1. Introduction

In recent years, substantial research efforts have focused on heat flow systems and the development of advanced control strategies for their efficient temperature control. In industrial systems, any malfunction in temperature control can lead to significant financial losses and even endanger human life. Therefore, temperature regulation in both civilian and industrial applications should not be left to human intervention but must be managed by autonomously operating, software-based control mechanisms. Due to their simple structure and reliance on only two or three parameters, PI controllers have become one of the most widely used control methods in industrial applications. However, despite its relatively simple structure compared to other linear control methods, the parameters of a PI controller must be optimized according to the dynamics of the specific system. For this reason, the literature contains a substantial number of academic studies on PI parameter optimization. For instance, Adrian has investigated the optimization of heat transfer paths between a volume and a single point, showing that when heat can travel through multiple channels, the most efficient configuration for minimizing overall resistance under steady-state conditions is a tree-like structure [

1]. The optimization of such tree-shaped flow patterns, combining conduction and convection effects, has been demonstrated in two-dimensional fin systems. This study illustrates both the natural emergence of organized structures and the potential of engineering approaches that transcend disciplinary boundaries. Cermak et al., have examined sap flow in mature tree trunks by employing a heat transfer measurement technique [

2]. Their method allowed for continuous, automated monitoring of sap transport across long periods and across many specimens. Davoud and Ellips, on the other hand, have presented various applications of particle swarm optimization (PSO) and provided a taxonomy of its algorithmic variants [

3]. Rao and Patel, have applied PSO to thermodynamic optimization of heat exchangers, benchmarking it against genetic algorithms, and studied the impact of PSO parameter adjustments on convergence and solution quality [

4]. Vakili and Gadala, have explored the use of PSO for inverse heat conduction problems [

5]. They evaluated computational requirements for three PSO variants (standard, impulsive, and fully impulsive), concluding that the method is effective even in noisy conditions. Manoharan et al., have introduced Forest Fire Optimization (FFO) for wireless sensor networks constrained by node energy [

6]. Their findings demonstrated both scalability and robustness, establishing FFO as a competitive solution. Sayah and Zehar, have compared Differential Evolution (DE) method with other evolutionary methods and highlighted its capacity to solve complex, non-linear, and multi-modal functions [

7]. Using multiple generator cost scenarios, they validated the effectiveness of the proposed optimization algorithm. Babu and Jehan, have also addressed two multi-objective optimization problems a simple test problem and an engineering problem involving cantilever design, solved using Differential Evolution (DE), a population-based search algorithm considered an improved form of the GA [

8]. Simulations include: as a first part solving both problems using the penalty function method, and secondly, solving the first problem using the weighting factor method and obtaining a Pareto-optimal set. The results show that DE is robust, fast, and efficient. To further demonstrate its effectiveness, the classical Himmelblau function with bounded variables is solved using both DE and GA. The DE has achieved the exact optimum value in fewer generations compared to the basic GA. Wang et al., have proposed an exergy-based optimization model is developed to reduce the energy consumption and operating costs of AEP [

9]. A new multi-objective state transition algorithm is proposed for the complex multi-objective problem, including archiving and infeasible solution modification mechanisms. Thanks to the new operators, the algorithm achieves Pareto optimal solutions quickly, accurately, and in a balanced manner, and has yielded successful results in both benchmark tests and industrial applications. Woźniak et al., have studied a plant where hot water was circulated through two heat exchangers using controlled pumps [

10]. The system was calibrated using Polar Bear Optimization, and the results were compared with PSO method. Comparisons with non-optimal parameters revealed that applying the correct settings resulted in significant improvements. Yang et al., have combined Sliding Mode Control (SMC) with Model Predictive Control (MPC) to evaluate fault-tolerant control for discrete-time systems with time delays [

11]. The optimization process was enhanced with PSO method to avoid local minima and improve control performance.

Similarly, Khadraoui and Nounou, have studied robust controller design for input-constrained linear systems using frequency-domain data [

12]. In this context, they introduced a data-driven control approach in which controllers are designed based directly on measurement data. They have also aimed to develop a nonparametric controller design method based on frequency-domain data, considering input constraints. Furthermore, Li et al., have developed a new bionic algorithm called artificial tree (AT) algorithm inspired by the law of tree growth [

13]. The calculation process of AT is achieved by simulating the transportation of organic matter and the updating of tree branches. They found that AT is very effective in dealing with various problems. Deng et al., have developed a differential evolution algorithm augmented with mutation operators and adversarial learning strategies [

14]. This method uses a generalized adversarial learning mechanism to select the superior performing solution from the current solution and the adversarial solution to improve the initial population and efficiently approach the global optimum. This approach allows the direction of convergence to be oriented, thereby accelerating the algorithm’s convergence rate, improving computational efficiency, enhancing the stability of the solution process, and significantly reducing the likelihood of premature convergence. It is demonstrated that the proposed algorithm exhibits higher convergence accuracy, faster convergence speed and superior optimization capacity in the optimization of high-dimensional and complex functions. As another example on literature, Ledezma et al., have focused on the problem of connecting a heat-generating volume to a point heat sink using a finite amount of highly conductive material that can be distributed throughout the volume [

15]. In their work, a comprehensive study was carried out on the problem of optimizing the thermal access between a finite volume and the point, i.e., minimizing the thermal resistance. It was demonstrated that the optimal design is characterized by a tree-like distribution of high-conductivity material. Furthermore, the geometry, operating mechanism, and minimum thermal resistance of this tree structure can be precisely determined, and the constrained optimization of access paths corresponds to macroscopic structures observed in nature.

In this paper, the controller parameters of a HFS have been obtained by using ATA, PSO, DEA, CMOSTA and AFFO optimization methods, and then tested in real-time experimental setup. The obtained results have been compared with Z-N method and analyzed in detail in terms of rise time, reference tracking success and improvement rate, etc. In addition, the reference tracking success of the all optimization methods compared to Z-N, has also been analyzed numerically by calculating their MAE values by using real-time data, as well. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed optimization methods have provided superior reference tracking performance compared to the classical Z–N method and significantly enhance the performance of the linear controller.

3. Experimental Results

In this section, the experimental results of all optimization methods have been presented. The lower and upper bound values of the controller parameters are selected as

and

, respectively. Also, the controller parameter values obtained from all optimization methods are presented in

Table 2.

