Introduction

The presence of diabetes is precipitously increasing worldwide. In the US alone cases tripled between 1990 and 2010, with the doubling in annual incidence and increased risk of death by 50%, highlighting the importance of further public health efforts (Rowley et al., 2017). Prediabetes arises from a metabolic state characterized by elevated plasma glucose levels that remain below the diagnostic threshold for diabetes. Prediabetes refers to the intermediate condition prior to the progression to TD2M, with patients being at high risk for the onset of T2DM (Beulens et al., 2019). It is driven by factors such as insulin resistance, beta-cell dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and increased oxidative stress, all of which heighten the risk of progression to type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (Luc et al., 2019). Variations in parameters for the diagnosis of prediabetes exist between different organizations which leads to a lack of uniformity. However, the commonality presented is that pre diabetic patients exhibit one or more abnormalities in glucose regulation and are at risk of developing diabetes (Bansal, 2015).

The human gut is composed of over a trillion microbes residing in our gastrointestinal tract, forming a complex microbial community termed the ‘gut microbiome’ (Sidhu & van der Poorten, 2017). Forming a multi-directional axis with various other organs and parts, the gut microbiota interacts with neural, endocrinal, immunological and metabolic pathways in the body (Afzaal et al., 2022). Recent research has theorised that pathogenesis arises from perturbations in the complex microbial communities present in the human gut (Petersen & Round, 2014). Dysbiosis, therefore, refers to the change in composition of resident microbial communities in individuals, with such changes including a decrease in diversity, loss of beneficial microbes or overgrowth of harmful microbes (Petersen & Round, 2014) (Hrncir, 2022). Gut dysbiosis has been linked to various human diseases, including anxiety, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and even cancer (Afzaal et al., 2022). As a result, there has been a growing interest in investigating factors impacting the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota, with genetics, infant feeding, medication, diet and infection emerging from recent research as key influencers thus far (Wen & Duffy, 2017).

Research has increasingly shown that microbes present in the human gut, including the imbalances in their diversity leading to dysbiosis, play a key role in the development of pre-diabetes (Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, the link between the gut microbiome and pre-diabetes serves as a critical marker for enhanced understanding of this disease.

Biomarkers in the Gut Microbiome

Bacteria

The gut microbiome plays an integral role in human physiology, immune system development, digestion, and detoxification reactions. While the inherited genome remains almost stable throughout life, the microbiome is highly dynamic and influenced by multiple factors (D’Argenio & Salvatore, 2015). Dysbiosis of the gut microbial composition serves as a molecular marker, and microbiome composition and stability are highly influenced by the host itself (Zhou et al., 2024). In a normal state, organisms within the lumen of the large intestine contribute to homeostasis; however, gut dysbiosis due to various factors, such as diet, can facilitate disease progression (Bidell et al., 2022). Additionally, the gut microbiome influences the bioavailability of micronutrients by regulating their absorption, particularly phosphorus and calcium (González et al., 2017). Micronutrients, which are commonly found in foods and dietary supplements, are crucial for immune reactions (Barone et al., 2022).

Commonalities across the studies lie in their identification of beneficial species as part of the composition, including Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria. Each species plays an indispensable role in its potential to prevent the risk and incidence of disease through its profound metabolic influence (Hendricks et al., 2023). For example, Bacteroides, a beneficial species, carries out starch degradation. Gene clusters called polysaccharide utilization loci (PULs) in Bacteroides detect and encode surface glycan-binding proteins (SGBPs) and enzymes for digesting polysaccharides (GHs and PLs) (Fernandez-Julia et al., 2021). A study identified 46 bacterial taxa that potentially influence the progression to type 2 diabetes. It highlighted beneficial species such as Bacteroides coprophilus DSM 18228, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis ATCC 15703, as well as the pathogenic species Odoribacter laneus YIT 12061, which were present in higher frequencies in people with the condition (Hendricks et al., 2023).

Inflammatory pathways play a role in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D). For instance, adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), an Enterobacteriaceae bacterium, induces inflammation by adhering to epithelial cells and increasing the expression of pro-inflammatory effectors such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (Guo et al., 2018) (Tsalamandris et al., 2019). Collinsella contributes to diabetes by increasing gut permeability, reducing tight junction protein expression, and inducing IL-17 cytokines (Chen et al., 2016). In a study, the genus Collinsella was significantly increased in the cohort with type 2 diabetes compared to healthy and prediabetic groups (Shah et al., 2015).

Unconjugated bile acids act as signal molecules, like hormones in their ability to activate nuclear receptors. Intestinal microbial dysbiosis negatively impacts the bile acid circuit, and downregulation of bile acid receptors has been linked to insulin sensitivity, increased appetite, and body weight gain (Bensalem et al., 2020) (Kumar et al., 2016).

The gut microbiome has also been studied in relation to pediatric obesity, revealing that specific bacterial communities are associated with obesity. Gut bacteria in obese individuals have been shown to be more capable at oxidizing carbohydrates into storable fat than those in lean youths (Goffredo et al., 2016). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is a potential biomarker for obesity, with an increased ratio leading to an overabundance of pathogenic organisms. The two main phyla in the gut, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, are highly influenced by individual dietary intake and other factors. A study using 16S rRNA gene sequencing data from nine published studies showed consistent results regarding this ratio's role in gut microbiota composition (Magne et al., 2020). A study in a Japanese population using T-RFLP analysis found that obese individuals had a significantly higher Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, with a substantially reduced number of Bacteroides (Kasai et al., 2015). Early intervention through identifying specific alterations in bacterial taxa could influence disease progression. The abundance of specific beneficial taxa impacts digestion, metabolism, and immune function - factors instrumental in dictating how the disease develops and progresses.

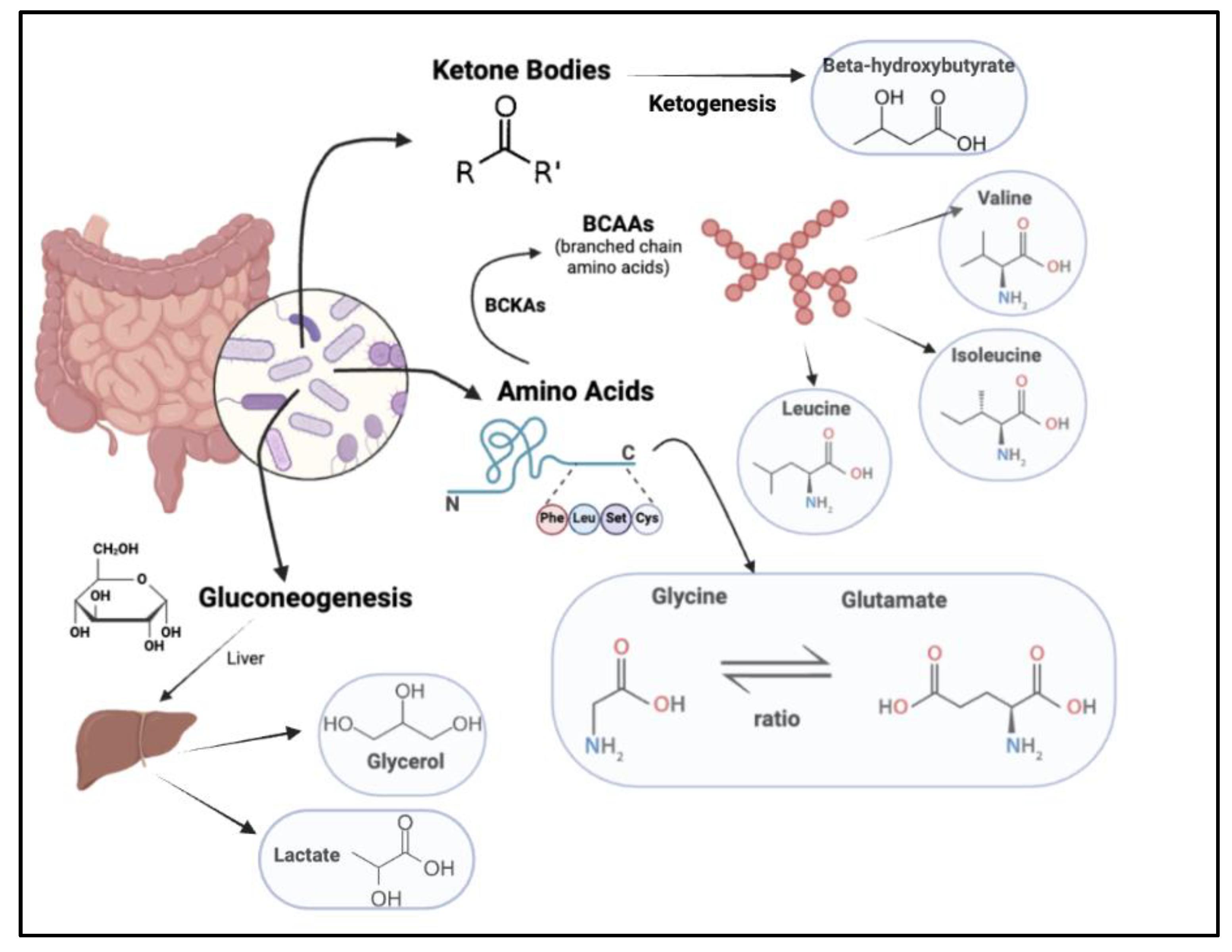

Amino Acids

Studies have shown amino acids to be critical in the prediction of pre-diabetes risk (Newgard et al., 2009). One such class of amino acids is branched-chain amino acids, which further comprise essential amino acids, namely leucine, valine, and isoleucine (Wang et al., 2011). BCAA metabolism occurs in the skeletal muscle, where the enzyme branched-chain aminotransferase forms branched-chain alpha-keto acids (BCKAs). The enzyme branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase reacts with BCKAs to form metabolites participating in anaplerosis. Since anaplerosis is involved in cellular respiration, which is further tied to cellular respiration, we can draw a connection between branched-chain amino acids, by virtue of their role in producing intermediates for the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and insulin resistance and pre-diabetes (Woo et al., 2019). However, while various studies support the hypothesis of a positive association between BCAA and diabetes mellitus and obesity (Newgard et al., 2009) (Huffman et al., 2009), results from other papers tell us otherwise. For instance, a population-based cohort study in Japan presented a negative association between the dietary intake of BCAAs and the risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Data from this study suggested that the supplementation of BCAAs did not weaken the metabolism of glucose in prediabetic subjects, and as a result, could not be seen as a positive correlation.

