Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Full Accounting for Spatial Effects

1.2. Depression Incidence in English Neighborhoods

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Outcome Data

2.2. Potential Predictors for Regression Models

2.3. Developing the Index of Neighborhood Social Cohesion: Cross-Scale Analysis

2.4. Initial Sifting of Predictors

2.5. Regression Strategy

2.6. Spatial Regimes

2.7. Measuring Goodness of Fit

3. Results

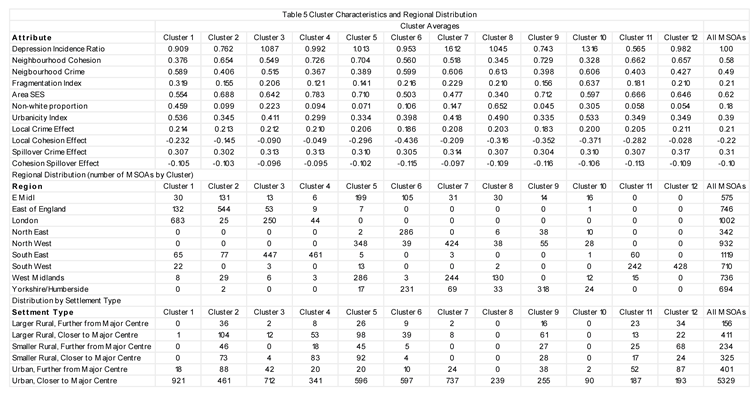

3.1. Findings from Cross-Scale Modelling Regarding Neighborhood Cohesion

3.2. Multicollinearity

3.3. Neighborhood Variations in Depression Incidence: Regression Sequence

3.4. Comparing Relative Depression Risks

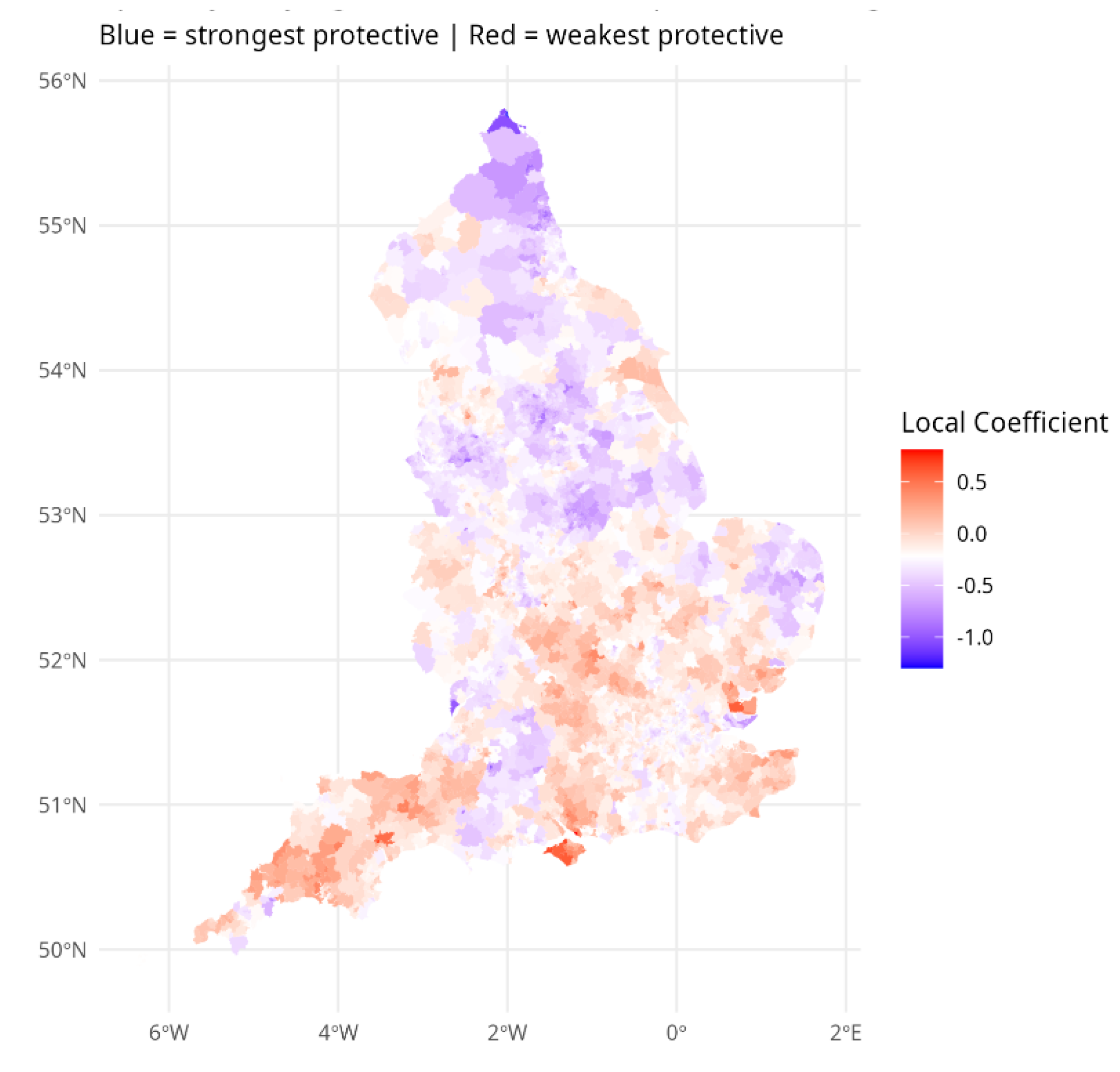

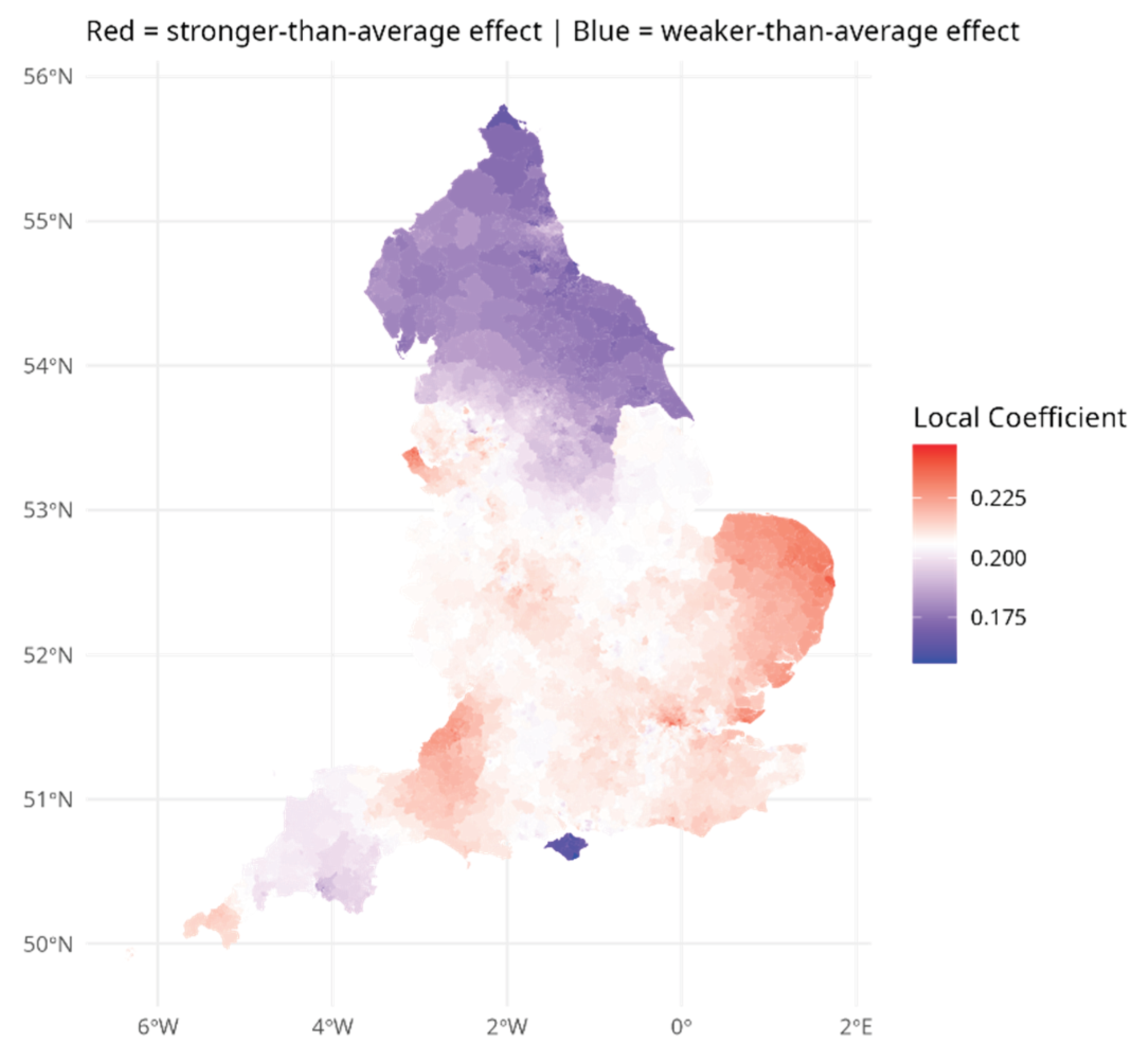

3.5. Models with Non-Stationarity

3.6. Implications for Spatial Regimes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix 1. Data Sources for Predictor Variables

Appendix 2. Cross-Scale Modelling Specification

Appendix 3. Non-Stationary Variance Specification: The Flexible Besag

References

- Propper, C., Jones, K., Bolster, A., Burgess, S., Johnston, R., Sarker, R. (2005) Local neighborhood and mental health: evidence from the UK. Social Science and Medicine, 61(10), 2065-2083. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. (2024) Computationally efficient localised spatial smoothing of disease rates using anisotropic basis functions and penalised regression fitting. Spatial Statistics, 59, 100796. [CrossRef]

