1. Introduction

Since the emergence of the first single cell organisms, natural products have co-evolved with all kingdoms of life to deliver a multitude of survival advantages – defending against predators/competitors, immobilising/killing prey, facilitating reproduction, and articulating intra/inter species communication and ecological behaviour. With the advent of modern science, knowledge of the molecular structures and properties of natural products has provided valuable insights into what is often synthetically challenging/inaccessible regions of chemical space, populated by diverse structures featuring complex carbo/heterocyclic scaffolds, functionality and chirality. Many natural products possess potent and selective ecological, chemical and biological properties, knowledge of which has informed our understanding of living systems, inspiring many of the world’s most successful drugs, agrochemicals and biomaterials, and fuelling a revolution in industry, commerce, healthcare and agriculture. Notwithstanding the extraordinary impact that natural products have had on science and society, the innate chemical reactivity of some natural products both defines their uniqueness and potential, while simultaneously presenting a technical challenge. For example, some natural products partially or completely transform into artifacts during extraction, isolation, handling and/or storage. When these transformations go unnoticed, it represents a lost opportunity, as we forgo insights into molecular structures and chemical reactivity that might otherwise inform biosynthetic investigations, biomimetic syntheses, structure activity relationships (SAR), mechanisms of action, and ultimately advance drug discovery and development.

Recent reviews in the area of natural product artifacts have been predominantly focused on analytical chemistry, and for the most part do not address the chemical reactivity of natural products at a mechanistic or molecular level.[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] An exception to this trend (2020, Capon)[

7] presents the case for extracting value from mechanistic insights into the formation of natural products artifacts, using selected marine natural product case studies. This current review returns to and expands on that earlier value proposition, to address the inter-connected concepts of natural product artifacts and innate chemical reactivity — as illustrated by a new set of marine and microbial natural product case studies, with particular attention paid to the factors that initiate, and the underlying mechanisms behind, artifact formation (

Table 1). For example, given the critical and nearly ubiquitous role of solvents in natural products science, we survey the risks posed by different solvents in artifact formation. We also explore the influence of heat, pH, light and air, and the propensity of certain classes of natural products to undergo structural diversification through the likes of acetal equilibration,

trans-esterification and epimerisation. Another noteworthy discussion point is the specialised subset of cryptic natural products, those endowed with levels of chemical reactivity so high as to preclude detection and isolation. The “unknown unknowns” of the natural product world, such natural products are often only hinted at by the artifacts they leave behind. For the observant researcher, however, perseverance can be rewarded by a hidden cache of knowledge. Finally, we draw attention to a phenomenon where natural products applied to cell-based bioassays undergo

in situ biotransformation. Reports on this phenomenon are not prominent in the natural products literature. This is unfortunate, as a failure to acknowledge biotransformation risks can compromise bioassay data analysis and distort conclusions related to potency and selectivity, SAR, pharmacophores and mechanisms-of-action.

In the concluding remarks, the authors integrate the case studies presented and their own experiences to outline best practices for detecting and mitigating artifact formation, and, equally importantly, for recognising it and leveraging the insights it can provide.

Table 1.

Case Studies in Marine and Microbial Natural Products.

Table 1.

Case Studies in Marine and Microbial Natural Products.

| 2 Solvent |

cavoxin/cavoxone |

photopiperazines |

| 2.1 DMSO |

pyrrolizin-3-ones |

aspochracin/sclerotiolides |

| migrastatins/dorrigocins |

2.7 dichloromethane |

clavosines/calyculins |

| discorhabdins |

bromotyramines |

5.2 Photooxidation |

| dendrillic acids |

2.8 benzene |

cadinanes |

| methylsulfonated polyketides |

theonellastrols |

5.3 Photoreactive |

| cerulenin |

2.9 ethyl acetate |

chetomins |

| bisanthraquinones |

sorbicillinol/sorbivetone |

talaromycins/purpactins |

| glyclauxins |

2.10 aprotic vs protic |

6 Air oxidation |

| aculeaxanthones/chrysoxanthones |

oxandrastins |

ketidocillinones |

| versixanthones |

alaeolide |

pseudopyronines |

| secalonic acid/parnafungins |

pratensilins |

norpectinatone |

| 2.2 pyridine |

3 Heat |

linfuranones |

| acremoxanthone/acremonidins |

psammaplins/bastadins |

hyafurones/aurafurones |

| 2.3 methanol |

creolophins |

avermectins |

| brevianamides |

neobulgarones |

penilumamides |

| talaronins |

4 pH |

7 Acetal/ketal equilibration |

| pyrasplorins |

4.1 basic |

okichromanone |

| penicipyridones |

pestalone/pestalachloride |

sphydrofuran |

| varacins |

neoenterocins |

8 Trans-esterification |

| epithiodiketopiperazines |

asperazepanones |

kipukasins |

| eleutherobins/caribaeoranes |

hydroxybrevianamides |

glenthmycins |

| 2.4 acetone |

salinosporamides |

amaurones |

| kutzneridines |

4.2 acidic |

9 Epimerization |

| enamidonins/K97-0239A and B |

enterocins |

aspergillazines |

| autucedines |

serratiochelin |

quinolactacins |

| madurastatins |

franklinolides |

10 Cryptic natural products |

| drimanes |

oxanthromicins/eurotones |

N-amino-l-proline methyl ester |

| duclauxin/verruculosins |

4.3 silica gel |

prolinimines |

| 2.5 acetonitrile |

sphydrofurans |

N-amino-anthranilic acid |

| talcarpones |

duclauxin/bacillisporins |

penipacids |

| 2.6 chloroform |

xenoclauxin/talaromycesone B |

elansolids |

| greensporones |

xanthepinone |

11 Bioassay biotransformation |

| alkyl resorcinols |

daldinones |

abyssomicins |

| azodyrecins |

5 Light |

roseopurpurins |

| schipenindolenes |

5.1 Photoisomerization |

kendomycin/goondomycins |

| shearinines |

pyranpolyenolides |

|

2. Solvents

To isolate, identify and study natural products first requires extraction from the producing organism (i.e. a microbial fermentation, or a macro marine organism such as a sponge, alga, tunicate etc…), followed by fractionation, spectroscopic, chemical and biological data acquisition and analysis, as well as handling and storage. All these processes require exposure to solvents, leaving open the possibility of forming artifacts. As is evident from the case studies outlined below, while all solvents bring with them some risk of forming artifacts, some solvents clearly present higher risk than others.

2.1. DMSO

migrastatins/dorrigocins (Figure 2.1.1)

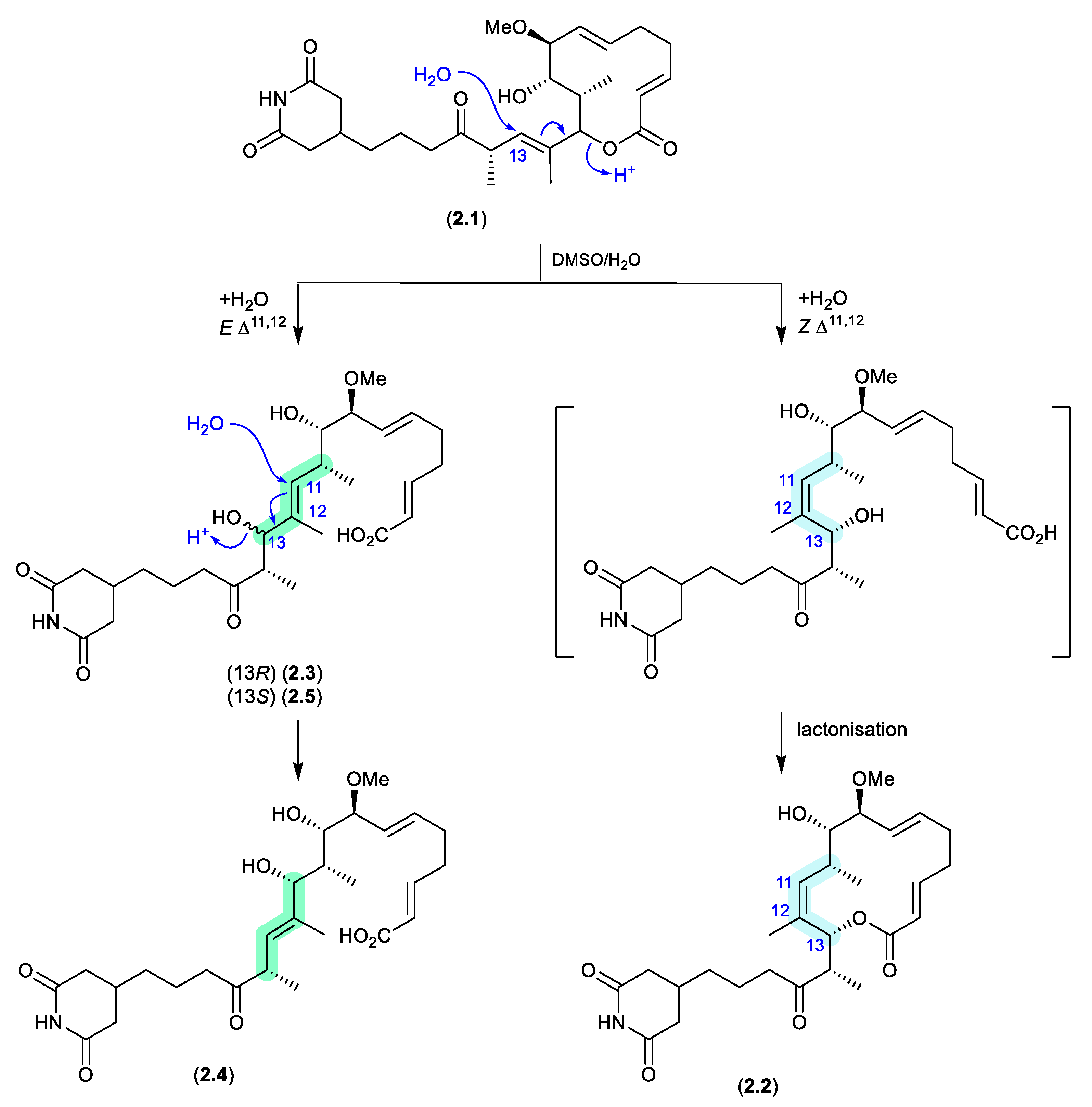

The glutarimide polyketides,

iso-migrastatin (

2.1), migrastatin (

2.2), and dorrigocins A (

2.3) and B (

2.4), were initially isolated as co-metabolites of

Streptomyces platensis (NRRL 18993).[

8,

9] Subsequent studies identified an additional analogue, 13-

epi-dorrigocin A (

2.5), and revealed that

2.1 alone was a natural product, with

2.2 to

2.5 produced when

2.1 was stored in DMSO-H

2O.[

10] These latter transformations can be rationalised as H

2O addition to C-13 with concomitant double bond migration and opening of the macrolactone to generate

E and

Z D

11,12 isomers: the

E isomer leads to dorrigocin A (

2.3), 13-

epi-dorrigocin A (

2.5) and dorrigocin B (

2.4) and the

Z isomer undergoes relactonisation to yield migrastatin (

2.2). Knowledge of this chemical reactivity was later exploited to produce a library of

iso-migrastatin congeners,[

11] while further studies demonstrated a direct thermally induced [

3,

3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of

2.1 to

2.2 paving the way for new analogues.[

12]

Figure 2.

1.1. discorhabdins (Figure 2.1.2).

Figure 2.

1.1. discorhabdins (Figure 2.1.2).

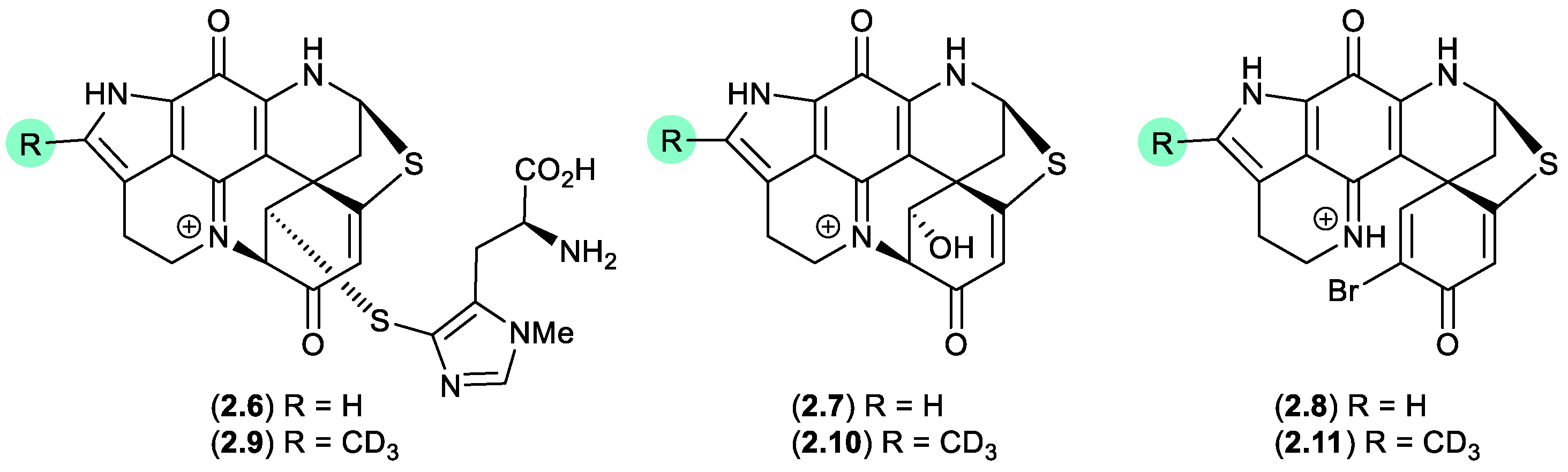

On handling in DMSO-

d6, the three pyrroloiminoquinone discorhabdins H (

2.6), L (

2.7) and B (

2.8), isolated from the New Zealand marine sponge

Latrunculia kaakaariki, transformed to the trideuteromethyl artifacts

2.9–

2.11.[

13] Investigations into the mechanism behind this transformation suggested it occurred during recovery of NMR (DMSO

-d6) samples in the presence of MeOH, H

2O, and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (with all three of these solvents being essential for efficient incorporation of the CD

3 moiety). ICP-MS revealed trace levels of iron present in both the DMSO-

d6 and TFA, presumably initiating OH radicals via a Fenton reaction.

Figure 2.

1.2 dendrillic acids (Figure 2.1.3).

Figure 2.

1.2 dendrillic acids (Figure 2.1.3).

On handling in DMSO-

d6, the spongian norditerpenoid dendrillic acids A (

2.12) and B (

2.13), isolated from the Western Australian marine sponge

Dendrilla sp., readily equilibrated at room temperature (r.t.) to an epimeric mixture (

2.12/

2.13).[

14] This epimerisation likely proceeds via enolization of the lactam to an achiral pyrrolo intermediate, as supported by partial incorporation of deuterium into the γ-lactam methine when 5% D

2O was added to the DMSO-

d6 solution.

Figure 2.

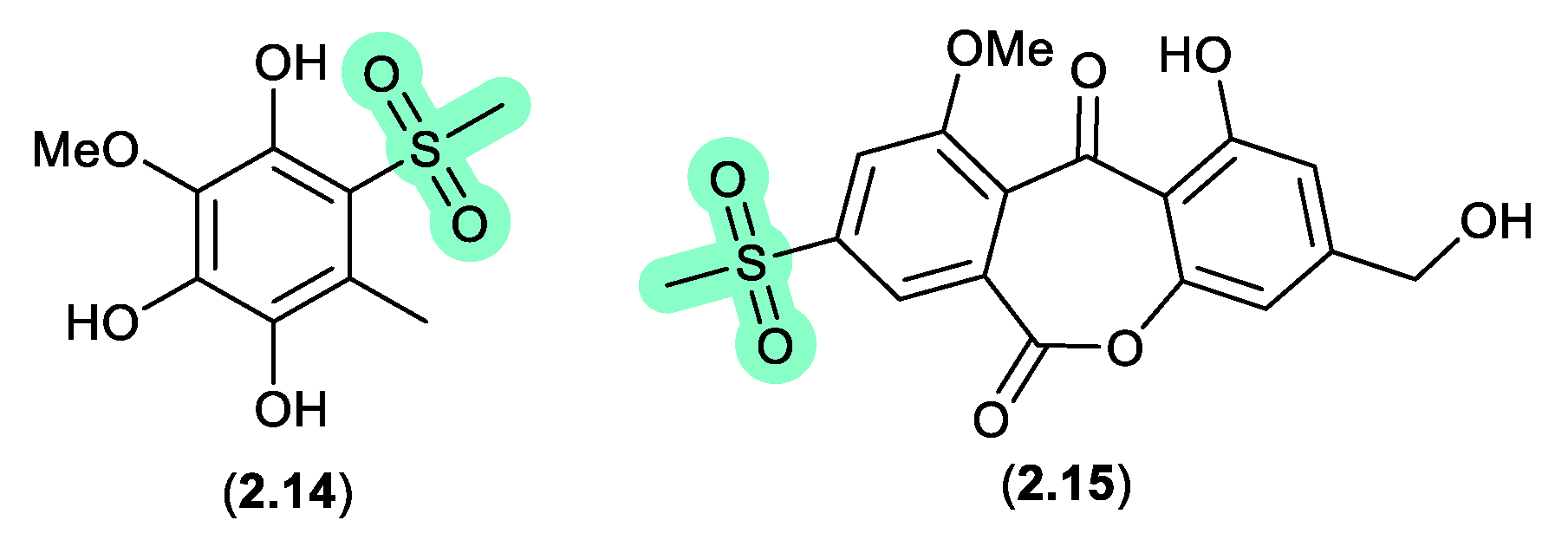

1.3 methylsulfonated polyketides (Figure 2.1.4).

Figure 2.

1.3 methylsulfonated polyketides (Figure 2.1.4).

Supplementation of a fermentation of a mangrove-derived fungus

Neosartorya udagawae HDN13-313 with a DMSO solution of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacytidine yielded the methylsulfonylated artifacts

2.14 and neosartoryone A (

2.15).[

15] Investigating this transformation revealed that a fermentation supplemented with DMSO alone also produced

2.14, which suggested that the methylsulfonyl moiety was derived from DMSO. In support of this hypothesis, fermentation in the presence of DMSO-

d6 returned the corresponding deuterated analogues of both

2.14 and

2.15.

Figure 2.

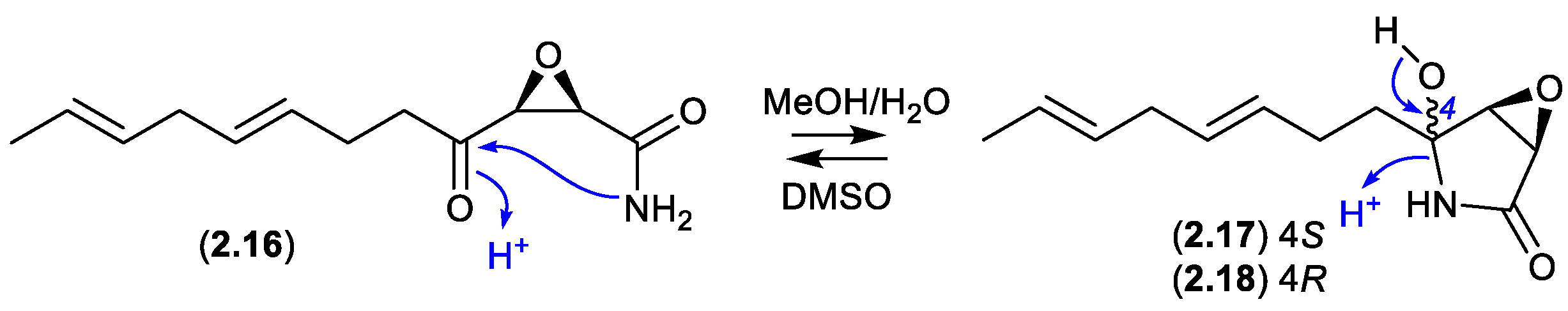

1.4 cerulenin (Figure 2.1.5).

Figure 2.

1.4 cerulenin (Figure 2.1.5).

Cerulenin (

2.16), originally reported mid last century from the fungus

Cephalosporium caerulens KF-140, was the first reported natural fatty acid synthase inhibitor, with anticancer, antifungal and anti-obesity potential. In protic solvents

2.16 undergoes intramolecular 5-

exo-trig cyclization to generate cerulenin hydroxylactams

2.17 and

2.18. For example, a recent report confirmed that an NMR (DMSO-

d6) sample exists almost entirely in the acyclic form (

2.16), whereas LC-MS in MeOH/H

2O/HCO

2H revealed a three-component mixture (

2.16–

2.18).[

16]

Figure 2.

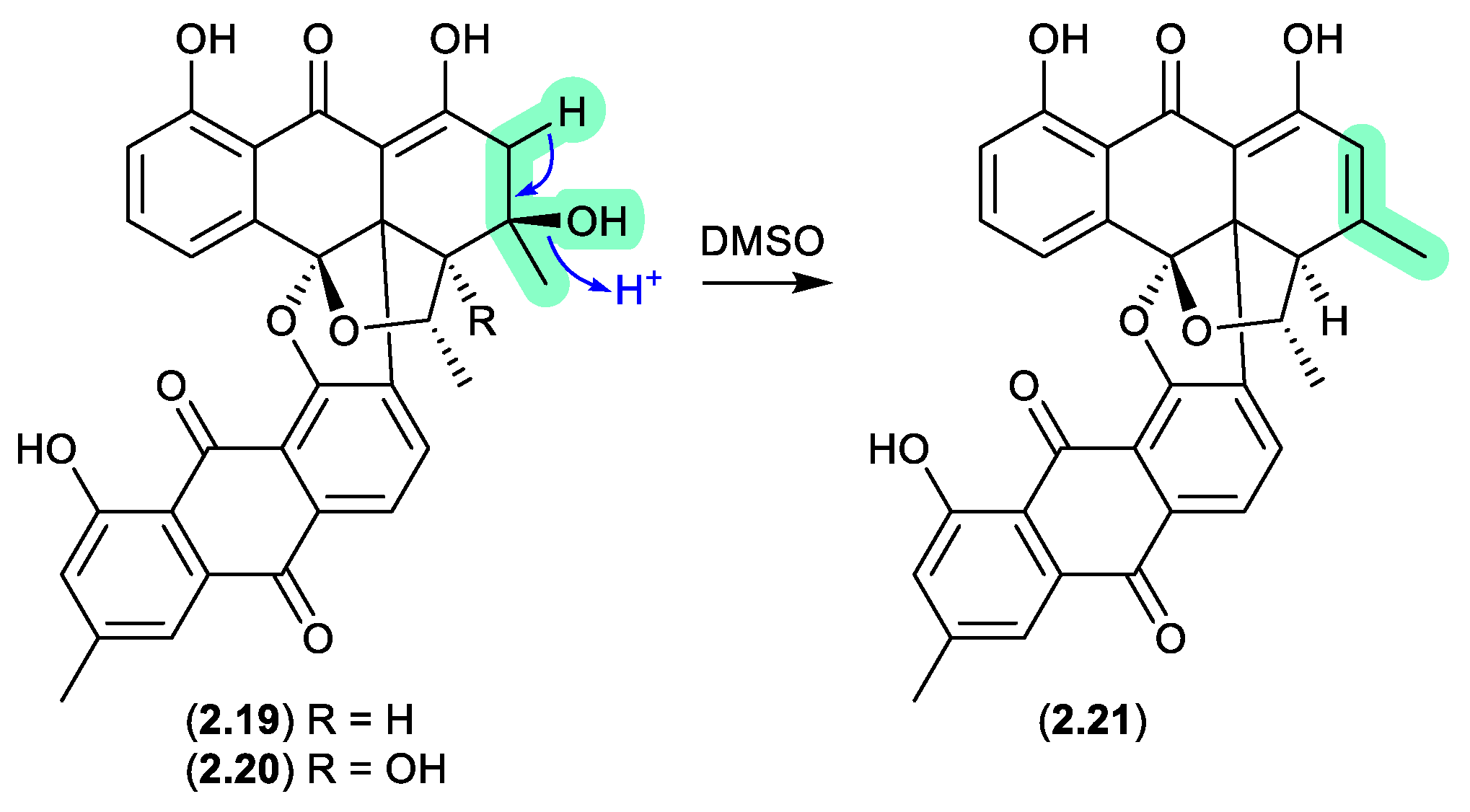

1.5 bisanthraquinones (Figure 2.1.6).

Figure 2.

1.5 bisanthraquinones (Figure 2.1.6).

An investigation into a

Streptomyces sp. isolated from a cyanobacterium associated with the Puerto Rican tunicate

Ecteinascidia turbinata yielded two antibacterial bisanthraquinones,

2.19 and

2.20.[

17] During long NMR (DMSO-

d6) acquisitions both these metabolites degraded to a single common dehydration artifact

2.21. Partial conversion of

2.19 to

2.21 was also achieved by allowing

2.19 to stand at r.t. in DMSO for several days. Of note, the artifact

2.21 was 220-fold more active against methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) than the parent natural product

2.19.

Figure 2.

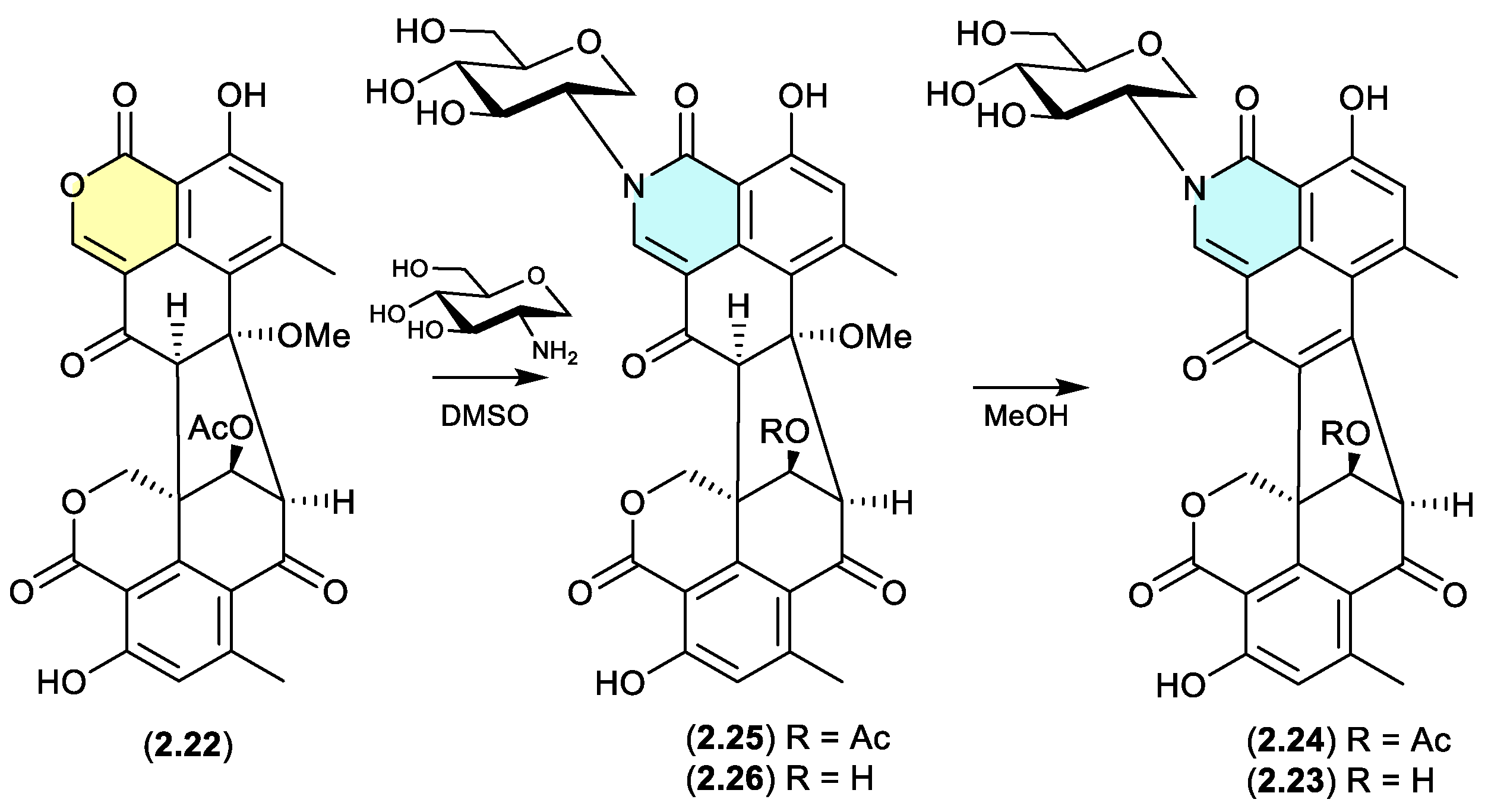

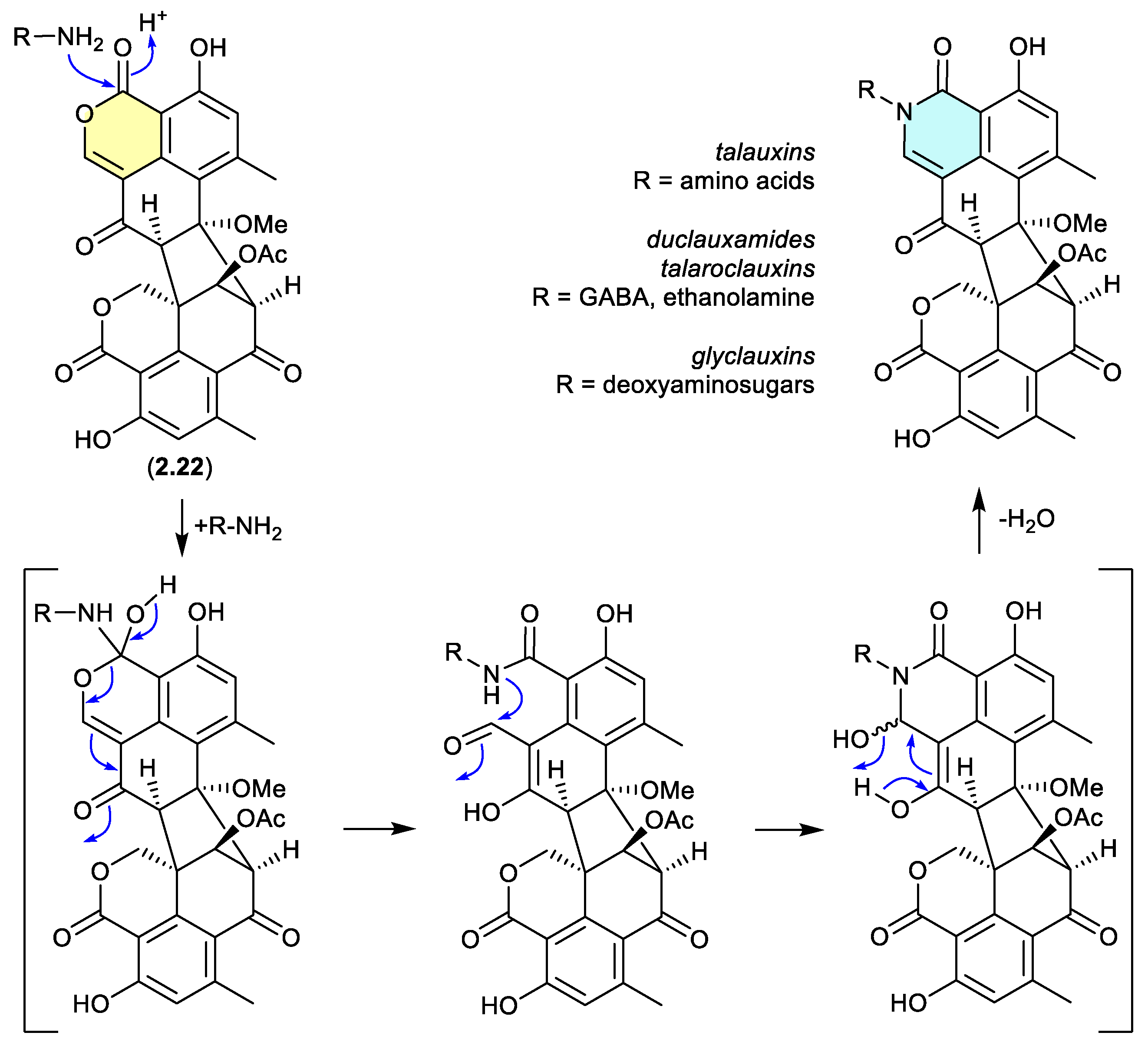

1.6 glyclauxins (Figure 2.1.7).

Figure 2.

1.6 glyclauxins (Figure 2.1.7).

The Australian wasp nest-derived fungus

Talaromyces sp. CMB-MW102 yielded the known duclauxin (

2.22) (see

Section 4.3) and a series of 1-deoxy-

d-glucosamine adducts, glyclauxins A–E.[

18] In an effort to understand the biosynthetic relationship between duclauxin and glyclauxins, and implement a biomimetic synthesis, a r.t. DMSO solution of

2.22 and synthetic 1-deoxy-

d-glucosamine underwent quantitative conversion to glyclauxin B (

2.24), while MeOH solutions of glyclauxins C (

2.25) and D (

2.26) underwent rapid and quantitative transformation to glyclauxins B (

2.24) and A (

2.23), respectively. Despite the ease of these latter transformations, both

2.23 and

2.24 were detected in fresh unfractionated culture extracts — attesting to their dual status as both natural products and artifacts (see Section 12).

Figure 2.

1.7 aculeaxanthones/chrysoxanthones (Figure 2.1.8).

Figure 2.

1.7 aculeaxanthones/chrysoxanthones (Figure 2.1.8).

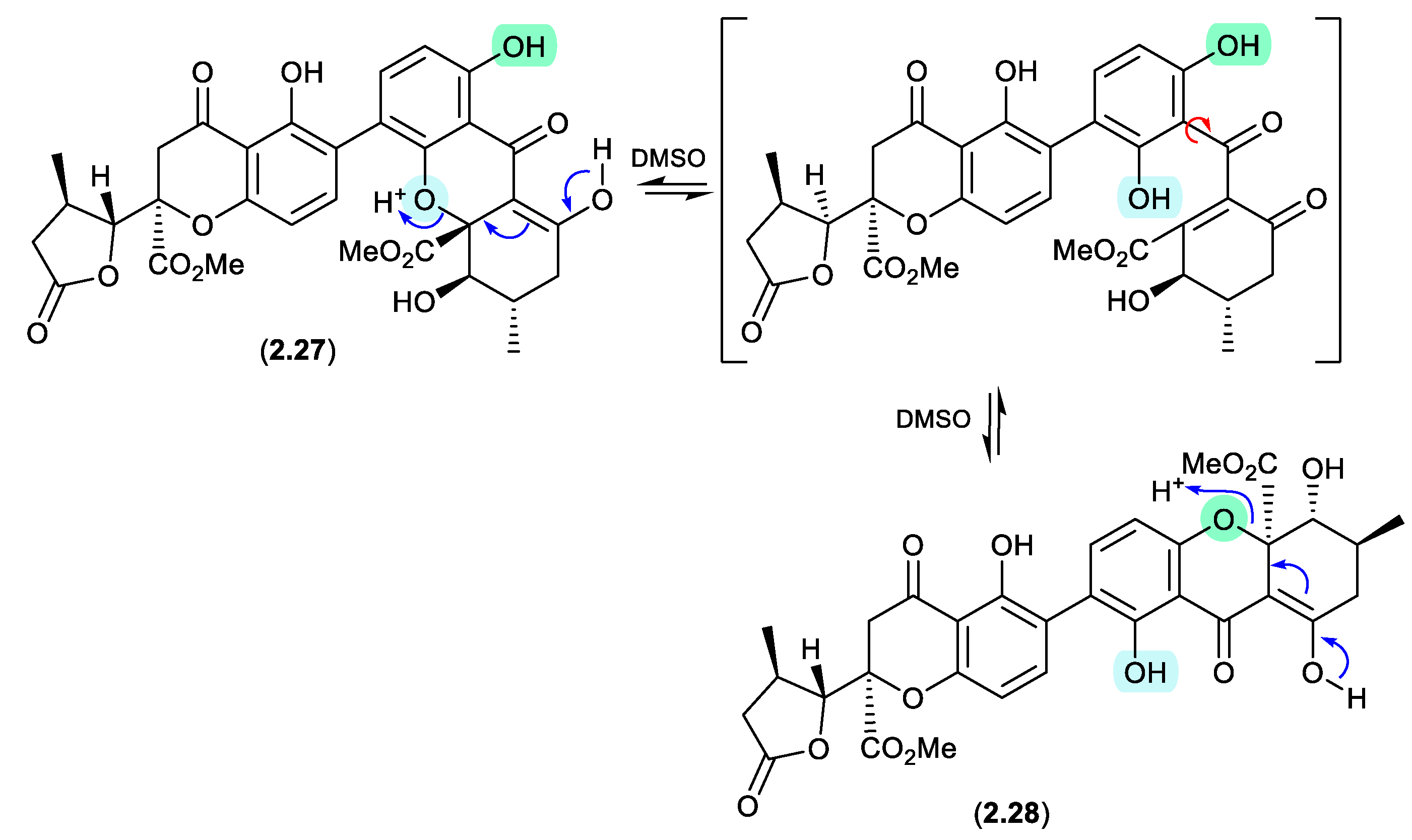

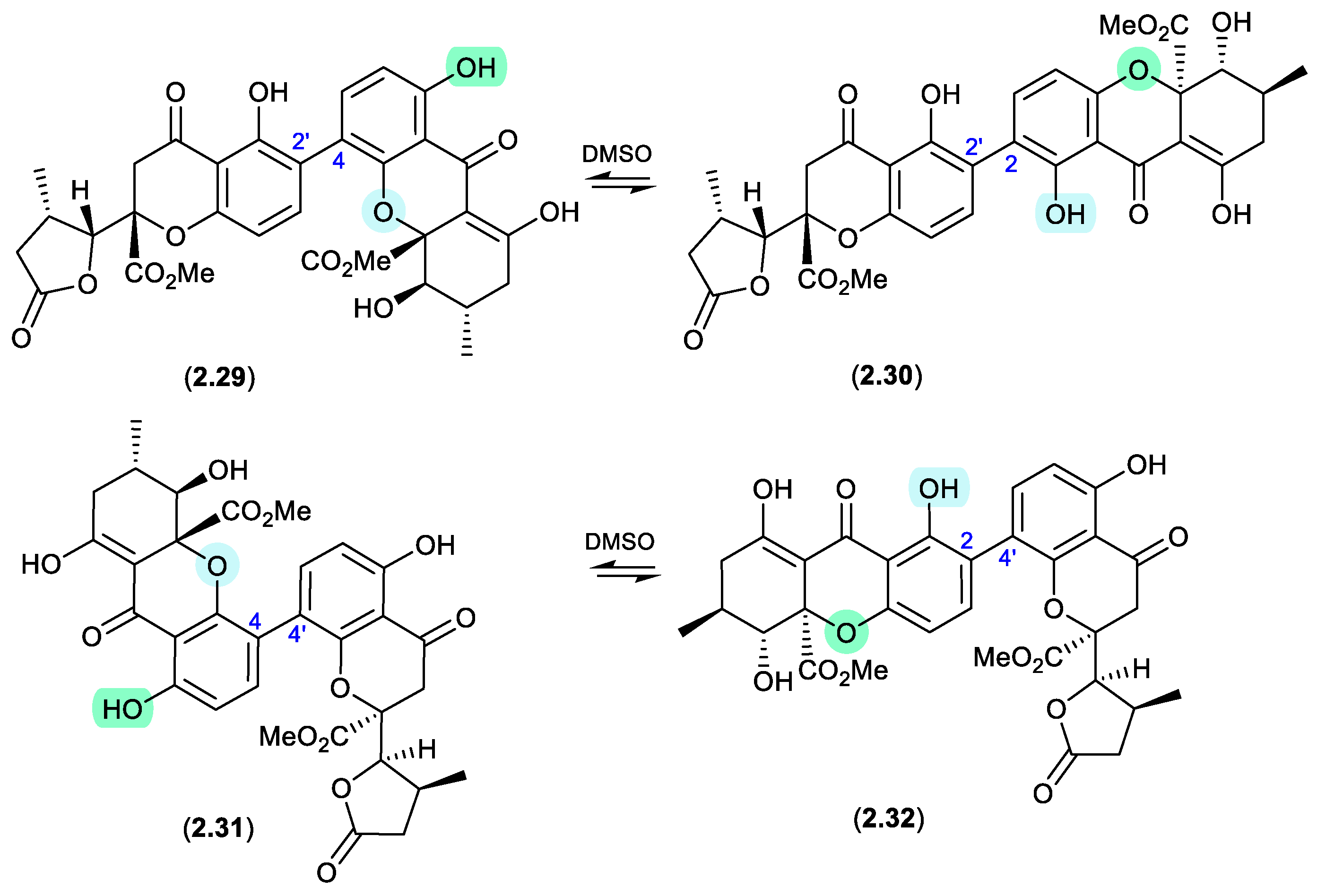

Aculeaxanthone B (

2.27), from the marine-derived fungus

Aspergillus aculeatinus WHUF0198, undergoes a retro-oxa-Michael equilibration in DMSO-

d6 to the regioisomer, chrysoaxanthone B (

2.28).[

19] As

2.28 was itself reported as a natural product from the sponge-derived

Penicillium chrysogenum HLS111,[

20] this raises an interesting question — “Is one regioisomer an artifact, and if so, which one?”

Figure 2.

1.8 versixanthones (Figure 2.1.9).

Figure 2.

1.8 versixanthones (Figure 2.1.9).

Similar DMSO mediated retro-oxa-Michael equilibrations were reported in 2015 between versixanthones A (

2.29) and D (

2.30), and versixanthones B (

2.31) and C (

2.32), which were isolated from the marine-derived fungus

Aspergillus versicolor HDN100.9.[

21]

Figure 2.

1.9 secalonic acid/parnafungins (Figure 2.1.10 and 2.1.11).

Figure 2.

1.9 secalonic acid/parnafungins (Figure 2.1.10 and 2.1.11).

