Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

30 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Protocol

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion Criteria

2.4. Endpoints

2.5. Ethical considerations

2.6. Statistical analysis

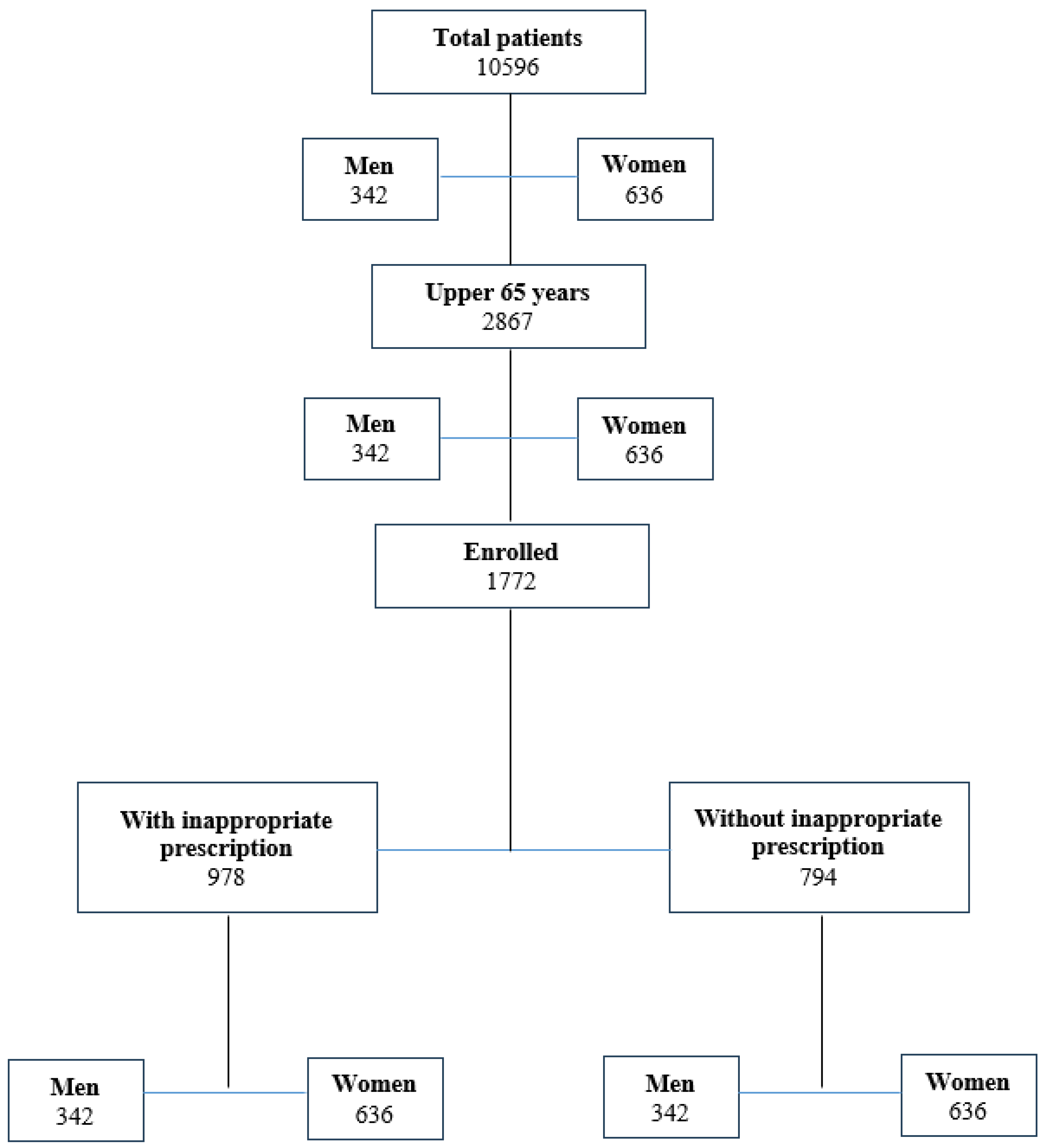

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

3.2. Inappropriate drug prescription

3.3. DIPS score

3.4. Risk evaluation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wastesson, J.W.; Morin, L.; Tan, E.C.K.; Johnell, K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: A narrative review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 1185–1196. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Roberts, M.S. Challenges and innovations of drug delivery in older age. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 135, 3–38. [CrossRef]