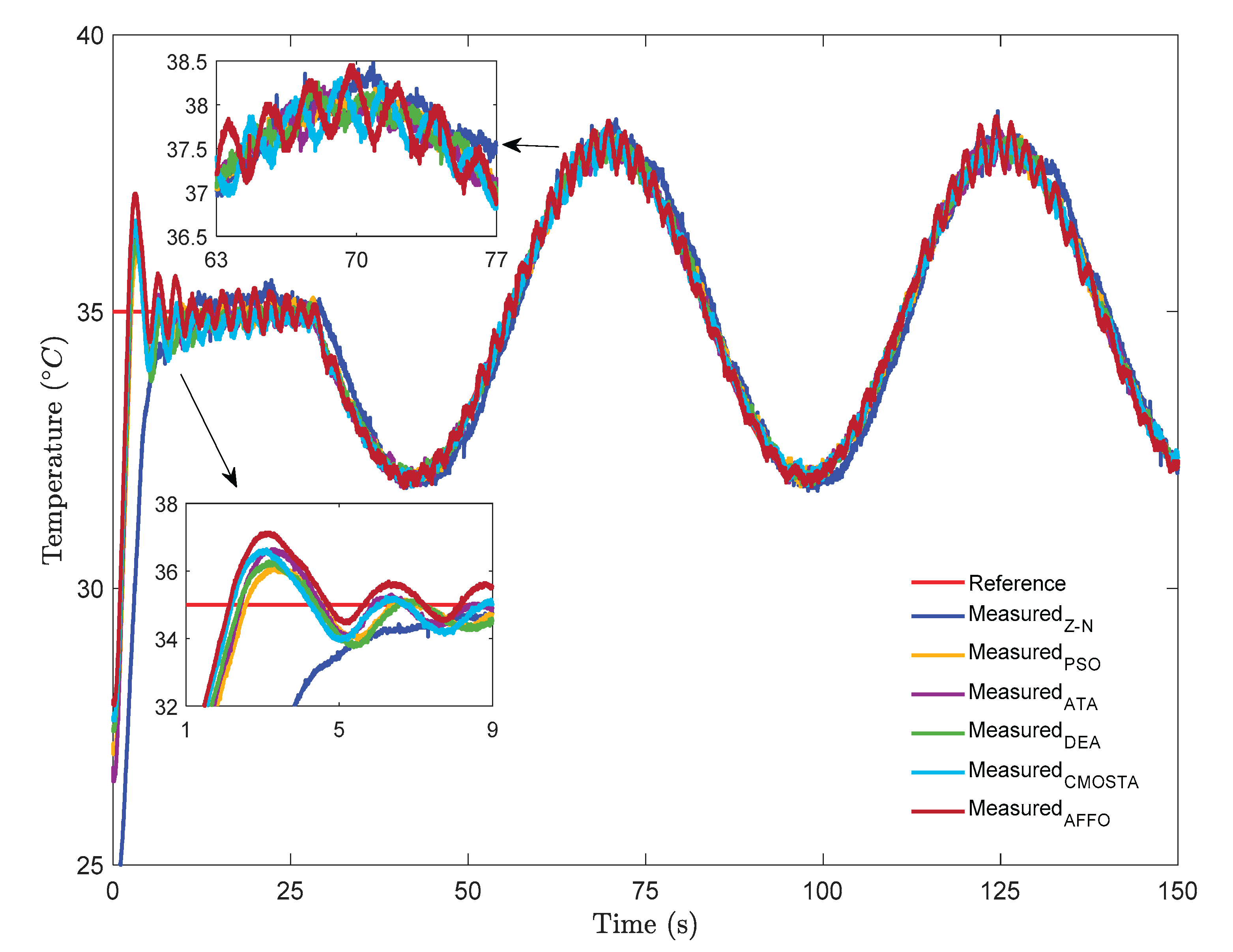

In

Figure 2, a step + sinusoidal reference signal is applied to the HFS. For the step part of the reference signal, all optimization methods have exhibited nearly the same rise time, with the exception of the Z–N method. As can be seen in the figure, the AFFO method have reached the reference signal faster than the other optimization methods. However, although the AFFO method achieved the shortest settling time, it also exhibited a larger overshoot magnitude value compared to the other optimization techniques. Examining the performance of the Z–N method, it is observed that the reference signal is reached at approximately the 11th second, after which the method continued to track the reference with a noticeable overshoot.

Furthermore, although all methods except Z–N followed the reference with slight oscillations, the DEA method has demonstrated the best temperature tracking performance among them. For the sinusoidal part of the reference signal, the Z–N method is observed to have difficulty tracking the reference signal, exhibiting large tracking errors and frequent overshoots. In addition, the AFFO method followed the reference signal with more pronounced oscillations compared to the other optimization methods, with CMOSTA showing the closest performance to it. Furthermore, similar to the behavior observed in the step part of the reference signal, the DEA method has demonstrated superior performance in tracking the smoothly varying sinusoidal reference signal compared to the other methods.