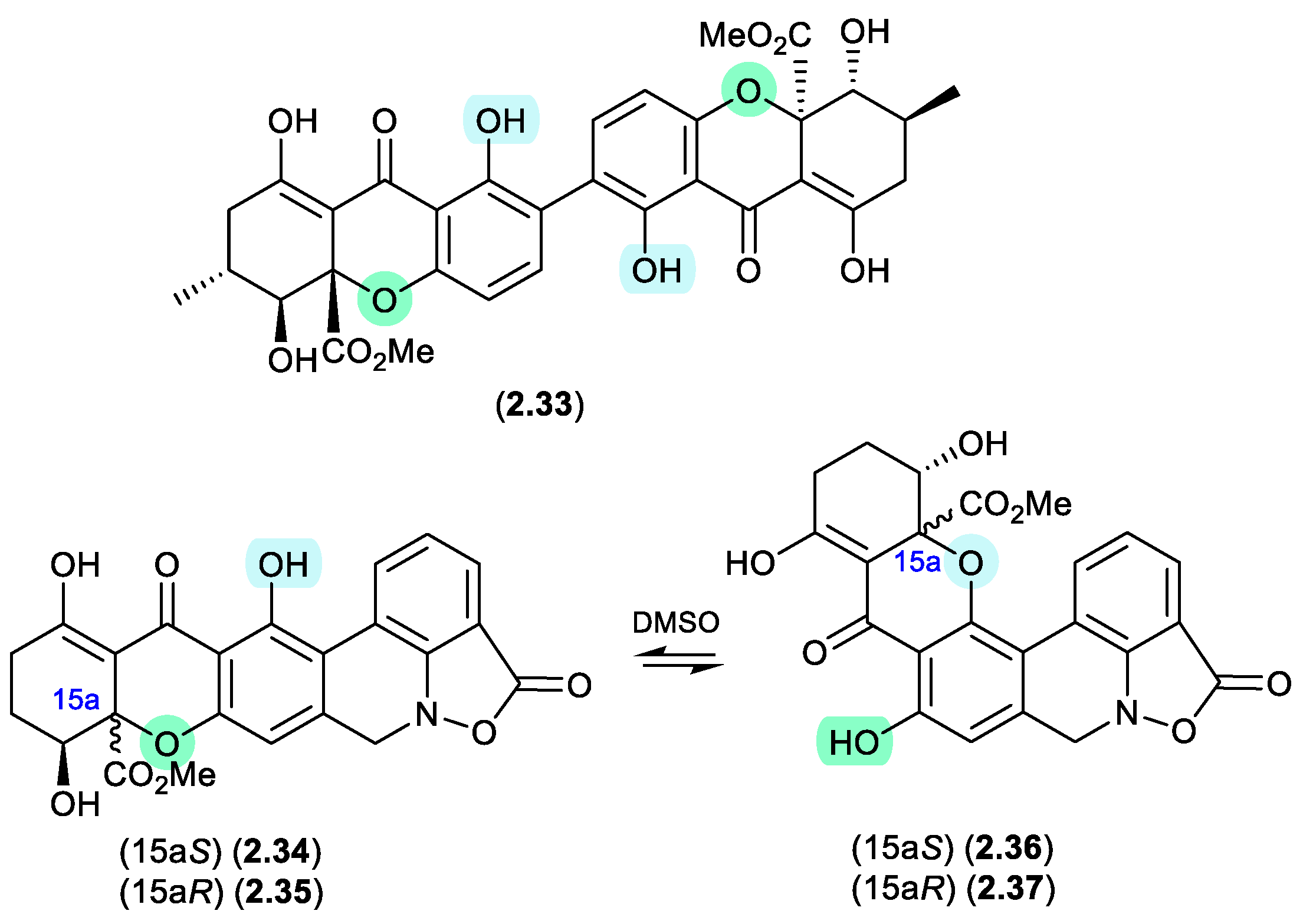

This solvent mediated intramolecular retro-oxa-Michael equilibration was further demonstrated in studies of secalonic acid A (

2.33) and its associated regioisomers,[

22,

23] as well as in the relationship between parnafungin A, which is a mixture of the C-15a epimers parnafungins A1 (

2.34) and A2 (

2.35), and parnafungin B, a mixture of the C-15a epimers parnafungins B1 (

2.36) and B2 (

2.37).[

24]

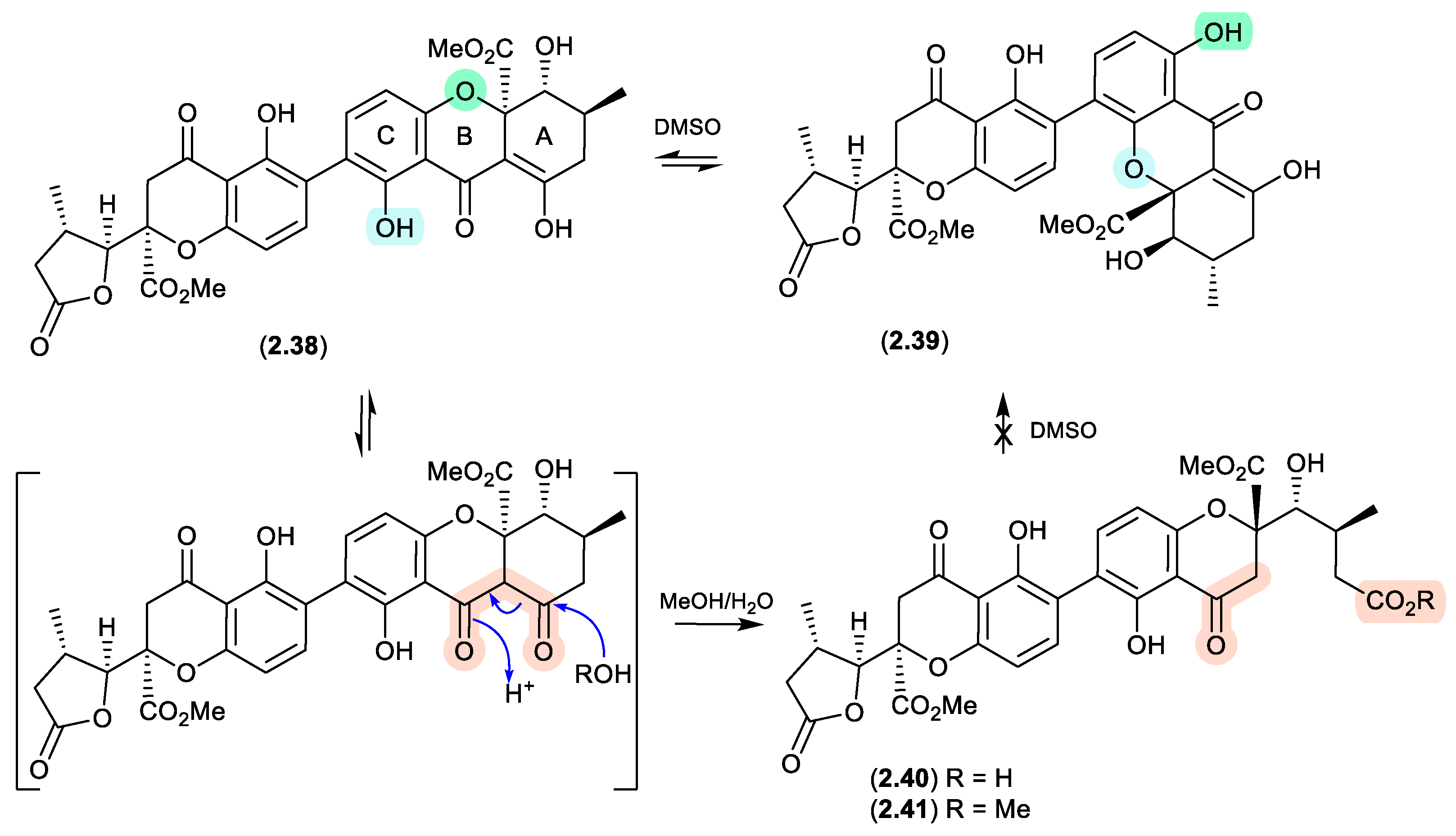

Of note, the chemical reactivity of the tetrahydroxanthone-chromanone core common across

2.33–

2.37 is not restricted to the intramolecular retro-oxa-Michael equilibrations outlined above. For example, while DMSO mediated an intra-molecular retro-oxa-Michael equilibration between chrysoxanthone E (

2.38) and G (

2.39), exposure of

2.38 to H

2O facilitated hydrolysis of ring A to chrysoxanthone O (

2.40), while addition of MeOH extended this to include the methanolysis product chrysoxanthone P (

2.41).[

25] Unsurprisingly, the opening of ring A removed the ability to undertake retro-oxa-Michael equilibration. With DMSO, MeOH and H

2O being common extraction, purification and handling solvents, the ease with which these r.t. transformations take place raises the likelihood that handling artifacts have been misidentified as natural products. It also challenges the veracity of bioactivity data and the ability to assign SAR, where analytes can transformation during bioassays (see Section 11).

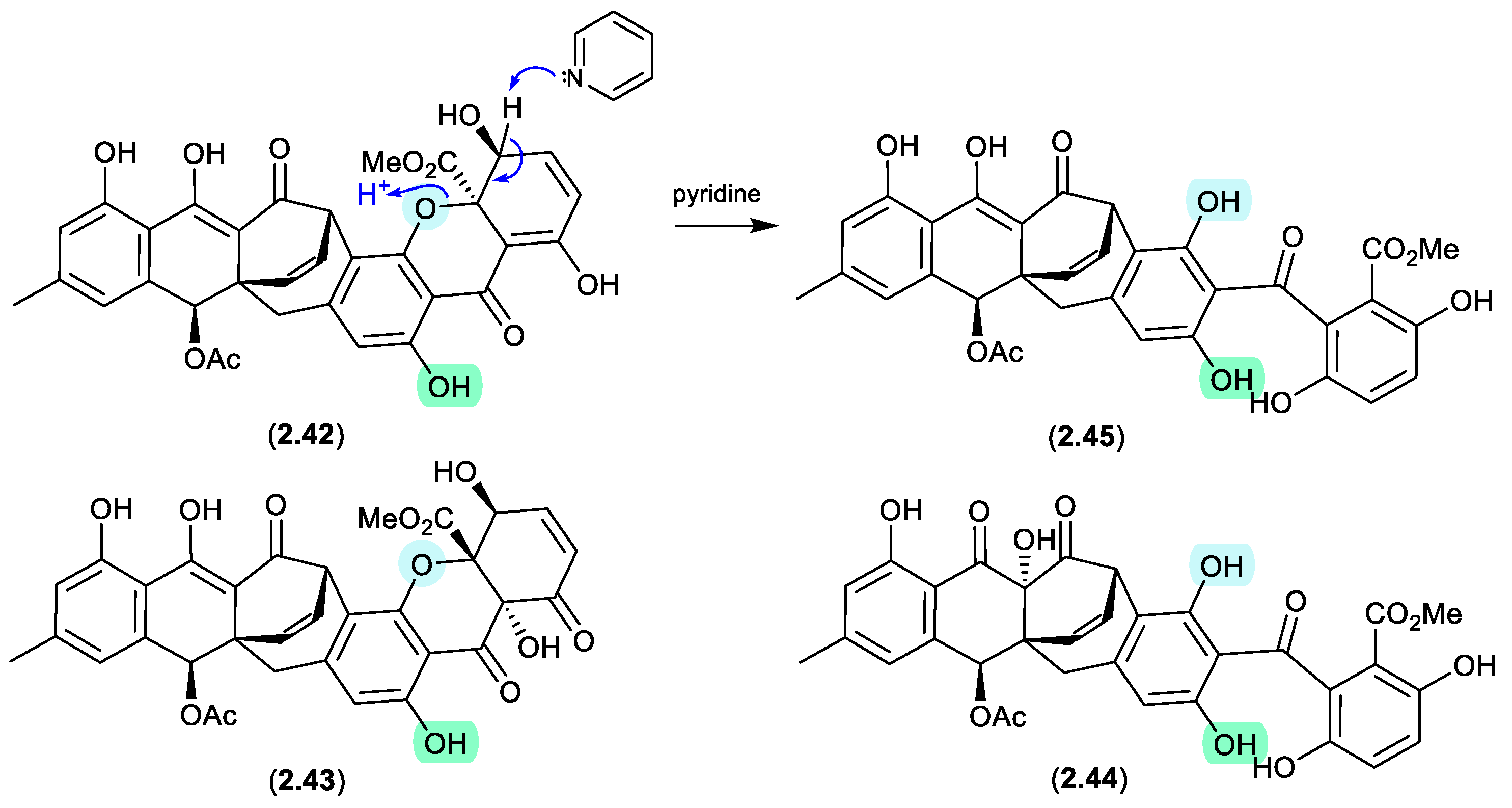

2.2. Pyridine

acremoxanthones/acremonidins (Figure 2.2.1)

An unidentified fungus of the order Hypocreales (MSX 17022) yielded two new xanthone-anthraquinone heterodimers, acremoxanthones C (

2.42) and D (

2.43), and the closely related known metabolites acremonidins C (

2.44) and A (

2.45).[

26] Interestingly, attempts at preparing Mosher esters revealed that

2.43 was unstable to pyridine. Indeed, when exposed to pyridine alone at r.t. for 4.5 h,

2.43 underwent complete conversion to

2.45. As noted above (

Section 2.1) such a transformation would be expected to occur under neutral conditions in DMSO.

2.3. Methanol

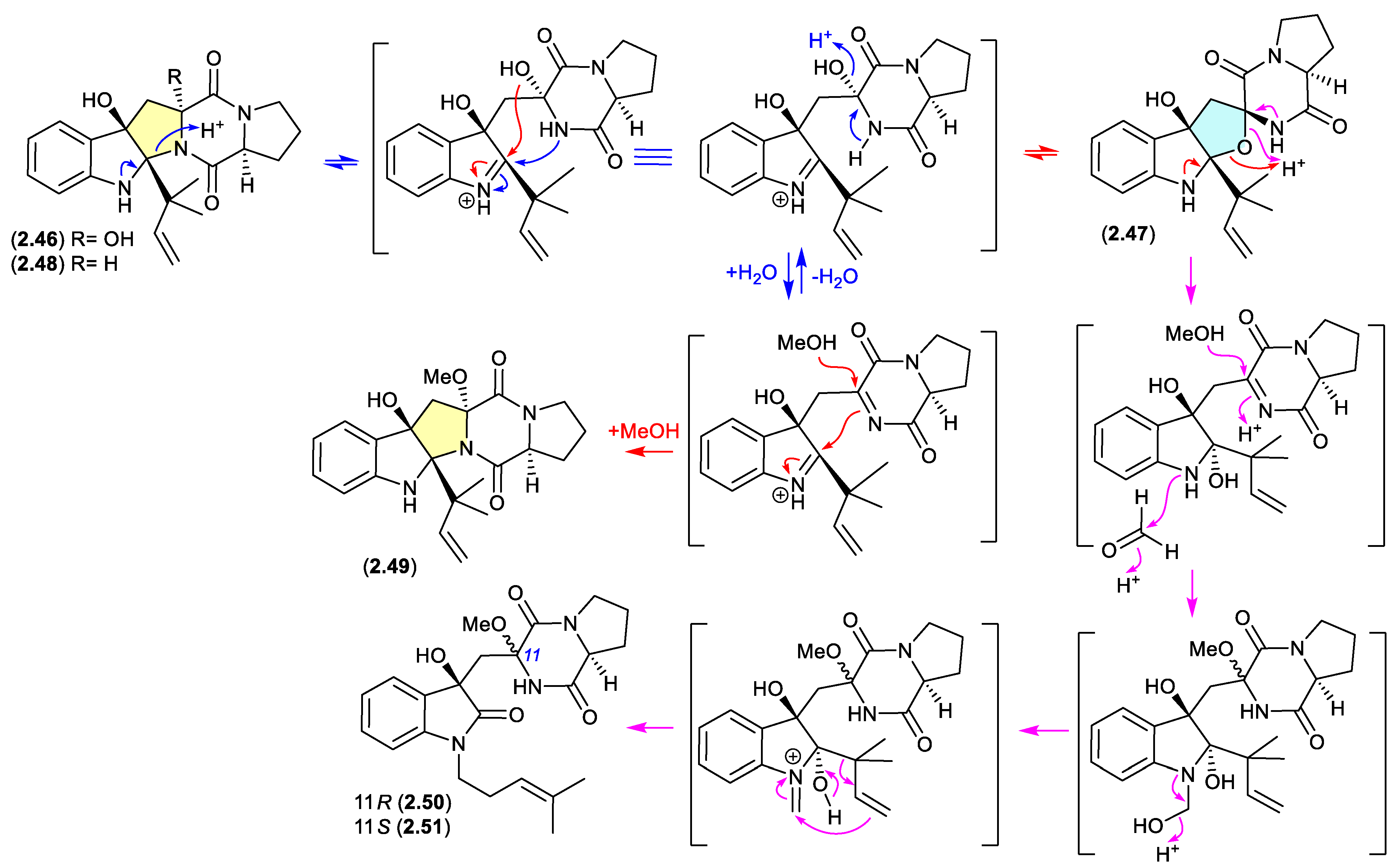

brevianamides (Figure 2.3.1 and 2.3.2)

The Lake Michigan deep-water sediment-derived fungus

Penicillium sp. 5-PBA-2 yielded two diketopiperazines, brevianamides E1 (

2.46) and E2 (

2.47), along with known analogues, including brevianamide E (

2.48).[

27] Of note,

2.46 and

2.47 rapidly equilibrated (1:9 ratio) in acidic HPLC solvents (MeCN/H

2O with either 0.1% formic acid or 0.1% TFA), while prolonged exposure of the equilibrating mixture to acidic MeOH (0.1% TFA) yielded the methyl ether

2.49, as well as the two rearranged products

2.50 and

2.51. It is proposed that the latter are formed by reaction with formaldehyde present as an impurity in commercial MeOH — confirmed by addition of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine to commercial MeOH and the detection of formaldehyde 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone.

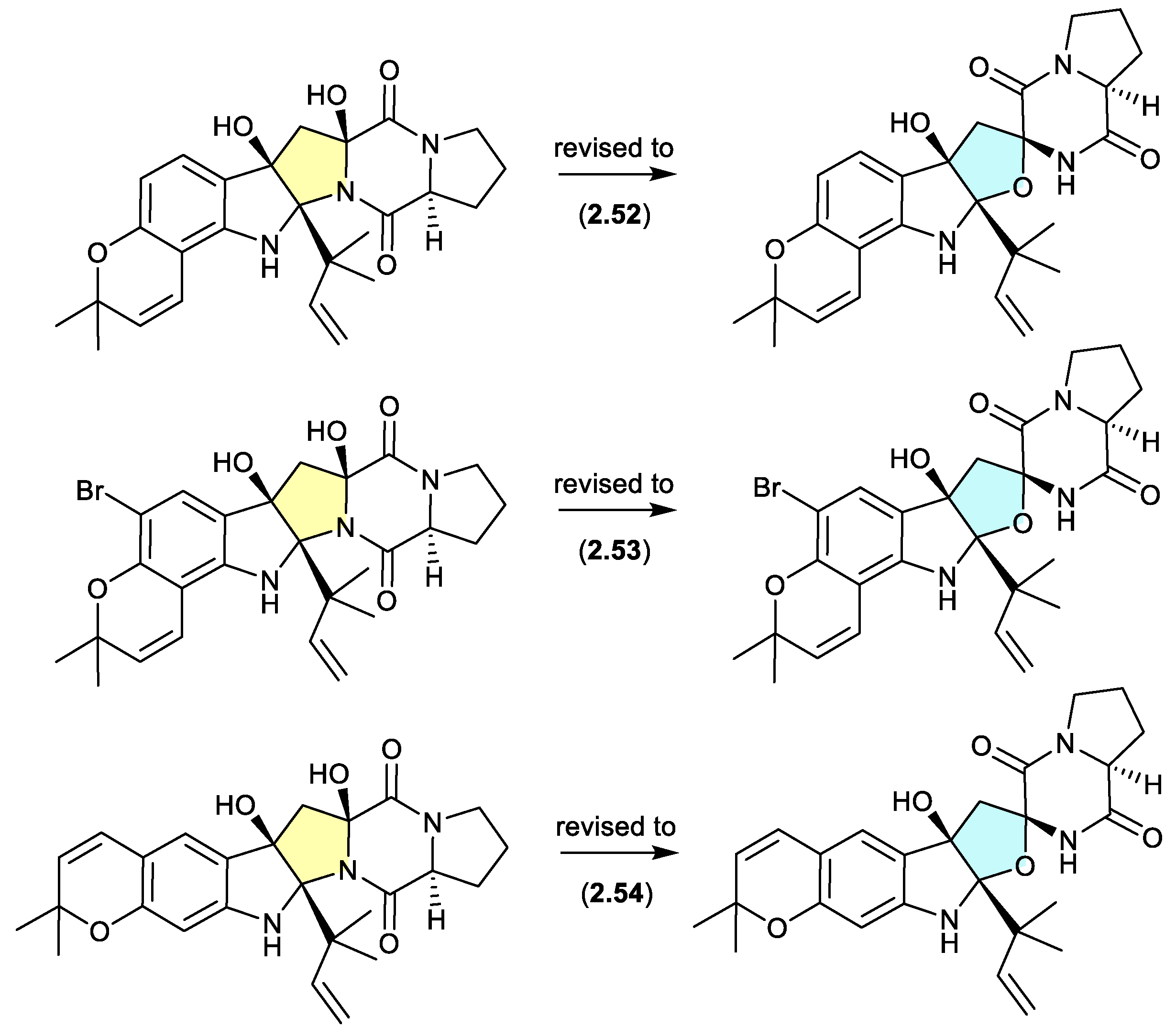

A comparison of experimental and calculated ECD spectra (with

2.47) led to structure revisions for known diketopiperazines featuring a rare 11-oxy moiety, including notoamides K (

2.52) and P (

2.53), and asperversiamide L (

2.54).[

27]

Figure 2.

3.2. talaronins (Figure 2.3.3).

Figure 2.

3.2. talaronins (Figure 2.3.3).

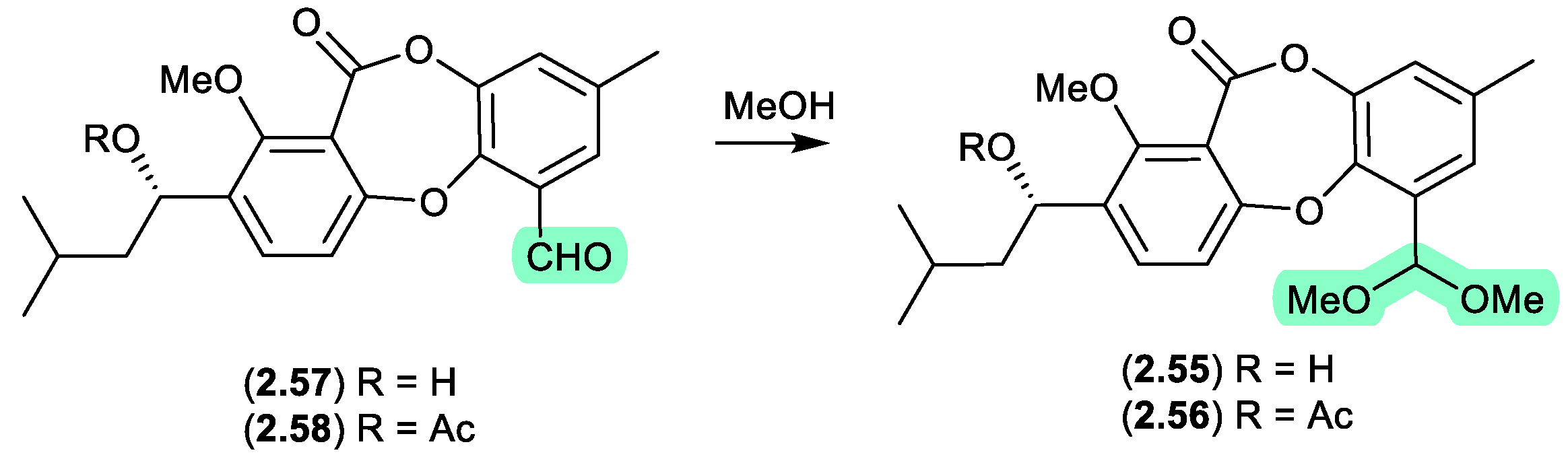

The Chinese mangrove derived fungus

Talaromyces sp. WHUF0362 yielded a range of polyketides, including the new depsidone dimethylacetals, talaronins A (

2.55) and B (

2.56), the new depsidone benzaldehyde talaronin D (

2.57), and the known purpactin C′ (

2.58).[

28] Although the dimethylacetals

2.55 and

2.56 are designated as natural products, the extensive use of MeOH eluant across Sephadex LH-20 and HPLC chromatography makes it far more probable that the dimethylacetals are methanolysis artifacts of

2.57 and

2.58, respectively. Other examples of natural product aldehydes transforming in MeOH to dimethyl acetals include the colletotrichalactones from the Korean leaf-derived endophytic fungus

Colletotrichum sp. JS-0361,[

29] cladosporisteroids from the Chinese marine sponge-derived fungus

Cladosporium sp. SCSIO41007,[

30] and the talaromycins from the South China Sea gorgonian-derived fungus

Talaromyces sp. (see

Section 5.3).[

31]

Figure 2.

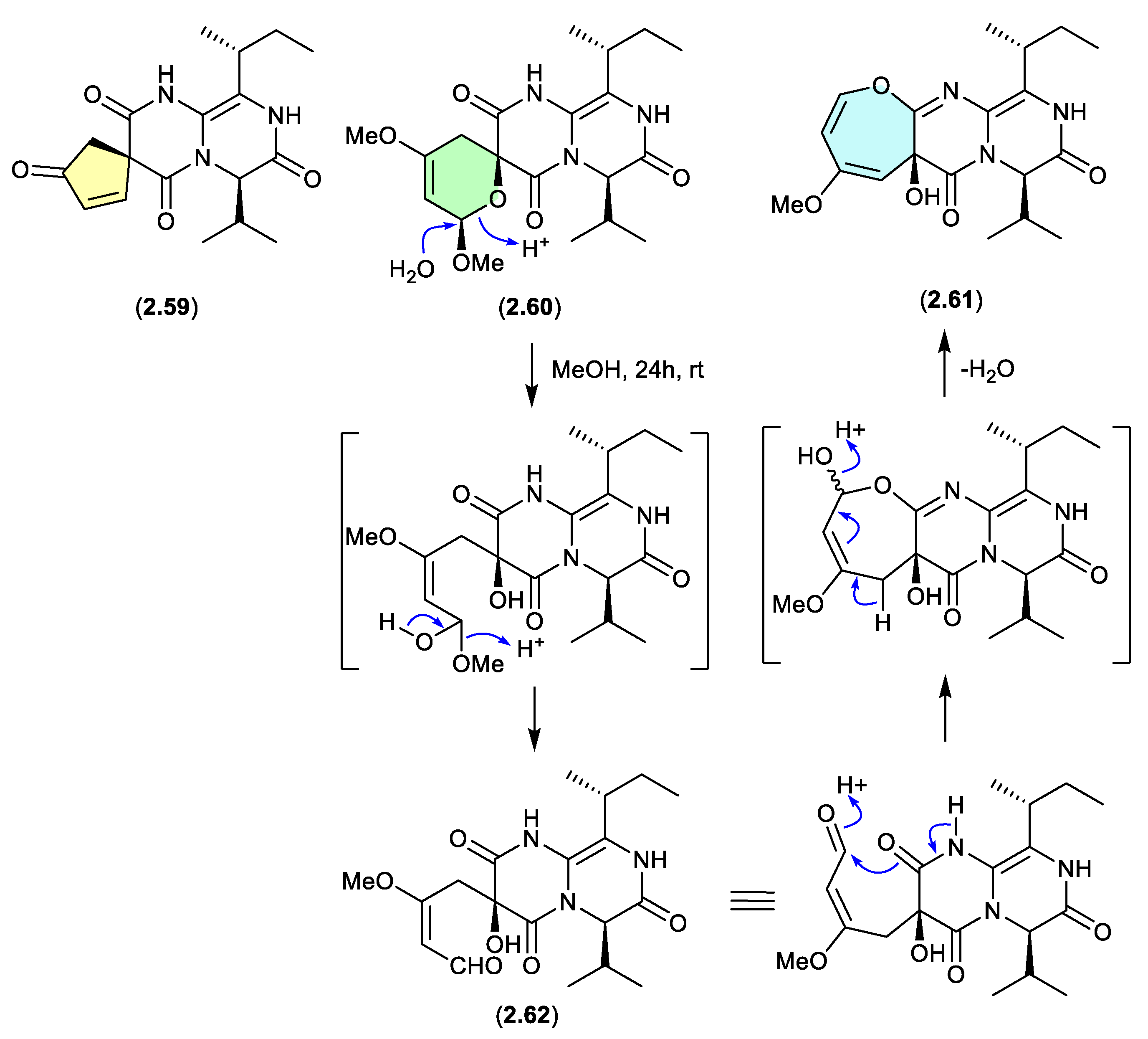

3.3 pyrasplorins (Figure 2.3.4).

Figure 2.

3.3 pyrasplorins (Figure 2.3.4).

The mangrove-derived fungus

Aspergillus versicolor yielded an array of pyrazinopyrimidine alkaloids, pyrasplorins A–C (

2.59–

2.61).[

32] On handling in MeOH,

2.60 underwent ring opening to the artifact

2.62; however, it’s likely that the ring opening was mediated by H

2O present in the MeOH). Although the authors make no mention of a plausible dehydration pathway from the artifact

2.62 to

2.61, it raises the prospect that the latter is also an artifact.

Figure 2.

3.4. penicipyridones (Figure 2.3.5).

Figure 2.

3.4. penicipyridones (Figure 2.3.5).

The marine mangrove plant-derived fungus

Penicillium oxalicum QDU1 yielded 11 new pyridine alkaloids, exemplified by penicipyridones A–C (

2.63–

2.65).[

33] Indicative of their chemical reactivity, over 3 d acidic solutions of

2.63 (MeCN/H

2O or MeOH/H

2O, with 0.1% formic acid) effected a transformation to

2.64, with trace amounts of

2.65. After 14 d, acidic MeOH solutions of any one of

2.63–

2.65 equilibrated to an 8:7:1 mixture. This reactivity reveals a biomimetic path to adding unnatural nucleophiles at C-4.

Figure 2.

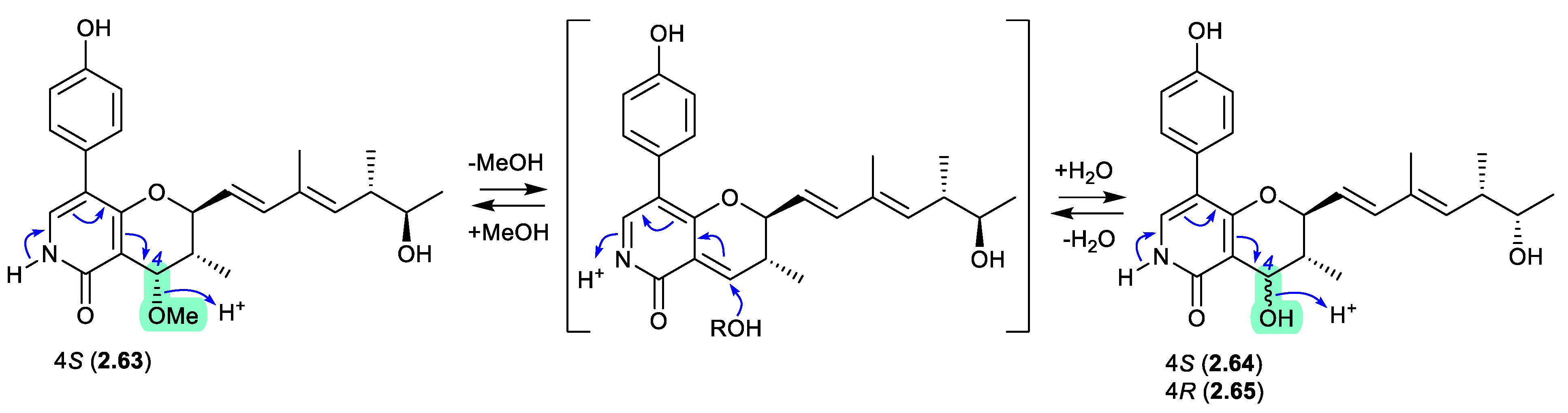

3.5. variacins (Figure 2.3.6).

Figure 2.

3.5. variacins (Figure 2.3.6).

The benzopentathiepin varacin (

2.66), isolated from a Fijian sample of the marine ascidian

Lissoclinum vareau, exhibited potent cytotoxic properties against human colon carcinoma cells (HCT 116).[

34] Subsequently,

2.66 was reported along with three analogues, varacins A–C (

2.67–

2.69), from a Sea of Japan ascidian

Polycitor sp.[

35] Interestingly, solutions of

2.66 or

2.67 (in MeOH, CH

2Cl

2 or pyridine) equilibrate to mixtures of

2.66,

2.67 and S

8 (

2.70).

Figure 2.

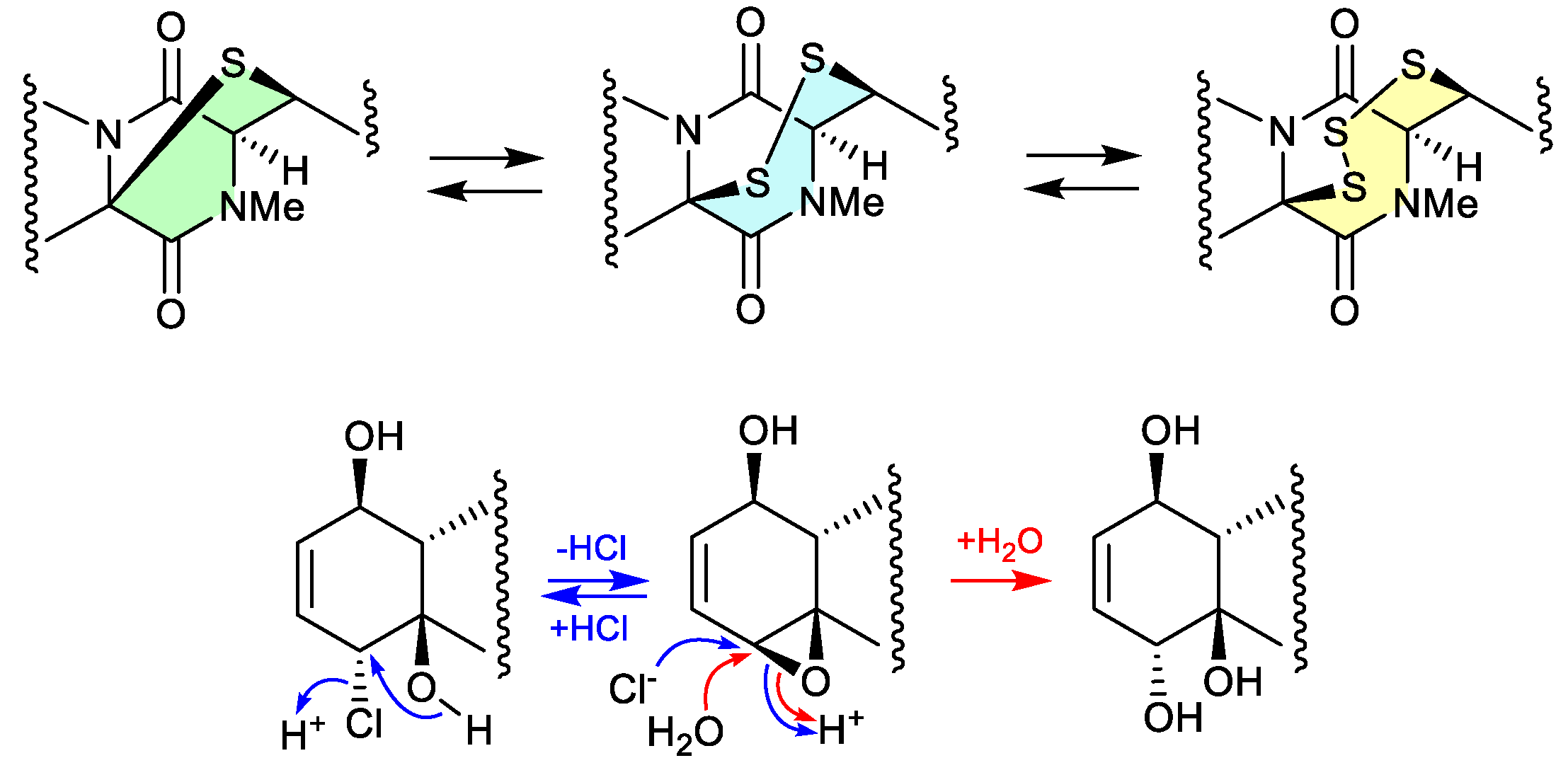

3.6. epithiodiketopiperazines (Figure 2.3.7 and 2.3.8).

Figure 2.

3.6. epithiodiketopiperazines (Figure 2.3.7 and 2.3.8).

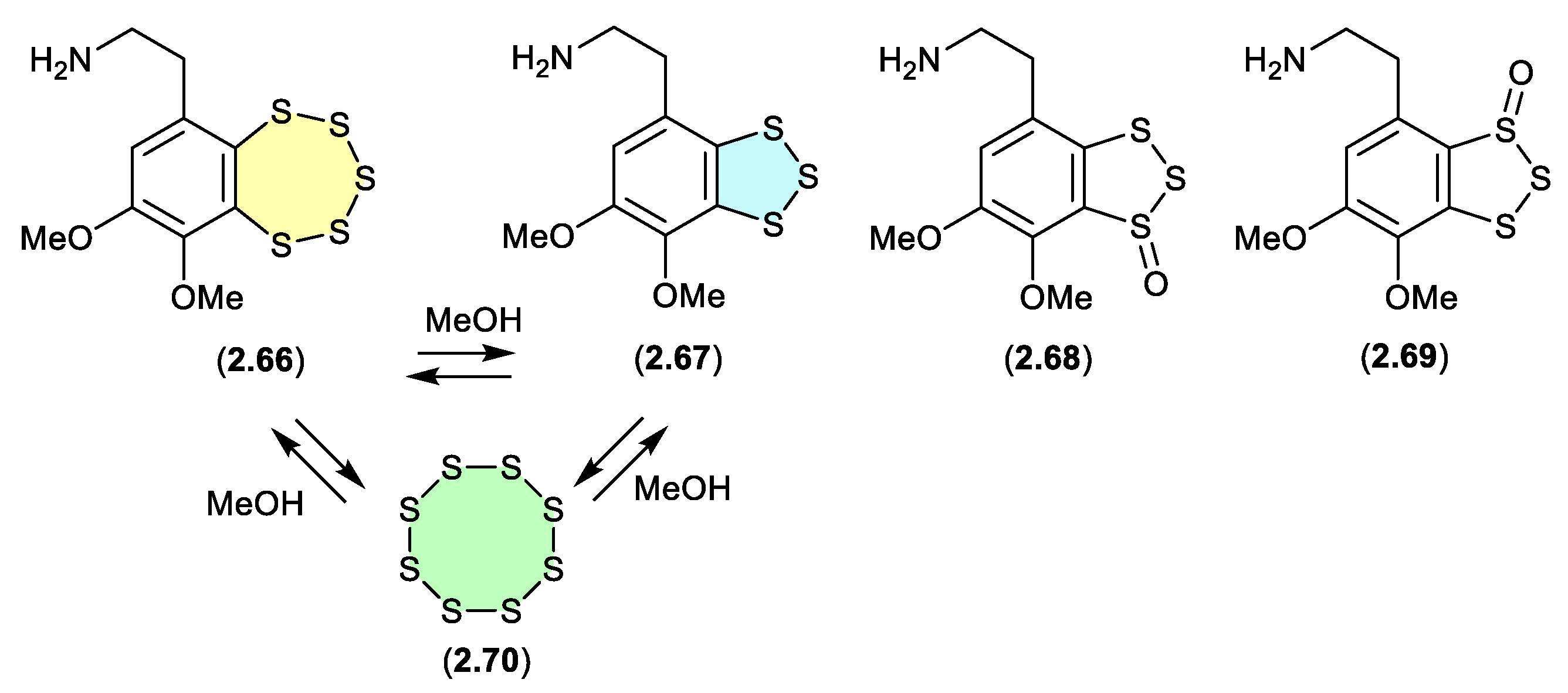

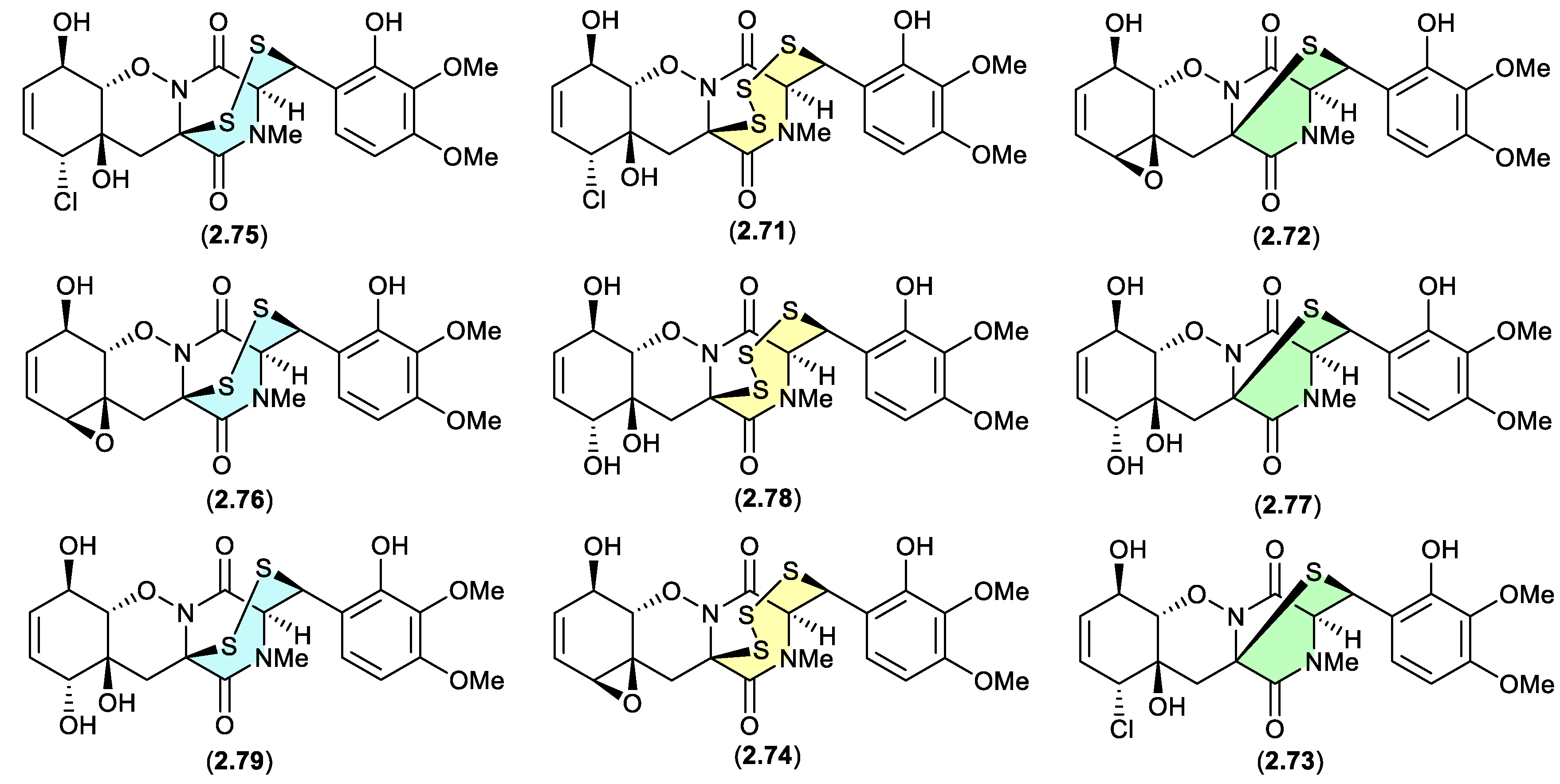

The study of a fungal strain

Penicillium sp. YE isolated from a Florida collection of a coral

Pseudodiploria strigosa infected with coral black band disease, yielded 4 new epithiodiketopiperazines, penigainamides A (

2.71), B (

2.72), C (

2.73) and D (

2.74), and five known analogues, adametizine A (

2.75), FA2097 (

2.76), outovirins A (

2.77) and C (

2.78) and pretrichodermamide C (

2.79).[

36] Some of these proved unstable to handling in a range of solvents, leading to either contraction/expansion of the di, tri and tetra thioether ring, and/or transformation between chlorohydrin and epoxide moieties. For example, exposure of (i)

2.75 to MeOH (1 wk) lead to partial conversion to

2.71–

2.73 and

2.76, and H

2O (1 wk) to

2.72,

2.76,

2.78 and

2.79; (ii)

2.71 to CDCl

3 (1 h) lead to partial conversion to

2.74; (iii)

2.72 to methanol-

d4 (30 min) to

2.73; and (iv)

2.78 to H

2O (1 wk) to

2.77, to acetone-

d6 (30 min) to

2.74, and to artificial sea water culture media (PDB) to

2.75.

