1. Introduction

Wetlands provide numerous ecosystem services, many modulated by aquatic plants [

1,

2,

3]. They serve as water reservoirs, buffering floods and droughts and provide habitat for many species, especially breeding areas for migratory birds [

4]. The Cruces River Wetland is part of the “Carlos Anwandter” Ramsar site in southern Chile. This wetland has tidal influence and is within Valdivia’s river estuarine system, of which the Cruces and Calle-Calle rivers are the main tributaries. This area presents a high diversity of birds and aquatic plants, and it is a crucial breeding area for the black-necked swan (

Cygnus melancoryphus) and other birds due to the high abundance of the Brazilian waterweed -

Egeria densa- [

5,

6], which is the main food supply for this swan [

7].

In 2004, a significant reduction in the abundance of

E. densa in the Cruces River Wetland was observed due to industrial pollution, which resulted in a decrease in the abundance of the

Cygnus melancoryphus and other aquatic birds in this area due to mortality and emigration, which consequently produced a considerable decrease in nests and offspring [

5,

8,

9]. Subsequent studies showed that stems and leaves of the

E. densa collected in the wetland presented a dark coloration due to apparent necrotic tissue which is characteristic of plants exposed to high levels of iron [

10]. Plants also presented a sediment crust adhered to the surface, which may hinder the absorption of sunlight and, consequently, their photosynthetic capacity [

11]. Iron analysis in samples of

E. densa during 2004 presented concentrations twice as high as in samples of the same plant outside the sanctuary [

12]. In addition, liver samples of

Cygnus melancoryphus presented specific staining for iron. They showed signs of malnutrition [

13,

14] with iron concentrations that were at least three times higher than in liver samples of swans from other regions [

12,

14]. Consequently, herbivorous birds (i.e.

, swans, coots, and ducks) migrated due to food scarcity in this area. Specimens that could not migrate died due to histopathological alterations possibly from iron and other trace metals poisoning after feeding on

E. densa with high amount of sediments deposited on them [

5]. A report concluded that the high concentrations of iron and other toxic elements in the aquatic plants were related to a decrease in the water quality of the Cruces River [

15] caused by the opening of a pulp mill factory positioned 25 km upstream from the sanctuary in February 2004. Among the changes in water quality, an increase in sulphate and aluminium concentration was observed which is coincident with the chemicals used as coagulating agents for the treatment of wastewaters generated by the pulp mill, causing precipitation of various soluble metals and subsequent deposition on the surface of the aquatic plants [

15]. Recent studies have demonstrated that several physiological parameters on black necked swans did not return to levels observed previous to the 2004 pollution episode [

16].

Iron is an important trace element in most known life forms and in vertebrates. It is considered essential in vertebrates since it acts as an oxygen transporter via haemoglobin in the blood [

17]. This process controls the absorption and accumulation of iron in the organisms, maintaining a delicate balance between absorbed and stored iron [

18]. On the other hand, the processes of iron excretion also have some limitations; consequently it is essential to maintain iron homeostasis, as an excess in the body of some organisms also results in serious physiological disorders [

19]. Zinc is a relevant element of wetland biota physiology [

20,

21] and can interact with iron, modulating its absorption [

22]. In high levels, Zn can be toxic to wetlands biota [

23,

24,

25,

26].

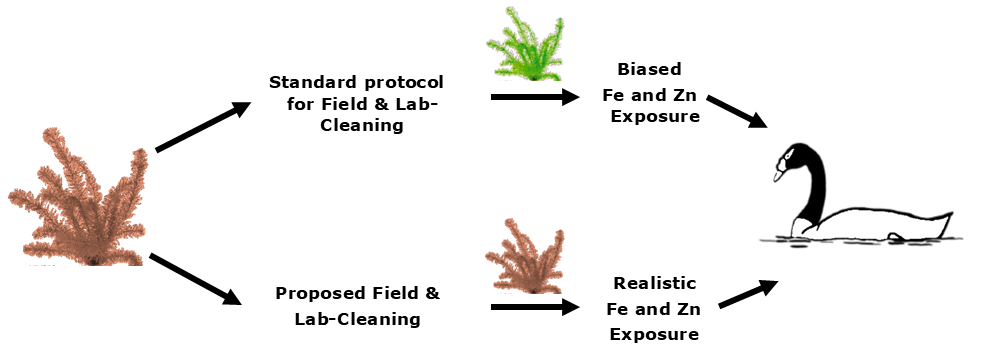

There is a gap regarding standard methodologies during sample collection and preparation for metal quantification in aquatic plants. Different sample treatment and sub-sampling procedures can reduce representativeness and reproducibility leading to different conclusions regarding the level of contamination and the potential impacts on herbivore species. Some standard protocols for metal analysis in agricultural plant material encourage eliminating any residual particulate matter on the plant’s surface, since the target is to quantify a specific analyte within the plant tissue [

27]. However, this methodology neglects the contribution of particulate contaminants deposited on the plant’s surface that are ingested by herbivores. Accordingly, a comprehensive understanding of the potential variability due to sampling, sample processing, and analysis is crucial to understand the influence of deposited particles on reported metal concentrations in aquatic plants. Therefore, correctly quantifying metal concentration in aquatic plants is essential to understand metal exposure and potential ecotoxicological effects on wetland herbivorous.

This research aims to compare the effects on the quantification of Fe and Zn in E. densa of different sample treatments and section subsampling, to assess their spatial-temporal distribution and to evaluate the potential impacts on waterbird’s herbivory.

