Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

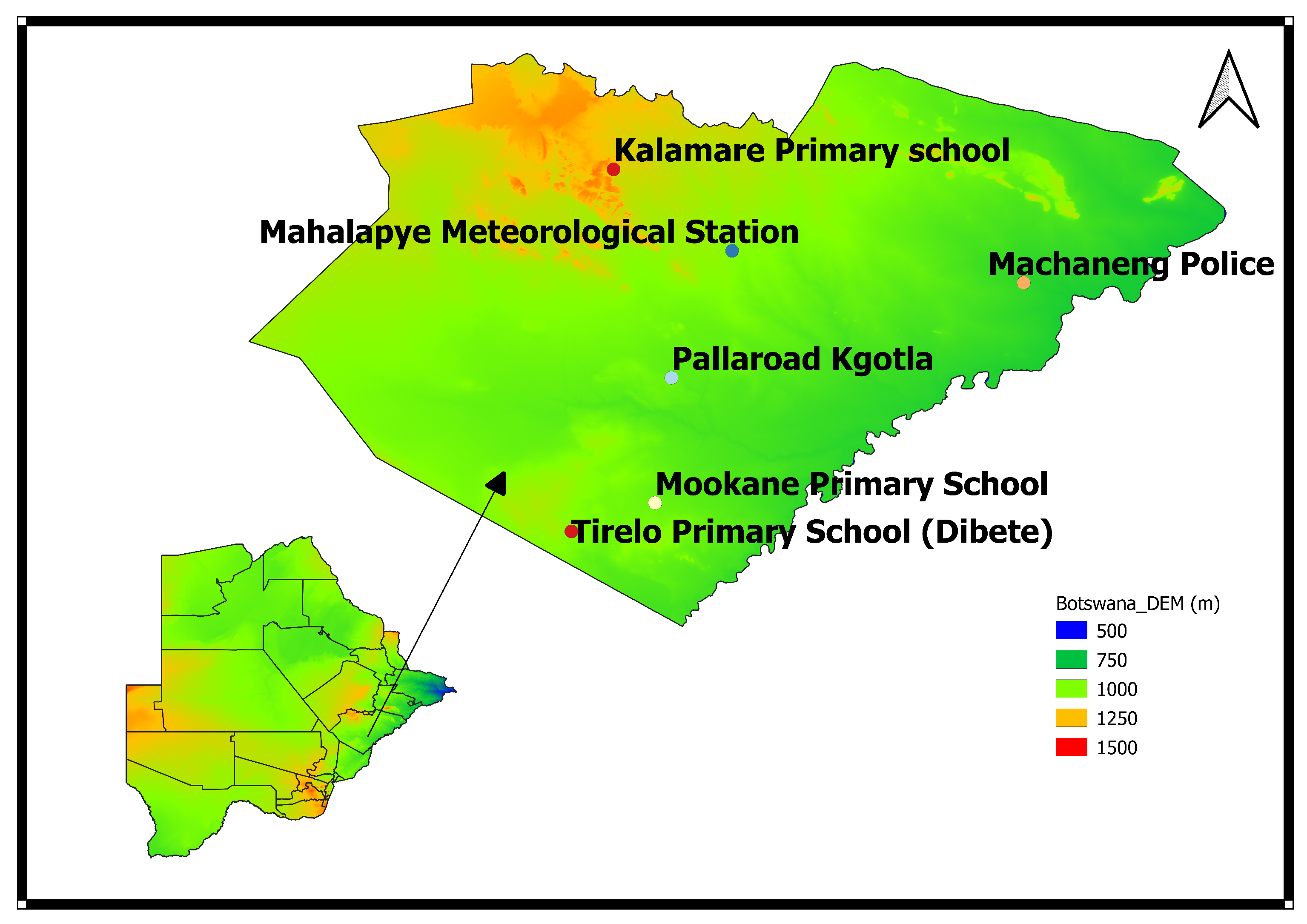

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Source of Data

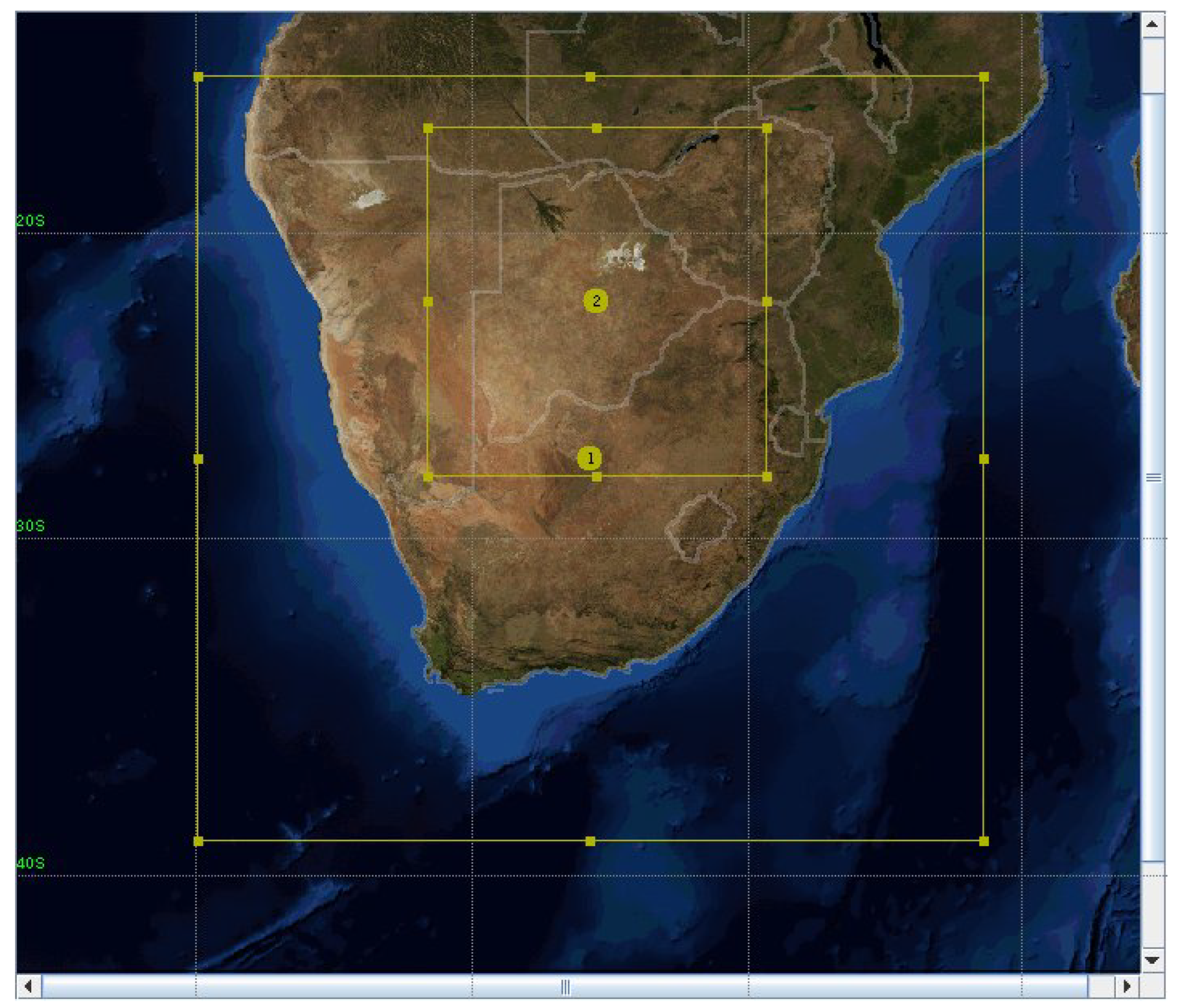

2.3. Numerical Study design

2.4. Model Evaluation Statistics

2.4.1. Root Mean Square Error

2.4.2. Percent Bias

2.4.3. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient

2.4.4. Probability of Detection

2.4.5. Kling-Gupta Efficiency

2.4.6. Haversine formula

3. Results and Discussion

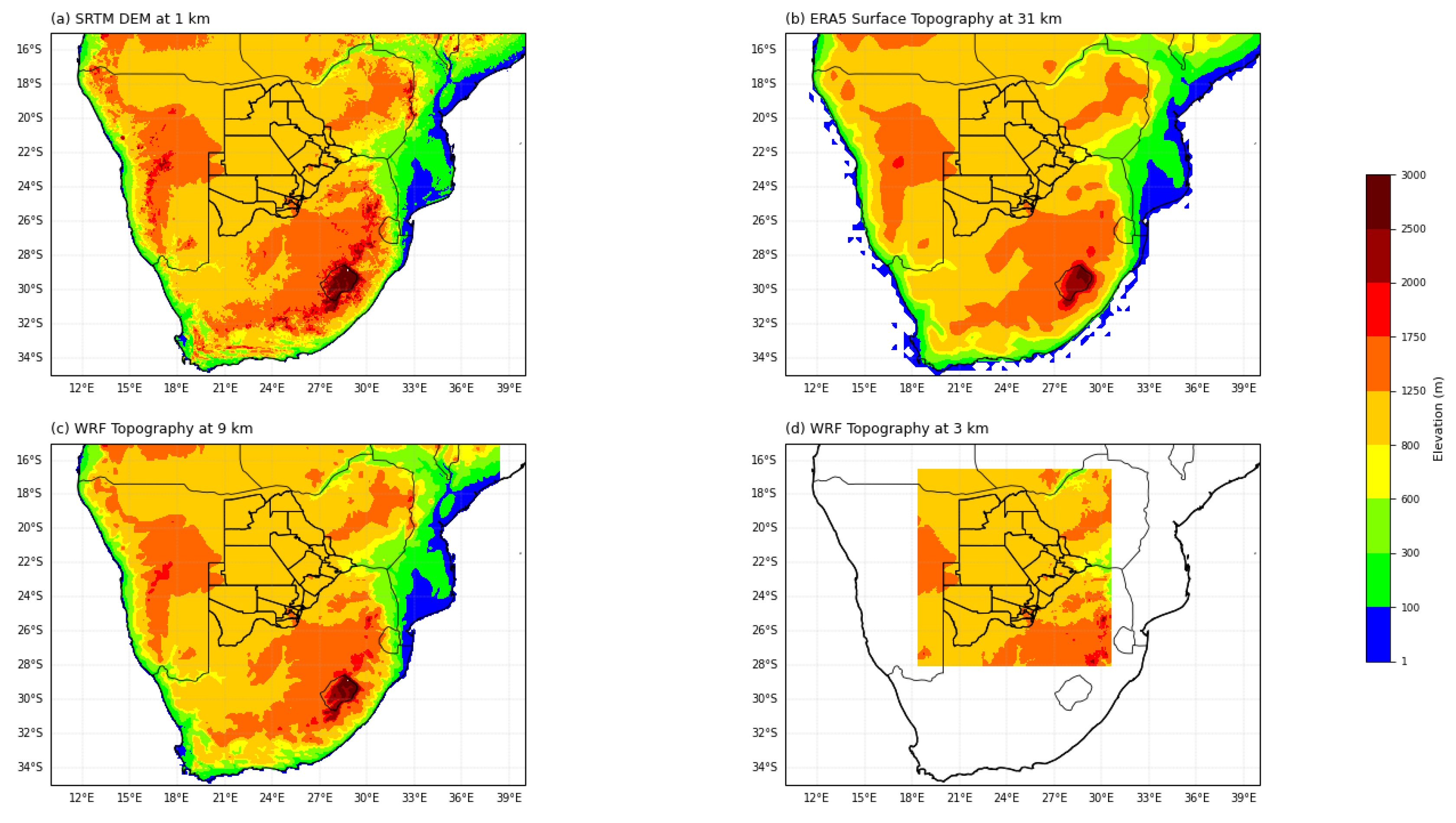

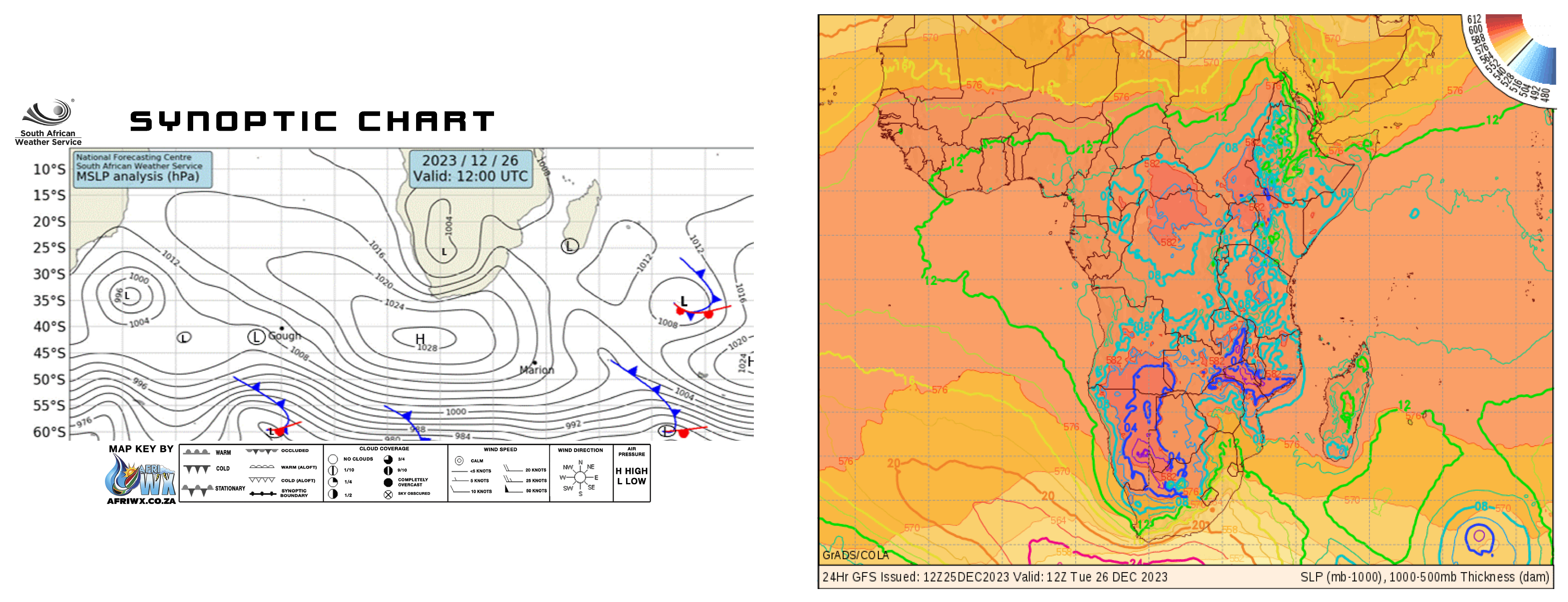

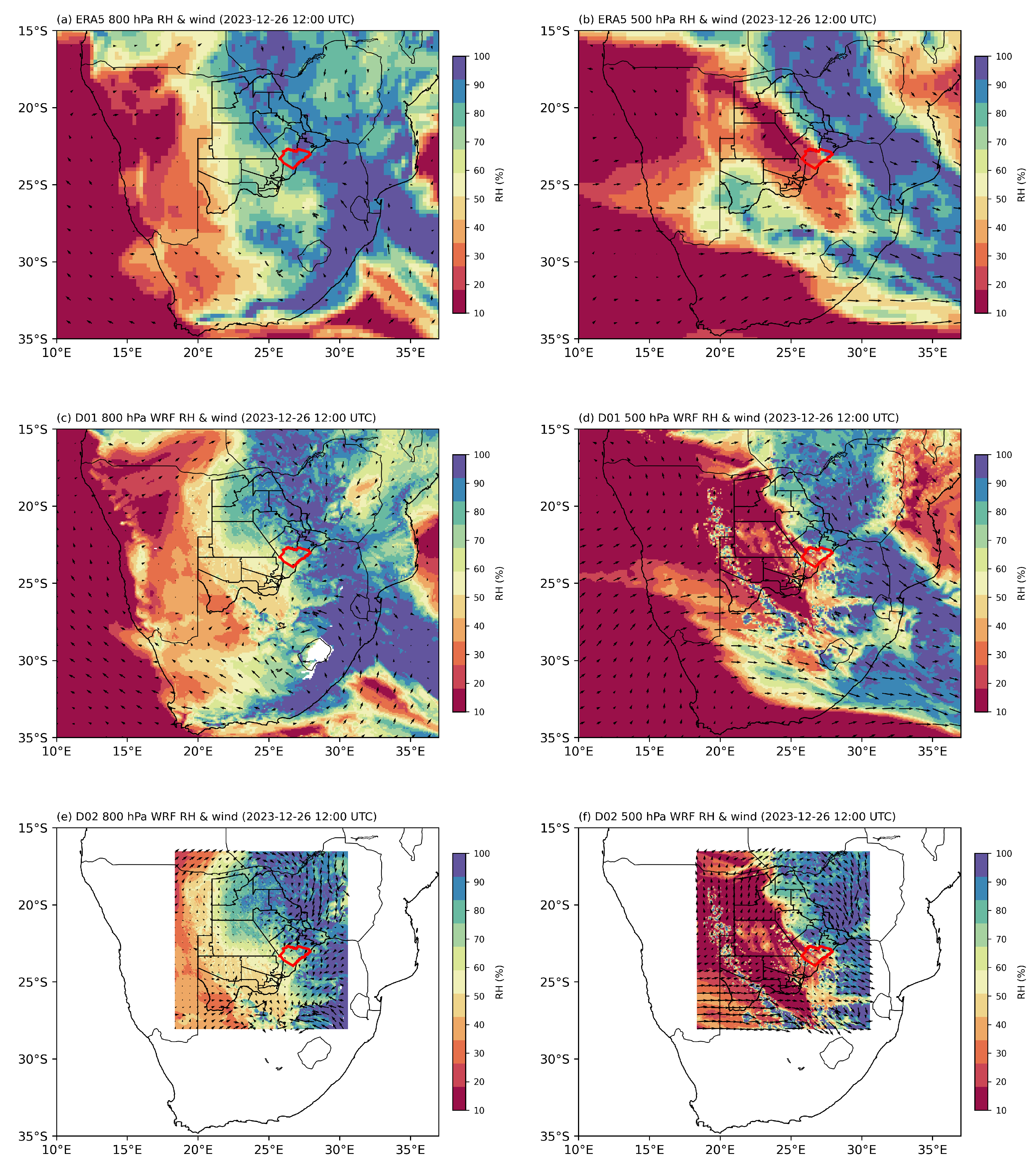