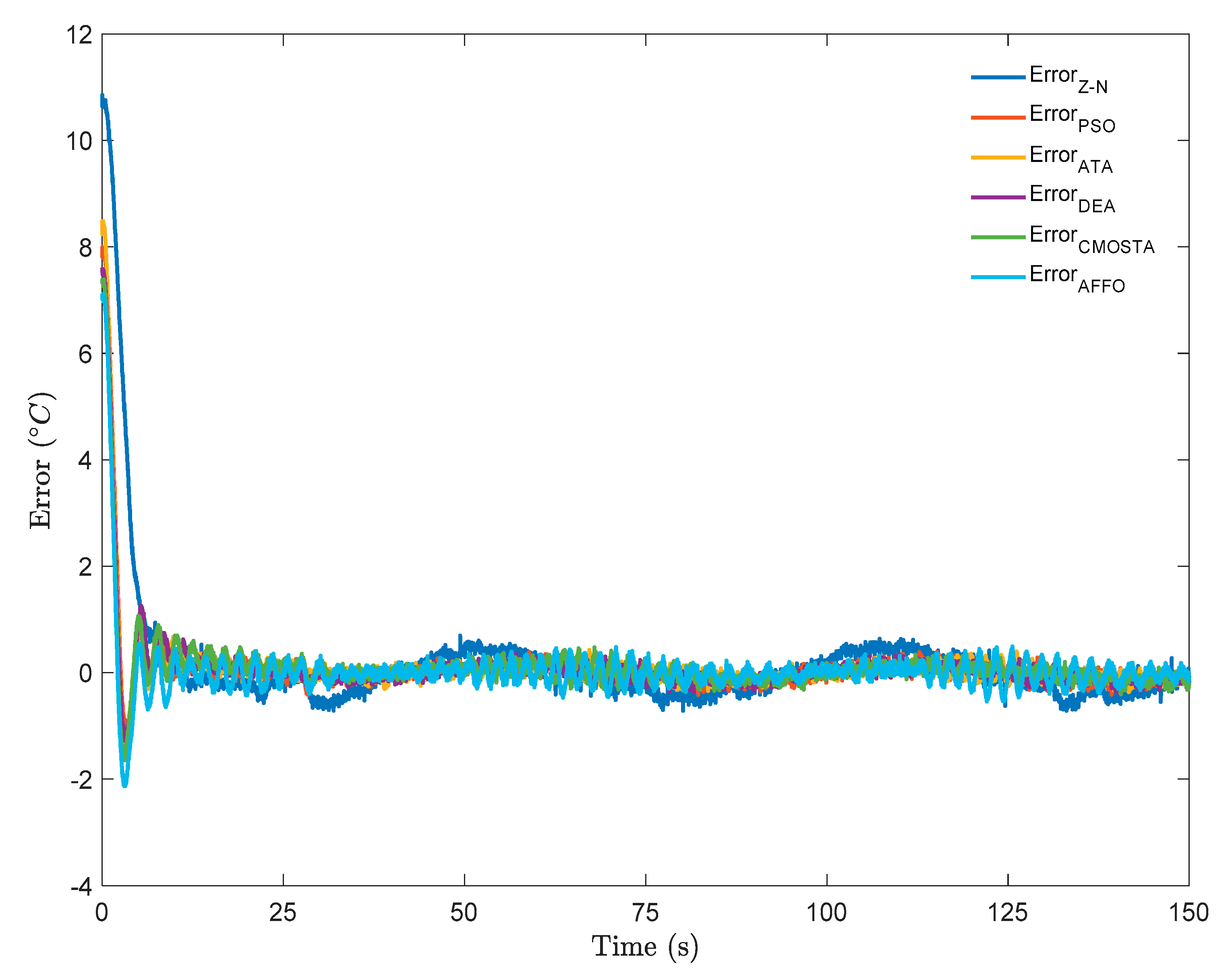

In

Figure 3, the error signals for all optimization methods. As can be seen from the figure, the Z–N method exhibited the highest reference-tracking error. In addition, although the temperature tracking errors of the methods other than Z–N are of nearly the same magnitude, as can be seen from the figure, the DEA method appears to have a lower temperature tracking error throughout the reference signal.

