1. Introduction

One of the most feared injury types among athletes is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. This type of injury is impossible to predict, the rehabilitation is long and costly [

1] and the probability of re-injury occurrence is extremely high [

2,

3,

4]. The importance of the subject is emphasized by the significant number of articles on ACL tear with many theories explaining the injury phenomenon [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Universally two types of ACL injuries are being distinguished in the literature, contact and non-contact injuries. The majority of sports-related ACL injuries happen in non-contact scenarios, typically involving landing, rapid deceleration, or sudden change of direction [

12], therefore in this paper, we focus on non-contact ACL injuries.

After the inception of the neurocentric bi-phasic injury mechanism of non-contact ACL injury theory [

11], Boden and Sheenan also stressed the relevance of preceding minor perturbation, leading to disruption of the neuromuscular system, prior to ACL injury [

13]. Later, even the microdamage of an ion channel was annoted for the initiation of this primary damage, namely in the form of an acquired Piezo2 channelopathy on the proprioceptive somatosensory nerve terminals [

14]. Noteworthy, that Piezo2 ion channel is the principal mechanosensitive ion channel responsible for proprioception as was demonstrated by the Nobel laureate Ardem Patapoutian [

15]. In addition, Piezo2 is suggested to be the only ion channel capable of initiating an ultrafast long-range proton-based signaling within the nervous system, hence they are primarily responsible for ultradian sensoring and responding to ultradian events [

16]. Accordingly, it has been proposed that axial compression forces induce the preceding neuromuscular disruption by instigating indentation on Piezo2, leading to Piezo2 channelopathy, prior to non-contact ACL injury occurance [

11,

14].

Biomechanically it is universally accepted, that the primary cause of ACL tear is the mechanical overload of the ligament [

5,

10]. There are numerous biomechanical factors, which influence the overload of the ligament, such as extreme force in the quadriceps muscle, extreme ground reaction force (GRF), small knee flexion while landing, intercondylar notch impingement, non-optimal hamstring to quadriceps (H:Q) strength ratio and axial compressive forces on the lateral aspect of the joint [

5,

10,

17,

18,

19].

One of the most frequently occuring mechanism behind ACL injuries is the rotation-pivoting movement of the tibia around its longitudinal axis [

10]. Meanwhile a great number of studies concluded, that the anterior shear force at the proximal end of the tibia incorporated with knee valgus, varus and internal rotation moments results in a pronounced ACL load [

8,

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, a pilot case study showed that the point of attack of the resultant force in the tibia skewed toward the medial proximal tibia during landing [

23]. DeMorat et al. demonstrated the effect of extreme (greater than 4500 N quadriceps force) quadriceps muscle generated anterior shear force at the proximal end of the tibia through the patella tendon on ACL ruptures [

24]. Quadriceps contraction also increases the compressive loads on the tibiofemoral joint, thus contributing to ACL injury [

25]. Additionally, if the knee flexion angle decreases during athletic tasks, the anterior shear force increases that is further exacerbated by higher quadriceps force, which increases the patella tendon-tibia shaft angle, thereby generating more shear force on the tibia [

10].

Knee flexion and abduction angles during the landing phase of a vertical jump play crucial role in ACL injury prevention. Hewett et al revealed that ACL-injured athletes had significantly greater knee abduction angles (8.4°) at landing and higher peak external knee valgus moments, as well as higher peak vertical GRF compared to uninjured athletes. Additionally, significant correlations between knee abduction angle and peak vertical GRF were identified in the injured group. Maximum knee flexion angle at landing was 10.5° less in the ACL injured group. Excessive valgus torques on the knee can increase anterior tibial translation and ACL load, namely if an athlete lands in a dynamic valgus or with unusual foot placement, the likelihood of ACL injury increases [

8,

10,

26,

27]. Another video analysis-based research presented, that the distances from the center of mass (COM) to the point of contact were greater and consequently the angles between thigh and vertical axis were greater, when ACL rupture occurred compared with non-injured landings [

28,

29].

In a sport-specific movement, like landing or deceleration, GRFs are always present. The foot, ankle, knee, hip and muscles around the joints help absorb the reaction forces from the upper body and the GRFs [

5]. Soccer specific jumps often differ from double legged landing actions in other sports as many in game scenarios such as cutting, passing, or landing after a header require athletes to support their full body weight on a single limb [

30]. Kamari et al have been observed greater GRFs, increased knee valgus, and reduced knee flexion at initial contact (IC) during a single leg drop landing compared to a double leg drop landing [

12]. Boden and colleagues through video analysis concluded that individuals, who sustained ACL injury reached the ground with a flat foot or with heels, while control subjects landed on their forefoot [

17]. They concluded that the plantarflexed ankle helps dissipate the forces during landing, thus protecting the ACL. This is important, because when landing with one leg, the peak vertical GRF could reach five to even eighteen times the body weight and as ACL ultimate tensile strength is limited (approximately 2300 N [

31]), landing on a forefoot and using the dampening effect of the ankle is a key aspect in preventing ACL rupture.

By viewing numerous video recordings of ACL injuries of soccer players during match situations we have concluded that another mechanism with very specific parameters might also be responsible for the frequent occurrence of the injury, especially concerning soccer players. In many cases the injury occurs in the landing phase, when executing a jump the foot contacts the ground. In the cases that we have observed while analyzing the movements of the athletes, before the injury at landing pivoting of the knee, namely rotation of the tibia around its longitudinal axis was not distinguishable, but in the landing phase, immediately before contact with the surface, the knee was in an extended and the thigh was in an abducted position viewed from the frontal plane. At IC, when deceleration of the body would occur, sideways slippage (accidental mishap) of the foot was visible as viewed from the frontal plane, away from the body followed by abnormal abduction of the knee joint and the collapse of the athlete, universally distinguished in the literature as knee valgus collapse. We believe that if this type of movement pattern is recognizable, then the traction parameters of the soccer field could influence ACL injury incidence probability. Our hypothesis is highlighted by the fact that ACL injuries almost always happen in game situations - when the soccer field is usually being treated extensively with water to create a more slippery surface to increase the speed of the game - and very rarely at trainings. This hypothesis comprises that the aforementioned Piezo2 ion channels are stretch and force gated [

32], beyond being an ultradian sensor [

16]. Therefore, the slippery surface may not only increase axial compression forces and in response a point of attack of the resultant force in the medial proximal tibia during landing, but induce over-excessive stretch (mimicking an over-excessive eccentric contraction) and resultant contribution to the aforementioned theorized microdamage of Piezo2 (failure to functionally activate). Correspondingly, this acquired Piezo2 channelopathy could result in a sensory mismatch. This mechanism not only could explain the impaired response to perturbations, but also could explain that these non-contact injuries primarily happen in game situations when ultradian sensoring may be overloaded due to elevated acute stress situations. Accordingly, this is how the axial compression forces could induce Piezo2 channelopathy in encapsulated large fiber terminals of the medial part of the proximal tibia [

14] and how the preceding neuromuscular disruption could evolve by not only the instigated indentation, but excessive stretch of intrafusal Piezo2 on affected proprioceptive terminals, leading to Piezo2 channelopathies, prior to the non-contact ACL injury occurance.

The above introduced injury mechanism, body position, lower extremity position might sound unnatural, but there are some influencing factors that should be taken into consideration. Jumps during a sport event are fundamentally different compared with vertical jumps examined in a laboratory environment using 3D movement analyzing systems [

33]. In a game situation the landing is almost never symmetrical for the two legs neither concerning the position, nor the distribution of GRF for the two legs. The movement of the COM, the trajectory of the movement is almost never vertical, usually there is a horizontal element, consequently at the landing phase the athlete’s body possesses a horizontal velocity component. We must also consider the surrounding elements, as contrary to an isolated laboratory environment, many external inputs, afferent signals of proprioceptors must be processed by the central nervous system, consequently optimal landing posture might not always be achievable.

2. Materials and Methods

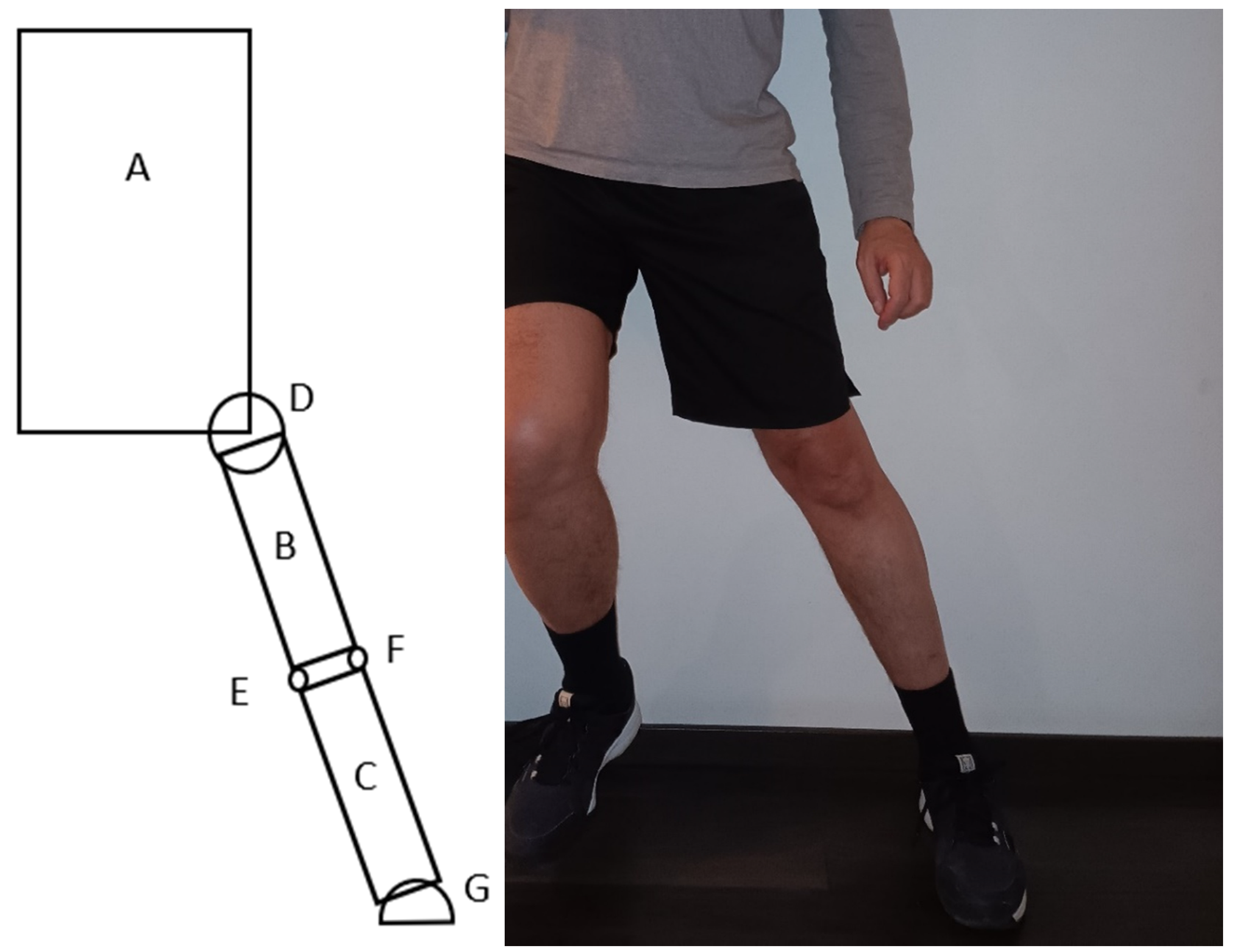

To understand the biomechanical properties of the mechanism we introduce in this paper, we will use a simplified model of the human body. In our model the following objects represent the body elements: A - trunk; B – thigh; C – shin; D – hip joint; E – medial condyle of the knee; F – lateral condyle of the knee; G - ankle and foot (

Figure 1). In

Figure 1 our model on the left drawing represents the athlete in the frontal plane observed from the front, at the beginning of contact with the surface in the landing phase of a jump. In

Figure 1 on the right the real athlete is visible taken as a schematic reference for the drawing. It is important to highlight, that based on postures we have observed in numerous video recordings the thigh is in an abducted position and the knee is fully extended. The other leg is not visible on the left drawing in

Figure 1, as that leg only makes contact after the indicated leg – where the ACL injury would occur – and consequently does not have a significant role in the injury mechanism we discuss.

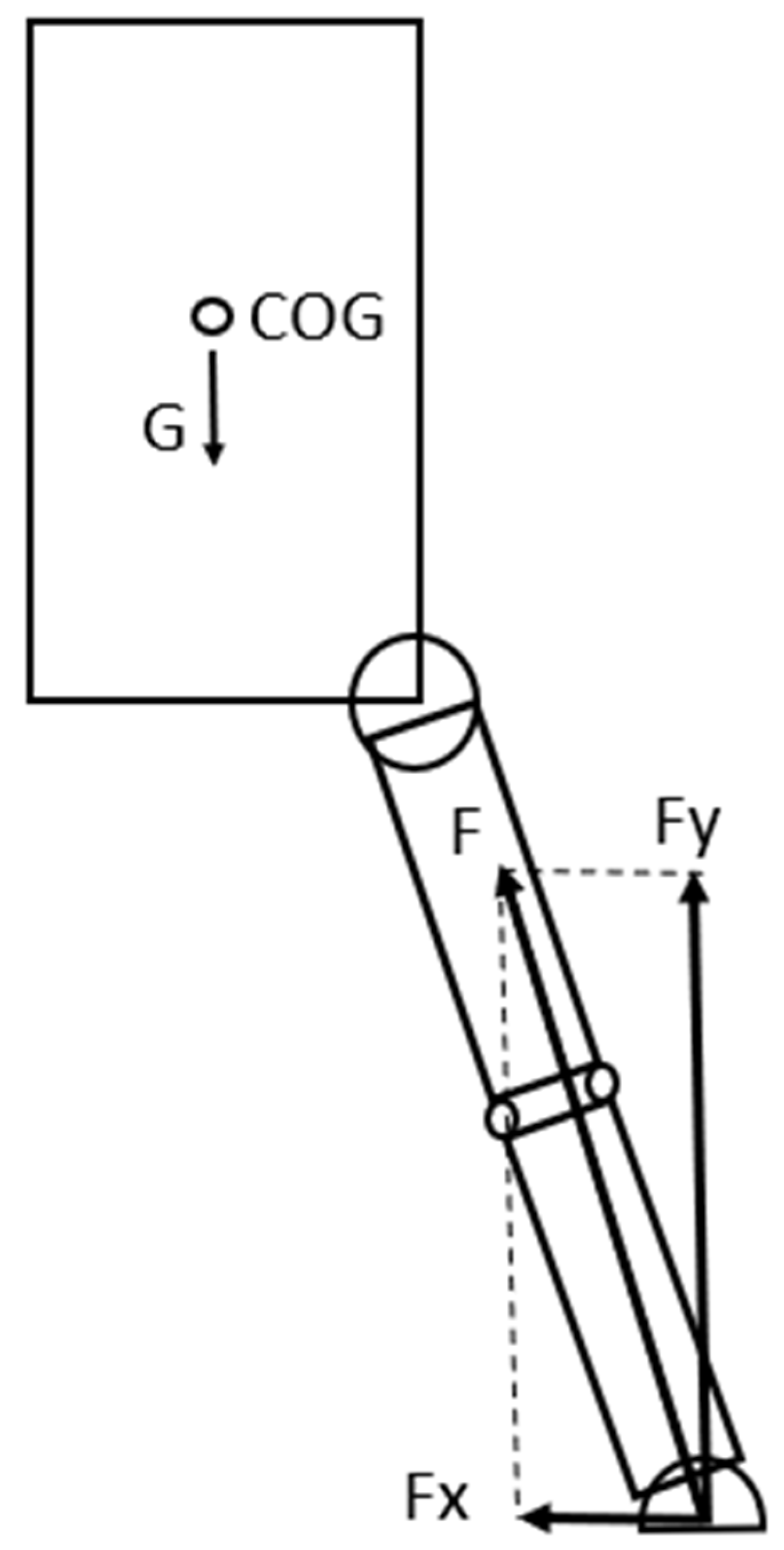

In this situation there are two major external forces acting on the athlete: the gravitational force -G - acting in the COG (technically similar to COM) for the individual and the GRF. For the purpose of our later analysis, the GRF can be split into horizontal – Fx – and vertical – Fy – components (

Figure 2). (This set-up of the acting forces is universally used in sport movement analysis). After an execution of a vertical jump in the landing phase the net GRF can be 5-10 times greater or more than the gravitational force.

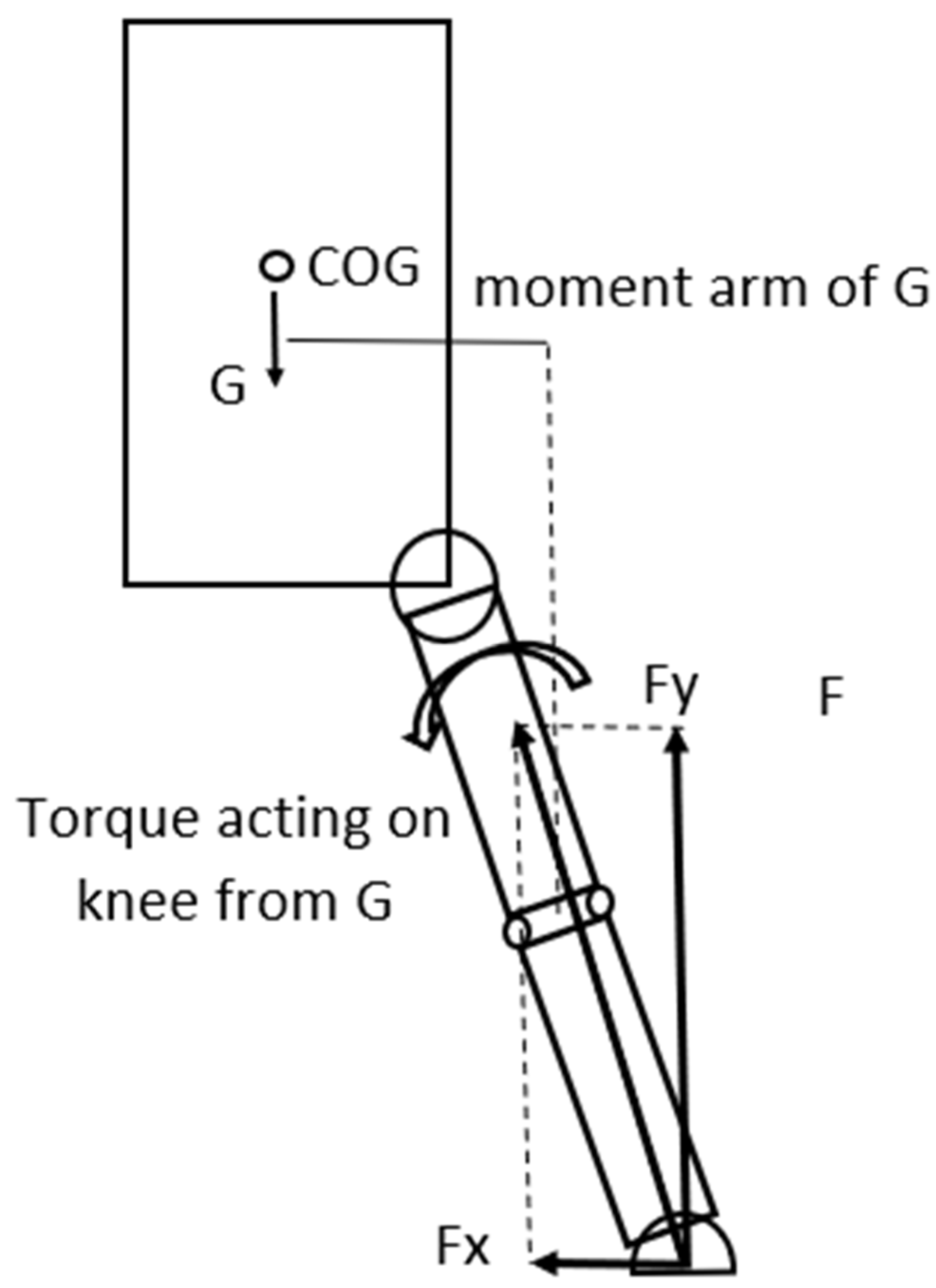

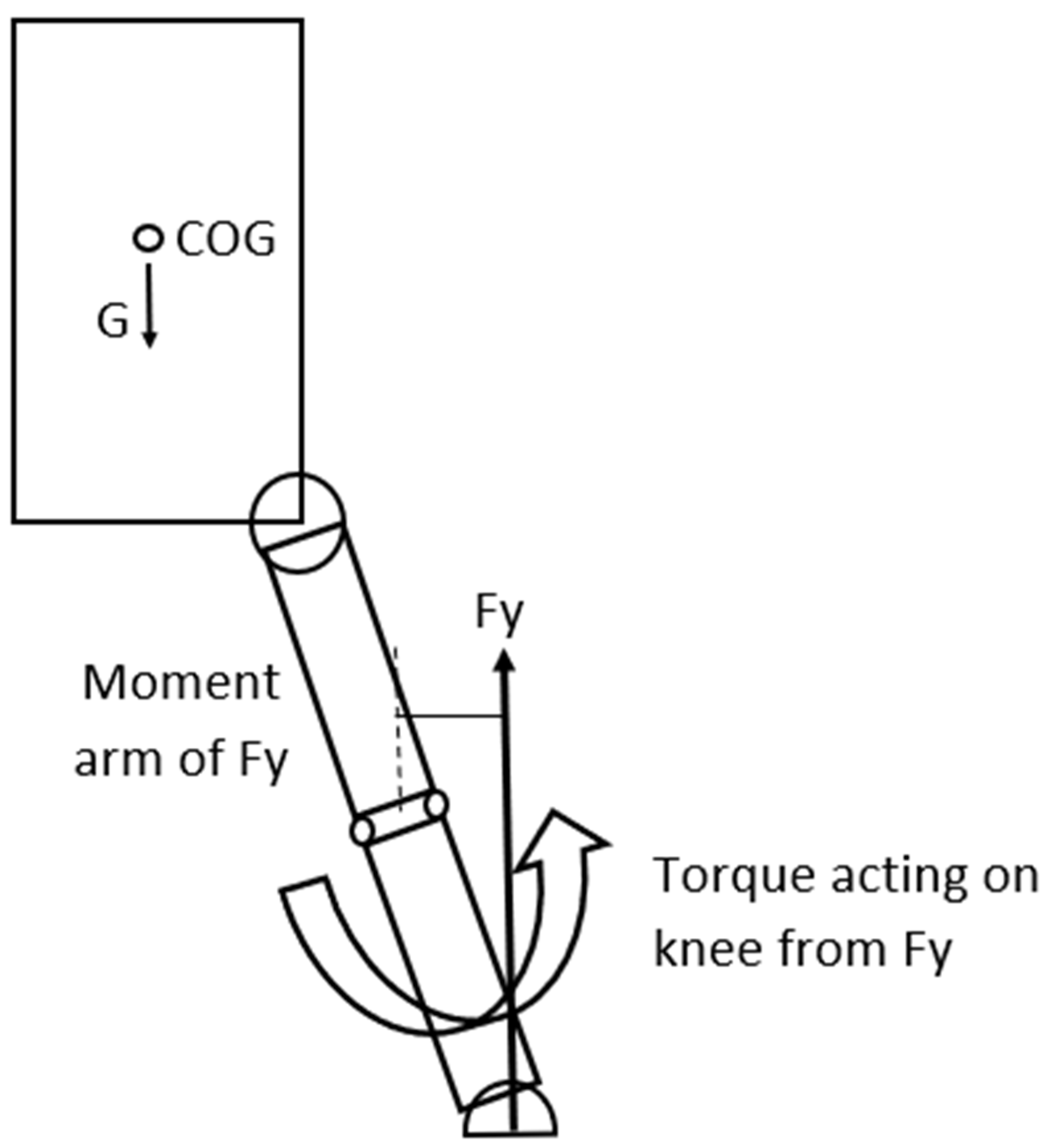

By using our model, we can identify a torque acting on the knee from the gravitational force that is trying to rotate the trunk and the thigh around the knee in a counter-clockwise direction in the frontal plane (

Figure 3). If we analyze the model in detail, based on the structure of the knee and considering, that the knee is in an extended position in the model, we can conclude that the torque originating from the gravitational force is trying to rotate the thigh around the medial condyle of the knee joint. In this position the joint surfaces-the medial and lateral condyles act as axes for the knee joint and around these axes minimal abduction and adduction of the knee can occur. As Fx is present, the orientation of the GRF is not vertical but pointing more-or less towards the knee, consequently the torque from the GRF acting on the knee can be considered as minimal (

Figure 3). In this case the load on the ACL is not extreme therefore injury is not expected to happen.

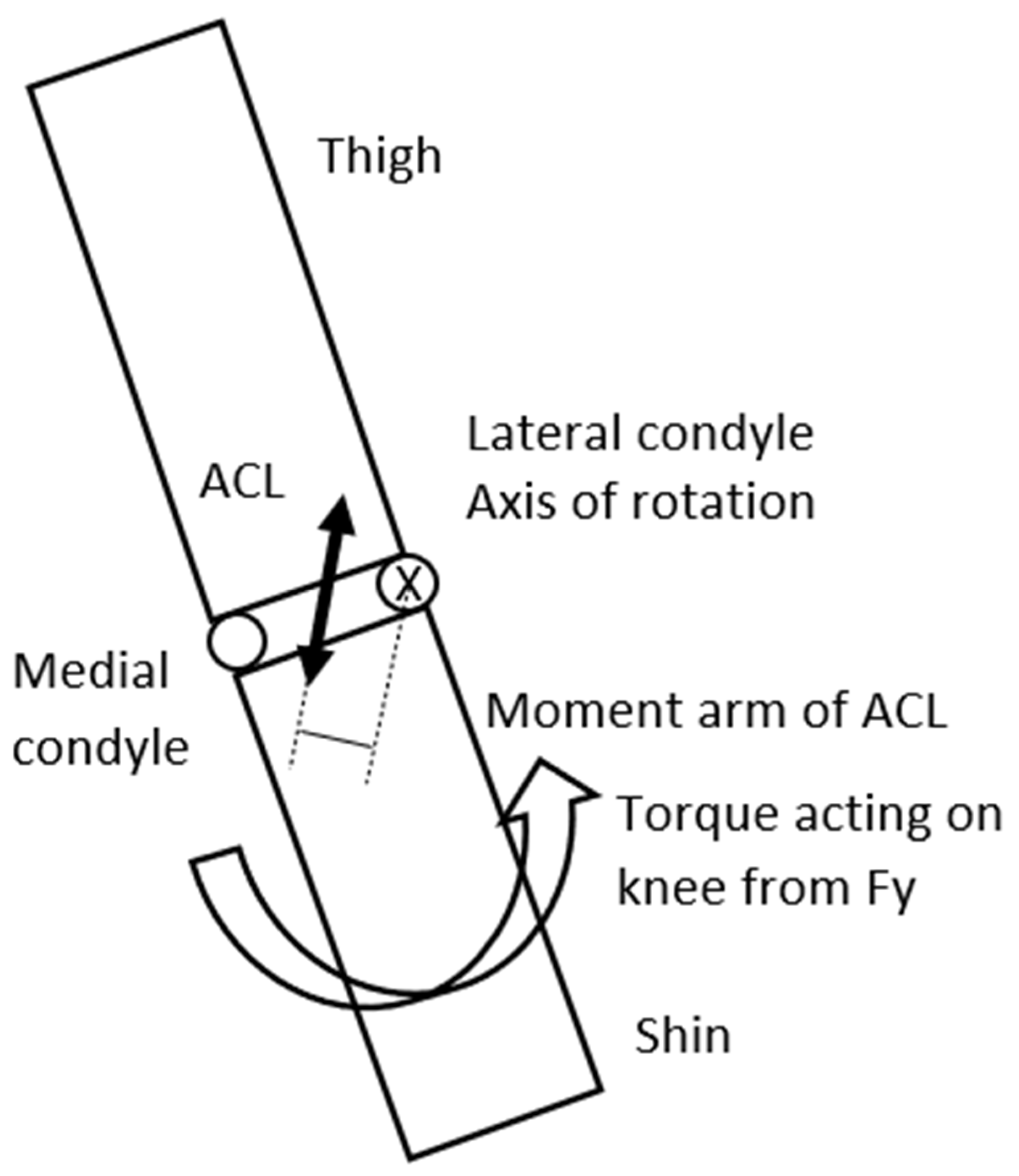

In this landing situation if the surface is slippery, that significantly affects the load on the knee. In a slippery surface the horizontal component of the GRF is minimal, or if the foot of the athlete slips or slides sideways at contact this horizontal force component (Fx) can even be zero. Consequently, only the vertical component of the gravitational force is present, which will create – as the Fy can still be 5-10 times greater, or more than the gravitational force, (partially because as we have observed in the video recordings, in the cases the knee is in an almost entirely extended position) - a significant torque acting on the knee, which torque will try to rotate the shin around the knee in a clockwise direction (

Figure 4). As Fy is significantly greater than G – especially if the knee is in an extended position – the torque originating from the GRF can also be significantly greater acting on the knee. This torque will rotate the shin around the lateral condyle of the knee joint consequently generating significant load on the ACL. In an extreme situation this load can exceed the mechanical tensile strength of the ACL and injury will occur in the ligament [

31] (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

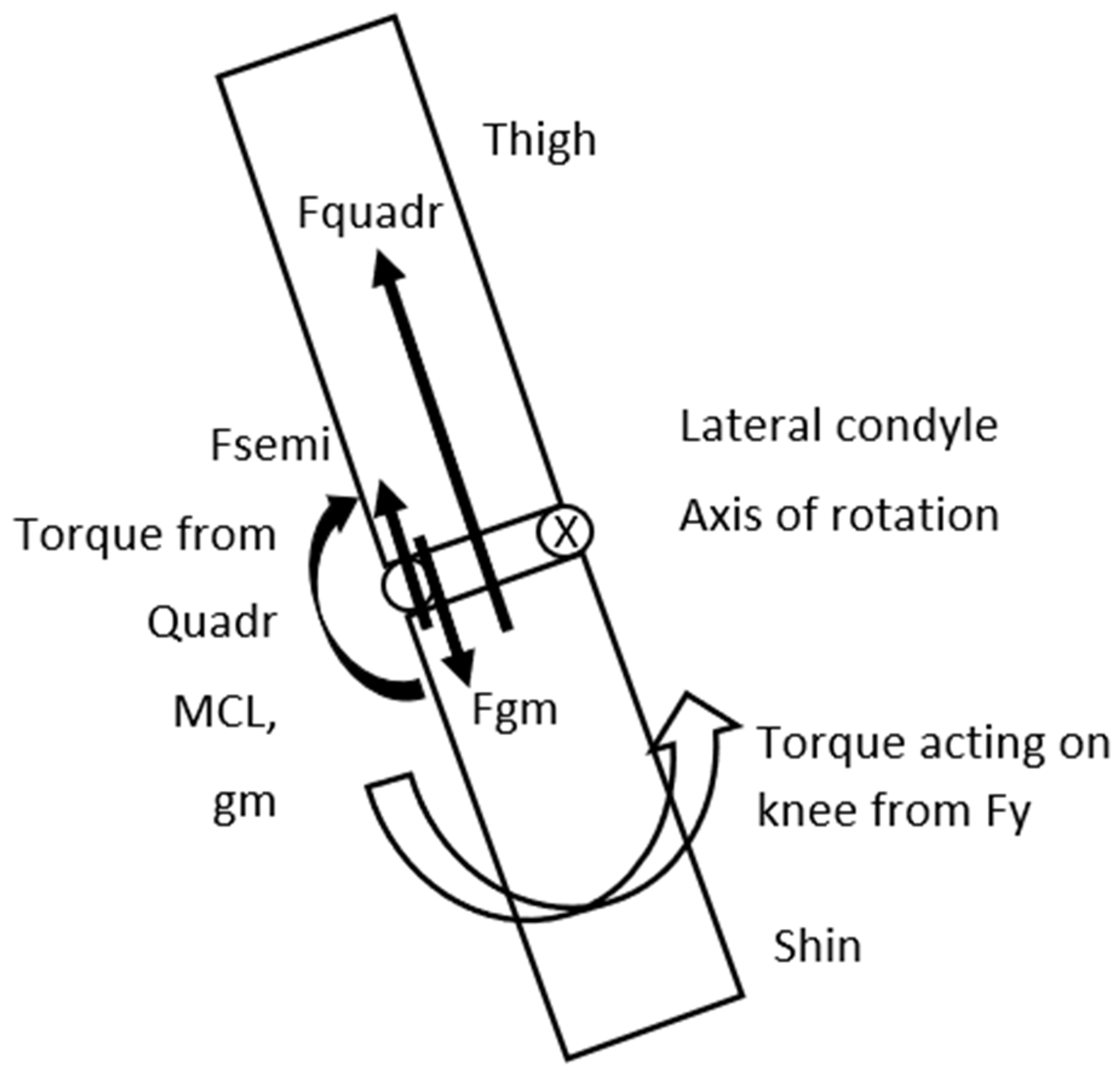

There is a passive and an active mechanism that can decrease the abduction of the knee and therefore the stress on the ACL in this model. The passive tension originating from the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the active tension originating from the quadriceps pulling the tibia through the quadriceps-patella-patellar tendon towards the femur, the semitendinosus-semimembranosus also pulling the tibia towards the femur, and the gastrocnemius medialis pulling the femur towards the tibia. As the knee rotates around the lateral condyle previously defined as the axle of abduction, the MCL will stretch and can take over some of the load on the ACL. This theory is supported by the fact, that in many cases when ACL tear happens, MCL damage can also be observed [

34]. But when the ACL completely tears, in many cases the MCL will partially remain intact, therefore it can be speculated, that the load transfer from the ACL to the MCL is limited. The ultimate tensile strength of the MCL according to a study is 799±209N [

35].

The activation level and consequently the tension in the quadriceps, semitendinosus-semimembranosus complex soleus and the gastrocnemius medialis significantly affect ACL load, because if the knee is in an extended position, and torque as a result of extreme Fy will act on the knee and generate an abduction effect, and consequently rotation will occur around the lateral condyle, based on the anatomical structure of the knee the tension of these muscles will decrease the torque of Fy and decrease abduction [

36]. (

Figure 6).

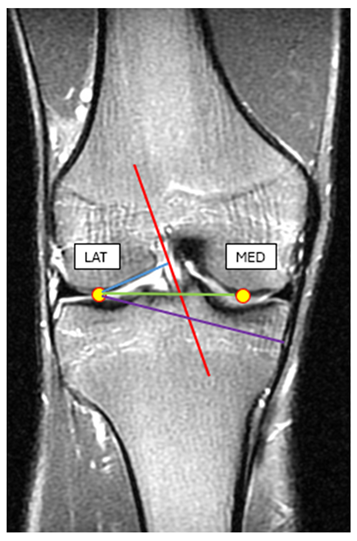

Ethical Issues: To acquire the required anthropometric values of the knee that were used for the mathematical model we have analyzed the geometric parameters of MRI images of athletes previously recorded by medical professional personnel in a Hungarian medical facility (Kaposi Mór Oktató Kórház-Kaposvar city medical Hospital, Hungary). The individuals were athletes of the Hungarian Handball Academy (NEKA) with signed consent documents to approve the evaluation of the recorded data. From the acquired images we have only determined the required geometric values and no medical evaluation was executed. The study was approved by the Science Ethic Committee of the Hungarian University of Sports Science, Ethical Approval Number: TE-KEB/18/2022.

3. Results

To acquire more insight into the injury mechanism we have discussed and introduced above, we have created a mathematical model to calculate the torques in the knee. We must highlight, that although some parameters can be measured directly, for some parameters we had to rely on previous research results from different sources. In some cases, we decided to use the maximum values available in the literature to draw a conclusion while maintaining a conservative approach. For other anatomical values that we could not find in the literature we have processed previously recorded MRI images of athletes.

Factor responsible for the torque generating abduction around the lateral condyle: GRF at landing – GRF- lateral condyle moment arm. Factors responsible for the torque generating adduction around the lateral condyle: ACL stress – ACL-lateral condyle moment arm; MCL stress– MCL- lateral condyle moment arm; Patellar tendon (PT)/quadriceps stress – patellar tendon- lateral condyle moment arm; Semitendinosus stress (SEMIT) – semitendinosus- lateral condyle moment arm; Bodyweight – COG-lateral condyle moment arm.

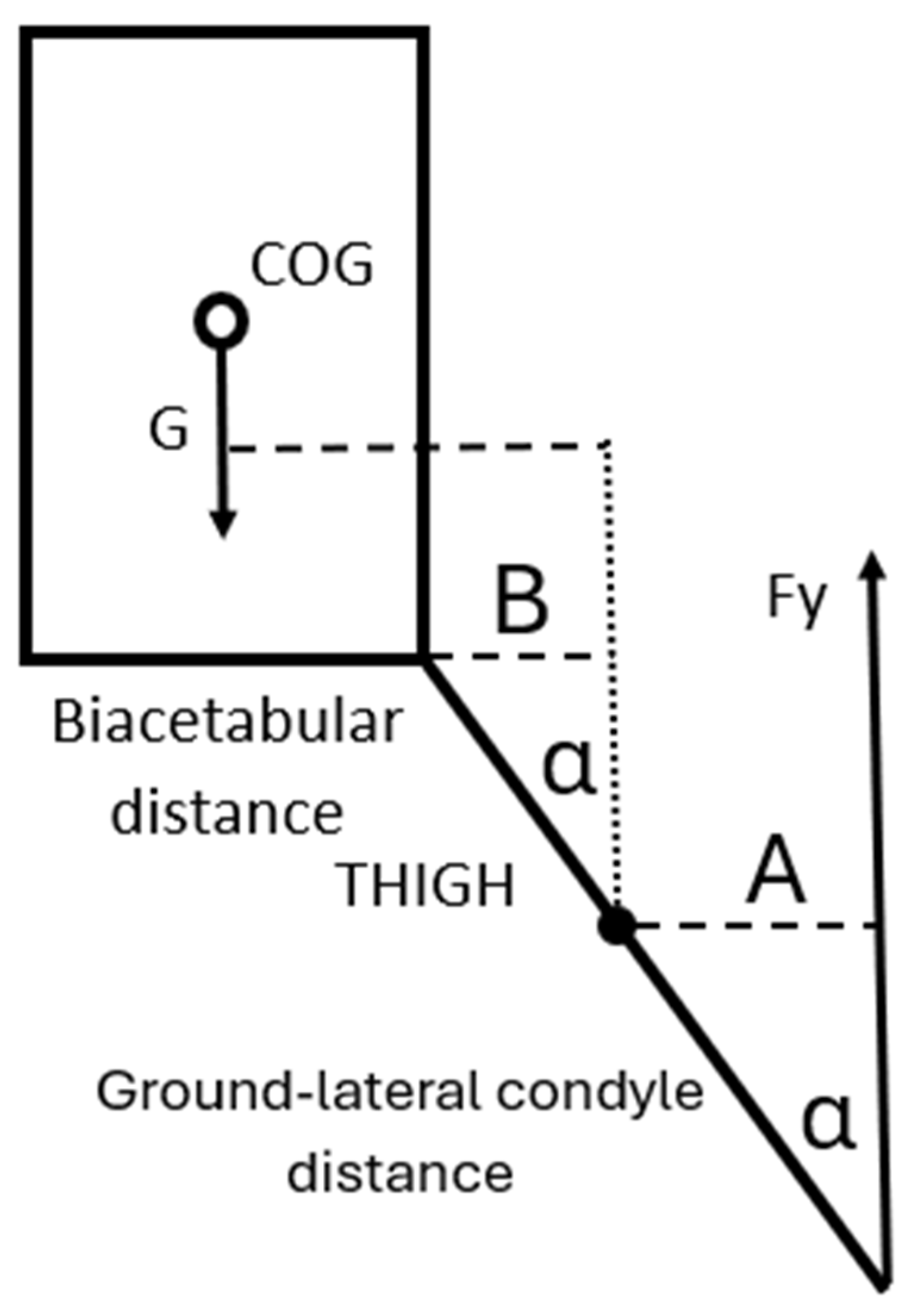

We have created formulas to calculate the torques acting on the lateral condyle in a one-legged landing situation with assuming the sliding of the foot in the case of no traction, if the rotation around the lateral condyle is present as previously described in the mechanism above. The angle α represents the angle between the lower extremity and the vertical line (

Figure 7). In the model we hypothesize that the trunk is in a vertical position.

Torque generating abduction around the lateral condyle: (Fy ▪ lateral condyle moment arm)=(Fy ▪ Ground-lateral condyle distance ▪ (sinα)), where α is the angle of the shin measured from the vertical line.

Torque generating adduction around the lateral condyle: (ACL stress ▪ ACL-lateral condyle moment arm) + (MCL stress ▪ MCL- lateral condyle moment arm) + (Patellar tendon stress ▪ patellar tendon- lateral condyle moment arm) + (Semitendinosus stress ▪ semitendinosus- lateral condyle moment arm) + (Bodyweight ▪ COG-lateral condyle moment arm) - where each moment arm reflects to the appropriate force respectively.

We intended to determine the angle of the shin measured from the vertical line (α) at which the ACL (and other components) would reach the point of a high risk of injury as the function of Fy. To calculate this angle, we have determined when the torques responsible for abduction are equal with the torques responsible for adduction around the lateral condyle. We have decided to use a conservative approach therefore we have used the maximum values we have found in the literature for the force generating capabilities of the muscles for young healthy adults and the maximal stress the ligaments can withstand without damage (

Table 1).

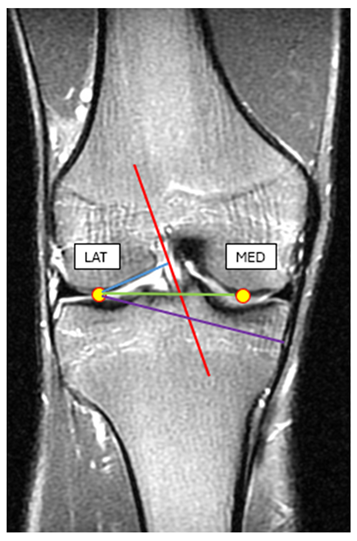

To reach our goal we have also collected MRI images and anthropometric data of 15 healthy male individuals (age 19-23, BW=80.2±6.8kg). In the MRI images of the knee we have identified the lateral and the medial condyles and using the MRI image software (RadiAnt DICOM Viewer) measured the lateral condyle-ACL distance, lateral condyle-MCL distance, lateral condyle-medial condyle distance (Picture 1.). For the required anthropometric data, we have measured the ground-lateral condyle and the lateral condyle-greater trochanter distance respectively (Picture 1,

Table 2).

Using the measured data and data obtained from previous research material we have calculated the net torque acting on the lateral condyle in a one-legged landing as the function of the angle between the shin and the vertical line as described in the model. We hypothesize that if the torque originating from GRF resulting in abduction is greater, than the torques that act as adductors, then the risk of an injury in one of the components that is responsible for the adduction is significant. Consequently, we have calculated the GRF as the function of the angle where the abduction and adduction torques are equal (angle of damage) by using the measured values in the formula below:

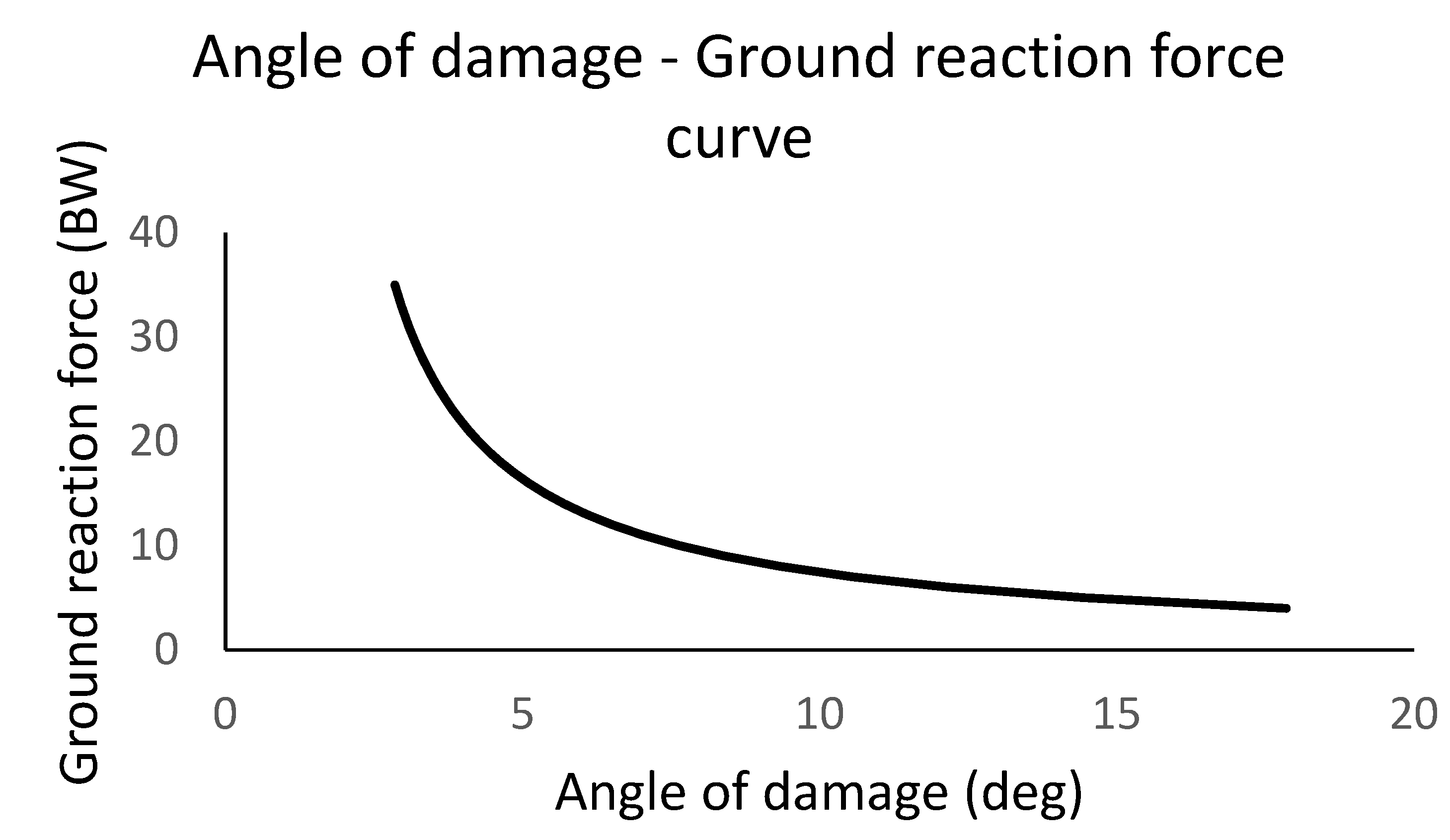

Fy▪0.59486▪sin(α)=2300▪0.02606+799▪0.0688+8000▪0.05846:2+1604▪0.0688+802▪(0.12378+0.4618▪sin(α)) where GRF, ACL, MCL, PT, SEMIT, COM torques acting on the lateral condyle were determined respectively. The GRF-angle of damage curve is visible on

Figure 8. If the GRF at a given landing angle is greater, than the value on the graph, then based on the model the risk of injury is significant. In the graph it is clearly visible, that as the angle between the shin and the vertical line increases during landing, smaller GRF magnitudes can result in an ACL injury.

4. Discussion

By analysing our results, we agree with numerous studies, that knee valgus increases the risk of abduction torques and the risk of an ACL injury [

10]. Our results are in concordance with Hewett et.al [

8], as the model indicates that trunk position affects adduction torques, namely trunk lean angle influences the COG moment arm from the knee. We must emphasize that the landing posture we have discussed is highly unfortunate for the ACL. In normal circumstances at landing the significant GRF is being dampened by the collective flexion of the hip-knee-ankle joints. However, if the knee is fully extended and the thigh is in an abducted position during landing, then the dampening effect in the knee and the hip is restricted. Furthermore, by using the model we have identified for a given shin angle a minimal GRF value, and concluded that if this value is exceeded, the risk of injury in the ACL is substantial. We must emphasize that although in the literature ACL injury is associated with knee valgus, our hypothesis for the injury mechanism is in concordance of the model calculation of Hinckel et al., who concluded that if the knee is in an extended position, minimal changes in varus and consequently abduction angle will result in significant increase in stress on the ACL [

41].

One notable factor to consider is that as the force generating properties are significantly greater in the quadriceps - this is evident based on the thoroughly discussed H to Q strength ratio in the literature [

42] – the activation level of the quadriceps is a crucial factor. Any disturbance in the activation either as a result of a previous injury, delayed activation, disturbance in the proprioception, or fatigue either in the muscle cells or in the neural system will decrease the above mentioned compensation effect of the quadriceps and the load on the ACL will be greater [

5,

10]. We must emphasize that the time factor in obtaining a high quadriceps muscle activation level in our model at landing is crucial. Therefore, there is very limited time available for the quadriceps to develop the proper amount of tension that could compensate the torque of the GRF, consequently minimal perturbation in the force-development parameters might result in the injury. This is in line with the observation that delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), also theorized to be initiated by proprioceptive terminal Piezo2 channelopathy [

16], alters the response to postural perturbations [

43].

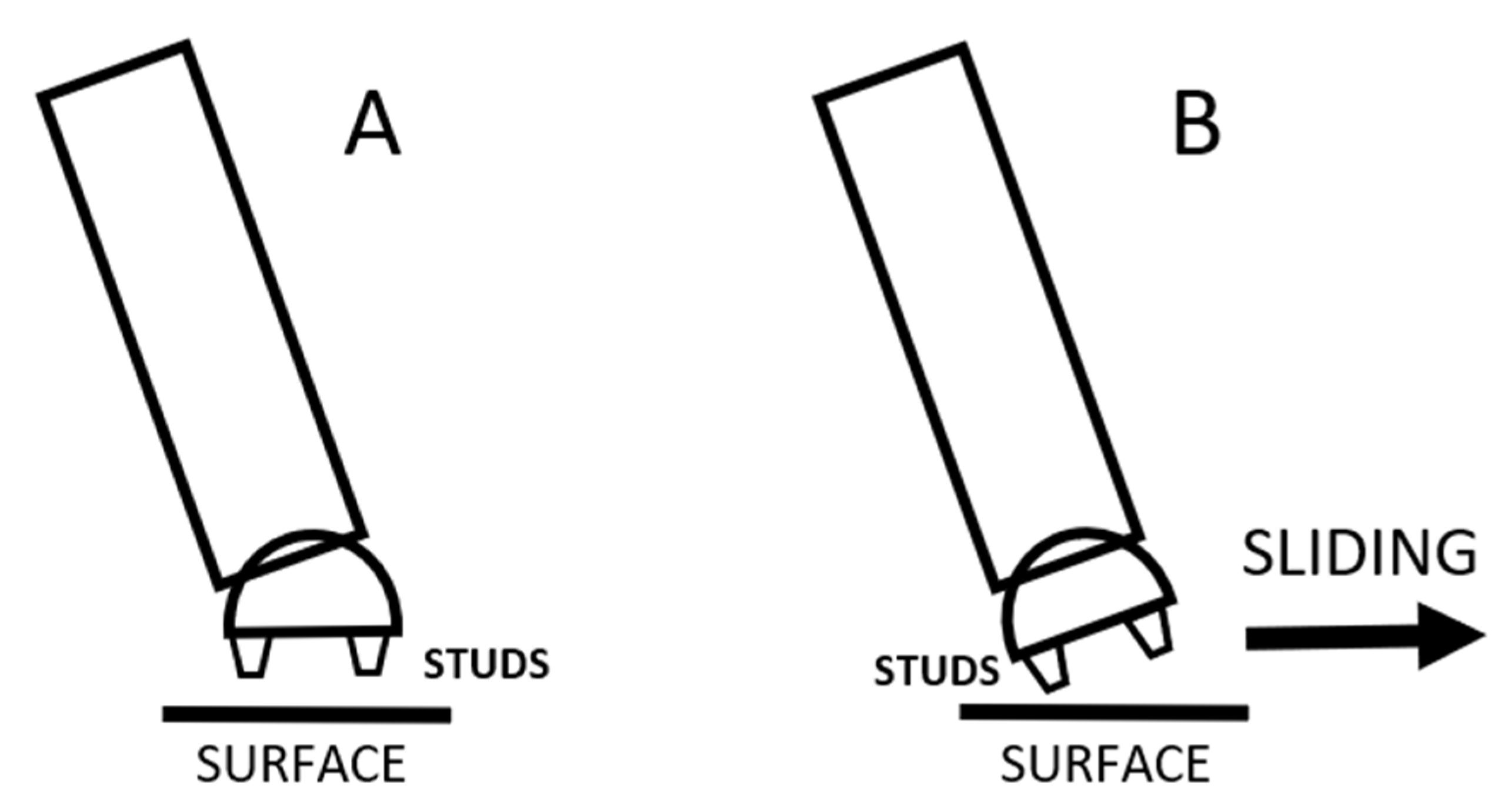

We hypothesize, that the traction parameters of the surface have extreme importance in this injury mechanism. If the surface is less slippery the Fx component of the GRF will be greater and the net GRF torque acting on the knee will be smaller. Concerning the traction parameters while landing, the position of the ankle and the foot significantly affects the horizontal movement of the leg. Concerning soccer, the shoe is equipped with studs, with the basic role to provide sufficient contact and traction with the surface. But if the landing occurs when the angle of the shin deviates from the vertical in the frontal plane, then contact and consequently traction might not be optimal. Two scenarios should be considered. If there is an angle in the shin from the vertical as mentioned above, then one possibility is that the ankle is in a supinated position paired with dorsal flexion. This way the foot can be parallel with the surface at landing consequently the studs of the shoe can generate grip on the ground and traction will be sufficient (

Figure 9A). The problem with this scenario is that because of the previously mentioned dorsal flexed position of the ankle at landing, the dampening effect of the ankle is limited, therefore the GRF will be greater. Consequently, although Fx will be present, the vertical Fy component of the GRF will be extreme and the abduction torque on the lateral condyle of the knee will also be significant. In the other scenario no supination occurs in the ankle and the foot is not parallel with the surface at contact. In this case the possibility of the sideways sliding movement of the foot at contact increases, as the studs are not able to provide sufficient grip and traction with the ground. Consequently, Fx will be significantly smaller or none and in this case also the abduction torque on the lateral condyle of the knee will be significant (

Figure 9B). The probability of occurrence of this scenario increases as the angle of the shin from the vertical observed from the frontal plane increases.

Moreover, while discussing the injury mechanism with professional soccer players every individual highlighted, that as the match progresses moisture buildup inside the shoe at the heel is significant as the consequence of water on the field and the capillary effect of the socks. This phenomenon increases the medial-lateral (sideways) sliding effect of the heel inside the shoe. The structure of the soccer shoe is also not in favor of stabilizing the heel as, compared to a basketball shoe, the shoe leaves the ankle open providing minimal -if any- support for the ankle. This is necessary to enable extensive plantar-dorsal flexion, and also significant supination-pronation movement of the foot for kicking tasks, but also results in minimal support for the ankle joint and for the heel. Consequently, a sideways slide of the heel inside the shoe can occur, even if the contact of the shoe with the ground using the studs provides adequate grip at landing. If a sideways slide of the heel occurs inside the shoe the effect is similar to the one discussed and represented above in

Figure 9B.

Furthermore, it is worth mentioning, that although the model did not count for the initial abduction angle between thigh and shin [

44] it can be hypothesized, that if this abduction angle is greater than the phenomenon discuss above, would result in a greater risk of injury.

As a molecular explanation, a recent traumatic brain injury (TBI) research showed the critical contribution of PIEZO2 in the defensive arousal response (DAR) [

45]. Noteworthy that mild TBI is implicated to have an analogous bi-phasic non-contact injury mechanism, like in the case of non-contact ACL injury and DOMS, where the primary damage could be an acquired proprioceptive neuron terminal Piezo2 channelopathy as well [

16]. This DAR mechanism is essential for survival, and it is activated by a perceived threat and evoked by visual and auditory cues in the presence of motor abilities [

45]. Moreover, DAR could be analogous to ASR that is part of the neurocentric non-contact ACL injury [

11,

14] and DOMS theory [

16] and might be often induced during game situations. A new preprint manuscript underpins the proton-based ultrafast matching/synchronization of the Piezo2-initiated eye–brain, auditory/vestibular–brain, and proprioceptive muscle–brain axes within the hippocampal hub [

46], in line with the aforementioned DAR mechanism. Moreover, Pedemonte et al. showed earlier that sensory processing could be temporally organized by ultradian brain rhythms in addition to the temporary synchronization of the heart rate, medulla firing and the hippocampal theta rhythm under a homeostatic state [

47,

48]. Accordingly, it has been proposed that the beforementioned TBI genetic study may underscore Piezo2’s ultrafast ultradian sensory and ultradian rhythm generation function [

49] and that Piezo2 channelopathy is why DOMS alters the response to postural perturbations [

43] and significantly increases the medium latency response of the stretch reflex [

50]. In support, another recent preprint research paper demonstrated that the speed of current activation was significantly slowed in neurons from

Piezo2+/- and

Piezo2-/- embryos, such as the latencies for current activation as well, as opposed

Piezo2+/+ neurons [

51]. Moreover, the same study showed that the inactivation kinetics of all mechanically-gated currents were also slowed by 2.5 to 5-fold from

Piezo2+/- and

Piezo2-/- neurons, in contrast to the ones from

Piezo2+/+ neurons [

51]. These findings not only support the theorized ultrafast sensory function of Piezo2 [

16], but also underpins the principality of Piezo2 in the mechanotransduction of proprioception, as Ardem Patapoutian and his team reported [

15]. However, it is important to highlight that other ion channels also contribute to proprioception, but the current authors propose that Piezo2 is the only one providing the ultrafast fine control of proprioception as part of ultradian sensoring, reflected in its aforementioned principality.

Therefore, Piezo2 function under DAR/ASR are analogous to the proposed underlying Piezo2-initiated proton-based ultrafast ultradian hippocampal backbone of brain axes, including the bone-brain and muscle-brain axes in the current scenario that are temporarily organized to hippocampal theta rhythm

. However, Piezo2 channelopathy impairs this fine regulated Piezo2 initiated ultrafast ultradian hippocampal organization due to over-excessive axial compression forces. As a result, this acquired Piezo2 channelopathy could induce a somatosensory switch/miswiring and resultant mismatch, exaggerated quadriceps contractions and delayed static phase firing encoding that puts greater load on the ACL [

11,

14]. Furthermore, this microdamage of Piezo2 also lessen the ability to react to ultradian events, especially perturbations, e.g. slippery surface and sliding, hence making the ACL prone to injury. Accordingly, ultrafast reactiveness to perturbations of Piezo2 may come from quantum mechanical properties, where Piezo2 initiates the ultrafast proton-based long-range signaling, but acquired Piezo2 channelopathy is suggested to impair this ultrafast capability, leading to increased injury risk [

16].

Limitations of the study. To acquire proper data for the model we relied on data from previous studies concerning muscle force values, ligament tensile strength values. We must also highlight that we have used video recordings of non-contact ACL injuries during match situations for the preliminary idea for this paper. As we were not able to use 3-dimensional movement analysis data, therefore our model is not supported by this technology.

Figure 1.

Model of an athlete in the frontal plane viewed from the front in the moment of landing on the surface with one leg (left), the athlete for reference (right). Objects in the model: A - trunk; B – thigh; C – shin; D – hip joint; E – medial condyle of the knee; F – lateral condyle of the knee; G - ankle and foot.

Figure 1.

Model of an athlete in the frontal plane viewed from the front in the moment of landing on the surface with one leg (left), the athlete for reference (right). Objects in the model: A - trunk; B – thigh; C – shin; D – hip joint; E – medial condyle of the knee; F – lateral condyle of the knee; G - ankle and foot.

Figure 2.

External forces acting on the athlete in the model when contact with the surface occurs after a jump: G – gravitational force; F - ground reaction force; Fx – horizontal component, Fy – vertical component of the ground reaction force.

Figure 2.

External forces acting on the athlete in the model when contact with the surface occurs after a jump: G – gravitational force; F - ground reaction force; Fx – horizontal component, Fy – vertical component of the ground reaction force.

Figure 3.

The gravitational force acting on the COG creates a torque around the knee that rotates the trunk-hip system in a counter-clockwise direction around it.

Figure 3.

The gravitational force acting on the COG creates a torque around the knee that rotates the trunk-hip system in a counter-clockwise direction around it.

Figure 4.

The GRF creates a torque around the knee that rotates the shin in a counter-clockwise direction increasing abduction.

Figure 4.

The GRF creates a torque around the knee that rotates the shin in a counter-clockwise direction increasing abduction.

Figure 5.

Shin and thigh viewed in the frontal plane from the front. To partially counter the torque and rotating effect of the GRF around the lateral condyle of the knee – that is the axis of rotation, tension is developing in the ACL that will generate a torque in the reverse direction.

Figure 5.

Shin and thigh viewed in the frontal plane from the front. To partially counter the torque and rotating effect of the GRF around the lateral condyle of the knee – that is the axis of rotation, tension is developing in the ACL that will generate a torque in the reverse direction.

Figure 6.

Shin and thigh viewed in the frontal plane. Fy (vertical component of the GRF) will generate a torque to rotate the shin around the lateral condyle of the knee creating abduction. The force of the quadriceps – Fquadr; semitendinosus, semimembranosus force – Fsemi, force of the Gastrocnemius Medialis - Fgm and the stretch of the MCL will reduce this torque, creating an adduction effect consequently decreasing load on the ACL.

Figure 6.

Shin and thigh viewed in the frontal plane. Fy (vertical component of the GRF) will generate a torque to rotate the shin around the lateral condyle of the knee creating abduction. The force of the quadriceps – Fquadr; semitendinosus, semimembranosus force – Fsemi, force of the Gastrocnemius Medialis - Fgm and the stretch of the MCL will reduce this torque, creating an adduction effect consequently decreasing load on the ACL.

Figure 7.

To determine the abduction torque of Fy for the knee the moment arm is A=Ground-lateral condyle distance ▪ (sinα); the moment arm of G is Biacetabular distance/2 + B= Biacetabular distance/2 + THIGH ▪ (sinα).

Figure 7.

To determine the abduction torque of Fy for the knee the moment arm is A=Ground-lateral condyle distance ▪ (sinα); the moment arm of G is Biacetabular distance/2 + B= Biacetabular distance/2 + THIGH ▪ (sinα).

Figure 8.

The graph represents the angles of the shin from the vertical line (angle of damage) at the initial contact at landing as the horizontal axis value and the ground reaction force is multiplied by body weight (m▪g) as the vertical axis value. The curve indicates, that if the ground reaction force at a given landing angle is greater than the value of the curve, then based on the model the risk of injury in the ACL is significant.

Figure 8.

The graph represents the angles of the shin from the vertical line (angle of damage) at the initial contact at landing as the horizontal axis value and the ground reaction force is multiplied by body weight (m▪g) as the vertical axis value. The curve indicates, that if the ground reaction force at a given landing angle is greater than the value of the curve, then based on the model the risk of injury in the ACL is significant.

Figure 9.

The shin and the foot of the athlete in the frontal plane in the moment of landing, also indicating the position of the studs. In A the foot is parallel with the surface and the studs provide adequate grip, while in B as the foot is not parallel with the surface the possibility of sliding of the foot at landing increases.

Figure 9.

The shin and the foot of the athlete in the frontal plane in the moment of landing, also indicating the position of the studs. In A the foot is parallel with the surface and the studs provide adequate grip, while in B as the foot is not parallel with the surface the possibility of sliding of the foot at landing increases.

Table 1.

Data of mechanical properties of various components from previous literature for the model. For the data source was used with samples consisting of young healthy adults.

Table 1.

Data of mechanical properties of various components from previous literature for the model. For the data source was used with samples consisting of young healthy adults.

| Variables from literature* |

ACL max stress |

MCL max stress |

Quadriceps max force |

Gastrocnemius med. max force |

Semitend+Semimembr max force |

Bi-acetabular distance/2 |

| |

2300N |

799N |

8000N |

931N |

2BW |

123.78mm |

Table 2.

Average and SD of measured variables for the athletes. MRI images were used to determine the values for the internal section of the knee.

Table 2.

Average and SD of measured variables for the athletes. MRI images were used to determine the values for the internal section of the knee.

Measured variables

(distances) |

Lateral condyle-ACL (mm) |

Lateral condyle-MCL (mm) |

Lateral condyle-medial condyle (mm) |

Ground-Lateral condyle

(mm) |

Lateral condyle-greater trochanter

(mm) |

| Average |

26,06 |

68,8 |

58,46 |

594,86 |

461,8 |

| SD |

1,7 |

3,27 |

2,82 |

13,89 |

9,33 |