1. Introduction

The standard CDM model describes the cosmic microwave background (CMB), large–scale structure, and the expansion history of the Universe with impressive precision, provided that most of the matter content is a cold, collisionless dark component. On galactic scales, however, the phenomenology is often more directly captured by empirical relations between baryons and kinematics, such as the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation, than by explicit halo models. This tension has motivated both particle–dark–matter scenarios and modifications of gravity or inertia.

In the particle picture, weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) are among the best studied candidates. Their thermal freeze–out naturally yields relic abundances of the right order, and their annihilation or decay could produce detectable gamma rays, cosmic rays, or neutrinos in regions of high dark–matter density such as the Galactic Centre, dwarf spheroidal galaxies, or galaxy clusters [

1,

2,

3]. After years of dedicated searches, no unambiguous spectral lines or morphology uniquely attributable to WIMPs have been found. Limits from dwarf spheroidals and the isotropic gamma–ray background strongly disfavour the simplest s–wave annihilation channels in the mass range from a few GeV to several TeV [

4,

5,

6].

An alternative is to modify dynamics rather than invoke new particles. The original Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) proposal [

7,

8,

9] introduces an acceleration scale

below which the effective gravitational law departs from Newton, thereby explaining the Tully–Fisher relation and many rotation curves with minimal free parameters. However, cluster mass profiles, cosmological structure formation, and gravitational lensing remain difficult to reconcile with a purely local MOND prescription [

10,

11,

12]. Relativistic completions such as TeVeS [

13] or bimetric and scalar–tensor theories add additional fields and complexities, and often still require some amount of unseen matter.

A third line of research considers nonlocal or bilocal extensions of general relativity, in which the Einstein tensor at

x depends on an integral over the energy–momentum tensor at other points

through a kernel

[

14,

15,

16]. Such kernels can arise as effective descriptions of quantum loops in curved spacetime, coarse–grained backreaction from inhomogeneities, or integrating out microscopic degrees of freedom. In their simplest cosmological incarnations they can mimic dark energy; with more structure they can also generate effective dark–matter–like behaviour.

The Future–Mass Projection (FMP) framework belongs to this latter class. It introduces a diffeomorphism–invariant bilocal kernel defined on a closed time path (CTP) contour and couples the Einstein tensor to an integral over the baryonic energy–momentum tensor along this contour [

17,

18]. The kernel is constrained by general covariance, CTP symmetry, and conservation of the total Noether charge. In the Newtonian limit this leads to a modified Poisson equation in which the source density is the sum of the local baryon density

and a nonlocal “future–mass” density

induced by the kernel. At the cosmological level, renormalization of the kernel yields a constant ratio

reproducing the effective dark–to–baryon ratio of

CDM without introducing new particles [

19].

On galactic and cluster scales, the same kernel can be parametrised by an amplitude

and a characteristic wavenumber

. In Fourier space one finds

where

is the baryonic Newtonian potential and

is a Lorentzian form factor induced by the bilocal kernel [

22]. In real space this behaves roughly like a Yukawa–type kernel with range

: local gravity is dominated by baryons, while at scales

an extended halo–like component appears. The same kernel modifies both rotation curves,

and gravitational lensing, where the deflection angle is amplified by a factor

with

and impact parameter

b [

21,

23].

Using this minimal parametrisation, FMP has been shown to fit a large sample of galaxies from the SPARC database [

24] with a single pair

, and to reproduce the lensing mass distribution of the Bullet Cluster and similar systems without particle dark matter [

21,

22]. The same parameter range is also consistent with solar–system post–Newtonian constraints and the speed of gravitational waves [

23].

