1. Introduction

Solar energy plays a central role in sustainable energy transitions due to its high availability and low environmental impact. Solar air heaters (SAHs), widely used in low temperature applications such as space heating, agricultural drying [

1], and sludge treatment [

2], have attracted increasing interest because of their simple design, low cost, and operational safety. SAH transfers absorbed solar radiation to an air stream by natural or forced convection; however, the inherently low convective heat transfer coefficient between the absorber and air limits overall performance. Moreover, the low density and heat capacity of air require relatively high mass flow rates, while the low power density of solar energy (~1 kW/m²) [

3] necessitates larger collector areas. These constraints underline the importance of optimizing airflow behavior and heat transfer enhancement.

A wide range of geometric modifications—such as grooved surfaces [

4], horizontal barriers [

5], fins [

6], and various baffle arrangements [

7]—have been proposed to promote turbulence and improve thermal performance. Several recent studies have confirmed the effectiveness of these enhancements [

8,

9,

10], while others have examined the effects of baffle length [

11], configuration [

12], and combined vane–baffle structures [

13] on thermo-hydraulic behavior. Despite these advances, most SAHs still operate passively and cannot adjust their internal flow structure in response to changing environmental conditions. Existing studies typically analyze thermo-hydraulic parameters (Re, Nu, ΔP) [

14,

15,

16] or energy–exergy–sustainability metrics [

17,

18,

19] separately. Optimization approaches such as Taguchi, TOPSIS, and Grey–Taguchi [

20,

21,

22] provide valuable design insights but function offline and cannot adapt in real time. Recent microcontroller based attempts offer limited automation [

23,

24,

25], yet they lack adaptive baffle mechanisms or real time outlet temperature stabilization.

This situation reveals a clear research gap: no reported experimental SAH simultaneously incorporates adjustable baffle geometry, active real time control, and integrated thermal–energy–exergy assessment within a single system. Such adaptive capabilities are especially important for applications requiring precise outlet temperature regulation, including agricultural drying, HVAC, and industrial low temperature heating.

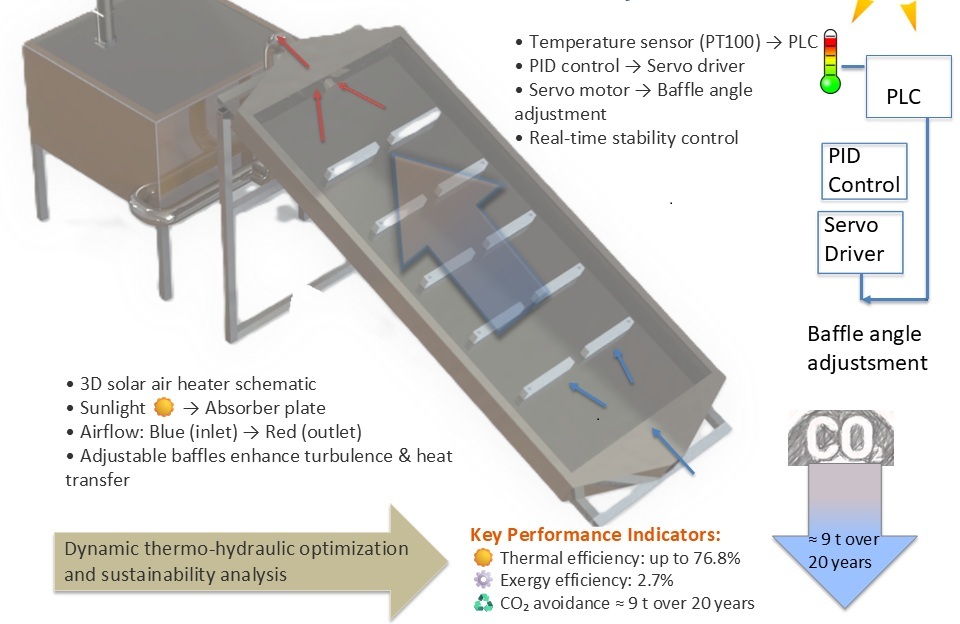

To address this gap, the present study develops a PLC controlled SAH equipped with real time adjustable baffle angles. The baffle inclination is actively modified to reshape the internal flow field, while a PLC algorithm maintains stable outlet temperatures commonly used in drying processes (54 °C and 60 °C). Thermal, energy, exergy, and sustainability (3E–CO₂) indicators are experimentally evaluated under outdoor conditions. The primary objective is to quantify the benefits of adaptive geometry control and to demonstrate improvements in temperature stability, controllability, and overall thermo-hydraulic performance compared with conventional passive SAH configurations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

