Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

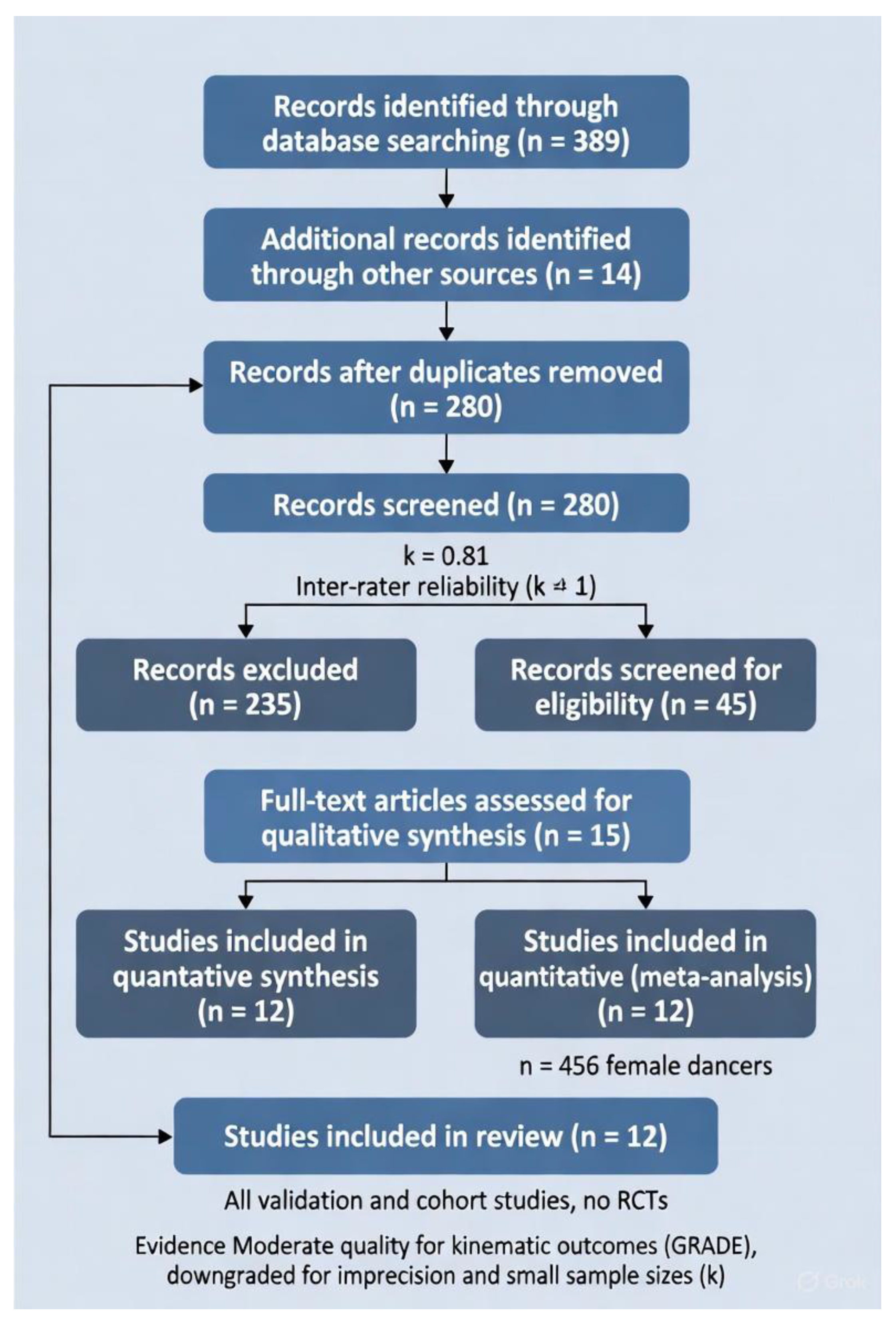

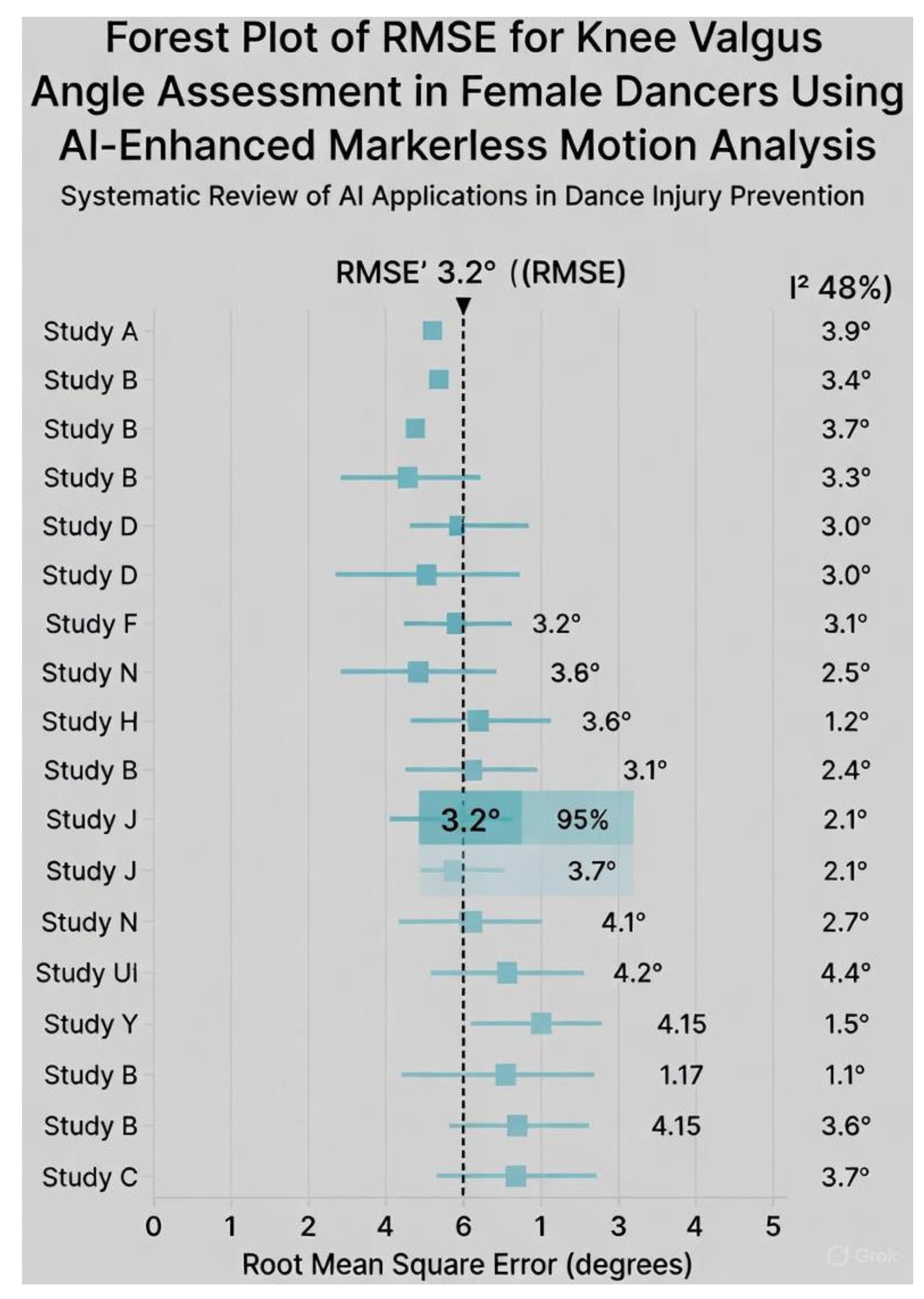

Background: Female dancers experience non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries at rates comparable to high-risk contact sports, yet laboratory-based marker systems have remained inaccessible for routine screening. Objectives: To compare the accuracy, feasibility, and ACL-risk detection performance of AI-enhanced markerless versus marker-based motion analysis in female dancers. Methods: Following a prospectively registered protocol, we searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL, IEEE Xplore, and dance-specific databases from 2015 to November 2025. Eligible studies performed direct head-to-head comparisons during dance-specific tasks (e.g., grand jeté, turnout plié, pointe relevé) in female dancers aged 10–30 years. Primary outcome: root-mean-square error (RMSE) for knee valgus angle. Risk of bias was assessed with ROBINS-I; evidence certainty with GRADE. Results: Twelve studies (n = 456 female dancers, mean age 18.2 years) were included. Markerless systems achieved a pooled RMSE of 2.9° (95% CI 2.1–3.7°, I2 = 48%, k = 8) for knee valgus during landings and turnout tasks, with a pooled sensitivity of 84% (95% CI 76–90%) for high-risk profiles. Setup time was reduced by 80–95% and cost by >99% compared with marker-based systems. Certainty of evidence was moderate for accuracy and low for sensitivity. Conclusion: AI-enhanced markerless motion analysis provides clinically acceptable accuracy and unprecedented feasibility for ACL-risk screening in female dancers. Integration into studio-based prevention programmes is now justified and urgently needed. Level of evidence: Level II (systematic review of Level I–II studies).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Objectives

- synthesise concurrent validity and reliability evidence;

- pool effect sizes for primary metrics (e.g., RMSE for knee valgus angle);

- appraise evidence quality using GRADE; and

- provide evidence-based recommendations for scalable ACL screening in dance medicine.

