Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

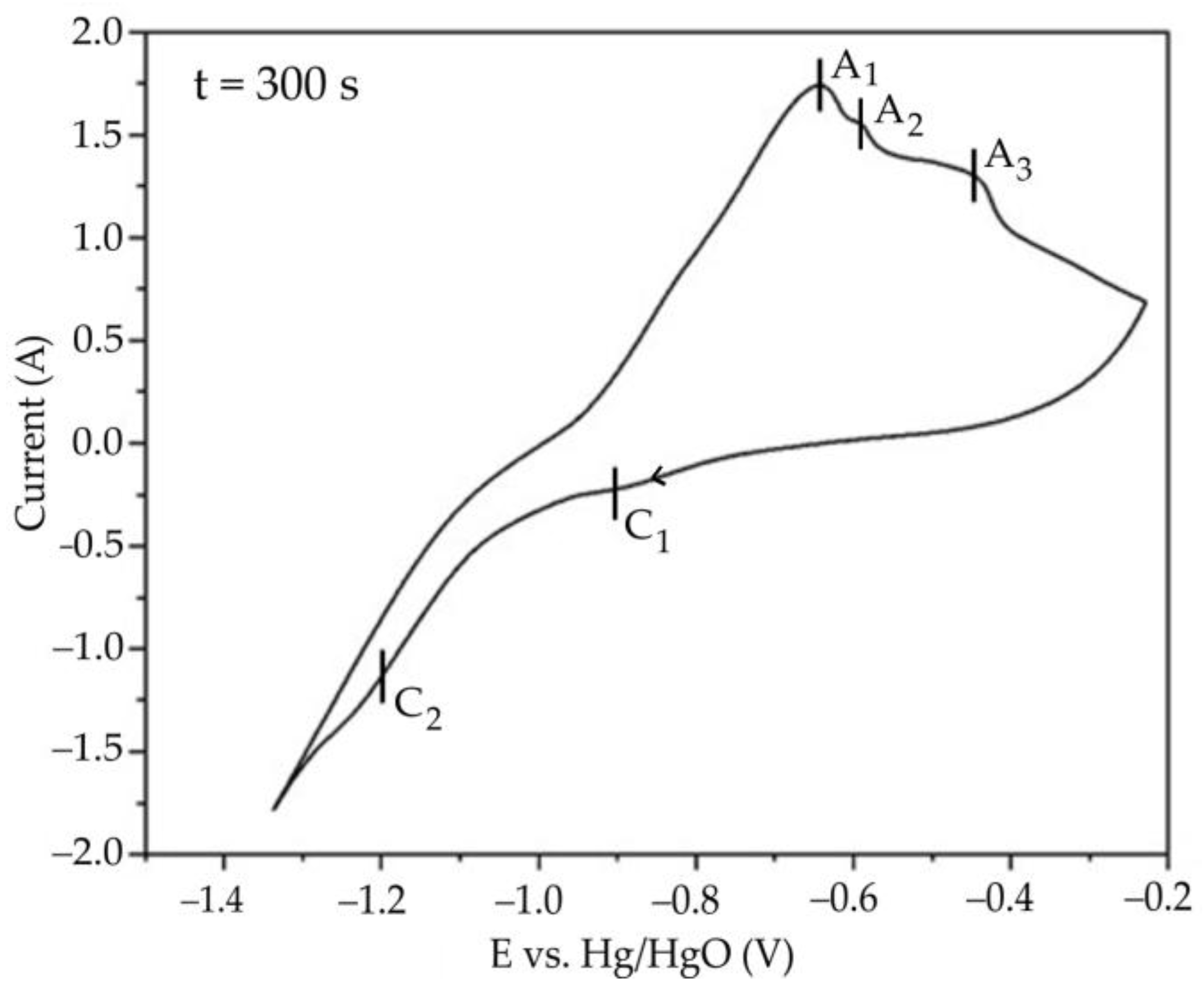

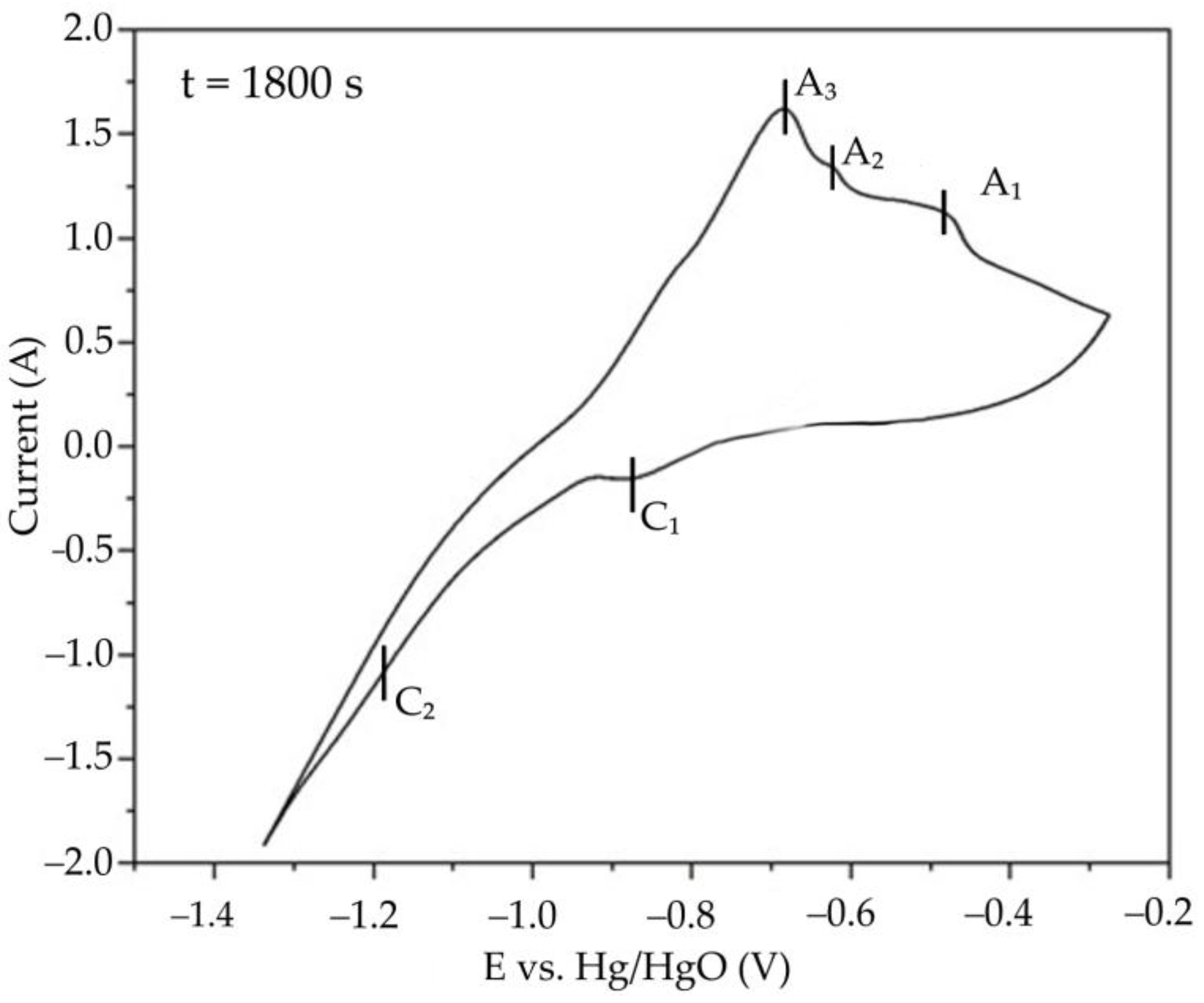

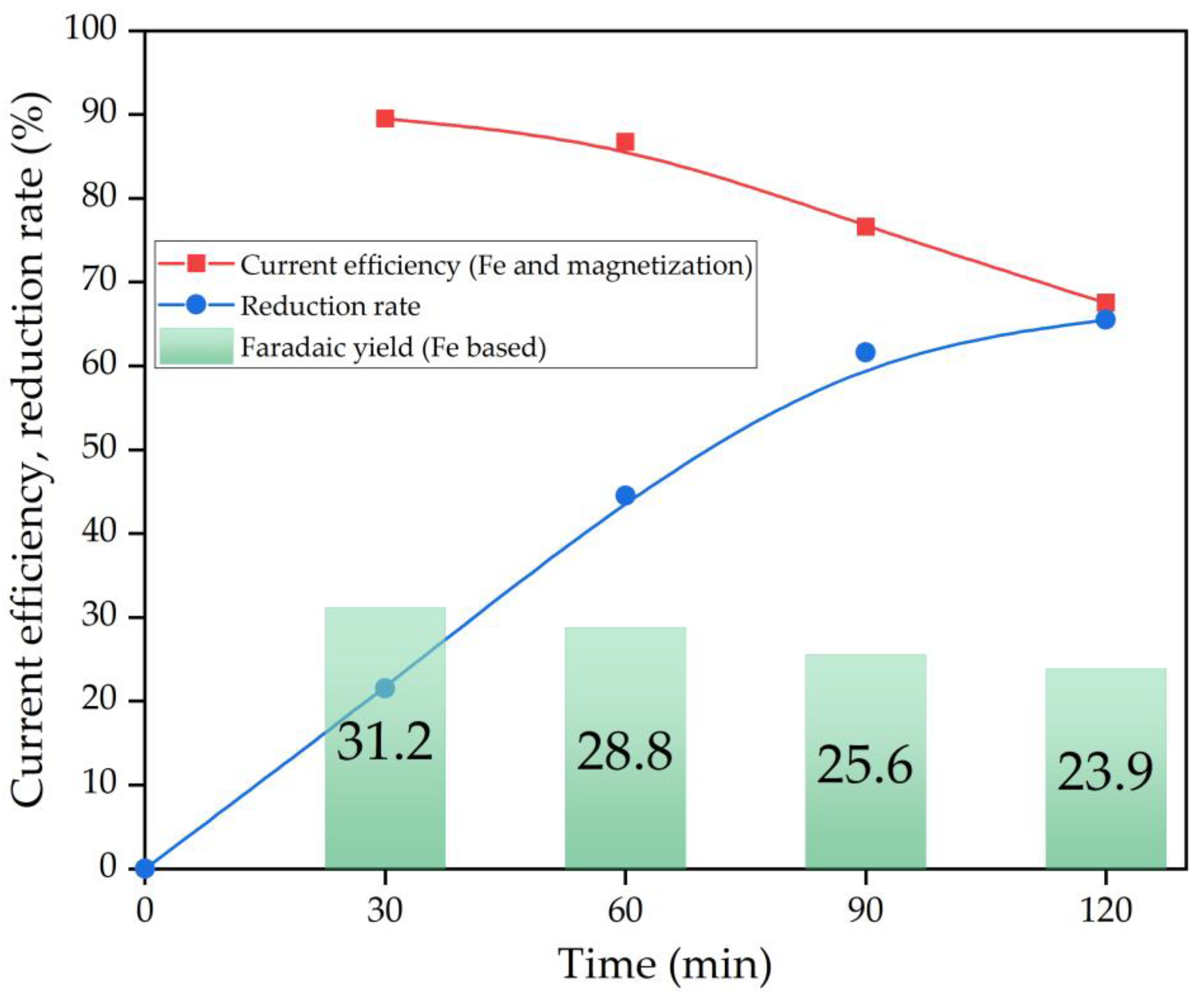

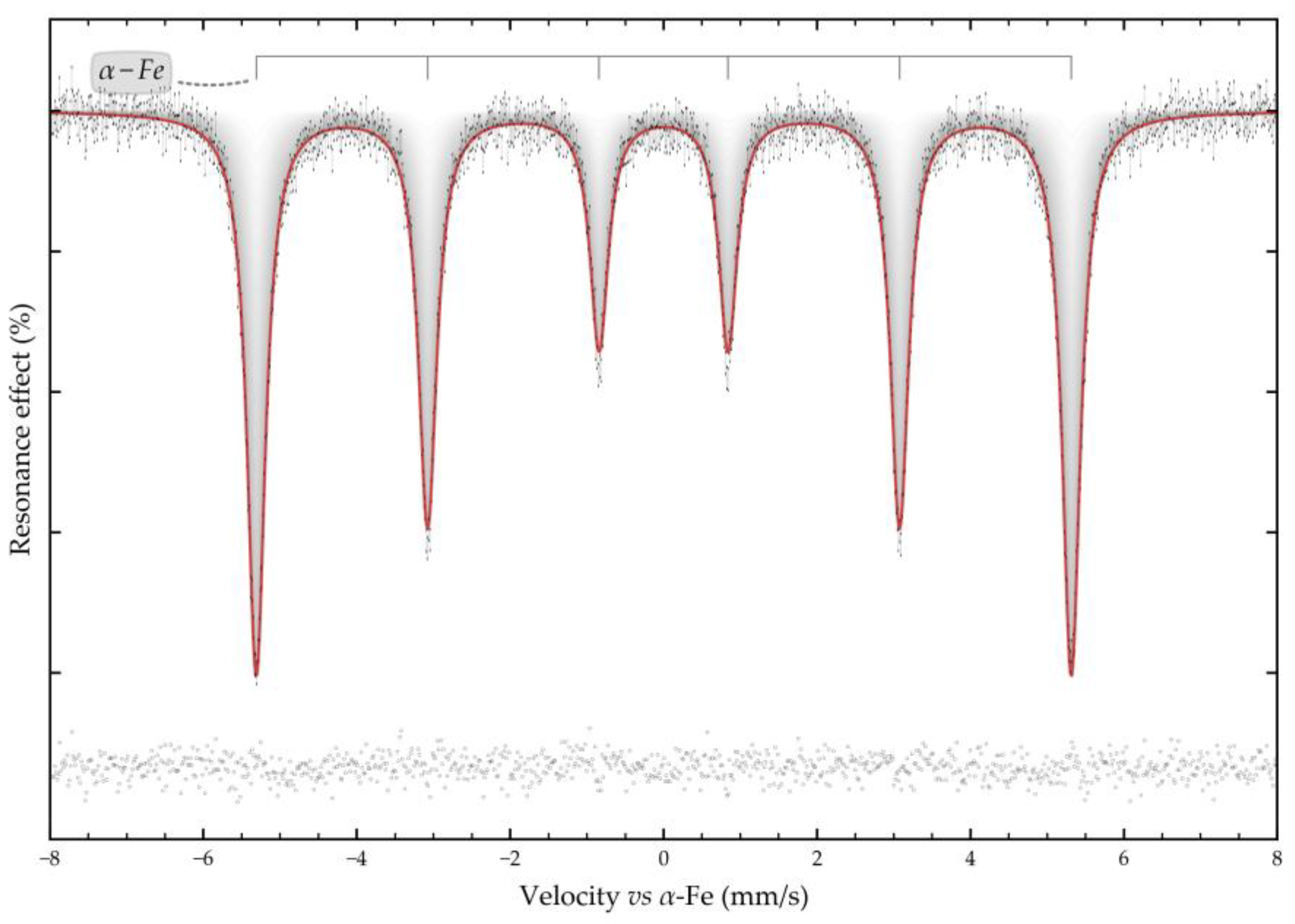

The Bayer process, the dominant method of alumina production for over a century, faces several challenges, including low iron content in bauxite residue, increased caustic alkali consumption and low alumina recovery rates. This article focuses on studying electrolytic reduction processes of bauxite iron minerals in alkaline solutions as a potential improvement to the traditional Bayer process for producing alumina. The research employs a metal mesh cathode at the bottom of an electrochemical cell to simultaneously reduce iron minerals and leach aluminium and silica from coarse boehmite bauxite before milling and high-pressure leaching. Preliminary thermodynamic research indicates that the presence of both hematite (α-Fe2O3) and chamosite ((Fe2+,Mg,Al,Fe3+)6(Si,Al)4O10(OH,O)8) in this type of bauxite helps to achieve a higher iron concentration in the solution. Cyclic voltammetry revealed that, in the initial stage of electrolysis, overvoltage at the cathode decreases as metallic iron deposited and conductive magnetite form on the surface of the particles. After 60 min, the reduction efficiency begins to decrease. The proportion of the current used for magnetization and iron deposition on the cathode decreased from 89.5% after 30 min to 67.5% after 120 min. Studying the electrolysis product using SEM-EDS revealed the formation of a dense, iron-containing reaction product on the particles' surface, preventing diffusion of the reaction products. Mössbauer spectroscopy of the high-pressure leaching product revealed that the primary iron-containing phases of bauxite residue are maghemite (Fe3O4), formed during the hydrolysis of sodium ferrite (Na2FeO4).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- reduced iron (Fe) content in BR (down to 35%);