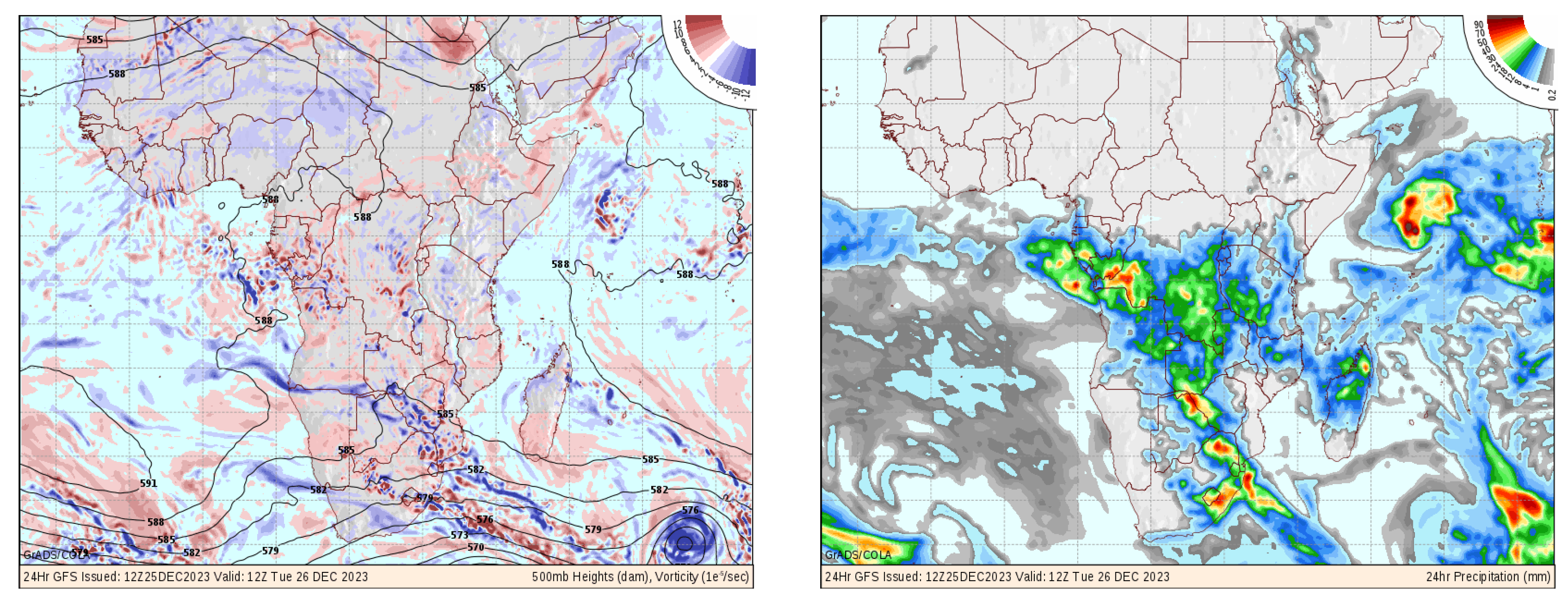

3.1. Interaction of Topography with Synoptic Systems

3.2. Synoptic Conditions Prevailing on the Day of Event: 26thDecember 2023.

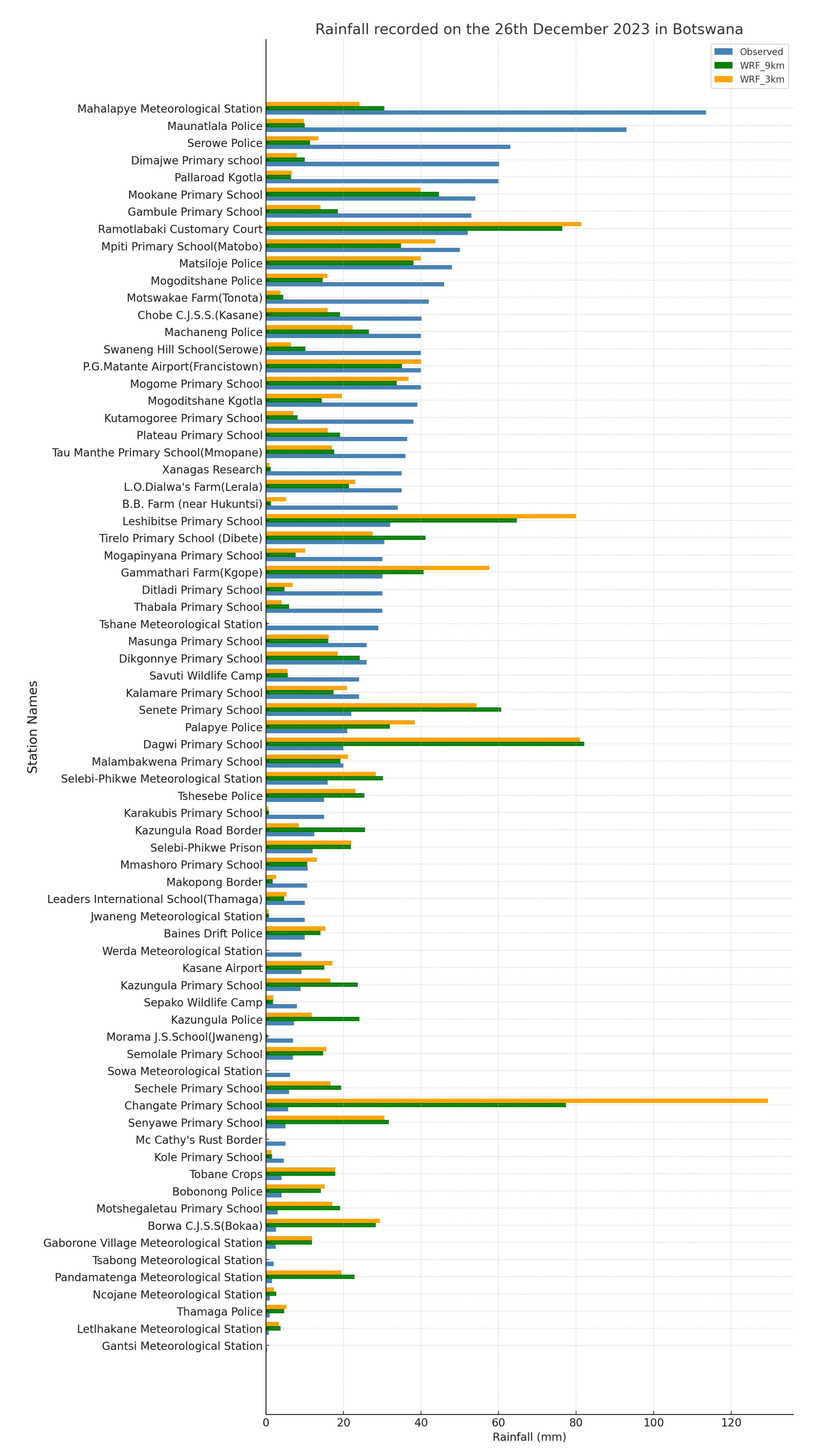

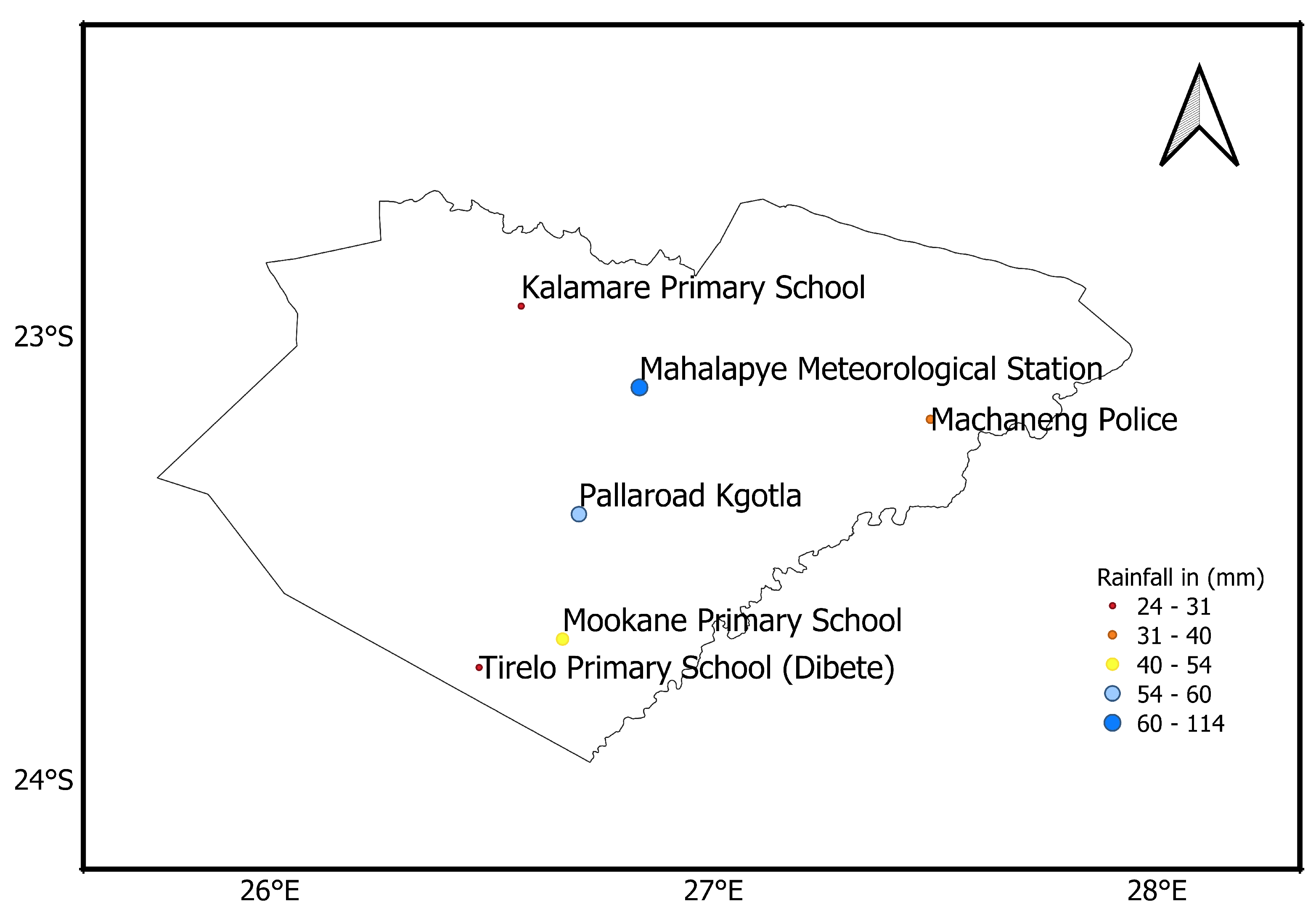

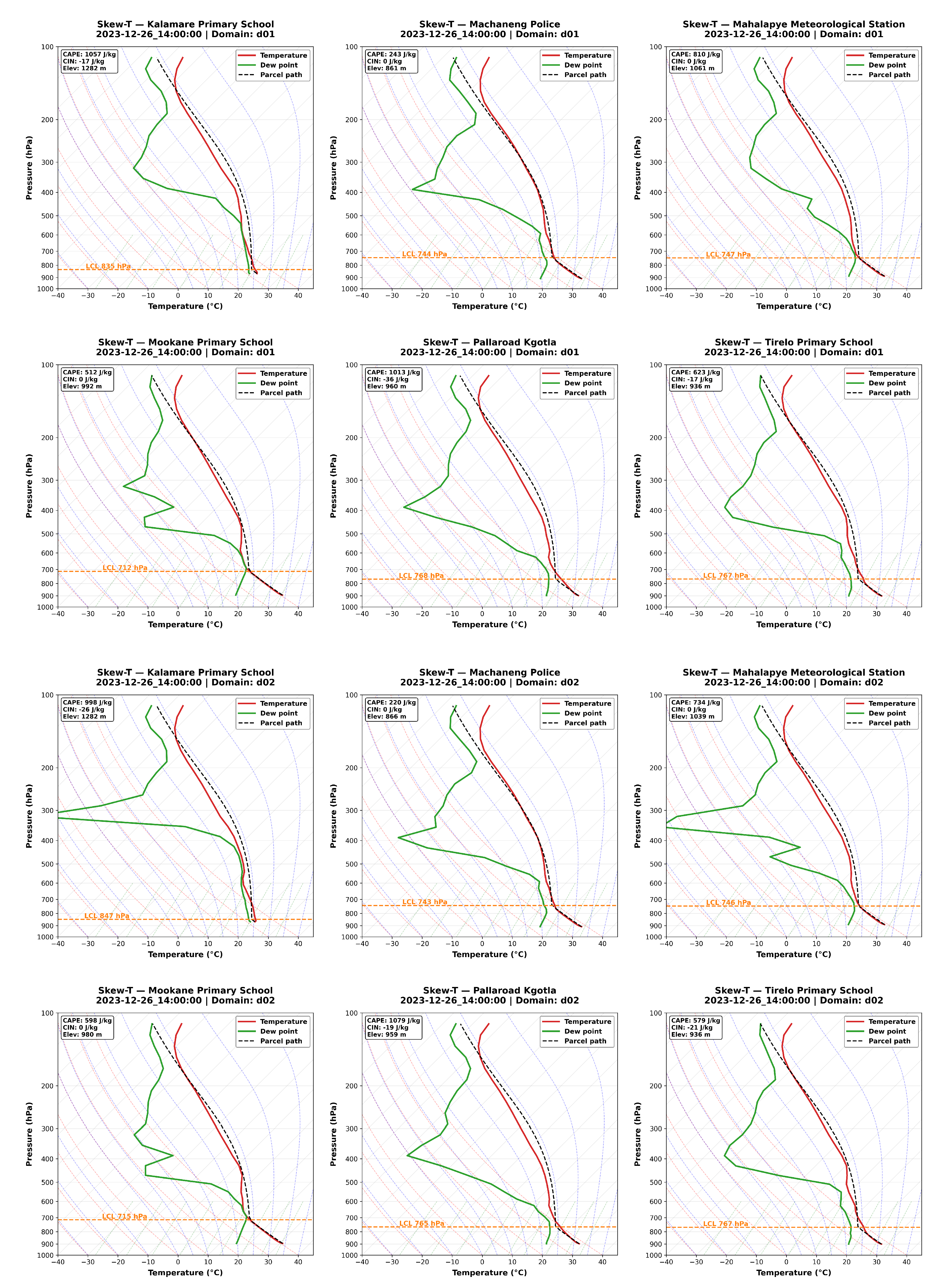

3.3. Observed Precipitation from DMS

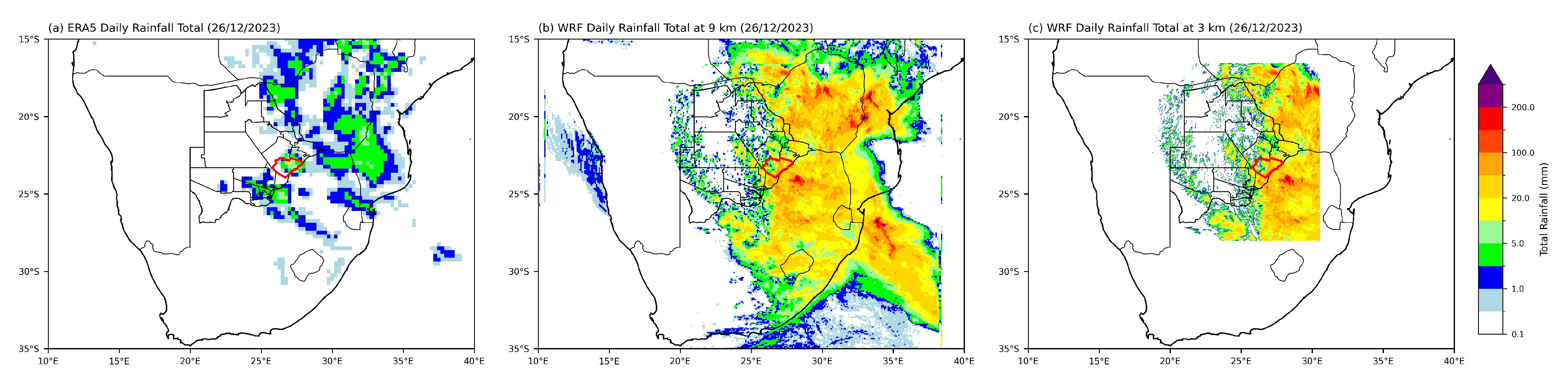

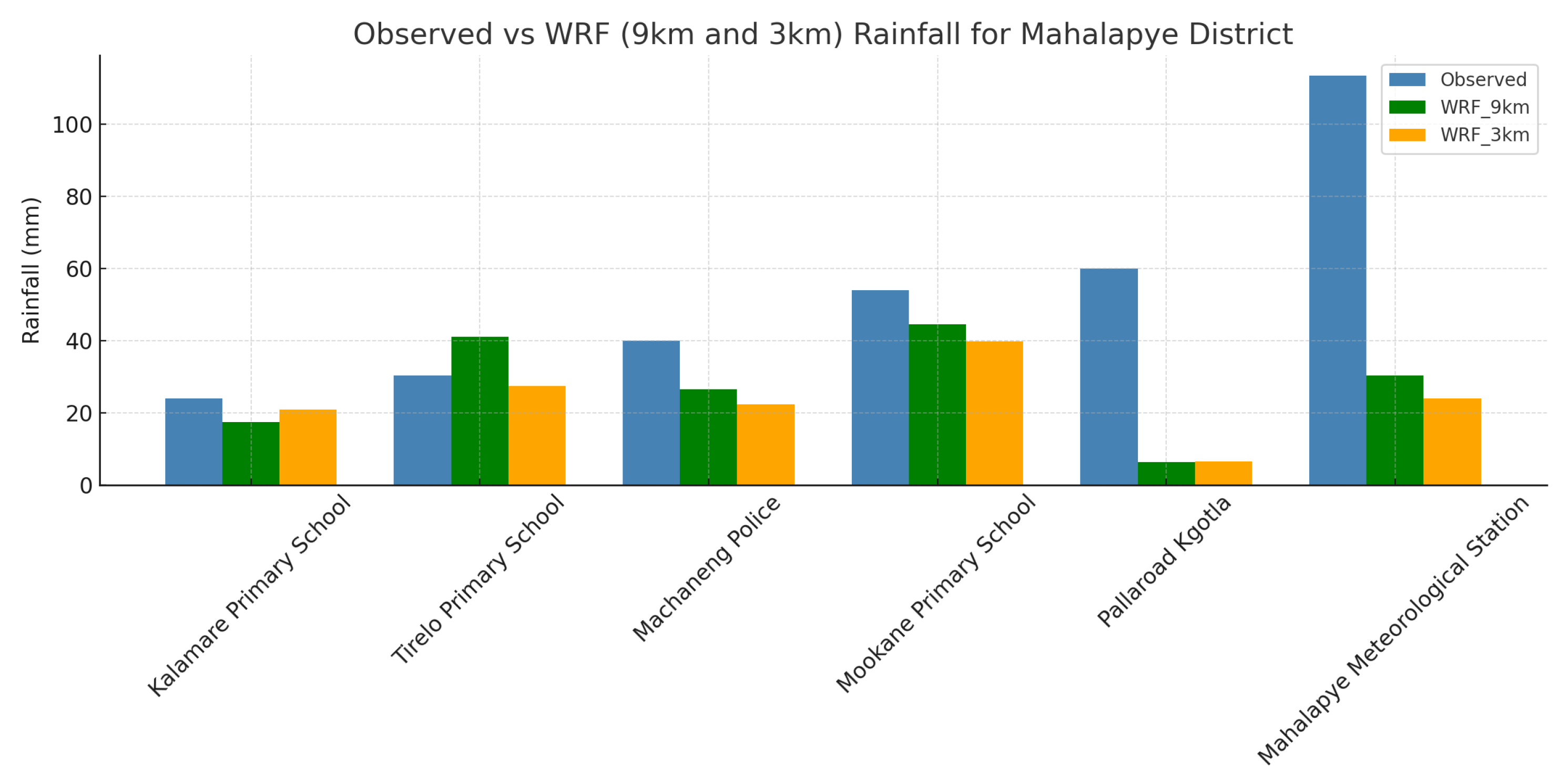

3.4. WRF Evaluation

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A.

References

- McPhillips, L.E.; Chang, H.; Chester, M.V.; Depietri, Y.; Friedman, E.; Grimm, N.B.; Kominoski, J.S.; McPhearson, T.; Méndez-Lázaro, P.; Rosi, E.J.; et