Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Bearing Witness in the Anthropocene

1.1. Context of the Anthropocene

1.2. Spirituality in Healthcare in a Time of Crisis

2. Methodology: Integrating Lived Experience and Scholarly Inquiry

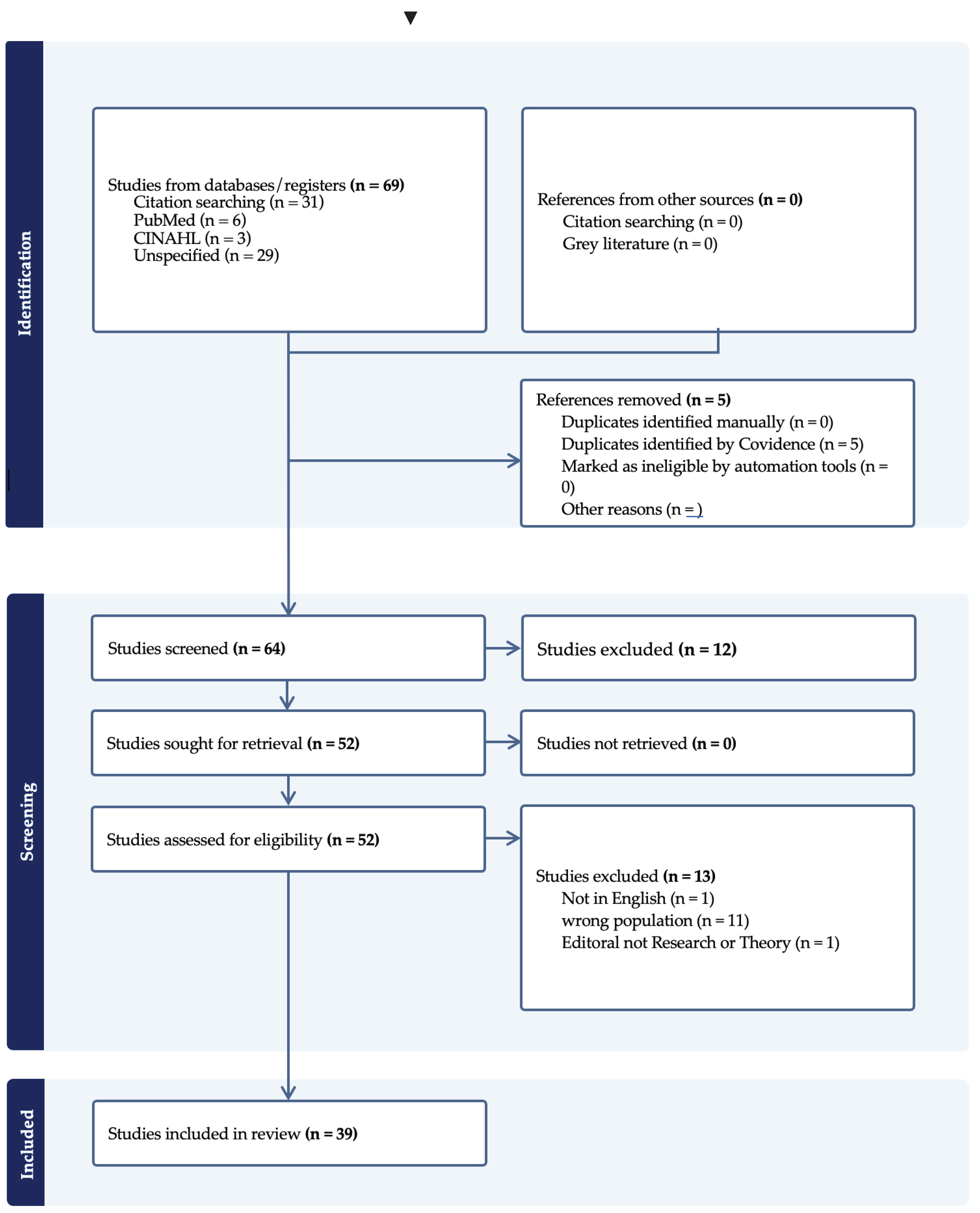

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

2.3. Personal Narrative

3. Personal Narrative

3.1. First Noticing the Ripples – Encounter with Radical Compassion

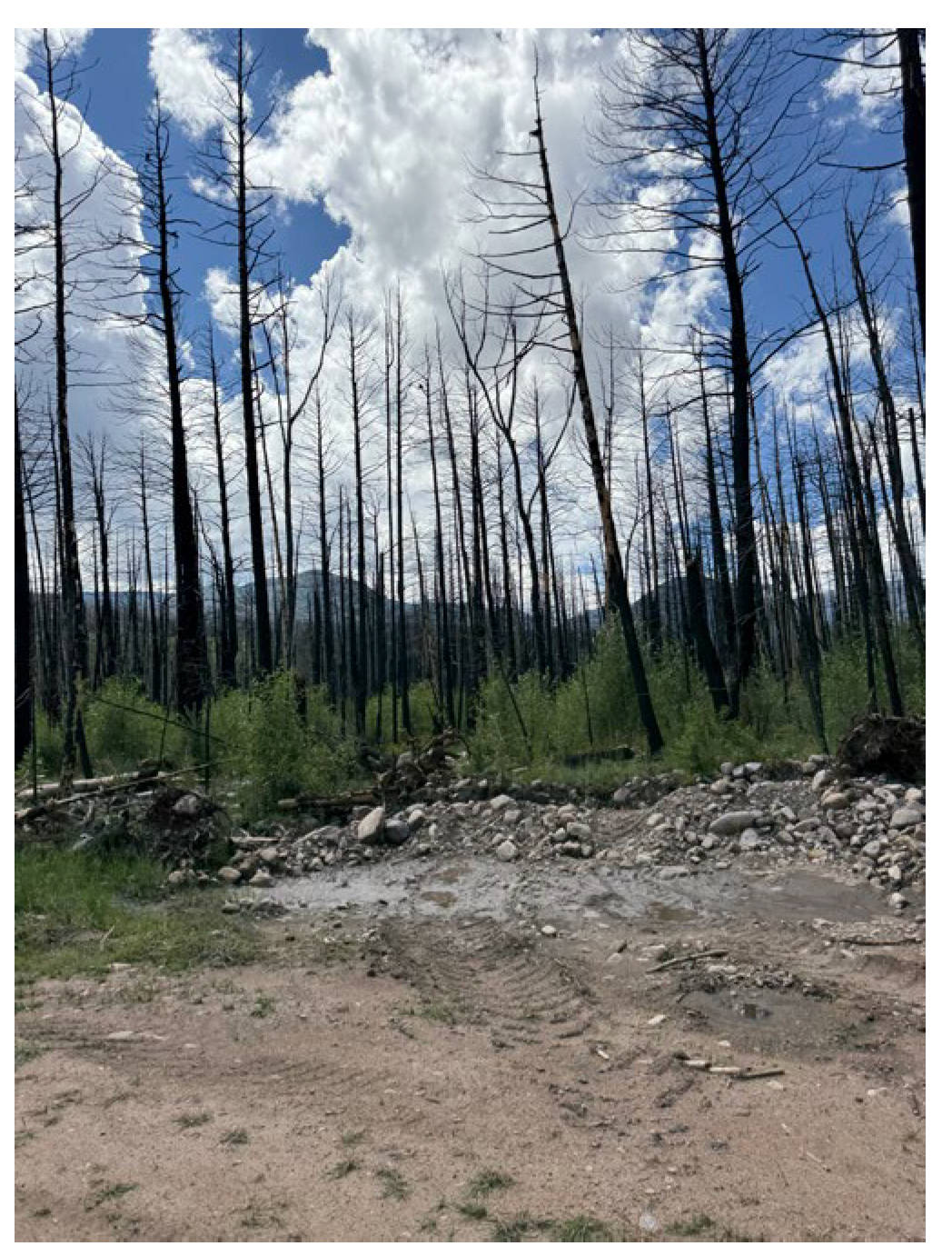

3.2. Transition to Academia and Environmental Awareness

3.3. Soto Zen Teaching on Interbeing and Remote Consequences

3.4. Contemplative Medicine and Nursing Practice

4. Results: Scoping Review

| Lead Author/ Year | Inclusion Criteria | Approach | Outcomes |

| Barbir, 2025 [23] | Studies on mindfulness and sustainability from Scopus database | Literature review | Conceptual framework linking mindfulness mediators to sustainability outcomes |

| Barrett, 2016 [24] | Adults interested in mindfulness and sustainability | Mindful Climate Action (MCA) program: 8-week course blending MBSR with climate/energy education, 2.5h weekly + retreat | Intended outcomes: ↓carbon footprint (transport, diet, purchasing, energy) and ↑health, well-being, self-efficacy |

