1. Introduction

The hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of substrates are determined by the Young’s contact angle

defined by [

1]

where

,

and

are the liquid-vapor, solid-vapor, and solid-liquid surface tensions, respectively. If

is less than 90°, the substrate is classified as hydrophilic; if

is greater than 90°, the substrate is classified as hydrophobic.

Experimentally, the most common method of measuring contact angle

is to observe sessile droplets: A small amount of liquid is deposited on a smooth and flat substrate, forming a droplet whose geometrical contact angle

is measured with a telescope or microscope [

2]. The morphology of the droplet changes from a shallow cap shape with a contact angle

smaller than

as shown in

Figure 1a to a nearly spherical deep cap shape with a contact angle larger than

as shown in

Figure 1b. The measured droplet’s contact angle

is then identified as the Young’s contact angle

.

Theoretically, when considering a macroscopic equilibrium wetting film of thickness

, Young’s equation (

1) is transformed into the form [

3,

4,

5]

where

represents the surface potential

of the wetting film thickness

h at the equilibrium thickness

of the wetting (adsorbed) film. This surface potential describes the molecular interaction between the liquid molecules and the substrate. The subscript “m” is used instead of “Y” to emphasize that this contact angle corresponds to that of a macroscopic droplet.

Equation (

2) is equivalent to the formula know as the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula [

6,

7,

8,

9]

where the function

is know as the disjoining pressure, which is related to the surface potential

in Eq. (

2) through:

Therefore,

. Since the formulas in Eqs. (

2)-(

4) are derived by considering the uniform thin wetting film adsorbed on to the substrate, the contact angle

calculated from them does not necessarily guarantee that they represent the actual geometrical contact angle

of the finite size droplet. Furthermore, since these formulas assume a wetting film, their utility to the hydrophobic substrate is not clear.

A connection between the surface potential

or the disjoining pressure

and the droplet’s geometrical contact angle

rather than the thermodynamic contact angle

is only establihsed through a theoretical free-energy functional model of varying degrees of sophistication. [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Among these models, Starov and Velarde [

14] provided a clear understanding of the geometrical implications of the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula (

3) for

hydrophilic substrates based on the droplet’s morphology derived from the free-energy functional model.

In this paper, we first extend Starov and Velarde’s approach to include both hydrophilic and

hydrophobic substrates. We theoretically analyze the morphology and contact angle of droplets using a simple free-energy functional model. Droplets on hydrophilic substrates are referred to as hydrophilic droplets, with their morphologies known as hydrophilic morphologies. Similarly, droplets on hydrophobic substrates are referred to as hydrophobic droplets, with their morphologies known as hydrophobic morphologies. Next, we calculate the geometrical contact angle of droplets down to the nanoscale using the developed free-energy functional model to determine if the wettability (hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity) from the geometrical contact angle is consistent with that predicted from the macroscopic contact angles calculated from Eqs. (

2) to (

3).

The organization of the present paper is as follows: We consider a strictly two dimensional system throughout to maintain the connection to the thermodynamic formulation in Eqs. (

2) to (

3). We closely follow Starov and Velarde’s work [

14] and formulate the Euler-Lagrange equation to determine the droplet morphology of not only the hydrophilic droplet but also the hydrophobic droplet from the free energy functional model that includes the effect of disjoining pressure in

Section 2. There, we also re-derive the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula [

6,

7,

14] for macroscopic contact angles for

hydrophobic droplets. In

Section 3 we use the simplest one-parameter disjoining pressure model [

19,

20,

21] and study the effect of the surface force on the morphology of droplets. In particular, we pay attention to the transition of morphology from hydrophilic to hydrophobic, as shown in

Figure 1, by changing the parameters of the surface force and the droplet’s size. In

Section 4 we will discuss the implications of our theoretical results for the concept of line tension and droplet size dependence of contact angle. Finally in

Section 5 we conclude with a short comment on our theoretical results on the wettability (hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity) at the nanoscale.

3. Geometrical Contact Angle Using a Simplified Disjoining Pressure

To study the morphology and contact angle of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic droplets, we will revisit the simplest model studied by Pekker et al. [

21]. This model employed the simplest one-parameter disjoining pressure [

19,

20,

21]

where

is the strength of the disjoining pressure,

characterizes the wetting film thickness, and

m and

n are the power-law exponents of the repulsive and attractive parts of the disjoining pressure. Then, the pressure

P in Eq. (

10) can be expressed as:

We closely follow Pekker et al. [

21] and introduce non-dimensionalization, as follows:

Equation (

14) is transformed into [

21]

where

instead of

in Eq. (

14) defined as

and

. Furthermore, a small parameter

is defined [

21] as

to characterize the wetting film thickness

and the excess pressure

P. Now the problem of morphology (hydrophilic/hydrophobic) is completely characterized by two parameters:

and

. The former represents the surrounding vapor phase through the pressure

P in Eq. (

35), and the latter represents the liquid-substrate interaction

through Eq. (

36).