al. Defining extreme events: A cross-disciplinary review. *Earth’s Future* **2018**, *6*(3), 441–455. [CrossRef]

- Batisani, N.; Yarnal, B. Rainfall variability and trends in semi-arid Botswana: Implications for climate change adaptation policy. *Applied Geography* **2010**, *30*(4), 483–489. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Botswana. *Botswana Environment Statistics: Natural and Technological Disasters Digest 2019*; Statistics Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 2020.

- Mmopelwa, G.; Moalafhi, D.B.; Hambira, W.L.; Dhliwayo, M.; Motau, A. The impact of flooding on the community: A case of Gweta and Zoroga Villages, Botswana. *African Journal of Climate Change and Resource Sustainability* **2023**, *2*(1), 132–152. [CrossRef]

- Motsholapheko, M.R.; Kgathi, D.L.; Vanderpost, C. Rural livelihoods and household adaptation to extreme flooding in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. *Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C* **2011**, *36*(14–15), 984–995. [CrossRef]

- Tsheko, R. Rainfall reliability, drought and flood vulnerability in Botswana. *Water SA* **2003**, *29*(4), 389–392. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, G.; Mulalu, M.I.; Moalafhi, D.B.; Stephens, M. Evaluation of national disaster management strategy and planning for flood management and impact reduction in Gaborone, Botswana. *International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction* **2022**, *74*, 102939. [CrossRef]

- Moses, O. Weather systems influencing Botswana rainfall: The case of 9 December 2018 storm in Mahalapye, Botswana. *Modeling Earth Systems and Environment* **2019**, *5*(4), 1473–1480. [CrossRef]

- Aravind, A.; Srinivas, C.V.; Hegde, M.N.; Seshadri, H.; Mohapatra, D.K. Impact of land surface processes on the simulation of sea breeze circulation and tritium dispersion over the Kaiga complex terrain region near west coast of India using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model. *Atmospheric Environment: X* **2022**, *13*, 100149. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F. Simulation of regional climate using a limited area model nested in a general circulation model. *Journal of Climate* **1990**, *3*(9), 941–963. [CrossRef]

- Maisha, T.R. The Influence of Topography and Model Grid Resolution on Extreme Weather Forecasts over South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2014.

