1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb), continues to be a global health burden and remains the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent after COVID-19. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2023), an estimated 1.25 million deaths were attributed to TB in 2024 alone [

1]. The disease is airborne and affects individuals of all ages and populations, while it is most prevalent among those with weakened immune systems, malnutrition or tobacco dependence. It is estimated that nearly one-quarter of the global population carries latent M. tb infection, and approximately 5-10% of these individuals will develop active TB during their lifetime [

1].

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) present a threat to global TB control efforts. MDR-TB refers to strains resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, the most effective first-line drugs. In contrast, XDR-TB represents MDR-TB with additional resistance to fluoroquinolones and at least one second-line injectable drug. In 2023, nearly 10% of reported cases in the United States were of MDR-TB [

2]. This alarming trend underscores the urgent need for discovering novel anti-TB therapeutics with a new mechanism of action to overcome resistance.

Natural products have long served as invaluable sources of medicines, and the search for new bioactive scaffolds increasingly focuses on microorganisms from extreme or underexplored environments. The deep-sea biosphere, particularly regions exceeding 200-6,000 meters in depth, represents one of the most chemically diverse and underexplored habitats on Earth [

3]. Microorganisms and invertebrates living in such extreme conditions, characterised by high pressure, low temperature and limited oxygen and light, have evolved unique metabolic adaptations, giving rise to structurally distinct metabolites with exceptional pharmacological potential [

4].

Several studies have reported marine-derived natural products and their derivatives as promising anti-mycobacterial leads. For example, manzamine alkaloids, 6-hydroxymanzamine E and 8-hydroxymanzamine A, isolated from the marine sponge

Acanthostrongylophora sp., showed potent anti-TB activity [

5,

6,

7]. Similarly, the amino lipopeptide trichoderin A from marine-sponge-derived

Trichoderma sp. exhibited strong mycobacterial activity under hypoxic conditions, where isoniazid loses efficacy [

8]. Guanidine alkaloids such as batzelladine L and N have also demonstrated inhibitory effects against

M. tuberculosis H37Rv fused [

9,

10] (

Figure 1). These examples underscore the enormous potential of marine scaffolds in anti-tubercular drug discovery.

Despite this chemical diversity, the experimental exploration of marine natural products is limited by several practical challenges. Traditional bioassay-guided isolation requires substantial biomass, which is often expensive, yields low quantities of metabolites, and often results in the isolation of known metabolites. Also, many deep-sea or symbiotic microorganisms are uncultivable under standard laboratory conditions, and their biosynthetic potential remains largely inaccessible. Integrating metabolomics, genome mining, and computational chemistry can overcome these limitations by identifying and prioritising bioactive scaffolds prior to isolation or synthesis.

To bridge this translational gap, Computational-aided Drug Discovery (CADD) approaches have become indispensable tools for rapid prioritisation of promising leads. Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS), molecular docking, and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) analysis enable the speedy evaluation of large chemical libraries. These methods predict binding affinities, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties, narrowing thousands of candidates to the few promising ones for in vitro experimental validation. When paired with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, these methods give valuable insights into ligand-target stability and binding mechanisms in physiologically relevant environments.

Such in-silico pharmacokinetic strategies have been successfully applied in antiviral and antifungal research. For example, screening 2,033 marine natural products against SARS-CoV-2 replication enzymes (3CLpro, PLpro, and RdRp) identified two potent hit compounds with superior stability and pharmacokinetic properties compared to standard inhibitors [

11]. Similarly, mining over 1,400 marine natural products identified anti-EBV (Epstein-Barr Virus) candidates via docking and MD simulations. Recent applications in the anti-TB field include virtual screening of the CMNPD library, which yielded selective inhibitors of InhA, a key enzyme in mycolic acid biosynthesis [

12]. Furthermore, analyses of 139 marine fungal metabolites have shown that the majority (131) exhibit measurable anti-mycobacterial activity, highlighting the value of computational screening in guiding future TB drug discovery efforts [

13]. Although these studies have not been validated in vitro, they provide a prominent base for rational hit prioritisation and further biological testing.

Computational pipelines are now integral to early-stage drug discovery; however, limitations persist regarding their predictive accuracy for complex natural products. Scoring functions in molecular dynamics often oversimplify protein flexibility or solvent effects, leading to a disparity between theoretical and experimental affinities, especially in large molecules. Likewise, pharmacokinetic models are typically trained on smaller synthetic drug-like compounds, potentially limiting their precision when extrapolated to natural product scaffolds [

14,

15]. Nonetheless, the convergence of a multi-tier computational framework, combining molecular docking, ADMET profiling, MD simulations, and, more recently, AI-assisted scoring and binding free energy refinement, has greatly improved the reliability and cross-validation of virtual hits [

16].

Building on these methodological advances, the present study employed an integrated computational strategy to discover novel anti-tubercular candidates from marine-derived compounds collected from depths exceeding 200 m. A curated library of 2,773 deep-sea compounds sourced from the MarinLit, Reaxys, and CMNPD databases was systematically screened against a single validated M. tb target-Rv1155, a F

420-binding oxidoreductase essential for the bacterium’s redox metabolism [

17]. Initial high-throughput molecular docking for preliminary binding assessment was followed by ADMET-based profiling to prioritise compounds with favourable drug-like properties, and by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to evaluate the conformational stability and persistence of protein–ligand interactions under dynamic conditions.

This systematic multi-tier approach highlights the deep-sea marine environment as an underexplored yet promising reservoir of structurally diverse scaffolds with potential anti-tubercular activity. Beyond identifying promising candidates, the study establishes a cost-effective and generalised computational workflow for exploring marine metabolites diversity in the discovery of new inhibitors targeting the F420-dependent redox system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, thereby contributing to the global effort to combat drug-resistant tuberculosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Compounds

A total of 2,773 deep-sea-derived natural compounds, isolated from depths exceeding 200 meters, were screened against

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb). The compound library [

17]

(in press) was curated from three comprehensive databases: MarinLit [

18], Reaxys [

19], and the Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD) [

20]. These sources collectively comprise structurally diverse marine metabolites with reported or predicted biological activity, providing a representative library for virtual screening.

2.2. Molecular Docking

All 2,773 compounds were prepared as ligands and optimised into .mol2 format using AutoDock Vina v1.2.0 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) [

21,

22] through Samson Connect (OneAngstrom, 2022) (

https://www.samson-connect.net/). Ligand geometry optimisation ensured that each molecule adopted a low-energy conformation suitable for reliable target interaction. The three-dimensional structure of

M. tuberculosis Rv1155 enzyme in complex with its cofactor F

420 (PDB ID: 4QVB) was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (

https://www.rcsb.org/). Protein preparation involved removing water molecules and retaining a single cofactor conformation (F

4202) for reference in grid generation. The receptor’s potential binding pocket was identified using LigandScout 4.4.8 [

23]. The LigandScout pocket-finder algorithm detects a potential binding pocket by generating a three-dimensional grid over the protein surface and assigning a buriedness score to each grid point. Clusters of highly buried grid points are connected and enclosed by an isosurface, representing the spatial volume of a potential ligand-binding site. For Rv1155 (PDB ID: 4QVB), the grid box centre and dimensions were set to 10.8 × 20.1 × 18.6 Å and 31.4 × 21.8 × 24.4 Å, respectively.

Docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina v1.2.0. The binding mode number was set to 9, generating nine distinct poses for each ligand to increase the likelihood of capturing a biologically relevant orientation. The maximum energy difference between the best and other poses was limited to 3 kcal/mol. The exhaustiveness parameter was set to 4, and convergence was validated by repeating docking runs at exhaustiveness levels of 8 and 16, with identical parameters. The co-crystallised cofactor F4202 served as a positive control to validate docking accuracy by reproducing its experimental binding pose. Compounds obtained from the CMNPD dataset were screened separately from those obtained from the combined MarinLit-Reaxys dataset. The top-scoring ligands were then pooled and prioritised for further evaluation.