- Mair, C., Diez Roux, A, Galea, S. (2008). Are neighborhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(11), 940-946. [CrossRef]

- March, D., Hatch, S., Morgan, C., Kirkbride, J, Bresnahan, M., Fearon, P., Susser, E. (2008) Psychosis and place. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30(1), 84-100. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L., Hameed, Y., Perez, J., Jones, P, Kirkbride, J (2018) Association of environment with the risk of developing psychotic disorders in rural populations: findings from the social epidemiology of psychoses in East Anglia study. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(1), 75-83.

- Barnett, A., Zhang, C. J., Johnston, J, Cerin, E. (2018) Relationships between the neighborhood environment and depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1153-1176. [CrossRef]

- Breedvelt, J, Tiemeier, H., Sharples, E., Galea, S., Niedzwiedz, C., Elliott, I., Bockting, C (2022). The effects of neighbourhood social cohesion on preventing depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults: rapid review. BJPsych Open, 8(4), e97. [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Genderson, M., Pruchno, R. (2013) Effects of neighborhood violence and perceptions of neighborhood safety on depressive symptoms of older adults. Social Science and Medicine, 85, 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Pignon, B., Schürhoff, F., Baudin, G., Ferchiou, A., Richard, J, Saba, G., Szöke, A. (2016) Spatial distribution of psychotic disorders in an urban area of France: an ecological study. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 26. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J., Li, G., Aragon, M, Coventry, P, Jacobs, R., Prady, S, White, P (2022). Association of environmental and socioeconomic indicators with serious mental illness diagnoses identified from general practitioner practice data in England: A spatial Bayesian modelling study. PLoS medicine, 19(6), e1004043. [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, J, Lunn, D, Morgan, C., Lappin, J, Dazzan, P., Morgan, K., Jones, P (2010). Examining evidence for neighborhood variation in the duration of untreated psychosis. Health and Place, 16(2), 219-225. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A, Lee, D (2017) Bayesian Disease Mapping for Public Health. Chapter 16 in Handbook of Statistics, Science Direct. [CrossRef]

- Waller L, Carlin B (2010) Disease mapping. Chapter 14 In Handbook of Modern Statistical Methods, Chapman Hall CRC, pp 217–243.

