Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

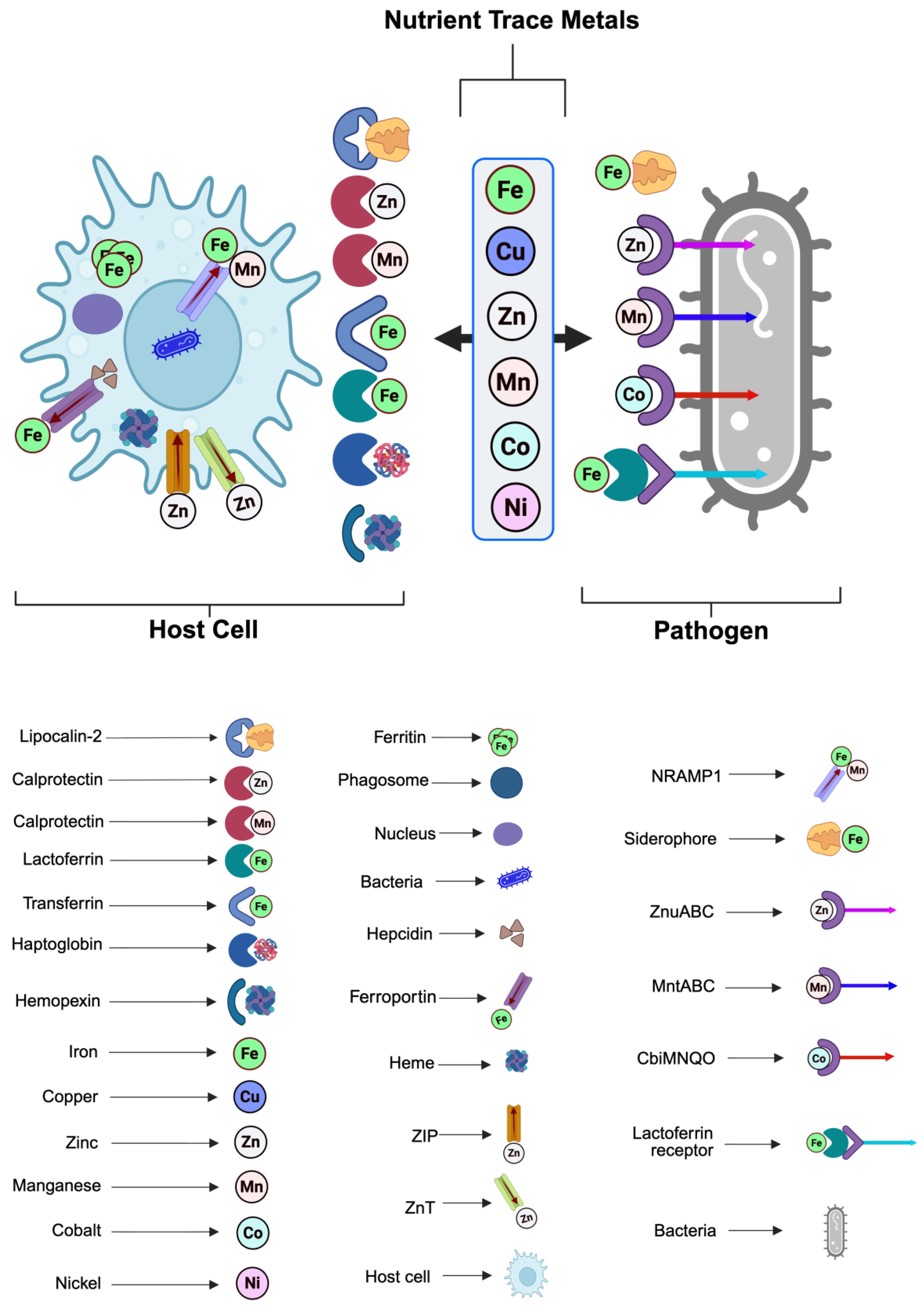

2. Mechanisms of Nutritional Immunity

2.1. Metal Homeostasis and Disruption

2.2. Metabolic and Hormonal Regulation

2.3. Resource Competition

2.4. Host Regulation of Nutrient Transporters and Storage

2.5. Direct Antimicrobial Actions

3. Nutrient-Specific Strategies in Nutritional Immunity

3.1. Iron Limitation: A Key Mechanism of Nutritional Immunity

3.2. Zinc and Manganese: Essential Metals in Host-Pathogen Interactions

3.3. Copper Toxicity and Homeostasis

3.4. Magnesium Limitation and Membrane Integrity

3.5. Sulfur and Nitrogen Metabolism

3.6. Vitamin Sequestration

3.7. Carbon Source Restriction

3.8. Amino Acid Deprivation and Metabolic Reprogramming

4. Nutritional Immunity in the Context of Specific Pathogens

4.1. Extracellular Pathogens: Confronting Nutrient Sequestration Head-On

4.2. Intracellular Pathogens: Navigating the Nutrient Desert Within

4.3. Eukaryotic Pathogens: Complexity, Redundancy, and Immune Evasion

4.4. Comparative Genomics: Mapping the Evolutionary Landscape of Nutrient Acquisition

5. Pathogen Adaptation and Evasion

5.1. Pathogen Strategies to Overcome Nutritional Immunity

5.1.1. Siderophore Diversification and Stealth

5.1.2. Metal Transporter Upregulation

5.1.3. Metabolic Rewiring and Carbon Source Flexibility

5.1.4. Amino Acid Scavenging and Biosynthesis

5.1.5. Host Manipulation and Immune Evasion

5.2. Evolution of Nutrient Acquisition Mechanisms in Pathogens

5.2.1. Gene Expansion and Operon Architecture

5.2.2. Horizontal Gene Transfer and Convergent Evolution

5.2.3. Reductive Evolution in Obligate Intracellular Pathogens

6. Therapeutic Implications

6.1. Targeting Nutrient Availability for Infection Control

6.2. Novel Therapeutic Strategies Based on Nutritional Immunity

6.3. Nutrient-Based Therapies for Specific Infections

6.4. Host-Directed Therapies to Enhance Nutritional Immunity

6.5. Diagnostic Biomarkers of Nutritional Immunity

7. Future Directions

7.1. Emerging Research Areas in Nutritional Immunity

7.2. Translating Nutritional Immunity Into Clinical Applications

7.3. Nutritional Immunity in the Context of Global Health and Malnutrition

7.4. Nutritional Immunity and the Microbiome

8. Conclusion

|

Significance. Beyond metals and small metabolites, host lipids, including fatty acids, cholesterol, phospholipids, and lipid droplets (LDs), are both critical nutrient sources and structural building blocks for many pathogens, and they actively shape intracellular niches [290]. Host control over lipid trafficking and storage therefore functions as a form of nutritional immunity that can limit pathogen growth or, paradoxically, be subverted to enhance pathogen persistence [291,292]. Mechanisms and host responses. Infected cells reprogram lipid metabolism. For example, macrophages and other innate cells ramp up the uptake and esterification of cholesterol, synthesize neutral lipids, form LDs, and alter fatty-acid flux. LDs act as metabolic hubs and may be “weaponized” by the host, for example, by concentrating antimicrobial lipids or lipid-derived mediators, or, if hijacked, provide a nutrient depot for invaders [292,293,294]. Pathogen strategies. Intracellular bacteria and parasites exploit host lipids in multiple ways. These include import and catabolism of host cholesterol as seen in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [125], redirection of host fatty-acid metabolism [293], and interception of LDs and secretory trafficking to obtain membranes and energy as observed in Chlamydia, Salmonella, and Toxoplasma [290]. Dedicated bacterial systems such as M. tuberculosis cholesterol uptake and degradation pathways, coordinated by proteins like LucA enable utilization of host sterols for persistence [125,290,295]. Consequences and translational outlook. Targeting lipid access or utilization with statins, inhibitors of microbial cholesterol catabolism, modulation of LD biology, or host-directed metabolic reprogramming, offers promising adjunctive strategies to traditional antimicrobials especially in the wake of rising antibiotic resistance. However, given that lipids are central to host physiology, therapeutic windows are narrow and require precision [291,293]. |

| Nutritional immunity has been predominantly studied in bacterial and fungal pathogenesis. Yet, accumulating evidence illuminates its relevance during viral infections. Unlike bacteria, viruses do not directly acquire metals for replication but rely heavily on host cellular metabolic processes that are metal-dependent, including enzymatic activity, DNA/RNA synthesis, and immune signaling [296]. Therefore, the host–virus interaction with nutritional immunity is largely indirect, mediated through regulation of metal homeostasis, nutrients redistribution, and modulation of host immune responses. Iron metabolism is strongly implicated in viral infections. Many viruses, including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV), exploit host iron-dependent pathways for replication [297]. High iron levels can enhance viral replication, while iron limitation via hepcidin upregulation or therapeutic chelation can suppress viral spread [298]. Conversely, iron overload in conditions such as hemochromatosis predisposes patients to more severe viral infections [299]. Zinc plays a twofold role in antiviral defense and viral pathogenesis. For instance, intracellular zinc bolsters antiviral immunity by promoting interferon signaling and stabilizing antiviral proteins, while zinc-finger antiviral protein (ZAP) directly restricts viral RNA [300]. Supplementation of zinc has been shown to lower the replication of coronaviruses, influenza virus, and HIV in vitro [300,301]. However, pathogens may oppose host zinc redistribution strategies. For instance, HIV can alter zinc transporter expression to favor its persistence in macrophages [300]. Copper and manganese also intersect with viral infections. For example, copper possesses intrinsic antiviral activity, disrupting viral proteins and nucleic acids, a property exploited in both innate immunity and copper-based surface coatings for infection control [302]. Meanwhile, manganese, is critical for the cGAS–STING pathway, a pivotal antiviral sensing mechanism, and its depletion impairs interferon-mediated viral clearance [303]. Taken together, nutritional immunity in viral infections represents a subtler and more host-centric phenomenon than in bacterial infections, where the pathogen directly competes for metals. Viruses rewire host nutrient availability to their benefit, while the host leverages nutrient redistribution to limit viral replication and enhance immune defense. This emerging field opens new therapeutic avenues, including modulation of iron homeostasis, zinc supplementation, and copper-based antivirals which are already under investigation in both preclinical and clinical settings [304,305,306,307,308]. |

