2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This quantitative, cross-sectional study was conducted between March and July 2025 in rural communities of Vukovar-Srijem County, Croatia. To reduce anxiety and increase the comfort of respondents, data were collected in participants’ private homes, an approach previously shown to enhance the reliability of cognitive testing in familiar environments [

25].

2.2. Participants

The study included older adults aged 65 years and above residing in rural areas who were able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were age below 65 years, residence in urban communities, and living in institutionalized care facilities.

A non-probabilistic snowball sampling method was used to recruit 265 participants who met the inclusion criteria. The estimated sampling error was 6% with a 95% confidence interval, calculated using an online sample size calculator [

26]. Each participant was encouraged to identify other potential respondents meeting the inclusion criteria, which allowed the recruitment of individuals who might otherwise be difficult to reach, as a part of snowball sampling [

27].

2.3. Instruments

The study employed three instruments: the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and a questionnaire collecting general and sociodemographic information (age, sex, marital status, place of residence, educational attainment, number of children and grandchildren). Participants completed the questionnaire using the paper-and-pencil method.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment, covering multiple cognitive domains, including executive functions, language, attention and concentration, conceptual thinking, calculation, orientation, memory, and visuoconstructive abilities. The total possible score is 30, with scores of 26 or above considered normal [

28]. Training for the administration and interpretation of MoCA was completed online for the purposes of this study. The Croatian version was translated by Dr. I. Martinić Popović and used with the permission of the original author, Dr. Ziad Nasreddine. The internal consistency of MoCA in this study was 0.766.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) consists of 12 items assessing perceived social support across three domains: family, friends, and significant others, with four items per domain. Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). Subscale scores (family, friends, significant others) and the total score are calculated by averaging the relevant items. Higher scores indicate greater perceived social support [

29]. This instrument was used with permission from the author, Gregory D. Zimet. The MSPSS demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = 0.905 for the total scale, α = 0.970 for the Family subscale, α = 0.942 for the Friends subscale, and α = 0.992 for the Significant Others subscale.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

Prior to data collection, participants received a research notice form describing the study purpose, confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw at any time. Researchers also explained these details verbally and confirmed participants’ understanding before they signed the informed consent form. Participants first completed the self-administered MSPSS questionnaire. Afterward, the researcher conducted the MoCA cognitive assessment. Finally, general and demographic information was collected, as personal questions could influence responses [

30]. In self-administered sections, researchers provided clarifications in a neutral tone of voice without suggesting or directing responses. Completion time was not limited. The average time to complete the full assessment, including cognitive testing, self-assessment of perceived social support, and collection of general and demographic information, was 30 minutes per participant, ranging from 20 to 50 minutes.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and participants could withdraw at any time. Written approval was obtained from the Higher Institution Ethical Committee (Class: 602-01/25-12/03; IRB: 2158/97-97-10-25-12). All participants were informed, both in writing (through a research notice form) and verbally, about the study objectives, ethical aspects, and instructions for completing the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary, confirmed by signing the informed consent form. Anonymity was guaranteed by separating the questionnaire from the consent form. Respondents were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

2.6. Data Analysis

The frequency distributions of the variables were described using descriptive statistical methods. The distribution of numerical variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test, which indicated a statistically significant deviation from normality for the variables under study (p < 0.05). Measures of central tendency and dispersion were expressed as medians (Me) and interquartile ranges (IQR) due to the non-normal distribution of the data. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine differences between two independent groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni correction was applied for comparisons among three or more groups. Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether perceived social support predicts cognitive functioning. Mediation analysis was performed to examine whether perceived social support mediates the relationship between living arrangements and cognitive functioning. Prior to the analyses, regression assumptions were checked, confirming the absence of multicollinearity and influential outliers, and verifying the distribution of residuals. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using JASP software, version 0.19.3 (Department of Psychological Methods, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

4. Discussion

The results of the conducted study indicate that older adults represent a heterogeneous population in which social and cognitive outcomes differ across factors such as age, gender, level of education, marital status, and family structure. These findings confirm the need for a comprehensive, holistic approach to the health of older adults, as emphasized by Livingston et al. [

31].