- Mangoni, A.A.; Jackson, S.H.D. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Basic principles and practical applications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 57, 6–14. [CrossRef]

- Palleria, C.; Di Paolo, A.; Giofrè, C.; Caglioti, C.; Leuzzi, G.; Siniscalchi, A.; De Sarro, G.; Gallelli, L. Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction and their implication in clinical management. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 601–610.

- Di Mizio, G.; Marcianò, G.; Palleria, C.; Muraca, L.; Rania, V.; Roberti, R.; Spaziano, G.; Piscopo, A.; Ciconte, V.; Nunno, N. Di; et al. Drug – Drug Interactions in Vestibular Diseases , Clinical Problems , and Medico-Legal Implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12936. [CrossRef]

- Breuker, C.; Macioce, V.; Mura, T.; Castet-Nicolas, A.; Audurier, Y.; Boegner, C.; Jalabert, A.; Villiet, M.; Avignon, A.; Sultan, A. Medication Errors at Hospital Admission and Discharge. J. Patient Saf. 2017, Publish Ah, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, L.; Alexandra, J.F.; Tesmoingt, C.; Eerdekens, C.; Macrez, A.; Papo, T.; Arnaud, P.; Papy, E. Medication reconciliation: A prospective study in an internal medicine unit. Drugs and Aging 2014, 31, 387–393. [CrossRef]

- Chiewchantanakit, D.; Meakchai, A.; Pituchaturont, N.; Dilokthornsakul, P.; Dhippayom, T. The effectiveness of medication reconciliation to prevent medication error: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 886–894. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Cione, E.; Siniscalchi, A.; Vasta, G.; Guerra, A.; Scaramuzzino, A.; Longo, L.; Muraca, L.; De Sarro, G.; Group, G.S.W.; et al. Is there a Link between Non Melanoma Skin Cancer and Hydrochlorothiazide? Curr Drug Saf 2022, 17, 211–216. [CrossRef]

- Staltari, O.; Cilurzo, F.; Caroleo, B.; Greco, A.; Corasaniti, F.; Genovesi, M.; Gallelli, L. Annual report on adverse events related with vaccines use in Calabria (Italy): 2012. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Rende, P.; Paletta, L.; Gallelli, G.; Raffaele, G.; Natale, V.; Brissa, N.; Costa, C.; Gratteri, S.; Giofrè, C.; Gallelli, L. Retrospective evaluation of adverse drug reactions induced by antihypertensive treatment. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, 47–50. [CrossRef]

- Zanon, D.; Gallelli, L.; Rovere, F.; Paparazzo, R.; Maximova, N.; Lazzerini, M.; Reale, A.; Corsetti, T.; Renna, S.; Emanueli, T.; et al. Off-label prescribing patterns of antiemetics in children: A multicenter study in Italy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 361–367. [CrossRef]