- Reason, C.J.C.; Landman, W.; Tennant, W. Seasonal to decadal prediction of southern African climate and its links with variability of the Atlantic Ocean. *Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society* **2006**, *87*(7), 941–956. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F. Regional climate modeling: Status and perspectives. *Journal de Physique IV (Proceedings)* **2006**, *139*, 101–118. [CrossRef]

- Kgatuke, M.M.; Landman, W.A.; Beraki, A.; Mbedzi, M.P. The internal variability of the RegCM3 over South Africa. *International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society* **2008**, *28*(4), 505–520. [CrossRef]

- Feser, F.; Rockel, B.; von Storch, H.; Winterfeldt, J.; Zahn, M. Regional climate models add value to global model data: a review and selected examples. *Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society* **2011**, *92*(9), 1181–1192. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Han, Y.; Yang, Z. Dynamical downscaling of regional climate: A review of methods and limitations. *Science China Earth Sciences* **2019**, *62*, 365–375. [CrossRef]

- Rummukainen, M. State-of-the-art with regional climate models. *Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change* **2010**, *1*(1), 82–96.

- Wang, Y.; Leung, L.R.; McGregor, J.L.; Lee, D.K.; Wang, W.C.; Ding, Y.; Kimura, F. Regional climate modeling: Progress, challenges, and prospects. *Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. Ser. II* **2004**, *82*(6), 1599–1628. [CrossRef]

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.M.; et al. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Version 4; NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-556+STR; National Center for Atmospheric Research: Boulder, CO, USA, 2019.

- Ratna, S.B.; Ratnam, J.V.; Behera, S.K.; Rautenbach, C.J.d.W.; Ndarana, T.; Takahashi, K.; Yamagata, T. Performance assessment of three convective parameterization schemes in WRF for downscaling summer rainfall over South Africa. *Climate Dynamics* **2014**, *42*, 2931–2953. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoglio, P.; Parodi, A.; Parodi, A. Detecting Extreme Rainfall Events Using the WRF-ERDS Workflow: The 15 July 2020 Palermo Case Study. *Water* **2022**, *14*(1), 86.

- Bafitlhile, T.M.; Oladele, A.S. Modeling Extreme Flood Events for Palapye, Botswana. *BIE Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences* **2015**, *6*(1), 54–60.

- Chawla, I.; Osuri, K.K.; Mujumdar, P.P.; Niyogi, D. Assessment of the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model for simulation of extreme rainfall events in the upper Ganga Basin. *Hydrology and Earth System Sciences* **2018**, *22*(2), 1095–1117. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.-Y.; Bi, X.-Q. Validation for a tropical belt version of WRF: Sensitivity tests on radiation and cumulus convection parameterizations. *Atmospheric and Oceanic Science Letters* **2019**, *12*(3), 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Meroni, A.N.; Oundo, K.A.; Muita, R.; Bopape, M.-J.; Maisha, T.R.; Lagasio, M.; Parodi, A.; Venuti, G. Sensitivity of some African heavy rainfall events to microphysics and planetary boundary layer schemes: Impacts on localised storms. *Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society* **2021**, *147*(737), 2448–2468. [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, P.S. Study of the influence of gust fronts and topographical features in the development of severe thunderstorms across South Africa. *University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg* **2024**.

- Maisha, T.; Mulovhedzi, P.T.; Rambuwani, G.T.; Makgati, L.N.; Barnes, M.; Lekoloane, L.; Engelbrecht, F.A.; Ndarana, T.; Mbokodo, I.L.; Xulu, N.G.; et al. The development of a locally based weather and climate model in Southern Africa. *Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa* **2025**, 1–197.

- Molongwane, C.; Bopape, M.-J.M.; Fridlind, A.; Motshegwa, T.; Matsui, T.; Phaduli, E.; Sehurutshi, B.; Maisha, R. Sensitivity of Botswana Ex-Tropical Cyclone Dineo rainfall simulations to cloud microphysics scheme. *AAS Open Research* **2020**, *3*, 30. [CrossRef]

- Mathafeni, T.P.; Osupile, O.; Maripe, K. Hazard Early Warning Systems in Botswana: A Social Work Perspective. *International Journal of Health and Medical Information* **2015**, *4*(1), 9–22.

- Statistics Botswana. Botswana Population and Housing Census 2022. *Government of Botswana Publications* **2022**. Accessed via Botswana Bureau of Statistics.

- Kumar, P.; Kishtawal, C.M.; Pal, P.K. Impact of ECMWF, NCEP, and NCMRWF global model analysis on the WRF model forecast over Indian Region. *Theoretical and Applied Climatology* **2017**, *127*, 143–151. [CrossRef]

- Taszarek, M.; Pilguj, N.; Orlikowski, J.; Surowiecki, A.; Walczakiewicz, S.; Pilorz, W.; Piasecki, K.; Pajurek, Ł.; Półrolniczak, M. Derecho evolving from a mesocyclone—A study of 11 August 2017 severe weather outbreak in Poland: Event analysis and high-resolution simulation. *Monthly Weather Review* **2019**, *147*(6), 2283–2306. [CrossRef]

- Figurski, M.J.; Nykiel, G.; Jaczewski, A.; Bałdysz, Z.; Wdowikowski, M. The impact of initial and boundary conditions on severe weather event simulations using a high-resolution WRF model. Case study of the derecho event in Poland on 11 August 2017. *Meteorology Hydrology and Water Management. Research and Operational Applications* **2022**, *10*. [CrossRef]

- Nkoni, G.; Mphale, K.; Mbangiwa, N.; Samuel, S.; Molosiwa, R. Use of multivariate techniques to regionalize rainfall patterns in semiarid Botswana. *Discover Environment* **2024**, *2*(1), 77. [CrossRef]

- Alemaw, B.F.; Chaoka, R.T. ; Others. Regionalization of rainfall intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curves in Botswana. *Journal of Water Resource and Protection* **2016**, *8*(12), 1128. [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, F.O. Climate change and variability in semiarid Palapye, Eastern Botswana: An assessment from smallholder farmers’ perspective. *Weather, Climate, and Society* **2017**, *9*(3), 349–365. [CrossRef]

- Matenge, R.G.; Parida, B.P.; Letshwenyo, M.W.; Ditalelo, G. Impact of climate variability on rainfall characteristics in the semi-arid Shashe Catchment (Botswana) from 1981–2050. *Earth* **2023**, *4*(2), 398–441. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. *The ERA5 Global Reanalysis*; *Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society* **2020**, *146*(730), 1999–2049. Wiley Online Library. [CrossRef]

- Mbokodo, I.L.; Burger, R.P.; Fridlind, A.; Ndarana, T.; Maisha, R.; Chikoore, H.; Bopape, M.-J.M. *Assessing the Performance of the WRF Model in Simulating Squall Line Processes over the South African Highveld*; *Atmosphere* **2025**, *16*(9), 1055. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Bopape, M.-J.M.; Engelbrecht, F.A.; Maisha, R.; Chikoore, H.; Ndarana, T.; Lekoloane, L.; Thatcher, M.; Mulovhedzi, P.T.; Rambuwani, G.T.; Barnes, M.A.; et al. *Rainfall Simulations of High-Impact Weather in South Africa with the Conformal Cubic Atmospheric Model (CCAM)*; *Atmosphere* **2022**, *13*(12), 1987. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Dee, D.P.; Uppala, S.M.; Simmons, A.J.; Berrisford, P.; Poli, P.; Kobayashi, S.; Andrae, U.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Balsamo, G.; Bauer, P.; et al. *The ERA-Interim Reanalysis: Configuration and Performance of the Data Assimilation System*; *Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society* **2011**, *137*(656), 553–597. Wiley Online Library. [CrossRef]

- Steinkopf, J.; Engelbrecht, F. *Verification of ERA5 and ERA-Interim Precipitation over Africa at Intra-Annual and Interannual Timescales*; *Atmospheric Research* **2022**, *280*, 106427. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. WRF: More Runtime Options. *WRF Tutorial* **2017**, *46*, UNSW Sydney, NSW, Australia.