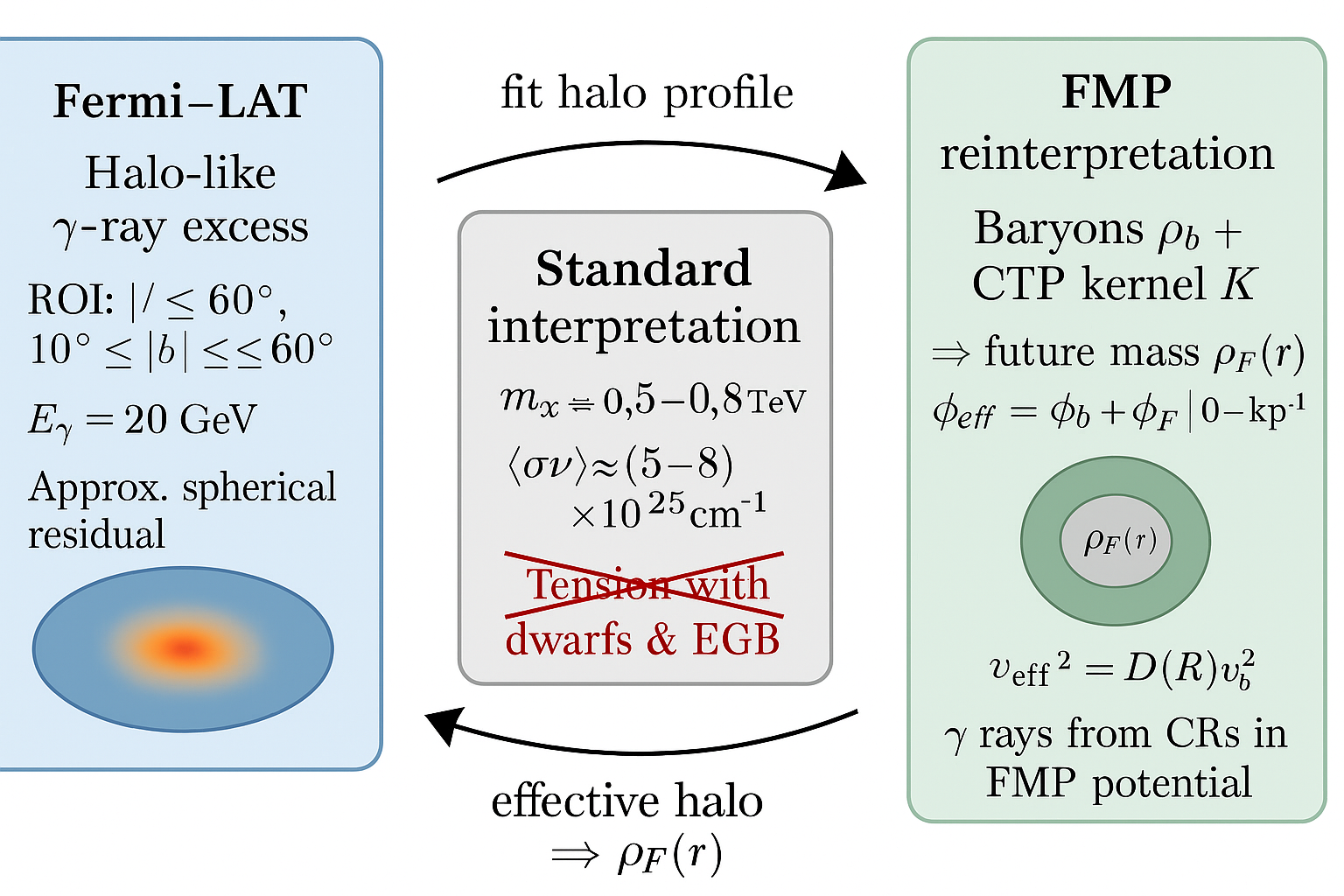

Recently, Totani [

25] analysed fifteen years of

Fermi–LAT data, focusing on a halo region

,

, and reported a statistically significant “Fermi halo”: a smooth, approximately spherical excess of diffuse gamma–ray emission peaking at

. After subtracting point sources, gas–correlated emission, inverse Compton components from GALPROP, Loop I, the Fermi Bubbles, and an isotropic template, the residual is well fitted by the square of an NFW density profile with scale radius

and local density

. If interpreted as annihilation of WIMPs into

, the best–fit parameters are

and

, which overshoot the canonical thermal cross section and are in tension with dwarf–galaxy limits, although the author argues that astrophysical and profile uncertainties may still leave room for a dark–matter interpretation [

25].

