Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

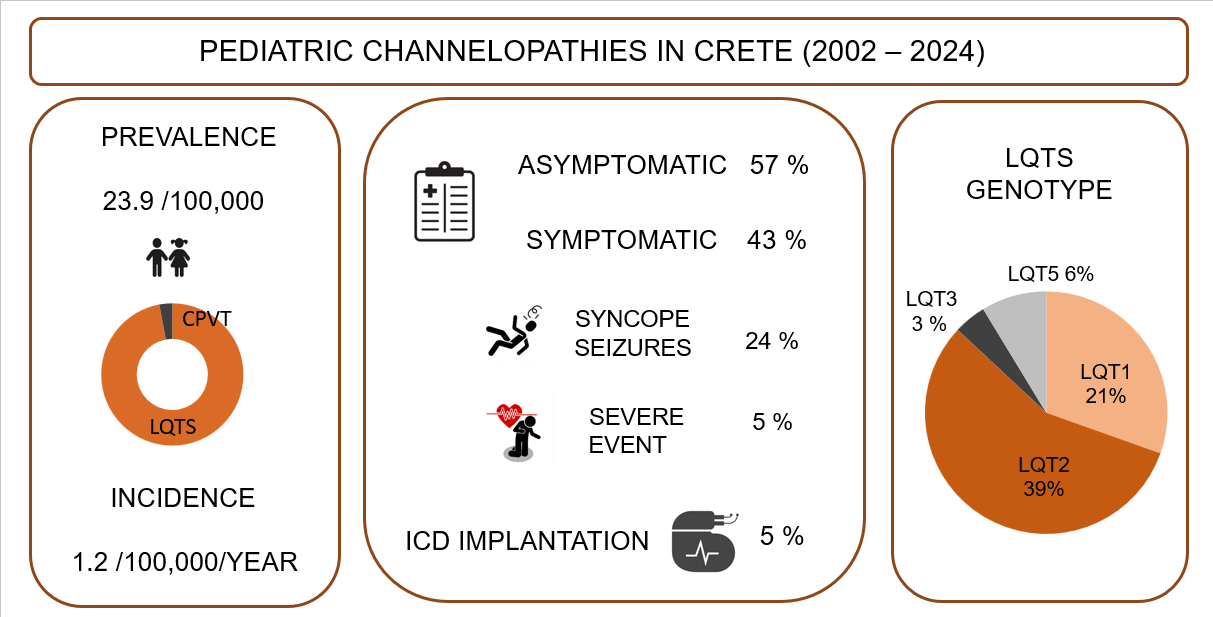

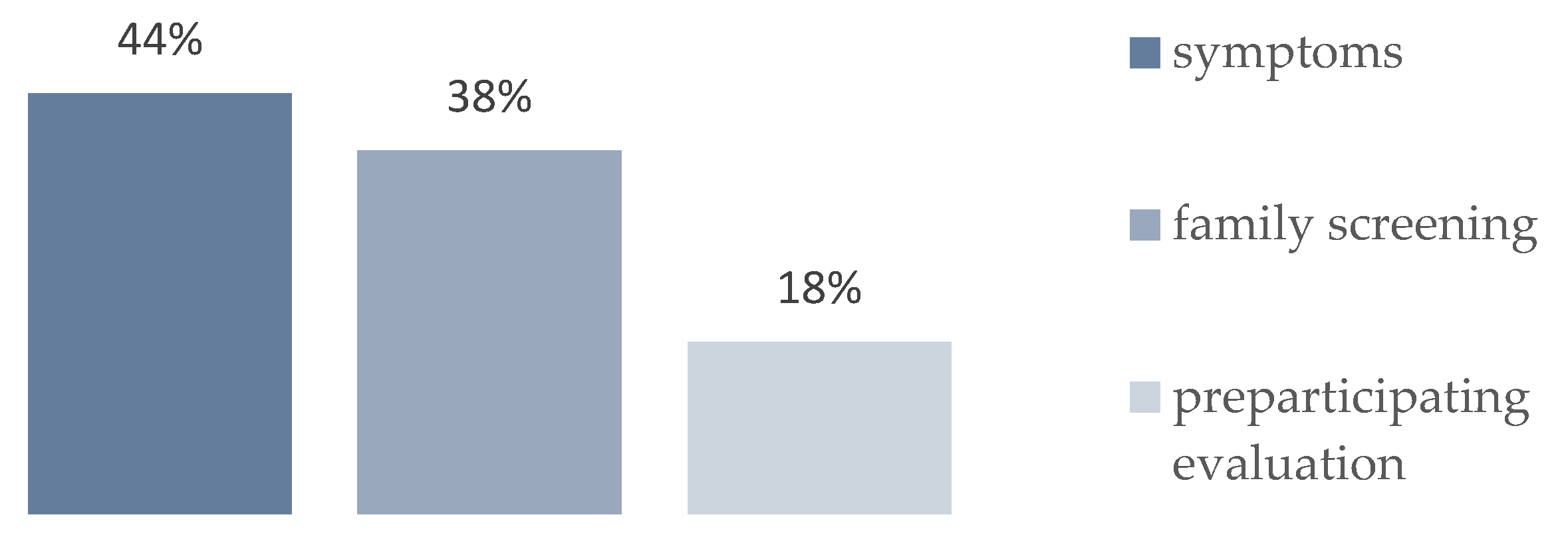

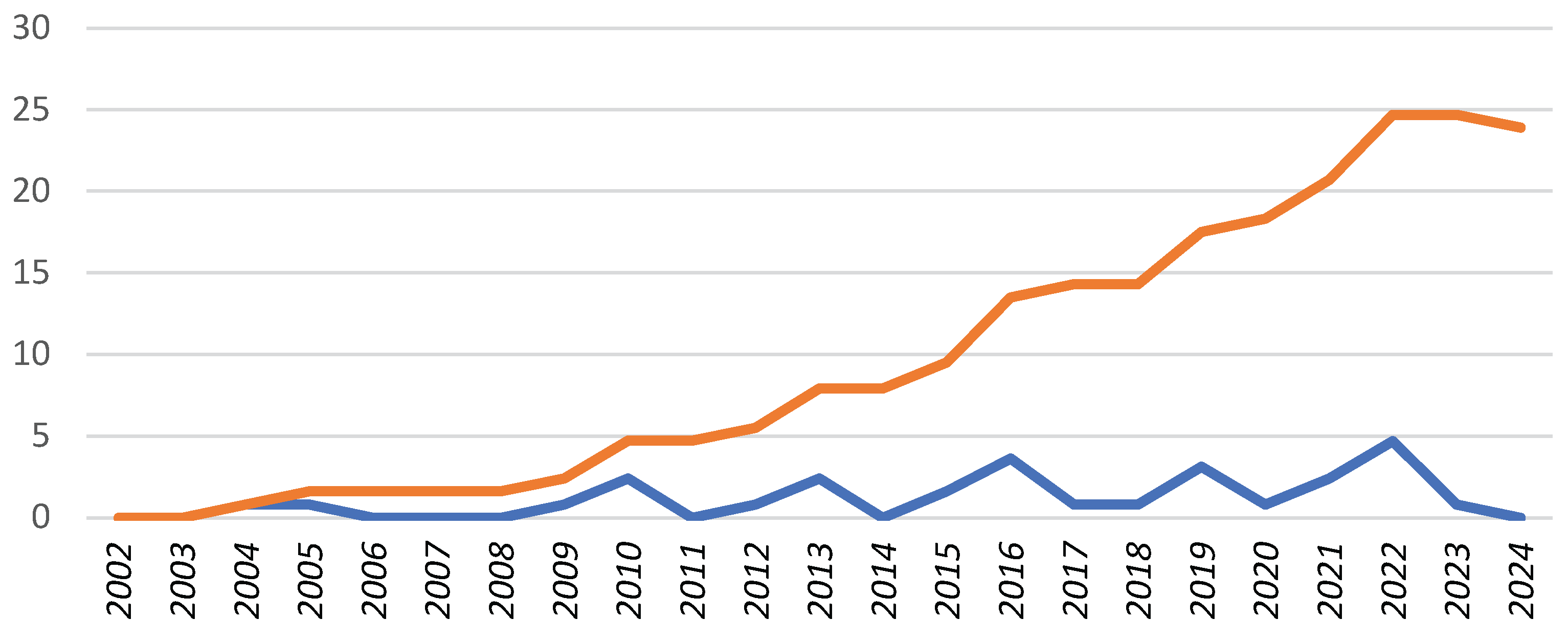

Background: Channelopathies represent a heterogeneous group of rare inherited cardiac diseases associated with life-threatening arrhythmias. Our knowledge of their epidemiology in childhood is limited. The aim of this study is to evaluate the epidemiology of pediatric channelopathies on a Mediterranean island (Crete, Greece). Methods: Retrospective study of children < 18 years followed in the Regional Tertiary Pediatric Cardiology Unit during a 23-year period (2002-2024) and meeting the disease-specific diagnostic criteria. Results: A total of 34 children (27 families) were enrolled, corresponding to an average annual incidence of 1.2 (95% C.I.: 0.8 – 1.6) and a cumulative prevalence of 23.9 (95% C.I.: 16.1 – 34.1) cases per 100, 000 children, with significant though regional incidence differences. Long QT syndrome (n=33) was predominant, with a single exception of catecholaminergic polymorphic tachycardia. Diagnosis was based on symptomatic presentation (n=15, 44 %), preparticipation screening (n=6, 18%) or affected family cascade screening (n=13, 38%). They represented the first diagnosis within affected families (index cases) in 20/34 (58%) of cases. Genetic testing was performed in 27/34 (79%) channelopathy