- Iacono, M.J.; Delamere, J.S.; Mlawer, E.J.; Shephard, M.W.; Clough, S.A.; Collins, W.D. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: Calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. *J. Geophys. Res. Atmos.* **2008**, *113*, D13. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Noh, Y.; Dudhia, J. A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. *Mon. Weather Rev.* **2006**, *134*, 2318–2341. [CrossRef]

- Tewari, M. Implementation and Verification of the Unified NOAH Land Surface Model in the WRF Model. 2004. Available online: https://ral.ucar.edu/projects/wrf/users/docs/WRF-ARWPhysiology.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. Projected future changes of tropical cyclone activity over the western North and South Pacific in a 20-km-mesh regional climate model. *J. Clim.* **2017**, *30*, 5923–5941. [CrossRef]

- Oyegbile, O.; Chan, A.; Ooi, M.; Anwar, P.; Mohamed, A.A.; Li, L. Evaluation of WRF model performance with different microphysics schemes for extreme rainfall prediction in Lagos, Nigeria: Implications for urban flood risk management. *Bull. Atmos. Sci. Technol.* **2024**, *5*, 19. [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?—Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. *Geosci. Model Dev.* **2014**, *7*, 1247–1250. [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.; Arnold, J.; Van Liew, M.; Bingner, R.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. *Trans. ASABE* **2007**, *50*, 885–900. [CrossRef]

- Legates, D.R.; McCabe, G.J. Evaluating the use of “goodness-of-fit” measures in hydrologic and hydroclimatic model validation. *Water Resour. Res.* **1999**, *35*, 233–241.

- Wilks, D.S. *Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences*, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 100, International Geophysics Series.

- Gupta, H.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.; Martinez, G. Decomposition of the Mean Squared Error and NSE Performance Criteria: Implications for Improving Hydrological Modelling. *J. Hydrol.* **2009**, *377*, 80–91. [CrossRef]

- Mass, C.F.; Ovens, D.; Westrick, K.; Colle, B.A. Does Increasing Horizontal Resolution Produce More Skillful Forecasts? The Results of Two Years of Real-Time Numerical Weather Prediction over the Pacific Northwest. *Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc.* **2002**, *83*, 407–430.

- Jiménez, P.; Dudhia, J. Improving the Representation of Resolved and Unresolved Topographic Effects on Surface Wind in the WRF Model. *J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). *Reviews of Geophysics* **2007**, *45*(2), RG2004. [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Verdin, K.; Jarvis, A. New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. *Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union* **2008**, *89*(10), 93–94. [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, C.F.; Jones, R.G.; Lee, R.W.; Rowell, D.P. *Selecting CMIP5 GCMs for Downscaling over Multiple Regions*; *Climate Dynamics* **2015**, *44*(11), 3237–3260. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, L.L.; Van Heerden, J.; Sumner, P.D. *A Baseline Climatology of Sounding-Derived Parameters Associated with Heavy Rainfall over Gauteng, South Africa*; *International Journal of Climatology* **2015**, *35*(7), 1162–1174. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Van Schalkwyk, L.; Blamey, R.C.; Dyson, L.L.; Reason, C.J.C. *A Climatology of Drylines in the Interior of Subtropical Southern Africa*; *Journal of Climate* **2022**, *35*(19), 6411–6430. [CrossRef]

- Blamey, R.C.; Reason, C.J.C. *Mesoscale Convective Complexes over Southern Africa*; *Journal of Climate* **2012**, *25*(2), 753–766. [CrossRef]

- Dedekind, Z.; Engelbrecht, F.A.; Van der Merwe, J. *Model Simulations of Rainfall over Southern Africa and Its Eastern Escarpment*; *Water SA* **2016**, *42*(1), 129–143. [CrossRef]

- Crétat, J.; Pohl, B.; Richard, Y.; Drobinski, P. Uncertainties in simulating regional climate of Southern Africa: Sensitivity to physical parameterizations using WRF. *Clim. Dyn.* **2012**, *38*(3), 613–634. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, F.A.; McGregor, J.L.; Engelbrecht, C.J. Dynamics of the Conformal-Cubic Atmospheric Model projected climate-change signal over southern Africa. *Int. J. Climatol.* **2009**, *29*(7), 1013–1033. [CrossRef]

| Station Name | Lat | Lon | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mahalapye Meteorological Station | S | E | 1017 |

| Mookane Primary School | S | E | 951 |

| Tirelo Primary School | S | E | 957 |

| Kalamare Primary School | S | E | 1074 |

| Machaneng Police | S | E | 888 |

| Pallaroad Kgotla | S | E | 1002 |

| Model Options | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Model type | Non-hydrostatic |

| Domains | two (2) (with a two-way nested domains) |

| Grid resolution (spacing) | parent domain 1: 9 km × 9 km; (312 × 301 grid) |

| nested domain 2: 3 km × 3 km; (403 × 412 grid) | |

| Map projection | Mercator |

| Initial conditions | NCEP GFS (3 hourly interval) |

| PBL Schemes | YSU scheme |

| Cumulus schemes | A newer Tiedtke scheme |

| Microphysics schemes | WSM 6-class graupel scheme |

| Shortwave radiation scheme | RRTMG scheme |

| Longwave radiation scheme | RRTMG scheme |

| Land surface model | Unified Noah land surface model |

| Scheme | Description |

|---|---|

| RRTM | Rapid Radiative Transfer Model used to improve radiative transfer |

| calculations during the WRF run; developed by [44]. | |

| YSU | Yonsei University planetary boundary layer scheme introduced by |

| [45]; represents boundary layer processes. | |

| Noah LSM | Unified Noah land surface model used to capture land surface |

| interactions; developed by [46]. | |

| New Tiedtke | Updated cumulus scheme by [47]; used in |

| cumulus convection representation. | |

| WSM6 | Weather Research and Forecasting Single-Moment 6-class |

| microphysics scheme developed by [45]; | |

| provides detailed microphysical processes. |

| Model | RMSE (mm) | PBIAS (%) | KGE | r | POD (1 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRF_3km | 43.529 | -56.10 | -0.356 | -0.038 | 1.000 |

| WRF_9km | 41.197 | -48.22 | -0.225 | 0.020 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).