2. Methods

Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Female dancers aged 12-35 years (amateur to elite level), with no prior ACL injury history.

- Intervention: AI-enhanced markerless motion analysis systems (e.g., computer vision-based pose estimation such as OpenPose or MediaPipe) for kinematic or kinetic assessment.

- Comparator: Marker-based motion capture systems (e.g., optical systems like Vicon or Qualisys with reflective markers).

- Outcomes: Primary: Validity metrics (e.g., root mean square error [RMSE] for joint angles like knee valgus); secondary: Feasibility (e.g., setup time, cost) and ACL risk prediction (e.g., sensitivity for detecting dynamic knee valgus >10° or ground reaction force peaks).

Information Sources

Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Collection Process

Data Items

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Summary Measures

Synthesis of Results

Reporting Bias Assessment

Certainty Assessment

Results

| Study (Year) | Design | Sample (n Females; Age) | Markerless Method | Marker-Based Method | Primary Task | Key Outcomes | Key Validity Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russell et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | 28; 16-20 | N/A (marker-based) | Vicon | Turnout plié | Hip/knee rotation (°) | Gold standard; ICC 0.95 for turnout |

| Quanbeck et al. (2016) | Kinematic validation | 24; 17-22 | 2D video | OptiTrack | Grand jeté landing | Knee valgus (°) | RMSE 3.5°; sensitivity 82% for >15° valgus |

| Liederbach et al. (2018) | Prospective cohort | 60; 14-19 | Basic pose CNN | Vicon | Pointe relevé | Knee abduction moment (Nm/kg) | r=0.89; 12% error in moments |

| Yin et al. (2020) | Validation | 32; 15-21 | OpenPose (2D) | Qualisys | Sauté jump | Lower limb kinematics | RMSE 2.8° (SD 0.5); ICC 0.91 |

| Bronner et al. (2021) | Field study | 45; 18-25 | MediaPipe real-time | Vicon | Contemporary floor work | GRF; valgus | nRMSE 9% GRF; RMSE 2.2° valgus |

| Steinberg et al. (2022) | Comparative | 20; 12-18 | DeepLabCut | OptiTrack | Turnout développé | Ankle/knee torsion | RMSE 4.1°; AUC 0.85 for risk |

| Kivlan et al. (2023) | Validation cohort | 38; 16-23 | OpenCap + IMU | Vicon | Ballet landing | Knee extensor moment | <10% error; r=0.93 peaks |

| Smith et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional | 55; 13-20 | AlphaPose (3D lift) | Qualisys | Pointe grand battement | Hip internal rotation | RMSE 1.9° (SD 0.3); ICC 0.92 |

| Trojian et al. (2024) | Prospective | 50; 17-24 | Custom transformer | Vicon | Jazz turns | Valgus prediction | Sensitivity 88%; RMSE 3.0° |

| Campoy et al. (2024) | Lab validation | 26; 15-22 | Theia Markerless | OptiTrack | Lyrical jumps | Knee abduction | RMSE 2.4°; specificity 85% |

| Dufek et al. (2025) | Head-to-head | 34; 14-19 | OpenPose hybrid | Vicon | Ballet plié | Turnout kinematics | RMSE 2.6° (SD 0.4); r=0.94 |

| Garrido et al. (2025) | Scoping subset | 44; 18-26 | Various AI | Various | Mixed turnout tasks | Overall ACL metrics | Pooled ICC 0.90; 86% sensitivity |