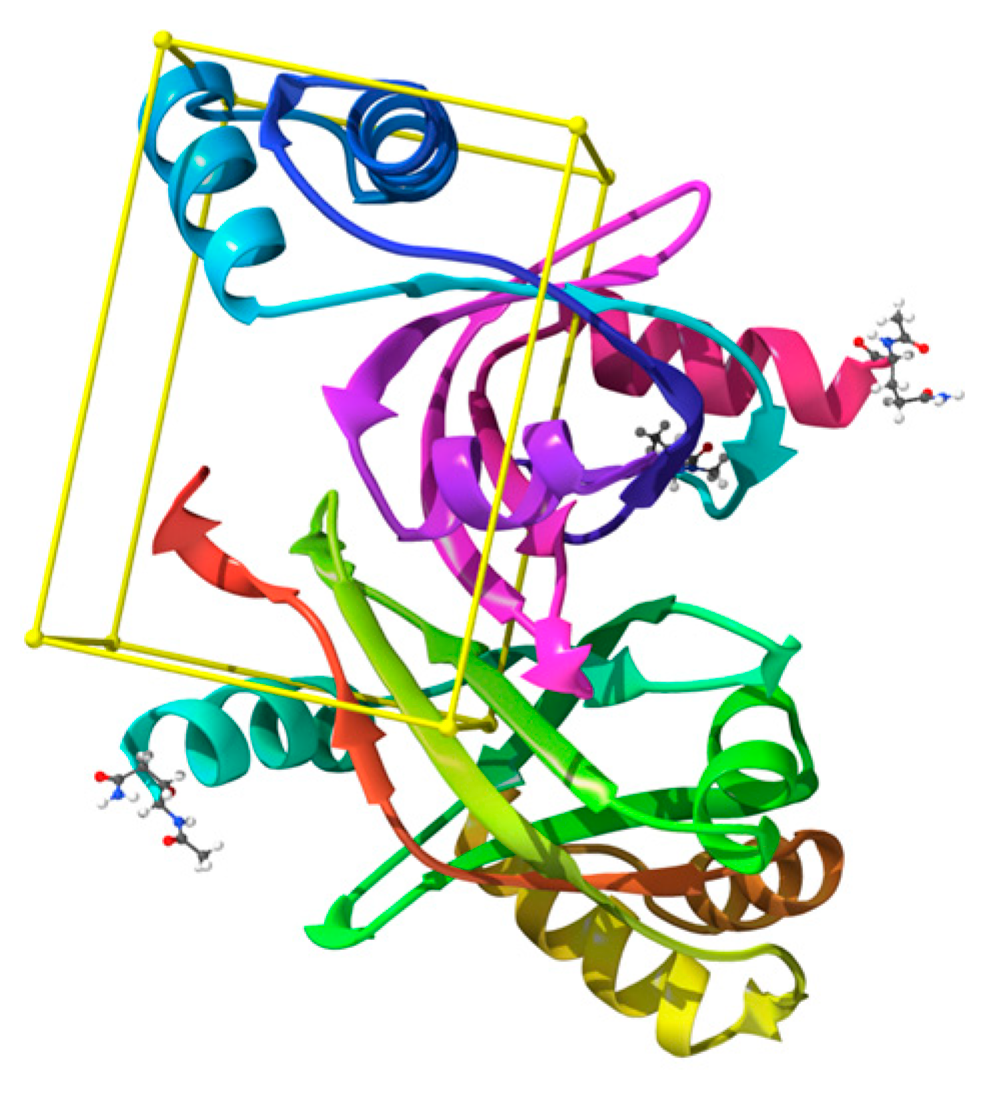

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein Rv1155 in complex with co-enzyme F420 (PDB ID: 4QVB), the yellow box shows the binding site (colour figure online).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein Rv1155 in complex with co-enzyme F420 (PDB ID: 4QVB), the yellow box shows the binding site (colour figure online).

2.3. ADMET Evaluation

Pharmacokinetic profiling of the top 29 docked deep-sea compounds was performed using ADMETlab 3.0 [

24] web server. The SMILES notations of selected compounds were submitted to the platform to predict their absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties. Drug-likeness assessment was based on three primary parameters: Lipinski’s rule of five (for oral bioavailability), Pfizer’s rule (for toxicity filtering), and Predicted Blood–Brain Barrier permeability (PBB) (for CNS penetration potential). The evaluation ensured that the selected compounds not only exhibited strong binding affinity but were also pharmacologically acceptable and had biologically viable profiles for further optimisation.

2.4. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using Flare v9.0 (Cresset, UK) integrated with the OpenMM 7.7 package [

25]. Simulations were conducted for 200 ns employing the Open Force Field with explicit TIP3P water molecules to replicate near-physiological conditions. Each protein-ligand complex was solvated in a truncated octahedral box with a 10 Å buffer distance from the protein surface.

Partial atomic charges for ligands were assigned using the AM1-BCC method, and energy minimisation was performed until an energy tolerance of 0.25 kcal/mol was reached to remove steric clashes. Equilibration was carried out for 200 ps, followed by production runs in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble at 298 K and 1 bar, using a four-fs integration time step. Trajectory analyses included Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to assess complex stability, Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) to assess residue flexibility, and hydrogen bond occupancy to quantify persistent intermolecular interactions within the Rv1155 active site. Each simulation was repeated independently under identical conditions to confirm the reproducibility and consistency of the results.

2.5. MM-GBSA Calculations

The Molecular Mechanics-Generalised Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) was used to estimate the binding free energy (∆

Gbind) of top-ranked protein-ligand complexes following molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. All calculations were performed in Flare v9.0 (Cresset, UK) using OpenMM engine with Open Force Field (v2.2.0) [

26]. The AM1-BCC method was used to calculate partial atomic charges for ligands, and the implicit solvation model GBn2 was used to account for solvent polarisation effects. Calculations were performed under normal calculation mode, and both protein and ligand were energy minimised before scoring.

The standard MM-GBSA formula calculated the binding free energy for each complex:

Where G includes molecular mechanistic energy, polar solvation energy and non-polar solvation energy.

The non-polar contribution (

) was calculated from SASA (Solvent Accessible Surface Area) using a linear relationship [

27]

where β and γ are empirical constants set to 0.86 kcal/mol and 0.005 kcal/mol/Å

2, respectively. MM-GBSA and SASA were calculated to assess the stability and thermodynamic favorability of binding within the Rv1155 active site. The calculations were performed on the lowest energy pose obtained from docking.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Molecular Docking Analysis

Molecular docking serves as a critical initial filter in structure-based drug discovery, providing rapid insight into potential protein-ligand interaction patterns and relative binding affinities. The process involves systematic sampling of ligand conformations within the protein’s active site to identify the most energetically favourable pose, which is then ranked by a scoring function that estimates binding free energy [

28].

In this study,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb) enzyme Rv1155 (PDB ID: 4QVB) was selected as the sole molecular target for virtual screening owing to its confirmed role as a pyridoxine-5′-phosphate oxidase-like (PNPOx) enzyme and novel coenzyme F

420-binding protein [

29,

30]. Rv1155 belongs to the F

420-dependent oxidoreductase family and utilises cofactor F

420 (denoted as F

4201 and F

4202 in the crystal structure) as an essential redox mediator, a system unique to actinobacteria and some archaea. The enzyme is involved in multiple M. tb metabolic pathways, including redox homeostasis, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress resistance, and activation of nitroimidazole prodrugs such as pretomanid and delamanid the [

29,

31,

32]. Because F

420-dependent enzymes are absent in humans, this cofactor system offers a highly selective therapeutic target for anti-tubercular drug design.

The crystal structure of Rv1155 complexed with co-enzyme F

420 (PDB: 4QVB, 1.8 Å resolution) reveals a Rossmann-like fold with a well-defined, hydrophobic binding cleft that accommodates the deazaflavin cofactor. The F

420 binding pocket is located at the dimer interface formed by residues from both monomers. Key residues shaping this site include Arg30, His27, Asn60, Arg55, Lys57, Trp77, Tyr79 [

29]. These residues define a rational pocket for ligand docking; therefore, targeting this cofactor-interacting region could disrupt essential redox reactions, ultimately compromising bacterial viability.

Initially, two cofactors, F

4201 and F

4202, were evaluated as docking standards; however, only F

4202 achieved precise pocket alignment and RMSD validation and was therefore used as the reference ligand for further analysis. In our study, a total of 2,773 deep-sea-derived compounds from the CMNPD, Reaxys, and MarinLit databases were docked against Rv1155, using the native cofactor (F

4202) as a positional reference for grid definition with AutoDock Vina (v1.2.0). Although AutoDock Vina treats the receptor as rigid while allowing complete ligand flexibility, it neglects subtle conformational adjustments described by the induced-fit model. Yet, it remains highly effective as an initial screening tool for rapid identification of top hit candidates with favourable binding geometries [

33,

34]. For each compound, the lowest-energy conformation among nine binding poses was selected to represent the predictive complex.

