Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

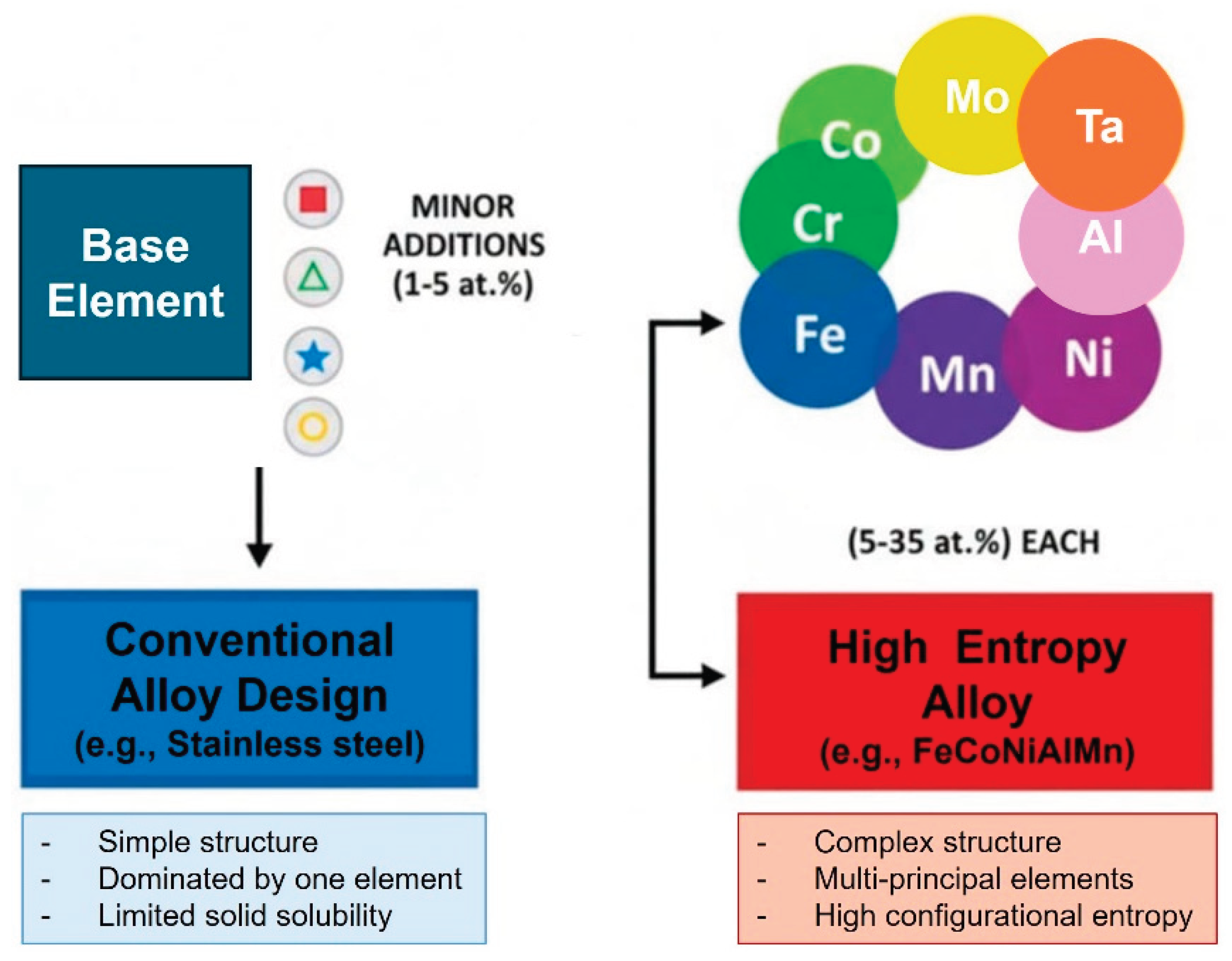

2. Thermodynamic and Structural Fundamentals

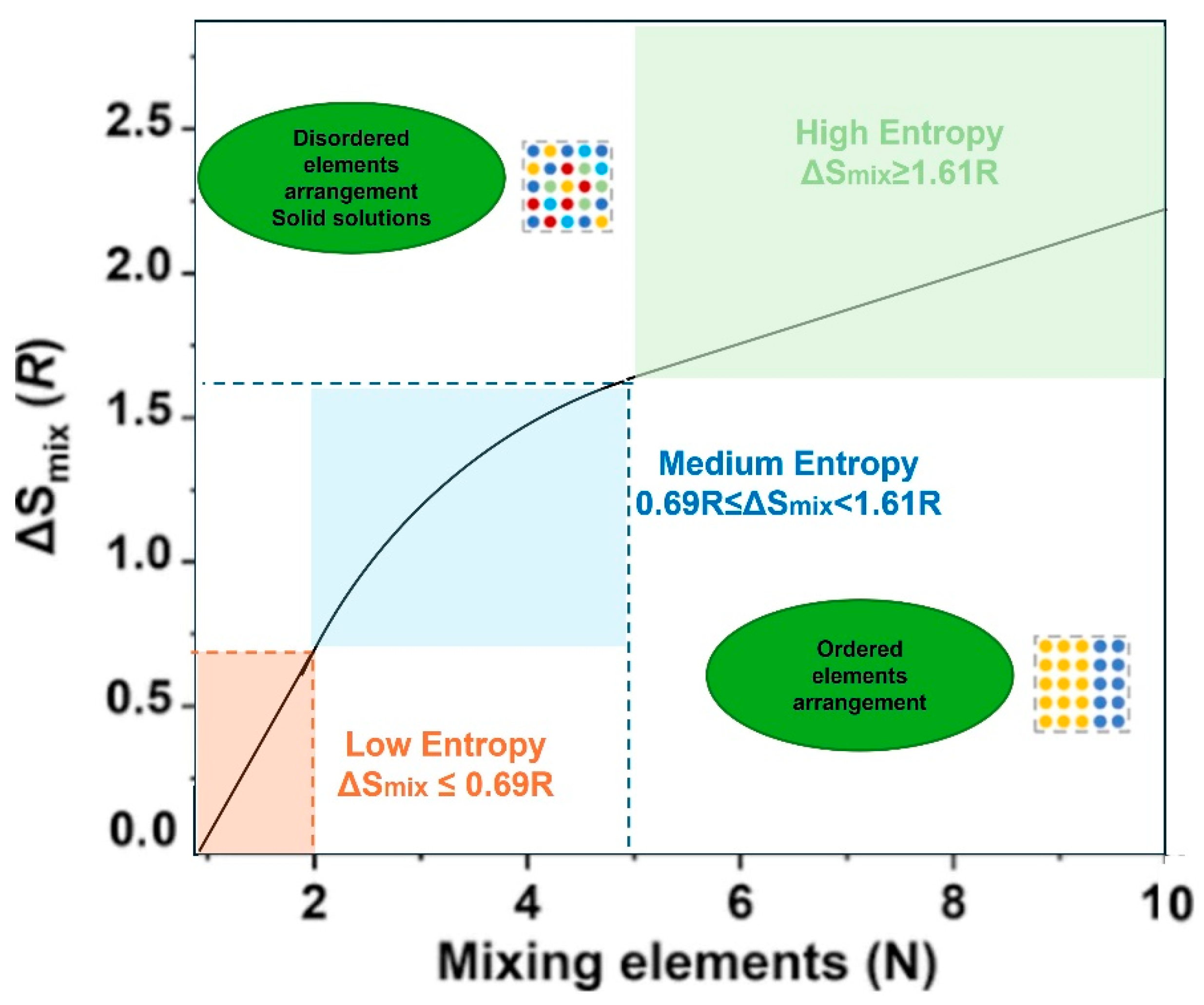

2.1. Classical Thermodynamic Descriptors—Definitions and Typical Thresholds

- Eelec(V) is the ground-state electronic energy calculated from density functional theory (DFT). It is computed at different atomic configurations and volumes to establish the static lattice energy curve [28].

- Fvib(T,V) is the vibrational free energy, which can be obtained using the quasiharmonic approximation (QHA): Fvib(T,V) = kBT∫g(ω,V)ln[2sinh(ℏω/2kBT)]dω, where g(ω,V) is the phonon density of states [29]. Thermal expansion effects were considered within the quasiharmonic approximation by allowing the equilibrium volume V(T) to minimize Ftotal(T,V) at each temperature: (∂Ftotal(T,V)/∂V)T = 0. This approach inherently accounts for isotropic thermal expansion, which is a reasonable assumption for cubic HEAs. For systems exhibiting significant anisotropy, an anisotropic expansion model can be introduced through independent variation of lattice parameters a, b, c [30].

- Fmag(T,V) represents the magnetic contribution, often described by the disordered local moment (DLM) model [31] or mean-field approximation [32]. Fmag(T,V) captures the magnetic disorder at finite temperatures [33]: Fmag(T,V) = −kBTln[(sinh(μB/kBT))/(μB/kBT)], where μ is the magnetic moment and B is the effective magnetic field.

- Sconf = −kB∑cilnci is the configurational entropy, where ci represents the atomic fraction of each constituent element.

2.2. Refined Descriptors for HEAs Modeling

- Atomic size mismatch, represented by the parameter δ, plays a crucial role in stabilizing solid solutions and controlling lattice distortion. The parameter is defined as δ = sqrt[(∑i*ci)*(1 − ri/rm)2)] ×100%, where ci and ri are the atomic fraction and atomic radius of element i. FCC HEAs typically exhibit a lattice mismatch of 3–6%, while refractory BCC HEAs can reach 8–12%. These distortions contribute to solid-solution strengthening by impeding dislocation motion and altering defect energetics, and recent high-resolution studies using synchrotron XRD and EXAFS have quantified these effects across multiple HEA systems [41,42].