- Reich, B, Yang, S., Guan, Y., Giffin, A, Miller, M, Rappold, A. (2021). A review of spatial causal inference methods for environmental and epidemiological applications. International Statistical Review, 89(3), 605-634. [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. (2002) Under the hood issues in the specification and interpretation of spatial regression models. Agricultural Economics, 27(3), 247-267.

- Giffin, A., Reich, B, Yang, S., Rappold, A (2023) Generalized propensity score approach to causal inference with spatial interference. Biometrics, 79(3), 2220-2231. [CrossRef]

- Sarrias, M., Molina-Varas, A. (2022). Your air pollution makes me sick!: Estimating the spatial spillover effects of PM2. 5 emissions on emergency room visits in Chile. Region, 9(2), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Graif, C. (2015). Delinquency and gender moderation in the moving to opportunity intervention: The role of extended neighborhoods. Criminology, 53(3), 366-398. [CrossRef]

- 19. Fotheringham, A, Brunsdon, C, Charlton M (2002) Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships, Wiley: New York.

- Vidoli F, Benedetti R (2022) SpatialRegimes package: a brief introduction to spatial clusterwise regression with a focus on SkaterF function. https://fvidoli.shinyapps.io/SpatialRegimes_app/.

- Sridharan, S., Koschinsky, J, Walker, J (2011). Does context matter for the relationship between deprivation and all-cause mortality? The West vs. the rest of Scotland. International Journal of Health Geographics, 10(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, V., Rigatti, T., Shaikh, A., Ferraioli, T. (2023). Spatial health predictors for depressive disorder in Manhattan: a 2020 analysis. Cureus, 15(7). [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., Kim, H. (2017). Analysis of the relationship between community characteristics and depression using geographically weighted regression. Epidemiology and Health, 39, e2017025. [CrossRef]

- Leyk, S., Norlund, P, Nuckols, J (2012) Robust assessment of spatial non-stationarity in model associations related to pediatric mortality due to diarrheal disease in Brazil. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology, 3(2), 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Assunção, R (2003) Space varying coefficient models for small area data. Environmetrics, 14(5), 453-473. [CrossRef]

- Fattah E, Krainski E, van Niekerk J, Rue H (2024) Non-stationary Bayesian spatial model for disease mapping based on sub-regions. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 33(6): 1093-1111.

- Besag, J., York, J., Mollié, A. (1991) Bayesian image restoration, with two applications in spatial statistics. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 43, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Simpson D, Rue H, Riebler A, Martins T, Sørbye, S (2017) Penalising model component complexity: a principled, practical approach to constructing priors. Statist. Sci. 32 (1) 1 – 28. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. (2007) Spatial stochastic volatility for lattice data. Journal of Agricultural, Biological, and Environmental Statistics, 12(1), 25–40. [CrossRef]

- Otto, P., Doğan, O., Taşpınar, S., Schmid, W, Bera, A (2025) Spatial and spatiotemporal volatility models: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 39(3), 1037-1091. [CrossRef]

- Arambepola, R., Lucas, T, Nandi, A, Gething, P, Cameron, E (2022) A simulation study of disaggregation regression for spatial disease mapping. Statistics in Medicine, 41(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Sturrock H, Cohen J, Keil P, Tatem A, Le Menach A, Ntshalintshali N, Hsiang M, Gosling R (2014) Fine-scale malaria risk mapping from routine aggregated case data. Malaria Journal, 13(1), 421. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E, Sutcliffe, D., Lacey, T., Stokes, T. (2013) Assessing depression severity using the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework depression indicators: a systematic review. Br J General Practice, 63(610), e309. [CrossRef]