|

A common clinical axis. Nutritional immunity is fundamental to several clinical syndromes and therapeutic dilemmas, including anemia of inflammation, infection risk in iron-overloaded hosts, and both the promise and perils of altering metal metabolism in patients. Anemia of inflammation. Proinflammatory cytokines (notably IL-6) trigger hepatic hepcidin, which downregulates ferroportin and hides iron within macrophages and hepatocytes [309]. This adaptive response restricts extracellular iron available to pathogens but also causes hypoferremia and anemia that can worsen patient outcomes if prolonged [7,308]. Managing anemia in infection therefore requires balancing limiting pathogen access to iron with host oxygen-carrying needs. Iron overload and infection susceptibility. Patients with hereditary hemochromatosis or transfusional iron overload have an elevated risk for siderophilic infections because excess labile iron overwhelms host sequestering mechanisms [310,311]. Similarly, iron chelation can be protective in some infections but may exacerbate others if it becomes bioavailable to microbes via their strategies of recapturing withheld iron [7,56,312]. Therapeutic manipulation: promise and caveats. Clinical interventions that modulate metal availability, including localized metal delivery, systemic chelators, or hepcidin-modulating agents, are evolving. However, risks include inducing iatrogenic anemia, impairing immune cell function, or unintentionally supplying accessible iron to pathogens [313,314]. There is need, therefore, for translational strategies such as localized delivery and pathogen-directed siderophore conjugates to be precisely targeted and tested in context-specific clinical trials. |

|

|

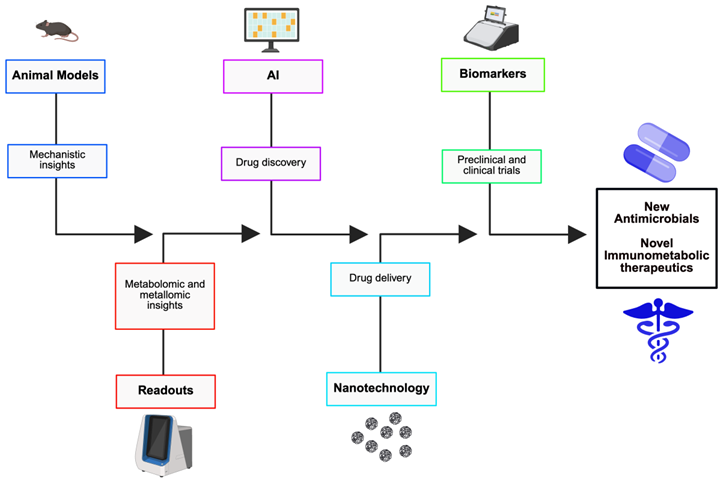

Convergence of fields. Nutritional immunity presents mechanistic targets for new therapeutics. However, the realization of that potential will be facilitated through the integration of computational design, nanomedicine, and immunometabolic insight. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI)-driven molecule discovery, precision nanodelivery, and systems immunometabolism offers a pipeline for agent development that is faster and more targeted than conventional antibiotic screens. AI and discovery. Machine-learning and deep-learning platforms have already identified novel antimicrobial scaffolds and optimized siderophore-antibiotic conjugates in silico and in vitro, expediting hit discovery and de-risking medicinal chemistry [315,316]. AI can prioritize compounds that selectively impair pathogen metal acquisition or exploit species-specific uptake systems. Nanomedicine and targeted modulation. Nanocarriers allow for precise spatial control in that they can deliver chelators, metal-mimetic agents (e.g., gallium), or zinc/copper payloads to infected tissues or intracellular vacuoles while limiting systemic toxicity [317,318,319,320]. Functionalization with targeting ligands such as antibodies and peptides can improve pathogen-cell specificity. Immunometabolic therapeutics. Host-directed modulation of immune cell metabolism such as altering macrophage metabolism to support nutrient withholding or enhanced antimicrobial effector functions, complements direct antimicrobial strategies and can lower resistance pressure [55,321]. Roadmap. A translational program should: (1) pair mechanistic animal models with multiomics readouts, especially metabolomics and metallomics (2) use AI to triage candidate chemistries that engage pathogen uptake systems, (3) validate targeted nanodelivery in safety models, and (4) design early-phase trials with robust biomarkers, including hepcidin, labile plasma iron, and tissue metallome, to ascertain on-target effects before large efficacy trials [315,317]. This integrated approach promises host-informed, pathogen-targeted therapeutics that exploit nutritional immunity while lowering collateral host injury. |

Authors contributions

Declaration of Interest Statement

References

- Zhang XX, Jin YZ, Lu YH, Huang LL, Wu CX, Lv S, et al. Infectious disease control: from health security strengthening to health systems improvement at global level. Global Health Research and Policy. 2023 Sept 5;8(1):38.

- Salam MdA, Al-Amin MdY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 July 5;11(13):1946.

- Muteeb G, Rehman MT, Shahwan M, Aatif M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Nov 15;16(11):1615.

- Kreimendahl S, Pernas L. Metabolic immunity against microbes. Trends in Cell Biology. 2024 June 1;34(6):496–508.

- Murdoch CC, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: the battle for nutrient metals at the host–pathogen interface. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022 Nov;20(11):657–70.

- Wildeman AS, Culotta VC. Nutritional Immunity and Fungal Pathogens: A New Role for Manganese. Curr Clin Micro Rpt. 2024 June 1;11(2):70–8.

- Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Iron in Infection and Immunity. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013 May 15;13(5):509–19.

- Haley KP, Skaar EP. A battle for iron: host sequestration and Staphylococcus aureus acquisition. Microbes and Infection. 2012 Mar 1;14(3):217–27.

- Kehl-Fie TE, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity beyond iron: a role for manganese and zinc. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010 Apr;14(2):218–24.

- Núñez G, Sakamoto K, Soares MP. Innate Nutritional Immunity. J Immunol. 2018 July 1;201(1):11–8.

- Ganz T, Nemeth E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015 Aug;15(8):500–10.

- Cellier MF, Courville P, Campion C. Nramp1 phagocyte intracellular metal withdrawal defense. Microbes and Infection. 2007 Nov 1;9(14):1662–70.

- Kolliniati O, Ieronymaki E, Vergadi E, Tsatsanis C. Metabolic Regulation of Macrophage Activation. J Innate Immun. 2021 July 9;14(1):51–68.

- Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the Iron-Infection Axis. Science. 2012 Nov 9;338(6108):768–72.

- Malavia D, Crawford A, Wilson D. Chapter Three - Nutritional Immunity and Fungal Pathogenesis: The Struggle for Micronutrients at the Host–Pathogen Interface. In: Poole RK, editor. Advances in Microbial Physiology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 23]. p. 85–103. (Microbiology of Metal Ions; vol. 70). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065291117300061.

- Deriu E, Liu JZ, Pezeshki M, Edwards RA, Ochoa RJ, Contreras H, et al. Probiotic Bacteria Reduce Salmonella Typhimurium Intestinal Colonization by Competing for Iron. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013 July 17;14(1):26–37.

- Hood MI, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012 July 16;10(8). [CrossRef]

- Monteith AJ, Skaar EP. The impact of metal availability on immune function during infection. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021 Nov 1;32(11):916–28.

- Brophy MB, Nolan EM. Manganese and Microbial Pathogenesis: Sequestration by the Mammalian Immune System and Utilization by Microorganisms. ACS Chem Biol. 2015 Mar 20;10(3):641–51.

- Damo SM, Kehl-Fie TE, Sugitani N, Holt ME, Rathi S, Murphy WJ, et al. Molecular basis for manganese sequestration by calprotectin and roles in the innate immune response to invading bacterial pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013 Mar 5;110(10):3841–6.

- Djoko KY, Ong C lynn Y, Walker MJ, McEwan AG. The Role of Copper and Zinc Toxicity in Innate Immune Defense against Bacterial Pathogens*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015 July 31;290(31):18954–61.

- Barwinska-Sendra A, Waldron KJ. Chapter Eight - The Role of Intermetal Competition and Mis-Metalation in Metal Toxicity. In: Poole RK, editor. Advances in Microbial Physiology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2017 [cited 2025 Sept 7]. p. 315–79. (Microbiology of Metal Ions; vol. 70). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065291117300036.

- Abt MC, Pamer EG. Commensal bacteria mediated defenses against pathogens. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2014 Aug 1;29:16–22.

- Horrocks V, King OG, Yip AYG, Marques IM, McDonald JAK. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrient competition and protection against intestinal pathogen colonization. Microbiology (Reading). 2023 Aug 4;169(8):001377.

- Mandel CG, Sanchez SE, Monahan CC, Phuklia W, Omsland A. Metabolism and physiology of pathogenic bacterial obligate intracellular parasites. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024 Mar 22;14:1284701.

- Kelly B, O’Neill LA. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophages and dendritic cells in innate immunity. Cell Res. 2015 July;25(7):771–84.

- Nakashige TG, Zhang B, Krebs C, Nolan EM. Human Calprotectin Is an Iron-Sequestering Host-Defense Protein. Nat Chem Biol. 2015 Oct;11(10):765–71.

- Zackular JP, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Nutritional Immunity: S100 Proteins at the Host-Pathogen Interface. J Biol Chem. 2015 July 31;290(31):18991–8.

- Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004 Dec;432(7019):917–21.

- Guo BX, Wang QQ, Li JH, Gan ZS, Zhang XF, Wang YZ, et al. Lipocalin 2 regulates intestine bacterial survival by interplaying with siderophore in a weaned piglet model of Escherichia coli infection. Oncotarget. 2017 June 16;8(39):65386–96.

- Bachman MA, Miller VL, Weiser JN. Mucosal Lipocalin 2 Has Pro-Inflammatory and Iron-Sequestering Effects in Response to Bacterial Enterobactin. PLoS Pathog. 2009 Oct 16;5(10):e1000622.

- Valdebenito M, Müller SI, Hantke K. Special conditions allow binding of the siderophore salmochelin to siderocalin (NGAL-lipocalin). FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007 Dec 1;277(2):182–7.

- Kehl-Fie TE, Chitayat S, Hood MI, Damo S, Restrepo N, Garcia C, et al. Nutrient Metal Sequestration by Calprotectin Inhibits Bacterial Superoxide Defense, Enhancing Neutrophil Killing of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host & Microbe. 2011 Aug 18;10(2):158–64.

- White C, Lee J, Kambe T, Fritsche K, Petris MJ. A Role for the ATP7A Copper-transporting ATPase in Macrophage Bactericidal Activity. J Biol Chem. 2009 Dec 4;284(49):33949–56.

- Stafford SL, Bokil NJ, Achard MES, Kapetanovic R, Schembri MA, McEwan AG, et al. Metal ions in macrophage antimicrobial pathways: emerging roles for zinc and copper. Biosci Rep. 2013 July 16;33(4):e00049.

- White C, Kambe T, Fulcher YG, Sachdev SW, Bush AI, Fritsche K, et al. Copper transport into the secretory pathway is regulated by oxygen in macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2009 May 1;122(9):1315–21.

- Chen L, Shen Q, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Sun L, Ma X, et al. Homeostasis and metabolism of iron and other metal ions in neurodegenerative diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2025 Feb 3;10(1):31.