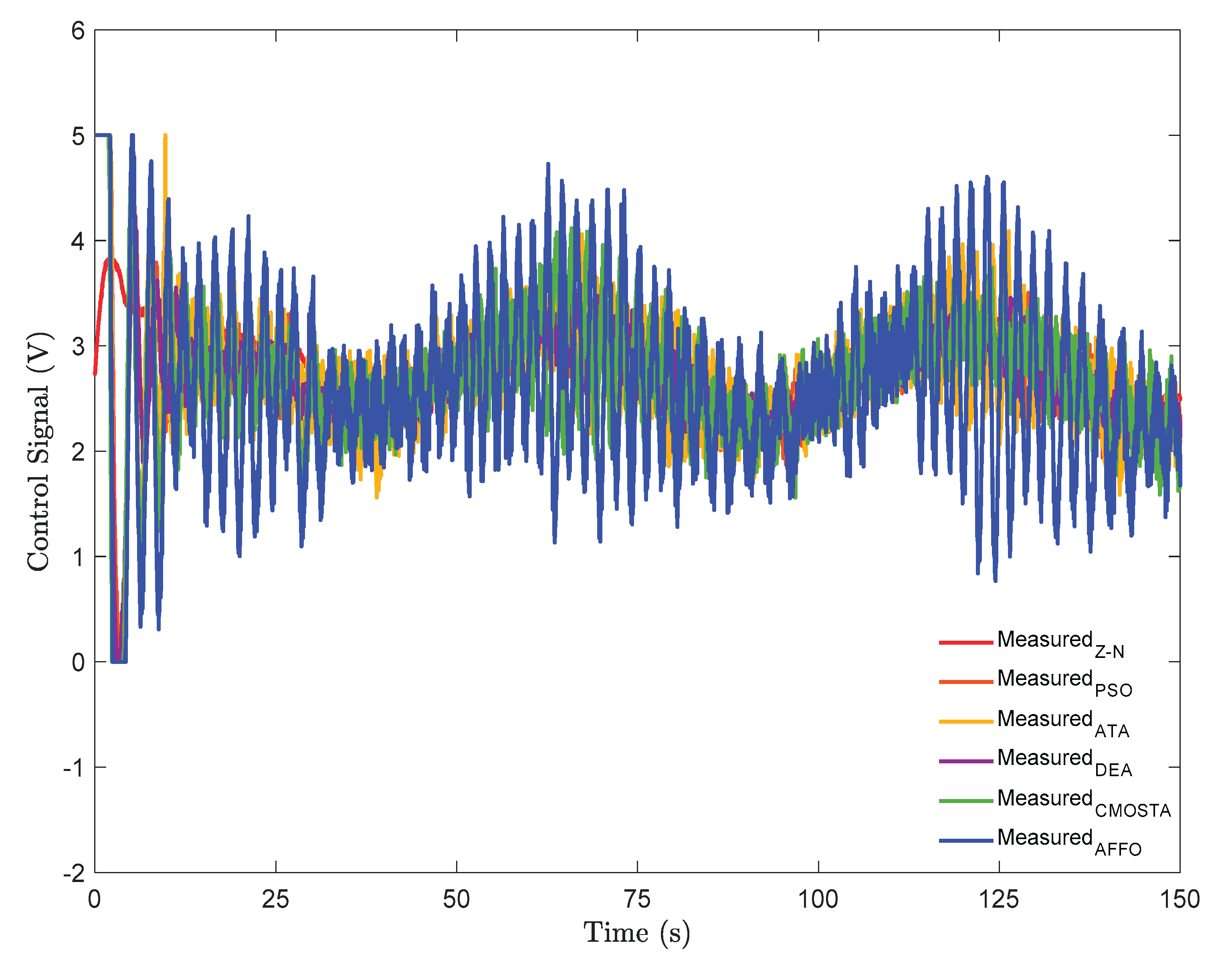

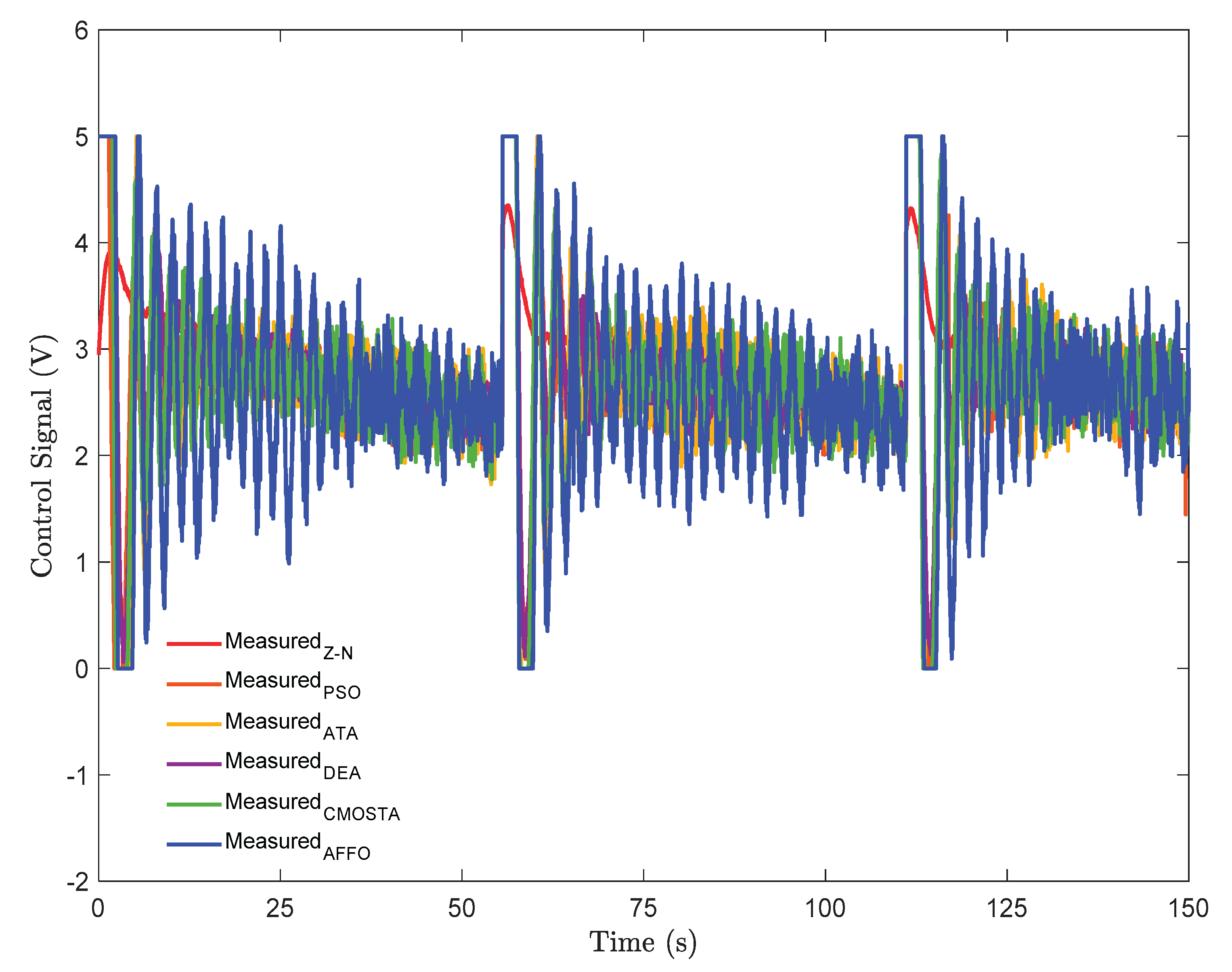

In

Figure 4. the control signals of all optimization methods have been depicted. For each method, the amplitude of the control signal applied to the system for temperature tracking, is kept within the range of 0–5 V. As illustrated in the figure, the AFFO method produced the highest amplitude and most oscillatory control signal along the reference trajectory compared to the other methods. Although the Z–N method generates the least oscillatory control signal, the control effort produced by the controller parameters obtained with this method, is insufficient for effective reference temperature tracking. In contrast, the DEA method, which provided the best temperature tracking performance, has produced one of the lowest amplitude control signals, together with CMOSTA.

Moreover, the MAE values obtained from the experimental results to analyse the reference temperature tracking performance of all optimization methods, are presented in

Table 2. For the step part of the reference signal, the DEA method has the lowest MAE value of approximately 0.6188, which shows that it is the optimization method with the highest tracking accuracy. After that, the DEA is followed by AFFO with 0.6291, PSO with 0.6416, CMOSTA with 0.6602 and ATA with 0.6650, respectively. Furthermore, the highest MAE value, 1.3471, is observed for the Z–N method, indicating that it exhibited the worst reference-tracking performance for the step part of the reference signal. When analysing the MAE values for the sinusoidal part of the reference signal, it is seen that all optimization methods have almost the same MAE value, but the method with the lowest MAE value belongs to the DEA method with approximately 0.0901. Besides, it is observed that this method is followed by CMOSTA with 0.1011, PSO with 0.1098, ATA with 0.1107, AFFO with 0.1307 and Z-N with 0.2930, respectively. Additionally, it was observed that the DEA achieved the lowest overall MAE value for the entire reference signal, approximately 0.2055, indicating the best tracking performance, while the Z-N recorded the highest MAE value, around 0.4898.

Table 2.

The MAE values of all optimization methods for step + sinusoidal reference signal.

Table 2.

The MAE values of all optimization methods for step + sinusoidal reference signal.

