Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

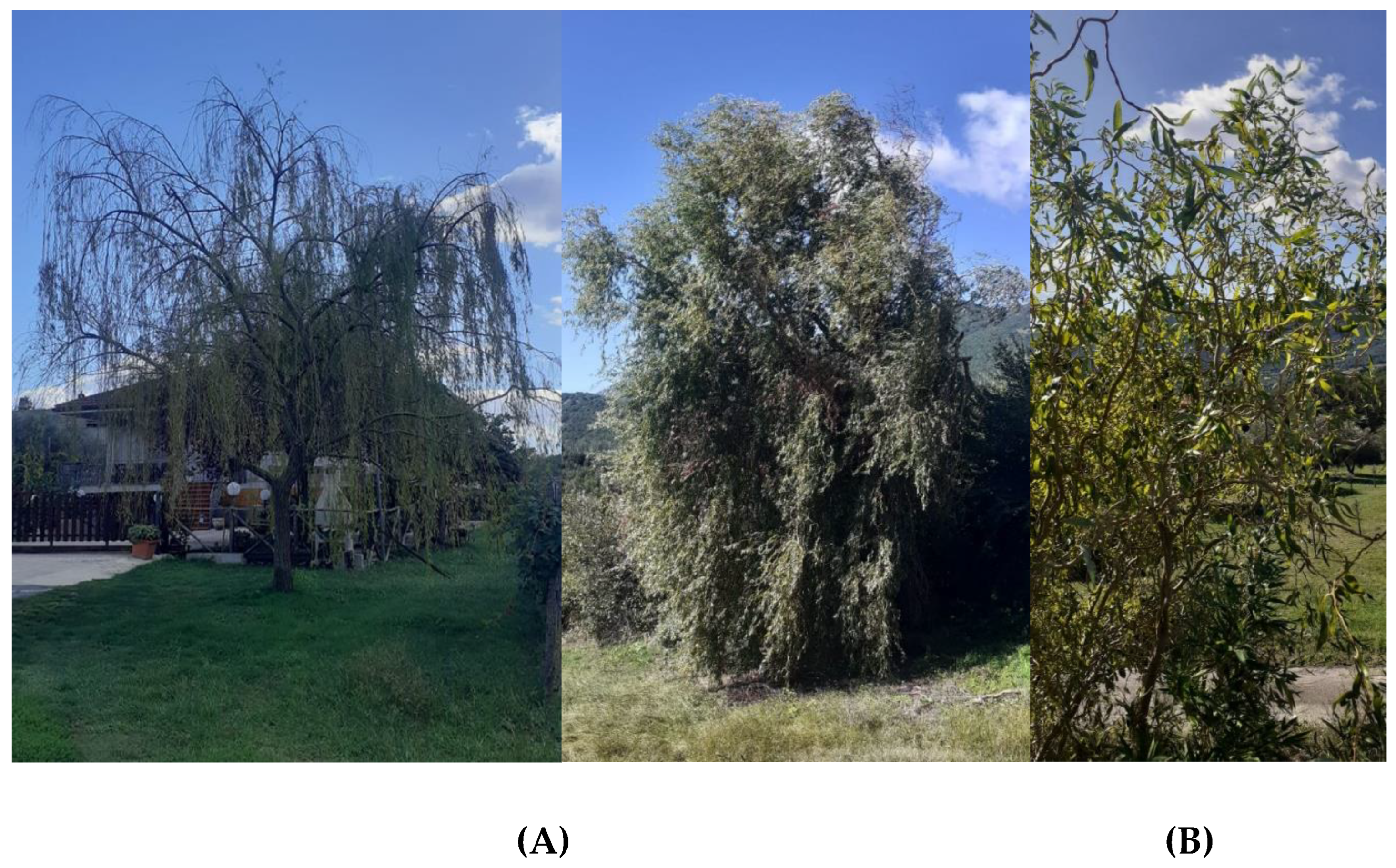

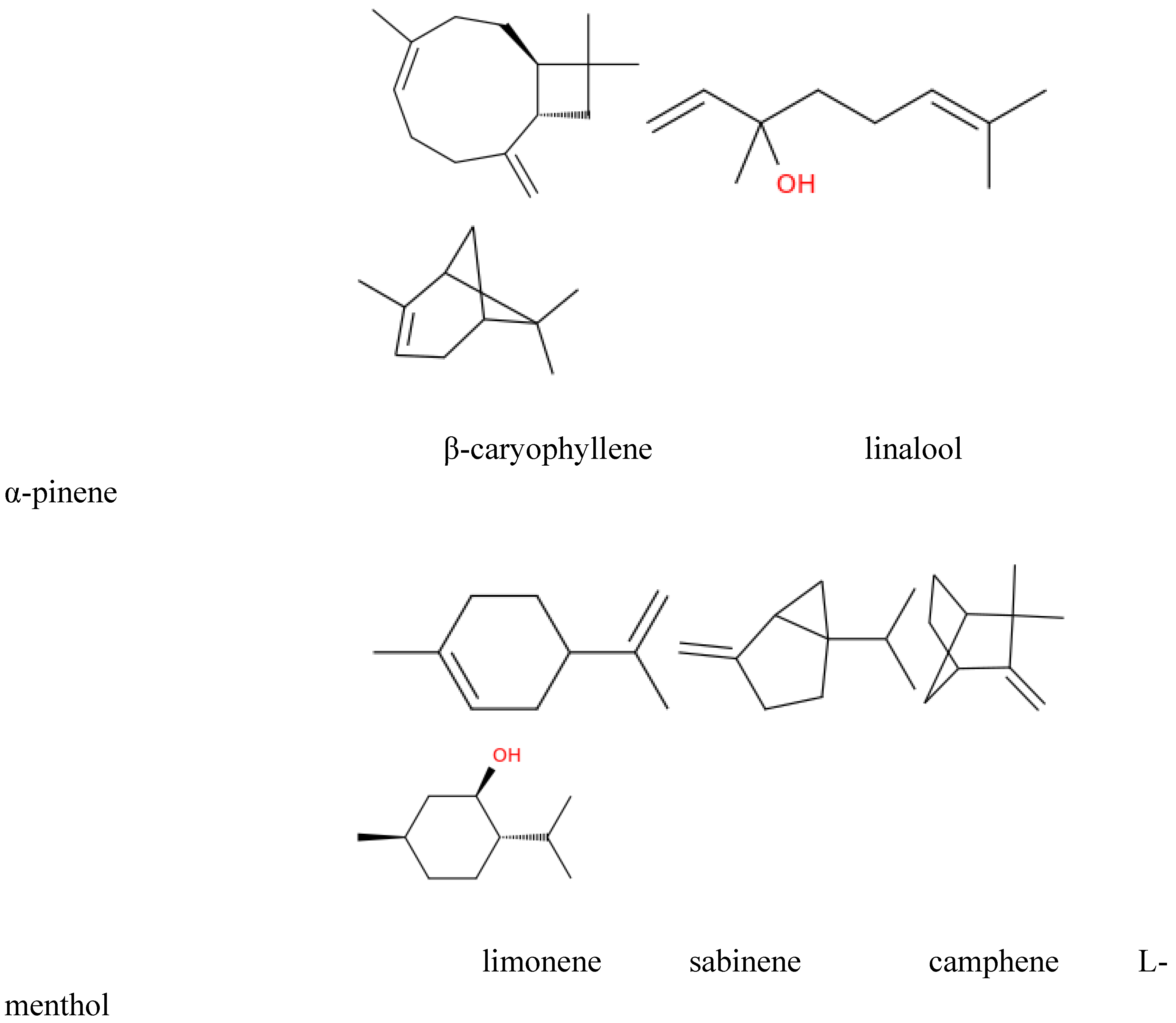

Air pollution, soil contamination, and rising illness demand integrated, nature‑based solutions. Willow trees (Salix spp.) uniquely combine ecological resilience with therapeutic value, remediating polluted environments while supporting human wellbeing. This review synthesizes recent literature on the established role of Salix spp. in phytoremediation and growing contribution to forest therapy through emissions of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs). As urbanization accelerates and environmental pressures intensify globally, Salix surprising adaptability and multifunctionality justify the utilization of this genus in building resilient and health-promoting ecosystems. The major points discussed in this work include willow-based phytoremediation strategies, such as rhizodegradation, phytoextraction, and phytostabilization, contribute restoring even heavily polluted soils, especially when combined with specific strategies of microbial augmentation and trait-based selection. Salix plantations and even individual willow trees may contribute to forest therapy (and ‘forest bathing’ approaches) through volatile compounds emitted by Salix spp. such as ocimene, β-caryophyllene, and others, which exhibit neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and mood-enhancing properties. Willow’s significantly extended foliage season in temperate regions allows for prolonged ‘forest bathing’ opportunities, enhancing passive therapeutic engagement in urban green infrastructures. Famously, the pharmacological potential of willow extends beyond salicin, encompassing a diverse array of phytocompounds with applications in phytomedicine. Finally, willow’s ease of propagation and adaptability make this species a convenient solution for multifunctional landscape design, where ecological restoration and human wellbeing converge. Overall, this review demonstrates the integrative value of Salix spp. as a keystone genus in sustainable landscape planning, combining remarkable environmental resilience with therapeutic benefit. Future studies should explore standardized methods to evaluate the combined ecological and therapeutic performance of Salix spp., integrating long-term field monitoring with mechanistic analyses of BVOC emissions under varying environmental stresses.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Phytoremediation Potential of Willow Species