Another key amino acid correlated with metabolic syndromes is glycine. Glycine levels have been found to be significantly lower in individuals with diabetes as compared to healthy subjects (Wang-Sattler et al., 2012) (Palmer et al., 2015). Research suggests that dietary glycine supplementation increases insulin, thereby improving glucose tolerance and reducing resulting inflammation (Yan-Do & MacDonald, 2017). Recent research has suggested the ability of glycine to directly act on target tissue, such as the endocrine pancreas, by binding to glycine receptors present in the given tissues. Further, evidence has shown the need for glycine and glutamate to activate N-methyl D-aspartate receptors. These receptors are responsible for key brain functions and the regulation of blood sugars, thereby showcasing an interaction between glycine and the brain via NMDA receptors. This enables glycine to influence insulin production and the release of glucose by the liver, and as a result, plays a role in maintaining glucose homeostasis (Yan-Do & MacDonald, 2017).

Ketone Bodies

Another subset of metabolites is ketone bodies, which are acids produced by the liver when fat is used as an energy source in place of glucose (Laffel, 1999). Ketogenesis, a metabolic pathway and process involving a series of reactions, results in the formation of three ketone bodies: acetoacetate (AcAc), beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), and acetone (Salva Yurista et al., 2021). The Metabolic Syndrome in Men (METSIM) study was a population-based study of over 9,000 Finnish men. A segment of the study studied the role of ketone bodies on glucose levels and Type 2 Diabetes. Results recognized increased levels of acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate linked with increased fasting glucose levels, a key indicator of pre-diabetes, and later, Diabetes Mellitus (DM). This correlation can be drawn back to the role of ketone bodies in the body. Here, the inability of insulin to break down glucose for the provision of energy to body parts could trigger the switch to fat as the energy source, resulting in an increase in ketone body production. This complication, when the blood turns acidic as a result of elevated ketone body levels, is termed diabetic ketoacidosis, an ailment most commonly seen with Type 1 Diabetes (CDC, 2024). Research has further indicated the impact of this increased production and use of ketone bodies, in times of low insulin levels, as causing oxidative stress in the mitochondria (Kolb et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Metabolite biomarkers in the gut microbiome, including amino acids, products of gluconeogenesis and ketone bodies.

Figure 1.

Metabolite biomarkers in the gut microbiome, including amino acids, products of gluconeogenesis and ketone bodies.

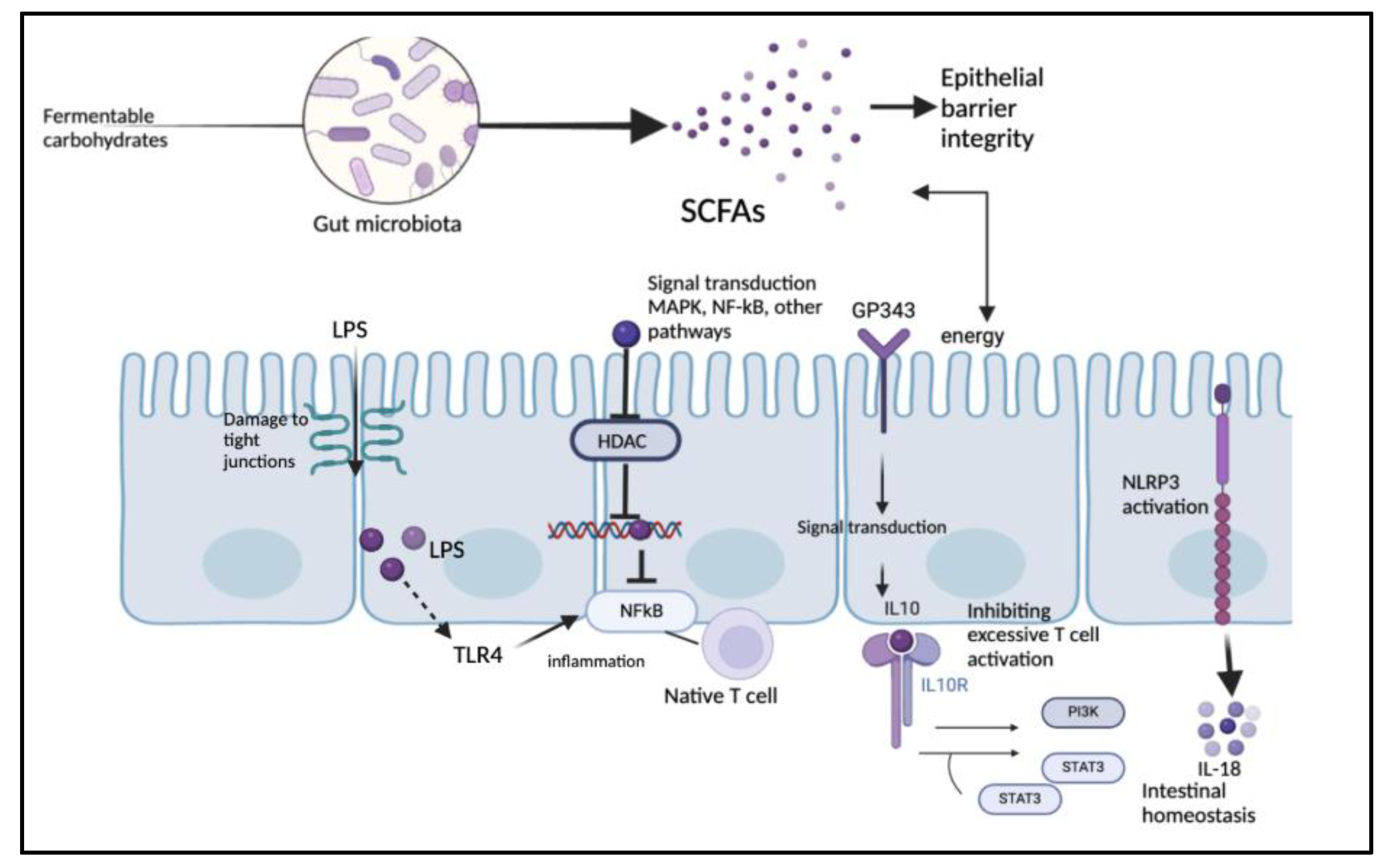

Short Chain Fatty Acids

SCFAs serve as energy sources for colonocytes and play further roles in inflammation, gut permeability, and T-cell activity (Parada Venegas et al., 2019). The bacterial species present impact fermentation processes, resulting in the production of SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which play a crucial role in modulating overall metabolic processes. The gut microbiota primarily produces SCFAs as metabolic products through the anaerobic fermentation of undigested carbohydrates (Rowland et al., 2017). The consumption of fiber directly alters gut bacteria composition, so changes in diet influence the production of SCFAs. Gut barrier robustness is crucial for preventing systemic inflammation, and SCFAs play a notable role in gut barrier stability. Additionally, SCFAs are carried through blood vessels to various organs where they act as signaling molecules, stimulating the release of peptide YY (PYY) and intestinal hormones, which contribute to satiety by enhancing glucose absorption, ultimately leading to reduced food intake (He et al., 2020).

SCFAs also influence the functioning of immune cells, affecting systemic inflammation and metabolic processes (Kim, 2017). For example, butyrate—a main energy source for colonocytes—decreases the expression of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, contributing to improved metabolic function. Butyrate significantly inhibited macrophage activation in liver tissue following ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, suggesting its potential to mitigate systemic inflammation, a key factor in insulin resistance and diabetes progression (Liu et al., 2014). SCFAs may act as signaling molecules by binding to enteroendocrine cell receptors, leading to postprandial gut hormone secretion, which enhances glycemic control (Silva et al., 2013). These receptors affect insulin sensitivity, and SCFAs have been shown to enhance sensitivity by activating certain receptors, thereby reducing the risk of insulin resistance (Salamone et al., 2021). Specifically, SCFAs bind to G-protein-coupled receptors (FFAR2/GPR43, FFAR3/GPR41) (Priyadarshini et al., 2021). By promoting regulatory T-cell expansion and IL-22 production, and influencing pancreatic β-cell function by modulating insulin secretion and β-cell mass through FFA2 and FFA3 signaling, SCFAs influence epithelial integrity and immune homeostasis (Priyadarshini et al., 2021).

Butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, modulating β-defensin expression to participate in epigenetic gene regulation.

Dietary supplementation of butyrate has been shown to prevent high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice (Hong et al., 2016). Butyrate also plays a crucial role in maintaining gut health by enhancing epithelial barrier function, regulating immune responses, and modulating antimicrobial peptide secretion. It strengthens the epithelial barrier by reducing permeability through mechanisms involving HIF stabilization, IL-10 receptor regulation, and reinforcement of tight junction proteins such as occludin, zonulin, and claudins. Additionally, butyrate promotes mucus layer integrity by increasing MUC2 production in the colon. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, enhance gut antimicrobial defenses by stimulating the secretion of antimicrobial peptides like LL-37 and β-defensins, primarily through activation of the mTOR pathway and STAT3 phosphorylation.

In terms of immune regulation, butyrate facilitates the differentiation of naive T lymphocytes into anti-inflammatory Tr1 cells that produce IL-10. It also shifts macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype in response to microbial molecules such as lipopolysaccharides (Martin-Gallausiaux et al., 2020).

The shift towards organisms such as Roseburia intestinalis and Eubacterium rectale, which produce butyrate, has been observed in conjunction with increased butyrogenesis on a high-fiber, low-fat diet. Increased populations of D3+ intra-epithelial lymphocytes and CD68+ lamina propria macrophages were also observed in such diets, suggesting increased inflammation in the absence of saccharolytic breakdown of fiber (Morrison & Preston, 2016).

Proteins

Proteins are macromolecules comprising one or more chains of amino acids, playing a key role in the production of enzymes and hormones, supporting the immune system in the form of antibodies, and enabling the construction and repair of tissue (Brody, 2020). Proteins are broken down into various smaller molecules, including peptides, which are a string of 2 to 50 amino acids, the building blocks of proteins (Forbes & Krishnamurthy, 2023). Certain peptides have been investigated as improving glucose regulation in Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) (Yu et al., 2025), while others serve as key biomarkers for the early detection of prediabetes and diabetes mellitus.

A German population-based study, KORA F4/FF4, was used to identify proteins that enable the prediction of incident prediabetes or incident T2DM. Tests on individuals not taking medication for diabetes were conducted, with each protein marker being graphed on four ailments: fasting glucose (FG), fasting insulin (FI), 2-h-glucose (2hg), and HOMA insulin resistance (IR). Of the markers studied, the most significant proteins included Mannan-binding lectin serine peptidase (MASP), Glycosylphosphatidylinositol specific phospholipase D1 (GPLD1) and apolipoprotein E (apoE), all of whom showcased significant positive associations with the four ailments. Adiponectin shared a significantly inverse association with the ailments, while proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP), apolipoproteinC-III, and apolipoproteinA-IV were positively associated with only certain ailments (Huth et al., 2018). Another study indicated the correlation between MASP1 and thrombospondin 1 (THBS1) with pre-diabetes and 2-h-glucose levels (von Toerne et al., 2016).

