Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Risk Factors for Prescribing Cascades

3. Examples of Prescribing Cascades and Their Clinical Significance

4. Consequences of Prescribing Cascades

5. Identification and Prevention of Prescribing Cascades

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| ACEI | Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors |

| OTC | Over The Counter |

| EBM | Evidence Based Medicine |

| PIPC | Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing Cascades |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| DDP-4 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 |

| SGLT-2 | Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drug |

| ADR | Adverse Drug Reaction |

References

- Adrien, O.; Mohammad, A.K.; Hugtenburg, J.G.; et al. Prescribing Cascades with recommendations to Prevent or Reverse Them: A Systematic Review. Drugs and Anging. 2023, 40, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, F.; Moriarty, F.; Boland, F.; et al. Prescribing cascades in ambulatory care: A structured synthesis of evidence. Pharmacotherapy, 2024, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woroń, J.; Tymiński, R.; Drygalski, T.; et al. Farmakoterapia nieprawidłowo dobrana, co to znaczy w praktyce, a także w Oddziale Intensywnej Terapii. Anestezjologia i Ratownictwo 2023, 17, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rochon, P.A.; Gurwitz, J.H. The prescribing cascade revisited. Lancet 2017, 6, 1778–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, A.S.; Shahid, F.; Moriarty, F.; et al. Prescribing cascades in community-dwelling adults: A systematic review. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2022, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreischulte, T.; Shahid, F.; Muth, C.; et al. Prescribing Cascades: How to Detect Them, Prevent Them, and Use Them Appropriately. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2022, 119, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, L.M.; Savage, R.; Dalton, K.; et al. A Tool for Identifying Clinically Important Prescribing Cascades Affecting Older People. Drugs Aging. 2022, 39, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, F.; Doherty, A.; Wallace, E.; et al. Prescribing cascades in ambulatory care: A structured synthesis of evidence. Pharmacotherapy. 2024, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, L.; et al. Research on prescribing cascades: A scoping review. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, A.A.; Doherty, A.S.; Clyne, B.; et al. Stakeholder perceptions of and attitudes towards problematic polypharmacy and prescribing cascades: A qualitative study. Age Ageing. 2024, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Mahony, D.; Rochon, P.A. Prescribing cascades: We see only what we look for, we look for only what we know. Age Ageing. 2022, 51, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochon, P.A.; O'Mahony, D.; Cherubini, A.; et al. International expert panel's potentially inappropriate prescribing cascades (PIPC) list. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria. Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023. Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 923–947. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, B.; Tsang, C.; Raman-Wilms, L.; et al. What are priorities for deprescribing for elderly patients? Capturing the voice of practitioners: A modified Delphi process. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponte, M.L.; Wachs, L.; Wachs, A.; Serra, H.A. Prescribing cascade. A proposed new way to evaluate it. Medicina (B Aires). 2017, 77, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, L.M.; Visentin, J.D.; Rochon, P.A. Assessing the Scope and Appropriateness of Prescribing Cascades. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk factor | A mechanism promoting the prescribing cascade |

| Patient age | Age-related changes in drug metabolism and excretion (pharmacokinetics) as well as tissue responsiveness to drugs (pharmacodynamics) increase susceptibility to adverse drug reactions. Use of high-risk medications in geriatric populations. |

| Sex | In certain therapies, women have a higher likelihood of developing prescribing cascades, due to differences in drug absorption rates, hormonal regulation, and metabolic pathways. |

| Polypharmacy | A large number of concurrently used drugs increases the probability of drug–drug interactions and adverse events, which may be mistakenly interpreted as new diseases. |

| Multimorbidity | The coexistence of multiple comorbidities predisposes to multi-organ dysfunction of varying severity, which affects drug metabolism and elimination. Multiple diseases often require multiple medications. |

| Chronic use of multiple medications |

Long-term therapies promote the accumulation (“overlapping”) of adverse effects and increase the risk of their misinterpretation. |

| Lack of comprehensive medication review |

Lack of regular assessment of the appropriateness of a given therapy (the entire treatment regimen) perpetuates the use of unnecessary medications and fosters the development of prescribing cascades. Additionally, the absence of dose reassessment maintains adverse drug effects. Prescribing more drugs instead of minimizing doses, and the failure to consider non-pharmacological alternatives before initiating drug therapy, further contribute to the problem. |

| Overprescribing | Insufficient communication about pharmacological interventions implemented by various specialists involved in patient care, including primary care physicians. |

| Misinterpretation of symptoms | Adverse drug reactions are misinterpreted as new disease entities, and the patient receives additional medications instead of therapeutic modification. |

| Insufficient knowledge of prescribing cascades among healthcare professionals |