From the perspective of FMP, this result is naturally reframed. The Fermi analysis measures an effective smooth halo around the Milky Way whose morphology follows an NFW–like profile; in FMP such a halo arises automatically as the future–mass density sourced by baryons through the nonlocal kernel. Instead of inferring a large annihilation cross section for a new particle species, one can treat the NFW parameters inferred from gamma rays as constraints on for the Milky Way. The excess then constrains baryonic cosmic–ray emission and transport in this potential, and indeed limits any residual WIMP component.

The purpose of this paper is to make this connection explicit. In Sec.

Section 2 we briefly review the Newtonian limit of FMP and the Lorentzian kernel parametrisation. In Sec.

Section 3 we summarise the salient features of Totani’s analysis. In Sec.

Section 4 we map the inferred NFW halo onto FMP kernel parameters for the Milky Way and compare them to the values required by SPARC galaxies and cluster lensing. In Sec.

Section 5 we discuss the interpretation of the

bump as baryonic cosmic–ray emission in an FMP potential, and the status of WIMP annihilation as an upper limit. We conclude in Sec.

Section 6.

2. Overview of Future–Mass Projection Gravity

In FMP gravity the Einstein equations are generalised to a bilocal relation

where

is a causal kernel defined on a closed time path and

is the baryonic energy–momentum tensor [

17,

18]. The kernel is constructed to satisfy:

diffeomorphism invariance, such that implies a corresponding nonlocal conservation law for the CTP charge,

CTP symmetry between incoming and outgoing branches,

PPN safety in the weak–field, slow–motion regime,

a finite temporal horizon, reflecting a renormalised kernel with zero offset [

20].

In the Newtonian and quasistatic limit, the metric can be written as

and Eq. (

4) reduces to a modified Poisson equation,

where

is the local baryonic mass density and

is a nonlocal contribution from the kernel,

with

the Newtonian limit of

. The combination

is what would be inferred as “total mass” in a Newtonian analysis of dynamics or lensing.

In Fourier space, Eq. (

6) takes the form

where the second equality defines the dimensionless kernel amplitude

and form factor

. The minimal phenomenological choice consistent with the CTP construction and a finite horizon is the Lorentzian form in Eq. (

2),

with characteristic wavenumber

and range

.

This form factor leads to an effective dynamical amplification factor

for circular velocities at radius

R. At small radii,

, one has

and

, corresponding to a roughly isothermal halo. At large radii,

,

and the effective halo contribution decays.

The same kernel modifies gravitational lensing. In the thin–lens approximation the deflection angle for a light ray with impact parameter

b is amplified by

where

is an order–unity factor depending on the details of the kernel contraction in the null–geodesic limit [

21,

23].

On cosmological scales, averaging Eq. (

4) over large volumes and renormalising the kernel yields a homogeneous future–mass density

whose ratio to the baryonic density

is constant in time [

19],

This reproduces the effective dark–matter density of

CDM in the background Friedmann equations and in linear perturbations, while the nonlocal kernel handles the halo–like phenomenology on smaller scales.

Fits to SPARC rotation curves and cluster lensing indicate a preferred range

with modest scatter between galaxies of different mass and surface density [

21,

22]. In the following we will see that the Milky Way parameters implied by the

Fermi halo are consistent with this range.

3. Summary of the Fermi Halo Analysis

Totani [

25] analysed 15 years of

Fermi Large Area Telescope (LAT) data with the aim of searching for gamma rays from dark–matter annihilation in the Milky Way halo. The region of interest (ROI) is defined by Galactic longitudes

and latitudes

, excluding the bright Galactic plane. The photon energy range is

–

, and the UltraClean event class is used to minimise charged–particle contamination.

The observed intensity map in the ROI is modelled as a linear combination of:

point–source templates from the 4FGL catalogue,

gas–correlated emission components from GALPROP (neutral and ionised gas, decay),

inverse Compton scattering (ICS) templates for different interstellar radiation fields,

large–scale diffuse structures: Loop I and the Fermi Bubbles,

an isotropic background component.

The parameters of these templates are determined by a binned Poisson likelihood fit. To enhance sensitivity to smooth structures on halo scales, the fit is performed using cell sizes of order , rather than pixel–by–pixel.

