Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

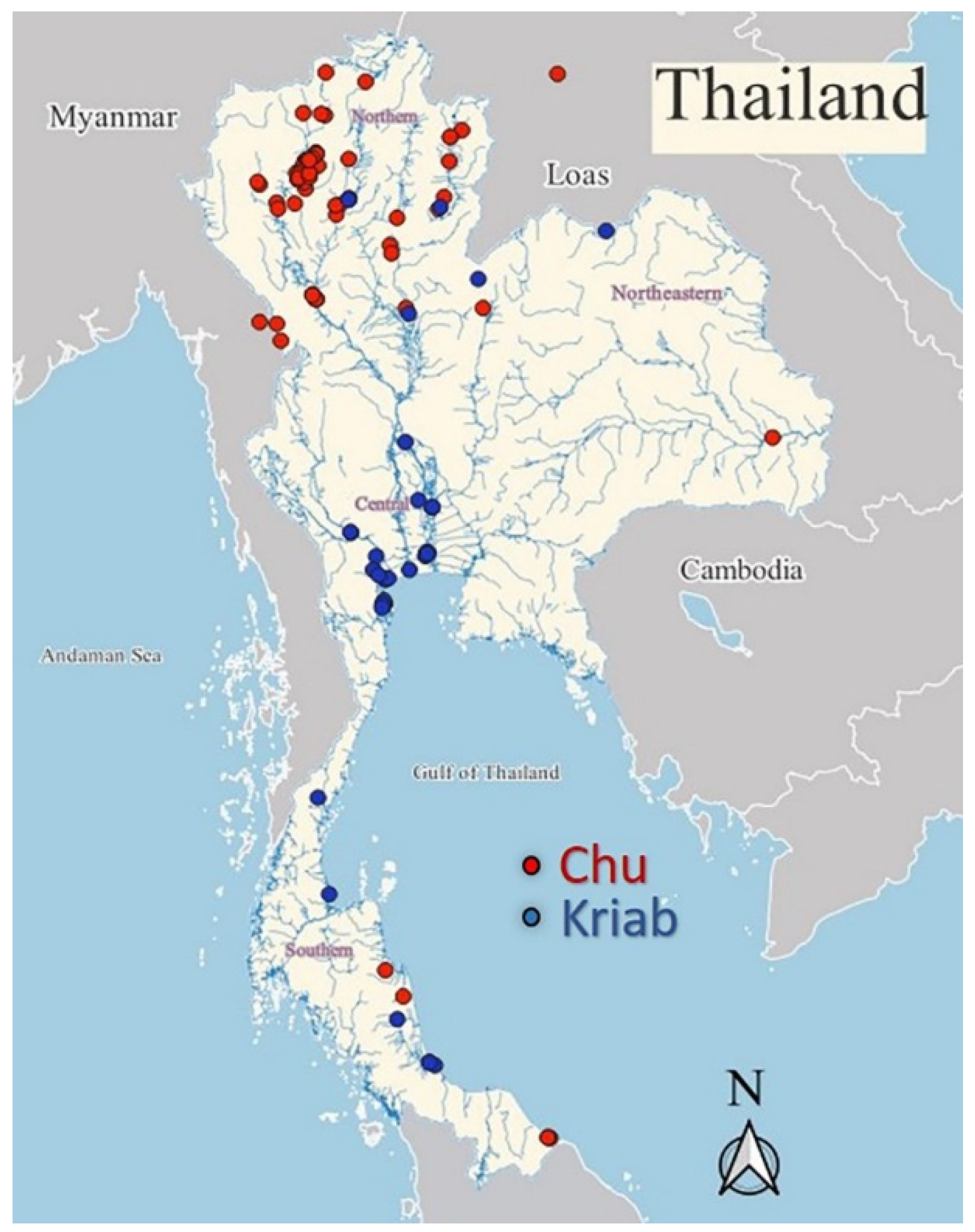

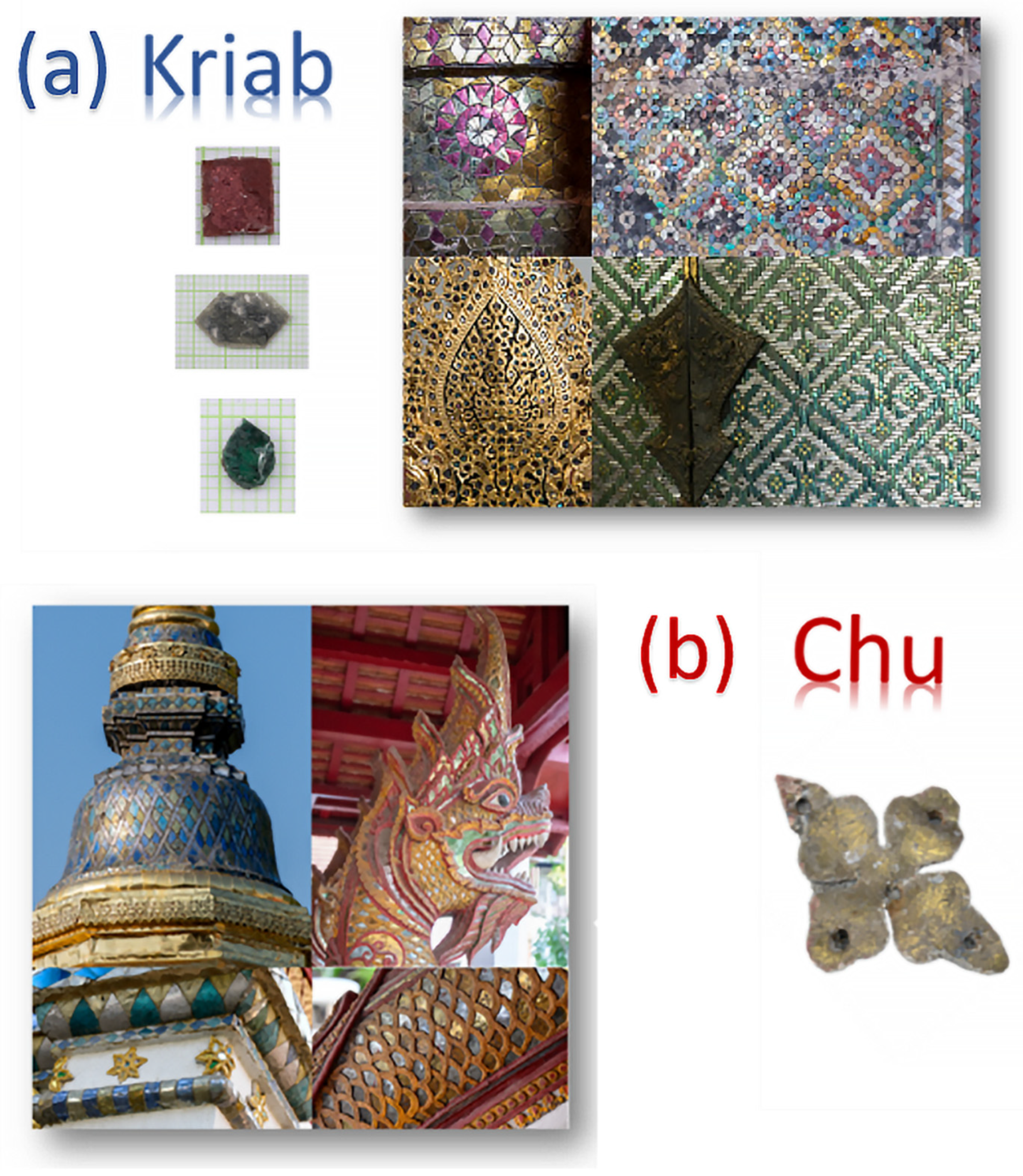

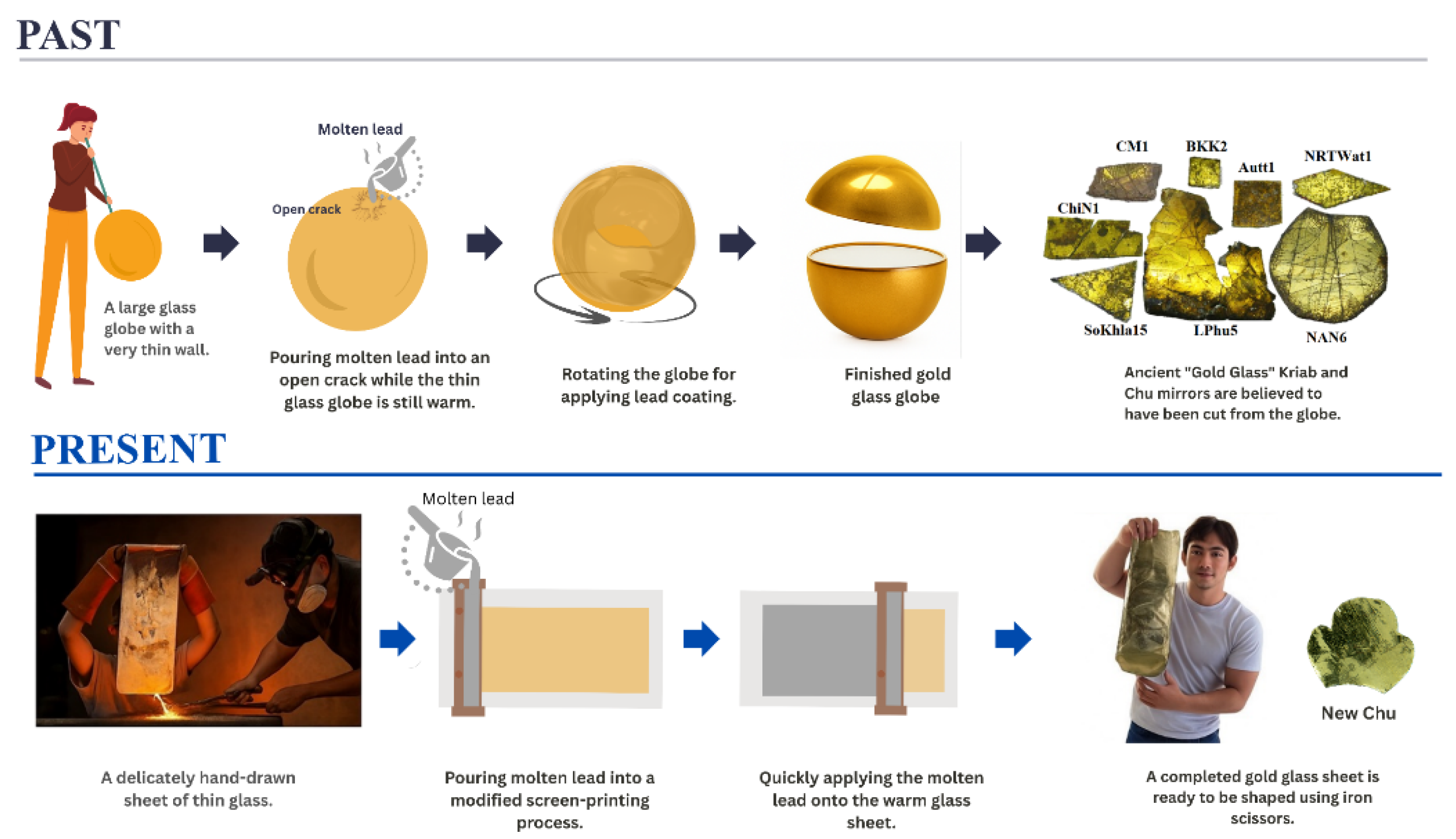

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