The significant correlation between pre-diabetes and the proteins MASP and MASP1 can be understood by tracing the origin of these molecules. Mannan-binding lectin (MBL) belongs to the subfamily of proteins termed C-type lectins. While not obvious, considering the protein is produced by the liver, studies have linked MBL and the gut microbiome, indicating its impact on microbiota composition, inflammation, and immune responses such as phagocytosis (Choteau et al., 2016) (Wu et al., 2020). MBL-associated serine proteases include MASP1, MASP2, MASP3, and MAp44, of which the former two in particular are linked with blood glucose levels. Diabetes is seen as a leading cause of elevated MBL levels, MASP1 and MASP2. MBL has a tendency to bind to certain sugar patterns, one of which happens to be fructoselysine, a product of glycation. Glycation refers to the binding of sugars to proteins. Hyperglycemia, a condition characterized by high blood sugar levels, accelerates glycation, considering there is a higher number of sugars present for binding to take place. As a result, higher blood sugar leads to increased levels of MBL, MASP1, and MASP2, which then form Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs) as sugars bind to proteins during glycation. However, these proteins are not confined to the above set of processes resulting from diabetes. AGEs are commonly associated with key diabetic complications, as their binding to MBL and MASPs results in the activation of MASP1 and MASP2. These two proteins are further known to interact with blood coagulation factors, including fibrinogen and prothrombin. This interaction results in the formation of fibrin, a protein that forms the mesh present during blood clotting. Therefore, the elevated levels of activated MASP1 and MASP2 remain a risk for vascular complications, all a result of diabetes (Jenny et al., 2015).

While not present in the gut microbiome, C-peptide was also significantly associated with diabetes. A set of 125 pre-diabetic patients was studied in one investigation, with some patients having the additional ailments of impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). 58 of the 125 participants had elevated C-peptide levels (Venkatesh et al., 2018). Another study investigated cancer mortality risk and deaths, considering the many associations linking diabetes and cancer. When examining the all-cause cancer deaths, the study revealed consistent associations with serum C-peptide concentrations, though this correlation was only found in women (Hsu et al., 2013).

A 2021 study aimed to identify novel diabetic markers, specifically serum proteins linked to inflammation, which the researchers hypothesized to be linked to metabolic complications. Of the 7 markers, four were already published in existing literature: cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14), cluster of differentiation 99 (CD99), clusterin (CLU), and serum amyloid A2 (SAA2) (Yang et al., 2021).

CD14, in particular, is known for modulating inflammation-driven insulin resistance (José Manuel Fernández-Real et al., 2011). CD14 is a multifunctional reporter, whose primary role is the sensing of inflammatory signals. Both soluble CD14 (sCD14) in the blood and CD14 on cell surfaces work to amplify the inflammatory signal, activating toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). The activation of TLR4 triggers a series of intracellular events ultimately resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which contribute to systemic inflammation, an immune response. In this way, the development of insulin resistance can be tied to CD14, as a result of its implications on systemic inflammation, which then impairs the ability of the body’s cells to respond to insulin.

The three novel markers identified by the study were mixed-lineage leukemia 4 (MLL4), laminin subunit alpha 2 (LAMA2), and plexin domain containing 2 (PLXDC2). When studying the functions of these protein markers in the body, we can carve a scientific justification for their linkage with diabetes. For instance, MLL4 is known to interact with transcription factors towards the regulation of islet beta-cells function (Yang et al., 2021). T2DM occurs when beta cells of pancreatic islets are unable to fulfill their role in producing insulin for glucose regulation. Therefore, we see the evident reasons behind the correlations of these protein markers to pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus.

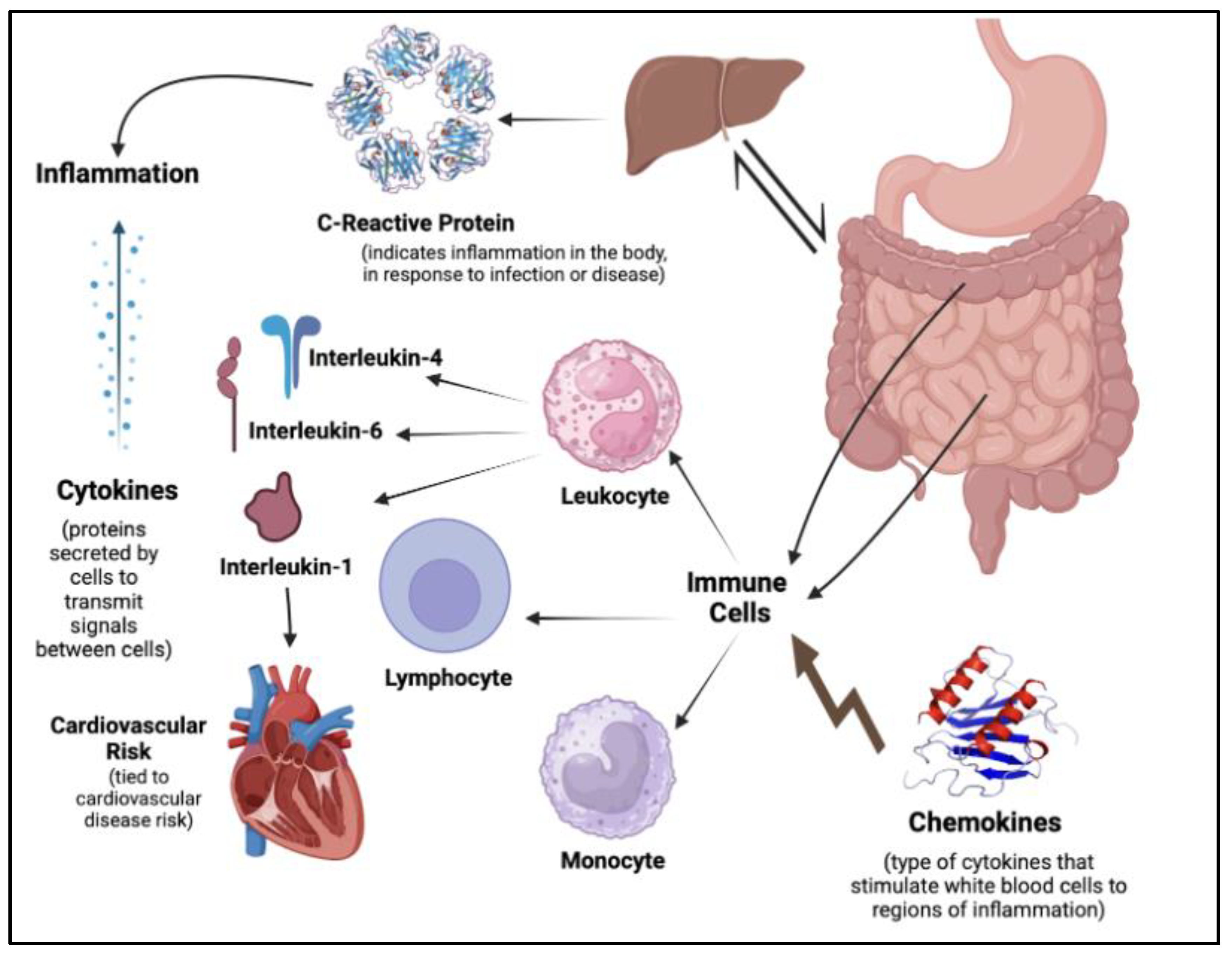

Cytokines and Inflammatory Markers

Cytokines are small proteins released by cells for the purpose of signaling. They are closely connected to the immune system and support the interaction of cells. A broader term, cytokines are broken down into various sub-classes, often based on constituents part of the immune system. For instance, lymphokines are cytokines made of lymphocytes, monokines are made of monocytes, and interleukins are made of leukocytes. Further, cytokines are closely tied to inflammation, an immune response to injury or infection, with their typology extending to pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory (Zhang & An, 2007).

Chronic conditions, including Diabetes Mellitus, are often associated with low-grade inflammation (Menzel et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

Inflammatory markers and cytokine biomarkers, including immune cells and chemokines.

Figure 2.

Inflammatory markers and cytokine biomarkers, including immune cells and chemokines.

Oxidative stress is another closely tied phenomenon to inflammation, a term referring to the imbalance between the production of oxygen-reactive species (ROS) or free radicals and antioxidants or the ability to detoxify these reactive products (Pizzino et al., 2017). Inflammation biomarkers become critical to detect and track progress in oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Common markers include fibrinogen, C-reactive proteins (CRP), and cytokines such as interleukins and their receptors (Menzel et al., 2021).

A study was conducted on 560 participants, divided into three metabolic condition states: 215 participants had pre-diabetes, 126 had Type 2 Diabetes, and 219 had normal glucose levels. Results indicated significantly higher levels of C-reactive protein, immunoglobulin E (IgE), tryptase, interleukin-4 (IL-4), and interleukin-10 (IL-10) in T2DM and pre-diabetes compared to normal glucose. Further, an odds ratio was conducted to compare the relative odds of diabetes mellitus (DM) given different levels of inflammatory markers. Higher levels of the markers mentioned above were associated with a higher risk of both prediabetes and T2DM, highlighting the causal relationship shared between inflammatory markers and metabolic syndrome (Wang et al., 2016).

The Gutenberg health study is one of the most comprehensive health studies conducted. A population-based investigation, a part of the study worked with glucose homeostasis and the ailments linked to it. 15,010 individuals were involved, with three subsets categorizing them: normoglycemia, pre-diabetes, and diabetes. The study explored the variations in concentration of inflammatory and immune biomarkers between the three groups. Results indicated higher concentrations in diabetes of key immune cells, including granulocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes, along with cytokines such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and interleukin-18. Inflammatory markers such as neopterin, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogens were also found elevated from normoglycemia to pre-diabetes and diabetes (Grossmann et al., 2015).

Insulin resistance and impaired beta-cell function are often present in pre-diabetes. Elevated levels of blood glucose, an ailment known as hyperglycemia, can increase markers of chronic inflammation, and further augment the growth of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Luc et al., 2019). Inflammation has further been tied to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, with the expression of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines resulting in the accumulation of lipids in blood vessels, thereby resulting in the development of CVD and atherosclerosis (Matheus et al., 2013). For instance, interleukin-1 (IL-1) has been found to play a key role in cardiovascular disease. Encapsulating two proteins (interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta), IL-1 is produced as a result of cell injury or stress by macrophages, among other synthesizers. IL-1 targets cells of the immune system, including monocytes, lymphocytes, and granulocytes, while also affecting epithelial and endothelial cells, among others. Its stimulation during inflammation results in the prolonged inflammatory responses produced by the immune cells it targets (Vicenová et al., n.d.). Further, IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta have been found to impair insulin signaling pathways, whose primary role is to allow communication of insulin with other cells. By disrupting phosphorylation patterns of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, there is a decreased expression of key components in insulin-regulated glucose transport, thereby increasing the risk of insulin resistance and T2DM (Fève & Bastard, 2009). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is another example of a cytokine impairing the phosphorylation of insulin receptors and insulin receptor substrate-1. IL-6 gives rise to the suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS-3), a potential inhibitor of insulin signaling, impairing the ability of insulin to regulate glucose levels (Stein et al., 2017).