- Rosenblum SL. Inflammation, dysregulated iron metabolism, and cardiovascular disease. Front Aging. 2023 Feb 3;4:1124178.

- Pernas L. Cellular metabolism in the defense against microbes. J Cell Sci. 2021 Feb 8;134(5):jcs252023.

- O’Neill LAJ, Kishton RJ, Rathmell J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016 Sept;16(9):553–65.

- Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, Ward DM, et al. Hepcidin Regulates Cellular Iron Efflux by Binding to Ferroportin and Inducing Its Internalization. Science. 2004 Dec 17;306(5704):2090–3.

- Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2007 May 1;117(5):1147–54.

- Thomas AC, Mattila JT. “Of Mice and Men”: Arginine Metabolism in Macrophages. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2014 Oct 7 [cited 2025 Aug 24];5. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00479/full.

- Kelly B, Pearce EL. Amino Assets: How Amino Acids Support Immunity. Cell Metabolism. 2020 Aug 4;32(2):154–75.

- Kornberg MD. The immunologic Warburg effect: Evidence and therapeutic opportunities in autoimmunity. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2020;12(5):e1486.

- Kamel M, Aleya S, Alsubih M, Aleya L. Microbiome Dynamics: A Paradigm Shift in Combatting Infectious Diseases. J Pers Med. 2024 Feb 18;14(2):217.

- Eylert E, Schär J, Mertins S, Stoll R, Bacher A, Goebel W, et al. Carbon metabolism of Listeria monocytogenes growing inside macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 2008 Aug;69(4):1008–17.

- Rohmer L, Hocquet D, Miller SI. Are pathogenic bacteria just looking for food? Metabolism and microbial pathogenesis. Trends in Microbiology. 2011 July 1;19(7):341–8.

- Klaenhammer TR, Kleerebezem M, Kopp MV, Rescigno M. The impact of probiotics and prebiotics on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012 Oct;12(10):728–34.

- Ji J, Jin W, Liu S, Jiao Z, Li X. Probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics in health and disease. MedComm (2020). 2023 Nov 4;4(6):e420.

- Bin BH, Seo J, Kim ST. Function, Structure, and Transport Aspects of ZIP and ZnT Zinc Transporters in Immune Cells. J Immunol Res. 2018 Oct 2;2018:9365747.

- Lichten LA, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters: nutritional and physiologic regulation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29:153–76.

- He F, Ru X, Wen T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 July 6;21(13):4777.

- Sinclair LV, Rolf J, Emslie E, Shi YB, Taylor PM, Cantrell DA. Control of amino-acid transport by antigen receptors coordinates the metabolic reprogramming essential for T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2013 May;14(5):500–8.

- Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase and metabolic control of immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2013 Mar;34(3):137–43.

- Ullah I, Lang M. Key players in the regulation of iron homeostasis at the host-pathogen interface. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 Oct 24 [cited 2025 Sept 13];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1279826/full.

- Mackenzie EL, Iwasaki K, Tsuji Y. Intracellular Iron Transport and Storage: From Molecular Mechanisms to Health Implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008 June;10(6):997–1030.

- Belinskaia DA, Voronina PA, Goncharov NV. Integrative Role of Albumin: Evolutionary, Biochemical and Pathophysiological Aspects. J Evol Biochem Physiol. 2021;57(6):1419–48.

- Besold AN, Culbertson EM, Nam L, Hobbs RP, Boyko A, Maxwell CN, et al. Antimicrobial action of calprotectin that does not involve metal withholding. Metallomics. 2018 Dec 12;10(12):1728–42.

- Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving Inflammation. Cell. 2010 Mar 19;140(6):871–82.

- Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature. 2013 Apr;496(7444):238–42.

- Charlebois E, Pantopoulos K. Nutritional Aspects of Iron in Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2023 Jan;15(11):2441.

- Parrow NL, Fleming RE, Minnick MF. Sequestration and Scavenging of Iron in Infection. Infect Immun. 2013 Oct;81(10):3503–14.

- Schalk IJ. Bacterial siderophores: diversity, uptake pathways and applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025 Jan;23(1):24–40.

- Wiles TJ, Kulesus RR, Mulvey MA. Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2008 Aug 1;85(1):11–9.

- Hantke K, Nicholson G, Rabsch W, Winkelmann G. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003 Apr;100(7):3677–82.

- Smith KD. Iron metabolism at the host pathogen interface: lipocalin 2 and the pathogen-associated iroA gene cluster. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(10):1776–80.

- Nairz M, Schroll A, Sonnweber T, Weiss G. The struggle for iron - a metal at the host-pathogen interface. Cell Microbiol. 2010 Dec;12(12):1691–702.

- Drakesmith H, Prentice A. Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008 July;6(7):541–52.

- Reid DW, O’May C, Kirov SM, Roddam L, Lamont IL, Sanderson K. Iron chelation directed against biofilms as an adjunct to conventional antibiotics. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology [Internet]. 2009 May 1 [cited 2025 Sept 29]; Available from: https://journals.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/ajplung.00058.2009.

- Weinberg GA. Iron chelators as therapeutic agents against Pneumocystis carinii. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy [Internet]. 1994 May [cited 2025 Sept 29]; Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/aac.38.5.997.

- Itoh K, Tsutani H, Mitsuke Y, Iwasaki H. Potential additional effects of iron chelators on antimicrobial- impregnated central venous catheters. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2023 Aug 7 [cited 2025 Aug 3];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1210747/full.

- Raymond KN, Allred BE, Sia AK. Coordination Chemistry of Microbial Iron Transport. Acc Chem Res. 2015 Sept 15;48(9):2496–505.

- Baksh KA, Zamble DB. Allosteric control of metal-responsive transcriptional regulators in bacteria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2020 Feb 7;295(6):1673–84.

- Wessels I, Maywald M, Rink L. Zinc as a Gatekeeper of Immune Function. Nutrients. 2017 Nov 25;9(12):1286.

- Makthal N, Kumaraswami M. Zinc’ing it out: Zinc homeostasis mechanisms and their impact on the pathogenesis of human pathogen group A streptococcus. Metallomics. 2017 Dec 1;9(12):1693–702.

- Liu M, Sun X, Chen B, Dai R, Xi Z, Xu H. Insights into Manganese Superoxide Dismutase and Human Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 14;23(24):15893.

- Salah I, Parkin IP, Allan E. Copper as an antimicrobial agent: recent advances. RSC Adv. 2021 May 19;11(30):18179–86.

- Samanovic MI, Ding C, Thiele DJ, Darwin KH. Copper in Microbial Pathogenesis: Meddling with the Metal. Cell Host & Microbe. 2012 Feb 16;11(2):106–15.

- Rowland JL, Niederweis M. Resistance mechanisms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis against phagosomal copper overload. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2012 May;92(3):202–10.

- Calvo J, Jung H, Meloni G. Copper metallothioneins. IUBMB Life. 2017 Apr;69(4):236–45.

- Arendsen LP, Thakar R, Sultan AH. The Use of Copper as an Antimicrobial Agent in Health Care, Including Obstetrics and Gynecology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019 Aug 14;32(4):e00125-18.

- Lemire JA, Harrison JJ, Turner RJ. Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013 June;11(6):371–84.

- Fiorentini D, Cappadone C, Farruggia G, Prata C. Magnesium: Biochemistry, Nutrition, Detection, and Social Impact of Diseases Linked to Its Deficiency. Nutrients. 2021 Mar 30;13(4):1136.

- Papp-Wallace KM, Maguire ME. Magnesium Transport and Magnesium Homeostasis. EcoSal Plus. 2008 Sept 25;3(1):10.1128/ecosalplus.5.4.4.2.

- Groisman EA. The Pleiotropic Two-Component Regulatory System PhoP-PhoQ. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001 Mar 15;183(6):1835–42.

- Gunn JS, Ernst RK, McCoy AJ, Miller SI. Constitutive Mutations of the Salmonella entericaSerovar Typhimurium Transcriptional Virulence RegulatorphoP. Infection and Immunity. 2000 June;68(6):3758–62.

- Lensmire JM, Hammer ND. Nutrient sulfur acquisition strategies employed by bacterial pathogens. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2019 Feb 1;47:52–8.

- Amon J, Titgemeyer F, Burkovski A. Common patterns - unique features: nitrogen metabolism and regulation in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010 July;34(4):588–605.

- Ryan BE, Mike LA. Arginine at the host-pathogen interface. Infect Immun. 93(8):e00612-24.

- Wang L, Hou Y, Yuan H, Chen H. The role of tryptophan in Chlamydia trachomatis persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Aug 2;12:931653.

- Kim G, Weiss SJ, Levine RL. Methionine oxidation and reduction in proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2014 Feb 1;1840(2):901–5.

- Kies PJ, Hammer ND. A Resourceful Race: Bacterial Scavenging of Host Sulfur Metabolism during Colonization. Infect Immun. 90(5):e00579-21.

- Kharwar S, Bhattacharjee S, Chakraborty S, Mishra AK. Regulation of sulfur metabolism, homeostasis and adaptive responses to sulfur limitation in cyanobacteria. Biologia. 2021 Oct 1;76(10):2811–35.

- Tardy AL, Pouteau E, Marquez D, Yilmaz C, Scholey A. Vitamins and Minerals for Energy, Fatigue and Cognition: A Narrative Review of the Biochemical and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients. 2020 Jan 16;12(1):228.

- Hanna M, Jaqua E, Nguyen V, Clay J. B Vitamins: Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm J. 26(2):89–97.

- Pham VT, Dold S, Rehman A, Bird JK, Steinert RE. Vitamins, the gut microbiome and gastrointestinal health in humans. Nutrition Research. 2021 Nov 1;95:35–53.

- Schröder SK, Gasterich N, Weiskirchen S, Weiskirchen R. Lipocalin 2 receptors: facts, fictions, and myths. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Aug 27];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1229885/full.

- Rieder FJ, Gröschel C, Kastner MT, Kosulin K, Laengle J, Zadnikar R, et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Infection Downregulates Vitamin-D Receptor in Mammalian Cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017 Jan;165(Pt B):356–62.

- Roth JR, Lawrence JG, Rubenfield M, Kieffer-Higgins S, Church GM. Characterization of the cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthetic genes of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993 June;175(11):3303–16.

- Minato Y, Thiede JM, Kordus SL, McKlveen EJ, Turman BJ, Baughn AD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Folate Metabolism and the Mechanistic Basis for para-Aminosalicylic Acid Susceptibility and Resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2015 June 1 [cited 2025 Aug 1]; Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/aac.00647-15.

- Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013 Feb 15;4(2):119–28.