Docking scores revealed binding affinities ranging from –0.59 to –15.9 kcal/mol, with several marine metabolites exhibiting comparable or superior scores to the native cofactor F

4202. Of the 2,773 screened compounds, ligands from the CMNPD database and the combined MarinLit-Reaxys databases were analysed independently to ensure balanced representation from both curated sources. In total, 29 ligands displayed strong binding energies between –10.98 and –15.95 kcal/mol, exceeding the docking score of native cofactor F

4202 (

Table S1). These top-scoring compounds were subsequently advanced to ADMET profiling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to validate their pharmacokinetic profiles and dynamic stability further.

Visualisation of docking interactions revealed that several compounds occupied the same binding site as native cofactor F

4202 in the Rv1155 protein. The residues MetA24, Tyr120, TyrA107, ValA36 and IleA51 formed a conserved hydrophobic pocket, interacting with several compounds through strong van der Waals forces. This mimics the hydrophobic anchoring observed in standard F

4202. Notably, the residue SerA50 acts as a critical anchor, forming hydrogen bonds with multiple top-docked compounds, as seen in standard F

4202. While the standard F

4202 exhibits extensive electrostatic interactions with residues LysA57, ArgA129, and ArgA55 via its phosphate tail, the library compounds compensate for this lack of charge by maximising hydrophobic interactions. Compound_1749 exhibited the most extensive hydrogen-bonding network involving both acidic and basic residues, which correlated with its high docking affinity and favourable binding orientation within the active site. Representative 2D interaction diagrams for the standard cofactor and selected top-docked ligands are shown in

Figure 3.

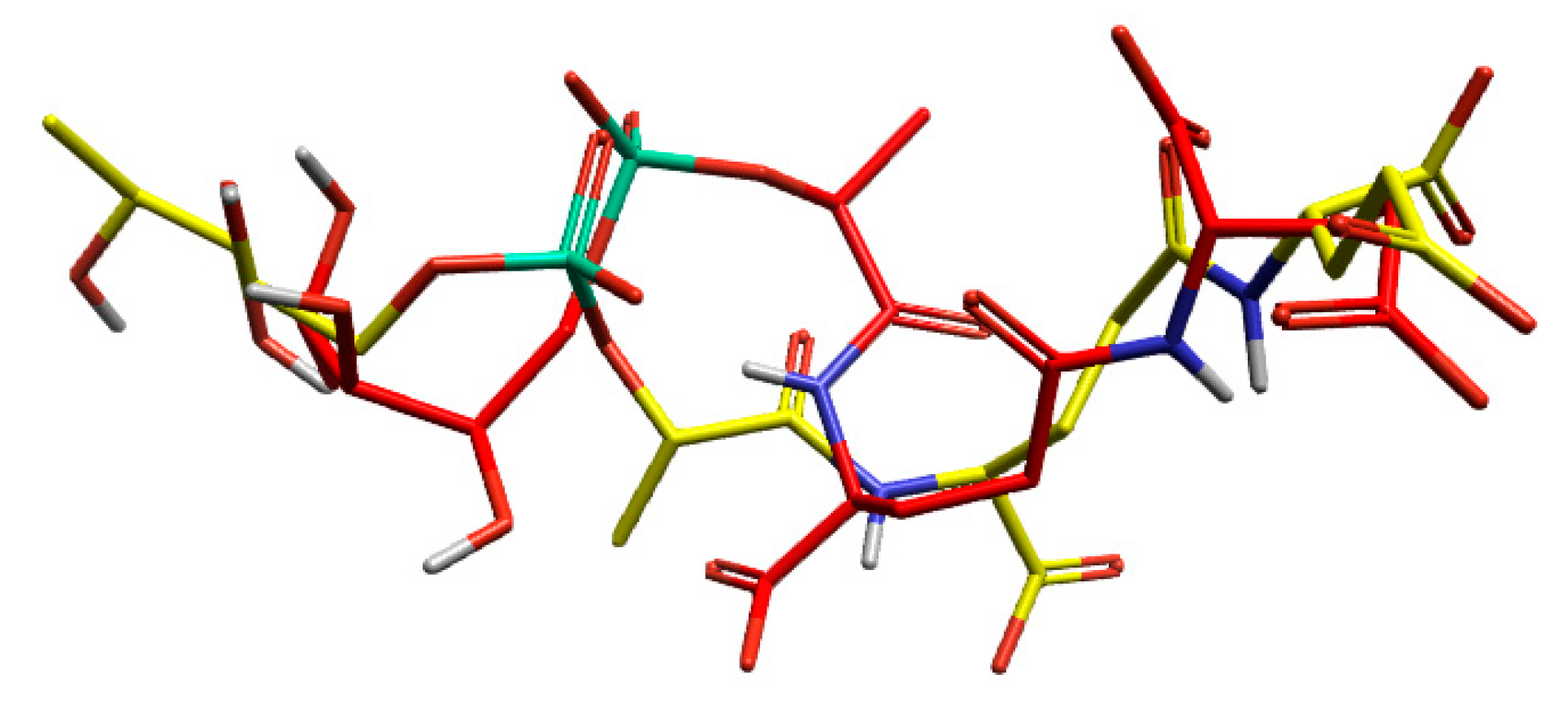

3.1.1. Validation of Docking Methodology

The docking method was validated by docking the co-crystallised ligand into the protein’s active site and superimposing the docked conformer with the co-crystallised conformer. The low RMSD of 2.77 Å between the experimental and co-crystallised ligand indicated the same orientation, validating the docking method.

Figure 4.

The comparison between the experimental and reference poses of the co-crystallised ligands validates the docking method showing docked ligand pose in yellow and ligand pose extracted from crystal structure in red.

Figure 4.

The comparison between the experimental and reference poses of the co-crystallised ligands validates the docking method showing docked ligand pose in yellow and ligand pose extracted from crystal structure in red.

3.2. ADMET Evaluation

A total of 29 compounds with the highest docking affinities were prioritised for ADMET evaluation to ensure that the computationally identified hits are also chemically and biologically viable for further optimisation and experimental validation.

ADMET predictions were performed based on Lipinski’s rule of five, the Pfizer rule, and the Predicted Blood–Brain Barrier permeability (PBB) parameter. Lipinski’s rule was applied to assess oral bioavailability, while the Pfizer rule served as an early toxicity filter. The PBB parameter was specifically incorporated owing to its pharmacological relevance in tuberculosis, where effective CNS penetration must be balanced with the risk of neurotoxicity.

Although pulmonary infection is the primary manifestation of TB,

M. tuberculosis can disseminate to extrapulmonary sites, including the central nervous system (CNS), causing tuberculous meningitis (TBM). This form remains one of the most challenging to treat due to the limited blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability of most frontline drugs, such as ethambutol and streptomycin, which results in subtherapeutic CNS concentrations and poor clinical outcomes [

35,

36]. Therefore, incorporating the PBB filter into ADMET analysis enables early identification of compounds with an optimal physicochemical balance, capable of sufficient intracellular penetration without excessive BBB permeation, thereby minimising CNS-related adverse effects.

Of the 29 compounds evaluated, most satisfied both Lipinski and Pfizer rules, indicating favourable oral bioavailability and safety profiles (