cases and it was positive in a single case of CPVT and in 23 out of 27 (89%) LQT cases in which it was performed, with a genotype of LQT2 in 13 (39%), LQT1 in 7 (21%), LQT3 in 1 (3%) and LQT5 in 2 (6%) cases. Conclusion: The incidence of pediatric channelopathies on the Mediterranean island of Crete was comparable to that reported in the literature, with regional though clusters of significant increased incidence. Further study of the epidemiology of pediatric channelopathies is needed, to document any regional or ethnic differences and for the best design of large-scale screening programs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population

Data Collection

Epidemiologic Data

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schwartz PJ, Crotti L. Ion channel diseases in children: manifestations and management. Curr Opin Cardiol 2008 May;23(3):184-91. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3282fcc2e3.

- Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, Pedrazzini M, Besana A, Bosi A et al. Prevalence of the congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation 2009;120: 1761–1767.

- Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ, Antzelevitch C, Bezzina CR, Borggrefe M, Cuneo BF, Wilde AAM. Inherited cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6(1):58.

- Offerhaus JA, Bezzina CR, Wilde AAM. Epidemiology of inherited arrhythmias Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17(4):205-215.

- Skinner JR, Winbo A, Abrams D, Vohra J, Wilde AA. Channelopathies that lead to Sudden Cardiac Death: Clinical and Genetic Aspects. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2018; 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2018.09.007.

- Bagnall RD, Weintraub RG, Ingles J, Duflou J, Yeates L, Lam L et al. A prospective study of sudden cardiac death among children and young adults N Engl J Med. 2016 23;374(25):2441-52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510687.

- Schwartz PJ, Crotti L, Insolia R. Long QT Syndrome: From genetics to management. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 August 1; 5(4): 868–877. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962019.

- Hazle MA, Shellhaas RA, Bradley DJ, Macdonald Dick 2nd, Lapage MJ. Arrhythmogenic channelopathy syndromes presenting as refractory epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol 2013 Aug;49(2):134-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.03.017.

- Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Giudicessi JR, Tester DJ, Crotti L, Ackermann MJ. Cardiac Channelopathies and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome I. Gussak, C. Antzelevitch (eds.), Electrical Diseases of the Heart, 381DOI 10.1007/978-1-4471-4978-1_24, © Springer-Verlag London 2013.