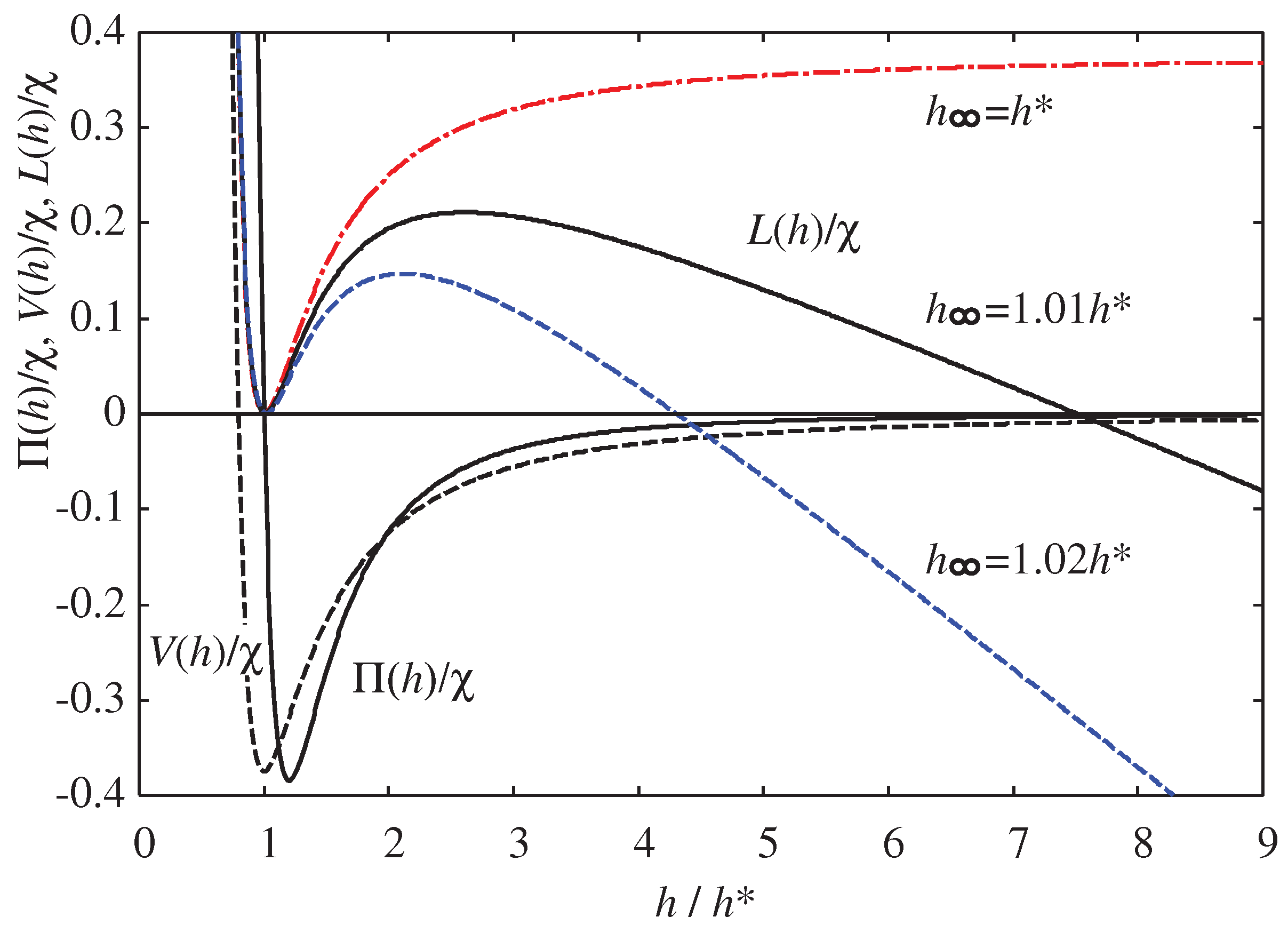

Figure 2 shows the disjoining pressure

in Eq. (

34), along with the corresponding

calculated from Eq. (

4) and

defined in Eq. (

13) for various values of

when

and

. We will utilize

and

, which resembles the Lennard-Jones potential, for numerical calculation. It is evident that

reaches a maximum near

, which is crucial for understanding the hydrophilic-hydrophobic morphological changes.

The excess pressure

P in Eq. (

35) is determined by

.

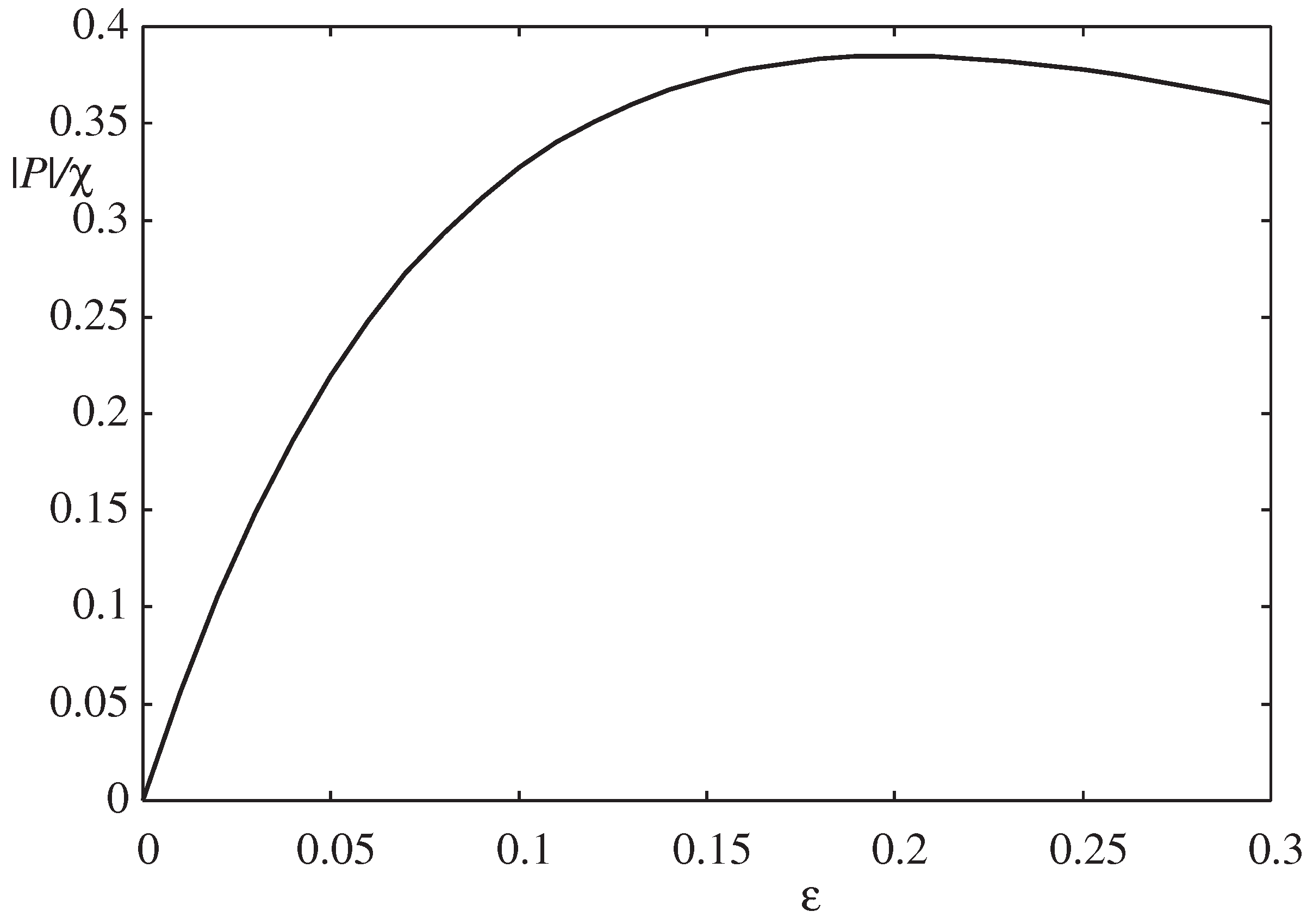

Figure 3 displays the absolute value of the pressure

as a function of the thickness parameter

instead of

when

and

. The wetting film is thinnest (

) when

and thickest (

) when [

21]

where the pressure

is at its minimum (

). For

and

,

. As the oversaturation of the surrounding vapor increases, the absolute value of the excess pressure

also increases, causing the wetting film to become thicker and the parameter

to become greater.