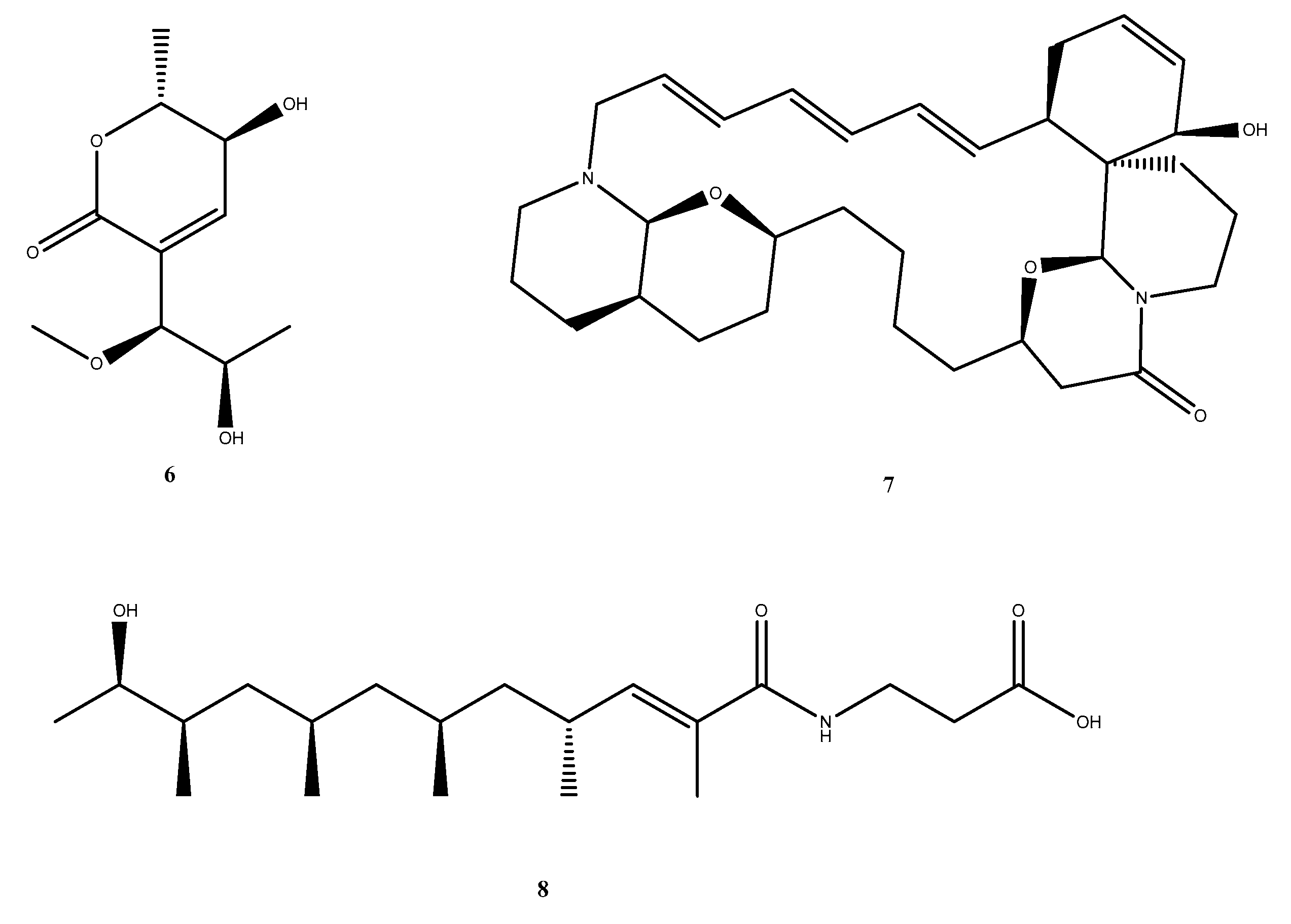

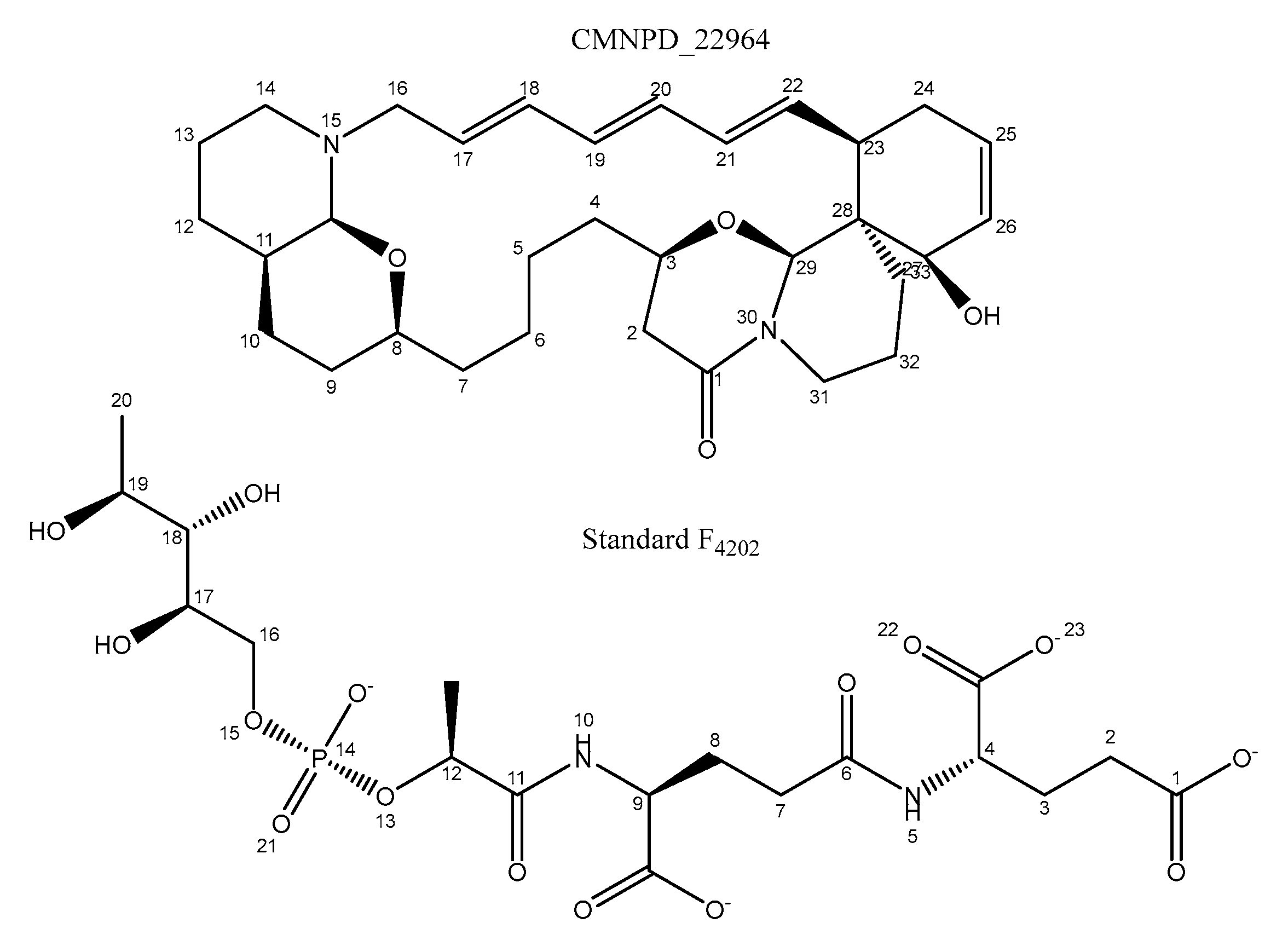

Table S2). The remaining seven violated the Pfizer rule and were excluded from further analysis. Among the 22 compounds with acceptable drug-likeness, three ligands were further prioritised based on their PBB values: Upenamide (CMNPD_22964; PubChem CID: 10792140) from the CMNPD dataset, Aspyronol (Compound_1749; PubChem CID: 139585929), and Fiscpropionate F (Compound_1796; PubChem CID: 155524686) from the combined MarinLit-Reaxys dataset.

Among these, Aspyronol displayed a PBB value (~21) remarkably close to that of the native cofactor F4202 (~29). Structural comparison revealed that Aspyronol possesses a highly oxygenated, polyhydroxylated scaffold with ether linkages and chiral centres at secondary alcohol positions. These polar functional groups mimic the hydrogen-bonding pattern and polarity distribution of F4202, causing similarly low membrane permeability. Both molecules exhibit low lipophilicity and extensive hydrogen bond donor/acceptor networks, which restrict passive BBB diffusion while maintaining strong cytosolic retention. This structural and physicochemical balance suggests that Aspyronol may mimic the intracellular distribution profile of F4202, enabling effective targeting of Rv1155 while limiting neurotoxicity.

It is noteworthy that the native cofactor F4202 does not comply with Lipinski’s rule of five, primarily due to its high molecular weight, multiple phosphate and hydroxyl groups, and large polar surface area. However, this deviation does not diminish its biological importance, as F4202 is an endogenously synthesised cofactor that functions through specific binding rather than passive diffusion across membranes. While Lipinski’s criteria are essential for small-molecule drug discovery, the physicochemical characteristics of F4202 define the chemical environment and polarity preferences of the Rv1155 binding site.

Overall, the ADMET evaluation demonstrates that Upenamide, Aspyronol, and Fiscpropionate F displayed a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and balanced permeability, supporting their progression to molecular dynamics simulations for further validation of stability and binding persistence.

Figure 5.

Structure of three lead compounds selected for molecular dynamics simulation 6. Aspyronol/Compound_1749 (PubChem CID: 139585929), 7. Upenamide/ CMNPD _22964 (PubChem CID: 10792140), 8. Fiscpropionate F/ Compound_1796 (PubChem CID: 155524686).