The composition of the gut microbiota is known to have an influence on the presence of pro-inflammatory-cytokine-producing immune cells. This, in turn, impacts the formation of a pro-inflammatory environment, which has previously been outlined to lead to insulin resistance and CVD risk (Al Bander et al., 2020). C-reactive protein (CRP) was found previously to be correlated to pre-diabetes. Studies have indicated its role in insulin resistance and dysfunction. Nitric oxide is critical for insulin function. CRP suppresses insulin-induced nitric oxide production, thereby preventing the proper functioning of insulin. Further, the inhibition of phosphorylation of Akt, a key protein kinase involved in insulin signaling, weakens insulin response to glucose and communication with cells (Xu et al., 2007).

Another investigation looked at tuberculosis (TB) patients with pre-diabetes mellitus (PDM) and their profile of cytokines and chemokines. Chemokines are a family of signaling proteins that facilitate leukocyte migration. Patients with co-existing TB and PDM had higher levels of key chemokines, including chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-1 (CCL1), CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL11, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-1 (CXCL1), CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 (Anuradha Rajamanickam et al., 2024). Other studies have explored the similar space of inflammatory markers and DM, including previously studied and novel biomarkers to predict the progression from normoglycemia to pre-diabetes (Brahimaj et al., 2017).

Another class of cytokines is adipocytokines, produced by adipose tissue in the body. The role of adipose tissue in diabetes has been outlined in great depth. In obesity, the physiological functions of adipose tissues are unsettled, leading to the release of free fatty acids (FFAs) and the increased production of proinflammatory mediators (Luc et al., 2019). FFAs activate TLR-4 in adipocytes and macrophages, leading to the increased expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) (Nishida & Otsu, 2017). As a result, the inflammation of adipose tissue can be found to cause impaired insulin functions and the development of metabolic disorders. TNF-alpha has been found in key studies (Moller, 2000) (Plomgaard et al., 2007) (Huang et al., 2022) as a major adipocytokine correlated to beta-cell function (HOMA B) and insulin resistance tests (HOMA IR) in Type 2 Diabetes (Swaroop et al., 2012).

However, results from other studies discussed above (Wang et al., 2016) oppose such a connection. Hence, the field of novel and existing inflammatory biomarkers of pre-diabetes requires increased validation and further investigation (Luís et al., 2022).

LPS

Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) are glycolipids found in the outer membrane of most Gram-negative bacteria. They are composed of lipid A, core oligosaccharide, and O antigen, which results in them stimulating the immune system through interaction with Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4), triggering cytokine activation (Candelli et al., 2021). In the gastrointestinal tract, microbiota residing in the cell wall release signaling byproducts, including LPS, which exerts both local and systemic effects through circulation (Mohr et al., 2022). An increase in intestinal permeability due to potential dysbiosis of gut microbiota leads to the enrichment of bacteria that produce LPS. This allows LPS to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation and promoting insulin resistance (Lee et al., 2018). Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) levels were notably increased in patients with T2DM and morbid obesity, showing strong associations with insulin sensitivity. Weight loss led to a decrease in LBP levels (Moreno-Navarrete et al., 2011). LBP functions as a lipid transfer protein, mediating the movement of LPS monomers from micelles to receptor sites on target cells (Tobias et al., 1997). Higher levels of serum LPS and zonulin (ZO-1) contribute to endotoxemia, indicating increased gut permeability and systemic inflammation. Endotoxin enters the bloodstream, triggering an inflammatory response (Jayashree et al., 2013). LPS can result in the activation of innate immune responses, leading to an inflammatory state within adipose tissue, a key factor in the development of insulin resistance. NF-κB signaling plays a role in regulating inflammatory responses to LPS in adipocytes (Creely et al., 2007). A study of 45 T2DM patients in Chennai, India, revealed a positive correlation between LPS activity, zonulin levels, and various metabolic markers. Serum LPS levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Jayashree et al., 2013). In T2DM patients, LPS activates monocytes, with CD163 serving as a surface marker for this activation (Khondkaryan et al., 2018). A study on rats fed a high-fat diet for four weeks showed chronically elevated plasma LPS levels, reaching the threshold for metabolic endotoxemia (Cani et al., 2007). The permeability of Caco-2 monolayers, a model used to assess intestinal barrier function, was affected by the serotype-specific modulation of LPS.

Certain bacterial species contributed to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other chronic inflammatory conditions through potent LPS responses, which compromised tight junction integrity and increased permeability (Stephens & von der Weid, 2019). A shift in the redox metabolism of macrophages is induced by LPS, increasing glycolytic fluxes and enhancing the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which functions parallel to glycolysis to generate NADPH and ribose-5-phosphate (Venter et al., 2014). LPS also promotes the Warburg effect—aerobic glycolysis—which upregulates ATP production and generates biosynthetic intermediates to meet the metabolic demands of activated macrophages (O’Neill, 2011). LPS can activate protein kinase C (PKC), which in turn stimulates JNK and IKK, contributing to insulin resistance (IR). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, LPS reduces Akt phosphorylation while increasing the expression of iNOS. The elevated iNOS levels enhance nitric oxide production, which disrupts glucose uptake and promotes IR. This LPS-induced IR is mediated through S-nitrosation of key insulin signaling proteins, including the insulin receptor β subunit (IRβ), IRS-1, and Akt (Aula et al., 2012). LPS increases cAMP production, which is involved in the regulation of proglucagon expression. Additionally, it undergoes posttranslational processing via PC1/3 and PC2, and immune cell exposure to LPS induces these processes (Nguyen et al., 2014). Triggered by an increase in Ca²⁺ in β-cells, cAMP amplifies insulin secretion (Tengholm & Gylfe, 2017). In a cross-sectional study, 93 age-matched middle-aged urban Gambian women were recruited to assess metabolic endotoxemia in obesity and diabetes.

LPS levels were highest in the obese-diabetic group compared to lean and obese non-diabetic groups. IL-6 levels showed a positive association with both obesity and diabetes. The reduction in EndoCAb IgM levels in obese and obese-diabetic women may result from the degradation of IgM-LPS complexes, which continuously neutralize persistent endotoxin leakage from the gut (Hawkesworth et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

SCFA and LPS biomarkers in the gut microbiome, including immune response and gut barrier integrity.

Figure 3.

SCFA and LPS biomarkers in the gut microbiome, including immune response and gut barrier integrity.

Table 1.

Summary of key biomarkers in the gut microbiome with greater or lower abundance levels in pre-diabetic patients. Biomarkers emerge from the following classes - Bacterial taxa, Short chain fatty acids, Metabolites, Proteins, Lipopolysaccharides, Proteins, Inflammatory Markers, Cytokines, Chemokines.

Table 1.

Summary of key biomarkers in the gut microbiome with greater or lower abundance levels in pre-diabetic patients. Biomarkers emerge from the following classes - Bacterial taxa, Short chain fatty acids, Metabolites, Proteins, Lipopolysaccharides, Proteins, Inflammatory Markers, Cytokines, Chemokines.

Computation

Data Collection

Prior to the development of new sequencing technologies, microbial studies were limited to individual genomes. For instance, in 1995, the first genome of the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae was sequenced (Fleischmann et al., 1995). To identify biomarkers within the gut microbiota taxa, it is necessary to integrate molecular profiling techniques. 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing is a prominent technique for characterizing the diversity and composition of the gut microbiome for its applications. The 16S rRNA gene is highly conserved in bacteria, and through sequencing this gene, researchers gain insights into the classification of bacterial taxa and can measure microbial community structures (Janda & Abbott, 2007).

For prediabetes research, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, particularly targeting the V4 region, is a widely recommended method for profiling the human gut microbiome. Non-invasively collected stool samples provide data for researchers to analyze the gut microbiome spectrum, offering insights into potential microbial biomarkers for prediabetes. This approach provides high resolution and is cost-effective, making it ideal for identifying bacterial genera like Bacteroides, which correlate with prediabetes (Osman et al., 2018).

16S identifies bacteria at a genus level but does not offer specificity on details crucial to understanding microbial roles in disease - species, strain, and functional characterization (Byndloss et al., 2024). Whole-genome metagenomics are necessary when identifying associations with gut microbiota and phenotypic information like HbA1c. Given this, high resolution metagenomic approaches become essential.

The reduction of cost with improved technologies allowed for the study of tens of thousands of microbes, as compared to individually analyzing a few species. More importantly, this allowed scientists to study microbial communities in their natural habitats. This advancement led to the emergence of the term ‘metagenomic’, the study of sequence data taken directly from the environment (or ‘metagenome’). The origin of this data is heterogeneous microbial communities, specifically uncultured microorganisms (Wooley et al., 2010). The gut microbiome presents its own sets of challenges, especially with regard to the complexity of host and environmental factors impacting the variation in volume of given microbes present. A Dutch population-based study, LifeLines DEEP cohort represents one example of a metagenomic analysis of over 200 endogenous and exogenous factors. Spanning 1179 participants, it covered factors including dietary habits, medication use, and lifestyle. While most features presented some correlation, the magnitude of this correspondence varied. While certain factors showed low or modest intercorrelation, others, such as the use of antibiotics, were highly associative with microbe composition (Zhernakova et al., 2016).

The hologenome theory of evolution refers to the idea that the holobiont, an animal or plant along with their associated microorganisms, are a unit of selection in evolution (Zilber-Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2008). The human genome is one such example, as it works alongside a collection of microbial genomes present in the gut microbiome. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology represents the first major breakthrough in computer technologies that supports the sequencing of millions of DNA fragments (Satam et al., 2023).

Second-generation sequencing allows for the characterisation of thousands of microbial taxa, while third-generation technologies, such as single-molecule real-time sequencing, support the production of long reads (at the scale of tens of thousands of bases). Alongside improvements in sequencing technologies, advances in computational capacity along with open collaboration allowed for the understanding of microbe taxonomy. For instance, metagenomic Whole Genome Shotgun (mWGS) data helped researchers realise significant biological processes these microbes were involved in (Yen & Johnson, 2021).

Another area of exploration for gut microbiome data is metabolomics, a field studying metabolites, small molecules that impact host biochemical functions. The metabolome, in particular, refers to the characterization of these small molecules in the cell on a quantitative and qualitative level. Common metabolites include glucose, cholesterol, and ATP, each of which participates in critical metabolic reactions in the body (Chen et al., 2019).