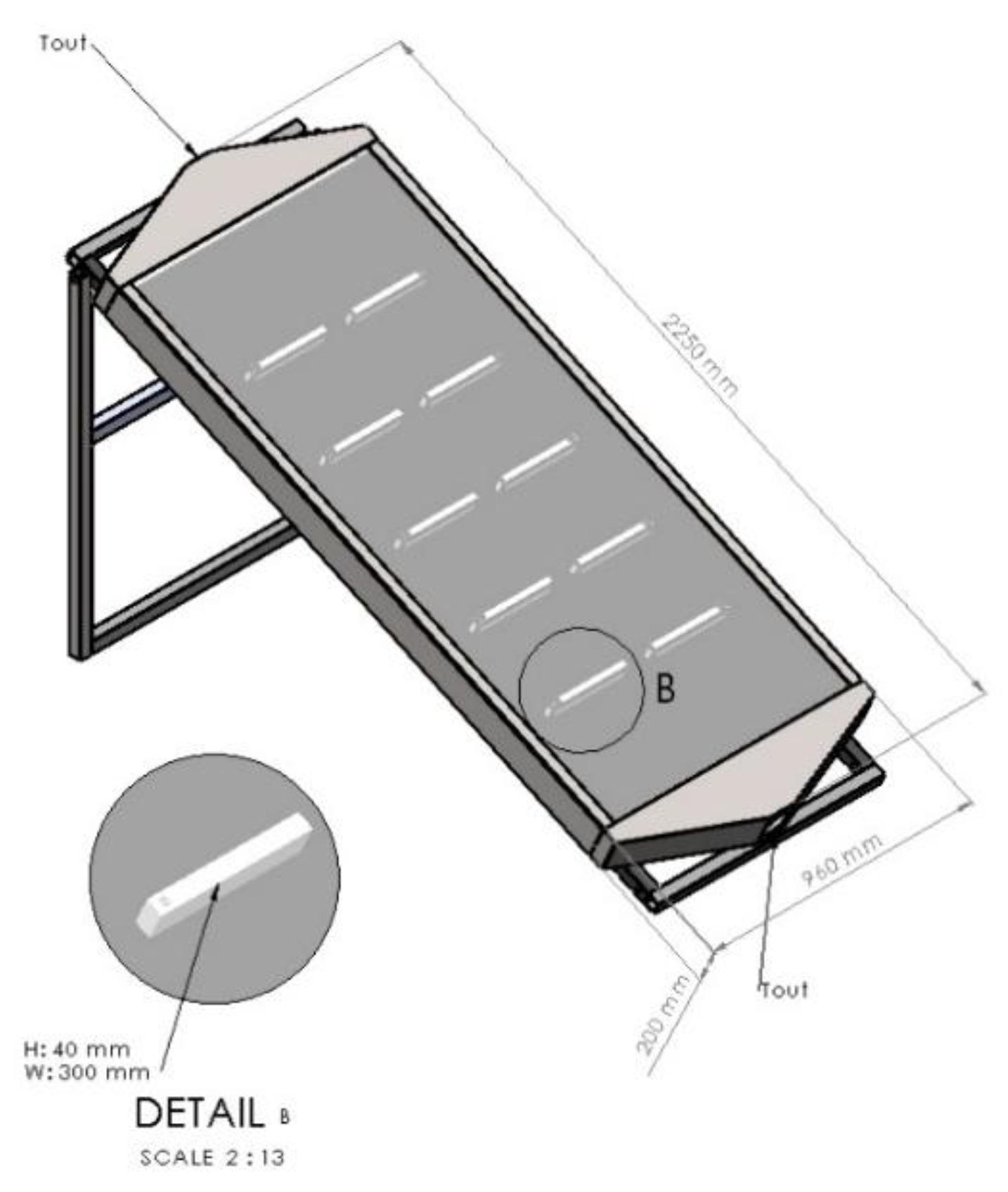

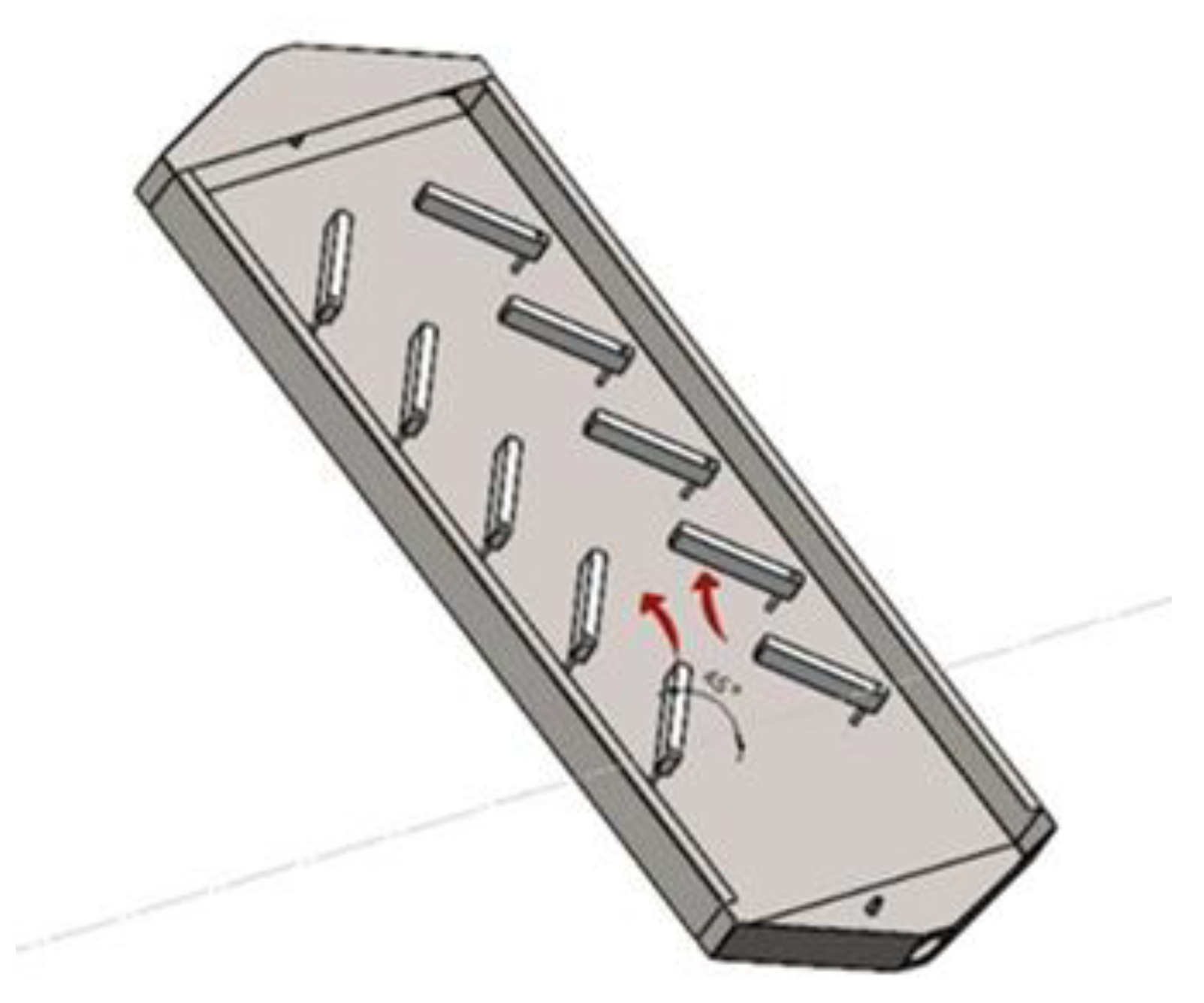

The experimental solar air heater (SAH) was constructed from 1 mm galvanized steel with overall dimensions of 2250 × 940 × 200 mm. The front cover consisted of heat resistant tempered glass with an average transmittance of 0.90, while the absorber plate was made of 4 mm matte black aluminum (α ≈ 0.95). The general geometry of the collector and the locations of the adjustable baffles are shown in

Figure 1.

The system incorporates ten rectangular aluminum baffles mounted along the airflow path. All baffles are fixed to a shared rotating shaft, enabling simultaneous adjustment of their inclination between 0 ° and 90 °. This rotation modifies the internal flow resistance and turbulence level, allowing dynamic control of heat transfer characteristics.

Figure 2 illustrates the airflow direction and the working principle of the baffle rotation mechanism.

The internal height of the collector is 200 mm, where the lower 130 mm houses the absorber plate and rotating shaft assembly, and the upper 70 mm forms the primary airflow passage. Lateral surfaces were insulated with glass wool to reduce heat losses. A 100 mm axial fan placed at the outlet created negative pressure at the inlet to induce forced convection through the collector. Air temperatures at the inlet, mid section, and outlet were measured using PT100 resistance sensors. All sensor data were transferred to a Mitsubishi PLC, which controlled the servo motor driven baffles to maintain the target outlet temperature. A Delta HMI panel was used to monitor real time operating parameters including baffle position, airflow temperature, and fan speed.

2.2. Outdoor Performance Evaluation

The SAH system was installed outdoors at the Hasan Ferdi Turgutlu Faculty of Technology, Manisa Celal Bayar University (38.4919 ° N, 27.7069 ° E). The collector was oriented southward with a 30 ° tilt, corresponding to the local latitude. The test platform provided unobstructed solar exposure and natural airflow.

Figure 3 shows the outdoor installation during performance testing.

Experiments were carried out between 9 and 29 August 2023 coinciding with the peak agricultural drying season in Türkiye to ensure high irradiance and low humidity. Tests were conducted only on clear sky days. During measurements, the global solar irradiance remained at 850 ± 25 W/m², wind velocity was below 0.5 m/s, and ambient temperature ranged between 41–45 °C. Measurements were performed between 10:00 and 16:00, corresponding to the highest daily solar availability. Before each test, the system was operated for 15–20 minutes to ensure steady state conditions.

2.3. Dynamic Response and Control Strategy

The dynamic behavior of the PLC controlled system was evaluated by applying step changes to the baffle inclination angles. Variations in baffle angle alter internal flow resistance and turbulence, leading to changes in heat transfer rate and outlet temperature. When a new setpoint is applied, the PLC receives real time temperature feedback, updates the control signal, and adjusts the fan speed and servo motor position accordingly.

A delay of approximately 3 seconds was observed between the baffle angle command and the onset of fan speed adjustment due to PLC scan cycle and driver response time. After the adjustment, the outlet air temperature converged to the target value within approximately 10 seconds, stabilizing within a ±0.5 °C band. No significant overshoot was observed (<3%), indicating proper controller tuning. Time dependent data extracted from the HMI showed a temporal measurement uncertainty of ±0.5 seconds. These results confirm that the proposed control architecture provides rapid and stable convergence—typically within 3–10 seconds after a geometric change, ensuring reliable operation under outdoor conditions.

2.4. Experimental Procedure

Two outlet temperatures 54 °C and 60 ° C, were selected because they are widely used in solar assisted drying and low temperature thermal processes. The objective was to assess the system’s ability to maintain stable thermal output across varying internal flow configurations.

The baffles were positioned at seven inclination angles: 0 °, 15 °, 30 °, 45 °, 60 °, 75 °, and 90 °. For each angle, the PLC algorithm automatically adjusted the fan speed and baffle position based on real time feedback to maintain the target outlet temperature. This closed loop operation enabled direct evaluation of the system’s adaptive thermal response.

All tests were performed under identical outdoor conditions for consistent comparison between geometric configurations. The collector design parameters relative roughness ratio (e/Dₕ = 0.0397) and pitch to height ratio (p/e = 9.17) were selected according to recommended ranges for artificially roughened SAH ducts.

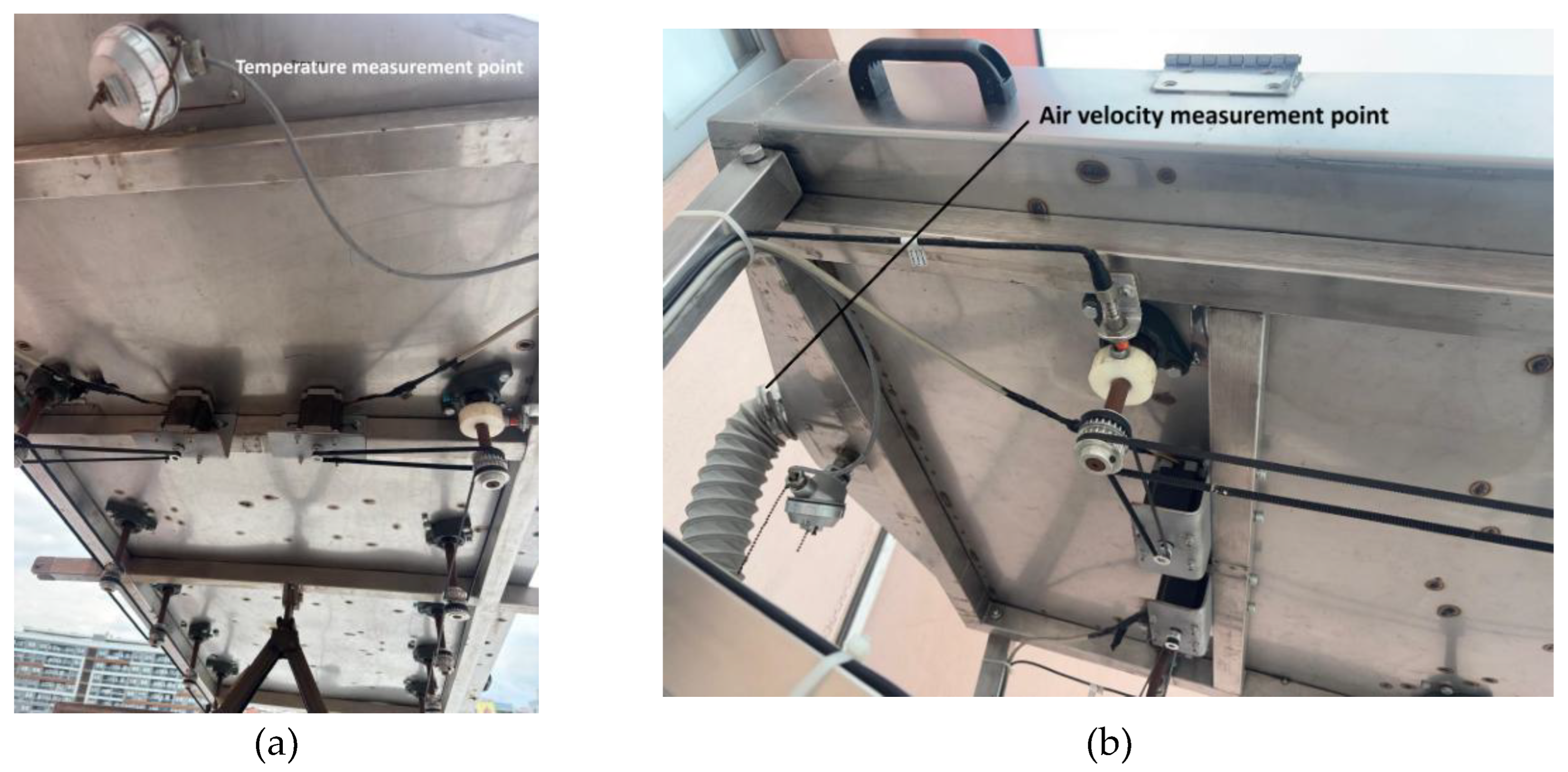

Figure 4 presents the measurement and control points, including PT100 sensor positions, flow rate measurement location, and the servo driven baffle mechanism.