2. Materials and Methods

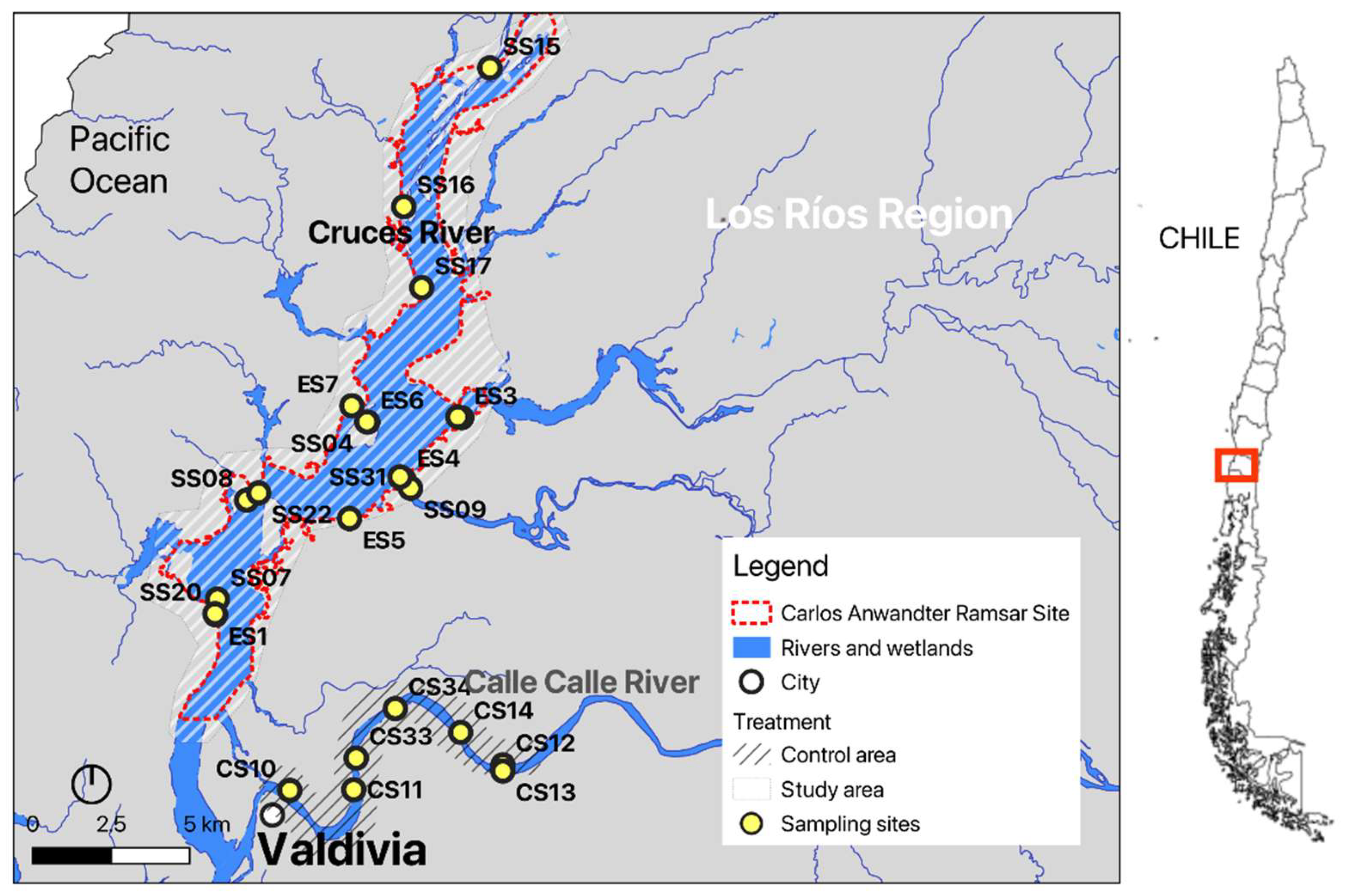

2.1. Sampling Site and Sampling Strategy

Samples were collected at two sites: 1) the study site, which corresponds to the Carlos Anwandter Ramsar site within the river Cruces catchment, and 2) the control site, located in the Calle-Calle River (

Figure 1). Eight sampling campaigns were undertaken from May 2022 to April 2024 (see sample information in

Table S1). The first three were performed to evaluate the effects of sampling strategies, sub-sampling and sample treatment methodologies on the quantification of Fe and Zn. After defining the methodology, the remaining campaigns were carried out to evaluate the concentrations of Fe and Zn in

E. densa in the study and control sites. Plant material was collected using an outboard motorboat equipped with an articulated anchor and a hook. The sampling procedure was performed in shallow waters (up to 3 m depth) using the boat’s anchor and hook to carefully extract the plants minimising sediment resuspension. Basic water parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen and electric conductivity were measured in each sampling location using a Hanna multiparametric probe (HI98199).

2.2. Sample Type Selection and Pre-Treatment

The collected E. densa was immersed three times in the river water to remove any potential loose sediment excess due to the sampling procedure. Sub-samples were taken by hand, separating green sections of the plants without evidence of sediment deposition on the surface, and abnormal dark coloured sections with sometimes evident sediment crusts. Roots and other minor aquatic plants were discarded and only leaves and stems were analysed. The sub-samples were placed in clean polyethylene bags, labelled accordingly, and transported to the laboratory. Once in the lab, the samples were stored in a fridge at 4 °C before treatment and analysis.

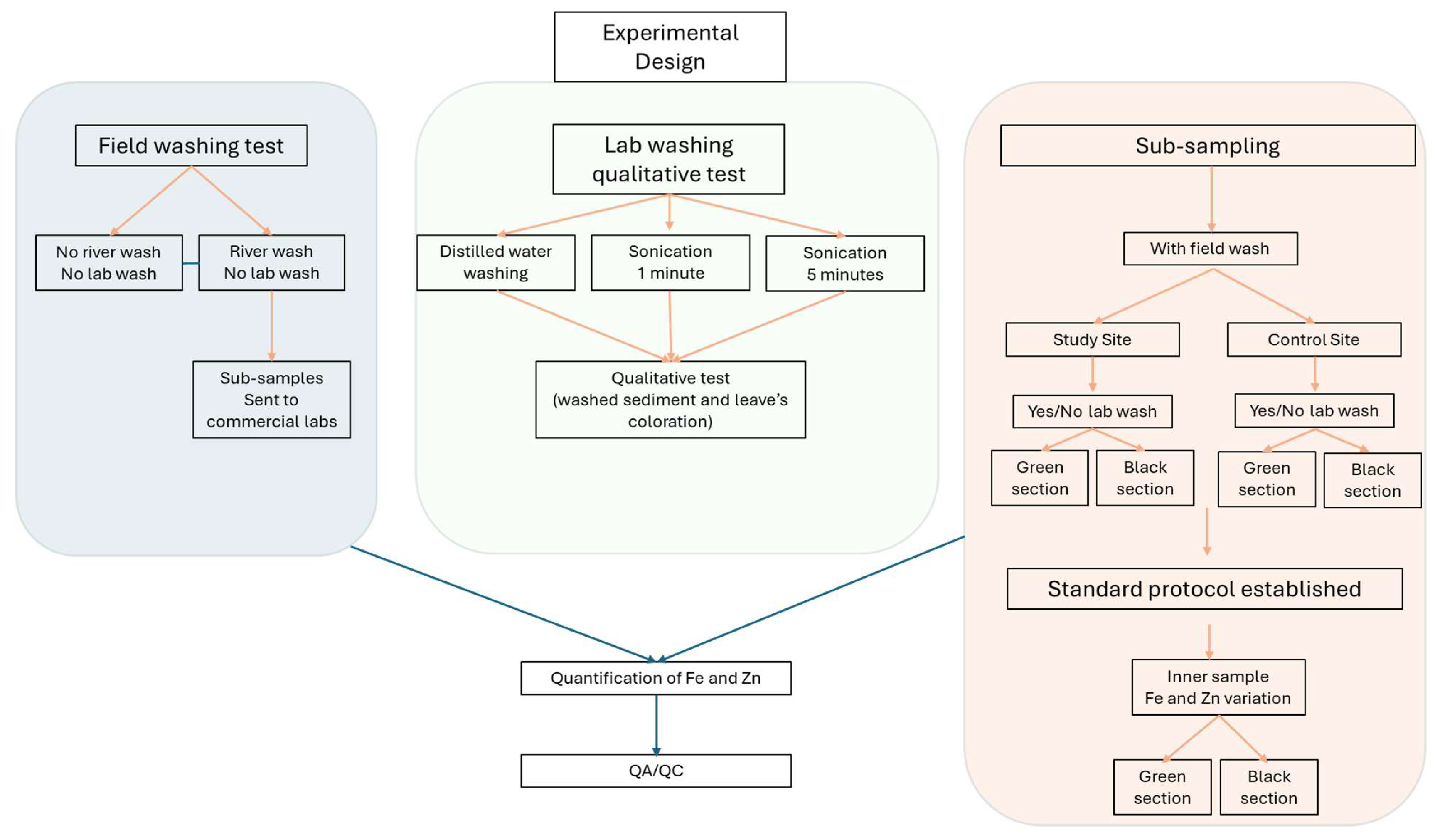

The experimental design to test the effect of sample treatment on the Fe and Zn concentrations is summarised in

Figure 2. In brief, a preliminary experiment was performed to examine the effect of a field washing with river water on the concentrations of Fe and Zn. For this purpose, two sample pre-treatments were evaluated: 1) samples without a field washing step (

n = 19) and 2) samples with an in situ field washing (

n = 13). When testing the field washing, green and black sections of the same sample of

E. densa (

n

15) were sent to two independent laboratories for Fe and Zn analysis. Samples were processed using the protocols established by the National Accreditation Commission (CNA) – SCHCS for laboratory 1 and the AOAC 985.35 ed 2012, S. methods 3030 C, E and S. Methods 3120 of 2005 for laboratory 2.