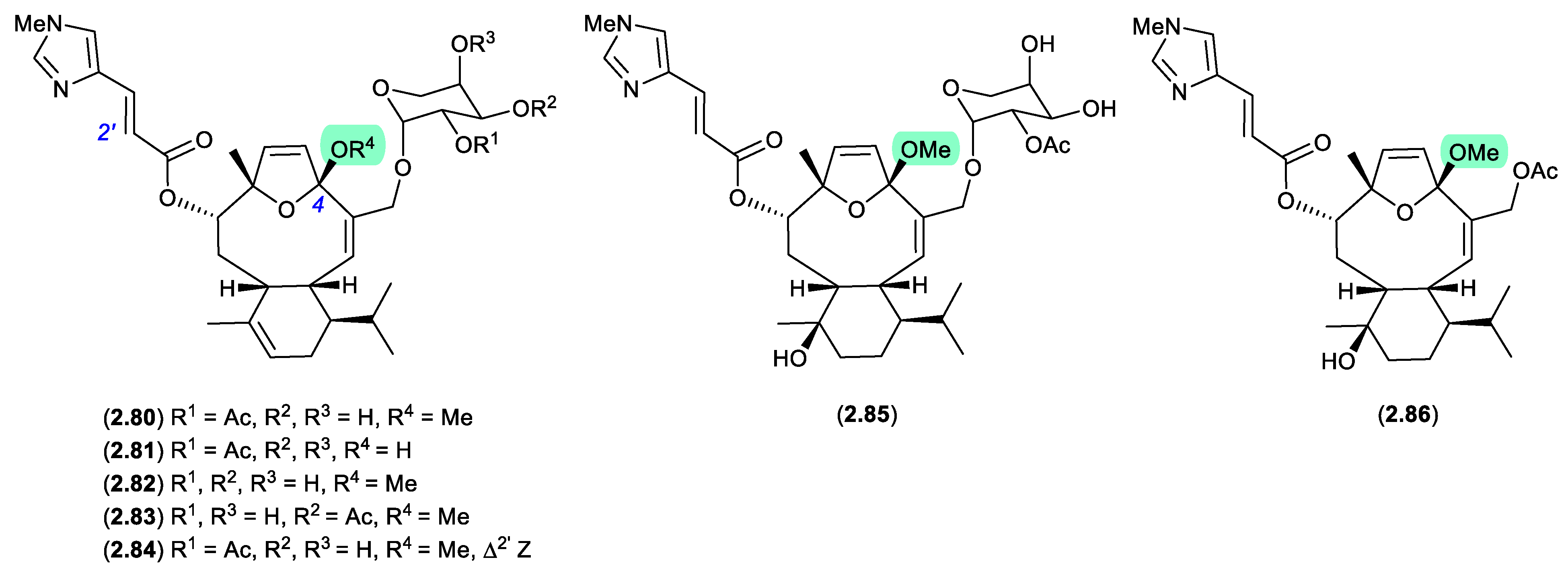

eleutherobins/caribaeoranes (Figure 2.3.9)

Eleutherobin (

2.80), first reported in 1997 by Fenical et al from a Western Australian sample of soft coral

Elutherobia sp., exhibited exceptionally activity as a microtubule-stabilising antimitotic agent that was comparable to paclitaxel.[

37] Subsequently, Andersen et al reported the re-isolation of

2.80 in 2000, along with the six new analogues, desmethyleleutherobin (

2.81), desacetyleleutherobin (

2.82), isoeleutherobin A (

2.83),

Z-eleutherobin (

2.84), caribaeoside (

2.85) and caribaeolin (

2.86), from southern Caribbean samples of the octocoral

Erythropodium caribaeorum.[

38] In both studies, fractionation involved the use of silica gel (MeOH) chromatography, raising the possibility that the 4-methylacetals were handling artifacts. In a follow-up 2001 report, Andersen et al described alternate solvent extractions of fresh collections of

E. caribaeorum, with MeOH extraction returning the previously reported 4-methylacetals, and EtOH extraction returning the corresponding 4-ethylketals — revealing the true natural products in this class to be 4-hemiketals.[

39]

2.4. Acetone

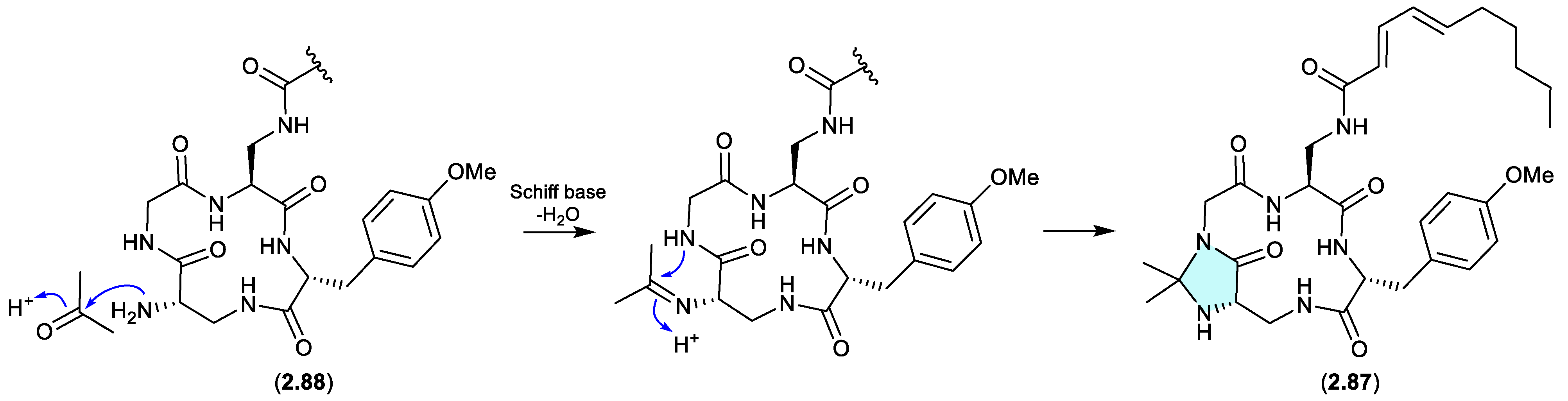

kutzneridines (Figure 2.4.1)

Genomic analysis of the Panama soil-derived actinobacterium

Kutzneria sp. CA-103260 revealed a biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) encoding for a putative lipopeptide — with heterologous expression in

Streptomyces coelicolor M1152 yielding kutzneridine A (

2.87), bearing an exotic

N,N-acetonide moiety.[

40] However, as acetone was used in the extraction process, it was determined that

2.87 was an artifact of a cryptic natural product

2.88 (detected but not isolated/characterised – see Section 10).

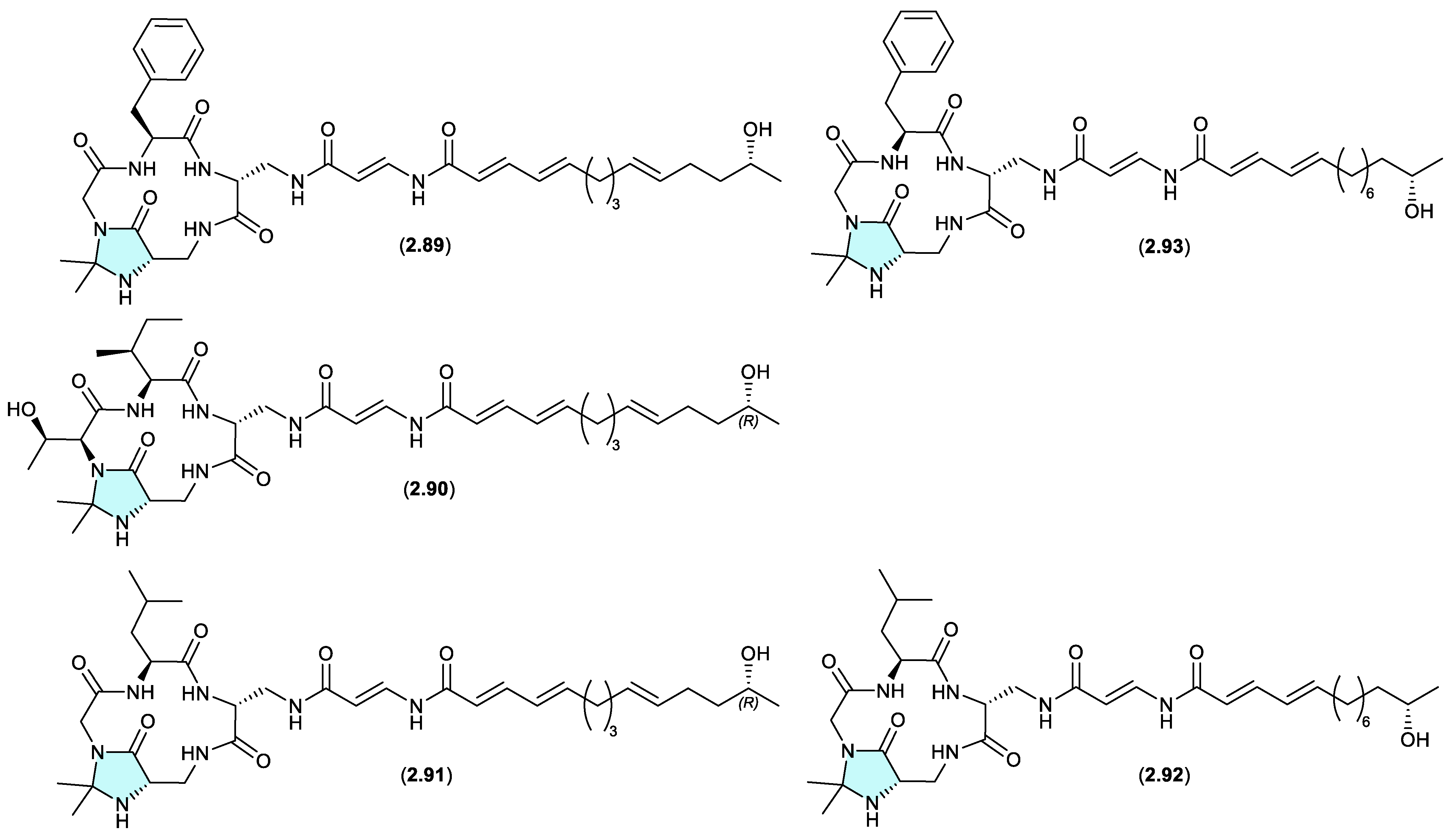

enamidonins/ K97-0239A and B (Figure 2.4.2)

The

N,

N-acetonide containing lipopeptide enamidonin (

2.89) was first reported in 1995 from the soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. 91-75,[

41] and later in 2018 along with two new analogues, enamidonins B (

2.90) and C (

2.91) from a Korean soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. KCB14A132.[

42] Likewise, the Japanese soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. K97-0239 yielded the

N,

N-acetonide lipopeptides K97-0239A (

2.92) and K97-0239AB (

2.93).[

43] As all of the

N,N-acetonides

2.89–

2.93 were recovered by acetone extraction from their respective fermentations, it is likely all are handling artifacts.

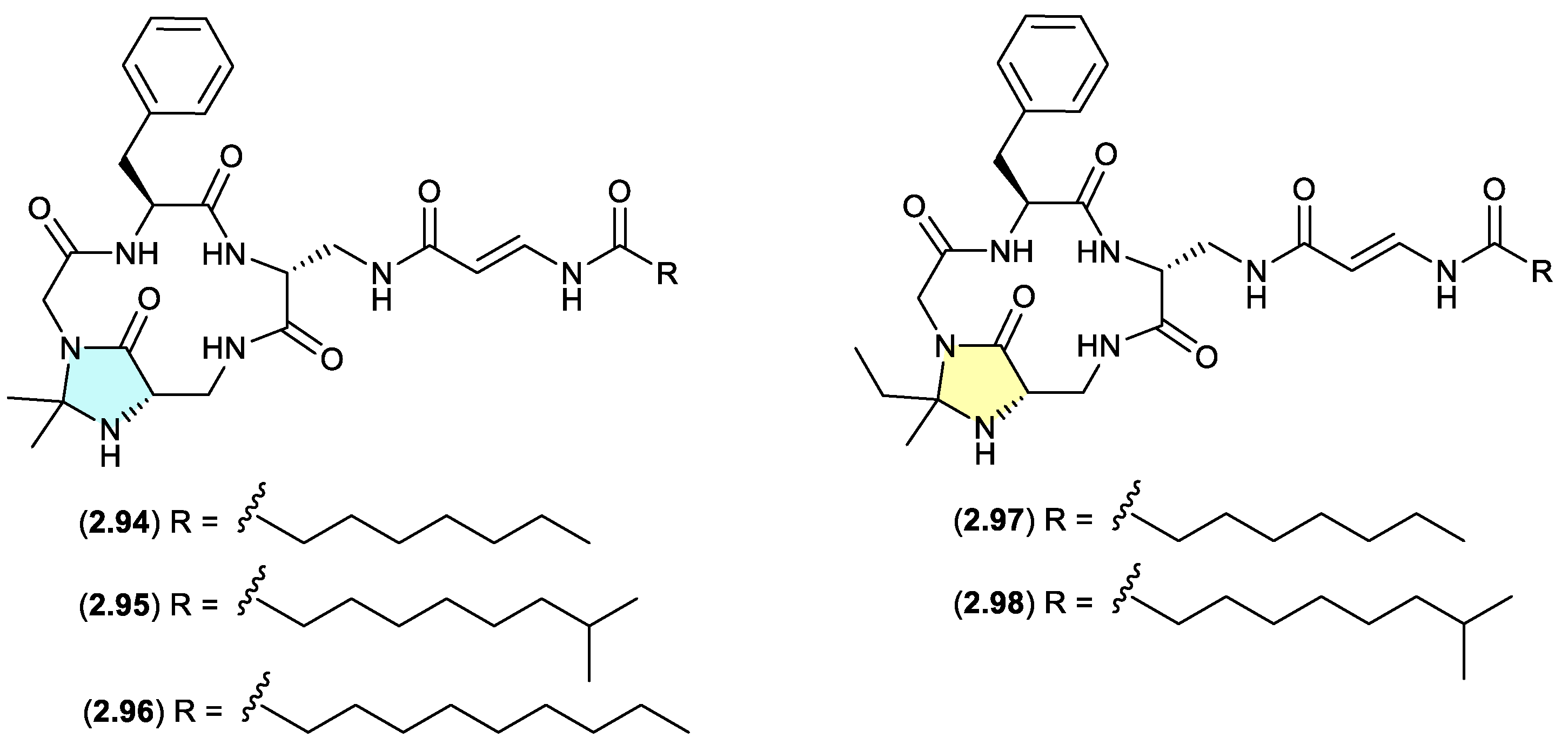

autucedines (Figure 2.4.3)

Genome mining of the deep-sea derived

Streptomyces olivaceus SCSIO T05 led to the discovery of five new enamidonin (

2.89) related lipopeptides.[

44] Fermentations extracted with acetone produced three

N,

N-acetonide adducts autucedines A (

2.94), D (

2.95) and E (

2.96), while extraction with 2-butanone produced the analogous

N,

N-ethyl,methyl adducts autucedines B (

2.97) and C (

2.98). This study has taken advantage of this handling artifact reaction to produce new analogues.

madurastatins (Figure 2.4.4)

The marine sponge-derived

Actinomadura sp. WMMA-1423 yielded two new

N,N-acetal siderophores, madurastatins D1 (

2.99) and D2 (

2.100), along with madurastatin C1 (

2.101).[

45] As the fermentation was extracted with acetone, its likely

2.101 reacts with acetone to yield the

N,N-acetonide artifact

2.100, and with acetaldehyde — a common contaminant in commercial (especially recycled) acetone — to yield the artifact

2.99. Presumably

N-methylation diminishes chemical reactivity, which is why on this occasion the precursor

2.101 survives extraction — unlike the case with

2.89–

2.98.

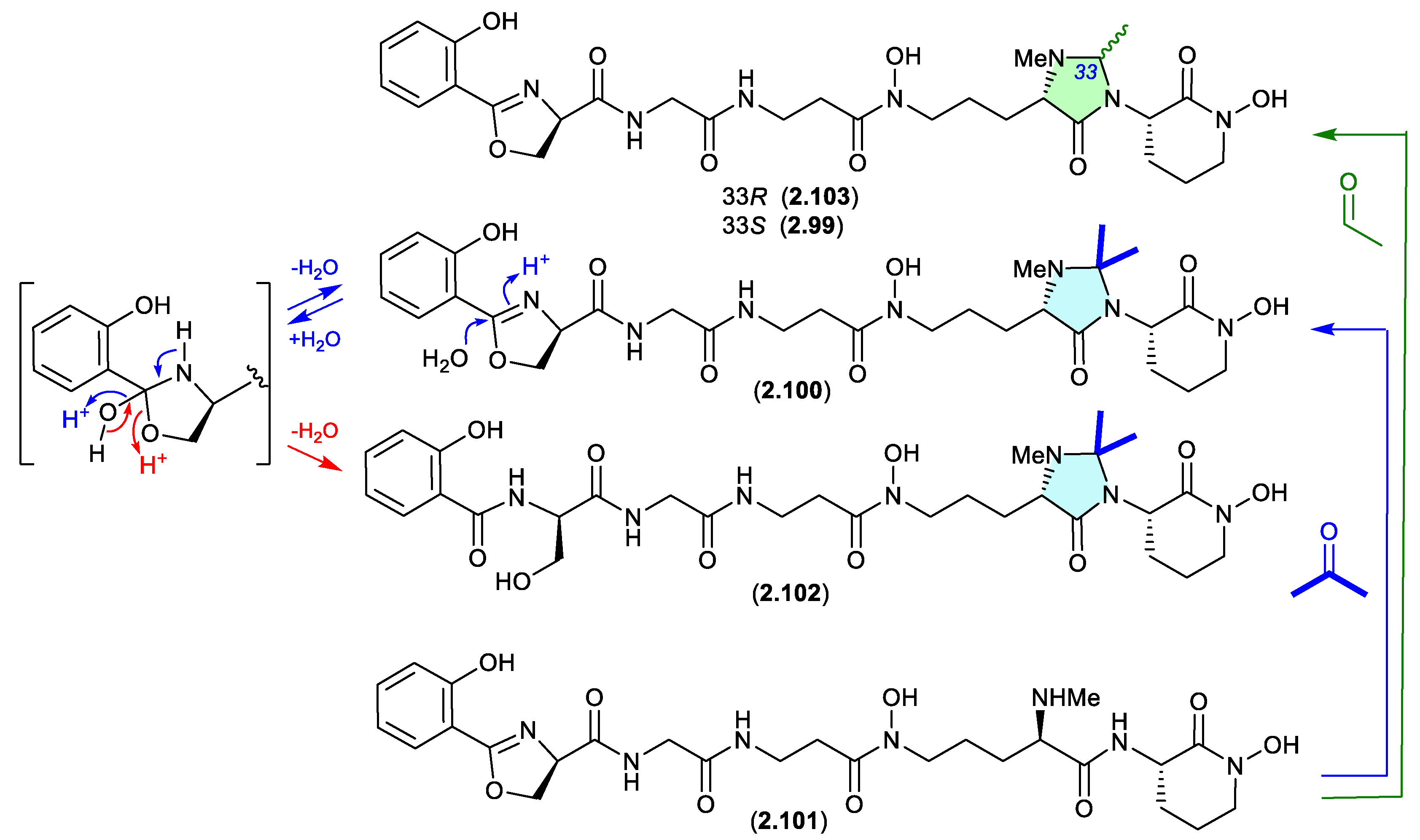

A 2024 study of the acetone extracts of a South African plant rhizosphere-derived

Actinomadura sp. CA-135719, identified madurastatins H2 (

2.102) and 33-

epi-D (

2.103) and reassigned absolute configurations across

2.99–

2.103.[

46] Significantly, these authors concluded that the madurastatins

2.99,

2.100,

2.102 and

2.103 are in all probability acetone handling artifacts. Although there could be some contribution from low levels of endogenous aldehydes. Of note,

2.102 is also likely an acid-mediated hydrolysis analogue (artifact) of

2.100 where the oxazoline ring is opened to a serine residue (see

Section 4.2, serratiochelin).

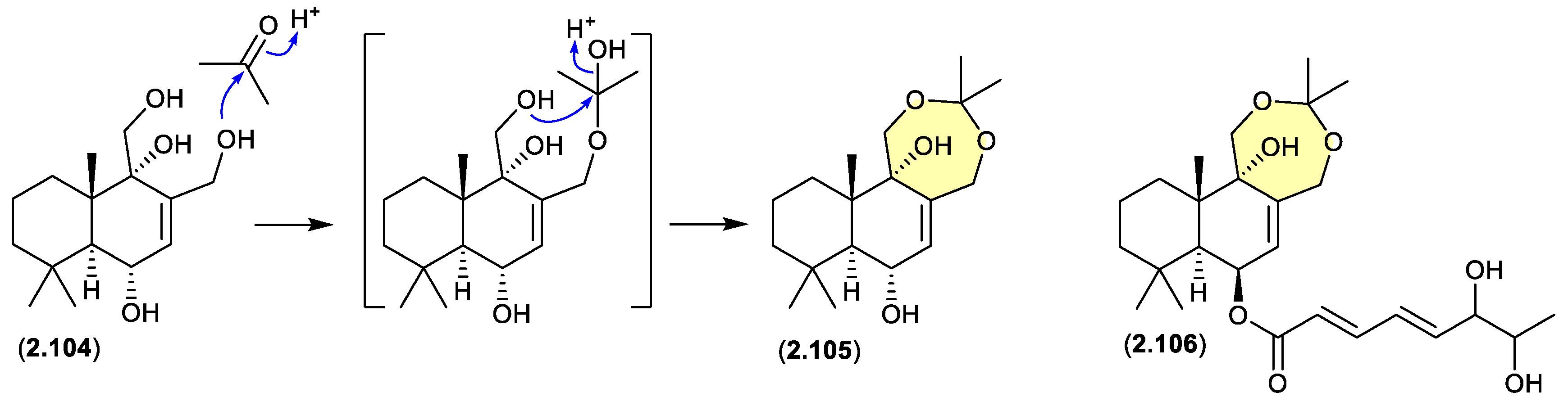

drimanes (Figure 2.4.5)

The Okhotsk Sea sediment-derived fungus

Aspergillus ustus KMM 4664 yielded a range of metabolites including the known drimane 12-hydroxyalbrassitriol (

2.104) and the new acetonides

2.105 and

2.106.[

47] As the fungal fermentation was extracted with acetone (and chromatographed on silica gel) the acetonides are likely acetone artifacts.

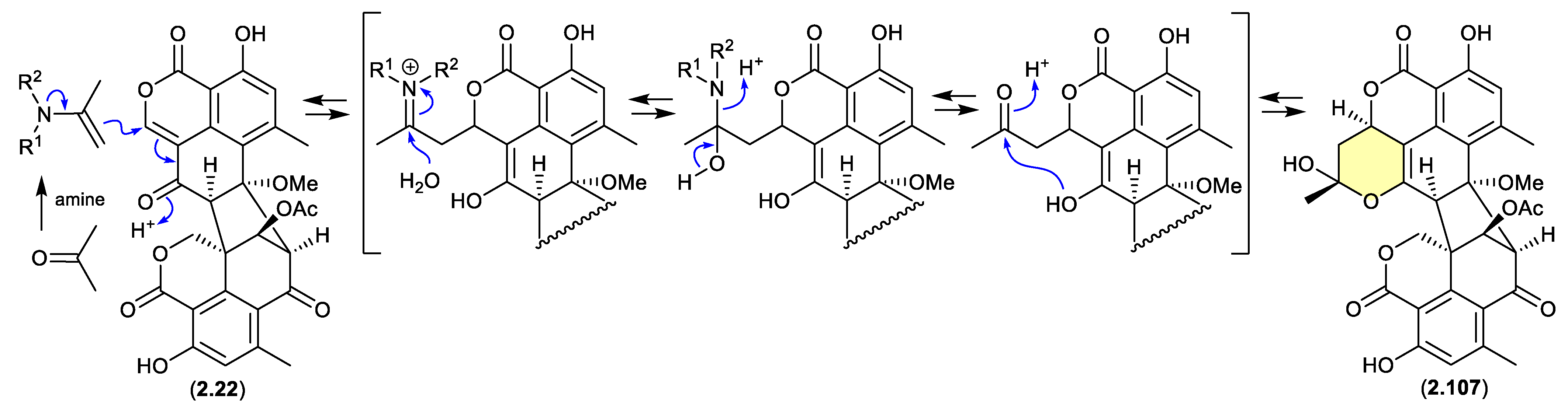

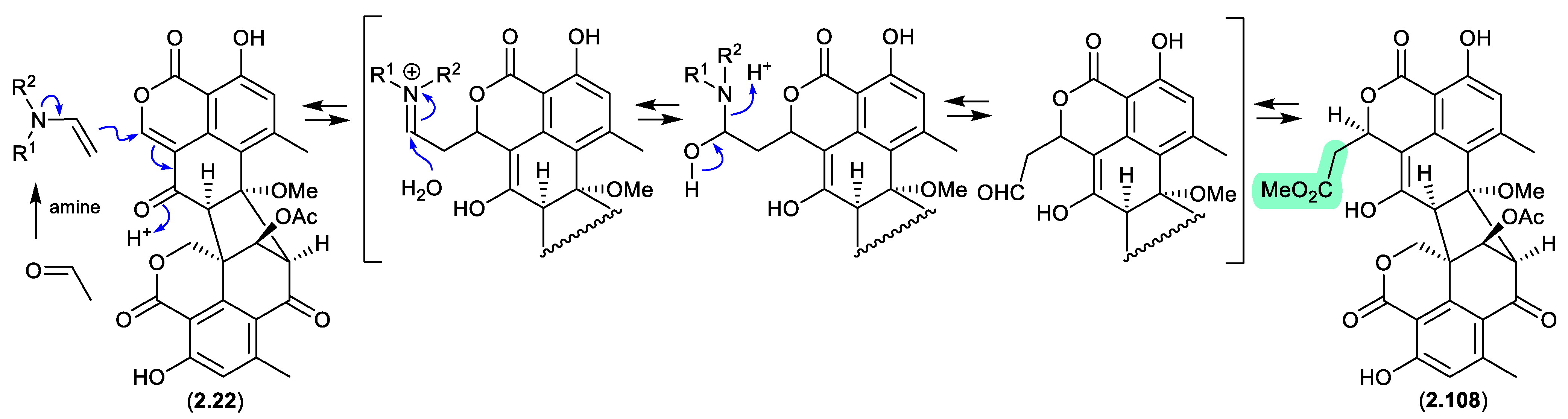

duclauxin/verruculosins (Figure 2.4.6–2.4.7)

A 2024 report by Rivera-Chávez et al on the chemical reactivity of the fungal natural product duclauxin (

2.22) (see

Section 4.3) established that exposure to acetone led to the formation of verruculosin A (

2.107).[

48] First reported from the acetone extract of the South China Sea soft coral-derived fungus

Talaromyces verruculosus along with verruculosin B (

2.108),

2.107 was originally designated as the first duclauxin

-like natural product to possess an octacyclic skeleton.[

49] Unlike the acetonide adducts described above (e.g. enamidonins, madurastatins), Rivera-Chávez et al proposed that the transformation of

2.22 to

2.107 proceeds via an enamine activated adduct of acetone (with a biogenetic amine present in the acetone extract). This hypothesis was confirmed by transformation of

2.22 to

2.107 in acetone supplemented with morpholine.

Building on this enamine-mediated mechanism, it’s reasonable to propose a comparable transformation utilising acetaldehyde, a known contaminant in commercial acetone (see

Section 2.4, madurastatins), followed by oxidation and methylation during silica gel (CH

2Cl

2/MeOH) chromatography (see

Section 4.3), would see verruculosin B (

2.108) also designated as an artifact of duclauxin (

2.22).

2.5. Acetonitrile

talcarpones (Figure 2.5.1)

The Australian soil-derived fungus

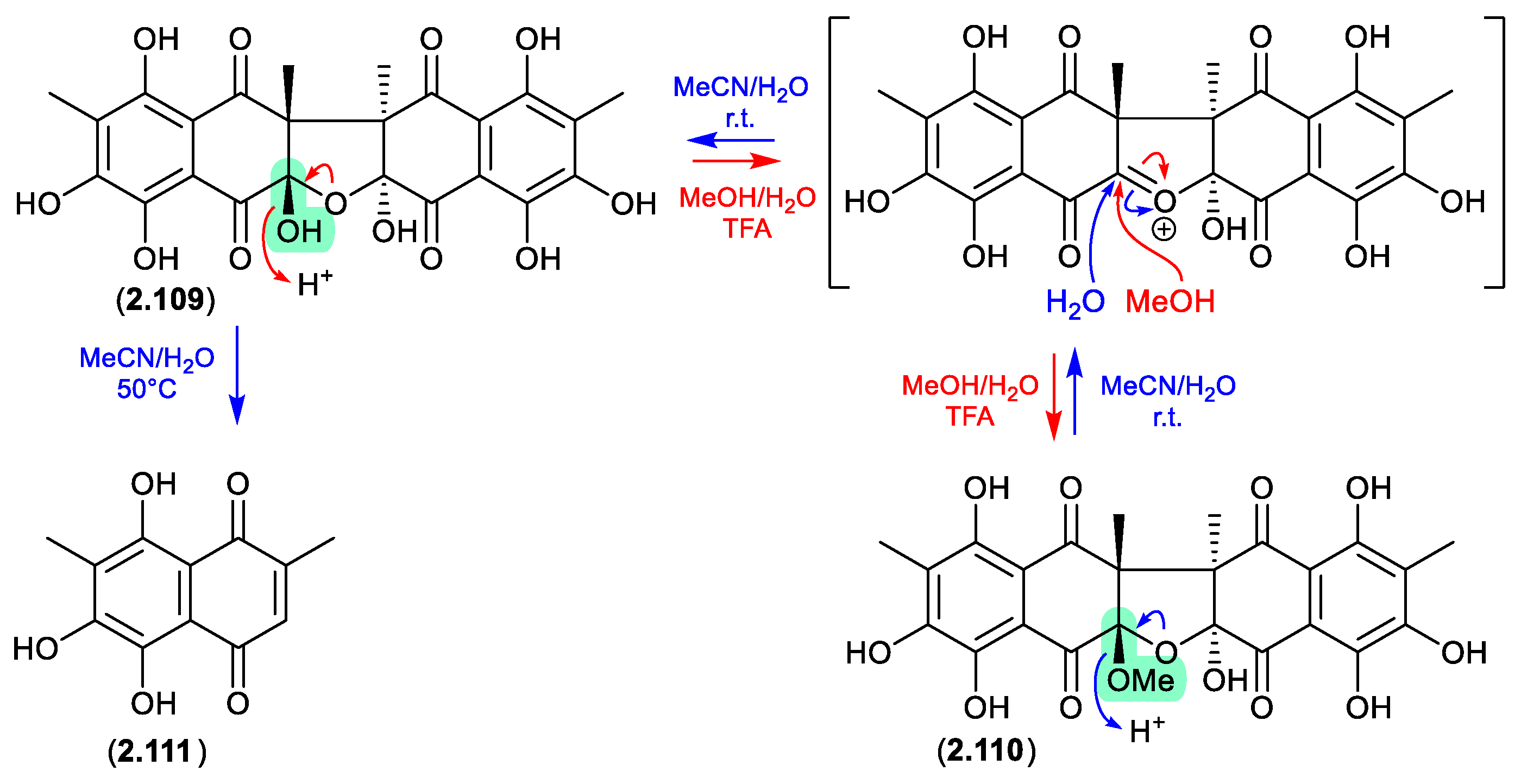

Talaromyces johnpittii MST-FP2594 yielded the new binaphthazarin talcarpones A (

2.109) and B (

2.110), along with the known monomeric naphthoquinone aureoquinone (

2.111).[

50] When stored in aqueous MeCN at r.t.

2.110 transformed to

2.109 (presumably via H

2O addition to an oxonium intermediate), and on heating (50 °C) further transformed to

2.111. Conversely, at r.t. an acidic MeOH (5% TFA) solution of

2.109 transformed to

2.110 (presumably via MeOH addition to an oxonium intermediate). As the acetone extract of

T. johnpittii was subjected to silica gel (CH

2Cl

2/MeOH) chromatography (see

Section 4.3), it seems likely

2.110 is a methanolysis artifact of

2.109.

2.6. Chloroform

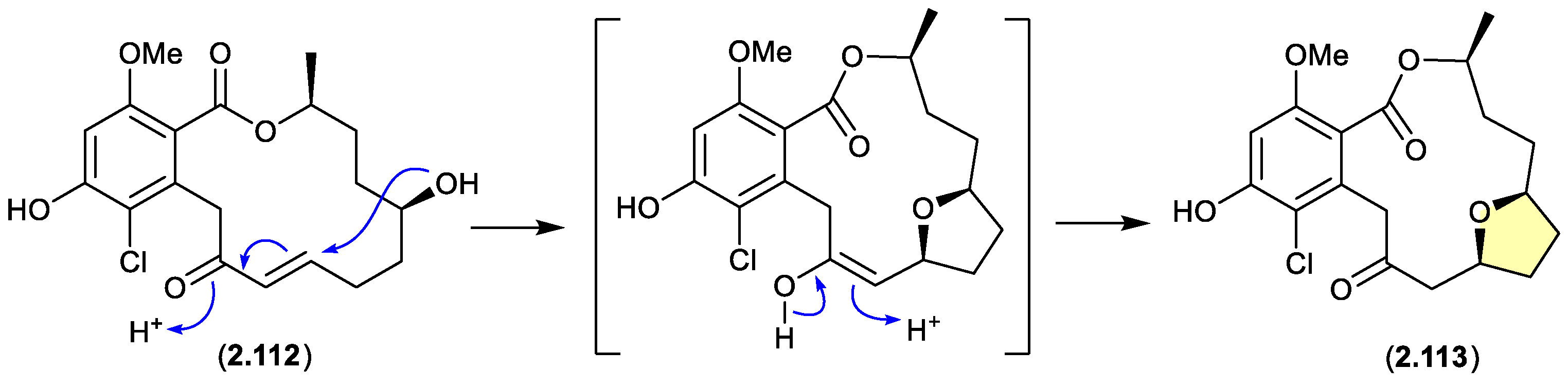

greensporones (Figure 2.6.1)

A CDCl

3 solution of the resorcylic acid lactone greensporone D (

2.112), isolated from the aquatic fungus

Halenospora sp. G87, underwent conversion via an intramolecular Michael addition to the tetrahydrofuran greensporone F (

2.113).[

51]

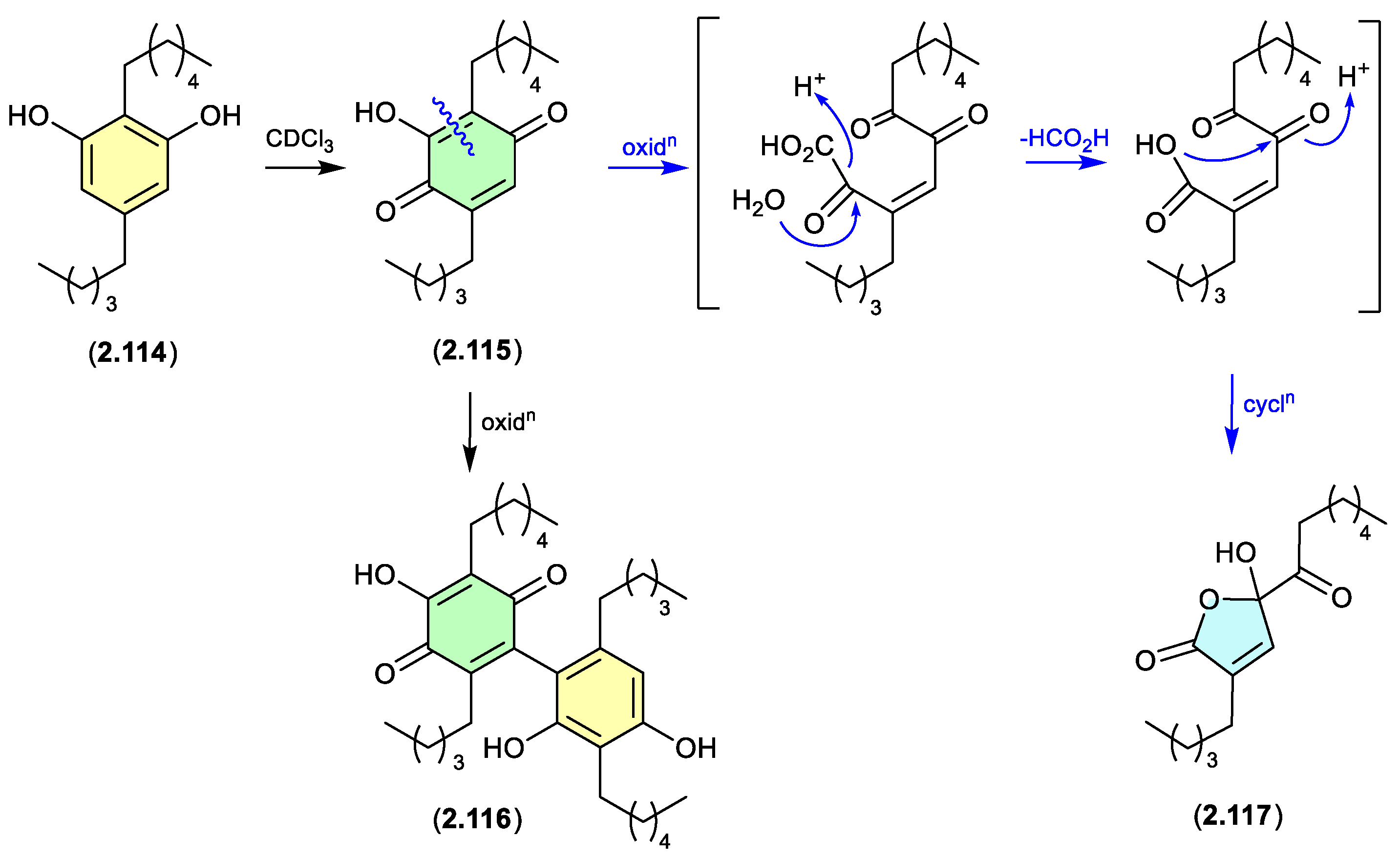

alkyl resorcinols (Figure 2.6.2)

Alkyl resorcinols isolated from the Chinese soil-derived

Pseudomonas aurantiaca YM03-Y3, underwent oxidative transformation a r.t. in CDCl

3 solution, with

2.114 yielding the quinone

2.115, dimer

2.116, ring contracted butanolide

2.117 (the latter likely through the oxidative decarboxylation), and a range of minor products.[

52]

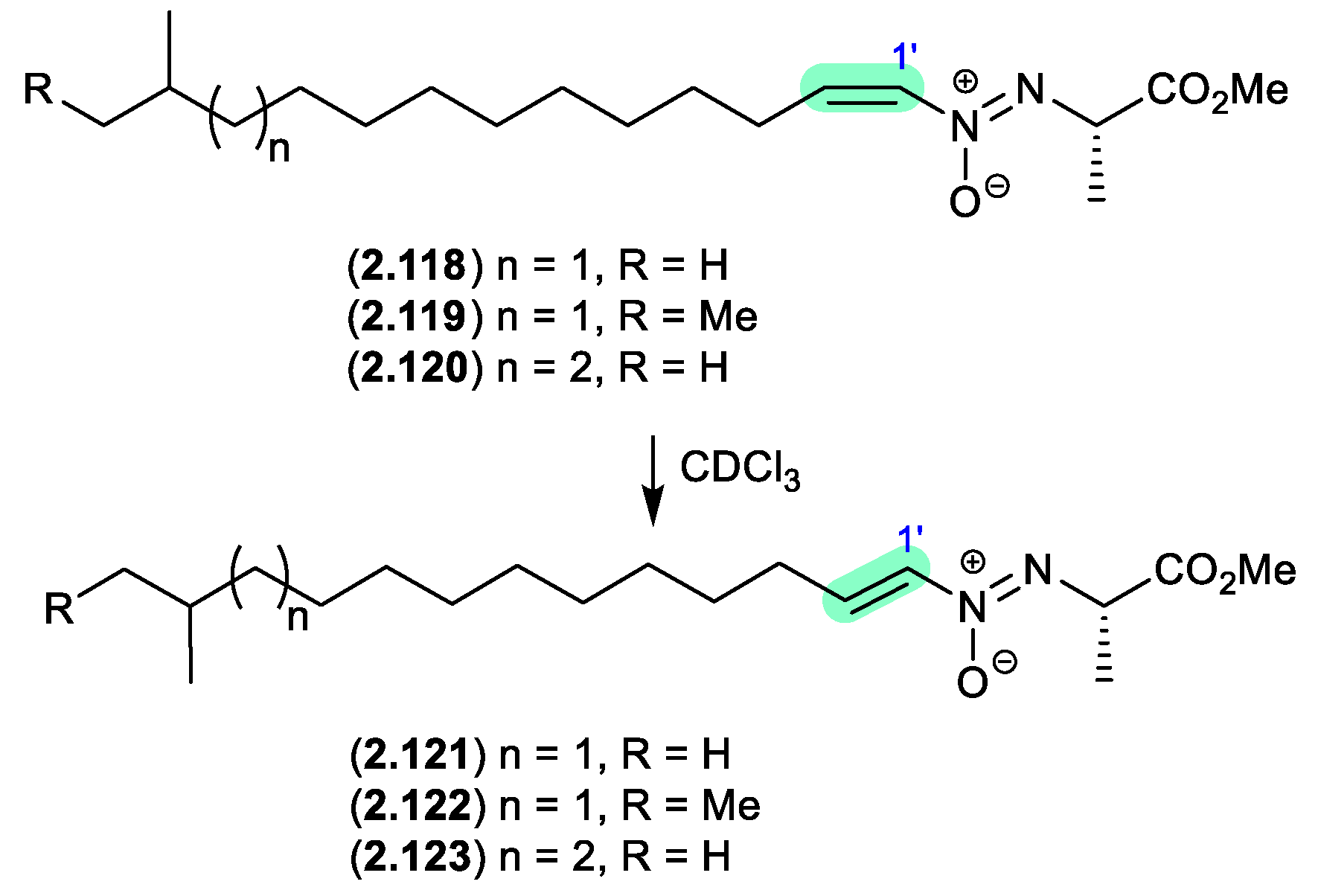

azodyrecins (Figure 2.6.3)

On prolonged storage (30 d) at r.t. a CDCl

3 solution of the soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. P8-A2 azoxy compounds, azodyrecins A–C (

2.118–

2.120), underwent quantitative double bond isomerization to the

E-isomers, 1’-

trans-azodyrecins A–C (

2.121–

2.123).[

53]

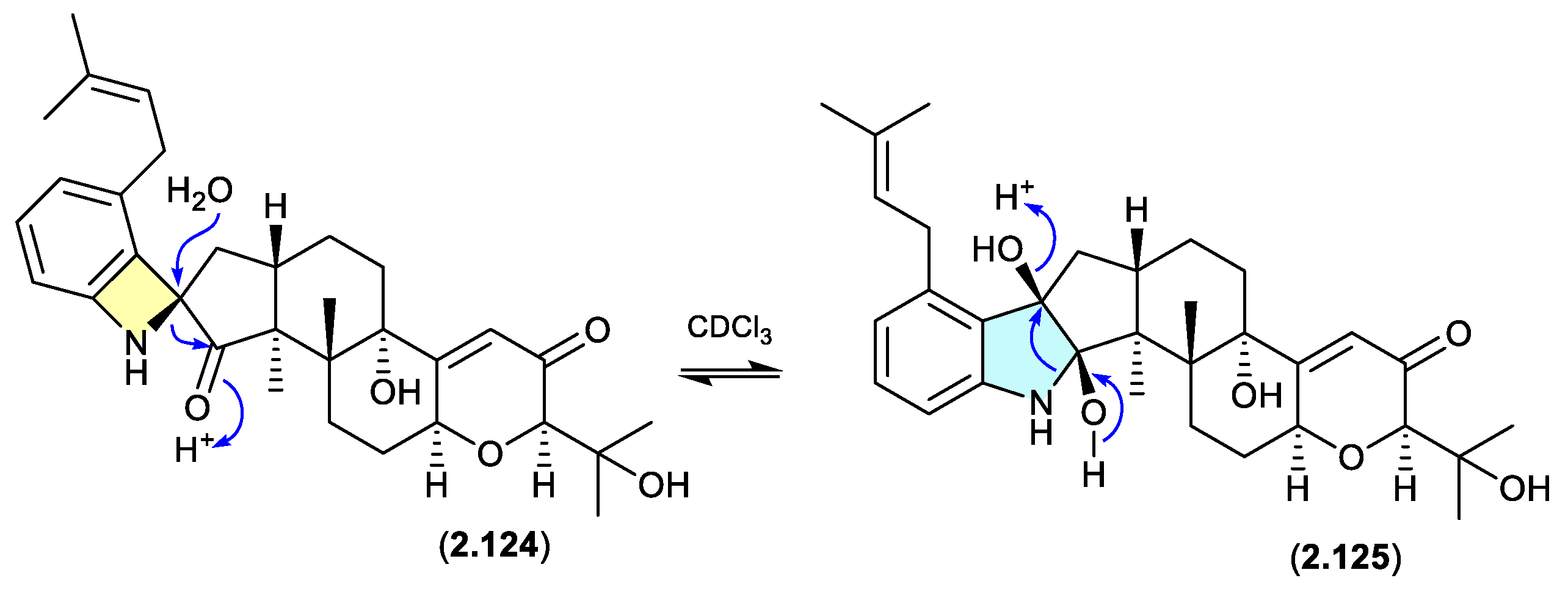

schipenindolenes (Figure 2.6.4)

The Chinese fungal endophyte

Penicillium sp. DG23 yielded indole-diterpenes with HMG-CoA reductase degrading activity, with schipenindolenes E (

2.124) and I (

2.125) undergoing an unexpected equilibration when stored for 2 days at r.t. in CDCl

3.[

54]

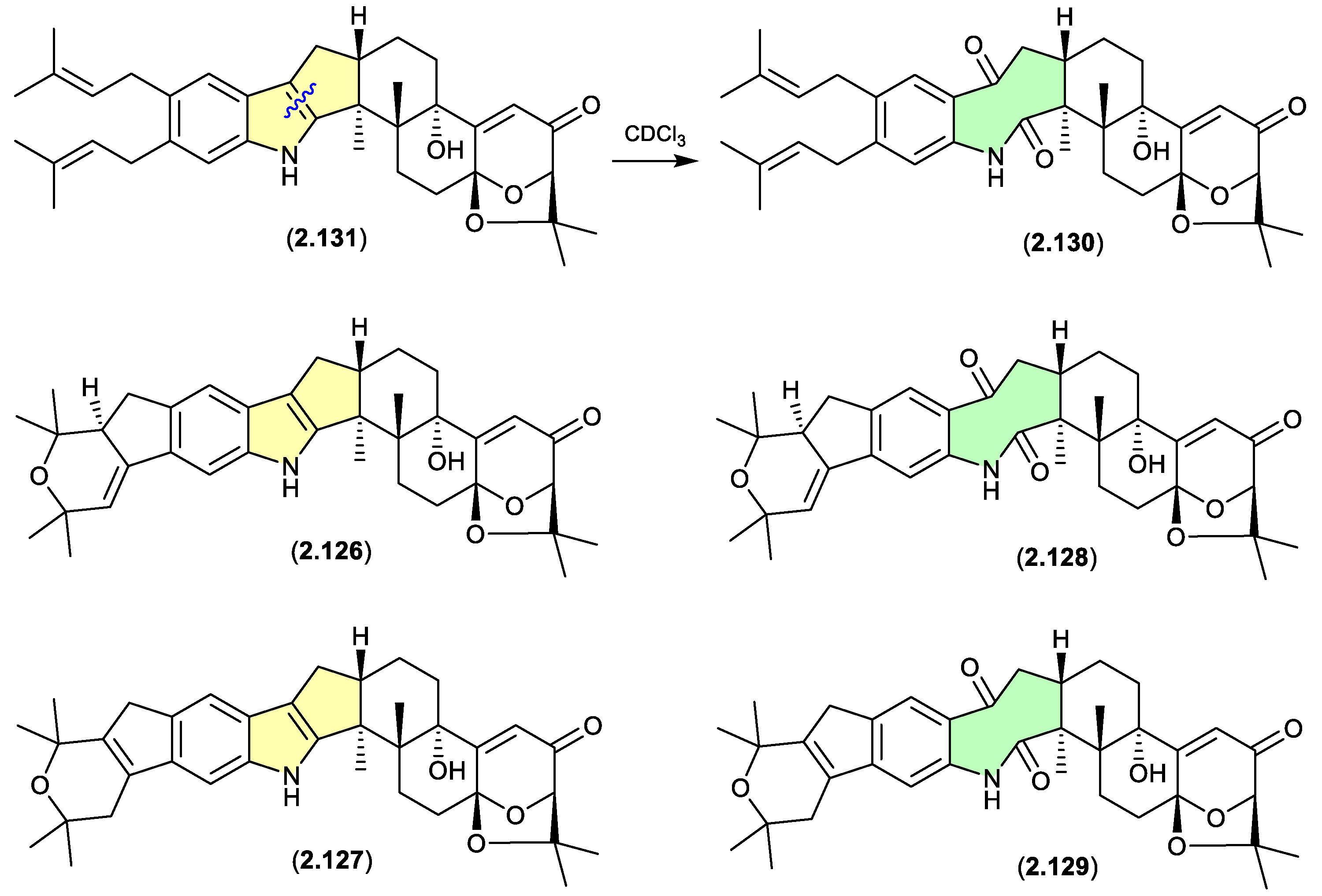

shearinines (Figures 2.6.5 and 2.6.6)

A Chinese mangrove-derived

Penicillium sp. yielded an array of new indolo-terpenes, of which noteworthy examples (relevant to this review) include shearinines A (

2.126), F (

2.127), I (

2.128), H (

2.129), J (

2.130) and K (

2.131).[

55] Significantly, in CDCl

3 at r.t. shearinine K (

2.131) partially transformed to shearinine J (

2.130). As fractionation of the fermentation involved silica gel (CH

2Cl

2/MeOH) chromatography, it is likely

2.130 is an artifact of

2.131. Extrapolating on this, it’s also likely that shearinines I (

2.128) and H (

2.129) are comparable artifacts of shearinines A (

2.126) and F (

2.127), respectively.

