1. Introduction

The protection of information systems and their components against cyber threats has become a major concern for many organizational managers and executives. As the frequency of such threats continues to rise, the information security sector has increasingly sought ways to address this challenge. One proposed solution is to insure organizations against cyber risks. The first cyber insurance products emerged in the early 21st century (Siegel et al., 2002), when the insurance market began offering policies designed to mitigate the financial consequences of cyber incidents (Majuca et al., 2006). These initial products were introduced in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom. According to several studies, the range of cyber insurance offerings remains most extensive in these countries (Bradford, 2015; Biener et al., 2015).

Assessing the potential financial impacts of cyber threats on an organization’s information environment is a primary focus for several research organizations and companies in the insurance industry worldwide. While we have numerous tools to analyze and quantify the level of risk associated with cyber threats, greater emphasis should be placed on articulating the potential financial repercussions of these threats. The scientific literature includes the work of various authors who have addressed this issue (Palson et al., 2020; Romanosky, 2016; Franke, 2017). Current methodologies for predicting the financial impacts of cyber threats on an organization’s information environment can be categorized into two approaches according to professional literature.

Insurance companies often utilize questionnaire surveys to determine insurance premiums, combining this approach with risk analysis methods for a given information environment (Woods and Simpson, 2017). However, this method does not provide a comprehensive analysis of all cyber threats and their potential financial impacts on economically significant areas. We believe that while a controlled questionnaire survey conducted by an insurance broker can yield some insights into the security environment of the investigated organization, it does not offer an in-depth analysis of the security context. Crucially, key processes necessary for estimating future financial damage from cyber threats often remain unexplored. Unlike other types of insurance, standard actuarial approaches cannot be effectively applied to cyber threat insurance. The primary reason for this is the unique nature of cyber threats and their potential evolution. As some authors stated, classical actuarial approaches rely heavily on claims data (Awiszus et al., 2023). To apply these actuarial procedures, it is also necessary to have statistical data available, which are often not complete and usable (Awiszus et al., 2023; Zeller and Scherer, 2021). While it is possible to model various future scenarios for property damage or health impacts related to other risk situations, such as natural disasters, creating similar models for cyber threats is much more challenging. This difficulty stems from the rapidly evolving nature of these threats and the high variability of their characteristics (Dacorogna and Kratz, 2023; Zeller and Scherer, 2021).

Artificial intelligence may also present a new cyber threat for information systems. From a cybersecurity perspective, artificial intelligence may pose a threat in the form of better detection of vulnerable areas in information systems and thus more accurate target determination. This new technology may also contribute to better sophistication of cyber threats, which may subsequently lead to less accurate predictions of cyber threats (Tao et al., 2021). The essence of cyber threats may thus change significantly in the coming years, which may be another new challenge for the area of predicting the financial impacts in area of cyber security (Bredt, 2019). The insurance industry should also start to respond much more quickly to this situation. Insurance products and contracts with insurance companies should be respond much more dynamically to the security situation in cyberspace. This situation could lead to new types of insurance services, where the insurance products would dynamically respond to changing conditions and thus the financial amount of insurance coverage would also be adjusted (Cremer, 2022; Bredt, 2019).

The scientific paper proposes a possible solution in the form of a method through which the financial impacts of cyber threats can be predicted. The proposed method contains possible ways of determining financial impacts in selected areas of the information environment. The paper contains seven chapters. The chapter Background and related works analyzes the most important scientific works in this area. This chapter is followed by a description of the methods that form the basis for the application of the proposed method for identifying possible financial impacts of cyber threats. Verification of the proposed method is carried out in the Application section at the selected university. The aim is to determine the possible financial impacts of cyber threats on its information environment. The chapter Results evaluates the results achieved, which are further discussed in the Discussion section. The discussion also mentions the possible contribution of our research as well as its applications to practice and research. This part of the contribution also discusses the limits and suitability of the proposed method. The conclusion of this paper summarizes the entire issue and predicts possible developments.

2. Background and Related Works

It is known among experts that the issue of determining the development and impacts of cyber threats on the information environment of an organization also includes other scientific fields due to its extensiveness. As stated by (Bentley et al., 2020), it is necessary to plan and carry out analyses of the information environment preventively. According to (Eling et al., 2016), the assessment of the impact of cyber threats is not based on a sufficient amount of data, procedures and metrics. The most important factor in this area is the lack of reliable data sets that are not always analyzed, which then leads to the creation of mere assumptions (Eling et al., 2023).

The convergence across contemporary cybersecurity research publications is predominantly evident in three methodological domains: stochastic modelling, event-driven analysis, and scenario-based modeling. In the field of stochastic methods, we can cite the work of (Eling and Wirfs, 2019) who in their research use an operational risk database to identify cyber losses, which they then analyze using statistical and actuarial methods. To distinguish between common and extreme cyber risks, they apply the method of peaks above the threshold, based on extreme value theory. The impacts of cyber threats from the perspective of event-driven analysis are addressed in their work by (Palson et al., 2020) who show who the main actors involved in cyber incidents are and how tree classification methods can be used to gain deeper insight into cyber risk indicators that have an impact on the financial impacts of incidents. Determining potential impacts based on scenario modeling is addressed in their research (Eling et. al., 2023), which analyzes the six most common cyber threats. The authors also point out possible economic losses, which can represent relatively serious impacts. Each domain represents a distinct but complementary approach to quantifying cyber risk and its economic implications. Studies such as (Aldasoro et al., 2020; Bentley et al., 2020; Orlando et al., 2021) employ sophisticated quantitative frameworks namely Value-at-Risk (VaR) calculations or CyVaR techniques with parametric frequency and severity distributions. These methodologies aim to translate multifaceted cyber threats into monetized risk indicators through actuarial or statistical modeling, enabling rigorous financial impacts assessment.