After subtracting the best–fit combination of templates from the data, a residual component remains that:

is locally consistent with zero for and ,

shows a broad excess peaking at ,

exhibits an approximately spherical morphology centred on the Galactic Centre,

is well fitted by a spherically symmetric halo template with emissivity proportional to

, where

with best–fit scale radius

and local density

for a solar radius

.

The radial profile is slightly shallower than a pure NFW2 cusp in the innermost region, and can also be described by an Einasto profile with a modest core.

Systematic uncertainties are probed by:

varying the GALPROP parameters (halo height, source distribution, diffusion coefficients),

changing the Fermi Bubble templates (different energy bands or morphologies),

masking bright point sources instead of fitting them,

using the official LAT Galactic interstellar emission model (GIEM) as an alternative background, which includes non–template patches tuned to match observed residuals.

In all these tests, the qualitative behaviour of the residual halo persists: it rises from

GeV, peaks around 20 GeV, and becomes negligible above 200 GeV. In particular, a similar excess is found even relative to the GIEM, suggesting that the signal is not an artefact of template construction [

25].

If the halo residual is interpreted as gamma rays from WIMP annihilation into

, the best–fit parameters are

for a standard NFW profile normalised to

. The corresponding cross section is:

Totani emphasises that this tension does not provide a definitive exclusion, given uncertainties in the Milky Way halo profile, substructure, and dwarf–galaxy mass modelling, but cautions that independent confirmation is required before claiming a discovery of dark matter [

25].

For our purposes, the central output of Ref. [

25] is the effective NFW halo profile and its parameters

, derived from gamma–ray data, which can be reinterpreted as an FMP future–mass distribution.

4. Mapping the Fermi Halo to FMP Kernel Parameters

In the FMP framework, what is traditionally called “dark matter halo” is replaced by the future–mass density

induced by the bilocal kernel acting on baryons. For a given baryonic mass distribution

, the nonlocal term in Eq. (

6) generates a smooth extended halo whose detailed shape depends on

.

In practice, phenomenological analyses can proceed in either of two equivalent ways:

Here we adopt the second approach, using Totani’s inferred NFW halo as a constraint on for the Milky Way.

4.1. Effective mass profile of the Milky Way halo

The NFW parameters

inferred in Ref. [

25] correspond to a halo profile

with

and local density

at

. The corresponding enclosed mass is

For

–

, typical values are

and

, comparable to standard Milky Way halo models.

Let

denote the observed circular velocity profile of the Milky Way and

the contribution from baryons (disk + bulge + gas) computed from an independent mass model. At

, a representative estimate is

implying a dynamical amplification factor

This is exactly the kind of amplification that, in Newtonian language, is attributed to the NFW halo fit by Totani.

4.2. Constraint on from the Milky Way

In FMP,

is given by Eq. (

10),

where we have written

. At

, Eq. (

19) yields

Solving for

in terms of

gives

For

in the range indicated by galaxy and cluster fits, cf. Eq. (

13), we obtain:

: , so and ;

: , so and ;

: , so and .

Thus the Milky Way amplification implied by the

Fermi halo is consistent with

in excellent agreement with the range deduced from independent FMP fits to external galaxies and clusters [

21,

22].

The mild core suggested by the Fermi halo profile—better modelled by an Einasto profile than by a strict NFW cusp—also fits well with the real–space behaviour of the Lorentzian kernel. The Yukawa–like fall–off on scales naturally smooths the innermost potential relative to a pure cusp, while still approximating an NFW–like profile at intermediate radii.

In summary, once the NFW halo inferred from gamma rays is identified with the FMP future–mass distribution of the Milky Way, the resulting are neither extreme nor tuned: they fall squarely in the region already required by FMP to explain other gravitational phenomena.

5. Gamma–Ray Emission in the FMP Potential

In the WIMP interpretation of the

Fermi halo, the gamma–ray emissivity is taken to be proportional to

,

where

is the spectrum per annihilation. The effective density

is simply the NFW fit, and the cross section is given by Eq. (

15). As discussed in Sec.

Section 3, this leads to tensions with dwarf–galaxy and extragalactic gamma–ray limits.