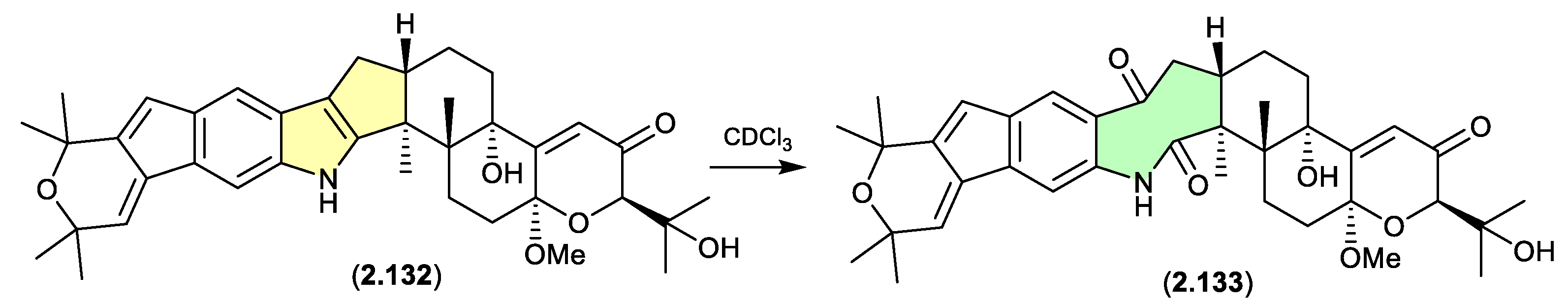

The Chinese mangrove rhizosphere soil-derived fungus

Penicillium sp. N4-3 yielded further examples of the shearinine structure class, including shearinine S (

2.132), which in CDCl

3 transformed to the artifact shearinine T (

2.133).

[56] It has been proposed that this oxidative ring opening is initiated by autoxidation.[

55,

56]

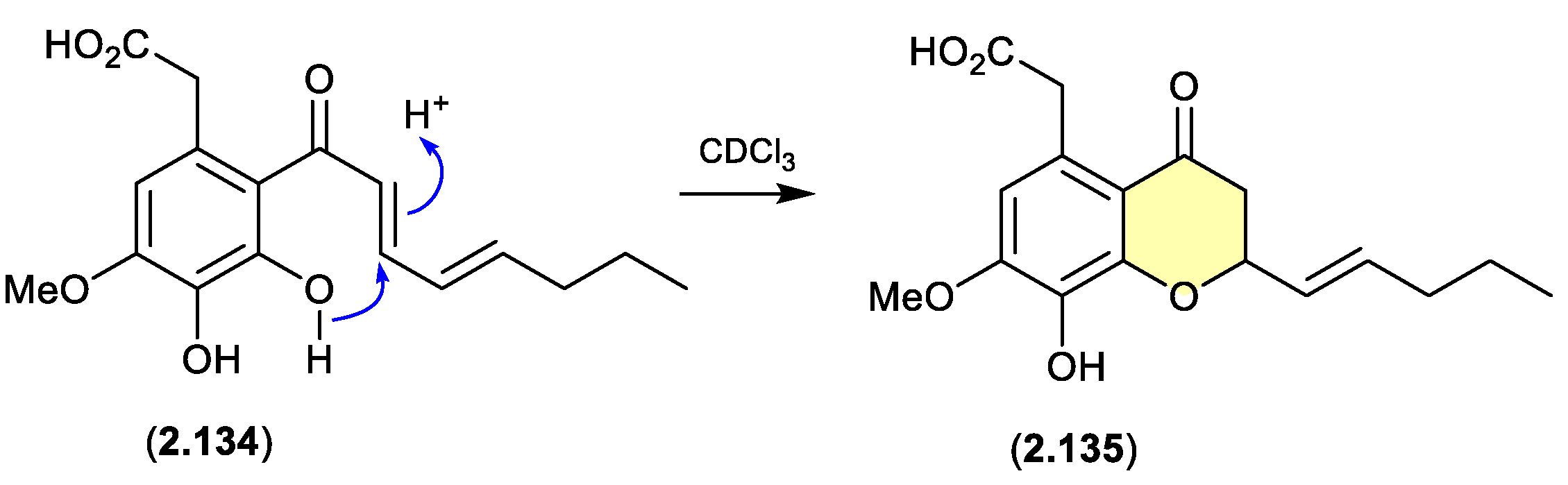

cavoxin/cavoxone (Figure 2.6.7)

A revision of the structure of cavoxin (

2.134) (also known as aposphaerin A) produced by the fungus

Phoma cava, reaffirmed that exposure to CDCl

3 initiates an intramolecular acid-mediated cyclisation to yield the artifact cavoxone (

2.135).[

57]

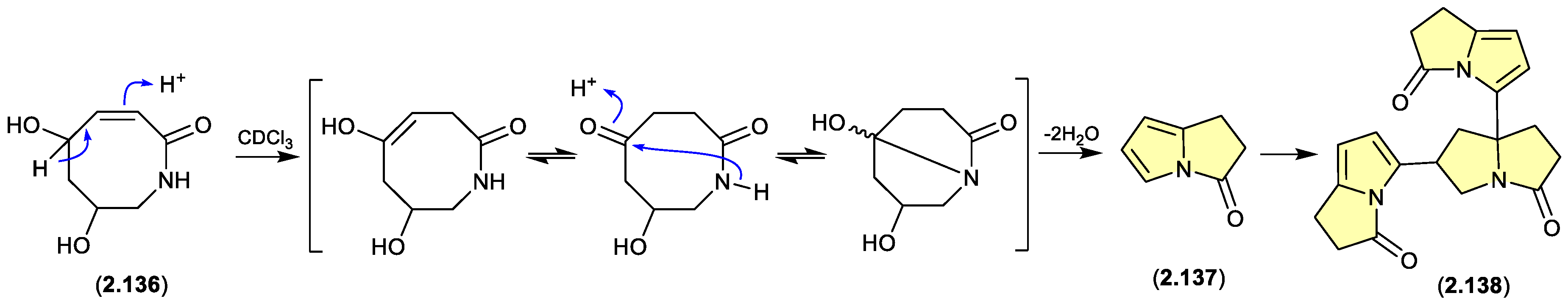

pyrrolizin-3-ones (Figure 2.6.8)

The marine-derived

Streptomyces sp. QD518 yielded the azocin-2-one

2.136, which during NMR (CDCl

3) data acquisition underwent complete transformation to

2.137 and

2.138.[

58] A plausible ring rearrangement mechanism is proposed below.

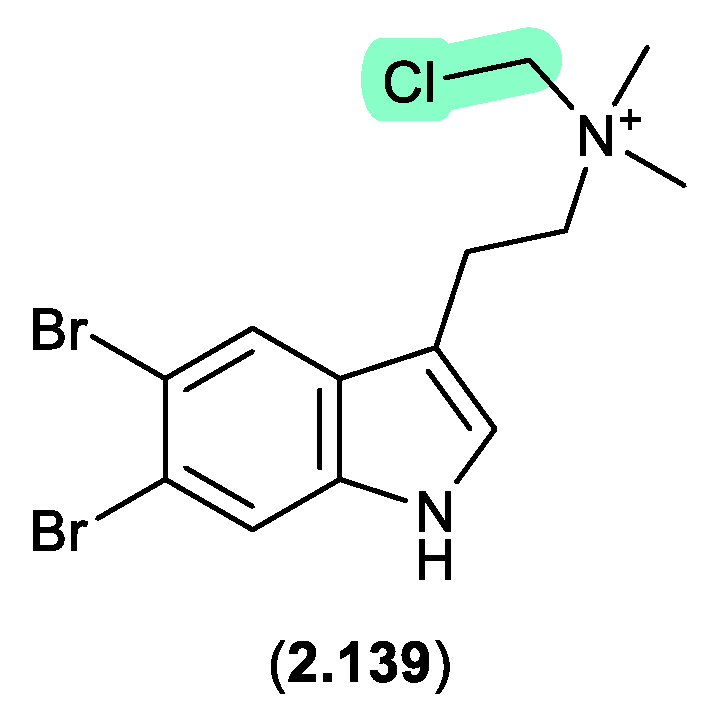

2.7. Dichloromethane

bromotyramines (Figure 2.7.1)

Bromotryptamines recovered from a tropical southwestern Pacific Ocean collection of the marine sponge

Narrabeena nigra included the

N-chloromethyl

2.139, which would have been formed as an artifact during exposure to CH

2Cl

2.[

59]

2.8. Benzene

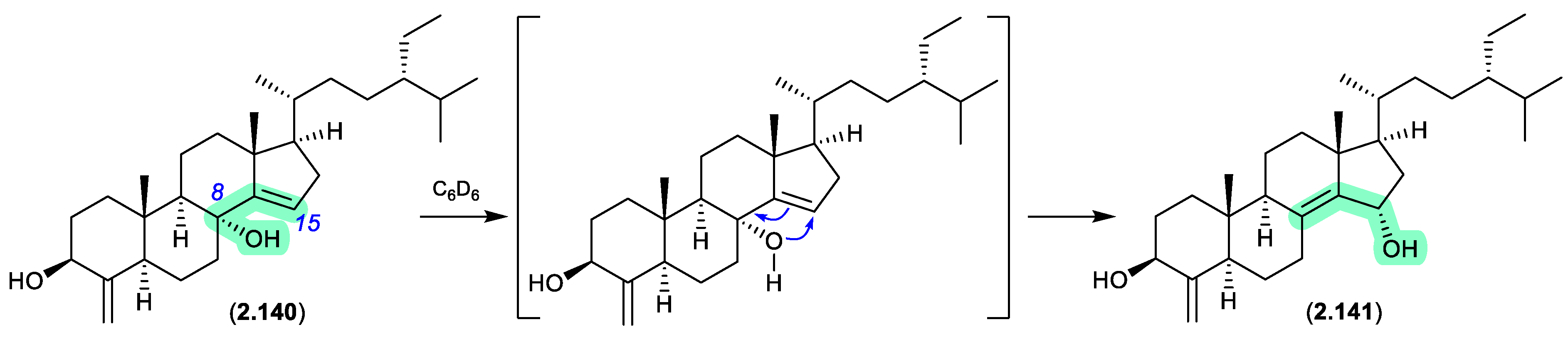

theonellastrols (Figure 2.8.1)

Oxygenated sterols from a Philippines marine sponge

Theonella swinhoei included 8α -hydroxytheonellasterol (

2.140), which in benzene-

d6 at r.t. underwent spontaneous allylic hydroxy migration to the artifact 15α-hydroxytheonellasterol (

2.141).[

60]

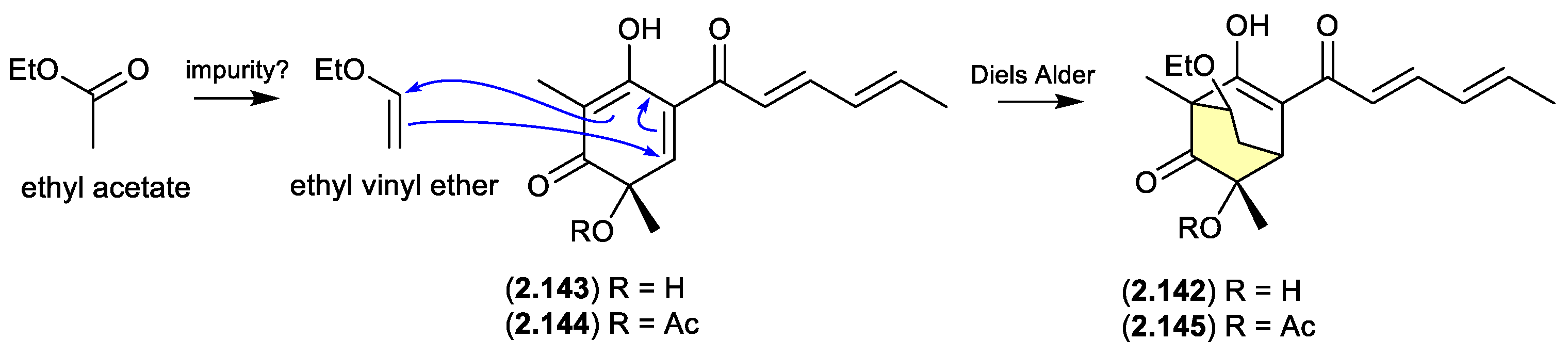

2.9. Ethyl Acetate

sorbicillinol/sorbivetone (Figure 2.9.1)

The new sorbicillinoid sorbivinetone (

2.142) (also known as rezishanone C) isolated from the sponge-derived fungus

Penicillium chrysogenum DSM 16137 featured a biosynthetically unusual ethoxy moiety.[

61] This prompted speculation that

2.142 could be a Diels Alder cycloaddition artifact of ethyl vinyl ether (potentially an impurity in EtOAc) and sorbicillinol (

2.143) — the latter a highly reactive natural product and precursor of many sorbicillin-derived fungal metabolites, known to readily undergo Diels Alder reactions.[

62] Supportive of this hypothesis, [

13C

2]-acetate incorporation studies revealed that neither the ethoxy moiety, or the two bridging C-atoms were labelled. Furthermore, a dilute aqueous MeCN solution of ethyl vinyl ethyl and the more stable

O-acetylsorbicillinol (

2.144), yielded the predicted Diels Alder adduct,

O-acetylsorbivinetone (

2.145).

2.10. Aprotic vs Protic

While not strictly artifacts, the following examples reveal how natural products can change structure in response to the solvent they are dissolved in — in particular between polar protic, versus less polar aprotic solvents. This has particular relevance when exploring SAR and in attempting molecular docking analyses of binding interactions with putative molecular targets.

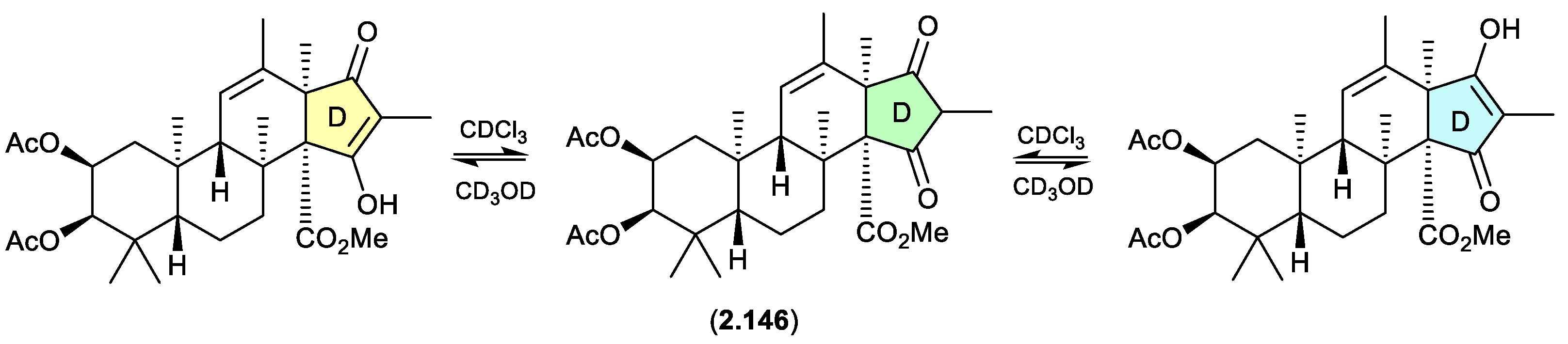

oxandrastins (Figure 2.10.1)

The Australian fungus

Penicillium sp. CMB-MD14 yielded an array of meroterpenes, exemplified by oxandrastin A (

2.146), where ring D exists in two solvent dependent tautomers, as evident in the NMR (CDCl

3) and NMR (methanol-

d4) spectra.[

63]

alaeolide (Figure 2.10.2)

The Japanese marine sediment-derived

Streptomyces sp. NPS554 yielded the polycyclic polyketide akaeolide (

2.147), which exists as two solvent dependent tautomers — as evident in the NMR (CDCl

3) and NMR (pyridine-

d5) spectra.[

64]

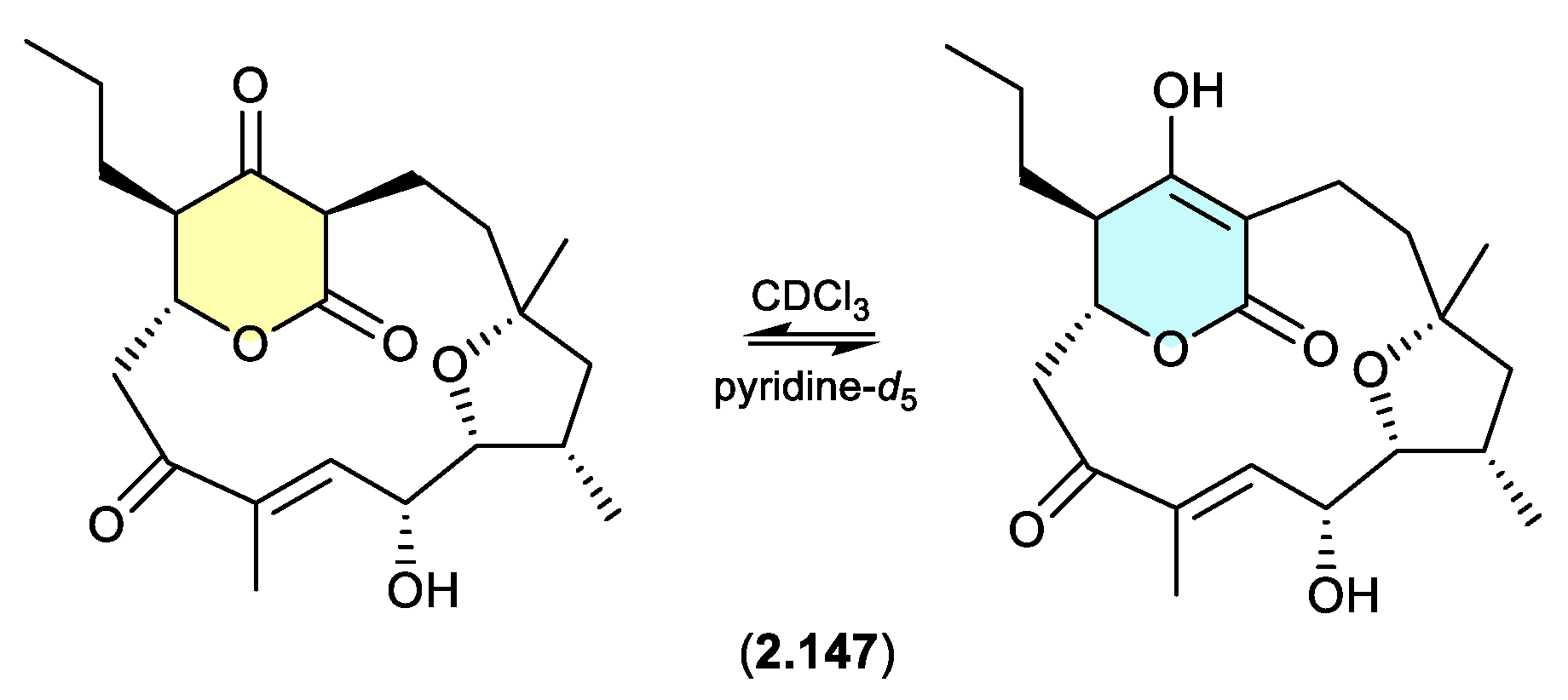

pratensilins/pratenone A (Figures 2.10.3 and 2.10.4)

A 2017 account of the Chinese marine sediment-derived

Streptomyces sp. KCB-132 reported three spiro indolinone-naphthofuran enantiomeric pairs, (+)-(

S)-pratensilin A (

2.148) and (–)-(

R)-pratensilin A (

2.149); (+)-(

S)-pratensilin B (

2.150) and (–)-(

R)-pratensilin B (

2.151); and (+)-(

S)-pratensilin C (

2.152) and (–)-(

R)-pratensilin C (

2.153).[

65] Following resolution by chiral HPLC, the A pair (

2.148/

2.149) equilibrated in both MeOH and CH

2Cl

2, whereas the B pair (

2.150/

2.151) only equilibrated in MeOH, and the C pair (

2.152/

2.153) did not equilibrate in either solvent. While the authors propose two mechanisms, both require the loss of naphthalene aromaticity. An alternate mechanism proceeds via collapse of the embedded aminol to an achiral oxonium intermediate, followed by recyclization with scrambling of chirality. The increased level of substitution on the

spiro lactam nitrogen could explain the lack of reactivity of

2.152/

2.153. In addition to retaining naphthalene aromaticity, an oxonium pathway would also benefit from stabilisation by polar solvents and the adjacent electron rich naphthalene system. As the isolation of the pratensilins involved MeOH extraction followed by silica gel and HPLC with a MeOH eluant, it’s possible one of the enantiomers in each pair is an artifact.

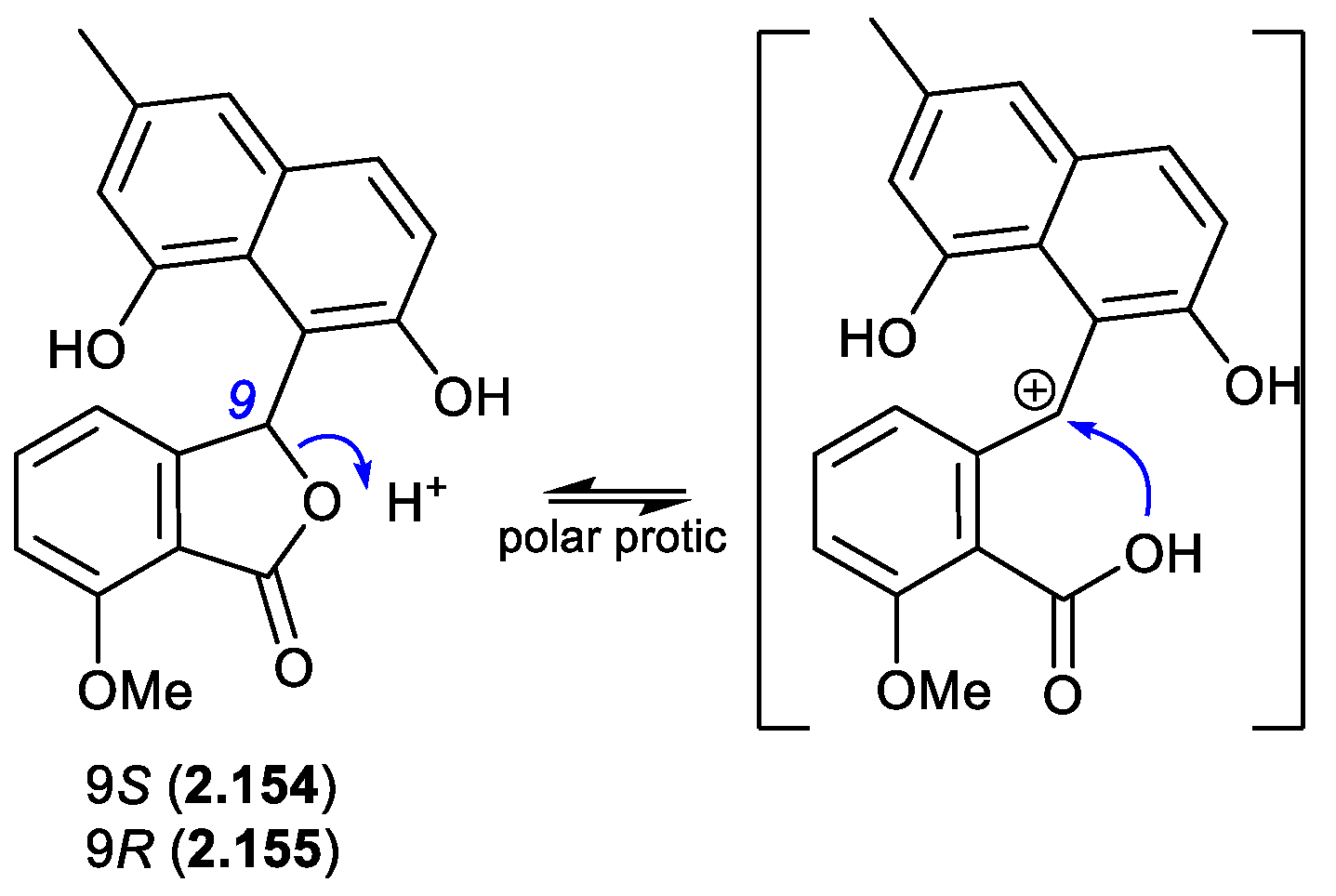

In a follow-up 2020 study,

Streptomyces sp. KCB-132 was also reported to yield another enantiomeric pair, (–)-(

S)-pratenone (

2.154) and (+)-(

R)-pratenone (

2.155).[

66] Following resolution by chiral HPLC, both enantiomers rapidly racemised (~10 min) in the polar solvents MeOH and THF, but were less prone to racemization in CH

2Cl

2 and MeCN. A proposed equilibration mechanism that proceeds via a carbocation (and retains naphthalene aromaticity) would be stabilised by polar over non-polar solvents, and by the electron rich naphthalene system. As with the pratensilins, the fermentation was initially extracted with MeOH, before being subjected to both silica gel and HPLC with a MeOH eluant, leaving open the possibility that one of the enantiomers is a handling artifact.

3. Heat

If subjected to elevated temperatures, such as during in vacuo solvent removal from extracts, fractions or pure compounds on a rotary evaporator with a water bath heated to >50 °C, many natural products will decompose (partially or fully), and yet others will transform to artifacts. Consider the following examples.

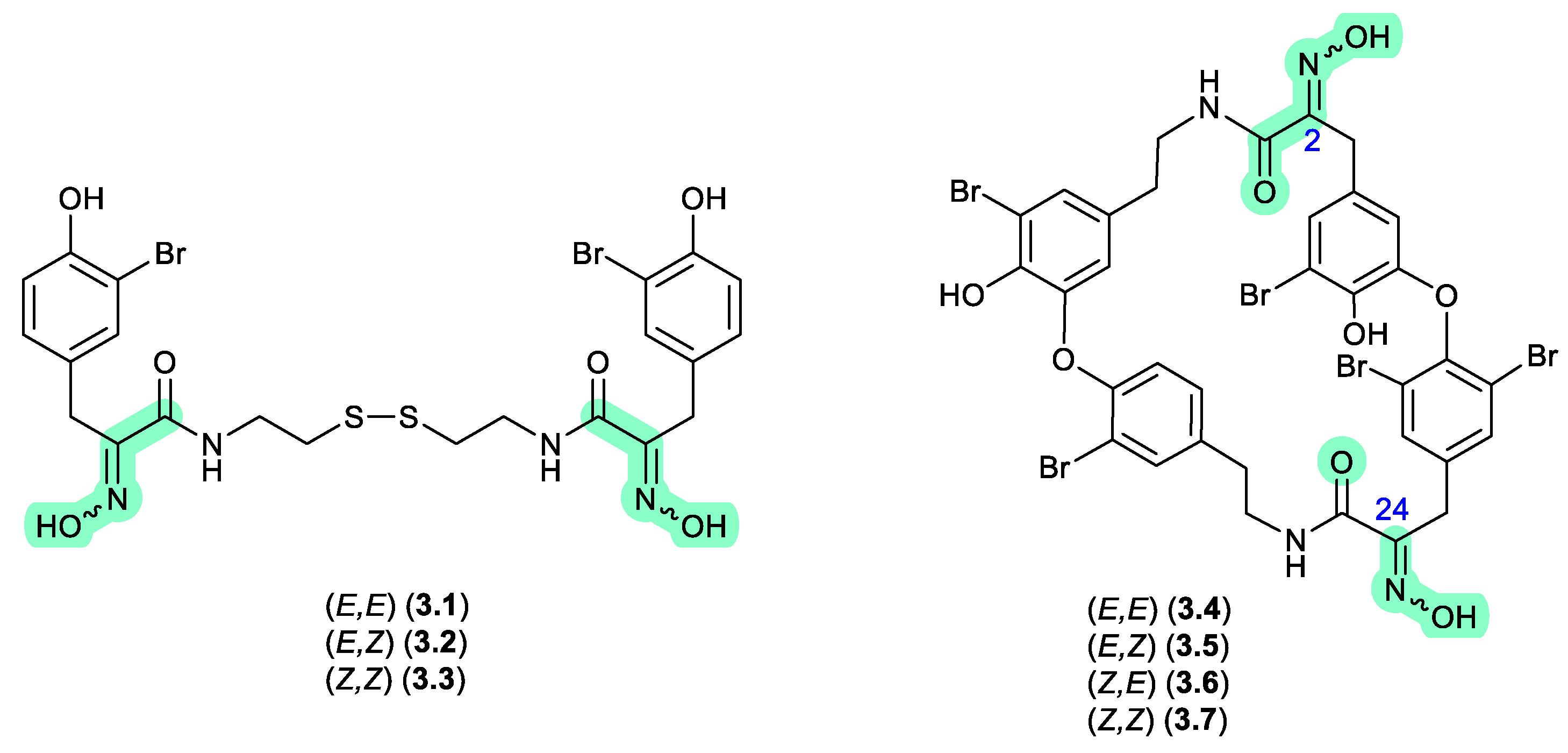

psammaplins and bastadins (Figure 3.1)

In 1987, Schmitz et al reported the isomeric oximes, (

E,E)-psammaplin A (

3.1) and (

E,Z)-psammaplin A (

3.2) from an unidentified verongiid sponge.[

67] This study revealed that on recovery from NMR solvents with mild heating, and subsequent storage over a couple of weeks,

3.2 underwent quantitative transformation to

3.1 — prompting speculation that the true natural product may be the chemically reactive

Z,Z isomer (

3.3) (see Section 10). The next three decades saw a wealth of reports on structural diverse tyrosine-oxime sponge metabolites — perhaps best exemplified by the cyclic tetrapeptide bastadins common to the genera

Ianthella. With the literature largely dominated by

E oxime configurations

, in 2010 Crews et al reported the known (

E,E)-bastadin 19 (

3.4) along with the new isomer (

E,Z)-bastadin 19 (

3.5), from a Papua New Guinea collection of

Ianthella cf.

reticulata.[

68] Of particular note, a 1 h photolysis of (

E,E)-bastadin 19 (

3.4) in MeCN/MeOH with acetophenone as a sensitiser yielded all possible oxime isomers, namely (

E,E) (

3.4), (

E,Z) (

3.5), (

Z,E) (

3.6) and (

Z,Z) (

3.7). Likewise, a 30 min sonication (warming) of a DMSO solution of synthetic (

Z,Z) (

3.7) returned a mixture comprising the full suite of oximes isomers,

3.4–

3.7, which on standing in DMSO at r.t. for a further 720 h underwent quantitative conversion to (

E,E) (

3.4). These observations prompted Crews et al to speculate that

“…the bastadins and psammaplins initially contain the (Z)-oxime configuration and subsequently isomerize to the more thermodynamically stable E isomer in solution during extraction and/or workup.” — opening up the prospect that a great many sponge oximes reported in the scientific literature were in fact isolation and/or handling artifacts, and that the true (cryptic) natural products have gone unnoticed.

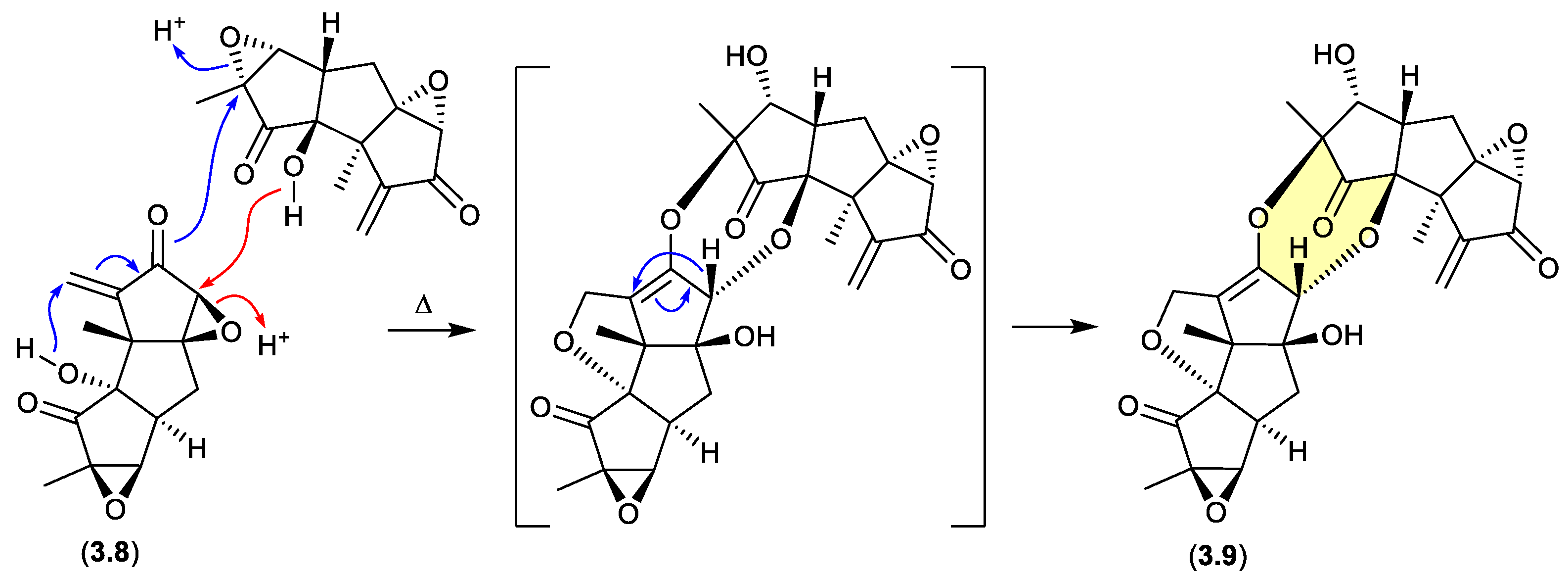

creolophins (Figure 3.2)

During isolation of the norhirsutane metabolites from culture extracts of the fungus

Creolophus cirrhatus, creolophin E (

3.8) was found to be thermally unstable, and on mild heating to 50 °C

in vacuo yielded the dimer neocreolophin (

3.9) through a cascading series of nucleophilic additions and a 1,3-sigmatropic hydride shift.[

69]

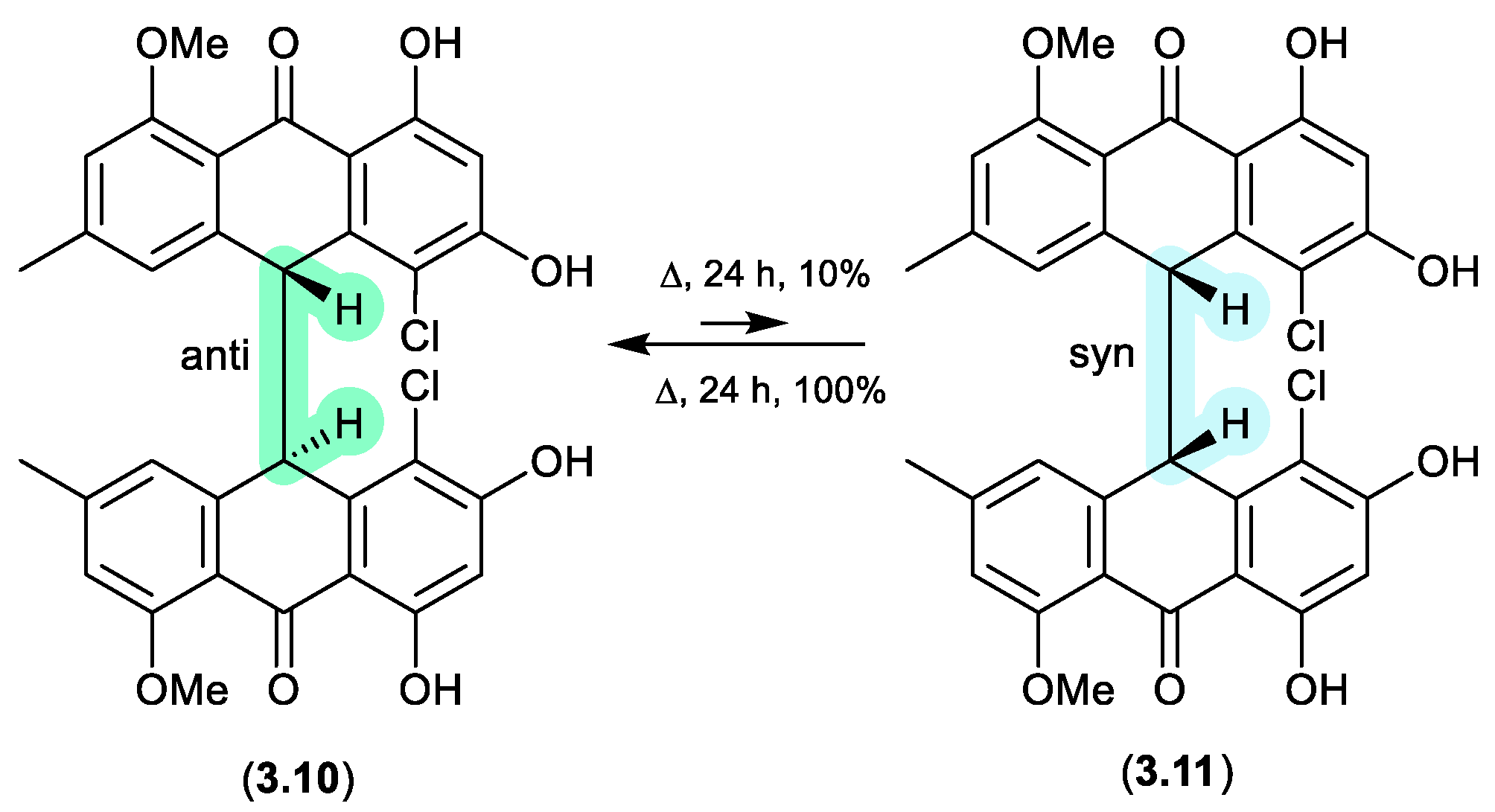

neobulgarones (Figure 3.3)

The Australian fungus

Penicillium sp. CMB-MD22 yielded a large array of bianthrones as pairs of selectively heat labile

anti and

syn diastereomers, exemplified by (±)-neobulgarone E (

3.10) and neobulgarone F (

3.11).[

70] For example, while heating of a MeOH solution of

anti 3.10 (24 h, 65 °C) led to only 10% conversion to

syn 3.11, similar treatment of

3.11 led to complete conversion to

3.10. Notwithstanding, careful analysis of a fresh fermentation prior to heating or fractionation detected an ~1:1 ratio of all

anti and

syn neobulgarones, confirming their status as natural products.