- Caglioti, A.; Rania, V.; Vocca, C.; Marcianò, G.; Arcidiacono, V.; Catarisano, L.; Casarella, A.; Basile, E.; Colosimo, M.; Palleria, C.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of ANTI SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Transplant Patients Treated with Immunosuppressants: A Real-World Pilot Study with a 1-Year Follow-Up. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Ferreri, G.; Colosimo, M.; Pirritano, D.; Flocco, M.A.; Pelaia, G.; Maselli, R.; De Sarro, G.B. Retrospective analysis of adverse drug reactions to bronchodilators observed in two pulmonary divisions of Catanzaro, Italy. Pharmacol. Res. 2003, 47, 493–499. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Colosimo, M.; Pirritano, D.; Ferraro, M.; De Fazio, S.; Marigliano, N.M.; De Sarro, G. Retrospective evaluation of adverse drug reactions induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin. Drug Investig. 2007, 27, 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Ferreri, G.; Colosimo, M.; Pirritano, D.; Guadagnino, L.; Pelaia, G.; Maselli, R.; De Sarro, G.B. Adverse drug reactions to antibiotics observed in two pulmonology divisions of Catanzaro, Italy: A six-year retrospective study. Pharmacol. Res. 2002, 46, 395–400. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Nardi, M.; Prantera, T.; Barbera, S.; Raffaele, M.; Arminio, D.; Pirritano, D.; Colosimo, M.; Maselli, R.; Pelaia, G.; et al. Retrospective analysis of adverse drug reactions induced by gemcitabine treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2004, 49, 259–263. [CrossRef]

- Muraca, L.; Scuteri, A.; Burdino, E.; Marcianò, G.; Rania, V.; Catarisano, L.; Casarella, A.; Cione, E.; Palleria, C.; Colosimo, M.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of a New Nutrient Fixed Combination Containing Pollen Extract plus Teupolioside, in the Management of LUTS in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy: A Pilot Study. Life 2022, 12, 965. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, G.; Di Mizio, G.; Palleria, C.; Siniscalchi, A.; Rubino, P.; Muraca, L.; Cione, E.; Salerno, M.; De Sarro, G.; Gallelli, L. Data recorded in real life support the safety of nattokinase in patients with vascular diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2031. [CrossRef]

- Gareri, P.; Gallelli, L.; Cotroneo, A.M.; Manfredi, V.G.L.; De Sarro, G. The art of safe and judicious deprescribing in an elderly patient: A case report. Geriatr. 2020, 5, 57. [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.R.; Hansten, P.D.; Chan, L.N. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann. Pharmacother. 2007, 41, 674–680. [CrossRef]

- DAVIES, D.F.; SHOCK, N.W. Age changes in glomerular filtration rate, effective renal plasma flow, and tubular excretory capacity in adult males. J. Clin. Invest. 1950, 29, 496–507. [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Garrido, E.M.; García-Garrido, I.; García-López-Durán, J.C.; García-Jiménez, F.; Ortega-López, I.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Estudio de pacientes polimedicados mayores de 65 años en un centro de asistencia primaria urbano. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2011, 26, 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Siniscalchi, A.; Palleria, C.; Mumoli, L.; Staltari, O.; Squillace, A.; Maida, F.; Russo, E.; Gratteri, S.; De Sarro, G.; et al. Adverse drug reactions related to drug administration in hospitalized patients. Curr. Drug Saf. 2017, 12, 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Kunakorntham, P.; Pattanaprateep, O.; Dejthevaporn, C.; Thammasudjarit, R.; Thakkinstian, A. Detection of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis and muscular related adverse events through data mining technique. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.E.; Russo, V.; Walsh, C.; Menditto, E.; Bennett, K.; Cahir, C. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in Older Community-Dwelling Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Drugs and Aging 2021, 38, 1025–1037. [CrossRef]

- Blom, D.J.; Hala, T.; Bolognese, M.; Lillestol, M.J.; Toth, P.D.; Burgess, L.; Ceska, R.; Roth, E.; Koren, M.J.; Ballantyne, C.M.; et al. A 52-Week Placebo-Controlled Trial of Evolocumab in Hyperlipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1809–1819. [CrossRef]

- Montastruc, J.-L. Rhabdomyolysis and statins A pharmacovigilance comparative study between statins. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2023, 89, 2636–2638. [CrossRef]