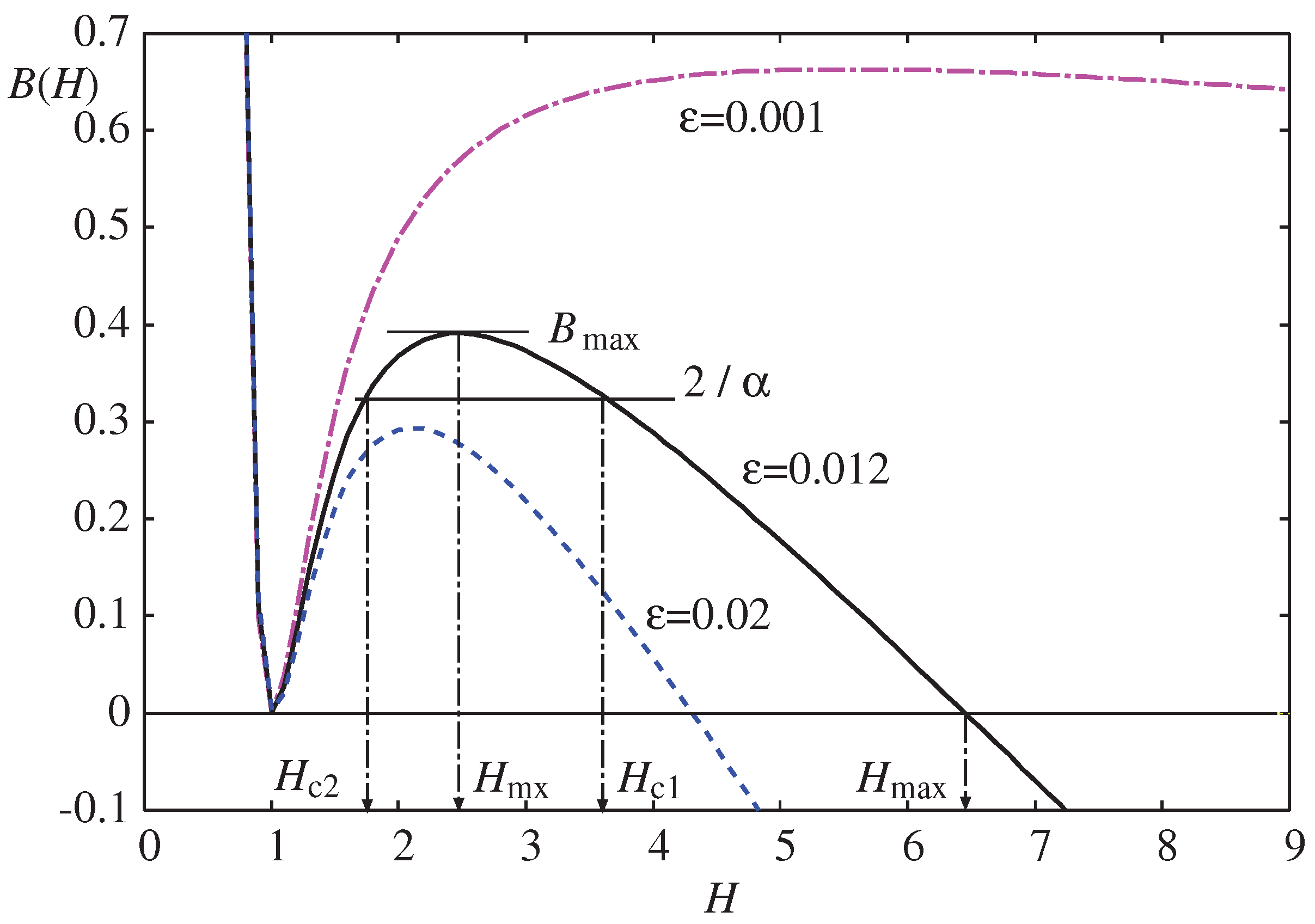

The morphology of a droplet is determined by Eq. (

37), and

Figure 4 shows the functional form of

for various values of

(

). The function

in

Figure 4 demonstrates the maximum

when

at

, which corresponds to the peak of

shown in

Figure 2. As the oversaturation of the surrounding vapor increases, the parameter

increases from 0, and

starts to show the maximum, with its position

becoming smaller.

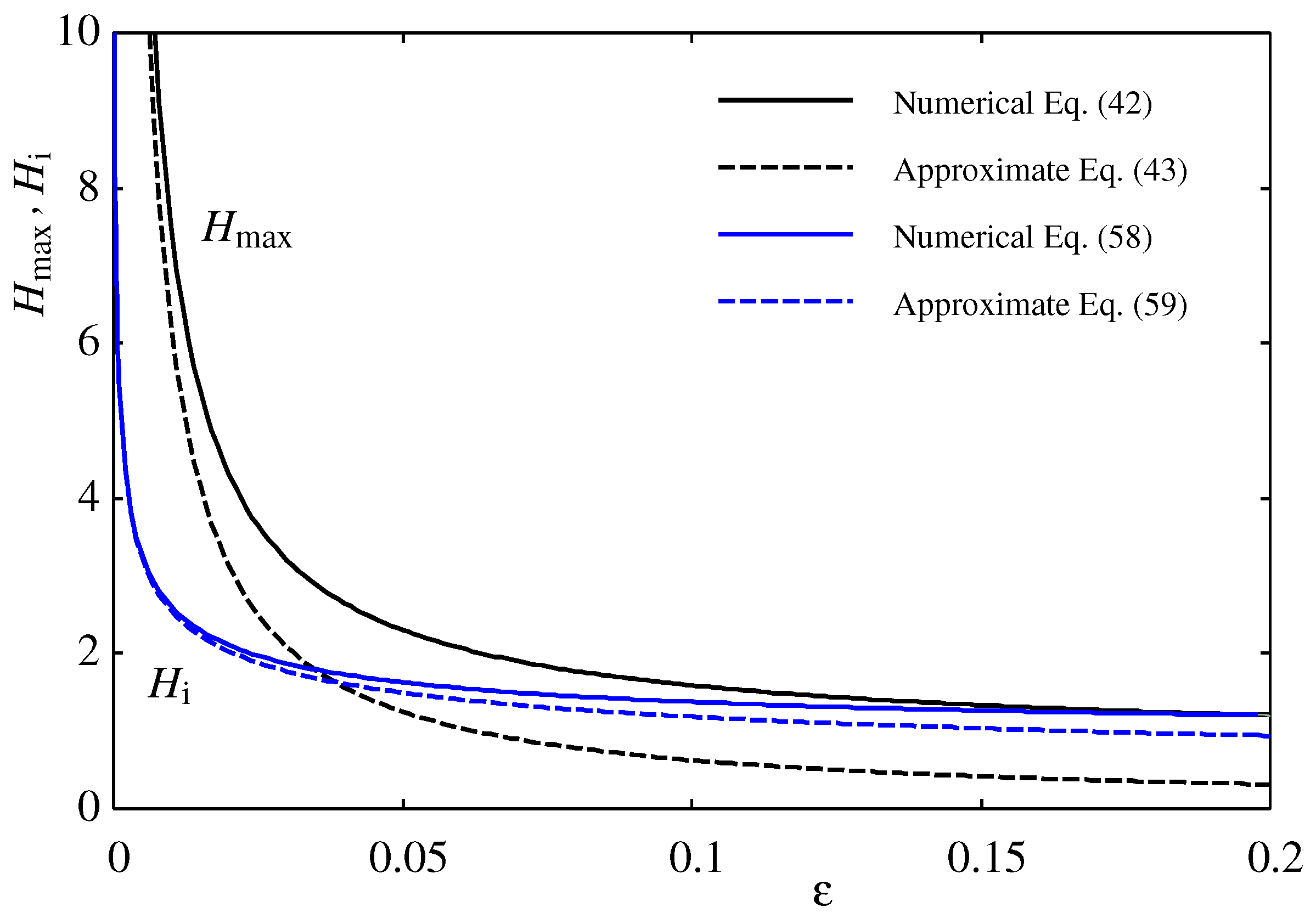

At the apex of a droplet,

, so the maximum height

of the droplet is determined by solving

from Eq. (

37). The analytical solution of Eq. (

42) in the limit

is [

21]