4. pH

Many natural products are susceptible to transformation under basic and/or acidic conditions. Variations in pH that occur naturally in fermentation broths, as well as in extracts rich in phenolics or alkaloids, can carry over to organic partitions and be further amplified during in vacuo concentration – particularly as pH modified aqueous residues are the last to evaporate. Changes in pH can also be introduced either inadvertently or deliberately during fractionation, for example, using acidic media (e.g. silica gel) and/or solvents (e.g. CHCl3 or CH2Cl2), or through the addition of eluant modifiers (e.g. TFA, formic acid, triethylamine (TEA), or various buffers). Variations in pH can also occur during long term storage in solvents that may become acidic over time (e.g. DMSO, CH2Cl2). Furthermore, as many natural products incorporate acidic or basic functional groups (e.g. phenols, carboxylic acids, amines, guanidines), concentrating/drying enriched fractions and/or pure samples can facilitate pH mediated transformations.

4.1. Basic

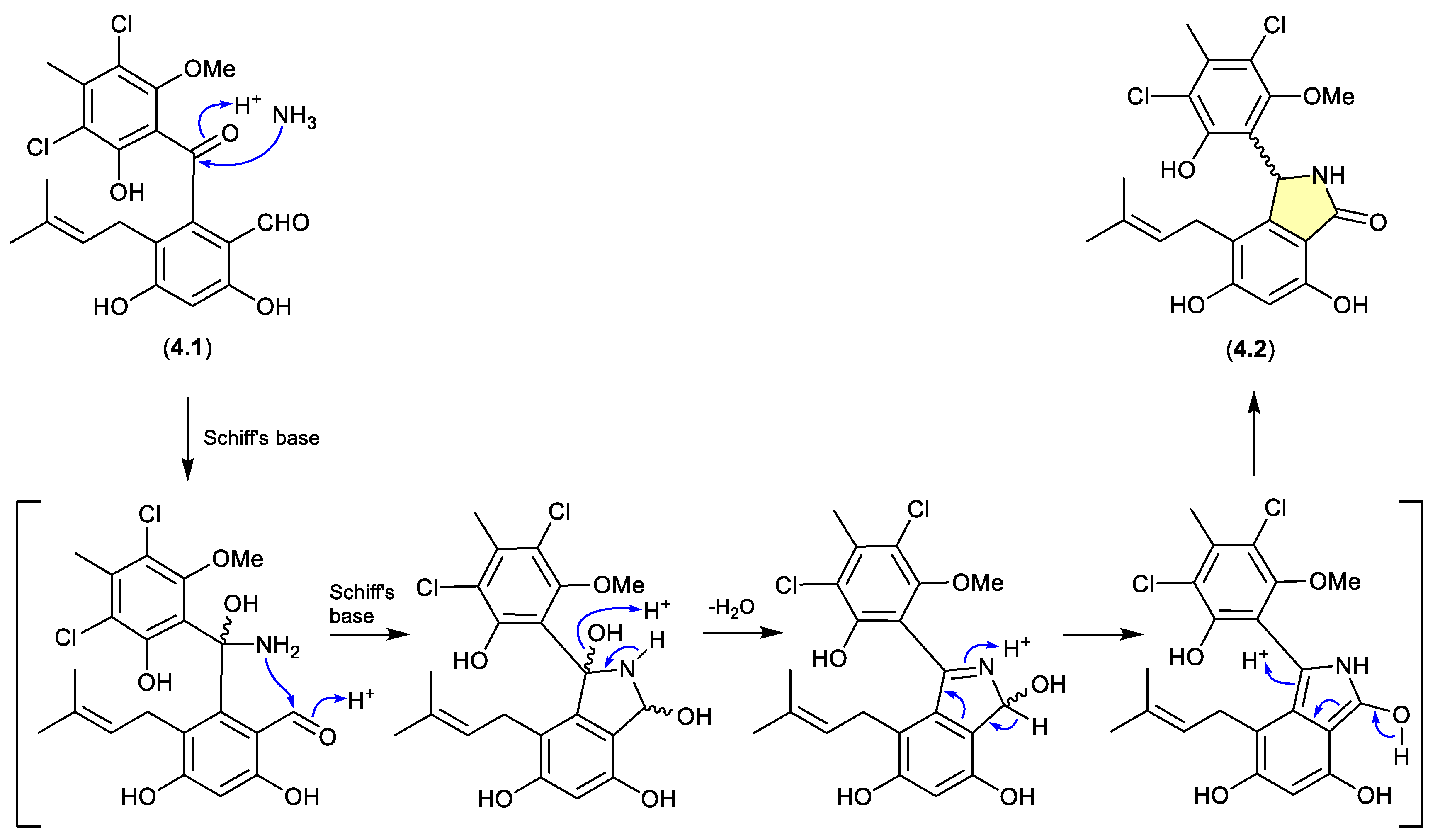

pestalone/pestalachloride (Figure 4.1.1)

The benzophenone pestalone (

4.1) was first reported in 2001 from the marine brown algae-derived fungus

Pestalotia sp. CNL-365 (now classified under the genus

Pestalotiopsis),[

71] with a subsequent 2008 report describing the racemic pestalachloride A (

4.2) from the plant endophytic fungus

Pestalotiopsis adusta L416.[

72] While racemic natural products are well known, they can nevertheless be indicators of inherent chemical reactivity that enable non-stereo controlled non-enzyme mediated transformations — much as is the case for artifacts. Interestingly, a 2010 total synthesis revealed that under mild conditions (NH

3/NH

4Cl/H

2O, r.t., 80 min)

4.1 underwent high yield conversion to

4.2.[

73] Of note, literature inference that

4.1 and

4.2 exist as enantiomeric mixtures of “stable” atropisomers does not seem plausible and lacks experimental validation. It’s more probable that

4.1 is achiral, and

4.2 is a racemic mixture of epimers.

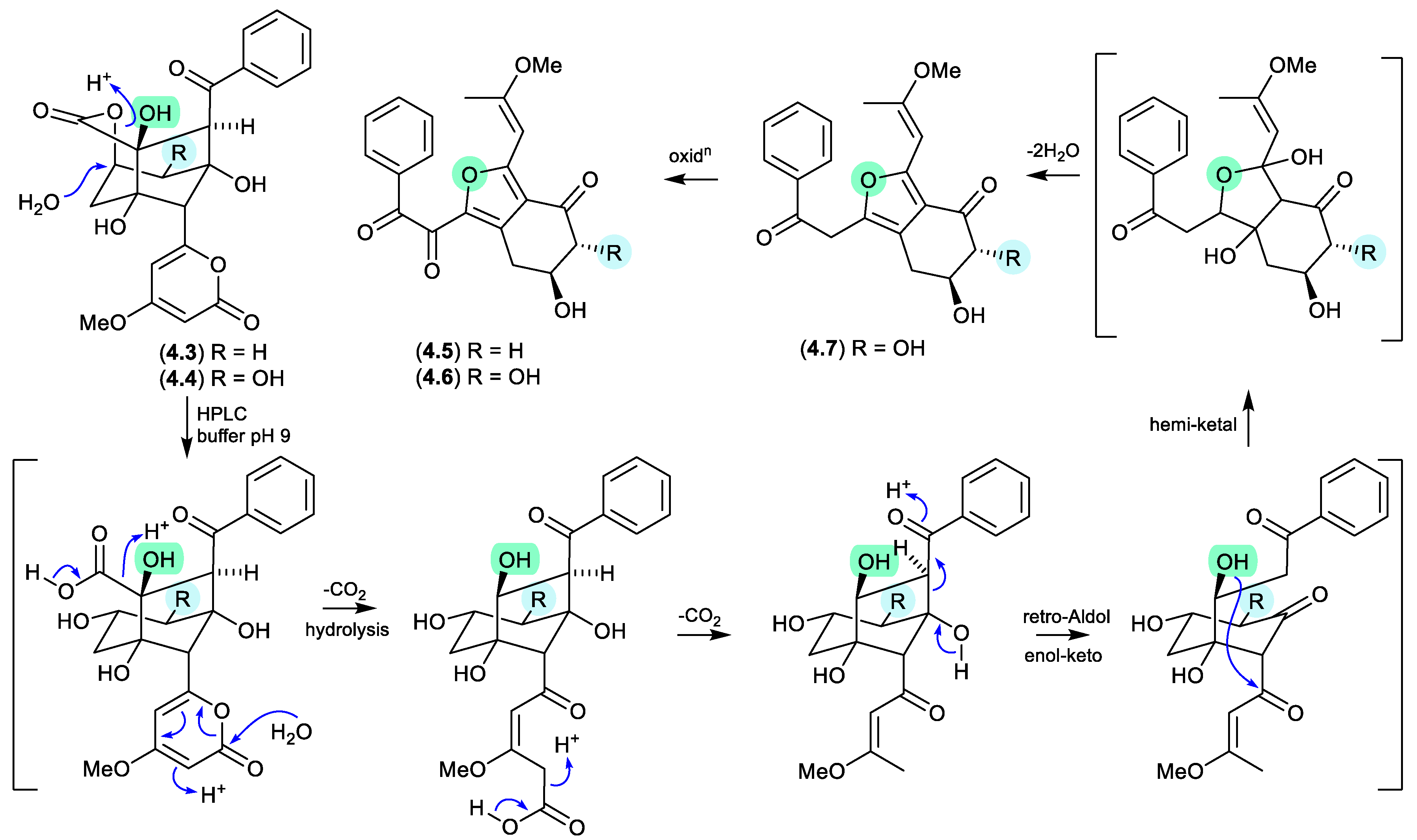

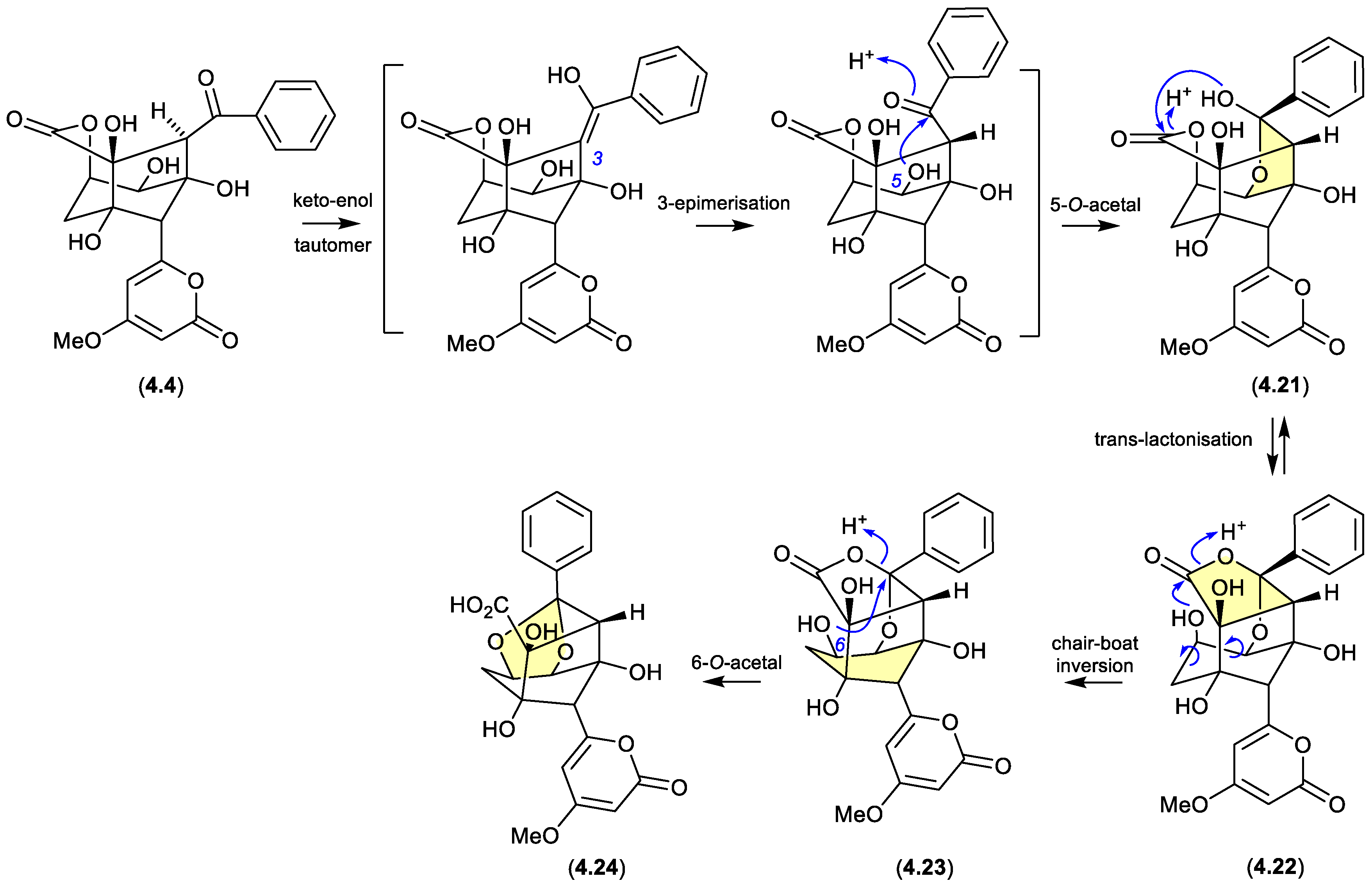

neoenterocins (Figure 4.1.2)

Modified M-AM3-D media cultivations of the South China Sea sediment-derived

Streptomyces sp. SCSIO 11863 yielded the known polyketides 5-deoxyenterocin (

4.3) and enterocin (

4.4), and the new neoenterocins A (

4.5) and B (

4.6).[

74] Significantly, HPLC analysis of enterocin (

4.4) in 20 mM PBS buffer (pH 9) yielded

4.6, and the putative precursor

4.7, revealing a non-enzymatic pathway from enterocins to neoenterocins.

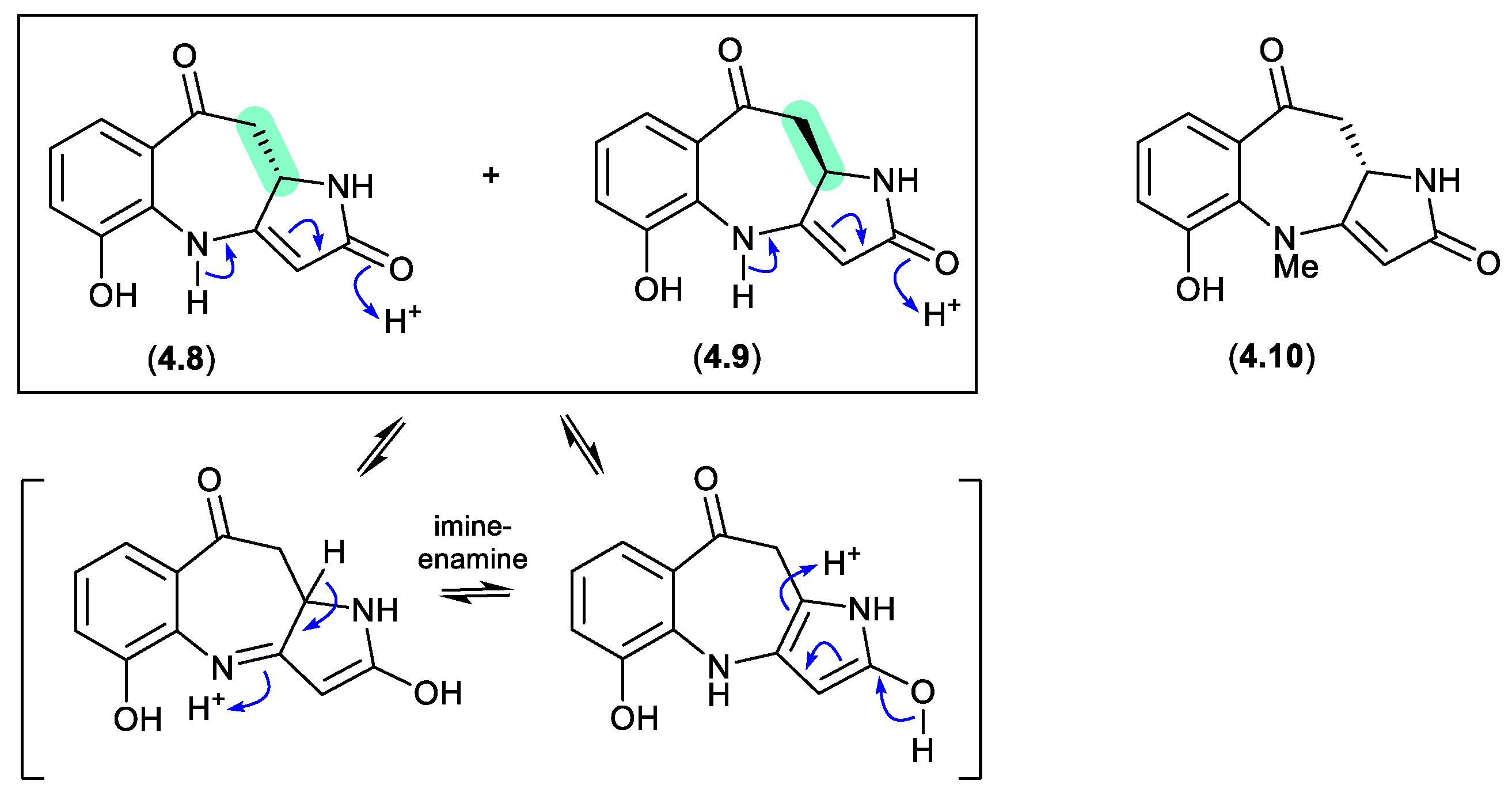

asperazepanones (Figure 4.1.3)

The gorgonian coral-derived fungus

Aspergillus candidus CHNSCLM-0393 yielded the benzoazepine alkaloids, (+)-asperazepanone A (

4.8), (–)-asperazepanone A (

4.9) and (+)-asperazepanone B (

4.10).[

75] While the enantiomers

4.8 and

4.9 could be resolved by chiral HPLC, under mildly basic conditions they rapidly equilibrated to a racemic mixture. The proposed enamine-imino tautomerism mechanism is not available to the

N-methylated analogue

4.10, which was isolated as the single (+) enantiomer, suggesting that

4.9 is an artifact.

hydroxybrevianamides (Figure 4.1.4)

The South China Sea soft coral-derived fungus

Aspergillus sp. CHNSCLM-0151 yielded two natural products, (+)-17-hydroxybrevianamide N (

4.11) and (+)-

N1-methyl-17-hydroxybrevianamide N (

4.12), each featuring a rare

o-hydroxyphenylalanine residue.[

76] On exposure to mild base,

4.11 and

4.12 formed a racemic mixture with the corresponding epimers

4.13 and

4.14, respectively.

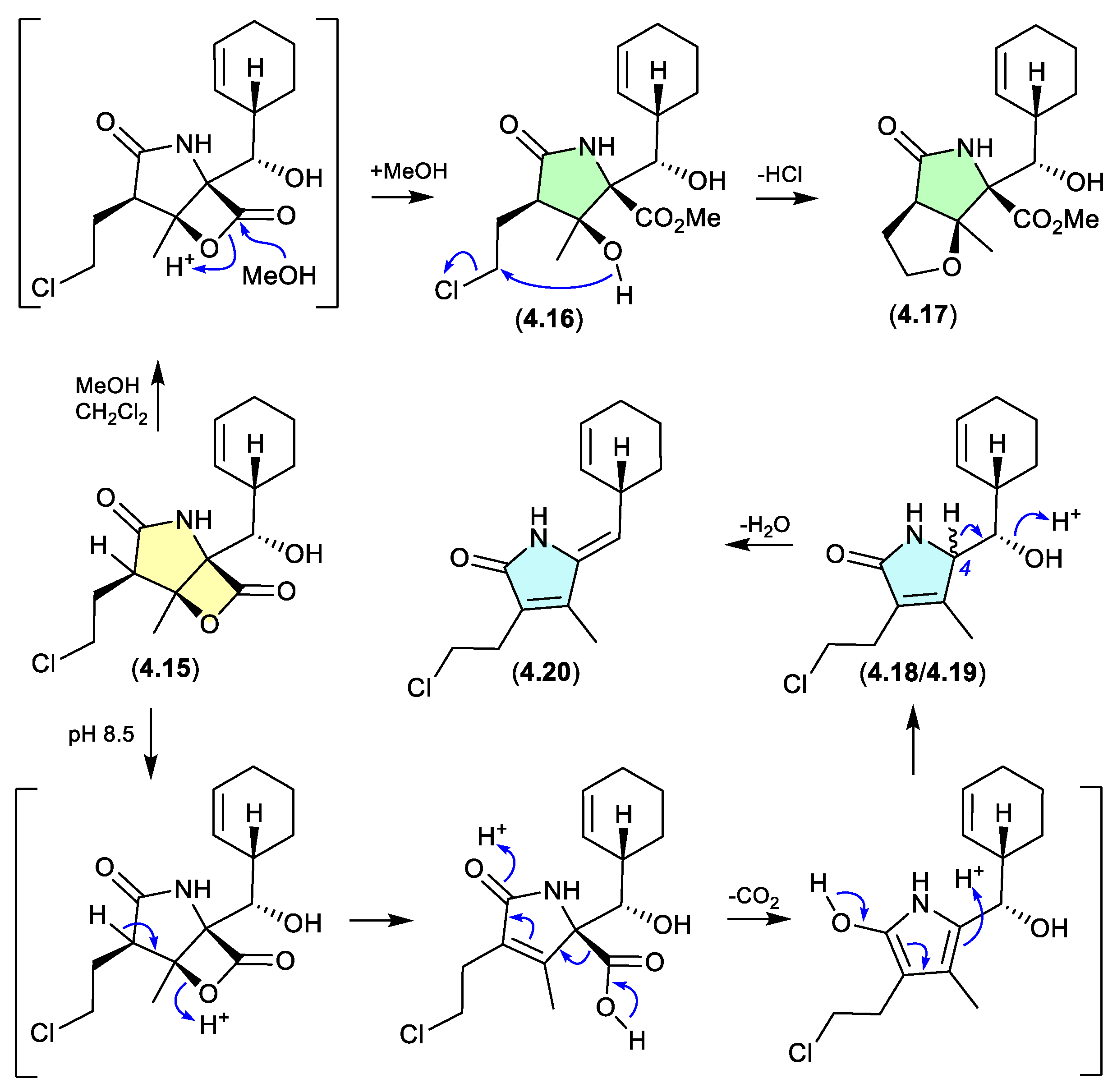

salinosporamides (Figure 4.1.5)

The marine obligate actinomycete

Salinispora tropica CNB-392 produced the potent proteasome inhibitor salinosporamide A (

4.15), along with five handling artifacts.[

77] These artifacts included the methanolysis products

4.16 and

4.17 (mimicking isolation conditions), and the base-mediated

seco-decarboxy epimers

4.18/

4.19, and its dehydration product

4.20 (mimicking the pH of the fermentation broth).

4.2. Acidic

enterocins (Figure 4.2.1)

The polyketide enterocin (

4.4) has been reported along with related analogues from a number of sources, including a Western Australian ascidian of the genus

Didemnum,[

78] the marine green alga-derived

Streptomyces sp. OUCMDZ-3434,[

79] and the shallow water marine sediment-derived

Streptomyces sp. BD-26T.[

80] A re-isolation of

4.4 from an Australian soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. CMB-MRB492 prompted the first detailed assessment of its chemical reactivity.[

81] When dried under nitrogen at r.t., extracts containing

4.4 proved stable, however, drying with warming to 40 °C resulted in partial conversion of

4.4 to a mixture of enterocins B (

4.21) and C (

4.22). Curiously, contrary to the more common role of acid activation of artifact formation, addition of trace amounts of TFA suppressed this thermal transformation. The same could not be said for

4.21 and

4.22, both of which when stored at r.t. for 24 h in MeCN/H

2O with 0.01% TFA underwent quantitative conversion to enterocin D (

4.23). While

4.23 proved stable to long term storage at low pH, when stored at r.t. for 24 h in MeCN/H

2O at pH 9 it underwent partial transformation to enterocin E (

4.24). The pH sensitivity of enterocin (

4.4) highlights the challenges faced in exploring SAR using cell-based bioassays, where the pH of cultures may vary, even during the course of the bioassay.

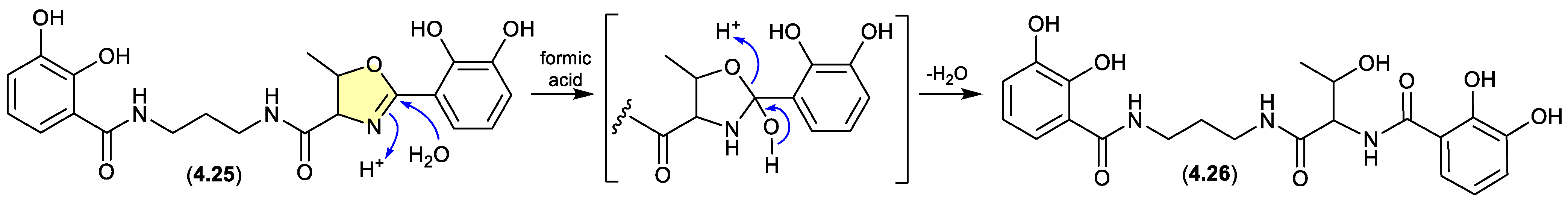

serratiochelin (Figure 4.2.2)

A co-culture of a

Shewanella sp. and a

Serratia sp., both sourced as a mixed culture from the intestine/stomach of an Atlantic hagfish (

Myxine glutinosa) collected by benthic trawl in Hadselfjorden (Norwegian Sea), yielded the known siderophore serratiochelin A (

4.25) and its formic acid-mediated hydrolysis artifact serratiochelin C (

4.26).[

82]

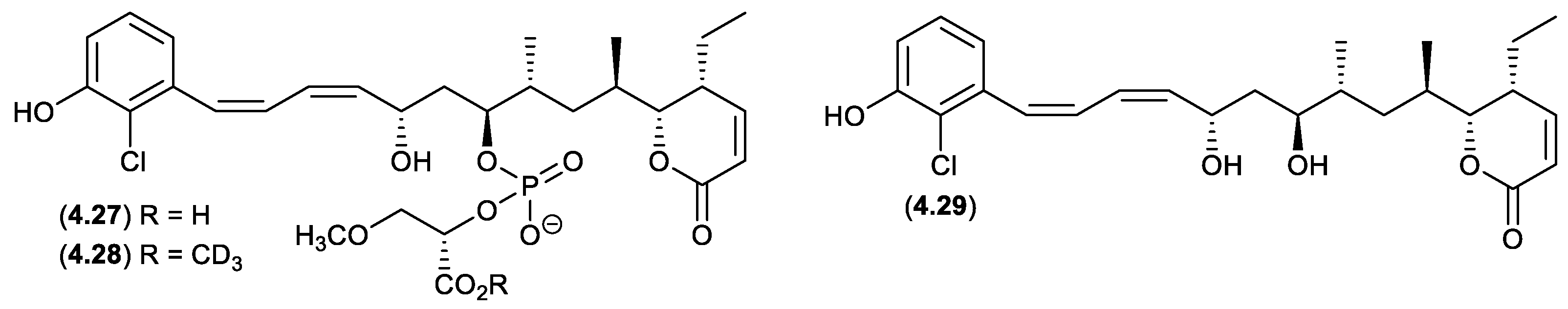

franklinolides (Figure 4.2.3)

An Australian marine sponge complex comprising a massive

Geodia sp. thinly encrusted with a

Halichondria sp. yielded the exceptionally cytotoxic franklinolide A (

4.27).[

83] A sample of

4.27 stored at r.t. in methanol-

d4 for several days yielded the deutero-methyl ester

4.28 and the hydrolysed artifact, bitungolide A (

4.29). The ease of transformation from

4.28 to

4.29 is noteworthy, given that

4.29 was first reported in 2002 from an Indonesian marine sponge, along with an array of geometric isomers, following extensive extraction with MeOH, silica gel chromatography (MeOH/CH

2Cl

2), and HPLC chromatography (MeOH/H

2O).[

84]

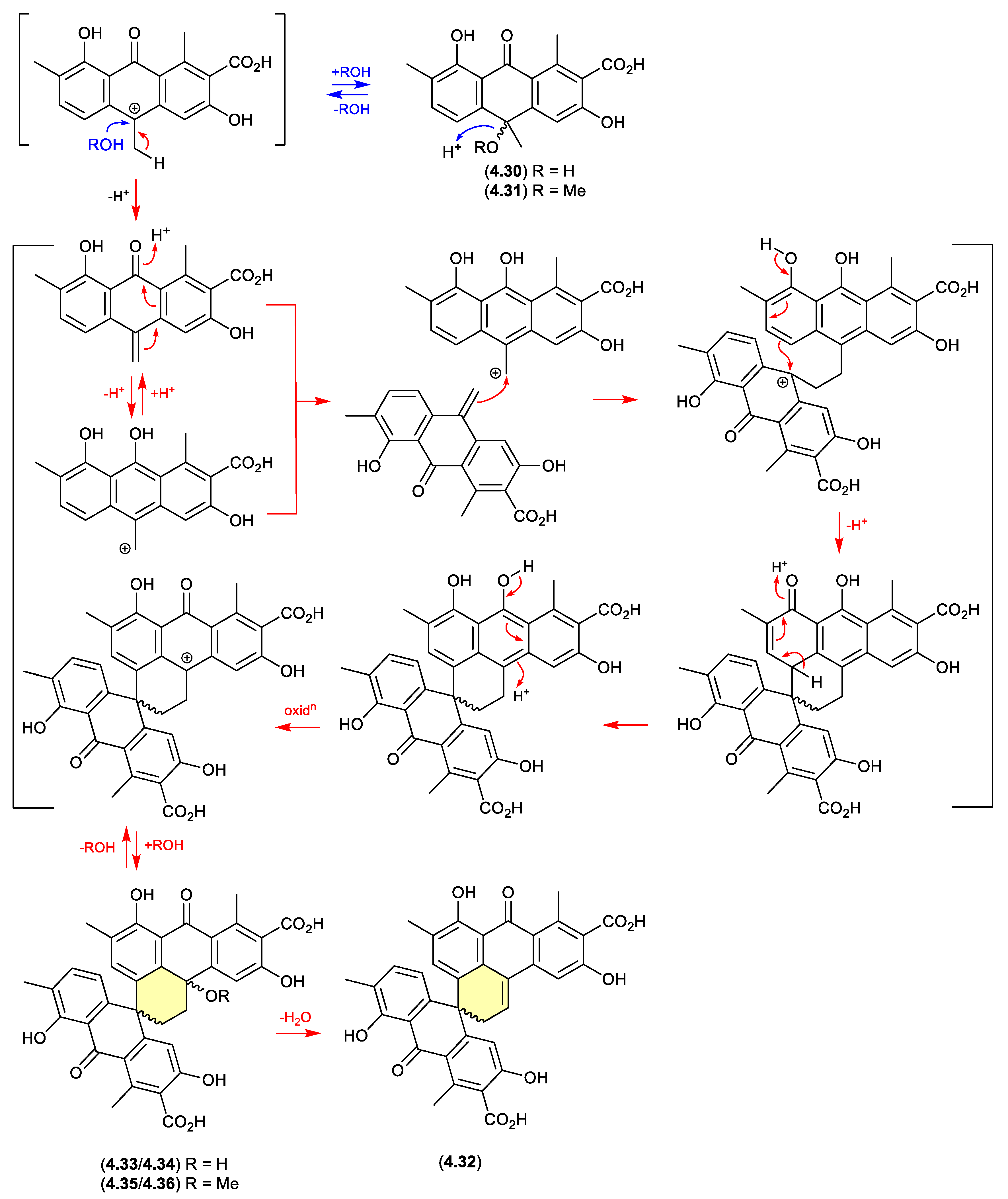

oxanthromicins/eurotones (Figure 4.2.4 and 4.2.5)

In 2014, the racemic polyketide (±)-

hemi-oxanthromicin A (

4.30), isolated from the soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. MST-134270, was shown to be unstable to acid chromatography (MeOH/H

2O with 0.1% TFA).[

85] During handling

4.30 transformed to the methanolysis adduct (±)-

hemi-oxanthromicin A (

4.31) and the dimeric (±)-

spiro-oxanthromicin A (

4.32). Formation of latter likely proceeds via the co-isolated (±)-

spiro-oxanthromicins B1/B2 (

4.33/

4.34) and C1/C2 (

4.35/

4.36), with B1/B2 (

4.33/

4.34) transforming during purification (MeOH/H

2O with 0.1% TFA) to

4.32.

Curiously, in 2019 the enantiomeric (+)-eurotone A (

4.37) and (–)-eurotone A (

4.38) and related monomer, physcion (

4.39), were reported following silica gel (CHCl

3/MeOH) fractionation of an extract prepared from the marine-derived fungus

Eurotium sp. SCSIO F452[

86] — where

4.37/

4.38 may be indicative of a chemically reactive and cryptic

hemi-quinone co-metabolite akin to

4.33/4.34.

4.3. Silica Gel

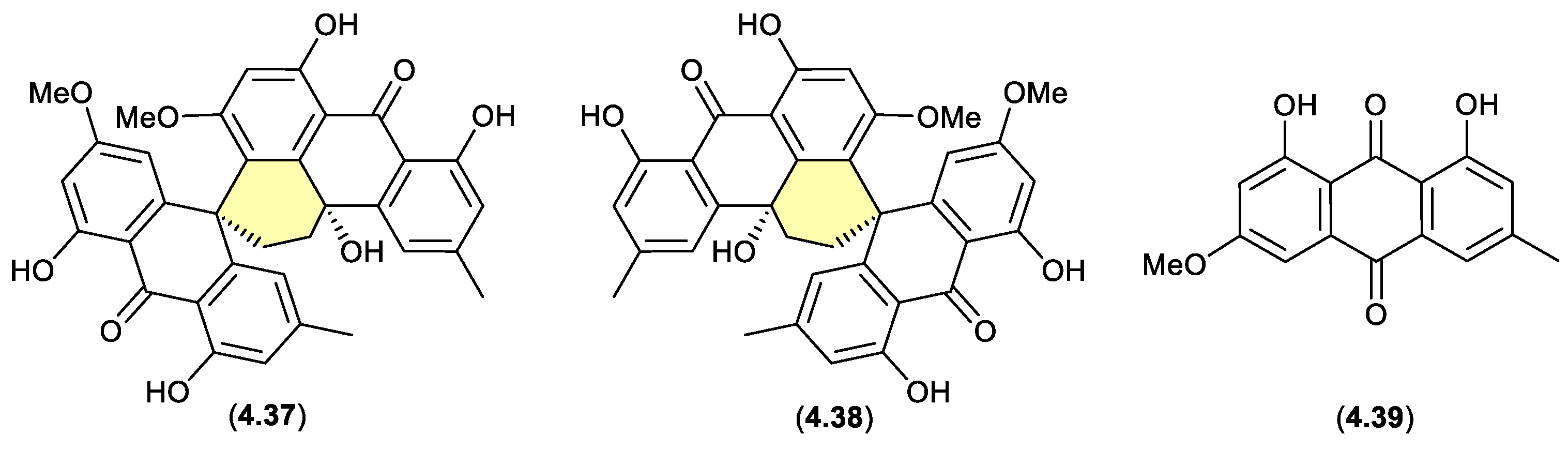

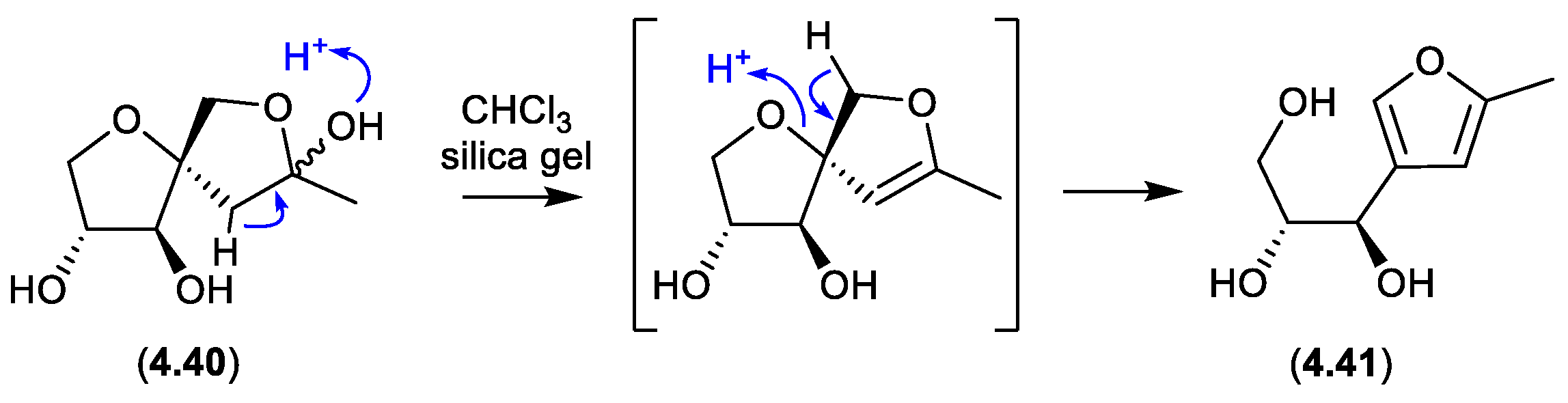

sphydrofurans (Figure 4.3.1)

On exposure to silica gel chromatography (CHCl

3/MeOH), the

Streptomyces metabolite sphydrofuran (

4.40) transforms to the furan artifact (

4.41).[

87]

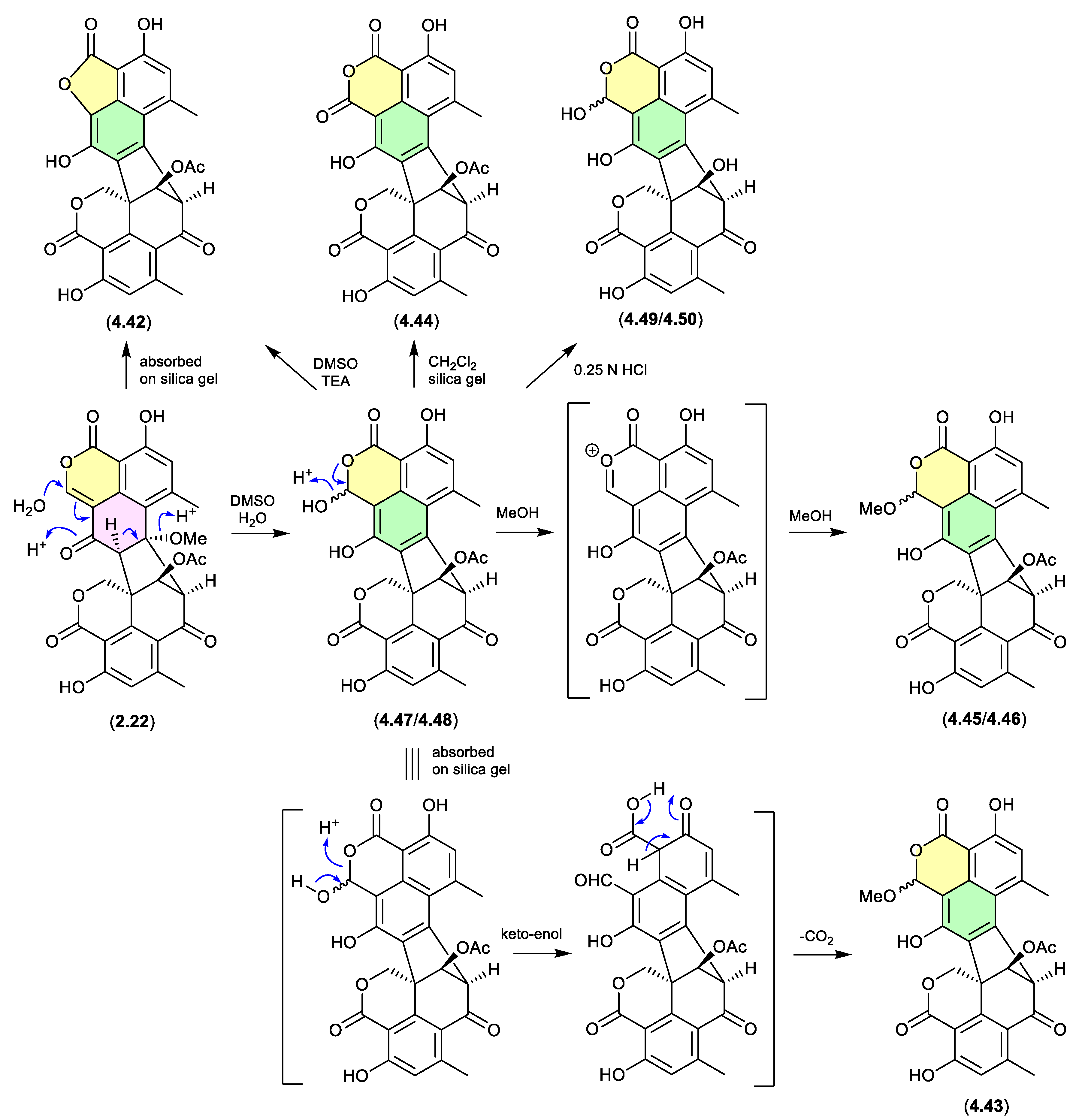

duclauxin/bacillisporins/xenoclauxin/talaromycesone B (Figure 4.3.2 and 4.3.3)

Since the polyketide duclauxin (

2.22) was first reported in 1965 from

Penicillium duclauxii,[

88] in excess of 50 analogues have been reported as natural products from both terrestrial and marine fungi of the genera

Penicillium and

Talaromyces — many with a wide range of promising biological properties. Over the course of these studies it has been noted/speculated that some duclauxin-

like natural products (co-metabolites of

2.22) may be handling artifacts. Recent investigations into the Mexican soil-derived

Talaromyces sp. IQ-313,[

48] examined duclauxin (

2.22) and the artifact status of the known natural products, talaromycesone B (

4.42), bacillisporin G (

4.43), xenoclauxin (

4.44), and bacillisporins F (

4.45/

4.46), J (

4.47/

4.48) and I (

4.49/

4.50). For example, a solution of

2.22 in DMSO/H

2O transformed over 24 h to the acetal epimer bacillisporins J (

4.47/

4.48), which on dissolution in MeOH underwent spontaneous transformation to bacillisporins F (

4.45/

4.46). Similarly,

2.22 adsorbed on silica gel transformed to talaromycesone B (

4.42); a mixture of

2.22 and

4.47/

4.48 adsorbed on silica gel transformed to bacillisporin G (

4.43); a CH

2Cl

2 suspension of bacillisporins J (

4.47/

4.48) on silica gel generated xenoclauxin (

4.44); and exposure of

4.47/

4.48 to mild acid (0.25 N HCl) effected hydrolysis of the acetate moiety to yield bacillisporins I (

4.49/

4.50). These studies supported the view that other members of the duclauxin family of natural product are also handling artifacts, including the marine-derived fungal verruculosins (see

Section 2.5, duclauxin/verruculosins)[

49] and adpressins B–F,[

89] and terrestrial-derived fungal talaroketals A and B,[

90] talaroclauxins A and B,[

91] macrosporusones A–C,[

92] and bacillisporones A, B, D and E.[

93]

Duclauxin (

2.22) has also been shown to react rapidly (

in situ during cultivation, or extraction – see comment below) with various biogenetically available amines to produce lactams, including with, (i) amino acids to yield the talauxins,[

94] (ii) ethanolamine and g-aminobutyric acids to yield duclauxamides[

95,

96] and talaroclauxins,[

91] and (iii) deoxyaminosugars to yield glyclauxins.[

18] While there is no evidence to suggest that these lactams are artifacts, their natural products status does raise an interesting possibility. If the fungus only produces duclauxin (

2.22), and it is only during solvent extraction that

2.22 is released from the mycelia and comes into contact with biogenic amines present in the culture media — the resulting lactams could be better described as artifacts, as they only come into existence at the point of solvent extraction. This very scenario was encountered in the case of the prolinimines (see Section 10.1).