- Cuisset, T.; Frere, C.; Quilici, J.; Poyet, R.; Gaborit, B.; Bali, L.; Brissy, O.; Morange, P.E.; Alessi, M.C.; Bonnet, J.L. Comparison of Omeprazole and Pantoprazole Influence on a High 150-mg Clopidogrel Maintenance Dose. The PACA (Proton Pump Inhibitors And Clopidogrel Association) Prospective Randomized Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 1149–1153. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.J.; Chen, S.L.; Tan, J.; Lin, G.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xu, H.M.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Fan, H.W.; Xie, H.G. Increased risk for developing major adverse cardiovascular events in stented Chinese patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy after concomitant use of the proton pump inhibitor. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kuscu, F.; Ulu, A.; Inal, A.S.; Suntur, B.M.; Aydemir, H.; Gul, S.; Ecemis, K.; Komur, S.; Kurtaran, B.; Kuscu, O.O.; et al. Potential drug–drug interactions with antimicrobials in hospitalized patients: A multicenter point-prevalence study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 4240–4247. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, T.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Nabovati, E.; Eslami, S.; de Keizer, N.F.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Klopotowska, J.E. Heterogeneity in the Identification of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review, Critical Appraisal, and Reporting Recommendations. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 706–720. [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, M.S.; Panday, P.N.; Pranger, A.D.; Kosterink, J.G.W.; Alffenaar, J.W.C. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of antimicrobial drugs: A systematic review on oxazolidinones, rifamycines, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and beta-lactams. Pharmaceutics 2011, 3, 865–913. [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, D.; Gervasoni, C.; Corona, A. The Issue of Pharmacokinetic-Driven Drug-Drug Interactions of Antibiotics: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Glen, H.; Mason, S.; Patel, H.; Macleod, K.; Brunton, V.G. E7080, a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor suppresses tumor cell migration and invasion. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 309. [CrossRef]

- Vavrová, K.; Indra, R.; Pompach, P.; Heger, Z.; Hodek, P. The impact of individual human cytochrome P450 enzymes on oxidative metabolism of anticancer drug lenvatinib. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.R.; Morganroth, J. Update on Cardiovascular Safety of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: With a Special Focus on QT Interval, Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Overall Risk/Benefit. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 693–710. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.M.; Philbrick, A.M. Avoiding serotonin syndrome: The nature of the interaction between tramadol and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Ann. Pharmacother. 2012, 46, 1712–1716. [CrossRef]

- Anglin, R.; Yuan, Y.; Moayyedi, P.; Tse, F.; Armstrong, D.; Leontiadis, G.I. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 811–819. [CrossRef]

- Haghbin, H.; Zakirkhodjaev, N.; Husain, F.F.; Lee-Smith, W.; Aziz, M. Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleeding with Concurrent Use of NSAID and SSRI: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2023, 68, 1975–1982. [CrossRef]

- Zucker, I.; Prendergast, B.J. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics predict adverse drug reactions in women. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 32. [CrossRef]

| Phase | Change | Effect | Clinical risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Reduced active transport mechanisms | Reduced absorption of magnesium, calcium, iron, vitamin B 12 | Increased risk of osteopenia, osteoporosis, anemia |

| Reduced P-glycoprotein activity | Increased absorption of victim drugs | Development of ADRs | |

| reduced amount of dopadecarboxylase in the gastric mucosa | Increased absorption of levodopa | Development of ADRs | |

| Decreased secretion of secretion of hydrochloric acid and pepsin | Reduced absorption of basic drugs | Risk of undertreatment | |

| Distribution | polar drugs (water-soluble) have smaller volumes of distribution | Increased serum levels (eg., Gentamicin, digoxin, ethanol, theophylline, and cimetidine) | Development of ADRs |

| nonpolar drugs (lipid-soluble) have higher volumes of distribution | Increased in half life (eg., diazepam, thiopentone, lignocaine, and chlormethiazole) | Development of ADRs | |

| Metaboolism | reduction in first-pass metabolism | Increased bioavailability of drug undergoing extensive first-pass metabolism. Reduced bioavailability of pro-drugs | Increased risk of ADRs from propranolol and labetalol. Rediuced clinical effects of several pro-drugs (eg., enalapril and perindopril) |

| Renal Excretion | Reduced renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate | Reduced renal excretion | Development of ADRs |

| Disease | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases (Blood Hypertension, Atrial fibrillation) |