- Perfect JR, Kronstad JW. Cryptococcal nutrient acquisition and pathogenesis: dining on the host. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2025 Feb 10;89(1):e00015-23.

- Passalacqua KD, Charbonneau ME, O’Riordan MXD. Bacterial Metabolism Shapes the Host–Pathogen Interface. Microbiology Spectrum. 2016 May 13;4(3):10.1128/microbiolspec.vmbf-0027–2015.

- Bhagwat A, Haldar T, Kanojiya P, Saroj SD. Bacterial metabolism in the host and its association with virulence. Virulence. 16(1):2459336.

- Eisenreich W, Heesemann J, Rudel T, Goebel W. Metabolic host responses to infection by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol [Internet]. 2013 July 9 [cited 2025 Aug 27];3. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2013.00024/full.

- Tang J, Wang X, Chen S, Chang T, Gu Y, Zhang F, et al. Disruption of glucose homeostasis by bacterial infection orchestrates host innate immunity through NAD+/NADH balance. Cell Reports. 2024 Sept 24;43(9):114648.

- Ling ZN, Jiang YF, Ru JN, Lu JH, Ding B, Wu J. Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Sept 13;8(1):345.

- Prentice AM, Ghattas H, Cox SE. Host-Pathogen Interactions: Can Micronutrients Tip the Balance?123. The Journal of Nutrition. 2007 May 1;137(5):1334–7.

- Perkins-Balding D, Ratliff-Griffin M, Stojiljkovic I. Iron Transport Systems in Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004 Mar;68(1):154–71.

- Cornelissen CN, Sparling PF. Iron piracy: acquisition of transferrin-bound iron by bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 1994 Dec;14(5):843–50.

- Litt DJ, Palmer HM, Borriello SP. Neisseria meningitidis Expressing Transferrin Binding Proteins of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae Can Utilize Porcine Transferrin for Growth. Infect Immun. 2000 Feb;68(2):550–7.

- Andre GO, Converso TR, Politano WR, Ferraz LFC, Ribeiro ML, Leite LCC, et al. Role of Streptococcus pneumoniae Proteins in Evasion of Complement-Mediated Immunity. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2017 Feb 20 [cited 2025 Aug 29];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00224/full.

- Tu AHT, Fulgham RL, McCrory MA, Briles DE, Szalai AJ. Pneumococcal Surface Protein A Inhibits Complement Activation by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infection and Immunity. 1999 Sept;67(9):4720–4.

- Brown JS, Gilliland SM, Holden DW. A Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenicity island encoding an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake and virulence. Molecular Microbiology. 2001;40(3):572–85.

- Tiedemann MT, Muryoi N, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. Iron acquisition by the haem-binding Isd proteins in Staphylococcus aureus: studies of the mechanism using magnetic circular dichroism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008 Nov 19;36(6):1138–43.

- Ghssein G, Ezzeddine Z. A Review of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Metallophores: Pyoverdine, Pyochelin and Pseudopaline. Biology (Basel). 2022 Nov 25;11(12):1711.

- Cornelis P, Tahrioui A, Lesouhaitier O, Bouffartigues E, Feuilloley M, Baysse C, et al. High affinity iron uptake by pyoverdine in Pseudomonas aeruginosa involves multiple regulators besides Fur, PvdS, and FpvI. Biometals. 2023 Apr 1;36(2):255–61.

- Robinson AE, Heffernan JR, Henderson JP. The iron hand of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: the role of transition metal control in virulence. Future Microbiol. 2018 June;13(7):745–56.

- Garcia EC, Brumbaugh AR, Mobley HLT. Redundancy and specificity of Escherichia coli iron acquisition systems during urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2011 Mar;79(3):1225–35.

- Thakur A, Mikkelsen H, Jungersen G. Intracellular Pathogens: Host Immunity and Microbial Persistence Strategies. J Immunol Res. 2019 Apr 14;2019:1356540.

- Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Phagosome in Human Macrophages Is Isolated from the Host Cell Cytoplasm. Infect Immun. 2002 Oct;70(10):5800–7.

- Sheldon JR, Skaar EP. Metals as phagocyte antimicrobial effectors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2019 Oct;60:1–9.

- Zhang L, Kent JE, Whitaker M, Young DC, Herrmann D, Aleshin AE, et al. A periplasmic cinched protein is required for siderophore secretion and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Commun. 2022 Apr 26;13:2255.

- Pandey AK, Sassetti CM. Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008 Mar 18;105(11):4376–80.

- Zhao H, Zhang X, Zhang N, Zhu L, Lian H. The interplay between Salmonella and host: Mechanisms and strategies for bacterial survival. Cell Insight. 2025 Apr 1;4(2):100237.

- Chamnongpol S, Cromie M, Groisman EA. Mg2+ sensing by the Mg2+ sensor PhoQ of Salmonella enterica. J Mol Biol. 2003 Jan 24;325(4):795–807.

- Ikeda JS, Janakiraman A, Kehres DG, Maguire ME, Slauch JM. Transcriptional Regulation of sitABCD of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium by MntR and Fur. J Bacteriol. 2005 Feb;187(3):912–22.

- Ammendola S, Pasquali P, Pistoia C, Petrucci P, Petrarca P, Rotilio G, et al. High-Affinity Zn2+ Uptake System ZnuABC Is Required for Bacterial Zinc Homeostasis in Intracellular Environments and Contributes to the Virulence of Salmonella enterica. Infection and Immunity. 2007 Dec;75(12):5867–76.

- Mordue DG, Håkansson S, Niesman I, David Sibley L. Toxoplasma gondii Resides in a Vacuole That Avoids Fusion with Host Cell Endocytic and Exocytic Vesicular Trafficking Pathways. Experimental Parasitology. 1999 June 1;92(2):87–99.

- Blader IJ, Koshy AA. Toxoplasma gondii Development of Its Replicative Niche: in Its Host Cell and Beyond. Eukaryotic Cell. 2014 July 30;13(8):965–76.

- Fan YM, Zhang QQ, Pan M, Hou ZF, Fu L, Xu X, et al. Toxoplasma gondii sustains survival by regulating cholesterol biosynthesis and uptake via SREBP2 activation. J Lipid Res. 2024 Oct 28;65(12):100684.

- Skariah S, McIntyre MK, Mordue DG. Toxoplasma gondii: determinants of tachyzoite to bradyzoite conversion. Parasitology Research. 2010 June 1;107(2):253.

- Sandoz KM, Beare PA, Cockrell DC, Heinzen RA. Complementation of Arginine Auxotrophy for Genetic Transformation of Coxiella burnetii by Use of a Defined Axenic Medium. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2016 May 15;82(10):3042–51.

- Liu J, Istvan ES, Gluzman IY, Gross J, Goldberg DE. Plasmodium falciparum ensures its amino acid supply with multiple acquisition pathways and redundant proteolytic enzyme systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006 June 6;103(23):8840–5.

- Counihan NA, Modak JK, de Koning-Ward TF. How Malaria Parasites Acquire Nutrients From Their Host. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Mar 25;9:649184.

- Prentice AM, Ghattas H, Doherty C, Cox SE. Iron metabolism and malaria. Food Nutr Bull. 2007 Dec;28(4 Suppl):S524-539.

- Huynh C, Sacks DL, Andrews NW. A Leishmania amazonensis ZIP family iron transporter is essential for parasite replication within macrophage phagolysosomes. J Exp Med. 2006 Sept 25;203(10):2363–75.

- Chandra S, Ruhela D, Deb A, Vishwakarma RA. Glycobiology of the Leishmania parasite and emerging targets for antileishmanial drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2010 July 1;14(7):739–57.

- Almeida RS, Brunke S, Albrecht A, Thewes S, Laue M, Jr JEE, et al. The Hyphal-Associated Adhesin and Invasin Als3 of Candida albicans Mediates Iron Acquisition from Host Ferritin. PLOS Pathogens. 2008 Nov 21;4(11):e1000217.

- Jung WH, Kronstad JW. Iron and fungal pathogenesis: a case study with Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell Microbiol. 2008 Feb;10(2):277–84.

- Hissen AHT, Wan ANC, Warwas ML, Pinto LJ, Moore MM. The Aspergillus fumigatus Siderophore Biosynthetic Gene sidA, Encoding l-Ornithine N5-Oxygenase, Is Required for Virulence. Infection and Immunity. 2005 Sept;73(9):5493–503.

- Deitsch KW, Lukehart SA, Stringer JR. Common strategies for antigenic variation by bacterial, fungal and protozoan pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009 July;7(7):493–503.

- Maizels RM. Parasite immunomodulation and polymorphisms of the immune system. J Biol. 2009;8(7):62.

- Miethke M, Marahiel MA. Siderophore-Based Iron Acquisition and Pathogen Control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007 Sept;71(3):413–51.

- Andersson SGE, Zomorodipour A, Andersson JO, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Alsmark UCM, Podowski RM, et al. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature. 1998 Nov;396(6707):133–40.

- Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, et al. Genome Sequence of an Obligate Intracellular Pathogen of Humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998 Oct 23;282(5389):754–9.

- Taylor SJ, Winter SE. Salmonella finds a way: Metabolic versatility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in diverse host environments. PLOS Pathogens. 2020 June 11;16(6):e1008540.

- Templeton TJ. The varieties of gene amplification, diversification and hypervariability in the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2009 Aug 1;166(2):109–16.

- Dunn MJ, Kinney GM, Washington PM, Berman J, Anderson MZ. Functional diversification accompanies gene family expansion of MED2 homologs in Candida albicans. PLOS Genetics. 2018 Apr 9;14(4):e1007326.

- Martin RE, Henry RI, Abbey JL, Clements JD, Kirk K. The “permeome” of the malaria parasite: an overview of the membrane transport proteins of Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Biology. 2005 Mar 2;6(3):R26.

- Haas H. Fungal siderophore metabolism with a focus on Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat Prod Rep. 2014 Sept 11;31(10):1266–76.

- Goyal A. Horizontal gene transfer drives the evolution of dependencies in bacteria. iScience. 2022 Apr 27;25(5):104312.

- Kramer J, Özkaya Ö, Kümmerli R. Bacterial siderophores in community and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Mar;18(3):152–63.

- Lin H, Fischbach MA, Liu DR, Walsh CT. In Vitro Characterization of Salmochelin and Enterobactin Trilactone Hydrolases IroD, IroE, and Fes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005 Aug 1;127(31):11075–84.

- Price SL, Vadyvaloo V, DeMarco JK, Brady A, Gray PA, Kehl-Fie TE, et al. Yersiniabactin contributes to overcoming zinc restriction during Yersinia pestis infection of mammalian and insect hosts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021 Nov 2;118(44):e2104073118.