Regarding participants’ characteristics, most participants were aged 65–74, whereas adults aged 85 and older were underrepresented. Such a distribution is common in healthcare and gerontological research, as the oldest-old are less likely to participate due to health, mobility, or functional limitations [

32]. Additionally, it was observed that older adults with higher educational attainment perceive greater social support, which is consistent with previous studies [

33]. It could be postulated that older adults with lower educational attainment may have smaller or less active social networks, as lower educational attainment has frequently been associated with social isolation [

34]. Furthermore, higher educational attainment influences older adults’ opportunities to access social activities, participate, and achieve better social integration, and it also enables them to make more effective use of community resources [

35]. Therefore, individuals with higher educational attainment are expected to exhibit better cognitive function, largely due to the enhancement of cognitive reserve through lifelong intellectual, educational, occupational, and social activities [

10]. This is also because individuals with greater cognitive reserve enter later life with a higher baseline level of cognitive functioning [

9].

In addition to marital status, family roles such as being a parent or grandparent also contribute to perceived social support. Married older adults perceive higher levels of social support and achieve better cognitive outcomes, consistent with Sommerlad et al. [

36], who report that being married is associated with healthier lifestyle behaviors and lower mortality, and may reduce the risk of dementia due to life-course factors, as well as increased daily social interaction and support, which enhance cognitive reserve. In contrast, lower levels of perceived social support and cognitive functioning are more frequently observed among single and widowed older adults, likely due to the impact of social isolation and its association with adverse cognitive outcomes [

37,

38].

Older adults who are parents and/or grandparents perceive higher overall social support, particularly from family, which is consistent with previous findings [

39]. Hou et al. [

39] demonstrated that intergenerational support from adult children is positively associated with cognitive functioning in middle-aged and older adults, and may mediate the relationship between grandparenting and cognitive function. Thus, caring for grandchildren can indirectly influence cognitive functioning by fostering intergenerational support from adult children [

39]. Frequent, high-quality interactions with children and grandchildren contribute to emotional stability and help maintain cognitive abilities through social engagement and stimulation, supporting previous evidence on the role of social interactions in preserving cognitive function [

39,

40]. A difference was also observed in the perception of social support from significant others by men, as it is assumed that the significant other category most often includes their spouse, who is expected to care for their partner’s needs. Men tend to rely on their spouse for intimacy, emotional, instrumental, and caregiving support [

35]. Al-Kandari [

41] also states that having a living wife is an important factor for men’s health and well-being in general, as the wife is one of the major sources of social support for elderly men.

Although gender differences in overall MoCA scores were not significant in the present study, previous research indicates that women often perform better in verbal domains, as highlighted in methodological evaluations of the MoCA [

42]. Beyond gender, age related differences were also observed, with the oldest-old reporting lower levels of perceived social support. Lower perceived levels of social support among the oldest-old may reflect a decrease in social interactions and the size of social networks as age increases [

43]. Since social participation has been found to decrease with age in both women and men, it is hypothesized that perceived social support also declines alongside reduced social engagement, particularly in women, although this gender difference diminishes after the age of 80 [

35] In contrast, Lara et al. [

37] and Fjell et al. [

44] report that women, on average, have broader and more functional social networks and utilize social support more effectively as a protective mechanism, although this was not observed in the present study. It could be hypothesized that this is due to sociocultural specificities, as Plužarić et al. [

45] in the context of connectedness with family and friends, did not find any significant gender differences among older adults in Croatia.

Age has consistently been identified as a key predictor of cognitive decline, as reported by Piolatta et al. [

16], and the results of this study align with these findings, with older participants achieving lower MoCA scores. The positive association between perceived social support and cognitive functioning is consistent with previous evidence [

19,

46] linking social support and cognitive activity to a reduced risk of subsequent cognitive impairment. Subjective feelings of social support and social integration may benefit cognitive functioning, particularly in stressful situations, by reducing stress and lowering levels of stress hormones such as cortisol, which has been shown to negatively affect cognitive performance [

47].

Additionally, the highest correlation and the greatest explained variance in cognitive functioning were observed within the friend support subscale, which may be explained by the fact that friendships often encourage participation in social and cognitively stimulating activities and enhance older adults’ sense of belonging [

40]. Because maintaining friendships has been shown to require more active effort and engagement in shared activities, activity engagement may be an underlying pathway explaining the distinct associations between contact frequency with friends versus family and cognition [

40]. Friendship ties also play a uniquely protective role in later-life cognitive functioning. Maintaining or restoring active friendship networks promotes social engagement and cognitive stimulation, with the recovery of previously lost friendships being particularly beneficial for cognitive functioning, especially among older men [

48]. Therefore, individuals who perceive higher levels of support from family, friends, or significant others may experience better cognitive outcomes, as social engagement provides emotional, instrumental, and cognitive stimulation that helps preserve cognitive functioning. The results also highlight the importance of the perceived level of social support, rather than merely the absence of social isolation.

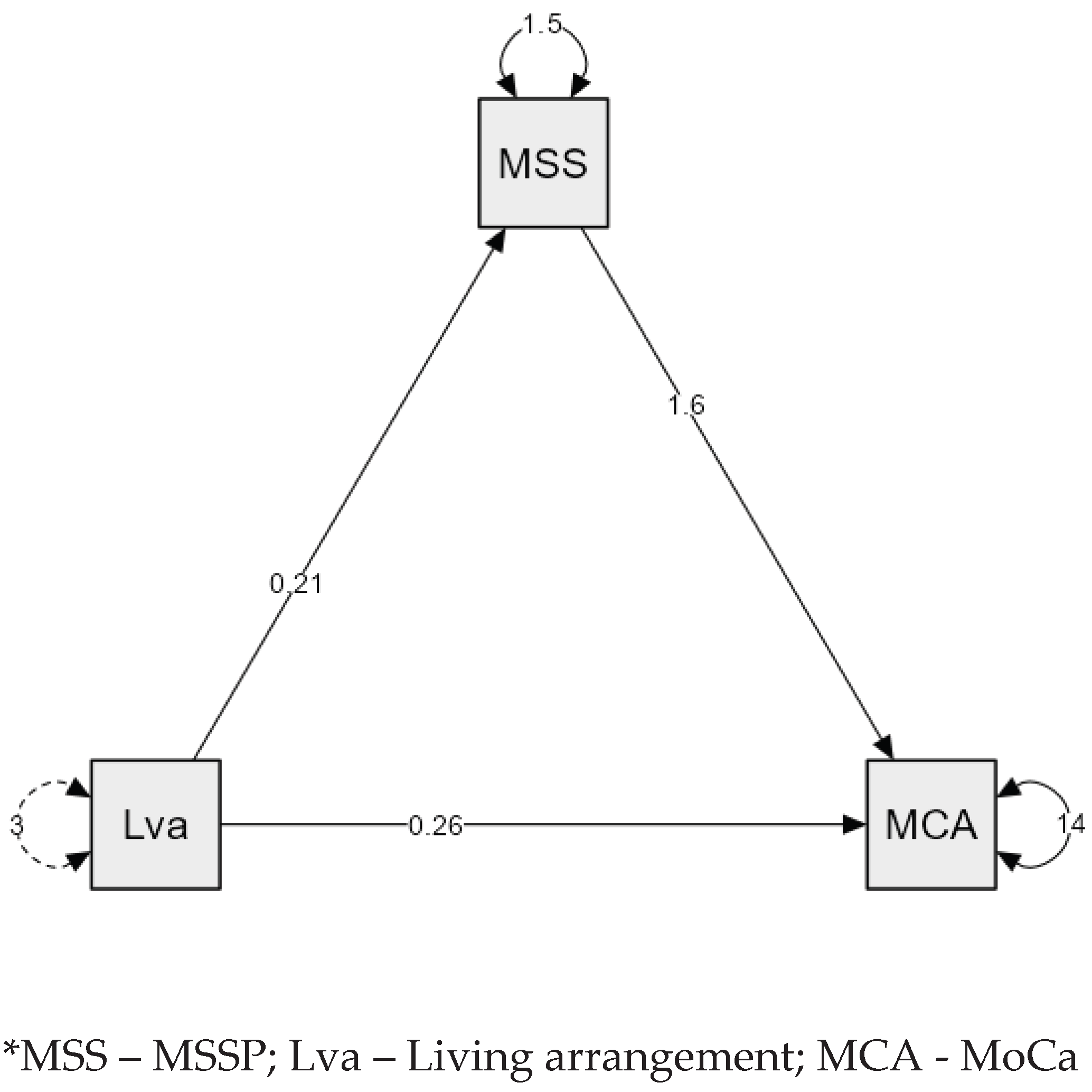

Mediation analysis indicates that living with someone is associated with higher cognitive functioning primarily through perceived social support, rather than through the mere number of cohabitants. This aligns with results reported by Amieva et al. [

49], highlighting the importance of the quality and perception of social relationships in maintaining cognitive abilities in older adults. Participants who felt satisfied with their relationships had a 23% lower risk of dementia, and those who reported giving less support than they received over their lifetime had a 55% lower risk of dementia and a 53% lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease, respectively. Importantly, the only variables associated with subsequent dementia or Alzheimer’s disease were those reflecting the quality of relationships. These findings from the mediation analysis suggest that the perceived level of social support, rather than the mere number of cohabitants, is an important factor for maintaining cognitive functioning in older adults.

4.1. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Despite the valuable findings, this study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design does not allow causal inferences, and longitudinal research is needed to clarify the direction of the association between perceived social support and cognitive abilities. Furthermore, the instruments used carry methodological constraints: the MoCA is sensitive to educational attainment [

50], while the MSPSS reflects a subjective perception of support that may not correspond to its actual structure or quality [

29]. The sample was relatively homogeneous in geographical and cultural terms, which limits the generalizability of the findings, particularly given the known cultural variations in social support structures [

51]. In addition, the participants were predominantly younger older adults compared to the oldest-old group, which may result in a somewhat more optimistic picture relative to the broader older population.

Nevertheless, the study highlights the importance of perceived social support for cognitive functioning in older adults and points to key directions for future research. Longitudinal studies are needed, as well as a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches, the inclusion of diverse cultural contexts, and the development of intervention models aimed at enhancing social engagement. Particular attention should be given to digital forms of social support, which are becoming increasingly relevant in preventing social isolation [

52].

5. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that older adults in rural areas of Vukovar-Srijem County represent a heterogeneous population, with cognitive functioning and perceived social support varying according to age, education level, marital status, family roles, and living arrangements. Older adults with higher educational attainment, those who were married, those with children and grandchildren, and those living in nuclear or multigenerational households exhibited higher levels of social support. Additionally, older adults with higher educational attainment, those who were married, those living in nuclear or multigenerational households, and those with children demonstrated significantly better cognitive functioning. Perceived social support was positively correlated with cognitive outcomes across all domains, with friend support showing the strongest association and also emerging as the most significant predictor of cognitive functioning. Mediation analysis revealed that the beneficial effect of living with others on cognitive functioning is largely explained by the perceived level of social support, highlighting that the perception of social support, rather than mere cohabitation, is crucial for maintaining cognitive abilities in older adults. These findings underscore the importance of interventions aimed at enhancing social support networks, promoting social engagement, and fostering meaningful interpersonal relationships in rural communities. Such measures may help mitigate the negative effects of ageing and limited access to formal care, ultimately supporting cognitive health and overall well-being in older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. M.K., Ž.M., K.M.P. and J.V. methodology. M.K., Ž.M., I.B. and N.F.; software. Ž.M. and I.B.; validation. M.K., Ž.M., N.F. and M.Č.; formal analysis. Ž.M., I.B., J.V. and R.L.; investigation. M.K., Ž.M., M.B. and M.Č.; resources. M.K. and M.B.; data curation. R.L., K.M.P., J.V. and M.Č.; writing—original draft preparation. M.K., Ž.M., N.F., K.M.P. and M.B.; writing—review and editing. M.K., Ž.M., M.Č., R.L., I.B. and J.V.; visualization. M.K., M.B. and K.M.P.; supervision. N.F. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.