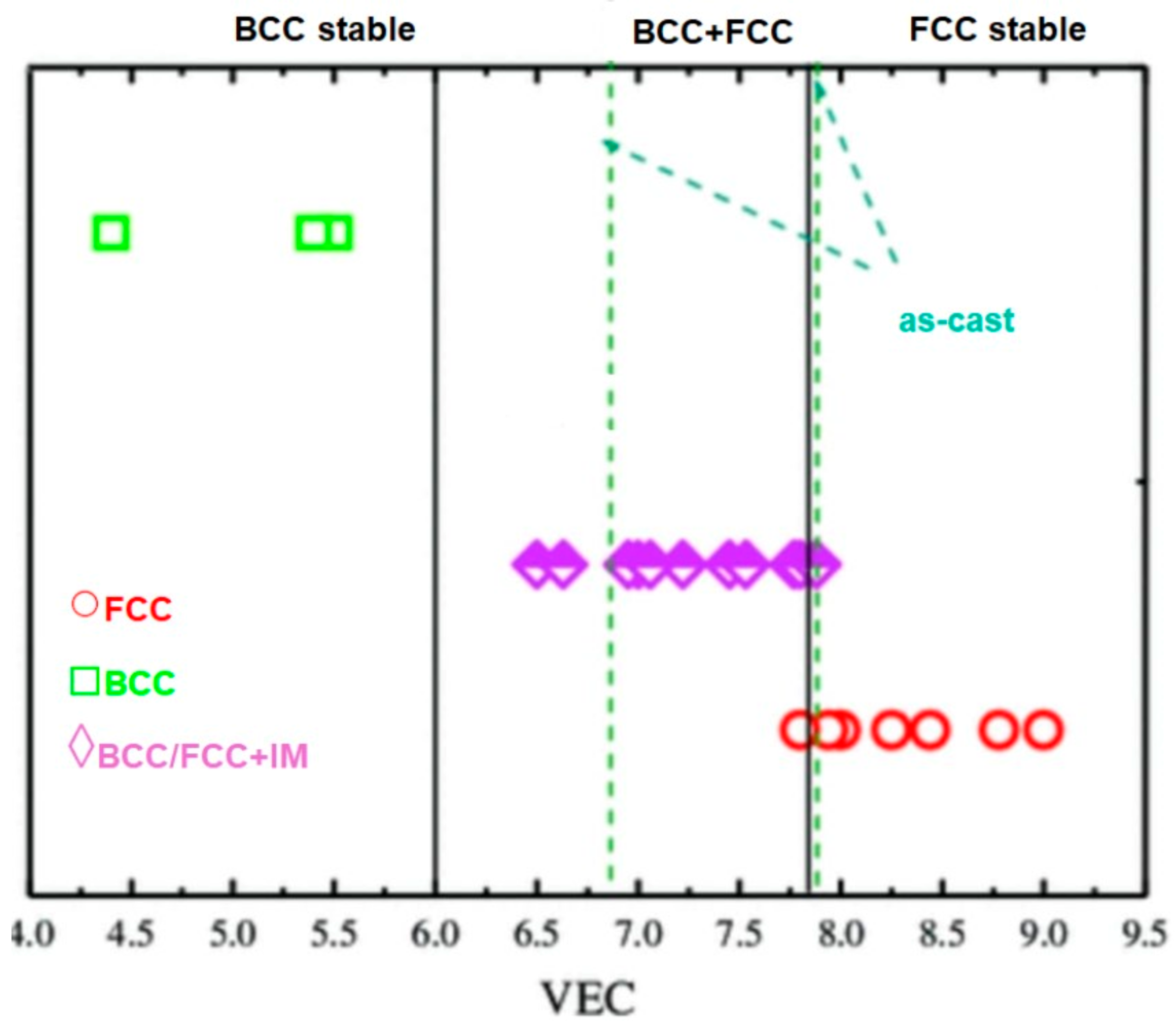

- Valence electron concentration (VEC) remains a key electronic parameter that correlates strongly with the preferred crystal structure. Compositions with VEC greater than 8, tend to stabilize FCC structures, whereas VEC below 6.8, favors BCC lattices. Alloys with intermediate VEC values often result in mixed-phase microstructures (Figure 3). Recent investigations have refined these thresholds through systematic experimentation and DFT-based electronic structure calculations, demonstrating that subtle changes in composition can shift the dominant lattice type and profoundly influence mechanical properties such as stacking fault energy (SFE) and ductility [9].

- Φ (entropy/entropy-excess) parameter. Dimensionless Φ parameter has been proposed to delineate single-, two- and multiphase regions, with suggested empirical thresholds (Φc ≈ 20 separating single vs multiphase behavior in some studies). This parameter attempts to combine entropy and size mismatch in ways that collapse larger data sets [43].

- Electronegativity-based metrics and Δχ (average electronegativity difference). Simple electronegativity spread or variance (e.g., Δχ =∑ici(χi−χ−)2 has been used to penalize compositions with large chemical driving forces for ordering/compound formation [44]. More recent works augment Δχ with local environment weighing or combine it with valence/d-band occupancy concepts to capture charge transfer and electronic structure effects. These electronegativity-type modifiers improve discrimination in some alloy classes (especially when strong compound-forming pairs exist) but are not a universal fix [45,46].

2.3. Critical Comparison Between the Classical Rules vs. Computational and Experimental Suggestions

- Binary interaction and formation energies matter. First-principles formation energies for binary pairs (and short-range order tendencies) can be assembled into mixture models; these energies frequently explain why an alloy that looks “entropy-favored” by Ω parameter, still decomposes—because binary pairs have strongly negative formation enthalpies that drive ordering. Recent work explicitly builds classifiers from DFT-derived pairwise interaction features and demonstrates accuracy comparable to or better than models based purely on empirical scalar descriptors, while also offering mechanistic interpretability (which binaries dominate the tendency to order). This work shows DFT-derived interaction features materially improve predictive power [52].

- Electronic structure and local environment rules. DFT reveals that local charge transfer and the d-band occupancy of specific sites control cohesive energy changes and ordering tendencies; descriptors that encode d-band filling or local electronegativity environment improve discrimination of phases (especially for transition-metal-rich HEAs and catalytic HEAs). New studies propose linear combinations of d-band filling + neighborhood electronegativity as robust predictors for both catalytic activity and phase stability. These electronic descriptors partially subsume what the simple Δχ tries to capture, but with stronger physical grounding [53].

2.4. Ongoing Debates, Outstanding Challenges and Future Directions of HEAs Designing Models

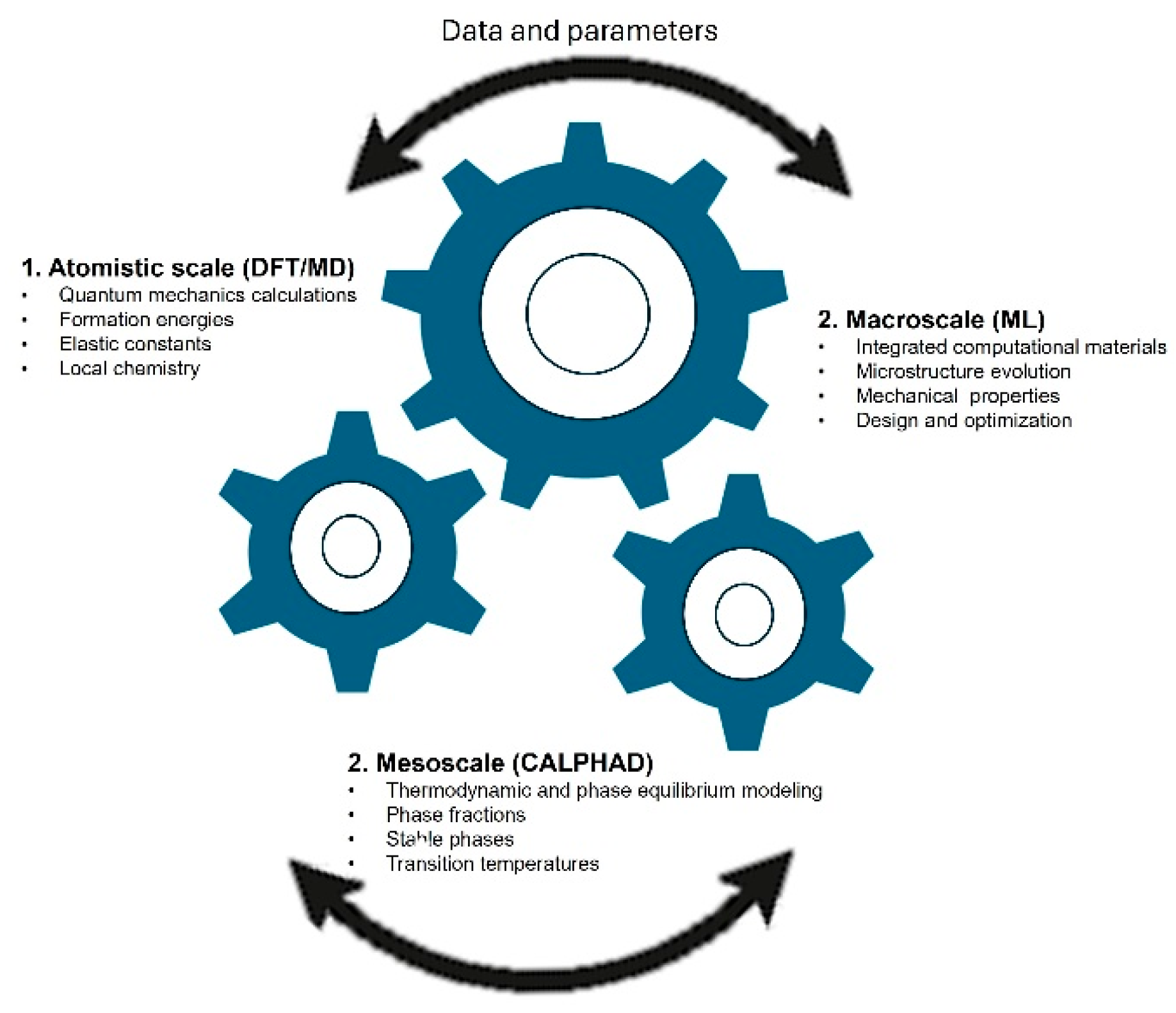

3. Computational Approaches

3.1. First-Principles Density Functional Theory (DFT) of HEAs

3.2. CALPHAD Methods of HEAs

3.3. Limitations Inherent in Current Computational Frameworks of HEAs and Future Directions

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Typical Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | - First-principles accuracy (electronic structure level) - Predicts phase stability, defect energetics, electronic/magnetic properties - No need for empirical parameters |

- Computationally expensive for large/highly disordered systems - Limited to small cells and short timescales - Approximations in exchange-correlation functionals |

- Formation enthalpies - Phase stability maps - Elastic constants - Electronic density of states (DOS), band structure |

| CALPHAD (CALculation of PHAse Diagrams) | - Efficient for multi-component alloys - Can handle experimental + theoretical data - Provides thermodynamic modeling for high-order systems |

- Accuracy depends on thermodynamic databases - Limited predictive power for unexplored compositions - May oversimplify configurational/atomic-scale effects |

- Phase diagrams (T-x, T-P) - Gibbs free energies - Solidification pathways - Phase fractions vs. T |

| Cluster Expansion + Monte Carlo (CE + MC) | - Captures configurational entropy and chemical ordering - Efficient for predicting phase stability in disordered alloys - Scales better than pure DFT for large systems |

- Requires accurate DFT training data - Limited to substitutional disorder (mainly solid solutions) - Computationally intensive for very high-order systems |

- Configurational phase diagrams - Order–disorder transition temperatures - Short-range order parameters |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | - Captures finite-T and dynamical effects (diffusion, mechanical behavior) - Can simulate microstructural evolution - Suitable for large systems (10^5–10^6 atoms) |

- Accuracy depends on interatomic potentials - Limited simulation timescales (ns–μs) - May miss rare events and long-term stability |

- Diffusion coefficients - Mechanical properties (stress–strain curves, yield strength) - Thermal conductivity - Defect evolution |

| Machine Learning (ML) | - Fast screening of large compositional spaces - Can uncover hidden correlations in multi-dimensional data - Flexible integration with DFT, CALPHAD, MD data |

- Requires large, reliable training datasets - Limited interpretability (black-box models) - Predictions may lack physical rigor if not guided by theory |

- Property prediction (hardness, strength, stability, Tc) - Materials discovery (composition optimization) - Surrogate models for phase diagrams and mechanical/thermal properties |

4. Processing Techniques

4.1. Melt-Based Routes and Rapid Solidification

- BCC + intermetallic (e.g., σ-phase or μ-phase): can occur in Cr- or Mo-rich HEAs, providing hardness, but less ductility. Characteristic example is the CrFeCoNi-based systems [124].

- FCC + Laves phase: it is mostly observed in systems with refractory or transition metals (e.g., V, Nb, Mo) eg. AlCoCrFeNiNbx [125].