A third set of samples were tested for a laboratory pre-treatment. Here, three cleaning procedures were tested: 1) gentle rinsing with distilled water using a washing bottle, and 2) sonication in distilled water for 1 min and 3) sonication in distilled water for 5 min. The plant material and the resulting washing waters were visually inspected for colour and apparent water turbidity. After defining a suitable lab pre-treatment, a further experiment was performed to investigate the effect of laboratory washing on the type of leaf. In this case, plants from both sampling sites (control and study) were classified as “Green, G” with no evidence of sediment deposition or damaged tissue, and “Black, B” with evident sediment deposition and black coloration.

2.3. Sample Analysis

2.3.1. Microscopic Analysis

An optical microscope was used to evaluate morphological aspects of the different parts of the aquatic plant E. densa (in the study and control sites). Also, a scanning electron microscopy (EVO MA10 -Variable Pressure Scanning Electron Microscope Zeiss®) was employed. Complementary, a Scanning Electron Microscope coupled to an electron dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector (Oxford X-ACT) was used to estimate the relative abundances of some elements within different parts of the aquatic plant.

2.3.2. Determination of Fe and Zn Content

All labware employed during leaching, filtration, and analysis were placed in an acid bath (HNO3 10%) for 24 h, rinsed thoroughly with ultrapure water (Milli-Q) and dried. The samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 h, grinded using a mortar and pestle, placed in plastic bags, and stored in a desiccator. Subsamples of about 0.5 g were weighed into Teflon beakers. The process was repeated to prepare at least three replicates per sample. Then, 7 mL of HNO3 65% and 1 mL of H2O2 30% (for analysis, EMSURE®) were added to each sample and placed into a microwave digestion system (Milestone START-D) as follows: heating ramp to 220 °C and maintained for 20 minutes and left to cool to room temperature for 1 h. The digests were quantitatively transferred to 10 mL volumetric flasks and made up to the mark with ultrapure water (Milli-Q). The samples were then filtered and transferred to clean 50 mL HDPE bottles before analysis.

The samples were analysed for Fe and Zn content using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific iCE 3000 series) operated with an air/acetylene gas mixture. Fe and Zn were analysed at the 248.3 and 213.9 nm absorption lines, respectively. Calibration curves were prepared from a certified standard solution (Titrisol

® 1,000 mg L

-1) in the range from 0.3 to 10 mg L

-1 for Fe and from 0.1 to 1.5 mg L

-1 for Zn. Calibration checks were run before every analysis batch using a certified reference material (CRM) of wastewater (EnviroMAT QX102848, SCP Science). Method blanks were prepared in the same fashion as the samples and method performance was evaluated using the EnviroMAT SS-2, SCP Science, contaminated soil, CRM (n = 4) with recovery percentages of 96% and 87%, and a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 2.0% and 5.5% for Fe and Zn, respectively. Both CRMs provided ranges for confidence and tolerance intervals that were used to inform the instrument and method performances (

Table S2). Additionally, triplicates were run every 10 samples to assess method repeatability (% RSD = 0.5 – 13.2% for Fe and 0.1 – 8.3% for Zn), and a standard of known concentration was used to check instrument stability (% RSD = 0.1 – 1.8% for Fe and 0.2 – 2.7% for Zn).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The sample pre-treatments and the plant sections were compared statistically to assess the effects of river and lab washing and the difference between green and black sections, respectively. For this purpose, the grouped data by sample pre-treatment and plant sections were tested for normality and homoscedasticity. Depending on the outcome, a two-sample t-test or a Wilcoxon (Mann-Whitney U-test) was performed. The significance level was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison Between Commercial Laboratory Analyses

The first samples collected were sent to two independent laboratories to assess the concentration of Fe and Zn in the samples. However, Fe and Zn concentrations from the same section of the plant presented significant differences for both elements (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.001), showing relative differences ranging from 134 to 3,190% and 540 to 2,700% for Fe and Zn respectively (

Figure S1 and

Table S3). These results highlighted that the lack of an established protocol for sample treatment in aquatic plants may lead to completely different results for the same sample. Laboratory 1 performed a gentle wash with distilled water, and laboratory 2 did not wash the samples prior to analysis. Nonetheless, the results obtained by the laboratory that performed the sample wash were significantly higher than the one that did not wash the samples. Consequently, reported differences may be attributed to other factors.