- Forbes L, Marchand C, Doran T, Peckham S (2017) The role of the Quality and Outcomes Framework in the care of long-term conditions: A systematic review. Br J General Practice, 67(664): e775-e784. [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, J, Anglin, D, Colman, I., Dykxhoorn, J., Jones, P, Patalay, P, Griffiths, S (2024) The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry, 23(1), 58-90. [CrossRef]

- Tsimpida, D., Tsakiridi, A., Daras, K., Corcoran, R., Gabbay, M (2024) Unravelling the dynamics of mental health inequalities in England: a 12-year nationwide longitudinal spatial analysis of recorded depression prevalence. SSM-Population Health, 26, 101669. [CrossRef]

- Allardyce, J, Gilmour, H, Atkinson, J, Rapson, T, Bishop, J, McCreadie, R (2005) Social fragmentation, deprivation and urbanicity: relation to first-admission rates for psychoses. Brit J. Psych, 187(5), 401-406. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S., Congdon, P, Atkinson, S., Corcoran, R., MaGuire, R., Peasgood, T. (2019) Individual and local area factors associated with self-reported wellbeing, perceived social cohesion and sense of attachment to one’s community: analysis of the Understanding Society Survey: Research Report. What Works for Wellbeing Technical Report. Durham Research Online, http://dro.dur.ac.uk.

- Buckner, J (1988) The development of an instrument to measure neighborhood cohesion. Amer J Comm Psych, 16(6), 771-791. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y, Ailshire, J (2024). Perceived neighborhood disorder, social cohesion, and depressive symptoms in spousal caregivers. Aging and Mental Health, 28(1), 54-61. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J., To, H, Chan, E. (2006). Reconsidering social cohesion: Developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research. Social Indicators Research, 75(2), 273-302. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, L., Ettman, C, Galea, S. (2020) Urbanization, urbanicity, and depression: a review of the recent global literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(3), 233-244. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N., Brown, C., Raman, S., Porta, S., Jenks, M., Jones, C., Bramley, G. (2010) Elements of urban form. Chapter 2 in Dimensions of the Sustainable City, M. Jenks and C. Jones (eds), Springer pp 21-51.

- Baranyi, G., Cherrie, M., Curtis, S., Dibben, C., Pearce, J (2020) Neighborhood crime and psychotropic medications: a longitudinal data linkage study of 130,000 Scottish adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(5), 638-64. [CrossRef]

- Williams, E. D., Tillin, T., Richards, M., Tuson, C., Chaturvedi, N., Hughes, A, Stewart, R. (2015) Depressive symptoms are doubled in older British South Asian and Black Caribbean people compared with Europeans: associations with excess co-morbidity and socioeconomic disadvantage. Psychological Medicine, 45(9), 1861-1871. [CrossRef]

- Department for Culture, Media & Sport (2024) Community Life Survey 2023/24 Online Questionnaire. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk.

- Lunn, D., Spiegelhalter, D., Thomas, A, Best, N. (2009) The BUGS project: Evolution, critique and future directions. Statistics in Medicine, 28(25), 3049-3067. [CrossRef]

- Department for Culture, Media & Sport (2024) Community Life Survey 2023/24: Neighbourhood and community. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/community-life-survey-202324-annual-publication/community-life-survey-202324-neighbourhood-and-community.

- Chavent M, Kuentz-Simonet V, Labenne A, Saracco J (2018) ClustGeo: an R package for hierarchical clustering with spatial constraints. Comput Stat , 33: 1799-1822. [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalter, D, Best, N, Carlin, B, van der Linde, A (2002) Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 64 (4): 583–639. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S (2013) A Widely Applicable Bayesian Information Criterion. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 14: 867–897.

- Office of National Statistics (2025) 2021 Rural Urban Classification. https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/geographicalproducts/ruralurbanclassifications/2021ruralurbanclassification.

