1. Introduction

The fundamental sequence of events in eukaryotic translation has been known for decades: an mRNA first associates with the small (40S) ribosomal subunit, the large (60S) subunit then joins to form an 80S ribosome, and one or more ribosomes translate the mRNA concurrently. This mechanistic framework defines several principal molecular states, including free mRNA, free 40S and 60S subunits, 40S-bound mRNA, and actively translating ribosomes in the form of monosomes, disomes, and polysomes. The balance between the various ribosomal subunits and assembly states is tightly regulated (1). Polysome profiling, which separates these complexes by sedimentation through a sucrose gradient, remains a key method for resolving and quantifying these states (

Figure 1).

In addition to these canonical translating species, non-translating ribosomal complexes have also been described, most notably vacant monosomes and disomes. These complexes consist of fully assembled ribosomes lacking bound mRNA and typically arise under starvation or stress, and remain less well characterized. They appear in the literature under several partially overlapping terms, including vacant, idle, empty, inactive, and silent ribosomes.

When cells enter stationary phase, growth ceases and translation demand decreases. To adjust, microorganisms reduce their ribosome content through autophagy and other turnover pathways. Not all ribosomes are degraded, however; a fraction enters a dormant state in which the small and large subunits remain assembled as an 80S ribosome but lack mRNA and translational activity. These hibernating ribosomes were first described in prokaryotes (2), and for a long time ribosome hibernation was believed to be restricted to bacteria and plant plastids (3). Systematic exploration of potential eukaryotic counterparts began only much later.

In this review, we examine the factors that contributed to this temporal gap, focusing on the methodological and mechanistic differences that may have obscured or delayed the recognition of silent ribosomes in eukaryotes. We then summarize recent advances demonstrating that dormant or silent ribosomes occur in organisms ranging from yeast to mammals. We begin by outlining key principles from bacterial hibernation—drawing only on concepts necessary for comparison—before turning to eukaryotic systems, with a focus on budding yeast and mammalian cells, and paying particular attention to neurons, where monosomes are abundant and their distinction from translating ribosomes is especially critical.