- Katumba GL, Tran H, Henderson JP. The Yersinia High-Pathogenicity Island Encodes a Siderophore-Dependent Copper Response System in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. mBio. 13(1):e02391-21.

- Leon-Sicairos N, Reyes-Cortes R, Guadrón-Llanos AM, Madueña-Molina J, Leon-Sicairos C, Canizalez-Román A. Strategies of Intracellular Pathogens for Obtaining Iron from the Environment. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015(1):476534.

- Gu Y, Liu Y, Mao W, Peng Y, Han X, Jin H, et al. Functional versatility of Zur in metal homeostasis, motility, biofilm formation, and stress resistance in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2024 May 2;12(5):e0375623.

- Cai R, Gao F, Pan J, Hao X, Yu Z, Qu Y, et al. The transcriptional regulator Zur regulates the expression of ZnuABC and T6SS4 in response to stresses in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Microbiological Research. 2021 Aug 1;249:126787.

- Bosma EF, Rau MH, van Gijtenbeek LA, Siedler S. Regulation and distinct physiological roles of manganese in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2021 Nov 1;45(6):fuab028.

- Waters LS, Sandoval M, Storz G. The Escherichia coli MntR Miniregulon Includes Genes Encoding a Small Protein and an Efflux Pump Required for Manganese Homeostasis ▿. J Bacteriol. 2011 Nov;193(21):5887–97.

- Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Metal ion acquisition in Staphylococcus aureus: overcoming nutritional immunity. Semin Immunopathol. 2012 Mar 1;34(2):215–35.

- Kehl-Fie TE, Zhang Y, Moore JL, Farrand AJ, Hood MI, Rathi S, et al. MntABC and MntH Contribute to Systemic Staphylococcus aureus Infection by Competing with Calprotectin for Nutrient Manganese. Infection and Immunity. 2013 Aug 13;81(9):3395–405.

- Zaharik ML, Cullen VL, Fung AM, Libby SJ, Kujat Choy SL, Coburn B, et al. The Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Divalent Cation Transport Systems MntH and SitABCD Are Essential for Virulence in an Nramp1G169 Murine Typhoid Model. Infection and Immunity. 2004 Sept;72(9):5522–5.

- Campoy S, Jara M, Busquets N, Pérez de Rozas AM, Badiola I, Barbé J. Role of the High-Affinity Zinc Uptake znuABC System in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Virulence. Infection and Immunity. 2002 Aug;70(8):4721–5.

- Nair A, Sarma SJ. The impact of carbon and nitrogen catabolite repression in microorganisms. Microbiological Research. 2021 Oct 1;251:126831.

- Joseph B, Mertins S, Stoll R, Schär J, Umesha KR, Luo Q, et al. Glycerol Metabolism and PrfA Activity in Listeria monocytogenes. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008 Aug;190(15):5412–30.

- Freeman MJ, Eral NJ, Sauer JD. Listeria monocytogenes requires phosphotransferase systems to facilitate intracellular growth and virulence. PLOS Pathogens. 2025 Apr 15;21(4):e1012492.

- Zhang YJ, Rubin EJ. Feast or famine: the host–pathogen battle over amino acids. Cell Microbiol. 2013 July;15(7):1079–87.

- Ren W, Rajendran R, Zhao Y, Tan B, Wu G, Bazer FW, et al. Amino Acids As Mediators of Metabolic Cross Talk between Host and Pathogen. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2018 Feb 27 [cited 2025 Aug 30];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00319/full.

- Borah K, Beyß M, Theorell A, Wu H, Basu P, Mendum TA, et al. Intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis Exploits Multiple Host Nitrogen Sources during Growth in Human Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2019 Dec 10;29(11):3580-3591.e4.

- Liu Y, Zhang Q, Hu M, Yu K, Fu J, Zhou F, et al. Proteomic Analyses of Intracellular Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Reveal Extensive Bacterial Adaptations to Infected Host Epithelial Cells. Infection and Immunity [Internet]. 2015 May 4 [cited 2025 Sept 16]; Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/iai.02882-14.

- Coppens I, Dunn JD, Romano JD, Pypaert M, Zhang H, Boothroyd JC, et al. Toxoplasma gondii Sequesters Lysosomes from Mammalian Hosts in the Vacuolar Space. Cell. 2006 Apr 21;125(2):261–74.

- Wang T, Wang C, Li C, Song L. The intricate dance: host autophagy and Coxiella burnetii infection. Front Microbiol. 2023 Sept 22;14:1281303.

- McConville MJ, Handman E. The molecular basis of Leishmania pathogenesis. International Journal for Parasitology. 2007 Aug 1;37(10):1047–51.

- Counihan NA, Chisholm SA, Bullen HE, Srivastava A, Sanders PR, Jonsdottir TK, et al. Plasmodium falciparum parasites deploy RhopH2 into the host erythrocyte to obtain nutrients, grow and replicate. Soldati-Favre D, editor. eLife. 2017 Mar 2;6:e23217.

- Martin RE. The transportome of the malaria parasite. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2020 Apr;95(2):305–32.

- Sorci G, Cornet S, Faivre B. Immune Evasion, Immunopathology and the Regulation of the Immune System. Pathogens. 2013 Mar;2(1):71–91.

- Stanley SA, Raghavan S, Hwang WW, Cox JS. Acute infection and macrophage subversion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis require a specialized secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Oct 28;100(22):13001–6.

- Lažetić V, Troemel ER. Conservation lost: host-pathogen battles drive diversification and expansion of gene families. FEBS J. 2021 Sept;288(18):5289–99.

- Moon YH, Tanabe T, Funahashi T, Shiuchi K ichi, Nakao H, Yamamoto S. Identification and characterization of two contiguous operons required for aerobactin transport and biosynthesis in Vibrio mimicus. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48(5):389–98.

- Stork M, Di Lorenzo M, Welch TJ, Crosa JH. Transcription termination within the iron transport-biosynthesis operon of Vibrio anguillarum requires an antisense RNA. J Bacteriol. 2007 May;189(9):3479–88.

- Lynch D, O’Brien J, Welch T, Clarke P, Cuív PO, Crosa JH, et al. Genetic organization of the region encoding regulation, biosynthesis, and transport of rhizobactin 1021, a siderophore produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2001 Apr;183(8):2576–85.

- Stintzi A, Johnson Z, Stonehouse M, Ochsner U, Meyer JM, Vasil ML, et al. The pvc Gene Cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Role in Synthesis of the Pyoverdine Chromophore and Regulation by PtxR and PvdS. J Bacteriol. 1999 July;181(13):4118–24.

- Patzer SI, Hantke K. The ZnuABC high-affinity zinc uptake system and its regulator Zur in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998 June;28(6):1199–210.

- Kondrashov FA. Gene duplication as a mechanism of genomic adaptation to a changing environment. Proc Biol Sci. 2012 Dec 22;279(1749):5048–57.

- Schmidt H, Hensel M. Pathogenicity Islands in Bacterial Pathogenesis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004 Jan;17(1):14–56.

- Carniel E. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island: an iron-uptake island. Microbes and Infection. 2001 June 1;3(7):561–9.

- Zomorodipour A, Andersson SGE. Obligate intracellular parasites: Rickettsia prowazekii and Chlamydia trachomatis. FEBS Letters. 1999 June 4;452(1):11–5.

- Ghigo E, Colombo MI, Heinzen RA. The Coxiella burnetii Parasitophorous Vacuole. In: Toman R, Heinzen RA, Samuel JE, Mege JL, editors. Coxiella burnetii: Recent Advances and New Perspectives in Research of the Q Fever Bacterium [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. p. 141–69. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4315-1_8. [CrossRef]

- Puri S, Kumar R, Rojas IG, Salvatori O, Edgerton M. Iron Chelator Deferasirox Reduces Candida albicans Invasion of Oral Epithelial Cells and Infection Levels in Murine Oropharyngeal Candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 Apr;63(4):e02152-18.

- Ni T, Chi X, Wu H, Xie F, Bao J, Wang J, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of novel deferasirox derivatives with high antifungal potency in vitro and in vivo. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024 Jan 15;264:116026.

- Feizi S, Awad M, Ramezanpour M, Cooksley C, Murphy W, Prestidge CA, et al. Promoting the Efficacy of Deferiprone-Gallium-Protoporphyrin (IX) against Mycobacterium abscessus Intracellular Infection with Lipid Liquid Crystalline Nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024 Dec 25;16(51):70274–83.

- Feizi S, Awad M, Nepal R, Cooksley CM, Psaltis AJ, Wormald PJ, et al. Deferiprone-gallium-protoporphyrin (IX): A promising treatment modality against Mycobacterium abscessus. Tuberculosis. 2023 Sept 1;142:102390.

- Tarnow-Mordi WO, Abdel-Latif ME, Martin A, Pammi M, Robledo K, Manzoni P, et al. The effect of lactoferrin supplementation on death or major morbidity in very low birthweight infants (LIFT): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020 June 1;4(6):444–54.

- Pammi M, Suresh G. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 June 28;2017(6):CD007137.

- Kadiyala U, Turali-Emre ES, Bahng JH, Kotov NA, VanEpps JS. Unexpected insights into antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Nanoscale. 2018 Mar 8;10(10):4927–39.

- Caron AJ, Ali IJ, Delgado MJ, Johnson D, Reeks JM, Strzhemechny YM, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles mediate bacterial toxicity in Mueller-Hinton Broth via Zn2+. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2024 Apr 22 [cited 2025 Sept 11];15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1394078/full.

- Mendes CR, Dilarri G, Forsan CF, Sapata V de MR, Lopes PRM, de Moraes PB, et al. Antibacterial action and target mechanisms of zinc oxide nanoparticles against bacterial pathogens. Sci Rep. 2022 Feb 16;12(1):2658.

- O’Brien H, Davoodian T, Johnson MDL. The promise of copper ionophores as antimicrobials. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2023 Oct 1;75:102355.

- Dalecki AG, Haeili M, Shah S, Speer A, Niederweis M, Kutsch O, et al. Disulfiram and Copper Ions Kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Synergistic Manner. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Aug;59(8):4835–44.

- Ngwane AH, Petersen RD, Baker B, Wiid I, Wong HN, Haynes RK. The evaluation of the anti-cancer drug elesclomol that forms a redox-active copper chelate as a potential anti-tubercular drug. IUBMB Life. 2019 May;71(5):532–8.

- Goss CH, Kaneko Y, Khuu L, Anderson GD, Ravishankar S, Aitken ML, et al. Gallium disrupts bacterial iron metabolism and has therapeutic effects in mice and humans with lung infections. Science Translational Medicine. 2018 Sept 26;10(460):eaat7520.