2.1. Phytoremediation Mechanisms of Willow

2.2. Salix Ecological Adaptability Economic Benefits and Microbial Synergies

3. Volatile Emissions and Forest Therapy: Willow-Derived Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds

3.1. Willow Volatiles Enhancing Forest Therapy and Human Wellbeing

4. Therapeutic Applications and Pharmacological Properties of Willow and its Bioactive Compounds

4.1. Historical Therapeutic Use of Willow

4.2. Willow in Modern Medicine

5. Urban Willows: Integrating Green Infrastructure and Public Health

5.1. Willow in Urban Parks as Multisensory Therapeutic Landscapes

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vervaeke, P.; Luyssaert, S.; Mertens, J.; Meers, E.; Tack, F.; Lust, N., Phytoremediation prospects of willow stands on contaminated sediment: a field trial. Environmental pollution 2003, 126, (2), 275-282. [CrossRef]

- Rajoo, K. S.; Karam, D. S.; Abdullah, M. Z., The physiological and psychosocial effects of forest therapy: A systematic review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2020, 54, 126744. [CrossRef]

- Wuytack, T.; Verheyen, K.; Wuyts, K.; Kardel, F.; Adriaenssens, S.; Samson, R., The potential of biomonitoring of air quality using leaf characteristics of white willow (Salix alba L.). Environmental monitoring and assessment 2010, 171, (1), 197-204. [CrossRef]

- Puk, T., Nature-based regenerative healing: Nature and neurons. European Journal of Ecopsychology 2024, 9, 111-139.

- Vujcic, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J.; Grbic, M.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Vukovic, O.; Toskovic, O., Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environmental research 2017, 158, 385-392. [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U. K.; Palsdottir, A. M.; Burls, A.; Chermaz, A.; Ferrini, F.; Grahn, P., Nature-based therapeutic interventions. In Forests, trees and human health, Springer: 2010; pp 309-342.

- Santamour, F. S.; McArdle, A. J., Cultivars of Salix babylonica and other weeping willows. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry (AUF) 1988, 14, (7), 180-184. [CrossRef]

- Marasek-Ciolakowska, A.; Wiczkowski, W.; Szawara-Nowak, D.; Kaszubski, W.; Goraj-Koniarska, J.; Mitrus, J.; Saniewski, M.; Horbowicz, M., Effect of natural light on the development of adventitious roots in stem cuttings of Salix babylonica" Tortuosa": Histological and metabolic evaluation. Journal of Elementology 2025, 30, (1).

- Papale, D.; Guidolotti, G.; Mattioni, M.; Nicolini, G.; Sabbatini, S.; Sconocchia, P.; Antoniella, G.; Barbati, A.; Cecca, D.; Chiti, T. In When a Natural Disaster Becomes an Opportunity for a Holistic Assessment of Ecosystem Restoration Strategies, AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, 2024; pp B21A-02.

- Zhu, Y.; Gu, H.; Li, H.; Lam, S. S.; Verma, M.; Ng, H. S.; Sonne, C.; Liew, R. K.; Peng, W., Phytoremediation of contaminants in urban soils: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2024, 22, (1), 355-371. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lun, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J., Biogenic volatile organic compounds emissions, atmospheric chemistry, and environmental implications: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2024, 22, (6), 3033-3058. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, N.; Anand, U.; Kumar, R.; Ghorai, M.; Aftab, T.; Jha, N. K.; Rajapaksha, A. U.; Bundschuh, J.; Bontempi, E.; Dey, A., Phytoremediation and sequestration of soil metals using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to modify plants: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 21, (1), 429-445. [CrossRef]

- El-Ramady, H. R.; Abdalla, N.; Alshaal, T.; Elhenawy, A. S.; Shams, M. S.; Faizy, S. E.-D.; Belal, E.-S. B.; Shehata, S. A.; Ragab, M. I.; Amer, M. M., Giant reed for selenium phytoremediation under changing climate. Environmental chemistry letters 2015, 13, (4), 359-380. [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, B.; Milović, M.; Kesić, L.; Pajnik, L. P.; Pekeč, S.; Stanković, D.; Orlović, S., Interclonal Variation in Heavy Metal Accumulation Among Poplar and Willow Clones: Implications for Phytoremediation of Contaminated Landfill Soils. Plants 2025, 14, (4), 567. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jia, H.; Zhu, K.; Zhao, S.; Lichtfouse, E., Formation of environmentally persistent free radicals and reactive oxygen species during the thermal treatment of soils contaminated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2020, 18, (4), 1329-1336. [CrossRef]

- Lichtfouse, E.; Sharma, V. K.; Dionysiou, D. D., The arms race of environmental scientists to purify contaminated water. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2024, 22, (6), 2607-2609. [CrossRef]

- Etim, E., Phytoremediation and its mechanisms: a review. Int J Environ Bioenergy 2012, 2, (3), 120-136.

- Saier Jr, M.; Trevors, J., Phytoremediation. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 2010, 205, (Suppl 1), 61-63.