| Methods |

Step |

Sinusoidal |

Step + Sinusoidal |

| Z-N |

1.3471 |

0.2930 |

0.4898 |

| PSO |

0.6416 |

0.1098 |

0.2091 |

| ATA |

0.6650 |

0.1107 |

0.2428 |

| DEA |

0.6188 |

0.0901 |

0.2055 |

| CMOSTA |

0.6602 |

0.1011 |

0.2526 |

| AFFO |

0.6291 |

0.1307 |

0.2751 |

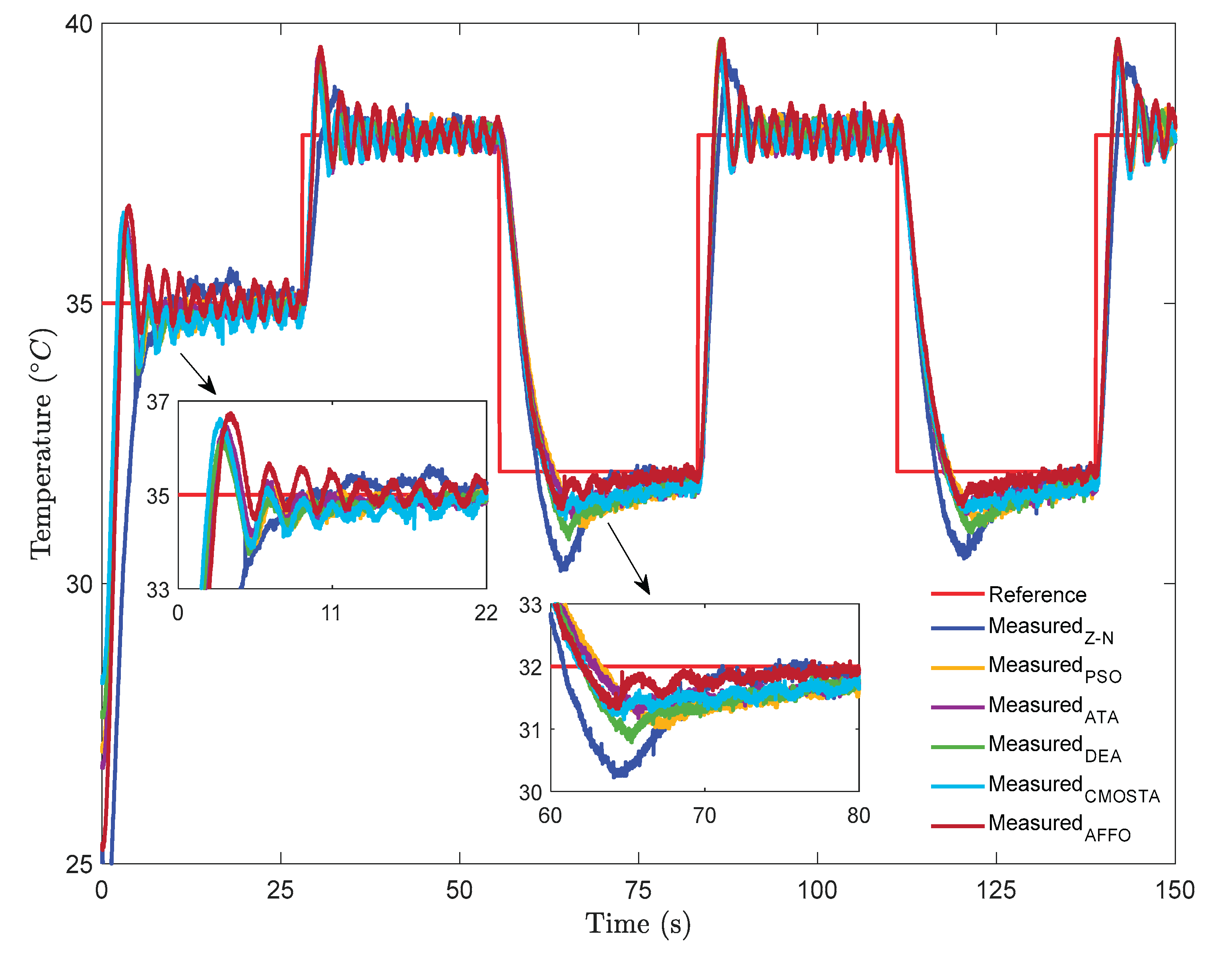

In

Figure 5, the experimental results of all optimization methods have been depicted for step + square reference signal. Examining the step part of the reference signal, it is observed that the CMOSTA, DEA, and PSO methods exhibited nearly similar rise time performance, whereas the AFFO method displayed the largest overshoot compared to the other techniques. In addition, the AFFO and CMOSTA methods showed more pronounced oscillations during reference tracking relative to the remaining methods. In contrast, the performance of the Z–N method indicated that the reference signal is reached at approximately the 11

th second, after which the method continued to track the reference with a noticeable overshoot. In the time-varying portion of the reference signal, a square temperature signal form has been applied to evaluate how the controller parameters respond to sudden changes. As illustrated in the figure, the DEA, AFFO, and CMOSTA methods responded more rapidly to the sudden changes in the square reference than the other methods. However, the AFFO method exhibits the highest overshoot, and together with CMOSTA, produced larger oscillations during reference tracking compared to the other approaches. Furthermore, in the decreasing phase of the square reference, the Z–N method showed the highest overshoot, while the DEA method followed the reference temperature with performance comparable to CMOSTA, ATA, and PSO.

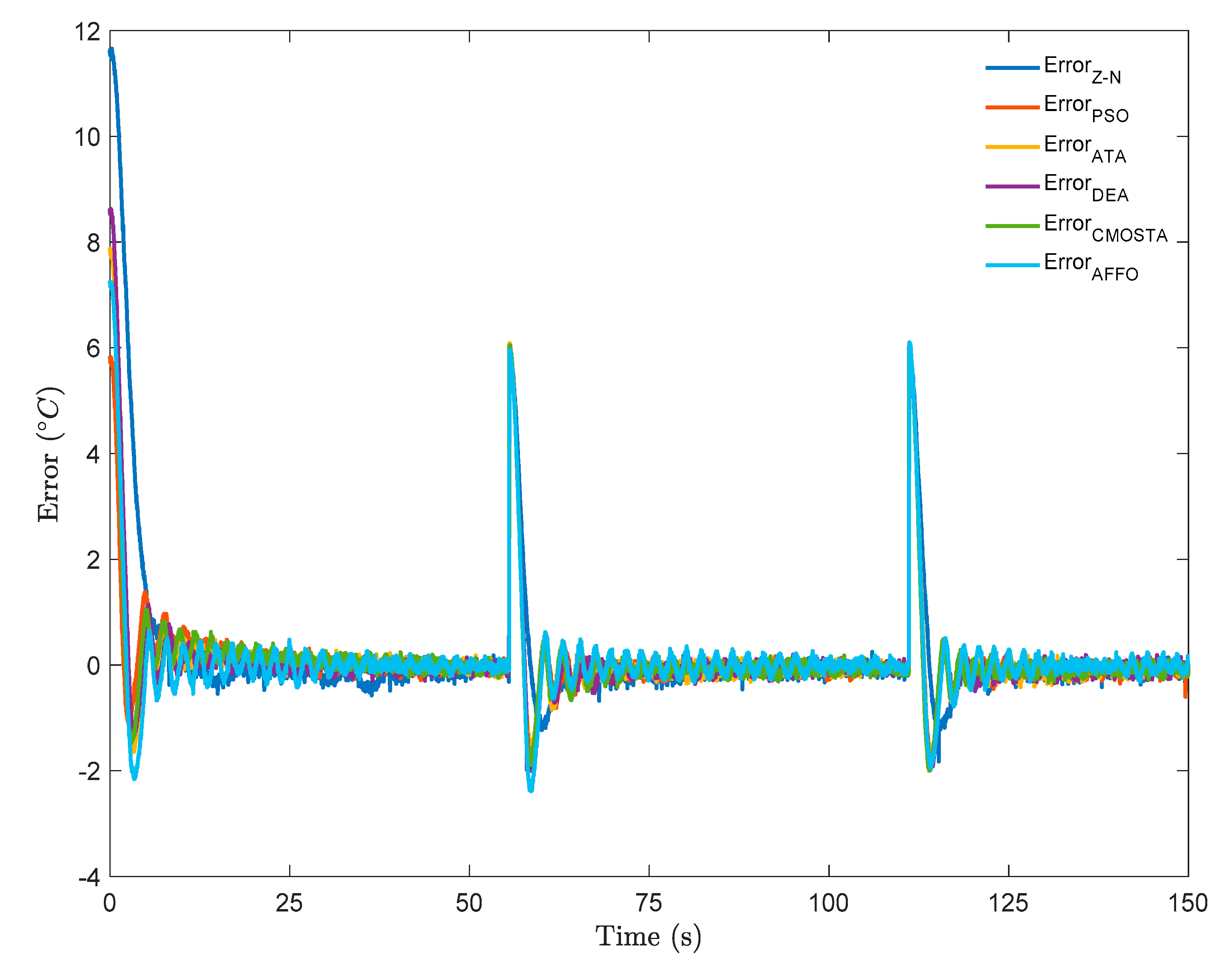

In

Figure 6, the error signals of all optimization methods throughout the step + square reference signal have been depicted. In the step part of the reference signal, the DEA method exhibited a lower reference-tracking error compared to the other methods. In contrast, the AFFO method showed some error oscillations with amplitudes ranging from -2 to 1. Similar oscillatory behavior is observed in the CMOSTA method. The PSO and ATA methods exhibited nearly the same error amplitudes. When examining the Z–N method performance, while the other methods maintained the error values around approximately 0, the error magnitude for Z–N varied within the range of -0.5 to 0.5 throughout to the square reference signal. For the time-varying part of the reference signal, it is observed that under sudden changes, the AFFO method produced higher error values (-1 to 1) compared to the other methods, whereas the Z–N method exhibited errors due to overshoot. Moreover, the PSO method showed the next highest error oscillations following AFFO, followed by CMOSTA, ATA, and DEA, with the DEA method achieving the lowest error magnitude overall.