Insufficient knowledge of the relationship between drugs and symptoms results in a failure to recognize that a new symptom is an adverse effect of a medication rather than a new disease. |

| Self-medication | The trend toward a “healthy lifestyle,” widespread availability of OTC drugs, and self-directed treatment, often reinforced by lack of trust in physicians and insufficient pharmacological knowledge. |

| Pathosupplementation (unnecessary supplementation without clinical indication) |

Dietary supplements as part of alternative treatment approaches. Easy access to various supplements, combined with aggressive marketing, promotes their use. Supplements are often perceived as an element of a “healthy lifestyle” and part of pro-health trends. |

| Treating the disease rather than the patient with the disease | In the context of appropriately tailored pharmacotherapy, patient characteristics play a crucial role and may constitute significant risk factors for the occurrence of adverse drug reactions, including complex, multifactorial complications arising from the specific nature of the pharmacotherapy employed |

| Uncritical and context-free application of therapeutic guidelines | A therapeutic guideline must address not only individual diseases, but its appropriate application in a given patient should always be considered within the full spectrum of multimorbidity |

| Assumption of a class effect within specific drug groups used in the patient | Within specific drug classes, a uniform class effect does not exist, which results from differences in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) parameters, as well as variability in adverse effect profiles and the associated risk factors for their occurrence. |

| Fragmentation of multimorbidity in pharmacological decision-making | Decisions regarding the initiation of pharmacotherapy for individual disease entities should always be guided by consideration of the overall spectrum of multimorbidity in the patient |

| Lack of benefit–risk assessment prior to initiation of pharmacotherapy | Before initiating any medication, the benefit–risk balance must be assessed, as it is influenced by patient-specific characteristics, coexisting risk factors for adverse events, concomitant pharmacotherapy, the use of complementary or alternative medicines, and dietary supplements. Equally relevant is the consumption of broadly defined recreational substances, as well as a history of prior drug-induced adverse reactions |

| Self-medication and supplementation | They may trigger drug interactions and complications, ultimately modifying the benefit–risk balance of the ongoing pharmacotherapy |

| Lack of awareness of the adverse effect profiles of prescribed drugs | In the context of polypharmacotherapy, clinicians must have a thorough understanding of the adverse effect profiles of prescribed agents and the risk factors predisposing to their development |

| Misinterpretation of drug-induced adverse effects as disease symptoms without consideration of ongoing pharmacotherapy | When new symptoms occur in a patient receiving pharmacotherapy, the primary consideration should be whether they are attributable to the treatment itself. If confirmed, appropriate modifications of the pharmacotherapy are required |

| Uncritical use of electronic tools for assessing the risk of drug–drug interactions in polypharmacotherapy | Most drug–interaction prediction tools fail to indicate the dosage thresholds at which interactions become clinically relevant, and only a limited number report interactions arising from the additive adverse effects of concomitantly used medications |

| Cumulative adverse effects of drugs in polypharmacotherapy as a source of complications in patients with multimorbidity | The additive effects of adverse reactions represent one of the most frequent forms of drug interactions in clinical practice. The symptoms that emerge through this mechanism frequently initiate a prescribing cascade. |

| Drug A | Adverse effect | Drug B |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | Peripheral edema | Diuretic |

| Diuretic | Urinary incontinence | Overactive bladder medication |

| Antipsychotic | Extrapyramidal symptoms | Antiparkinsonian agent |

| Benzodiazepine | Cognitive impairment | Cholinesterase Inhibitor or memantine |

| Benzodiazepine | Paradoxical agitation or agitation secondary to withdrawal | Antipsychotic |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) / Serotonin-norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI) | Insomnia | Sleep agent (e.g., Benzodiazepines, Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists, Sedating antidepressant, Melatonin) |

| NSAID | Hypertension | Antihypertensive |

| Urinary Anticholinergics | Cognitive impairment | Cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine |

| Alpha-1 Receptor Blocker | Orthostatic hypotension, dizzines | Vestibular sedative (e.g., betahistine, Antihistamines, Benzodiazepines) |

| Drug A | Adverse effect | Drug B |

| Cardiovascular system | ||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | Cough | Cough remedy |

| Antihypertensive | Orthostatic hypotension/dizziness | Antiemetic |

| Drug-induced hypertension | Hypertension | Antihypertensive drugs |

| Beta-blocker (particularly lipophilic e.g., propranolol) | Depression | Antidepressant |

| Beta-blocker (particularly lipophilic e.g., propranolol) | Erectile dysfunction | Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, alprostadil |