- Yoshinaga M, Kucho Y, Nishibatake M, Ogata H, Nomura Y. Probability of diagnosing long QT syndrome in children and adolescents according to the criteria of the HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:2490–2497.

- Oe H, Takagi M, Tanaka A, Namba M, Nishiboro Y, Nishida Y et al. Prevalence and clinical course of the juveniles with Brugada-type ECG in Japanese population. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2005;28:549–54.

- Drineas P, Tsetsos F, Plantinga A, Lazaridis I, Yannaki E, Razou A et al. Genetic history of the population of Crete. Ann Hum Gen 2019; 83:373-388.

- Bagkaki A, Parthenakis F, Chlouverakis G, Anastasakis A, Papagiannis I, Galanakis E, Germanakis, I. Epidemiology of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy in a Mediterranean Population. Children2024;11: 732.

- Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Gregers Winkel B, Behr ER, Blom NA et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death Developed by the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). European Heart Journal2022; 43, 3997–4126. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262.

- Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Europace. 2015 Nov;17(11):1601-87.

- Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ, George AL Jr, Wilde AAM. Impact of genetics on the clinical management of channelopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.044.

- Adler A, Novelli V, Amin AS, Abiusi E, Care M, Nannenberg EA et al. An International, Multicentered, Evidence-Based Reappraisal of Genes Reported to Cause Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Circulation. 2020;141:418–428.

- 18. [CrossRef]

- Wilde AAM, Semsarian C, Marquez MF, Sepehri Shamloo A, Ackerman MJ, Ashley EA et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/LAHRS Expert Consensus Statement on the State of Genetic Testing for Cardiac Diseases. Heart Rhythm 2022;19(7):e4-e49.

- Hellenic Statistical Authority Greece population data. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/el/statistics/-/publication/SPO18 (Accessed 23/9/2025).

- Med Calc. Easy to use statistical software. Available at https://www.medcalc.org/calc/rate_comparison.php (Accessed 2/9 2025).

- QT drugs lists. Available online: https://crediblemeds.org/ (Accessed 23/9/2025).

- Pelliccia A, Sharma S, Gati S, Back M, Borjensson M, Caselli S et al.2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease: The Task Force on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal, 2021; 42(1):17–96,.

- Bagkaki A, Tsoutsinos A, Hatzidaki E, Tzatzarakis M, Parthenakis F, Germanakis I. Mexiletine Treatment for Neonatal LQT3 Syndrome: Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Pediatr.2021;9:674041. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.674041.

- Gonzalez Corcia MC, de Asmundis C, Chierchia GB, Brugada P. Brugada syndrome in the paediatric population: a comprehensive approach to clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Cardiology in the Young 2016; 1- 12.

- Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Vacanti G, Monteforte N, Bloise R, Marino M et al. et al. Interplay Between Genetic Substrate, QTc Duration, and Arrhythmia Risk in Patients with Long QT Syndrome, J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1663–71.

- Sieira J, Brugada P. Brugada syndrome: defining the risk in asymptomatic patients. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2016;5:164–169.

- Nosetti L, Zaffanello M, Lombardi C, Gerosa A, Piacentini G, Abramo M et al. Early Screening for Long QT Syndrome and Cardiac Anomalies in Infants: A Comprehensive Study. Clin. Pract. 2024;14:1038–1053.

- Yoshinaga M, Ushinohama H, Sato S, Tauchi N, Horigome H, Takahashi H et al. Electrocardiographic screening of 1-month-old infants for identifying prolonged QT intervals. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6:932–938.

- Simma A, Potapow A, Brandstetter S, Michel H, Melter M, Seelbach-Göbelb B et al. Electrocardiographic Screening in the First Days of Life for Diagnosing Long QT Syndrome: Findings from a Birth Cohort Study in Germany. Neonatology2020;117:756–763.],.

- Hayashi K, Fujino N, Uchiyama K, Ino H, Sakata K, Konno Teta l. Long QT syndrome and associated gene mutation carriers in Japanese children: results from ECG screening examinations Clinical Science (2009) 117, 415–424.