4.2. Powder Metallurgy, Mechanical Alloying and Sintering Strategies

4.3. Additive Manufacturing of HEAs: Opportunities and Limitations

4.4. Thermomechanical Processing, Severe Plastic Deformation (SPD) and Texture Control

4.5. Surface Engineering, Thin Films and Coatings

4.6. Heat Treatment, Homogenization, Ordering and Precipitate Engineering

4.7. Process-Aware Alloy Design: Modeling, Machine Learning and High-Throughput Workflows

4.8. Challenges, Open Problems and Outlook

5. Mechanical Properties

- Solid-solution strengthening in HEAs arises because the multiple principal elements create local chemical and atomic size fluctuations, which hinder dislocation motion.

- Grain-refinement (via severe plastic deformation or equal channel angular pressing (ECAP)) further enhances strength through the Hall–Petch effect.

- Precipitation or coherent second-phases (e.g., carbides, nitrides, borides) can provide additional hardening, though this is less common in classical “single-phase” HEAs.

- Interstitial alloying (C, N, O, B, H) is emerging as a powerful route to raise strength, by introducing local lattice distortions, interstitial-atom/dislocation interactions, and in some cases micro-alloyed precipitates. For example, the mini review “Atomic scale understanding of interstitial strengthened HEAs” (2025) provides a detailed mechanistic discussion of how interstitials modify defect energetics, stacking fault energies (SFEs), and deformation behavior [157].

5.1. Yield, Tensile Strength and Ductility: Typical Envelopes and Exemplar Alloys

5.2. Deformation Mechanisms: Dislocations, Twinning, TRIP and Phase Transformations

5.3. Strain Hardening, Work-Softening and Toughening Strategies

5.4. Fatigue and Cyclic Deformation: Initiation, Small-Crack Growth and Life Prediction

5.5. High-Temperature Performance and Creep Resistance

5.6. Fracture Mechanics: Crack-Tip Processes and Microstructural Design for Toughness

5.7. Size Effects, Nanostructuring and Interface Engineering

5.8. Modeling, Data Integration and Predictive Property Design

5.9. Outlook and Research Needs

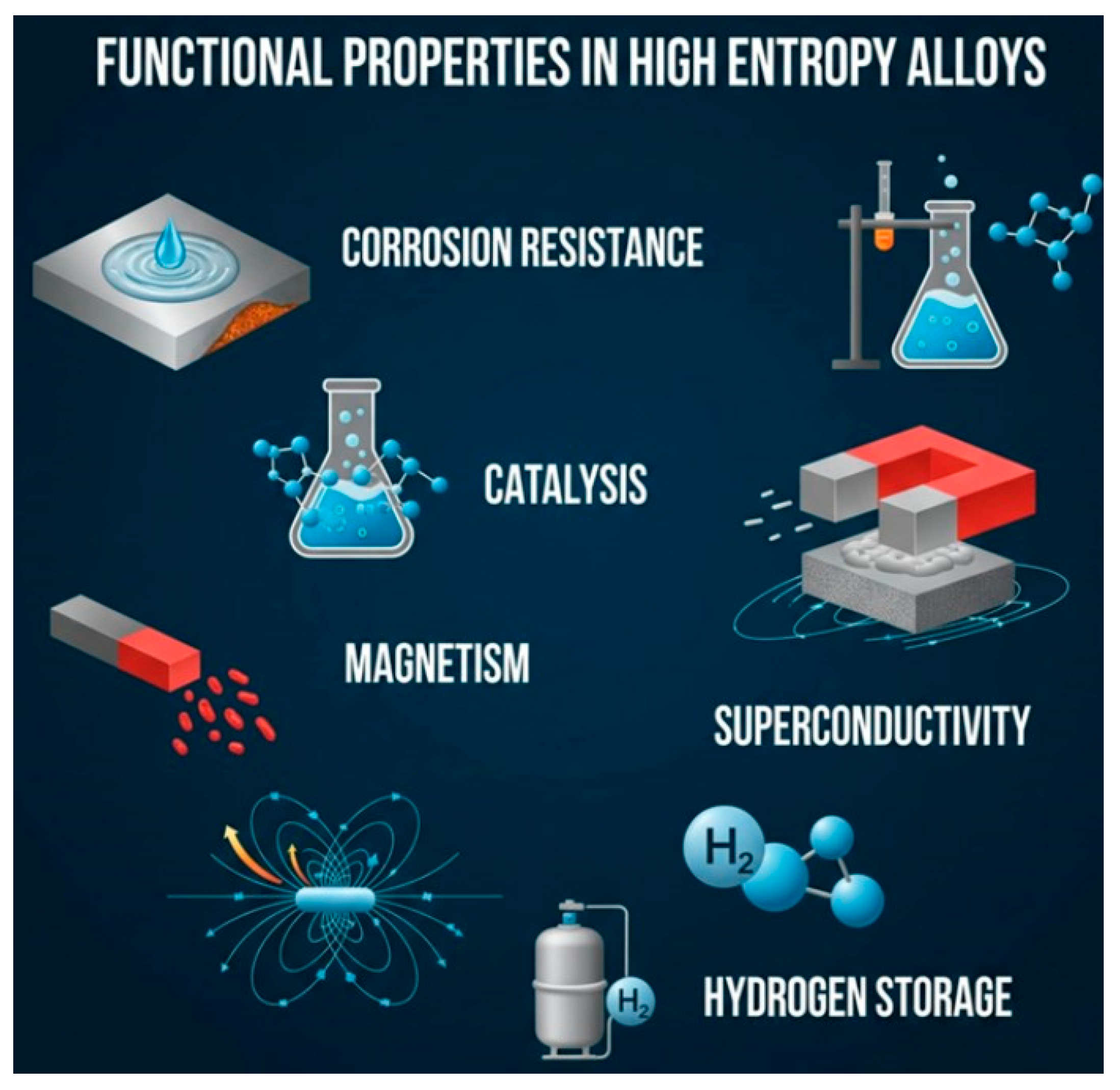

6. Chemical and Functional Properties

6.1. Electronic Transport and Thermoelectric Behavior

6.2. Thermal Conduction and Phonon Scattering

6.3. Corrosion and Oxidation Resistance

6.4. Catalytic and Electrocatalytic Activity

6.5. Magnetic and Spin-Related Phenomena

6.6. Superconductivity

6.7. Hydrogen Storage and Hydrogen-Interaction Phenomena

6.8. Radiation Tolerance and Defect Physics

6.9. Electronic Structure, Modeling and Design Principles

6.10. Diffusion Coefficients and Transport Phenomena

6.11. Stacking Fault Energy (SFE), Deformation Mechanisms and Phase Stability

6.12. Thermal Expansion in High Entropy Alloys

6.13. Grain Boundaries and Functional Properties of High-Entropy Alloys

6.14. Outlook and Unresolved Challenges

- Mass or volume reduction: e.g., if a HEA coating or thin structural element halves component mass while retaining functionality, the net system cost may fall when system-level costs (fuel, inertia, installation) dominate.

- Extended service life: in offshore, chemical or high-temperature environments a 3–5× extension in replacement interval converts into strong net present value (NPV) gains even when material unit cost is higher.

- Energy efficiency gains: functional HEAs used in thermoelectric or catalytic roles that improve conversion efficiency by a few percentage points can pay back material costs over device lifetimes if the energy value is high (grid-scale or industrial heat recovery).

- Capability enabling: certain HEA combinations enable functionalities (e.g., simultaneous corrosion resistance and high saturation magnetization) not achievable with conventional alloys; such unique capabilities permit premium pricing analogous to specialty ceramics or rare magnets.

7. Applications and Future Perspectives

7.1. Introduction

7.2. Structural and Load-Bearing Applications (Aerospace, Automotive, Tooling)

7.3. High-Temperature and Refractory Uses (Power Generation, Turbines)

7.4. Wear, Tribology and Protective Coatings

7.5. Energy, Corrosion Resistance and Electrochemical Applications

7.6. Catalysis, Nanoparticles and Functional Surface Materials

7.7. Additive Manufacturing, Joining and Component Integration

7.8. Biomedical and Implantable Uses

7.9. Radiation Resistance and Nuclear Applications

7.10. Functional Applications—Magnetic, Electronic, and EMI Shielding

7.11. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

7.12. Performance Metrics and Economic Considerations Regarding HEAs Applications

7.13. Concluding Remarks

8. Challenges and Opportunities

8.1. Cost, Sustainability, and Industrial Viability

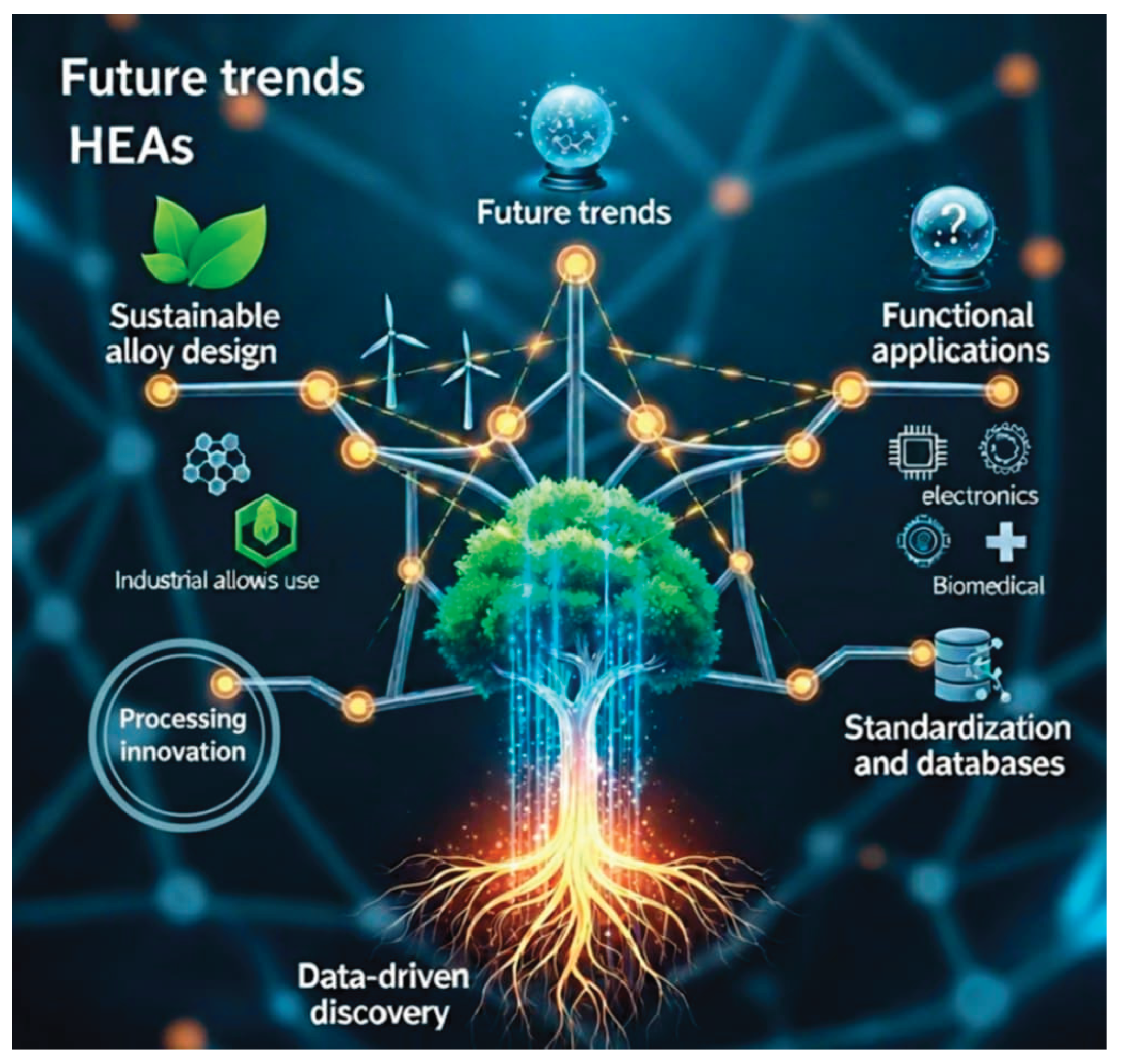

8.2. Future Directions and Integrative Strategies

- (i)

- Data-driven discovery. Machine learning (ML) and high-throughput computational frameworks are rapidly maturing and now play a central role in narrowing the HEA compositional space [290]. By integrating CALPHAD-based thermodynamics with ab initio calculations and ML predictors, researchers have begun to propose design frameworks that can screen thousands of candidate alloys in days, reducing reliance on costly trial-and-error experiments [291].