- Newman, L. A.; Reynolds, C. M., Phytodegradation of organic compounds. Current opinion in Biotechnology 2004, 15, (3), 225-230.

- Limmer, M.; Burken, J., Phytovolatilization of organic contaminants. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50, (13), 6632-6643.

- Khan, M. S.; Zaidi, A.; Wani, P. A.; Oves, M., Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in the remediation of metal contaminated soils. Environmental chemistry letters 2009, 7, (1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Ozyigit, I. I.; Can, H.; Dogan, I., Phytoremediation using genetically engineered plants to remove metals: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2021, 19, (1), 669-698. [CrossRef]

- Mille, T.; Graindorge, P. H.; Morel, C.; Paoli, J.; Lichtfouse, E.; Schroeder, H.; Grova, N., The overlooked toxicity of non-carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2024, 22, (4), 1563-1567. [CrossRef]

- Vervaeke, P.; Luyssaert, S.; Mertens, J.; Meers, E.; Tack, F. M. G.; Lust, N., Phytoremediation prospects of willow stands on contaminated sediment: a field trial. Environmental Pollution 2003, 126, (2), 275-282. [CrossRef]

- Nissim, W. G.; Jerbi, A.; Lafleur, B.; Fluet, R.; Labrecque, M., Willows for the treatment of municipal wastewater: Performance under different irrigation rates. Ecological engineering 2015, 81, 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, I.; Aronsson, P., Willows for energy and phytoremediation in Sweden. UNASYLVA-FAO- 2005, 56, (2), 47.

- Landberg, T.; Greger, M., Phytoremediation Using Willow in Industrial Contaminated Soil. Sustainability 2022, 14, (14). [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. H.; Mills, T. M.; Petit, D.; Fung, L. E.; Green, S. R.; Clothier, B. E., Natural and induced cadmium-accumulation in poplar and willow: Implications for phytoremediation. Plant and Soil 2000, 227, (1-2), 301-306. [CrossRef]

- Pulford, I. D.; Riddell-Black, D.; Stewart, C., Heavy Metal Uptake by Willow Clones from Sewage Sludge-Treated Soil: The Potential for Phytoremediation. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2006, 4, (1), 59-72. [CrossRef]

- Volk, T.; Abrahamson, L.; Nowak, C.; Smart, L.; Tharakan, P.; White, E., The development of short-rotation willow in the northeastern United States for bioenergy and bioproducts, agroforestry and phytoremediation. Biomass and Bioenergy 2006, 30, (8-9), 715-727. [CrossRef]

- Weih, M.; Nordh, N.-E., Characterising willows for biomass and phytoremediation: growth, nitrogen and water use of 14 willow clones under different irrigation and fertilisation regimes. Biomass and Bioenergy 2002, 23, (6), 397-413. [CrossRef]

- Wani, K. A.; Sofi, Z. M.; Malik, J. A.; Wani, J. A., Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals Using Salix (Willows). In Bioremediation and Biotechnology, Vol 2, 2020; pp 161-174.

- Lewandowski, I.; Schmidt, U.; Londo, M.; Faaij, A., The economic value of the phytoremediation function – Assessed by the example of cadmium remediation by willow (Salix ssp). Agricultural Systems 2006, 89, (1), 68-89. [CrossRef]

- Gervais-Bergeron, B.; Chagnon, P.-L.; Labrecque, M., Willow Aboveground and Belowground Traits Can Predict Phytoremediation Services. Plants 2021, 10, (9). [CrossRef]

- Fortin Faubert, M.; Desjardins, D.; Hijri, M.; Labrecque, M., Willows Used for Phytoremediation Increased Organic Contaminant Concentrations in Soil Surface. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, (7). [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, K.; Kasım, G. Ç., Phytoremediation potential of poplar and willow species in small scale constructed wetland for boron removal. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 722-736. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Weyens, N.; Croes, S.; Beckers, B.; Meiresonne, L.; Van Peteghem, P.; Carleer, R.; Vangronsveld, J., Phytoremediation of Metal Contaminated Soil Using Willow: Exploiting Plant-Associated Bacteria to Improve Biomass Production and Metal Uptake. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2015, 17, (11), 1123-1136. [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, M.; Hu, Y.; Vincent, G.; Shang, K., The use of willow microcuttings for phytoremediation in a copper, zinc and lead contaminated field trial in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2020, 22, (13), 1331-1337. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Du, W.; Ai, F.; Yin, Y.; Ji, R.; Guo, H., Microbial communities in the rhizosphere of different willow genotypes affect phytoremediation potential in Cd contaminated soil. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 769. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Ge, J.; Lu, L.; Xie, R.; Tian, S., Novel plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SaRB5, facilitate phytoremediation by plant growth and cadmium absorption in Salix suchowensis. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025, 303. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Xu, K.; Lu, L.; Shu, Q.-y.; Tian, S., The endophytic fungus Serendipita indica reshapes rhizosphere soil microbiota to improve Salix suchowensis growth and phytoremediation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 495. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y.; Kwak, K.-H.; Ryu, Y.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Baik, J.-J., Impacts of biogenic isoprene emission on ozone air quality in the Seoul metropolitan area. Atmospheric Environment 2014, 96, 209-219. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Lun, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, B., Biogenic volatile organic compounds in forest therapy base: A source of air pollutants or a healthcare function? Science of The Total Environment 2024, 931, 172944. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Peng, W., Molecular characteristics of volatile components from willow bark. Journal of King Saud University-Science 2020, 32, (3), 1932-1936. [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Barbieri, G.; Valussi, M.; Maggini, V.; Firenzuoli, F., Forest Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Effects on Human Health: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, (18), 6506. [CrossRef]

