Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. SO2 Exposure Aging Test

2.3. Analytical Techniques

3. Results

3.1. Pigment Characterization

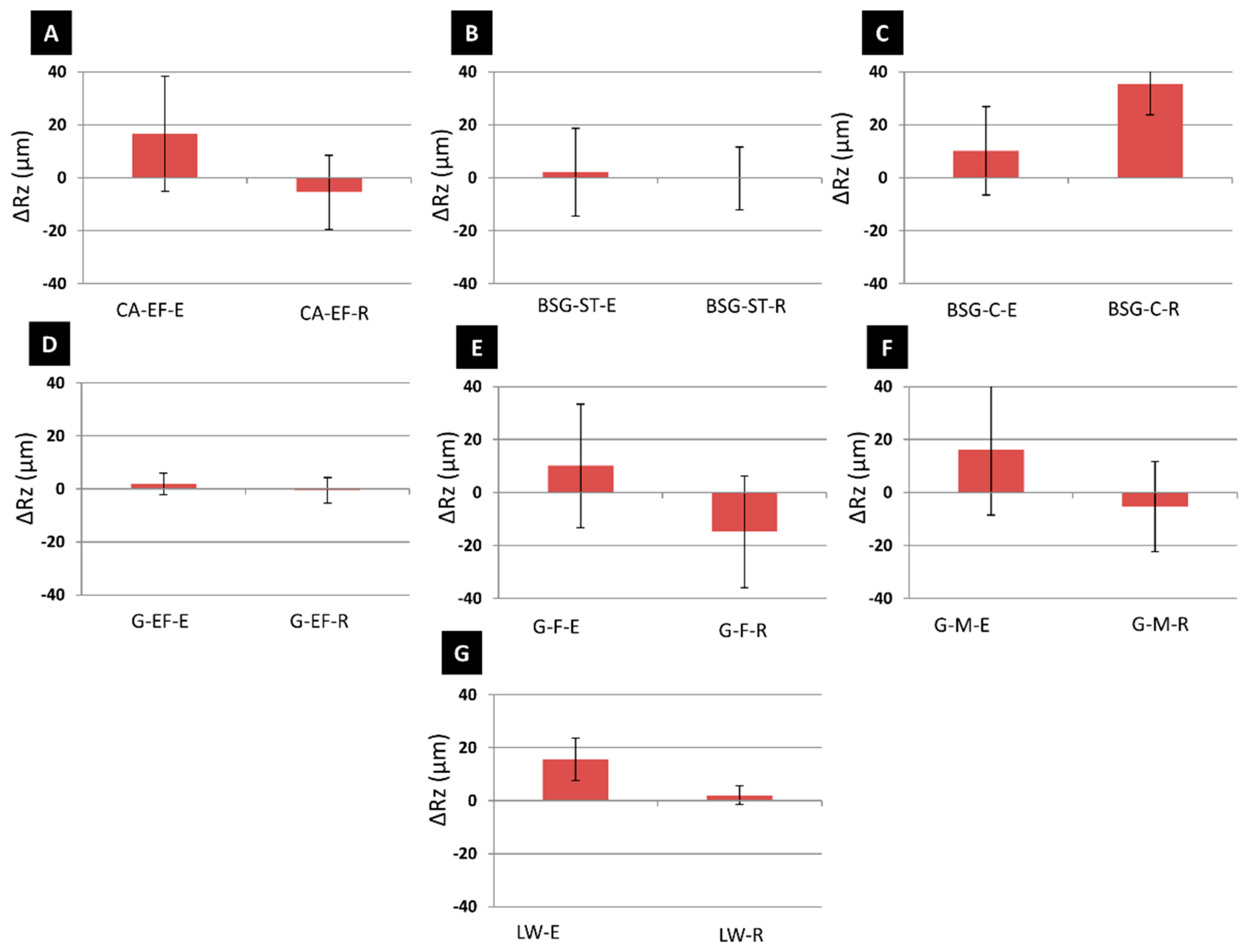

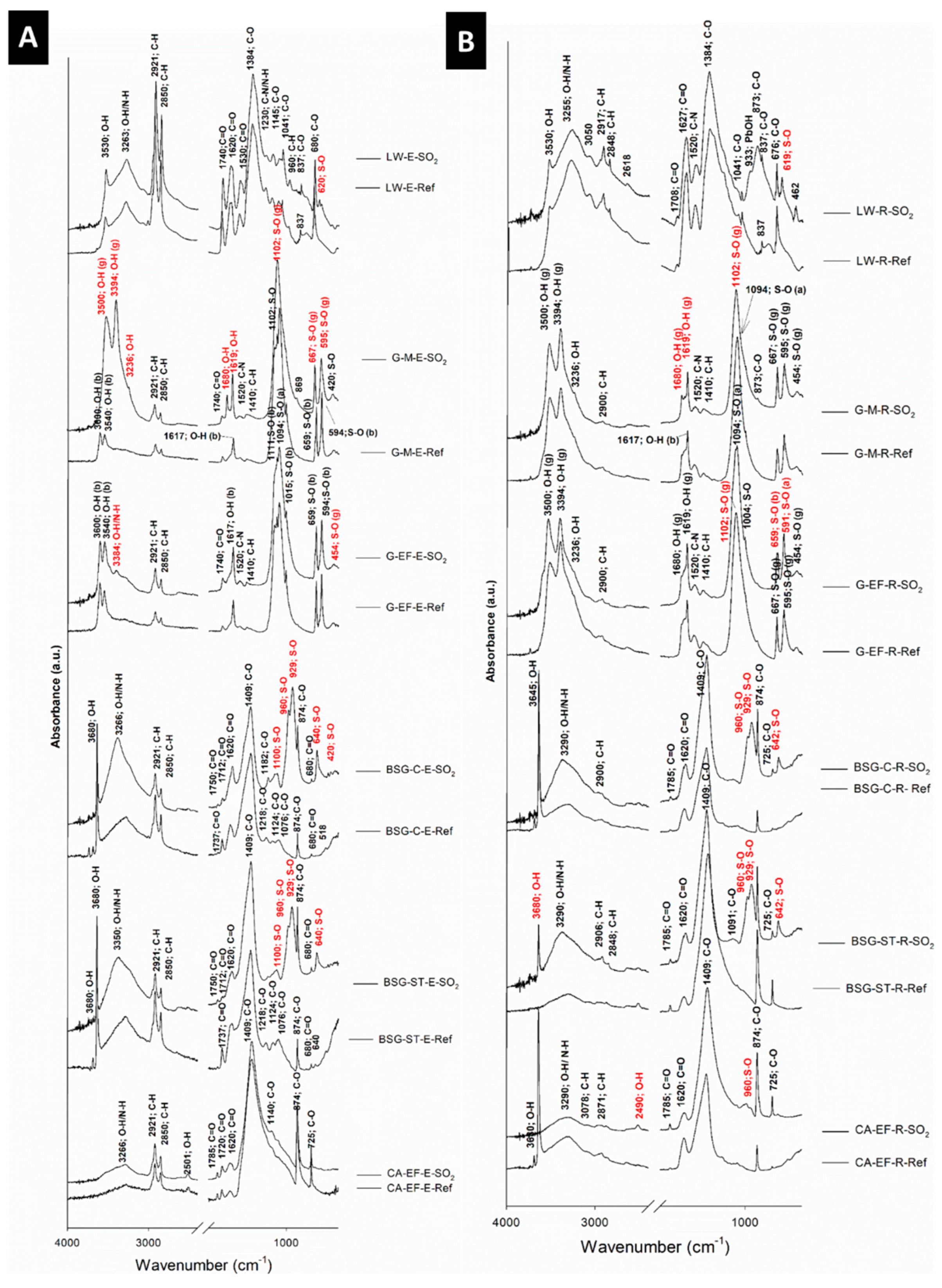