- Vink AS, Clur SB, Wilde AAM, Blom NA. Effect of age and gender on the QTc-interval in healthy individuals and patients with long-QT syndrome. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018; 28:64–75.

- Wilde AA, Moss AJ, Kaufman ES, Shimizu W, Peterson DR, Benhorin J et al. Clinical aspects of type 3 long QT syndrome. An international multicenter study.Circulation.2016;134:872-882.

- Horigome H, Nagashima M, Sumitomo N, Yoshinaga M, Ushinohama H, Iwamoto M et al. Clinical Characteristics and Genetic Background of Congenital Long-QT Syndrome Diagnosed in Fetal, Neonatal, and Infantile Life. A Nationwide Questionnaire Survey in Japan. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:10-17.

- Schwartz PJ, Garson AJr, Paul T, Stramba-Badiale M, Vetter VL, Villain E et al. Guidelines for the interpretation of the neonatal electrocardiogram. A Task Force for the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J.2002;23:1329-1344.

- Sarquella-Brugada G, Cesar S, Zambrano MD, Fernandez-Falgueras A, Fiol V, Iglesias A et al. Electrocardiographic Assessment and Genetic Analysis in Neonates: A Current Topic of Discussion. Current Cardiology Reviews.2019;15: 30-37.].

- Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Orav EJ, Cox GF et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1647–1655.].

- Nugent AW, Daubeney PE, Chondros P, Carlin JB, Cheung M, Wilkinson LC et al. The epidemiology of childhood cardiomyopathy in Australia. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1639–1646].

- Baban A, Lodato V, Parlapiano G, di Mambro C, Adorisio R, Bertini ES et al. Myocardial and Arrhythmic Spectrum of Neuromuscular Disorders in Children. Biomolecules 2021;11: 1578.].

- Lodato V, Parlapiano G, Cal F, Silvetti MS, Adorisio R, Armando M et al. Cardiomyopathies in children and systemic disorders when is it useful to look beyond the heart? J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022;9: 47.].

- Bidzimou MTK, Landstrom AP. From diagnostic testing to precision medicine: the evolving role of genomics in cardiac channelopathies and cardiomyopathies in children. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2022;76:101978.],.

- Rivolta I, Abriel H, Tateyama M, Liu H, Memmi M, Vardas P et al. Brugada and Long QT-3 Syndrome Mutations of a Single Residue of the Cardiac Sodium Channel Confer Distinct Channel and Clinical Phenotypes. Journal of biological chemistry 2001; 276 (33):30623–30630.].

- Theilade J, Kanters J, Henriksen FL, Gilsa-Hansen M, Svendsen JH, Eschen O, et al. Cascade Screening in Families with Inherited Cardiac Diseases Driven by Cardiologists: Feasibility and Nationwide Outcome in Long QT Syndrome. Cardiology2013;126:131–13].

- Graziano F, Schiavon M, Cipriani A, Savalla F, De Gaspari M, Bauce B et al. Causes of sudden cardiac arrest and death and the diagnostic yield of sport preparticipation screening in children. BrJSportsMed2024;58:255–260.

- Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ, George Jr AL, Wilde AAM. Impact of Genetics on the Clinical Management of Channelopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62(3): 169–180.],.

- Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: a transatlantic clinical approach to diagnosis and therapy. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34, 3109-3116.],.

- Roston TM, Yuchi Z, Kannankeril PJ, Hathaway J, Vinocur JM, Etheridge SP, et al. The clinical and genetic spectrum of catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia: findings from an international multicenter registry. Europace 2018;20:541-547].

- Monasky MM, Micaglio E, Ciconte G, Pappone C., Brugada Syndrome: Oligogenic or Mendelian Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020; 21: 1687.

- Campuzano O, Sarquella-Brugada G, Fernandez-Falgueras A, Cessar S, Coll M, Mates J et al. Genetic interpretation and clinical translation of minor genes related to Brugada syndrome. Human Mutation 2019; 40:749-764.].