2.5. Instrumentation and Measurement Accuracy

All measurements were used to compute energy efficiency, exergy efficiency, and overall 3E performance under each baffle configuration. Air velocity at the inlet was measured using a Testo 440dP hot wire anemometer placed 20 mm upstream of the opening to minimize flow disturbance. Inlet and outlet temperatures were recorded using Emko RTKR M06 L050.1 PT100 sensors integrated into the PLC. Surface temperature distribution was measured using a FLIR 62101 0101 thermal camera.

Solar irradiance was measured with a calibrated pyranometer (±2% accuracy) positioned parallel to the glazing. Ambient temperature and humidity were monitored with a digital thermo hygrometer placed near the test platform. All sensors were connected to the PLC based data logging system, which recorded data every 5 seconds.

A summary of the measurement instruments and their uncertainties is presented in

Table 1.

2.6. Uncertainty Analysis

The uncertainty of each measured variable was independently evaluated, and combined uncertainty was computed using the standard propagation of errors formula:

For energy efficiency calculations, uncertainties were mainly affected by temperature differences, mass flow rate, and solar irradiance measurements. The resulting combined uncertainty for energy efficiency was ±3.1%. In the exergy analysis, small temperature differences between outlet and ambient air made temperature measurement accuracy more influential, giving a total exergy efficiency uncertainty of ±3.8%. All uncertainty values remained below ±4%, consistent with the ±5% limit typically reported in the literature.

3. Theoretical Framework

A comprehensive evaluation of a solar air heater (SAH) requires simultaneous consideration of fluid flow behavior, convective heat transfer, thermodynamic efficiency, and environmental impact. Traditionally, SAH research has emphasized thermo-hydraulic parameters particularly the relationships among Reynolds number (Re), Nusselt number (Nu), and friction factor (f) to assess flow regime and turbulence intensity [

26,

27]. However, performance assessment based solely on energy efficiency provides an incomplete picture. Since solar thermal systems must convert absorbed energy into useful work with minimum losses, an integrated analysis incorporating exergy and sustainability indicators is essential. In this study, the overall performance is evaluated through a combined framework that links Re, Nu, geometric roughness (e/Dₕ), frictional losses, exergy efficiency (

), and CO₂ mitigation potential. This approach provides a holistic understanding of the SAH’s thermodynamic and ecological behavior.

3.1. Dimensionless Geometric Parameters

The SAH examined in this work contains ten rectangular baffles arranged in five opposing pairs to promote turbulence and enhance convective heat transfer. The effective absorber area is 1760 × 860 mm, while the total collector size is 2200 × 940 mm. Each baffle has a length of 275 mm, height of 30 mm, and thickness of 4 mm, with a pitch of 300 mm between consecutive rows. The hydraulic diameter of the rectangular duct is calculated as:

where

W and

H denote duct width and height. Two key dimensionless parameters characterize the geometry: the relative roughness ratio (e/Dₕ) and the pitch to height ratio (p/e). For the present design, these values are e/Dₕ = 0.0397 and p/e = 9.17, which fall within the recommended ranges for artificially roughened SAH ducts (e/Dₕ ≈ 0.03–0.05; p/e ≈ 7–10). Such parameters strongly influence the formation of recirculation zones and reattachment lengths, thereby balancing heat transfer enhancement against pressure drop penalties [

26,

27]. The Nusselt number, which defines the convective heat transfer coefficient, is expressed as:

Because the Prandtl number remains nearly constant within the temperature range of interest, Nu can be modeled as a function of Re and baffle angle (θ). Based on logarithmic regression of experimental data, the following correlations were obtained:

For a 54 °C outlet temperature:

For a 60 °C outlet temperature:

The Reynolds number, representing the flow regime, is calculated as:

where ρ is air density, μ is dynamic viscosity, and

V is the mean air velocity. Temperature dependent properties were obtained from Engineering Equation Solver (EES). As with conventional SAHs, increasing

Re enhances turbulence and heat transfer but incurs additional frictional losses. The experimentally derived friction factor correlation valid for both outlet temperatures is:

This relation provides a generalized hydrodynamic model for the baffled rectangular duct.

3.2. Energy, Exergy, and Sustainability Analyses

Energy and exergy analyses form the core of thermodynamic assessment in solar thermal systems. While energy analysis quantifies the total heat transferred, exergy analysis evaluates the useful work potential of that energy and identifies sources of irreversibility [

28,

29]. Numerous studies have shown that combined energy–exergy evaluation is essential for optimal SAH design [

30,

31,

32].

3.2.1. Energy Analysis

Applying a steady state energy balance to the SAH control volume yields:

Because the mass flow rate remains constant:

and enthalpy is expressed as:

The solar energy input is:

Substituting into Equation (8):

The collector energy efficiency becomes:

For a glazed collector with transmissivity–absorptivity product (τα):

yielding the practical efficiency:

3.2.2. Exergy Analysis

The exergy balance for a steady state control volume is [

34]:

Incoming exergy consists of solar and inlet air exergy:

Solar exergy is computed using the Petela model [

35]:

with

T_r = 5777 K. The inlet air exergy is:

Radiative exergy loss:

with:

The exergy efficiency is:

3.2.3. Sustainability and Environmental Assessment

The sustainability index (SI), widely used in exergy based environmental evaluations, is defined as:

A higher SI indicates reduced irreversibility and improved thermodynamic sustainability. Classification ranges are shown in

Table 2.

The avoided CO₂ emissions associated with replacing fossil fuel based heating are estimated as:

where the annual useful energy output is:

Total avoided emissions over the system lifetime (n = 20 years):

An emission factor of EF = 0.434 kg CO₂/kWh was used, corresponding to the national grid average in Türkiye [

36].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

The validated dataset was then used to characterize the thermo-hydraulic behavior of the collector, beginning with an examination of the heat transfer response under varying Reynolds numbers and baffle inclination angles.