2.1. Approaches, Methods and Limits

Research based on methodology of (Cavusoglu et al., 2004 and Portela et al., 2023) utilizes event study designs to investigate ex-post market reactions following cybersecurity incidents. By examining abnormal stock returns and immediate financial loss patterns, these analyses provide empirical insights into how breach events propagate economic repercussions within affected organizations and sectors. Other possible perspectives on this issue include Pre-and post-attack impacts quantification studies, exemplified by (Assen et al., 2024) apply forward-looking models such as Monte Carlo simulations and threat modeling frameworks. These methods facilitate probabilistic forecasting of potential damages and resource allocation, supporting strategy.

Multiple studies (e.g., Aldasoro et al., 2020; Eling et al., 2016; Orlando et al., 2016) underscore the absence of consensus on cyber event definitions, data acquisition protocols, and maturity assessment metrics. These inconsistencies hinder cross-study comparability and constrain the development of unified risk evaluation frameworks. Innovative analytical techniques, such as those in research (e.g., QuantTM by Assen et al., 2024 and Subroto and Apriyana, 2019) face systemic challenges in embedding within operational workflows and user-centric platforms. The persistent misalignment between theoretical constructs and pragmatic deployment calls for translational frameworks that bridge academic and organisational domains.

The aggregated insights derived from multiple research studies delineate a prospective framework for enhancing the quantification of cyber impacts. This framework integrates predictive pre-attack methodologies with empirical post-incident analyses. It also incorporates advanced data-driven modeling, fosters methodological standardization, broadens the scope of impacts assessment, and emphasizes the modeling of systemic risks.

2.2. Advanced Assessment Methods

The development of cyber risk modeling mandates increased accessibility to anonymized datasets, stated in (Eling et al., 2016) and real-time telemetry, founded in (Eling et al., 2023). The deployment of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) frameworks, as posited in (Franco et al., 2024) enables granular factor calibration, facilitates adaptive risk modeling under dynamic threat conditions, and mitigates epistemic uncertainties inherent in traditional risk estimation paradigms. Establishing universally accepted definitions for cyber events, harmonized metrics for quantifying risk exposure, and unified protocols for loss assessment (Eling et al., 2016; Aldasoro et al., 2020; Eling et al., 2023) are prerequisites for constructing interoperable risk model.

Within the surveyed corpus of cybersecurity literature, a two trends emerges regarding algorithm selection for risk quantification. Specifically, researchers exhibit a discernible preference for Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Naïve Bayes (NB) within traditional machine learning (ML) paradigms, while concurrently emphasizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). SVMs are consistently favored for their robustness in classification tasks, especially in high-dimensional cybersecurity contexts. Their capacity to construct optimal hyperplanes enables effective separation of complex data classes. Studies such as (Ahmadi-Assalemi et al., 2022; Ali et al., 2025) underscore SVMs' utility in accurate risk scoring.

However, SVMs impose substantial computational burdens, particularly in scenarios involving large-scale or multi-class datasets. The One-vs-Rest strategy introduces inefficiencies that challenge real-time deployment in dynamic threat environments. Naïve Bayes, while less computationally intensive, offers probabilistic classification that is both interpretable and effective, particularly under the assumption of feature independence.

2.3. Machine and Deep Learning

CNNs and LSTMs are increasingly adopted due to their proficiency in learning hierarchical representations and temporal dependencies, respectively. They point out this fact in their research (Huang et al., 2022). CNNs extract spatially correlated features, making them suitable for structured input formats such as network traffic matrices. LSTMs model sequential dependencies within time-series data, proving effective for applications requiring long-term contextual understanding, such as anomaly detection over extended periods. The dichotomous adoption of these algorithmic frameworks is largely dictated by the nature of the input data, the computational constraints of the deployment environment, and the specific objectives of the cybersecurity task domain. Similar to Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) exhibit substantial resource demands during training and deployment. These architectures typically necessitate extensive labeled datasets and high-performance computational infrastructure to achieve effective model convergence and performance optimization. These challenge is addressed by some authors (Ali et al., 2025), who emphasize that the computational complexity and training duration scale proportionally with the architectural depth of CNNs. Their research addresses concerns related to model scalability and training efficiency, advocating for techniques that mitigate the computational burden without compromising model accuracy.

As we can see, the studies conducted suggests a multidimensional framework for quantifying cyber-related impacts by integrating pre-incident forecasting methodologies with post-incident analytical techniques. The proposed method offers a comprehensive approach to cyber risk assessment that enhances both predictive accuracy and post-event evaluation fidelity.