It is important to note that this result is independent of the strength of the disjoining pressure

. Therefore, once the pressure

P or the film thickness

is fixed, the maximum height is determined from Eq. (

42) regardless of the droplet’s hydrophilic or hydrophobic nature. In

Figure 5, we compare the maximum height

calculated numerically from Eq. (

42) and from the approximate analytical formula [

21] in Eq. (

43). The droplet’s maximum height

decreases as the oversaturation and

increase. The analytical formula is most accurate near

for large droplets (large

).

A droplet solution can only exist when

in Eq. (

37) or

where

is the maximum of

. Equation (

37) can be written as

The sign (±) should be chosen according to the droplet’s hydrophilic or hydrophobic nature and the position

H of the meniscus. For

, the sign should always be negative (

) for hydrophilic droplets (see

Figure 1a). However, for hydrophobic droplets, it changes sign: it is negative (

) near the apex

and changes sign to

at the middle, and changes again to

near the wetting film at

(see

Figure 1b)). Equation (

45) can be easily integrated by choosing the appropriate sign to give the morphology of the droplet, which is controlled by

and

. The former,

, determines the functional form of

and the latter

determines the morphology (a hydrophilic or a hydrophobic droplet).

The morphology of a droplet can be controlled by the strength

of the surface potential or the disjoining pressure. In a hydrophobic droplet in

Figure 1b, the lateral size reaches a maximum and minimum at two critical height,

and

(

and

in

Figure 1), where

and

, respectively (see

Figure 1b). These conditions are met when

from Eq. (

45).

Figure 4 also displays the graphical determination of the intersections

and

. It is evident from this figure that the condition for the appearance of a hydrophobic droplet is when

which combined with Eq. (

44), results in

or

using the relation between

and

in Eq. (

39), where

is the maximum of

(see

Figure 2 and

Figure 4).

Therefore, a scenario different from Eq. (

33) emerges in Eq. (

49) to distinguish between the hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of finite size droplets. A macroscopic droplet with

is realized when

(See

Figure 5), resulting in the vanishing of excess pressure

(

Figure 3) and the increase of the maximum position

of

to

(

Figure 4) and

(

Figure 2). Consequently,

from Eq. (

13), and Eq. (

49) simplifies to Eq. (

33). However, microscopic and nanoscopic droplets whose wettability is predicted from Eqs. (

48) and (

49) and macroscopic droplets whose wettability is predicted from Eq. (

33) may exhibit contradicting wettability (hydrophilic/hydrophobic) depending on the droplet size.

The position

of the maximum of

is determined by solving

or

from Eq. (

38), and the maximum is given by

In the limit

(

), the approximate solution of Eq. (

50) becomes

and Eq. (

51) becomes

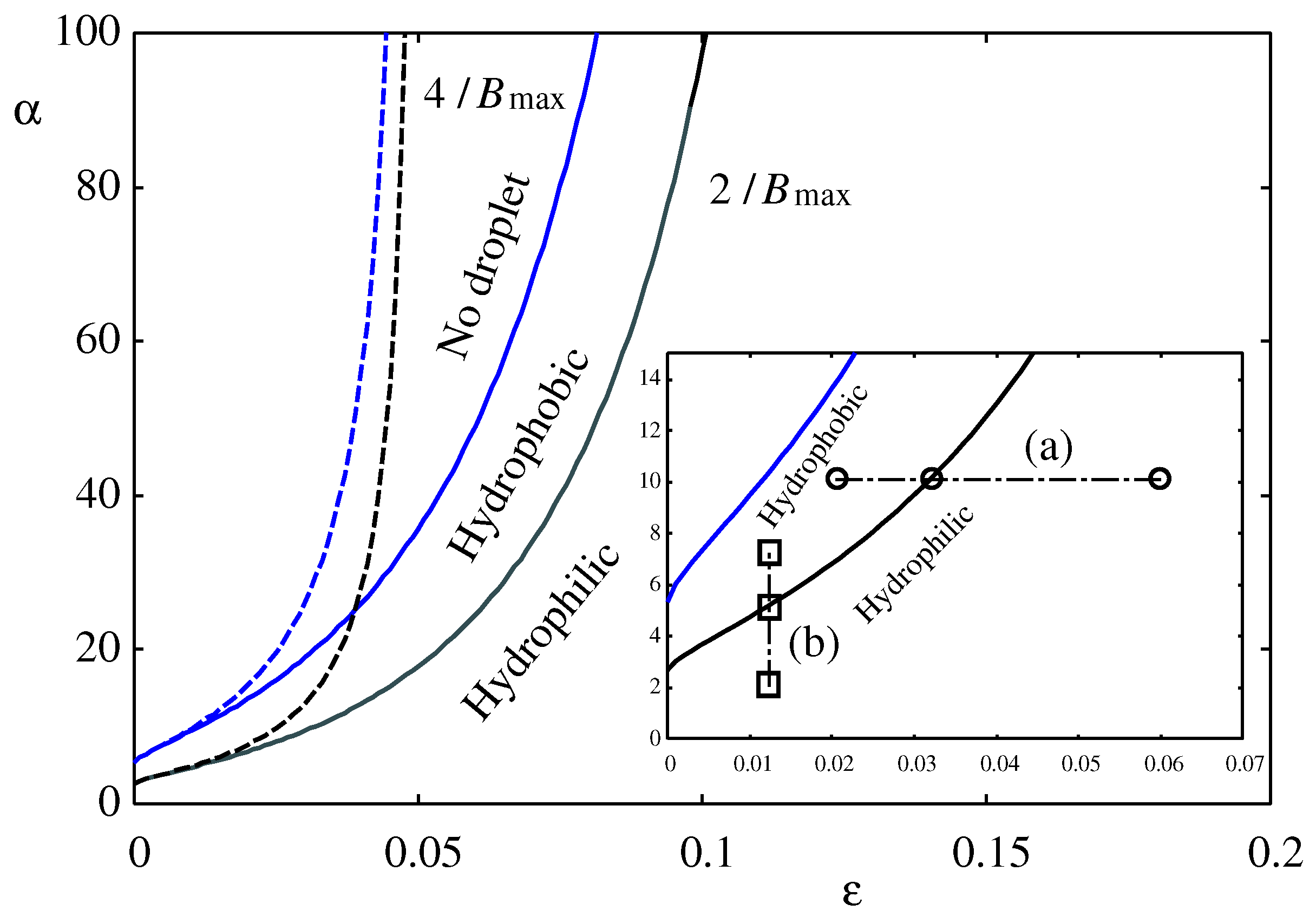

In

Figure 6, the boundary values for no-droplet,

, and hydrophilic-hydrophobic,

are plotted as a function of

. The dashed lines represent the approximate formula in Eq. (

53), which is only valid for

. As

, these boundaries converge to

and

as predicted by Eq. (

53). The inset of

Figure 6 shows an expanded view around

with two paths (a) and (b) along which the morphologies in

Figure 7a and

Figure 7b are calculated.