4.1.1. Heat Transfer Characteristics (Nu–Re–θ)

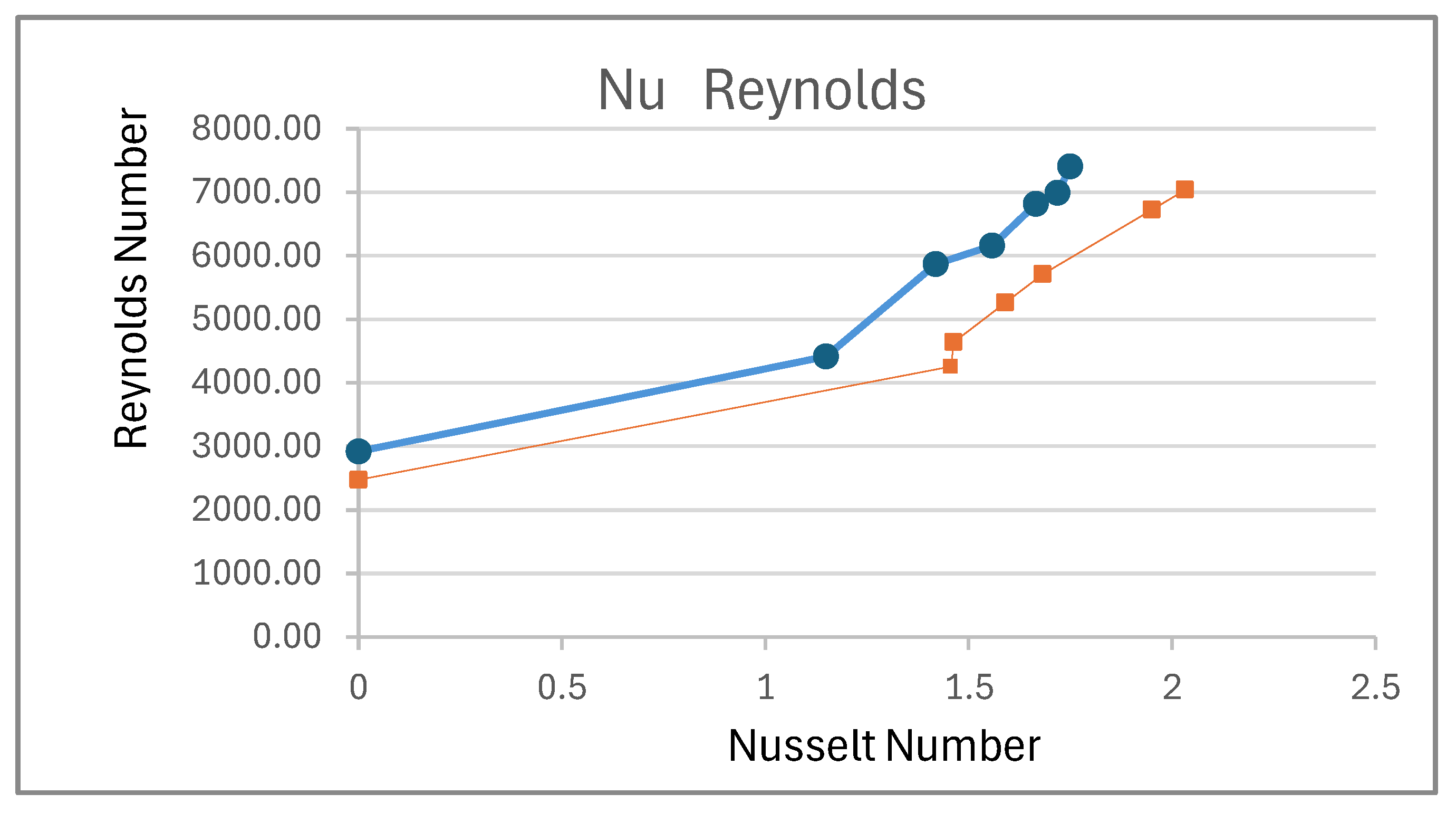

After establishing the overall thermo-hydraulic trends, the heat transfer behavior was examined in detail through the Nusselt–Reynolds relationship. As shown in

Figure 5, the Nusselt number increases with Reynolds number for both outlet temperatures (54 °C and 60 °C), confirming that forced convection is the dominant heat transfer mechanism inside the channel. The influence of the adjustable baffle inclination is more evident at 54 °C, while at 60 °C its effect weakens due to turbulence saturation at higher Reynolds numbers.

The developed experimental correlations exhibit strong consistency with the measured data (R² = 0.922 and MAPE = 3.48% for 54 °C; R² = 0.959 and MAPE = 2.36% for 60 °C). These findings verify that the proposed Nu–Re–θ models are statistically robust and directly applicable to engineering design and performance prediction.

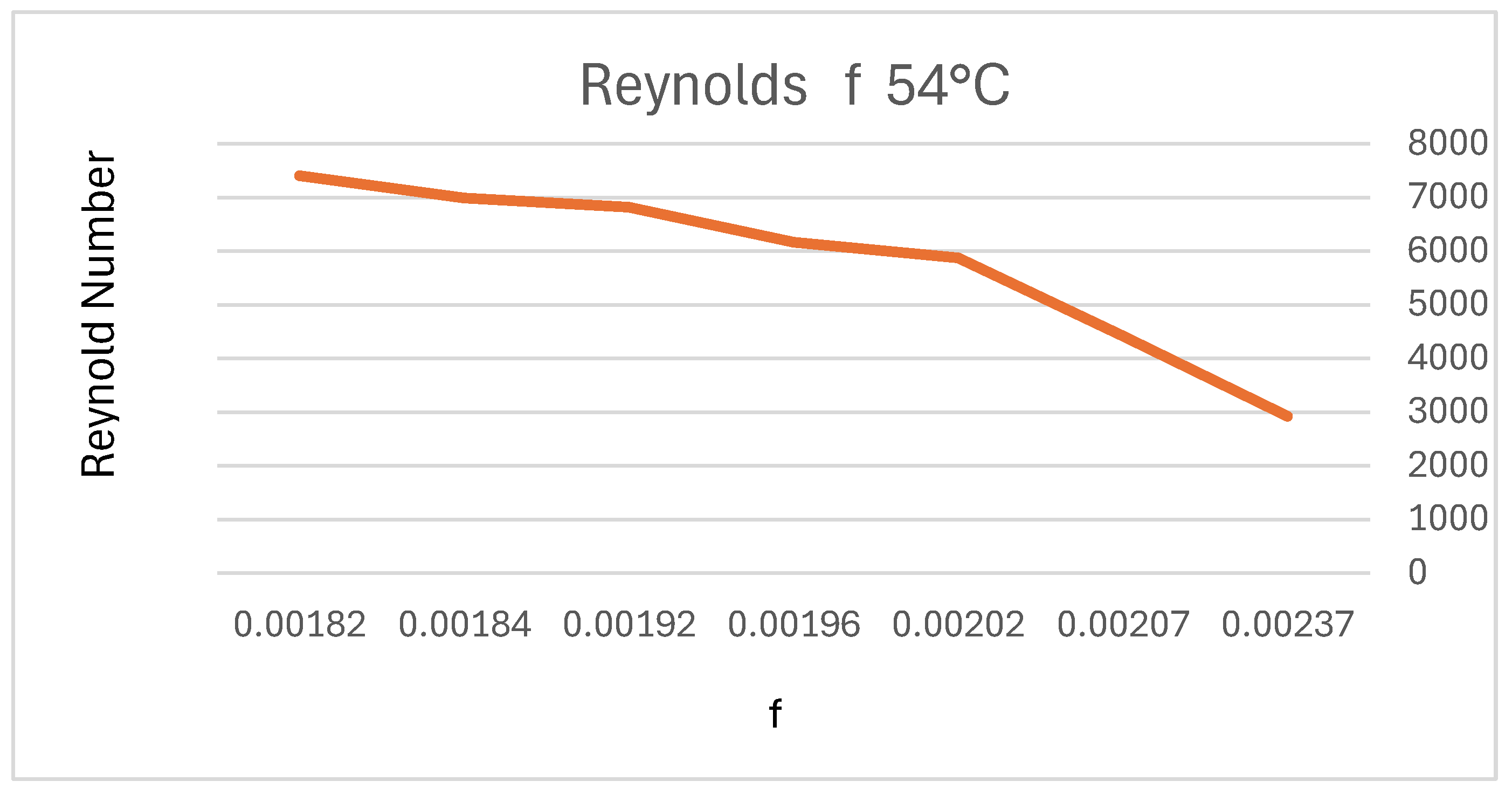

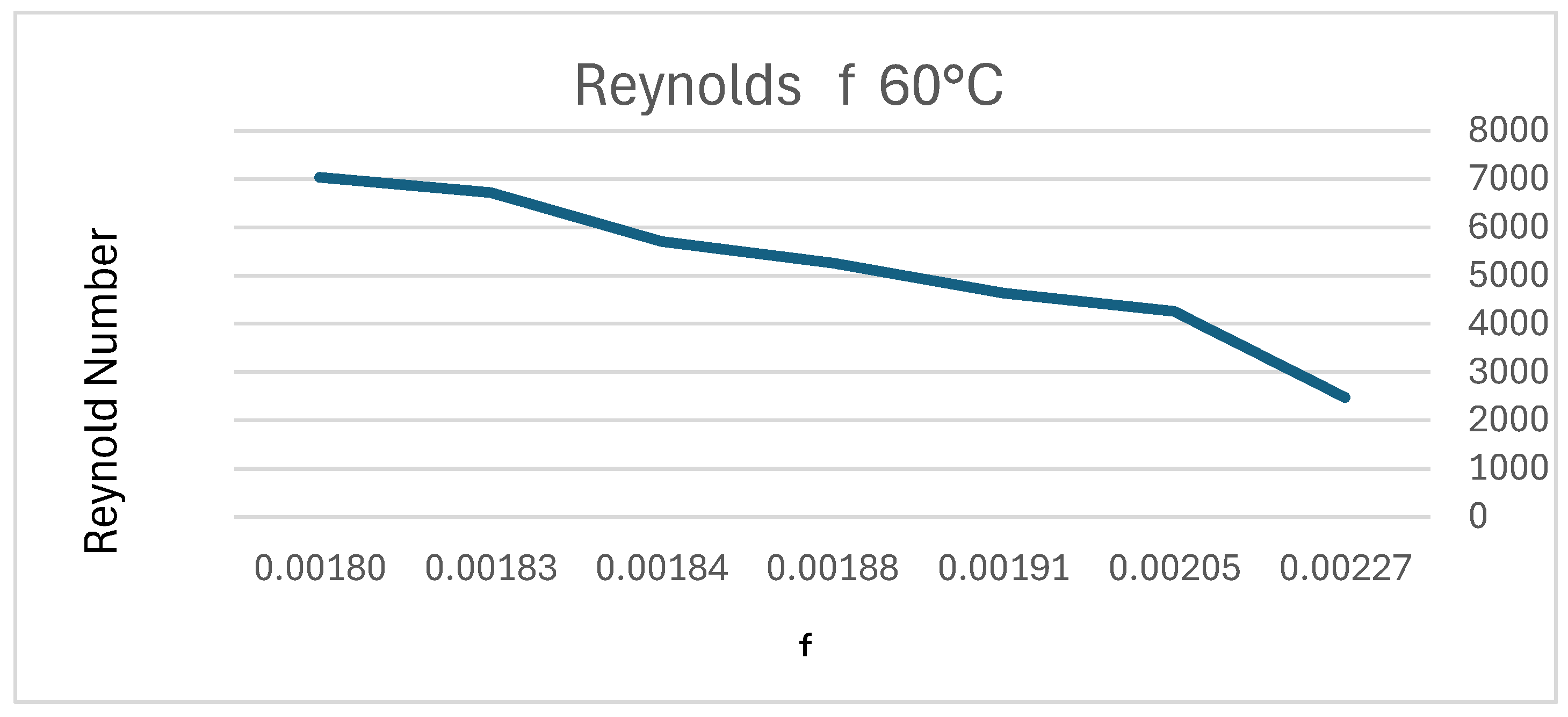

4.1.2. Friction Factor Characteristics (f–Re)

Following the evaluation of the heat transfer characteristics, the hydrodynamic behavior of the system was assessed through the friction factor–Reynolds (f–Re) relationship. Figure 6a,b show the variation of the friction factor for outlet temperatures of 54 °C and 60 °C, respectively. In both cases, the friction factor decreases monotonically with increasing Reynolds number, which is fully consistent with the classical behavior of fully developed turbulent flow in roughened or baffled ducts.