3.2. Field Washing Experiments

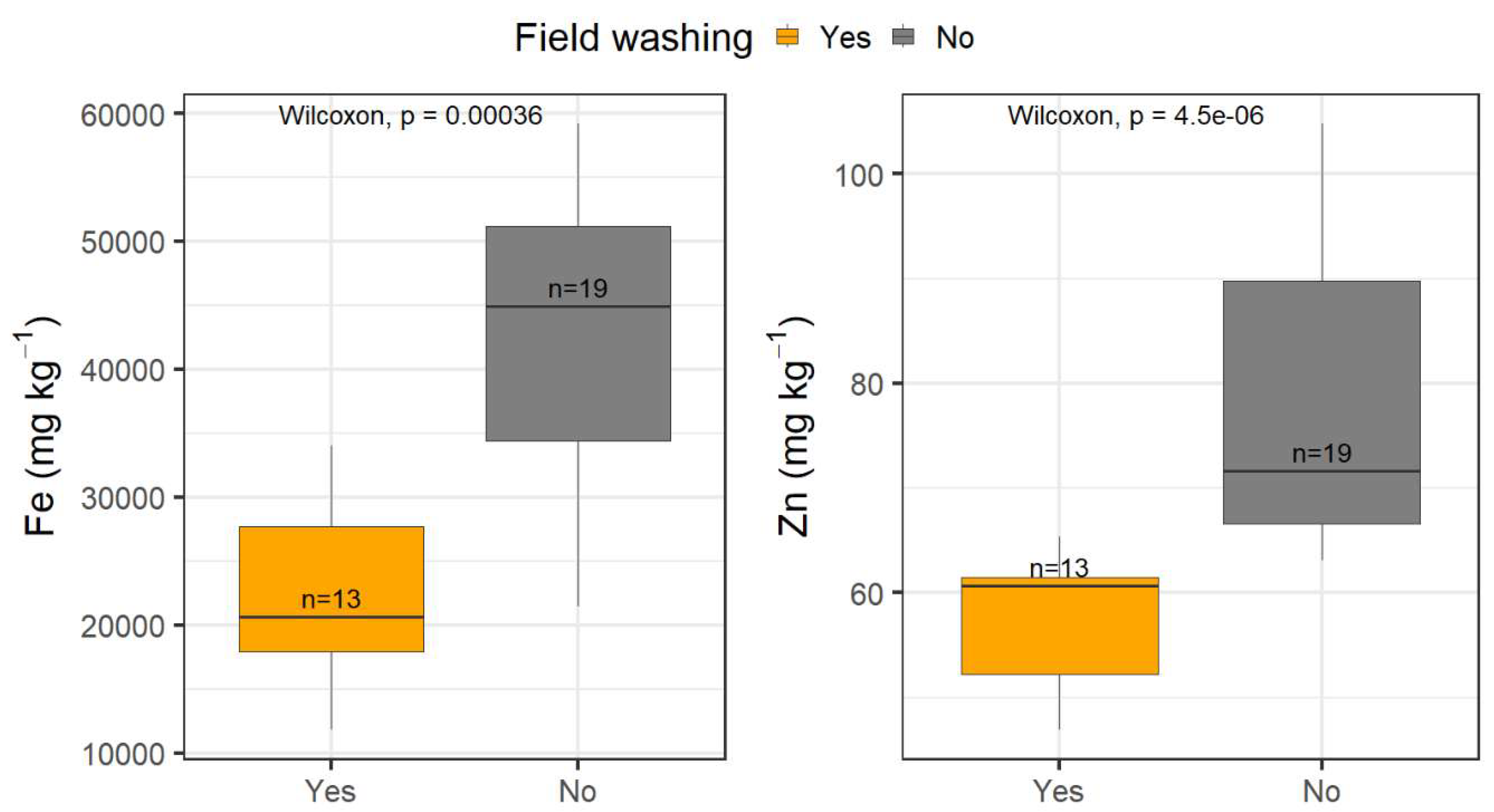

The field-washing procedure significantly affected the quantified metals (

Figure 3 and

Table S4). For example, Fe concentrations averaged 42,501 ± 13,186 mg kg

-1 in the samples that were not washed in the field, while the samples that were washed in the river averaged 22,202 ± 7,311 mg kg

-1, which was two times lower. The Fe concentration distributions between these two groups differed significantly (U-test, p = 3.59×10

-4). On the other hand, Zn concentrations averaged 78.4 ± 15.4 mg kg

-1 in the samples that were not subjected to washing compared to the ones washed in the field, which averaged 57.7 ± 6.1 mg kg

-1, a ~1.5-fold decrease. Zn concentrations between these two treatments were also significantly different (U-test, p = 4.51×10

-6). These results highlighted that rinsing the sample in the field during sample collection is an important aspect to be considered. Neglecting this step can result in significantly higher concentrations in the analysed material.

The distilled water washing step is the common procedure before the quantification of metals in aquatic plants [

8,

12]. A qualitative test was performed on the samples to investigate the potential effects of distilled water washing. This test showed that sonication effectively eliminated the sediment adhered on the plant’s surface (

Figure S2). However, the experiment also showed that after 1 and 5 min of sonication, the plants were not only free of recently deposited sediment during sampling but also from the older sediment crust (

Figure S2b and c). Complete cleaning of

E. densa, therefore, is not representative of the environmental conditions at which this food source is available to the swans and other herbivores.

3.3. Laboratory Washing Experiments

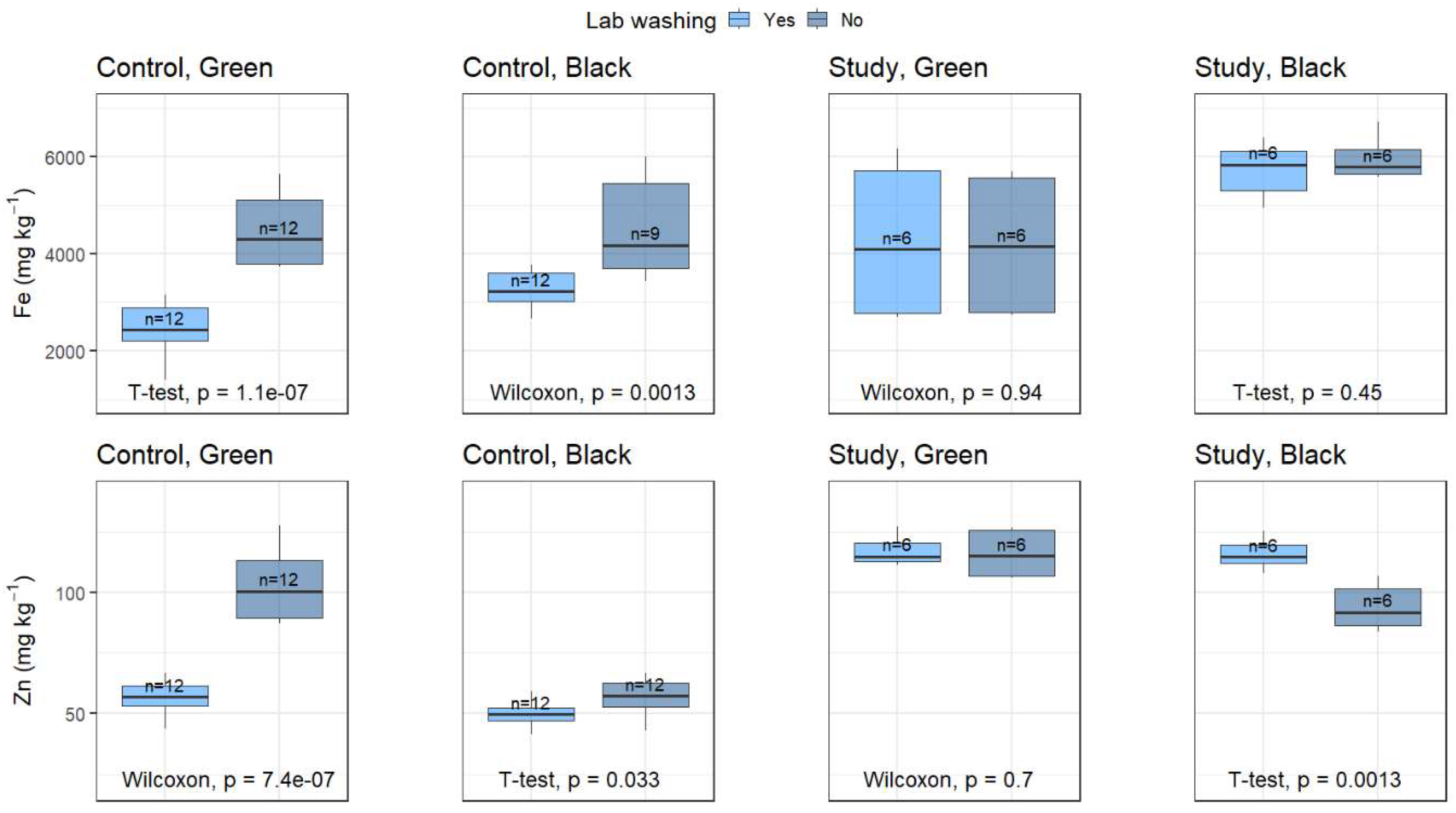

The laboratory washing procedure was assessed in samples previously washed in the field. Fe and Zn were quantified in samples that were washed and not washed in the laboratory from both the control and study sites (

Figure 4 and

Table S5). Fe concentrations in the control site significantly differed between the washed and non-washed samples, regardless of the plant section (t-test, p = 1.1 × 10

-7 and Wilcoxon test, p = 0.0013, respectively). However, in the study site, there were no statistically significant differences between both treatments (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.94; and t-test, p = 0.45 for the green and black sections, respectively). The difference might be attributed to the fact that the samples collected in the control site did not show significant amount of fine sediment deposited, and if it were, the washing process might have eliminated most of it. On the contrary, in the study site, the plants have been exposed to significant sediment deposition, and the crusts were firmly adhered to the leaves not removed during the field and laboratory wash.