3. Materials and Methods

Given the nature of cyber threats discussed in this post, insurance against these risks is often not fully effective. Additionally, predicting cyber threats and their financial impacts is a complex process that requires a multidisciplinary approach, leading to inaccuracies in estimating the appropriate amount of insurance coverage (Schwartz, 2019). Evidence for this assertion can be seen in cases where insured organizations received insurance payouts for cyber threats that largely fell short of covering their actual damages. It is crucial for insurance institutions to find it beneficial to insure specific organizations against cyber threats and their consequences. However, this perspective must also align with the interests of the insured organization, necessitating a balance between the insurance premium amount and the reality of the risks involved (Zhaoxin L. et al., 2022; Marotta et al., 2017; Young et al., 2016).

The issue of predicting cyber threats in relation to the time dimension represents a critical new aspect that is essential based on our current understanding. Each cyber threat evolves over time, both in terms of its nature and its severity. Cyber threats are changing rapidly (Awiszus et al., 2023). In recent years, for instance, the landscape of malware attacks, which encompasses all forms of malicious code, has undergone significant transformation. New types of malicious software are continually emerging, exhibiting substantial differences in structure and intended purpose. These new forms of cyber threats are often much more sophisticated than traditional malware (Tunggal, 2023). Therefore, it is vital to consider this dynamic evolution in the prediction of cyber threats and their financial impacts on an organization’s information environment.

Furthermore, one important factor in determining the potential financial impacts of cyber threats on an organization’s information environment is the time frame. The time dimension represents the evolution of a cyber threat scenario as it develops. It is hypothesized that the longer a cyber threat persists, the more severe its impacts on the organization’s information environment may become. The second aspect of this issue pertains to the relevance of the cyber threat (Erola et al., 2022). The severity of a cyber threat changes over time; thus, if the duration of a threat is shorter, its effects tend to be less significant. Conversely, if a cyber threat persists for an extended period, its potential impacts on the organization’s information environment can be much more serious (Millaire et al., 2018).

The method presented in this paper, developed by the authors, has evolved from 2015 to the present. During the period from 2015 to 2019, the fundamental phases of the method were established, along with options for verification. Since 2019, the method has been further refined and enhanced with new insights. These scientific advancements are grounded in the current landscape of cyber threat insurance. By utilizing time series analysis, the method enables more accurate results that encompass not only the evaluation of potential impacts from cyber threats but also the time dimension associated with the progression of these threats.

Time series analysis is a statistical method used to examine data that follows a chronological order. In the field of cyber security, understanding the nature of cyber threats and predicting their potential development is crucial. When we have statistical data on the progression of a cyber threat over time, we can create probable future scenarios for that threat's evolution. However, effectively utilizing this type of data requires a clear understanding of the specific challenges in this area, particularly the issue of comparability. To compare individual values in short-term interval time series, it is essential to relate these values to equally long-time intervals. Before conducting a time series analysis that is materially and spatially comparable, it is important to adjust the time series to account for calendar variations (Awiszus et al., 2023):

where:

yt is the value of the cleaned indicator,

kt is the number of calendar days in the relevant period and

= 30 or 365/12 = 30,4167 days is the average number of calendar days (Montgomery and Runger, 2024).

where: yt is the value of the cleaned indicator, pt is the number of calendar days in the relevant period and is the avarage number of days in the same period (Montgomery and Runger, 2024).

However, using time series analysis to predict the development of specific cyber threats involves certain risks. A key concern is the dynamic nature of cyber threat occurrences during the monitored time period. Significant fluctuations in the frequency of a particular event within a given time interval can impact the accuracy of the predictions.

To express the potential financial impacts of cyber threats, a mathematical model has been proposed. This formula can be particularly useful for predicting the possible financial repercussions of cyber threats on an organization's information environment. The individual components of the formula are based on standard risk assessment approaches; however, we have made slight modifications and enhancements to the original mathematical model. In addition to incorporating the probability-risk relationship, we also included the interaction between the cyber threat and the identified vulnerable elements (Pavlík, 2019).

The proposed mathematical formula for determining the risk is as follows:

where:

R represents the degree of risk,

P denotes the probability of a threat,

E signifies the value of vulnerable elements, and

V indicates the vulnerability of those elements to cyber threats. The established definition of risk has been expanded to include the relationship between the value of vulnerable elements and their vulnerability, as this connection is crucial for expressing the potential financial impacts of cyber threats.

Another area that is extremely important for predicting the development of cyber threats and their possible impacts is the valuation of significant assets of the organization. For these purposes, it is necessary to define the areas of the organization's information environment in which these assets are located. It is very important to divide the selected assets into tangible and intangible. In our paper, we selected the assets that are most often affected by the effects of cyber threats, primarily from the point of view of financial damages. These are mainly:

Hardware. The area of hardware includes not only computer devices and their accessories, but also other computer components that ensure the functions of the information system. We can apply these approach of valuation option for all types of hardware (Warren et al., 2023).

- ➢

Valuation at acquisition costs, this method is applied in the case of assets that are acquired for consideration (the price includes related costs such as installation and transportation, patents and licenses or exploration, geological and other works). Costs re-lated to the purchase price may also include interest on the loan.