- Kang, S., Cramb, S., White, N., Ball, S., Mengersen, K. (2016) Making the most of spatial information in health: a tutorial in Bayesian disease mapping for areal data. Geospatial health, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Comber, A., Brunsdon, C., Charlton, M., Dong, G., Harris, R., Lu, B, Harris, P. (2023). A route map for successful applications of geographically weighted regression. Geographical Analysis, 55(1), 155-178. [CrossRef]

- Forastiere L, Airoldi E, Mealli F (2021) Identification and estimation of treatment and interference effects in observational studies on networks, J. Amer. Stat. Assoc., 116, 901–918. [CrossRef]

- Mair, C., Roux, A, Shen, M., Shea, S., Seeman, T., Echeverria, S, O'meara, E (2009). Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of neighborhood cohesion and stressors with depressive symptoms in the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Annals of epidemiology, 19(1), 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, E., Moore, S. (2013). Social capital and depressive symptoms: the association of psychosocial and network dimensions of social capital with depressive symptoms in Montreal, Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 86, 96-102. [CrossRef]

| Log Odds Ratio Coefficients | |||

| Sense of Belonging | |||

| Mean | 2.5% | 97.5% | |

| Area SES | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.73 |

| Proportion Non-white | -0.22 | -0.40 | 0.02 |

| Urbanicity | -1.35 | -1.73 | -0.99 |

| Many Neighbors can be Trusted | |||

| Mean | 2.5% | 97.5% | |

| Area SES | 2.78 | 2.56 | 3.07 |

| Proportion Non-white | -0.85 | -1.14 | -0.63 |

| Urbanicity | -1.90 | -2.29 | -1.40 |

| Chat with Neighbors More than Once a Month | |||

| Mean | 2.5% | 97.5% | |

| Area SES | -0.12 | -0.38 | -0.12 |

| Proportion Non-white | -0.34 | -0.51 | -0.34 |

| Urbanicity | -2.74 | -3.05 | -2.75 |

| Settlement Category | ||||

| Region | Larger rural | Smaller rural | Urban | Total |

| East Midlands | 47 | 76 | 9 | 22 |

| Eastern England | 34 | 66 | 11 | 22 |

| London | - | - | 3 | 3 |

| North East | 24 | 100 | 11 | 15 |

| North West | 66 | 95 | 15 | 21 |

| South East | 55 | 91 | 15 | 25 |

| South West | 54 | 99 | 12 | 33 |

| West Midlands | 63 | 98 | 9 | 19 |

| Yorkshire-Humber | 64 | 100 | 11 | 21 |

| All of England | 50 | 88 | 10 | 20 |

| Coefficients represent Logged Relative Risks with Predictors on [0,1] scale | ||||

| Model Specification (and Identifier) | Parameter Profile | |||

| Baseline (M1) | Mean | St devn | 2.5% | 97.5% |

| Intercept | 0.039 | 0.045 | -0.050 | 0.127 |

| Area SES | -0.149 | 0.042 | -0.231 | -0.066 |

| Proportion Non-white | 0.031 | 0.038 | -0.043 | 0.106 |

| Crime Index | 0.285 | 0.040 | 0.207 | 0.363 |

| Neighbourhood Cohesion | -0.276 | 0.053 | -0.379 | -0.173 |

| Including Spatial Lags (Cohesion, Crime) (M2) | Mean | St devn | 2.5% | 97.5% |

| Intercept | 0.012 | 0.095 | -0.174 | 0.198 |

| Area SES | -0.192 | 0.043 | -0.276 | -0.108 |

| Proportion Non-white | -0.013 | 0.039 | -0.089 | 0.064 |

| Crime Index | 0.243 | 0.040 | 0.165 | 0.322 |

| Neighbourhood Cohesion | -0.191 | 0.054 | -0.297 | -0.086 |

| Crime Spillover | 0.306 | 0.085 | 0.139 | 0.473 |

| Cohesion Spillover | -0.195 | 0.082 | -0.356 | -0.035 |

| Non-Stationary Environments (Cohesion, Crime) and Spatial Lags (M3) | Mean | St devn | 2.5% | 97.5% |