- increased consumption of caustic alkali (up to 100 kg/t of Al2O3);

- low Al recovery (no more than 85–90%);

- consequently, higher Al2O3 content in BR (up to 10–15%).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Analytical Methods

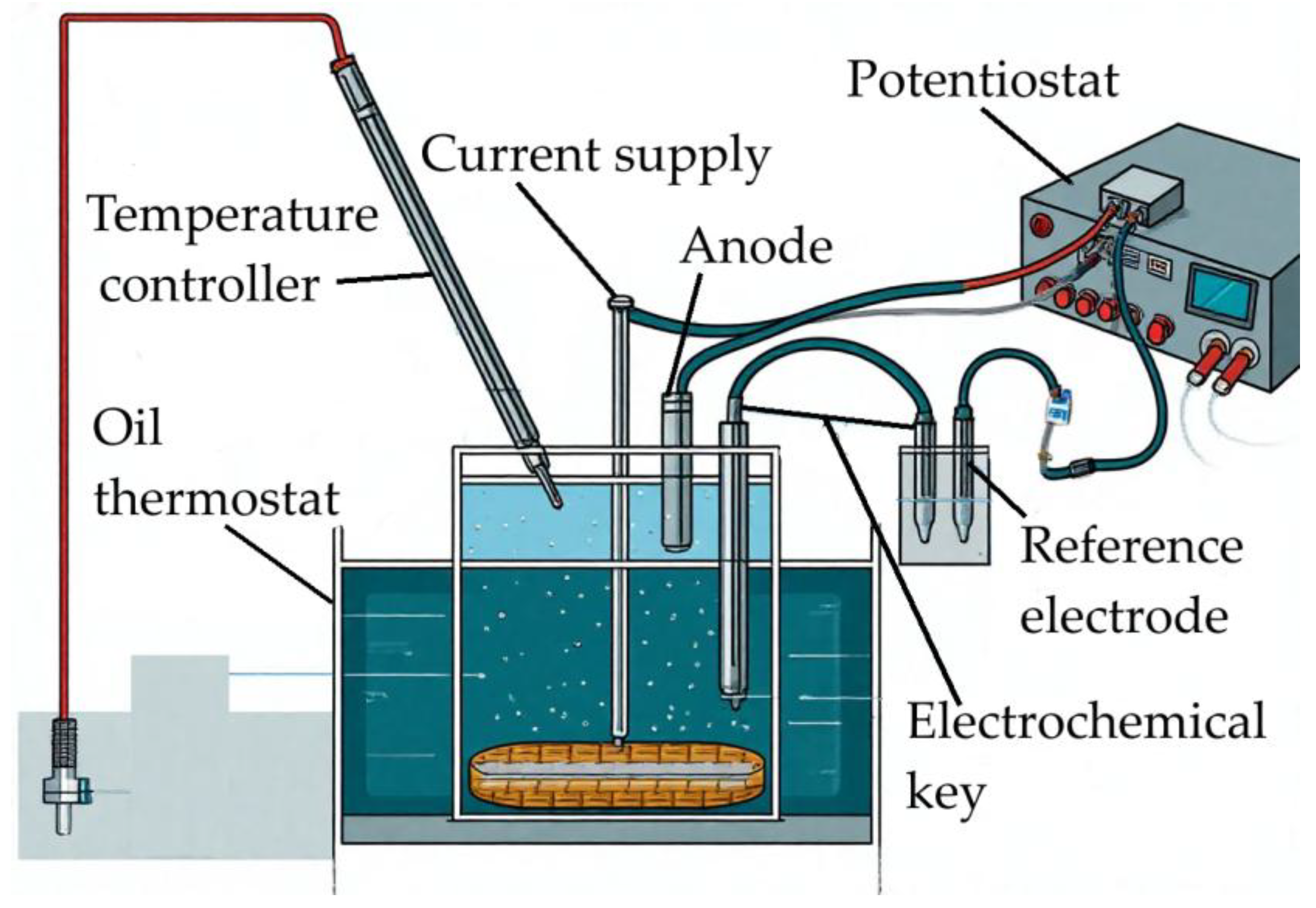

2.3. Experimental

3. Results and Discussion

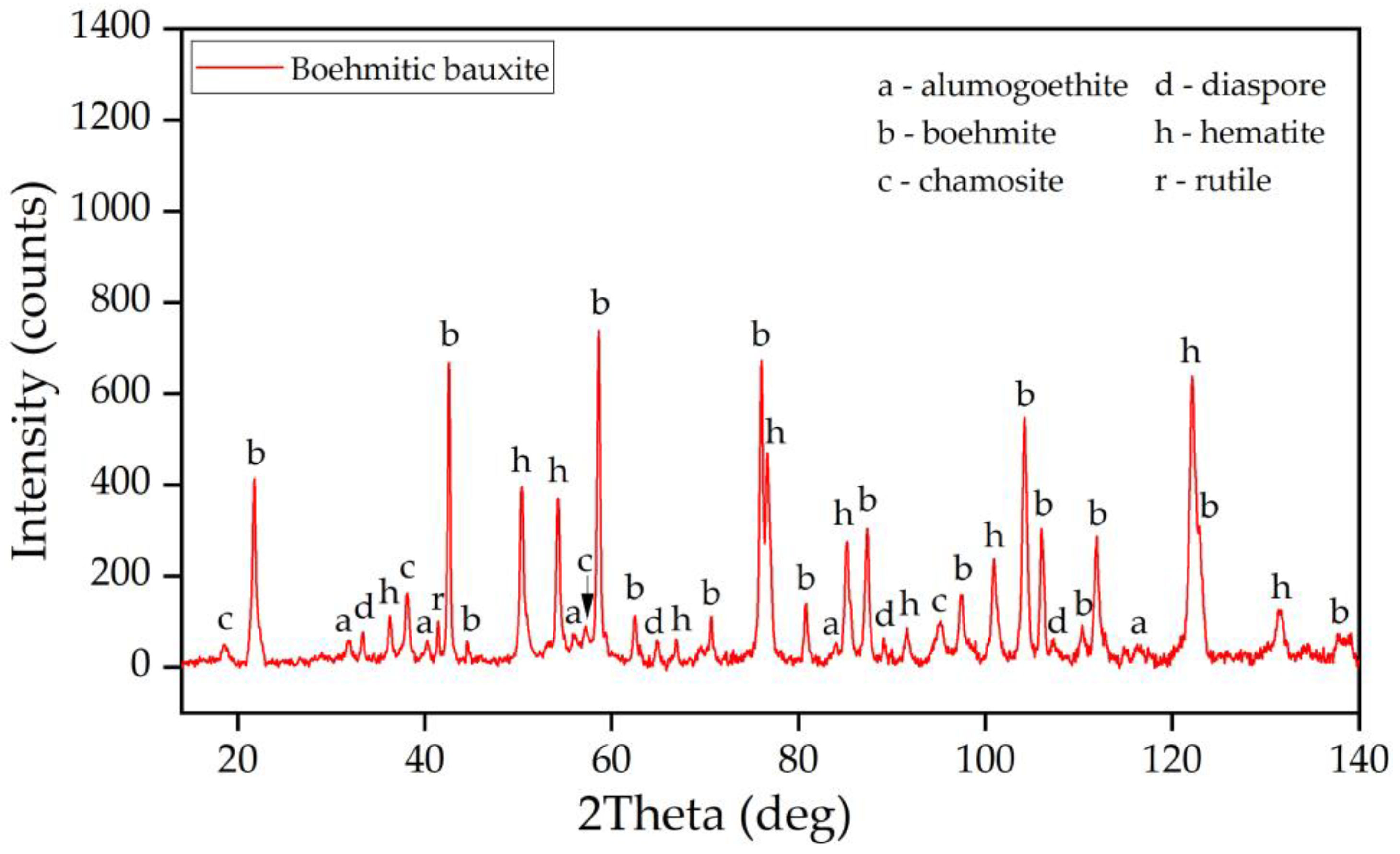

3.1. Characterization of the Raw Bauxite