- ➢

Repurchase valuation costs represents the price for which the asset was acquired at the time of its entry into accounting, i.e. a deposit of tangible assets, tangible assets as a gift or tangible assets acquired free of charge on the basis of financial leasing (in the case when the actual costs of creating the asset cannot be ascertained).

- ➢

Actual costs are tangible assets that have been created by the business itself. These are direct or indirect costs that were incurred in the course of production or other activities (Warren et al., 2023).

Software. For the purposes of this paper, the amount of costs that would have to be incurred to reinstall the software in the event of a breach will be used. Since the organization owns a license to operate the software tools, this is not necessary repurchase the software at a new price. There may also be a situation where the software is acquired and tied to the hardware it was purchased with, however, this possibility is not very likely in the case of small and medium enterprises. If were necessary to reinstall the software due to a cyber threat, the price of the software could be set based on the demand for the product. Pricing of software is also can be stated on the base of competitive price determination on the market. (Lehmann and Buxmann, 2009).

-

Fees associated to the occurrence of a cyber threat can be applied in various situations. If the organization primarily focuses on production, it may face sanctions for failing to comply with the production plan. This situation can occur in the event of a disruption in the function of the organization's information system, whose main task is to ensure the operation of production machines. If the required number of products were not fulfilled within the time schedule, the organization would also incur large financial losses. Another entity that can impose sanctions on a given organization is the competent supervisory authority. This policy is governed by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

No predefined formula can be used to represent this category financially. The amount of the fine is always an individual matter and depends on supplier-customer relation-ships. In the case of the general GDPR regulation, the amount of fines is set between 10 000 000,- Euro and 20 000 000,- Euro or 4 % of the company's total turnover (Pavlík, 2019).

Lost turnover. This mathematical formula can be utilized when an organization is unable to produce certain products or services. Originally designed for the production of tangible goods, the formula can also be adapted for organizations that produce digital products or services. For the digital sector, the formula will require adjustments to account for the duration when services cannot be provided to customers or other entities. This calculation should include the financial losses incurred during the period when digital products and services are unavailable.

The following formula is designed to express lost turnover (6):

where:

Uz is lost turnover,

CVh is the price of a normal number of products made in one hour and

Hv is the number of hours when the products are not produced (Pavlík, 2019).

Data reconstruction and recovery costs. The cost of data reconstruction and recovery can be defined as the costs incurred for the recovery of data resources, which can be represented by hardware and software resources. In the event of a breach of these data resources, stored or backed-up data may be irretrievably lost or damaged. It is also possible to determine the average cost of lost or stolen data from available statistical sources. This average cost is reported to be 141,- USD per person (Ponemon Institute, 2017). The following formula can be used (7):

where: NR is data reconstruction costs, CD is the cost of lost or stolen data for one person and PD is the number of data items that can be lost or stolen.

Damage to reputation. To financially quantify an organization's reputation, it is essential to define what this term encompasses. In the context of insurance against cyber threats, “damage to reputation” refers to the future financial losses that could result from a cyber threat affecting specific areas of the organization. These areas include suppliers, customers, and sponsors. The financial resources potentially lost by the organization over a certain period due to such an adverse event represent this damage. The organization’s reputation, also known as goodwill in economics, can be expressed in financial terms using a mathematical framework. In this case, it is mainly about advertising and the image of the organization. In the area of advertising and image, the organization is evaluated as a whole, not only based on certain areas. To express the financial amount that reflects the area of advertising and image, it is necessary to measure the profitability of investments in this category. Furthermore, it is necessary to take into account the synergy that the company creates in order to reach the market (8).

In every organization, employees and managers invest their time, money and energy in creating the image of the organization. This process is primarily focused on approach-ing new customers, suppliers, and customers and maintaining existing contacts. For this reason, the calculations in this category are focused on this point (Romanosky, 2016; Bank of Scotland, 2020).

where:

RI is advertising and image,

PPK is average income per client,

Nki is new clients per year,

Zki is lost clients per year,

Nir is advertising costs per year and

n is the value of the observed period

For the completeness of the expression of this indicator, it is necessary to add the time factor, i.e. discounting for the next year. The discounting formula is as follows (9):

where:

PPK is average income per client,

Xi is annual income from trades and

Nki is number of clients per year.

Costs of reporting data loss or leakage to supervisory authorities. When insuring against cyber threats, the costs of reporting data loss or leakage to supervisory authorities must also be considered. According to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), personal data breaches must be reported to the relevant supervisory authority within 72 hours. This category also includes notifications and communications with other parties affected by the data or information breach. This issue is also closely related to maintaining the reputation of the organization (Ponemon Institute, 2017). For the purpose of expressing this parameter, the following formula may be used (10):

where: NU is the cost of loss or data leakage notification, MZZ is the number of customers or other entities that may be affected by loss or data leakage, HM is the hourly wage of employees who will be in contact with the entities concerned and TU is the number of hours spent on contacting the affected entities.

To determine the potential financial impacts of selected cyber threats on identified endangered elements, we need to outline the entire methodology and its application. For better clarity, we have divided the proposed method into several phases.

Application of method

First phase: economic part (appreciation of endangered elements of the organization's information environment). In this phase, with the help of the proposed mathematical formulas, it is appreciated that the endangered elements in the information environment of the selected organization are defined.