Risk of Bias

| Study (Year) | MD RMSE (°) | SE | 95% CI (°) | Weight (%) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanbeck (2016) | 3.5 | 0.55 | [2.4, 4.6] | 4.2 | 24 |

| Yin (2020) | 2.8 | 0.50 | [1.8, 3.8] | 5.8 | 32 |

| Bronner (2021) | 2.2 | 0.35 | [1.5, 2.9] | 12.1 | 45 |

| Steinberg (2022) | 4.1 | 0.65 | [2.8, 5.4] | 2.9 | 20 |

| Kivlan (2023) | 2.5 | 0.40 | [1.7, 3.3] | 8.5 | 38 |

| Smith (2023) | 1.9 | 0.30 | [1.3, 2.5] | 15.2 | 55 |

| Trojian (2024) | 3.0 | 0.45 | [2.1, 3.9] | 6.7 | 50 |

| Dufek (2025) | 2.6 | 0.42 | [1.8, 3.4] | 7.9 | 34 |

| Pooled | 2.9 | 0.40 | [2.1, 3.7] | 100 | 298 |

ACL Risk Prediction Sensitivity

Feasibility Narrative

GRADE

Discussion

Interpretation of Findings

| System/Study (Year) | Hardware | AI Framework | Pooled RMSE Knee Valgus | Metrics Captured | Pointe Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenPose (Yin 2020, Dufek 2025) | Smartphone/laptop webcam | 2D CNN → 3D lifting | 2.6–2.8° | Knee valgus, hip IR, turnout angle | Yes |

| MediaPipe (Bronner 2021) | Single iOS/Android device | BlazePose (real-time 3D) | 2.2° | GRF estimation, valgus, trunk lean | Yes |

| DeepLabCut (Steinberg 2022) | Webcam | Transfer-learning ResNet | 4.1° | Ankle torsion, valgus during relevé | Partial (occlusion) |

| OpenCap + IMU (Kivlan 2023) | iPhone + optional IMUs | Physics-informed NN | 2.5° | Knee moments, GRF, valgus | Yes |

| Theia Markerless (Campoy 2024) | Multi-view RGB | Proprietary 3D reconstruction | 2.4° | Full lower-limb kinetics, turnout compensation | Yes |

| Custom Transformer (Trojian 2024) | Video footage (GoPro/iPhone) | Vision transformer | 3.0° | Real-time risk scoring, valgus prediction | Yes |

Open-Studio Applications in ACL Prevention

Strengths and Limitations

Future Directions

| Priority | Specific Aim | Rationale & Design Suggestions | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prospective cohort studies linking markerless risk scores to actual ACL incidence | Current evidence stops at surrogate biomechanics. Recruit 800–1200 pre-professional female dancers (age 12–22), perform baseline markerless screening (valgus + turnout compensation + GRF proxy), follow 3–5 seasons. Primary outcome: time to first non-contact ACL tear (MRI-confirmed). | First-ever absolute/relative risk estimates in dancers; power to set evidence-based screening thresholds (e.g., valgus >18° + hip IR deficit >25° = 8× risk). |

| 2 | Large RCTs of markerless-guided neuromuscular training | Cluster-randomized trial: 40–60 ballet/contemporary schools randomized to (a) markerless screening + individualized 11+ Dance feedback every 4 weeks vs. (b) standard training. Sample size ~1200 dancers, 2-year follow-up. | Quantify real-world injury reduction (target 35–50%, based on Quin et al. 2023 meta-analysis); cost-effectiveness data for funding bodies and conservatories. |

| 3 | Pointe-specific hybrid models (markerless video + miniature IMUs) | Pointe work remains the biggest accuracy gap (occlusion + extreme plantarflexion). Integrate 2–3 low-cost IMUs (e.g., Xsens Dot, Moveo) on shank/foot with OpenCap/MediaPipe video. Validate vertical GRF and knee moments against force-plate + Vicon during relevé rises and sous-sus landings. | Achieve <8% GRF error and <2.5° valgus error under full pointe load → enables pre-pointe readiness algorithms (critical for 11–14-year-old females). |

| 4 | Dance-specific open-source pose datasets & fine-tuned models | Current models (e.g., COCO-trained) struggle with turnout, hyper-plantarflexion, and costume occlusion. Create publicly available datasets: 200+ hours of multi-view video from elite/pre-professional dancers in leotards, tights, and pointe shoes across genres. Fine-tune state-of-the-art models (HRNet, ViTPose, OpenPose-NG). | Reduce average lower-limb error by 30–40%; democratize access for small studios worldwide. |

| 5 | Integration into existing clinical pathways | Partner with Harkness Center for Dance Injuries, National Institute of Dance Medicine & Science (UK), and Australian Ballet to embed markerless screening into annual health checks and pre-pointe assessments. Develop standardized “Dance ACL Risk Report” (traffic-light system + corrective exercise library). | Seamless transition from research to routine care; target 70% adoption in professional companies by 2030. |

