1. Introduction

One of the most prevalent strands in the literature on contemporary economic studies concerns the interplay between the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) framework and the evolution of financial systems across countries. The impact of climate transition, institutional upgrading, and social integration paradigms (Bruno & Henisz, 2024) in the face of the mounting pressures for climate transition suggests that the dynamics for credit allocations in the evolving financial regimes in the aftermath of the climate imperatives indicate that the resource allocations in credit terms are no longer governed by the enduring pure economic tenets. However, as opposed to the countervailing forces of ESG (Chodnicka-Jaworska, 2022). Domestic Credit to the Private Sector by Banks (DCB), the index typically used in context to the advancement of the financial system in terms of its forward ability for the generation of economic infrastructure through the enabling power of the credit institutions on the constituents’ behalf, presents an interesting paradigm in the analysis on what the determinants in the context of the contribution by the ESG framework (governance paradigm on the one aspect related to environmental quotient (Evans, Kramer, Lanfranchi, & Brijlal, 2023). This work will make its contribution to the literature by briefly analysing the degree to which ESG issues affect financial development dynamics in various countries through the use of an inter-method analysis approach combining the strengths of econometric model analysis, Machine Learning methods, cluster analysis, and network analysis (Mohapatra, Das, Nayak, Sahoo, & Matta, 2025). Meanwhile, the rising paradigm of sustainable finance in the international context profoundly impacted the dynamics of finance in the environment (You, Chen, Fang, Gao, & Cheng, 2024). Thus, in the new paradigm of finance amid the global shift toward environmentally positive transition, financial institutions must now adapt to climate risks in their operations by factoring environmentally sound factors into loan disbursements (Chen, Lakkanawanit, Suttipun, Swatdikun, & Huang, 2024). Clean energy accessibility, biodiversity depletion, emissions profiles, climate stress measures, natural resource pressures, and the like are among the factors that might influence the future outlook for incentives, constraints, and expectations in the financial market. Social/governance aspects of ESG considerations like the regulation framework of the nation, the level of education in the region, the institutionalization of rights in the social context, and the infrastructure of knowledge might influence the ability of the region towards the maintenance of financial developments within the framework of environmentally sustainable transition processes (Cioli, Giannozzi, Pescatori, & Roggi, 2023). Governance capabilities might influence the stability of financial institutions. Notwithstanding the recent recognition of the linkages between environmental systems and financial regimes, the literature on the topic is scattered in its empirical observations. This is because the current body of research employs the one-dimensional approach to address finance-sustainability linkages, using a conventional econometric framework that lacks the ability to capture the complexity of these relationships (Ding et al. 2024). Additionally, the literature employs a multi-feature framework of the environment because access to green energy sources may increase financial inclusion in some nations. However, the depletion of natural resources within the same nations might reduce credit access within those countries due to climate-related shocks. To explore the linkages in the literature, the research will harness joint ESG determinants of DCB by utilising the approach that combines methodological structures adept at identifying causalities in the context of mapping the structural aspects (Dai et al. 2025). To begin the analysis, the research uses instrumental variable models to address endogeneity in the interaction between financial development and environmental factors. Indicators of the environment, such as access to clean fuels, natural resource depletion, and carbon emissions, could affect one another simultaneously in response to the performance of the economy and the institutions in place. By considering distributional heterogeneity through the First-D Differenced IV estimations, Two-Stage Least Squares analysis, and Random Effects Models for IV analysis, the research accounts for structural heterogeneity. Access to clean fuels is consistently evaluated as a positive determinant of DCB across all model structures. Natural resource depletion adversely affects financial DCB, underscoring the importance of ecological sustainability in the context of the research (You et al., 2024). Emissions in the research act differently according to the models used. In addition to the econometric model, the research uses machine learning capabilities to gain better insight into the importance of the structure in DCB estimation. Among the models used in the analysis, the K-Nearest Neighbours model yields the best results in terms of estimation. KNN achieves near-exact estimation during the validation process (Mohapatra et al., 2025). Compared to other estimation methods, such as regression, K-Neighbours allows better adaptation to local structures in high-dimensional data. K-Neighbours estimation captures the influence of different environmental structures on the credit system in the observation period. The analysis of the importance of the dropout loss function indicates that the primary determinants influencing the estimation of DCB are land-use indicators, climate-related stressors, the pressure of biodiversity loss on the environment, and the economy's emissions intensity (Zioło et al., 2023). Machine learning analysis supports the claim that financial systems are integrated into multivariate environmental regimes. Among the different structures of the observation period, land productivity measures, the significance of ecological conservation measures within the credit system framework, levels of environmental pollutants in the observation period, and the climate within the credit system approach affect the credit allocation mechanism (Bruno & Henisz, 2024). However, the use of clustering algorithms further deepens the analysis by identifying distinct regimes corresponding to different types of financial development. Hierarchical clustering, in particular, stands out as the most accurate approach for grouping countries based on environmental factors. This is according to the Silhouette values, index of separation, and the index of the Dunn method (Ding et al., 2024). The clusters also exhibit some diversity in terms of natural environmental features, in that some countries are in a single large pool that does not closely represent the average environment, while others are in small, distinct clusters that exhibit varying degrees of natural stress. Finally, network analysis reveals the system-level dynamics of the interconnectivity among environmental variables and their structural association with DCB. That the network exhibits low sparsity and high interconnectivity indicates that environmental factors act not independently but rather as part of an integrated system (Dai et al., 2025). Climate-related stress variables, such as high temperatures, emissions indicators, and biodiversity-related measures, play key roles in the network by mediating the interconnectivity between land use patterns, energy access measures, and ecological stress (Chen et al., 2024). By combining diverse empirical methods, the research presents a comprehensive framework for analysing the impact of ESG factors on the evolution of the domestic credit market. Based on the research results, the process of financial development cannot be fully explained without considering the environmental context in which national economies operate (Evans et al., 2023). According to the research results, the course of sustainable financial development should involve implementing comprehensive programs to improve environmental quality, enhance institutional quality, and strengthen social capacity (Cioli et al., 2023). Such comprehensive research on the implementation of the multimethod approach demonstrates that financial development across countries is influenced by diverse environmental factors through various causal relationships (Chodnicka-Jaworska, 2022). Hence, the process of implementing financial policy within the ESG framework requires consideration of the multidimensionality of the impact of the studied variable. This research work makes a contribution to the paradigm shift in the field of financial development in the context of an increasingly specialised world shaped by the logic of sustainable development (You et al., 2024).

2. Literature Review

The selected articles collectively highlight the growing relevance of ESG dimensions in shaping financial systems, yet they differ markedly from the approach adopted in the attached study, both methodologically and conceptually. Many of the papers—such as Abdelfattah et al. (2025) and Adebiyi et al. (2025)—rely heavily on machine learning to identify ESG performance determinants, but they typically focus on firm-level or national sustainability performance rather than on how ESG factors influence financial development itself. In contrast, the attached article adopts a multimethod strategy combining econometrics, KNN-based machine learning, hierarchical clustering, and network analysis to isolate environmental and institutional factors driving Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB), providing a far more granular and systemic analysis. Acharya (2023) and Boström & Hannes (2024) emphasize the broad role of sustainable finance and climate-aligned investment flows but do not empirically model credit allocation. Their analyses remain conceptual, whereas the attached work demonstrates empirically that variables such as clean energy access, resource depletion, and governance significantly shape credit depth. Similarly, Alharbi (2024) and Chernykh et al. (2024) link ESG reforms and financing instruments to macroeconomic performance, yet they do not offer the integrated ESG–credit architecture developed in the attached study. Articles focusing on political stability, financial inclusion, or governance—such as Aich et al. (2025) and Alhassan et al. (2024)—provide important institutional insights but typically examine single channels in isolation. Conversely, the attached article demonstrates through network analysis that credit development is embedded in a dense system of environmental and governance interdependencies, a contribution absent from the compared literature. The review by Capoani (2025) maps ESG applications to territories but lacks causal estimation, while Alvarez-Perez & Fuentes (2024) explore ESG disclosure in debt markets without addressing the structural environmental drivers captured in the attached study. Likewise, Arnone et al. (2024) discuss access to credit within ESG frameworks but do not employ the multimethod triangulation that characterizes the attached work. Del Sarto and Ozili (2025) adopt a bibliometric methodology to map the intellectual structure of FinTech and financial inclusion research, highlighting digitalisation and innovation as drivers of access. Their macro-orientation contrasts with the attached study’s granular modeling of how environmental, social, and governance indicators shape domestic credit to the private sector through econometrics, machine learning, clustering, and network analysis. El Khoury et al. (2023) and Lamanda & Tamásné (2025) examine ESG determinants and disclosure in the banking sector, emphasizing institutional transparency and governance practices. While both stress governance quality as foundational for financial depth, they primarily assess ESG from the viewpoint of banks’ internal practices. The attached study instead models governance as an exogenous structural driver influencing credit allocation across countries, using instrumental variables to isolate causality. Farhoud (2025) foregrounds institutional voids and corporate sustainability in MENA contexts, revealing generational and cultural dynamics often absent from quantitative cross-country ESG analyses. Similarly, Guo & Naseer (2025) highlight financial inclusion, innovation, and development as pathways to ESG readiness, whereas the attached study positions ESG metrics not as outcomes but as determinants of financial development. Hassani et al. (2024) also explore the link between financial development and ESG globally, but focus more on correlation than causal pathways, which the attached work addresses through IV estimation. Studies such as Kandpal et al. (2024), Lotsu (2024), and Malik & Sharma (2025) emphasize sustainable finance instruments and corporate-level ESG impacts. These approaches differ markedly from the attached paper’s system-level modelling of DCB. Meanwhile, Lee et al. (2024) focus on microcredit and poverty alleviation, an angle distant from cross-country credit depth analyses but relevant for understanding the social component of ESG. Finally, McHugh (2023) investigates bankability of SDG projects, engaging with private-sector perceptions, whereas the attached manuscript uses quantitative environmental and governance indicators to trace structural determinants of credit distribution. Together, these contrasts demonstrate how the attached study diverges methodologically and conceptually through its systemic, multimethod, and causally oriented design. Mhlanga and Adegbayibi (2024) focus on Sub-Saharan Africa and emphasise regulatory frameworks, institutional capacity and market infrastructure as preconditions for sustainable finance. Their perspective is largely policy- and practice-oriented and treats financial development as an enabler of ESG, whereas the attached paper inverts the direction and empirically tests whether ESG conditions act as structural determinants of financial development, specifically domestic bank credit. A similar inversion appears in Miletkov and Staneva (2025), who analyse how equity and credit market development affect corporate social responsibility. Financial markets are independent variables, ESG outcomes are dependent; in the attached work, ESG dimensions are the explanatory side and DCB is the outcome. Mohamed’s work on green finance in Egypt and Myronchuk et al. (2024) on financing sustainable development both examine how specific instruments or institutional settings foster green or sustainable finance. They share with the attached study an interest in credit and financial intermediation, but they remain country-specific or conceptual, with no attempt to combine causal identification, machine learning and network approaches across a broad panel of countries. Parish (2025) moves even further into the meso-level, analysing ESG investing and housing financialisation, highlighting the distributive and social consequences of ESG-labelled capital flows. This stands in contrast to the attached paper’s focus on systemic credit depth rather than asset ownership structures. Pineau et al. (2022) are closer in spirit, examining ESG factors in sovereign credit ratings. They show that ESG enters the pricing of sovereign risk; the attached study similarly links ESG to the quantity of domestic private credit rather than its price, and extends the analysis by mapping ESG interdependencies through clustering and network analysis. Rahman et al. (2025) and Rashid and Aftab (2023) work at the micro and meso level (tourism SMEs and microfinance institutions), typically treating financial development as context or moderator for ESG–performance links, again reversing the causal direction explored in the attached work. Schreiner (2024), Shmatov and Castelli (2022), Soares (2024) and Subhani et al. (2025) address international strategies, quantitative techniques and sectoral debt management. They underscore the institutional and methodological evolution of ESG finance, but they do not empirically connect country-level ESG indicators to domestic credit aggregates as systematically as the attached study does through instrumental variables, KNN, hierarchical clustering and network models. Tan (2022) is primarily normative and legal-institutional, framing sustainable development as a problem of regulating private investment for public goods provision. The argument is rich conceptually but largely detached from quantitative evidence; compared to your work, it speaks to the “rules of the game” rather than to measurable ESG drivers of credit aggregates. Varney (2025) and Wang and Zhao (2025) are closer, both centring on how policy innovation and central bank collateral frameworks can accelerate green bond and ESG asset markets in emerging economies and China. Yet they typically treat financial development in terms of specific segments (bond markets, eligible collateral) and do not model domestic credit as a systemic outcome of broader ESG conditions. Trinh and Tran (2025) and Xu et al. (2025) explicitly connect greenhouse gases, banking stability, financial development and renewable energy, moving toward the climate–finance nexus that your paper also engages. However, they focus predominantly on macro stability and growth, whereas your analysis decomposes ESG into a detailed set of environmental and governance indicators and tracks their heterogeneous and nonlinear effects on bank credit using instrumental variables, machine learning and network tools. Several studies shift the lens to micro- and meso-level outcomes. Yang et al. (2025), Zhao, Ngan and Jamil (2025), and Zhao, Gao and Hong (2025) analyse how ESG ratings and uncertainty affect firms’ access to commercial credit and the cost of debt. These contributions are valuable for understanding how ESG is priced at the firm level, but they rely heavily on rating-based proxies and standard econometrics, leaving aside the structural environmental channels and cross-country heterogeneity that your multimethod design addresses. Wei et al. (2024) add a supply-chain dimension, showing ESG “ripple effects” in Chinese industrial networks, again at the meso level. Taušová et al. (2025) and ΜAΓΚOΥΦH’s comparative work on construction firms focus on sectoral sustainability and strategic management. They illustrate how ESG issues materialise in specific industries, but they do not link sectoral patterns back to aggregate domestic credit. Relative to this literature, your study occupies a distinct niche: it treats ESG not as a by-product of financial development or firm strategy, but as a structural, multidimensional determinant of the depth of national credit systems (

Table 1).

3. Environmental Determinants of Domestic Credit: An IV-Based Assessment within the ESG Framework

Analysing the impact of environmental sustainability on the development of the financial system is now the primary concern in the contemporary ESG literature. It is important to note that the interplay between the natural environment and the supply of domestic credit in the economy is complex, as the destruction of the natural environment destabilises the broader economy by eroding institutional confidence in the system’s functioning. At the same time, the success of the transition to environmentally sustainable energy sources significantly improves the financial system by increasing productivity rates, as it positively influences human capital in the system. To accurately assess the impact of primary environmental determinants on the supply of domestic credit in the system (DCB), also known as the level of financial development in the system from the proxy approach used in the analysis, the research model adopts an instrumental variable procedure. Additionally, the primary determinants of the environmental system in the research model comprise access to clean fuels & technologies for cooking (CFC), natural resource depletion (ELE), and CO₂ Emission Per Capita (CO2). Such determinants reflect the complexity of the system’s natural environment, including the potentially influential role of the system’s economic productivity in the atmosphere. Institutions in the system might appear endogenous in the analysis process. Thus, the research uses various institutional indicators to examine investigations (

Table 2).

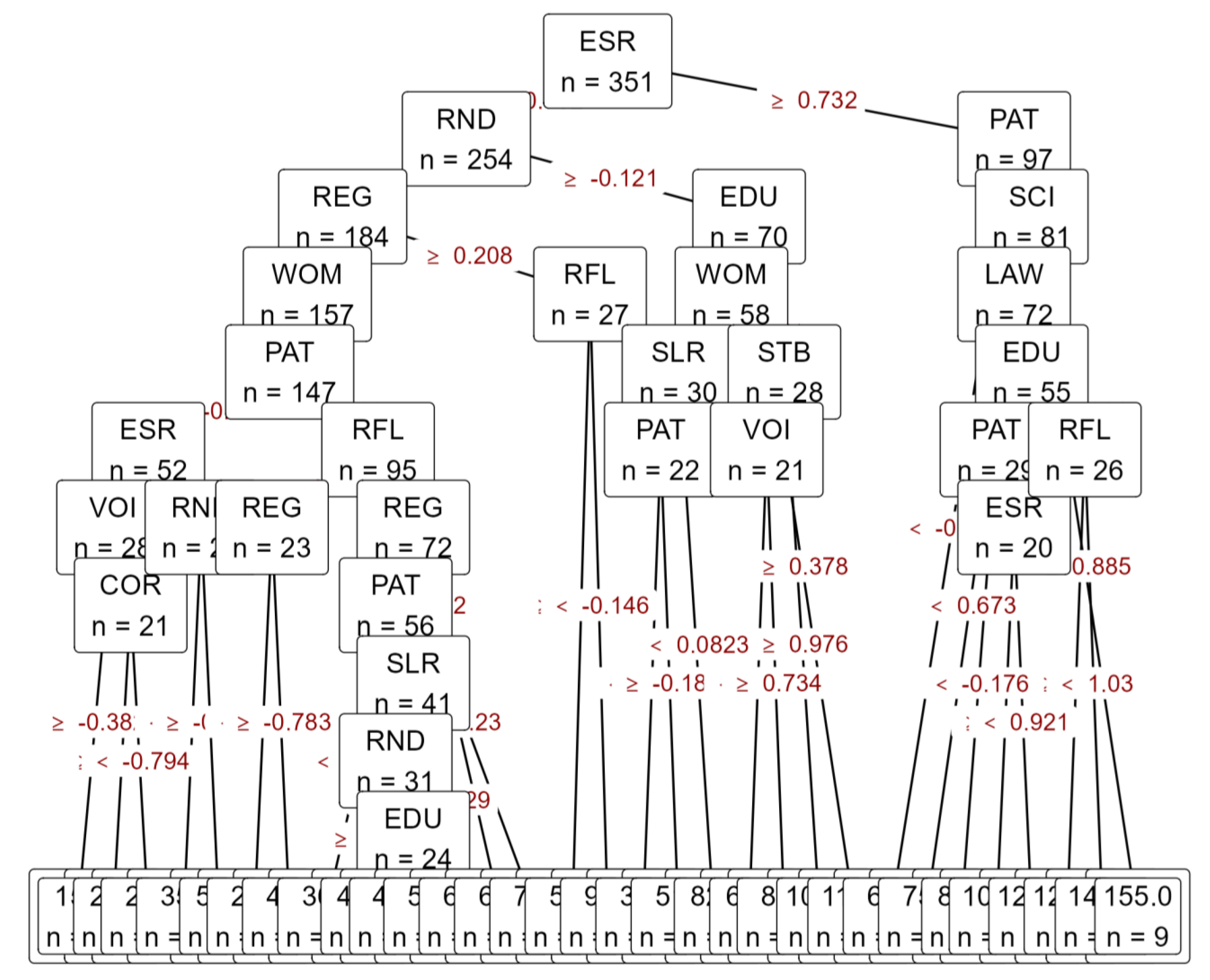

Instrumental variable (IV) analysis of the domestic credit to the private sector (DCB) variable within the ESG setting for environmental components yields crucial insights into the interplay between financial developments and environmental sustainability (Batrancea, Rathnaswamy, Rus, & Tulai, 2023). Firstly, the estimations from the three different methods: the First-D Differenced Instrumental Variables (FD-IV), Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS), and Random Effects Instrumental Variables (RE-IV), all together present different perspectives on the same processes but in varying levels of coefficient significance and model fit. The DCB used in the analysis serves as the dependent variable indicator for the credit allocated by the domestic banks to the private sector. This indicator also objectively represents the process of financial development for the involved nations (Bruno & Henisz, 2024). Additionally, the indicators used in the context of the different ETGR environmental aspects in the model include the availability of clean fuels for cooking (CFC), natural resource depletion (ELE), and CO₂ per person (CO2). Additionally, the selection of the used instruments like the ESR performance on economic & social aspects (ESR), spending on the expenses of educating (EDU), the amount of patents (PAT), the regulation parameters (REG), rule of law (LAW), production output for scientific research (SCI), usage levels for the internet (INT), along with the strength of legal rights (SLR), all together attempt to directly represent the institutional & technological aspects within the context of both financial & environmental components in the study. Moreover, the selection of the instruments used in the model also aims to ensure the overall validity of the research, while remaining unconditional with respect to market fluctuations in the concerned credits. According to the FD-IV model specification, in which time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity is eliminated through differencing, the CFC coefficient is positive and significant (2.41, p = 0.021). This suggests that greater access to clean fuels is associated with expanded domestic credit availability. This is consistent with the interpretation that environmentally sustainable infrastructure and cleaner energy access contribute towards the growth of the financial system (Chen, Yu, & Qian, 2024). This could occur through increased productivity, reduced health costs, and more efficient use of human capital in regions that adopt cleaner energy sources (Zhang, Wei, Ge, Zhang, & Xu, 2025). However, the ELE coefficient is negative but not significantly different from zero (-1.53, p = 0.219). This suggests that resource depletion might undermine credit availability through its degrading impact on environmental resources. However, the effect might not persist in the long term (Shen & Zhang, 2022). However, the CO2 coefficient is negative and significantly different from zero on impact (-2.31, p = 0.006). This suggests that higher CO2 emissions might decrease credit availability in the economy (Mandira, Priyadi, & Wong, 2025). This might occur because countries that rank higher in terms of pollutant levels also tend to have financial system restraints. This might occur due to the weak institutional framework in countries that prioritise financially risky environmental activities (Chodnicka-Jaworska, 2022). The intercept is negative and significantly different from zero. The 2SLS results, correcting for endogeneity by using instrumented predictors, indicate that CFC is significantly positive (1.38, p < 0.001), verifying that access to cleaner energy sources promotes credit expansion despite the simultaneous influence (Zhang et al., 2025). ELE remains significantly negative (-1.33, p = 0.005), indicating that natural resource depletion directly harms the financial sector’s development, possibly by inducing macroeconomic instability and eroding confidence in sustainable investments (Shen & Zhang, 2022). Notably, CO2 turns significantly positive (1.21, p = 0.002), suggesting that the instrumented variable captures the short-term positive influence of industrialisation on credit availability despite its adverse environmental impact (Alshubiri, Elheddad, Jamil, & Djellouli, 2021). This might relate to the credit system’s “growth bias” in industry choice, which emphasises the sector’s higher short-term profits within the financial system despite their adverse impact on the environment (Pyka & Nocoń, 2023). Model significance and goodness-of-fit parameters clearly signify its robustness. CFC & ELE confidence intervals are small in width, while the intercept is substantially larger (69.82, p = 0.036), implying the existence of structural variations in credit system behaviour unaccounted for in the regression model parameters (Batrancea et al., 2023). Compared to the RE model, the RE-IV model adds the assumption that the omitted individual heterogeneity is uncorrelated with the covariates. Here, the positive effect of CFC is strengthened (2.85, p = 0.001), while the negative effect of ELE holds (−3.86, p = 0.032). The persistent significance of the effect on the variable for access to clean energy throughout all models confirms its importance regarding sustainable financial development (Chen et al. 2024). This finding indicates that the enhancement of access to advanced energy infrastructure contributes to social welfare improvement by fortifying credit systems through the increased economic resilience of individuals and businesses (Zhang et al. 2025). Also, the negative effect of resource depletion holds for all the estimations. This finding indicates that inefficient utilisation of natural resources negatively limits the growth of the credit system due to heightened financial instability within countries (Shen & Zhang, 2022). Additionally, in the RE-IV model, the negative effect of CO2 becomes insignificant (-0.35, p = 0.613). This finding indicates that accounting for individual heterogeneity in the model strengthens the insignificance of CO2 in explaining credit system development across countries, due to structural differences in CO2's effects on credit system development (Mandira et al. 2025). Standard errors of all estimators are moderate, though larger in the RE-IV model, because of the sensitivity introduced by the variable representation of the random effect. However, the z-statistics for all estimators rank CFC as the most stable variable in the model, followed by ELE. CO2 turns out to be significant in terms of sign alternatives according to model specification because the CO2-credit nexus might exhibit complex temporal linkages in terms of growth-economic externalities (Bruno & Henisz, 2024). However, the reliability of consistent estimates reinforces the claim that environmental enhancement related to access to clean energy deepens financial markets rather than undermining them due to resource depletion (Pyka & Nocoń, 2023). From the wide-ranging ESG analysis, the following implications emerge regarding the link between environmental efficiency and nations' financial inclusiveness (Chen et al. 2024). Nations that make progressive developments in sustainable energy transition achieve positive environmental outcomes and improvements in their credit markets (Xiangling & Qamruzzaman, 2024). By contrast, nations that rely on resource extraction or fare poorly in environmental resource management display weak credit market infrastructure (Chodnicka-Jaworska 2022). By incorporating institutional-technology-based measures such as rule-of-law administration, patenting rates, and research output rates into the model analysis, one can avoid purely mechanical causal linkages (Batrancea et al. 2023). Thus, the IV analysis suggests positive financial outcomes for nations adopting environmentally sustainable economic policies, along with improved measurement of sustainable economic development through the incorporation of environmental efficiency into financial models (Zhang et al. 2025). See

Table 3.

The FD–IV model, which eliminates time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity through first differencing, reveals modest explanatory power, as indicated by the low within R

2 of 0.0111. However, the Wald test (χ

2 = 14.19, p = 0.0027) confirms the joint significance of the regressors. The negative correlation between the error component and the regressors (corr(u_i, Xb) = -0.7209) indicates that unobserved country-specific factors are negatively associated with financial development, suggesting structural barriers that persist over time (Zioło et al., 2023). The coefficients suggest that improvements in access to clean fuels (CFC) positively affect credit growth, while resource depletion (ELE) and CO₂ emissions exert negative effects. This implies that environmentally sustainable progress, such as cleaner energy and resource preservation, can promote credit expansion, possibly by improving productivity, reducing risks, and strengthening institutional trust (Ma et al., 2023). In contrast, environmental degradation appears to constrain credit availability, reflecting the financial market’s sensitivity to sustainability risks (Fu et al., 2023). The 2SLS estimation enhances precision by addressing potential simultaneity between financial and environmental variables. The model shows strong significance (F = 37.44, p = 0.0000), confirming the validity of the instruments. The identification tests reinforce the model’s robustness: the Anderson LM test (χ

2 = 122.525, p < 0.001) rejects underidentification, and the Cragg-Donald F-statistic (15.435) indicates sufficient instrument strength. The overidentification Sargan test (χ

2 = 119.769, p < 0.001) confirms that the instruments collectively explain the endogenous variation in the regressors. The high uncentered R

2 (0.7276) indicates a strong overall fit, suggesting that institutional and environmental quality together explain much of the variation in credit expansion (Thapa et al., 2025). In this model, cleaner energy access (CFC) remains a robust positive predictor of credit, while natural resource depletion (ELE) is negatively and significantly related to DCB. CO₂ emissions have a positive coefficient, suggesting that in some cases, industrial expansion driven by emissions temporarily boosts credit availability. However, this may also indicate a trade-off between short-term economic growth and long-term environmental sustainability (Batool et al., 2025). The RE–IV model incorporates random effects to capture unobserved heterogeneity across countries while assuming it is uncorrelated with the regressors. The results are consistent with the other models but reveal slightly lower overall explanatory power (overall R

2 = 0.0255). The Wald statistic (χ

2 = 14.98, p = 0.0018) confirms overall model significance, and the high intra-class correlation (ρ = 0.9472) indicates that much of the variance in credit is explained by country-specific factors (Zioło et al., 2023). Clean energy access (CFC) continues to have a positive and significant effect on DCB, reinforcing the idea that energy transition policies have financial benefits (Ma et al., 2023). The strong negative relationship between ELE and DCB supports the argument that unsustainable resource use limits financial development by creating economic and ecological instability (Fu et al., 2023). CO₂, though negative, is not significant, implying that once random effects are considered, emissions do not directly influence credit markets across countries (Wu, Ivashkovskaya, Besstremyannaya, & Liu, 2025). Comparing the three estimators, consistent patterns emerge: access to clean energy is a key driver of financial sector development, while resource depletion systematically undermines it. These results are consistent with ESG theory, which posits that environmental sustainability and institutional strength are mutually reinforcing in promoting financial inclusion and credit expansion (Thapa et al., 2025). The 2SLS estimator performs best in terms of robustness and identification, indicating that addressing endogeneity is essential for capturing the true relationship between environmental and financial variables (Wu et al., 2025). Overall, the analysis highlights that countries with stronger environmental governance, innovation capacity, and legal institutions are better positioned to achieve sustainable financial growth (Ma et al., 2023). Financial systems appear to reward environmental responsibility, suggesting that integrating ESG principles into financial regulation can yield both economic and ecological dividends (Batool et al., 2025). See

Table 4.

The robustness checks conducted with two alternative instrumental variable estimators—the two-stage least squares with GMM2S correction (IV–2SLS) and the first-differenced instrumental variables model (FD–IV)—confirm the reliability and consistency of the main findings linking domestic credit to the private sector (DCB) with key environmental variables (Paddu et al., 2024). These estimators assess whether the observed relationships remain stable under different assumptions about unobserved heterogeneity and model structure. Both models use clustered robust errors to control for within-country correlation, but they differ in their treatment of time effects and the elimination of bias from unobserved country-specific factors (Jahanger, Usman, & Ahmad, 2023). In the IV–2SLS model, access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (CFC) has a positive coefficient of 3.51, though the standard error (2.51) implies moderate uncertainty. This positive sign confirms that improving access to clean energy is associated with greater financial development (Wu, et al., 2024). Cleaner energy systems likely improve productivity, reduce health-related costs, and strengthen households’ and firms’ financial stability, enabling greater access to credit. The large coefficient indicates that energy access plays a meaningful role in deepening financial markets, although cross-country differences may explain the statistical imprecision (Zoungrana et al., 2025). Natural resource depletion (ELE) shows a negative but insignificant effect (–5.72), consistent with the idea that environmental degradation weakens financial stability by eroding long-term economic sustainability (Jahanger et al., 2023). The wide confidence range suggests that the impact of depletion varies depending on institutional and resource characteristics. Carbon emissions (CO₂) are positive (0.33) but insignificant, indicating that in some contexts, industrial expansion may temporarily raise both emissions and credit flows (Tuna et al., 2023). Nonetheless, the lack of significance prevents drawing firm conclusions.Diagnostic tests confirm that the model is well identified: the Kleibergen-Paap F statistic (14.77) rejects weak instrument concerns, the Hansen J test (p = 0.337) confirms instrument validity, and the underidentification test (p = 0.0298) supports proper model identification. The FD–IV model, which focuses on within-country variation by removing fixed effects through differencing, reveals stronger evidence of causal links (Wu, Q., 2024). The coefficient of CFC remains positive and statistically significant (2.41, p < 0.05), confirming that clean energy access consistently promotes credit expansion (Zoungrana et al., 2025). The smaller standard error (1.04) compared with the IV–2SLS model reflects higher precision once unobserved heterogeneity is controlled for. The coefficient of ELE is again negative (–1.53) but insignificant, suggesting that depletion’s adverse effects emerge over longer periods. By contrast, CO₂ turns negative and highly significant (–2.31, p < 0.01), indicating that once fixed country characteristics are accounted for, higher emissions are associated with reduced credit availability. This reversal shows that environmental degradation ultimately constrains financial development when persistent structural effects are isolated (Paddu et al., 2024). The Wald χ

2 statistic (14.19, p = 0.0027) confirms the joint relevance of the explanatory variables, and the smaller sample size due to differencing does not compromise efficiency. Overall, both estimations confirm the robustness of the main results. Clean energy access remains a consistent and positive driver of financial growth, while natural resource depletion weakens it (Xie et al., 2024). The negative and significant CO₂ effect in the FD–IV model further demonstrates that environmental deterioration harms financial expansion once unobserved heterogeneity is addressed (Tuna et al., 2023). The diagnostic tests validate instrument strength and confirm that the findings are not model-dependent but represent a stable structural relationship between environmental sustainability and financial sector performance (Wu, Q., 2024; Xie et al., 2024). See

Table 5.

3.1. Environmental ESG Determinants of Domestic Credit: A Machine Learning Perspective

In testing the link between the Environmental dimension of the ESG factors and the Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB), the approach employed in the proposed work utilises an exhaustive data set provided through the World Development Indicators available at the World Bank. The purpose here would be an understanding related to the manner in which the dimensions related to the quality, sustainability, and factors related to the management of the environment, and the factors related to the climate, associate and correlate with the development factors related to finances, specifically the aspect related to the development and extension of the credit services provided in the banking sectors in relation to the private sectors, as proposed by Norouzian and Gheitarani in the year 2025. The dependent variable in the proposed work would be the DCB, and the DCB would essentially represent the development factor in relation to the increased accessibility and development related to the extension services related to the finances, specifically related to the development and extension services and capacity in relation to the private sectors, and the purpose here would be the scope and extent related to the development factors in relation to the manner in which the worldwide environment would associate and correlate, and the extent related to the DCB, specifically. The model's environmental variables examine various aspects of ecology. Land-use variables such as Agricultural Land (AGL) and Forest Area (FAR) capture the structured aspects of national economies, reflecting the sustainability of land use (Zhang et al., 2024). Biodiversity variables such as Threatened Mammal Species (THM) and Tree Cover Loss (TCL) help identify habitat and associated stress. Variables related to pollutants, such as Nitrous Oxide Emission (N2O), Methane Emission (CH4), CO2 Emission Per Capita, and PM2.5 Exposure, identify the environmental pressures associated with development, industry, and energy sources (Kolawole et al., 2022). These variables are important for identifying the environment in which the risk and vulnerability in the financial situation could be affected by the development path, especially the environment- and pollution-intensive development path. Other important factors include the consumption of renewable energy (REN), the depletion of natural resources (NRD and FOD), and energy intensity (EIN), all of which reflect the efficacy and sustainability achievable in the energy framework across different countries (Dobrovolska et al., 2023). Climate and hydrologic factors like the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPE), the withdrawal of fresh water (FWW), the number of cooling and heating degree days (HDD and CDD), the land surface temperature (LST), and water stress (WST) all reflect the effect and contribution of climatic changes and resource limitations on economic performance and development (Zhang et al., 2024). The other socio-environmental factors like access to clean fuels and cooking technologies (EF,C), access to electricity (ELE), the food production index (FPI), the agricultural value added (AGV), and the net migration (MIG) help supplement the database in reflecting the relationship between environment and sustainable development. By using this comprehensive set of variables, the researcher can capture the richness and dimensionality provided by the Environmental dimension of ESG, enabling the researcher to comprehensively evaluate the impact that environmental pressures and factors have on the financial markets and the flow of credits globally (Norouzian & Gheitarani, 2025; Kolawole et al., 2022). See

Table 6.

Among the models tested for their predictive performance, the K-Nearest Neighbors algorithm emerges as the most successful. The K-Nearest Neighbors algorithm has the lowest values for error measures such as mean squared error, scaled mean squared error, root mean squared error, mean absolute error, and mean absolute percentage error. In terms of the coefficient of determination, the algorithm yields the highest value, R

2 = 1.000. This means the algorithm has the highest predictive ability and that there are no deviations in the predicted values. The model's success could be attributed to the characteristics of K-Nearest Neighbors, which make it non-parametric. The model, in terms of its characteristics, can predict because it does not make assumptions about the distribution. The resulting model's predictive performance depends on the data's closeness. Given the lower predictive performance, the model could work better on data with sufficient structure. Artificial Neural Networks and Support Vector Machines would possibly experience overfitting. The other models, like Random Forests and Boosting, might perform better than the K-Nearest Neighbors model and handle local changes better. The K-Nearest Neighbors method has high precision and stability in its results. See

Table 7.

The K-Nearest Neighbours algorithm's results provide an insightful representation of the effects of environmental variables on DCB within the ESG framework, among other factors, according to Halder, Uddin, Uddin, Aryal, and Khraisat (2024). The reason the K-Nearest Neighbours algorithm performs better in environment variables' effect on DCB compared to other models like the ARDL approach might be attributed to the fact that the algorithm used in the study, K-Nearest Neighbours, does not enforce basic functional forms on the variables; rather, it relies on the concept of measuring each observation against the closest neighbouring observations. This characteristic affects the dimensionality of the environmental variables, enabling the algorithm to detect relationships among variables while attenuating the effects of high dimensionality. The average dropout loss values reported in this work show the extent of deterioration in the predictive power when each predictor is dropped, uncovering the role of the different environmental factors related to financial development. The variables corresponding to the largest average dropout loss values, namely agricultural land use (AGL), protected areas (PRA), nitrous oxide emissions (N₂O), forest area (FAR), methane emissions (MET), and threatened mammals (THM), provide evidence on the critical role played by the intensity factor in the DCB process, according to environment theory. The high visibility of AGL and PRA indices suggests that economies with large arable farmland and secure areas are subject to large-scale, interactive trends in the environment and the economy, which heavily impact credit markets. Secured areas may represent the quality of stable ecosystems and sustainable development, making financial risk less important and facilitating broader credit development (Yang et al., 2025). On the other hand, high levels of N2O and CH4 release represent pollution-intensive sectors, contributing less to the quality and capacity of the ecosystem and, accordingly, to financial development, because they increase environmental risk factors, making the ecosystem unproductive and unresponsive to adequate financial flows. The factor “THM” indicates that risks exerting pressure on biodiversity act indirectly through proxies in aspects related to environmental limitations and institutions, directly obstructing financial development. The intermediate dropout values for the loss related to the consumption of renewable energy (REN), the use of natural resources (NRD), energy intensity (EIN), freshwater withdrawal (FWW), and the climate change-specific SPE indicator underscore the continued relationship between resource use efficiency and environmental sustainability and the relationship between respective resource efficiencies and access to credit. When energy intensity is high and resource use is high, the inference is that the economic system is inefficient and poses risks to the environment and finance. The model's sensitivity to the freshwater indicator corroborates the supposition that environmental resource scarcity has direct financial consequences.Lower yet still important dropout loss values are associated with variables such as access to clean fuels (CFC), food production (FPI), agricultural value added (AGV), net migration (MIG), tree cover loss (TCL), and temperature proxies such as HDD, CDD, and LST. These variables have a more indirect effect on DCB. That is, CFC, an indicator reflecting the increase in the benefit thing and the adoption process related to technological advancements, could potentially raise productivity and the need for better credit access (Sibutar-Butar et al., 2025). The processes of migration, tree cover, and the effects of climatic stressors convey broader trends related to the environment, ecology, and climatic conditions influencing the economy. The important thing here is the non-negligible dropout loss across all these variables, indicating the effect of the second-order environment and climatic variables on the process. The distribution of dropout loss values illustrates KNN's ability to detect complex interactions between the environment and finance. The variables that explain land use, the environment, and emissions are the most important factors in DCB because they can explain the financial and vulnerability structures. The variables explaining resource use, climate change, and the transition to renewable energy come next. This suggests that proper resource use and management remain important in DCB to ensure continued credit growth, as explained in Matloff's 2022 paper. KNN, which relies on patterns of similarity rather than coefficients, draws attention to the holistic framework in which credit growth is situated within larger ecologies. The findings underscore that financial development depends on the entire framework of ecologies, rather than on single pressures, and on the overall health and conditions they provide. In other words, the critical role of the environment pillar in the ESG framework has once again come to the fore. The relationship between the performance of the financial system and ecologies, and the sustenance and development thereof, has become the subject of models like KNN, which recognise this relationship as complex and interconnected, rather than linear.

Table 8.

The K-Nearest Neighbours model reveals the relationship between environment, climate, and the economic factors that, in dynamic terms, define the contribution of the domestic credit to the private sector (DCB) contribution, protecting the environment and reducing risks in the banking and financial systems, indicating the role and contribution through the model provided by Srisuradetchai & Suksrikran in 2024. The DCB forecasts range from 35 to 56, keeping it below the threshold of approximately 68. The negative deviations indicate a strong negative effect from the environment and sustainability themes on the extension of credit, highlighting the vulnerability and impact on financial systems in an ecologically and macro-environmentally uncertain environment, in line with the contribution and role of Souddi and Bouzebda in 2025. The variables AGL, AGV, and FAR have negative coefficients, indicating lower productivity and coverage in terms of greenhouse gases, an indication of lower access and extension in terms of DCB. On the other hand, the negative margins for methane gas (MET) and nitrous oxide gas (N2O) indicate that an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations could be associated with economic inefficiencies and increased risk perception, thereby reducing loan activities, as proposed by Li et al. (2021). However, other variables, such as access to electricity (ELE), access to clean fuels (CFC), and the use of renewable energy sources (REN), show positive and weak margins (Srisuradetchai, 2023). These imply that energy access and clean technologies could facilitate financial inclusion and the development of credit, thereby contributing to increased productivity and mitigating climate change-related risks. Climate variables such as cooling degree days, heating degree days, and land surface temperatures, among others, produce inconclusive results. Climate risk, in relation to economic development and the development of credits, exhibits geographical and irregularities, thereby influencing the vulnerability to climate change and the development of credits in different dimensions (Şevgin, 2025). In general, the KNN model demonstrates the validity and relevance of the relationship between domestic credit and variables related to environmental sustainability and climate change adaptation. The discovery made in this problem reveals the dependence and relationships among credit and macroeconomic development, environmental stability and quality, and factors concerning climate change (Souddi & Bouzebda, 2025; Srisuradetchai & Suksrikran, 2024).

Table 9.

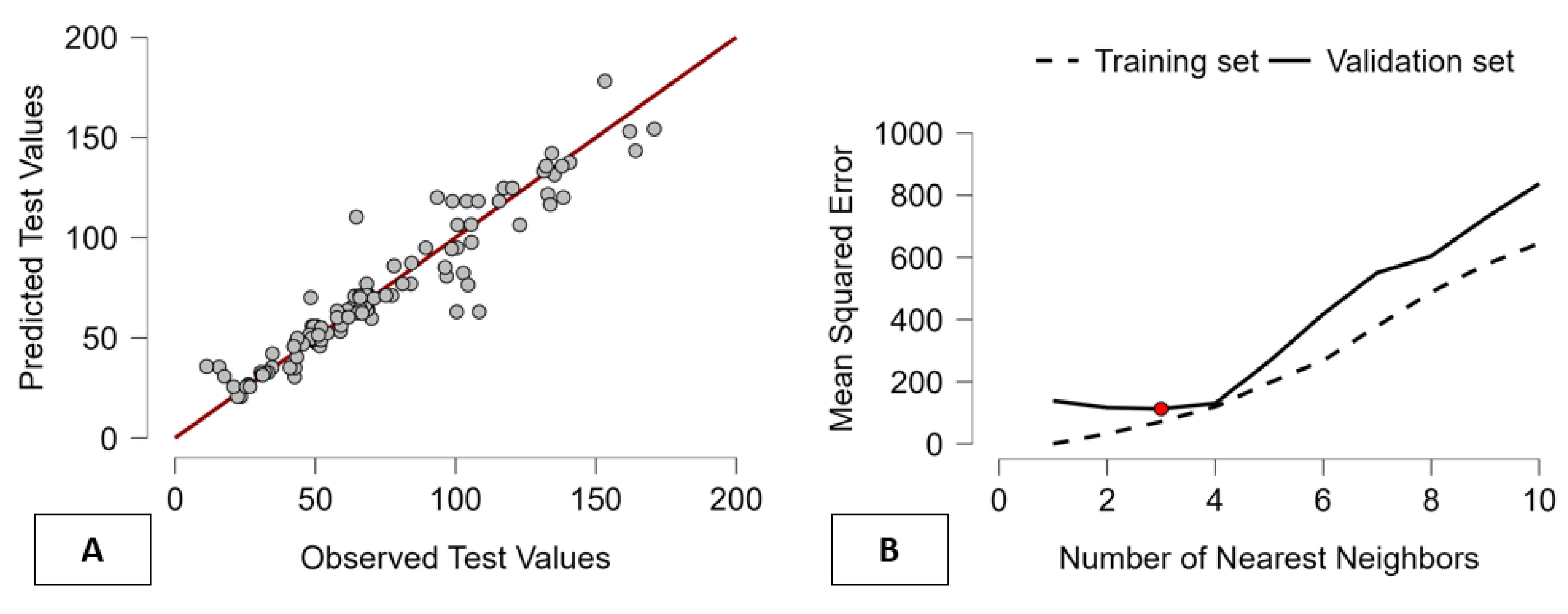

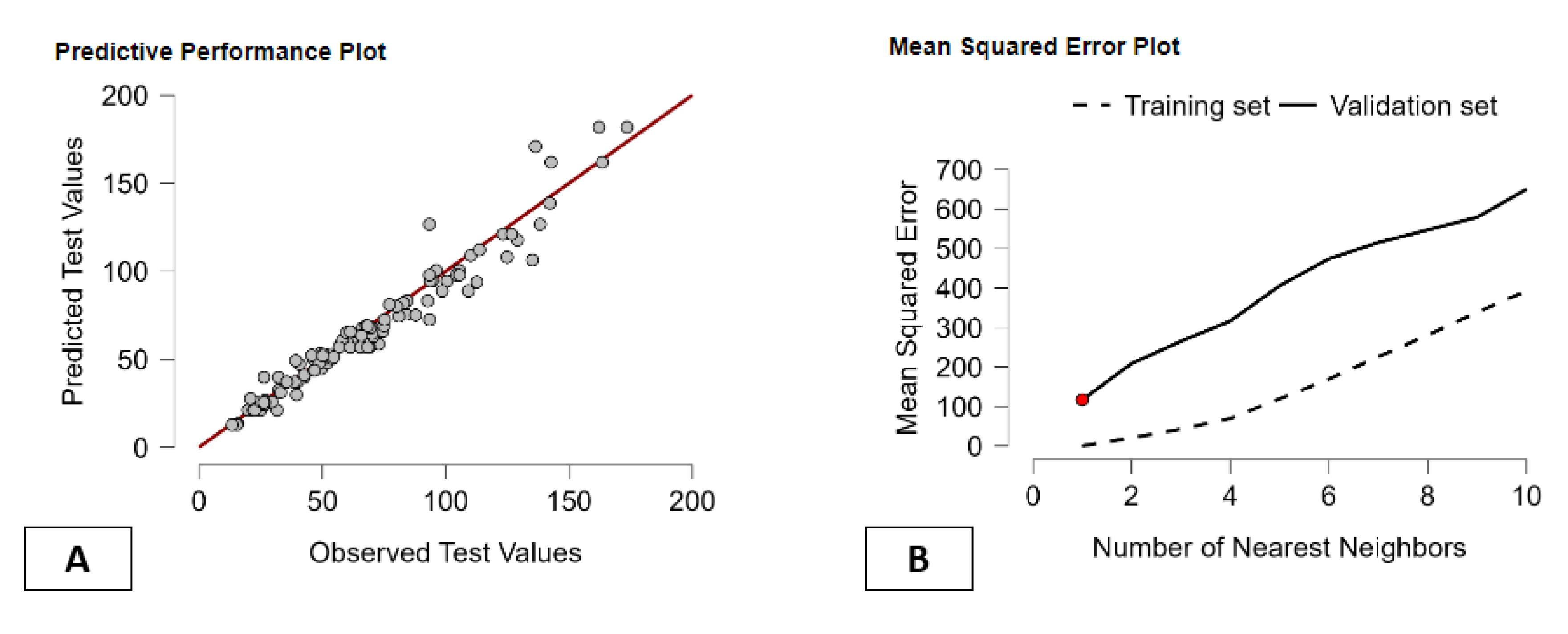

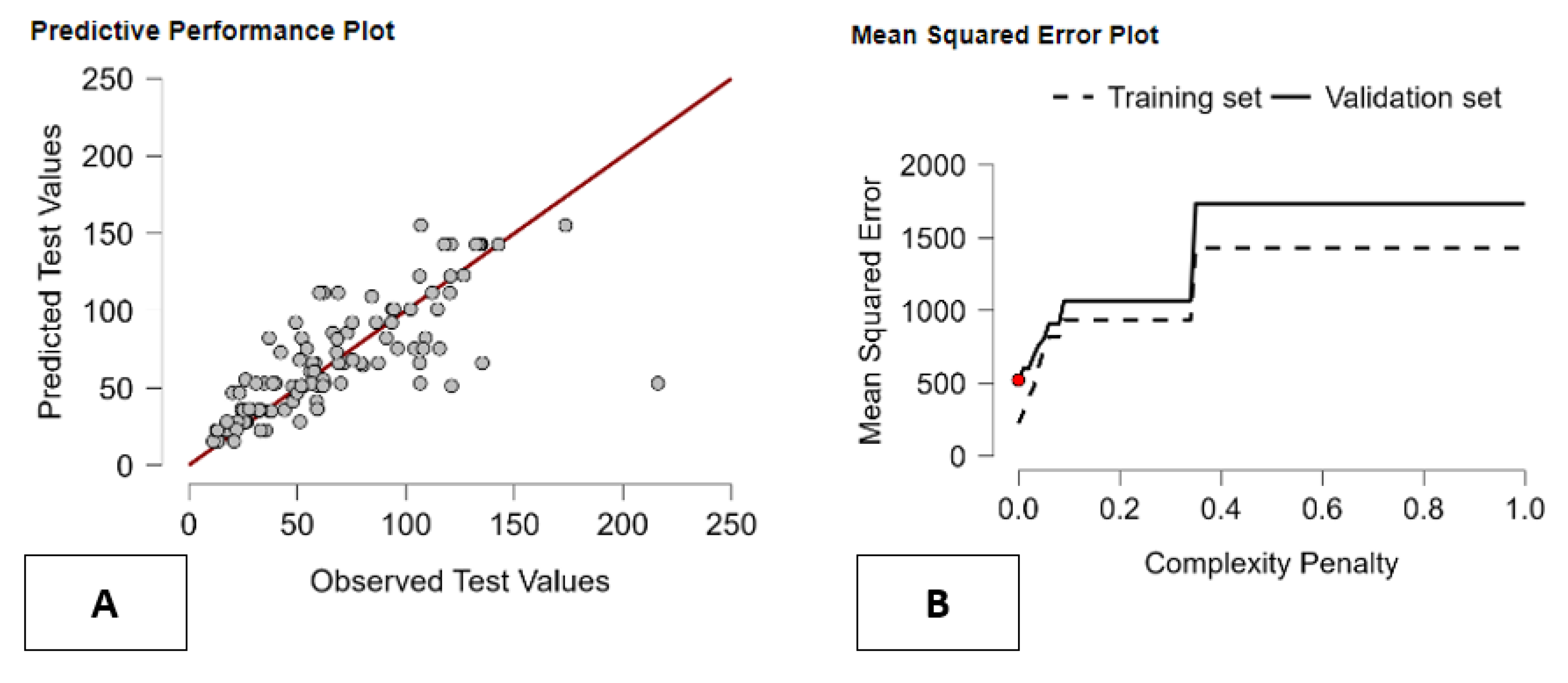

The K-Nearest Neighbors Regression KNN model employed in the approximation process regarding the value of the estimated domestic credit to the private sector DCB performs well in terms of predictability and consistency in both the training and validation steps, respectively (Srisuradetchai & Suksrikran, 2024). In the first panel, there is a strong fit between the predicted and actual data, with the great majority of data points closely aligned with the reference line. The high degree of fit indicates that the variables employed, including DCB and the set of environmental, climatic, and economic variables, are adequate for describing the complex factors influencing the development process. The strong alignment in the residual distribution confirms the absence of bias, ensuring satisfactory performance and validity of the KNN model in the predictive process. The graph in the second panel reveals the relationship between the average squared error MSE and the number of neighboring samples in the KNN model. In the graph, the red spot indicates the optimal performance achieved when a small number, denoted by the red spot at k=4, of neighboring samples are considered, resulting in an optimal error. The increase beyond the red spot indicates optimal performance with the K-Nearest Neighbors regression model, where the model tends to oversmooth and lose precision, since high values, denoted by the red spot, correspond to local sample features. The KNN model performs adequately in the integration process concerning the environment and economic factors, suggesting that sustainable resource management practices and high quality environment are the most important factors influencing the distribution process, and the application and incorporation of the related variables, namely the ESG factors, in KNN models underscore the important role and rise in the usage and application in KNN models, generally, in explaining the structure and stability and performance in the process concerning the financial environment in various countries (

Figure 1).

3.2. Clustering Environmental Regimes to Explain Domestic Credit Dynamics

The clustering performance metrics offer a clear assessment of how effectively the considered algorithms capture the environmental structure relevant for explaining Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB) (Morelli, Boccaletti, Maranzano, & Otto, 2025). Because the model associates DCB with a wide set of environmental, ecological, climatic, and resource-efficiency indicators (including land use, protected areas, emissions, biodiversity pressure, renewable energy, water stress, energy intensity, climate extremes, and environmental depletion metrics), an adequate clustering algorithm must be able to identify coherent and well-separated environmental profiles across countries (Saraswati et al., 2024). Among all methods, hierarchical clustering provides the strongest internal validity. It achieves the highest Silhouette score (0.300), the largest minimum separation (2.233), and the best Dunn index (0.288), indicating that it forms compact, non-overlapping clusters. This implies that hierarchical clustering is particularly effective at distinguishing diverse environmental conditions that may produce heterogeneous effects on financial development and credit allocation (Zioło et al., 2023). The high Pearson’s γ further confirms a strong correspondence between the environmental distance structure and the clusters produced. Density-based clustering achieves the highest R

2 (0.865), suggesting greater explanatory power, but it suffers from high entropy and much weaker separation metrics, implying diffuse and unstable clusters. K-Means and model-based clustering offer intermediate performance, with balanced compactness but less pronounced separation, while Fuzzy C-Means shows clear weaknesses across all validity indices (Sica et al., 2023). Given the multidimensional nature of the environmental variables used to estimate DCB—spanning agricultural structure (AGL, AGV, FPI), natural resource depletion (NRD, FOD), emissions (CO₂, N₂O, MET), biodiversity pressure (THM, TCL), energy access and efficiency (ELE, CFC, EIN, REN), climate conditions (HDD, CDD, LST, HI3), and hydrological stress (FWW, WST, SPE)—hierarchical clustering emerges as the most reliable method for identifying distinct environmental regimes (Morelli et al., 2025). These regimes are critical for understanding how heterogeneous environmental conditions shape the availability of domestic credit, confirming that the hierarchical approach best captures the structural diversity underlying the E-Environment–DCB relationship (Alahewat, Orabi, Abualfalayeh, & Samara, 2024).

Table 10.

The hierarchical clustering analysis reveals substantial variability in environmental profiles under the Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB) indicator (Morelli et al., 2025). The algorithm finds 23 clusters, each rather different in terms of the number of observations, density, and separation, reflecting the high-dimensional characteristics and variables in the environmental profiles. The sizes of the clusters range from a large group with 286 observations to those with merely 5-7 units, showing that countries' environmental profiles approximate each other in a rather uneven manner (Mityakov et al., 2023). This could mean that a large group of countries tends to align with rather homogeneous environment profiles, while the remaining countries have rather different environment structures. The percentage in the total explained variances in the clusters confirms this supposition. The largest cluster has an independent contribution of 64.3%, and the remaining clusters provide a minor contribution, ranging approximately from 0.1-1%, indicating that they capture rather specific environmental structures, distinct from the general one in the world environment profiles (Juca et al., 2024). The smaller clusters represent rather exceptional, peculiar environmental structures, and they fit rather high-dimensional variables such as land use, gas emissions, biodiversity loss, resource depletion, and climate change. Silhouette values provide strong evidence of the validity and quality of the resulting clusters. While the largest one has a silhouette measure of only 0.141, the others have rather high silhouette measures, typically over 0.70 and up to 0.884. Rather high silhouette values imply that the clusters are well separated from neighbouring collections and are overall rather cohesive. This supposition provides important evidence that the hierarchical algorithm finds the environment structures with rather high precision in smaller collections, even when the largest collection has lower silhouettes because it has a higher dimensionality and hence greater homogeneity within the collection (Alahewat et al., 2024). Moreover, it should be noted that the clusters 5, 8, 9, 12, 17, 20, and 22 have each rather high silhouette scores over 0.70, rather different environments, and perhaps occur in countries with rather exceptional climatic and environmental conditions. In general, the hierarchical algorithm performs rather well at detecting peculiar environmental structures that are meaningful in explaining variations in the DCB across countries. The presence of a large, moderately cohesive cluster and other smaller, highly distinct clusters points to the inhomogeneous distribution of factors affecting the development of credit across different countries, where possibly niche factors in the environment could be the determining factor in financial outcomes (Morelli et al., 2025; Mityakov et al., 2023). See

Table 11.

The mean values of the clusters reveal substantial disparities in environmental-financial conditions across nations, suggesting that different sets of environmental and resource factors contribute differentially to the extent of the domestic credit in the private sector (DCB) variables (Norouzian & Gheitarani, 2025). Some clusters have high DCB scores, often alongside better environmental performance and resource factors. Clusters 3, 8, 11, 14, 19, 21, and 22 have DCB scores above average, each due to different environmental factors. Clusters 3, together with high DCB, have high intensity on renewable energy sources (EIN = 0.934) and high agricultural value added (AGV = 0.789), and Clusters 8, together with high DCB, have large agricultural and forest areas (AGL = 2.476 and FAR = 1.331), signifying the economies where the productivity factor in the lands drives the financial development process in the nation (Noviandy et al., 2024). By contrast, those with strongly negative DCB values, such as Clusters 9, 10, 15, 16, 18, and 20, appear to be under environmental stress. Cluster 9, for example, scores remarkably high on its FPI dimension (FPI = 8.539) and high on other dimensions, such as FWW (0.263), MET (0.575), and FAR (- 0.970). Clusters 15 and 16 are characterised by high energy intensity, with EIN scores exceeding 2.5, and high scores on CDD and FOD, exceeding 2, representing a Gross Domestic Burden due to environmentally stressed conditions. There appears to be a prominent trend in cases involving high access indices. Clusters 11, 12, 13, and 21 reflect remarkably high scores on the energy access variables. Nevertheless, their credit performance varies in relation to ecologically stressed factors. While Cluster 11 has high DCB and moderately high ecologically stressed conditions, Cluster 21, despite the remarkably high CFC and high ELE, has moderately high DCB, in contrast, because they under moderately high water stress (WST = 8.287) and high agricultural depletion (PRA = -6.714) conditions (Boitan & Shabban, 2024). In sum, the clusters reveal that DCB has strong links with a combination of factors, such as quality, resources, and climate, rather than focusing on individual variables. The hierarchical process reveals some variant factors related to the environment, influencing financial development among different nations (Noviandy et al., 2024; Norouzian & Gheitarani, 2025). See

Table 12.

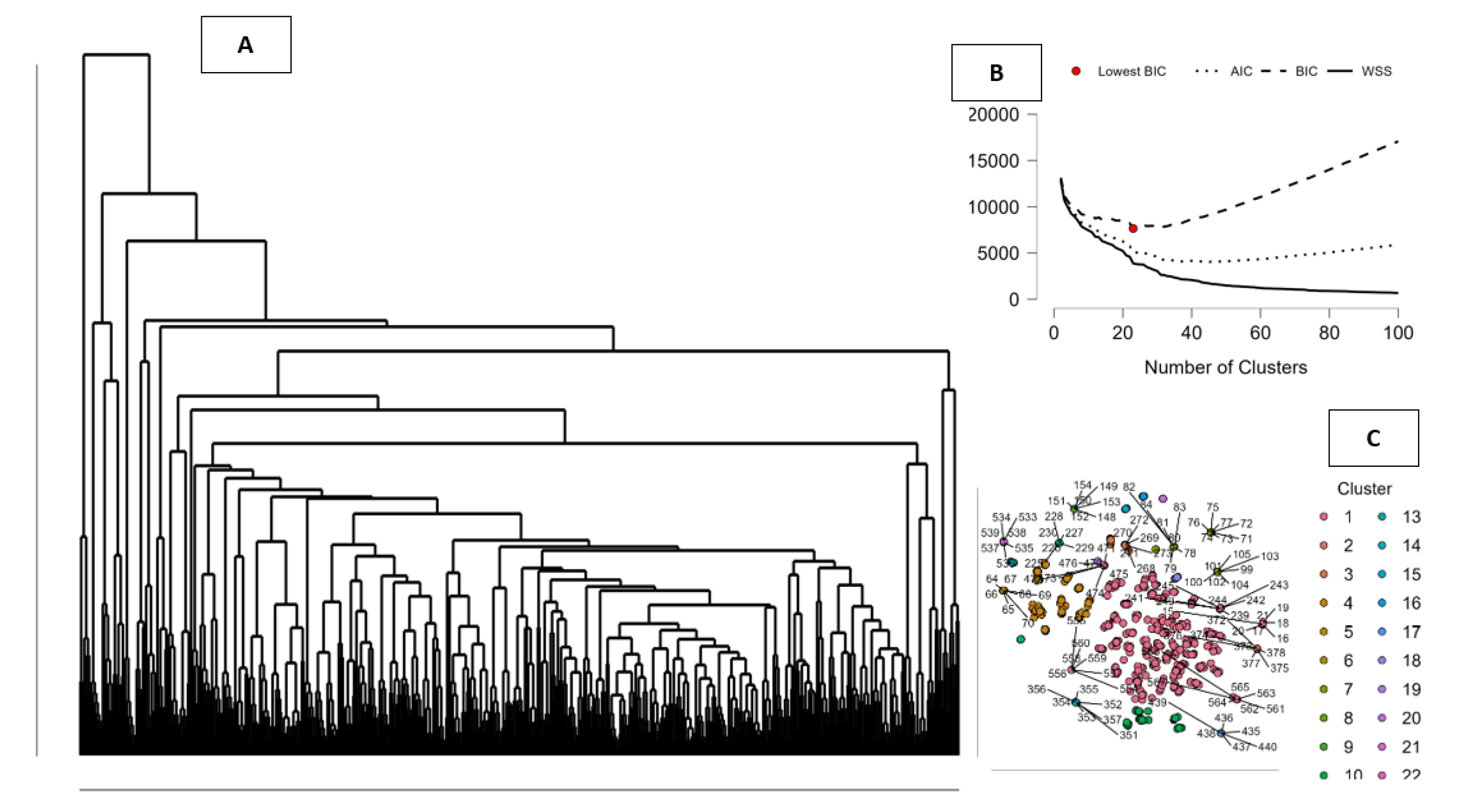

The

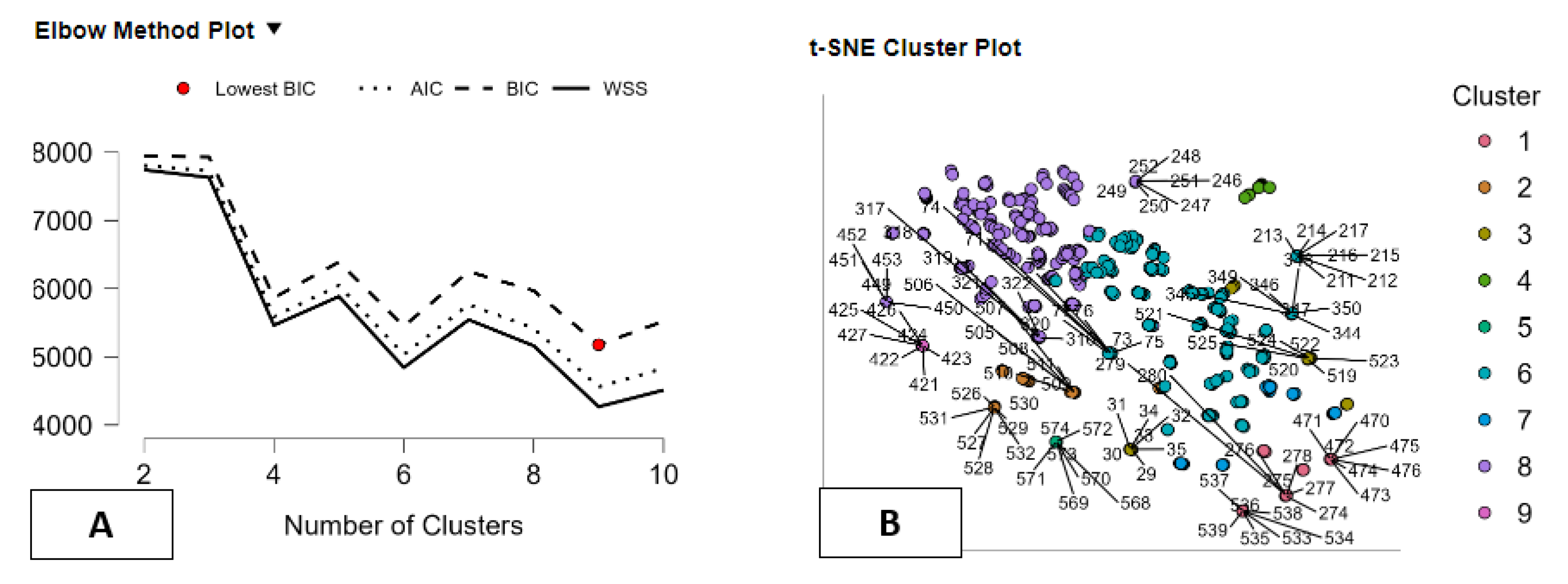

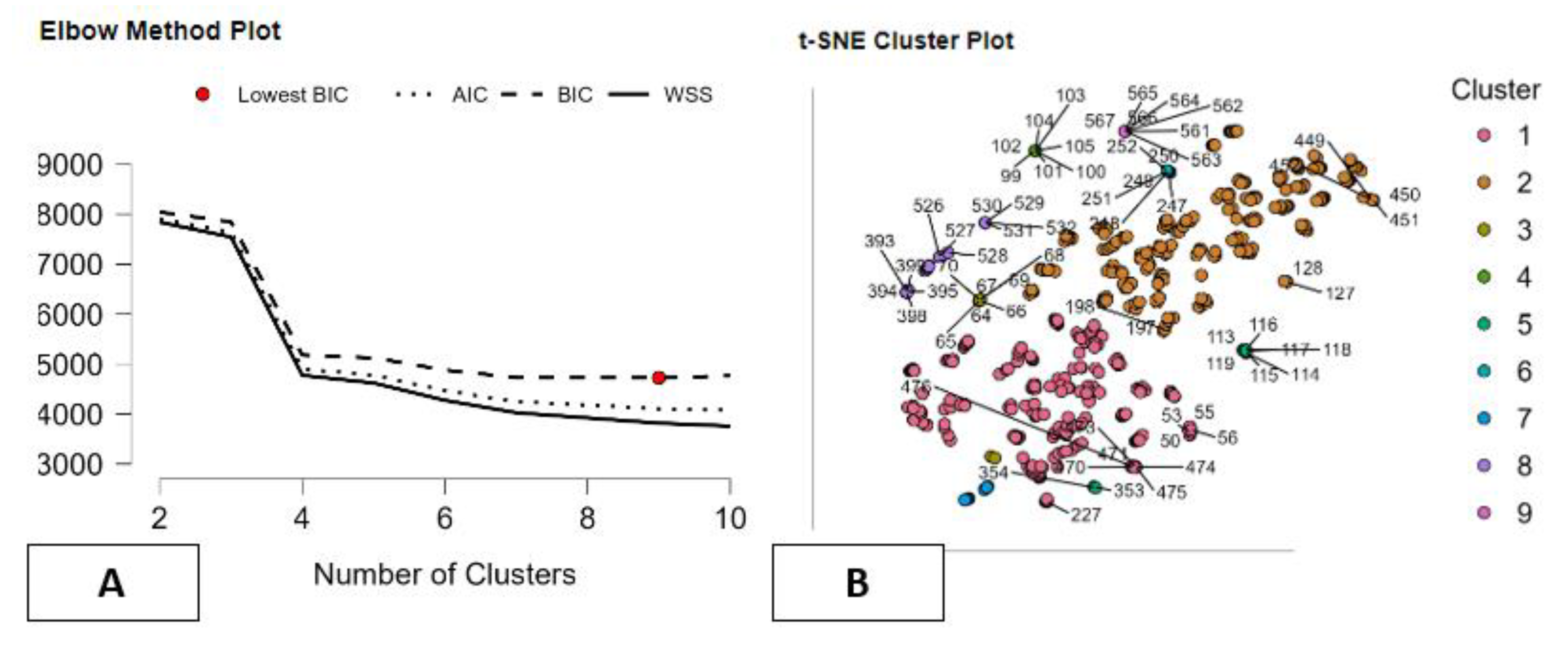

Figure 2 below offers a holistic representation of the hierarchical process and the optimal number of clusters in the environment dataset. In Figure A, the dendrogram resulting from the hierarchical agglomerative algorithm shows the hierarchical representation and the process through which observations are grouped on the basis of the environment. The high density on the lower branches denotes the heterogeneity among the countries, and the distinct separation on the upper branches denotes the formation of macro-clusters, hence the optimality of using the large number of clusters. In Figure B, the graph provides the basis for the choice of the optimal number through the information criteria and the sum of the squares within the clusters. The graph takes a sharp slope on the lower left, denoting the optimal choice after the use of approximately 22 clusters. The red dot denoting the BIC confirms the optimal choice, hence the optimality in balancing fit and model complexity. In Figure C, the process shows the representation in the two-dimensional space, denoting the separation among the clusters and the validity in the hierarchical process. The distinct color denotes the different clusters, hence the environment denoted by the distinct characteristics (

Figure 2).

3.3. Network Interdependencies Between Environmental Factors and Domestic Credit Provision

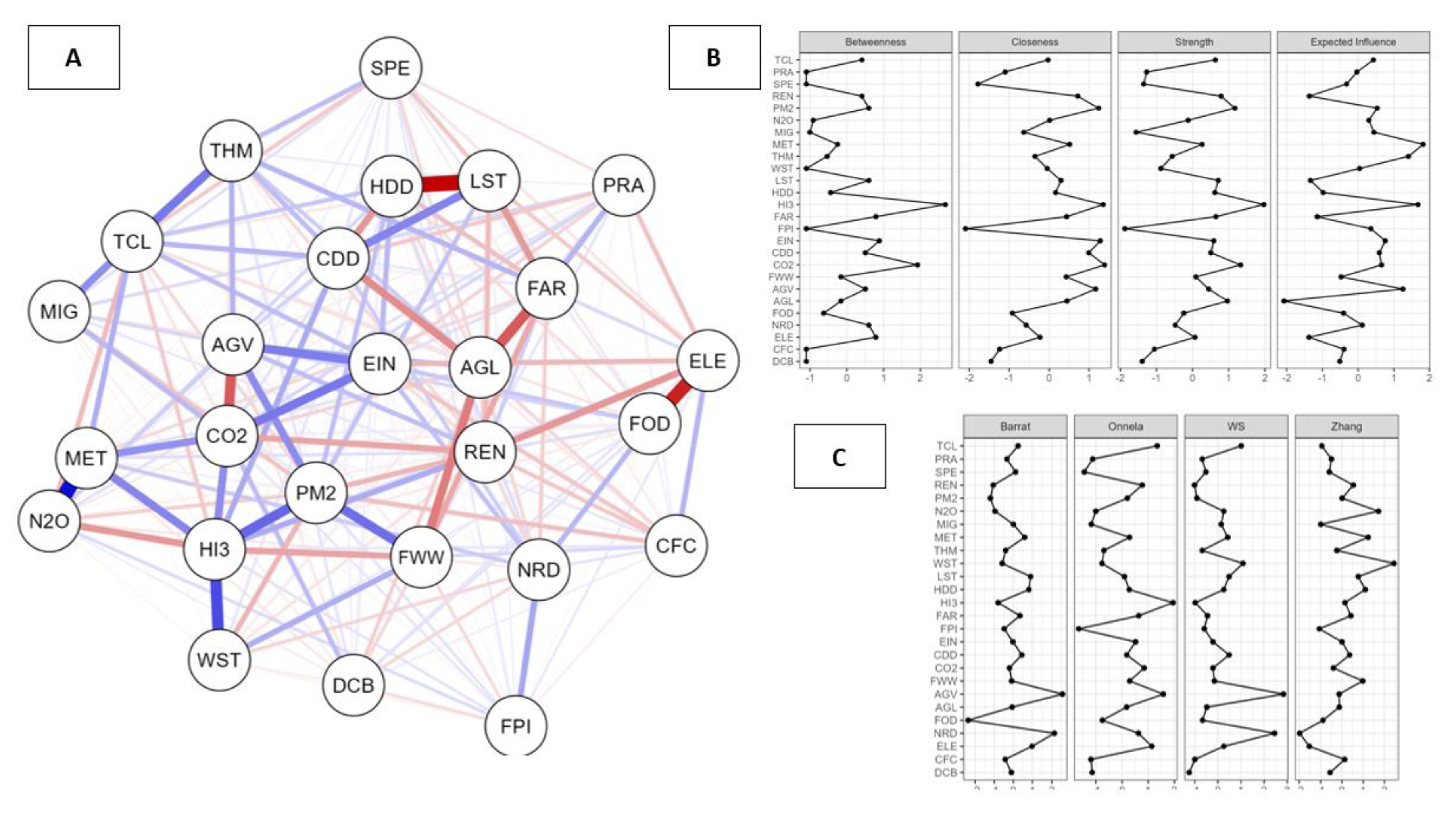

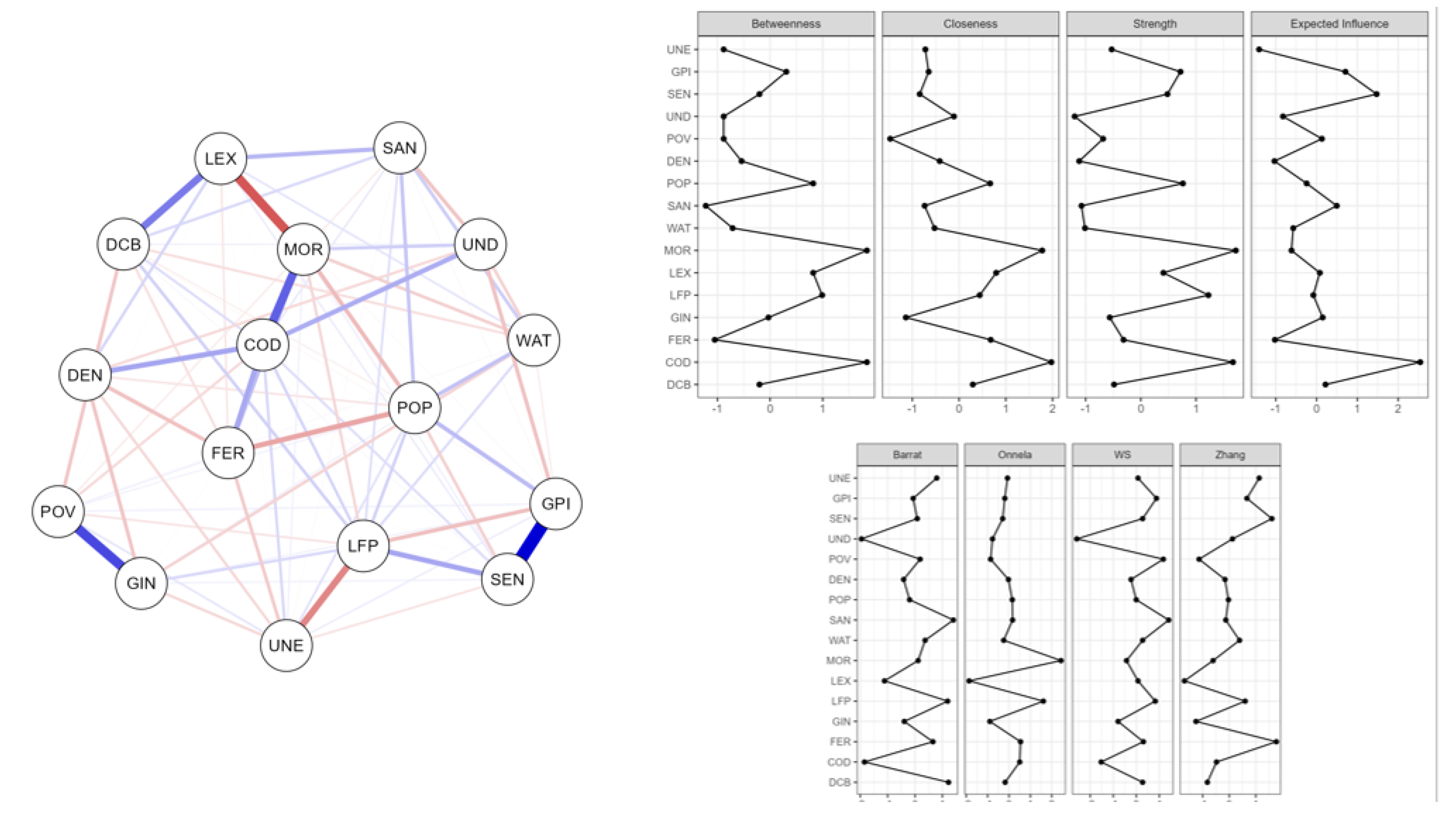

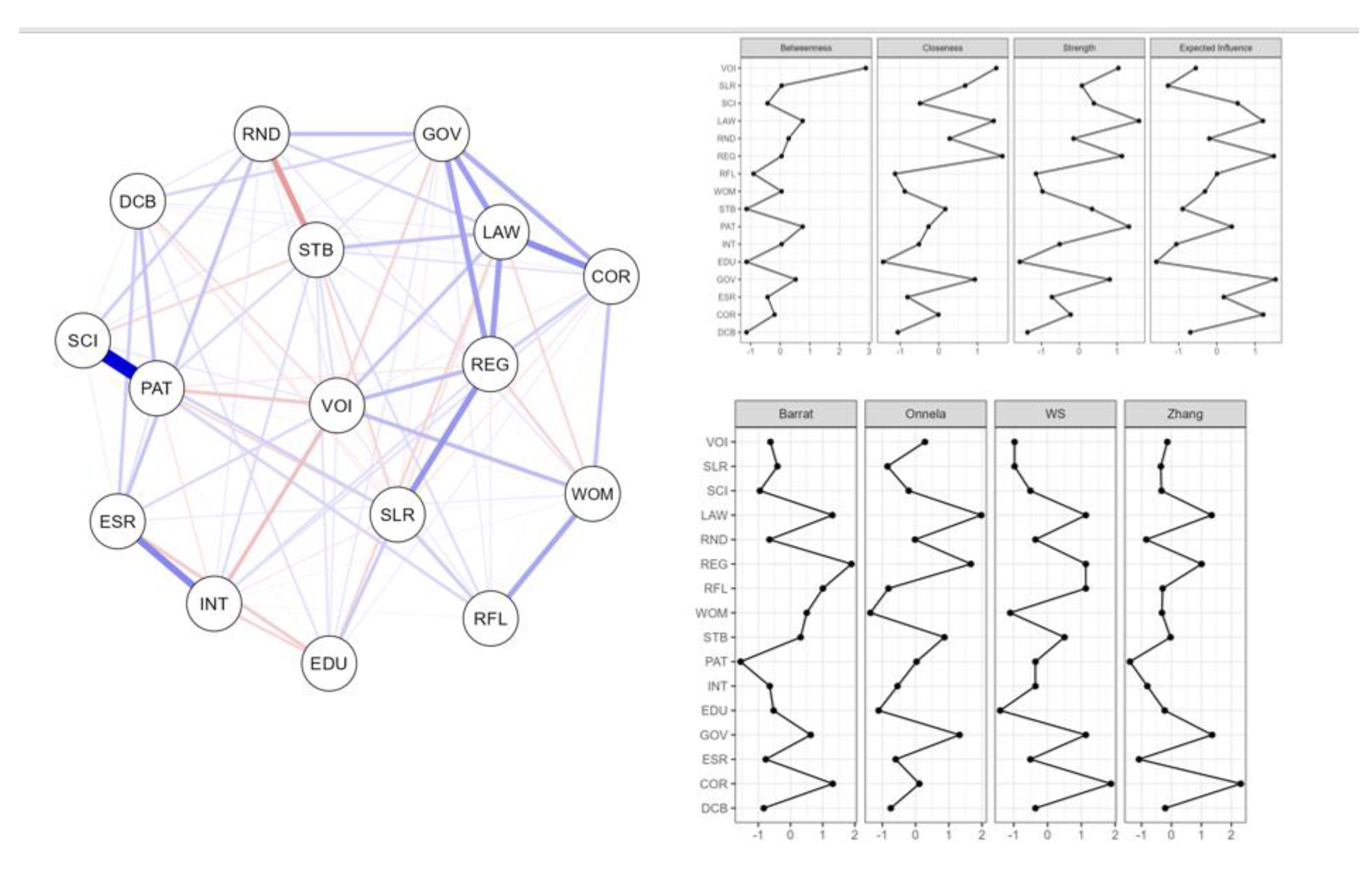

The network provides valuable information on the role and relationship between the variables related to the environment, climatic conditions, and resource issues and the Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB) variable. With 26 nodes, in which all represent DCB and the other 25 represent the environment, there are 257 edges, making the sparsity .209. The sparsity in this network, since it is quite low, confirms the high connectivity in the network. The network confirms that the different variables related to the environment form a complex network, in which most variables, even DCB, are interconnected. The high connectiveness in the network confirms that the development of the credit system operates in a complex environment. Several variables, such as those related to the use and development of the environment, like agricultural land (AGL), forest area, and tree cover loss depicted in TCL, are likely bound together. These factors ought to cause an end in the formation of greenhouse gases like CO₂, N₂O, and MET, and those under biodiversitpressure like THM, and agricultural productivity, such as AGV and FPI. All factors would form an important and smaller network. The climatic factors, like HDD, CDD, HI3, LST, and SPE, would likely connect in an important manner with the energy factors, such as EIN, REN, CFC, and ELE. All factors would act together, and this would be an important indication regarding the relationship and connection between energy and climatic factors. The factors related to water, like FWW and water stress depicted under the variable WST, would act together, and those related to the resource degradation, like NRD and FOD, would connect in an important manne. See

Table 13.

The centrality measures yield fine-grained insights into the individual contributions of each environmental factor across the entire connectivity and centrality map of the network for the node Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB). Variables with high betweenness values play an important role in bridging the gap between different environmental factors. With respect to this, HI3 (Heat Index 35) and the value of CO2 emissions are the highest, indicating that high heat stress and the effect of CO2 emissions play an important role in bridging the different environmental factors and act as important bridging nodes in this network. These variables also have the highest closeness centrality and strength centrality, signifying their dominance in the environment system influencing the financing outcomes. The variables with high strength centrality and expected influence represent the greatest direct connection. The HI3, MET (methane gas), and THM (threatened mammals) variables signify a strong positive expected influence. These variables represent the influential propagation through the network. Variables such as AGL (agricultural lands), REN (renewable energy), LST (land surface temperature), and ELE (electricity access) are expected to have a negative influence. The effects of increases in these variables tend to counteract environmental pressures. DCB has the lowest strength centrality and negative expected influence. These strength centrality and expected influence values indicate that the variables on the outcome side have weak connections in the environment network. DCB does not strongly feed back into the environmental factors. Instead, DCB is fed back through environmental factors indirectly. The rationale for this finding aligns with the argument that the enlarged financial system can impact and regulate environmental factors and financial performance in a counterintuitive way. In general, the network finds an important role for climate and CO2 factors, which act as the environmental-structural network driver. The variables related to land use and energy access play an important role in regulating the environmental network (

Table 14).

The weights matrix provides a complex representation of the partial correlations among the environment variables and the Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (DCB), adjusted for the remaining system. There are several important trends worth noting. First, DCB has its strongest negative linkages with CO2 emissions (-0.441), the food production index (FPI, -0.346), and forest area (FAR, -0.096), confirming the logic that the increased use of credit, the increased production of food, and the increased area of forests are related to lower access levels in the private credit market, when adjusted for the integrated environment. DCB shows a positive link with access to clean fuel sources (CFC, 0.184), suggesting that improvements in fuel quality and access could enable greater access within the financial system. There exists evidence supporting the logic that increased access levels positively improve access and stability levels in the financial system by facilitating increased productivity and reduced environmentally related risks and uncertainties related to the negative use and abuse of energy sources and related systems in the developing world, particularly in emerging markets and economies in the region, supporting the perspective approach proposed in the model architecture and application (Chen et al., 2024). Among the external variables, some interesting structures and linkages emerge. Some variables in the environment domain are strongly interlinked. The variables related to land use and agricultural factors are strongly grouped together. These include FOD–AGV (.362), AGV–CDD (.147), AGL–FOD (.177), and AGL–CDD (.072), and this indicates strongly structured relationships between the variables related to the use of the land, the levels of agricultural variables, the measures related to the depletion process, and the factors related to climatic conditions. The variables related to the water stress and climatic factors also have a strongly networked structure. These include CDD–FWW (-.587) and HDD–FAR (-.682), and these relationships show the structures in which the extreme factors related to climatic conditions strongly influence those related to water and vegetation. In the group related to emissions, the variables are strongly linked, including those related to energy and water. These include MET-EIN (.238) and PM2–WST (.299), and these factors strongly show the relationship In sum, the matrix evidences the strongly interconnected nature of the environment, in which DCB responds much more strongly to generalised pressures related to the environment, such as emissions, energy, and the use of the land, than it does to isolated environment factors (

Table 15).

The figure below provides a rich representation of the network structure connecting the indicator 'Domestic Credit to the Private Sector' to the DCB and 25 environment-linked variables. In the network, PA, the DCB indicator plays a peripheral role, indicated by light-blue edges. These edges reveal that the DCB lacks direct network impact and instead copes with the environment through an indirect network process. This observation confirms the theory supporting the forthcoming discovery that the Finance Sector tends to respond indirectly to environment-induced changes rather than the other way around, as shown in the paper 'Ceglar et al., 2025.' The red edges in the network represent positive connections, and the blue edges represent negative connections, with thickness indicating intensity. The red network connections, such as HDD-LST, HI3-LST, and AGL-FAR, reflect the positive relationship between the climatic factors and the environment. Similarly, the negative environment factors include connections such as CDD-FWW and MET-N

\(_2

\), as well as the remaining edges in the network, like the WST-HI3 factors.

Figure 2, Panel B, provides an overall snapshot of the four centrality measures—betweenness, closeness, strength, and expected influence—to identify the variables that play pivotal positions in the network. HI3 and CO2 have high betweenness, making them pivotal bridges where almost all the environmental factors converge. PM2, EIN, and CDD also have high values for closeness and strength, underscoring the importance of energy intensity, pollution, and climatic factors in the environment and credit system. AGL, REN, ELE, and FPI, on the other hand, have lower centrality measures and negative expected influence values (

Figure 3).

4. Integrating Social Sustainability into ESG: Demographic, Economic, and Environmental Drivers of Financial Inclusion

The role of S – Social in the ESG framework has become even more important in understanding the interlinkages among social welfare, economic, and sustainable development factors in the broader environment (Gernego et al., 2024). The S factor corresponds to the people-oriented dimension of sustainable development, prioritizing inclusivity, access to resources, and social equity. This dimension, in fact, turns out to be the most intricate and complex among the other factors included in the ESG framework, demanding a multidimensional approach in methodology, including variables related to demography, economics, environment, and institutions in the process (Raghavan, 2022). By considering factors related to social and ecological systems, researchers can better understand the link between people's development and the financial and environmental systems in which they operate, achieving a broader perspective on sustainable development (Keeley et al., 2022). The foundation upon which this assessment rests is the use of the “Domestic Credit to the Private Sector by Banks” (DCB) indicator and its role as a proxy for the process and extent of financial inclusion and economic empowerment. The accessibility and use of domestic credit help measure the financial system's ability and role in supporting and engaging households and businesses in investment, consumption, and employment. In most economies, the use and access to credit play pivotal roles in the process and aim of ensuring poverty reduction, encouraging and developing entrepreneurship, and facilitating and achieving social inclusion, all of which are basic and essential components of the Social dimension. Additionally, access and use of finances correlate and relate heavily in measuring the ability and role played by the social and communal entities in coping with the external environment and climatic changes, such as those related to environmental degradation and climatic conditions, such as those social and communal aspects assessed and measured under Adambekov et al., 2023. This financial dimension could be supplemented by socioeconomic factors such as Population aged 65 and over (POP), Poverty headcount ratio (POV), and Unemployment rate (UNE), which reflect the characteristics of social systems. The proportion of the elderly in the Population (POP) emphasizes the pressures exerted on the labor force, the health sector, and the social protection framework. In an aging society, an increasing proportion of dependents puts pressure on finances and raises risks, making financial inclusion and equity across generations important social issues. The Poverty headcount ratio (POV) measures the direct percentage of people living below the national poverty line, an important indicator reflecting social inequalities and welfare. On the other hand, the Unemployment rate (UNE) measures the effectiveness of the labor markets and the extent to which the economic development process has been inclusive. These three variables offer insight into how the social sustainability of a nation's development path has been influenced by demographic changes, distribution, and labor conditions. The access variables, namely Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (CFC) and Access to electricity (ELE), imply an extension of the Social dimension into the domain of infrastructure and the environment. Universal access to modern energy services has come to be regarded as a foundation of sustainable development and equity. Inappropriate access to modern energy services exacerbates health, gender, and education inequalities in developing countries, in particular (Lee, Choi, Roh, Lee, & Um, 2022). These variables, hence, imply access outcomes that are technological on the one hand and equitable on the other. The incorporation of the environmental resource variables, like the adjusted savings variables Natural Resources Depletion (NRD), Net Forestry Depletion (FOD), Agricultural Land (AGL), Gross/Freshwater Withdrawals, Agricultural/Fisher Resources, and Level of Water Stress (WST), recognizes the interconnectedness of social welfare and the environment. The destruction of the environment has direct effects on people’s livelihoods, diets, and migrations. In this regard, environmental destruction affects people through displacement, unemployment in rural areas, and increased income inequality. In effect, environmental destruction becomes a factor in social vulnerability rather than just an environmental one (Keeley et al., 2022). Climate and pollution proxy measures like Carbon Dioxide Emission (CO2), Methane concentrations (MET), Nitrous Oxide levels (N2O), PM2.5 air quality pollution measures (PM2), and temperature-associated factors like Heat Index measures (HI3), Heating Degree-Days measures (HDD), and Land Surface Temperature measures (LST) further highlight the social dimension. These measures reflect the health and environmental aspects of social sustainability, as air pollution and climate change have severe effects on lower socioeconomic groups (Kwiński et al., 2023). By considering all the measures together, the social performance cannot be disentangled from the environment. Finally, governance factors, such as Regulatory Quality (REG), and sustainable factors, such as Renewable energy consumption (REN) and Terrestrial and marine protected areas (PRA), highlight the regulations and sustainable factors that impact social outcomes. Successful regulation and protection of the environment are important for ensuring resource equity and preventing conflicts over water and land, among other factors that may create an unstable social environment (Raghavan, 2022; Lee et al., 2022). In other words, given the variables considered, the integration framework provides a means to analyze the Social factor in ESG issues. The reasoning underscores that the social well-being factor does not occur in a bubble; other factors are involved in the dynamic process, namely finance, demography, the environment, and governance. Through the framework, the effect that Domestic Credit to the Private Sector has on the social and financial systems in relation to the environment can be better understood, and insights can be provided on the framework for designing sustainable economic policies (

Table 16).