Figure 5.

Structure of three lead compounds selected for molecular dynamics simulation 6. Aspyronol/Compound_1749 (PubChem CID: 139585929), 7. Upenamide/ CMNPD _22964 (PubChem CID: 10792140), 8. Fiscpropionate F/ Compound_1796 (PubChem CID: 155524686).

3.3. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

We performed 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations on the apoprotein (PDB ID: 4QVB) and its complexes with Compound_1749, Compound_1796, CMNPD_22964, and Standard F4202 using Flare v9.0. The stability of each system was assessed through Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of gyration (Rg), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). RMSD is a measure of the system’s movement and overall stability, while RMSF is used to measure molecular flexibility. The radius of gyration is used to assess the system’s compactness and to track changes in the shape of the molecule. At the same time, PCA identifies the key motions and conformational changes in the simulation.

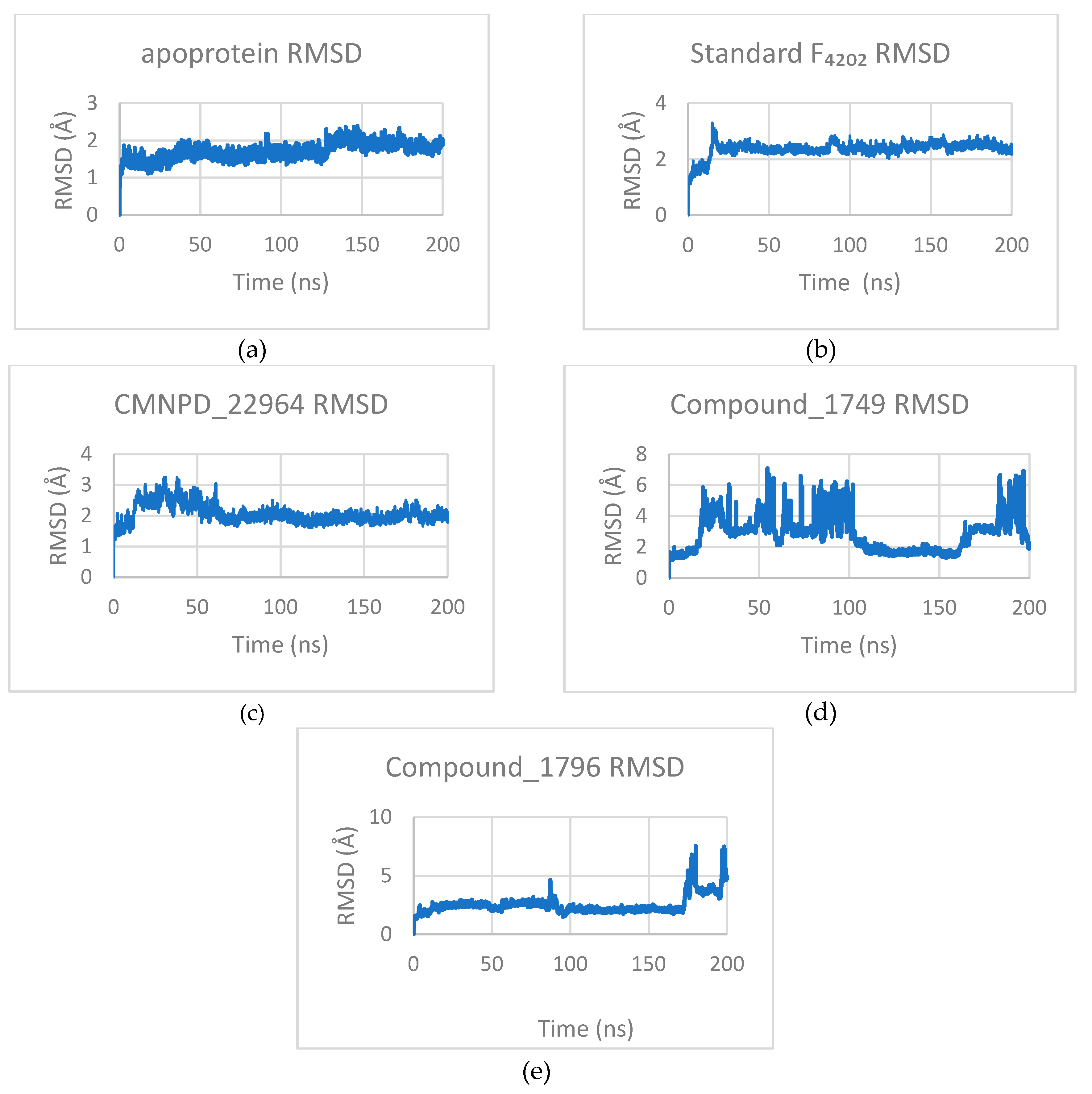

3.3.1. Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

The apoprotein demonstrated a stable conformation, with a low mean RMSD of 1.70 ± 0.21 Å. Complexes with F4202 and CMNPD_22964 also exhibited stable trajectories, with RMSD values of 2.36± 0.25 Å and 2.06 ± 0.30 Å, respectively. In contrast, Compound_1749 complex (RMSD 2.90 ± 1.20 Å) displayed significant transient deviations between 20-100 ns and 180-200 ns, suggesting a potential conformational shift. Similarly, the Compound_1796 complex (RMSD 2.54 ± 0.81 Å) was largely stable but showed a substantial deviation near the simulation’s end, indicating late-onset structural instability or flexibility. In addition, the Compound_1796 complex shows a brief deviation between 85 and 95 ns, suggesting a transitory conformation explored during that time.

Figure 6.

RMSD profiles of (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796 during simulation. It should be noted that the Compound_1749 complex shows significant deviation throughout the simulation.

Figure 6.

RMSD profiles of (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796 during simulation. It should be noted that the Compound_1749 complex shows significant deviation throughout the simulation.