82.3 |

| Osteoarthritis | 79.5 |

| Diabeted mellitus type 2 | 26.2 |

| Depression | 18.7 |

| Impaired cognition, dementia | 16.8 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 13.3 |

| Urological diseases | 12.8 |

| COPD | 8.4 |

| Rheumatological diseases | 6.9 |

| Osteoporosis or osteopenia | 4.8 |

| Asthma | 1.2 |

| Hypothiroidism | 1.1 |

| Other | 1.6 |

| Characteristics | With PIP (n:794) | Without PIP (n: 552) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 76.3±7.3 | 76.8±8.5 |

| Men (%) | 41.3 | 46.6 |

| Women (%) | 58.7*§ | 53.4* |

| Current Smokers (%) | 5.2 | 4.8 |

| Overweight (%) | 53.6 | 52.8 |

| Chronic diseases (mean ± SD) | 4±2 | 5±2 |

| Drugs | Percentage | number |

|---|---|---|

| Omeprazole and esomeprazole | 25 | 199 |

| Atorvastatin and Simvastatin | 20 | 159 |

| Clopidogrel | 12,9 | 102 |

| Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin | 11 | 87 |

| SSRIs | 10,1 | 80 |

| Opioids | 9 | 71 |

| SNRIs | 6 | 48 |

| Benzodiazepines | 3 | 24 |

| NSAIDs | 3 | 24 |

| Drugs prescribed during hospital discharge | Drugs in therapy |

|---|---|

| Omeprazole and esomeprazole | citalopram (28), escitalopram (26), venlafaxine (25), tramadol (21), trazodone (12), aripiprazole (11), tizanidine (10), alfuzosine (9), domperidone (9), ciprofloxacin (9), amiodarone (9), vardenafil (8), levofloxacin (7), haloperidol (6), clopidogrel (5), moxifloxacin (4) |

| Atorvastatin or Simvastatin | esomeprazole (59), amlodipine (16), Sacubitril Valsartan (14), sitagliptin (12), ranolazine (9), amiodarone (9), tadalafil (8), dronedarone (6), warfarin (6), sildenafil (6), clopidogrel (3), diltiazem (3), ticagrelor (3), carbamazepine (2), everolimus (2), domperidone (1) |

| Clopidogrel | Omeprazole (22), esomeprazole (18), lansoprazole (16), rosuvastatin (12), repaglinide (9), fluoxetine (6), paroxetine (5), tramadol (5), tapentadol (4), venlafaxine (3), amiodarone (2), |

| Ciprofloxacin and evofloxacin | escitalopram (14), duloxetine (9), venlafaxine (6), tramadol (4), |

| omeprazole (10), metformin (9), simvastatin (7), betamethasone (3), paroxetine (3), fluoxetine (3), warfarin (2), furosemide (2), propafenone (1), ranolazine (1), zolpidem (1) | |

| diclofenac (6), ibuprofen (4), dutasteride (2) | |

| Fluoxetine and paroxetine | rivaroxaban (6), apixaban (4), dabigatran (4), diclofenac (6), clopidogrel (6), tizanidine (4), tramadol (4), triazolam (3), frovatriptan (3), furosemide (2), trazodone (2), oxycodone (2), triazolam (2), amiodarone (2), almotriptan (1), eletriptan (1) |

| Citalopram and escitalopram | omeprazole (7), tramadol (3), tizanidine (3), apixaban (2), trazodone (2), diclofenac (2), ibuprofen (2), ketoprofen (2), amitriptyline (2), buprenorphine (2), almotriptan (1) |

| Tramadol | omeprazole (7), gabapentin (7), paroxetine (6), amytriptiline (6), duloxetine (4), fluoxetine (2), oxycodone (2), alprazolam (1), diazepam (1) |

| Tapentadol | citalopram (6), escitalopram (3), paroxetine (3), Oxycodone (3), almotriptan (2), trazodone (2), sertraline (2), risperidone (2) |