- Mozaffar, M. A., Biogenic volatile organic compound emissions from Willow trees. Student thesis series INES 2013.

- Tun, K. M.; Minor, M.; Jones, T.; McCormick, A. C., Volatile Profiling of Fifteen Willow Species and Hybrids and Their Responses to Giant Willow Aphid Infestation. Agronomy 2020, 10, (9), 1404. [CrossRef]

- Shaoning, L.; Tingting, L.; Xueying, T.; Na, Z.; Xiaotian, X.; Shaowei, L., Comparative Study on the Release of Beneficial Volatile Organic Compounds from Four Deciduous Tree Species. Ecology and Environment 2023, 32, (1), 123.

- Karlsson, T.; Klemedtsson, L.; Rinnan, R.; Holst, T., Leaf-Scale Study of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Willow (Salix spp.) Short Rotation Coppices Covering Two Growing Seasons. Atmosphere 2021, 12, (11). [CrossRef]

- Scala, A.; Allmann, S.; Mirabella, R.; Haring, M. A.; Schuurink, R. C., Green leaf volatiles: a plant’s multifunctional weapon against herbivores and pathogens. International journal of molecular sciences 2013, 14, (9), 17781-17811. [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J., Green Leaf volatiles: a New Player in the Protection against Abiotic stresses? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, (17), 9471. [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J. In Green leaf volatiles: airborne signals that protect against biotic and abiotic stresses, Biology and Life Sciences Forum, 2020; MDPI: p 101.

- Karlsson, T.; Rinnan, R.; Holst, T., Variability of BVOC Emissions from Commercially Used Willow (Salix spp.) Varieties. Atmosphere 2020, 11, (4). [CrossRef]

- Swanson, L.; Li, T.; Rinnan, R., Contrasting responses of major and minor volatile compounds to warming and gall-infestation in the Arctic willow Salix myrsinites. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 793. [CrossRef]

- Mezzomo, P.; Leong, J. V.; Vodrážka, P.; Moos, M.; Jorge, L. R.; Volfová, T.; Michálek, J.; de L. Ferreira, P.; Kozel, P.; Sedio, B. E.; Volf, M., Variation in induced responses in volatile and non-volatile metabolites among six willow species: Do willow species share responses to herbivory? Phytochemistry 2024, 226. [CrossRef]

- Toome, M.; Randjärv, P.; Copolovici, L.; Niinemets, Ü.; Heinsoo, K.; Luik, A.; Noe, S. M., Leaf rust induced volatile organic compounds signalling in willow during the infection. Planta 2010, 232, (1), 235-243. [CrossRef]

- Hakola, H.; Rinne, J.; Laurila, T., The hydrocarbon emission rates of tea-leafed willow (Salix phylicifolia), silver birch (Betula pendula) and European aspen (Populus tremula). Atmospheric Environment 1998, 32, (10), 1825-1833. [CrossRef]

- Füssel, U. Floral scent in Salix L. and the role of olfactory and visual cues for pollinator attraction of Salix caprea L. 2007.

- Ling, J.; Li, X.; Yang, G.; Yin, T., Volatile metabolites of willows determining host discrimination by adult Plagiodera versicolora. Journal of Forestry Research 2021, 33, (2), 679-687. [CrossRef]

- Braccini, C. L.; Vega, A. S.; Coll Aráoz, M. V.; Teal, P. E.; Cerrillo, T.; Zavala, J. A.; Fernandez, P. C., Both Volatiles and Cuticular Plant Compounds Determine Oviposition of the Willow Sawfly Nematus oligospilus on Leaves of Salix spp. (Salicaceae). Journal of Chemical Ecology 2015, 41, (11), 985-996. [CrossRef]

- Galotta, M. P.; Omacini, M.; Fernández, P. C., Symbiosis with Mycorrhizal Fungi Alters Sesquiterpene but not Monoterpene Profile in the South American Willow Salix humboldtiana. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2025, 51, (4). [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. C.; Drewer, J.; Heal, M. R., A comparison of isoprene and monoterpene emission rates from the perennial bioenergy crops short-rotation coppice willow and Miscanthus and the annual arable crops wheat and oilseed rape. GCB Bioenergy 2015, 8, (1), 211-225. [CrossRef]