Zinc concentrations for lab-washed and non-washed samples in the green and black sections in the control site were significantly different (Wilcoxon, p = 7.4×10

-7 and t-test, p = 0.033, respectively,

Figure 4). In addition, washing treatment in the green sections of the plant was not significantly different in the study site (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.7). In contrast, the black sections showed significant differences (t-test, p = 0.0013). Zn concentrations followed similar trends as Fe for the green and black sections in the control site. However, in the study site, no clear trend is observed.

The laboratory washing procedure with distilled water significantly influenced the metal quantification, particularly for the control site. In an area that might be more influenced by fine sediment pollution, such as the study site, the difference might not be as significant due to sediment incrustation into the plant tissue. Consequently, the laboratory washing step should be carefully considered before carrying out an environmental impact assessment of metals on submerged aquatic plants.

3.4. Microscopic and Spectroscopic Analysis

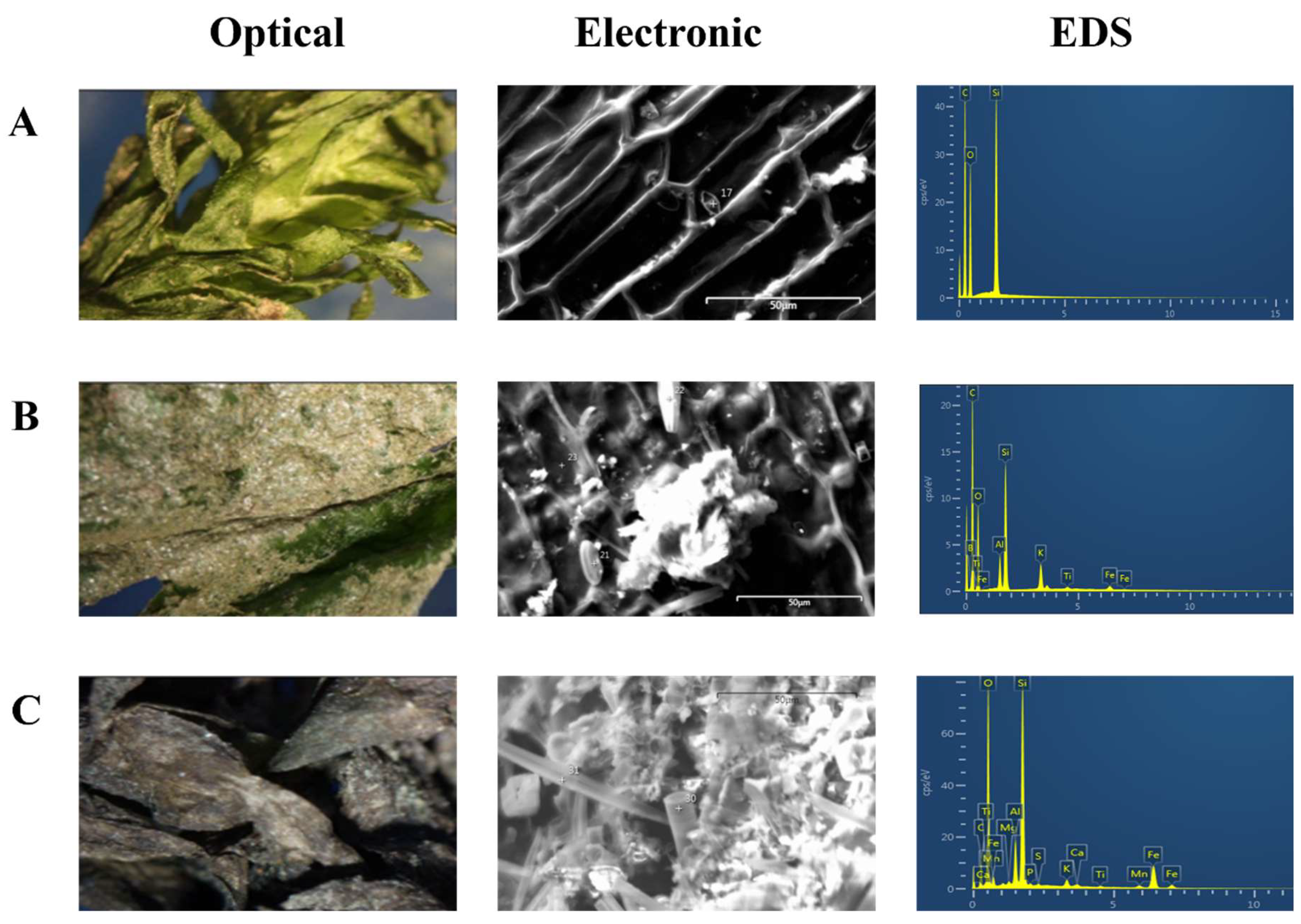

Microscopy (optical and electronic) and EDS analysis (see

Figure 5) indicated that healthy plants presented the typical green colour with silicon as the most abundant element. Fractions of the plants with sediment presented more relative abundance of elements such as Al, Ti, Fe, among others. Finally, the black sections with sediment crusts showed much and more abundant elements.