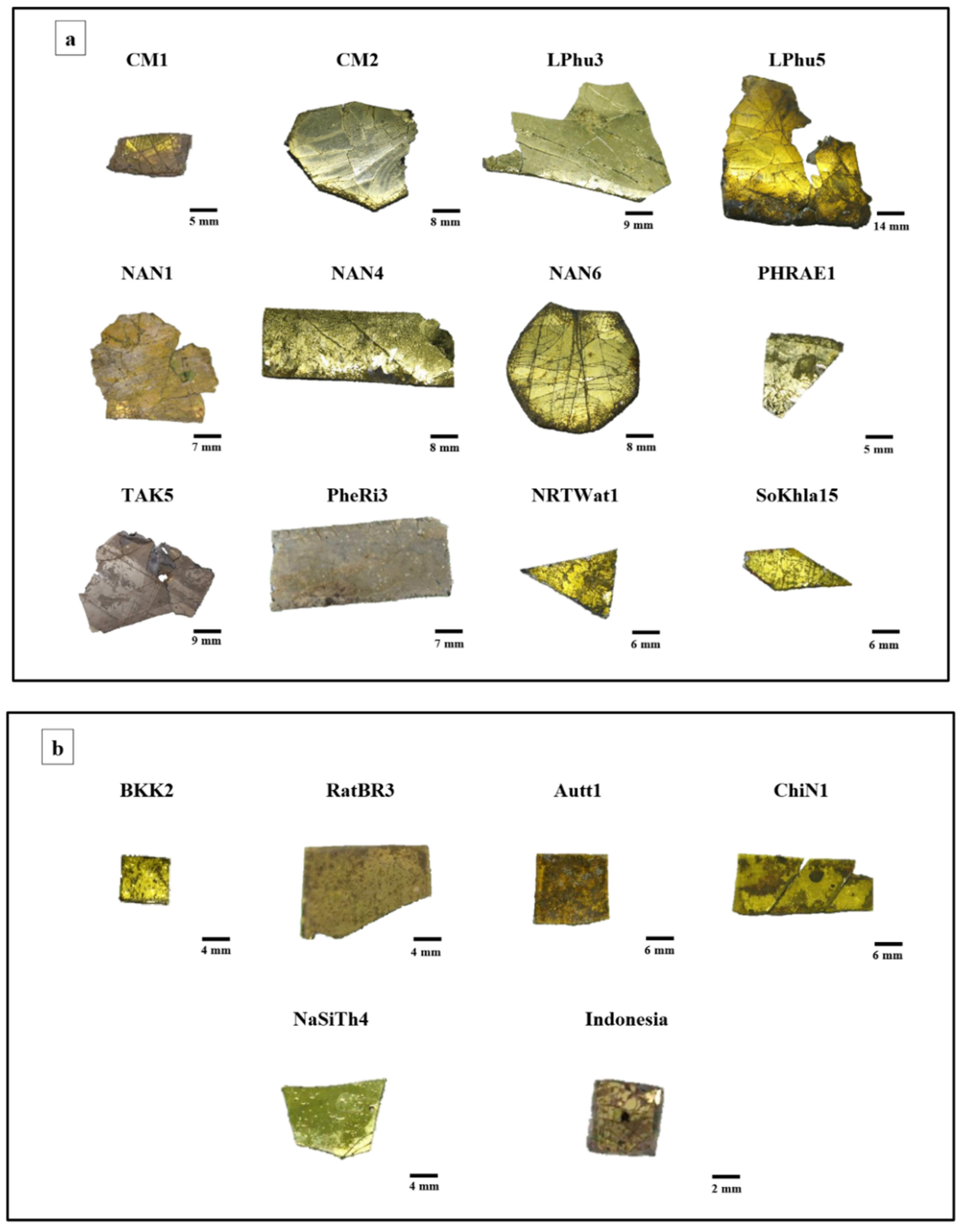

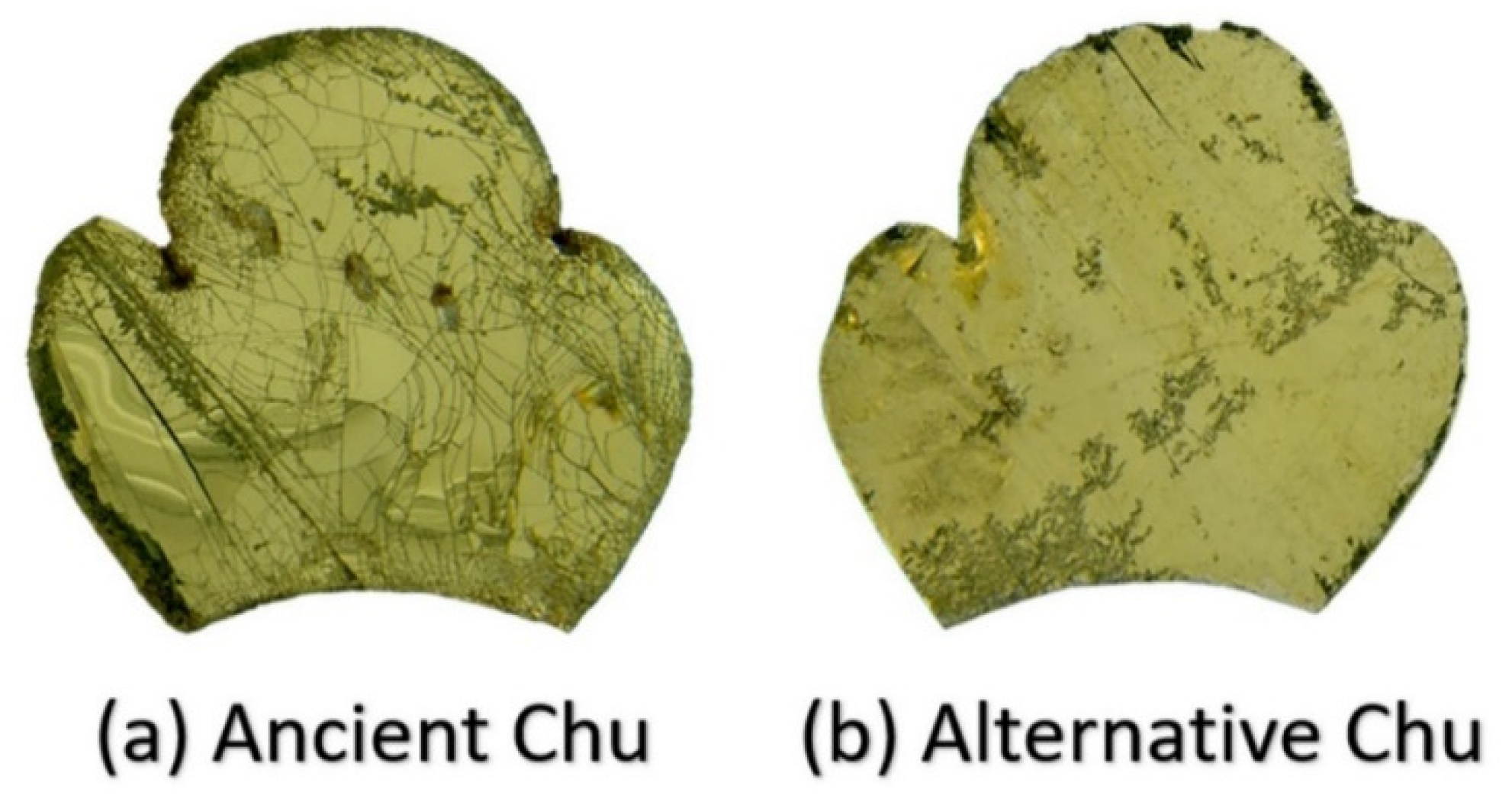

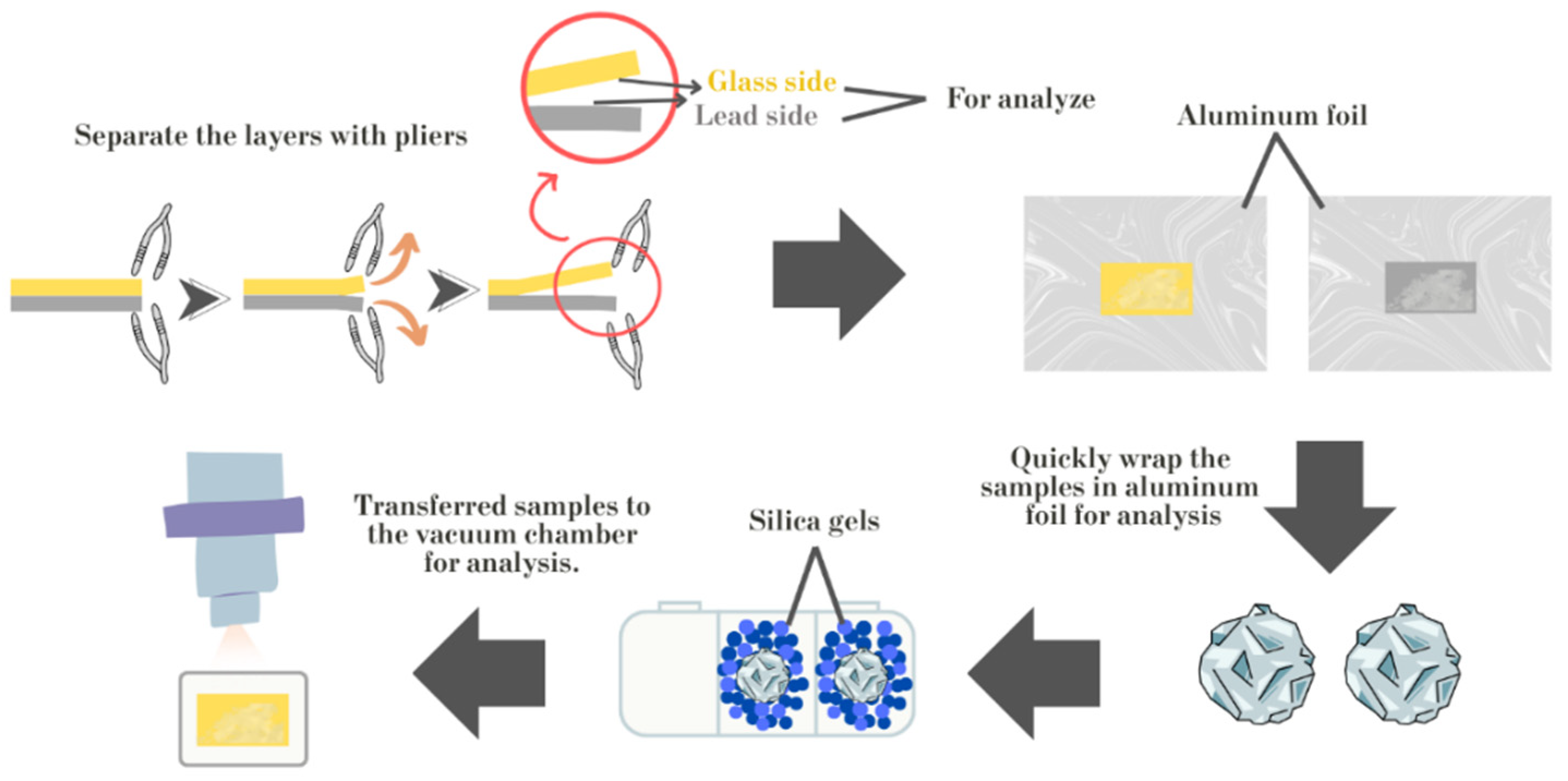

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.2.1. Wavelength Dispersive Spectroscopy (WDS)

2.2.2. Handheld/Portable X-Ray Fluorescent Spectrometers—PXRF

2.2.3. High-Performance Wavelength Dispersive XRF Spectrometer: WD-XRF

2.3. Characterization of Glass-Lead Interface

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy- and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM- EDS)