2. Dormant Ribosomes in Prokaryotes and Plant Chloroplasts

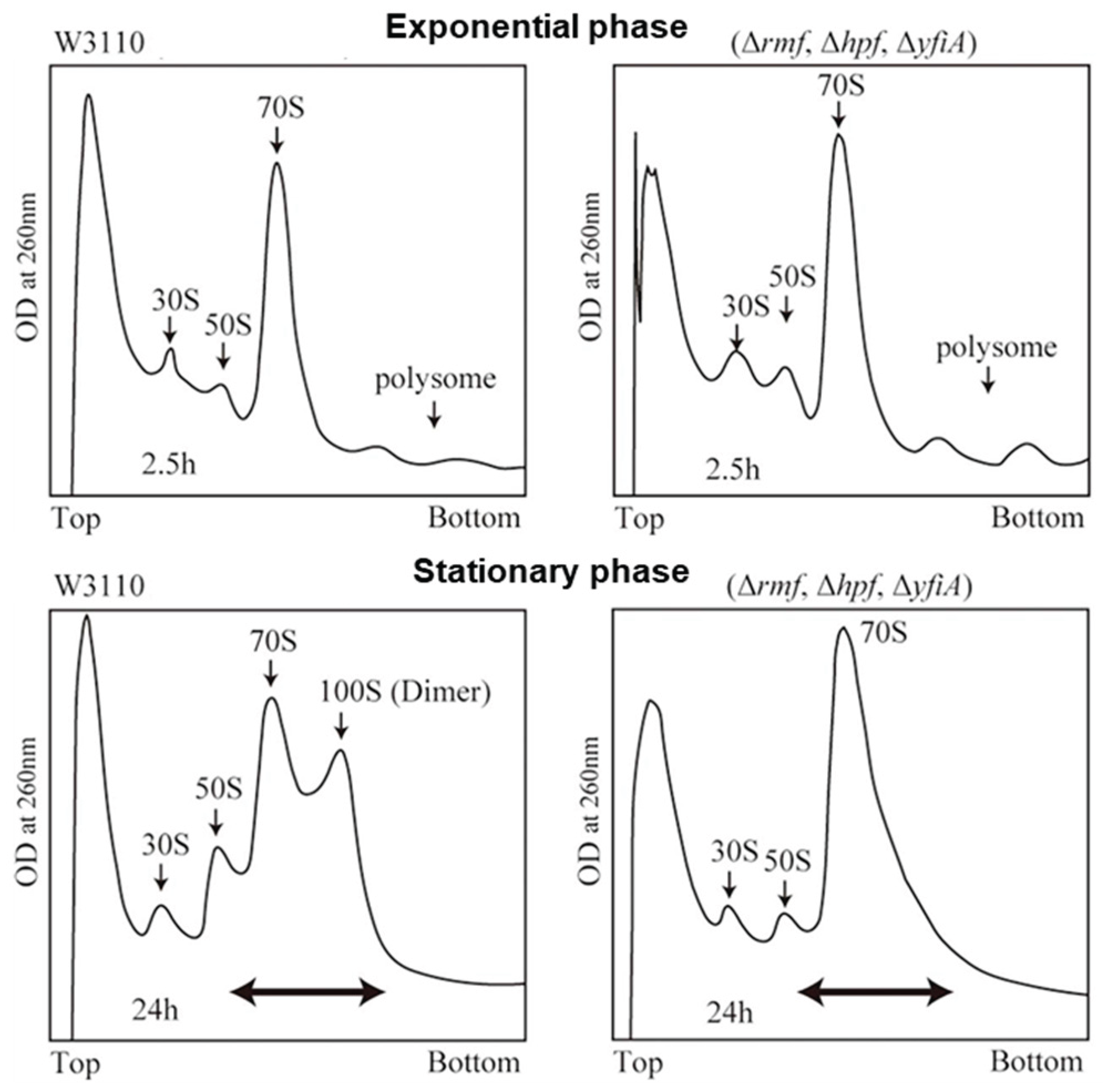

In bacteria, one of the most striking alterations of the translational apparatus during entry into stationary phase is the progressive increase of the 100S dimer peak, accompanied by a concomitant decrease of 70S monosomes and polysomes (5) (