- Fakhrzad, F.; Jowkar, A., Water stress and increased ploidy level enhance antioxidant enzymes, phytohormones, phytochemicals and polyphenol accumulation of tetraploid induced wallflower. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 206. [CrossRef]

- Gilhen-Baker, M.; Roviello, V.; Beresford-Kroeger, D.; Roviello, G. N., Old growth forests and large old trees as critical organisms connecting ecosystems and human health. A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022, 20, (2), 1529-1538. [CrossRef]

- Roviello, V.; Gilhen-Baker, M.; Roviello, G. N.; Lichtfouse, E., River therapy. Environmental chemistry letters 2022, 20, (5), 2729-2734. [CrossRef]

- Roviello, V.; Roviello, G. N., Less COVID-19 deaths in southern and insular Italy explained by forest bathing, Mediterranean environment, and antiviral plant volatile organic compounds. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022, 20, (1), 7-17. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environmental health and preventive medicine 2010, 15, (1), 9-17. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, É. R.; Maia, J. G. S.; Fontes-Júnior, E. A.; do Socorro Ferraz Maia, C., Linalool as a therapeutic and medicinal tool in depression treatment: a review. Current Neuropharmacology 2022, 20, (6), 1073-1092. [CrossRef]

- Alkanat, M.; Alkanat, H. Ö., D-Limonene reduces depression-like behaviour and enhances learning and memory through an anti-neuroinflammatory mechanism in male rats subjected to chronic restraint stress. European Journal of Neuroscience 2024, 60, (4), 4491-4502. [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, B.; Natale, F.; Rinaudo, M.; Sollazzo, R.; Spinelli, M.; Fusco, S.; Grassi, C., Olfactory stimulation with multiple odorants prevents stress-induced cognitive and psychological alterations. Brain Communications 2024, 6, (6), fcae390. [CrossRef]

- Linck, V. d. M.; da Silva, A. L.; Figueiró, M.; Caramao, E. B.; Moreno, P. R. H.; Elisabetsky, E., Effects of inhaled Linalool in anxiety, social interaction and aggressive behavior in mice. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, (8-9), 679-683. [CrossRef]

- d'Alessio, P. A.; Bisson, J.-F.; Béné, M. C., Anti-stress effects of d-limonene and its metabolite perillyl alcohol. Rejuvenation research 2014, 17, (2), 145-149. [CrossRef]

- Amenduni, A.; Massari, F.; Palmisani, J.; de Gennaro, G.; Brattoli, M.; Tutino, M., CHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF ODOR ACTIVE VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUNDS EMITTED FROM PERFUMES BY GC/MS-O. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal (EEMJ) 2016, 15, (9). [CrossRef]

- Pino, J. A.; Trujillo, R., Characterization of odour-active compounds of sour guava (Psidium acidum [DC.] Landrum) fruit by gas chromatography-olfactometry and odour activity value. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2021, 36, (2), 207-212. [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S. S.; Tabana, Y. M.; Ahamed, M. K.; Majid, A. A., In vivo anti-inflammatory activity of β-caryophyllene, evaluated by molecular imaging. Molecules & Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 1, (e1001), 6p. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, K.; Zalaghi, M.; Shehnizad, E. G.; Salari, G.; Baghdezfoli, F.; Ebrahimifar, A., The effects of alpha-pinene on inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in the formalin test. Brain research bulletin 2023, 203, 110774. [CrossRef]

- Ozah, E. O.; Ben-Azu, B.; Chimezie, J.; Friday, F. B.; Esuku, D. T.; Chijioke, B. S.; Iwhiwhu, P.; Moses, A. S.; Nekabari, M. K.; Oyovwi, O. M., Sabinene confers protection against cerebral ischemia in rats: potential roles of antioxidants, anti-inflammatory effects, and astrocyte-neurotrophic support. Neurological Research 2025, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Bilbrey, J. A.; Ortiz, Y. T.; Felix, J. S.; McMahon, L. R.; Wilkerson, J. L., Evaluation of the terpenes β-caryophyllene, α-terpineol, and γ-terpinene in the mouse chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain: Possible cannabinoid receptor involvement. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, (5), 1475-1486. [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, M.; Steuer, C., α-Pinene: A never-ending story. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112857.

- Park, B.-I.; Kim, B.-S.; Kim, K.-J.; You, Y.-O., Sabinene suppresses growth, biofilm formation, and adhesion of Streptococcus mutans by inhibiting cariogenic virulence factors. Journal of Oral Microbiology 2019, 11, (1), 1632101. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, A., Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii): The New" King of the Conifer Oils"? International Journal of Professional Holistic Aromatherapy 2025, 14, (2).