2.3.2. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

3. Results and Discussion

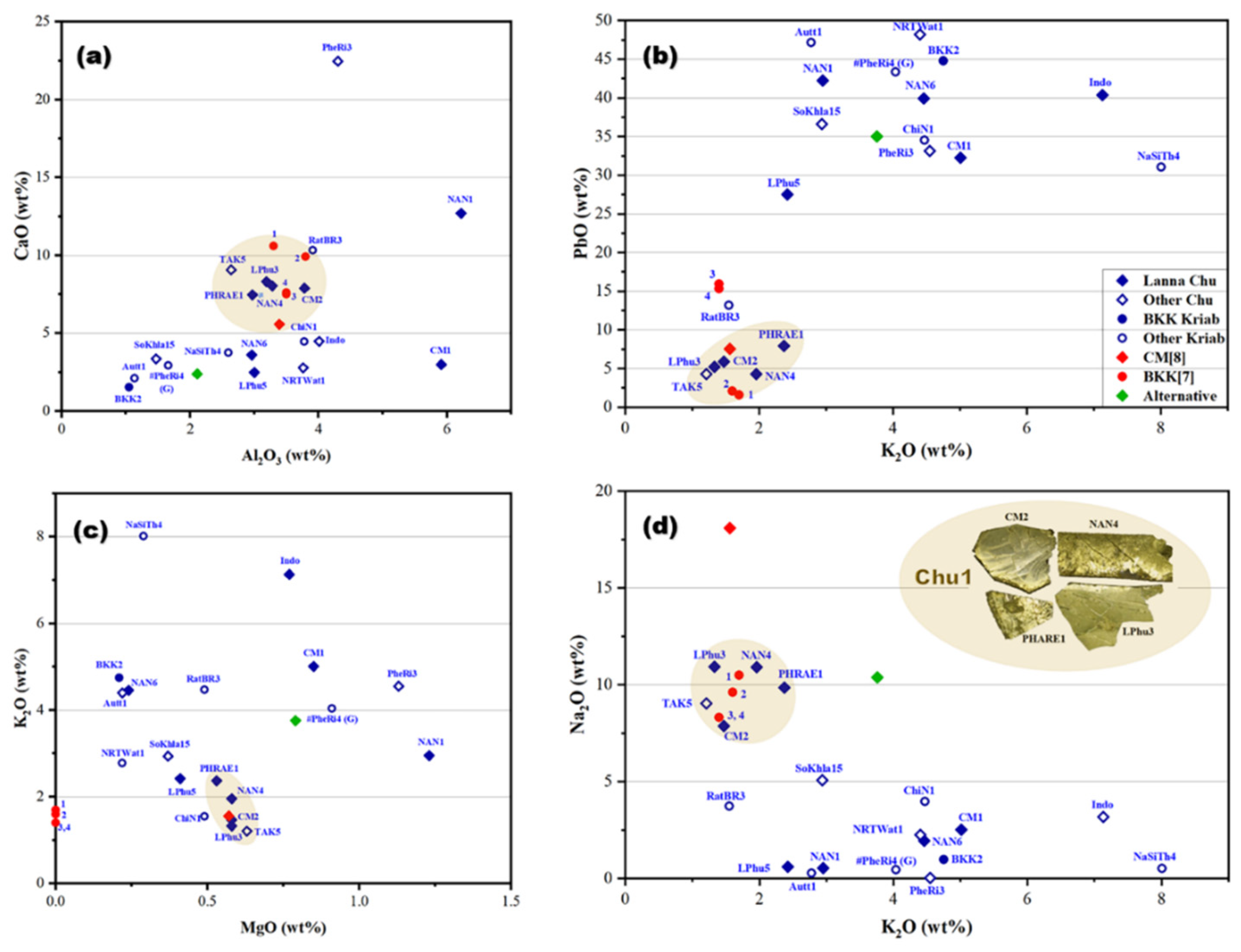

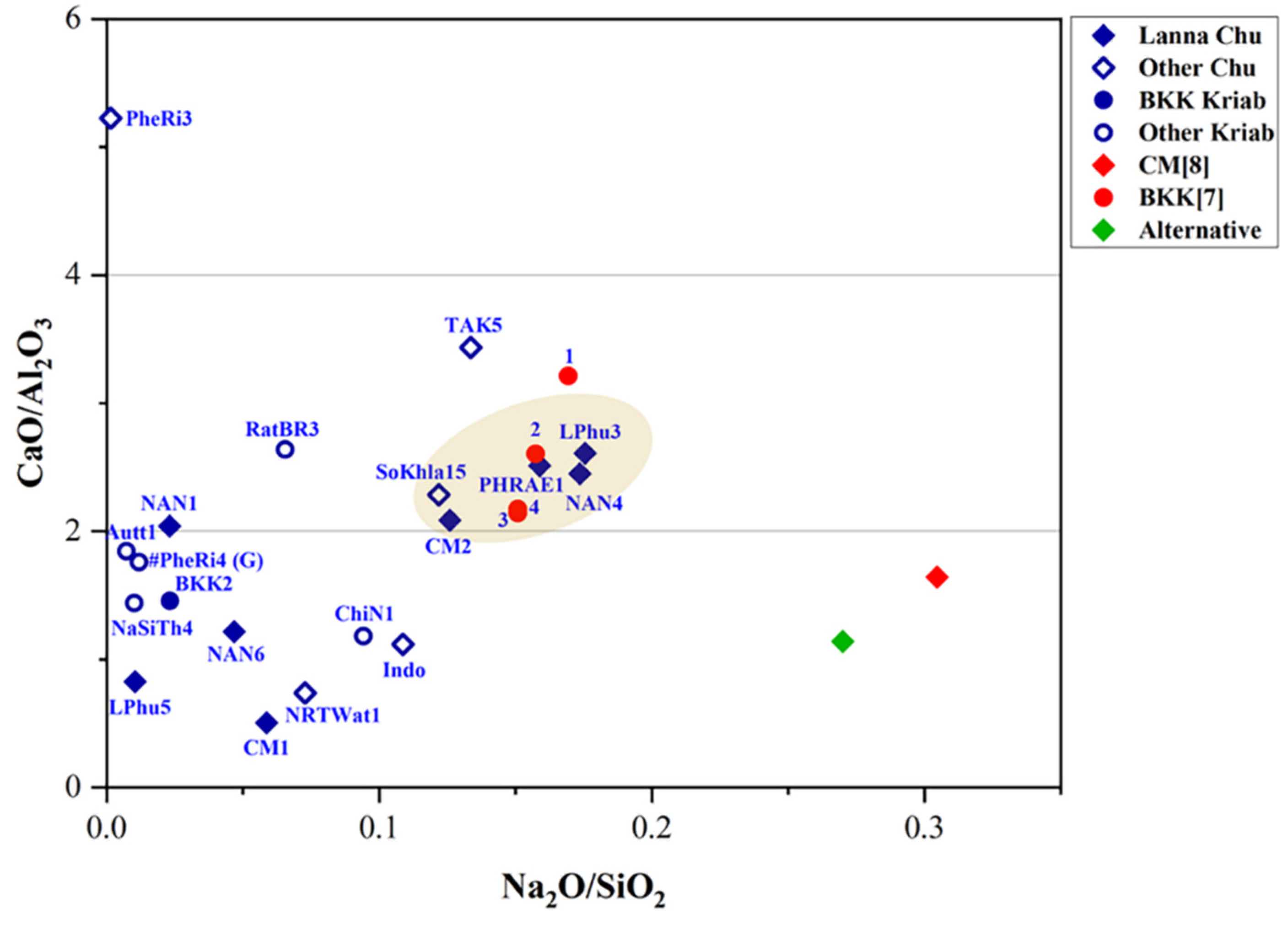

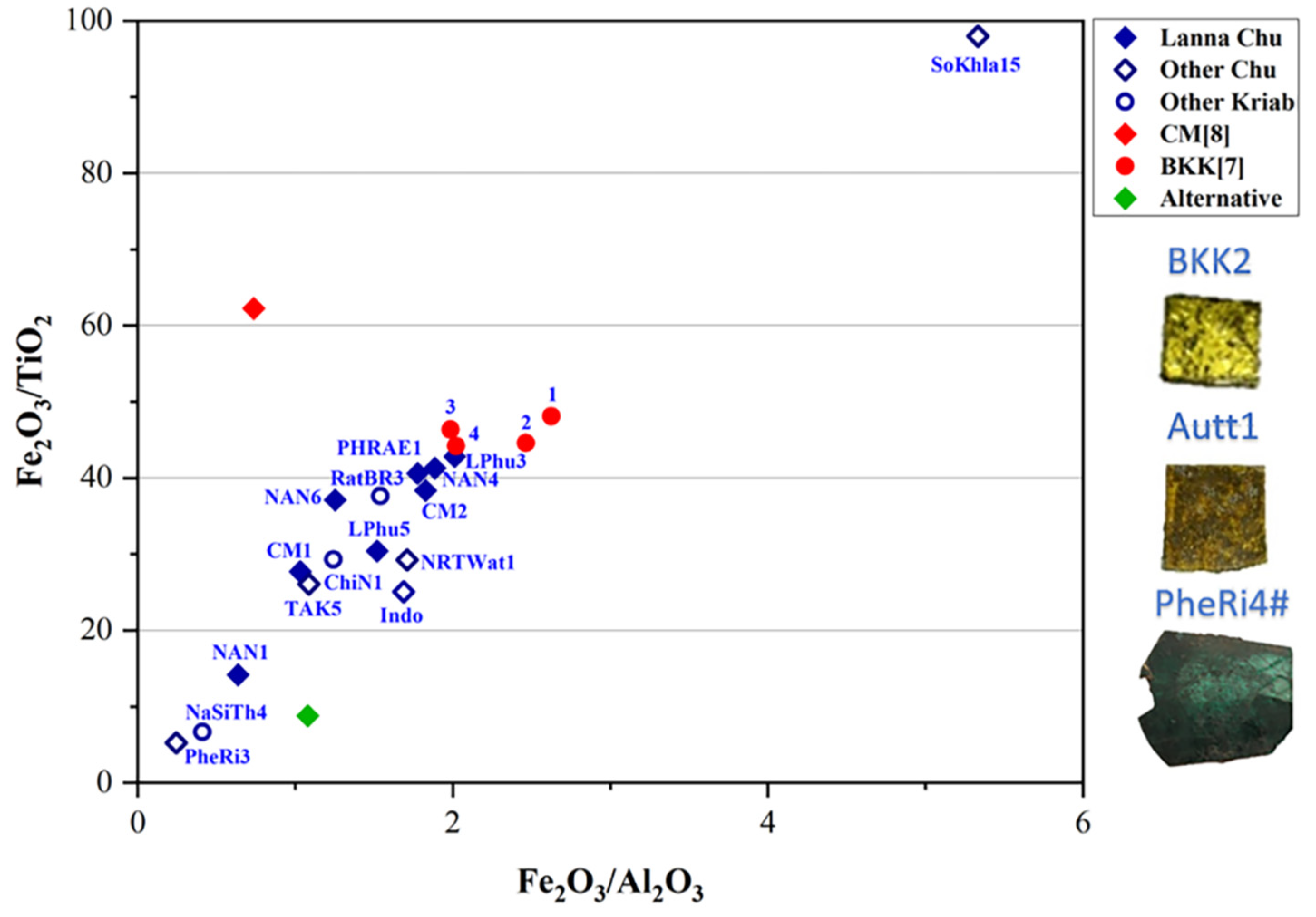

3.1. Chemical Analysis of Yellow Glass Layers

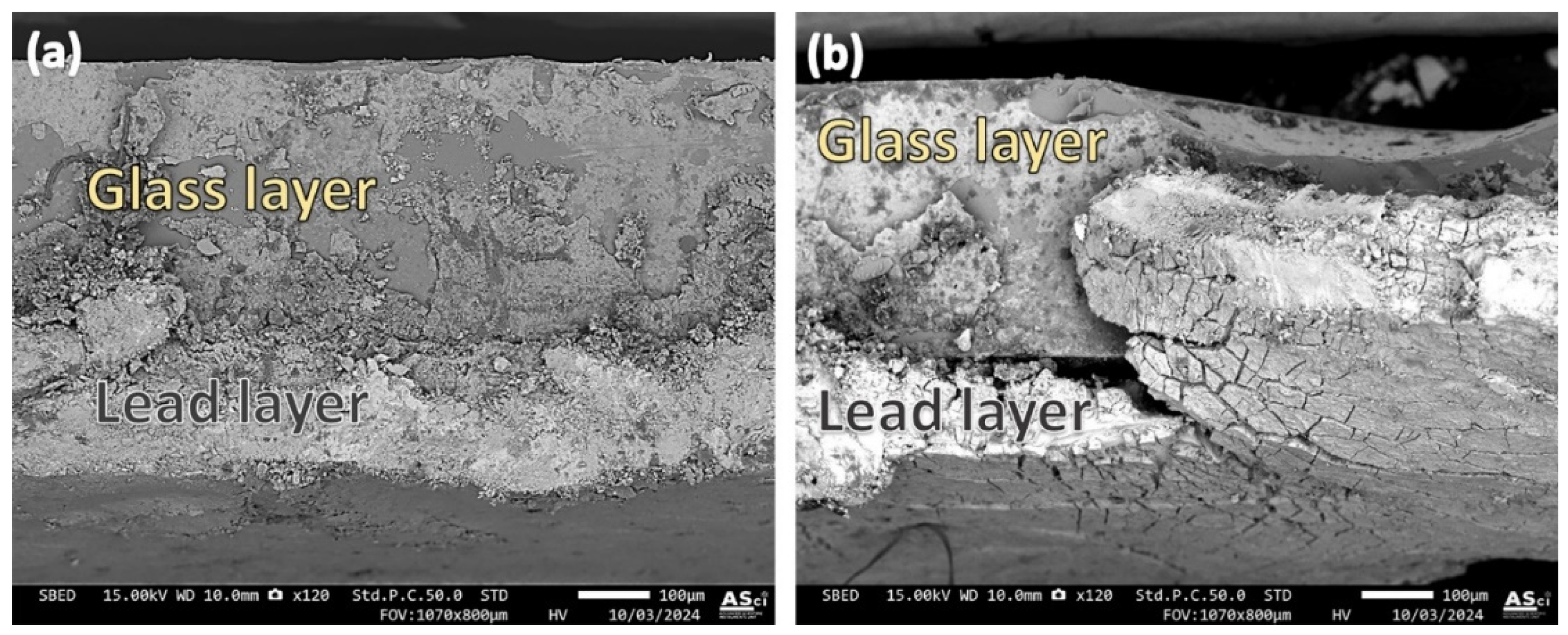

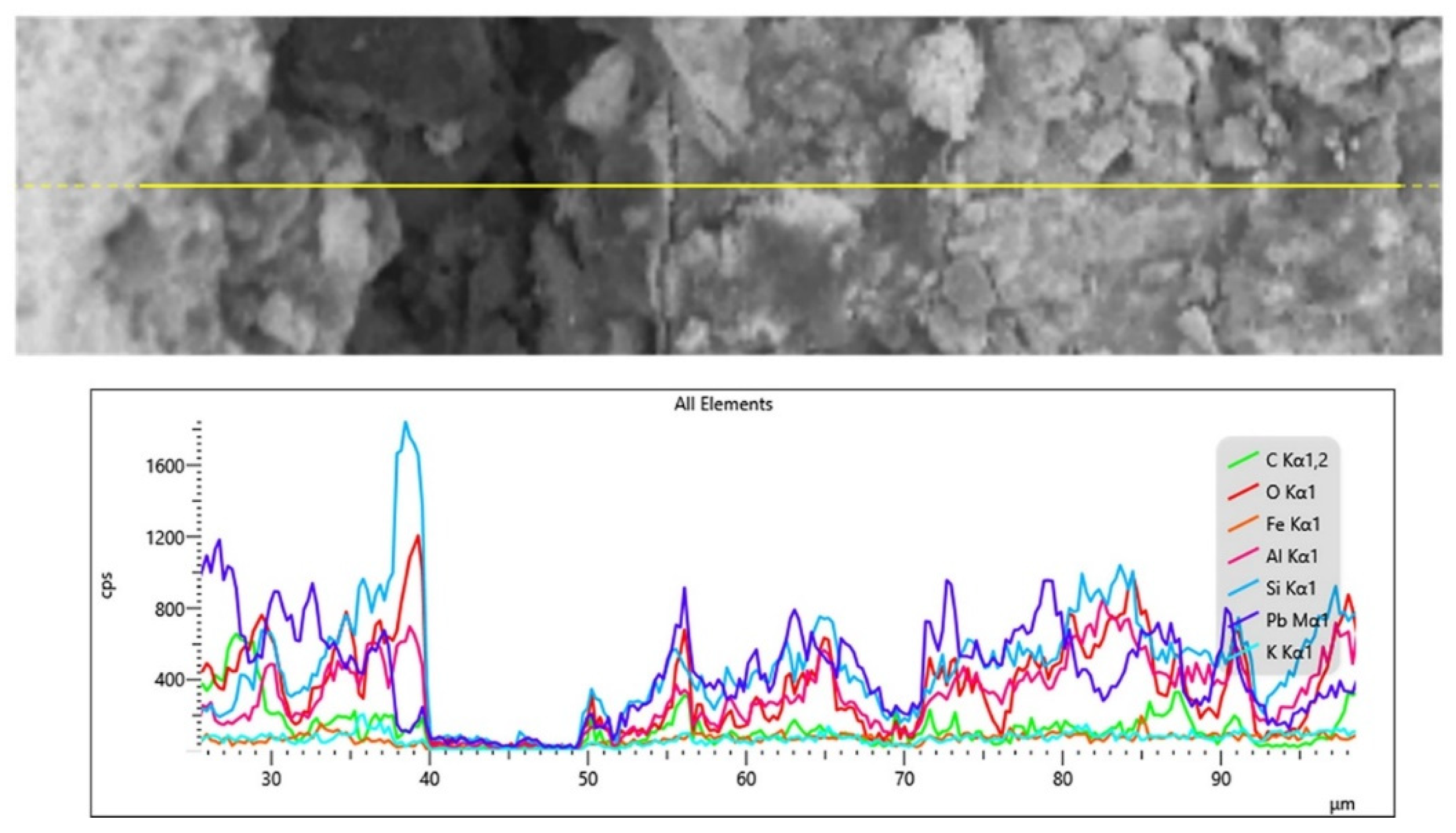

3.2. Microstructural Analysis at the Glass-Lead Interface

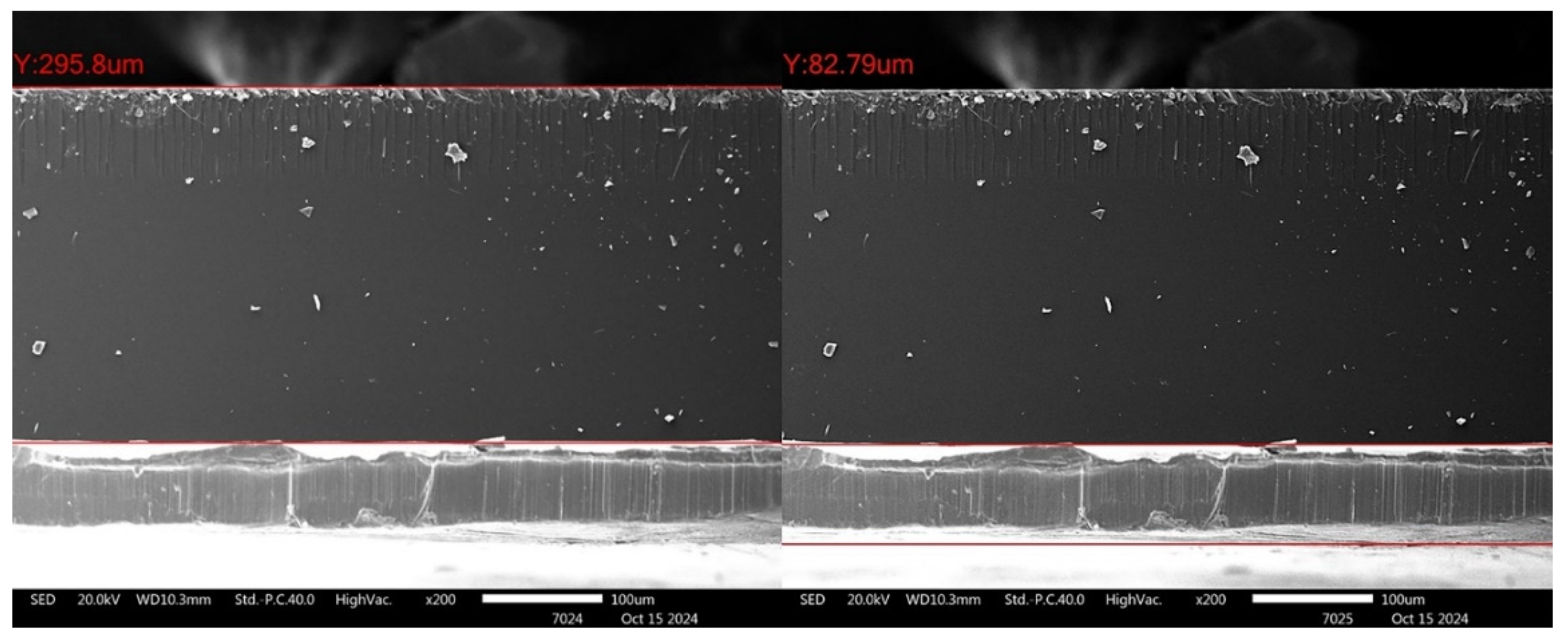

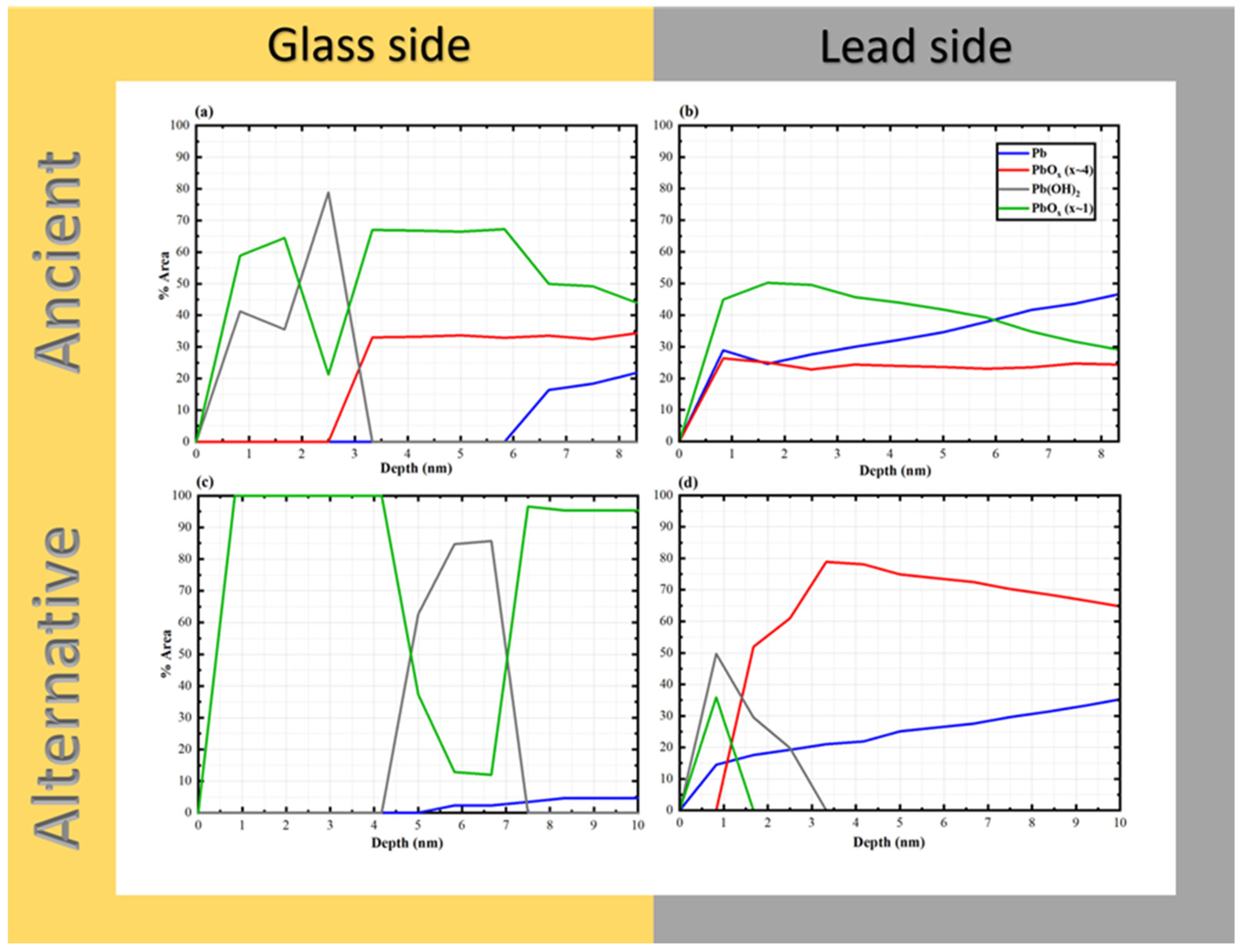

3.3. Depth Profile Analysis of Glass and Lead Interfacial Surfaces by XPS

| Chemical state | Binding energies of Pb (eV) Pb7/2 Peaks |

|---|---|

| PbO4 | 137.8-138.3 |

| Pb0 | 136.3-137.0 |

| PbO | 138.6-139.1 |

| Pb (OH)2 | 138.2-138.8 |

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Bellina-Pryce, B., Silapanth, P., 2006. Weaving cultural identities on trans-Asiatic networks: Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula - an early socio-political landscape. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. 93, 257-293. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43734048.