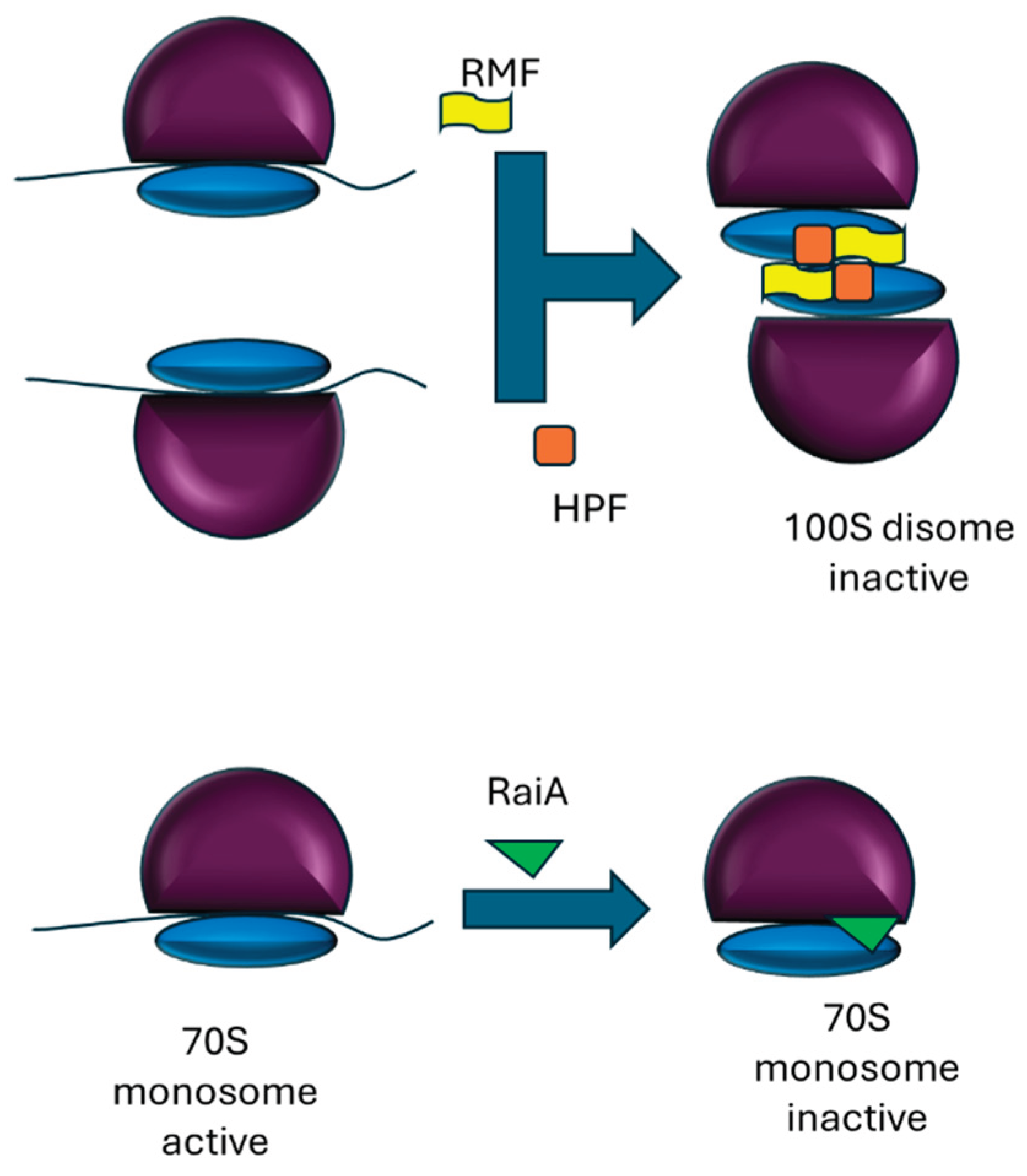

Figure 2). Although early biochemical studies hinted that 100S ribosomes represented a dormant yet rapidly reactivatable state, the physiological relevance of 100S dimers was not firmly established until the 1990s, in part because research had predominantly focused on exponentially growing cells (2, 6). In E. coli and many other bacteria, the formation of the 100S ribosomes is mediated by ribosome modulation factor (RMF) and hibernation promoting factor (HPF). Gram-positive bacteria lack RMF but encode a long HPF isoform (lHPF) whose extended C-terminal region promotes dimerization by direct protein–protein interactions (7).

In addition to 100S dimers, bacteria also produce hibernating monosomes mediated by RaiA (also known as YfiA in some species). RaiA is homologous to HPF but carries a short C-terminal extension that likely interferes with RMF binding and therefore disfavors 100S dimerization. RaiA overexpression increases the proportion of intact 70S ribosomes relative to dissociated subunits during stationary phase, consistent with the hypothesis that RaiA stabilizes functional 70S particles and thereby shortens the lag phase upon growth resumption (8).

Recent work demonstrated that the three E. coli hibernation factors RMF, HPF, and RaiA act cooperatively to confer ribosome protection during carbon starvation. Cells lacking all three show severely impaired regrowth and accumulate 70S ribosomes with fragmented 16S rRNA, whereas rRNA in wild-type 100S dimers remains intact. The fragmentation is suppressed in strains lacking RNases YbeY and RNase R, suggesting that the hibernation factors protect ribosomes by physically blocking ribonuclease access (3).

A related mechanism operates in plant chloroplasts, evolutionarily derived from bacteria, which encode plastid-specific ribosomal protein 1 (PSRP1), the chloroplast ortholog of bacterial HPF. Although PSRP1 can induce 100S-like dimers, chloroplast 100S particles have not been detected in vivo or in vitro, implying that chloroplast ribosome protection diverges mechanistically from bacterial dimerization-based hibernation, and that organellar ribosomes have evolved lineage-specific adaptations tailored to their physiological environment (9).

3. From Bacteria to Eukaryotes: Challenges to Identifying Vacant Ribosomes

In prokaryotes, two key features have enabled a systematic and detailed characterization of dimeric hibernating ribosomes: (i) distinctive polysome profile signatures and (ii) well-defined, stress-regulated hibernation factors. As a result, by the early 2000s, a nearly complete picture of bacterial ribosome hibernation had emerged.

The dimeric form is particularly well described, as it generates a characteristic disome peak in stationary-phase polysome profiles. Its molecular basis is firmly established: deletion of RMF and HPF abolishes this peak, demonstrating their essential role in dimer formation (5). Moreover, RMF transcription negatively correlates with growth rate and is induced by diverse stresses, including amino-acid starvation, heat and cold shock, ethanol, pH and osmotic stress, and envelope perturbation (2).

In contrast, dimeric silent ribosomes are largely absent in eukaryotes—with only isolated reports discussed below (10, 11)—potentially explaining why the characterization of eukaryotic silent ribosomes has progressed more slowly. In eukaryotic cells, silent ribosomes are generally monomeric. Yet even for these monomeric forms, eukaryotes lack the two key features that greatly facilitated the study of their prokaryotic counterparts.