- (ii)

- Processing innovation. Improving process control is critical to industrial adoption. AM routes are expected to mature, with better control of powder composition and melt pools, while hybrid approaches combining AM and heat treatments are being explored to enhance microstructural uniformity [292]. Powder metallurgy may benefit from sustainable feedstock strategies, such as recycling industrial scrap into HEA powders [293,294].

- (iii)

- Sustainable alloy design. Next-generation HEAs will increasingly incorporate sustainability as a design criterion. Instead of optimizing purely for performance, alloys will be engineered for recyclability, low environmental footprint, and reduced reliance on critical elements [295]. For example, Fe-based HEAs enriched with Mn, Al, and Cr have been identified as low-cost alternatives for corrosion-resistant applications [296].

- (iv)

- Functional applications. While structural alloys dominate current HEA research, functional HEAs in catalysis [297], energy storage [298], superconductivity [299], and EMI shielding [300] are emerging rapidly. These applications often require only small quantities of material, which alleviates cost pressures and accelerates early commercialization.

- (v)

- Standardization and databases. The absence of standardized datasets remains a major bottleneck [301]. For example, a serious limitation in applying machine learning to high-entropy alloy design is the absence of standardized datasets encompassing critical material descriptors. Phase stability information-identifying single-phase versus multiphase structures (FCC, BCC, HCP) with explicit temperature and processing context-is often inconsistently reported, undermining predictive accuracy. Similarly, precise elemental compositions, including minor impurities, are rarely uniformly documented, complicating model generalization. Thermodynamic descriptors such as mixing enthalpy, entropy, valence electron concentration, and atomic size mismatch are frequently calculated with differing conventions, further fragmenting data integration. Processing history-including synthesis methods, cooling rates, and annealing protocols-is usually omitted or inconsistently described, despite its strong influence on microstructure and properties. Finally, mechanical and functional properties, such as tensile strength, hardness, and corrosion resistance, are measured under varying conditions, reducing the reliability of cross-study comparisons. Collectively, the lack of standardized reporting in these parameters represents a critical bottleneck for robust, generalizable machine learning models in HEA research.

8.3. Concluding Perspective

References

- Chen, W.; Hilhorst, A.; Bokas, G.; Gorsse, S.; Jacques, P.J.; Hautier, G. A Map of Single-Phase High-Entropy Alloys. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind Krishna, S.; Noble, N.; Radhika, N.; Saleh, B.S. A Comprehensive Review on Advances in High-Entropy Alloys: Fabrication, Properties, Applications, and Future Prospects. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 109, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odetola, P.I.; Babalola, B.J.; Afolabi, A.E.; Anamu, U.S.; Olorundaisi, E.; Umba, M.C.; Phahlane, T.; Ayodele, O.O.; Olubambi, P.A. Exploring High-Entropy Alloys: A Review on Thermodynamic and Computational Modeling Strategies for Advanced Materials Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.V.; Sundaram, R.; Hema, M.; Radhika, N. Recent Advancements in Lightweight High-Entropy Alloys. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2024, 33, 101432. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Huang, D.; Wang, W.; Dou, G.; Lyu, P. Recent Advances in High-Temperature Properties of High-Entropy Alloys. High-Temp. Mater. 2025, 2, 10011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Huang, L.; Wu, C.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Kong, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; et al. Microstructure and Mechanical Performance Study of CrMnFeCoNi High-Entropy Alloys After Cryogenic Treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 942, 148663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugale, M.; Karki, S.; Choudhari, A.; Digole, S.; Garg, M.; Kandadai, V.A.S.; Walunj, G.; Jasthi, B.K.; Borkar, T. High Strength-Ductility Combination in Low-Density Dual Phase High Entropy Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Ehsan, M.T.; Das Suvro, S.; Hasan, M.N.; Islam, Μ. Enhancing Creep Resistance in Refractory High-Entropy Alloys: Role of Grain Size and Local Chemical Order. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.00588. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ji, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H. High-Temperature Structural and Mechanical Stability of Refractory High-Entropy Alloy Nb40Ti25Al15V10Ta5Hf3W2. Mater. Charact. 2023, 205, 113321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, M. Tracer Diffusion in CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy. Acta Mater. 2018, 146, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Yuan, H.; Cheng, G.; Xu, W.; Tsai, K.Y.; Tsai, C.W.; Jian, W.W.; Juan, C.C.; Shen, W.J.; Chuang, M.H.; et al. Morphology, Structure and Composition of Precipitates in Al0.3CoCrCu0.5FeNi High-Entropy Alloy. Intermetallics 2013, 32, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Dlouhý, A.; Somsen, C.; Bei, H.; Eggeler, G.; George, E.P. The Influences of Temperature and Microstructure on the Tensile Properties of a CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 5743–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ζ.K. Thermodynamics and its Prediction and CALPHAD Modeling: Review, State of the Art, and Perspectives. Calphad 2023, 82, 102580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Cheng, X. Machine Learning-Assisted Design of High-Entropy Alloys with Superior Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 260–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkatatny, S.; Abd-Elaziem, W.; Sebaey, T.A.; Darwish, M.A.; Hamada, A. Machine-Learning Synergy in High-Entropy Alloys: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 3976–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Chen, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Peng, X.; Guo, L.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Q. High-Strength Fe32Cr33Ni29Al3Ti3 Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2023, 17, 3701–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, M.; Meibody, A.P.; Saboori, A.; Iuliano, L. Challenges and Opportunities in Additive Manufacturing of High Entropy Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1034, 181450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xiao, X.; Zeng, D.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Liu, W.; Zhang, K. Influence of Al Content on the Microstructure and Performance of AlxCoCrFeNi2.1 High-Entropy Alloys via Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, O.A.; Ryu, H.J. Powder Metallurgy Processing of a WxTaTiVCr High-Entropy Alloy and Its Derivative Alloys for Fusion Material Applications. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L. Advanced Development of High-Entropy Alloys in Catalytic Applications. Small Methods 2025, e2500411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolar, S.; Ito, Y.; Fujita, T. Future Prospects of HEAs as Next-Generation Industrial Electrode Materials. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 8664–8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhu, H. Surface-Engineered Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys for Advanced Electrocatalysis. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gao, X.; Yao, Y.; Hu, S.; Li, Z.; Teng, Y.; Wang, H.; Gong, H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Υ. Nanostructured High Entropy Alloys as Structural and Functional Materials. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Srivastawa, K.; Jana, S.; Dixit, C. Advancements in Lightweight Materials for Aerospace Structures: A Comprehensive Review. Acceleron Aerospace. J. 2024, 2, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelima, P.; Narayana Murthy, S.V.S.; Chakravarthy, P.; Srivatsan, T.S. High Entropy Alloys: Challenges in Commercialization and the Road AHEAD. In High Entropy Alloys; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 473–546. [Google Scholar]

- Zhichao, L.; Ding, M.; Xionjun, L.; Lu, Z. High-Throughput and Data Driven Machine Learning Techniques for Discovering High-Entropy Alloys. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, B. A Review on Recent Progress of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys: From Fundamental Research to Engineering Applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 1097–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnisi, B.O.; Benecha, E.M.; Tibane, M.M. Density functional theory study of phase stability and electronic properties for L12 X3Ru and XRu3 alloys. Eur. Phys. J. B 2025, 98, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fultz, B. Vibrational Thermodynamics of Materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2010, 55, 247–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Korzhavyi, P.A. First Principles Investigation on Thermodynamic Properties and Stacking Fault Energy of Paramagnetic Nickel at High Temperatures. Metals 2020, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizia, J. Disordered Local Moments and the Thermodynamic Properties of the Hubbard Model in the d Metals. J. Phys. F Met. Phys. 1982, 12, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Grabowski, B.; Körmann, F.; Neugebauer, J.; Raabe, D. Ab Initio Thermodynamics of the CoCrFeMnNi High Entropy Alloy: Importance of Entropy Contributions Beyond the Configurational One. Acta Mater. 2015, 100, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deák, A.; Simon, E.; Balogh, L.; Szunyogh, L.; dos Santos Dias, M.; Staunton, J.B. Metallic Magnetism at Finite Temperatures Studied by Relativistic Disordered Moment Description: Theory and Applications. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 224401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O. A Critical Review of High-Entropy Alloys and Related Concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Yeh, J.W. High-Entropy Alloys: A Critical Review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2014, 2, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Liaw, P.K.; Gao, M.C.; Widom, M. First-Principles Prediction of High-Entropy-Alloy Stability. Acta Mater. 2020, 195, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, S.; Mosbacher, M.; Senkov, O.N.; Feuerbacher, M.; Freudenberger, J.; Gezgin, S.; Völkl, R.; Glatzel, U. Entropy Determination of Single-Phase High-Entropy Alloys. Entropy 2023, 25, 870. [Google Scholar]

- Samolyuk, G.D.; Osetsky, Y. N.; Stocks, G. M.; Morris, J. R.; Role of Static Displacements in Stabilizing BCC High Entropy Alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 025502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, Y. The CALPHAD Approach for HEAs: Challenges and Opportunities. MRS Bull. 2022, 47, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, C.T. Phase Stability in High Entropy Alloys: Formation of Solid-Solution Phase or Amorphous Phase. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mat. Int. 2011, 21, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, S.; Tucker, V.; Titus, M.S.; Wagner, G.J. A High-Throughput Physics-and Data-Driven Framework for High-Entropy Alloy Development. Acta Mater. 2025, 292, 121045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, B.; Fang, Q.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Liaw, P.K. High-Throughput Simulation Combined Machine Learning Search for Optimum Elemental Composition in Medium Entropy Alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 68, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.F.; Wang, Q.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.T.; Yang, Y. Design of High Entropy Alloys: A Single-Parameter Thermodynamic Rule. Scripta Mater. 2015, 104, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and Properties of High-Entropy Alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, A.R.; De Boer, A.R.; De Chatel, P.F. Empirical Description of the Role of Electronegativity in Alloy Formation. J. Phys. F Met. Phys. 2001, 3, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsanov, S.S. Energy, Electronegativity and Chemical Bonding. Molecules 2022, 27, 8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łach, Ł. Phase Stability and Transitions in High-Entropy Alloys: Insights from Lattice Gas Models. Comput. Simul. Exper. Valid. Entropy 2025, 27, 464. [Google Scholar]