The Human Microbiome Project Consortium conducted a study to analyse the microbiomes of 4788 samples, emerging from nearly 250 adults. They then reconstructed the abundance of pathways present in the metagenomes, serving as a depiction of the metabolic properties of the entire human microbiome. Several metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, ribosome and translational machinery, and ATP synthesis, were most abundantly present across individuals (The Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012).

Another investigation showed how metabolomes of the gut microbiome are highly predictive of gut dysbiosis, a key marker mentioned above towards pre-diabetes. The group used a dataset curated from a previous data collection study, predicting the community enzyme function profiles. This supported the creation of community metabolomes, which could then be fed into a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm for training. Based on their classification into dysbiotic and non-dysbiotic, the algorithm was able to predict the metabolomics behind gut dysbiosis. This case further leads us to believe that there may be a distinctive metabolome for various health states (Larsen & Dai, 2015).

Machine Learning

Initially, ML was utilized for simpler taxonomic classification and microbial community analysis, with early studies focusing on model development for the classification of microbial features. However, over time, the availability of data has significantly increased through projects like the Human Microbiome Project leading to the development of sophisticated techniques for analyzing complex microbiome data, including compositional data analysis and feature selection methods. Recent studies have integrated microbiome data with other omics data, enhancing predictive models for improved disease detection. This provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease causation (Marcos-Zambrano et al., 2021).

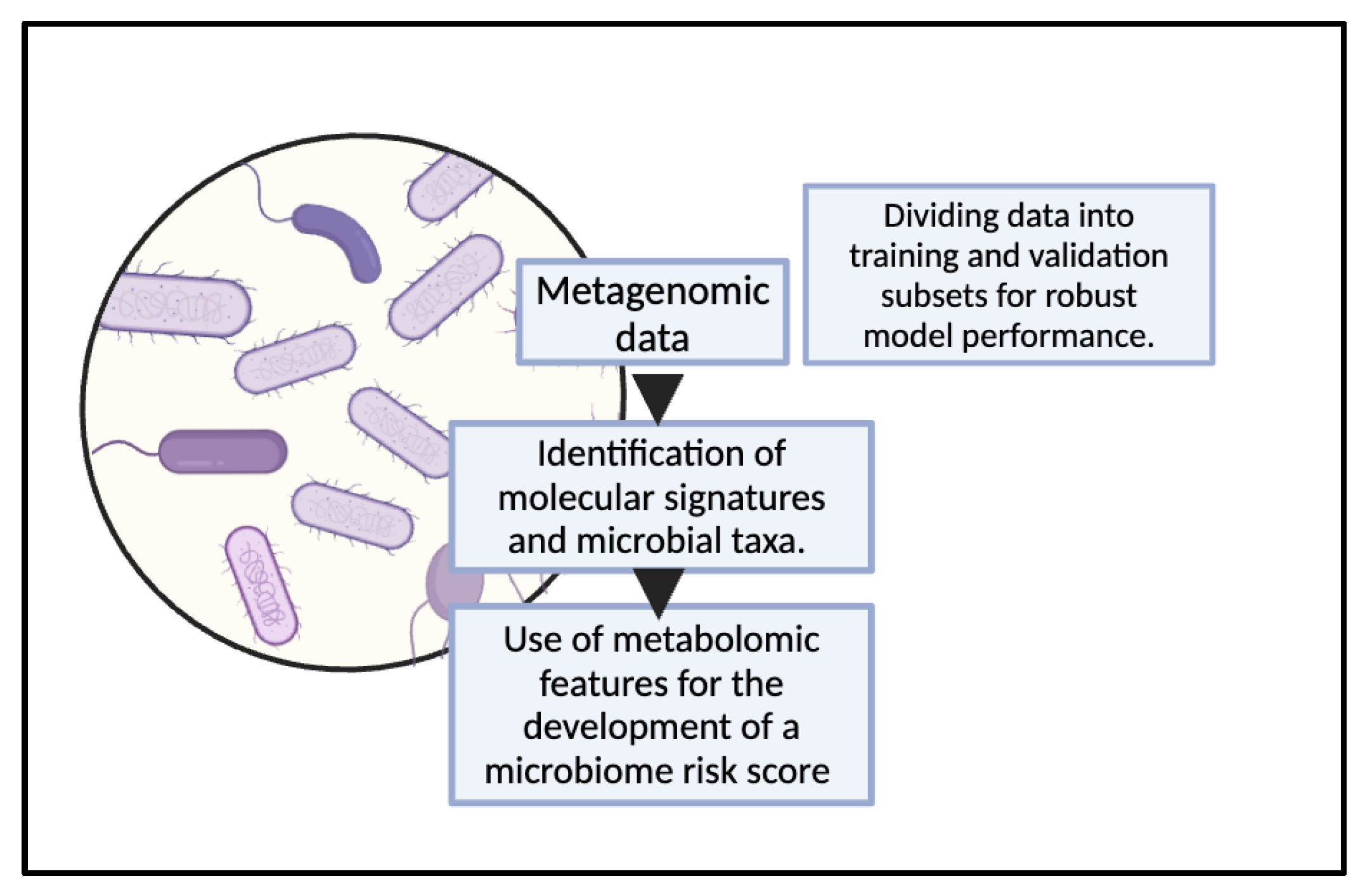

Figure 4.

Utilization of metagenomic data for the development of ML models for gut microbiome analysis.

Figure 4.

Utilization of metagenomic data for the development of ML models for gut microbiome analysis.

Early assessment of the risk of developing diabetes is crucial, and machine learning (ML) technology offers novel models for predicting this risk, facilitating personalized diagnosis and prevention strategies. The integration of gut microbiota parameters with artificial intelligence (AI) models enables the development of predictive tools that can be used as primary prevention measures to minimize the risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) (Caballero-María et al., 2025). Machine learning algorithms can leverage the ubiquity of heterogeneous data. They can train on existing datasets to map known dependencies or further discover novel patterns. It is an effective tool for correlating relationships between gut microbiota composition and prediabetes risk. For example, decision tree-based methods such as Random Forest and LightGBM have proven invaluable in gut microbiome analysis for prediabetes research. These techniques can identify molecular signatures, uncover potential patient stratifications, and ultimately generate accurate predictive models for phenotypes. Additionally, deep learning approaches are increasingly being applied to gut microbiome studies with their ability to reveal patterns in complex data (Li et al., 2022). For example, graph convolutional networks (GCNs) have proven accurate in modeling complex interactions, contributing to an understanding of gut microbiome composition by analyzing microbial networks and identifying key microbial communities. Adapting GCN frameworks to microbiome data allows researchers to leverage techniques like attention mechanisms and network analysis to reveal how various taxa interact and influence overall microbiome diversity. These approaches provide valuable insights into the dynamics of the gut microbiome (Long et al., 2020). Machine learning was used to identify gut microbiome features with potential relevance for prediabetes research. A microbiome risk score (MRS) was developed based on data from three Chinese cohorts, assessing its association with baseline adiposity, dietary factors, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) risk. This relationship was validated using germ-free mice colonized with microbiomes representing different risk scores, and the MRS–T2D association was further replicated in two independent cohorts. The study identified 11 microbial taxa as novel predictive factors for T2D risk. This approach demonstrates how machine learning can reveal key microbial markers associated with metabolic disorders (Gou et al., 2020). Machine learning was used to identify gut microbiome features with potential relevance for prediabetes research.

A microbiome risk score (MRS) was developed based on data from three Chinese cohorts, assessing its association with baseline adiposity, dietary factors, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) risk. This relationship was validated using germ-free mice colonized with microbiomes representing different risk scores, and the MRS–T2D association was further replicated in two independent cohorts. The study identified 11 microbial taxa as novel predictive factors for T2D risk. This approach demonstrates how machine learning can reveal key microbial markers associated with metabolic disorders (Gou et al., 2020). Analyzing the microbiome profiles of 410 Mexican patients using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and machine learning algorithms, researchers identified bacterial taxa associated with type 2 diabetes development. For prediabetes, genera such as Anaerostipes, Intestinibacter, and Veillonella were found to be relevant.

The study utilized Random Forest models to classify patients and demonstrated the contribution of specific taxa in predicting disease states. For example a low abundance of Anaerostipes and Intestinibacter and a high abundance of Escherichia/Shigella and Collinsella were linked to prediabetes, suggesting that results showing dysbiosis can serve as a predictive marker for disease progression (Neri-Rosario et al., 2023). In another study, LASSO reduced 178 metabolite features to identify key T2DM biomarkers, including laspartate and phenyllactate. The KTBoost model achieved 0.938 accuracy, 0.971 sensitivity, and a 0.965 AUC, demonstrating a strong discrimination ability. SHAP analysis showed that lower laspartate levels were strongly linked to T2DM, increasing prediction probability (Arslan et al., 2024). Through integrating microbiome profiles, ML revolutionizes early diabetes risk assessment, enabling precise strategies that can drive early intervention and disease prevention.