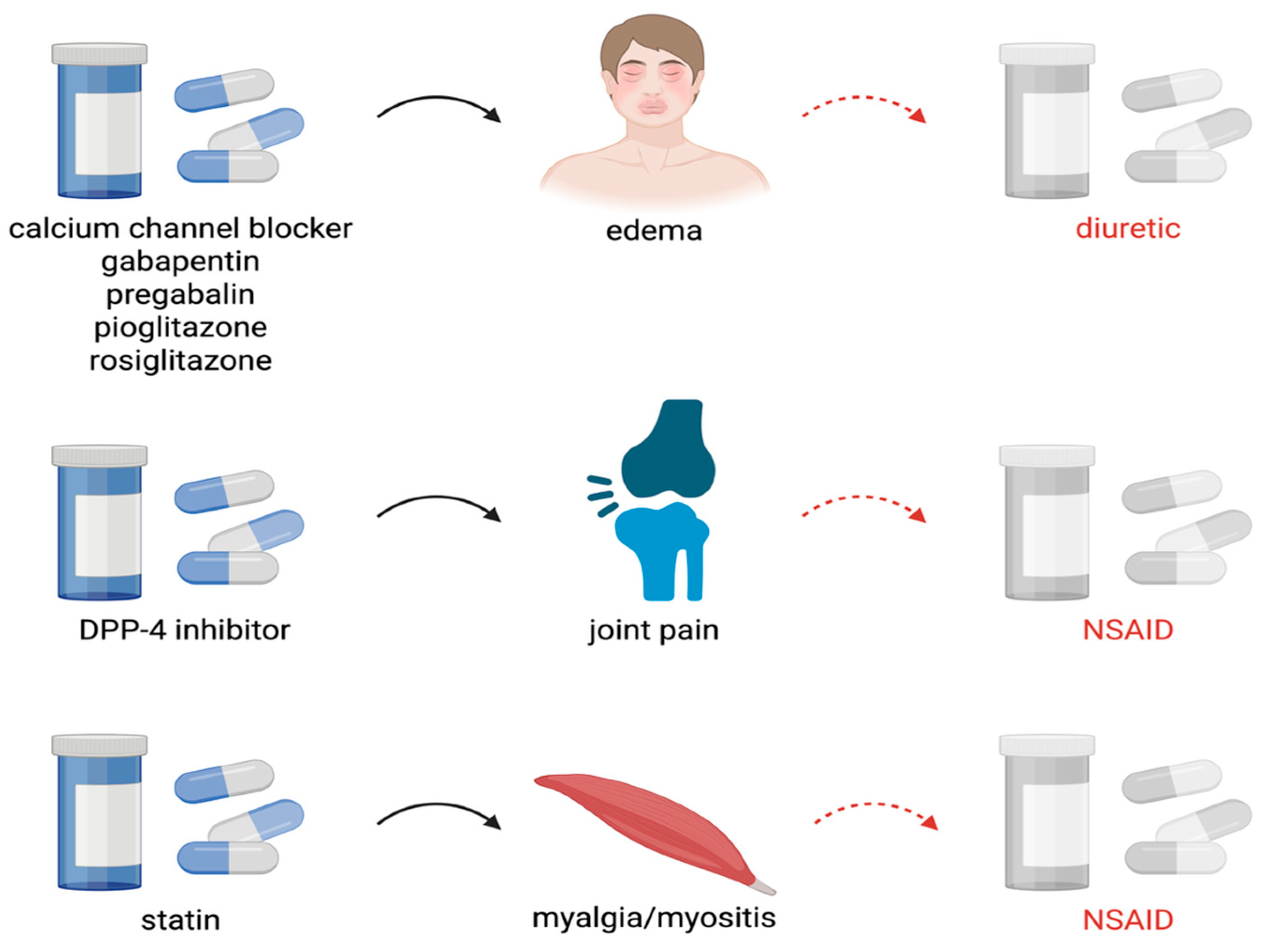

| Calcium channel blocker, Gabapentin, Pregabalin | Peripheral edema | Diuretic |

| Calcium channel blocker | Constipation | Laxative |

| Diuretic | Gout or Hyperuricemia | Anti-gout agent |

| Diuretic | Urinary incontinence | Overactive bladder medication |

| Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG Co-A) reductase inhibitor (statin) | Myalgia/myositis | Pain reliever |

| HMG Co-A reductase inhibitor | Myalgia/myositis | Mineral suplement, Quinine sulfate |

| HMG Co-A reductase inhibitor | Insomnia | Sleep agent |

| Digoxin | Nausea | Antiemetic |

| Midodrine | Hypertension | Antihypertensive |

| Central nervous system | ||

| Anticonvulsant | Rash | Topical corticosteroid |

| Anticonvulsant | Nausea | Antiemetic |

| Antipsychotic | Extrapyramidal symptoms | Beta-blocker, Antiparkinsonian agent, Anti-tremor antimuscarinic |