- Teggin, L.S.E.; Cochrane, R.F.; Mullis, A.M. Characterisation of Phase Separation in Drop-Tube-Processed Rapidly Solidified CoCrCuFeNi0.8 High-Entropy Alloy. High Entropy Alloys Mater. 2024, 2, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Katiyar, N.K.; Goel, S. Phase Prediction and Experimental Realisation of a New High Entropy Alloy Using Machine Learning. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, C.; Hu, Y.J.; Qi, L.; Liaw, P.K. Mining of Lattice Distortion, Strength, and Intrinsic Ductility of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starikov, S.; Grigorev, P.; Drautz, R.; Sergiy, V.; Divinski, S.V. Large-Scale Atomistic Simulation of Diffusion in Refractory Metals and Alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 043603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Giles, S.A.; Sengupta, D.; Rajan, K.; Broderick, S.R. Atomic Interaction-Based Prediction of Phase Formations in High-Entropy Alloys. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 24560–24575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Yang, S.; Ren, J.C.; Liu, W. Electronic Descriptors for Designing High-Entropy Alloy Electrocatalysts by Leveraging Local Chemical Environments. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Tsukada, Y.; Abe, T. Simple Approach for Evaluating the Possibility of Sluggish Diffusion in High-Entropy Alloys. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2022, 43, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcik, I.; Zeleny, M.; Dlouhy, A.; Hadraba, H.; Moravcikiva-Gouvea, L.; Papez, P. Impact of Interstitials Elements on the Stacking Fault Energy of an Equiatomic CoCrNi Medium Entropy Alloy: Theory and Experiments. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2022, 23, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antillon, E.; Woodward, C.; Rao, S.I.; Akdim, B.; Parthasarathy, T.A. Chemical Short Range Order Strengthening in a Model FCC High Entropy Alloy. Acta Mater. 2020, 190, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, C.E.; Mazanova, V.; Kumar, P.; Cook, D.H.; Heczko, M.; Yu, Q.; Crossman, B.; George, E.P.; Mills, M.J.; Ritchie, R.O. Partially Recrystallized Microstructures Expand the Strength-Toughness Envelope of CoCrNi Medium W trophy Alloy. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, S.; Pan, Y. Dual-Phase WNbTaV Refractory High-Entropy Alloy with Exceptional Strength and Hardness Fabricated via Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Tian, K.; Li, X.; Duan, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Zheng, R.; Liu, Y. Amorphous High-Entropy Non-Precious Metal Oxides with Surface Reconstruction Toward Highly Efficient and Durable Catalyst for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 606, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.; Jain, S.; Dewangan, S.K.; Boriwal, L.K.; Samal, S. Machine Learning-Driven Insights Into Phase Prediction for High Entropy Alloys. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 8, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokas, G.B.; Chen, W.; Hilhorst, A.; Jacques, P.J.; Gorsse, S.; Hautier, G. Unveiling the Thermodynamic Driving Forces for High Entropy Alloys Formation Through Big Data Ab Initio Analysis. Scripta. Mater. 2021, 202, 114000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolar, S.; Ito, Y.; Fujita, Τ. Future Prospects of High-Entropy Alloys as Next-Generation Industrial Electrode Materials. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 8664–8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.A.; Dou, Y.K.; He, X.F. Atomistic Study on the Effects of Short-Range Order on the Creep Behavior of TiVTaNb Refractory High-Entropy Alloy at High Temperature. Acta Mech. Sin. 2025, 41, 124478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K.; Yeh, J.-W.; Bhattacharjee, P.P.; DeHosson, J.T.M. High Entropy Alloys: Key Issues Under Passionate Debate. Scr. Mater. 2020, 188, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldabah, N.M.; Pratap, A.; Pandey, A.; Sardana, N.; Sidhu, S.S.; Gepreel, M.A.H. Design Approaches of High-Entropy Alloys Using Artificial Intelligence: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Waghmare, U.V. Entropic Stabilization and Descriptors of Structural Transformation in High Entropy Alloys. Acta Mater. 2023, 255, 119077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Components—Process, Structure and Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Yang, C. AI Design for High Entropy Alloys: Progress, Challenges and Future Prospects. Metals 2025, 15, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yang, B.; Liu, A.; Zhu, Ε.; Zhang, W. Machine Learning-Driven Design of High-Entropy alloys: Phase Prediction, Performance Optimization, and Challenges. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Pan, Y.; Cai, F.; Gao, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Q.; Li, P.; Jin, Z.; Jiang, J.; et al. Accelerating the Discovery of Efficient High-Entropy Alloy Electrocatalysts: High-Throughput Experimentation and Data-Driven Strategies. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 11632–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, B.; Shu, J. Accelerated Development of Hard High-Entropy Alloys with Data-Driven High-Throughput Experiments. J. Mater. Inform. 2022, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.C. Accelerating the Exploration of High-Entropy Alloys: Synergistic Effects of Integrating Computational Simulation and Experiments. Small Struct. 2024, 5, 2400110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ni, J. Machine Learning Advances in High-Entropy Alloys: A Mini Review. Entropy 2024, 26, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, V.; Yu, Z.G.; Chen, S.; Tan, T.L.; Aitken, Z.; Zhang, Y. W First Principles–Based Design of Lightweight High-Entropy Alloys. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Zhao, S.; Detroit, M.; Jablonski, P.D.; Hawk, J.A.; Alman, D.E.; Asta, M.; Minor, A.M.; Gao, M.C. Theory-Guided Design of High-Entropy Alloys with Enhanced Strength-Ductility Synergy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; OH, C.S.; Choi, Y.S. Improved Phase Prediction of High-Entropy Alloys Assisted by Imbalance Learning. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, V.; Yu, Z.G.; Chen, S.; Tan, T.L.; Aitken, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.W. A First-Principles-Based High Fidelity, High Throughput Approach for the Design of High-Entropy Alloys. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunger, A.; Wei, S.-H.; Ferreira, L.G.; Bernard, J.E. Special Quasirandom Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 65, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.-H.; Ferreira, L.G.; Bernard, J.E.; Zunger, A. Electronic Properties of Random Alloys: Special Quasirandom Structures. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 42, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F. A Review of Solid-Solution Models of High-Entropy Alloys Based on Ab Initio Calculations. Front. Mater. 2017, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C.; Niu, C.; Yeh, J.W. Applications of Special Quasi-random Structures to High-Entropy Alloys. In High-Entropy Alloys; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 333–368. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate, G.; Staunton, J.B. Short-Range Order and Compositional Phase Stability in Refractory High-Entropy Alloys via First-Principles Theory and Atomistic Modelling: NbMoTa, NbMoTaW and VNbMoTaW. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2023, 7, 013801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Artificial Intelligence in High-Entropy Materials. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldabah, N.B.; Pratap, A.; Pandey, A.; Sardana, N.; Sidhu, S.S.; Gepreel, M.A.H. Design Approaches for HEAs Using Artificial Intelligence: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębski, R.; Gąsior, W.; Gierlotka, W.; Dębski, A. Uncertainty-Aware Design of High-Entropy Alloys via Ensemble Thermodynamic Modeling and Search Space Pruning. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, S.; FAN, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Liaw, P.K. CALPHAD-Aided Design for Superior Thermal Stability and Mechanical Behavior in a TiZrHfNb Refractory High-Entropy Alloy. Acta Mater. 2023, 246, 118728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukkari, P.; Blomberg, P. Extents of Reaction as Supplementary Constraints for Gibbs Energy Minimization. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 295, 120112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, M.; Dematteis, E.M.; Fenocchio, L. Advances in CALPHAD Methodology for Modeling Hydrides: A Comprehensive Review. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2024, 45, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J.M.; Kalchev, Y.; Fantin, A.; Crivello, J.C.; Zehl, R.; Elkaim, E.; Laplanche, G. Site Occupancies in a Chemically Complex σ-Phase from the High-Entropy Cr–Mn–Fe–Co–Ni System. Acta Mater. 2023, 259, 119277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, A.; Tan, X.; Hu, S.; Gao, M.C. CALPHAD-Based Bayesian Optimization to Accelerate Alloy Discovery for High-Temperature Applications. J. Mater. Res. 2025, 4, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sheriff, K.; Freitas, R. Capturing Short-range Order in High-Entropy Alloys with Machine-Learning Potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C.; Gao, P.; Hawk, J.A.; Ouyang, L.; Alman, D.E.; Widom, M. Computational Modeling of High-Entropy Alloys: Structures, Thermodynamics and Elasticity. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 3627–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.M. Cluster Expansion and the Configurational Theory of Alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 224202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tran, N.D.; Sun, Y.; Lu, Y.; Hou, C.; Chen, Y.; Ni, J. Cluster Expansion Augmented Transfer Learning for Property Prediction of High-Entropy Alloys. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 17601–17615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Fan, D.; Lei, Z.; Xu, P.; Tian, Y. Revealing Nanostructures in High-Entropy Alloys via Machine Learning Accelerated Scalable Monte Carlo Simulation. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, T. A Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials for High-Entropy Alloys. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2024, 187, 105639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z. Machine Learning Interatomic Potential: Bridge the Gap Between Small-Scale Models and Realistic Device-Scale Simulations. iScience 2024, 27, 109673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulichenko, M.; Nebgen, B.; Lubbers, N.; Smith, J.S.; Barron’s, K.; Allen, A.E.A.; Habib, A.; Shinkle, Ε.; Fedik, N.; Li, Y.W.; et al. Data Generation for Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 13681–13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barman, S.; Dey, S. Probing the Mechanical and Deformation Behaviour of CT-Reinforced AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy A Molecular Dynamics Approach. Mol. Simul. 2023, 49, 1726–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Kumar, S. Breaking Data Barriers: Advancing Phase Prediction in High Entropy Alloys Through a New Machine Learning Framework. Can. Metal. Q 2025, 64, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xing, L.; Cheng, X. Research on Performance Prediction Method of Refractory High-Entropy Alloy Based on Ensemble Learning. Metals 2025, 15, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, G.; Chakravarty, S.; Gurrola, R.; Arróyave, R. A Deep Neural Regressor for Phase Constitution Estimation in the High Entropy Alloy System Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Nb-Ni. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Song, Z.; Wang, J.; Niu, X.; Chen, X. Enhanced Phase Prediction of High-Entropy Alloys Through Machine Learning and Data Augmentation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 717–729. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.; Babuska, T.; Kick, B.; Balasubramanian, G. Machine Learned Feature Identification for Predicting Phase and Young’s Modulus of Low-, Medium-and high-entropy alloys. Scripta Mater. 2020, 185, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazani, B. Recent advances in Machine Learning-Assisted Multiscale Design of Energy Materials. Adv. En. Mater. 2025, 15, 2403876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, M.; Orhan, O.K.; Shin, H.; Malek, A.; Ponga, M. GAPF-DFT: A Graph Based Alchemical Perturbation Density Functional Theory for Catalytic High Entropy Alloys. npj. Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, S.; Ding, J.; Chong, Y.; Jia, T.; Ophus, C.; Asta, M.; Ritchie, R.O.; Minor, A.M. Short-Range Order and its Impact on the CrCoNi Medium Entropy Alloy. Nature 2020, 581, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhichao, L.; Dong, M.; Xiongjun, L.; Lu, Z. High-Throughput and Data-Driven Machine Learning Techniques for Discovering High-Entropy Alloys. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bocklund, B.; Diffenderfer, J. A Comparative Study of Predicting High Entropy Alloy Phase Fractions with Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Neural Networks. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, M. First-Principles Study of the Order-Disorder Transition in the AlCrTiV High Entropy Alloy. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 093603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Quan, G.Z.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Y.Z.; Xiong, W. A Review on Controlling Grain Boundary Character Distribution during Twinning-Related Grain Boundary Engineering of Face-Centered Cubic Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, N. High-Entropy Grain Boundaries. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dösinger, C.; Hodapp, M.; Peil, O.; Reichmann, A.; Razumovskiy, V.; Scheiber, D.; Romaner, L. Efficient Descriptors and Active Learning for Grain Boundary Segregation. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2023, 7, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazitov, A.; Springer, M.A.; Lopanitsyna, N.; Fraux, G.; De, S.; Ceriotti, M. Surface Segregation in High-Entropy Alloys from Alchemical Machine Learning. J. Phys. Mater. 2024, 7, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei, M.H.; Zohrevand, M.; Zhang, N. Applications of Machine Learning in High-Entropy Alloys: A Review of Recent Advances in Design, Discovery, and Characterization. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 20548–20605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Barr, E.; Aidhy, D. Consolidated Database of High Entropy Materials (COD’HEM): An Open Online Database of High Entropy Materials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 248, 113588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsse, S.; Langlois, T.; Yeh, A.C. Sustainability Indicators in High Entropy Alloy Design: An Economic, Environmental, and Societal Database. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, H.; Aydin, F.; Carpenter, T.S.; Lightstone, F.C.; Bremer, P.T.; Ingólfsson, H.I.; Nissley, D.V.; Streitz, F.H. The Confluence of Machine Learning and Multiscale Simulations. Cur. Op. Struct. Bio. 2023, 80, 102569. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Ren, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, W.; Morita, K.; Zhang, S.; Lei, Y.; Lv, G.; Li, S.; Wu, J. Recent Progress in High-Entropy Alloys: A Focused Review of Preparation Processes and Properties. J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2024, 29, 2689–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Progress in Additive Manufacturing of High-Entropy Alloys. Materials 2024, 17, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagirici, M.; Guo, S.; Ding, J.; Ramamurty, U.; Wang, P. Additive Manufacturing of High-Entropy Alloys: Current Status and Challenges. Smart Mater. Manuf. 2024, 2, 10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujah, C.O.; Kallon, D.V.V.; Aigbodion, V.S. High-Entropy Alloys Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering: Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 25, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ma, H.; Spolenak, R. Ultrastrong Ductile and Stable High-Entropy Alloys at Small Scales. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Tsai, R.-C.; Chang, T.; Huang, W.-F. Intermetallic Phases in High-Entropy Alloys: Statistical Analysis of their Prevalence and Structural Inheritance. Metals 2019, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, P.K.; Yoshida, S.; Sunkari, U.; Tripathy, B.; Tsuji, N.; Bhattacharjee, P.P. Highly Deformable Laves Phase in a High Entropy Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2024, 240, 115828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Nagarjuna, C.; Lee, H.; Rao, K.R.; Mohan, M.; Jain, R.; Ahn, B. Advances in Powder Metallurgy for High-Entropy Alloys. J. Powder Mater. 2024, 31, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrotzki, W.; Chukist, R. Severe Plastic Deformation of High-Entropy Alloys. Mater. Trans. 2023, 64, 1769–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H.; He, Q.; Fang, Q.; Liu, X.; Jia, L.; Yang, Y. Overcoming Strength–Toughness Trade-Off in a Eutectic High-Entropy Alloy by Optimizing Chemical and Microstructural Heterogeneities. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkodich, N.F.; Smoliarova, T.; Ali, H.; Eggert, B.; Rao, Z.; Spasova, M.; Tarasov, I.; Wende, H.; Ollefs, K.; Gault, B.; et al. Effect of High Energy Ball Milling, Heat Treatment and Spark Plasma Sintering on Structure, Composition, Thermal Stability and Magnetism in CoCrFeNiGax (x = 0.5; 1) High Entropy Alloys. Acta Mater. 2025, 284, 120569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Lin, D.; Tang, Z. Eutectic High-Entropy Alloys and Their Applications in Materials Processing Engineering: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2024, 189, 211–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Comprehensive Review on High-Entropy Alloy-Based Coatings. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2024, 477, 130327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, A.; Anupam, A.; Murty, B.S.; Bernd, C.C.; Kottada, R.S.; Ming Ang, A.S. Thermal Spray High-Entropy Alloy Coatings: A Review. J. Thermal. Spray Technol. 2020, 29, 857–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Song, A.; Gebert, K.; Neufeld, I.; Kaban, H.; Ma, W.; Cai, H.; Lu, D.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; et al. Yang, Programming Crystallographic Orientation in Additive-Manufactured Beta-Type Titanium Alloy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 22302884. [Google Scholar]