- Chan YR, Liu JS, Pociask DA, Zheng M, Mietzner TA, Berger T, et al. Lipocalin 2 Is Required for Pulmonary Host Defense against Klebsiella Infection. J Immunol. 2009 Apr 15;182(8):4947–56.

- Wang Q, Li S, Tang X, Liang L, Wang F, Du H. Lipocalin 2 Protects Against Escherichia coli Infection by Modulating Neutrophil and Macrophage Function. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2019 Nov 8 [cited 2025 Sept 11];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02594/full.

- Lin YM, Ghosh M, Miller PA, Möllmann U, Miller MJ. Synthetic sideromycins (skepticism and optimism): selective generation of either broad or narrow spectrum Gram-negative antibiotics. Biometals. 2019 June;32(3):425–51.

- Page MGP, Dantier C, Desarbre E. In vitro properties of BAL30072, a novel siderophore sulfactam with activity against multiresistant gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 June;54(6):2291–302.

- Straubinger M, Blenk H, Naber KG, Wagenlehner FME. Urinary Concentrations and Antibacterial Activity of BAL30072, a Novel Siderophore Monosulfactam, against Uropathogens after Intravenous Administration in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2016 May 23;60(6):3309–15.

- Selvaraj P, Harishankar M, Afsal K. Vitamin D: Immuno-modulation and tuberculosis treatment. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015 May;93(5):377–84.

- Coussens AK, Wilkinson RJ, Hanifa Y, Nikolayevskyy V, Elkington PT, Islam K, et al. Vitamin D accelerates resolution of inflammatory responses during tuberculosis treatment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012 Sept 18;109(38):15449–54.

- Liu Q, Yang Z, Miao Y, Liu X, Peng J, Wei H. Effects of methionine restriction and methionine hydroxy analogs on intestinal inflammation and physical barrier function in mice. Journal of Future Foods. 2025 Jan 1;5(1):68–78.

- Schnadower D, Tarr PI, Casper TC, Gorelick MH, Dean JM, O’Connell KJ, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG versus Placebo for Acute Gastroenteritis in Children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018 Nov 22;379(21):2002–14.

- PiLeJe. Effect and Tolerability of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG LA801 for the Preventive Nutritional Care of Nosocomial Diarrhea in Children [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov; 2021 Apr [cited 2025 Sept 12]. Report No.: NCT04628819. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04628819.

- Vazquez-Gutierrez P, de Wouters T, Werder J, Chassard C, Lacroix C. High Iron-Sequestrating Bifidobacteria Inhibit Enteropathogen Growth and Adhesion to Intestinal Epithelial Cells In vitro. Front Microbiol. 2016 Sept 22;7:1480.

- Sonnenborn U, Schulze J. The non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 – features of a versatile probiotic. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 2009 Jan 1;21(3–4):122–58.

- Helmy YA, Closs G, Jung K, Kathayat D, Vlasova A, Rajashekara G. Effect of Probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917 Supplementation on the Growth Performance, Immune Responses, Intestinal Morphology, and Gut Microbes of Campylobacter jejuni Infected Chickens. Infection and Immunity. 2022 Sept 22;90(10):e00337-22.

- Vaughn BP, Fischer M, Kelly CR, Allegretti JR, Graiziger C, Thomas J, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Colonic and Capsule Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2023 May 1;21(5):1330-1337.e2.

- Tariq R, Pardi DS, Khanna S. Resolution rates in clinical trials for microbiota restoration for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023 May 30;16:17562848231174293.

- Wilcox MH, McGovern BH, Hecht GA. The Efficacy and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Recurrent Clostridiumdifficile Infection: Current Understanding and Gap Analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 May 1 [cited 2025 Sept 12];7(5). Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa114. [CrossRef]

- Kelly CR, Yen EF, Grinspan AM, Kahn SA, Atreja A, Lewis JD, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Is Highly Effective in Real-World Practice: Initial Results From the FMT National Registry. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan;160(1):183-192.e3.

- Shin J, Lee JH, Park SH, Cha B, Kwon KS, Kim H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Clearance of Multidrug-Resistant Organisms under Multiple Comorbidities: A Prospective Comparative Trial. Biomedicines. 2022 Sept 26;10(10):2404.

- Woodworth MH, Babiker A, Prakash-Asrani R, Mehta CC, Steed DB, Ashley A, et al. Microbiota Transplantation Among Patients Receiving Long-Term Care: The Sentinel REACT Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2025 July 1;8(7):e2522740–e2522740.

- Macareño-Castro J, Solano-Salazar A, Dong LT, Mohiuddin M, Espinoza JL. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: A systematic review. Journal of Infection. 2022 June 1;84(6):749–59.

- Singh R, de Groot PF, Geerlings SE, Hodiamont CJ, Belzer C, Berge IJM ten, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation against intestinal colonization by extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae: a proof of principle study. BMC Research Notes. 2018 Mar 22;11(1):190.

- Woodworth MH, Hayden MK, Young VB, Kwon JH. The Role of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Reducing Intestinal Colonization With Antibiotic-Resistant Organisms: The Current Landscape and Future Directions. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 July 1 [cited 2025 Sept 12];6(7). Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz288. [CrossRef]

- Crum-Cianflone NF, Sullivan E, Ballon-Landa G. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Successful Resolution of Multidrug-Resistant-Organism Colonization. Journal of Clinical Microbiology [Internet]. 2015 Apr 15 [cited 2025 Sept 12]; Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jcm.00820-15.

- Keskey R, Cone JT, DeFazio JR, Alverdy JC. The use of fecal microbiota transplant in sepsis. Translational Research. 2020 Dec 1;226:12–25.

- Kim SM, DeFazio JR, Hyoju SK, Sangani K, Keskey R, Krezalek MA, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant rescues mice from human pathogen mediated sepsis by restoring systemic immunity. Nat Commun. 2020 May 11;11(1):2354.

- Barua N, Buragohain AK. Therapeutic Potential of Curcumin as an Antimycobacterial Agent. Biomolecules. 2021 Sept;11(9):1278.

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Dwivedi VP. Advances in adjunct therapy against tuberculosis: Deciphering the emerging role of phytochemicals. MedComm (2020). 2021 Aug 5;2(4):494–513.

- Nakamura M, Urakawa D, He Z, Akagi I, Hou DX, Sakao K. Apoptosis Induction in HepG2 and HCT116 Cells by a Novel Quercetin-Zinc (II) Complex: Enhanced Absorption of Quercetin and Zinc (II). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023 Jan;24(24):17457.

- Jeon J, Kim JH, Lee CK, Oh CH, Song HJ. The Antimicrobial Activity of (-)-Epigallocatehin-3-Gallate and Green Tea Extracts against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Isolated from Skin Wounds. Ann Dermatol. 2014 Oct;26(5):564–9.

- DeDiego ML, Portilla Y, Daviu N, López-García D, Villamayor L, Mulens-Arias V, et al. Iron oxide and iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles impair SARS-CoV-2 infection of cultured cells. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2022 July 30;20(1):352.

- Lu Z, Yu D, Nie F, Wang Y, Chong Y. Iron Nanoparticles Open Up New Directions for Promoting Healing in Chronic Wounds in the Context of Bacterial Infection. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Sept 15;15(9):2327.

- Ikhazuagbe IH, Ofoka EA, Odofin OL, Erumiseli O, Edoka OE, Ezennubia KP, et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanistic insights of gallium-based nanoparticles: an emerging frontier in metal-based antimicrobials. RSC Adv. 2025 Aug 29;15(38):31122–53.

- Ramesh G, Kaviyil JE, Paul W, Sasi R, Joseph R. Gallium–Curcumin Nanoparticle Conjugates as an Antibacterial Agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Synthesis and Characterization. ACS Omega [Internet]. 2022 Feb 17 [cited 2025 Sept 12]; Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsomega.1c06398.

- Paladini F, Pollini M. Antimicrobial Silver Nanoparticles for Wound Healing Application: Progress and Future Trends. Materials. 2019 Jan;12(16):2540.

- Holubnycha V, Husak Y, Korniienko V, Bolshanina S, Tveresovska O, Myronov P, et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Two Different Types of Silver Nanoparticles against Wide Range of Pathogenic Bacteria. Nanomaterials. 2024 Jan;14(2):137.

- Baveloni FG, Meneguin AB, Sábio RM, Camargo BAF de, Trevisan DPV, Duarte JL, et al. Antimicrobial effect of silver nanoparticles as a potential healing treatment for wounds contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus in wistar rats. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2025 Jan 1;103:106445.

- Khalifa HO, Oreiby A, Mohammed T, Abdelhamid MAA, Sholkamy EN, Hashem H, et al. Silver nanoparticles as next-generation antimicrobial agents: mechanisms, challenges, and innovations against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol [Internet]. 2025 Aug 14 [cited 2025 Sept 12];15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1599113/full.

- Bergeron RJ, Wiegand J, McManis JS, Bharti N. Desferrithiocin: A Search for Clinically Effective Iron Chelators. J Med Chem. 2014 Nov 26;57(22):9259–91.

- Gaynor RB, McIntyre BN, Lindsey SL, Clavo KA, Shy WE, Mees DE, et al. Steric Effects on the Chelation of Mn2+ and Zn2+ by Hexadentate Polyimidazole Ligands: Modeling Metal Binding by Calprotectin Site 2. Chemistry. 2023 July 3;29(37):e202300447.

- Horonchik L, Wessling-Resnick M. The Small-Molecule Iron Transport Inhibitor Ferristatin/NSC306711 Promotes Degradation of the Transferrin Receptor. Chemistry & Biology. 2008 July 21;15(7):647–53.

- Juttukonda LJ, Beavers WN, Unsihuay D, Kim K, Pishchany G, Horning KJ, et al. A Small-Molecule Modulator of Metal Homeostasis in Gram-Positive Pathogens. mBio. 2020 Oct 27;11(5):10.1128/mbio.02555-20.

- Ito A, Nishikawa T, Matsumoto S, Yoshizawa H, Sato T, Nakamura R, et al. Siderophore Cephalosporin Cefiderocol Utilizes Ferric Iron Transporter Systems for Antibacterial Activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 Nov 21;60(12):7396–401.

- Chan DCK, Guo I, Burrows LL. Forging New Antibiotic Combinations under Iron-Limiting Conditions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Feb 21;64(3):e01909-19.

- Li X qin, Zhang W xian. Sequestration of Metal Cations with Zerovalent Iron NanoparticlesA Study with High Resolution X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HR-XPS). J Phys Chem C. 2007 May 1;111(19):6939–46.

- Khatun S, Putta CL, Hak A, Rengan AK. Immunomodulatory nanosystems: An emerging strategy to combat viral infections. Biomater Biosyst. 2023 Jan 30;9:100073.

- Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021 Feb;20(2):101–24.