Figure 6.

a. Variation of friction factor with Reynolds number at 54 °C outlet temperature.

Figure 6.

a. Variation of friction factor with Reynolds number at 54 °C outlet temperature.

Figure 6.

b. Variation of friction factor with Reynolds number at 60 °C outlet temperature.

Figure 6.

b. Variation of friction factor with Reynolds number at 60 °C outlet temperature.

This trend confirms that, unlike heat transfer—which is strongly influenced by boundary layer disruption—the hydraulic response is predominantly governed by the inertial characteristics of the flow. Accordingly, the empirical correlation derived from the experimental dataset (previously presented as Equation (7)) is expressed as:

The proposed model demonstrates near perfect agreement with the measurements, yielding R² ≈ 1.000 and MAPE ≈ 0%, ndicating that global hydraulic losses are largely independent of the baffle inclination angle. This is an expected and significant result that can be explained by the fundamental fluid dynamics of the system;

Global Losses Dominate: The total pressure drop across the SAH duct is primarily determined by the inherent frictional resistance of the channel walls and the minor losses associated with the fixed entrance and exit geometries. The global flow structure is thus governed by the Reynolds number.

Localized Effect: The core function of adjusting the baffle angle is to intensify turbulence and disrupt the boundary layer locally, particularly close to the absorber plate. While this dramatically enhances heat transfer (Nu), the resulting increase in local pressure loss due to the redirection of flow is secondary and marginal when measured against the total frictional resistance of the entire duct

Design Advantage: This finding confirms that varying the baffle angle provides a high degree of thermal control (Nu) while imposing negligible additional hydraulic penalty (auxiliary fan power demand) across the tested angular range, thereby solidifying the thermodynamic advantage of the proposed active control system.

Minor deviations observed at lower Reynolds numbers are attributed to transitional flow features and sensor sensitivity in the wake regions formed behind the baffle elements. Nevertheless, the overall consistency of the experimental data confirms that the Re–fcorrelation provides a reliable hydrodynamic representation of the adjustable baffle SAH channel.

4.1.3. Correlation Reliability and Uncertainty

The experimentally measured Nusselt (Nu) and friction factor (f) data were systematically cross checked against the proposed empirical correlations. The angular exponents obtained from regression analysis—n = +0.2464 for 54 °C and n = –0.1220 for 60 °C confirm that baffle inclination enhances convective heat transfer at moderate angles (15°–45°), while at higher temperatures and Reynolds numbers the turbulence field reaches a saturation state, reducing the marginal benefit of increasing the angle beyond 60°. A combined uncertainty evaluation for both operating temperatures (54 °C and 60 °C), performed using the Kline–McClintock method, yielded an overall mass flow rate uncertainty of 3.33% (±0.00027 kg s⁻¹). The main contributing uncertainty components were:

Heat transfer rate (air) 3.008%

Solar irradiance (I) : 2.0%

Energy efficiency ( ηen) : 3.612%

Exergy efficiency (ηex : 4.144%

All measurement devices were factory calibrated, and only quasi steady data were used in the analysis. The total combined uncertainties remained within ±5%, which aligns well with uncertainty limits commonly reported for roughened duct and baffled SAH systems in the literature. Overall, the close agreement between the experimental dataset and the proposed Nu–Re–θ and f–Re correlations demonstrates their statistical robustness and physical consistency. These results confirm that the thermo-hydraulic behavior of the system was accurately captured and that the developed correlations can be reliably used for design, optimization, and performance prediction of similar solar air heater configurations.

4.2. Energy, Exergy, and Sustainability Performance

4.2.1. Energy Performance

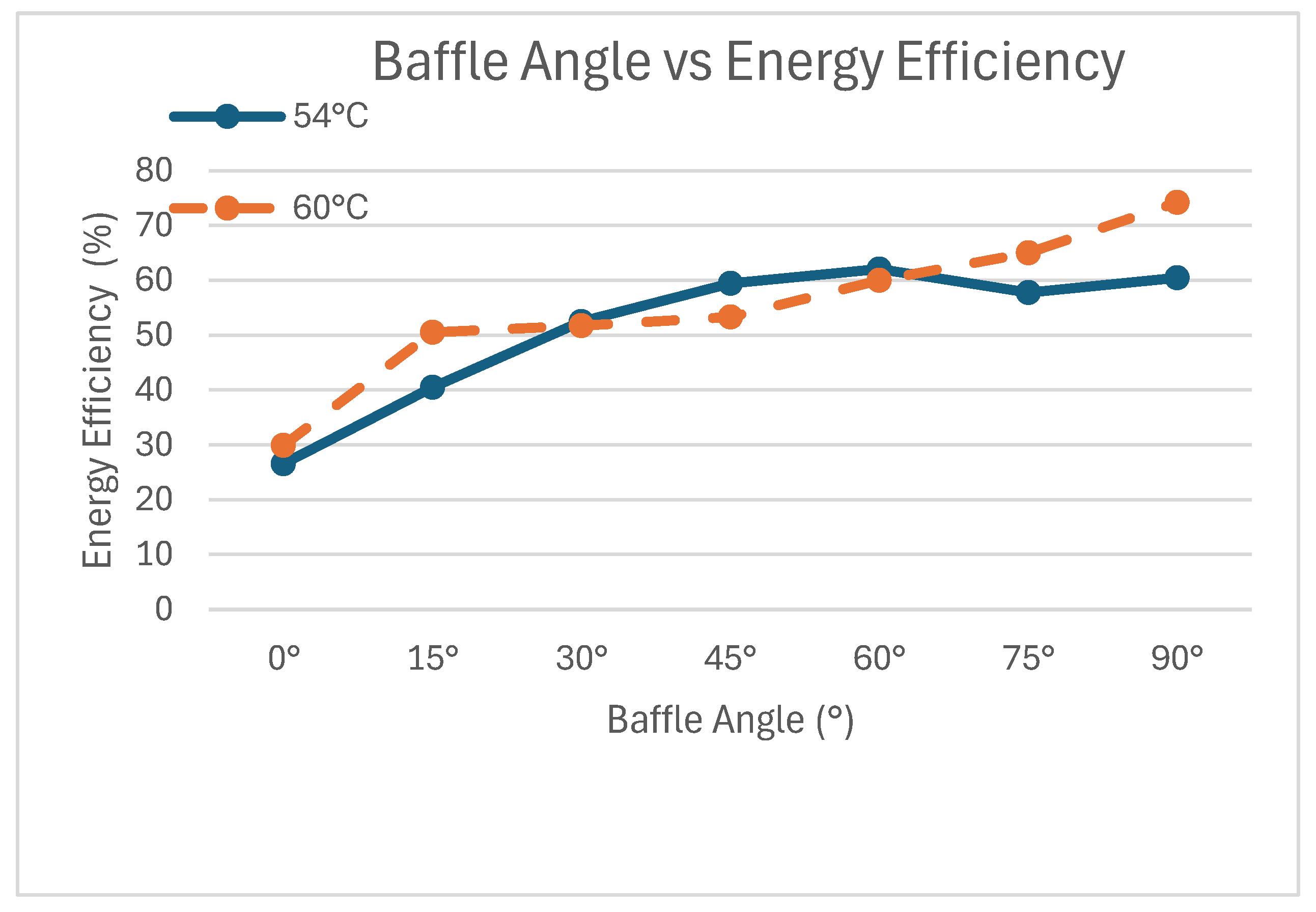

Increasing the baffle inclination produced a clear enhancement in energy efficiency at both outlet temperatures (54 °C and 60 °C). This improvement results from stronger turbulence, boundary layer disruption, and intensified mixing near the absorber surface as the inclination angle increases. The corresponding trends are shown in

Figure 7.

For the 54 °C condition, the energy efficiency rose from 27.5% at 0° to approximately 62–63% at 60°. A pronounced performance jump was observed between 15° and 45°, indicating a transition region where turbulent structures become significantly stronger. Beyond 60°, the rate of improvement diminished, suggesting that the flow approaches a partially saturated turbulent regime.

At 60 °C, the efficiency values were consistently higher, increasing from 30.96% at 0° to 76.83% at 90°. A plateau of roughly 52–55% emerged between 15° and 45°, reflecting a more stabilized flow regime driven by the higher absorber surface temperature. Overall, these patterns align well with previous findings indicating that intermediate baffle inclinations (30–60°) provide the most favorable conditions for effective heat transfer enhancement.

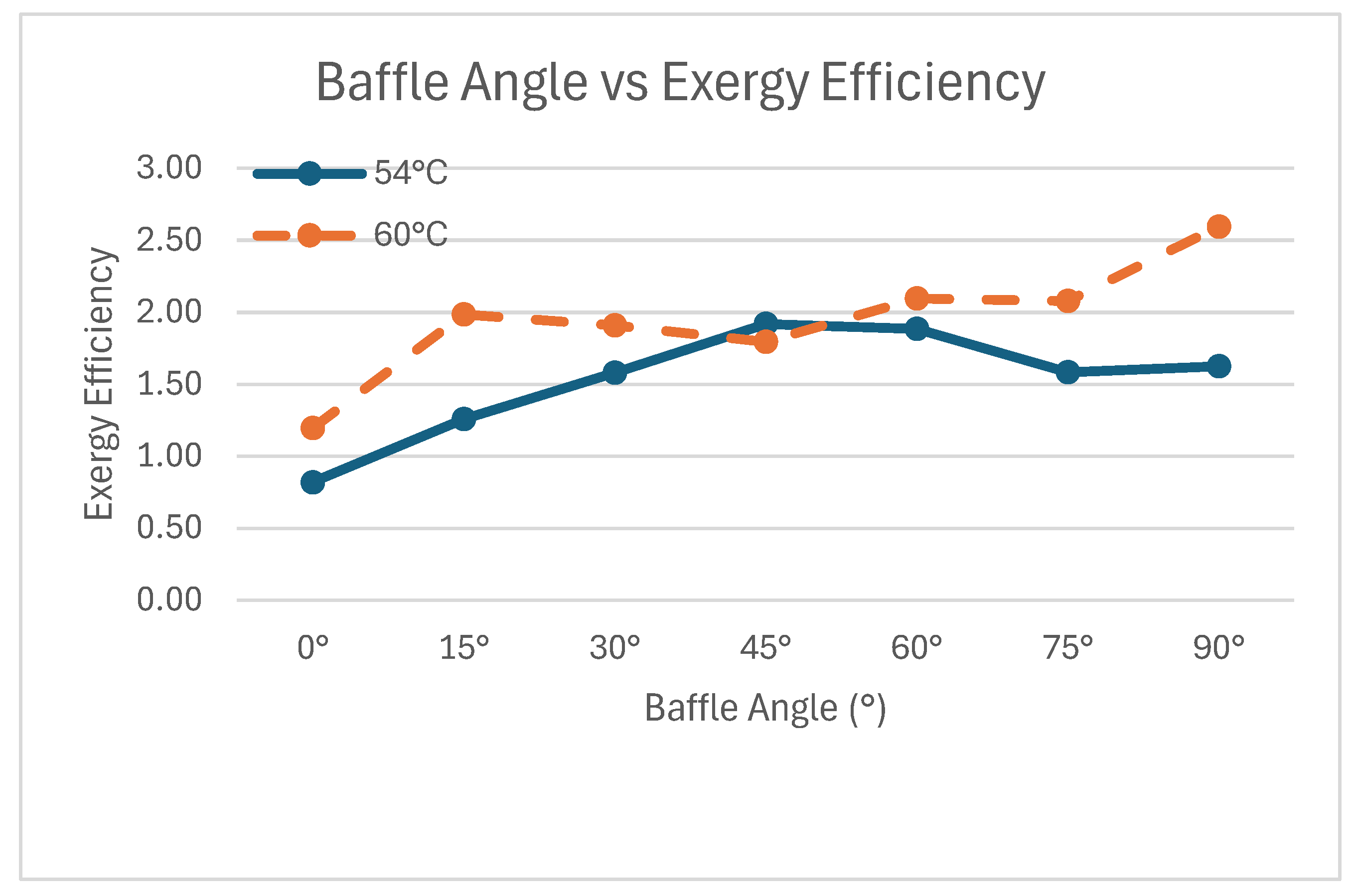

4.2.2. Exergy Efficiency

Exergy efficiency (

) exhibits a fundamentally different trend compared with energy efficiency, as it is directly linked to heat quality and thermodynamic irreversibilities. The influence of baffle inclination on

is noticeable but limited, reflecting the inherent difficulty of converting solar exergy into useful thermal exergy in the air stream. These variations are summarized in

Figure 8.

At 54 °C, remained between 1.30% and 1.99%, with only modest sensitivity to inclination angle. The relatively small temperature difference restricts the useful work potential, reducing the magnitude of the exergy term (At 60 °C, exergy efficiency ranged from 1.24% to 2.69%, reaching its maximum at 90°. Two mechanisms drive this improvement:

(i) the higher outlet temperature strengthens thermal quality, and

(ii) steeper baffle angles induce stronger turbulence and more effective convective transport.

Despite these improvements, the absolute value remains low. This outcome is expected because a solar air heater inherently converts high grade solar exergy into low grade thermal exergy, resulting in substantial thermodynamic irreversibility. The observed behavior is consistent with earlier studies on V shaped, perforated, and multi row baffles.

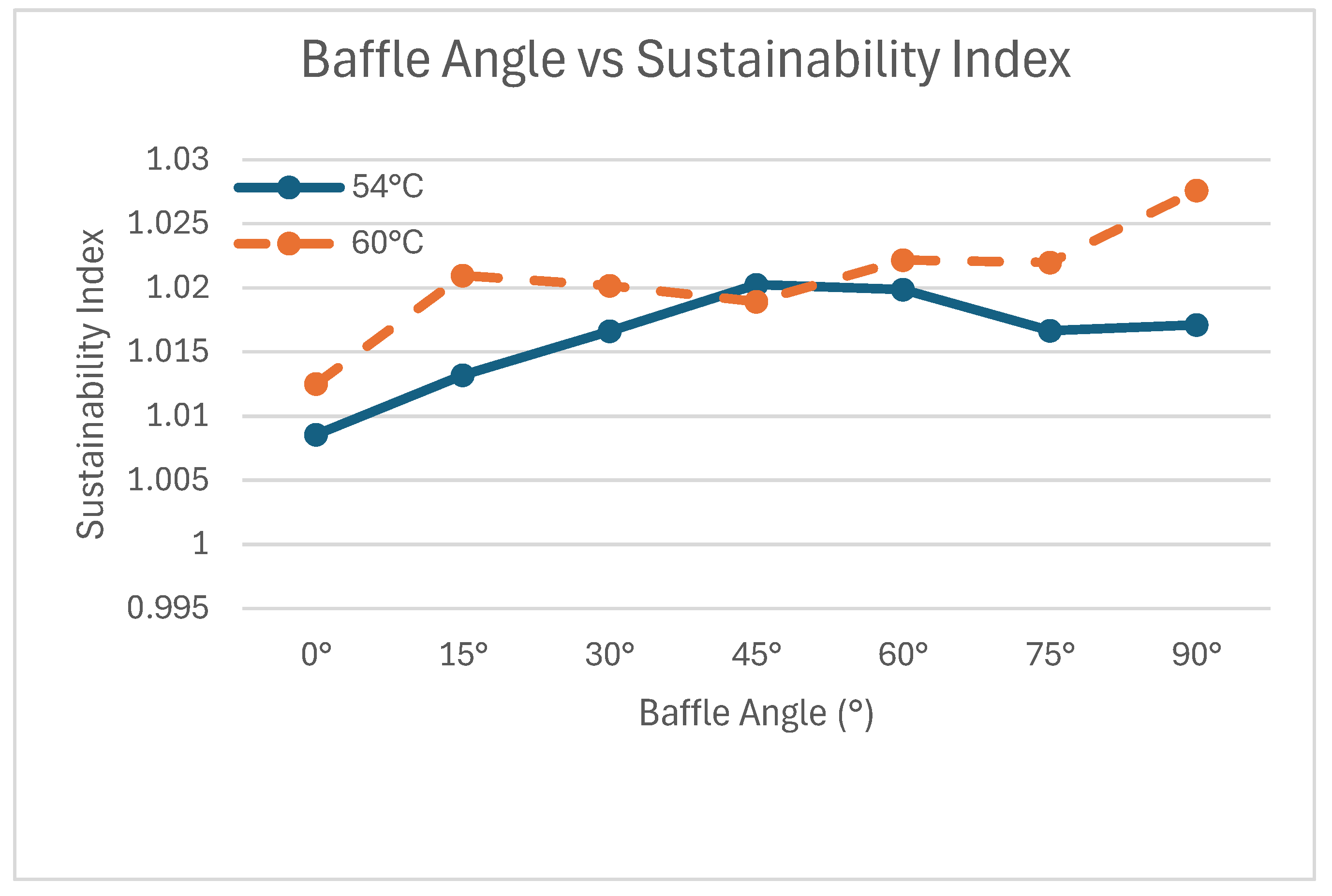

4.2.3. Sustainability Index

The Sustainability Index (SI) shows a very narrow range of values—1.001 to 1.002—across all baffle inclinations, indicating that most of the available exergy is destroyed during the process. This weak sensitivity to angle highlights the dominant influence of thermodynamic irreversibility within the SAH. The observed trends are shown in

Figure 9.

Although higher baffle angles slightly increase exergy efficiency, the corresponding increases in:

substantially offset any thermodynamic gains. As a result, SI remains nearly constant and is governed more by the auxiliary power requirement than by geometric variations. These findings agree with previous research involving V shaped, perforated, and multi row baffle systems, which similarly report that the inclination angle is the most influential geometric parameter affecting flow development, exergy loss, and overall sustainability. For practical applications, the 60–75° range offers the most balanced combination of heat transfer enhancement, exergy performance, and hydraulic penalty.

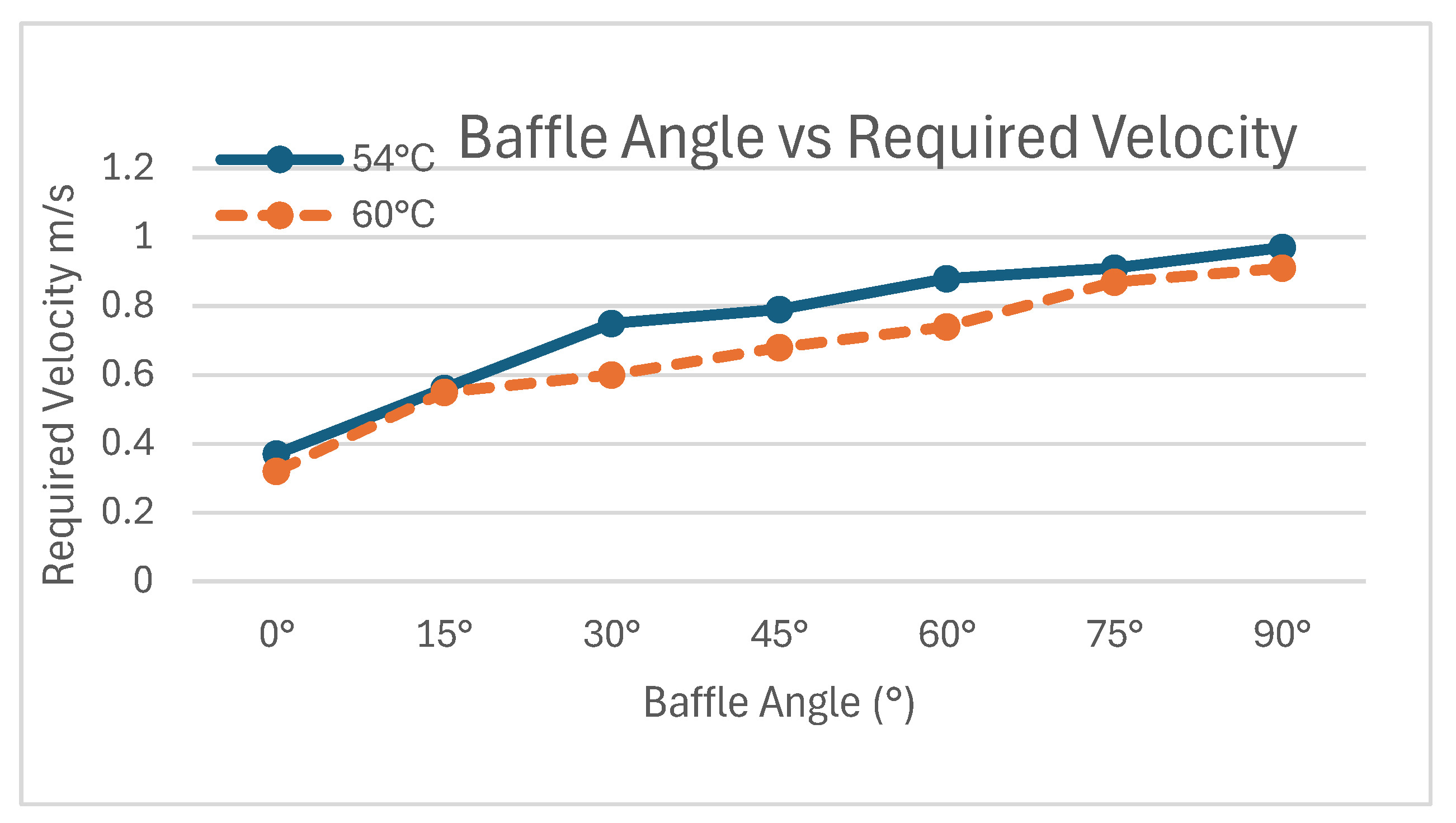

4.3. Empirical Model for Required Airflow Velocity

The effect of baffle inclination on the airflow demand required to maintain the target outlet temperatures was evaluated under an average solar irradiance of 850 W/m². As the inclination angle increases, both turbulence intensity and hydraulic resistance rise, necessitating higher airflow velocities to sustain the desired thermal output. Accordingly, for the 54 °C set point, the required inlet velocity increases from 0,37 m/s at 0° to 0,97 m/s at 90°. For 60 °C, the corresponding values range from 0,32 m/s to 0,91 m/s. This behavior results from two coupled mechanisms:

(i) stronger boundary layer disruption and enhanced mixing at larger angles, and (ii) a reduction in the effective flow cross section accompanied by intensified recirculation zones, which increases pressure losses and fan power demand.

The angular variation of the required airflow velocity reflects these interacting effects with a clear, nearly linear upward trend, as shown in

Figure 10. This response captures the combined influence of geometric constriction and turbulence induced mixing on the downstream flow field. Additionally, slightly lower velocities being sufficient at 60 °C arise from the higher absorber plate temperature (

), which strengthens buoyancy assisted convection and aids heat transfer, thereby reducing the mechanical airflow requirement.

To quantify the relationship between baffle inclination and the airflow required to sustain the target outlet temperatures, a multiple linear regression model was developed. The model predicts the inlet air velocity (

as a function of the baffle angle (

), absorber plate temperature (

), and outlet air temperature (

):

The coefficients exhibit clear physical meaning. Increasing the baffle angle ( ↑) requires higher airflow velocity because the associated geometric constriction and intensified recirculation zones increase hydraulic resistance. A higher absorber plate temperature ( ↑ ) reduces the required velocity, as buoyancy assisted convection strengthens natural driving forces within the channel. Conversely, higher outlet temperature targets (↑ ) demand greater heat input, which necessitates increased airflow.

From an engineering standpoint, these results confirm that baffle inclination is the dominant geometric parameter governing the trade off between thermal enhancement and pressure drop penalty. The regression analysis and experimental observations consistently indicate that the 60°–75° range offers the most effective balance—providing substantial heat transfer benefits while limiting auxiliary fan power consumption.

4.4. Design Synthesis and Long-Term Impact

The long-term performance of the PLC controlled solar air heater (SAH) was assessed by integrating experimentally measured thermal efficiencies with regional solar irradiance data. As summarized in

Table 3, the system provides 1025.9 kWh·year⁻¹ of useful heat at a 54 °C outlet temperature and 1087.2 kWh·year⁻¹ at 60 °C, based on an annual solar resource of 1311 kWh·m⁻² for the Manisa region. Over a 20-year operational lifetime, this corresponds to a cumulative thermal output of 20.5–21.7 MWh, indicating that a single collector can reliably support long term low temperature heating demands such as agricultural drying.

The environmental assessment further shows that the system mitigates 8.90–9.45 tons of CO₂ emissions over its lifetime, assuming displacement of electric heating using the national grid emission factor (0.434 kg CO₂·kWh⁻¹). Although the instantaneous thermal efficiencies are moderate, the cumulative CO₂ avoidance demonstrates that the SAH provides continuous environmental benefits due to its passive solar nature and minimal operational emissions.

From an engineering perspective, the 60°–75° baffle inclination range emerges as the most practical operating window, offering the best compromise between enhanced heat transfer performance and increased hydraulic resistance. This balance aligns with sustainability objectives, ensuring strong thermal performance without excessive auxiliary energy consumption.

A preliminary life cycle evaluation also supports the system’s environmental viability. Considering typical embodied carbon values for galvanized steel and tempered glass, the estimated manufacturing footprint is compensated within 1.5–2.0 years, meaning that nearly 90% of the system’s service life yields net environmental gains. From an economic standpoint, the annual useful heat production corresponds to approximately 4.8–5.0% of the system’s capital cost, resulting in a payback period of 6–8 years, depending on operating temperature and fan power requirements. These findings demonstrate that the proposed PLC controlled SAH delivers not only thermal and exergy benefits but also long term environmental and economic feasibility, making it a strong candidate for sustainable agricultural and industrial drying applications.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive 3E (energy–exergy–environmental) evaluation and design synthesis of a PLC-controlled solar air heater (SAH) equipped with dynamically adjustable baffle geometry. The adaptive control mechanism successfully maintained outlet temperatures of 54 °C and 60 °C with rapid stabilization (3–10 s), demonstrating a clear performance advantage over conventional passive SAH configurations.

Increasing the baffle inclination significantly enhanced convective heat transfer, with thermal efficiency rising from 27.5% at 0° to 76.8% at 90°. Despite this improvement, the friction factor remained predominantly governed by Reynolds number and showed minimal sensitivity to baffle angle, indicating that hydraulic losses are driven by global flow behavior rather than local geometric adjustments. Exergy efficiency remained modest (1.24–2.69%), and the Sustainability Index displayed limited variation (SI ≈ 1.001–1.002), reflecting inherent thermodynamic irreversibilities and fan-power-related mechanical exergy losses. Overall, the 60°–75° inclination range emerged as the most balanced operating window.

The findings align with earlier studies showing that multi-V ribs, perforated ribs, and other turbulence-promoting geometries significantly enhance thermo-hydraulic performance by promoting stronger recirculation and secondary flows [

37,

38]. However, literature also reports that excessive blockage or improper open-area ratios can increase pressure penalties and reduce overall THPP, reinforcing the need for optimized, adaptable geometries—an ability uniquely provided by the adjustable baffle mechanism used in this work.

A regression-based airflow velocity model was developed to support fan-speed optimization. Long-term analysis indicates that the proposed SAH delivers 20–22 MWh of useful heat and prevents approximately 9 tons of CO₂ emissions over its 20-year lifetime, confirming its environmental viability for low-temperature applications such as agricultural drying. Future research may focus on life-cycle optimization, advanced working fluids (nanofluids, PCMs), and machine-learning-based predictive control strategies to further enhance performance at intermediate inclination angles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Adjustable baffle mechanism (detail view), Figure S2: Collector cross-section and measurement layout, Figure S3: PLC control interface and program flow, Figure S4: Motor–shaft assembly, Figure S5: Pump and hydraulic system, Figure S6–S8: Experimental setup (front, side, and rear views), Table S1: Full experimental dataset (Excel file). Supplementary File Package: Supplementary_Package.zip.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision, and project administration: A.B. Aksoy. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Manisa Celal Bayar University (MCBU BAP) and by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).The APC was funded by the author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study, including raw experimental measurements, PLC control logs, and processed performance indicators, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the research support provided by Manisa Celal Bayar University (MCBU BAP) and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Tür-kiye (TÜBİTAK). During the preparation of this manuscript, ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1) and DeepL were used solely for language polishing and translation purposes. All scientific content, analyses, and interpretations were entirely produced and verified by the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Nomenclature

| Symbol |

Description |

Unit |

|

|

|

|

Solar irradiance |

W/m² |

|

Air density |

kg/m³ |

|

Collector surface area |

m² |

|

Dynamic viscosity |

Pa·s |

|

Heat transfer rate |

W |

|

Hydraulic diameter |

m |

|

Mass flow rate |

kg/s |

|

Convective heat transfer coefficient |

W/(m²·K) |

|

Specific heat of air |

J/(kg·K) |

|

Thermal conductivity of air |

W/(m·K) |

|

Ambient temperature |

K |

|

Nusselt number |

- |

|

Inlet air temperature |

K |

|

Reynolds number |

- |

|

Outlet air temperature |

K |

|

Friction factor |

- |

|

Plate temperature |

K |

|

Transmittance of glazing |

- |

|

Air velocity |

m/s |

|

Absorptance of absorber plate |

- |

|

Sustainability Index |

- |

|

Emissivity |

- |

|

Stefan–Boltzmann constant |

W/(m²·K⁴) |

|

|

|

References

- Fudholi, K. Sopian, A review of solar air flat plate collector for drying application, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 102 (2019) 333–345. [CrossRef]

- M. Bożym, A. Bok, Advantages and disadvantages of the solar drying of sewage sludge in Poland, Czas. Tech. 12 (2017). [CrossRef]

- L. Fernandes, P. B. Tavares, A Review on Solar Drying Devices: Heat Transfer, Air Movement and Type of Chambers, Solar 4(1) (2024). [CrossRef]

- H. Benli, Experimentally derived efficiency and exergy analysis of a new solar air heater having different surface shapes, Renew. Energy 50 (2013) 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Dhairiyasamy, R., Rajendran, S., Khan, S. A., Alahmadi, A. A., Alwetaishi, M., & Ağbulut, Ü. (2024). Enhancing thermal efficiency in flat plate solar collectors through internal barrier optimization. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 54, 102856. [CrossRef]

- Vengadesan, E., Arunkumar, T., Krishnamoorthi, T., & Senthil, S. (2024). Thermal performance improvement in solar air heating: an absorber with continuous and discrete tubular and v corrugated fins. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 48, 102416. [CrossRef]

- Jasim Mahmood, A. (2020). Thermal evaluation of a double-pass unglazed solar air heater with perforated plate and wire mesh layers. Sustainability, 12(9), 3619. [CrossRef]

- Acır A, Ata İ, Şahin İ. Energy and exergy analyses of a new solar air heater with circular type turbulators having different relief angles, Int J Exergy 20(1) (2016) 85 104. [CrossRef]

- Y. Alaiwi, T. Ahmed, Solar Air Heaters Classifications and Enhancement: A Review, Babylon. J. Mech. Eng. (2024) 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Daliran, Y. Ajabshirchi, Theoretical and experimental research on effect of fins attachment on operating parameters and thermal efficiency of solar air collectors, Inf. Process. Agric. 5(4) (2018) 411–421. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y. Optimization analysis of the length of baffles for solar air heaters, Energy Sources A Recover Util Environ Eff. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, et al. Numerical study on the influence of baffle configuration in solar air heaters, Case Stud Therm Eng. 52 (2025) 103947. [CrossRef]

- QuanKun Z, et al. Performance study on a new solar air heater for space heating applications, AIP Adv. 14(12) (2024) 125314. [CrossRef]

- Mahanand, Y., & Senapati, J. R. (2021). thermo-hydraulic performance analysis of a solar air heater (SAH) with quarter circular ribs on the absorber plate: A comparative study. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 161, 106747. [CrossRef]

- Naphon, P., & Wongwises, S. (2006). A review of flow and heat transfer characteristics in curved tubes. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 10(5), 463 490. [CrossRef]

- Matheswaran, M.M., Arjunan, T.V. & Somasundaram, D. Analytical investigation of exergetic performance on jet impingement solar air heater with multiple arc protrusion obstacles. J Therm Anal Calorim 137, 253–266 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shadi, M., Davodabadi Farahani, S., & Hajizadeh Aghdam, A. (2020). Energy, exergy and economic analysis of solar air heaters with different roughness geometries. Journal of Solar Energy Research, 5(2), 390 399. doi. 10.22059/jser.2020.297646.1142.

- Alrashidi, A., Altohamy, A. A., Abdelrahman, M. A., & Elsemary, I. M. (2024). Energy and exergy experimental analysis for innovative finned plate solar air heater. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 59, 104570. [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, E. K., & Koçyiğit, F. (2010). Energy and exergy analysis of a new flat plate solar air heater having different obstacles on absorber plates. Applied energy, 87(11), 3438 3450. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A., Awasthi A., Singh T., Kumar R. Experimental investigation and optimization of potential parameters of discrete V down baffled solar thermal collector using hybrid Taguchi–TOPSIS method. Appl Therm Eng. 2022;209:118250. [CrossRef]

- Thao PB, Truyen DC, Phu NM. CFD analysis and Taguchi based optimization of the thermohydraulic performance of a solar air heater duct baffled on a back plate. Appl Sci. 2021;11(10):4645. [CrossRef]

- Nowzari R, Mirzaei N, Parham K. Selecting the optimal configuration for a solar air heater using the Grey–Taguchi method. Processes. 2020;8(3):317. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Guan L, Yang C, Ge P, Xia J. A novel optimal control method for building cooling water systems with variable speed condenser pumps and cooling tower fans. Buildings. 2025;15(19):580. [CrossRef]

- Gang, H., & Bing, L. (2016). Intelligent optimization of solar air heating system in large scale construction of and its application. Int J Smart Home, 10(8), 99 106. [CrossRef]

- Cui X, Kou Z, Qiao Y. Water level control system for solar water heating engineering based on PLC. In: 2019 IEEE 3rd Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC). IEEE; 2019. p.1625–1628. [CrossRef]

- Saini, S. K., & Saini, R. P. (2008). Development of correlations for Nusselt number and friction factor for solar air heater with roughened duct having arc shaped wire as artificial roughness. Solar Energy, 82(12), 1118 1130. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Bhagoria, J. L., & Sarviya, R. M. (2009). Heat transfer and friction correlations for artificially roughened solar air heater duct with discrete W shaped ribs. Energy Conversion and management, 50(8), 2106 2117. [CrossRef]

- Bejan A. Advanced engineering thermodynamics. 4th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

- Dincer I, Rosen MA. Exergy: energy, environment and sustainable development. 2nd ed. Oxford: Newnes; 2012.

- Reddy J, Das B, Negi S. Energy, exergy, and environmental (3E) analyses of reverse and cross corrugated trapezoidal solar air collectors: An experimental study, J Build Eng. 41 (2021) 102434. [CrossRef]

- Bahrehmand D, Ameri M, Gholampour MJ. Energy and exergy analysis of different solar air collector systems with forced convection, Renew Energy. 83 (2015) 1119 30. [CrossRef]

- Hassan A, Nikbakht AM, Fawzia S, Yarlagadda P, Karim A. A comprehensive review of the thermohydraulic improvement potentials in solar air heaters through an energy and exergy analysis, Energies. 17(7) (2024) 1526. [CrossRef]

- Cortes A, Piacentini R. Improvement of the efficiency of a bare solar collector by means of turbulence promoters, Appl Energy. 36(4) (1990) 253 61. [CrossRef]

- Gürel AE, Yıldız G, Ergün A, Ceylan İ. Exergetic, economic and environmental analysis of temperature controlled solar air heater system, Clean Eng Technol. 6 (2022) 100369. [CrossRef]

- Petela R. Exergy of undiluted thermal radiation, Solar Energy 74(6) (2003) 469 88. [CrossRef]

- TEİAŞ. (2023). Türkiye electricity generation carbon intensity report. Türkiye Elektrik İletim A.Ş. Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://www.teias.gov.tr/turkiye elektrik uretim iletim istatistikleri.

- Singh, V.P.; Jain, S.; Gupta, J.M.L. Analysis of the Effect of Variation in Open Area Ratio in Perforated Multi-V Rib Roughened Single-Pass Solar Air Heater—Part A. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2025, 47(2), 2029976. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.P.; Jain, S.; Karn, A.; Kumar, A.; Dwivedi, G.; Meena, C.S.; Ghosh, A. Recent Developments and Advancements in Solar Air Heaters: A Detailed Review. Sustainability 2022, 14(19), 12149. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).