3.5. Fe and Zn Content in Green and Black Sections of the Plant

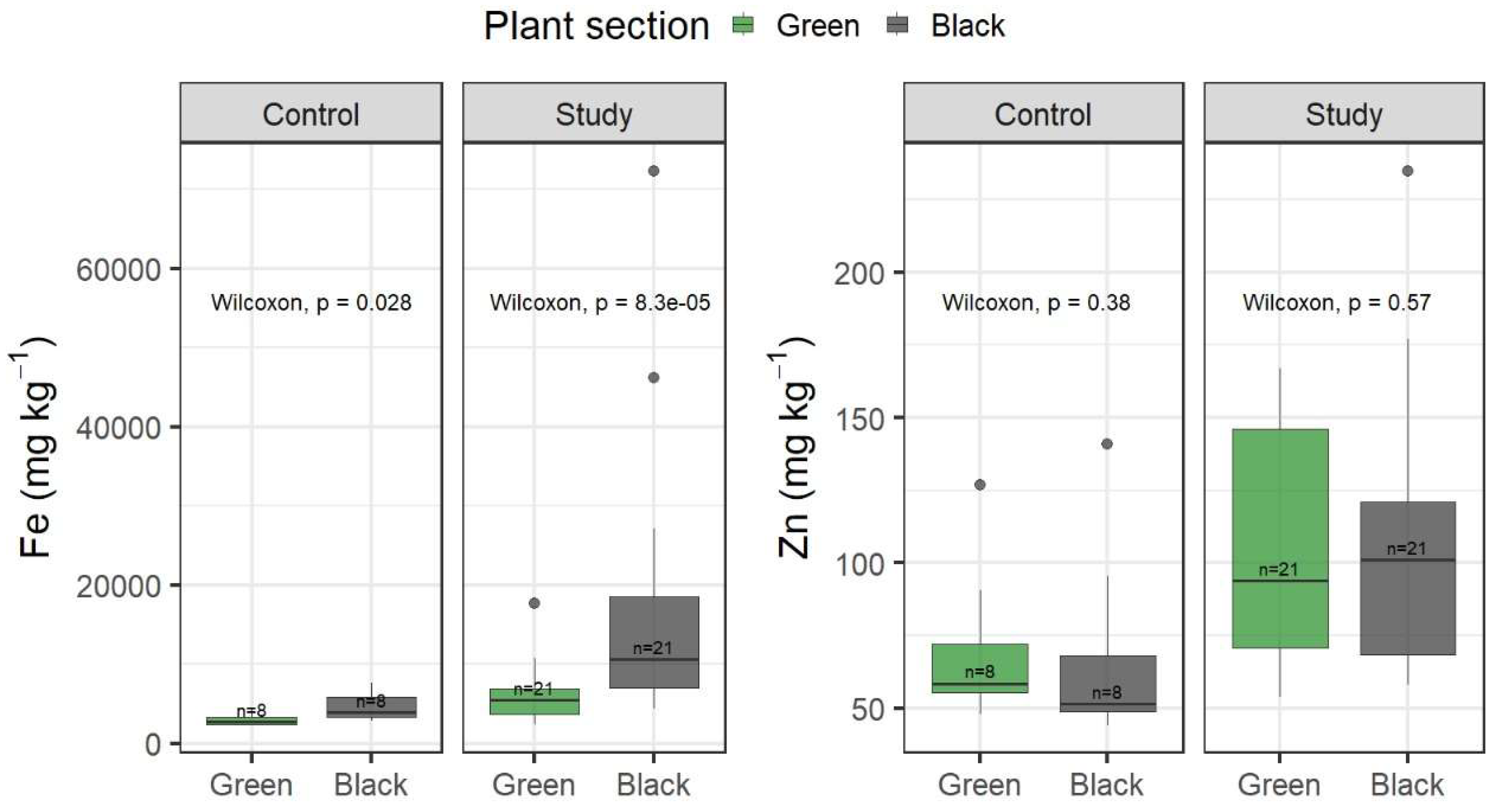

The concentration of Fe in both green and black sections of the plant (

Figure 6) showed significant differences in the control and in the study sites (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.028; and Wilcoxon test, p = 8.3×10

-5, for the control and study sites, respectively). Zn concentrations in both green and black sections of the plants in both sites were not significantly different (Wilcoxon test p = 0.38 and p = 0.57 for control and study sites, respectively). This suggests that the subsampling procedure might influence reported Fe concentrations. In addition, Fe concentrations varied from 57% to 95% in the study site and from 25% to 41% for the control site. Zinc, on the other hand, presented lower variation (from 37 to 42% and 38 to 50% for the study and control sites, respectively). High variability in reported Fe and Zn concentrations might be associated with different riverine dynamics influencing particle deposition e.g., meandering versus straight channel areas. Nevertheless, the presence of outliers might have influenced these values.

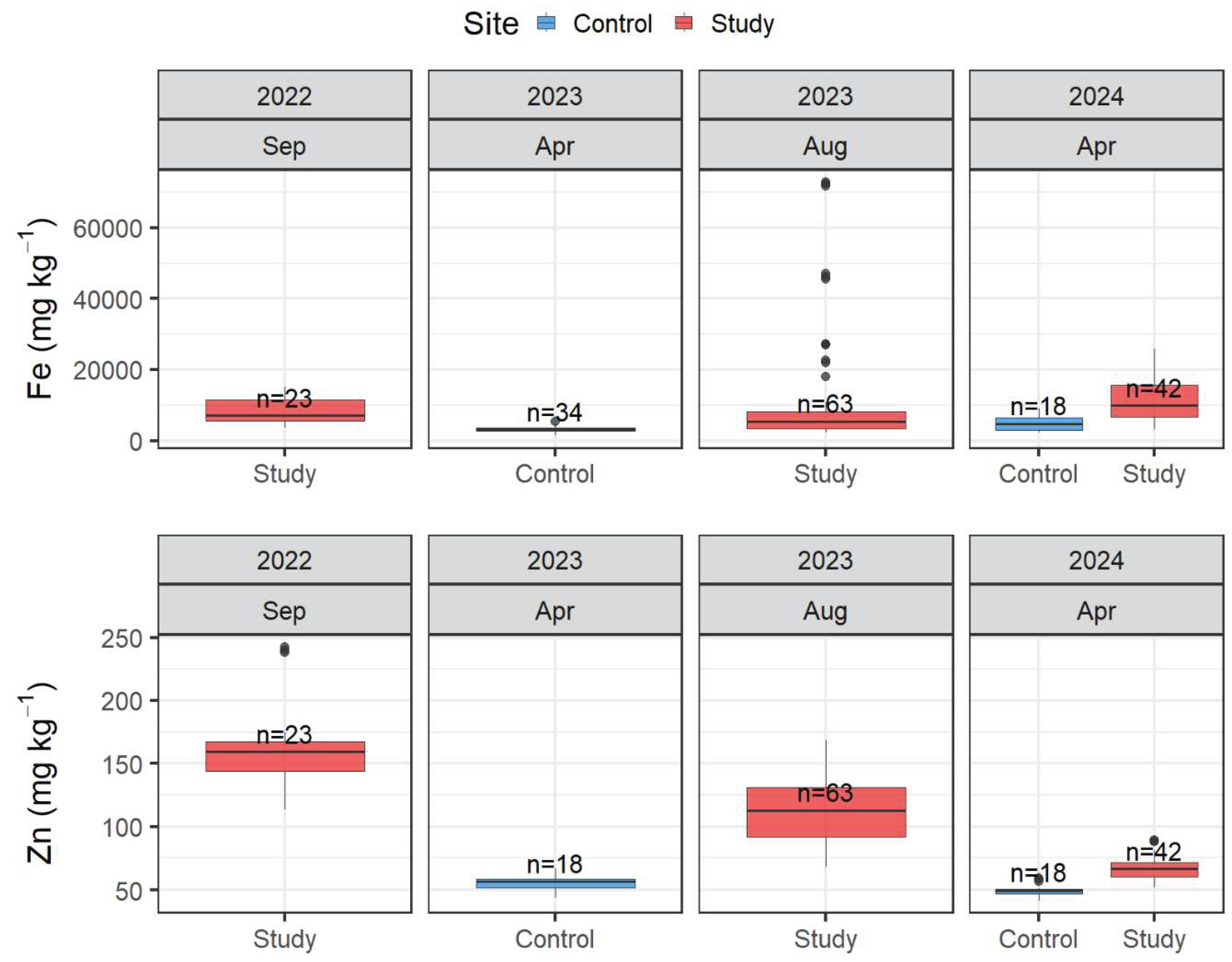

3.6. Temporal Trends of Fe and Zn in Egeria densa

Iron concentrations in the study site were notably higher than the control site (see

Figure 6). Concentrations of this metal averaged 11,155 mg kg

-1 in the study site while an average concentration of 3,783 mg kg

-1 at the control site, a 3-fold increase, was found. In a study carried out in the sanctuary in 2004, damaged plants averaged 40,090 mg kg

-1 of Fe compared to 13,251 mg kg

-1 in healthy plants [

12]. Another study presented average values during 2004-2005 of 31,000 mg kg

-1 in the sanctuary and 9,800 mg kg

-1 for a control site outside the sanctuary [

28]. Our average Fe concentrations in the study site were comparable to those reported from non-damaged tissue and for the control site in the previous studies. However, the difference can be attributed to the sample treatment as no full details regarding river and/or lab prewashing are reported. Only gently rinsing with distilled water is mentioned in these studies. Furthermore, frequent wastewater releases to the river from the upstream paper mill company in the past can be an additional factor. Values without washing (river and/or lab washing) may increase iron concentrations to approximately 42,000 mg kg

-1 which is similar to those reported for damaged tissue in the Cruces River. Nevertheless, and as stated above, the decrease in Fe concentrations may also be associated with a reduced input from the pollution sources, as the incident in 2004 was apparently more detrimental than those reported in 2014 and 2020.