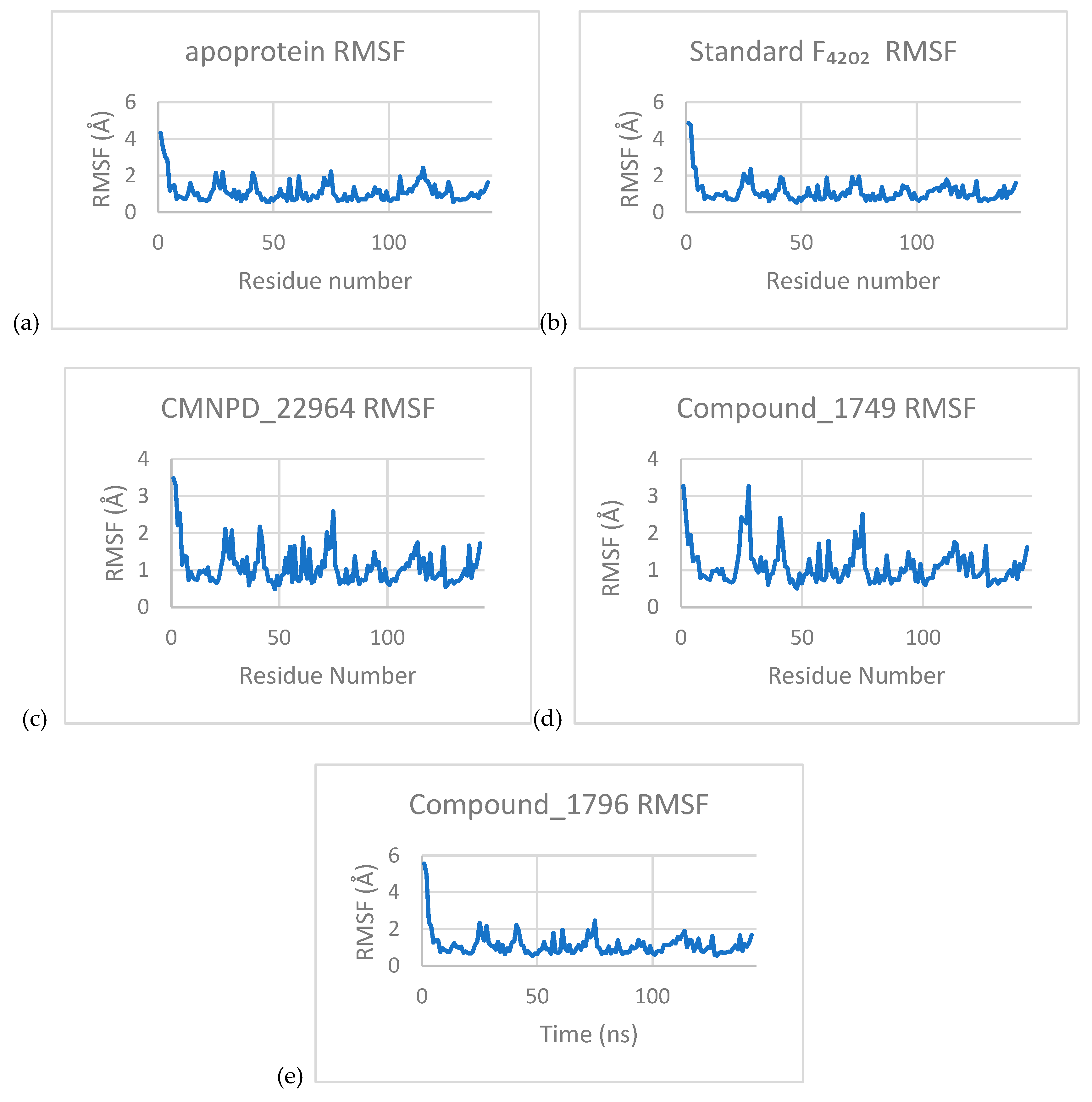

3.3.2. Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

The RMSF was comparable across all systems, with the apoprotein and its complexes with F4202, CMNPD_22964, Compound_1749, Compound_1796 exhibiting values of 1.11 ± 0.57 Å, 1.10 ± 0.59 Å, 1.09 ± 0.49 Å, 1.11 ± 0.50 Å, and 1.13 ± 0.64 Å, respectively. In each simulation, residues 1 and 2 displayed elevated flexibility, suggesting their contribution to the overall protein dynamics.

Figure 7.

The RMSF profiles (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796 of each of the trajectories. Each profile shows that Residues 1 and 2 have significantly higher values than the others.

Figure 7.

The RMSF profiles (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796 of each of the trajectories. Each profile shows that Residues 1 and 2 have significantly higher values than the others.

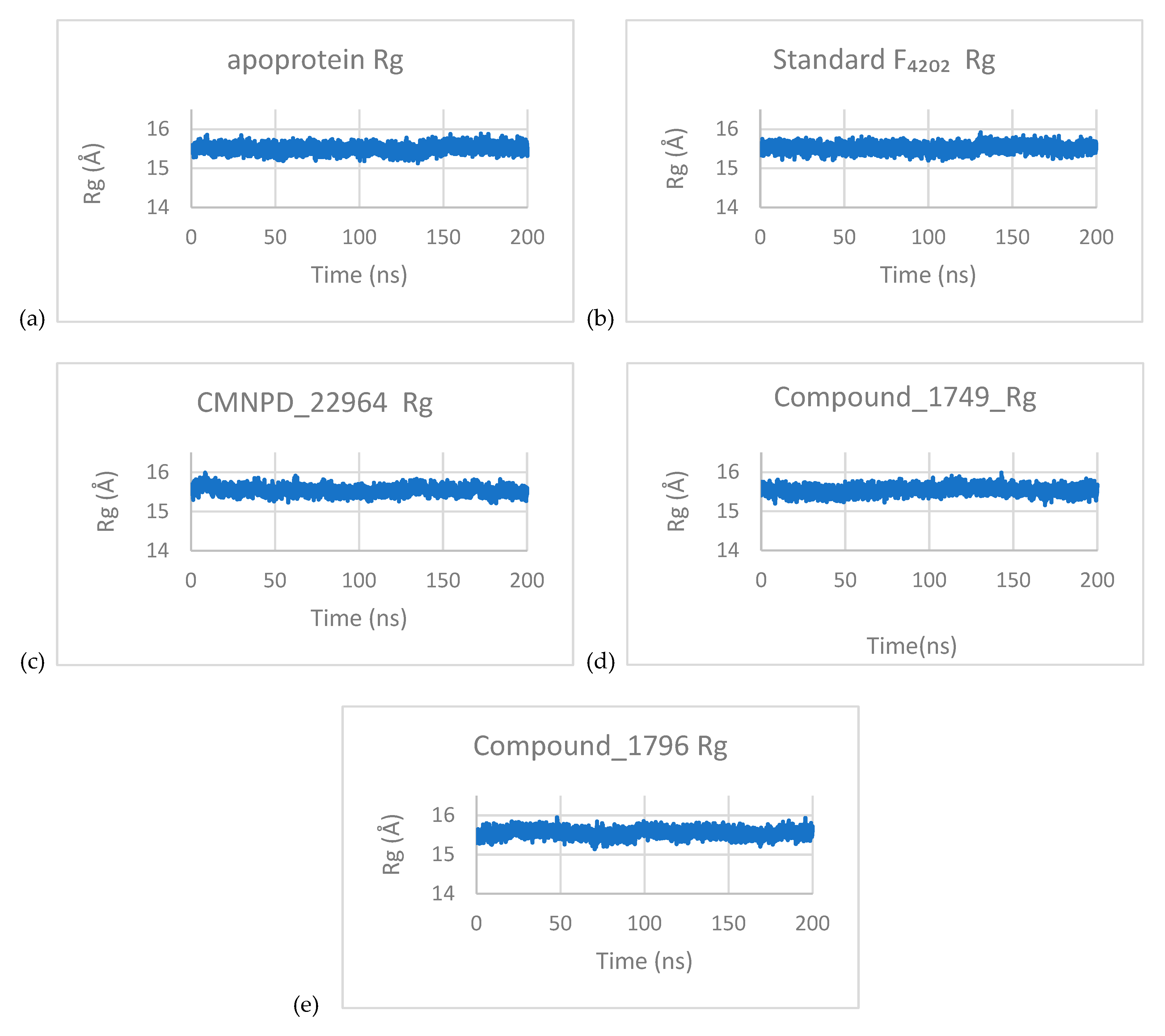

The radius of gyration (Rg) remained stable for all systems, with the apoprotein and its complexes with Standard F4202, CMNPD_22964, Compound_1749, and Compound_1796 exhibiting values of 15.50 ± 0.10 Å, 15.52 ± 0.10 Å, 15.54 ± 0.10 Å, 15.50 ± 0.10 Å, and 15.55 ± 0.10 Å, respectively. These consistent values indicate that all systems maintained a compact conformation throughout the simulation.

Figure 8.

The Radius of gyration (Rg) profiles for each of the trajectories (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796. They are observed to maintain a steady value over time in simulations.

Figure 8.

The Radius of gyration (Rg) profiles for each of the trajectories (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796. They are observed to maintain a steady value over time in simulations.