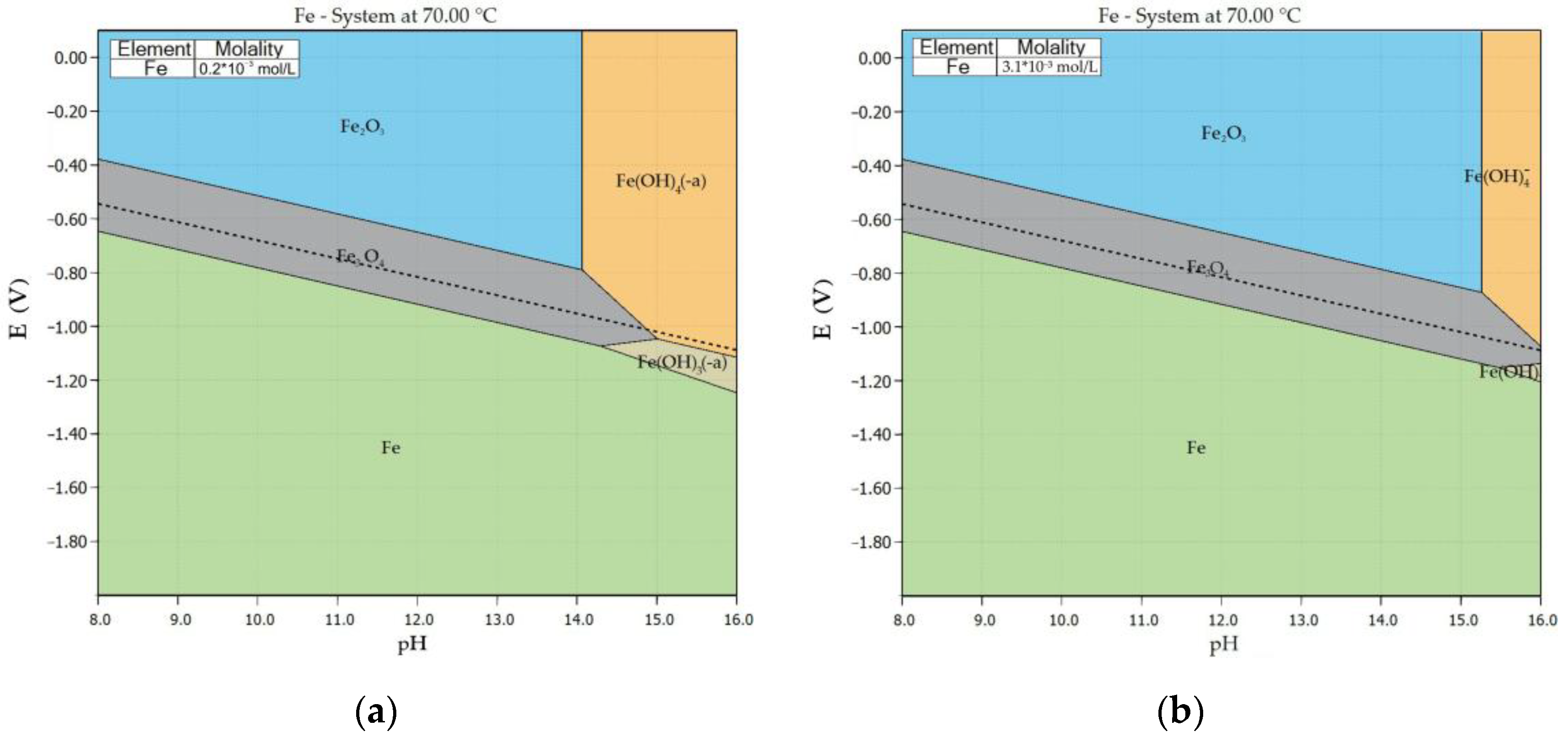

3.2. Thermodynamic Study of Iron Minerals Dissolution in Alkali Solution

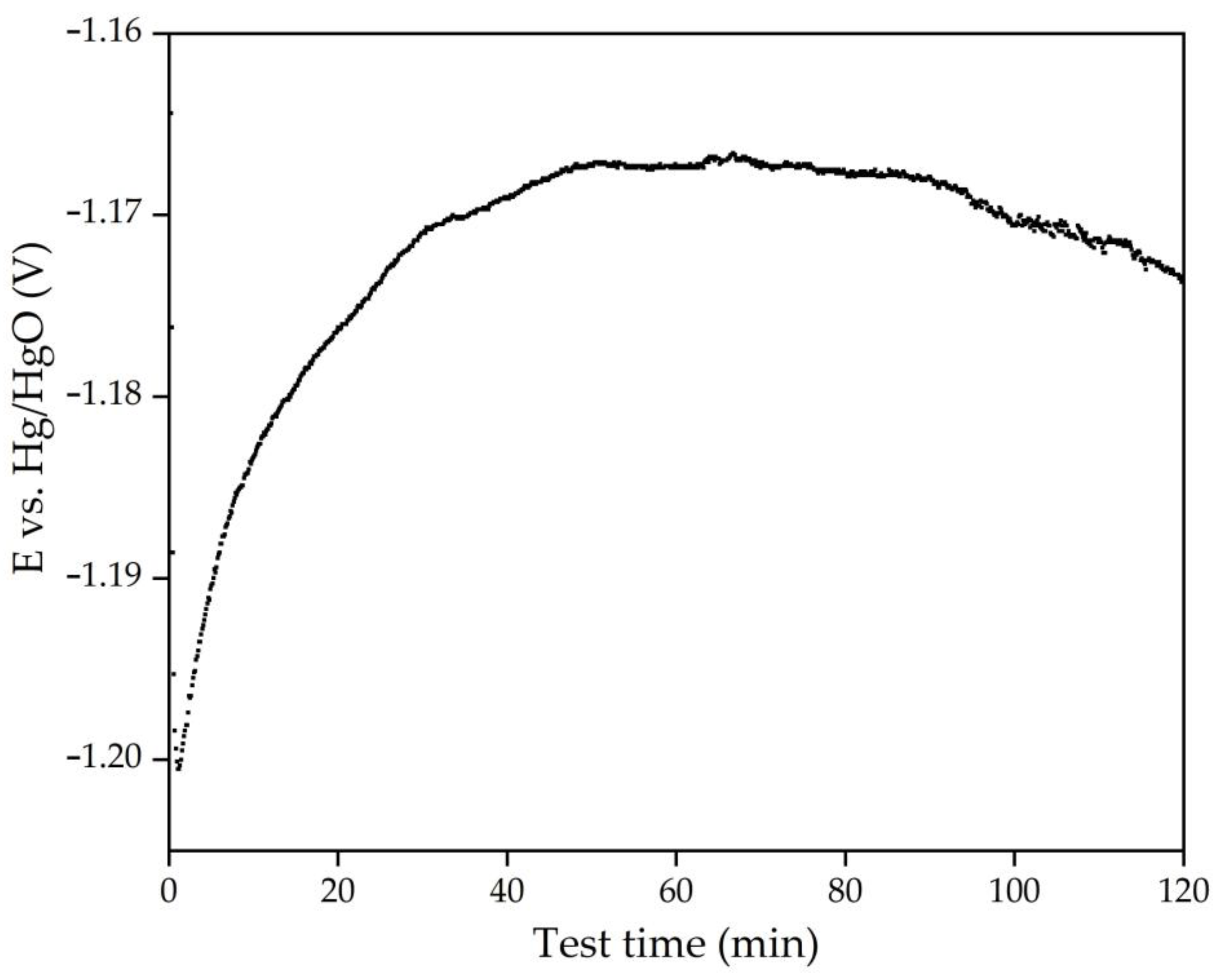

3.3. Electrochemical Studies of Iron Minerals Reduction in Suspension of Coarse Bauxite Particles in Alkali Solution

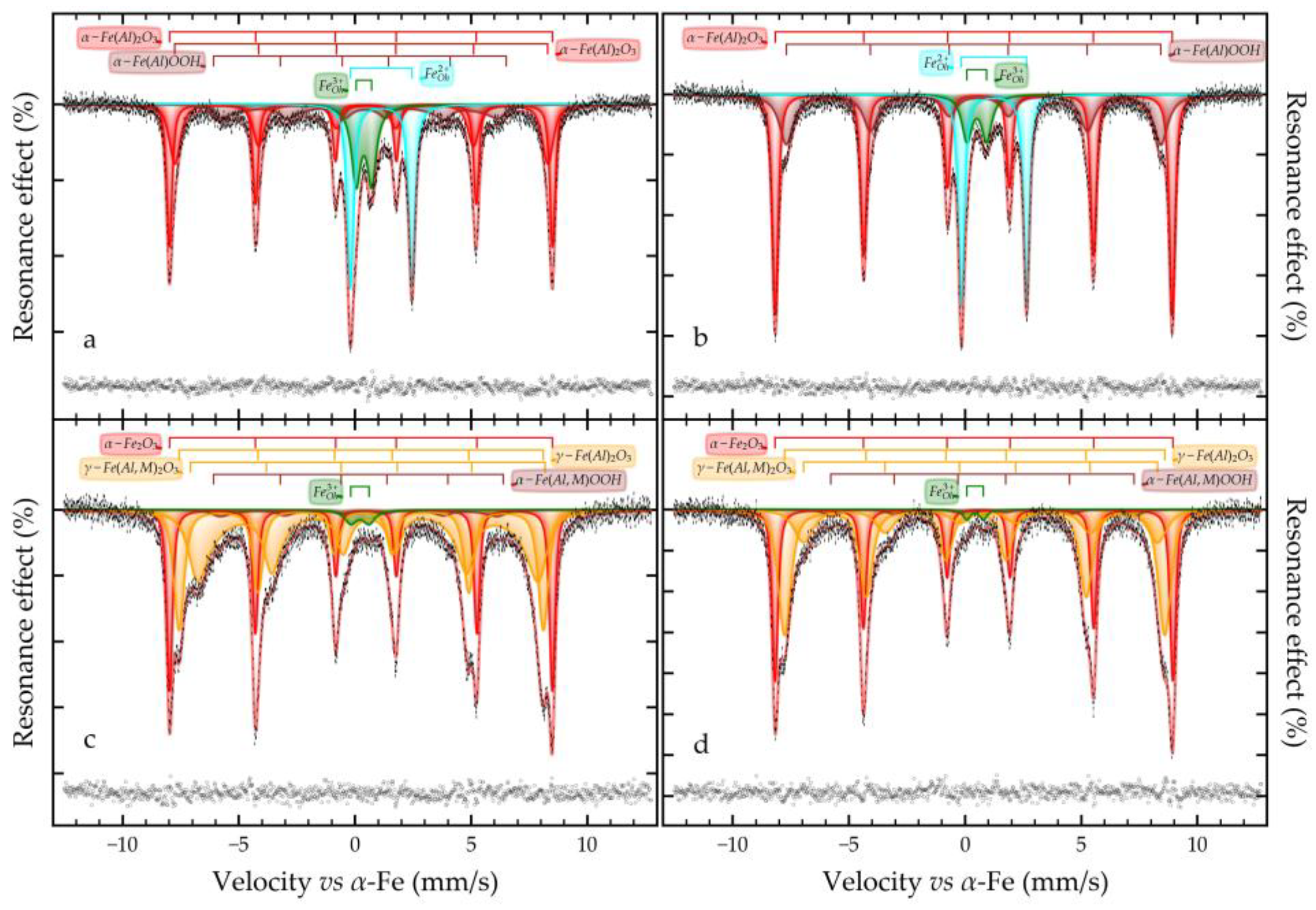

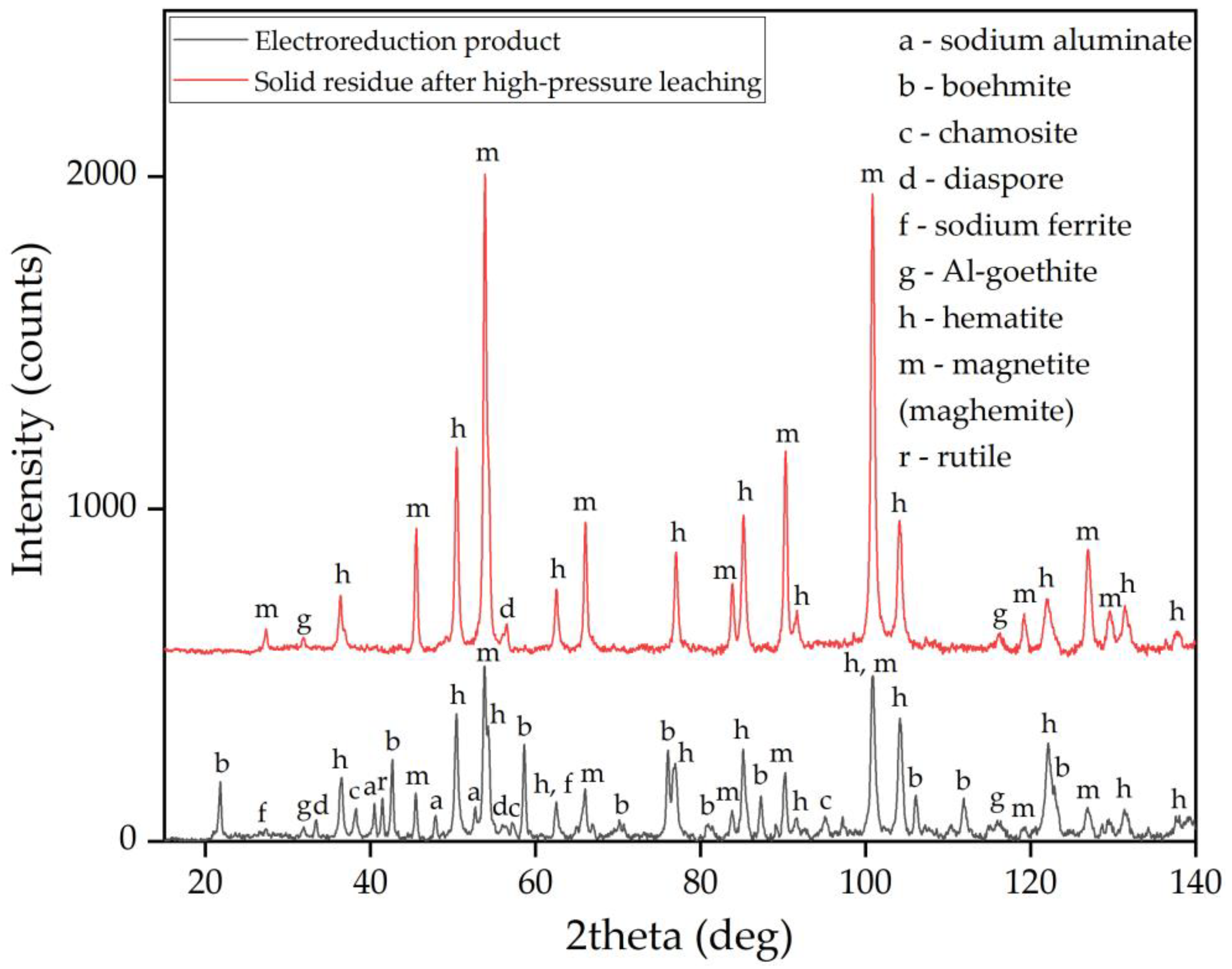

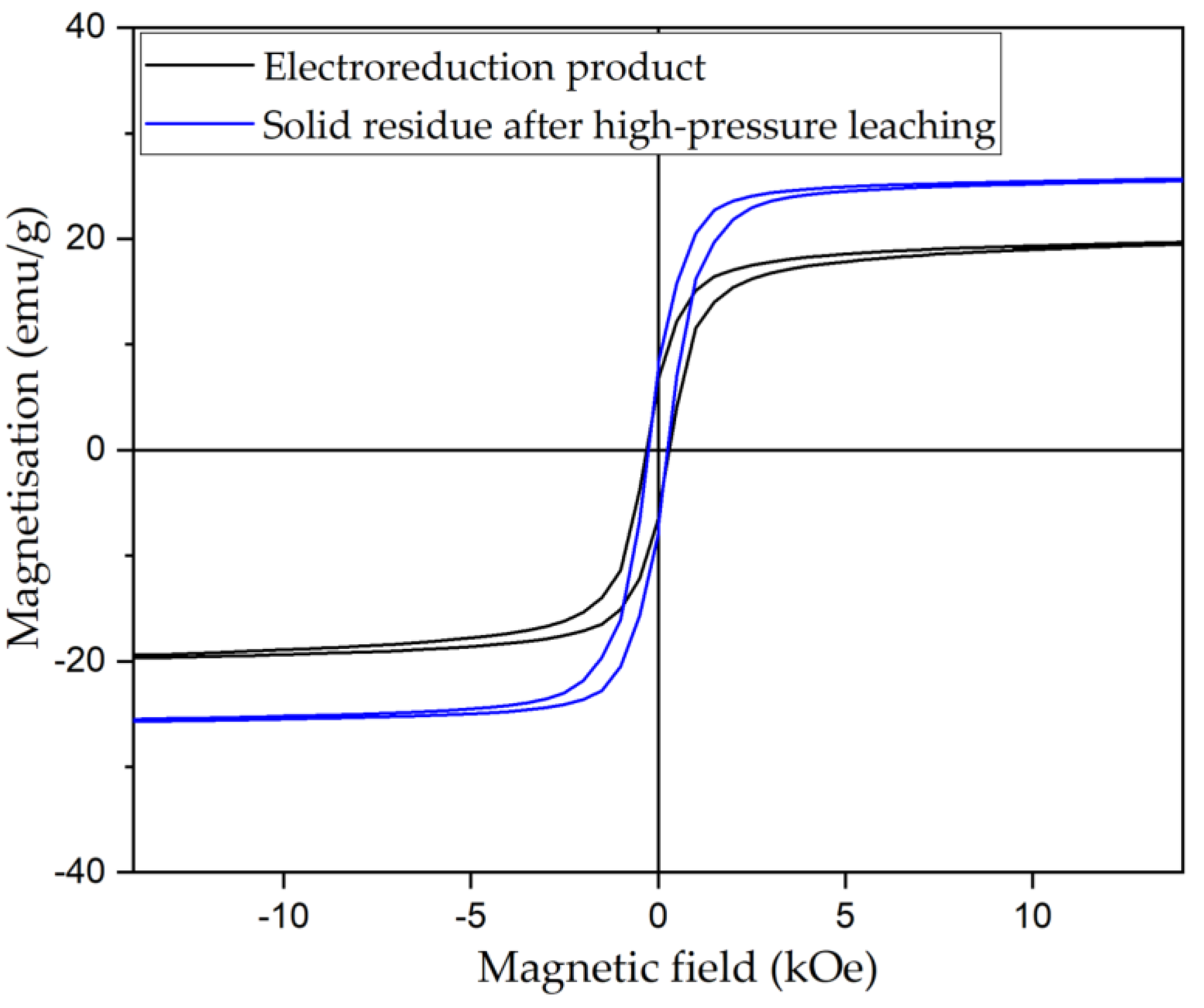