Figure 6.

Concentrations of Fe and Zn for all E. densa samples.

Figure 6.

Concentrations of Fe and Zn for all E. densa samples.

The same is true for Zn (see

Figure 6) where concentrations averaged 60 mg kg

-1 in the control site whereas study site concentrations averaged 108 mg kg

-1, almost twice the average concentration in the control site. Another study in 2004 presented average concentrations of Zn in the Cruces River of 66.3 mg kg

-1[

12], again very similar to those reported in the control site.

On the other hand, Fe concentrations for all samples (

Figure 6) did not show consistent trends although they showed significant differences across years for both the study and control sites (Kruskal-Wallis test, p-value = 0.0008953; and Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value = 0.005002 for the study and control sites, respectively). Zinc concentrations in the study showed a consistent and significant decrease over the years for both the study and control sites (Kruskal-Wallis test, p-value < 2.2×10

-16; and Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value = 0.004173 for the control and study sites, respectively). These trends suggest that the plant assimilates these two elements differently. Iron appears to be consistently adsorbed by the plant, forming crusts that remain for a long time [

10], whereas zinc is apparently directly incorporated and is not related to external accumulation as Fe.

Several hypothesis has been discussed to account for the source of increase particulate matter on the aquatic plants: 1) changes in Fe concentrations in the study site can be attributed to drastic changes in water pH as a result of upstream industrial discharges [

29]. Unpublished results have demonstrated that the release of “green liquor” (a strongly alkaline solution mainly comprised of sodium hydroxide and sodium sulphide) can turn river water highly alkaline for a short period of time promoting iron oxides precipitation [

30]; 2) increased fine sediment delivery to the wetland due to increasing forestry activities in the surrounding area [

31]; and 3) natural factors such as saline intrusion from the sea [

32] leaving more shallow waters thereby increasing turbidity [

33]. The fact that aquatic plants from the Cruces River were more affected by iron deposition with visible tissue damage and sediment crusts supports the first.

3.7. Implication on Herbivory and Metal Exposure

E. densa has been reported as a virtuous natural sediment trap, and in an environment where sediments are almost saturated, iron and other metals become more available to the plant [

10]. It has been reported that macrophytes naturally create iron crusts and affecting plant physiology, and in some cases, showing evident problems such as plant growth, leaf mortality, and necrotic leaves [

10,

12,

34].

E. densa has a key role of aquatic submerged plants in wetland ecosystems providing food, shelter, and habitat for fish and macroinvertebrates [

35,

36], and has been identified as the primary, and virtually only, food source for the Black-necked swan [

7], the most abundant waterfowl in the Cruces River and the reason this site was declared a RAMSAR wetland of international importance. Thus, understanding the complexity of metal deposition is crucial to assess the concentration of metal exposure for herbivores. Moreover, the impact of the metal deposition on the

E. densa physiology may cause important changes on this large estuarine wetland due to the ecosystemic role of this aquatic plant as food, shelter, carbon storage and sediment trapping [

37]. Despite Fe concentrations being lower than those reported in 2004, the Fe input is still significant affecting

E. densa and, subsequently, birds that fed on them.

3.8. Methodological Recommendations for Future Studies

To better assess the field concentrations that accurately represent metal exposure to herbivorous wetland biota, future studies should consider the following procedures when assessing concentrations of metals in aquatic plants:

Use sampling devices/methods that avoid bottom sediment to be added during the macrophyte extraction.

Thoroughly clean the aquatic plants in the field with water from the wetland under research (i.e., river/lake) before subsampling.

Plant section selection should address the sample heterogeneity by collecting representative sections of healthy and non-healthy plants.

Once in the laboratory, pursuing the objective of getting an accurate representation of metal exposure to herbivores, using a gentle wash with distilled water or, preferentially, Milli-Q water to eliminate the excess of loose sediment but not those that might be available for herbivores.

Sample collection from different areas should also be considered to account for spatial variability.

Follow strict quality assurance and quality control procedures.

4. Conclusions

This study aimed to compare different sample treatments and plant section subsampling of E. densa to assess their effects on the quantification of Fe and Zn. For this purpose, sample treatments were compared, and samples analysed for Fe and Zn concentrations. Results indicated that washing the samples in the field and in the laboratory significantly reduced Fe and Zn concentrations. These findings highlighted the importance of establishing standard methodologies for sample treatment in aquatic plants metal analysis. The same is true when sampling different sections of the plant, particularly for samples collected in areas under anthropogenic stress. The plant section sampling and the further washing procedures directly impacted metal pollution assessment, particularly the accuracy of estimating metal exposure concentration to herbivorous wetland biota.

Our data demonstrated that the deposition of metals, particularly Fe, can significantly influence both the determination of the metal concentration and the exposure to the wetland’s herbivores. For instance, to better determine a realistic exposure concentration for black-necked swans and any other herbivore that feeds on E. densa, researchers must pay attention to field sampling and laboratory procedures (i.e., washing methodologies) to better understand realistic metal concentrations and animal exposures. Future studies should therefore consider the implications demonstrated in this study allowing unbiassed comparison between studies and better assessment of aquatic plant pollution and subsequent consequences to herbivores. Finally, Despite Fe concentrations being lower than those reported in 2004, the Fe input is still significant affecting E. densa and, subsequently, birds that fed on them.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Claudio Bravo-Linares: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing-original draft; Writing-review & editing. Esteban Delgado: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software. Marcela Cañoles-Zambrano: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software. Enrique Muñoz-Arcos: Data curation; Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. Jorge A. Tomasevic.: Investigation, Methodology, Sampling, Data collection, Field Work, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing-review & editing. Alexander Neaman: Writing-review & editing. Ignacio Rodriguez-Jorquera: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Sampling; Data collection, Field Work, Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Writing-review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