First, the monomeric hibernation factor in bacteria, RaiA, is homologous to the dimer-associated factor RMF, providing an evolutionary and mechanistic link that guided experimental interpretation. In addition, RaiA overexpression produces a clear and quantifiable increase in the monosome peak, serving as a robust experimental readout (8, 12) and providing a clear experimental signature of its function.

Second, bacterial hibernation factors show strong stress-dependent induction, such as the marked upregulation of YfiA (a RaiA homolog) in stationary phase (13), making them easy to identify as stress-responsive ribosome regulators. By contrast, eukaryotic candidates such as Stm1 are already present during exponential growth and do not increase under starvation or stress (14), rendering their functional role l less immediately apparent. Nevertheless, important gaps remain even in prokaryotes. For instance, a pronounced monosome peak emerges in E. coli under carbon and nitrogen starvation, yet the deletion of raiA has no detectable effect on polysome profiles (15), indicating that the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

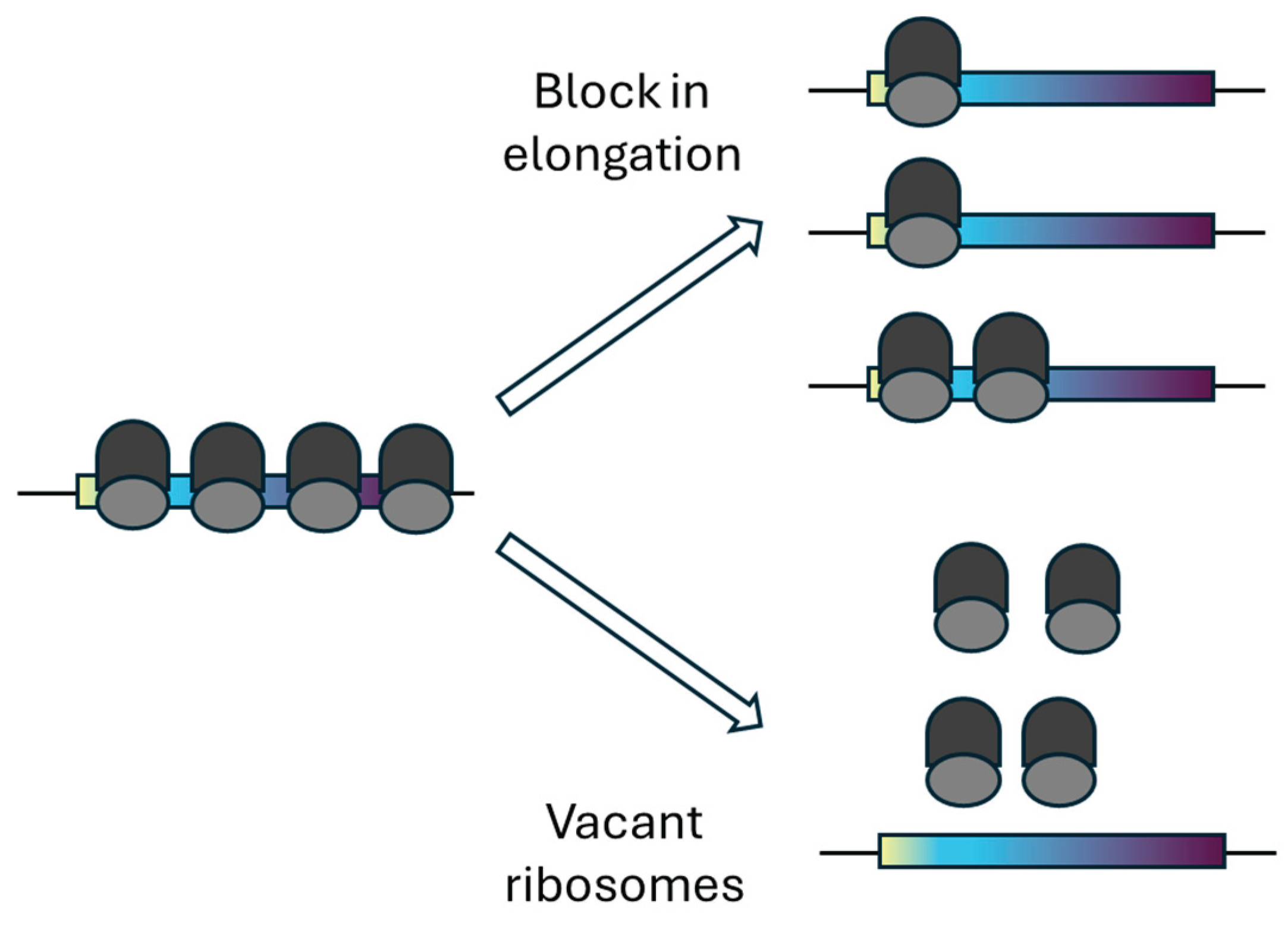

Shifts from polysome to monosome dominance in eukaryotes occurs under diverse stresses—including starvation, cold shock, heat shock, and lithium exposure—and were historically interpreted as a result of inhibition of initiation or early elongation rather than formation of vacant ribosomes (16, 17). These two mechanisms are experimentally challenging to distinguish (

Figure 3).

For example, during heat stress, ribosomes stall shortly after initiation. A detailed analysis in mammalian cells revealed a response highly similar to that induced by harringtonine, which blocks elongation during the first peptide bonds (18). After harringtonine treatment, cells accumulate monosomes and light polysomes at the expense of heavy polysomes, a pattern similar to the one observed after heat shock. Ribosome profiling showed ribosome accumulation close to the start codon that have led to the following conclusion “mRNAs with ribosomes paused at typical locations (around 200 nt) are expected to migrate mostly as lighter polysomes or monosomes, depending on whether additional ribosomes accumulate upstream of the pause.” (19). This early elongation block is augmented when heat shock proteins are inhibited and alleviated by HSP overexpression, demonstrating their direct role in regulating translation elongation near the start codon. Similar HSP-dependent pausing of ribosomes has also been observed in proteotoxic stress (20). A related mechanism exists under lithium stress, where inhibition of translation initiation in galactose-grown yeast cells can be alleviated by eIF4A overexpression, suggesting interference with early initiation steps rather than elongation (17). Several additional mechanisms link translational elongation to cellular stress responses. Stress-induced covalent modifications of the tRNA anticodon stem–loop—particularly at wobble positions—can modulate codon–anticodon pairing efficiency and thereby alter elongation dynamics (21). For example, loss of cytosine methylation in a specific tRNA causes ribosome stalling, reduces translation efficiency, and ultimately impairs C. elegans’ ability to adapt to elevated temperatures (22).