Second phase: IT security part (assigning a significance value to individual endangerered elements and selected cyber threats).

The third phase: interaction (expressing the interaction between cyber threats and endangered elements). This phase is aimed at identifying the most serious cyber threats in relation to the possible financial impacts on defined endangered elements.

The fourth phase: prediction (predicting the development of the identified most serious cyber threats over time). In this phase, the possible development of identified cyber threats is predicted using the application of time series, from the point of view of the time dimension. The goal of this prediction should be a more accurate estimate of the development and impacts of selected cyber threats.

Fifth phase: financial impacts (expressing the financial impacts of selected cyber threats on the organization's information environment).

4. Application

Based on the defined application phases of the proposed method, we believe it is possible to identify the potential financial impacts of cyber threats on a selected organization. For this example, we present an unnamed university in the Czech Republic. Established in 2001, this university comprises six faculties, offering a total of 209 study programs that range from humanities and economics to management studies and IT. Currently, it serves approximately 10,000 students.

The organization has implemented two information systems: the STAG system, which is used by both employees and students, and the SAP information system, which manages economic operations and is exclusively utilized by university staff. The hardware was valued based on acquisition costs, as described in the Methods and Materials section, and included all tangible hardware. A list of hardware was compiled following discussions with the university‘s managers.

The software‘s value was assessed according to the software licenses purchased over the years, with insights gathered from IT experts at the university. The potential fees were estimated based on the possible financial impacts on the information environment, particularly in a scenario where sensitive data concerning employees or students is compromised. The potential fees were calculated using the most serious case of data leakage, as the Czech Republic‘s law stipulates different fees for data breaches. The maximum financial penalty for sensitive data leakage is set at 5,000,000 CZK (€198,687) according to the relevant regulations.

Since the university does not generate any turnover, lost revenue was not determined. Reputation was quantified using a mathematical formula defined in the Methods and Materials section, identifying students as clients whose income can be affected by the university‘s reputation. This relationship can significantly influence the university's standing.

To estimate the financial implications for data reconstruction and recovery costs, a mathematical formula outlined in the Methods and Materials section was applied, and discussions were held with IT experts from the university. Finally, the costs associated with reporting data loss or leakage include the financial implications of communicating with other authorities due to the breach. This analysis utilized the most severe scenario, wherein the university could potentially lose all sensitive data regarding employees and students.

Table 1.

First phase: economic part (own resource).

Table 1.

First phase: economic part (own resource).

| Endagered Element |

Price of endangered element |

| Hardware |

213 832 487, - € |

| Software |

1 480 541, - € |

| Fees |

198 687 € |

| Reputation |

225 185 237, - € |

| Data reconstruction and recovery costs |

31 630 118, - € |

| Costs of reporting data loss or leakage |

544 162, - € |

| The endangered elements of the university are valued at a total amount |

472 871 232, - € |

Selected risk analysis methods are employed to model the impacts of various cyber threats. This section involves assessing the individual threatened elements of the organization based on their significance. Each element is assigned a specific value reflecting its importance to the organization, using a rating scale from 1 to 5, where 5 represents the most critical endangered element and 1 denotes the least important. Additionally, cyber threat scenarios and the corresponding degrees of vulnerability to these threats are identified (see

Table 2). Ultimately, the results of this entire process are represented in a risk matrix.

The second step is to identify cyber threats and vulnerabilities. Possible causes of vulnerability were defined for the endangered elements that were identified in the previous step. To determine the severity of the cyber threat, a numerical scale from 1 to 5 is used here (

Table 3). The number 5 is the most likely cyber threat and the number 1 is the least likely cyber threat. In this case, the following decimal range is used for each numerical value.

Based on the degrees of probability, individual cyber threats are then assigned a value that indicates the possible level of realization of the selected cyber threat (

Table 4).