- Ambroziak, T., The Tipsiness of Black Spruce. Aromatherapy Journal 2020.

- Kanezaki, M.; Terada, K.; Ebihara, S., Effect of olfactory stimulation by L-menthol on laboratory-induced dyspnea in COPD. Chest 2020, 157, (6), 1455-1465. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R., Menthol: effects on nasal sensation of airflow and the drive to breathe. Current allergy and asthma reports 2003, 3, (3), 210-214. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, I.; Modaresi, M.; Cheshmekaboodi, F.; Miraghaee, S. S., The Effects of Aromatic Water of Salix aegyptiaca L. and its Major Component, 1, 4-Dimethoxybenzene, on Lipid and Lipoprotein Profiles and Ethology of Normolipidemic Rabbits. Int. J. Clin. Toxicol 2015, 2, 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Dacho, V.; Szolcsányi, P., Synthesis and olfactory properties of seco-analogues of lilac aldehydes. Molecules 2021, 26, (23), 7086. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Sowndhararajan, K.; Choi, H. J.; Park, S. J.; Kim, S., Olfactory stimulation effect of aldehydes, nonanal, and decanal on the human electroencephalographic activity, according to nostril variation. Biomedicines 2019, 7, (3), 57. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A. S.; Sood, A.; Vellapandian, C., The Role of Ocimene in Decreasing α-Synuclein Aggregation using Rotenone-induced Rat Model. Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal ChemistryChemistry-Central Nervous System Agents) 2024, 24, (3), 304-316. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, B.; Kötter, I.; Heide, L., Pharmacokinetics of salicin after oral administration of a standardised willow bark extract. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2001, 57, (5), 387-391. [CrossRef]

- Nahrstedt, A.; Schmidt, M.; Jäggi, R.; Metz, J.; Khayyal, M. T., Willow bark extract: the contribution of polyphenols to the overall effect. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 2007, 157, (13), 348-351. [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, J. G., Medicinal potential of willow: A chemical perspective of aspirin discovery. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2010, 14, (3), 317-322. [CrossRef]

- Oketch-Rabah, H. A.; Marles, R. J.; Jordan, S. A.; Low Dog, T., United States Pharmacopeia Safety Review of Willow Bark. Planta Medica 2019, 85, (16), 1192-1202. [CrossRef]

- Tawfeek, N.; Mahmoud, M. F.; Hamdan, D. I.; Sobeh, M.; Farrag, N.; Wink, M.; El-Shazly, A. M., Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Medicinal Uses of Plants of the Genus Salix: An Updated Review. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Maistro, E. L.; Terrazzas, P. M.; Perazzo, F. F.; Gaivão, I. O. N. D. M.; Sawaya, A. C. H. F.; Rosa, P. C. P., Salix alba (white willow) medicinal plant presents genotoxic effects in human cultured leukocytes. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 2020, 82, (23-24), 1223-1234. [CrossRef]

- Warmiński, K.; Stolarski, M. J.; Gil, Ł.; Krzyżaniak, M., Willow bark and wood as a source of bioactive compounds and bioenergy feedstock. Industrial Crops and Products 2021, 171. [CrossRef]

- Romesberg, F.; El-Shemy, H. A.; Aboul-Enein, A. M.; Aboul-Enein, K. M.; Fujita, K., Willow Leaves' Extracts Contain Anti-Tumor Agents Effective against Three Cell Types. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, (1). [CrossRef]

- Gaffin, S. R.; Rosenzweig, C.; Kong, A. Y., Adapting to climate change through urban green infrastructure. Nature Climate Change 2012, 2, (10), 704-704. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, E.; Comín, F. A., Urban green infrastructure and sustainable development: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, (20), 11498. [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, L.; Gentile, A.; Tangredi, D. N.; Piccolo, P.; Oliva, G.; Vigliotta, G.; Cicatelli, A.; Guarino, F.; Guidi Nissim, W.; Labra, M.; Castiglione, S., Urban Phytoremediation: A Nature-Based Solution for Environmental Reclamation and Sustainability. Plants 2025, 14, (13), 2057. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. J.; Xie, Z., Therapeutic plant landscape design of urban forest parks based on the Five Senses Theory: A case study of Stanley Park in Canada. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks 2022, 10, (1), 97-112. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qi, X., Protest response and contingent valuation of an urban forest park in Fuzhou City, China. Urban forestry & urban greening 2018, 29, 68-76. [CrossRef]