Integration and Modeling

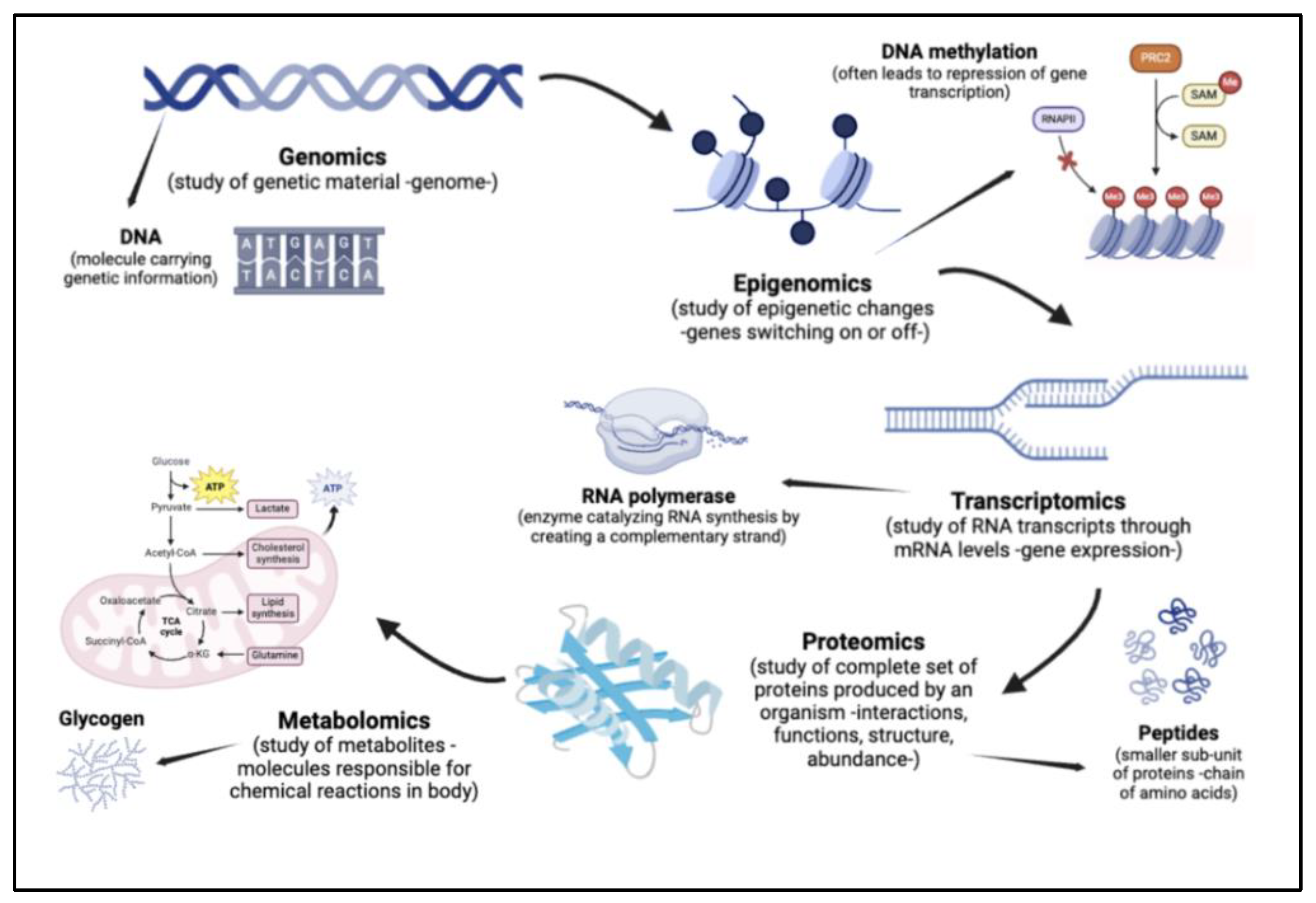

Multi-Omics

The suffix ‘omics’ refers to the comprehensive assessment of molecules in a given organism or part of an organism. For instance, microbiomics is the study of all microorganisms (including bacteria, viruses, and fungi), collectively known as the microbiota, in a community present in the host. The rapid development of the field of multi-omics was catalysed by the creation of large-scale genome-wide association studies, enabled by a technology called genotyping arrays. This had a massive contribution to integrative genetics, a field that takes genomic and molecular approaches to study model organisms. The inclusion of other omics technologies supported the creation of multiple omic layers, hence the term multi-omics (Hasin et al., 2017).

Figure 5.

Connecting key omics disciplines based on their areas of study, and the resulting conclusions drawn from their data.

Figure 5.

Connecting key omics disciplines based on their areas of study, and the resulting conclusions drawn from their data.

While investigating organisms using multi-omic tools, one can take three approaches. Genome-first focuses on the contribution of variations in a given gene as contributing to a disease. This is based on the outlook that the genome is a causal factor for health ailments, as compared to a consequence. Phenotype-first views the pathways contributing to disease, wherein different factors in disease development are understood through correlations with given observable characteristics in an organism (phenotypes). Finally, environment-first approaches look at the environment as a primary variable, studying its role in influencing pathways and genetic variation. Physical links to disease are investigated using an environmental factor, such as diet or exercise, as a variable (Hasin et al., 2017).

The combination of various omics technologies supports in-depth studies in relation to gut microbial communities (Daliri et al., 2021). One such example is the combination of metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, studying both DNA and RNA sequences. For instance, a study explored how, despite having similar types of microbial species, monozygotic twins had major differences in the genes present and transcription levels of these genes (Turnbaugh et al., 2010). Another merger between metagenomics and metaproteomics helps in predicting the activity of microbes based on the functions of proteins expressed by them. One such study investigated how there was a significant increase in microbial carbohydrate metabolising enzymes in patients experiencing gut dysbiosis in T2DM. Further, a reduction in host protein levels was seen, specifically those that support gut barrier functions (Zhong et al., 2019). A metagenomics-metabolomics approach is also highly insightful, as it investigates the molecular interactions connecting microbes with their hosts. For instance, the analysis of fecal microbiota between extremely obese and normal weight subjects demonstrated key distinguishers between microbial profiles of the two groups. This study also showed significant links between gut-brain and gut-liver axes, and dietary interventions (such as weight loss) (Nogacka et al., 2020). All of the above studies, among countless others, highlight the significance of such multi-omic approaches on the study of the gut microbiome, including for pre- and Type 2 diabetes (Daliri et al., 2021).

A longitudinal study spanning nearly four years helps us understand the true scope of multi-omics technologies in its application to our understanding of the gut microbiome. It followed 106 participants, collecting blood, stool, and nasal swabs for molecular and microbial profiling. The blood, in particular, was fractionated into peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs), which supported the study of RNA sequencing, plasma, for identifying metabolites and proteins present, and serum to track cytokines and growth factors. The results yielded unique associations between gut bacteria and insulin resistance, as compared to insulin sensitivity (Zhou et al., 2019).

Metabolic Modelling

A metabolic network is composed of various chemical reactions, specifically those involving the metabolism of molecules with the help of enzymes. Such networks are made up of metabolic pathways, which form product(s) through the help of successive reactions. Through the course of such pathways, metabolites either synthesize to form larger molecules, in a process known as anabolism, or break down into smaller molecules, through catabolism. This combination of combining and degrading allows for the storage and/or release of energy (Lengauer & Hartmann, 2007).

Prior to the rise in genomic understanding and use, metabolic pathway reconstruction was much simpler. However, with the rapid growth of omics research, the rise in data volume rendered the field much more complex. Today, biological pathways are created using a set process, beginning with the selection of a database that holds information on the given reactions. The data is recreated into a visualisation of the network, and compressed to reduce data size. This then allows researchers to search for a particular pathway or process, using one of three methods. The breadth-first search involves finding the shortest path between two metabolites. Contrasting this is the depth-first search, which moves forwards and backwards to identify fundamental pathways, termed elementary flux modes, involved in the creation of a given molecule. Finally, retrosynthesis methods integrate metabolic pathways into an organism to synthesize a target molecule. This approach remains critical for applications in drug discovery (Petrovsky et al., 2023).

Biological pathways are visualised as complex networks, wherein vertices represent molecules while edges depict chemical transformations (Petrovsky et al., 2023). The representation of such metabolic pathways is critical in identifying trends and differences between patient groups. For instance, one study highlighted key alterations in the metabolic pathways of patients with pre-diabetes. For instance, the overexpression of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-1) caused the attack of beta cells by the immune systems, which thereby impaired blood glucose control. Another example was the excessive activation of Akt/mTOR, which promoted damage to the DNA and skin barrier, along with the entry of bacteria into the body. A key pathway that was rendered abnormal was the metabolism of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI). The study also highlighted how these changes were seen to augment in Diabetes Mellitus (Chang et al., 2024).

A cross-sectional study built an altered map of biological processes seen in pre-diabetes and T2DM, with the help of proteomics. The study focused on five organs for tissue samples, namely the liver, skeletal muscle, pancreatic islets, serum and visceral adipose tissue (VAT). Notably, biological processes linked to the immune system’s regulation were seen to be greatly upregulated in pre-diabetes. Further, the pancreatic islets in pre-diabetes patients saw an elevation in lipid metabolism pathways, while a significant decrease was linked to cellular respiration, among other processes, in VAT. Levels of the metabolic processes of alcohol, carbohydrates, and steroids, were increased in the liver, along with amino acids, fatty acids, and lipids. This clearly supports increasing evidence of the associations and major changes seen in metabolic pathways of pre-diabetic and diabetic patients (Diamanti et al., 2022).

Treatments

Early Intervention

As was previously discussed, pre-diabetes and the consequent progression to T2DM is linked with severe side effects, including, most notably, heightened risk of cardiovascular disease. This linkage in particular can be traced back to insulin resistance, which has been proven to have effects on blood pressure, blood coagulation, and lipid profile, among others. It was further associated alongside hypertension (excessive blood pressure), obesity (excessive body fat) and dyslipidemia (abnormal lipid levels in the bloodstream). A combination of lifestyle changes and medical therapy was seen to reduce the likelihood of progression from insulin resistance in its nascent stages to T2DM. This renders early detection and intervention critical to prevent further advancement of the lifestyle disease (Fonseca, 2007).

Taking the example of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), an ailment possessed by 20 to 40% of patients with Diabetes Mellitus. The disease leads to progressively declining health of the kidney, with its effects on renal health being largely irreversible. Timely intervention, in such cases, is necessary for proper management and potential safeguarding of otherwise partial or complete failure of the organ’s functionality (Radbill et al., 2008). However, this is extended to prediabetes as well. Up to 70% of pre-diabetic patients progress to type 2 diabetes, in as little as five years (Prakoso et al., 2023). A simulation model estimated a 7.6% reduction in progression to T2DM from pre-diabetes-associated fasting glucose concentrations with the help of targeted intervention (Beulens et al., 2019). Specific to the gut, early intervention has supported the possibility of the microbiome’s restoration to a normal state (Zhang et al., 2021). For instance, dietary interventions have been seen to improve microbiome health, immune response of the host, and even cardiologic and metabolic profiles, even being referred to as novel therapeutics for DM (Shoer et al., 2023). Therefore, early detection and intervention is critical to supporting the speedy and plausible recovery and reversal of both pre-diabetes, and its associated adverse effects for bodily health.

Personalised Medicine

Diabetes treatments have historically been generalized; however, not all patients respond to the same treatments in the same manner. Despite similar clinical profiles, responses can vary significantly. Understanding biomarkers and identifying patterns in disease subtypes help optimize interventions (Klonoff, 2008). One example of how individual markers can be analyzed to predict glycemic responses for tailored dietary interventions is a study involving 800 participants, including gut microbiota composition. Researchers developed an ML algorithm that predicted glycemic responses, leading to the development of personalized dietary recommendations to effectively manage blood glucose levels, outperforming generalized traditional dietary treatments (Zeevi et al., 2015). Personalized medicine involves targeted patient interventions with the goal of maximizing individualized benefit. Advances in genome-wide arrays and genetic sequencing have enabled the identification of gut bacterial taxa, providing critical insights into disease mechanisms and treatment responses, which are expected to enhance personalized care for Type 2 diabetes (Pearson, 2016).