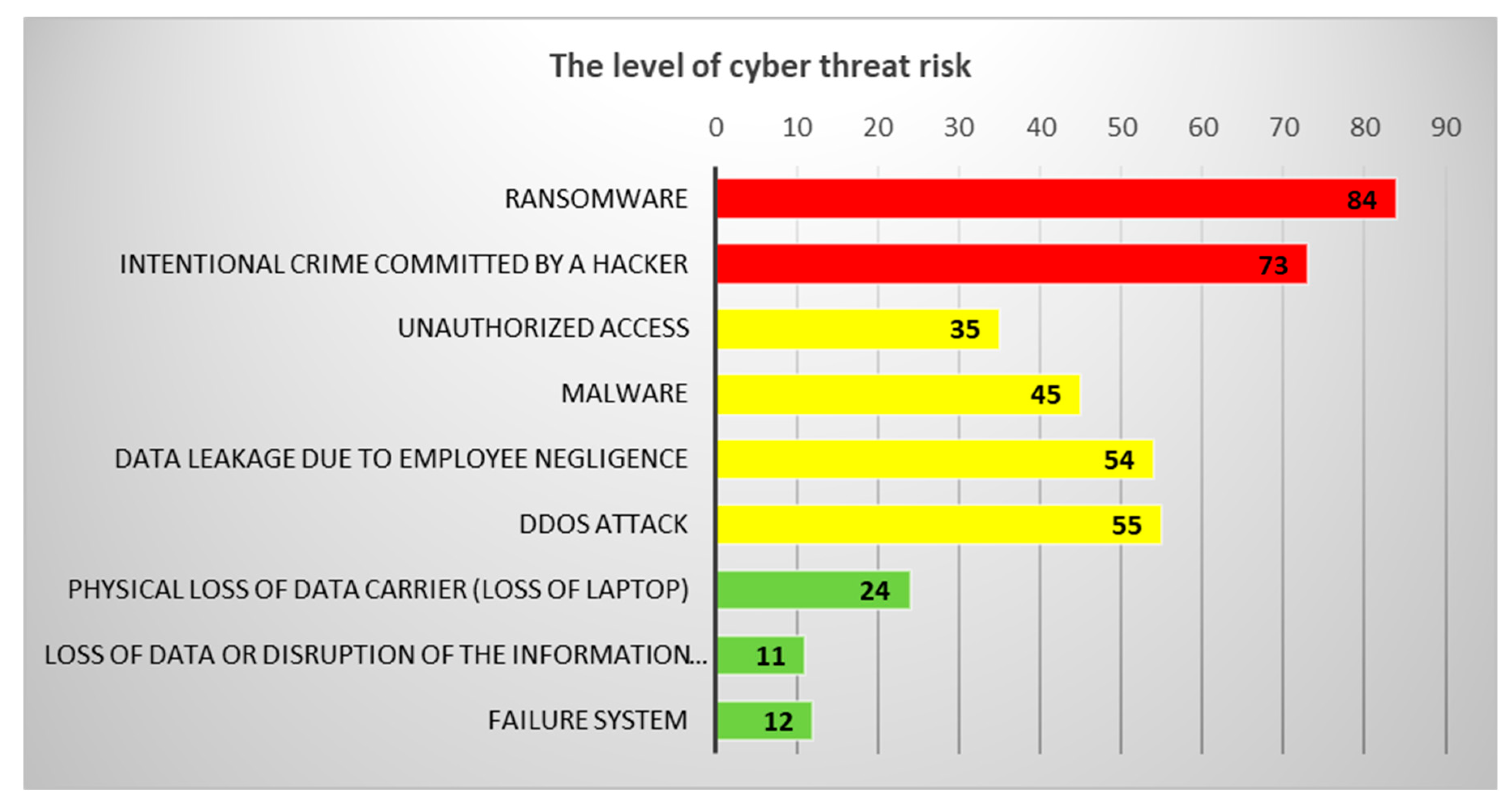

The fourth step is to perform a risk analysis in order to express the interaction of individual cyber threats with defined endangered elements. Expression of the interaction of these three indicators was carried out on the basis of the design of the risk matrix. In this risk matrix, selected cyber threats and their assigned values were compared with the endangered elements of the organization's information environment and their values. If there was an interaction of these two indicators (which was not always), in this case a value was determined that expresses the degree of vulnerability of the endangered element to a cyber threat. A scale from 1 to 5 was again used to determine the interaction between a cyber threat and a given endangered element, with the number 5 indicating the most likely interaction between a cyber threat and a given endangered element. The number 1 the least likely interaction between a cyber threat and a given endangered element. To better express the degree of risk, each level is assigned a colour resolution (

Table 5).

The next step is to create a risk chart in which the probability of the threat, the value of the endangered element and the vulnerability of the endangered element to cyber threats are expressed

. The level of risk is always coloured according to the proposed scale. The resulting values, which are presented in this chart, are the average values of all interactions between cyber threat and endangered elements. The values of these interactions are obtained on the basis of mathematical formula (1), in which the probability of a cyber threat, the value of an endangered element (impact) and the vulnerability of an endangered element to cyber threats (

Figure 1).