Therefore, within this disjoining pressure model in Eq. (

34) the condition for macroscopic droplets in Eq. (

33) is now given as

derived from Eq. (

48) when

.

For a fixed

, the height of the droplet

(Eq. (

42)) as well as the excess pressure

P (Eq. (

35)) and, therefore, the Laplace radius

(Eq. (

17)) are fixed. As the strength of the liquid-substrate interaction

(

) is increased, making the disjoining pressure

stronger and the surface potential

more attractive (see

Figure 2),

Figure 6 indicate that the droplet morphology changes from hydrophilic to hydrophobic as shown in

Figure 1. Finally, the droplet is detached from the substrate and disappears, leaving a wetting film behind. This scenario is consistent with the Frumkin-Derjyaguin formula in Eqs. (

2) and (

3).

When the liquid is more strongly attracted to the substrate, the droplet will spread and the substrate will be more hydrophilic. In fact, many numerical simulations mostly for the Lennard-Jones model fluid using molecular dynamics [

23,

24,

25,

26] or density functional theory [

16,

27] indicate that when the liquid-substrate molecular interaction is more attractive, the contact angle becomes smaller making the droplet more hydrophilic. Superficially, these results seem to contradict the prediction of

Figure 6 based on disjoining pressure.

The statistical mechanical definition of the disjoining pressure [

9,

28,

29] that links fluid-wall molecular interactions to the disjoining pressure is established. Several attempts have been made to determine the disjoining pressure and surface potential using Monte Carlo simulation [

28] and density functional theory [

16,

30,

31,

32], primarily for the Lennard-Jones model fluid. These results suggest that as the fluid-wall interaction becomes stronger and more attractive, the surface potential

or the disjoining pressure

becomes less attractive. The potential minimum (

Figure 2) also becomes shallower, resulting in a lower contact angle from Eq. (

2). Therefore, the hydrophilic-hydrophobic boundary in

Figure 6 and the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula in Eqs. (

2)-(

4) do not contradict the prediction of simulations [

16,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Knowing the conditions in Eqs. (

48) and (

49), we consider the morphology of the droplet in more detail. First, we will examine the simple hydrophilic morphology. In this case, the function

does not intersect

because

(see

Figure 4) and

for

from the apex at

down to the wetting film at

(

Figure 1a). The meniscus is obtained simply by integrating

from Eq. (

45) because

, and the meniscus is given by

which can be evaluated numerically.

Next we will consider the hydrophobic morphology. In this case, Eq. (

46) has two solutions

and

(

, see

Figure 4). Within the interval

,

(see

Figure 1b) and

once again (

Figure 4). Therefore, the meniscus is determined by Eq. (

55). However, in the interval

,

(

Figure 1b) and

(

Figure 4). Despite this, the meniscus is still determined by Eq. (

55) because the denominator is negative (

). Lastly, within the interval

,

(

Figure 1b) and

(

Figure 4) resulting in the meniscus being determined by Eqs. (

55) since

.