- Glover, I.C., 1990. Early trade between India and Southeast Asia– A Link in the Development of a World Trading System, Occasional Paper 16 (2nd ed.), University of Hull Centre for South-East Asian Studies, Hull, pp. 1-45.

- Lankton, J.W., Dussubieux, L., 2013. Early glass in southeast Asia. in Janssens, K. (ed.) Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 415-443. [CrossRef]

- Won-in, K., Thongkam, Y., Pongkrapan, S., Intarasiri, S., Thongleurm, C., Kamwanna, T., Leelawathanasuk, T., Dararutana, P., 2011. Raman spectroscopic study on archaeological glasses in Thailand: ancient Thai glass. Spectrochim. Acta - A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 83 (1), 231-235. [CrossRef]

- Won-In, K., Dararutana, P., 2018. Elemental distribution of the greenish-Thai decorative glass. J Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1082, 012084. [CrossRef]

- Klysubun, W., Hauzenberger, C. A., Ravel, B., Klysubun, P., Huang, Y., Wongtepa, W., & Sombunchoo, P., 2015. Understanding the blue color in antique mosaic mirrored glass from the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Thailand. X-Ray Spectrom. 44 (3), 116-123. [CrossRef]

- Klysubun, W., Ravel, B., Klysubun, P., Sombunchoo, P., Deenan, W., 2013. Characterization of yellow and colorless decorative glasses from the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Bangkok, Thailand. Appl Phys A. 111 (3), 775-782. [CrossRef]

- Ravel, B., Carr, G., Hauzenberger, C.A., Klysubun, W., 2015. X-ray and optical spectroscopic study of the coloration of red glass used in 19th century decorative mosaics at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. J. Cult. Herit. 16, 315-321. [CrossRef]

- Ounjaijom, T., Intawin, P., Kraipok, A., et al. 2023. Chemical and Mechanical Characterization of the Alternative Kriab-Mirror Tesserae for Restoration of 18th to 19th-Century Mosaics (Thailand). Materials 2023. 16 (9), 3321. [CrossRef]

- Eggert, G., Andrea, A. F., Mirrored with molten lead: Convex mirror glass through the ages. In Working Towards a Sustainable Past. ICOM-CC 20th Triennial Conference Preprints, Valencia, 18-22 September 2023, ed. J. Bridgland. Paris: International Council of Museums.

- Keller, D., 2006. Antikes Glas. By Axel von Saldern. 250mm. Pp xxv + 708, ills. Munich: C H Beck, 2004. The Antiquaries Journal. 86, 427 - 428. [CrossRef]

- Kock, J., Sode, T., 2002. Medieval glass mirrors in Southern Scandinavia and their technique, as still practiced in India. Journal of Glass Studies. 44, 79-94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24190873.

- Carmona, N., Villegas, M.A., Jiménez, P., Navarro, J., García-Heras, M., 2009. Islamic glasses from Al-Andalus. Characterisation of materials from a Murcian workshop (12th century AD, Spain). Journal of Cultural Heritage. 10 (3), 439-445. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, I., 1990. Glasspiegel im Mittelalter - Fakten. Funde Fragen. Bonner Jahrbücher. 233-313. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, I., 1995. Glasspiegel im Mittelalter II - Neue Funde und neue Fragen. Bonner Jahrbücher. 209-248. [CrossRef]

- Ostapkowicz, J., 2013. ‘Made … with admirable artistry’: The context, manufacture and history of a Taíno belt. The Antiquaries Journal. 93, 287-317. [CrossRef]

- Ilardi, V., 2007. Renaissance vision from spectacles to telescopes. American Philosophical Society. 259, pp. 378.

- Liebig, J., 1856. Ueber Versilberung und Vergoldung von Glas. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 98 (1), 132-139. [CrossRef]

- D-Library|National Library of Thailand. Available online: http://164.115.27.97/digital/items/show/4961 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Gratuze, B., 2013. Provenance Analysis of Glass Artefacts, in Janssens, K. (ed.) Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 312-343. [CrossRef]

- Billaud, Y., Gratuze, B., 2002. Les perles en verre et en faïence de la Protohistoire française. Matériaux, Productions, Circulations du Néolithique à l’Âge du bronze. Errance, Paris, pp. 193-212.

- Sayre, E.V., 1964. Some ancient glass specimens with composition of particular archaeological significance. Brookhaven National Laboratory B.N.L., 879, (T-534). Upton, New-York.

- Lilyquist, C., Brill, R. H., Wypyski, M. T., 1993. Studies in early Egyptian glass. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, pp. 1-80.

- Barrera, J., Velde, B., 1989. A study of French medieval glass composition. Journal of glass studies. 31, 48-54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24190095.

- Henderson, J., 1988. Electron probe microanalysis of mixed-alkali glasses. Archaeometry. 30 (1), 77-91. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, G., Kappel, I., Grote, K., Arndt, B., 1997. Chemistry and technology of prehistoric glass from Lower Saxony and Hesse. Journal of Archaeological Science. 24 (6), 547-559. [CrossRef]

- Brill, R. H., 1992. Chemical analysis of some glass from Frattesina. Journal of Glass Studies. 34, 11-22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24190975.

- Shortland, A. J., Tite, M. S., 1998. The interdependence of glass and vitreous faience production at Amarna. in Ceramics and Civilization, 8 (eds P. McCray and W.D. Kingery), American Ceramic Society, Westerville, Ohio, pp. 251-265.

- Francis, P. Jr., 2002. Asia’s Maritime Bead Trade. 300 B.C. to the Present., University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu.

- Sablerolles, Y., Henderson, J., Dijkmann, W., 1997. Early medieval glass bead making in Maastricht (Jodenstraat 30), the Netherlands: an archaeological and scientific investigation. in Perlen Archäologie, Techniken, Analysen (eds. U. von Freeden and A. Wieczorek), Habelt, Bonn (DEU), Germany, pp. 293-313.

- Tite, M., Pradell, T., Shortland, A., 2008. Discovery, production and use of thin-based opacifiers in glasses, enamels and glazes from the late iron age onwards: a reassessment, Archaeometry. 50 (1), 67-84. [CrossRef]

- Brill, R. H., 1999, Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses, The Corning Museum of Glass, New York.

- Fuxi, G., 2009. Origin and Evolution of Ancient Chinese Glass, Ancient Glass Research along the Silk Road (eds G. Fuxi, R.H. Brill and T. Shouyun), World Scientific Publ., New Jersey. pp. 1-40.

- Koezuka, T., 1997. Scientific study of evolution of ancient glasses found in Japan. Ph.D. Thesis, Tokyo University of the Arts (in Japanese).

- Mecking, O., 2013. Medieval lead glass in central Europe. Archaeometry. 55 (4), 640-662. [CrossRef]

- Téreygeol, F., Gratuze, B., Foy, D., Lancelot, J., 2004. Les scories de plomb argentifère: une source d’innovation technique carolingienne?. Cahiers d’histoire et de philosophie des sciences (eds N. Coquery, L. Hilaire-Perez, L. Sallmann and C.Verna), ENS e’ditions, SFHST, 52, 31-40.

- Brain, C., Brain, S., 2003. John Greene’s Glass Designs 1667-167. Annales du 16e Congres de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre, 263-266.

- Follmann-Schultz, A.-B., 1988. Die römischen Gläser aus Bonn. Köln: Rheinland-Verlag. 46.

- H. Ma, J. Henderson, Y. Sablerolles, S. Chenery and J. Evans. 2023. Early medieval glass production in the Netherlands: a chemical and isotopic investigation, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amersfoort, 191.

- Bellina-Pryce, B. and Silapanth, P. 2006, Weaving cultural identities on trans-Asiatic networks: Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula - an early socio-political landscape. Bulletin de l’Ecole Franc¸aise d’Extrˆeme-Orient, 93, 257-293.

- T. Palomar, J. Mosa, M. Aparicio. 2020, Hydrolytic resistance of K2O–PbO–SiO2, glasses in aqueous and high-humidity environments. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 103, 5248–5258. [CrossRef]

- P.W. Wang and L. Zhang. 1996, Structural role of lead in lead silicate glasses derived from XPS spectra, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 1996, 194, 129-134. [CrossRef]

- H. Morikawa, Y. Takagi, H. Ohno. 1982, Structural Analysis of 2PbO·SiO2 glass, J, Non. Cryst. Solids. 53, 173-182. [CrossRef]

- A. Khanna, A. Saini, B. Chen, F. Gonzalez, B. Ortiz. 2014, Structural characterization of PbO–B2O3–SiO2, Phys. Chem. Glasses: Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. B, 55 (2), 65–73.

- M.L. Hair. 1975, Hydroxyl Groups on Silica Surface, J, Non. Cryst. Solids., 19, 299-309. [CrossRef]