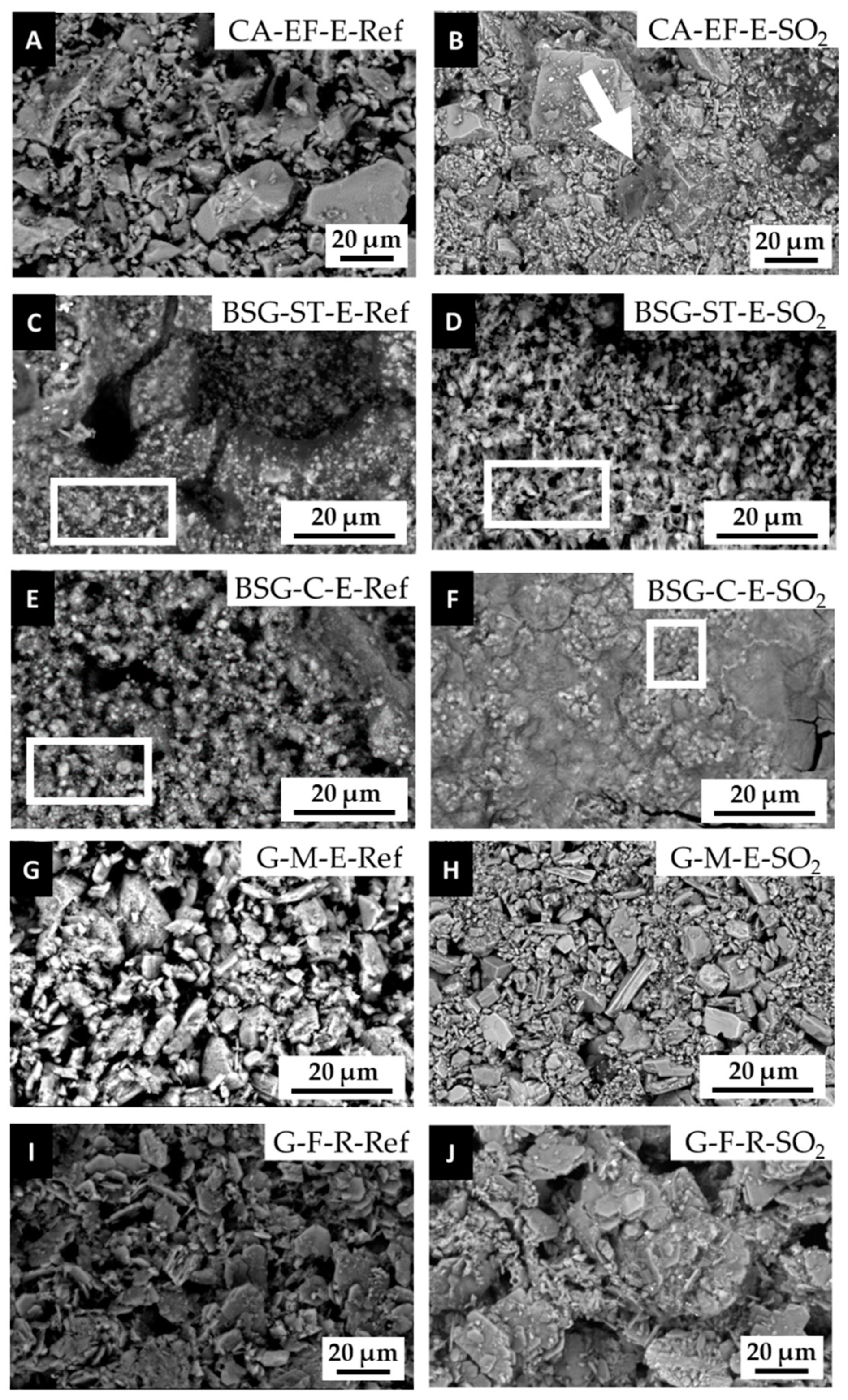

3.2. Physical, Mineralogical and Chemical Changes of the Mock-Ups After SO2 Exposure Aging Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rivas, T.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Paz, M. Sulphur and oxygen isotope analysis to identify sources of sulphur in gypsum-rich black crusts developed on granites. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482-483(1), 137-147. [CrossRef]