| Antipsychotic | Akathisia or tardive movements | Sedative |

| Antipsychotic | Arrhythmia | Antiarrhythmic |

| Antipsychotic | Hyperglycemia | Antihyperglycemic |

| Benzodiazepine | Cognitive impairment | Cholinesterase Inhibitor |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | Urinary incontinence | Overactive bladder medication |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | Insomnia | Sleep agent |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | Gastrointestinal upset | Antiemetic, Bismuth subsalicylate |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | Diarrhea | Antidiarrheal |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | Rhinorrhea | Antihistamine |

| Dopaminergic Antiparkinsonian agent | Psychotic symptoms, hallucinations | Antipsychotic |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor/Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSRI/SNRI) | Urinary Incontinence | Overactive bladder medication |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | Cognitive Impairment | Cholinesterase Inhibitor |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | Constipation | Laxative |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | Urinary incontinence | Overactive bladder medication |

| Flunarizine | Depression | Antidepressant |

| Lithium | Extrapyramidal symptoms | Antiparkinsonian agent |

| Venlafaxine | Hypertension (dose-related) | Antihypertensive |

| Venlafaxine | Tremor | Benzodiazepine |

| Anticholinergics | Dyspepsia/reflux (gastroesophageal reflux disease — ‘GERD’) | Proton pump inhibitor |

| Drug-induced movement disorders | Movement disorders | Antiparkinsonian drugs |

| Endocrine system | ||

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor (e.g., sitag- liptin, saxagliptin) | Joint pain | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor | Mycotic genital infections | Antifungal |

| Metformin | Diarrhea | Antidiarrheal |

| Pioglitazone or Rosiglitazone | Edema | Diuretic |

| Rosiglitazone | Heart failure | Diuretic |

| Gastrointestinal system | ||

| Anticholinergic antiemetic | Urinary retention | Alpha-1 receptor blocker |

| Antidopaminergic antiemetic | Extrapyramidal symptoms | Antiparkinsonian agent |

| Laxative | Diarrhea | Antidiarrheal agent |

| Proton pump inhibitor | Osteoporosis, fractures | Vitamin supplement |

| Proton pump inhibitor | Vitamin or Mineral Deficiency | Vitamin supplement |

| Musculoskeletal system | ||

| Bisphosphonate | Gastritis | Gastroprotective agent |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) | Gastritis/gastric ulcer/gastrointestinal bleed | Gastroprotective agent |

| NSAID | Nausea | Antiemetic |

| NSAID | Hypertension | Antihypertensive |

| NSAID | Worsening of heart failure | Heart failure agent |

| Opioid | Depression | Antidepressant |

| Urogenital system | ||

| Alpha-1 receptor blocker | Orthostatic hypotension, dizziness | Vestibular suppressant |

| Urinary anticholinergic | Dry mouth | Saliva substitute |

| Miscellaneous system | ||

| Carbapenem (e.g., imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem) | Seizures | Anticonvulsant |

| Corticosteroid | Insomnia | Sleep agent |

| Corticosteroid | Psychosis | Antipsychotic |

| Corticosteroid | Hypertension | Antihypertensive |

| Acitretin | Vulvo-vaginal candidiasis | Antifungal |

| Erythromycin | Arrhythmia | Antiarrhythmic |

| Fludrocortisone | Hypertension | Antihypertensive |

| Iron supplement | Constipation | Laxative |

|

Existence of ADR, either expected or unknown: Doubtful 0 Yes 1 Yes, but misunderstood 2 |

|

Action followed against the ADR: Treatment discontinuation 0 Continued with dose reduction 1 Continued unchanged or with another drug of the same group 2 |

|

Existence of a second drug treatment for the ADR: No 0 Yes 1 |

|

Overall result of this new treatment: Patient improves 0 Patient worsens or remains unchanged 1 A new ADR appears 2 The new ADR requires a third drug treatment 3 |

| Does/did the precipitating drug cause or pose a risk for a clinically relevant adverse drug reaction? |

| Is the precipitating drug still indicated? |

| Can a treatment adjustment of the precipitating drug prevent adverse drug reactions |

| Can switching the precipitating drug prevent adverse drug reactions? |

| Can the second drug have a beneficial effect on adverse drug reactions? |

| Is the benefit–risk balance of the prescribing cascade positive? |

| Area | Principle / Clinical Practice |

| Oligopharmacotherapy | Use only absolutely essential medications. |

| Zero tolerance for unnecessary drugs | Eliminate therapies without clinical indications. |

| Contextual pharmacotherapy | Take into account comorbidities and the individual situation of the patient. |

| Patient assessment | Before introducing a new drug, evaluate the entire pharmacotherapy, risk of interactions, and potential adverse effects. |

| Deprescribing | Regularly discontinue unnecessary or harmful medications. |

| Adverse drug reactions | - First, consider discontinuing dietary supplements; - Limit unnecessary self-medication; - Respond immediately to new symptoms. |

| Informed patient | Educate the patient: treatment goals, risks of polypharmacy, and the need to report adverse effects. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).