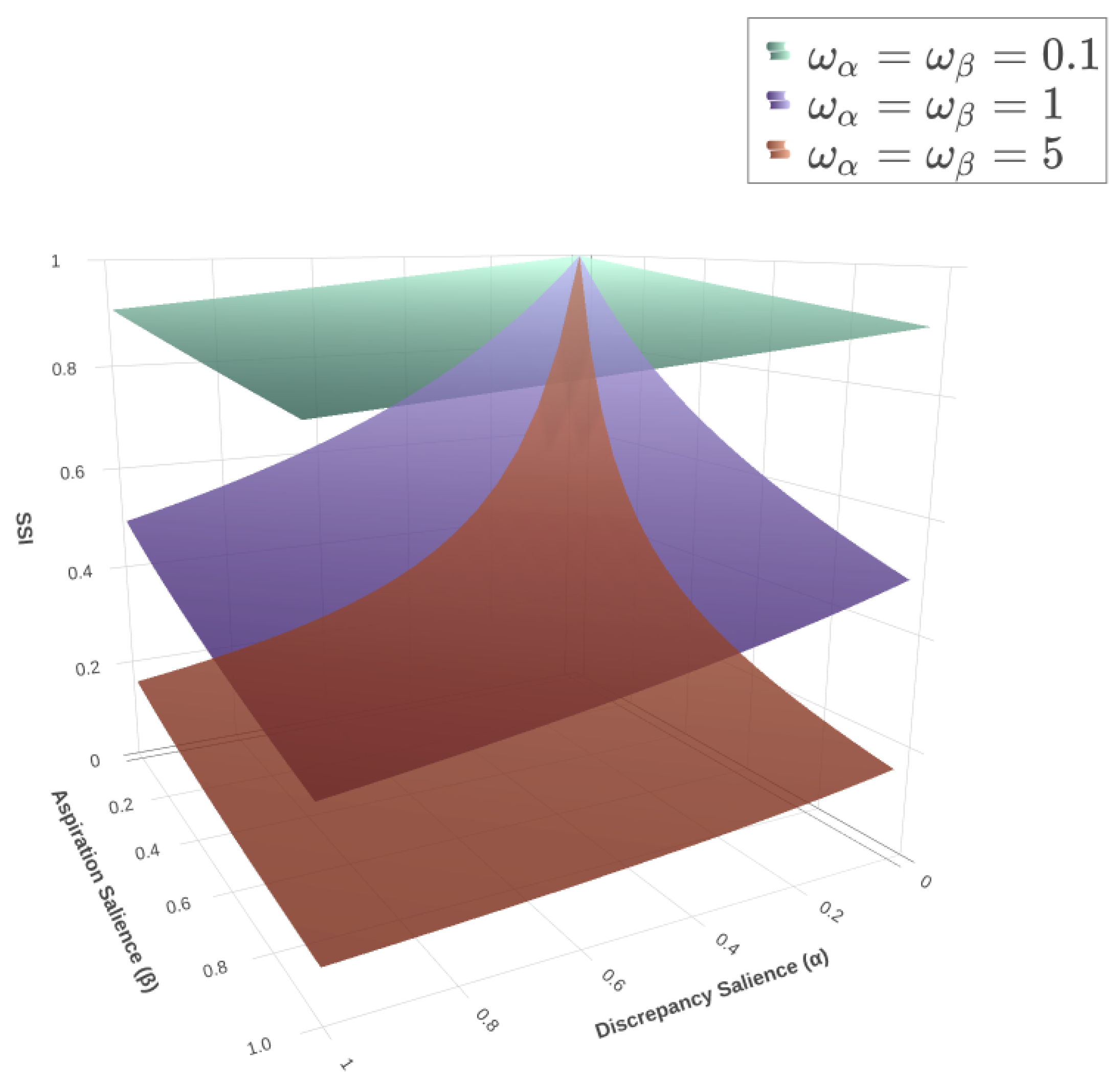

- (i)