Recent results indicate, however, that at least some stresses—such as heat shock—primarily act through the formation of silent ribosomes (12). Why, then, have these phenomena been interpreted as initiation/elongation blocks rather than ribosome dormancy? A key contextual factor is that early elongation is intrinsically rate-limiting in eukaryotes, which show a much slower transition from initiation to elongation than E. coli. This slowdown is linked to the prolonged residence time of eIF5B on the 80S ribosome after subunit joining (23, 24).

Taken together, these findings indicate that increases in monosomal (and lighter polysomal) fractions and the concomitant loss of heavy polysomes in eukaryotes may arise from either formation of silent ribosomes or early-elongation/initiation stalls, and that these processes may co-occur.

3.1. Protein Interactions with Dormant Ribosomes in Yeasts

Given that alternative mechanisms that can lead to the accumulation of monosomes—particularly elongation-blocked versus vacant ribosomes—it is unsurprising that the identification of eukaryotic silent ribosomes lagged by ~20 years behind that in E. coli.

The earliest evidence for silent ribosomes in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae came from structural studies of ribosomes purified from cells subjected to brief glucose starvation (25). Under these conditions, the protein Stm1 was found associated with the 40S subunit, where it blocks the mRNA entry channel. Owing to its translation-inhibitory effect (

Table 1), it was proposed in 2011 that Stm1 acts to preserve ribosomes in an inactive state during nutrient limitation, thereby serving as a functional analog of the stress-induced ribosome preservation factors found in bacteria and chloroplasts (25).

Subsequent experiments, however, showed that Stm1 is not required for the rapid formation of silent ribosomes. Deletion of STM1 did not eliminate the prominent monosome peak induced by short glucose depletion (≈10 min) (28). Similarly, silent ribosomes also accumulate after heat shock (≈30 min), yet stm1Δ strains again showed no reduction in monosome formation (12). Thus, the formation of vacant ribosomes during short-term stress (<1 h) occurs independently of Stm1.

By contrast, Stm1 becomes important during prolonged starvation and quiescence. During long-term starvation, Stm1 contributes to ribosome preservation (26). In 4-day stationary cultures, STM1 deletion reduces, whereas STM1 overexpression increases, the monosome peak (14). In the presence of Stm1, protein synthesis is resumed faster after exit from quiescence; polysome reassembly is impaired in stm1Δ cells, indicating that Stm1 primarily preserves ribosomes for efficient reactivation, rather than being required for silent-ribosome formation itself (14).