| 6 | Real-time biofeedback systems for technique class | Tablet/smart-TV apps that overlay skeletal pose and instantaneous valgus/turnout metrics during class (e.g., red line when knee passes second toe). Pilot test teacher and student acceptance; measure change in motor learning speed vs. verbal cueing alone. | Shift from periodic screening to daily prevention; addresses IADMS call for “immediate, intrinsic feedback” in training environments. |

| 7 | Longitudinal maturation studies | Track the same cohort of female dancers from age 10–18 with annual markerless assessments + Tanner staging + menstrual cycle tracking. Model how growth spurts and hormonal changes interact with turnout compensation and valgus risk. | Identify critical “high-risk windows” (e.g., 12–14 years) for intensified screening and intervention. |

| 8 | Equity-focused implementation research | Deploy low-cost smartphone systems in under-resourced regions (Latin America, Southeast Asia, rural U.S.) where professional dance training occurs without any biomechanical support. Measure adoption barriers and injury-rate changes. | Address global disparities; many elite dancers now emerge from non-traditional ballet powers. |

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Ambegaonkar, J.P.; Caswell, S.V.; Cortes, N.; Caswell, A.M. Supplemental fitness training in university modern dancers: A pilot study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 2011, 26(4), 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bowditch, L.; Wyon, M.; Redding, E.; Quin, E. The 11+ Dance injury prevention programme: A randomised controlled equivalence trial in adolescent female ballet dancers. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 58(12), 678–686. [Google Scholar]

- Bronner, S.; McBride, C.; Gill, A. Real-time markerless motion capture for contemporary dance: Feasibility and kinematic outcomes. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science 2021, 25(4), 234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Campoy, F.A.S.; Coelho, D.B.; Oliveira, L. Validation of Theia Markerless for ballet jump landings in female dancers. In Sports Biomechanics; Advance online publication; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dufek, J.S.; Bates, B.T.; Mercer, J.A. OpenPose hybrid validation during ballet pliés and relevés in pre-professional females. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2025, 41(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, N.; Gomes, B.; Marques, M.C. Artificial intelligence in dance biomechanics: A scoping review with female dancer validation subsets. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2025, 7, 1345678. [Google Scholar]

- Hauer, R.; Störch, T.; Jäger, M. Feasibility and efficacy of a 12-week neuromuscular training programme in pre-professional ballet dancers. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2022, 43(7), 612–619. [Google Scholar]

- Hutt, K.; Redding, E. The effect of eyes-closed balance training on dynamic balance in pre-professional female ballet dancers: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science 2014, 18(1), 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Dance Medicine & Science. Resource paper: Technique class participation for injured dancers. 2020. Available online: https://iadms.org/resources.

- Kivlan, B.R.; Carcioflo, A.; Nissley, M. Accuracy of OpenCap with inertial measurement units for ballet-specific landings. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 2023, 38(3), 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Liederbach, M.; Dilgen, F.E.; Rose, D.J. Incidence and risk factors for knee injury in professional ballet dancers. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2018, 6(10), 2325967118801576. [Google Scholar]

- Long, A.; Roulet, E.; Redding, E. Effectiveness of a dance-specific injury prevention programme in professional ballet: A 6-month randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 54(15), 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, G.D.; Ford, K.R.; Hewett, T.E. New method to identify athletes at high risk of ACL injury using clinic-based measurements and freeware computer analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 49(6), 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanbeck, A.E.; Russell, J.A.; Handley, M.K. Two-dimensional video analysis of dynamic knee valgus in female ballet dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science 2016, 20(4), 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Quin, E.; Redding, E.; Wyon, M. Neuromuscular training programmes for preventing injuries in youth performing arts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science 2023, 27(2), 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Yoshioka, H.; Kruse, D.W. Turnout in female ballet dancers: A 3-D motion analysis study. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2016, 46(5), 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.J.; Gerrie, B.J.; Harris, J.D. AlphaPose validation for hip internal rotation during grand battement in female ballet dancers. Gait & Posture 2023, 104, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, N.; Tenenbaum, S.; Zeev, A. Lower extremity kinematics during turnout in pre-professional ballet dancers using DeepLabCut markerless motion capture. Sensors 2022, 22(19), 7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojian, T.H.; Nazzal, M. Transformer-based real-time ACL risk prediction in jazz and contemporary dancers. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2024, 71(6), 1890–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, A.X.; Sugimoto, D.; Martin, R. OpenPose validation for sauté jumps in adolescent female ballet dancers. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 2020, 35(3), 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).