| Oxycodone | escitalopram (6), paroxetine (3), Triazolam (2), gabapentin (1) |

| Venlafaxine | omeprazole (9), esomeprazole (9) flecainide (6), ciprofloxacina (5), azythromicin (4), zolmitriptan (2) buprenorphine (1) |

| Duloxetine | Trazodone (3), clobazam (2), rozatriptan (2), naproxene (2), etoricoxib (1) |

| Diazepam | omeprazole (16), tramadol (4), tapentadol (2), olanzapine (2) |

| Alprazolam and triazolam | tramadol (2) |

| Diclofenac and ketorolac | enoxaparin (8), venlafaxine (5), valsartan (5), furosemide (4), levofloxacin (2), |

| Drug 1 | Drug 2 | ADRs | Mechanism | Action | N patients | DIPS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram 20 mg once day | Lenvatinib 10 mg once day | Increase in heart rate | QT interval prolongation | Change citalopram to duloxetine | 2 | 6 |

| Esitalopram 20 mg once day | Lenvatinib 10 mg once day | Increase in heart rate | QT interval prolongation | Change escitalopram to duloxetine | 1 | 6 |

| Levofloxacin 500 mg once day | Lenvatinib 10 mg once day | Increase in heart rate | QT interval prolongation | Change Levofloxacin to Piperacillin/tazobactam | 1 | 6 |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg once day | Omeprazole 40 mg once day | Decreased activity of clopidogrel | Reduced liver activation of clopidogrel | Change omeprazole to pantoprazole | 7 | 6 |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg once day | Esomeprazole 40 mg once day | Decreased activity of clopidogrel | Reduced liver activation of clopidogrel | Reduce the dosage of esomeprazole to 10 mg | 1 | 6 |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg once day | Fluoxetine 20 mg daily | Decreased activity of clopidogrel | Reduced liver activation of clopidogrel | Change fluoxetine to sertraline | 5 | 6 |

| Omeprazole 20 mg daily | Methotrexate | Increased methotrexate toxicity | Reduced renal secretion of methotrexate | Stop omeprazole three days before the administration of methotrexate | 2 | 7 |

| Atorvastatin 20 mg daily | Sildenalfil 20 mg | Muscolar pain | CYP3A4 inhibition | Stop sildenafil change to vardenafil | 4 | 6 |

| Atorvastatin 20 mg daily | Clarithromycin 500 mg very 12 hours | Muscolar pain | CYP3A4 inhibition | Change clarithromycin to azythromicin | 1 | 6 |

| Inhibitors | Inductors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Calcium antagonists Amlodipine, Diltiazem, Felodipine, Nicardipine Nifedipine Verapamil Statins Simvastatin |

Antibiotics Clarithromycin, Erithromycin, Josamycin, Oleandromycin, Roxithromycin Telithromycin Ciprofloxacin, Norfloxacin |

Anticancer Imatinib, Irinotecano, Tamoxifene Hormonal therapies Ethinyl estradiol Levonorgestrel Raloxifene |

Atorvastatin Fluvastatin Lovastatin Simvastatin Tioglitazone Pioglitazone Rifampicin |

|

Central nervous system drugs Haloperidol, Bromocriptine Clonazepam, Desipramine Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Nefazodone Norclomipramine Nortriptiline Sertraline |

Antifungals Fluconazole, Itraconazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, voriconazole Antiretrovirals Amprenavir, atazanavir, delaviridine, efavirenz, indinavir, lopinavir, ritonavir, nelfinavir, nevirapine, saquinavir, tipranavir |

Other drugs Cimetidine, Disulfiram, Phenelzine Sildenafil Tadalafil Methylprednisolone Antiarrhythmics Amiodarone quinidine Food Bergamot Grapefruit juice |

Antiretrovirals Efavirenz Lopinavir Nevirapina Antiepileptics Valproate, Carbamazepine Oxcarbazepine, Phenobarbital Phenytoin Primidone Topiramate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).