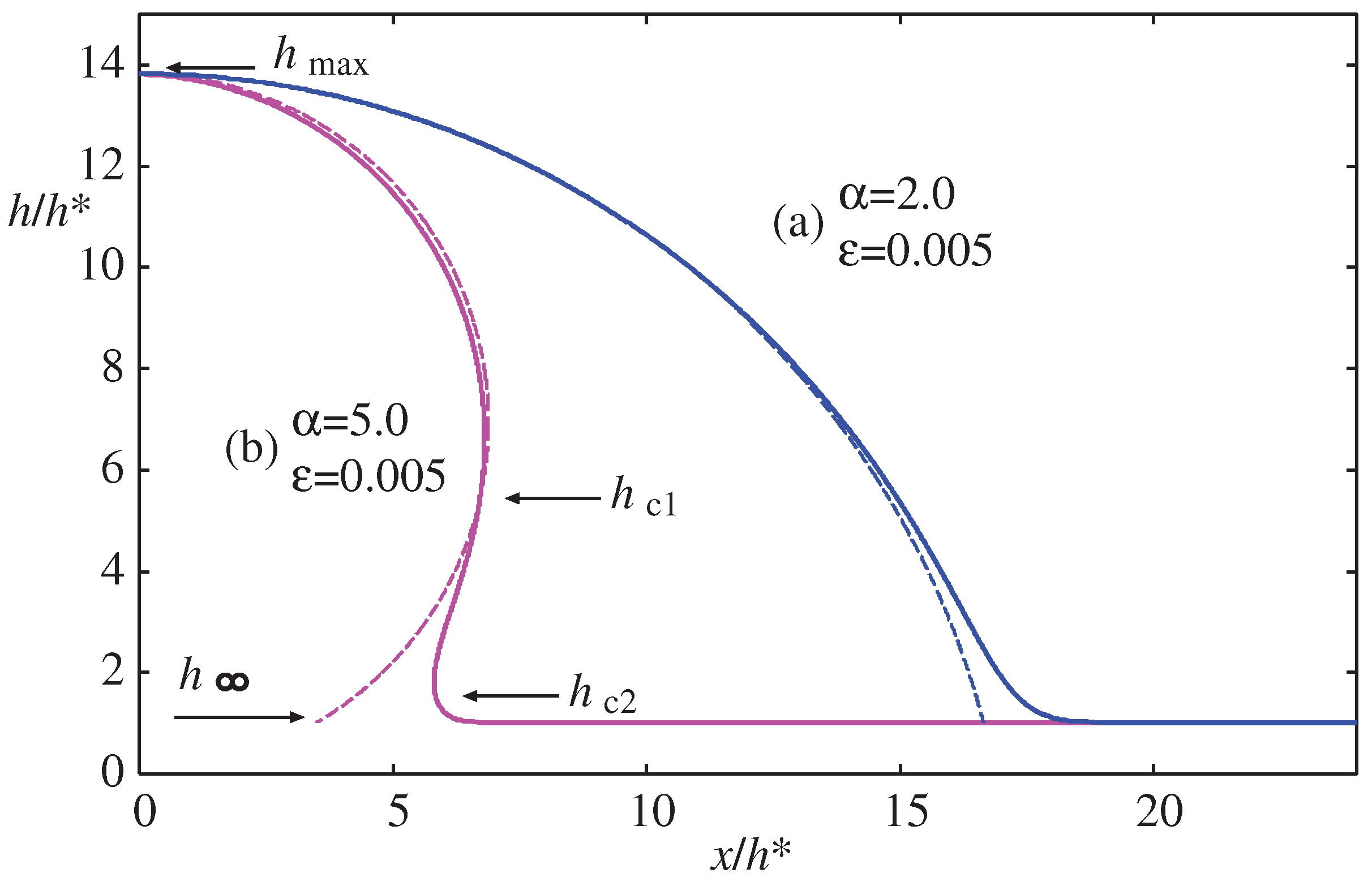

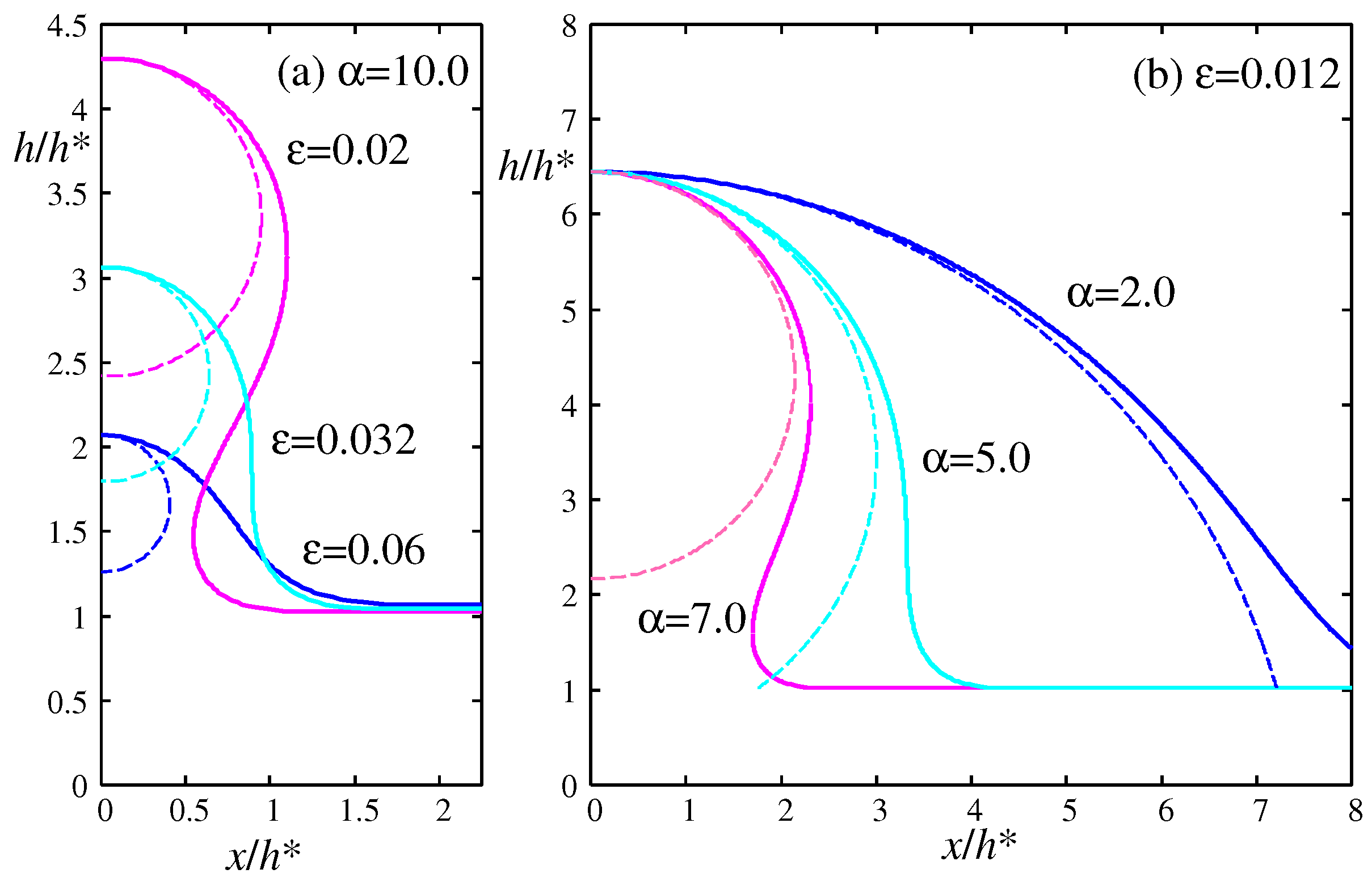

Figure 7a illustrates the numerically calculated morphology of the meniscus for the same value of

but different values of

along the path (a) indicated in the inset of

Figure 6. The morphology transitions from hydrophobic (

) to neutral (

) with a contact angle of nearly

, to hydrophilic (

). The dashed lines represent the cylindrical meniscus with the Laplace radius calculated from Eq. (

17). This approximation is not suitable for smaller droplets because the cylindrical meniscus cannot reach the wetting film, and the contact angle cannot be determined.

Figure 7b shows the morphology of the meniscus for the same value of

but different values of

along the path (b) indicated in the inset of

Figure 6. The morphology changes from hydrophobic (

) to neutral (

) to hydrophilic (

). In this case (b) the height

is fixed as it does not depend on

from Eq. (

42). The parameter sets

used to calculate the morphologies in

Figure 7 are indicated by circular and square symbols in the inset of

Figure 6 and

Figure 8.

Finally, we consider the contact angle which depends on the definition. Pekker et al. [

21] derived an approximate analytical formula for the contact angle of this simplified droplet model. They defined the contact angle

as the slope of the meniscus:

at the inflection point (height)

(

) defined by

, which leads to

from Eqs. (

9) and (

10). The approximate solution of Eq. (

58) in the limit

is obtained as [

21]

and

Then, the effective contact angle

is given by [

21]

from Eqs. (

55) and (

57) for both a hydrophilic morphology and a hydrophobic morphology. In

Figure 5 we also compared the height of the inflection point

calculated from the approximate formula in Eq. (

52) with the exact numerical results from

in Eq. (

58). Apparently, the approximate formula in Eq. (

59) and therefore that in Eq. (

60) are valid only near

. In particular, the formula in Eq. (

60) does not depend on

, so Eq. (

61) must be valid only near

.

Similarly, the integration in Eq. (

3) can be obtained analytically, providing us with an explicit expression for the macroscopic contact angle

:

from the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula [

6,

7,

14] in Eq. (

3), which simplifies to

in the limit

. It is evident from Eqs. (

61) and (

63) that the contact angle

from the formula of Pekker et al. [

21] in Eq. (

61) and

from the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula in Eq. (

63) are identical as

. Equation (

63) and, thererfore, Eq. (

61) have a solution only when

and the hydrophilic-hydrophobic boundary is at

as summarized in Eq. (

54).