- The Discrepancy Ratio (), which quantifies the magnitude of self-discrepancies relative to the magnitude of congruence:

- (ii)

- The Aspiration Ratio (), which quantifies the magnitude of unfulfilled aspirations relative to the magnitude of congruence:

- (i)

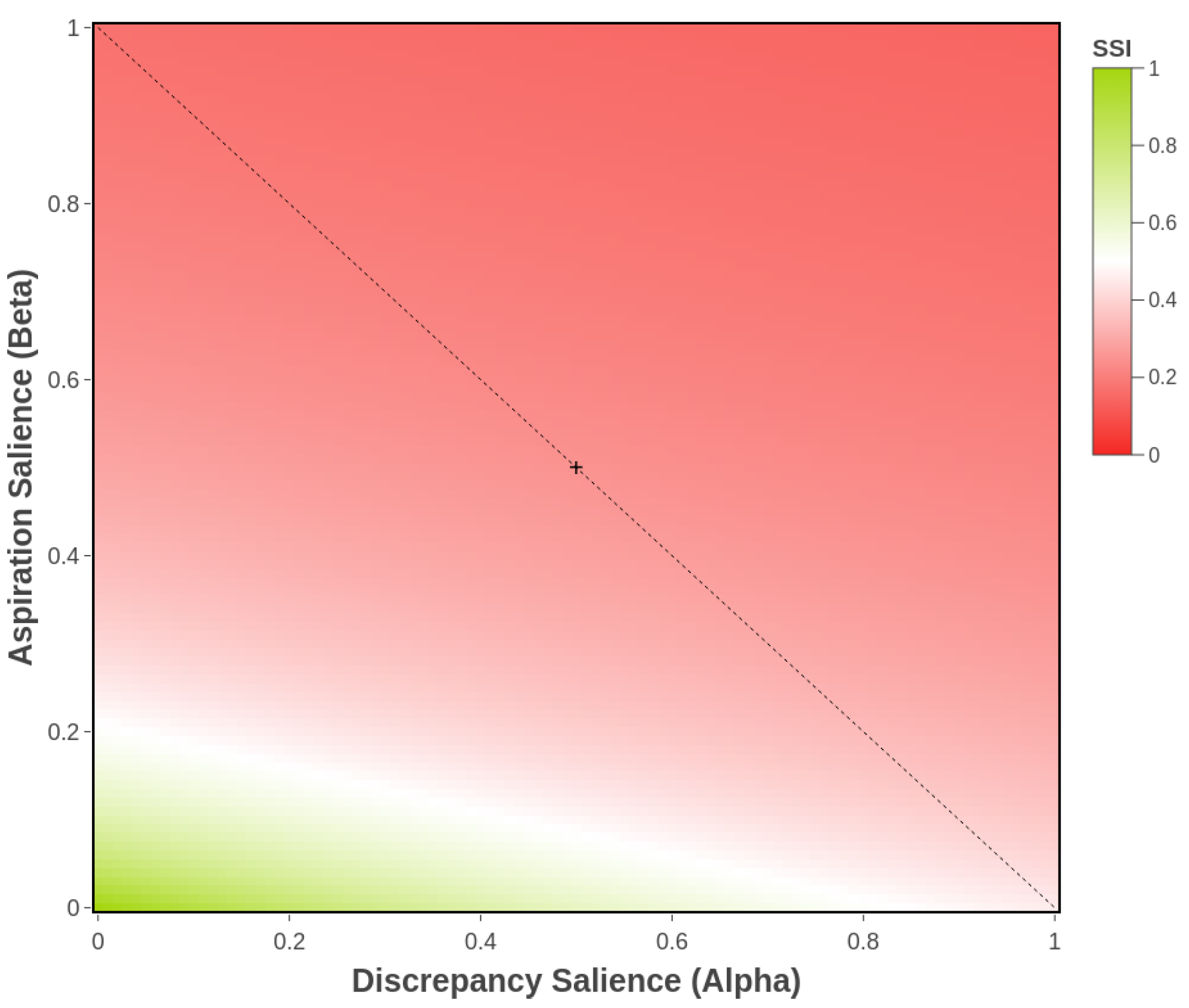

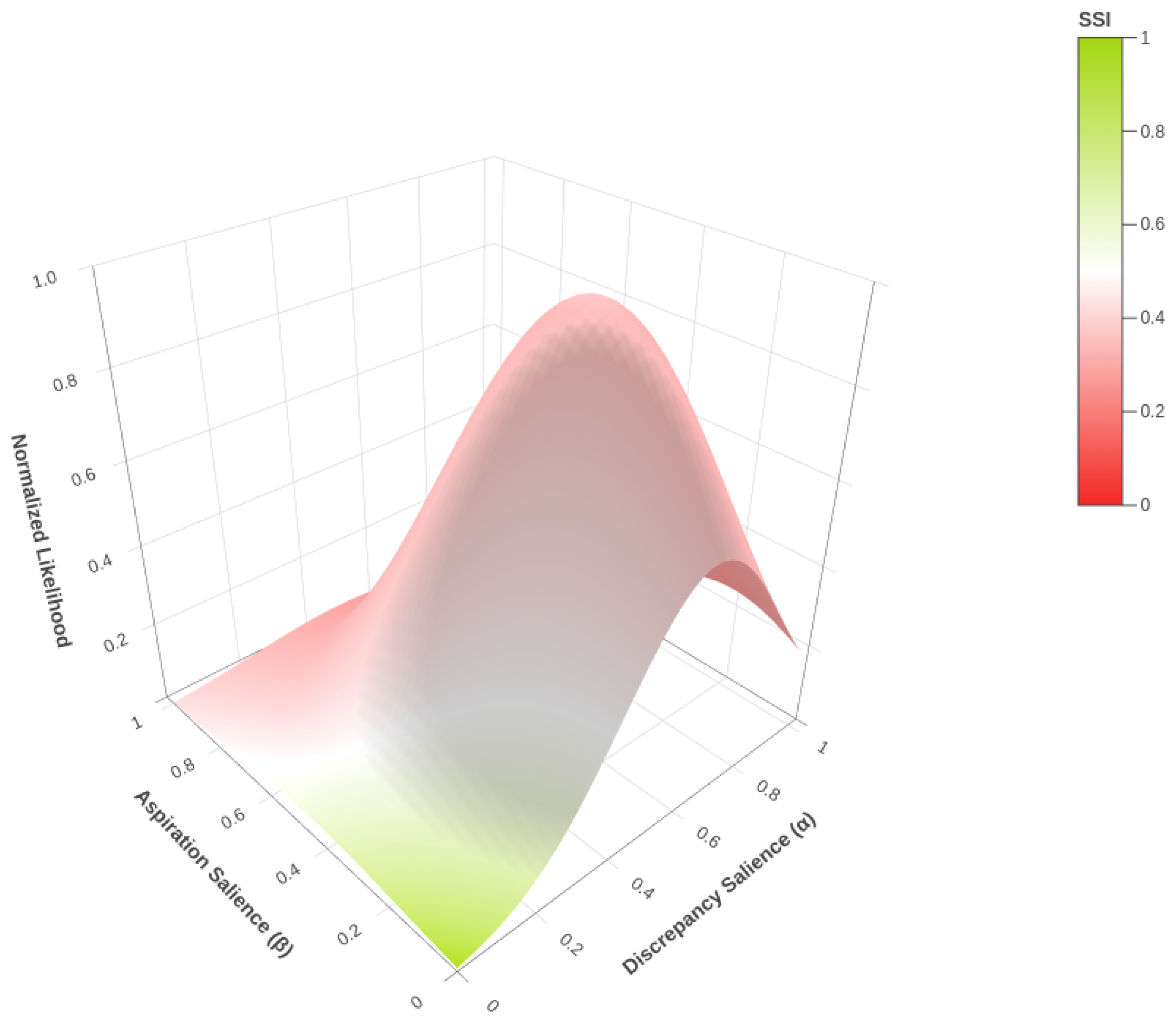

- Non-linearity and Monotonic Decrease: The function is non-linear and strictly decreasing with respect to both α and β. The first partial derivatives are non-zero and negative for all in the domain:

- (ii)

- Convexity: The function is convex over its domain. The second partial derivatives are non-negative, indicating that the rate of decrease is itself decreasing:

- (iii)

- Asymptotic Behavior: The function has a horizontal asymptote at . The limit of the function as either salience parameter tends to infinity is zero:

- (iv)

- Parametrized Sensitivity: The local sensitivity of the index is determined by the gradient vector, , whose magnitude depends directly on the structural coefficients and :where . The magnitude of the gradient, , is thus a direct function of the structural coefficients, confirming their role as shape parameters governing the steepness of the decay.

- (i)

- The magnitude of shared attributes, , for the construct ’Healthy’ () is:

- (ii)

- The magnitude of self-discrepancies, , for the poles ’Anxious’ and ’Lazy’ is:

- (iii)

- The magnitude of unfulfilled aspirations, , for the poles ’Calm’, ’Sporty’, and ’Hard Worker’ is:

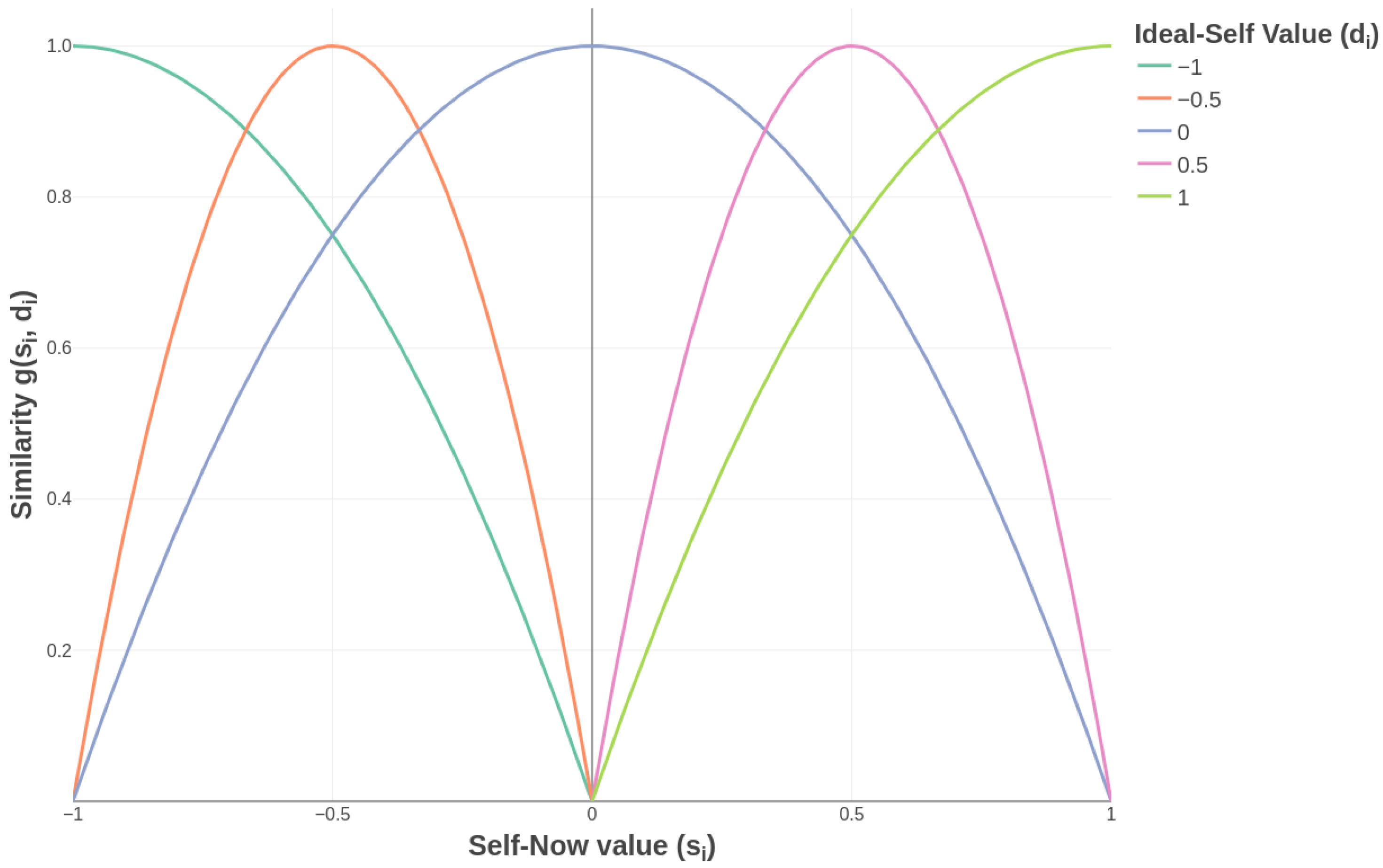

2.3. Fuzzy Similarity Interpretation of the SSI Function

- (i)

- Normalization: .

- (ii)

- Boundedness: for all .

- (iii)

- Reflexive maximum: if and only if .

- (iv)

- Monotonic decay: decreases strictly as increases.

- (v)

- Continuity: is a continuous and differentiable function.

3. Discussion

3.1. Conceptual Framework of the Fuzzy Similarity Space

3.2. Applications

3.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSI | Similarity Self/Ideal |

| PCP | Personal Construct Psychology |

| WimpGrid | Weighted Implication Grid |

References

- Tversky, A. Features of similarity. Psychological Review 1977, 84, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. (Eds.) Well-being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowne, D.P.; Marlowe, D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology 1960, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O.J. Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2013, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, G.W. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Fransella, F.; Bell, R.; Bannister, D. A Manual for Repertory Grid Technique; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Botella, L.; Feixas, G. Teoría de los Constructos Personales: Aplicaciones a la Práctica Psicológica; Laertes: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.E. Identification in terms of personal constructs: Reconciling a paradox in theory. Journal of Consulting Psychology 1961, 25, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, N. Identification, reflection, and correlation: Problems in the bases of repertory grid measures. International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology 1992, 5, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.C. A note on the correlation of elements in repertory grids: How to and why. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 2006, 19, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosch, E. Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 1975, 104, 192–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, F.G.; Maddox, W.T. Human category learning. Annual Review of Psychology 2005, 56, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology 2008, 59, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanfeliciano, A.; Saúl, L.A.; Botella, L. Weighted Implication Grid: A graph-theoretical approach to modeling psychological change. Frontiers in Psychology 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruspini, E.H. Numerical methods for fuzzy clustering. Information Sciences 1970, 2, 319–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.J. Fuzzy Set Theory—and Its Applications, 4 ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfeliciano, A.; Saúl, L.A. Exploring the Personal Construction of Psychological Change via Graph Theory: Validation of the Weighted Implication Grid. Preprint avaible at SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, D.N. The Change of Personal Constructs from the Viewpoint of a Theory of Construct Implications. PhD thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 1965.

- Sanfeliciano, A.; Saúl, L.A.; Hurtado-Martínez, C.; Botella, L. PB Space: A Mathematical Framework for Modeling Presence and Implication Balance in Psychological Change Through Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Axioms 2025, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfeliciano, A.; Saúl, L.A. WimpTools: A Graph-Theoretical R Toolbox for Modeling Psychological Change. [Software], 2025. Version 1.0.0. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).