- La Russa, M.F.; Fermo, P.; Comite, V.; Belfiore, C.M.; Barca, D.; Cerioni, A.; De Santis, M.; Barbagallo, L.F.; Ricca, M.; Ruffolo, S.A. The Oceanus statue of the Fontana di Trevi (Rome): The analysis of black crust as a tool to investigate the urban air pollution and its impact on the stone degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 593-594, 297-309. [CrossRef]

- Comite, V.; Miani, A.; Ricca, M.; La Russa, M.; Pulimeno, M.; Fermo, P. The impact of atmospheric pollution on outdoor cultural heritage: an analytic methodology for the characterization of the carbonaceous fraction in black crusts present on stone surfaces. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111565. [CrossRef]

- Rovella, N.; Aly, N.; Comite, V.; Randazzo, L.; Fermo, P.; Barca, D.; Alvarez de Buergo, M.; La Russa, M.F. The environmental impact of air pollution on the built heritage of historic Cairo (Egypt). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142905. [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Cardell, C.; Comite, V.; Fermo, P. Characterization of black crusts developed on historic stones with diverse mineralogy under different air quality environments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Coccato, A.; Moens, L.; Vandenabeele, P. On the stability of mediaeval inorganic pigments: a literature review of the effect of climate, material selection, biological activity, analysis and conservation treatments. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5(1), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, P.; Carrizo, L.; Thomachot-Schneider, C.; Gibeaux, S.; Alonso, F.J. Influence of surface finish and composition on the deterioration of building stones exposed to acid atmospheres. Constr. Buil. Mater. 2016, 106, 392-403. [CrossRef]

- Urosevic, M.; Yebra-Rodríguez, A.; Sebastián-Pardo, E.; Cardell, C. Black soiling of an architectural limestone during two-year term exposure to urban air in the city of Granada (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 414, 564–575. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.; Cardell, C.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Burgos-Cara, A.; Elert, K. Effect of proteinaceous binder on pollution-induced sulfation of lime-based tempera paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 123, 99-110. [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, A. Decoupling trends of emissions across EU regions and the role of environmental policies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129130, . [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, N.; Borgioli, L.; Gracia, I.A. I Pigmenti Nell'Arte Dalla Preistoria All Rivoluzi Industriale. Il Prato: Saonara, Italy, 2003.

- Horemans, B.; Cardell, C.; Bencs, L.; Kontozova-Deutsch, V.; De Wael, K.; Van Grieken, R. Evaluation of airborne particles at the Alhambra monument in Granada, Spain. Microchem. J. 2011, 99(2), 429-438. [CrossRef]

- Palet, A. Tratado de Pintura. Color, pigmentos y ensayo. Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2002.

- Asenjo Rubio, E. Las arquitecturas pintadas en las ciudades europeas: Aportaciones desde Málaga: la secuencia cronológica y estilística. Boletín de arte 2005, (26), 117-138.

- Del Pino Díaz, C. La pintura mural: conservación y restauración. CIE Inversiones Editoriales Dossat: Madrid, Spain, 2003.

- Ambers J. Raman analysis of pigments from the Egyptian Old Kingdom. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2004, 35(8–9), 768–73. [CrossRef]

- Cotte, M.; Susini, J.; Metrich, N.; Moscato, A.; Gratziu, C.; Bertagnini, A.; Pagano, M. Blackening of Pompeian Cinnabar Paintings: X-ray Microspectroscopy Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 7484–7492. [CrossRef]

- Maguregui, M.; Knuutinen, U.; Martínez-Arkarazo, I.; Castro, K.; Madariaga, J.M. Thermodynamic and spectroscopic speciation to explain the blackening process of hematite formed by atmospheric SO2 impact: The case of Marcus Lucretius House (Pompeii). Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 3319–3326. [CrossRef]

- Cardell, C.; Herrera, A.; Guerra, I.; Navas, N.; Rodríguez-Simón, L.; Elert, K. Pigment-size effect on the physico-chemical behavior of azurite-tempera dosimeters upon natural and accelerated photo aging. Dyes Pigm. 2017, 141, 53-65. [CrossRef]