- Wakai, A.; Bustillos, J.; Sargent, N.; Stokes, J.L.; Xiong, W.; Smith, T.M.; Moridi, A. Harnessing Metastability for Grain Size control in Multiprincipal Element Alloys During Additive Manufacturing. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chabok, A.; Kooi, B.J.; Pei, Y. Additive Manufactured High Entropy Alloys: A Review of the Microstructure and Properties. Mater. Des. 2022, 220, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, Q.; Jia, D.; Fu, Y.; Wu, X. Review on the Preparation and Properties of High-Entropy Alloys Coating. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 945, 149009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.R.; Peng, Z. Review and Perspective on Additive Manufacturing of Refractory HEAs. Mater. Today Adv. 2024, 23, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwekomi, A.D.; Bamisaye, O.S.; Bidunrin, M.O. Powder Metallurgy Processing of High-Entropy Alloys: Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2024, 63, 20230188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, S.N.; Sahoo, S.K.; Haase, C.; Barrales-Mora, L.A.; Toth, L.S. Nano-Structuring of a HEA by SPD: Experiments and Crystal Plasticity Simulations. Acta Mater. 2023, 250, 118814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Zhou, T.; Liang, Z.; Liu, X. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Corrosion Resistance of Direct Energy Deposited AlCu0.25CoCrFeNi2.1 High Entropy Alloy: Tailored by Annealing Heat Treatment. Mater. Char. 2024, 213, 114035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural Development in Equiatomic Multicomponent Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oketola, A.M. Advances in High-Entropy Alloy Research: Unraveling Fabrication Techniques, Microstructural Transformations, and Mechanical Properties. Metals 2025, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchioni, G. Designing Ductile Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 10, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Cai, W. From Fabrication to Mechanical Properties: Exploring High-Entropy Oxide Thin Films and Coatings for High Temperature Applications. Front. Coat. Dyes Interface Eng. 2024, 2, 1417527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.I. High-Entropy Alloys (Review). Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, W. Single-Phase High-Entropy Alloys—A Critical Update. Mater. Charact. 2020, 162, 110179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D.; Chaput, K.J.; Couzinie, J.P. Development and Exploration of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys-A Review. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, T.; Shirizly, A.; Aghion, E. Additive Manufacturing Technologies of High Entropy Alloys (HEA): Review and Prospects. Materials 2023, 16, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkan, D.; Dilibal, S. High-Entropy Alloys in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Adv. Manuf. Res. 2025, 3, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.; Moghadam, A.O.; Anandkumar, M.; Sudarsan, S.; Bodrov, E.; Samodurova, M.; Trofimov, E. Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of High-Entropy Alloys Through Severe Plastic Deformation: A Review. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 5, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastola, N.; Jahan, M.P.; Rangasamy, N.; Rakurty, C.S. A Review of the Residual Stress Generation in Metal Additive Manufacturing: Analysis of Cause, Measurement, Effects, and Prevention. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Lin, W.; Guo, H. Research Progress on Tribological Properties of High-Entropy Alloys. Lubricants 2025, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, M.; Li, T.; Wei, X.; Lu, Y. A Critical Review of the Mechanical Properties of CoCrNi. Microstr. 2022, 2, 2022001. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; He, F.; Li, J.; Kim, H.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Phase-Selective Recrystallization Makes Eutectic High-Entropy Alloys Ultra-Ductile. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.W.; Qiao, J.W.; Hawk, J.A.; Zhou, H.F.; Chen, M.W.; Gao, M.C. Mechanical Properties of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys: Experiments and Modelling. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 696, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Qiu, S.; Jiao, Z.B. Atomic-Scale Understanding of Interstitial-Strengthened High-Entropy Alloys. Rare Mer. 2025, 44, 6002–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, I.; Grabowski, B.; Divinski, S.V. Interstitials in Compositionally Complex Alloys. MRS Bulletin. 2023, 48, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tasan, C.; Springer, H.; Gault, Β.; Raabe, D. Interstitial Atoms Εnable Joint Twinning and Transformation Induced Plasticity in Strong and Ductile High-Entropy Alloys. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 40704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Xiong, W.; Chen, J.; Tan, M. Effects of Annealing Temperatures on Mechanical Behavior and Penetration Characteristics of FeNiCoCr High-Entropy Alloys. Metals 2022, 12, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, B.; Zhao, C. Improvement of Work-Hardening Capability and Strength of FeNiCoCr-Based High-Entropy Alloys by Modulation of Stacking Fault Energy and Precipitation Phase. Int. J. Plast. 2025, 185, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H.; He, Q.; Fang, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Overcoming Strength–Toughness Trade-Off in a Eutectic High-Entropy Alloy. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhor, A.; Sohrabi, M.J.; Mirzadeh, H.; Aghdam, M.Z.; Mehranpour, Μ.S.; Rodak, Κ.; Kim, H.S. Improving the Mechanical Properties of High-Entropy Alloys via Germanium Addition: A Focused Review. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodashenas, H.; Mirzadeh, H. Post-Processing of Additively Manufactured High-Entropy Alloys—A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 3795–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Ji, V. Mechanical Properties and Strengthening Mechanisms of FCC-Based and Refractory High-Entropy Alloys: A Review. Metals 2025, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghaz, A.; Rajabi, M.; Torabi, M.; Amirnejad, M. The Impressive Improvement of CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Mechanical Properties and Pitting Corrosion Resistance by Incorporating of Carbon Nanotube Reinforcement. Intermetallics 2023, 123, 108073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, E.; Meghwal, A.; Singh, S.; Munroe, P.; Berndt, C.C.; Siao Ming Ang, A. Empirical and Computational-Based Phase Predictions of Thermal Sprayed High-Entropy Alloys. J. Therm. Spray Tech. 2023, 32, 1840–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, P.; Pan, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L. Achieving Prominent High-Temperature Mechanical Performance in a Dual-Phase High-Entropy Alloy: A Synergy of Deformation-Induced Twinning and Martensite Transformation. Acta Mater. 2024, 264, 119591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pradeep, K.G.; Deng, Y.; Raabe, D.; Tasan, C.C. Metastable High-Entropy Dual-Phase Alloys Overcome the Strength–Ductility Trade-Off. Nature 2016, 534, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bei, H.; Pharr, G.M.; George, E.P. Temperature Dependence of the Mechanical Properties of Equiatomic Solid Solution Alloys with Face-Centered Cubic Crystal Structures. Nat. Commun. 2017, 5, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, M.C. Dislocation Core Structures and Mobility in Face-Centered Cubic High-Entropy Alloys. Acta Mater. 2019, 166, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Xue, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. Research Advances in Additively Manufactured High-Entropy Alloys: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance. Metals 2025, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, Q. An Overview on Fatigue of High-Entropy Alloys. Materials 2023, 16, 7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.Z.; Sun, S.J.; Lin, H.R.; Zhang, Z.F. Fatigue Behavior of CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy Under Fully Reversed Cyclic Deformation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.Y.; Tang, Z.Y.; Chu, F.B.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H.W.; Cao, D.D.; Jiang, L.; Ding, H. Elevated-Temperature Creep Properties and Deformation Mechanisms of a Non-Equiatomic FeMnCoCrAl High-Entropy Alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 3822–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelmeier, C.; Yang, Y.; Glatzel, U.; George, E.P. Creep Strength of Refractory High-Entropy Alloy TiZrHfNbTa and Comparison with Ni-base Superalloy CMSX-4. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 8–100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H. Diffusion in Ultra-Dine-Grained CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy Processed by Equal-Channel Angular Pressing. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 5805–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liaw, P.K. Nanoprecipitate-Strengthened High-Entropy Alloys. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 23–2100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Yang, T.; Liu, C.T. Precipitation Hardening in CoCrFeNi-based High Entropy Alloys. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2018, 210, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemali, E.; Sonkusare, R.; Biswas, Κ.; Gurao, Ν.P. In-situ Study of Crack Initiation and Propagation in a Dual Phase AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 710, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Koyama, M.; Hamada, S.; Tsuzaki, Κ.; Noguchi, H. Planar Slip-Driven Fatigue Crack Initiation and Propagation in an Equiatomic CrMnFeCoNi High-Entropy Alloy. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 133, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, A.; Nikniazi, A.; Gholamzadeh, H.; Yin, S.; Malekan, M.; Ahn, S.; Kim, H.; Balogh, L.; Ravkov, L.; Persaud, S.Y.; et al. Hot-Cracking Mitigation and Microcrack Formation Mechanisms in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Processed Hastelloy X and Cantor High Entropy Alloys. Met. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 3370–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Wu, X. Tailoring Heterogeneities in High-Entropy Alloys to Promote Strength–Ductility Synergy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodia, S.; Jai Sai, Ν.; Lu, K.; Knöpfle, F.; Zindal, A.; Aktaa, J.; Chauhan, A. Effective and Back Stress Evolution Upon Cycling Oxide-Dispersion Strengthened Steels. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 169, 107485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittiruam, M.; Noppakhun, J.; Setasuban, S. High-Throughput Materials Screening Algorithm Based on First-Principles Density Functional Theory and Artificial Neural Network for High-Entropy Alloys. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Guo, W.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Qiu, H. First-Principles Calculations of the Effect of Ta Content on the Properties of UNbMoHfTa High-Entropy Alloys. Metals 2025, 15, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Fensin, S.J.; Meyers, M.A. Strain-Rate Effects and Dynamic Behavior of High Entropy Alloys. J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2023, 22, 307–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Mahamudujjaman, M.; Afzal, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, R.S.; Naqib, S.H. DFT Based Comparative Analysis of the Physical Properties of Some Binary Transition Metal Carbides XC (X = Nb, Ta, Ti). J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2023, 24, 4808–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanayake, R.; Roy, U.C.; Pandit, A.; Bongiorno, A. First-Principles Calculation of Higher-Order Elastic Constants from Divided Differences. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2026, 318, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, E. First-Principles Calculation for Mechanical Properties of TiZrHfNbTa Series Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Mat. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 110165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yan, M.; Fu, Y. Theoretical Prediction of High Entropy Intermetallic Compound Phase via First Principles Calculations, Artificial Neuron Network and Empirical Models: A Case of Equimolar AlTiCuCo. Phys. B Cond. Mat. 2022, 646, 414275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, C.E.; Mazánová, V.; Kumar, P. Partially Recrystallized Microstructures Expand the Strength-Toughness Envelope of CrCoNi Medium-Entropy Alloy. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.; Cao, B.; Yu, S.; Wei, J. Review on the Tensile Properties and Strengthening Mechanisms of Additive Manufactured CoCrFeNi-Based High-Entropy Alloys. Metals 2024, 14, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Xiong, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Li, Z.; Feng, W. Mechanical Properties and Water Vapour Corrosion Behaviour of AlxCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 24741–24748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Gou, X.; Cook, D.H.; Payne, M.I.; Morrison, N.J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Asta, M.; Minor, A.M.; Cao, R.; et al. Degradation of the Mechanical Properties of NbMoTaW Refractory High-Entropy Alloy in Tension. Acta Mater. 2024, 279, 120297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Cao, Y.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Yang, Z.; Lin, J.; Chang, C. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of TixNbMoTaW Refractory High-Entropy Alloy for Bolt Coating Applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, N.F.; Czerwinski, F.; Chen, D. Present Challenges in Development of Lightweight High Entropy Alloys: A Review. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 39, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Nong, Z.S.; Cui, X.; Gu, Z.H.; Liu, T.; Li, H.M.; Arzikulov, E. Effect of Alloying on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AlCoCrFeNi2.1 Eutectic High-Entropy Alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, P.; Su, Y.-C.; Kuo, Υ.-Κ.; Lai, Y.-C.; Wu, S.-K. Physical Properties of Face-Centered Cubic Structured High-Entropy Alloys: Effects of NiCo, NiFe, and NiCoFe Alloying with Mn, Cr, and Pd. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 085003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigbedion, N.J. Comparative Thermal Response of CoCrMnFeNi High Entropy Alloy and Alumina Under Multi-Pulse Laser Heating. Results Mater. 2025, 26, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayandi, J.; Schrade, M.; Vajeeston, P.; Stange, M.; Lind, A.M.; Sunding, M.F.; Deuermeier, J.; Fortunato, E.; Løvvik, O.M.; Ulyashin, A.G.; et al. High Entropy Alloy CrFeNiCoCu Sputtered Films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 023402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuraman, V.; Wang, Y.; Widom, M. An Investigation of High Entropy Alloy Conductivity Using First-Principles Calculations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 121903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, R.; Sarker, S.; Borg, C.K.H.; Saal, J.; Ward, L.; Mehta, A.; Snyder, G.J. Mapping Thermoelectric Transport in a Multicomponent Alloy Space. Adv. El. Mater. 2022, 8, 2200327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Hu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Kawaguchi, S.; Machida, A.; Watanuki, Τ.; Fang, Y.-W.; Sun, J.; Ding, X.; et al. Integrating Abnormal Thermal Expansion and Ultralow Thermal Conductivity into (Cd,Ni)2Re2O7 via Synergy of Local Structure Distortion and Soft Acoustic Phonons. Acta Mater. 2024, 264, 119544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Υ.-W.; Zhang, G. Anomalous Component-Dependent Lattice Thermal Conductivity in MoWTaTiZr Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. iScience 2025, 28, 3112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, S.; Meena, P.K.; Atale, N.P.; Stewart, R.; Hillier, A.D.; Singh, R.P. Superconducting Properties of an Equiatomic Hexagonal High-Entropy Alloy via Muon Spin Relaxation and Rotation Measurement. Phys. Rev. 2025, 111, 214504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, S.; Zhao, W.; He, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Yang, Y. Exceptionally Low Thermal Conductivity in Distorted High Entropy Alloy. Mater. Res. Lett. 2024, 13, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Barzaga, G.; Urbassek, H.M.; Deluigi, O.R.; Pasinetti, P.M.; Brings, E.M. Chemical Short-Range Order Increases the Phonon Heat Conductivity in a Refractory High-Entropy Alloy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ren, T.-L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G. Actively and Reversibly Controlling Thermal Conductivity in Correlated Nanostructures. Phys. Rep. 2024, 1058, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. The Progress in the Coupling and Optimization of Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in High-Entropy Alloys. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 167, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, D.; Nie, C.; Gong, P.; Hu, Z.; Ma, M. Effect of Porosity on the Corrosion Behavior of FeCoNiMnCrx Porous High-Entropy Alloy in 3.5 Wt.% NaCl Solution. Metals 2025, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lv, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Chen, C.; Ju, D.; Che, L. Research Progress on the Influence of Alloying Elements on the Corrosion Resistance of High-Entropy Alloys. J. Alloys Compds. 2024, 1002, 175394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Wu, L.H.; Li, Z.K.; Fu, H.M.; Ni, D.R.; Xue, P.; Liu, F.C.; Xiao, B.L.; Ma, Z.Y. Simultaneously Increasing Mechanical and Corrosion Properties in CoCrFeNiCu High Entropy Alloy via Friction Stir Processing with an Improved Hemispherical Convex Tool. Mater. Charact. 2023, 203, 113143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangtong, P. The Corrosion Behaviour of Equiatomic CoCrFeNi and Related Alloys. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Savinov, R.; Shi, J. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Performance of Additively Manufactured CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy Before and After Heat Treatment. MSAM 2023, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhu, H. Surface-Engineered Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys for Advanced Electrocatalysis. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navi, A.S.; Haghighi, S.E.; Haghpanahi, M.; Momeni, A. Investigation of Microstructure and Corrosion of TiNbTaZrMo High-Entropy Alloy in the Simulated Body Fluid. J. Bionic Eng. 2021, 18, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, V.; Champion, Y.; Bataev, I.A.; Jorge, A.M. Junior, Passive Film Formation on the New Biocompatible Non-Equiatomic Ti21Nb24Mo23Hf17Ta15 High Entropy Alloy Before and After Resting in Simulated Body Fluid. Corr. Sci. 2022, 207, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellert, S.; Gorr, Β.; Laube, S.; Kauffmann, A.; Heilmaier, Μ.; Christ, H.J. Oxidation Mechanism of Refractory High Entropy Alloys Ta-Mo-Cr-Ti-Al with Varying Ta Content. Corros. Sci. 2021, 192, 109861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wen, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X.; Johannessen, B.; Zhang, S. High-Entropy Alloys in Catalysis: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. ACS Mater. Au. 2024, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Guo, X.; Cao, S.; Du, M.; Wang, Q.; Pi, Y.; Pang, H. High-Entropy Ag−Ru-Based Electrocatalysts with Dual-Active-Center for Highly Stable Ultra-Low-Temperature Zinc-Air Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 64, e202415216. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, F.; Fang, Υ.Q.; Kizilkaya, O.; Singh, P.; Johnson, D.D.; Roy, A.; Young, D.P.; Sprunger, P.T.; Flake, J.C.; Shelton, W.A.; et al. CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy as an Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution Catalyst in an Acidic Solution. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2021, 125, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, E.; Ji, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Web, Z. High Entropy Alloy Electrocatalytic Electrode Toward Alkaline Glycerol Valorization Coupling with Acidic Hydrogen Production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7224–7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yao, Υ.; Yu, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, C.; Zou, Ζ. Understanding the Enhanced Catalytic Activity of High Entropy Alloys: From Theory to Experiment. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 35, 19410–19438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Chau, H.; Stofik, S.; Gordon, M.N.; Fushimi, R.; Lauterbach, J.; Craps, Μ.; Rodene, D.D.; Aidhy, D. High Entropy Alloys as Catalysts: A Focused Review. Mater. Lett. 2025, 400, 139114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Gupta, A.Κ.; Mishra, R.K.; Ahmad, Μ.S.; Shahi, R.R. A Comprehensive Review: Recent Progress on Magnetic High Entropy Alloys and Oxides. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 554, 169142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, J.; Shintaku, D. Magnetic Properties of High-Entropy Alloy FeCoNiTi. ACS Omega. 2024, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, L.; Li, Κ.; Chen, R.; Luo, H. Recent Advances in High-Entropy Superconductors. NPG Asia Mater. 2024, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, P.; Rusin, B.; Gnida, D.; Pikul, A.; Idczak, R. Superconductivity in High-Entropy Alloy System Containing Tb. Materials. 2025, 18, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, M.; Uwatoko, Y.; Jing, Q.; Liu, B. Superconducting Ground State Properties on Equiatomic TaNbZrTi and TaNbHfZr Medium Entropy Alloys. J. Alloy Compd. 2025, 1036, 181813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.; Balcerzak, M.; Winkelmann, F.; Zepon, G.; Felderhoff, M. Review and Outlook on High-Entropy Alloys for Hydrogen Storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 5191–5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, T.P.; Kumar, A.; Verma, S.K.; Mukhopadhyay, N.K. High-Entropy Alloys for Solid Hydrogen Storage: Potentials and Prospects. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2022, 7, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhika, N.; Niketh, M.S.; Akhil, U.V.; Adediran, A.A.; Jen, T.C. High Entropy Alloys for Hydrogen Storage Applications: A Machine Learning-Based Approach. Res. Eng. 2024, 23, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhakhmetov, Y.; Skakov, M.; Kurbanbekov, S.; Uazyrkhaniva, G.; Kurmantayev, A.; Jizatov, A.; Mussakhan, N. High-Entropy Alloys: Innovative Materials with Unique Properties for Hydrogen Storage and Technologies for their Production. Metals 2025, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzhulov, B.; Ivanov, I.; Ugliv, V.; Zlotsky, S.; Ryskulov, A.; Kurakhmedov, A.; Sapar, A.; Ungarbayev, Y.; Koloberdin, M.; Zdorovets, M. Radiation Resistance of High-Entropy Alloys CoCrFeNi and CoCrFeMnNi, Sequentially Irradiated with Kr and He Ions. Materials 2024, 17, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiarpour, A.; Kalita, D.; Koziol, Z.; Alava, M. Comparative Study on Radiation Resistance of WTaCrV High-Entropy Alloy and Tungsten in Helium-Containing Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, C.; Shu, D.; Sun, B. A Review of Irradiation-Tolerant Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Metals 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooraj, S.; Chen, W. A Review on High-Throughput Development of High-Entropy Alloys by Combinatorial Methods. J. Mater. Inf. 2023, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.A.; Noble, N.; Radhika, N.; Saleh, B. A Comprehensive Review on Advances in High-Entropy Alloys: Fabrication and Surface Modification Methods, Properties, Applications and Future Prospects. J. Manuf. Proc. 2024, 109, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Fu, D.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D. Corrosion Resistance Prediction of High-Entropy Alloys: Framework and Knowledge Graph-Driven Method Integrating Composition, Processing and Crystal Structure. npj Mater. Deg. 2025, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H. Diffusion in Ultra Fine Grained CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy Processed by Equal Channel Angular Pressing. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 5805–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Singh, C.V. Defect Energetics in a High-Entropy Alloy Fcc CoCrFeMnNi. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 4231–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Qiu, S.; Jiao, Z.B. Atomic-Scale Understanding of Interstitial-Strengthened High Entropy Alloys. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 6002–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M.; Miao, J.; Mills, M.; Ghazisaeidi, M. Stacking Fault Energy in Concentrated Alloys. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, E.J.; Lobato, Á.; Izquierdo-Ruiz, F.; Márquez, A.M.; Recio, J.M.; Nath, P.; Plata, J.J.; Otero-de-la-Roza, A. Thermodynamics of Solids Including Anharmonicity Through Quasiparticle Theory. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Evitts, L.J.; Fragile, A.; Wilson, R. Predicting the Thermal Expansion of BCC High Entropy Alloys in the Mo-Nb-Ta-Ti-W System. J. Phys. Energy 2022, 4, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Miao, X.; Yan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Qian, F.; Xu, F.; Caron, L. Colossal Negative Thermal Expansion over a Wide Temperature Span in Dynamically Self-Assembled MnCo(Ge,Si)/Epoxy Composites. Mater. Res. Lett. 2024, 12, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Heinemann, H.; Erck, M.; Schacht, A. Thermal Expansion of High Entropy Alloys for Multilayer Heating Systems. Therm. Spray Bull. 2023, 16, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lin, K.; Xu, H.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.W.; Kato, K.; et al. High-Entropy Magnet Enabling Distinctive Thermal Expansions in Intermetallic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 30380–30387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhou, C.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Long, F.; Yao, Y.; Hao, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.; et al. A Strategy to Reduce Thermal Expansion and Achieve Higher Mechanical Properties in Iron Alloys. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G. Theoretical Insights into the Lattice Thermal Conductivity and Thermal Expansion of CoNiFe Medium-Entropy Alloys. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 3998–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasák, T.; Čížek, J.; Melikhova, O.; Lukáč, F.; Preisler, D.; Janeček, M.; Harcuba, P.; Zimina, M.; Srba, O. Thermal Stability of Microstructure of High-Entropy Alloys Based on Refractory Metals Hf, Nb, Ta, Ti, V, and Zr. Metals. 2022, 12, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, A.J.; Misra, K.P.; Misra, R.D.K. Grain Boundary Segregation in a High Entropy Alloy. Mater. Tech. 2023, 38, 2221959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaan-Nyiak, M.A.; Alam, I.; Jossou, E.; Hwang, S.; Kisslinger, K.; Gill, S.K.; Tiamiyu, A.A. Design and Development of Stable Nanocrystalline High-Entropy Alloy: Coupling Self-Stabilization and Solute Grain Boundary Segregation Effects. Small 2024, 20, 2309631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Qi, Y.; Ji, Y.; Feng, M. Grain Boundary Segregation-Induced Strengthening-Weakening Transition and its Ideal Maximum Strength in Nanopolycrystalline FeNiCrCoCu High-Entropy Alloys. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 238, 107828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Shivakumar, S.; Luo, J. Refractory High-Entropy Nanoalloys with Exceptional High-Temperature Stability and Enhanced Sinterability. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 8548–8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xiao, Q.; Hu, W.; Huang, B.; Yuan, D. Atomistic Simulation Study of Grain Boundary Segregation and Grain Boundary Migration in Ni-Cr Alloys. Metals 2024, 14, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Davids, W.J.; Breen, A.J.; Ringer, S.P. Quantifying Short-Range Order Using Atom Probe Tomography. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Entropy Alloy Market—By Alloy Type, Manufacturing Method, Property, Application, End-Use Industry—Global Forecast, 2025—2034; Global Market Insights: Selbyville, DE, USA, 2025.