this research was funded by the Chilean Government via ANID Fondecyt Project ID 11221213.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Chilean Government via ANID Fondecyt Project ID 11221213. The authors are also grateful for the support during sampling to CONAF Region de Los Ríos and its park rangers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mitsch, W.J.; Bernal, B.; Nahlik, A.M.; Mander, Ü.; Zhang, L.; Anderson, C.J.; Jørgensen, S.E.; Brix, H. Wetlands, Carbon, and Climate Change. Landscape Ecol 2013, 28, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneepeerakul, C.P.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F.; Tamea, S.; Rinaldo, A.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Coupled Hydrologic and Vegetation Dynamics in Wetland Ecosystems. Water Resources Research 2008, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieles, D.J. Vegetation Development in Created, Restored, and Enhanced Mitigation Wetland Banks of the United States. Wetlands 2005, 25, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, S.; Almuktar, S.A.A.A.N.; Scholz, M. Impact of Climate Change on Wetland Ecosystems: A Critical Review of Experimental Wetlands. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 286, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, E.; Vollman, R.S.; Contreras, H.C.; Valenzuela, C.D.; Suarez, N.L.; Herbach, E.P.; Huepe, J.U.; Jaramillo, G.V.; Leischner, B.P.; Riveros, R.S. Emigration and Mortality of Black-Necked Swans (Cygnus Melancoryphus) and Disappearance of the Macrophyte Egeria Densa in a Ramsar Wetland Site of Southern Chile. ambi 2007, 36, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, C.; Jaramillo, E.; Camus, P.; Labra, F.; Martín, C.S. Dietary Habits of the Black-Necked Swan Cygnus Melancoryphus (Birds: Anatidae) and Variability of the Aquatic Macrophyte Cover in the Río Cruces Wetland, Southern Chile. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0226331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, P.; Schlatter, R. Feeding Ecology of the Black-Necked Swan Cygnus Melancoryphus in Two Wetlands of Southern Chile. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 2002, 37, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopetegui, E.J.; Vollman, R.S.; Contreras, H.C.; Valenzuela, C.D.; Suarez, N.L.; Herbach, E.P.; Huepe, J.U.; Jaramillo, G.V.; Leischner, B.P.; Riveros, R.S. Emigration and Mortality of Black-Necked Swans (Cygnus Melancoryphus) and Disappearance of the Macrophyte Egeria Densa in a Ramsar Wetland Site of Southern Chile. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 2007, 36, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, V.H.; Tironi, A.; Delgado, L.E.; Contreras, M.; Novoa, F.; Torres-Gómez, M.; Garreaud, R.; Vila, I.; Serey, I. On the Sudden Disappearance of Egeria Densa from a Ramsar Wetland Site of Southern Chile: A Climatic Event Trigger Model. Ecological Modelling 2009, 220, 1752–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarrow, M.; Marin, V.H.; Finlayson, C.; Tironi, A.; Delgado, L.E.; Fischer, F. The Ecology of Egeria Densa Planchon (Liliopsida: Alismatales): A Wetland Ecosystem Engineer? Revista chilena de historia natural 2009, 82, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand-Jensen, K.A.J. Environmental Variables and Their Effect on Photosynthesis of Aquatic Plant Communities. Aquatic Botany 1989, 34, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinochet, D.; Ramírez, C.; MacDonald, R.; Riedel, L. Concentraciones de Elementos Minerales En Egeria Densa Planch Colectada En El Santuario de La Naturaleza Carlos Anwandter, Valdivia, Chile. Agro sur 2004, 32, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artacho, P.; Soto-Gamboa, M.; Verdugo, C.; Nespolo, R.F. Using Haematological Parameters to Infer the Health and Nutritional Status of an Endangered Black-Necked Swan Population. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2007, 147, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artacho, P.; Soto-Gamboa, M.; Verdugo, C.; Nespolo, R.F. Blood Biochemistry Reveals Malnutrition in Black-Necked Swans (Cygnus Melanocoryphus) Living in a Conservation Priority Area. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2007, 146, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UACh Estudio Sobre Origen de Mortalidades y Disminución Poblacional de Aves Acuáticas En El Santuario de La Naturaleza Carlos Anwandter, En La Provincia de Valdivia; Universidad Austral de Chile, 2005; p. 540;

- Rodríguez-Jorquera, I.A.; Lenzi, J.; Maturana, M.; Biscarra, G.; Ruiz, J.; Navedo, J.G. Exploring the Recovery of a Large Wetland Using Black-Necked Swan Blood Parameters and Body Condition 16 Years after a Pollution-Induced Disturbance. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2023, 19, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecień, M.; Samolińska, W.; Bujanowicz-Haraś, B. Effects of Iron–Glycine Chelate on Growth, Carcass Characteristic, Liver Mineral Concentrations and Haematological and Biochemical Blood Parameters in Broilers. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 2015, 99, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Molecular Mechanisms and Regulation of Iron Transport. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2003, 40, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault, T.A. Hepatic Iron Overload in Alcoholic Liver Disease: Why Does It Occur and What Is Its Role in Pathogenesis? Alcohol 2003, 30, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosik-Bogacka, D.I.; Łanocha-Arendarczyk, N. Zinc, Zn. In Mammals and Birds as Bioindicators of Trace Element Contaminations in Terrestrial Environments; Springer, Cham, 2019; pp. 363–411 ISBN 978-3-030-00121-6.

- Maret, W. Zinc and the Zinc Proteome. Met Ions Life Sci 2013, 12, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.O.; Otte, M.L. Organism-Induced Accumulation of Iron, Zinc and Arsenic in Wetland Soils. Environmental Pollution 1997, 96, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.W.; Andrews, G.A.; Beyer, W.N. Zinc Toxicosis in a Free-Flying Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus Buccinator). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2004, 40, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisler, R. Zinc Hazards to Fish, Wildlife, and Invertebrates: A Synoptic Review; Contaminant Hazard Reviews; U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service: Laurel, MD, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.; Ghaly, A.E.; Mahmoud, N.; Côté, R. Phytoaccumulation of Heavy Metals by Aquatic Plants. Environment International 2004, 29, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kant, R.; Sharma, A.K.; Sharma, A.K. Exploring the Impact of Heavy Metals Toxicity in the Aquatic Ecosystem. Int J Energ Water Res 2025, 9, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadzawka, A.; Carrasco, M.A.; Demanet, R.; Flores, H.; Grez, R.; Mora, M.L.; Neaman, A. Métodos de Análisis de Tejidos Vegetales. Serie actas INIA 2007, 40, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Saldivia, M. Determinación de Metales Pesados (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Hg, Ni, Pb y Zn) En Hígado y Riñón de Cisne de Cuello Negro (Cygnus Melancoryphus), Luchecillo (Egeria Densa), Sedimento y Agua, Recolectados En El Santuario de La Naturaleza Carlos Andwandter y Humedales Adyacentes a La Provincia de Valdivia, Universidad Austral de Chile, 2005.

- Palma-Fleming, H.; Foitzick, M.; Palma-Larrea, X.; Quiroz-Reyes, E. The Fate of α-Pinene in Sediments of a Wetland Polluted by Bleached Pulp Mill Effluent: Is It a New Clue on the “Carlos Anwandter” Nature Sanctuary Wetland Case, Valdivia, South of Chile? Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2013, 224, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Furcas, F.E.; Mundra, S.; Lothenbach, B.; Angst, U.M. Speciation Controls the Kinetics of Iron Hydroxide Precipitation and Transformation at Alkaline pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 19851–19860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzun, C.E.; Peña, L. Soil Erosion and Overland Flow in Forested Areas with Pine Plantations at Coastal Mountain Range, Central Chile. Hydrological Processes 1995, 9, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.; Bianchini Jr, I.; Cunha-Santino, M.B. Temperature and Turbidity as Drive Forces to the Growth of Egeria Densa (Planchon) under to Controlled Conditions. Aquatic Botany 2020, 164, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, N.A.; Paolini, P.; Jaramillo, E.; Lovengreen, C.; Duarte, C.; Contreras, H. Environmental Processes, Water Quality Degradation, and Decline of Waterbird Populations in the Rio Cruces Wetland, Chile. Wetlands 2008, 28, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Basant, A.; Malik, A.; Singh, K.P. Iron-Induced Oxidative Stress in a Macrophyte: A Chemometric Approach. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2009, 72, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schein, A.; Courtenay, S.C.; Crane, C.S.; Teather, K.L.; van den Heuvel, M.R. The Role of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in Structuring the Nearshore Fish Community Within an Estuary of the Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence. Estuaries and Coasts 2012, 35, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L. Submersed Vegetation as Habitat for Invertebrates in the Hudson River Estuary. Estuaries and Coasts: JERF 2007, 30, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, J.Z.; Khanna, S.; Lacy, J.R. Carbon Storage and Sediment Trapping by Egeria Densa Planch., a Globally Invasive, Freshwater Macrophyte. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 755, 142602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).