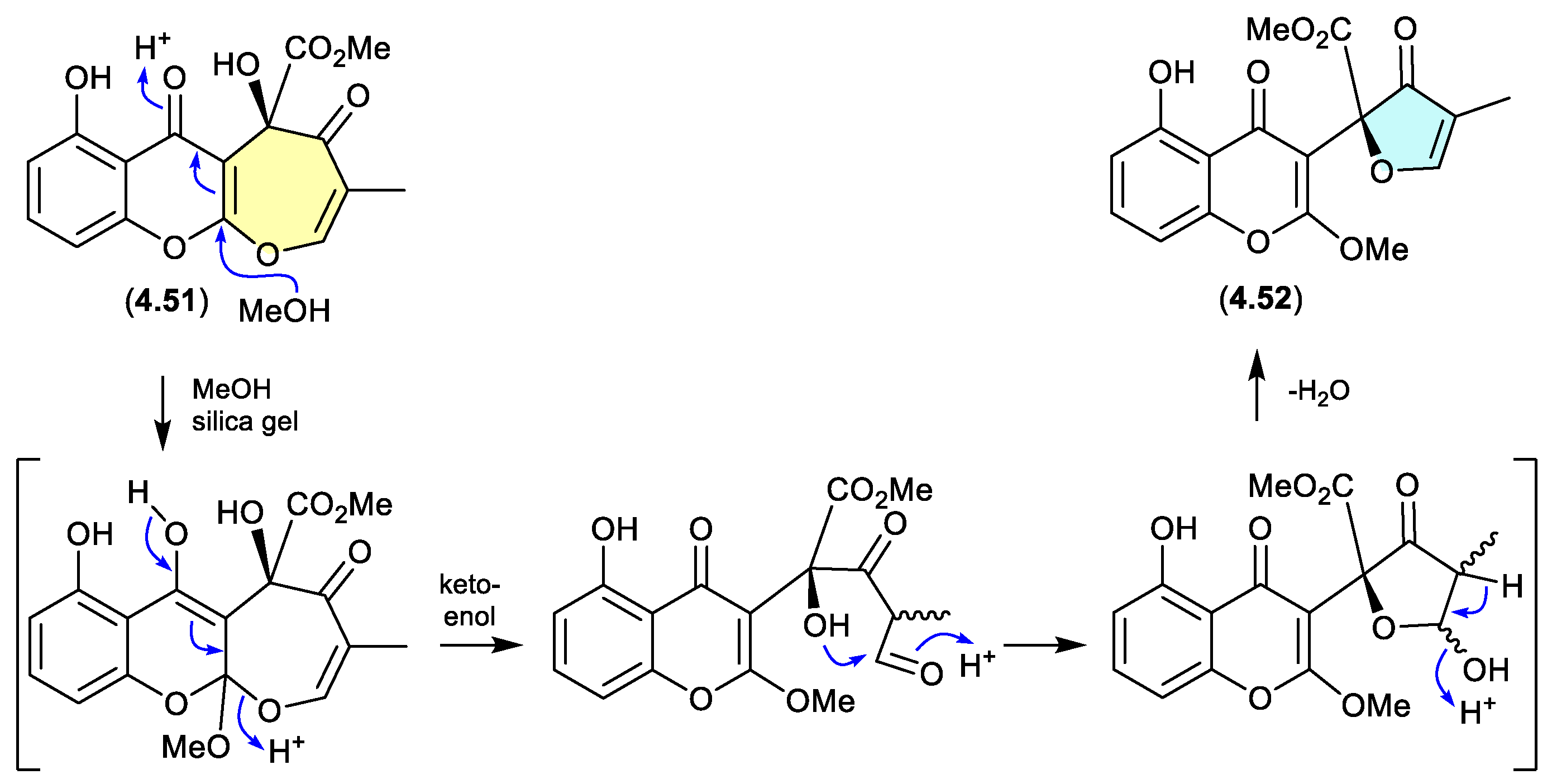

xanthepinone (Figure 4.3.4)

The chromone

4.51 recovered from the wood-decay fungus

Rhizina sp. BCC 12292 was found to be a ring-contracted artifact, induced by silica gel chromatography (MeOH/CH

2Cl

2) of the known co-metabolite xanthepinone (

4.52).[

97]

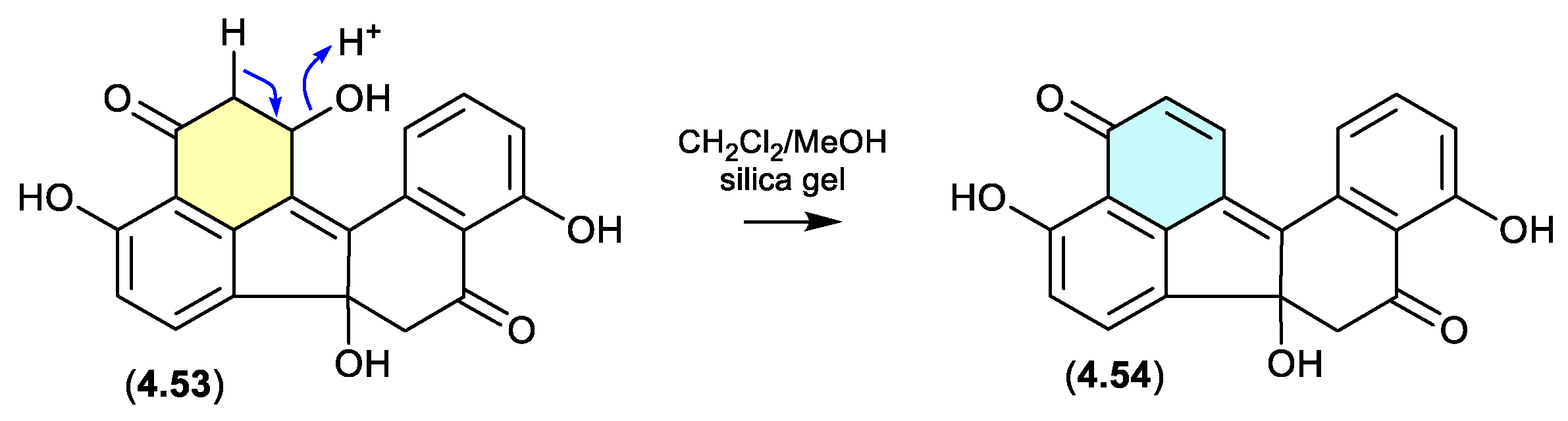

daldinones (Figure 4.3.5)

Daldinone H (

4.53) isolated from the Cameroon mangrove plant-derived fungus

Annulohypoxylon sp., underwent rapid dehydration on exposure to silica gel chromatography (CH

2Cl

2/MeOH) to the artifact daldinone I (

4.54).[

98]

5. Light

Many natural products are sensitive to sunlight, and it is advisable to minimise exposure to direct sunlight and store them longer term in the dark.

5.1. Photoisomerization

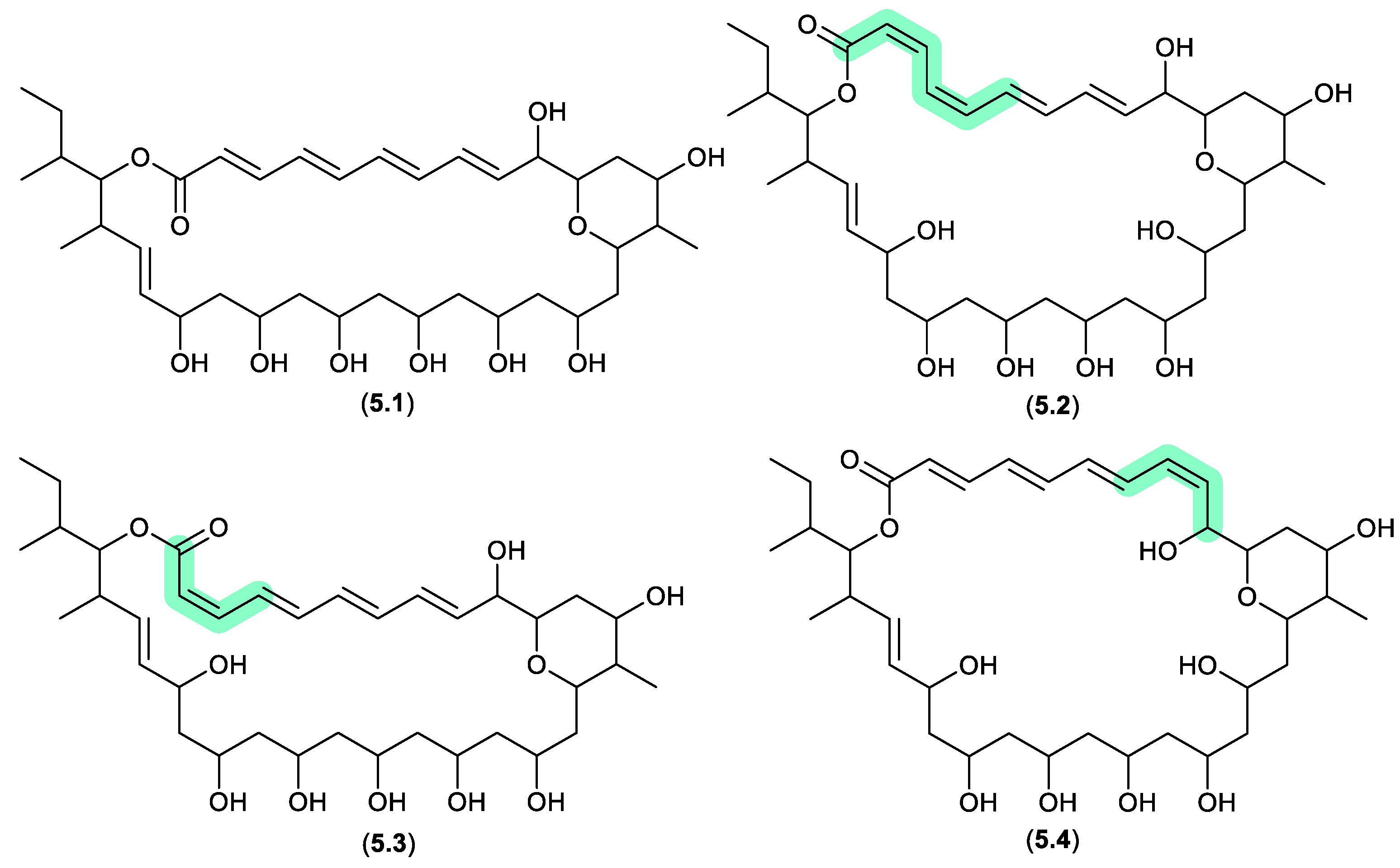

pyranpolyenolides (Figure 5.1.1)

The South China Sea sediment-derived

Streptomyces sp. MS110128 yielded two new polyene macrolides that were prone to photoisomerization. For example, after only 5 h exposure to natural light, pyranpolyenolide B (

5.1) underwent double bond isomerisation to pyranpolyenolides D (

5.2), E (

5.3) and F (

5.4).[

99]

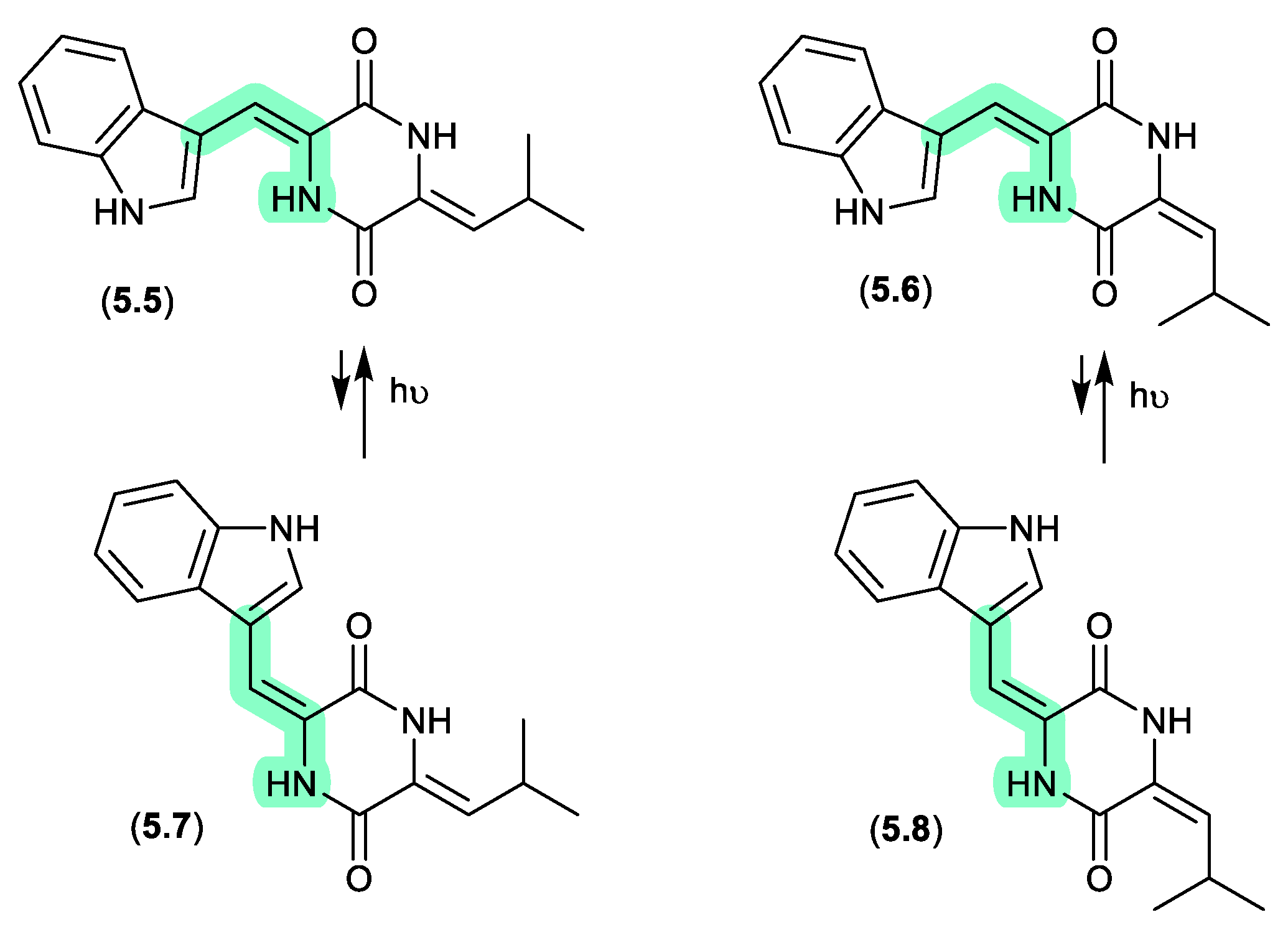

photopiperazines (Figure 5.1.2)

A Californian marine sponge-derived actinomycete (strain AJS-327) yielded four isomeric diketopiperazines, photopiperazines A–D (

5.5–

5.8), that were prone to photoisomerization.[

100] For example, following HPLC purification, and even where care was taken to handle samples under dim light conditions,

5.5 equilibrated to a 1:0.2 ratio with

5.7. The same was also observed for

5.6 and

5.8. On exposure to long wavelength UV (365 nm) for 2 h this ratio adjusted to 1:1.3; however, when stored under room lighting for 6 h the mixture re-equilibrated to the original ratio. Significantly, photoisomerization was restricted to the double bond associated with the Trp, but not the Leu moiety.

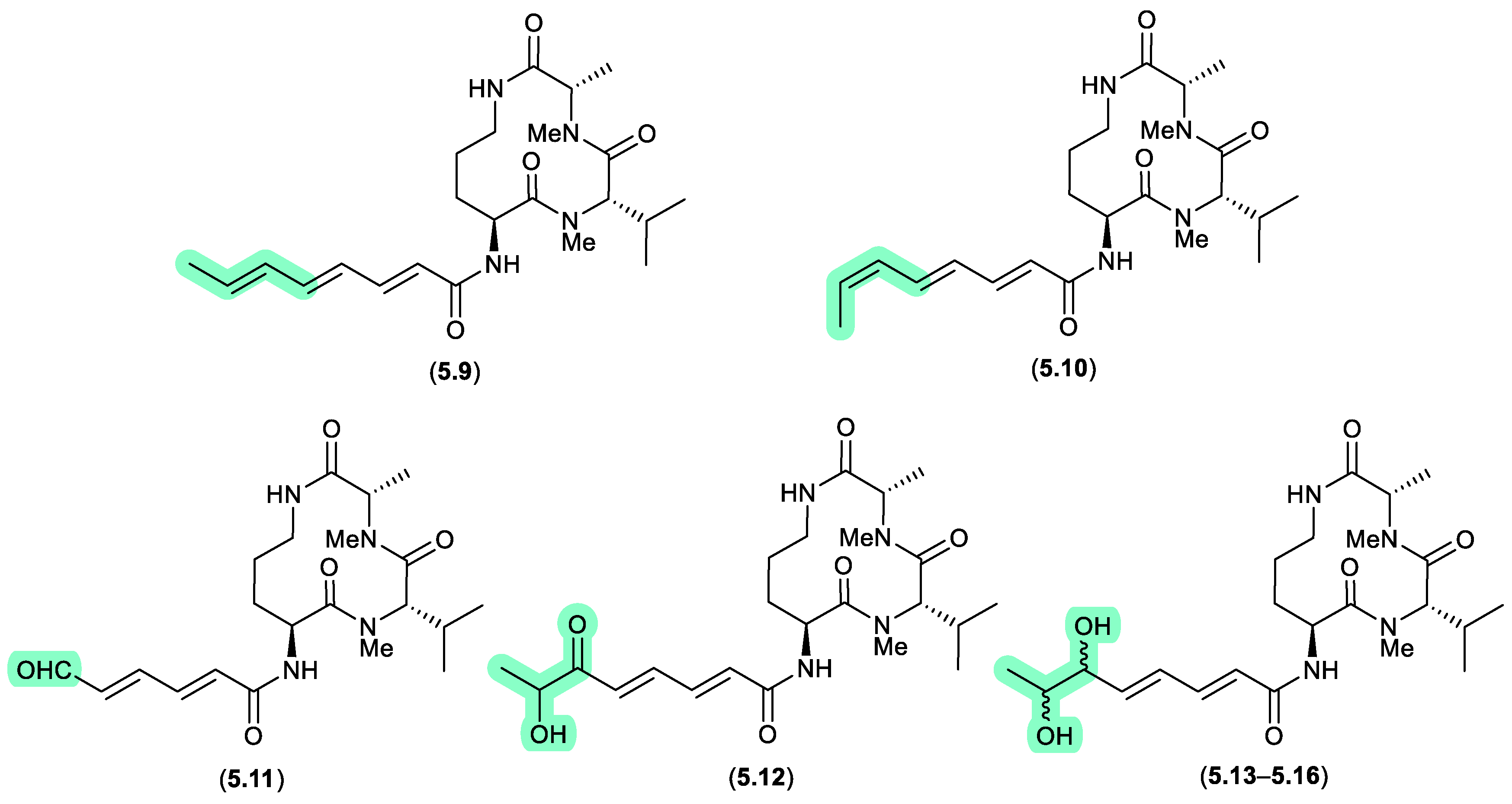

aspochracins/sclerotiolides (Figure 5.1.3)

The halotolerant fungus,

Aspergillus sclerotiorum PT06-1 isolated from salt sediments collected from the Putian Sea Salt Field, Fujian, China, yielded an array of cyclic tripeptides prone to photoisomerism and oxidation.[

101] For example, when exposed to daylight and air for 1 d, a MeOH/H

2O solution of the known cyclic tripeptide aspochracin (

5.9) underwent isomerisation to sclerotiolide E (

5.10), and when extended to 10 d, yielded sclerotiolides F–J (

5.11–

5.16).

clavosines/calyculins (Figure 5.1.4)

A sample of marine sponge

Myriastra clavosa collected from Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, yielded clavosines A–C (

5.17–

5.19) as potent cytotoxins and inhibitors of Protein Phosphatase 1 and 2A, of which clavosine C (

5.19) is a photoisomerization artifact of clavosine B (

5.18).[

102] Similar issues arose in the case of the structurally related calyculins A–H (

5.20–

5.27), where it has been suggested all but calyculins A and C (

5.20 and

5.22) may be photoisomerization artifacts.[

103]

5.2. Photooxidation

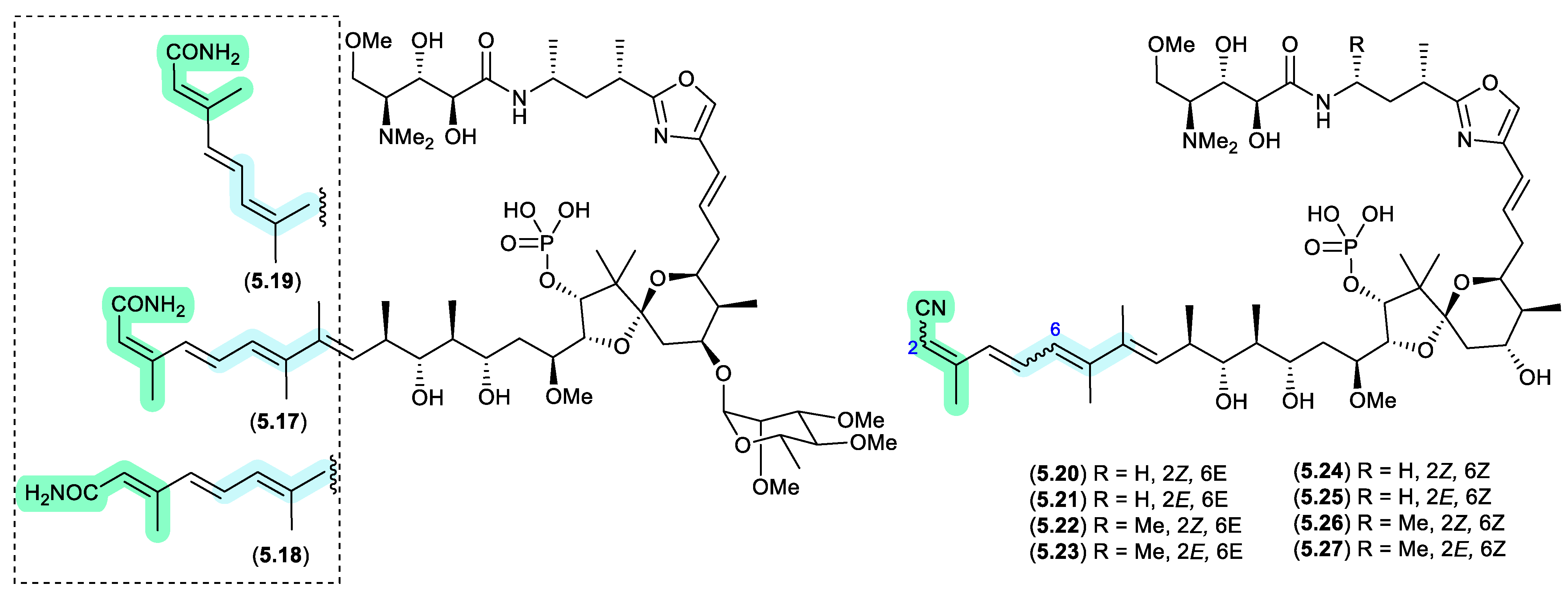

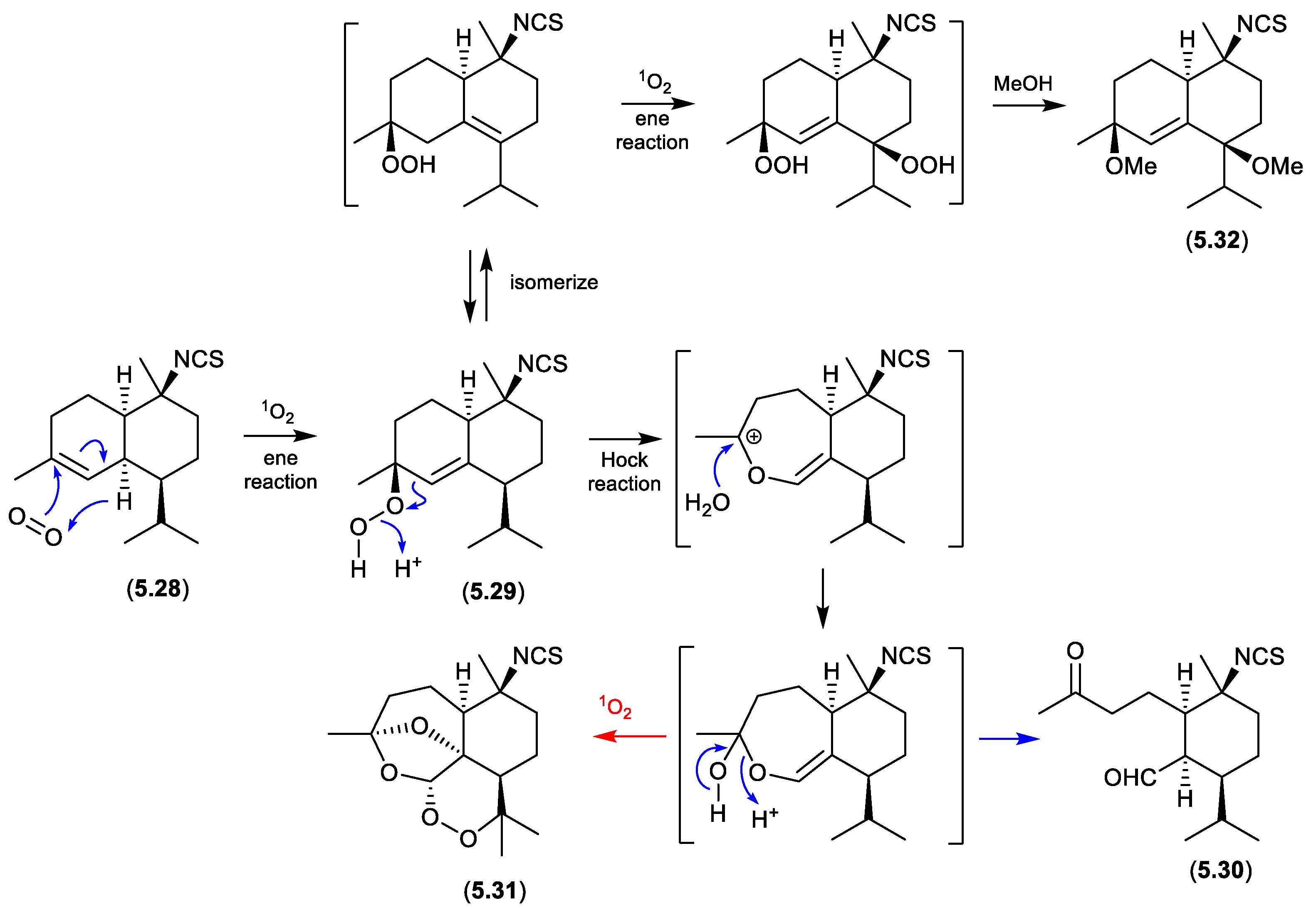

cadinanes (Figure 5.2.1)

Marine and microbial extracts can be rich in pigments, which could in principle act as photosensitisers, leading to photooxidation artifacts. In an interesting study, Tanaka et al noted “

We have observed that a neighboring natural products laboratory often isolated molecules with a hydroperoxide moiety, while we have rarely isolated molecules with this functionality. One difference between the two labs is their orientation, with our lab facing north and the neighboring lab facing south. It was therefore suspected that isolation of hydroperoxide molecules could be affected by sunlight coming through windows during laboratory procedures.”[

104] To test this hypothesis, separate acetone, MeCN and MeOH solutions of an isothiocyanate sesquiterpene, cadinane (

5.28), and the photosensitiser Rose Bengal, were allowed to stand at r.t. for two weeks exposed to sunlight through the laboratory window. The acetone solution yielded

5.29 and

5.30, while MeCN yielded

5.30, and MeOH

5.31 and

5.32. Not only did this study demonstrate the potential for photooxidations, but it also highlighted that artifact pathways can be solvent dependent.

5.3. Photoreactivity

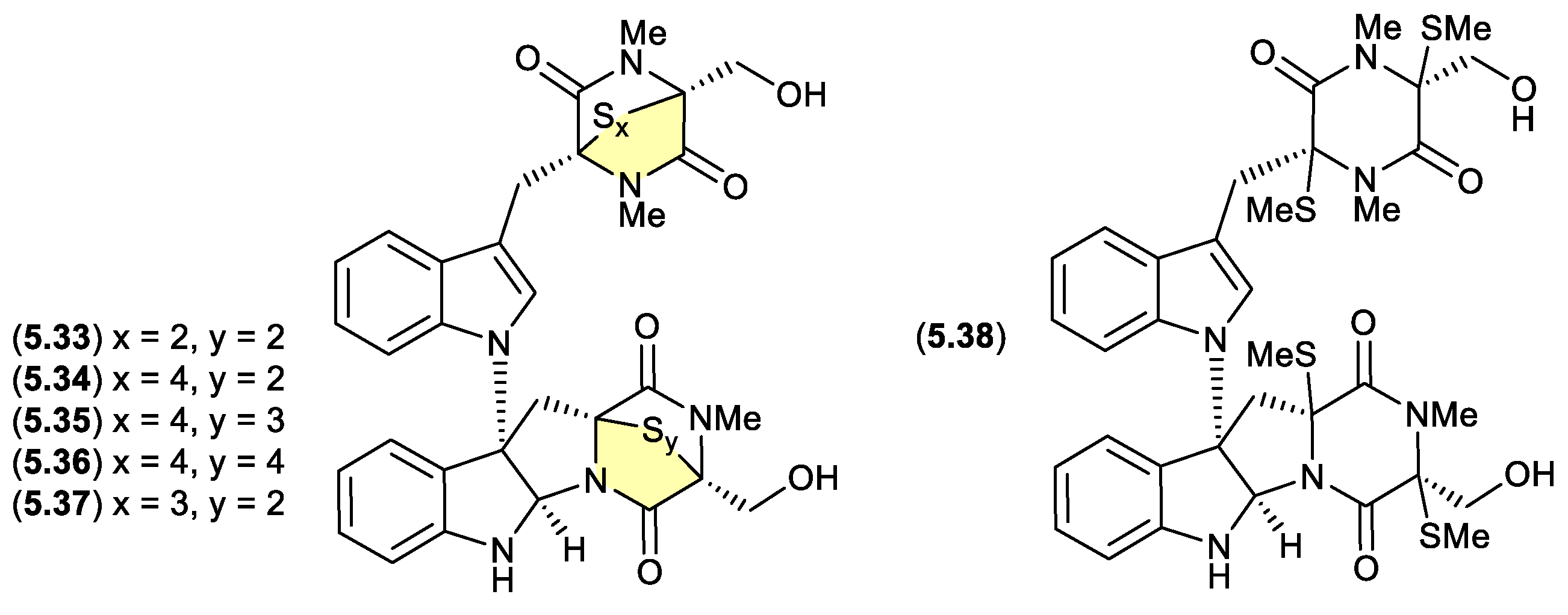

chetomins (Figure 5.3.1)

Chetomin (

5.33) was first isolated in 1944 by Wakeman et al from the fungus

Chaetomium cochliodes, and exhibits strong cytotoxicity via the transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1).[

105] Building on this rare structure class, in 2018 Zou et al reported an investigation of a

C. cochliodes type strain (CGMCC3.17123), which yielded both

5.33 and the new chetomins A–D (

5.34–

5.37) and dethio-tetra (methylthio) chetomin (

5.38).[

106] As

5.33–

5.38 proved to be photosensitive, isolation, characterisation and structure elucidation was achieved in darkness. Once isolated, controlled exposure to light indicated a high degree of interconversion between

5.33–

5.37, with sulphur heterocycles both enlarging and contracting.

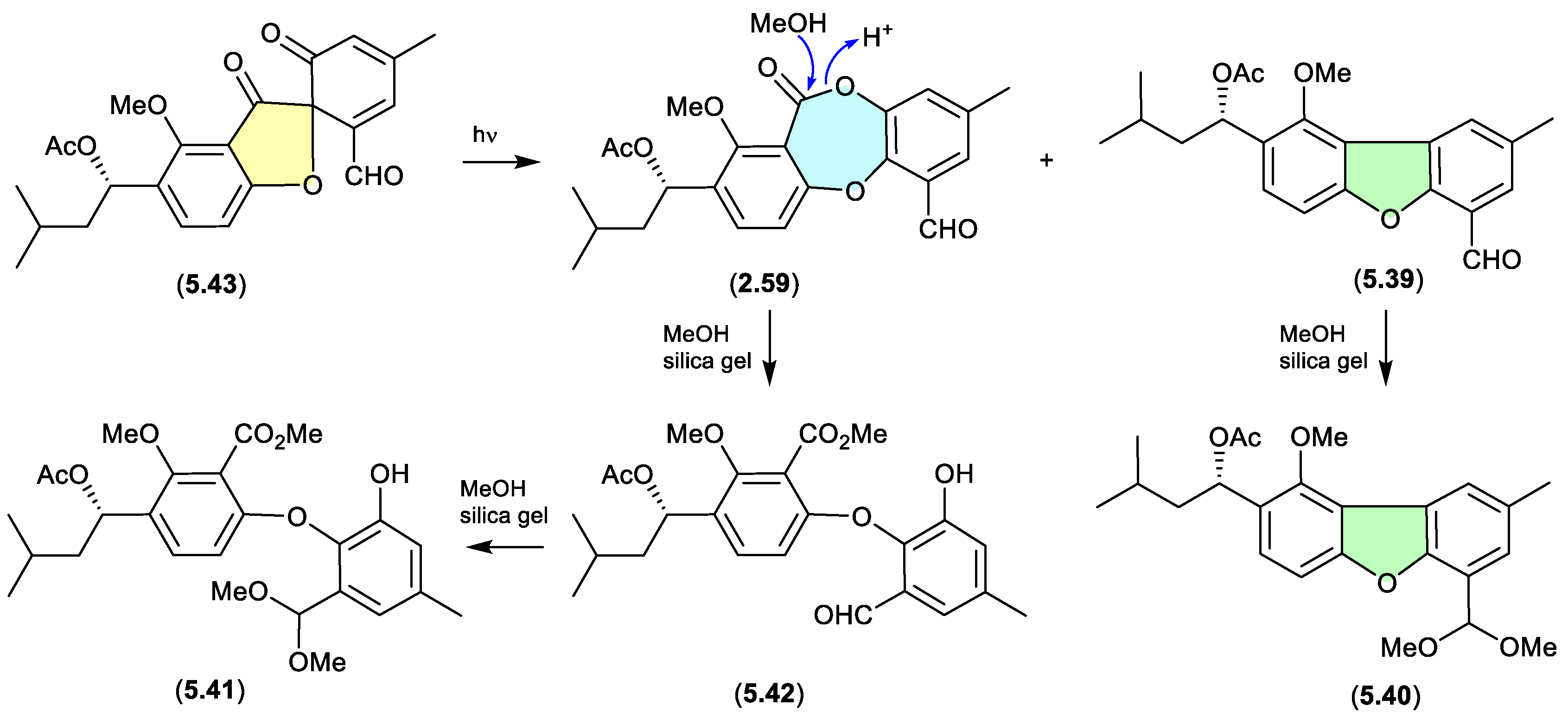

talaromycins/purpactins (Figure 5.3.2)

The South China Sea gorgonian-derived fungus

Talaromyces sp. yielded the new diphenyl ether talaromycins A–C (

5.39–

5.41), along with several known natural products, including tenellic acid A methyl ester (

5.42), purpactin C (

5.43) and C′ (

2.59).[

31] Interestingly,

5.43 transformed under daylight to

2.59 and

5.39. Similarly, the extensive use of silica gel (CH

2Cl

2/MeOH) chromatography likely facilitated transformation (methanolysis) of the lactone ring in

2.59 to the

seco methyl ester

5.42, and the benzaldehydes

5.39 and

5.42, to the dimethyl acetals

5.40 and

5.41, respectively (see

Section 2.3). Hence, the combination of both sunlight and the use of silica gel suggests that talaromycins A–C (

5.39–

5.41), tenellic acid A methyl ester (

5.42) and purpactin C′ (

2.59) are likely artifacts.

6. Air Oxidation

Many functional groups are prone to air oxidation, including phenols, hydroquinones, alkenes and alcohols. In many cases these oxidation artifacts can be readily predicted, and through cautious laboratory handing, be minimised or even avoided. Air oxidation can also initiate transformations that are less intuitive, potentially leading to artifacts that risk going unnoticed and mischaracterised as natural products.

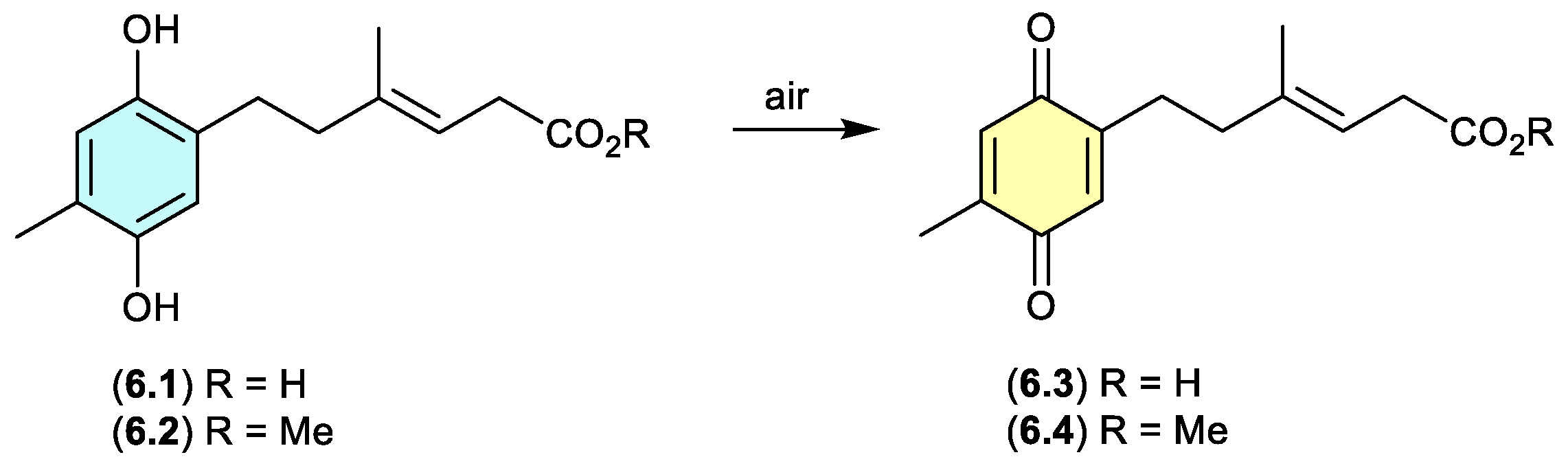

ketidocillinones (Figure 6.1)

On exposure to air, the antibacterial polyketide ketidocillinones A (

6.1) and B (

6.2), isolated from the Antarctic sponge-derived fungus

Penicillium sp. HDN151272, slowly oxidised to the corresponding quinones

6.3 and

6.4, respectively.[

107] This is a common transformation among natural products that feature a hydroquinone moiety.

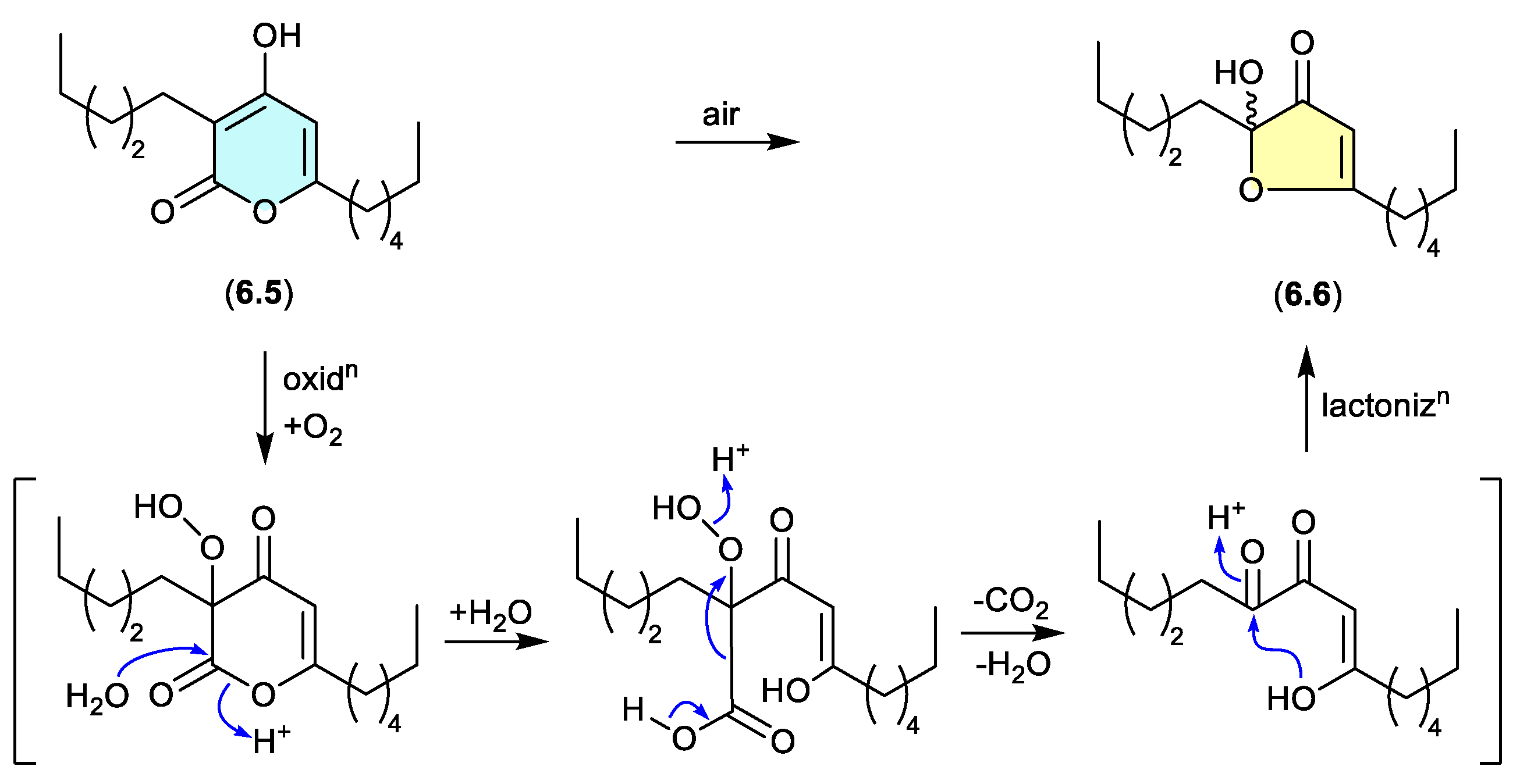

pseudopyronines (Figure 6.2)

The polyketide a-pyrone, pseudopyronine B (

6.5), isolated from a Fijian marine sponge-derived

Pseudomonas sp. F92S91, undergoes oxidative transformation during handling to the furanone

6.6.[

108] A key characteristic of this transformation is the racemic nature of the acetal-furanone moiety, and a plausible mechanism proceeds via autoxidation, hydrolysis, decarboxylation/dehydration and lactonisation (as indicated).