- Elert, K.; Cardell, C. Weathering behavior of cinnabar-based tempera paints upon natural and accelerated aging. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 216, 236-248. [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, R.; Prati, S.; Quaranta, M.; Joseph, E.; Kendix, E.; Galeotti, M. Attenuated total reflection micro FTIR characterisation of pigment– binder interaction in reconstructed paint films. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 392(1–2), 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.M.; Costa, G.A.; Franceschi, E. Aging of the paint palette of Valerio Castello (1624–1659) in different paintings of the same age (1650–1655). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2010, 103(1), 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Gutman, M.; Lesar-Kikelj, M.; Mladenovič, A.; Čobal-Sedmak, V.; Križnar, A.; Kramar, S. Raman microspectroscopic analysis of pigments of the Gothic wall painting from the Dominican Monastery in Ptuj (Slovenia). J. Raman Spectrosc. 2014, 45(11–12), 1103–9. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.D.; Clark, R.J. The role of H2S in pigment blackening. J. Cult Herit. 2002, 3(2), 101–5. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodrı́guez, J.L.; Maqueda, C.; De Haro, M.J.; Rodríguez-Rubio, P. Effect of pollution on polychromed ceramic statues. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32(6), 993-8. [CrossRef]

- Manzano, E.; Romero-Pastor, J.; Navas, N.; Rodríguez-Simón, L.R.; Cardell, C. A study of the interaction between rabbit glue binder and blue copper pigment under UV radiation: a spectroscopic and PCA approach. Vib. Spectrosc. 2010, 53(2), 260-268. [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Rivas, T.; Dionísio, A.; Barral, D.; Cardell, C. Effect of a SO2 Rich Atmosphere on Tempera Paint Mock-Ups. Part 1: Accelerated Aging of Smalt and Lapis Lazuli-based Paints. Minerals, 2020, 10(5), 427. [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Cardell, C.; Barral, D.; Dionísio, A.; Rivas, T. Effect of a SO2 Rich Atmosphere on Tempera Paint Mock-Ups. Part 2: Accelerated Aging of Azurite-and Malachite-based Paints. Minerals, 2020, 10(5), 424. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, F. Arte de la pintura. Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 12, 1990.

- Herrera, A.; Navas, N.; Cardell, C. An evaluation of the impact of urban air pollution on paint dosimeters by tracking changes in the lipid MALDI-TOF mass spectra profile. Talanta 2016, 155, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- CIE S014-4/E:2007, Colorimetry Part 4: CIE 1976 L*A*b* Colour Space. Commission Internationale de l'eclairage, CIE Central Bureau, Vienna, 2007.

- UNE-EN USO 4288:1998. Geometrical product specifications (GPS) - Surface texture: Profile method - Rules and procedures for the assessment of surface texture. Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación.

- UNE-EN 828:2013. Adhesives - Wettability - Determination by measurement of contact angle and surface free energy of solid surface.

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Barral, D.; Herrera, A.; Elert, K.; Rivas, T.; Cardell, C. Effect of tempera paint composition on their superficial physical properties- application of interferometric profilometry and hyperspectral imaging techniques. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 117, 56-68. [CrossRef]

- Eastaugh, N.; Walsh, V.; Chaplin, T.; Siddall, R. Pigment compendium: a dictionary of historical pigments. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann publications: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2007.

- Gettens, R.J.; Kühn, H.; Chase, W.T. Lead white. Stud Conserv. 1967, 12(4), 125–39. [CrossRef]

- Elert, K.; Benavides-Reyes, C.; Cardell, C. Effect of animal glue on mineralogy, strength and weathering resistence of calcium sulfate-based composite materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 96, 274-283. [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycki, W.; Tatol, M. Color difference DeltaE-A survey. Mach. Graph. Vis. 2011, 20, 383–411.

- Liang, H.; Keita, K.; Peric, B.; Vajzovic, T. Pigment identification with optical coherence tomography and multispectral imaging. In Proceedings of the 2nd Int. Topical Meeting on Optical Sensing and Artificial Vision, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 12–15 May 2008.

- Liang, H. Advances in multispectral and hyperspectral imaging for archaeology and art conservation. Appl. Phys. A 2012, 106(2), 309-323. [CrossRef]

- Nodari, L.; Ricciardi, P. Non-invasive identification of paint binders in illuminated manuscripts by ER-FTIR spectroscopy: A systematic study of the influence of different pigments on the binders’ characteristic spectral features. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, S.; Laca, A.; Oulego, P.; Paredes, B.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Development and characterization of egg yolk and egg yolk fractions edible films. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 70, 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sanad, W.; Miller, L.M.; Voigt, A.; Klingel, K.; Kandolf, R.; Stangl, K.; Baumann, G. Infrared imaging of compositional changes in inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Vib. Spectrosc. 2005, 38, 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Navas, N.; Romero-Pastor, J.; Manzano, E.; Cardell, C. Benefits of applying combined diffuse reflectance FTIR spectroscopy and principal component analysis for the study of blue tempera historical painting. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 630, 141–149. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, D.; Duce, C.; Bonaduce, I.; Biagi, S.; Ghezzi, L.; Colombini, M.P.; Tinè, M.R.; Bramanti, E. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic study of rabbit glue/inorganic pigments mixtures in fresh and aged reference paint reconstructions. Microchem. J. 2016, 124, 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Blanco, J.D.; Shaw, S; Benning, L.G. The kinetics and mechanisms of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) crystallization to calcite, via vaterite. Nanoscale 2010, 3(1), 265-71. http://doi.org/10.1039/C0NR00589D.

- Ji, J.; Ge, Y.; Balsam, W.; Damuth, J.E.; Chen, J. Rapid identification of dolomite using a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrophotometer (FTIR): A fast method for identifying Heinrich events in IODP Site U1308. Mar.Geol. 2009, 258(1-4), 60-68. [CrossRef]

- Horgnies, M.; Chen, J.J.; Bouillon, C. Overview about the use of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to study cementitious materials. WIT Trans. Eng. Sci. 2013, 77, 251-262. http://doi.org/10.2495/MC130221.

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts. Third edition, John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2001.

- Lane, M.D. Mid-infrared emission spectroscopy of sulfate and sulfate-bearing minerals. Am. Min. 2008, 92(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.; Lane, M.; Dyar, M.; King, S.; Brown, A.; Swayze, G. What Lurks in the Martian Rocks and Soil? Investigations of Sulfates, Phosphates, and Perchlorates. Spectral properties of Ca-sulfates: Gypsum, bassanite, and anhydrite. Am. Min. 2014, 99. 2105-2115. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Raman, Mid-IR, and NIR spectroscopic study of calcium sulfates and mapping gypsum abundances in Columbus crater, Mars. Planet. Space Sci. 2018, 163, 35-41. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, M.H.; Sunder, S.; Taylor, P.; Lopata, V.J. Infrared and Raman spectra and X-ray diffraction studies of solid lead(II) carbonates. Can. J. Chem.1983, 61, 494–502. [CrossRef]

- Siidra, O.; Nekrasova, D.; Depmeier, W.; Chukanov, N.; Zaitsev, A.; Turner, R. Hydrocerussite-related minerals and materials: structural principles, chemical variations and infrared spectroscopy. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, Crystal Engineering and Materials 2018, 74(2), 182-195. [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Del Monte, M.; Sabbioni, C. Origin and growth of the sulfated crusts on urban limestone. Water Air Soil Pollut. 19, 1983, 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Elert, K.; Herrera, A.; Cardell, C. Pigment-binder interactions in calcium-based tempera paints. Dyes Pig. 2018, 148, 236-248. [CrossRef]

- Charola A.E.; Ware, R. Acid depostion and the deterioration of stone: a brief review of a broad topic. In Natural Stone, Weathering Phenomena, Conservation Strategies and Case Studies, Siegesmund, S.; Weiss, T.; Vollbrecht, A. (Eds.); Geological Society Special Publication No. 205: London, United Kingdom, 2002; pp. 393–406.