| Intercept | 0.028 | 0.094 | -0.156 | 0.211 |

| Area SES | -0.150 | 0.042 | -0.231 | -0.068 |

| Proportion Non-white | -0.044 | 0.038 | -0.118 | 0.031 |

| Crime Index | 0.242 | 0.040 | 0.163 | 0.321 |

| Neighbourhood Cohesion | -0.274 | 0.053 | -0.378 | -0.169 |

| Crime Spillover | 0.300 | 0.084 | 0.135 | 0.465 |

| Cohesion Spillover | -0.178 | 0.079 | -0.334 | -0.022 |

| Non-Stationary Environments, Spatial Lags and Non-Stationary Region Precisions (M4) | Mean | St devn | 2.5% | 97.5% |

| Intercept | 0.034 | 0.095 | -0.152 | 0.220 |

| Area SES | -0.249 | 0.041 | -0.329 | -0.169 |

| Proportion Non-white | -0.089 | 0.038 | -0.162 | -0.015 |

| Crime Index | 0.206 | 0.040 | 0.128 | 0.284 |

| Neighbourhood Cohesion | -0.219 | 0.052 | -0.321 | -0.118 |

| Crime Spillover | 0.309 | 0.085 | 0.143 | 0.475 |

| Cohesion Spillover | -0.104 | 0.079 | -0.259 | 0.051 |

| Model Fit | ||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| DIC | 58647 | 58519 | 58010 | 56307 |

| WAIC | 58173 | 58098 | 57431 | 55359 |

| Mean Absolute Deviation | 4.916 | 4.882 | 4.415 | 3.334 |

| Fitted Relative Risks of Depression Incidence | ||||

| Region | Larger rural | Smaller rural | Urban | All Settlement Types |

| East Midlands | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.82 |

| East of England | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.74 |

| London | - | - | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| North East | 0.95 | 0.72 | 1.10 | 1.07 |

| North West | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.50 | 1.46 |

| South East | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.05 |

| South West | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| West Midlands | 1.04 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 1.15 |

| Yorks/Humberside | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 0.87 |

| England | 0.86 | 0.82 | 1.03 | 1.00 |

| Environmental Risk Factor Impacts | ||||

| Larger rural | Smaller rural | |||

| ` | Crime Effect | Cohesion Effect | Crime Effect | Cohesion Effect |

| East Midlands | 0.20 | -0.26 | 0.20 | -0.26 |

| East of England | 0.22 | -0.12 | 0.22 | -0.20 |

| London | - | - | - | - |

| North East | 0.17 | -0.40 | 0.17 | -0.48 |

| North West | 0.19 | -0.26 | 0.19 | -0.24 |

| South East | 0.21 | -0.04 | 0.21 | -0.04 |

| South West | 0.21 | -0.10 | 0.21 | -0.10 |

| West Midlands | 0.21 | -0.15 | 0.21 | -0.16 |

| Yorks/Humberside | 0.19 | -0.35 | 0.18 | -0.31 |

| England | 0.20 | -0.19 | 0.21 | -0.16 |

| Urban | All Settlement Types | |||

| Region | Crime Effect | Cohesion Effect | Crime Effect | Cohesion Effect |

| East Midlands | 0.20 | -0.30 | 0.20 | -0.29 |

| East of England | 0.21 | -0.16 | 0.22 | -0.16 |

| London | 0.21 | -0.23 | 0.21 | -0.23 |

| North East | 0.18 | -0.41 | 0.18 | -0.41 |

| North West | 0.21 | -0.32 | 0.20 | -0.31 |

| South East | 0.21 | -0.06 | 0.21 | -0.05 |

| South West | 0.21 | -0.17 | 0.21 | -0.15 |

| West Midlands | 0.21 | -0.17 | 0.21 | -0.17 |

| Yorks/Humberside | 0.19 | -0.39 | 0.19 | -0.38 |

| England | 0.21 | -0.23 | 0.21 | -0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).