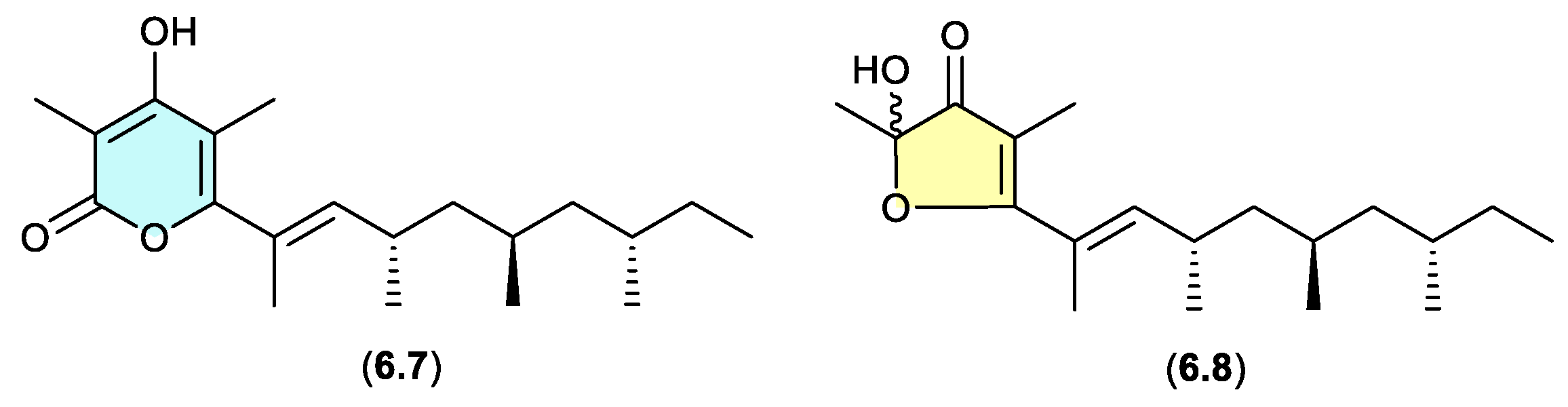

norpectinatone (Figure 6.3)

Natural products featuring the acetal-furanone moiety, as in

6.6, are relatively rare in the scientific literature, and typically co-occur with the corresponding a-pyrones (e.g.

6.5), which is suggestive of an artifact relationship. A clear example is seen with the polyketide a-pyrone norpectinatone (

6.7) and ketal-furanone

6.8 recovered from a Chilean collection of the pulmonated mollusc

Siphonaria lessonii[109] — the latter potentially an artifact of the former.

linfuranones/hyafurones/aurafurones (Figure 6.4)

On other occasions, aggressive cultivation and/or isolation conditions may induce the oxidative biotransformation of a prospective (un-isolated) precursor a-pyrones such that only the acetal-furanones are isolated. For example, silica gel fractionation (see

Section 4) of extracts prepared from shaken broth (aerated!) cultivations of the actinomycete

Sphaermonospora mesophila GMKU 363 yielded linfuranones [e.g. linfuranone A (

6.9)],[

110,

111] while the myxobacterium

Hyalangium minutum yielded hyafurones [e.g. hyafurone A

1 (

6.10)].[

112] Biosynthetic studies into the closely related myxobacteria aurafurones [e.g. aurafuron A (

6.11)] provided valuable insights, but did not exclude the possibility of post-translational artifact formation as noted above.[

113]

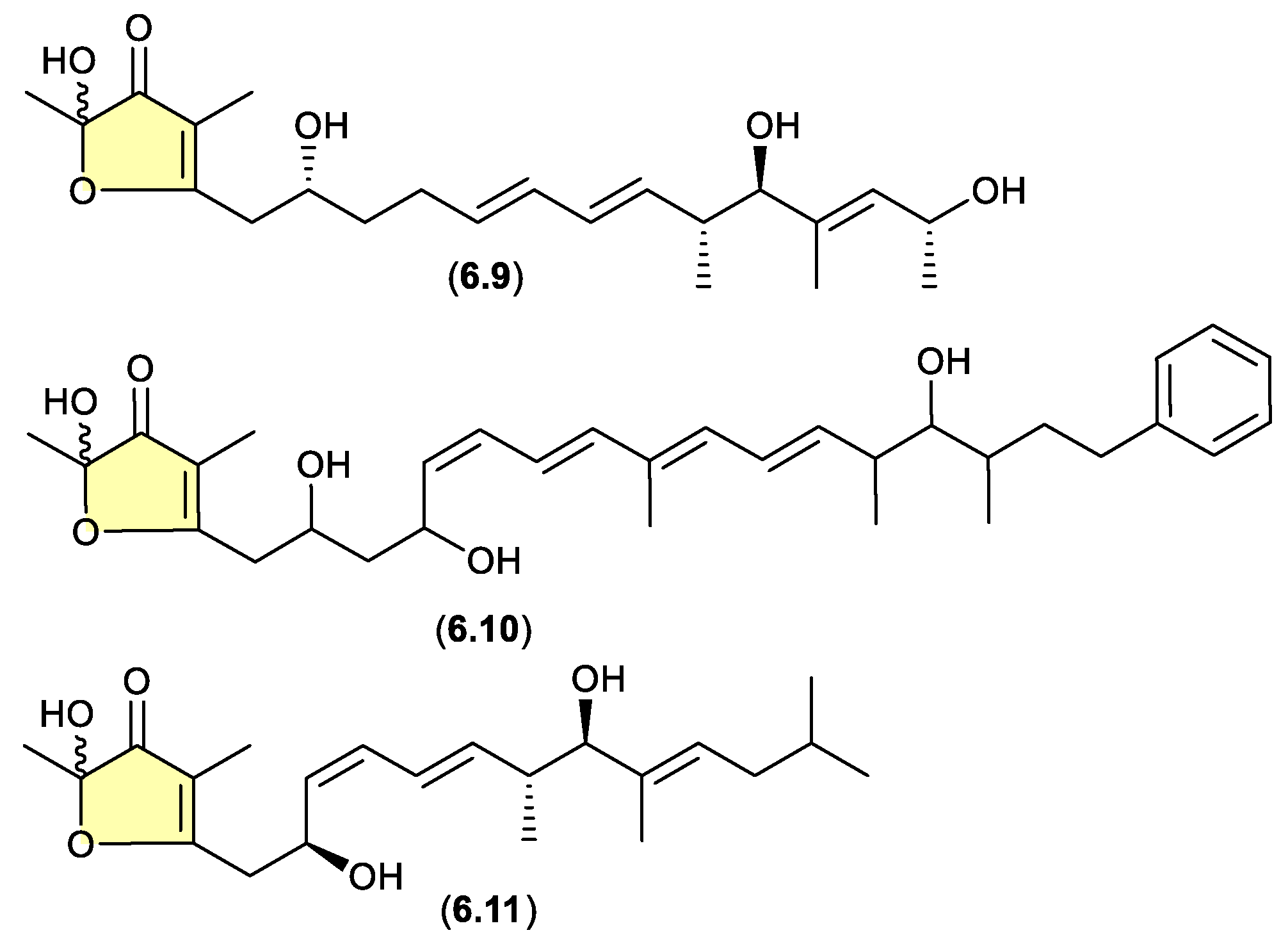

avermectins (Figure 6.5)

Prolonged (multi-year) storage of solid samples of technical abamectin (typically a mixture of avermectin B1a (

6.12) and minor avermectins), even under refrigeration and without exposure to light, resulted in oxidative transformation (up to 34%) to the remarkably stable and chiral peroxide

6.13.[

114]

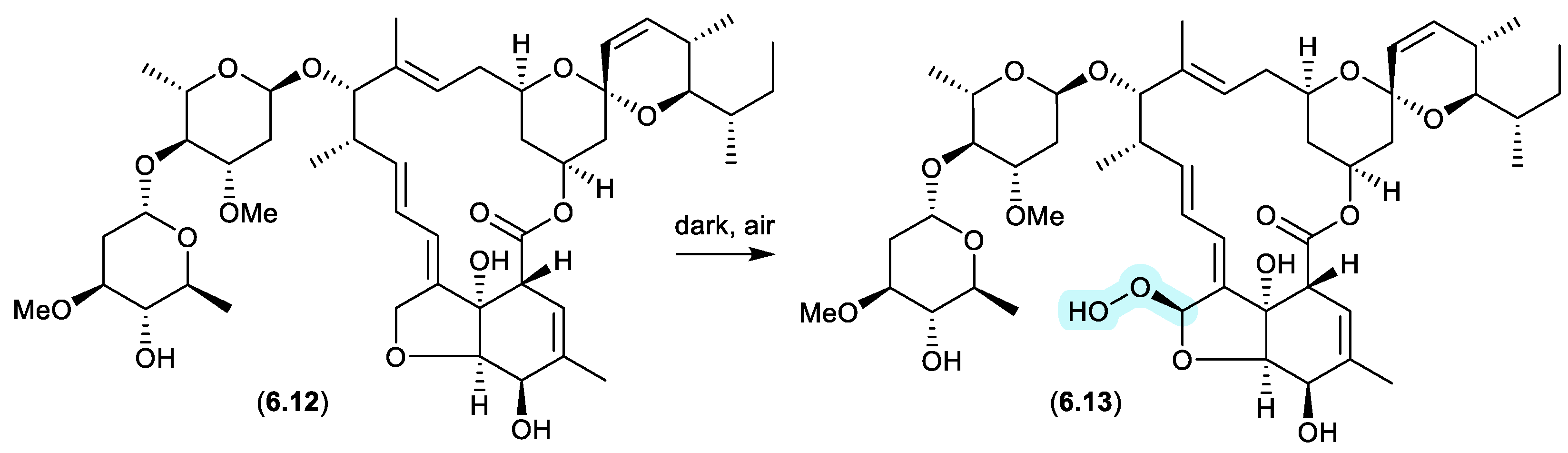

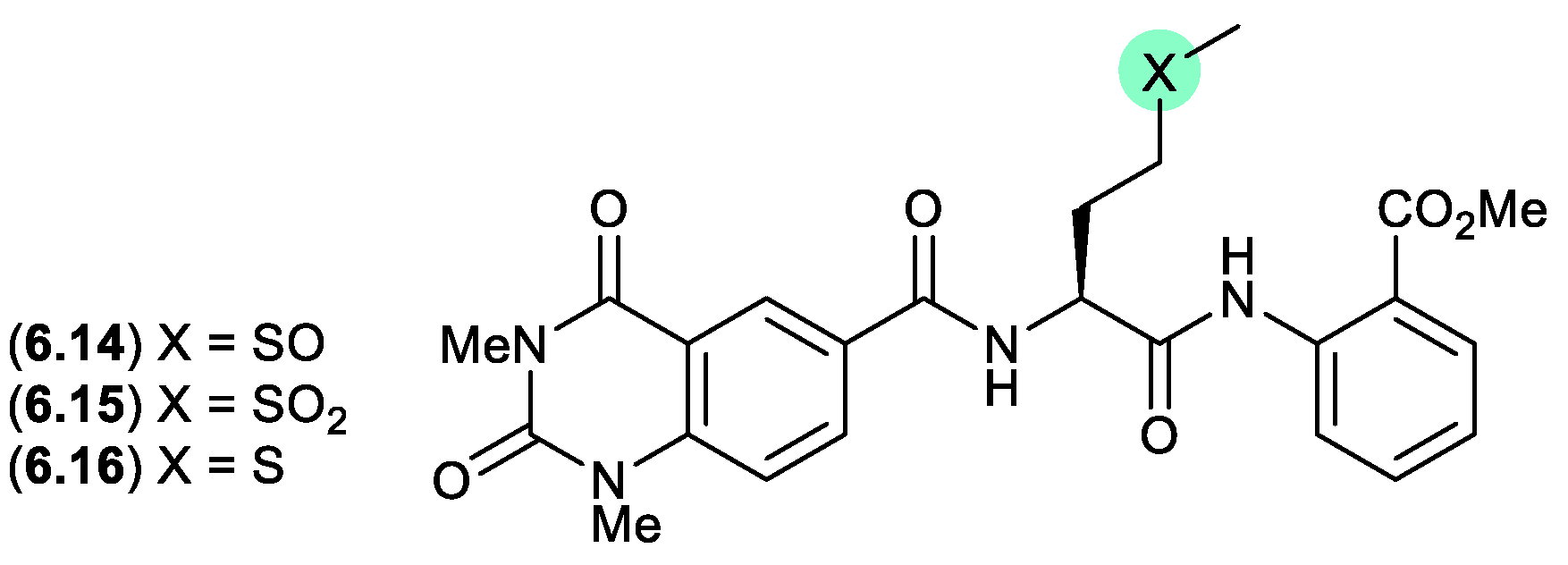

penilumamides (Figure 6.6)

A lumazine-type peptide featuring an

l-methionine sulfoxide, penilumamide (

6.14), was first reported in 2010 from the marine-derived fungus

Penicillium sp. CNL-338,[

115] It was later isolated from the mangrove-derived fungus

Aspergillus sp. 33241 in 2015,[

116] and from the gorgonian-derived fungus

Aspergillus sp. XS-20090B15 in 2014.[

117] As the latter study also reported the

l-methionine sulfone penilumamide C (

6.15) as a minor co-metabolite, this prompted speculation that the true natural product may be an as yet undetected cryptic

l-methionine analogue

6.16 (see Section 10). This hypothesis was validated when careful examination of an extract of XS-20090B15, avoiding air oxidation, yielded penilumamide B (

6.16). As predicted, exposure of

6.16 to air at r.t. resulting in initial transformation to the sulfoxide

6.14, and later to the sulfone

6.15.

7. Acetal/ketal Equilibration

Not strictly a matter of artifacts, acetal/ketal equilibria — much like equilibration in protic versus non-protic solvents (see

Section 2.10) — reveals chemical reactivity that can impact on structure elucidation, as well as consideration of biosynthetic origins, SAR, and biological mechanisms of action. Many examples of acetal and ketal equilibration are relatively trivial (e.g. carbohydrate anomers), but others are less so. To illustrate this, two case studies are outlined below.

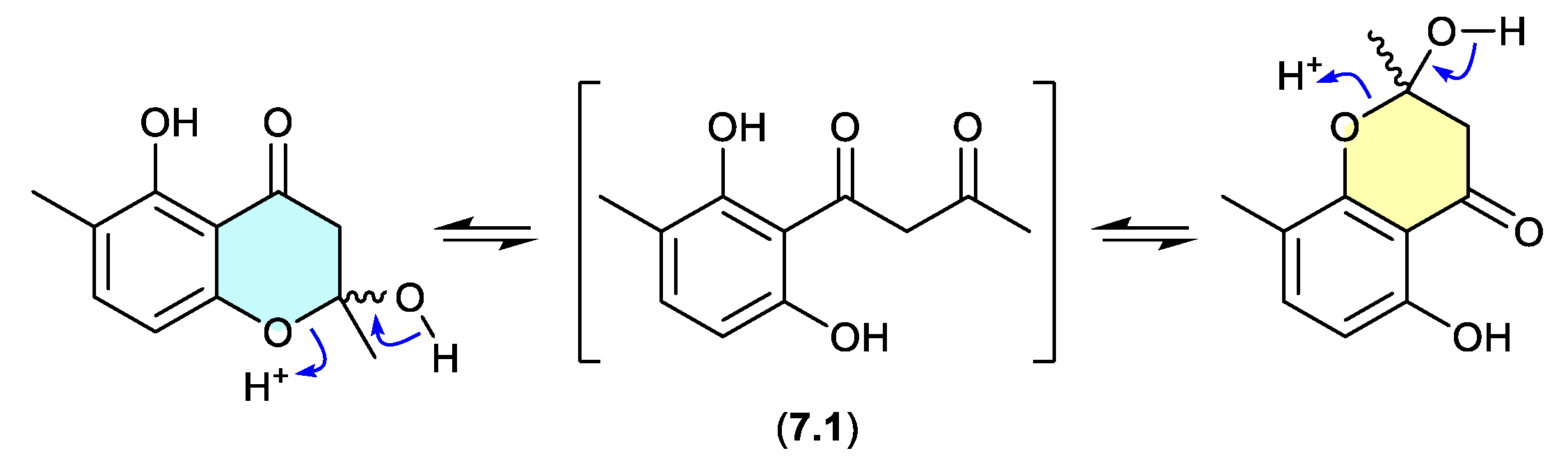

okichromanone (Figure 7.1)

Reported in 2024 from the sponge-derived actinomycete Microbispora sp., okichromanone (8.1) exists as an equilibrating mixture of two racemic ketal regioisomers.[118]

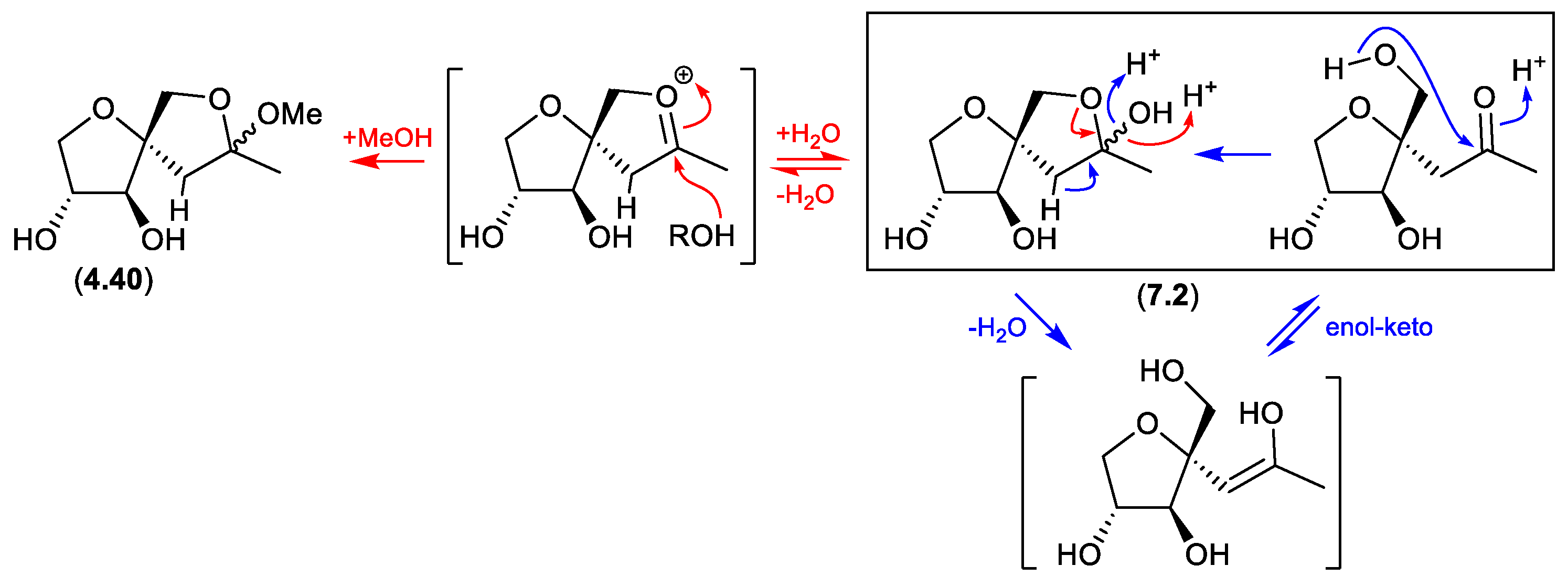

sphydrofuran (Figure 7.2)

The

Streptomyces metabolite sphydrofuran (

4.40) exists as an equilibrating mixture of ketal epimers and the ring opened ketone (

7.2), which readily convert in MeOH to a corresponding epimeric mixture of methyl ketals (

4.40).[

87]

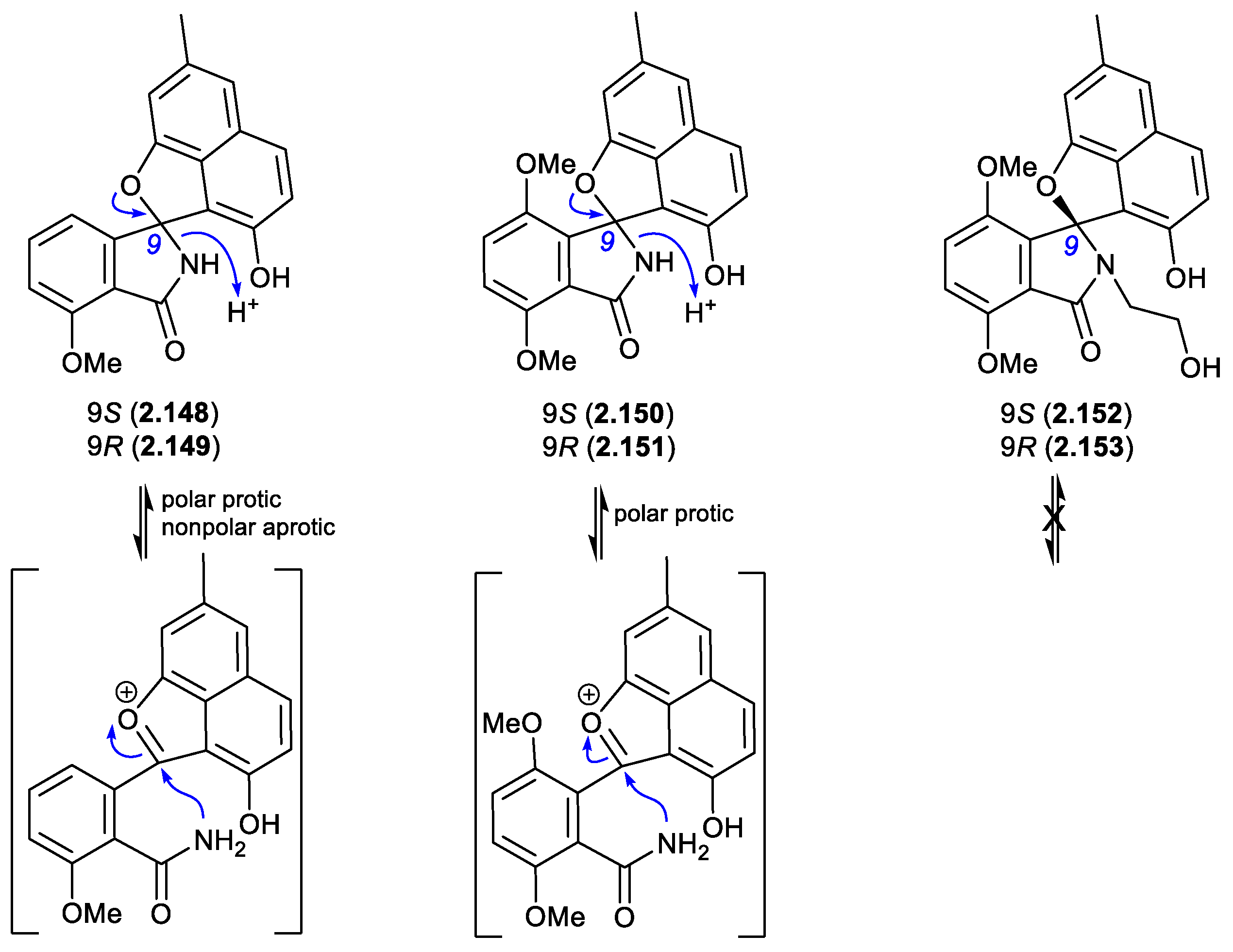

8. Trans-Esterification

During extraction, fractionation, handling and/or storage some natural product esters undergo trans-esterification. While trans-esterifications are not especially common, it is nevertheless a potential pathway to artifact formation.

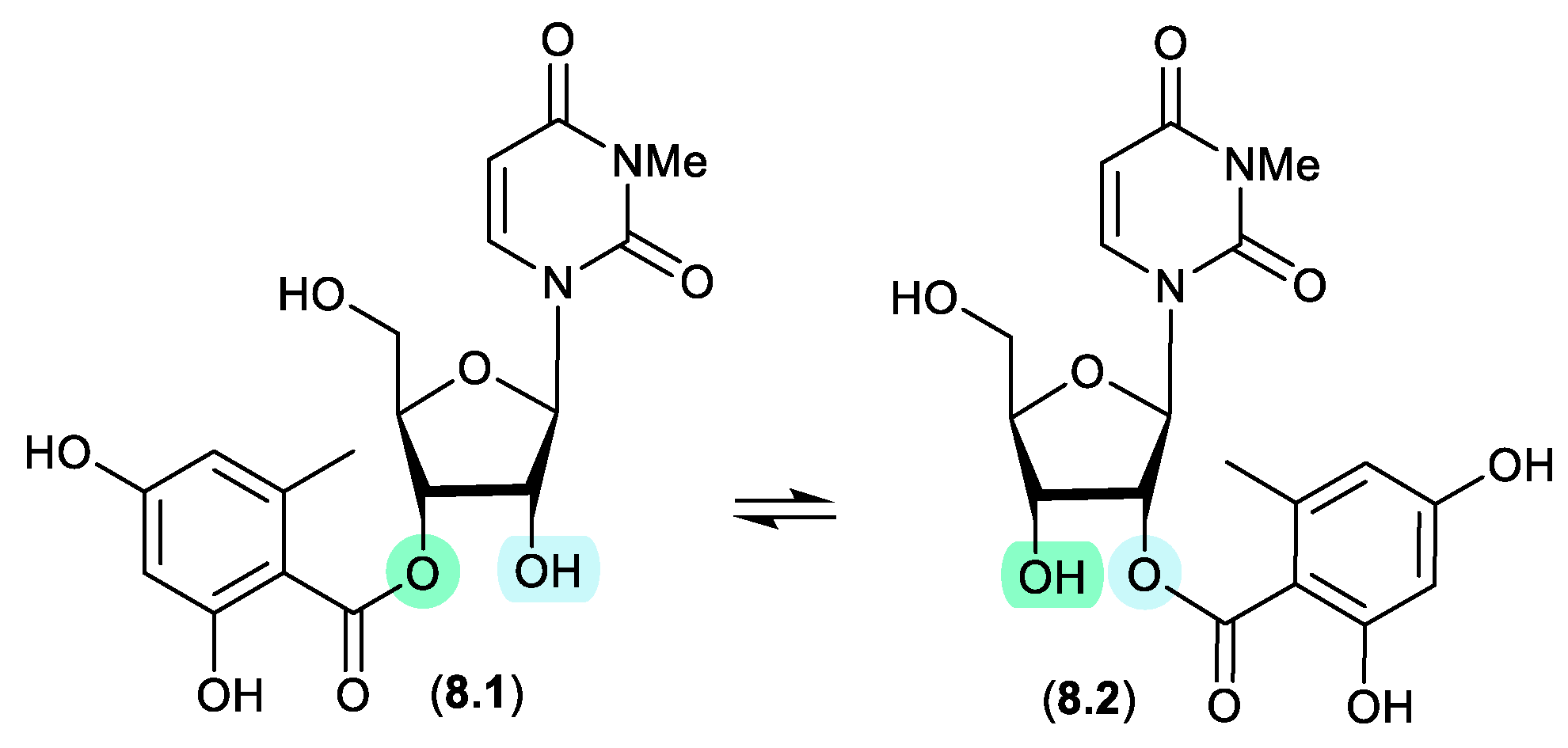

kipukasins (Figure 8.1)

The esterified nucleosides, kipukasins M (

8.1) and N (

8.2), from the marine-derived fungus

Aspergillus versicolor, exhibited a facile

trans-esterification to an equilibrating mixture of regioisomers when stored for 4 h in HPLC solvents.[

119]

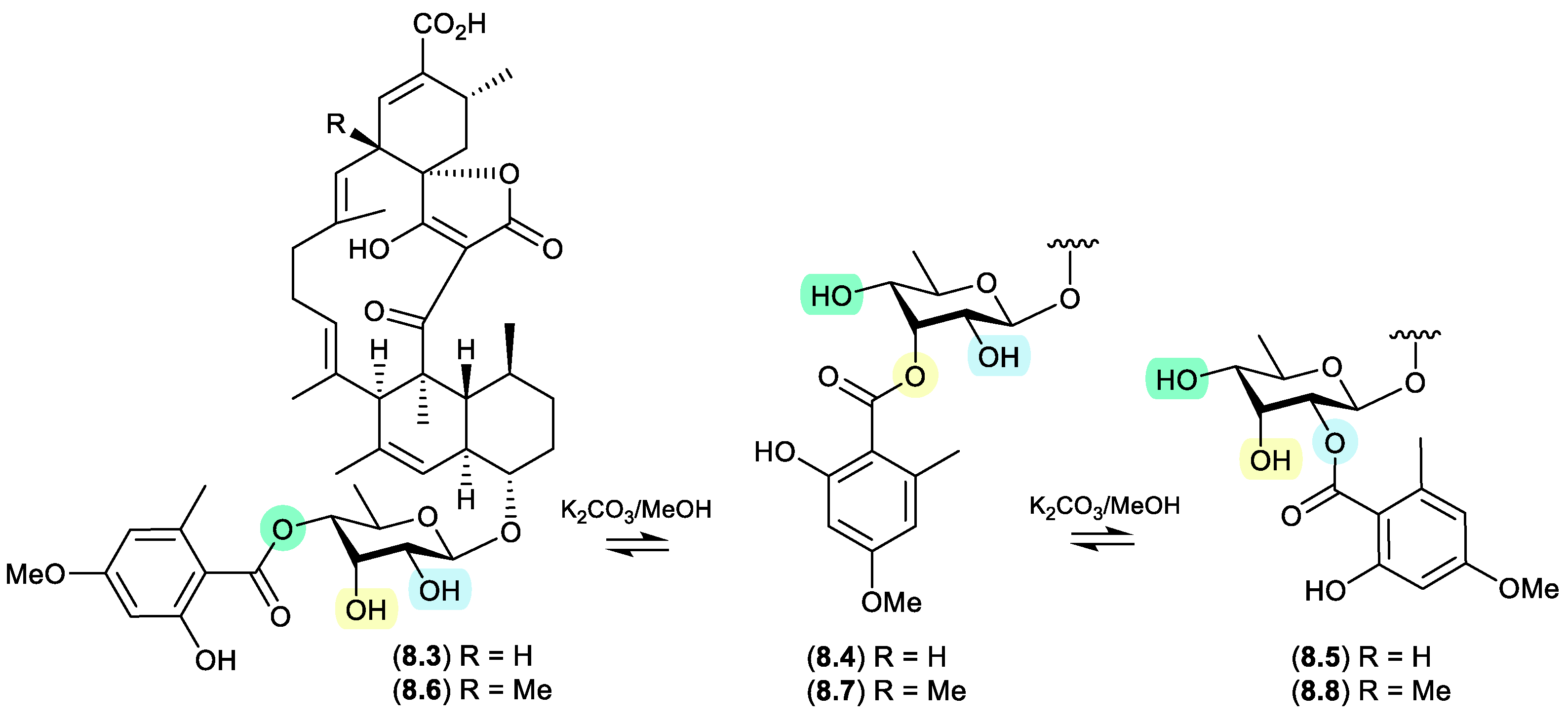

glenthmycins (Figure 8.2)

On exposure to mild base (K

2CO

3 in MeOH), a

trans-esterification was observed between

Streptomyces sp. CMB-PB041 derived glenthmycins C (

8.3), F (

8.4) and H (

8.5), and between glenthmycins E (

8.6), N (

8.7) and M (

8.8).[

120]

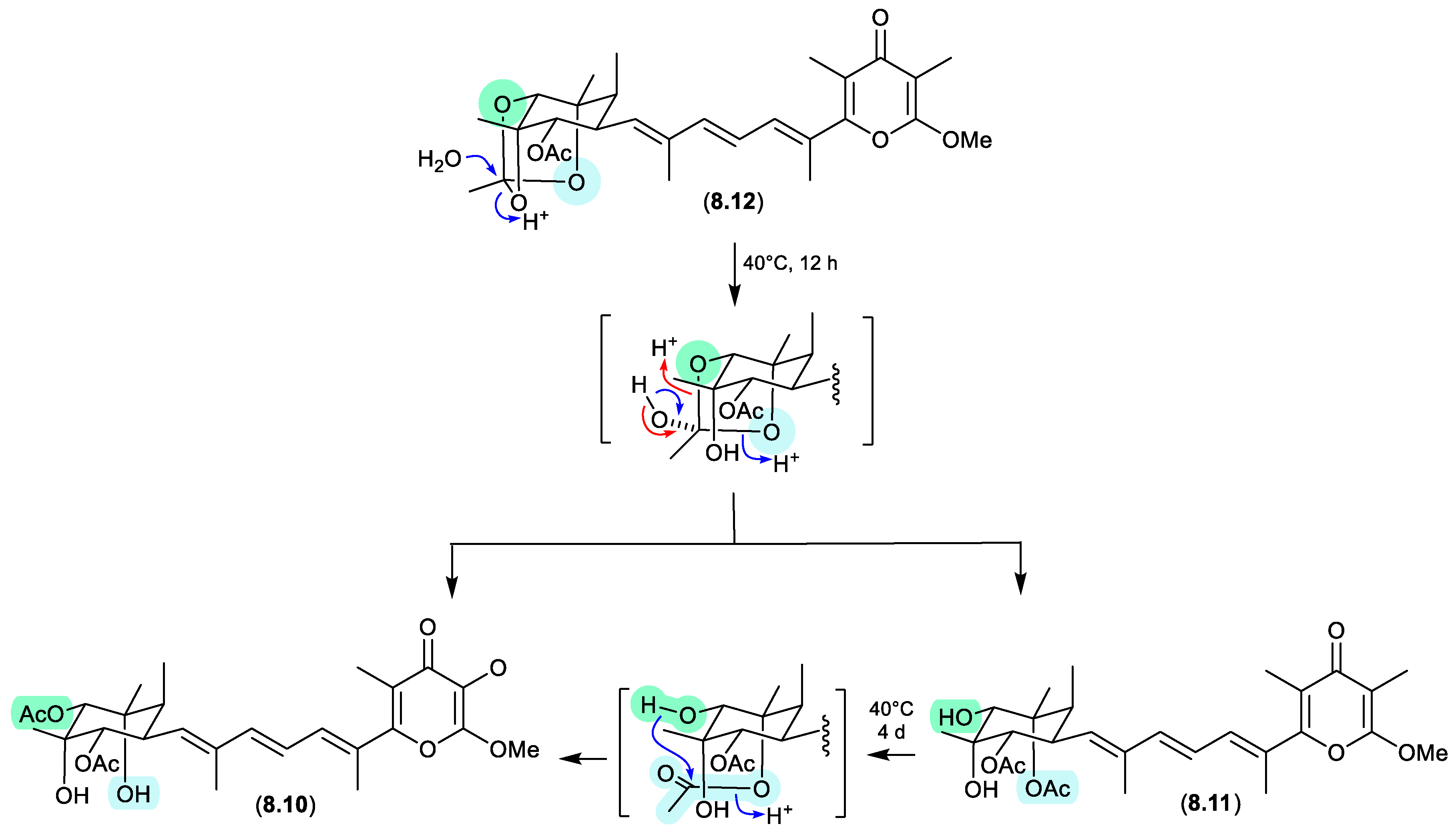

amaurones (Figures 8.3 and 8.4)

The Australian mullet fish gastrointestinal tract-derived fungus

Amauroascus sp. CMB-F713 yielded an array of polyketide pyrones with unprecedented carbon skeletons, including amaurones A–C (

8.9–

8.11), E (

8.12) and J (

8.13).[

121] Drying a solution of the orthoacetate

8.12 under nitrogen (at 40 °C overnight) resulted in hydrolysis to a 3:2:1 mixture with the monoacetates

8.10 and

8.11, which on further heating (4 d) returned a 1:1 mixture of

8.12 and

8.10, favouring the regioisomer with an equatorially (rather than axially) disposed acetate moiety. A comparable transformation was observed between

8.9 and

8.13, necessitating chair-chair ring inversion to bring the hydroxy and acetate moieties into a suitable 1,3-diaxial arrangement, where on this occasion both regio-isomers featured equatorially disposed acetate groups.

9. Epimerization

In selected natural products, non-acetal chiral centres can undergo epimerisation, providing insights into the chemical reactivity of unusual functionality and/or scaffolds.

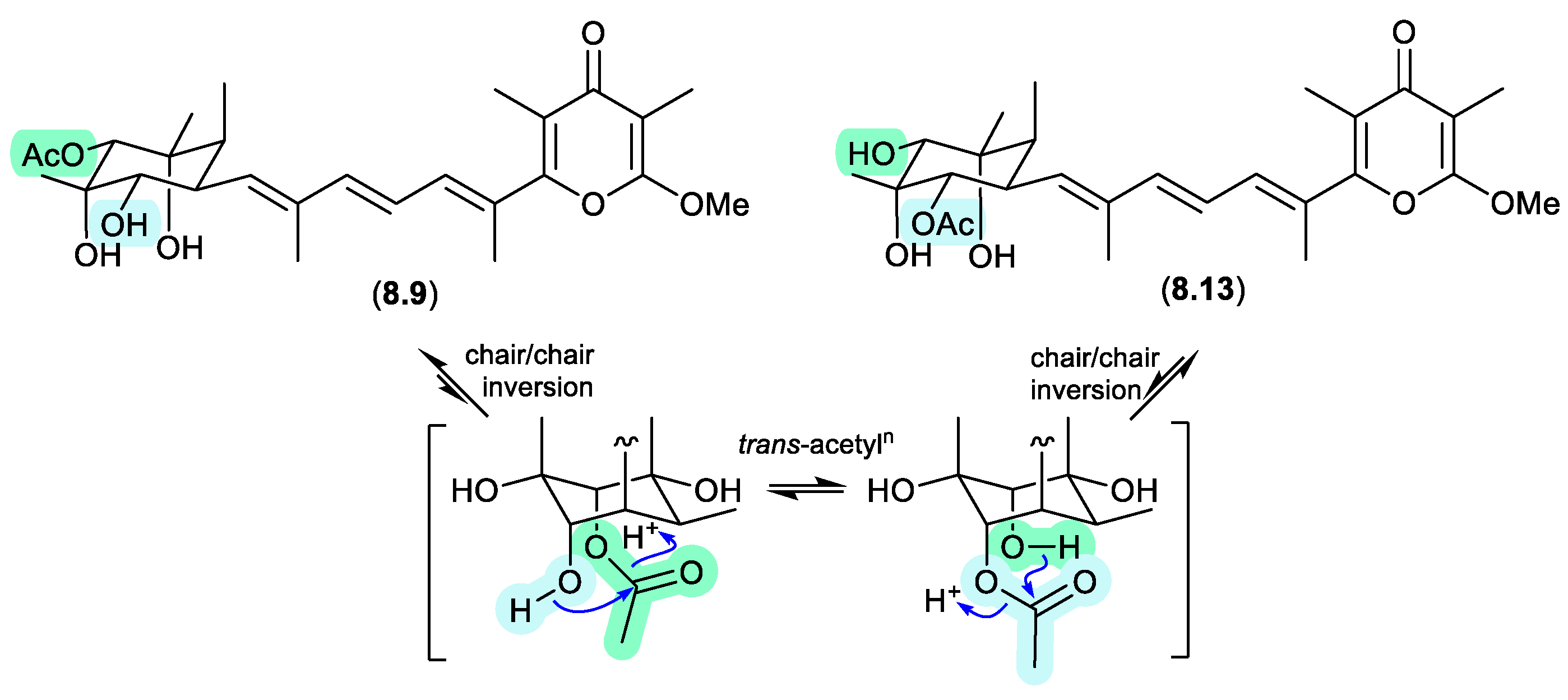

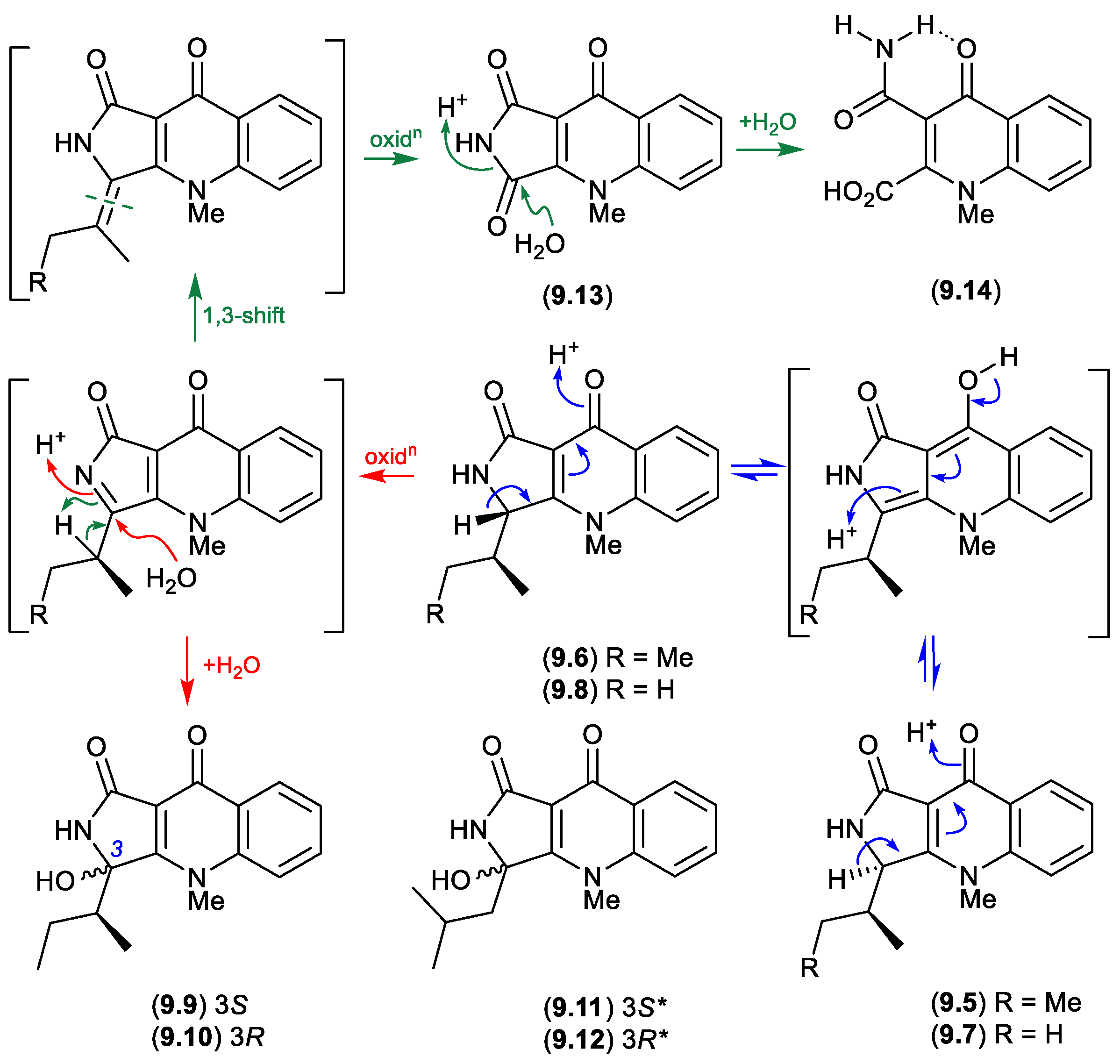

aspergillazines (Figure 9.1)

Indicative of how even slight changes in functionalisation can have a dramatic effect on chemical reactivity, the epimeric and highly modified

Aspergillus thiophane dipeptides, aspergillazines B (

9.1) and C (

9.2), did not undergo equilibration/epimerization on handling, whereas the corresponding tetrahydrofuran analogues, aspergillazines D (

9.3) and E (

9.4), underwent rapid equilibration/epimerization to a 1:0.85 mixture (most likely via a ring opened imine intermediate).[

122]