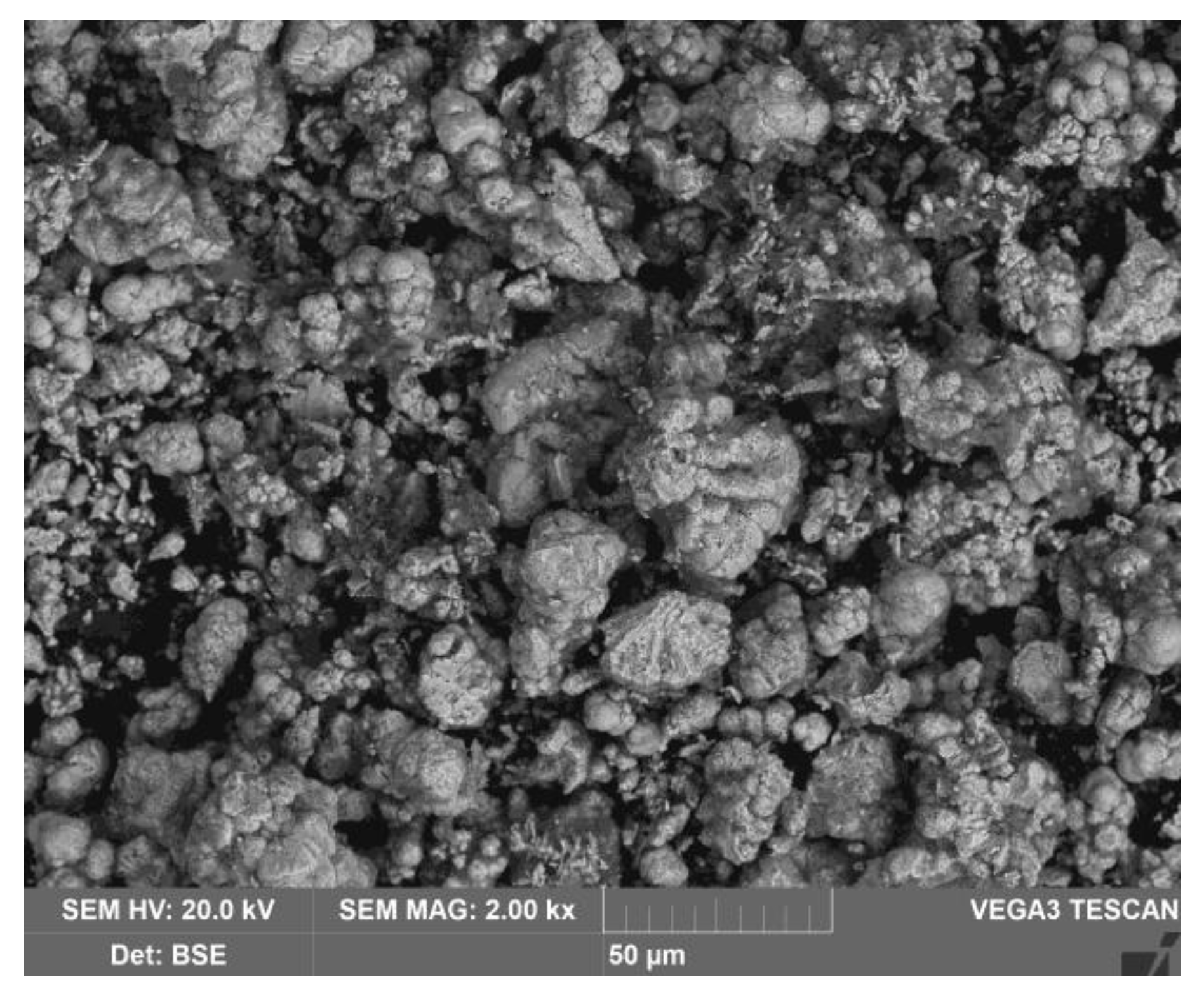

3.4. Solid Products Characterization

4. Conclusions

- According to Mössbauer and XRD studies, the raw bauxite composition includes hematite, alumohematite, alumogoethite and chamosite.

- Preliminary thermodynamic studies have shown that the highest iron concentration in solution can be achieved when an alkaline solution comes into contact with chamosite (up to 3.1×10−3 M). An increase in iron concentration shifts the zone of complex anion existence to a strongly alkaline environment.

- Cyclic voltammetry showed that, during the initial stage of electrolysis, overvoltage at the cathode decreases due to the formation of metallic iron and conductive magnetite on the surface of the electrode. After 50–60 min of electrolysis, the overvoltage begins to increase.