- Volenec, Z. M.; Abraham, J. O.; Becker, A. D.; Dobson, A. P., Public parks and the pandemic: How park usage has been affected by COVID-19 policies. PloS one 2021, 16, (5), e0251799. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, C.; Vannini, A.; Scanu, B.; González-Moreno, P.; Turco, S.; Drais, M. I.; Brandano, A.; Varo Martínez, M. Á.; Mazzaglia, A.; Deidda, A., Challenges to Mediterranean Fagaceae ecosystems affected by Phytophthora cinnamomi and climate change: Integrated pest management perspectives. Current Forestry Reports 2025, 11, (1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Kröel-Dulay, G.; Ransijn, J.; Schmidt, I. K.; Beier, C.; De Angelis, P.; De Dato, G.; Dukes, J. S.; Emmett, B.; Estiarte, M.; Garadnai, J., Increased sensitivity to climate change in disturbed ecosystems. Nature communications 2015, 6, (1), 6682. [CrossRef]

- Bressler, A.; Vidon, P.; Hirsch, P.; Volk, T., Valuation of ecosystem services of commercial shrub willow (Salix spp.) woody biomass crops. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2017, 189, (4), 137. [CrossRef]

- Rousset, J.; Menoli, S.; François, A.; Gaucherand, S.; Evette, A., Developing Nature-based Solutions in the Alps: an Ex-situ Experiment to Select Willows for Subalpine Soil and Water Bioengineering Structures. Environmental Management 2025, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Weih, M., Genetic and environmental variation in spring and autumn phenology of biomass willows (Salix spp.): effects on shoot growth and nitrogen economy. Tree physiology 2009, 29, (12), 1479-1490. [CrossRef]

- Read, P.; Garton, S.; Tormala, T., Willows (Salix spp.). In Trees II, Springer: 1989; pp 370-386.

| Compound | Salix species | Reference | Beneficial effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprene | Salix viminalis, Salix myrsinites | Karlsson et al. 2021, Swanson et al. 2021 | — | — |

| β-caryophyllene | Salix viminalis, Salix nigra | Karlsson et al. 2021, Braccini et al. 2015 | Anti-inflammatory, anxiolytic, immune-modulating | Dahham et al. 2015, Bilbrey et al. 2022 |

| Ocimene (cis- and trans-) | Salix viminalis, Salix nigra | Karlsson et al. 2021, Braccini et al. 2015 | Pleasant scent, neuroprotective | Suresh, Sood and Vellapandian 2024 |

| α-farnesene | Salix spp. | Karlsson et al. 2021 | — | — |

| Hexanal | Salix viminalis | Toome et al. 2010 | Calming scent, stress reduction | Pino and Trujillo 2021 |

| Nonanal | Salix babylonica | Shaoning et al. 2023 | — | — |

| Linalool | Salix viminalis | Karlsson et al. 2021 | Sedative, anxiolytic, mood-enhancing | dos Santos et al. 2022, Linck et al. 2010 |

| (E)-4,8-dimethyl-1,3,7-nonatriene | Salix myrsinites | Swanson et al. 2021 | — | — |

| α-pinene | Salix cinerea, Salix spp. | Mezzomo et al. 2024, Morrison et al. 2015 | Anti-inflammatory, bronchodilatory, cognitive support | Rahimi et al. 2023, Allenspach and Steuer 2021, Gardiner 2025 |

| Delta-3-carene | Salix spp. | Morrison et al. 2015 | — | — |

| β-pinene | Salix spp. | Morrison et al. 2015 | — | — |

| Limonene | Salix phylicifolia, Salix spp. | Hakola et al. 1998, Morrison et al. 2015 | Antidepressant, stress reduction | Alkanat and Alkanat 2024, d'Alessio et al. 2014 |

| Sabinene | Salix phylicifolia | Hakola et al. 1998 | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | Ozah et al. 2025, Park et al. 2019 |

| Camphene | Salix phylicifolia | Hakola et al. 1998 | Respiratory stimulant, antimicrobial | Ambroziak 2020 |

| 1,4-dimethoxybenzene | Salix caprea, Salix atrocinerea | Füssel 2007 | Floral scent, mood-enhancing | Karimi et al. 2015 |

| Lilac aldehyde | Salix caprea, Salix atrocinerea | Füssel 2007 | Floral aroma, calming effect | Dacho and Szolcsányi 2021 |

| Decanal | Salix babylonica, Salix nigra | Shaoning et al. 2023, Braccini et al. 2015 | Soothing scent, insect-repellent | Kim et al. 2019 |

| Undecane | Salix nigra | Braccini et al. 2015 | — | — |

| Cis-3-hexenyl acetate | Salix suchowensis | Ling et al. 2021 | Calming, masking other scents | Pino and Trujillo 2021 |

| Cis-3-hexen-1-ol | Salix babylonica | Shaoning et al. 2023 | Fresh green aroma, stress reduction | Bandiera et al. 2024 |

| L-menthol | Salix babylonica | Shaoning et al. 2023 | Cooling, analgesic, respiratory relief | Kanezaki et al. 2020, Eccles 2003 |

| Azulene (chamomile blue) | Salix babylonica | Shaoning et al. 2023 | Anti-inflammatory, calming | Ozah et al. 2025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).