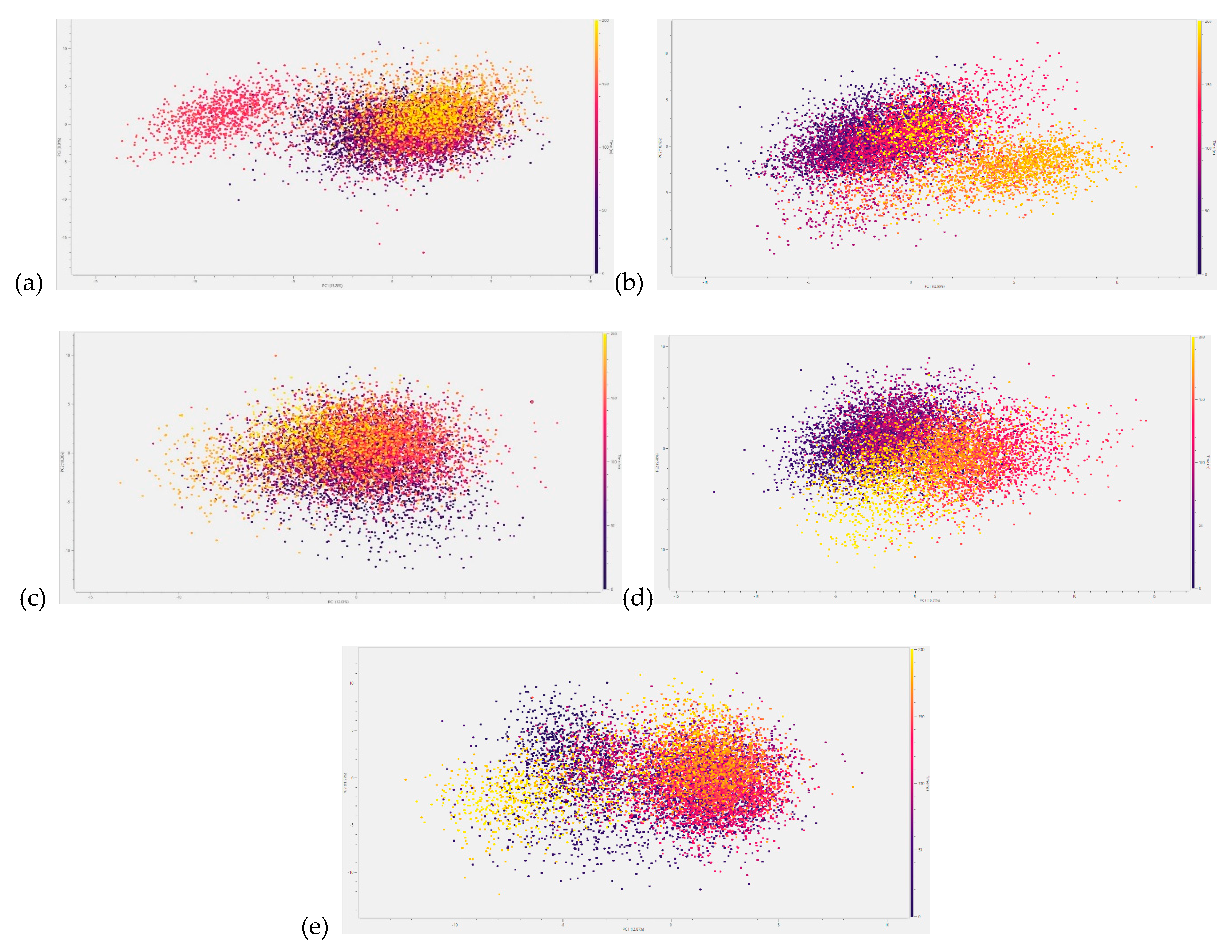

3.3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the trajectories revealed the systems’ large-scale motions. The apoprotein, along with its CMNPD_22964 and F4202 complexes, exhibited predominantly restricted conformational sampling, as indicated by their RMSD and RMSF profiles. A transient deviation in the apoprotein was observed between 130 and 150 ns. Another deviation is observed in its complex with F4202 between 170 and 190 ns, but it is less pronounced than in the apoprotein simulation. The CMNPD_22964 complex is observed to be strictly restricted to a smaller conformational space and fewer deviations. In contrast, the Compound_1749 complex, though similarly restricted, displayed motion consistent with oscillation between two distinct conformers.

Consistent with its RMSD graph, the Compound_1796 complex initially explored a confined subspace diverging into a distinct conformational state towards the end. Furthermore, the transitory conformational space explored by the system between 85-95 ns is confirmed through the interspersed points in the space between the two major conformations explored. These deviations, while brief, suggest potential instability in the system.

Figure 9.

PCA analyses of (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796. Unlike its RMSD profile, the Compound_1749 complex shows slight variation, suggesting that the protein oscillates between two stable conformations.

Figure 9.

PCA analyses of (a) apoprotein; (b) standard F4202; (c) CMNPD_22964; (d) Compound_1749, and (e) Compound_1796. Unlike its RMSD profile, the Compound_1749 complex shows slight variation, suggesting that the protein oscillates between two stable conformations.

3.4. Hydrogen Bond Contacts

The hydrogen bond contacts were also calculated for the four complexes, with only the CMNPD_22964 and the Standard F

4202 complexes showing significant (>50% of the frames) contacts with residues in the protein. In the CMNPD_22964, the ketonic oxygen at position 1 (please refer to

Figure 10 for the structure and numbering) showed significant contact with two protons. One of the contacts observed was with the hydroxyl proton on the aromatic ring of the TyrA120 residue for 65.6% of the frames, and the other was with the hydroxyl proton on the backbone of the SerA50 residue for 67% of the frames.

Oxygen at position 21 of the Standard F

4202 showed a hydrogen bond contact with the terminal amide carbon of the AsnA35 residue for 50.0% of the frames. In addition, the oxygens at positions 22 and 23 showed contacts with protons in the ArgA129 residue, as summarised in

Table 1.

3.5. MM-GBSA Calculations

MM-GBSA calculations were conducted to estimate the binding free energy of the top docked Rv1155 ligand complexes. The results summarised in

Table 2 revealed that all three candidates exhibited markedly stronger binding affinities than the native cofactor F

4202. Fiscpropionate F (Compound_1796) showed the most favourable

ΔG (-34.07 kcal/mol), followed by Upenamide and Aspyronol. The non-polar solvation energies (ranging from -30.45 to -40.06 kcal/mol/Å

2) and corresponding SASA values (6,262–8,184 Å

2) indicated extensive hydrophobic interactions stabilising the complexes.

Interestingly, all three lead compounds identified in this study are naturally occurring marine metabolites with previously reported antimicrobial activity. Upenamide (CMNPD_22964) was first isolated from the sponge Echinochalina sp., known for its antibacterial and cytotoxic potential [

37]. Aspyronol (Compound_1749), a polyketide isolated from deep-sea

Aspergillus sp., has shown cytotoxic, antibacterial, and antifungal activity [

38]. Fiscpropionate F (Compound_1796), along with its analogue series, was reported from deep-sea

Aspergillus fischeri FS452 and exhibited strong anti-mycobacterial activity. A series of these analogues demonstrated inhibition of M. tb protein tyrosine phosphatase B (MptpB), suggesting a reliable anti-tubercular activity [

39]. In our study, Fiscpropionate F ranked among the top docked compounds, passed ADMET filters, and underwent detailed MD and MM-GBSA analyses. This strong binding affinity observed towards the F

420-binding oxidoreductase Rv1155 aligns with its reported anti-mycobacterial potential and supports the rationale for repurposing this scaffold for redox-based targeting of

M. tuberculosis.

4. Conclusions

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb), continues to be one of the world’s leading infectious diseases, escalated by the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR-TB) strains. The growing ineffectiveness of frontline therapies such as isoniazid and rifampin underscores the urgent need to discover novel anti-tubercular agents with alternative mechanisms of action.

In this study, we explored the deep-sea marine environment as a unique and chemically rich reservoir of novel scaffolds with potential anti-mycobacterial activity. A total of 2,773 marine-derived secondary metabolites from the CMNPD, Reaxys, and MarinLit databases were virtually screened against Rv1155, a key M. tuberculosis F420-binding oxidoreductase essential for maintaining redox balance and cellular metabolism. Through an integrated computational workflow combining molecular docking, in-silico ADMET profiling, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we identified three hit candidates: Upenamide (CMNPD_22964), Aspyronol (Compound_1749), and Fiscpropionate F (Compound_1796) with strong binding affinities and favourable pharmacokinetic properties.

Among these, Upenamide demonstrated the most favourable binding affinity and stable complex formation with Rv1155, as supported by MD trajectory analyses, including radius of gyration (Rg), hydrogen-bond persistence, MM-GBSA binding free energy and principal component analysis (PCA). Aspyronol also displayed promising binding affinity and a highly desirable ADMET profile, particularly for its low predicted blood–brain barrier permeability (PBB) relative to the native F4202 cofactor, suggesting selective intracellular targeting with minimal neurotoxicity. Despite showing dual conformations in RMSD plots, Aspyronol maintained PCA stability, indicating its potential for further optimisation.

Notably, while this study focused on a single F

420-dependent oxidoreductase (Rv1155) to establish a proof-of-concept for the proposed virtual screening pipeline,

M. tuberculosis is known to encode at least 28 distinct F

420-binding enzymes, each contributing uniquely to the pathogen’s redox potential and drug susceptibility [

40]. Extending this approach to other members of the F

420-enzyme family could offer a broader understanding of redox-driven metabolic networks and accelerate the discovery of broad-spectrum, mechanism-based anti-TB therapeutics.

Overall, these findings highlight the deep-sea as a promising source of anti-tubercular scaffolds. The integrated computational framework presented here provides a cost-effective and reliable approach to identify inhibitors targeting F420-dependent redox enzymes, which play a central role in M. tb’s physiology and drug resistance. This provides a foundation for future in vitro and in vivo validation of these hits.