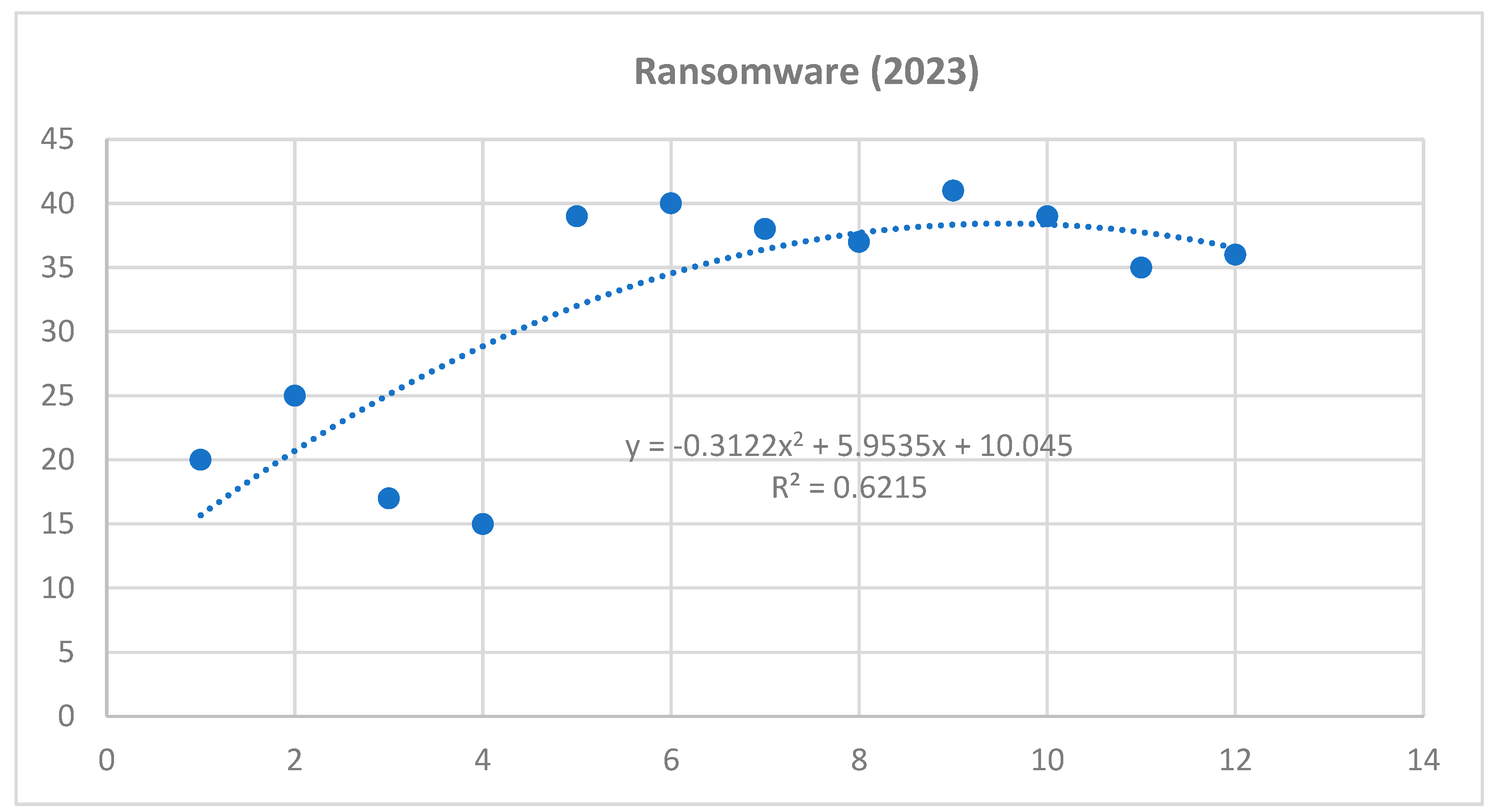

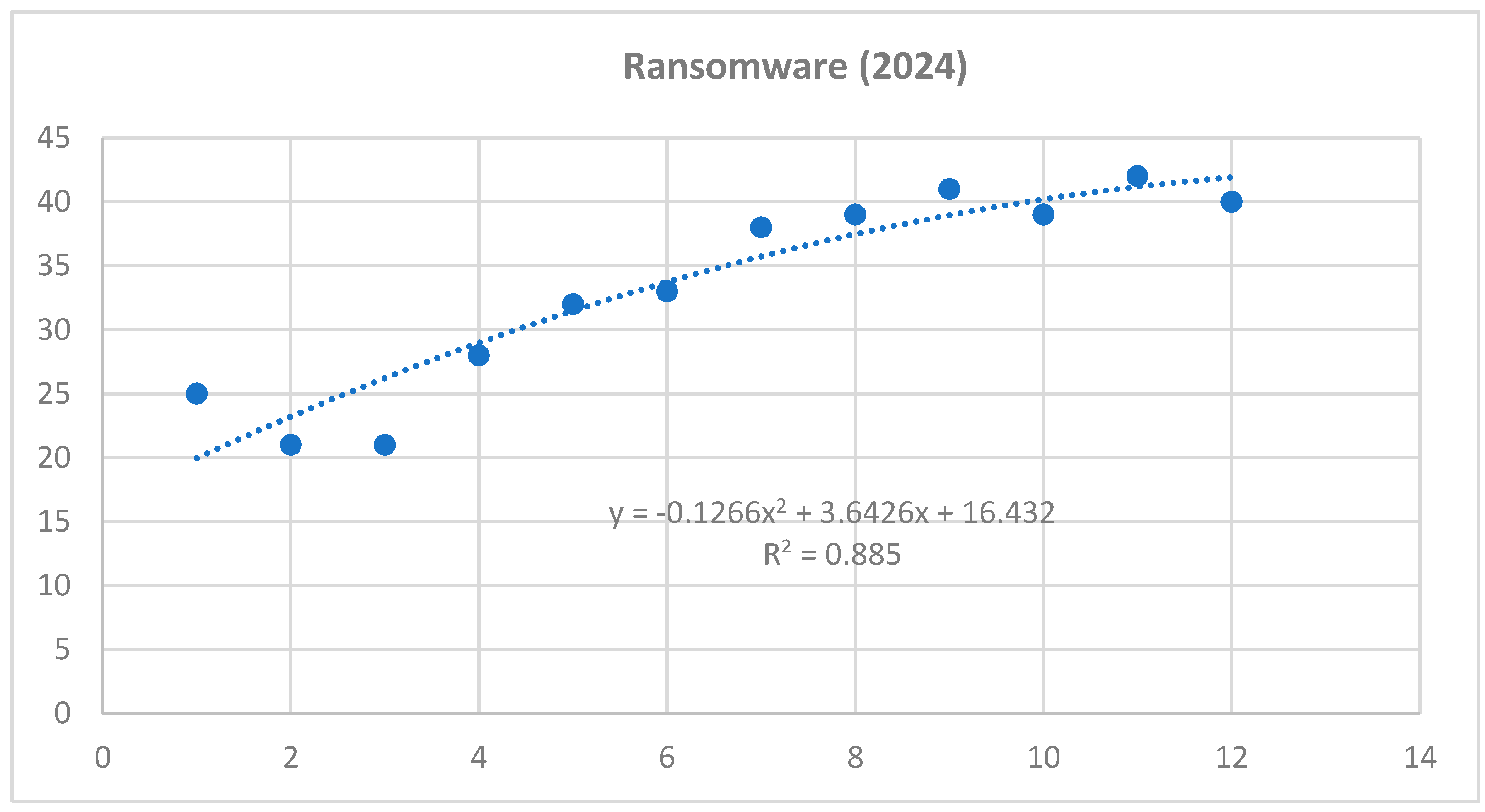