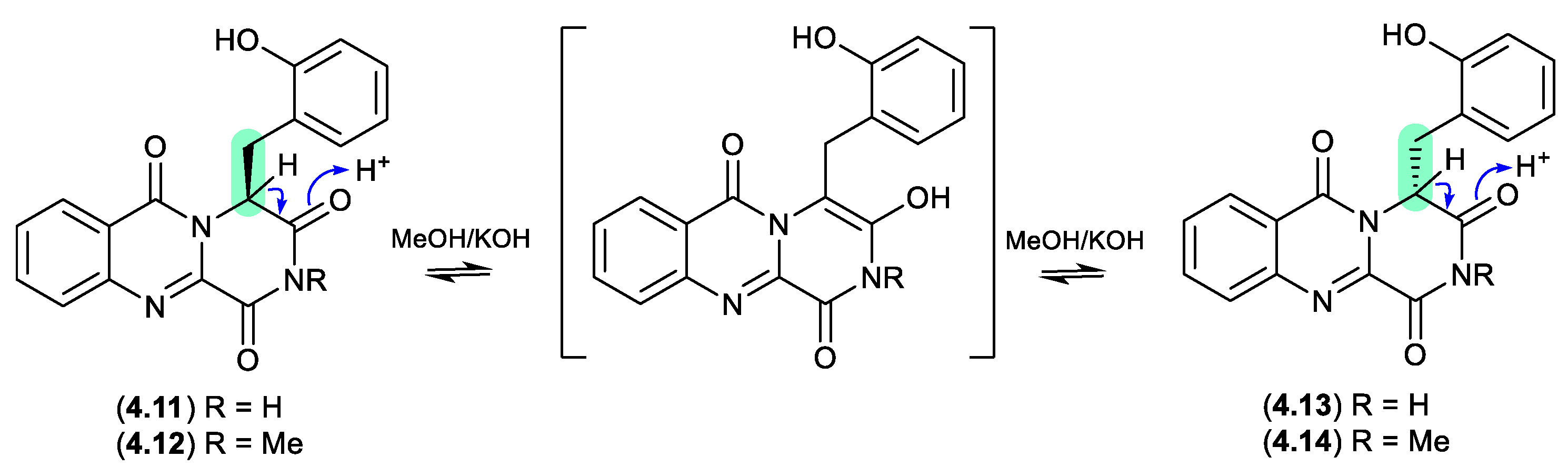

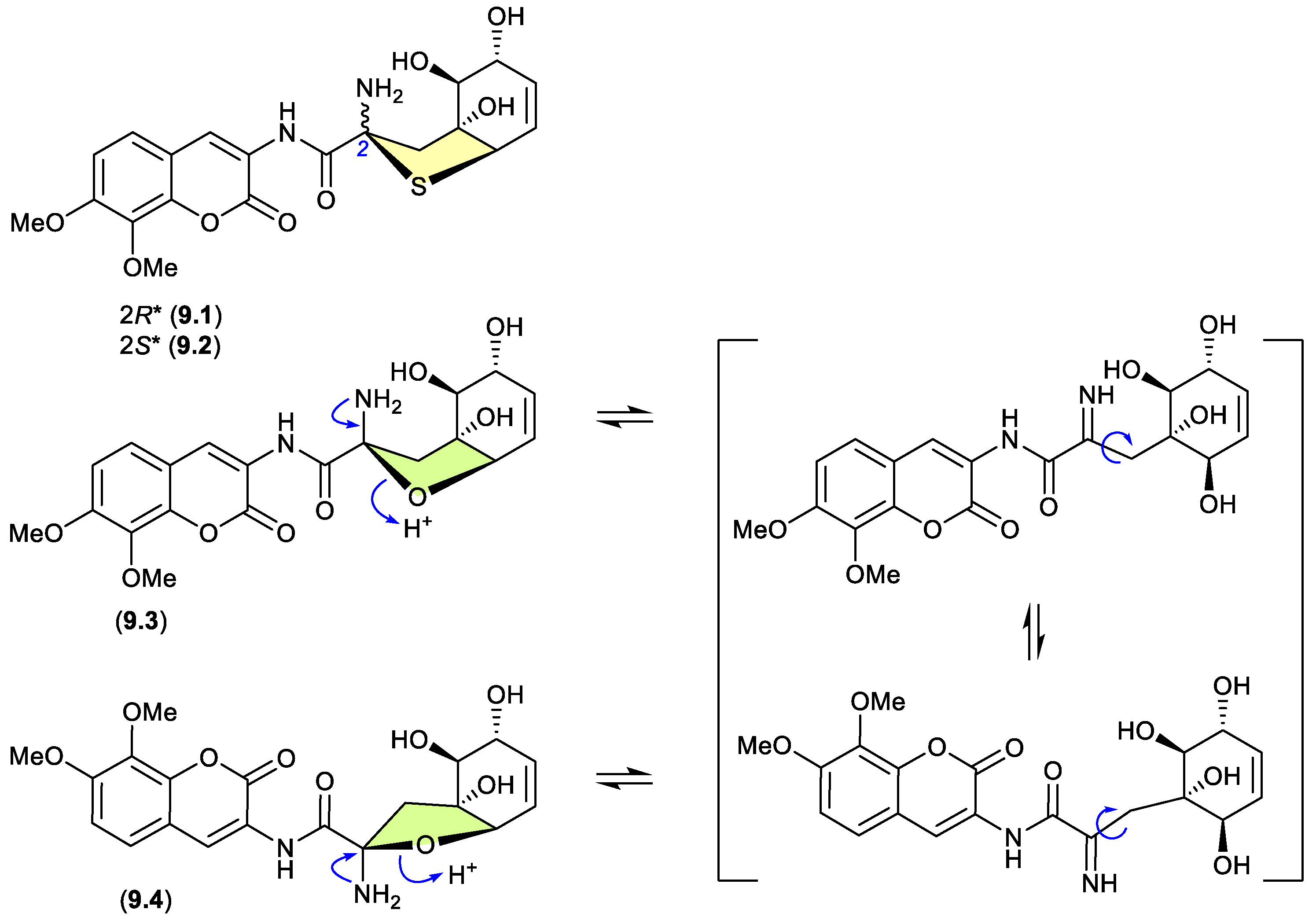

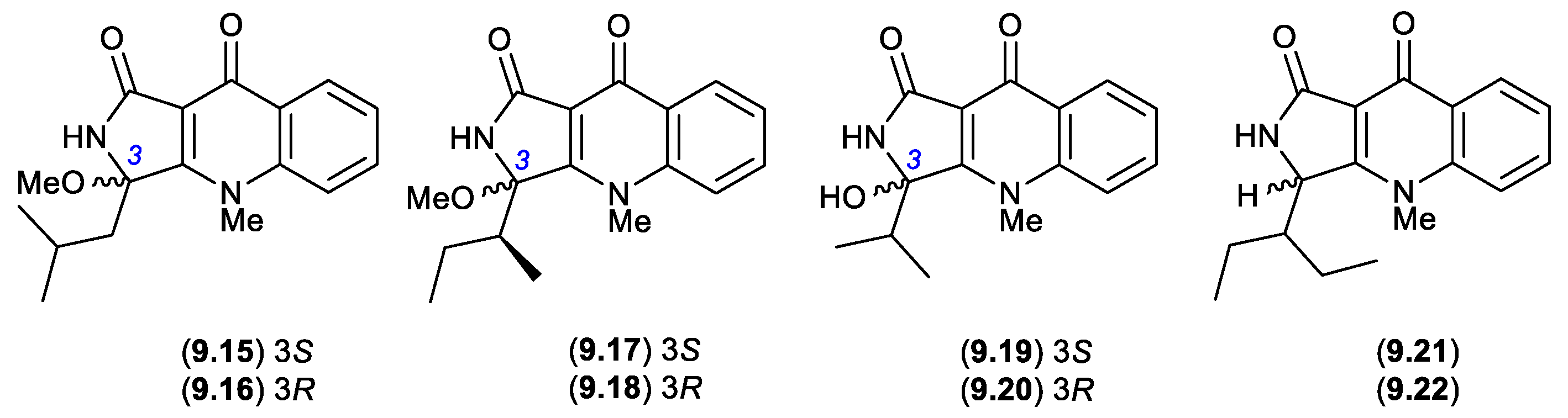

quinolactacins (Figures 9.2 and 9.3)

Planar structures for the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitory quinolactacins A–C were first reported in 2000, from an undescribed

Penicillium sp.[

123] A subsequent 2001 account revealed that quinolactacin A from

Penicillium citrinum 90684 was a mixture of the epimers A1 (

9.5) and A2 (

9.6), with the latter being 14-times more potent at inhibiting acetylcholinesterase. [

124] Significantly, the stereochemical difference between

9.5 and

9.6 was asserted at that time (incorrectly) to be about the sidechain 2°-methyl, suggestive of biosynthetic incorporation of Ile and

allo-Ile. A 2001 biomimetic synthesis of quinolactacin B failed to disclose that it too existed as a mixture of epimers B1 (

9.7) and B2 (

9.8),[

125] while a 2003 total synthesis confirmed the structure for quinolactacin B2 (

9.8) but incorrectly affirmed the earlier incorrect stereochemical assignment for A1 (

9.5) and A2 (

9.6).[

126]

A 2006 investigation into the Australian isolate

Penicillium citrinum MST-F10130 revealed the true complexity of quinolactacin chemistry and stereochemistry, reporting the known quinolactacins A2 (

9.6), B2 (

9.8), C2 (

9.9) and A1 (

9.5), as well as the new quinolactacins B1 (

9.7), C1 (

9.10), D2 (

9.11) and D1 (

9.12), along with the novel analogues, quinolonimide (

9.13) and quinolonic acid (

9.14).[

127] Significantly, this study revealed that under mild handling conditions; (i) A2 (

9.6) epimerises to a racemic mixture with A1 (

9.5), as does B2 (

9.8) with (

9.7); (ii) A2 (

9.6) undergoes a facile oxidation and non-stereospecific H

2O addition to yield C2 (

9.9) and C1 (

9.10), and (iii) undergoes oxidation to yield quinolonimide (

9.13); and (iv)

9.13 undergoes rapid and regiospecific hydrolysis to yield quinolonic acid (

9.14). These ease with which these epimerisations occurred suggests one of each epimer (i.e.

9.6/

9.8 or

9.5/

9.7) may be a natural product, and their respective epimer a handling artifact. It also seems likely that D1/D2 (

9.11/

9.12) are oxidative hydrolysis products of a hitherto undetected quinolactacin bearing a leucyl sidechain (cryptic — see Section 10).

In more recent studies, the known epimeric pairs of quinolactacins A2/A1 (

9.6/

9.5), B2/B1 (

9.8/

9.7) and C2/C1 (

9.9/

9.10), along with the purportedly new epimeric pairs quinolactacins E1/E2 (

9.15/

9.16), F1/F2 (

9.17/

9.18) and G1/G2 (

9.19/

9.20), were reported from a sponge-derived

Penicillium sp. SCSIO 41303.[

128] Based on the chemical reactivity/artifact studies outlined above, and given the use of silica gel chromatography with a MeOH/CH

2Cl

2 eluant, it seems highly probable that; (i) E1/E2 (

9.15/

9.16) are methanolysis artifacts of the hitherto undetected quinolactacin (cryptic — see Section 10) that is the speculated natural product source of D1/D2 (

9.11/

9.12); (ii) F1/F2 (

9.17/

9.18) are methanolysis artifacts of the co-metabolites A2/A1 (

9.6/

9.5); and (iii) G1/G2 (

9.19/

9.20) are hydrolysis artifacts of the co-metabolites B2/B1 (

9.8/

9.7). In other words, all the purported new natural products can be rationalised as artifacts.

Similarly, a recent account of an X-ray structure analysis and total synthesis of quinolactacin-H, from a marine-derived

Penicillium sp. ENP701, revealed it to be a 1:1 magnesium salt of the epimers (

R)-(+)-quinolactacin-H (

9.21) and (

S)-(–)-quinolactacin-H (

9.22).[

129] As

9.21 and

9.22 are capable of ready equilibration to a mixture of C-3 epimers, it is interesting to speculate whether one or other, or both are natural products. Most recently, in 2023 quinolactacins C1 (

9.10) and C2 (

9.9) were reported (incorrectly as new natural products) from the mangrove-derived

Penicillium citrinum YX-002.[

130]

10. Cryptic Natural Products

While modern natural products research benefits from highly sensitive and informative analytical technologies that make it possible to detect the complex array of chemistry found in natural extracts, thorough understanding still demands (for the most part) that natural products be extracted, purified, characterised, identified, and their properties evaluated experimentally. This can prove very challenging for that subset of highly chemically reactive natural products that do not survive extraction, and more often than not these unknowns remain unknown. This can be a lost opportunity, as knowledge of these compounds can be remarkably instructive. The following three case studies illustrate the value of pushing the limits to better understand and appreciate cryptic natural products.

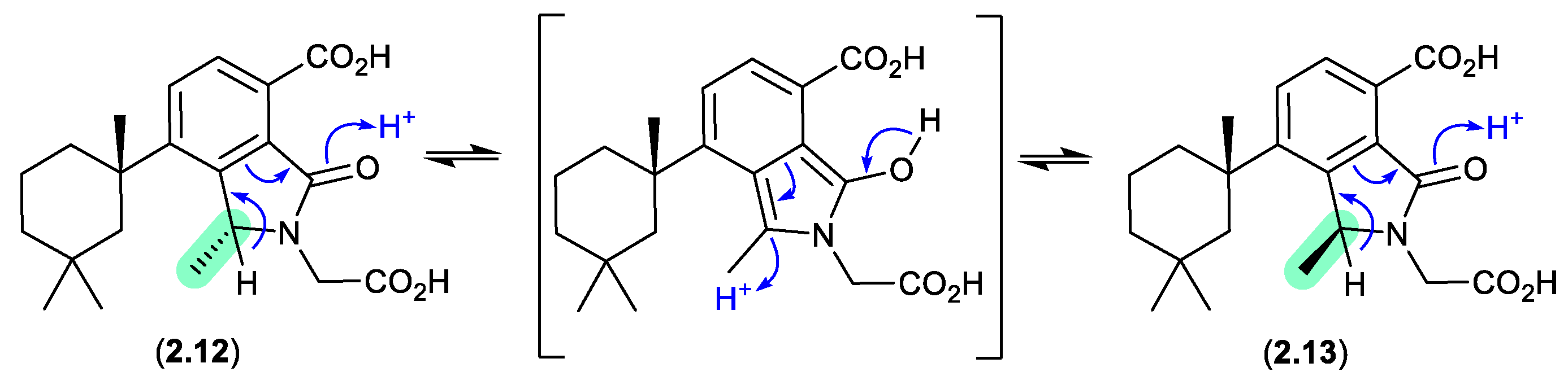

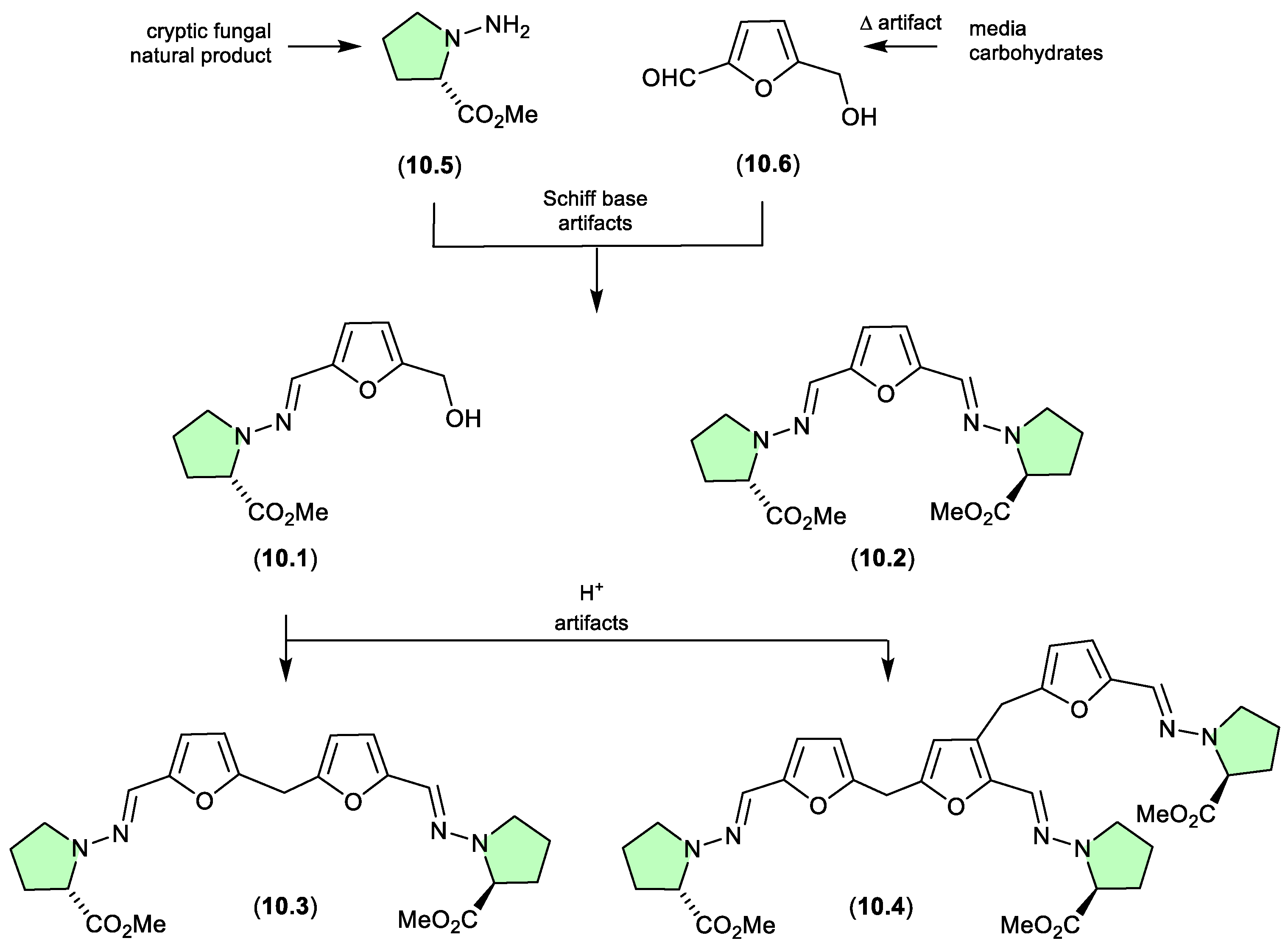

N-amino-l-proline methyl ester/prolinimines (Figure 10.1)

The Australian fish gastrointestinal tract-derived fungus,

Trichoderma sp. CMB-F563, yielded a series of unprecedented Schiff bases, prolinimines A–D (

10.1–

10.4).[

131] Of note, although

10.2–

10.4 were isolated, characterised and identified from a solvent extract of the fungal culture,

10.1 was not. Nevertheless, it was speculated that

10.1 should be present as a logical biosynthetic precursor of

10.2–

10.4 and following chemical analysis of fresh extracts it was detected. Moreover, it was demonstrated that during isolation and handling

10.1 underwent rapid and quantitative acid-mediated transformation to the

10.3 and

10.4. The structures for

10.1–

10.4 were confirmed by detailed spectroscopic analysis and a convergent biomimetic total synthesis starting with

N-amino-

l-proline methyl ester (

10.5) and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (

10.6). These observations revealed

10.1 as a cryptic natural product, with

10.3 and

10.4 designated as artifacts. However, in a surprising twist, a follow-up study aimed at better understanding the biosynthetic origins of the prolinimines, revealed that all the prolinimines A–D (

10.1–

10.4) were artifacts of the “real” cryptic fungal natural product

N-amino-

l-proline methyl ester (

10.5).[

132] On solvent extraction of the fungal culture, it was shown that

10.5 was released from the fungal mycelia at which time it came into contact with the media constituent

10.6 — a thermolysis artifact produced during autoclaving of carbohydrate rich media – and underwent rapid and quantitative transformation to the Schiff bases

10.1 and

10.2. As noted above, during isolation and handling

10.1 dimerised and trimerised to

10.3 and

10.4, respectively. The use of culture media depleted in carbohydrates (and hence

10.6) facilitated the detection and isolation of

10.5. It is interesting to speculate whether the cryptic small molecular weight, water soluble

10.5 would have been discovered without the fortuitous choice of a culture media rich in the thermolysis artifact

10.6.

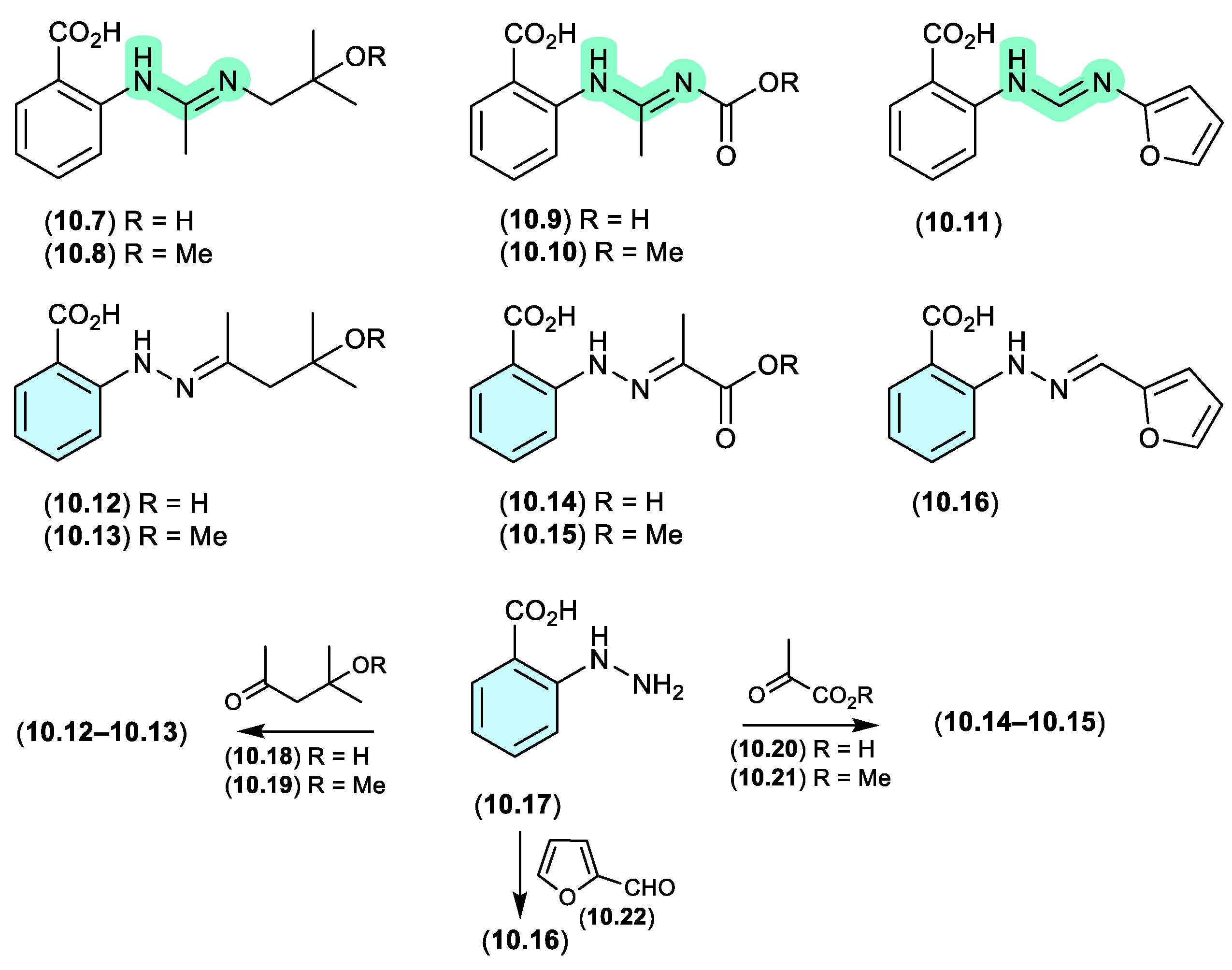

N-amino-anthranilic acid/penipacids (Figure 10.2–10.3)

Re-consideration of the penipacids A–E, first reported as the acyclic amidines

10.7–

10.11 from the South China deep sea sediment-derived fungus

Penicillium paneum SD-44,[

133] prompted a total synthesis structure revision as the hydrazones

10.12–

10.16.[

134] This revision proposed that penipacids A (

10.12) and B (

10.13) were Schiff base artifacts of the cryptic (undetected) natural product

N-amino-anthranilic acid (

10.17) with diacetone alcohol (

10.18) and its corresponding methyl ether

10.19, likely induced by excessive exposure to acetone and methanol under acidic handling conditions. Likewise, penipacids C (

10.14) and D (

10.15) were viewed Schiff base artifacts of

10.17 and the media constituent pyruvic acid (

10.20) and is methyl ester

10.21, while penipacid E (

10.16) was viewed as a Schiff base artifact of

10.17 and the media constituent furfural (

10.22).

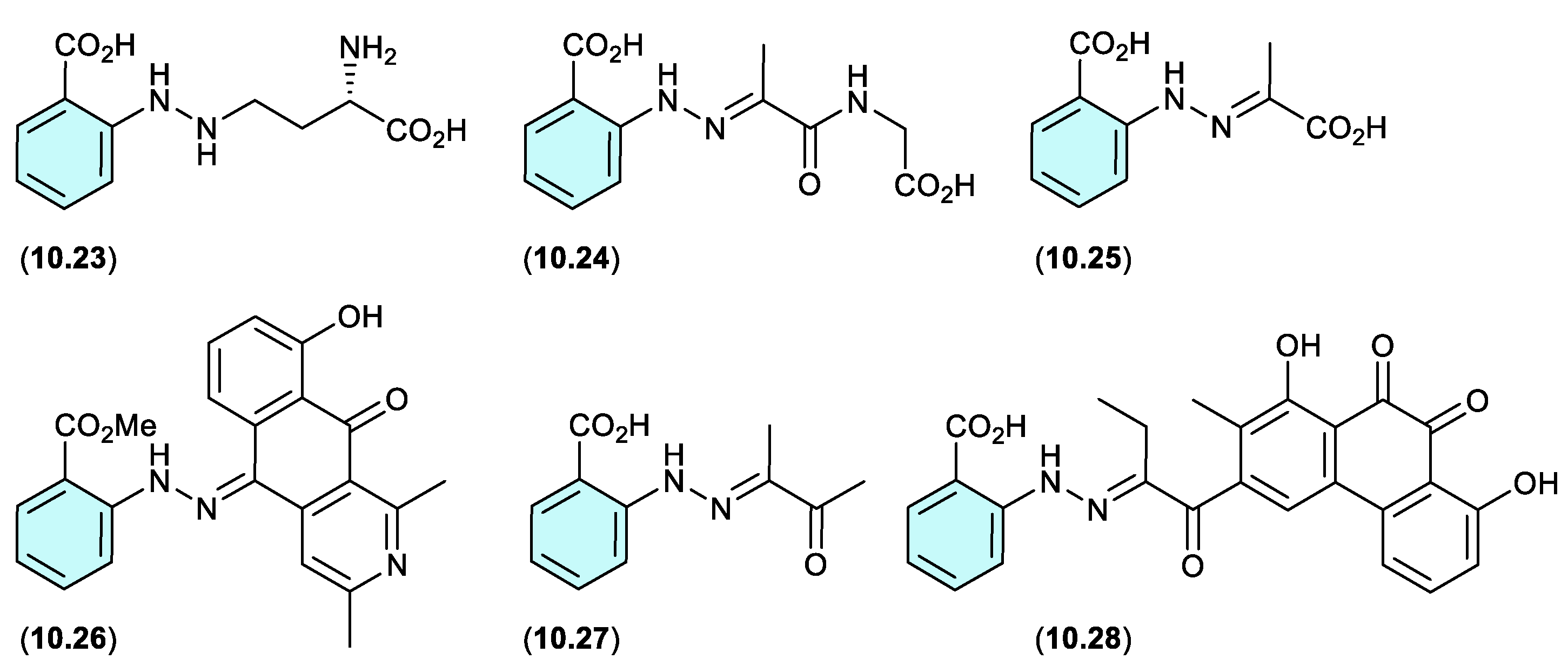

A review of the natural products literature revealed other instances of potential artifacts based on the purported cryptic natural product

10.17. These include; (i) the γ-glutamylphenylhydrazine anthglutin (

10.23) as a potential conjugate of

10.17 and L-homoserine, from a Japanese fungus

Penicillium oxalicum SANK 10477;[

135] (ii) the phenylhydrazone farylhydrazones A (

10.24) and B (

10.25) from a Tibetan Cordyceps-colonising fungus

Isaria farinosa – as potential Schiff base adducts of

10.17 and pyruvylglycine and pyruvic acid, respectively.[

136] Note that the revised structure for penipacid C (

10.14) is now identical to farylhydrazone B (

10.25); (iii) the 2-azoquinone-phenylhydrazine katorazone (

10.26) from a Japanese soil-derived

Streptomyces sp. IFM 11299 — a potential Schiff base adduct of

10.17 and the known fungal anthraquinone utahmycin A, which was coincidentally reported to be a co-metabolite with

10.26.[

137] (iv) farylhydrazone C (

10.27), along with farylhydrazone B (

10.25), from an Antarctic soil-derived

Penicillium sp. HDN14-431 — as potential Schiff base adduct of

10.17 with pyruvic acid and dimethylglyoxal, respectively, where the latter is known to be produced during thermal processing of carbohydrate rich foods, and as such could be a media constituent induced during autoclaving;[

138] and (v) the aromatic polyketide murayaquinone C (

10.28) from the ant gut-derived

Streptomyces sp. NA4286 — a potential Schiff base adduct of

10.17 with a suitably substituted anthraquinone co-metabolite.[

139]

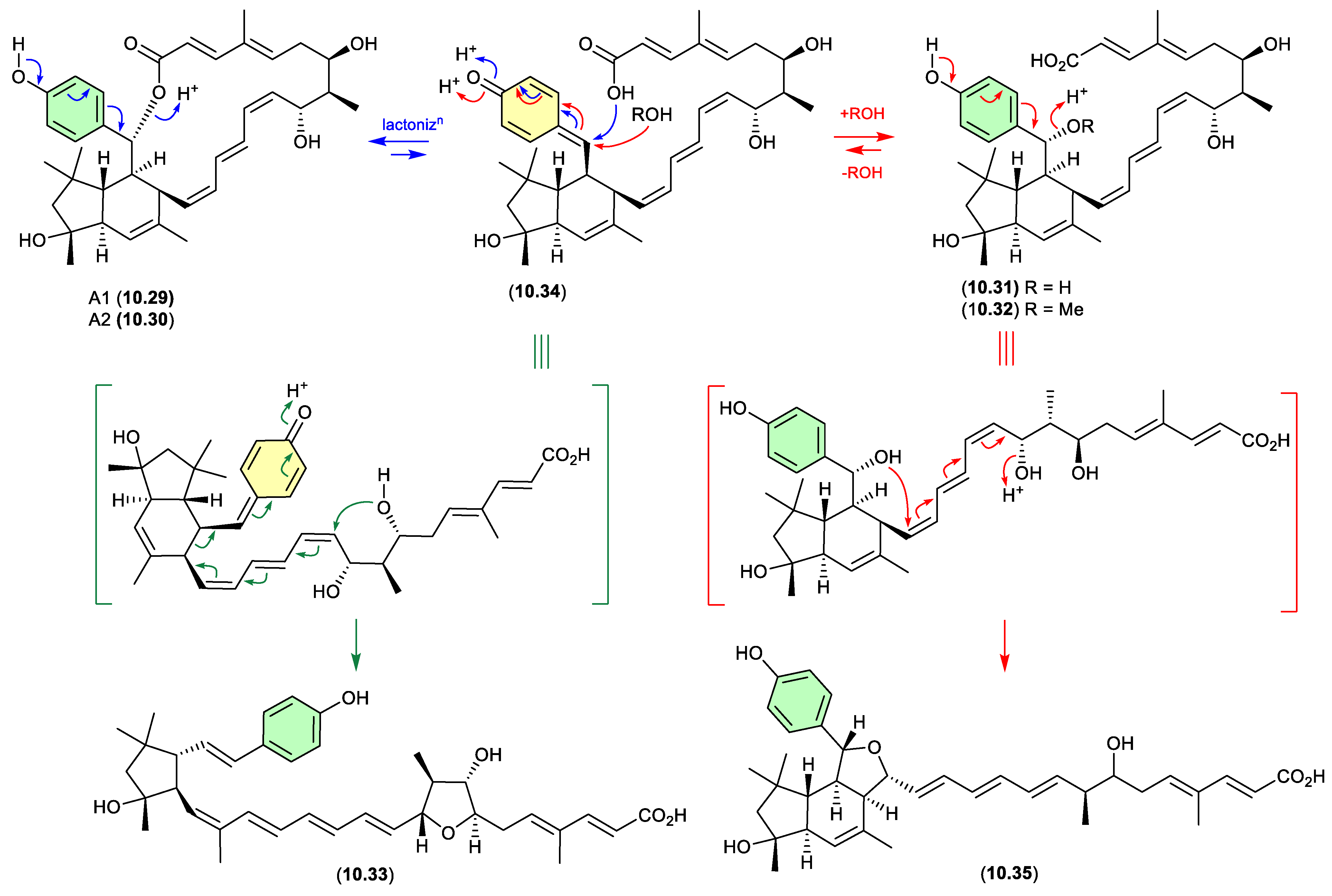

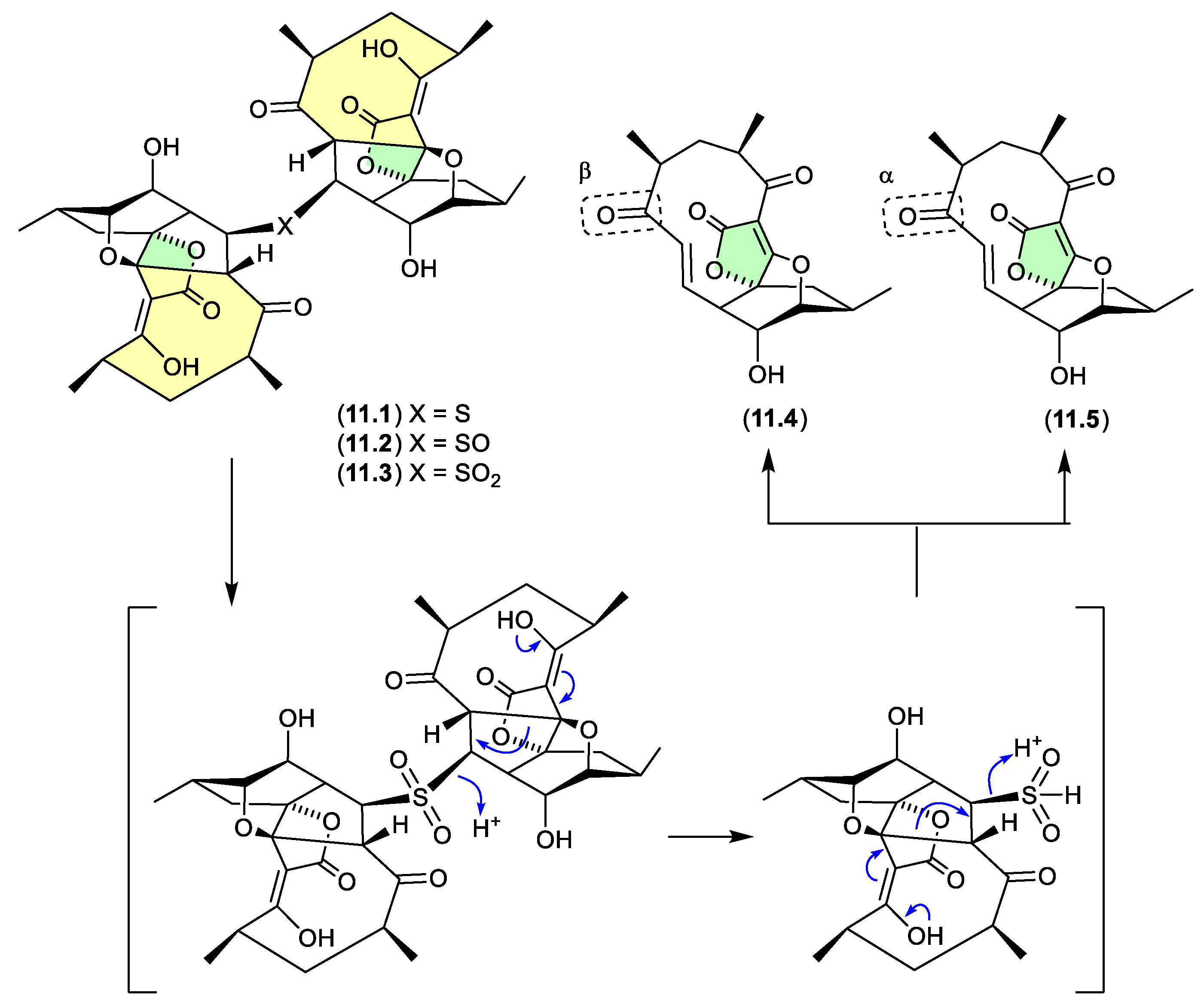

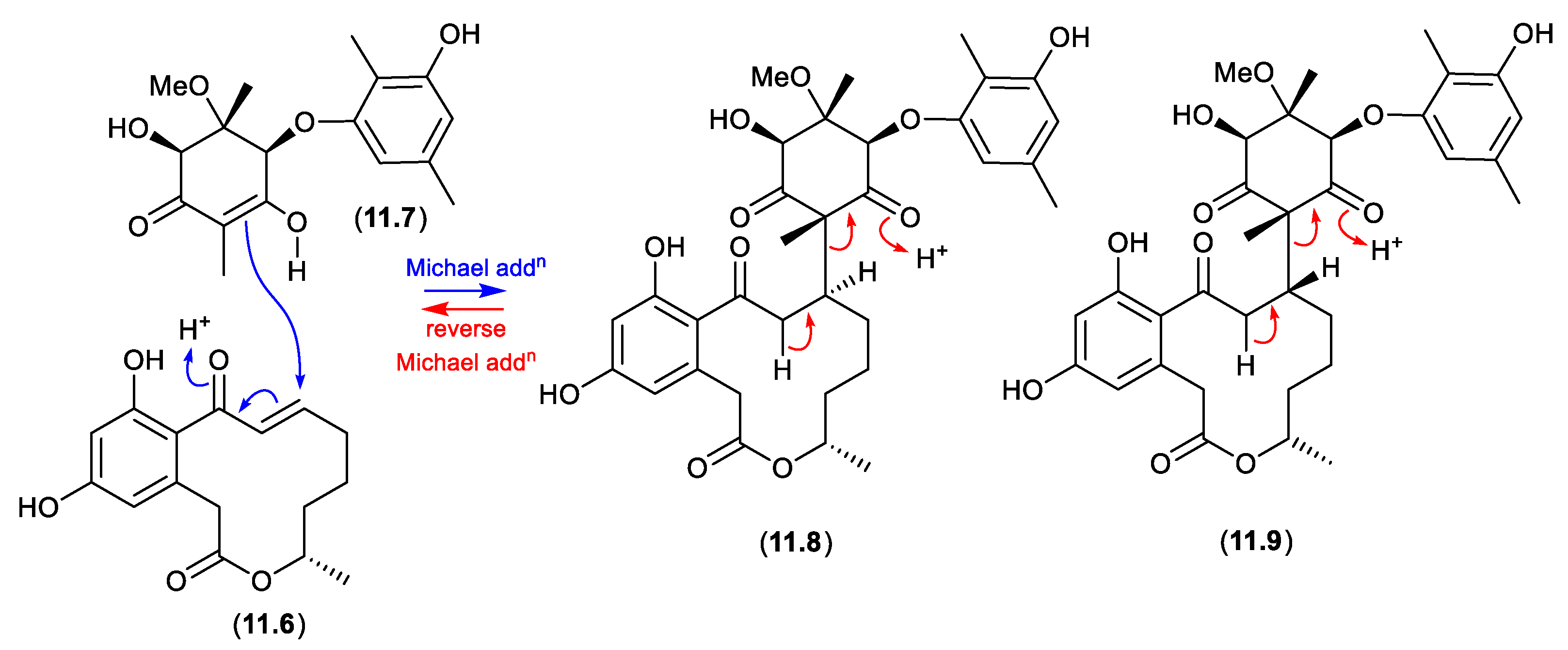

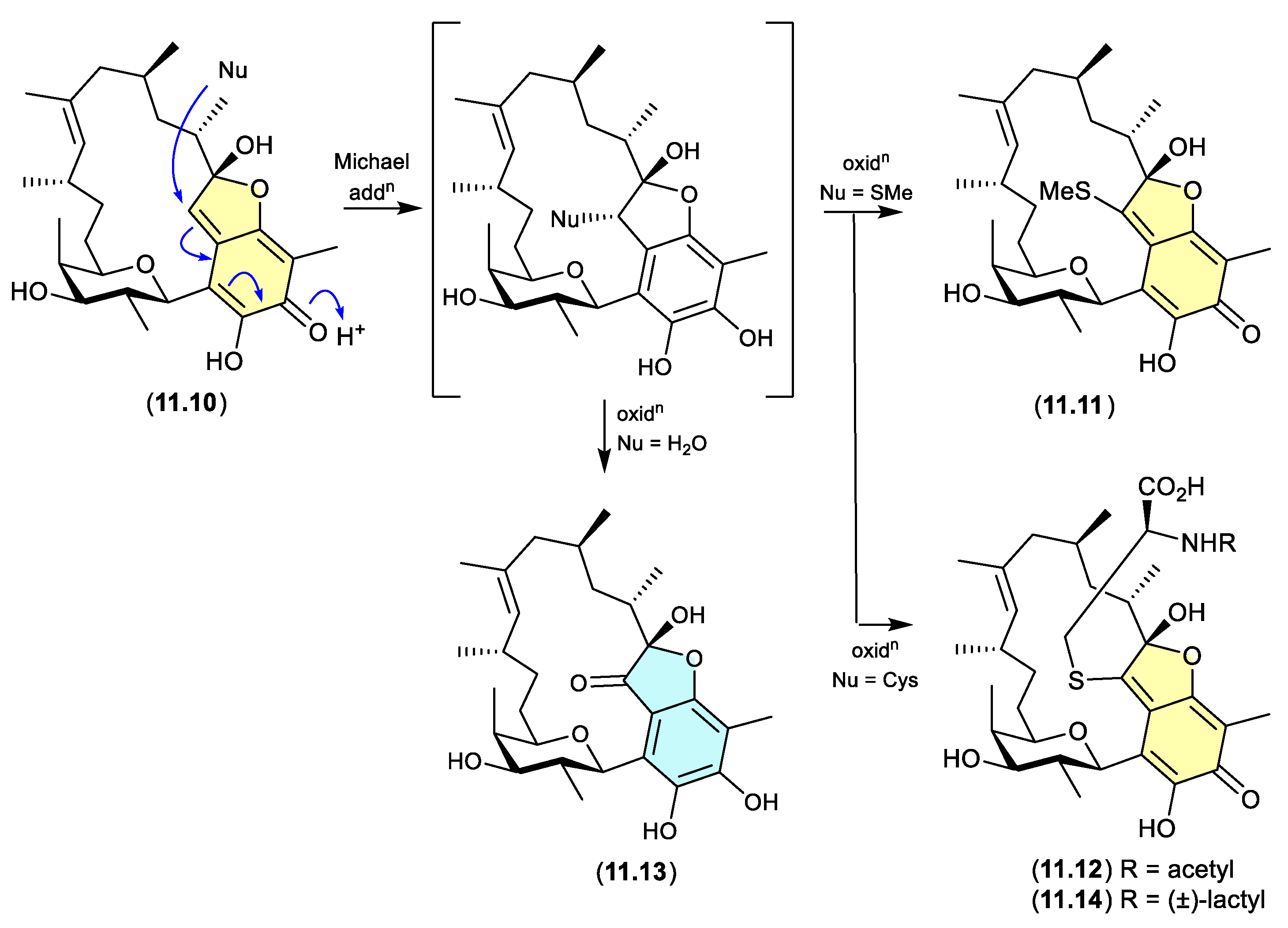

elansolids (Figure 10.4)

In 2011 Müller et al reported on the atropisomeric elansolids A1 (

10.29) and A2 (

10.30), and the

seco analogues, elansolids B1 (

10.31) and B2 (

10.32), as the first polyketide natural products from the non-myxobacterial gliding bacteria

Chitinophaga sancti.[

140] Interestingly, where A2 (

10.30) exhibited promising antibacterial activity, its atropisomer A1 (

10.29) was less active. Supportive of structure assignments, on storage in DMSO-

d6 at r.t. A2 (

10.30) transformed to A1 (

10.29), while on exposure to a 0.1 M NaOH in MeOH/H

2O both A2 (

10.30) and A1 (

10.29) underwent ring opening to B2 (

10.32). This latter observation prompted speculation that B2 (

10.32) was an artifact of A1 (

10.29) and A2 (

10.30) brought about by solvolysis during isolation and handling. In a follow-up study, these authors observed that elansolid production was cultivation condition dependent, isolated and identified the new seco analogue elansolid D1 (

10.33) and revealed that B1 (

10.31) and B2 (

10.32) were artifacts induced by the addition of H

2O and MeOH, respectively, to a common chemically reactive cryptic metabolite. [