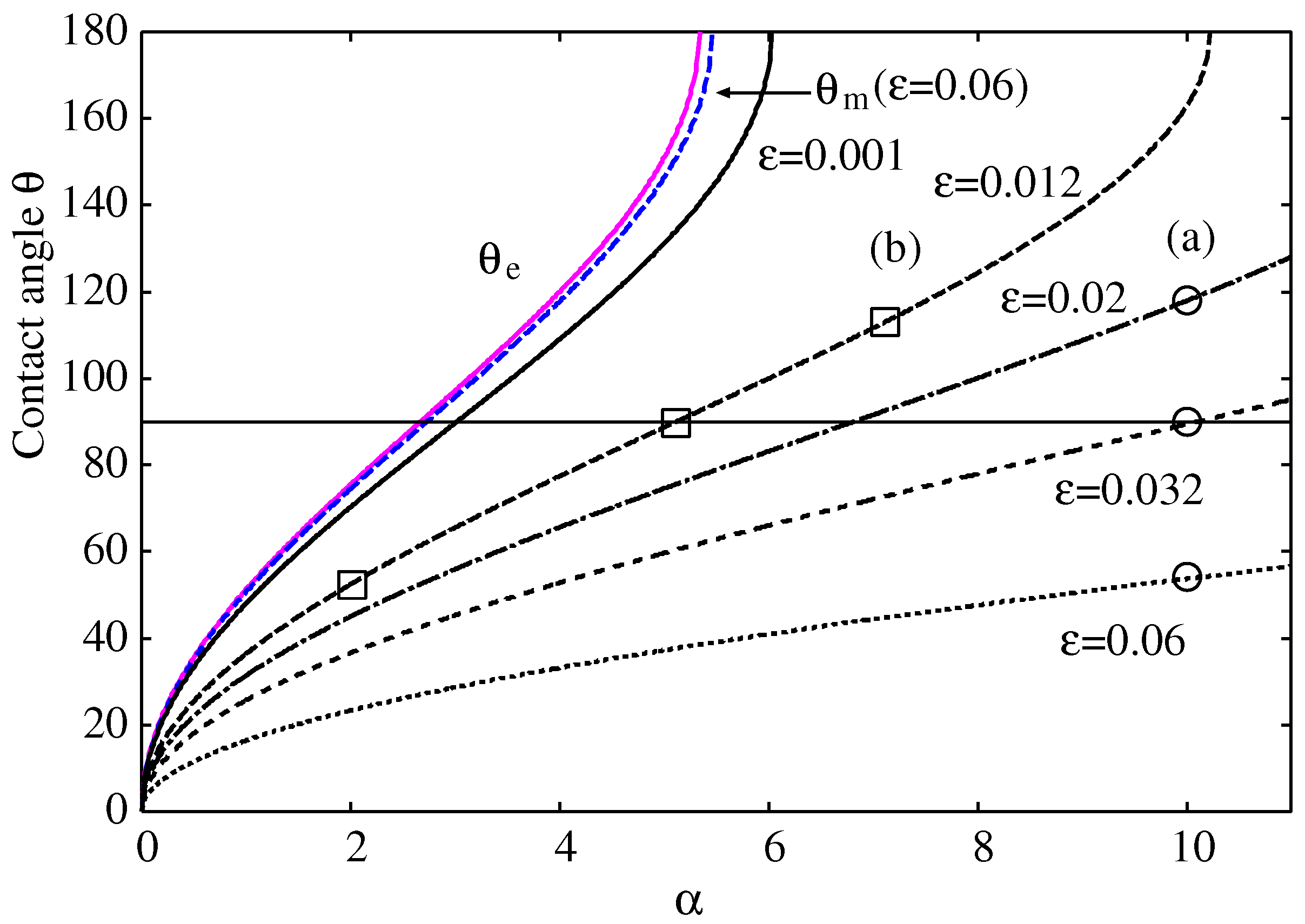

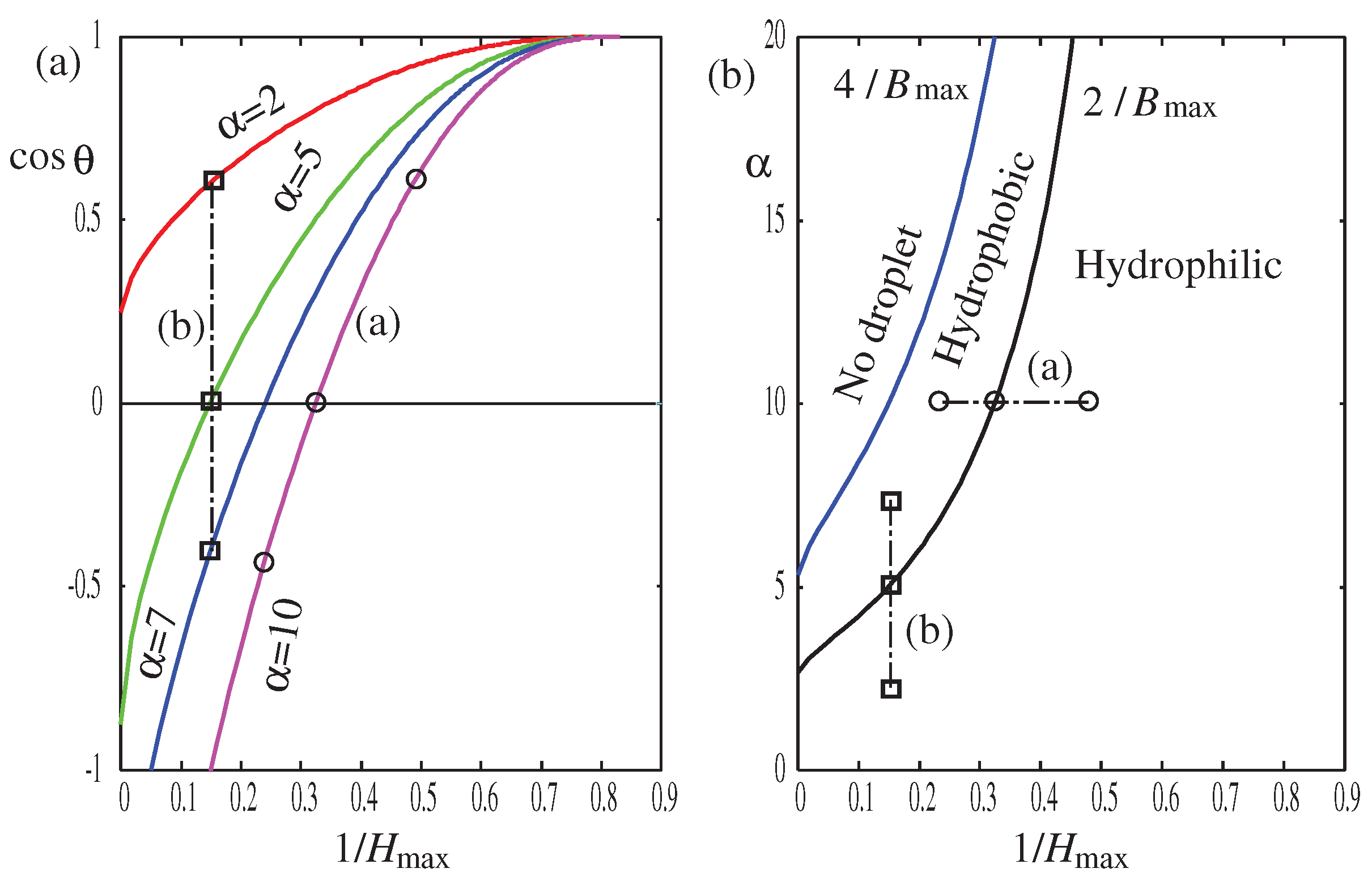

In

Figure 8, we compare the effective contact angle

and the macroscopic contact angle

calculated from the analytical formulas in Eqs. (

61) and (

62) with the exact numerical results

calculated from Eq. (

57). The formulas of Pekkers et al. [

21] and that of Derjaguin-Frumkin [

6,

7,

14] yield similar results, but they generally produce larger values than the exact numerical results, significantly overestimating the contact angles for hydrophobic droplets with larger

(stronger surface potentials) and larger

(smaller droplets, see

Figure 5). Specifically, the numerical results of the contact angle for

in

Figure 8, indicated by the square symbols, are in full agreement with the morphological change of the droplet shown in

Figure 7b. Likewise, those indicated by circular symbols with

are consistent with the morphological change in

Figure 7a.