- Clark MA, Goheen MM, Cerami C. Influence of host iron status on Plasmodium falciparum infection. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2014 May 6 [cited 2025 Aug 31];5. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2014.00084/full.

- Traore O, Carnevale P, Kaptue-Noche L, M’Bede J, Desfontaine M, Elion J, et al. Preliminary report on the use of desferrioxamine in the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Hematol. 1991 July;37(3):206–8.

- Gordeuk VR, Biemba G, Thuma PE. Clinical Studies of Iron-Chelating Treatment in Malaria. In: Abraham NG, Asano S, Brittinger G, Maestroni GJM, Shadduck RK, editors. Molecular Biology of Hematopoiesis 5 [Internet]. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1996 [cited 2025 Aug 31]. p. 685–91. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Smith HJ, Meremikwu MM. Iron-chelating agents for treating malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Apr 22;2003(2):CD001474.

- Theriault ME, Pisu D, Wilburn KM, Lê-Bury G, MacNamara CW, Michael Petrassi H, et al. Iron limitation in M. tuberculosis has broad impact on central carbon metabolism. Commun Biol. 2022 July 9;5(1):685.

- Parihar SP, Guler R, Khutlang R, Lang DM, Hurdayal R, Mhlanga MM, et al. Statin therapy reduces the mycobacterium tuberculosis burden in human macrophages and in mice by enhancing autophagy and phagosome maturation. J Infect Dis. 2014 Mar 1;209(5):754–63.

- Jin X, Zhang M, Lu J, Duan X, Chen J, Liu Y, et al. Hinokitiol chelates intracellular iron to retard fungal growth by disturbing mitochondrial respiration. Journal of Advanced Research. 2021 Dec 1;34:65–77.

- Garnacho-Montero J, Barrero-García I, León-Moya C. Fungal infections in immunocompromised critically ill patients. Journal of Intensive Medicine. 2024 July 1;4(3):299–306.

- Ali Zaidi SS, Fatima F, Ali Zaidi SA, Zhou D, Deng W, Liu S. Engineering siRNA therapeutics: challenges and strategies. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2023 Oct 18;21(1):381.

- Munteanu C, Schwartz B. The relationship between nutrition and the immune system. Front Nutr. 2022 Dec 8;9:1082500.

- Sejersen K, Eriksson MB, Larsson AO. Calprotectin as a Biomarker for Infectious Diseases: A Comparative Review with Conventional Inflammatory Markers. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 July 4;26(13):6476.

- Jukic A, Bakiri L, Wagner EF, Tilg H, Adolph TE. Calprotectin: from biomarker to biological function. Gut. 2021 Oct;70(10):1978–88.

- Bjarnason, I. The Use of Fecal Calprotectin in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017 Jan;13(1):53–6.

- Xu MJ, Feng D, Wu H, Wang H, Chan Y, Kolls J, et al. The liver is the major source of elevated serum lipocalin-2 levels after bacterial infection or partial hepatectomy: a critical role for IL-6/STAT3. Hepatology. 2015 Feb;61(2):692–702.

- Stuart T, Satija R. Integrative single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Genet. 2019 May;20(5):257–72.

- Ladomersky E, Petris MJ. Copper tolerance and virulence in bacteria. Metallomics. 2015 June 1;7(6):957–64.

- Karlsson EA, Beck MA, MacIver NJ. Editorial: Nutritional Aspects of Immunity and Immunometabolism in Health and Disease. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2020 Oct 7 [cited 2025 Sept 4];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.595115/full.

- Su Y, Chen D, Yuan D, Lausted C, Choi J, Dai CL, et al. Multi-Omics Resolves a Sharp Disease-State Shift between Mild and Moderate COVID-19. Cell. 2020 Dec 10;183(6):1479-1495.e20.

- Preza GC, Ruchala P, Pinon R, Ramos E, Qiao B, Peralta MA, et al. Minihepcidins are rationally designed small peptides that mimic hepcidin activity in mice and may be useful for the treatment of iron overload. J Clin Invest. 2011 Dec 1;121(12):4880–8.

- Casu C, Nemeth E, Rivella S. Hepcidin agonists as therapeutic tools. Blood. 2018 Apr 19;131(16):1790–4.

- Katsarou A, Pantopoulos K. Hepcidin Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2018 Nov 21;11(4):127.

- Nairz M, Haschka D, Demetz E, Weiss G. Iron at the interface of immunity and infection. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2014 July 16 [cited 2025 Sept 4];5. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2014.00152/full.

- Gallant CJ, Malik S, Jabado N, Cellier M, Simkin L, Finlay BB, et al. Reduced in vitro functional activity of human NRAMP1 (SLC11A1) allele that predisposes to increased risk of pediatric tuberculosis disease. Genes & Immunity. 2007 Dec;8(8):691–8.

- Schaible UE, Kaufmann SHE. Malnutrition and Infection: Complex Mechanisms and Global Impacts. PLOS Medicine. 2007 May 1;4(5):e115.

- Hambidge M. Human zinc deficiency. J Nutr. 2000 May;130(5S Suppl):1344S-9S.

- Trivellone V, Hoberg EP, Boeger WA, Brooks DR. Food security and emerging infectious disease: risk assessment and risk management. Royal Society Open Science. 2022 Feb 16;9(2):211687.

- Tong MX, Hansen A, Hanson-Easey S, Cameron S, Xiang J, Liu Q, et al. Infectious Diseases, Urbanization and Climate Change: Challenges in Future China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015 Sept;12(9):11025–36.

- Brestoff JR, Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nature Immunology. 2013 July;14(7):676–84.

- Kortman GAM, Raffatellu M, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H. Nutritional iron turned inside out: intestinal stress from a gut microbial perspective. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014 Nov 1;38(6):1202–34.

- Ellermann M, Arthur JC. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition and modulation of host-bacterial interactions. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017 Apr;105:68–78.

- Fusco W, Lorenzo MB, Cintoni M, Porcari S, Rinninella E, Kaitsas F, et al. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2023 May 6;15(9):2211.

- Sankarganesh P, Bhunia A, Ganesh Kumar A, Babu AS, Gopukumar ST, Lokesh E. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in gut health: Implications for drug metabolism and therapeutics. Medicine in Microecology. 2025 Sept 1;25:100139.

- Trompette A, Pernot J, Perdijk O, Alqahtani RAA, Domingo JS, Camacho-Muñoz D, et al. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids modulate skin barrier integrity by promoting keratinocyte metabolism and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 2022 May;15(5):908–26.

- Koh A, Vadder FD, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell. 2016 June 2;165(6):1332–45.

- Shen Y, Fan N, Ma S, Cheng X, Yang X, Wang G. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm (2020). 2025 Apr 18;6(5):e70168.

- Kim CH. Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023 Apr;20(4):341–50.

- Sousa Gerós A, Simmons A, Drakesmith H, Aulicino A, Frost JN. The battle for iron in enteric infections. Immunology. 2020 Nov;161(3):186–99.

- Lim HJ, Shin HS. Antimicrobial and Immunomodulatory Effects of Bifidobacterium Strains: A Review. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020 Dec 28;30(12):1793–800.

- Vlasova AN, Kandasamy S, Chattha KS, Rajashekara G, Saif LJ. Comparison of probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria effects, immune responses and rotavirus vaccines and infection in different host species. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2016 Apr;172:72–84.

- Toledo A, Benach JL. Hijacking and Use of Host Lipids by Intracellular Pathogens. Microbiology Spectrum [Internet]. 2015 Dec 21 [cited 2025 Sept 16]; Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/microbiolspec.vmbf-0001-2014.

- Russell DG, Huang L, VanderVen BC. Immunometabolism at the interface between macrophages and pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019 May;19(5):291–304.

- Bosch M, Sánchez-Álvarez M, Fajardo A, Kapetanovic R, Steiner B, Dutra F, et al. Mammalian lipid droplets are innate immune hubs integrating cell metabolism and host defense. Science [Internet]. 2020 Oct 16 [cited 2025 Sept 16]; Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aay8085.

- Allen PE, Martinez JJ. Modulation of Host Lipid Pathways by Pathogenic Intracellular Bacteria. Pathogens. 2020 Aug;9(8):614.

- Monson EA, Trenerry AM, Laws JL, Mackenzie JM, Helbig KJ. Lipid droplets and lipid mediators in viral infection and immunity. FEMS Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2021 Aug 17 [cited 2025 Sept 16];45(4). Available from. [CrossRef]

- Nazarova EV, Montague CR, La T, Wilburn KM, Sukumar N, Lee W, et al. Rv3723/LucA coordinates fatty acid and cholesterol uptake in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Kana BD, editor. eLife. 2017 June 27;6:e26969.

- Qin C, Xie T, Yeh WW, Savas AC, Feng P. Metabolic Enzymes in Viral Infection and Host Innate Immunity. Viruses. 2024 Jan;16(1):35.

- Drakesmith H, Prentice A. Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008 July;6(7):541–52.

- Wessling-Resnick M. Crossing the Iron Gate: Why and How Transferrin Receptors Mediate Viral Entry. Annu Rev Nutr. 2018 Aug 21;38:431–58.

- Girelli D, Marchi G, Busti F, Vianello A. Iron metabolism in infections: Focus on COVID-19. Semin Hematol. 2021 July;58(3):182–7.

- Read SA, Obeid S, Ahlenstiel C, Ahlenstiel G. The Role of Zinc in Antiviral Immunity. Advances in Nutrition. 2019 July 1;10(4):696–710.

- Velthuis AJW te, Worm SHE van den, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, Hemert MJ van. Zn2+ Inhibits Coronavirus and Arterivirus RNA Polymerase Activity In Vitro and Zinc Ionophores Block the Replication of These Viruses in Cell Culture. PLOS Pathogens. 2010 Nov 4;6(11):e1001176.

- Warnes SL, Keevil CW. Inactivation of Norovirus on Dry Copper Alloy Surfaces. PLOS ONE. 2013 Sept 9;8(9):e75017.

- Wang C, Guan Y, Lv M, Zhang R, Guo Z, Wei X, et al. Manganese Increases the Sensitivity of the cGAS-STING Pathway for Double-Stranded DNA and Is Required for the Host Defense against DNA Viruses. Immunity. 2018 Apr 17;48(4):675-687.e7.

- Nakano R, Nakano A, Sasahara T, Suzuki Y, Nojima Y, Yano H. Antiviral effects of copper and copper alloy and the underlying mechanisms in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances. 2025 Feb 1;17:100589.

- Purniawan A, Lusida MI, Pujiyanto RW, Nastri AM, Permanasari AA, Harsono AAH, et al. Synthesis and assessment of copper-based nanoparticles as a surface coating agent for antiviral properties against SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep. 2022 Mar 22;12(1):4835.