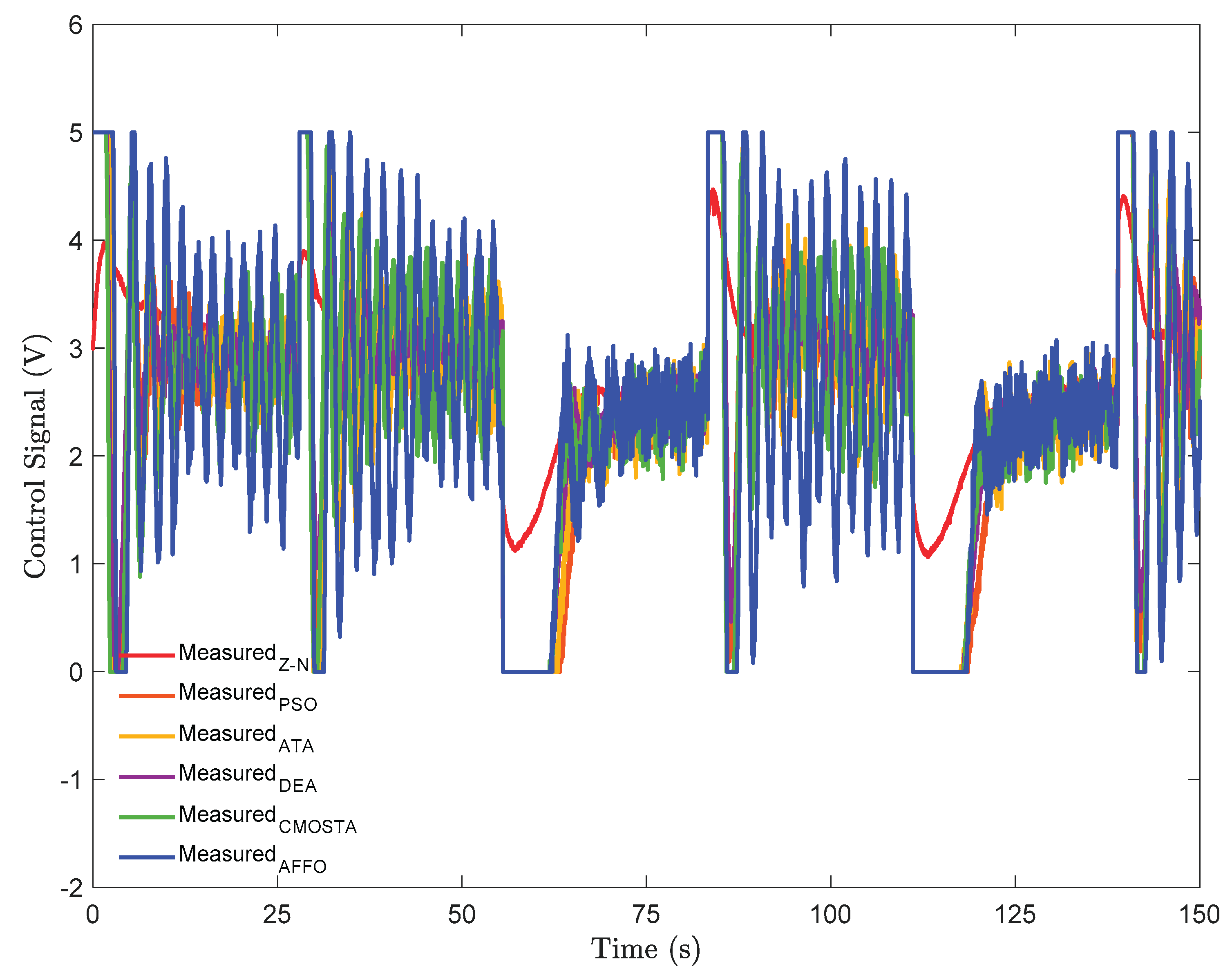

In

Figure 7, the control signals of all optimization methods have been given. In the step part of the reference signal, the AFFO method produced a higher amplitude control signal compared to the other methods. The method with the next highest control signal amplitude was ATA, followed by CMOSTA, PSO, and DEA, in that order. Although the Z–N method generated the least oscillatory control signal, the controller parameters obtained with this method result in the poorest temperature tracking performance. For the square reference signal, the control signal amplitudes showed a similar trend: the AFFO method exhibited the highest amplitude and oscillations, followed by ATA, CMOSTA, PSO, and DEA. Notably, although the DEA method produced the lowest amplitude control signal, it achieved the lowest error magnitude, as also illustrated in the error graph in

Figure 6.

Besides, the MAE values obtained from the experimental results for the step + square temperature signal, used to evaluate the temperature tracking performance of all optimization methods, are presented in

Table 3. For the step portion of the reference signal, the DEA method exhibited the lowest MAE of approximately 0.6006, indicating the highest tracking accuracy among the methods. It is followed by ATA (0.6443), PSO (0.6468), CMOSTA (0.6537), AFFO (0.7966), and Z–N (1.3655). For the square part of the reference signal, all methods showed relatively similar MAE values, with DEA again achieving the lowest value of approximately 0.7014. This is followed by CMOSTA (0.7107), ATA (0.7150), AFFO (0.7357), PSO (0.7483), and Z–N (0.7651). Considering the overall reference tracking performance across the entire signal, the DEA method again achieved the best result with a MAE of 0.7005, followed by ATA (0.7018), CMOSTA (0.7100), AFFO (0.7192), PSO (0.7294), and Z–N (0.8772). These results indicate that the controller parameters obtained using DEA provided the most accurate reference tracking performance.