In FMP, the halo profile fitted by Totani is not a separate particle component, but the future–mass density

that appears in the gravitational Poisson equation. The gamma–ray emissivity remains of baryonic origin, dominated by cosmic–ray (CR) interactions:

with

and

Here

and

are the proton and electron cosmic–ray densities,

is the gas density, and

is the target photon energy density.

The key difference under FMP is not the microphysics of CR interactions, but the large–scale gravitational potential in which CRs diffuse and advect. The steady–state CR transport equation in the halo can be written schematically as

where

D is the diffusion coefficient,

is an advective or convective velocity,

encodes continuous energy losses,

accounts for catastrophic losses, and

is the source term.

The FMP future–mass potential

contributes to the total gravitational potential

, thereby affecting both the CR confinement volume and any large–scale outflows. A deeper, more extended potential halo increases the residence time of CRs at large radii, enhances the high–latitude gas density relative to a purely baryonic potential, and changes the balance between diffusion and advection. These modifications can produce an extended, approximately spherical halo of gamma–ray emission that is qualitatively similar to the one inferred in Ref. [

25], without requiring

annihilation.

In a simple toy model, one can assume that:

CR sources follow the star–forming disk,

CRs propagate into the halo under diffusion and a slow FMP–induced inflow velocity ,

the gas density falls off with radius but is partially supported by the deeper FMP potential,

the result is a smooth CR halo with density that traces the effective potential.

Under these assumptions, the line–of–sight integral for the gamma–ray intensity,

naturally produces a large–scale halo component whose angular profile can approximate an NFW–like shape in projection, especially if

depends exponentially on

.

A detailed CR transport calculation in an FMP potential is beyond the scope of this work and is left for future study. The central point here is that once the gravitational potential is fixed by , the same CR physics used in standard GALPROP–based modelling can generate an extended gamma–ray halo, making baryonic explanations more plausible than in a purely baryon–only potential.

Finally, suppose that WIMPs do exist on top of FMP, contributing a subdominant true dark–matter density

. The

Fermi halo analysis would then have double–counted the FMP future mass as if it were

. To avoid overshooting the observed rotation curve and lensing, the true particle component must be at most a modest fraction of the effective NFW halo. A conservative estimate is that only

of the dynamical halo can be attributed to particles; the rest is already encoded in

. This would rescale Eq. (

15) to

which is closer to, but still somewhat above, existing limits. In other words, in an FMP Universe the

Fermi halo does not provide evidence

for WIMPs, but rather an upper limit on any such component in addition to the future mass.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The

Fermi–LAT detection of a smooth, approximately spherical gamma–ray halo around the Milky Way, with a spectrum peaking near

and morphology well fitted by an NFW profile, has naturally attracted attention as a potential indirect signal of dark–matter annihilation [

25]. If interpreted in the standard WIMP framework, the preferred cross section lies significantly above both the canonical thermal relic value and existing limits from dwarf spheroidal galaxies and the extragalactic gamma–ray background. Although uncertainties in the Milky Way halo profile and substructure may soften this tension, the particle–dark–matter interpretation remains stressed.

In the Future–Mass Projection framework, the same halo profile is not mysterious. FMP predicts an extended future–mass density around baryonic mass distributions, produced by a bilocal kernel that correlates points along a closed time path. In the Newtonian limit this modifies the Poisson equation and yields an effective amplification of the Newtonian potential controlled by a Lorentzian form factor with parameters . Fits to external galaxies and clusters already indicate and .

By identifying the NFW halo inferred from Fermi gamma–ray data with the Milky Way’s future–mass distribution , we have shown that the required amplification of the rotation curve at the solar radius implies –2.2 for –. These values lie squarely within the range already favoured by SPARC rotation curves and Bullet–Cluster lensing, and are compatible with the cosmological ratio . The mild core in the halo profile, better fitted by an Einasto law than by a pure NFW cusp, is a natural consequence of the finite FMP horizon.

In this reinterpretation, the gamma–ray excess originates from baryonic cosmic–ray emission in the FMP–modified potential, not from annihilation. The effective halo detected by Fermi becomes a calibration point for the nonlocal kernel, rather than a first glimpse of a new particle. If WIMPs exist at all, their contribution to the Milky Way potential must be subdominant to , and the Fermi halo provides an upper bound rather than a detection.