- After 60 min of electrolysis, the reduction efficiency also begins to decrease. The proportion of the current used for magnetization and iron deposition on the cathode decreased from 89.5% after 30 min to 67.5% (23.9% of which was used for iron deposition) after 120 min.

- Examining the electrolysis product using SEM-EDS revealed the formation of dense, iron-containing phase on the surface of the particles, which prevented outward diffusion of the reaction products.

- Mössbauer studies of the high-pressure leaching product showed that the main iron-containing phases of BR are maghemite, which is formed during the hydrolysis of sodium ferrite.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BR | Bauxite residue |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| XRD | X-Ray diffraction |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning electron microscopy with the energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis |

References

- Li, Q.; Lv, G.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; He, X.; Zhang, T. Summary of Research Progress on the Separation and Extraction of Iron from Bayer Red Mud. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 186–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. The Processing of High Silica Bauxites — Review of Existing and Potential Processes. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 98, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yu, H.; Tu, G.; Bi, S. Effects of Precipitation Activity of Desilication Products (DSPs) on Stability of Sodium Aluminate Solution. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 165, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Phase Transformation of Desilication Products in Red Mud Dealkalization Process. J. Sustain. Metall. 2022, 8, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T. Approaches to Improve Alumina Extraction Based on the Phase Transformation Mechanism of Recovering Alkali and Extracting Alumina by the Calcification-Carbonization Method. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 189, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Lyu, G.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W. Multi-Material Circulation Optimization of the Calcification-Carbonation Process Based on Material Balance and Phase Transformation for Cleaner Production of Alumina. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 290, 125828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, V.V.; Akhmedov, S.N.; Lipin, V.A. Hydrogarnet Process as a Modern Approach to Hydrometallurgical Alkaline Processing of Low-Grade Bauxites. Review. tsm 2023, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hond, R.D.; Hiralal, I.; Rijkeboer, A. Alumina Yield in the Bayer Process Past, Present and Prospects. In Essential Readings in Light Metals; Donaldson, D., Raahauge, B.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, pp. 528–533, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-64786-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenia, C.; Balomenos, E.; Wai Yin Tam, P.; Panias, D. A Combined Soda Sintering and Microwave Reductive Roasting Process of Bauxite Residue for Iron Recovery. Minerals 2021, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Cai, W.; Shi, Y.; Hui, X.; Cai, Z.; Jin, W.; Fan, J. High-Efficiency Extraction of Aluminum from Low-Grade Kaolin via a Novel Low-Temperature Activation Method for the Preparation of Poly-Aluminum-Ferric-Sulfate Coagulant. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 257, 120399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, W.M.; Burke, I.T.; Gomes, H.I.; Anton, Á.D.; Molnár, M.; Feigl, V.; Ujaczki, É. Advances in Understanding Environmental Risks of Red Mud After the Ajka Spill, Hungary. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy 2016, 2, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, F.; Isworo, G.; Mahaputra, R.; Pintowantoro, S. Possible Strategies for Red Mud Neutralization and Dealkalization from the Alumina Production Industry: A Review for Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 5159–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anawati, J.; Azimi, G. Integrated Carbothermic Smelting – Acid Baking – Water Leaching Process for Extraction of Scandium, Aluminum, and Iron from Bauxite Residue. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 330, 129905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, P.; Oustadakis, P.; Kountouris, N.; Samouhos, M.; Anastassakis, G.; Taxiarchou, M. Iron Recovery from Turkish and Romanian Bauxite Residues Through Magnetic Separation: Effect of Hydrothermal Processing and Separation Conditions. Separations 2025, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Nimje, M. t.; Chaddha, M. j.; Modak, S.; Rao, K. r.; Agnihotri, A. Recovery of Iron from Bauxite Residue Using Advanced Separation Techniques. Minerals Engineering 2019, 134, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra, C.R.; Blanpain, B.; Pontikes, Y.; Binnemans, K.; Van Gerven, T. Recovery of Rare Earths and Other Valuable Metals From Bauxite Residue (Red Mud): A Review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2016, 2, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Dhawan, N. Investigation of Carbothermic Microwave Reduction Followed by Acid Leaching for Recovery of Iron and Aluminum Values from Indian Red Mud. Minerals Engineering 2020, 159, 106653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopic, S.; Kostić, D.; Schneider, R.; Sievers, M.; Wegmann, F.; Emil Kaya, E.; Perušić, M.; Friedrich, B. Recovery of Titanium from Red Mud Using Carbothermic Reduction and High Pressure Leaching of the Slag in an Autoclave. Minerals 2024, 14, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhang, J.; Deng, X.; Wang, K.; He, C.; Li, X.; Wei, Y. Comprehensive Recovery of Iron and Aluminum from Ordinary Bayer Red Mud by Reductive Sintering–Magnetic Separation–Digesting Process. JOM 2019, 71, 2936–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, B.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Pi, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, M. Reduction of Red Mud Discharge by Reductive Bayer Digestion: A Comparative Study and Industrial Validation. JOM 2020, 72, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lv, G.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yun, Z.; Zhang, T. Straw-Induced Hematite-to-Magnetite Conversion in Alkaline Media: Experimental Study and Potential in Bayer Process. Minerals Engineering 2025, 234, 109723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihatchi, A.; Pons, M.-N.; Ricoux, Q.; Goettmann, F.; Lapicque, F. Electrolytic Iron Production from Alkaline Suspensions of Solid Oxides: Compared Cases of Hematite, Iron Ore and Iron-Rich Bayer Process Residues. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 10, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoupa, S.; Koutalidi, S.; Bourbos, E.; Balomenos, E.; Panias, D. Electrolytic Iron Production from Alkaline Bauxite Residue Slurries at Low Temperatures : Carbon-Free Electrochemical Process for the Production of Metallic Iron. Johnson Matthey Technology Review 2021, 65, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoppert, A.; Valeev, D.; Loginova, I. Novel Method of Bauxite Treatment Using Electroreductive Bayer Process. Metals 2023, 13, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsnev, M.E.; Rusakov, V.S. SpectrRelax: An Application for Mцssbauer Spectra Modeling and Fitting. AIP Conference Proceedings 2012, 1489, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, P.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, W. Advances in Reagent Systems and Mechanisms for Desilication from Bauxite via Flotation. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2025, 41, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.H.; Srivastava, K.K.P. Many-State Relaxation Model for the Mössbauer Spectra of Superparamagnets. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 7542–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzeranov, A.; Bondarenko, L.; Pankratov, D.; Dzhardimalieva, G.; Jorobekova, S.; Saman, D.; Kydralieva, K. Impact of Silica-Modification and Oxidation on the Crystal Structure of Magnetite Nanoparticles. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva, E.O.; German, S.V.; Komlev, A.S.; Rusakov, V.S.; Zuev, V.V.; Pavlova, O.S.; Perepukhov, A.M.; Dmitrienko, A.O.; Maslakov, K.I.; Griaznova, O.Y.; et al. Citrate Stabilized Maghemite Hydrosol with Controllable MRI Contrast: Key Role of Nanoparticle Size. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2024, 608, 172447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, C.S. Mössbauer Studies on the Superparamagnetic Behavior of CoFe2O4 with a Few Nanometers. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2006, 303, e315–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, W. Mössbauer Studies of Small Magnetite Particles of a Magnetic Fluid. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 1984, 84, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoppert, A.; Valeev, D.; Loginova, I.; Pankratov, D. Low-Temperature Treatment of Boehmitic Bauxite Using the Bayer Reductive Method with the Formation of High-Iron Magnetite Concentrate. Materials 2023, 16, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fysh, S.A.; Clark, P.E. Aluminous Hematite: A M�ssbauer Study. Phys Chem Minerals 1982, 8, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grave, E.; Bowen, L.H.; Weed, S.B. Mössbauer Study of Aluminum-Substituted Hematites. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1982, 27, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji-Sen, J.; Xie-Long, Y.; Long-Wu, C.; Nai-Fu, Z. Mössbauer Studies of the Morin Transition Interval of Uniform Hematite Particles. Hyperfine Interact 1988, 41, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, H.; Fujita, A.; Yamamoto, H.; Sagawa, M.; Hirosawa, S. Mössbauer Study of the Intermetallic Compound Nd2Fe14B. I. Interpretation of Complex Spectrum. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1987, 68, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokanov, A.; Vereshchak, M.; Manakova, I.; Migunova, A. Mössbauer and X-Ray Diffraction Spectroscopy of High-Iron Bauxites from Kazakhstan. Materials 2023, 16, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.V.; Ivanova, Yu.A.; Kovalevsky, A.V.; Sarabando, A.R.; Frade, J.R.; Quina, M.J. Electrochemical Reduction of Hematite-Based Ceramics in Alkaline Medium: Challenges in Electrode Design. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 327, 135060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.F.; Ivanova, Yu.A.; Kovalevsky, A.V.; Ivanou, D.K.; Frade, J.R. Reduction of Magnetite to Metallic Iron in Strong Alkaline Medium. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 193, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicheeva, A.G.; Sushko, E.S.; Bondarenko, L.S.; Kydralieva, K.A.; Pankratov, D.A.; Tropskaya, N.S.; Dzeranov, A.A.; Dzhardimalieva, G.I.; Zarrelli, M.; Kudryasheva, N.S. Functionalized Magnetite Nanoparticles: Characterization, Bioeffects, and Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Unicellular and Enzymatic Systems. IJMS 2023, 24, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, C.A.; Scherer, M.M. Determination of Nanoparticulate Magnetite Stoichiometry by Mossbauer Spectroscopy, Acidic Dissolution, and Powder X-Ray Diffraction: A Critical Review. American Mineralogist 2010, 95, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Henao, J.M.; Muraca, D.; Sánchez, F.H.; Mendoza Zélis, P. Determination of the Effective Anisotropy of Magnetite/Maghemite Nanoparticles from Mössbauer Effect Spectra. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 335302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal, M.A.R.; Riaño, S.; Binnemans, K. Alkali Baking and Solvometallurgical Leaching of NdFeB Magnets. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 191, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratov, D.A.; Anuchina, M.M. Nature-Inspired Synthesis of Magnetic Non-Stoichiometric Fe3O4 Nanoparticles by Oxidative in Situ Method in a Humic Medium. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2019, 231, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.; Rozova, M.; Maksimov, S.; Pankratov, D. Synthesis and Redox Properties of Iron and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Obtained by Exsolution from Perovskite Ferrites Promoted by Auxiliary Reactions. Inorganics 2024, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Nasu, S.; Fujita, F.E.; Maeda, Y.; Yoshida, H. 57Fe Mössbauer Study on Point Defects in Pure α-Fe. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1983, 31–34, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudinsky, P.; Zinoveev, D.; Pankratov, D.; Semenov, A.; Panova, M.; Kondratiev, A.; Zakunov, A.; Dyubanov, V.; Petelin, A. Influence of Sodium Sulfate Addition on Iron Grain Growth during Carbothermic Roasting of Red Mud Samples with Different Basicity. Metals 2020, 10, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoshkalenko, V.V.; Rasumov, O.N.; Gorskii, V.V. Investigation of the Mössbauer Effect in Some Fe–Al Alloys. Physica Status Solidi (b) 1968, 29, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, I.; Campbell, I.A. Mossbauer Measurements in Iron Based Alloys with Transition Metals. Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics 1973, 3, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernavskii, P.A.; Kazantsev, R.V.; Pankina, G.V.; Pankratov, D.A.; Maksimov, S.V.; Eliseev, O.L. Unusual Effect of Support Carbonization on the Structure and Performance of Fe/Mgal2 o4 Fischer–Tropsch Catalyst. Energy Tech 2021, 9, 2000877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-W.; Zhao, S.; Meng, Y.; Peng, Q.; Dearden, A.K.; Huo, C.-F.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.-W.; Wen, X.-D. Mössbauer Spectroscopy of Iron Carbides: From Prediction to Experimental Confirmation. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.A.; Balogh, J.; Kuzmann, E. Mössbauer Study of (Fe1−xCox)77B13Si10 Amorphous Alloys. phys. stat. sol. (a) 1986, 96, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Cleaning Disposal of High-Iron Bauxite Residue Using Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2022, 109, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phase | wt.% |

|---|---|

| Boehmite | 62.3 |

| Hematite | 25.7 |

| Alumogoethite | 3.6 |

| Chamosite | 3.4 |

| Rutile | 2.6 |

| Diaspore | 2.4 |

| Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SiO2 | TiO2 | Na2O | CaO | MgO | SO3 | P2O5 | Other | µSi1 | LOI2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50.3 | 26.8 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 7.7 | 11.0 |

| Temperature, K | 296(3) | 77.7(3) | |||||||||||

| Sample | № | Phase | *δ | ε {Δ} | Γexp | Heff | S | α | δ | ε (Δ) | Γexp | Heff | S |

| mm/s | kOe | % | - | mm/s | kOe | % | |||||||

| Boehmitic bauxite | 1 | α-Fe(Al)2O3 | 0.37(1) | -0.11(1) | 0.28(1) | 509.9(3) | 27.9(2.5) | 0.48(1) | -0.10(1) | 0.30(1) | 528.1(2) | 44.4(8) | |

| 2 | α-Fe(Al)2O3 | 0.38(1) | -0.10(1) | 0.58(2) | 496.2(1.3) | 23.8(2.6) | |||||||

| 3 | α-Fe(Al)OOH | 0.33(2) | -0.12(2) | 0.54(7) | 390.8(2.1) | 14.2(6) | 3.2(3) | 0.48(1) | -0.11(1) | 0.74(3) | 499.9(6) | 26.7(1.0) | |

| 4 | Fe2+Oh | 1.13(1) | {2.65(1)} | 0.34(1) | 20.9(3) | 1.25(1) | {2.80(1)} | 0.31(1) | 21.0(3) | ||||

| 5 | Fe3+Oh | 0.39(1) | {0.67(1)} | 0.48(1) | 13.2(5) | 0.51(1) | {0.85(1)} | 0.53(2) | 7.9(3) | ||||

| Bauxite residue | 1 | α-Fe2O3 | 0.37(1) | -0.11(1) | 0.29(1) | 510.8(1) | 24.6(6) | 0.49(1) | -0.10(1) | 0.30(1) | 531.0(1) | 30.0(8) | |

| 2 | γ-Fe(Al)2O3 | 0.32(1) | -0.05(1) | 0.54(1) | 486.4(3) | 29.8(9) | 0.45(1) | -0.03(1) | 0.66(1) | 507.5(3) | 48(1) | ||

| 3 | γ-Fe(Al,M)2O3 | 0.59(1) | -0.03(1) | 0.66(2) | 473.3(9) | 40(1) | 6.4(3) | 0.82(1) | -0.15(1) | 0.97(5) | 472(1) | 18(1) | |

| 4 | α-Fe(Al,M)OOH | 0.28(6) | -0.12(5) | 0.66(2) | 387(4) | 3.4(5) | 0.74(4) | 0.01(4) | 0.7(2) | 405(3) | 2.9(7) | ||

| 5 | Fe3+Td | 0.22(3) | {0.78(6)} | 0.64(1) | 2.0(2) | 0.44(3) | {0.72(5)} | 0.36(7) | 1.1(1) | ||||

| Hematite (α-Fe2O3) | Temperature, °C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O concentration, g/L | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 |

| 300 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | -* |

| 400 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| 550 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Goethite (FeOOH) | Temperature, °C | |||

| Na2O concentration, g/L | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 |

| 300 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | - |

| 400 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| 550 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Chamosite ((Fe2+,Mg,Al,Fe3+)6(Si,Al)4O10(OH,O)8 | Temperature, °C | |||

| Na2O concentration, g/L | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 |

| 300 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | - |

| 400 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| 550 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| Sample | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SiO2 | TiO2 | Na2O | CaO | MgO | SO3 | P2O5 | Other | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroreduction product | 28.3 | 37.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 12.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 10.5 |

| BR | 10.2 | 61.9 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.8 | 6.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).