- Kutyifa V, Daimee UA, McNitt S, Polonsky B, Lowenstein C, Cutter K, et al., Clinical aspects of the three major genetic forms of long QT syndrome (LQT1, LQT2, LQT3), Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2018;23:e12537. https://doi.org/10.1111/anec.12537).

- Pflaumer A, Davis AM. An update on the diagnosis and management of catecholamine polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Lung Circ 2019;28:266-9],.

- Brugada J, Campuzano O, Arbelo E, Sarquella-Brugada G, Brugada R. Present status of Brugada Syndrome. JACC State-of-the-Art Review. JACC2018; 72(9): 1046-59.

- Pereira R, Campuzano O, Sarquella-Brugada G, Cesar S, Iglesias A, Brugada J et al. Short QT syndrome in pediatrics. Clin Res Cardiol 2017;106:393–400.

| Diagnostic criteria | |

| Long QT Syndrome |

a) QTc ≥ 480 ms by Bazett’s formula in repeated 12-lead ECG with or without symptoms in the absence of a secondary cause of LQTS b) QTc > 460 in repeated 12-lead ECGs in a patient with unexplained syncope or aborted cardiac arrest in the absence of a secondary cause for QT prolongation. c) LQTS risk score (“Schwartz score”) >3 |

| Brugada Syndrome | ECG: Spontaneous or induced (fever, provocative testing) type 1 (“coved pattern”) is considered as the only diagnostic pattern for BrS regardless the clinical symptoms |

|

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) |

The presence of normal resting ECG in a structurally normal heart and exercise- or emotion-induced bidirectional VT or PVT (polymorphic ventricular tachycardia) |

| Short QT Syndrome |

a)QTc ≤ 360 ms in the presence of a pathogenic mutation and/or a positive family history of SQTS in the absence of secondary causes of SQTS b) SQTS should be considered in the presence of a QTc ≤ 320 m. |

| Cases | Incidence/ 100,000<18Y/Year (95%C.I.) |

Prevalence/ 100,000<18Y (95%C.I.) |

|

| Total | 34 | 1.2 (0.8-1.6) | 23.9 (16.1-34.1) |

| LQTS | 33 | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) | 23.9 (16.1-34.1) |

| CPVT | 1 | 0.03 (0.01-0.2) | 0.8 (0.02-4.4) |

| Schwartz Circulation 2009 [2] |

Nosetti Clinics and Practice 2024 [27] |

Yoshinaga Circ Arrh Electr 2013 [28] |

Simma Neonatology 2020 [29] |

Hayashi Clinical Science 2009 [30] |

Yoshinaga European Heart Journal 2016 [10] |

Crete, Greece 2025 |

|

| Channelopathy | LQTS | LQTS | LQTS | LQTS | LQTS | LQTS | LQTS |

|

Retrospective/Prospective |

Pro | Retro | Pro | Pro | Pro | Pro | Retro |

|

Years (duration) |

5 (2001 –06) | 18 (2001-17) | 2 (2010-11) | 4 (2015-18) | 2 (2004-5) | 6 (2008-13) | 23 (2002-24) |

| Country | Italy |

Italy |

Japan | Germany Regensburg | Japan Kanazawa |

Japan Kagoshima |

Greece Crete |

|

Age of children |

15-25 days | 20-40 days | 4 weeks | 27 days | 6-12 years | 6 years 12 years | 0-18 years |

| Screened population | 44,596 | 2,245 |

4,285 | 2,251 | 7,961 |

33,051 3,751 |

125,300 |

|

Cases |

17 | 27 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 10 (6 Years) 32 (12 Years) |

33 |

|

Prevalence (100,000<18Y) |

38* |

42* |

23.3 |

88* |

37.6 |

30 (6 Y) 93 (12 Years) |

23.9 95% C.I: 16.1 – 34.1 |

| Sex distribution (%) (boys/girls) | 51/49 | 39.9/60.1 | 60/40 | 50.9/49.1 | 50.8/49.2 | 50/50 6 Years 46.8/53.2 12 Years | 41/59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).