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A Critical Review of High Entropy Alloys and Related Concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mao, M.M.; Wang, J.; Gludovatz, B.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, S.X.; George, E.P.; Yu, Q.; Ritchie, R.O. Nanoscale Origins of the Damage Tolerance of the High-Entropy Alloy CrMnFeCoNi. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Furuhara, T.; Park, E.S.; Tasan, C.C. Natural-Mixing Guided Design of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys with As-Cast Tensile Ductility. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Peng, X. Design of Lightweight Ti3Zr1.5NbVx Refractory High-Entropy Alloys with Superior Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2023, 27, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, G.; Singh, P.; Su, R. Design of Refractory Multi-Principal-Element Alloys for High-Temperature Applications. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, T.; Shirizly, A.; Aghion, E. Additive Manufacturing Technologies of High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs): Review and Prospects. Materials 2023, 16, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.C. Progress in High-Entropy Alloys. JOM 2014, 66, 1964–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Arévalo, V.M.; Martin, P.; Sepúlveda, M.F.; Azocar, M.I.; Zhou, X.; Galleguillos Madrid, F.M.; Ramirez, C.G.; Zagal, J.H.; Páez, M. Recent Advances in High-Entropy Alloys for Electrocatalysis: From Rational Design to Functional Performance. Mater. Des. 2025, 258, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolar, S.; Ito, Y.; Dujita, T. Future Prospects of High-Entropy Alloys as Next-Generation Industrial Electrode Materials. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 8664–8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhan, S.; Xiao, F.; Wang, C.; Ma, D.; Yue, Q.; Wu, J.; Kang, Y. High-Entropy Alloy Nanosheets for Fine-Tuning Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 11955–11959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, R.; Tao, L.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Zeng, L.; Luo, M.; Guo, S. High-Entropy Alloy Electrocatalysts Go to (Sub-)Manoscale. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, H.; Qi, P.; Xie, G.; Liu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, P. Advanced High-Entropy Alloy Catalysts for Robust and Efficient Natural Seawater Splitting. Int. J. Hyd. En. 2025, 154, 150215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Liang, K.; Zhou, P.; He, P.; Zhang, S. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Fabrication Methods of High-Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2024, 178, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Kumkale, V.Y.; Hou, H.; Kadam, V.S.; Jagtap, C.V.; Lokhande, P.E.; Pathan, H.M.; Pereira, A.; Lei, H.; Liu, T.X. A Review of High-Entropy Materials with their Unique Applications. Adv. Comp. Hyb. Mater. 2025, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonia, A.; Kishor, M.; Ayyagari, K. Designing of High Entropy Alloys with High Hardness: A Metaheuristic Approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; An, X.; Sun, W. Design Methods of High-Entropy Alloys: Current Status and Prospects. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1029, 180638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Nairan, A.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, R.; Bai, Y.; Khan, U.; Gao, J. Unlocking the Potential of High Entropy Alloys in Electrochemical Water Splitting: A Review. Small 2024, 20, 2311929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Klingenhof, M.; Gao, C.; Koketsu, T.; Weiser, G.; Pi, Y.; Liu, S.; Sui, L.; Hou, J.; Li, J.; et al. Facilitating Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction on the Hetero-Interfaced Ru/RuO2 Through Pt Single Atoms Doping. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senkov, O.N.; Wilks, G.B.; Miracle, D.B.; Chuang, C.P.; Liaw, P.K. Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangues, J.; Melia, M.; Puckett, R.; Whetten, S.R. Exploring Additive Manufacturing as a High-Throughput Screening Tool for Multiphase High Entropy Alloys. Ad. Manuf. 2020, 37, 101598. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, K.; Vecchio, K.S. Searching for High Entropy Alloys: A Machine Learning Approach. Acta Mater. 2020, 198, 178–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Wilks, G.B.; Scott, J.M.; Miracle, D.B. Mechanical Properties of Nb25Mo25Ta25W25 and V20Nb20Mo20Ta20W20 Refractory High Entropy Alloys. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, C.; Bradshaw, A.M.; Thorenz, A.; Tuma, A. Supply Risk Considerations for the Elements in Nickel-Based Superalloys. Resources 2020, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, D. The Materials Science Behind Sustainable Metals and Alloys. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, J.M.; Meza, A.; Venkatesh Kumaran, S.; Mostafaei, A.; Mohammadzadeh, A. From High-Entropy Alloys to Alloys with High Entropy: A New Paradigm in Materials Science and Engineering for Advancing Sustainable Metallurgy. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2025, 36, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Gao, P.; Xiang, Q.; Qu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Ren, Υ.; Yu, B.; Qiu, K. AlxCrFeNi Medium Entropy Alloys With High Damping Capacity. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 876, 159991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, H.; Abedi, H.R.; Zhang, Y. A Review Study on Thermal Stability of High Entropy Alloys: Normal/abnormal Resistance of Grain Growth. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]