Together, these findings support the following framework: acute stress triggers the rapid formation of vacant ribosomes independently of Stm1, whereas Stm1 preserves ribosomes during extended starvation, thereby enabling rapid translation restart—a process further supported by Dom34-mediated reactivation (

Table 1). Thus, vacant ribosomes associated with Stm1 can be detected in both short-term and long-term starvation or stress; however, the functional role of Stm1 can be assigned reliably only in long-term experiments due to the slow degradation of proteins.

A distinct but non-exclusive mechanism operates in Schizosaccharomyces pombe during deep quiescence (seven days of glucose depletion). Here, mitochondrial fragmentation triggers sequestration of cytosolic ribosomes on mitochondria. Cryo-EM analyses revealed that these ribosomes are devoid of mRNA and tRNA, and assemble into higher-order oligomeric arrays on the mitochondrial surface. This anchoring is mediated by the ribosomal protein Cpc2/RACK1, which binds the outer mitochondrial membrane via the small subunit (29).

Whether a similar process exists in budding yeast remains unresolved. However, it is notable that Fmp45 is one of the three most strongly heat-induced monosome-associated proteins (Mbf1, Lso2, Fmp45) (12). Fmp45 is mitochondrial and is required for long-term quiescence survival—its deletion reduces viability by ~100-fold after 16 days at 37 °C (30). This raises the possibility that mitochondrial anchoring also occurs in S. cerevisiae.

3.2. Dimeric Hibernating Ribosomes in Eukaryotes?

Although an increase in monosomes is the predominant hallmark of ribosome hibernation in eukaryotes, scattered reports indicate that ribosome dimers can also form under certain conditions. For example, in the microsporidian parasite Spraguea lophii, ribosome dimers appear during sporulation with the assistance of the hibernation factor MDF1 (11).

Dimeric ribosomes have also been reported in metazoan cells, although in a highly restricted context. Polysome profiling revealed that rat—though not human or mouse—cells produce ribosomal dimers that closely resemble the 100S particles seen in bacteria. These ~110S peaks were detected only in amino-acid–starved C6 glioma cells, and the reason for this species- and cell-type specificity remains unclear (10). Cryo-EM analysis confirmed that these sucrose-gradient fractions indeed contained ribosome dimers. Notably, the formation of these dimers did not require new transcription or translation, and no proteinaceous hibernation factors were detected, echoing the oligomeric, higher-order ribosome assemblies observed in fission yeast during deep quiescence (see above).

It is important to note that ribosome disomes can also arise from collisions, yet these complexes fundamentally differ from vacant ribosomal dimers. Collision-induced disomes form on mRNAs when a fast-moving ribosome encounters a slow-decoding region (31), a phenomenon whose frequency can increase under stress, moreover, such collisions activate dedicated stress-response pathways (32). Because decoding rates change dynamically with tRNA availability, fluctuations in tRNA pools can further influence the likelihood of ribosome collisions (33). Despite this, ribosome collisions remain relatively infrequent but can be selectively isolated by RNase I digestion. Upon digestion, collided ribosomes within disomes or polysomes generate a characteristic RNase-resistant disome peak (34), but its magnitude does not reach that of the 100S-like dimers seen in bacteria. Overall, these considerations indicate that bona fide ribosome dimers are exceptional in eukaryotes—occurring only under highly specific conditions in both unicellular organisms and metazoans.

3.3. Vacant Monosomes in Metazoans and Mammals

The dominant response to starvation in mammalian cells resembles that in budding yeast, but the functional role of yeast Stm1 is taken over by the Stm1 homolog SERBP1 (SerpineE1 mRNA-binding protein) in mammals during the formation vacant monosomes (35, 36).

Further evidence suggests that vacant monosomes are less common in metazoans than previously assumed. In Drosophila, cryo-EM analyses of head tissue revealed that the overwhelming majority of monosomes carried at least one tRNA; only ~2% lacked tRNA, indicating that most ribosomes were translationally active (37). A similarly high fraction of active ribosomes was found in embryonic tissue. Only two organs—ovaries and testes—displayed predominantly vacant monosomes. In testes, these monosomes associated with the interferon-related developmental regulator 1 (IFRD1). Importantly, the cryo-EM findings were corroborated by ionic-strength–based dissociation assays.