The values of the contact angles,

, calculated numerically from the exact expression in Eq. (

57), are compared with those of

and

from the approximate formulas in Eqs. (

61) and (

62) in

Table 1 for the droplets shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 7. The approximate formulas are reasonable for the larger droplets in

Figure 1, but they consistently overestimate the contact angles. For smaller droplets in

Figure 7, the approximate formulas significantly overestimate the contact angles, and they cannot even be used as shown in

Figure 8 because the cylindrical approximation for the meniscus completely fails as shown in

Figure 7a.

The numerical results based on the simplified disjoining pressure in

Figure 8 and

Table 1 suggest that the droplet remains hydrophilic (

) even when the two analytical formulas by Pekker et al. [

21] in Eq. (

61) and Derjaguin-Frumkin [

6,

7,

14] in Eq. (

62) predict a hydrophobic character (

) up to the limit

of Eq. (

54) for

and

. Therefore, the effect of this simplified disjoining pressure makes smaller droplets more hydrophilic and less hydrophobic, resulting in a smaller contact angle. Furthermore, a droplet can be hydrophilic or hydrophobic beyond the limit

. However, this argument does not necessarily invalidate the two analytical formulas in Eqs. (

61) and (

62) because they were originally designed for larger droplets with

, which can be regarded as cylindrical droplets. Even though we restrict ourselves to the two-dimensional cylindrical droplets throughout this paper, the effect of the surface force would be qualitatively the same for the three-dimensional spherical droplets.

4. Discussion

Finally, we will discuss the implications of our theoretical results for real experiments. Within the disjoining pressure model used in this study, the small

approximation would be reasonable only for

, as shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 8. Specifically, the effective contact angle

in Eq. (

61) and the macroscopic contact angle

from the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula in Eq. (

3) are reasonable for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic droplets only when

, as indicated in

Figure 8. Since Eq. (

43) yields

for

,

and

, the macroscopic formulas in Eqs. (

61) and (

62) are applicable to large droplets with a height greater than approximately 63 times

from Eq. (

36). Assuming the wetting film height is

nm [

8], the minimum droplet height would be

nm. For droplets taller than, let’s say, 100 nm, the macroscopic formula in Eq. (

62) and therefore the Derjaguin-Frumkin formula in Eq. (

3) would be applicable to both hydrophilic and hydrophobic droplets. For a nanoscale droplet shorter than, let’s say, 100 nm, the total volume of the droplet is influenced by disjoining pressure, making it more hydrophilic with a lower contact angle compared to a macroscopic droplet of cm to

m size.

The relationship between droplet size and contact angle has been studied experimentally for many years, with the main focus being on determining the line tension, denoted as

, defined through the phenomenological modified Young’s equation [

33,

34,

35]

where

is the radius of contact line and

is the contact angle of the macroscopic droplet. We can identify

in Eq. (

61) in the model of

Section 3. Since our model is two-dimensional and

, the contact angle should not depend on the size of the droplet as the line tension

does not play a role in modifying the contact angle. However, the contact angle does depend on the size of the droplet as shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9a. In

Figure 9a, we plot the cosine of the contact angle

versus the inverse of the droplet’s height

. In

Figure 9b, we redraw

Figure 6 using

instead of

, which are related through Eq. (

42) and

Figure 5.

Figure 9b shows that smaller droplets tend to be more hydrophilic.

Our calculations in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 suggest that as the droplet size decreases (

), the droplet becomes more hydrophilic and the contact angle is smaller, indicating negative line tension

for three-dimensional droplets. Interestingly, most of the old experimental data for macroscopic droplets of cm and mm sizes show an opposite trend: as the droplet size decreases, the contact angle increases [

36,

37], meaning positive line tension

. However, experimental results for nanoscale droplets using atomic-force microscopy (AFM) [

38,

39,

40,

41] and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [

42] are mostly consistent with our findings: the smaller the droplet, the lower the contact angle, indicating negative line tension. Furthermore, our highly nonlinear convex curve in

Figure 9a resembles some of the previous experimental results [

39,

40]. We can estimate the effective line tension by identifying

in Eq. (

64). From

Figure 9a, we can estimate the slope of the curve

as

, which can be translated into the effective line tension using

nm [

8] and

mN/m (water) [

2] as

N, which is negative and the right order of magnitude of experimental observation. The absolute magnitude

decreases as the droplet becomes smaller (

).

The size dependence of the contact angle of nanoscale droplets has also been studied by molecular dynamics simulation [

24,

25,

26] and density functional theory [

27]. Furthermore, the determination the sign and magnitude of line tension has also been attempted by molecular dynamics [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Some of them [

26,

27] indicate positive line tension (

), while some [

24,

25,

43] are consistent with our results in

Figure 9a:

or the contact angle decreases as the size of the droplet shrinks. Some [

44,

45,

46] also indicate that the sign depends on the wettability (Hydrophilic/hydrophobic) of the substrate.

Of course, our numerical results based on the one-parameter disjoining pressure model cannot resolve these contradictory results. However, our results, along with some of the previous results for cylindrical droplets [

43,

44,

45], suggest the limited utility of the line tension concept and the modified Young’s equation (

54) at the nanoscale. Although line tension includes the combined effect of various size-dependence factors such as the surface tension by Tolman’s length [

44,

47,

48], the main origin is the localized surface potential

or the disjoining pressure

acting only near the contact line [

11,

35,

38,

47,

48]. For droplets at the nanoscale, where the entire volume is under the influence of surface potential, such a line tension concept may not hold true. Instead, the volume force acting on the total volume of the droplet is responsible for the size dependence of the contact angle. This same conclusion was recently reached by Tan et al. [

49], who showed that the contact angle of mm to cm-sized droplets can be largely explained by the gravitational body force and that of nanoscale droplets can also be explained by a Lennard-Jones type inter-molecular body force between liquid molecules and the substrate. The limitation of the line tension concept for nanoscale droplet was also argued by Stocco and Möhwald [

50], who used disjoining pressure instead of intermolecular body force and studied the surface morphology of nanoscale droplets.