Diet

Diet plays a critical role in prevention and intervention for pre-diabetes and T2DM respectively, considering the source of the ailment lies in inability to modulate glucose, a molecule ingested most commonly via food into the human body. For instance, the prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes significantly varies across different eating patterns of individuals. While T2DM is prevalent in 7.6% of non-vegetarians, it is only present in 6.1% of semi-vegetarians, and an even lower 2.9% in vegans (McMacken & Shah, 2017). This clearly demonstrates the importance of diet on diabetes among other metabolic syndrome conditions. Various studies have also outlined the ability of lifestyle modifications, including diet, to support enhanced glycemic control (Bouchard et al., 2014). Therefore, the aim of dietary treatment remains a “change in eating habits to prevent and/or delay the disease” (Pascual Fuster et al., 2021).

Weight reduction is another critical objective for diabetic patients, considering nearly 80% of people with T2DM are obese. Measuring calorie intake is an example of a dietary method as a treatment for DM. Overall, diets which are plant-based, tend to be most beneficial for the reduction of cardiovascular risk, a major side effect of diabetes. These are namely characterised by low cholesterol and saturated fatty acid levels, and high in fiber among other nutrients (Pascual Fuster et al., 2021).

Nutrition therapy refers to the treatment of a disease through a modification in the nutrition intake, both quantitatively and qualitatively (Evert et al., 2019). Studies have shown that lifestyle intervention reduces incident risk for diabetes in patients with IGT by as much as 58% (Knowler et al., 2002). Further, an absolute decrease in A1c levels by 2% in T2DM highlights the effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy (MNT) interventions. In fact, researchers have described these to be at a similar or even higher effectiveness to traditional medication for diabetes (Evert et al., 2019).

Clinical trials comparing conventional diets with a vegan pattern saw a reduction in HbA1c levels by 1.23 points, a 21.2% fall in LDL cholesterol levels, and a 6.5 kilogram weight reduction as a result of a plant-based diet (Barnard et al., 2006). Another popular diet plan is the High-Carbohydrate, Low-Fat (HCF) pattern, which in one clinical study led to half of the participants discontinuing insulin (Anderson & Ward, 1979).

One large-scale study took 21,561 individuals, separating them into three classes based on their eating patterns (omnivore, vegetarian, vegan). They saw significant variations in the gut microbial composition as a result of these eating habits. Using species-level genome bins (SGBs), a method of classifying microbial genomes, the group was able to compare relative abundance of each SGB between the three groups. Omnivore microbiomes saw an overrepresentation of SGBs to aid the digestion of meat, including Alistipes putredinis, needed for protein fermentation, and Ruminococcus torques, an indicator of inflammation. In contrast, vegan microbiomes saw an increase in SGBs specialising in fibre degradation, such as Lachnospiraceae, a butyrate producer. Finally, in contrast to vegan participants, Streptococcus thermophilus, a dairy component, was seen in higher concentration in vegetarian microbiomes. The above differences clearly highlight the evident impact of diet on gut microbiome composition, including the presence and concentration of different bacterial taxa (Fackelmann et al., 2025). Another study used metagenomic data from shotgun sequencing, yielding similar conclusions. In contrast to the above investigation, it compared the gut microbiome composition between a Mediterranean (MED) diet and a personalised postprandial-targeting (PPT) diet. The study identified 24 microbial species which were significantly different between the two diets, with most of them impacting clinical outcomes. For instance, two bacteria, UBA11774 sp003507655 and UBA11471 sp000434215, were reported to play a role in the association between adherence of the PPT diet and positive clinical outcomes. These included lower levels of HDL-cholesterol and reduced values from the HbA1c test (Ben-Yacov et al., 2023).

Personalised medicine was also seen to have great potential when using diet as a treatment for pre-diabetes. Based on unique gut microbiota profiles, individuals were provided a diet plan, with pronounced improvements in hyperglycaemic and inflammation parameters. An increase in the abundance of certain bacteria, including Bifidobacterium angulatum and Levilactobacillus brevis supported the enhancement of the above metrics. Most importantly, diet plans can supplement anti-diabetic medication, making them extremely effective as a treatment option alongside more traditional methods. No adverse effects were reported by participants, highlighting the efficacy and safety of such treatments for patients with pre-diabetes and T2DM (Gopalakrishna Kallapura et al., 2024).

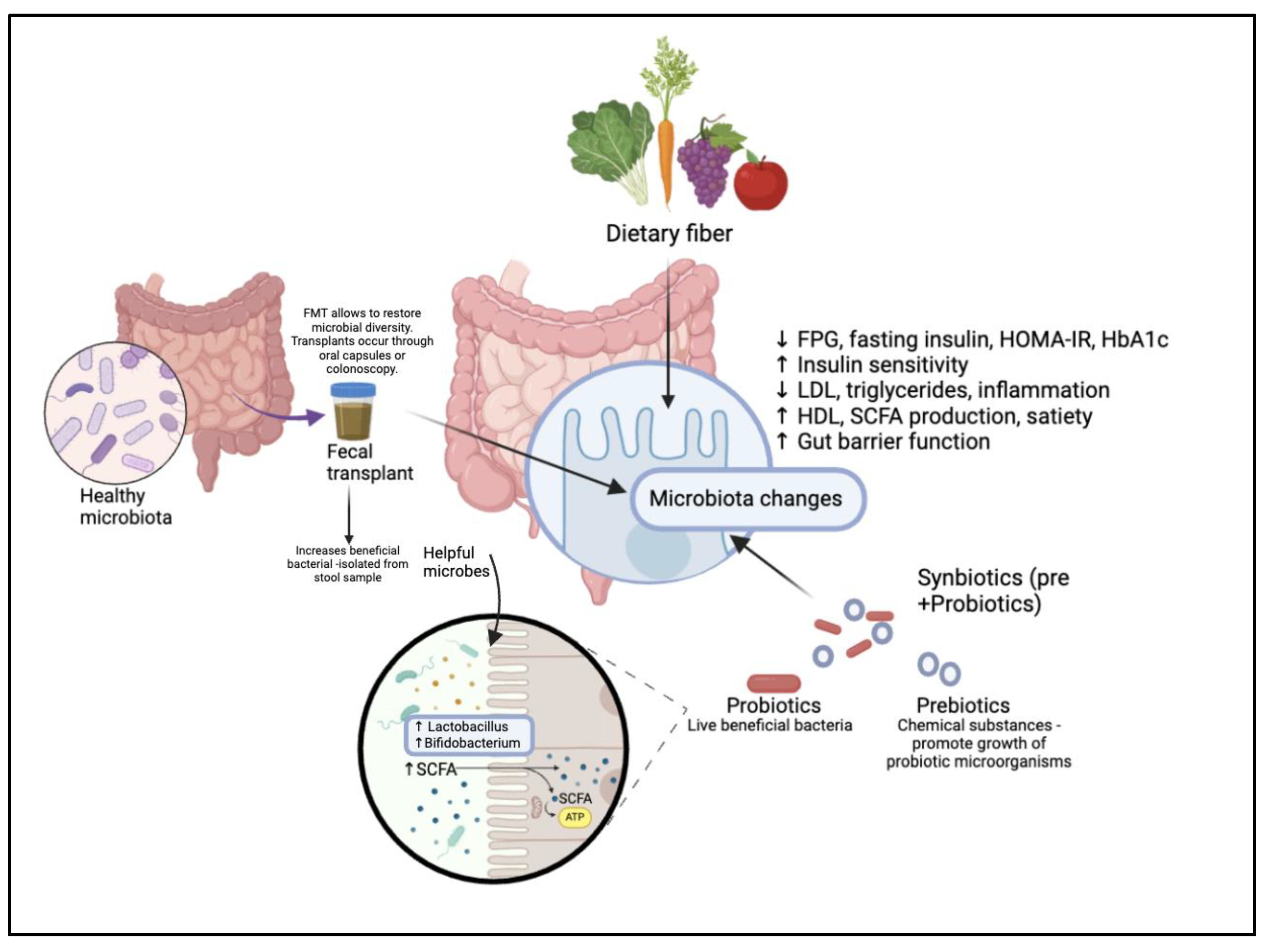

Fecal Transplants

FMT originated in 4th-century China, where it was first recorded as a treatment for severe diarrhea, later becoming a well known treatment for gastrointestinal and non-communicable diseases. FMT restores gut microbiota balance by transferring healthy donor fecal material into a recipient’s gastrointestinal tract. Emerging research suggests its potential for managing metabolic disorders like diabetes. Strict donor screening is essential to minimize the risk of transferring viral, bacterial, or fungal pathogens. By refining donor selection and deepening our understanding of microbial interactions, FMT can be optimized for safer and more effective microbiota-targeted therapies (Wang et al., 2019). Multiple studies have shown significant improvements in patients with diabetes following FMT administration. β-cell function was maintained, islet dysfunction was alleviated, and key markers such as fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c, insulin resistance, uric acid, and triglyceride levels exhibited notable reductions, while body weight, BMI, and glycemic control steadily improved. Additionally, plasma metabolites underwent substantial changes, enhancing insulin function and glucose metabolism. Total protein, albumin, and hemoglobin levels stabilized, and patients reported better nutritional status and relief from constipation (Zhang et al., 2024). In one study under sterile conditions, fecal samples from donor mice were collected and administered to diabetic mice, demonstrating the potential of FMT as a treatment. Testing through ELISA and related indexes such as HOMA revealed improvements in insulin resistance and pancreatic islet β-cell function. Additionally, FMT inhibited β-cell apoptosis and reduced inflammatory responses (Wang et al., 2020). The necessity for FMT is reinforced by the rapid global surge in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). With nearly 33% of the adult population being overweight or obese and diabetes cases projected to rise from 425 million to 692 million by 2045, the role of intervention is evident. While FMT is generally considered a safe treatment, occasional minor risks and side effects, such as post-treatment obesity, have been documented. Nevertheless, studies demonstrating its therapeutic effects, including significantly improved glycemic control, highlight its potential as a treatment for metabolic syndrome and warrant further research into its mechanisms (Napolitano & Covasa, 2020).

Figure 6.

Methods of intervention for prediabetes and diabetes: The effect of dietary consumption, fecal transplants, and synbiotics on restoring gut dysbiosis.

Figure 6.

Methods of intervention for prediabetes and diabetes: The effect of dietary consumption, fecal transplants, and synbiotics on restoring gut dysbiosis.

Synbiotics

Prebiotics were first observed by the Greeks and Romans in fermented food consumption. Later, in 1907, Nobel laureate Élie Metchnikoff put forward their health benefits, and over the 20th century, the term "probiotic" evolved to encapsulate discoveries about the potential of live microorganisms in promoting gut health (Nagpal et al., 2013). Probiotics contain live bacteria with beneficial effects, while prebiotics are growth factors that promote the proliferation of these beneficial microorganisms. Together, they synergistically aim to enhance the growth of targeted species like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, improving gut health. In combination with the addition of substrates such as lactose, which support bacterial growth, they form a synbiotic. This combination results in a greater overall effect, specifically designed to support the newly introduced beneficial bacteria and improve gut microbiota balance (Kearney & Gibbons, 2017).