The resurgence of tuberculosis, especially resistant forms, reaffirms the urgency of developing new therapeutics. Harnessing the chemical diversity of the deep-sea biosphere through advanced computational methodologies provides a promising direction for the next generation of anti-tubercular drug discovery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: The molecular docking scores of top docked deep-sea compounds and standard against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb) protein Rv1155; Table S2: Predicted ADMET parameters of the top scored deep-sea compounds and standard using ADMET 3.0

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.D.; A.A.A., and G.P.; methodology, R.D, A.A.A., G.P, R.V.A.; software, G.P.; validation, R.D., formal analysis, R.D, A.A.A., G.P.; investigation, R.D, G.P.; resources, M.J.; data curation, R.D, G.P..; writing—original draft preparation, R.D, R.V.A.; writing—review and editing, R.D, R.V.A, A.A.A., G.P, R.E., M.J.; visualisation, R.D, G.P.; supervision, R.E., M.J; project administration, R.E., M.J.; funding acquisition, R.E., M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the support of the Department for Environment and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) of the UK Government through its Global Centre on Biodiversity for Climate (GCBC) sponsored projects DEEPEND 1, DEEPEND 2 and the support of United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Horizon Europe Guarantee Fund for the HOTBIO project, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action Doctoral Network. We acknowledge the value of the free data-sharing platform CMNPD (

https://www.cmnpd.org) and the commercial database MarinLit (

https://marinlit.rsc.org/), which offer extensive chemical catalogues of marine natural products.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MJ, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Russell Gray from the Marine Biodiscovery Centre for his continued support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2025. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Clinical Overview of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Disease (https://www.cdc.gov/tb/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html).

- D. J. Newman and G. M. Cragg, “Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019,” J Nat Prod, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 770–803, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. N. Aguilar, N. P. Meléndez-Renteria, and K. N. Ramirez-Guzman, Exploration and Valorization of Natural Resources from Arid Zones. New York: Apple Academic Press, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. V. Rao, N. Kasanah, S. Wahyuono, B. L. Tekwani, R. F. Schinazi, and M. T. Hamann, “Three New Manzamine Alkaloids from a Common Indonesian Sponge and Their Activity against Infectious and Tropical Parasitic Diseases,” J Nat Prod, vol. 67, no. 8, pp. 1314–1318, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- K. V. Rao et al., “Manzamine B and E and Ircinal A Related Alkaloids from an Indonesian Acanthostrongylophora Sponge and Their Activity against Infectious, Tropical Parasitic, and Alzheimer’s Diseases,” J Nat Prod, vol. 69, no. 7, pp. 1034–1040, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Yousaf et al., “New Manzamine Alkaloids from an Indo-Pacific Sponge. Pharmacokinetics, Oral Availability, and the Significant Activity of Several Manzamines against HIV-I, AIDS Opportunistic Infections, and Inflammatory Diseases,” J Med Chem, vol. 47, no. 14, pp. 3512–3517, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- P. Pruksakorn et al., “Trichoderins, novel aminolipopeptides from a marine sponge-derived Trichoderma sp., are active against dormant mycobacteria,” Bioorg Med Chem Lett, vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 3658–3663, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H.-M. Hua et al., “Batzelladine alkaloids from the caribbean sponge Monanchora unguifera and the significant activities against HIV-1 and AIDS opportunistic infectious pathogens,” Tetrahedron, vol. 63, no. 45, pp. 11179–11188, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- N. Z. Abd Rani, Y. K. Lee, S. Ahmad, R. Meesala, and I. Abdullah, “Fused Tricyclic Guanidine Alkaloids: Insights into Their Structure, Synthesis and Bioactivity,” Mar Drugs, vol. 20, no. 9, p. 579, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, S. Parate, S. Yoon, G. Lee, and K. W. Lee, “Computational Simulations Identified Marine-Derived Natural Bioactive Compounds as Replication Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2,” Front Microbiol, vol. 12, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Jayaraman, V. Gosu, R. Kumar, and J. Jeyaraman, “Computational insights into potential marine natural products as selective inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA: A structure-based virtual screening study,” Comput Biol Chem, vol. 108, p. 107991, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Azhari, N. Merliani, M. Singgih, M. Arai, and E. Julianti, “Insights into Natural Products from Marine-Derived Fungi with Antimycobacterial Properties: Opportunities and Challenges,” Mar Drugs, vol. 23, no. 7, p. 279, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Zandi and R. Safari, “Computational Approaches in Natural Product Research: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions,” Advances in Energy and Materials Research, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 10–15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S.-Y. Huang and X. Zou, “Advances and Challenges in Protein-Ligand Docking,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 3016–3034, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Serghini, S. Portelli, and D. B. Ascher, “AI-Driven Enhancements in Drug Screening and Optimization,” 2024, pp. 269–294. [CrossRef]

- L. Harris et al., “Global distribution of deep-sea natural products shows environmental and phylogenetic undersampling and potential for biodiscovery,” Jul. 03, 2025. (in press). [CrossRef]

- “MarinLit a database of the marine natural products literature (https://marinlit.rsc.org/).”.

- “Reaxys (http://www.reaxys.com/).”.

- C. Lyu et al., “CMNPD: a comprehensive marine natural products database towards facilitating drug discovery from the ocean,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 49, no. D1, pp. D509–D515, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Eberhardt, D. Santos-Martins, A. F. Tillack, and S. Forli, “AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings,” J Chem Inf Model, vol. 61, no. 8, pp. 3891–3898, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. Trott and A. J. Olson, “AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading,” J Comput Chem, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 455–461, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. Wolber and T. Langer, “LigandScout: 3-D Pharmacophores Derived from Protein-Bound Ligands and Their Use as Virtual Screening Filters,” J Chem Inf Model, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 160–169, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. Fu et al., “ADMETlab 3.0: an updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage, improved performance, API functionality and decision support,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 52, no. W1, pp. W422–W431, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Eastman et al., “OpenMM 7: Rapid development of high performance algorithms for molecular dynamics,” PLoS Comput Biol, vol. 13, no. 7, p. e1005659, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Boothroyd et al., “Development and Benchmarking of Open Force Field 2.0.0: The Sage Small Molecule Force Field,” J Chem Theory Comput, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 3251–3275, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Sitkoff, K. A. Sharp, and B. Honig, “Accurate Calculation of Hydration Free Energies Using Macroscopic Solvent Models,” J Phys Chem, vol. 98, no. 7, pp. 1978–1988, Feb. 1994. [CrossRef]

- “Molecular docking and its application in search of antisickling agent from Carica papaya,” J Appl Biol Biotechnol, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 105–116, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. H. Mashalidis, A. G. Gittis, A. Tomczak, C. Abell, C. E. Barry, and D. N. Garboczi, “Molecular insights into the binding of coenzyme <scp> F 420 </scp> to the conserved protein <scp>R</scp> v1155 from <scp> M </scp> ycobacterium tuberculosis,” Protein Science, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 729–740, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Greening et al., “Physiology, Biochemistry, and Applications of F 420 - and F o -Dependent Redox Reactions,” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 451–493, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Lee, “The Role of F 420-dependent Enzymes in Mycobacteria Declaration,” 2017.

- G. Bashiri et al., “A revised biosynthetic pathway for the cofactor F420 in prokaryotes,” Nat Commun, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1558, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Agu et al., “Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 13398, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Johnson, “Role of Induced Fit in Enzyme Specificity: A Molecular Forward/Reverse Switch,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 283, no. 39, pp. 26297–26301, Sep. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Mhambi, D. Fisher, M. B. T. Tchokonte, and A. Dube, “Permeation Challenges of Drugs for Treatment of Neurological Tuberculosis and HIV and the Application of Magneto-Electric Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 1479, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. H. C. Litjens, R. E. Aarnoutse, and L. H. M. te Brake, “Preclinical models to optimize treatment of tuberculous meningitis – A systematic review,” Tuberculosis, vol. 122, p. 101924, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Jiménez et al., “‘Upenamide: An Unprecedented Macrocyclic Alkaloid from the Indonesian Sponge Echinochalina sp.,” J Org Chem, vol. 65, no. 25, pp. 8465–8469, Dec. 2000. [CrossRef]

- X.-W. Chen, C.-W. Li, C.-B. Cui, W. Hua, T.-J. Zhu, and Q.-Q. Gu, “Nine New and Five Known Polyketides Derived from a Deep Sea-Sourced Aspergillus sp. 16-02-1,” Mar Drugs, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 3116–3137, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu et al., “Polypropionate Derivatives with Mycobacterium tuberculosis Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase B Inhibitory Activities from the Deep-Sea-Derived Fungus Aspergillus fischeri FS452,” J Nat Prod, vol. 82, no. 12, pp. 3440–3449, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Selengut and D. H. Haft, “Unexpected Abundance of Coenzyme F 420 -Dependent Enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Other Actinobacteria,” J Bacteriol, vol. 192, no. 21, pp. 5788–5798, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).