- Cultrone G.; Arizzi, A.; Sebastián, E.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C. Sulfation of calcitic and dolomitic lime mortars in the presence of diesel particulate matter. Environ. Geol. 2008, 56, 741–752. [CrossRef]

- Bico, J.; Thiele U.; Quere, D. Wetting of textured surfaces. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2002, 206, 41–46. [CrossRef]

| Kremer pigment reference | Authors’ identification code | Kremer mineralogical composition | Authors’ mineralogical composition | Kremer grain size (µm) | Authors’ grain size (µm)* | Mineralogical composition of paints before the aging test | Mineralogical composition of paints after the aging test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg yolk mock-ups | Rabbit glue mock-ups | Egg yolk mock-ups | Rabbit glue mock-ups | ||||||

| Calcite 58720 | CA-EF | Calcite | Calcite Dolomite |

20 | 25 (0.25-100) |

Calcite Dolomite |

Calcite Portlandite |

Calcite Dolomite Ca3(SO3)2SO4·2H2O |

Calcite Gypsum |

| Bianco San Giovanni 11415 | BSG-ST | Portlandite Calcite |

Portlandite Calcite |

120 | 60 (0.25-120) |

Portlandite Calcite |

Portlandite Calcite |

Portlandite Calcite CaSO3·1/2H2O |

Portlandite Calcite CaSO3·1/2H2O |

| Bianco San Giovanni 11416 | BSG-C | Portlandite Calcite |

Portlandite Calcite |

120-1000 | 120 (0.3-250) |

Portlandite Calcite |

Portlandite Calcite |

Portlandite Calcite CaSO3·1/2H2O |

Portlandite Calcite CaSO3·1/2H2O |

| Gypsum Alabaster, Italian plaster 58340 |

G-EF | Gypsum | Bassanite Anhydrite |

<75 | 7 (0.2-85) |

Bassanite Anhydrite |

Gypsum |

Bassanite Anhydrite Gypsum K2SO4 |

Gypsum Bassanite Anhydrite CaSO3 |

| Natural gypsum 58300 Selenite (Terra Alba) |

G-F | Gypsum | Bassanite Anhydrite |

80% <20 18% <25 1.9% <32 1.9% <32 |

9 (0.2-75) |

Anhydrite Gypsum | Anhydrite Gypsum |

Anhydrite Gypsum CaSO3 K0.67Na1.33SO4 MgS2O3·6H2O |

Anhydrite Gypsum CaSO3 K0.67Na1.33SO4 MgS2O3·6H2O |

| Gypsum alabaster 58343 |

G-M | Bassanite | Bassanite Anhydrite |

85% <40 | 16 (1-160) |

Bassanite Anhydrite |

Bassanite Anhydrite |

Gypsum CaSO3 |

Gypsum CaSO3 |

| Lead white 46000 | LW | Basic lead carbonate | Hydrocerussite Cerussite |

<45 | 3 (0.1-10) |

Hydrocerussite Cerussite |

Hydrocerussite Cerussite |

Hydrocerussite Cerussite Pb4O3SO4·H2O Pb2O(SO4) Pb4SO4(CO3)·2(OH)2 |

Hydrocerussite Cerussite Pb4O3SO4·H2O Pb2O(SO4) Pb4SO4(CO3)·2(OH)2 |

| Authors’ identification code | Egg yolk-based samples | Rabbit glue-based samples |

|---|---|---|

| CA-EF | 56.82 ±6.33 | 120.58 ±2.68 |

| BSG-ST | 83.20 ±1.83 | 127.63 ±3.94 |

| BSG-C | 96.97 ±2.28 | 114.12 ±3.73 |

| G-EF | 111.93 ±2.05 | 114.84 ±1.34 |

| G-F | 86.45 ±2.13 | 115.55 ±6.65 |

| G-M | 90.17 ±4.14 | 113.39 ±1.41 |

| WL | 93.70 ±1.87 | 98.67 ±1.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).