In

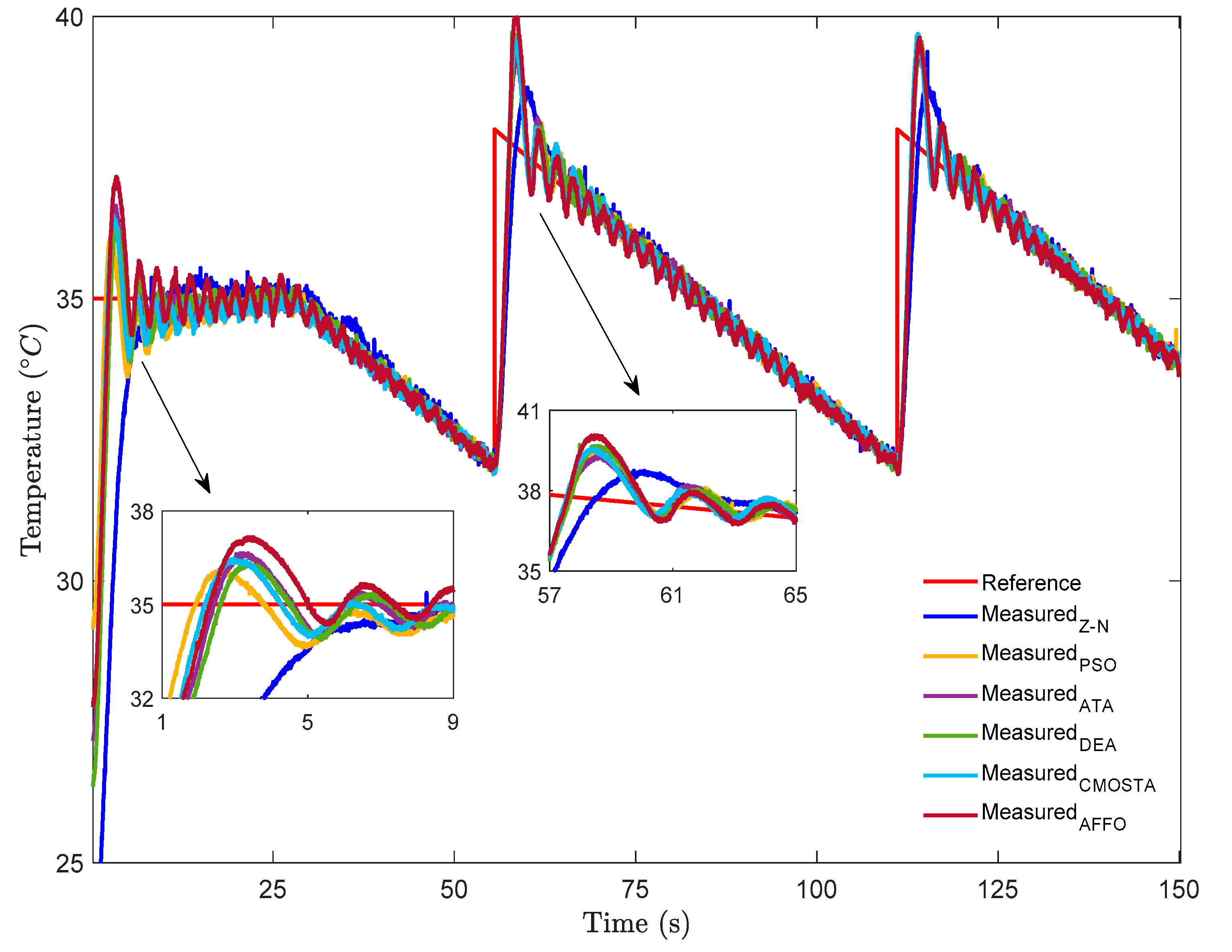

Figure 8, the experimental results of all optimization methods have been depicted for step + sawtooth reference signal. For the step part of the reference signal, the PSO method reached the reference signal most quickly, followed by CMOSTA, AFFO, ATA, and DEA, respectively. Additionally, the AFFO method exhibited the highest overshoot, while the PSO and DEA (excluding Z–N) displayed the lowest overshoot, and the remaining methods showed nearly similar overshoot magnitudes. All methods tracked the reference temperature signal with slight oscillations throughout the step part, with the largest oscillations observed in AFFO. In contrast, the Z–N method reached the reference at approximately the 12

th second and continued tracking with overshoot thereafter.

For the sawtooth part, which includes both abrupt and smooth changes, the AFFO method again showed the highest overshoot, followed by CMOSTA, DEA, PSO, and ATA. All methods attempted to track the slowly varying portion of the sawtooth reference with slight oscillations, and nearly all optimization methods exhibited similar reference-tracking performance and amplitude profiles. Additionally, the Z–N method responded very slowly to the sudden change and continued to track the reference with overshoot.