Future work should include:

a full CR transport calculation in the FMP potential of the Milky Way, using GALPROP–like tools with an FMP gravity module,

a joint fit of Fermi halo data, rotation curves, and lensing constraints for the Milky Way in the FMP framework,

applications of the same methodology to other galaxies with gamma–ray halo measurements, if available,

a systematic assessment of how FMP modifies global extragalactic gamma–ray backgrounds relative to standard CDM.

From the point of view of FMP gravity, the new Fermi halo is therefore not a challenge but an additional, nontrivial test that the same bilocal kernel can pass simultaneously on galactic, cluster, cosmological, and now gamma–ray scales.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Data Availability Statement

This study uses published

Fermi–LAT data and results. All data and analysis products referenced are available in Ref. [

25] and in the public

Fermi–LAT archives.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- G. Jungman, M. Kamionkowski and K. Griest, Supersymmetric dark matter, Phys. Rept. 267, 195–373 (1996).

- G. Bertone, D. Hooper and J. Silk, Particle dark matter: Evidence, candidates and constraints, Phys. Rept. 405, 279–390 (2005).

- S. Profumo, An Introduction to Particle Dark Matter (World Scientific, 2017).

- M. Ackermann et al. (Fermi–LAT Collaboration), Searching for dark matter annihilation from Milky Way dwarf spheroidal galaxies with six years of Fermi Large Area Telescope data, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 231301 (2015).

- M. Ackermann et al. (Fermi–LAT Collaboration), The spectrum of isotropic diffuse gamma-ray emission between 100 MeV and 820 GeV, Astrophys. J. 799, 86 (2015).

- B. S. Acharya et al. (CTA Consortium), Science with the Cherenkov Telescope Array (World Scientific, 2019).

- M. Milgrom, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis, Astrophys. J. 270, 365–370 (1983).

- M. Milgrom, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics: Implications for galaxies, Astrophys. J. 270, 371–383 (1983).

- M. Milgrom, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics: Implications for galaxy systems, Astrophys. J. 270, 384–389 (1983).

- G. W. Angus, Missing mass in clusters in a MOND universe, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 387, 1481–1488 (2008).

- D. Clowe, M. Bradac, A. H. Gonzalez, M. Markevitch, S. W. Randall, C. Jones and D. Zaritsky, A direct empirical proof of the existence of dark matter, Astrophys. J. Lett. 648, L109–L113 (2006).

- Planck Collaboration, Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters, Astron. Astrophys. 594, A13 (2016).

- J. D. Bekenstein, Relativistic gravitation theory for the modified Newtonian dynamics paradigm, Phys. Rev. D 70, 083509 (2004).

- S. Deser and R. P. Woodard, Nonlocal cosmology, Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 111301 (2007).

- M. Maggiore and M. Mancarella, Nonlocal gravity and dark energy, Phys. Rev. D 90, 023005 (2014).

- A. O. Barvinsky, Nonlocal gravity: A summary, Phys. Part. Nucl. 44, 213–220 (2013).

- F. Lali, Diffeomorphism invariant bilocal gravity for Future–Mass Projection and Noether conservation, preprint (2025).

- F. Lali, A closed time path kernel for Future–Mass Projection gravity, preprint (2025).

- F. Lali, A constant renormalized gravity sector in Future–Mass Projection, preprint (2025).

- F. Lali, A finite horizon, zero–offset kernel for Future–Mass Projection gravity, preprint (2025).

- F. Lali, Slinky Future–Mass Projection explains the Bullet Cluster without particle dark matter, preprint (2025).

- F. Lali, Two–channel Future–Mass Projection versus ΛCDM on SPARC rotation curves, preprint (2025).

- F. Lali, Solar–system PPN safety and gravitational wave speed in Future–Mass Projection gravity, preprint (2025).

- F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh and J. M. Schombert, SPARC: Mass models for 175 disk galaxies with Spitzer photometry and accurate rotation curves, Astron. J. 152, 157 (2016).

- T. Totani, 20 GeV halo-like excess of the Galactic diffuse emission and implications for dark matter annihilation, J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 11, 080 (2025). arXiv:2507.07209.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).