| Bendell, 2021 [25] | Facilitated gatherings addressing societal disruption/collapse and adaptation | Deep Relating and facilitation practices (containment, uncertainty, emotions, othering) | Insights on effective facilitation for collapse-related dialogues |

| Billet, 2025 [26] | Peer-reviewed research on ecospirituality, nature as sacred | Narrative review | Synthesizes links between ecospirituality, pro-environmental attitudes, and well-being |

| Bock, 2024 [27] | Ecospiritual practice and climate action engagement | Ecospiritual praxis (conceptual cycle) | Framework to move from concern to action; connects religion/science for behavior change |

| Bryant, 2024 [28] | Local clergy engaged in disaster spiritual/emotional care | No experimental intervention (study focused on narrative documentation and reflection of real-world coping strategies and caregiving experiences | Identified coping strategies (psychological, social, religious) and contextual challenges |

| Budha, 2025 [29] | Indigenous community members with knowledge of ritual, agricultural, and spiritual practices | Not experimental; ethnographic documentation of rituals, weather forecasting, and farming practices | Identifies how shifting climes disrupt agricultural and ritual cycles; shows indigenous temporal concepts (nham = weather, sameu = time) as frameworks for interpreting climate change; highlights ecospiritual resilience and challenges in weather prediction |

| Cayir, 2022 [30] | Healthcare providers participating in simulation-based training | The Pause (brief contemplative practice) | There was a statistically significant effect on HRV. In the unadjusted model (model 1), participants in the intervention group had a post-Pause SDNN value of 56.0 (95% CI 47.0, 65.0) while those in the control group had 35.1 (95% CI 29.4, 40.8; p for difference <.001). When adjusting for baseline SDNN (model 2), participants in the intervention group had a post-Pause SDNN that was 11.8 (95% CI 2.7, 20.8; p =.01) points higher than those in the control group |

| Chavan, 2024 [31] | Participants in Ganesh idol immersion rituals | To examine the determinants of pro-environmental religious practices in the context of Ganesh idol immersion, focusing on the roles of religiosity, spirituality, and environmental consciousness | Positive relationship of spiritual values and environmental consciousness with pro-environmental practices; negative influence of spiritual belief |

| de Diego-Cordero, 2024 [32] | Empirical studies (2018–2023) in English/Spanish exploring ecospirituality and health | Systematic review | Ecospirituality linked with improved mental, physical, and global health |

| Fry, 2021 [33] | Leadership and sustainability scholarship | No direct Intervention, but the paper develops a new conceptual framework (global leadership for sustainability) integrating spiritual leadership principles, ethical principles for sustainability and a global mindset for fostering purpose. | Framework linking spirituality, ethics, and sustainability outcomes |

| Goralnik, 2020 [34] | Students engaged in sustainability curriculum with contemplative pedagogy | 5-minute pause integrated into sustainability teaching | Enhanced resilience, emotional intelligence, and engagement in sustainability issues |

| Hidayat, 2025 [16] | Interfaith volunteer organization engaged in fire mitigation | Faith-based fire prevention practices (wasathiyah and zhong yong principles) | Significant impact on efficiency in resource use, the formation of robust interfaith collaboration, and heightened ecological awareness within the community. Long-term implications for increasing resilience. |

| Ives, 2025 [16] | Studies and evidence on religion and climate change in cities | Religious-civic partnership model for climate action | Framework for engaging faith in urban climate adaptation and mitigation |

| Jadgal et al., 2024 [35] | Nursing students admitted before Sept 2022, willingness to participate | Questionnaires: demographic, environmental knowledge/attitude/behavior, environmental ethics, spiritual health. | Knowledge predicted environmental ethics. Environmental ethics and spiritual health were predictive of environmental protection behaviors. |

| Johnson, 2022 [36] | Indigenous-led perspectives on environmental governance and justice | Recognition and healing frameworks in planetary justice | Proposes planetary justice agenda grounded in Indigenous worldviews |

| Lee, 2015 [5] | Tzu-Chi organizational environmental initiatives published in 2 specified publications | Recycling practices, Buddhist environmental ethics | Religious environmentalism shaping climate discourse |

| Luetz, 2024 [37] | Studies and practices involving Indigenous worldviews, spirituality, and conservation | Not experimental; conceptual review of Indigenous ecotheology | Demonstrates that Indigenous ecotheology sustains biodiversity, conservation, and adaptation; critiques Western technocratic models; proposes inclusion of Indigenous spirituality as central to sustainability frameworks (e.g., SDGs, CBD, Earth Charter) |

| Maddrell, 2022 [38] | Participants in the annual Keeills prayer walks | Prayer walks, Celtic Christian spirituality | Bridging enchantment and eco-spirituality for environmental action |

| Markus, 2018 [39] | Buddhist perspectives on ecology and climate | Discussion of climate engineering proposals | Advocates ethical guidelines for geoengineering grounded in Buddhist values |

| Matthews, 2023 [40] | Indigenous-led initiatives on climate and health | Caring for Country practices, cultural revitalization | Highlights decolonization and Indigenous knowledge as vital for planetary health |

| Mayer, 2019 [41] | Responses to 'Laudato Si’ | Interdisciplinary analysis of Catholic environmental teaching | Integrates health, psychology, and theology perspectives on ecological crisis |

| Mohidem, 2023 [42] | Islamic scholarship on environment and health | Islamic principles: unity, balance, responsibility | Islamic framework for environmental health and sustainability |

| Mölkänen, 2025 [18] | Residents engaged with spirits/rituals in local ecologies | Not applicable | Religious/ritual practices shape conservation interactions; caution against dismissing lived religion |

| Mpofu, 2021 [43] | African perspectives on religion and climate change | Faith-based mission framing (healing, reconciliation, restoration) | Argues for extending liberation/restoration to human–nature relations |

| Oughton, 2016 [44] | Post-accident assessments and official reviews | Evacuation/remediation policies | Primary health effects were psychosocial; evacuation ethics were questioned; broader values were at stake |

| Pandya, 2021 [22] | Social workers working with environmental migrants | Not experimental; catalogues spiritually sensitive models/techniques | Regional and demographic differences in preferred models, assessments, techniques, and goals |

| Pike, 2024 [17] | Ritualized responses to climate/ecological grief | Rituals (funerals for extinct species, ceremonial fire, Red Rebel Brigade) | Rituals create sacred spaces, process grief, mobilize identity and care |

| Riordan, 2022 [45] | Adults eligible for Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR); meditation-naïve controls; long-term meditators | 8-week MBSR; structurally matched active control; waitlist | MBSR did not uniquely improve targets vs. active control; some gains vs. waitlist in PEB and sustainable well-being |

| Schmid, 2020 [46] | Involvement in community-based eco-social initiatives | Mind-body practices (meditation, yoga, reflection) within activism | Mindfulness underpins togetherness, resilience, and political/spatial praxis |

| Shahida, 2024 [47] | Enrollment in UG science; participation in a semi-structured interview | Not experimental; documents household-level rituals/values | Religious/spiritual teachings can scaffold eco-ethics and attitudinal shifts in education |

| Somarathne, 2025 [7] | Long-term meditators (more than 3 years of practice) | Vipassana meditation (natural practice, not experimental intervention | Associations between mindfulness facets, positive lifestyle habits, quality of life, and carbon footprint domains |

| Stahl, 2024 [21] | Individuals engaged in eco-ministry leadership training | Eco-ministry certification program with spiritual and environmental practices | Guidance for resilient leadership and eco-spiritual formation to address climate crisis challenges |

| Tarusarira, 2022 [19] | Indigenous religious leaders involved in conflict contexts | Not experimental; analysis of religious sensemaking practices | Sacred framing influenced conflict dynamics, intensity, and resolution strategies |

| Taylor, 2016 [48] | Studies on religion and environmental attitudes or practices | Literature review of evidence to determine if world religions are becoming more environmentally friendly | Mixed evidence: some religious groups foster pro-environmental behavior, others hinder; lack of quantitative data |

| van Vugt, 2019 [20] | Monastics engaged in debate training | Analytical meditation and monastic debate training | Enhanced reasoning, attention, working memory, emotion regulation, and social connectedness |

| Wamsler, 2017 [49] | Students enrolled in relevant Master’s programs | Learning lab on mindfulness integrated into coursework | Identified positive effects of mindfulness on sustainability attitudes, resilience, and education |

| Yamaguchi, 2024 [50] | Ethnographic studies on kokoro no kea after 2011 disaster | Kokoro no kea teams; informal social activities; spiritual/religious support | Mixed reception of kokoro no kea; importance of social bonds (kizuna); gendered impacts |

| Zielke, 2023 [6] | Members engaged in eco-activism | Meditation, politics of care, eco-activist practices | Reframed Buddhist practices as eco-activism, promoting care as a transformative tool |

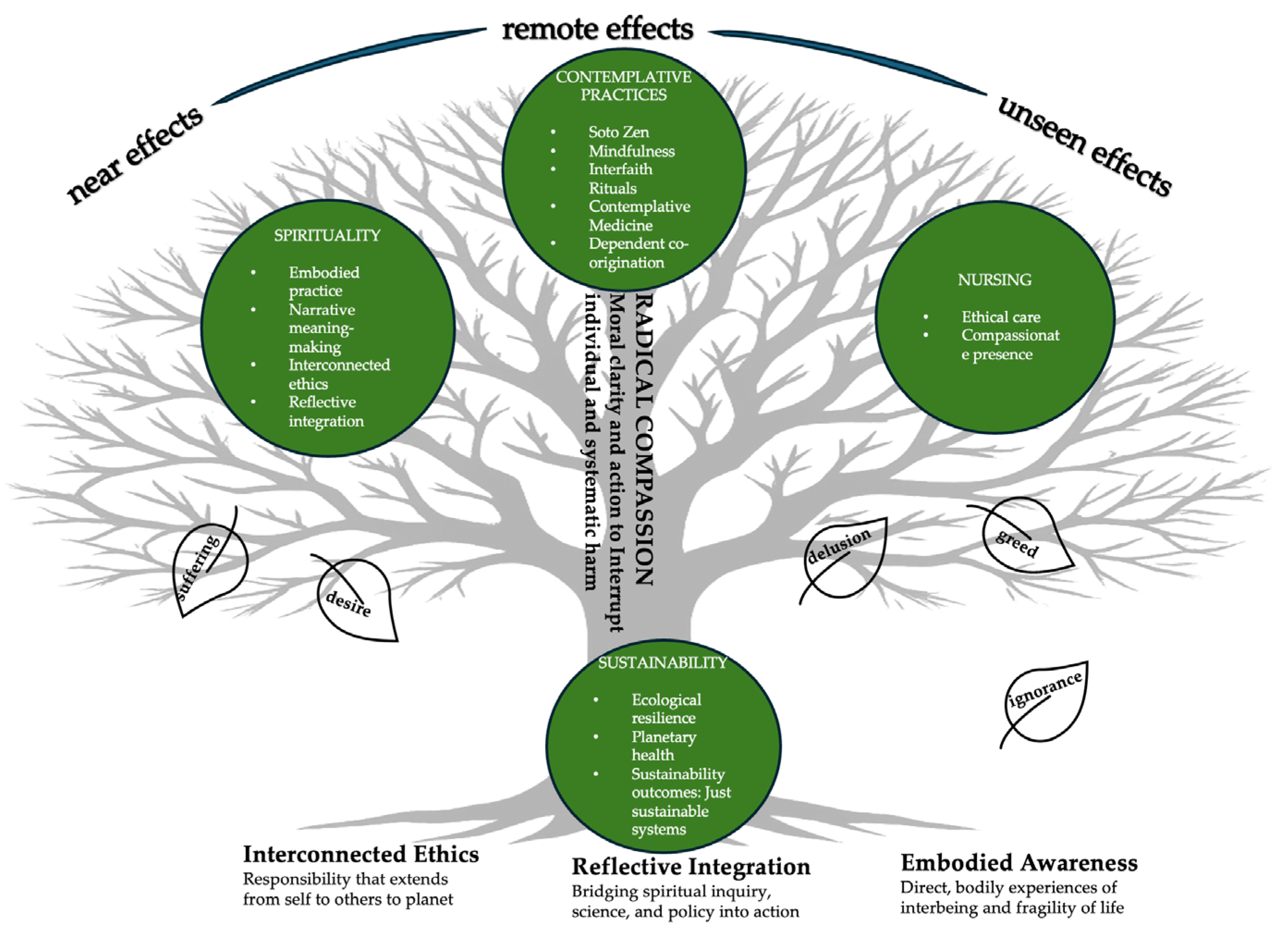

5. Discussion

5.1. Convergence of Personal Narrative and Scoping Review

5.2. Contemplative Practices as Ethical Compass

5.3. Spirituality as Catalyst for Planetary Health

6. Conclusions: A Path Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trischler, H. The Anthropocene. NTM Z. Für Gesch. Wiss. Tech. Med. 2016, 24, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbon, P.; Stoermer, E. The “Anthropocene. ” Glob. Change Newsl. 2000, 41, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hunnicutt, T.; Shakil, I.; Singh, K.; Singh, K. Trump Tells Pentagon to Resume Testing US Nuclear Weapons. Reuters 2025.

- Moura, A.T.; Coriolano, A.M.; Kobayasi, R.; Pessanha, S.; Cruz, H.L.; Melo, S.M.; Pecly, I.M.; Tempski, P.; Martins, M.A. Is There an Association among Spirituality, Resilience and Empathy in Medical Students? BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Han, L. Recycling Bodhisattva: The Tzu-Chi Movement’s Response to Global Climate Change. Soc. Compass 2015, 62, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielke, Z. Contesting Religious Boundaries with Care: Engaged Buddhism and Eco-Activism in the UK. Religions 2023, 14, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarathne, E.A.S.K.; Gunathunga, M.W.; Lokupitiya, E. How Does Meditation Relate to Quality of Life, Positive Lifestyle Habits and Carbon Footprint? Heliyon 2025, 11, e41144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contemplative Medicine Fellowship | New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care. Available online: https://www.zencare.org/contemplative-medicine-fellowship (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews: Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses 2017.

- Rodriguez, K.A.; Tarbox, J.; Tarbox, C. Compassion in Autism Services: A Preliminary Framework for Applied Behavior Analysis. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2023, 16, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, R. Available online:. Available online: https://curseofanurse.com/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Dōgen; Nearman, H. Shōbōgenzō. Vol. I : The Treasure House of the Eye of the True Teaching : A Trainee’s Translation of Great Master Dōgen’s Spiritual Masterpiece; Reformatted version.; Shasta Abbey Press: Mount Shasta, California., 2007; ISBN 978-0-930066-37-6.

- Dōgen; Nishijima, G.; Cross, C. Shōbōgenzō : The True Dharma-Eye Treasury. Vol. IV; BDK English Tripiṭaka.; 99-103; Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research: Berkeley, Calif., 2008; ISBN 978-1-886439-38-2.

- Sarao, K.T.S. The Dhammapada : A Translator’s Guide; Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers: New Delhi, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat, S.; Tanggok, M.I.; Ho, E. Interfaith Response to Fire Mitigation: Islamic and Confucian Perspectives in Addressing Climate Change in Indonesia. Rev. Relig. Chin. Soc. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.M. Ritual Responses to Environmental Apocalypse in Activist Communities. Arch. Psychol. Relig. 2024, 46, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölkänen, J. Living with Spirits and Environmental Conservation Efforts in Rural North-Eastern Madagascar. Approaching Relig. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarusarira, J. Religious Environmental Sensemaking in Climate-Induced Conflicts. Religions 2022, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, M.K.; Moye, A.; Pollock, J.; Johnson, B.; Bonn-Miller, M.O.; Gyatso, K.; Thakchoe, J.; Phuntsok, L.; Norbu, N.; Tenzin, L.; et al. Tibetan Buddhist Monastic Debate: Psychological and Neuroscientific Analysis of a Reasoning-Based Analytical Meditation Practice. Prog. Brain Res. 2019, 244, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W.J. Meaningful Vocation in a Climate-Changed World: Learnings from Seminary of the Wild. Relig. Educ. 2024, 119, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, S. Social Work with Environmental Migrants: Exploring the Scope for Spiritually Sensitive Practice. Soc. Work 2021, 66, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbir, J.; Baars, C.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Sharifi, A.; Demarzo, M.; Filho, W.L. Observing Sustainability through the Mindfulness Lens: A Conceptual Framework Based on a Bibliometric Review Analysis. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.; Grabow, M.; Middlecamp, C.; Mooney, M.; Checovich, M.; Converse, A.; Gillespie, B.; Yates, J. Mindful Climate Action: Health and Environmental Co-Benefits from Mindfulness-Based Behavioral Training. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J.; Carr, K. Group Facilitation on Societal Disruption and Collapse: Insights from Deep Adaptation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billet, M.I.; Baimel, A.; Schaller, M.; Norenzayan, A. Ecospirituality. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2025, 34, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C. Ecospiritual Praxis: Cultivating Connection to Address the Climate Crisis. Religions 2024, 15, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.; Nyhof, M.; Hassler, M.W.; Abe, J.; Vives De León, A. Spiritual and Emotional Care Among Clergy as First Responder-Victims in Puerto Rico: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study. J. Relig. Health 2024, 63, 4580–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budha, J.B.; Daurio, M.; Turin, M. Climing Up, Thinking With, Feeling Through: Ritual, Spirituality and Ecoscience in Northwestern Nepal. Religions 2025, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayir, E.; Cunningham, T.; Ackard, R.; Haizlip, J.; Logan, J.; Yan, G. The Effects of the Medical Pause on Physiological Stress Markers among Health Care Providers: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavan, P.; Sharma, A. Religiosity, Spirituality or Environmental Consciousness? Analysing Determinants of Pro-Environmental Religious Practices. J. Hum. Values 2024, 30, 160–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Diego-Cordero, R.; Martínez-Herrera, A.; Coheña-Jiménez, M.; Lucchetti, G.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.M. Ecospirituality and Health: A Systematic Review. J. Relig. Health 2024, 63, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, L.W.; Egel, E. Global Leadership for Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralnik, L.; Marcus, S. Resilient Learners, Learning Resilience: Contemplative Practice in the Sustainability Classroom. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2020, 2020, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed Jadgal, M.; Bamri, A.; Ardakani, M.F.; Jadgal, N.; Zareipour, M. Investigation of Environmental Ethics, Spiritual Health, and Its Relationship with Environmental Protection Behaviors in Nursing Students. Investig. Amp Educ. En Enfermeria 2024, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.; Sigona, A. Planetary Justice and ‘Healing’ in the Anthropocene. Earth Syst. Gov. 2022, 11, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, J.M. Can Indigenous Ecotheology Save the World? Affinities between Traditional Worldviews and Environmental Sustainability. Clim. Dev. 2024, 16, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddrell, A. ‘It Was Magical’: Intersections of Pilgrimage, Nature, Gender and Enchantment as a Potential Bridge to Environmental Action in the Anthropocene. Religions 2022, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, T.; Vivekānanda, B.; Lawrence, M. An Assessment of Climate Engineering from a Buddhist Perspective. J. Study Relig. Nat. Cult. 2018, 12, 8–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, V.; Vine, K.; Atkinson, A.-R.; Longman, J.; Lee, G.W.; Vardoulakis, S.; Mohamed, J. Justice, Culture, and Relationships: Australian Indigenous Prescription for Planetary Health. Science 2023, 381, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.-H.; George, W.M.; Nass, E. “Care for the Common Home”: Responses to Pope Francis’s Encyclical Letter. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohidem, N.A.; Hashim, Z. Integrating Environment with Health: An Islamic Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, B. Pursuing Fullness of Life through Harmony with Nature: Towards an African Response to Environmental Destruction and Climate Change in Southern Africa. HTS Teol. Stud. Theol. Stud. 2021, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oughton, D. Societal and Ethical Aspects of the Fukushima Accident. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2016, 12, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, K.M.; MacCoon, D.G.; Barrett, B.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Chungyalpa, D.; Lam, S.U.; Davidson, R.J.; Goldberg, S.B. Does Meditation Training Promote Pro-Environmental Behavior? A Cross-Sectional Comparison and a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, B.; Taylor Aiken, G. Transformative Mindfulness: The Role of Mind-Body Practices in Community-Based Activism. Cult. Geogr. 2020, 28, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahida From Micro-Rituals to Macro-Impacts: Mapping Eco-Ethics via Religious/Spiritual Teachings into Higher Education. Ethics Educ. 2024, 19, 233–254. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Van Wieren, G.; Zaleha, B. The Greening of Religion Hypothesis (Part Two): Assessing the Data from Lynn White, Jr, to Pope Francis. J. Study Relig. Nat. Cult. 2016, 10, 306–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brossmann, J.; Hendersson, H.; Kristjansdottir, R.; McDonald, C.; Scarampi, P. Mindfulness in Sustainability Science, Practice, and Teaching. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 13, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S. The Faultline of Kokoro No Kea: Mental Distress and Post-Disaster Psychosocial Care After the Great East Japan Earthquake. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2025, 29, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Three Refuges | Three Collective Pure Precepts | Ten Great Precepts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).