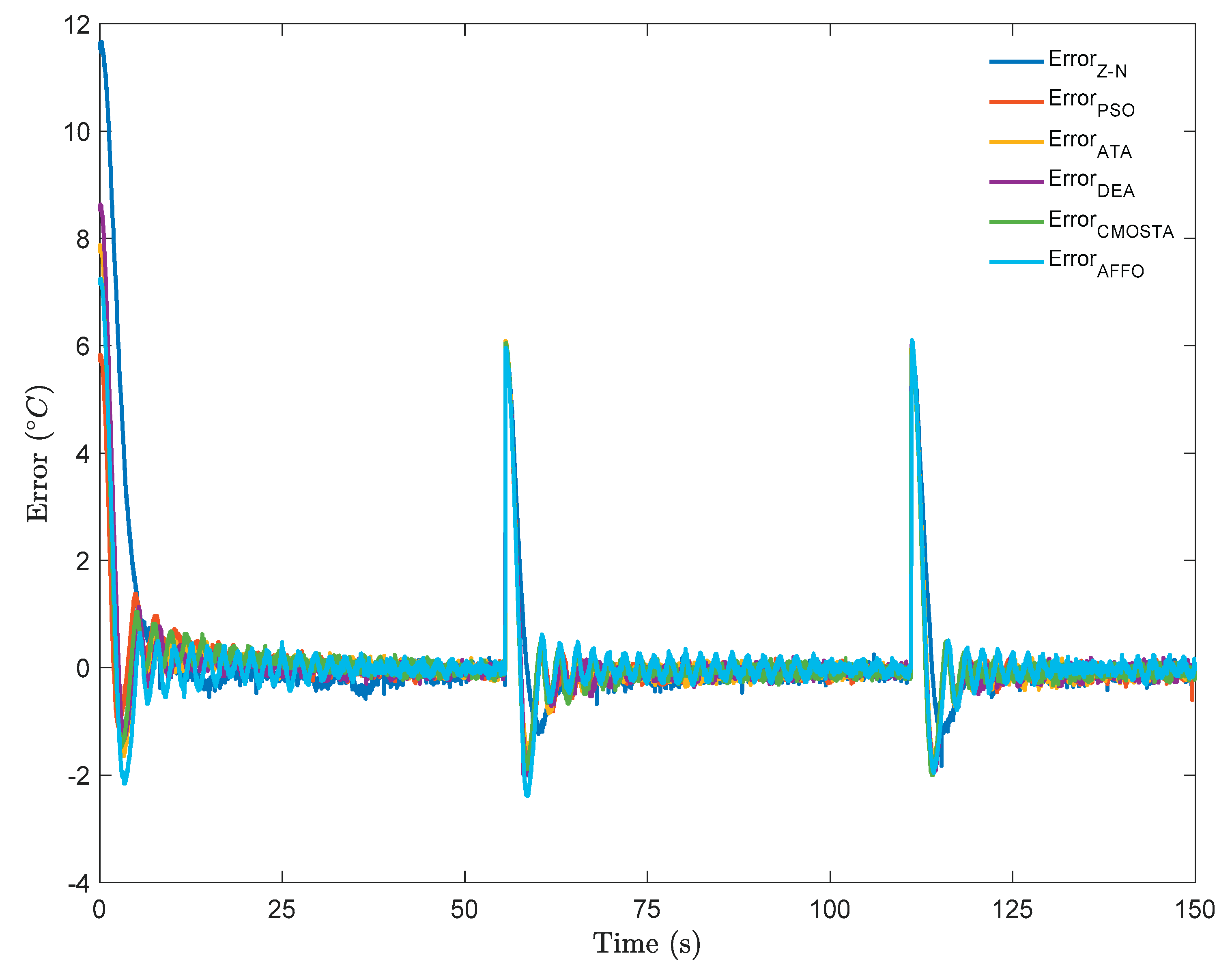

In

Figure 9, the error signals of all optimization methods under step + sawtooth reference signal have been given. For the step part, the Z–N method exhibited the highest initial error, followed by DEA, ATA, CMOSTA, AFFO, and PSO, respectively. Additionally, the AFFO method, which has the largest overshoot, showed an error value approaching -nearly 2, with the other methods following. The Z–N method, due to its delayed response and subsequent overshoot, exhibited error values fluctuating between -0.5 and 0.5, whereas the error values of the other optimization methods quickly converged nearly toward zero. For the sudden-change part of the sawtooth reference signal, the highest error is observed in the AFFO method, followed by DEA, PSO, ATA, and CMOSTA. The error amplitudes of all methods varied approximately between -0.5 and 0.5 and subsequently converged nearly toward zero. In contrast, the Z–N method failed to converge to zero throughout the sawtooth signal, with the error magnitude continuously fluctuating due to overshoot. Overall, the DEA method demonstrated relatively superior reference-tracking performance compared to the other methods.

Figure 10 presents the control signals obtained from all optimization methods. For the step part of the reference signal, the AFFO and CMOSTA methods produced the highest control signal amplitudes, followed by PSO, ATA, and DEA, in that order. Although the control signal generated by the AFFO method has had a higher amplitude, its reference tracking performance has been found to be lower compared to the other methods. Additionally, the control signal of the Z–N method exhibited minimal oscillation and varied approximately between 0 and 4 V.

For the sawtooth part of the reference signal, the AFFO method again produced the highest amplitude control signal, followed by PSO, ATA, CMOSTA, and DEA. Despite ATA, CMOSTA, and AFFO generating relatively higher control signal amplitudes, the DEA method achieved comparatively more effective reference tracking performance. It is also observed that the control signals reached their maximum value of 5 V at points corresponding to sudden changes in the reference signal, while their amplitudes were significantly lower in regions characterized by smoother changes.

Besides,

Table 4 presents the MAE values obtained from the experimental results of the step + square temperature signal to analyze the temperature monitoring performance of all optimization methods. Firstly, it was observed that the highest MAE value for the step part of the reference signal was obtained with the Z-N method with approximately 1.3413. On the other hand, it was observed that the best temperature tracking in the step part of the reference signal was obtained with the controller parameters combined with the DEA method having lowest MAE value with approximately 0.6434. Secondly, it was observed that the lowest MAE value for the part of the reference signal containing time-dependent changes was obtained with DEA, approximately 0.2603, while the highest value was obtained with Z-N, again 0.3334. Thus, it was observed that the controller parameters obtained with DEA have followed the saw reference signal with less error than other methods. Finally, it was observed that the method with the best reference tracking performance and minimum MAE value throughout the entire reference belongs to the controller parameters obtained by the DEA method with 0.3310, followed by CMOSTA with 0.3442, PSO with 0.3354, ATA with 0.3374, AFFO with 0.3533 and Z-N with 0.5215, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this study, the parameters (Kp and Ki) of the PI controller used in the temperature control of a time-delayed HFS system, were obtained by using Z-N, ATA, AFFO, PSO, CMOSTA and DEA optimization methods and tested in real time for three different step + time-varying reference signals. The results were analyzed both figural and performance analyses were performed by calculating MAE values. As a result, the following findings were obtained.

The first experiment, step + sinusoidal temperature reference signal, was implemented to analyze the reference tracking performances of the controller parameters obtained via mentioned optimization methods, during a smoothly changing signal.

Table 5 presents the improvement rates of the PSO, ATA, AFFO, CMOSTA, and DEA methods with respect to the Z–N method. Examination of the table shows that, for the step part of the reference signal, all proposed optimization methods achieved at least a 50% improvement rate in reference-tracking performance over Z–N method. Furthermore, the DEA method demonstrated the highest improvement rate, achieving approximately 54.06% with the obtained controller parameters.

In second experiment, a step + square reference signal was applied to evaluate the controllers’ responses to sudden changes, in contrast to the previous reference signal.

Table 6 presents the improvement rates achieved by the optimization methods proposed in this study compared to the Z–N method. For the step portion of the reference signal, the DEA method exhibited the highest improvement rate at approximately 56.01%, followed by ATA (52.81%), PSO (52.63%), CMOSTA (52.12%), and AFFO (41.66%), respectively. Throughout the square reference signal, the controller parameters obtained by using the DEA method achieved the highest improvement rate in reference tracking compared to Z–N, with an improvement rate of approximately 9.5%, followed by CMOSTA with 8.3%, ATA with 7.75%, AFFO with 5.08%, and PSO with 3.45%. As a result, as shown in the table, the controller parameters obtained by using the DEA method, achieved the highest overall reference-tracking improvement of 20.14% compared to the Z–N method across the entire reference signal.

The improvement rates achieved in the final experiment, using the step + sawtooth reference signal, are presented in

Table 7. As can be seen from the table, in the step part, the DEA method performed nearly 52% better reference tracking than Z-N, followed by PSO with 51.35%, ATA with 50.84%, CMOSTA with 50.76% and AFFO with 49.92%. Additionally, for the sawtooth part of the reference signal, which includes both sudden and smooth changes, the DEA method outperformed Z–N, achieving an improvement of approximately 21.92%, followed by CMOSTA with 21.50%, ATA with 20.96%, PSO with 20.06% and AFFO with 15.92%. Finally, across the entire reference signal, the DEA method not only achieves a 36.52% improvement in reference tracking compared to Z–N, but also demonstrated the highest overall improvement among all the optimization methods.