Earlier biochemical studies revealed this high-salt dissociation principle, showing that monosomal fractions from both normal and stressed cells contain a population of empty ribosomes—assembled 80S particles not bound to mRNA. Incubation of extracts under high-salt (increased ionic strength) conditions reversibly dissociates such vacant monosomes into their 40S and 60S subunits, whereas polysomal ribosome–mRNA complexes remain intact in high salt (28, 38, 39). Polysome-derived ribosomes converted to monosomes by RNAse treatment also resisted disassembly in high salt conditions, indicating that salt-sensitive monosomes are devoid of RNA and/or other translation associated factors rather than bound to short or fragmented RNA (38, 39). Consistent with this, experiments supplementing 200 mM KCl to lysis buffers already containing 150 mM NaCl showed that most monosomes from ovaries dissociate under high ionic strength, whereas monosomes from head tissue remain largely intact. Testis-derived 80S monosomes exhibited intermediate salt sensitivity—potentially due to stabilization by IFRD1—demonstrating that distinct types of vacant ribosomes differ in their biochemical stability (37).

The fact that most monosomes in the brain are active is important because many neurons preferentially use monosomes to translate mRNAs (40). In fact, in neurons, a substantial proportion of the polysomes may be inactive (41), revealing a distinct form of regulation. This ensues due to the limiting availability of the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) and by inactivating a proportion of polysomes, the remaining polysomes can recruit sufficient amount of eEF2 to support fast elongation. There are other special features of translational elongation in the brain. For example, Mutations in tRNA-metabolism genes can cause leukodystrophies characterized by oligodendrocyte defects and hypomyelination, in part because oligodendrocytes harbor hypomodified tRNAs (42). This hypomodification likely reflects the differential expression of tRNA-modifying enzymes during oligodendrocyte differentiation, creating a naturally sensitive tRNA–mRNA axis. Disruption of this axis may contribute to the pathology of leukodystrophies and other white-matter disorders.

4. Methodological Challenges in Quantifying Processes Related to the Formation of Vacant Ribosomes

4.1. Distinguishing Vacant Ribosomes from Elongation Blockade

The formation of vacant ribosomes represents an important facet of translational regulation and is tightly interconnected with other aspects of translation, particularly early elongation. Because both processes can produce similar polysome profiles—most notably an increase in the monosome peak—their experimental distinction has been challenging (see above), despite early studies suggesting a clear role for elongation control in mammalian systems.

Several lines of evidence, however, suggest that silent ribosome formation, rather than elongation blockade, plays the predominant role in yeast. Although an increase in the monosome peak could in principle reflect a shift of most mRNAs from polysomes to monosomes, no such redistribution was observed at the level of individual transcripts, indicating that monosomes can accumulate without associated mRNAs (12). Conceptually, this could be validated by comparing the relative shifts of ribosomal proteins and mRNAs into the monosomal fraction; in practice, however, such approaches are complicated by cross-normalization issues, since protein and RNA measurements rely on distinct analytical modalities (proteomics vs. RNA-seq).

Quantification based on total rRNA initially failed because 5S rRNA exhibited anomalous amplification, particularly within the monosome fraction, leading to an overestimation of vacant ribosomes. Excluding 5S rRNA yielded robust and internally consistent estimates that were corroborated using transcript-selective mRNA:rRNA qPCR ratios, supporting the conclusion that vacant ribosomes constitute the dominant species in yeast under these conditions. By contrast, mammalian cells may behave differently: in heat-stressed macrophage J774A.1 cells, a pronounced reduction in mRNA polysome association has been observed (12), suggesting that translational arrest is, in part, regulated at the elongation stage.

Because elongation blockade and silent ribosome formation can co-occur, methodologies capable of detecting both ribosome position and mRNA:rRNA stoichiometry are needed to quantitatively disentangle their contributions. One such approach is based on ribosome footprinting coupled to stoichiometric analysis (43), although it remains unclear whether anomalous amplification affects this method, as RNase digestion used for footprinting also cleaves rRNA, unlike standard polysome profiling. Another strategy employing ultrafiltration combined with spike-in-based calibration has recently been developed to remove unwanted rRNA fragments and derive absolute ribosome:mRNA stoichiometries following RNase treatment (44). Interestingly, this calibrated approach confirmed relative enrichment of ribosomes near the early coding region under heat shock, consistent with earlier studies (19, 20) but the ribosomal calibration step eliminated the apparent ribosome pile-up.