- Wessels I, Rolles B, Rink L. The Potential Impact of Zinc Supplementation on COVID-19 Pathogenesis. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2020 July 10 [cited 2025 Sept 17];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01712/full.

- Vallboehmer F, Schoofs H, Rink L, Jakobs J. Zinc supplementation among zinc-deficient vegetarians and vegans restores antiviral interferon-α response by upregulating interferon regulatory factor 3. Clinical Nutrition. 2025 Aug 1;51:161–73.

- Dalamaga M, Karampela I, Mantzoros CS. Commentary: Could iron chelators prove to be useful as an adjunct to COVID-19 Treatment Regimens? Metabolism. 2020 July;108:154260.

- Nemeth E, Ganz T. Hepcidin and Iron in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Med. 2023 Jan 27;74:261–77.

- Ganz T. Iron and infection. Int J Hematol. 2018 Jan 1;107(1):7–15.

- Das S, Saqib M, Meng RC, Chittur SV, Guan Z, Wan F, et al. Hemochromatosis drives acute lethal intestinal responses to hyperyersiniabactin-producing Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022 Jan 11;119(2):e2110166119.

- Kramer J, Özkaya Ö, Kümmerli R. Bacterial siderophores in community and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Mar;18(3):152–63.

- Kontoghiorghe CN, Kontoghiorghes GJ. New developments and controversies in iron metabolism and iron chelation therapy. World J Methodol. 2016 Mar 26;6(1):1–19.

- Kontoghiorghe CN, Kontoghiorghes GJ. Efficacy and safety of iron-chelation therapy with deferoxamine, deferiprone, and deferasirox for the treatment of iron-loaded patients with non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia syndromes. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016 Jan 29;10:465–81.

- Vamathevan J, Clark D, Czodrowski P, Dunham I, Ferran E, Lee G, et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019 June;18(6):463–77.

- Stokes JM, Yang K, Swanson K, Jin W, Cubillos-Ruiz A, Donghia NM, et al. A Deep Learning Approach to Antibiotic Discovery. Cell. 2020 Feb 20;180(4):688-702.e13.

- Ikoba U, Peng H, Li H, Miller C, Yu C, Wang Q. Nanocarriers in therapy of infectious and inflammatory diseases. Nanoscale. 2015 Feb 26;7(10):4291–305.

- Salouti M, Ahangari A, Salouti M, Ahangari A. Nanoparticle based Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Infectious Diseases. In: Application of Nanotechnology in Drug Delivery [Internet]. IntechOpen; 2014 [cited 2025 Sept 14]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/47150.

- Armstead AL, Li B. Nanomedicine as an emerging approach against intracellular pathogens. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:3281–93.

- Hosseini SM, Taheri M, Nouri F, Farmani A, Moez NM, Arabestani MR. Nano drug delivery in intracellular bacterial infection treatments. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022 Feb 1;146:112609.

- Russell DG, Huang L, VanderVen BC. Immunometabolism at the interface between macrophages and pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019 May;19(5):291–304.

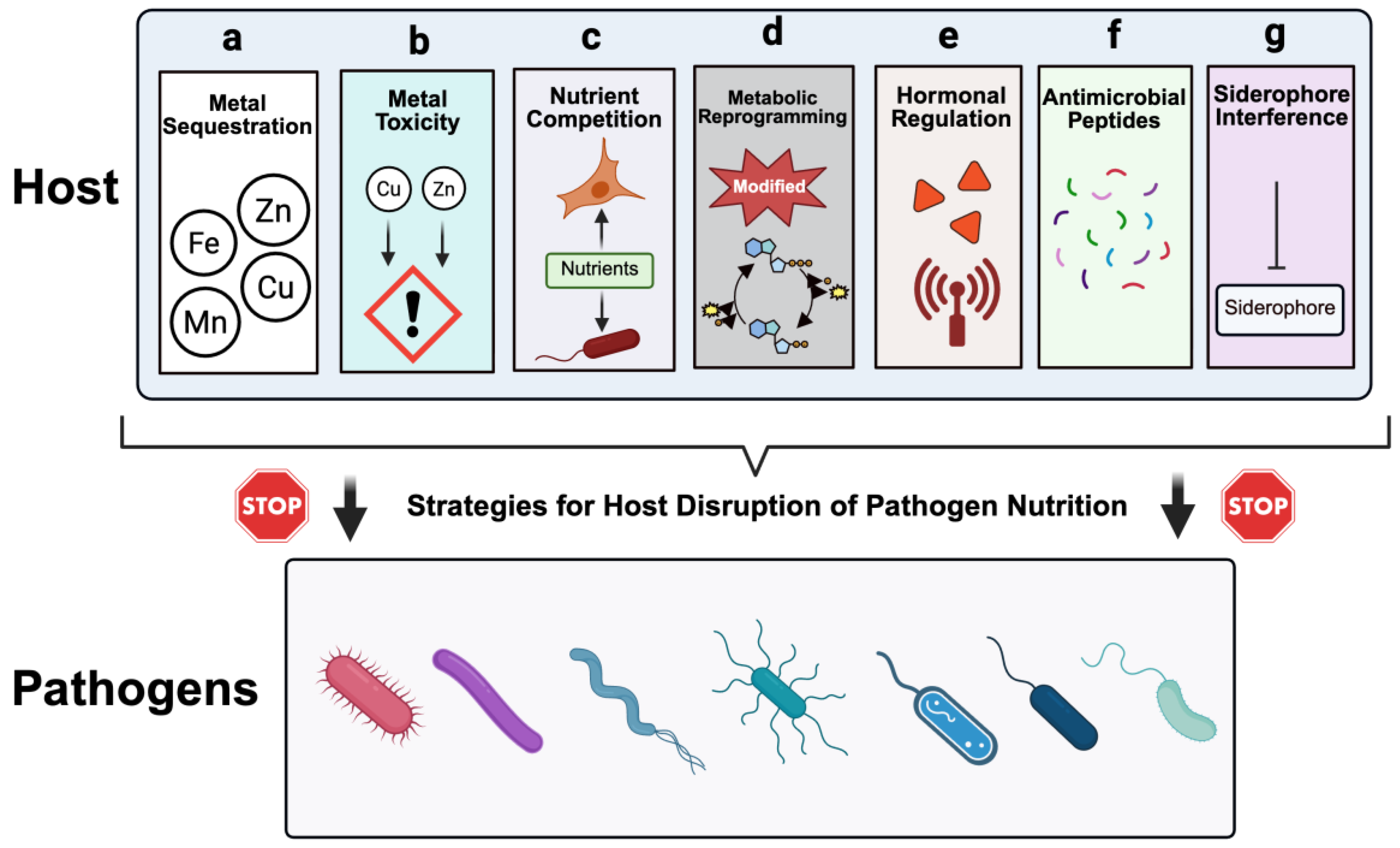

| S/n | Mechanism | Description | Main host factors | Targeted nutrients | Impact on pathogen | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metal sequestration | Host proteins bind essential transition metals firmly, restricting their availability to invading microbes. | Ferritin, lactoferrin, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, hemopexin, haptoglobin. | Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn. | Limits cofactor accessibility for bacterial enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and ribonucleotide reductase, thereby impairing replication. | Neutrophil lactoferrin reduce iron accessibility to Staphylococcus aureus, calprotectin sequesters zinc and manganese from Candida albicans | [5,18,19,20] |

| 2 | Metal Toxicity | Host intentionally delivers toxic levels of certain transition metals into pathogen-containing compartments. | Copper transporters (ATP7A, ATP7B), Zinc transporters (ZIP8, ZnT family), NRAMP1 (SLC11A1). | Excess Cu or Zn causing toxicity and/or replacing Fe/Mn. | Overwhelms microbial detoxification systems, causes mis-metalation, and interferes with critical metabolic processes. | Copper toxicity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Zinc-mediated intoxication of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [5,17,21,22] |

| 3 | Nutrient competition | Host cells outcompete pathogens for limited nutrients in inflamed tissues. | Activated macrophages, neutrophils, T cells. | Fe, Glucose, fatty acids, amino acids like tryptophan and arginine. | Stress induced by starvation, forcing bacteria into alternative metabolic pathways or non-replicating forms. | Gut commensals competing with Salmonella enterica for iron and carbon sources decrease pathogen colonization | [4,23,24] |

| 4 | Metabolic reprogramming | Host cells shift metabolic flux to starve pathogens, such as Warburg-like glycolysis, and reduced amino acid availability | HIF-1α, mTOR, autophagy pathways. | Glucose, glutamine, arginine, serine. | Limits access to central carbon and nitrogen sources | Macrophage glycolytic reprogramming restricting Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth and altering CCV environment for Coxiella burnetii. | [4,25,26] |

| 5 | Hormonal regulation | Hormones and inflammatory cytokines regulate systemic nutrient availability. | Hepcidin, TNF-α, IL-6. | Iron via regulation of ferroportin. | Reduces plasma iron, trapping it in macrophages and hepatocytes. | IL-6–induced hepcidin release suppressing iron availability during Salmonella infection. | [10,14] |

| 6 | Production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) | AMPs bind essential metals and exert direct antimicrobial effects. | Psoriasin (S100A7), calprotectin (S100A8/A9), defensins. | Zn, Mn. | Blocks metalloenzyme activity, triggers oxidative stress. | Calprotectin limiting Staphylococcus aureus growth in neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). | [20,27,28] |

| 7 | Siderophore interference | Host proteins arrest or neutralize bacterial siderophores to block iron retrieval. | Lipocalin-2 (NGAL), siderocalin. | Iron via siderophore sequestration. | Suppresses iron uptake despite active siderophore production. | Lipocalin-2 binding Escherichia coli enterobactin, blocking bacterial iron acquisition. | [29,30,31,32] |

| S/N | Therapeutic strategy | Mechanism of action | Examples/clinical trials | Challenges | Translational outlook |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iron chelation therapy | Starves pathogens of iron by binding free iron, mimicking host nutritional immunity | Deferasirox and its derivatives used against Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, and Cryptococcus neoformans [192,193]; Deferiprone as an adjunctive therapy against Mycobacterium abscessus [194,195]; Lactoferrin supplementation in trials studies for neonatal sepsis [196,197]. | Risk of host iron depletion, impaired immune function, and anemia. | Early / late clinical (iron chelators already approved for other indications; infection-specific use experimental). |

| 2 | Metal supplementation to cause toxicity | Deliver toxic levels of metals such as zinc, copper, or manganese into pathogen-containing compartments | Zinc oxide nanoparticles antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacillus subtilis [198,199,200]; Copper ionophores such as disulfiram, elesclomol studied for antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae [201,202,203] | Balancing pathogen killing with minimal host toxicity | Preclinical / early clinical. |