- W.J. Eakins. 1968, Silanol Groups on Silica and Their Reactions with Trimethyl Chlorosilane and Trimethysilanol, I&EC Product Research and Development, 7 (1), 39-43. [CrossRef]

| Oxide | SiO2 | PbO | Na2O | K2O | P2O5 | CaO | Al2O3 | ZnO | CuO | Fe2O3 | MgO | MnO | TiO2 | BaO | SO3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | 49.7 | 17.3 | 13.2 | 4.0 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 6.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.5 |

| Element | LE | Mg | Al | Si | P | K | Ca | Ti | Mn | Fe | Cu | Zn | Sr | Zr | Nb | Cd | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM1 | 50.335 | 0 | 1.001 | 22.609 | 0 | 0.667 | 4.742 | 0 | 0.328 | 4.940 | 0.023 | 0.034 | 0 | 0 | 0.020 | 0 | 15.299 |

| CM2 | 58.469 | 0 | 1.094 | 21.312 | 0.266 | 0.581 | 3.855 | 0.079 | 0.633 | 4.490 | 0.056 | 0.043 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.123 |

| LPhu3 | 53.081 | 0 | 1.109 | 24.547 | 0 | 0.680 | 4.896 | 0 | 1.017 | 5.167 | 0.039 | 0.029 | 0 | 0 | 0.092 | 0 | 9.342 |

| LPhu5 | 7.193 | 0 | 0.998 | 27.152 | 0.433 | 2.074 | 1.167 | 0 | 0 | 5.917 | 0.060 | 0.021 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.015 | 54.971 |

| NAN4 | 55.044 | 0 | 1.101 | 24.505 | 0 | 1.097 | 4.569 | 0.055 | 0.926 | 4.903 | 0.064 | 0.045 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.683 |

| NAN6 | 15.493 | 0 | 0.892 | 15.485 | 0.293 | 2.881 | 1.736 | 0 | 0 | 3.175 | 0.083 | 0.026 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.023 | 59.910 |

| PHRAE1 | 55.688 | 0 | 0.936 | 22.487 | 0 | 1.219 | 3.619 | 0.050 | 0.480 | 3.668 | 0.037 | 0.119 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.697 |

| TAK5 | 59.620 | 0 | 1.260 | 19.690 | 0.310 | 0.500 | 3.620 | 0.080 | 0.710 | 3.870 | 0.050 | 0.040 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.260 |

| NRTWat1 | 5.438 | 0 | 1.437 | 14.956 | 0 | 3.421 | 1.265 | 0 | 0 | 6.852 | 0.098 | 0.040 | 0 | 0 | 0.116 | 0.030 | 66.346 |

| SoKhla15 | 22.357 | 0 | 0.369 | 17.364 | 0 | 1.887 | 1.692 | 0 | 0.032 | 7.351 | 0.091 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48.857 |

| BKK2 | 1.194 | 0 | 0 | 17.162 | 0 | 3.704 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.004 | 0.081 | 0.098 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 74.756 |

| Autt1 | 2.170 | 0 | 16.422 | 16.422 | 0 | 1.730 | 0.425 | 0 | 0 | 5.461 | 0.104 | 0.031 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.026 | 73.286 |

| ChiN1 | 26.409 | 0 | 16.702 | 16.702 | 0 | 2.710 | 2.085 | 0 | 0 | 3.723 | 0.020 | 0.022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.007 | 47.000 |

| Indonesia | 13.774 | 0 | 1.840 | 15.890 | 0 | 3.390 | 2.180 | 0 | 0 | 4.430 | 0.090 | 0.050 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.020 | 58.240 |

| Pakistan | 53.560 | 1.360 | 0.630 | 34.470 | 0 | 0.260 | 5.120 | 0.180 | 0 | 0.170 | 0 | 0.300 | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0 | 0 | 4.200 |

| Sample Code | Type | Century* | Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | SO3 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 | NiO | CuO | ZnO | As2O3 | Rb2O | SnO2 | Sb2O3 | BaO | PbO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM1 | Chu | 20th ~ 1922 | 2.52 | 0.85 | 5.91 | 42.94 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 5.01 | 2.98 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 6.10 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.06 | 32.24 |

| CM2 | Chu | 19th ~1818 | 7.87 | 0.58 | 3.78 | 62.52 | 1.28 | 0.47 | 1.47 | 7.89 | 0.18 | 0.86 | 6.91 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 5.90 |

| LPhu3 | Chu | 20th ~1933 | 10.92 | 0.58 | 3.19 | 62.22 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 1.33 | 8.32 | 0.15 | 1.11 | 6.42 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 5.21 |

| LPhu5 | Chu | ? | 0.59 | 0.41 | 3.00 | 56.59 | 1.75 | 0.34 | 2.42 | 2.48 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 4.56 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 27.51 |

| NAN1 | Chu | 18th ~1767 | 0.53 | 1.23 | 6.22 | 22.88 | 3.17 | 2.85 | 2.95 | 12.7 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 3.96 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.49 | 42.26 |

| NAN4 | Chu | 20th ~1901 | 10.91 | 0.58 | 3.28 | 62.85 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 1.96 | 8.04 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 6.19 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 4.31 |

| NAN6 | Chu | 20th ~1922 | 1.94 | 0.24 | 2.96 | 41.44 | 1.03 | 0.22 | 4.46 | 3.60 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 3.71 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | 39.93 |

| PHRAE1 | Chu | 20th ~1920 | 9.86 | 0.53 | 2.97 | 62.07 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 2.37 | 7.46 | 0.13 | 0.59 | 5.28 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 7.94 |

| TAK5 | Chu | 20th ~1920 | 9.04 | 0.63 | 2.64 | 67.67 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 1.21 | 9.07 | 0.11 | 1.29 | 2.87 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 4.28 |

| PheRi3 | Chu | 18-19th | 0.03 | 1.13 | 4.30 | 19.83 | 2.03 | 4.5 | 4.55 | 22.47 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0 | 4.60 | 1.65 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 33.14 |

| NRTWat1 | Chu | 19th~1873 | 2.25 | 0.22 | 3.76 | 30.89 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 4.4 | 2.78 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 6.43 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 48.17 |

| SoKhla15 | Chu | 19th ~1856 | 5.08 | 0.37 | 1.47 | 41.68 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 2.94 | 3.36 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 7.84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 36.61 |

| BKK2 | Kriab | 18-19th | 0.97 | 0.21 | 1.05 | 41.71 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 4.75 | 1.53 | 0 | 0 | 3.23 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | 1.06 | 0 | 0 | 44.78 |

| RatBR3 | Kriab | 19th~1824 | 3.72 | 0.49 | 3.91 | 56.78 | 1.85 | 0.53 | 1.55 | 10.32 | 0.16 | 0.92 | 6.02 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 13.18 |

| Autt1 | Kriab | 19th ~1847 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 1.14 | 38.7 | 1.11 | 0.24 | 2.78 | 2.10 | 0 | 0.03 | 6.03 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 47.16 |

| ChiN1 | Kriab | 18-19th | 3.98 | 0.49 | 3.78 | 42.22 | 0.68 | 0.2 | 4.47 | 4.46 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 4.69 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.21 | 0 | 0 | 34.52 |

| NaSiTh4 | Kriab | ? | 0.51 | 0.29 | 2.60 | 49.97 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 8.01 | 3.74 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 1.07 | 0 | 1.21 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0 | 31.05 |

| Indonesia | Chu | ? | 3.18 | 0.77 | 4.01 | 29.26 | 0.56 | 2.65 | 7.13 | 4.48 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 6.77 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.34 | 0 | 0 | 40.35 |

| BKK [7]-1 | Kriab | 19-20th | 10.50 | 0 | 3.30 | 62.00 | 0 | 0 | 1.70 | 10.6 | 0.18 | 1.61 | 8.66 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 | 1.60 |

| BKK [7]-2 | Kriab | 19-20th | 9.60 | 0 | 3.80 | 61.00 | 0 | 0 | 1.60 | 9.90 | 0.21 | 1.69 | 9.36 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 | 2.10 |

| BKK [7]-3 | Kriab | 19-20th | 8.30 | 0 | 3.50 | 55.00 | 0 | 0 | 1.40 | 7.50 | 0.15 | 0.64 | 6.95 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 15.90 |

| BKK [7]-4 | Kriab | 19-20th | 8.30 | 0 | 3.50 | 55.00 | 0 | 0 | 1.40 | 7.60 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 7.07 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.10 | 15.30 |

| CM [8] | Chu | 19-20th | 18.08 | 0.57 | 3.39 | 59.36 | 0 | 0 | 1.56 | 5.57 | 0.04 | 1.12 | 2.50 | 0 | 0.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.57 |

| PheRi4(Green)# | Kriab | 18th~1703 | 0.45 | 0.91 | 1.66 | 37.88 | 1.71 | 1.91 | 4.04 | 2.92 | 0 | 0 | 0.39 | 0 | 3.71 | 0.77 | 0 | 0 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 43.36 |

| Component |

Semi-quantitative WDS (3 points analysis) |

High-Performance WD-XRF (Bulk analysis) |

| wt % | wt% | |

| SiO2 | 41.22 | 47.25 |

| B2O3 | 13.33 | - |

| PbO | 10.63 | 14.25 |

| Na2O | 7.46 | 7.41 |

| K2O | 1.91 | 2.44 |

| MgO | 1.23 | 1.43 |

| CaO | 8.25 | 10.76 |

| Al2O3 | 3.24 | 4.24 |

| Fe2O3 | 3.65 | 4.53 |

| CuO | - | 0.37 |

| ZnO | 0.35 | 0.41 |

| MnO | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| P2O5 | 6.54 | 6.59 |

| NaCl | 2.10 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).