While this method provides accurate values for complexes containing more than one translating ribosome, further modifications will be required to apply it directly to vacant ribosomes. In addition to above mentioned challenges of distinguishing between elongation blockade and silent ribosome formation, other translation-related processes—most notably the regulation of translational efficiency—are also sensitive to methodological variables. Such sensitivities can have substantial impact on the interpretation of experimental results.

4.2. Quantifying Post-Transcriptional Processes Under Stress

A well-known confounding variable is ethanol present either as chemical solvent or as a byproduct of metabolism. For example, cycloheximide (CHX) is routinely added to stabilize ribosome–mRNA complexes and prevent ribosomal runoff (45). However, when CHX is dissolved in ethanol, it induces transcription of ribosome biogenesis (RiBi) genes. Further, ethanol alone has a similar, albeit weaker, effect (46). This can lead to two types of misinterpretation: (i) that RiBi is transcriptionally induced under the tested condition and (ii) that translation efficiency is reduced, because RiBi mRNAs accumulate but are not translated (46). These artefacts can be mitigated by dissolving CHX in DMSO (46), and by reducing the time between CHX addition and cell harvesting since perturbations display a delayed kinetics (12).

Importantly, ethanol can also accumulate endogenously through glucose fermentation once yeast cells exit the mid-log phase (47). Thus, part of the translational repression attributed to starvation or stationary-phase physiology may arise indirectly through ethanol production. This further implies that cultures at different starvation or stationary-state stages may behave differently. A related phenomenon has been reported in bacteria, where translation first declines but then appears to re-activate after extended stationary phase (around day 6), as indicated by reassociation of translation factors with ribosomes (48).

In addition to CHX and ethanol, condition-specific accumulation of RiBi mRNAs has been observed with other translation inhibitors, suggesting that this response may reflect a broader feedback mechanism triggered by global translation inhibition (49). CHX has also been shown to inhibit translation of different mRNAs to different extents in mammalian cells (50), underscoring that inhibition profiles are transcript-specific and context-dependent.

Beyond the measurement of translation efficiency, other post-transcriptional processes—such as mRNA degradation—can also be perturbed under conditions that promote the formation of vacant ribosomes. Each experimental approach introduces its own perturbations, and these can be amplified under stress, creating an adverse synergy between the measurement method and the physiological state (51, 52). This interplay is well illustrated under heat stress, where the nucleotide analogs used to determine mRNA half-lives can themselves alter decay rates (12). Accurate quantification therefore requires careful calibration of analog concentration to minimize such perturbations. Furthermore, the distinction of vacant ribosomes from translationally active monosomes and inactive polysomes will be important in deciphering the posttranslational mechanism, as only polysomes have been associated with differential translation and stabilization of mRNAs half-lives enriched in optimal versus non-optimal codons (51, 53). Interestingly, monosomes translate a distinct set of proteins in neurons, particularly cell-cell adhesion proteins (40), which can play important role in the determination of cell identities (54). Development of new methods will be required to decipher the rates of processes, such as mRNA degradation, associated with monosomes and polysomes. An important step toward this direction is the measurement of rates of nascent mRNA synthesis and translation (55).

4.3. Stress-Induced Changes in Cytoplasmic Biophysical Properties

Several biophysical properties of the cytoplasm change during stress. When polysomes dissociate, the released mRNAs frequently condense with RNA-binding proteins to form stress granules. This reorganization alters the material state of the cytoplasm: both the loss of polysomal scaffolding and the redistribution of mRNAs within the cytosol modify the elastic confinement that normally limits mesoscale diffusion. As a result, cytoplasmic fluidity transiently increases—typically for one to two hours—effectively doubling the diffusion coefficient (56). While enzymatic activities may decrease during stress, the concomitant increase in diffusivity can accelerate reaction kinetics, potentially masking or counterbalancing the inhibitory effects. These dynamic changes must be considered when interpreting reaction rate constants under stress conditions.

It is also important to note that vacant ribosomes protect the entire ribosome during stress, whereas stress granules primarily safeguard mRNAs together with the small ribosomal subunit. However, recent findings indicate that these compartments are not as distinct as once thought: cryogenic correlative light and electron microscopy has revealed that stress granules can contain substantial amounts of 80S ribosomes (57), suggesting a closer functional and structural interplay between ribosome protection and mRNA sequestration than previously appreciated. These 80S ribosomes are idle, in agreement with the observation that mRNAs are released from such ribosomes since solitary stalled 80S monosomes prevents mRNA recruitment to stress granules (58).