Probiotics improve gut microbiota balance, currently offering immune regulating effects to reduce the risk of diseases linked to gut barrier dysfunction and inflammatory conditions (Isolauri et al., 2004). These improvements notably involve reductions in fasting blood glucose levels, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and improved antioxidant status. Additionally, probiotics strengthen gut barrier function and regulate immune responses, contributing to better lipid metabolism by decreasing LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels while increasing HDL cholesterol. They also modulate immune responses by lowering inflammatory markers such as TNF-α and CRP, leading to a reduction in systemic inflammation (Sáez-Lara et al., 2016). Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that selectively promote the growth and activity of specific gut bacteria, improving gut barrier function, enhancing host immunity, and reducing inflammation. Their introduction has been shown to increase short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, promote satiety, support weight loss, and prevent obesity, ultimately contributing to improved metabolic health and glycemic control (Slavin, 2013). In a double-blind, randomized clinical trial investigating synbiotic and probiotic supplements in 120 prediabetic participants over 24 weeks, significant reductions were observed in biomarkers such as fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and fasting insulin levels. The synbiotic group showed a notable decrease in HOMA-IR values, along with improvements in insulin sensitivity. Additionally, both probiotic and synbiotic groups experienced a reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, demonstrating their potential efficacy for prediabetes management (Isolauri et al., 2004). A diverse gut microbiota is essential for a healthy intestinal environment, while dysbiosis—marked by reduced probiotic abundance and an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria—contributes to worsened metabolic health. Understanding how synbiotics can be effectively administered to selectively regulate intestinal homeostasis presents a promising therapeutic strategy for restoring balance. When accurately dosed, synbiotics can help modulate gut microbial patterns, offering potential benefits for T2DM patients (Jiang et al., 2022).

Antidiabetic Drugs

Antihyperglycemic (or antidiabetic) drugs refer to a set of agents that support the increase of insulin secretion, improvement in insulin sensitivity and/or reduction in carbohydrate absorption (Antidiabetic Agent - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, n.d.). Antidiabetic drugs have been viewed as both complementary and substituting medication forms to other treatment types ; however, their effectiveness, applicability and resulting side effects remain key areas requiring further study and investigation. Nevertheless, various drugs remain potential options for patients with pre-diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, T2DM or other interlinked ailments.

Metformin has resulted in positive results, including reduction of body mass index (BMI) and an improved cholesterol profile (Bansal, 2015). Notably, a 45% risk reduction of T2DM was seen in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance with the help of the drug (Lily & Godwin, 2009). Glitazones are oral anti-diabetic agents that are critical in driving certain metabolic pathways, including those related to glucose metabolism (Vulichi et al., 2021). Of its various types, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone remain more commonly used agents. Rosiglitazone saw a reduction in diabetes incidence risk by 60%, though it was linked to major side effects such as higher incidence of heart failure and an increase in weight by an average of 2.2 kilograms (Dagenais et al., 2008) (Gerstein et al., 2006). In the ACT NOW study, pioglitazone was also found to reduce diabetes risk in impaired glucose tolerance subjects by over 70% (DeFronzo et al., 2011). Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are linked to a reduction in glucose absorption, primarily resulting in a decrease in blood glucose levels post-food intake (Bansal, 2015). Acarbose and voglibose are two common inhibitors, with similar side effect profiles including diarrhea and flatulence (Chiasson et al., 2003) (Ryuzo Kawamori et al., 2009). In fact, in the case of voglibose, the study saw a discontinuation of 7% of subjects due to adverse effects (Ryuzo Kawamori et al., 2009). GLP-1 analogs are a type of drug which increase resistance to the degradation of DPP4, an enzyme whose functions include blood glucose level regulation (Chaudhury et al., 2017). Exenatide and liraglutide are examples of GLP-1 analogs which support sustained weight loss in obese subjects, thereby reducing the prevalence of pre-diabetes (Astrup et al., 2011) (Astrup et al., 2009). Finally, orlistat is a drug used in the treatment of obesity, with a relative risk reduction for diabetes of nearly 40% (Torgerson et al., 2003). It does this through the inhibition of dietary fat absorption (Bansal, 2015).

The biggest challenge posed, despite the high efficacy of certain antidiabetic drugs, are the adverse effects resulting from their use. While they remain highly effective in addressing single symptoms associated with or caused due to pre-diabetes and DM, the resulting side effects towards linked body systems and organs serves as a major demerit for such medication as a treatment option (Mahmoud et al., 2024).

Challenges

Lifestyle and diet play a fundamental role in shaping the microbiome, individuals in varying conditions in early stages and adulthood are subjected. constant changes in composition (Dong & Gupta, 2019). Additionally, interindividual variability in gut microbiome composition has been highlighted by cross sectional studies (Vandeputte et al., 2021), this can limit the effectiveness of computational methods and can lead to generalization and ineffective treatments.

While many correlational connections between bacterial taxa and T2DM have been established, limitations exist in presenting casual relationships (Li & Li, 2023). Understanding the precise role species play in affecting glycemic response is fundamental to inform intervention. Studies have indicated the role of ethnicity in gut microbiome composition (Dwiyanto et al., 2021), highlighting the gap in diverse data across population demographics and geographic locations. Further, the numerous factors contributing to changes in the gut microbiome composition, including a diverse range of environmental and lifestyle features (Su & Liu, 2021), makes it extremely challenging to isolate the role of a single factor on disease development and gut dysbiosis. This also complicates our understanding of the impact of given treatment options for chronic diseases like diabetes (Su & Liu, 2021).

As a result of the complexities of the gut microbiome and variability in its composition between individuals, the lack of standardization in procedural methods makes the transfer of knowledge and insights across studies extremely challenging (Kashyap et al., 2017). This further negatively impacts the ability to translate lab research into clinical therapeutics and diagnostics, as a result of inadequate protocols in place.

Training models becomes difficult in the face of approximately 10-100 trillion microorganisms within the gut microbiota. Due to this diversity it becomes difficult to integrate specific microbes into classification (Mabwi et al., 2021). The necessity for supervised learning further hinders the ability for systems to achieve reproducible results with limited training and testing data sample sizes. Factors such as label distribution and experimental protocols must be controlled to attain valuable and accurate results. While efficient, these models prove to be difficult to train (Giuffrè et al., 2023).

Machine learning, as described in previous sections, remains a highly potent tool for analysing microbiome data collected. However, these models remain highly intensive, with the needs for computing power often not being met within research centers (Filardo et al., 2024). Further, the need for bioinformaticians makes new-age computation tools harder to integrate due to the need for interdisciplinary understanding, which is often lacking in healthcare research settings (Filardo et al., 2024). The prevalence of ‘black box’ set-ups for machine learning models further prevent their integration into interdisciplinary scopes, such as supporting biological research (Kumar et al., 2024). With regards metagenomics, a frequent challenge faced by groups is the incomplete metadata found in public repositories and datasets, with inconsistent data between studies further making it challenging for cross-study comparisons (Kumar et al., 2024).

Observed overlapping microbiome signatures across diseases suggest shared disease responses rather than distinct association. This highlights the need for deeper analysis incorporating both patient characteristics and biomarkers. This need for high-throughput sequencing produces large, multidimensional data, posing challenges in statistical analysis, false discoveries, data storage, and computational demands (Sharpton et al., 2021).

Furthermore, in terms of studies focusing on pre-diabetes, the lack of a specific definition impacts the variability and lack of standardisation in investigation methodologies, especially with regards sample groups and data collection (Echouffo-Tcheugui & Selvin, 2021).

Future Directions

The integration of multi-omics data remains a highly potent field interacting with gut microbial analysis for pre-diabetes. The use of metadata across omics technologies supports the enhanced understanding of causal relationships and consequences arising from both metabolic syndrome and its associated treatments.

Alongside this novel approach, diversity in samples for the data collection of human gut microbiomes remains essential for the heightened relevance and reliability of conclusions drawn. Increasing representation of patient profiles, including geographic, cultural, and biological features, alongside the modulation of environmental and lifestyle factors, allows for an improved knowledge base on which treatments and therapeutics can more accurately be tailored.

In terms of microbial data, uniform collection and sequencing standards must be in place to support reproducibility of tests (Kashyap et al., 2017). Currently, various frameworks have been developed, such as the “Standardisation of Gut Microbial Analysis” paper by the European commission (Toussaint et al., 2024). However, the need for their adherence in studies is imperative for the eventual universal standards for protocols and procedures specific to gut microbiome research.

The gap between the demand for bioinformaticians and clinicians can be addressed through user-friendly interfaces that enable seamless data integration. For example, CBI provides platforms that facilitate data sharing between clinicians and researchers (Bellazzi et al., 2012).

Future directions should include comprehensive data, such as medication and diet, while also considering interactions with key metabolites. Advancing genome assembly and bioinformatics tools is essential, along with increasing human studies to confirm findings and improve model training (Byndloss et al., 2024).

Through the development of efficient computational systems that reduce high costs associated with data collection and computing power, personalised treatments can be rendered more accessible to pre-diabetic patients. This allows for more effective detection and intervention, improving patient health outcomes and resulting treatment(s).

Conclusions

Multiple studies conclude the efficacy of dysbiosis as a biomarker for pre-diabetes and T2DM. Further, computational approaches support the in-depth analysis and further intervention to prevent the progression to Type 2 Diabetes. The adversities discussed can be countered with potential treatment options, focused on modifying the gut microbiota to restore diversity and regular healthy composition of the microbiome. Despite the aforementioned challenges, including high volumes of data, complex interplay of internal and external factors, and lack of standardisation, the gut microbiome remains a potent lens through which promising avenues of detection and intervention arise.

Abbreviations

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharides |

| IBD |

Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| T2D |

Type 2 Diabetes |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic Acid |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| NGS |

Next Generation Sequencing |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| mWGS |

Metagenomic Whole Genome Shotgun |

| T-RFLP |

Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism |

| rRNA |

Ribosomal RNA |

| BCAA |

Branched-Chain Amino Acid |

| BCKA |

Branched-Chain Alpha-Keto Acids |

| NMDA |

N-methyl D-aspartate |

| AcAc |

Acetoacetate |

| METSIM |

Metabolic Syndrome in Men |

| BHB |

Beta-Hydroxybutyrate |

| a-HB |

Alpha-Hydroxybutyrate |

| TNF |

Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| FFAR |

Free Fatty Acid Receptor |

| CD |

Cluster of Differentiation |

| CRP |

C-reactive Proteins |

| ROS |

Oxygen-Reactive Species |

| SOCS |

Suppressor of Cytokine Signalling |

| IRS |

Insulin Receptor Substrate |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |