1. Background

Since the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in late 2019, the response involved a remarkable and unprecedented acceleration in developing and distributing vaccines, utilising mRNA and adenoviral vector platforms [

1,

2,

3]. The typical timeline for developing a vaccine is around 10 to 12 years [

4]. The remarkable progress in COVID vaccine development, marked by the rapid growth and deployment of vaccines employing technologies such as messenger RNA (mRNA), harmless S protein subunit vaccines, and viral vector platforms, represents a significant milestone in the history of vaccine development.

In December 2020, the BNT162b2 (Comirnaty™) from Pfizer-BioNTech and the mRNA-1273 from Moderna (encoded antigen: SARS-CoV-2 S protein of the Wuhan-Hu-1 strain) were among the first vaccines to receive emergency use authorisation and were introduced for vaccination [

5,

6,

7]. These vaccines use messenger RNA (mRNA) to instruct cells to make a harmless piece of the spike protein found on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus [

8,

9]. Similarly, vaccines developed by Oxford/AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Sputnik V and Sputnik Light by Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, and Convidecia vaccine by CanSino Biologics were also authorised and rolled out globally in different countries [

10,

11]. These vaccines utilise a modified version of a distinct virus (adenovirus vector-based) to deliver the genetic material necessary to produce the spike protein. Adenovirus vector-based vaccines are divided into two types: non-replicating and replicating viral vector-based vaccines [

10,

11,

12,

13]. These vaccines stimulate the immune system to recognise and combat the SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, each COVID-19 vaccine uses different mechanisms to trigger an immune response.

The mix-and-match (heterologous vaccination) strategy has gained attention for its potential to enhance vaccine effectiveness, accessibility, and flexibility [

14]. Studies have shown that combining viral vector vaccines, such as Oxford/AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 and Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen/Ad26, is effective.COV-2.S, with mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA-1273, generates strong immune responses and may offer broader protection against COVID-19 and its variants [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Homologous vaccination has also demonstrated robust immune responses and a favourable safety profile, with fewer adverse effects than mixed-dose regimens. However, the latter remains safe and effective [

23,

24]. Both strategies play critical roles in addressing vaccine efficacy, accessibility, and supply chain challenges, with the choice often guided by individual health considerations, vaccine availability, and public health policies aimed at optimising immunisation rates.

Studies have shown that COVID vaccines significantly reduce severe symptoms, hospitalisations, and deaths. Fully vaccinated individuals experience lower hospitalisation rates than unvaccinated individuals [

25]. mRNA vaccines are particularly effective in preventing severe outcomes [

26,

27]. Vaccines demonstrate strong efficacy across age groups and demographics, particularly in younger populations, adults, and older people, playing a crucial role in managing the pandemic by reducing hospitalisations and fatalities [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The potential for vaccination to prevent long COVID or other post-viral conditions remains an active area of research, with limited studies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] offering insights into its impact on individuals experiencing long COVID. Moreover, there is a lack of sufficient data on how mix-and-match vaccination approaches, or the timing of vaccine administration, might influence the development of long COVID symptoms. A crucial dimension of long COVID research is the imperative to include diverse populations; however, current studies are still insufficient in addressing this essential facet.

In this study, we utilised propensity score matching to assess the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the likelihood of preventing long COVID symptoms. We evaluated the symptoms of long COVID based on the number of vaccine doses each individual received, compared to those who were unvaccinated. The objective was to clarify whether vaccination offers additional protection against long-term effects following the acute phase of COVID-19 infection. Additionally, we examined the symptomatology of long COVID among individuals who received heterologous (mix-and-match ) vaccine regimens, those who received homologous (same-dose) regimens, and those who remained unvaccinated.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted at a single centre in London, England. We reviewed anonymised electronic patient records (EPR) of 627 individuals diagnosed and treated for COVID-19 between April 2020 and December 2022 who met the study criteria. The study relied exclusively on pre-existing, de-identified data, with no direct interaction or follow-up assessments involving the participants.

The study included adult patients aged 18 years and older who tested positive for COVID-19 and were managed as either outpatients or inpatients within the study centre. Exclusion criteria included paediatric patients, individuals without confirmed COVID-19 test results, and those who succumbed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus during its acute phase. We collected and analysed a range of variables, including patient demographics such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, and social history/lifestyle, smoking status, COVID-19 vaccination history, such as vaccination status, the number of doses administered, the type of vaccines, and whether study participants had a mixed or homologous vaccine approach. In addition, we reviewed the symptoms associated with long COVID among the participants. The data entry and management were conducted using Castor Electronic Data Capture (EDC) software. Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the Health Research Authority (HRA) in England and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW), under REC reference 23/HRA/1637. The findings adhere to the standards detailed in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [

38].

3. Statistic Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.3.3. Participants were categorised into vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, with further stratification based on vaccination approaches: mixed-dose, homologous-dose, and no vaccine groups. We categorised COVID-19 vaccine dosages (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 doses) as a non-binary variable with five levels, based on participant vaccination status. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarise demographic attributes and body mass index distributions. Continuous variables were characterised through central tendency and dispersion measures, while categorical variables were described using frequencies and proportions. Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were utilised to test associations between categorical variables, whereas the Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to evaluate differences in continuous variables. The pattern of missing data was analysed, revealing the absence of any data omissions within the dataset. All individuals lacking a definitive vaccination status were classified as unvaccinated.

Estimating the dose–response relationship between COVID-19 vaccines and the risk of long COVID symptoms

We used a multinomial propensity score framework to analyse how different vaccine doses impact the risk of long COVID. This involved applying inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) based on generalised propensity scores (GPS) to estimate the causal relationship between different levels of vaccine dosages and the occurrence of post-acute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. IPTW is a statistical method used in causal inference to estimate treatment effects from observational data, particularly when there’s a risk of confounding factors [

39,

40]. IPTW generates a pseudo-population with balanced covariates by reweighting patients inversely to their treatment propensity [

41]. IPTW estimates are considered unbiased when a satisfactory balance is achieved between the treatment groups [

42]. However, any residual imbalances that may persist can be effectively addressed through the application of augmented inverse probability of treatment (AIPW) weighting [

42]. IPTW has been proposed in evaluating multiple treatments (or categories of treatment) when several treatments exist for the same indication, or when researchers want to compare the effect of two treatments and their combination [

41]. However, the use of IPTW in this context raises questions about its appropriateness, despite the availability of IPTW estimators for multiple treatment categories [

42].

Step 1: Estimation of generalised propensity scores (GPS)

We fitted a multinomial logistic regression model to estimate the GPS, with vaccine dosage (0 to 4 doses) as the dependent variable. The model included a set of baseline covariates, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, smoking status, and vaccination status, as predictors. The resulting model generated a matrix of predicted probabilities representing each participant’s likelihood of receiving a given dosage level, conditional on their observed covariates.

Step 2: Construction of Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW)

IPTWs were calculated using the GPS corresponding to the observed treatment levels for each participant. To facilitate matrix indexing, vaccine dosage was re-coded numerically starting from 1. Each participant’s weight was determined as the inverse of the estimated probability of receiving their observed treatment dosage. This weighting procedure effectively created a pseudo-population in which treatment allocation was independent of measured confounders, thereby enhancing the robustness of causal inference. We used box plots to assess the variability and distribution of weights in each treatment group.

Step 3: Outcome Analysis

A weighted logistic regression model was then fitted to estimate the association between vaccine dosage and the presence of long COVID symptoms, coded as a binary outcome (1 = Yes, 0 = No). This model utilised IPTW to adjust for confounding, enabling causal inference without relying on direct covariate adjustment. This analytic approach enabled robust estimation of the dose–response relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and the risk of long COVID. By appropriately addressing the multi-level nature of exposure and mitigating confounding bias through reweighting, this method strengthens causal interpretations drawn from observational data [

39,

40,

41,

42].

Estimating the Mixed-Dose Vaccine Approach on Long COVID Symptoms

We also fitted a logistic regression model to estimate propensity scores and assess the impact of different vaccination approaches on the symptoms of long COVID. This model included age, gender, BMI, Smoking status, vaccination status, mixed-dose vaccine, and the vaccination period (vaccination before COVID and after COVID). The model was applied using a binomial family. Then, matching was performed to balance the groups based on their propensity scores. The ‘matchit’ function was used with a logistic distance method and full matching. The matched dataset was extracted using the ‘match.data’ function applied to the match object. This dataset contains individuals from both mixed-dose and the same vaccine regimen groups, who have been matched based on their propensity scores. The outcome analysis was conducted by fitting a logistic regression model to the matched dataset.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

This study involved 627 participants (mean age, 59; SD, 20),

as shown in Table 1. The group consisted of 55% women. The mean BMI was 29 kg/m

2, with a standard deviation of 7. Ethnic representation included 41% White, 23% Black, African, Caribbean, or British, 19% Asian or Asian British, 14% Other, and 3% Mixed race. Sixty-two per cent of participants had never smoked, 8.8% were current smokers, and 13% were former smokers. Sixty-three per cent of participants were vaccinated, while 37% were not. Among the vaccinated participants, 58% received the vaccine after contracting COVID-19, while 42% received it before contracting the disease. Thirty-seven per cent received no vaccine, 2.9% received one dose, 13% received two doses, 29% received three doses, and 18% received four doses. 23% received mixed-dose vaccines, and 39% received the same dose. Only 40% of participants reported long COVID symptoms.

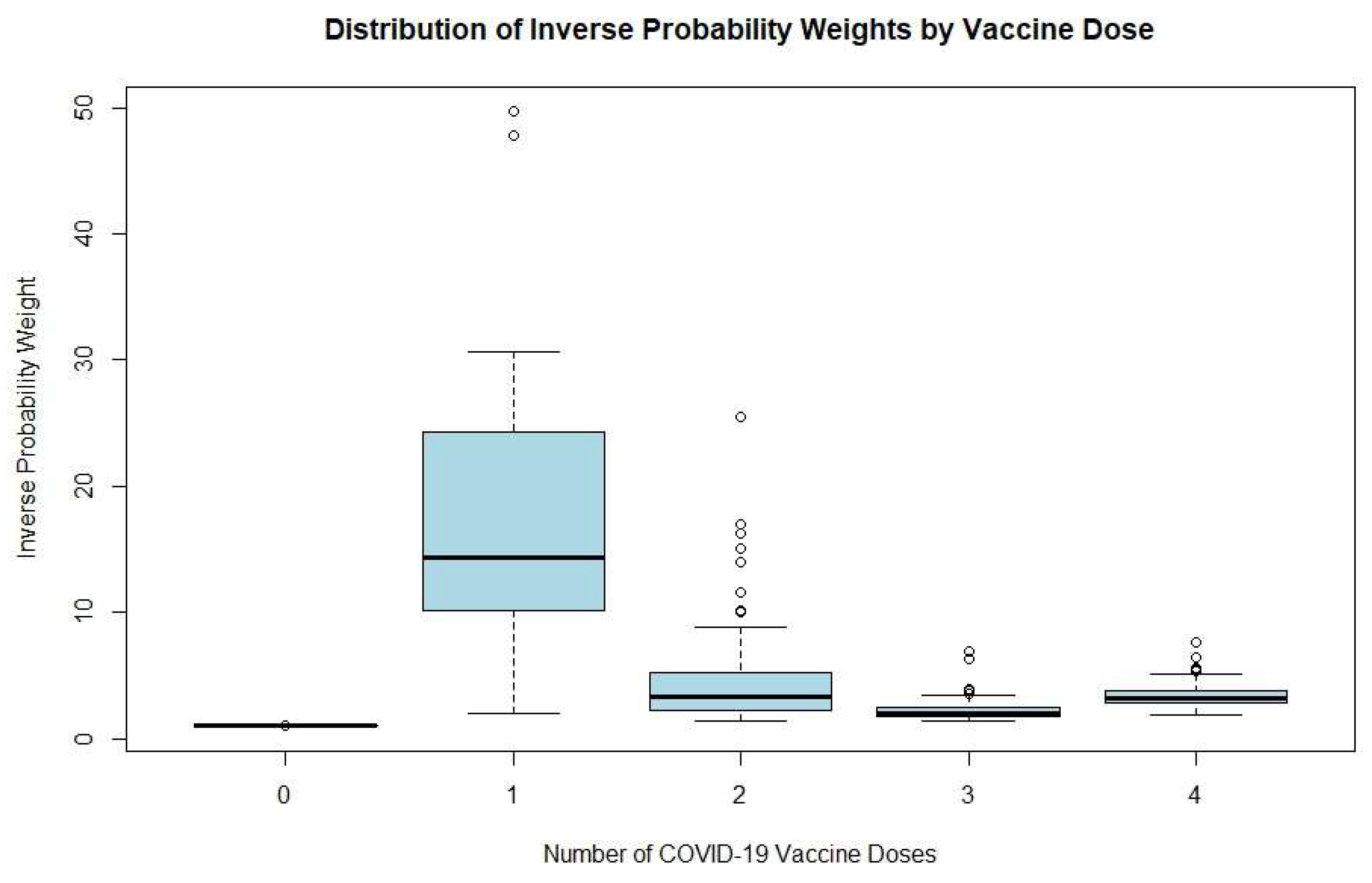

4.2. Distribution of IPTW by Vaccine Dose

Figure 1 displays boxplots of inverse probability weights according to the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received (from zero to four). Participants with no vaccine doses had highly uniform weights, with a mean of approximately 1.0, suggesting minimal variability. The one-dose group showed the greatest spread, with a median weight of nearly 14, a wide interquartile range (10–25), whiskers ranging from approximately 2 to 30, and several extreme outliers approaching 50. This wide dispersion reflects considerable heterogeneity and potentially unreliable effect estimates in this group due to sparse data.

For those with two doses, weights were more moderate and consistent, with a median around 3.5 and a narrower interquartile range (2.5–5), though some outliers still existed. The three-dose group had even more stable weights, with a median of nearly 2.5 and less overall variability. The four-dose group showed a pattern similar to the two-dose group, but with a slightly higher median (about 3.5) and a tight interquartile range (3–4.5), with only a few mild outliers.

4.3. Association Between Vaccine Doses and Long COVID Symptoms

From

Table 2, the intercept had an odds ratio of 0.418, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.316 to 0.554, and a highly significant p-value of 1.13 × 10

9, indicating a low baseline probability of long COVID in the reference group.

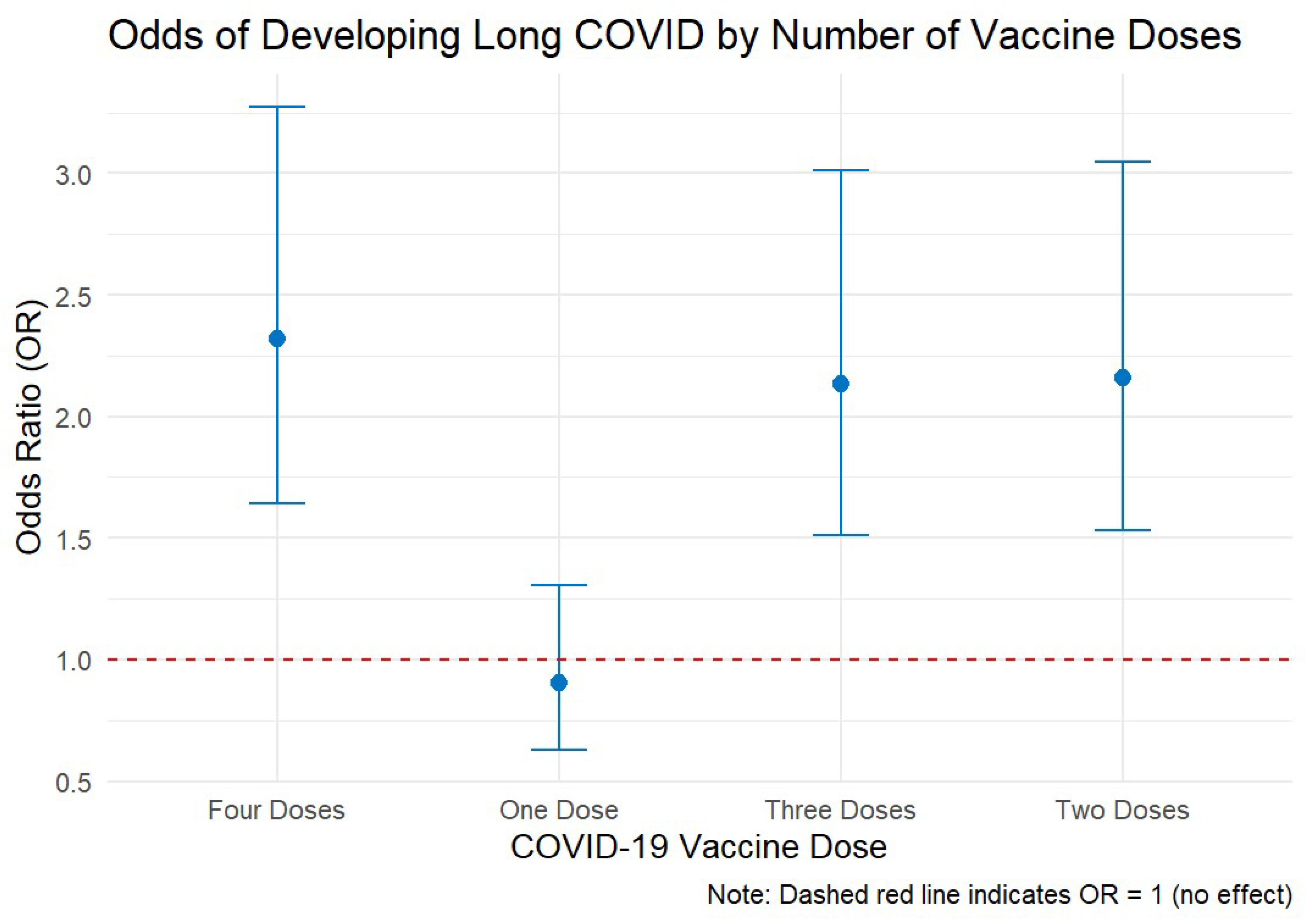

One vaccine dose had an odds ratio of 0.907 (CI: 0.630–1.306, p = 0.600), indicating no significant change in the odds of long COVID. Having two vaccine doses had an odds ratio of 2.160 (CI: 1.531–3.046, p = 0.00), indicating a significant increase in the odds of developing long COVID symptoms. Three doses of the vaccine had an odds ratio of 2.135 (CI: 1.514–3.010, p < 0.001), indicating a strong association with an increased risk of long COVID. Receiving four vaccine doses is associated with an odds ratio of 2.319 (CI: 1.642 - 3.274, p< 0.001), indicating a significant increase in long COVID odds.

In

Figure 2, the dashed red line at OR = 1 serves as a reference point, denoting no effect. All odds ratios beyond one dose lie above this line, visually reinforcing the trend that receiving more doses is associated with a greater likelihood of reporting long COVID.

4.4. Doubly Robust Weighted Model

Based on

Table 3, the intercept was –4.63 (p < 0.001), indicating a very low baseline probability of long COVID in the unadjusted model. For those with one vaccine dose, the coefficient was –0.38 (p = 0.064), indicating a modest, non-significant reduction in the risk of long COVID compared to unvaccinated individuals. Receiving two vaccine doses had a coefficient of +0.69 (p < 0.001), indicating a significant rise in long COVID risk. Similarly, individuals who had received three doses showed an estimated increase of +0.67 (p < 0.001), and those with four doses had an estimated increase of +0.70 (

p < 0.001), both indicating significantly increased risks compared to the unvaccinated group.

Age was strongly correlated with long COVID, with a coefficient of +0.042 (p < 0.001), indicating that the risk increases with age. Gender (male) showed no significant association, with an estimate of 0.024 (p = 0.82). A higher BMI was also significantly associated with a greater risk, with an estimated increase of +0.034 (p < 0.001).

5. Mixed-Dose Vaccine Approach and Long COVID Symptoms.

5.1. Variables Before and After Matching

Figure 3 illustrates the standardised mean differences of various variables both before and after matching. The visual comparison shows how the matching process affects the balance of the variables, intending to reduce the standardised mean differences and achieve better comparability between groups.

5.2. Association Between the Mixed-Dose Vaccine Approach and Long COVID Symptoms

Following the application of logistic regression to the matched dataset, we calculated the adjusted OR to evaluate the association between vaccination approaches and the risk of developing long COVID (

Table 4). Receiving a mixed vaccine regimen was associated with a 41% lower odds of long COVID, although this finding was borderline significant (adjusted OR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.34–1.02; p = 0.070). Receiving the same vaccine regimen was not significantly associated with an increased risk of long COVID (adjusted OR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.45–1.31; p = 0.327). Increasing age was significantly associated with higher odds of long COVID (adjusted OR per year: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.05–1.07; p < 0.001). A higher BMI was marginally associated with an increased risk (adjusted OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 1.00–1.05; p = 0.055). No significant association was observed with gender.

Participants vaccinated after infection had nearly six times higher odds of long COVID than those vaccinated before (adjusted OR: 5.93; 95% CI: 3.63–9.68; p < 0.001). Smoking status showed a trend towards higher odds, particularly for current smokers, but these associations did not reach statistical significance.

6. Discussion

The study evaluated the impact of COVID vaccine doses on the risk of developing long COVID symptoms, employing propensity score matching to control for confounding variables and ensure robust comparisons. The findings revealed that receiving one dose of the vaccine did not significantly affect the likelihood of developing long COVID; however, individuals who received two, three, or four doses had significantly higher odds of experiencing long COVID symptoms. However, when vaccine approach types were considered, a mixed-dose (heterologous) approach was associated with a 41% reduction in the odds of long COVID, though this result was only borderline significant. A same-dose (homologous) approach did not significantly increase the risk of long COVID compared to being unvaccinated. Importantly, those vaccinated after infection had nearly six times the odds of developing long COVID compared to those vaccinated before infection.

Similarly, a study found that fully vaccinated patients were more likely to report long COVID symptoms four weeks post-diagnosis [

43]. The relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and the incidence of long COVID symptoms has been a topic of debate. Studies have reported that vaccinated individuals could still experience long COVID symptoms, albeit potentially at a lower rate than their unvaccinated counterparts. While vaccination reduced the prevalence of long COVID symptoms, a significant proportion of vaccinated individuals still reported persistent symptoms [

44]. Another study indicated that people who had been fully vaccinated were less likely to experience long-term symptoms, although the risk was not completely eliminated [

45]. This suggests that while vaccination is beneficial, it does not completely preclude the possibility of long COVID. Several hypotheses can be proposed to explain why COVID-19 vaccination may increase the likelihood of experiencing long COVID symptoms. Firstly, the immune system modulation (ISM) hypothesis suggests that vaccines are formulated to activate the immune system. In some individuals, this heightened immune response might exacerbate lingering symptoms from a previous COVID-19 infection, potentially leading to an increased reporting of long COVID symptoms [

46]. Another hypothesis is viral persistence. Studies suggest that remnants of the virus might persist in the body even after recovery from the acute phase of COVID-19. The vaccine could stimulate the immune system to attack these viral remnants, causing inflammation and symptoms associated with long COVID [

47].

Additionally, there is a pre-existing conditions hypothesis, which posits that individuals who have had COVID-19 and then receive the vaccine may already have underlying conditions or a predisposition to long COVID. The vaccine could act as a catalyst, bringing these symptoms to the forefront [

48]. The autoimmune reactions hypothesis believes that there is a possibility that the vaccine could trigger autoimmune reactions in some individuals, particularly those who have had COVID-19. This could lead to symptoms that overlap with those of long COVID [

49]. The proposition that “SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein persists at much higher inferred concentrations among the vaccinated compared to infection alone” has biological plausibility, and emerging evidence lends it partial support, though many questions remain about causality and interpretation. Several laboratory and case-series studies have detected persistent Spike protein in blood or tissues long after mRNA vaccination and in some cases, for longer than in natural infection. One study reported Spike S1 subunit fragments persisting in CD16

+ monocytes up to 245 days post–infection in post–acute sequelae of COVID (PASC) patients, hinting at long-term antigen retention, though it did not directly compare vaccinated vs infected-only levels [

50]. Another investigation detected Spike protein in circulation 105 days after vaccination in individuals with post-vaccine syndrome (PVS), and in some cases, even past 700 days, suggesting prolonged Spike presence even without documented infection [

51]. On the tissue level, Spike has been found in brain meninges and skull bone marrow up to four years post-infection; vaccination was shown to reduce tissue Spike burden by ~50%, but did not fully eliminate it [

52]. One autopsy-based study even detected Spike in cerebral arterial tissues up to 17 months post-vaccination [

53]. Thus, biologically, vaccinated individuals, particularly those who later get infected, may accumulate Spike from both vaccine-encoded and infection-derived sources, leading to potentially higher overall exposure. Finally, the psychological factors hypothesis postulates that the stress and anxiety associated with having had COVID-19 and then receiving the vaccine might contribute to the perception and reporting of long COVID symptoms. Psychological factors can significantly influence how symptoms are experienced and reported [

54].

However, our findings stand in contrast to much of the emerging evidence that COVID-19 vaccination reduces the risk of post–COVID-19 condition. Most prior observational analyses have reported lower long-COVID incidence among vaccinated individuals. For example, a large Swedish registry study found a long-COVID incidence of 0.4% in unvaccinated adults compared to 0.1% after three doses (adjusted risk ratios of ~0.42 for two doses and 0.37 for three doses) [

55]. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis of 25 studies reported that receiving two doses of vaccine before infection was associated with a 24% reduction in the odds of long COVID (summary OR ~0.76, 95% CI 0.65–0.89) [

56]. A systematic review also noted that most studies of two or more doses (administered pre-infection) found significant reductions in long-COVID, whereas one dose showed a less clear effect [

47]. These and other reports suggest that vaccines, by preventing infection or reducing disease severity, tend to lower long-COVID risk [

47,

57]. In line with this, an ECDC evidence review found fully vaccinated adults had about 27% lower risk of long COVID compared to unvaccinated adults [

57].

Regarding the effect of booster strategy, our observation of a borderline reduction (41% lower odds) in long COVID risk with heterologous (mixed) vs. homologous boosting is intriguing but should be interpreted cautiously. Heterologous booster regimens have been shown to induce stronger or broader immune responses in some studies, and meta-analyses of COVID-19 boosters suggest heterologous boosters may confer equal or slightly better protection against symptomatic infection than same-brand boosters [

58]. If true, this could plausibly translate into a modestly lower risk of persistent symptoms, although we are unaware of other studies directly comparing mix-and-match boosting on long COVID outcomes. Our result was only marginally significant and may arise by chance or residual confounding (for example, individuals choosing mixed boosters could differ in health status or exposure). By contrast, homologous boosting (same vaccine for all doses) in our data showed no significant difference from no vaccination, again against the broader trend of evidence favouring higher-dose protection [

55,

56].

This study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. First, the retrospective observational design is inherently subject to residual confounding, even after applying propensity score matching. Important unmeasured variables, such as pre-existing autoimmune conditions, undiagnosed reinfections, or specific timing between vaccine doses and SARS-CoV-2 infection, could have influenced the results. Second, the assessment of long COVID was based on healthcare records, which may introduce misclassification bias due to variability in diagnostic criteria or incomplete symptom documentation. Furthermore, we did not have access to biological data such as antibody titers, markers of inflammation, or direct measurements of circulating or tissue-resident SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein. As such, we were unable to evaluate mechanistic pathways potentially linking vaccine exposure, antigen persistence, and long COVID outcomes. Third, while our analysis explored different vaccination regimens, it did not account for the type of vaccine platform (e.g., mRNA vs. viral vector), lot variability, or potential waning of vaccine-induced immunity. Similarly, we could not distinguish between individuals who received boosters due to high-risk status versus those who received them as part of standard public health recommendations, introducing potential indication bias. Causality cannot be established due to the observational nature of the study. The increased odds of long COVID with higher vaccine doses may reflect underlying susceptibility, reverse causation (e.g., sicker individuals receiving more doses), or complex interactions between vaccine timing and infection. Longitudinal, prospective studies incorporating immunological profiling, viral kinetics, and vaccine–infection sequencing are necessary to confirm these associations and elucidate the underlying biological mechanisms.

This study highlights the urgent need for mechanistic research into the complex relationship between COVID-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and long COVID. The observed association between higher vaccine doses and increased odds of long COVID, as well as the protective trend seen with mixed vaccine regimens, underscores the importance of investigating immunological pathways such as Spike protein persistence, immune imprinting, and vaccine-induced tolerance. Future studies should incorporate biomarker data, including anti-Spike antibody profiles, inflammatory cytokines, and direct measurements of Spike protein in blood or tissues. Longitudinal, prospective cohort designs with precise vaccine–infection temporal sequencing will be essential to disentangle causality and understand the biological underpinnings of long COVID risk.

7. Conclusion

This study provides important insights into the association between COVID-19 vaccination and the risk of developing long COVID. While a single vaccine dose did not significantly influence long COVID odds, receiving two or more doses was associated with a markedly increased likelihood of persistent symptoms, particularly among individuals vaccinated after infection. Conversely, a mixed (heterologous) vaccine approach showed a potential protective effect, though this finding approached but did not reach statistical significance. These findings underscore the complexity of the interplay between vaccination, infection timing, and long-term health outcomes. They highlight the need for further research into the immunological mechanisms underpinning long COVID and call for more nuanced vaccination policies that balance short-term protection with long-term risk. As the global focus shifts toward long-term COVID-19 management, understanding these dynamics is essential for guiding future vaccine deployment strategies, clinical monitoring, and public health planning.

Author Contributions

LPD was responsible for developing the study protocol, conducting the research, analysing the data, and drafting the manuscript. YR identified the study participants, reviewed the protocol, and supervised data collection. FIFA and JEA provided oversight, and reviewed both the study protocol and the manuscript. RK had overall responsibility for the study, reviewed the protocol and manuscript, and provided comprehensive supervision throughout.

Funding

This research was funded by Croydon Health Services NHS Trust. Kingston University London funded the APC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Health Research Authority (HRA), England, and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) approved the study with REC reference 23/HRA/1637.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. In its approach, the study was designed to be retrospective.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledged the Croydon Health Services NHS Trust, London, and the Research Office Team at the Croydon University Hospital, London.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| AIPW |

Augmented Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| COV-2.S |

COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) |

| EDC |

Electronic Data Capture |

| EPR |

Electronic Patient Records |

| GPS |

Generalised Propensity Score |

| HCRW |

Health and Care Research Wales |

| HRA |

Health Research Authority |

| IPTW |

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting |

| ISM |

Immune System Modulation |

| mRNA |

Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| NHS |

National Health Service |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PASC |

Post–Acute Sequelae of COVID |

| PVS |

Post–Vaccine Syndrome |

| REC |

Research Ethics Committee |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

References

- Hossaini Alhashemi, S.; Ahmadi, F.; Dehshahri, A. Lessons learned from COVID-19 pandemic: Vaccine platform is a key player. Process Biochem. 2023, 124, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, R. mRNA and adenoviral vector vaccine platforms utilised in COVID-19 vaccines: Technologies, ecosystem, and future directions. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, S.A.; Lorincz, R.; Boucher, P.; et al. Adenoviral vector vaccine platforms in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. npj Vaccines 2021, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What History Tells Us About Vaccine Timetables. CRiver. Available online: https://www.criver.com/eureka/what-history-tells-us-about-vaccine-timetables (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Pfizer and BioNTech achieve first authorization in the world for a vaccine to combat COVID-19. Pfizer News. Available online: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-achieve-first-authorization-world (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- U. S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. FDA News Release. 23 August 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Heinz, F.X.; Stiasny, K. Distinguishing features of current COVID-19 vaccines: Knowns and unknowns of antigen presentation and modes of action. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Venkataraman, A.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A. Messenger RNA-based vaccines: Past, present, and future directions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 179, 114000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Verbeke, R.; Lentacker, I.; De Smedt, S.C.; Dewitte, H. The dawn of mRNA vaccines: The COVID-19 case. J. Control Release 2021, 333, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vanaparthy, R.; Mohan, G.; Vasireddy, D.; Atluri, P. Review of COVID-19 viral vector-based vaccines and COVID-19 variants. Infez. Med. 2021, 29, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weber, R.; Explaining Johnson; Johnson’s, AstraZeneca’s new COVID-19 vaccines. Wexner Medical Center blog, 2 March 2021. Available online: https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/blog/explaining-johnson-johnson-astrazeneca-vaccines (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Sakurai, F.; Tachibana, M.; Mizuguchi, H. Adenovirus vector-based vaccine for infectious diseases. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 42, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gavi. What are viral vector-based vaccines and how could they be used against COVID-19? Gavi Vaccineswork. 29 December 2020. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/what-are-viral-vector-based-vaccines-and-how-could-they-be-used-against-covid-19 (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Jahed, A.; Molana, S.M.H.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; et al. Designing an integrated sustainable-resilient mix-and-match vaccine supply chain network. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, R.; Samieefar, N.; Masoumi, N.; Mohseni, S.; Rezaei, N. COVID-19 vaccines mix-and-match: The concept, the efficacy and the doubts. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA and ECDC recommendations on heterologous vaccination courses against COVID-19: ‘mix-and-match’ approach can be used for both initial courses and boosters. 2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-and-ecdc-recommendations-heterologous-vaccination-courses-against-covid-19-mix-and-match-approach-can-be-used-both-initial-courses-and-boosters (accessed on 2021).

- Shekhar, K.; Sakthivel, P.; Gupta, N.; Ish, P. Mix and match COVID-19 vaccines: Potential benefit and perspective from India. Postgrad. Med. J. 2022, 98, e99–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Nittayasoot, N.; Jiraphongsa, C.; et al. Real-world effectiveness of mix-and-match vaccine regimens against SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in Thailand: A nationwide test-negative matched case-control study. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westrop, S.J.; Whitaker, H.J.; Powell, A.A.; Power, L.; Whillock, C.; Campbell, H.; et al. Real-world data on immune responses following heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccination schedule with Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines in England. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Wu, Q.; Pan, H.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a third dose of CoronaVac, and immune persistence of a two-dose schedule, in healthy adults: Interim results from two single-centre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, N.C.; Chi, H.; Tu, Y.K.; et al. To mix or not to mix? A rapid systematic review of heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccination. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, I.; Sheikh, A.B.; Pal, S.; Shekhar, R. Mix-and-match COVID-19 vaccinations (heterologous boost): A review. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 14, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hưng, P.; Nguyen, D.; Ha, L.; Lam, T.; Tram, T. Common adverse events from mixing COVID-19 vaccine booster in Hanoi, Vietnam. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazbik, R.; Baajajah, L.; Alharthy, S.; Alsalahi, H.; Mahjaa, M.; Barakat, M.; et al. Side effects associated with homologous and heterologous COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Comparison of the clinical profile and outcomes of COVID-19 infection in vaccinated and unvaccinated people. Heart Vessels Transplant. 2024; Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajema, K.; Dahl, R.; Prill, M.; Meites, E.; Rodriguez-Barradas, M.; Marconi, V.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines against COVID-19-associated hospitalization — five Veterans Affairs medical centers, United States, February 1–August 6, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahidy, F.; Pischel, L.; Tano, M.; Pan, A.; Boom, M.; Sostman, H.; et al. Real world effectiveness of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines against hospitalisations and deaths in the United States. Preprint. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulah, D.; Mirza, A. Receiving COVID-19 vaccine, hospitalisation, and outcomes of patients with COVID-19: A prospective study. Monaldi Arch. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.; Newhams, M.; Halasa, N.; Price, A.; Boom, J.; Sahni, L.; et al. Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccination against COVID-19 hospitalization among persons aged 12–18 years — United States, June–September 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poukka, E.; Goebeler, S.; Nohynek, H.; Leino, T.; Baum, U. Bivalent booster effectiveness against severe COVID-19 outcomes in Finland, 22–March 2023. 2023. Preprint. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Bixby, L. The effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines to prevent severe COVID-19 in Costa Rica: Nationwide, ecological study of hospitalization prevalence. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e35054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Nemati, M.; Shahisavandi, M.; et al. How does COVID-19 vaccination affect long-COVID symptoms? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Bosworth, M.; King, S.; Pouwels, K.; Glickman, M.; Nafilyan, V.; et al. Risk of long COVID in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 after two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine: Community-based, matched cohort study. 2022. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Brannock, M.D.; Chew, R.F.; Preiss, A.J.; et al. Long COVID risk and pre-COVID vaccination: An EHR-based cohort study from the RECOVER Program. Preprint. medRxiv, 2022; 2022.10.06.22280795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Montoliu, S. Long COVID prevalence and the impact of the third SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose: A cross-sectional analysis from the third follow-up of the Borriana cohort, Valencia, Spain (2020–2022). Vaccines 2023, 11, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Liu, J.; M, L. Effect of COVID-19 vaccines on reducing the risk of long COVID in the real world: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Luginbuhl, R.; Parker, R. Reduced incidence of long-COVID symptoms related to administration of COVID-19 vaccines both before COVID-19 diagnosis and up to 12 weeks after. 2021. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org (accessed on 2024).

- Chesnaye, N.C.; et al. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 15, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C.; Stuart, E.A. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat. Med. 2015, 34, 3661–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettega, F.; Mendelson, M.; Leyrat, C.; Bailly, S. Use and reporting of inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting for multicategory treatments in medical research: A systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2024, 170, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Causal Inference: What If; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Budhiraja, S.; Indrayan, A.; Mahajan, M. Effect of COVID-19 vaccine on long-COVID: A 2-year follow-up observational study from hospitals in North India. 2022. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Adly, H. Post COVID-19 symptoms among infected vaccinated individuals: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannous, J.; Pan, A.; Potter, T.; Bako, A.; Dlouhy, K.; Drews, A.; et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies against postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2: Analysis of a COVID-19 observational registry for a diverse US metropolitan population. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BMJ. Covid-19: Vaccination reduces severity and duration of long COVID. BMJ 2023, 380, p491. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/380/bmj.p491 (accessed on 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byambasuren, O.; Stehlik, P.; Clark, J.; Alcorn, K.; Glasziou, P. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on long COVID: Systematic review. BMJ Med. 2023, 2, e000385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. Coronavirus vaccines cut risk of long COVID, study finds. BBC News 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-58410354 (accessed on 2021).

- Yale Medicine. COVID vaccines reduce long COVID risk, new study shows. Yale Medicine 2023. Available online: https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-vaccines-reduce-long-covid-risk-new-study-shows (accessed on 2023).

- Patterson, B.K.; Yogendra, R.; Francisco, E.B.; Guevara-Coto, J.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; … Mora, R. Detection of S1 spike protein in CD16+ monocytes up to 245 days in SARS-CoV-2-negative post-COVID-19 vaccine syndrome (PCVS) individuals. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locklear, M.; Immune markers of post-vaccination syndrome indicate future research directions: A small number of people report chronic symptoms after receiving COVID-19 shots. News Yale. 19 February 2025. Available online: https://news.yale.edu/2025/02/19/immune-markers-post-vaccination-syndrome-indicate-future-research-directions (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Helmholtz Zentrum München. Spike protein persistence in brain/meninges up to 4 years; vaccination halves but doesn’t eliminate burden. SciTechDaily 2025. Available online: https://scitechdaily.com/long-covid-breakthrough-spike-proteins-persist-in-brain-for-years (accessed on 2025).

- Ota, N.; Itani, M.; Aoki, T.; Sakurai, A.; Fujisawa, T.X.; Okada, Y.; … Tanikawa, R. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in cerebral arteries: Implications for hemorrhagic stroke post-mRNA vaccination. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2025, 136, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. Covid-19: Vaccination reduces severity and duration of long COVID, study finds. BMJ 2023, 380, p491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beusekom, M.; 3 vaccine doses cut long-COVID risk by over 60%, analysis suggests. CIDRAP News 2025. Available online: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/covid-19/3-vaccine-doses-cut-long-covid-risk-over-60-analysis-suggests (accessed on 2025).

- Chow, N.K.N.; Tsang, C.Y.W.; Chan, Y.H.; et al. The effect of pre-COVID and post-COVID vaccination on long COVID: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). COVID-19 vaccination reduces risk of ‘long COVID’ in adults. ECDC News 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/covid-19-vaccination-reduces-risk-long-covid-adults (accessed on 2025).

- Asante, M.; Michelsen, M.E.; Balakumar, M.M.; Kumburegama, B.W.; Sharifan, A.; Thomsen, A.R.; … Menon, S. Heterologous versus homologous COVID-19 booster vaccinations for adults: Systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).