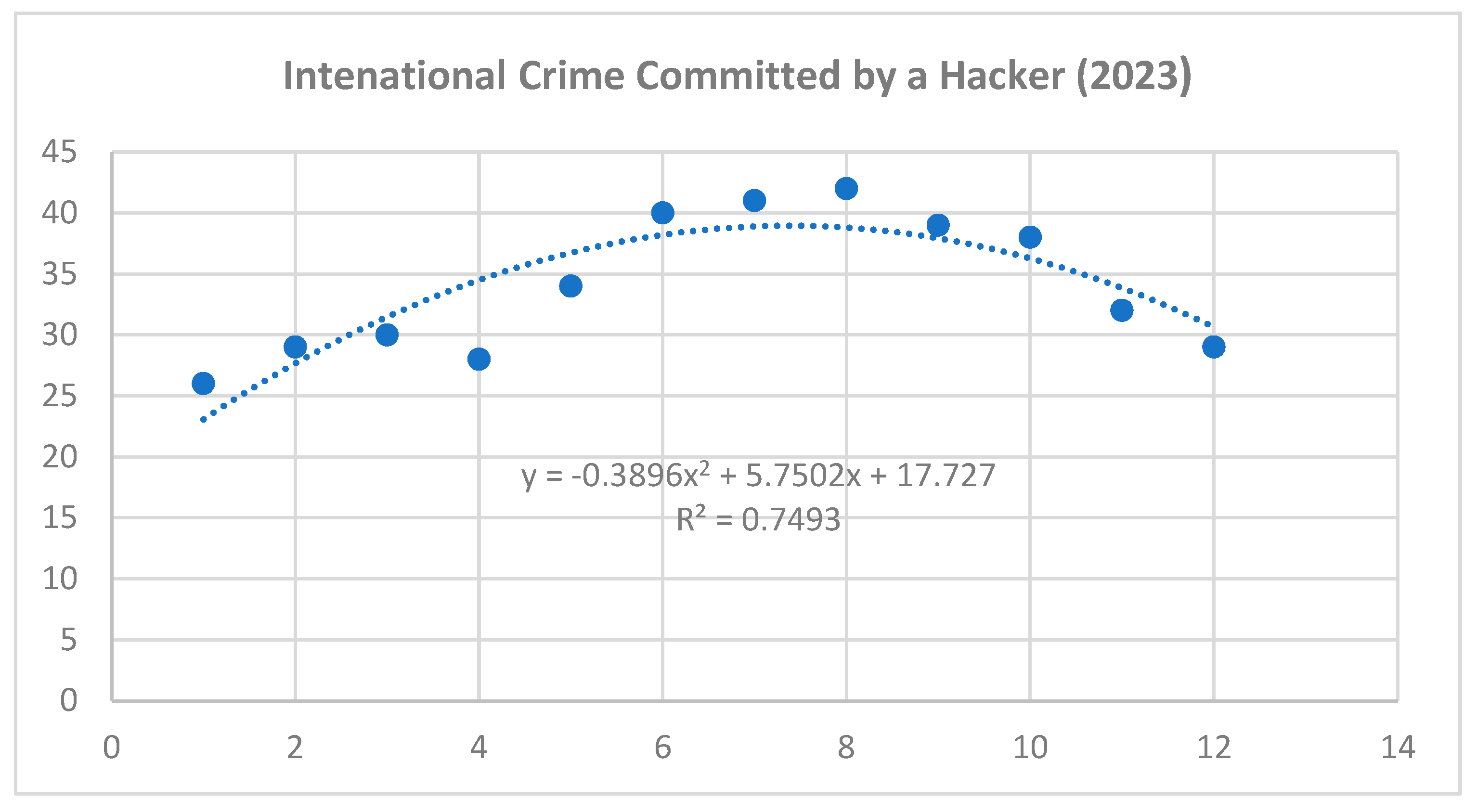

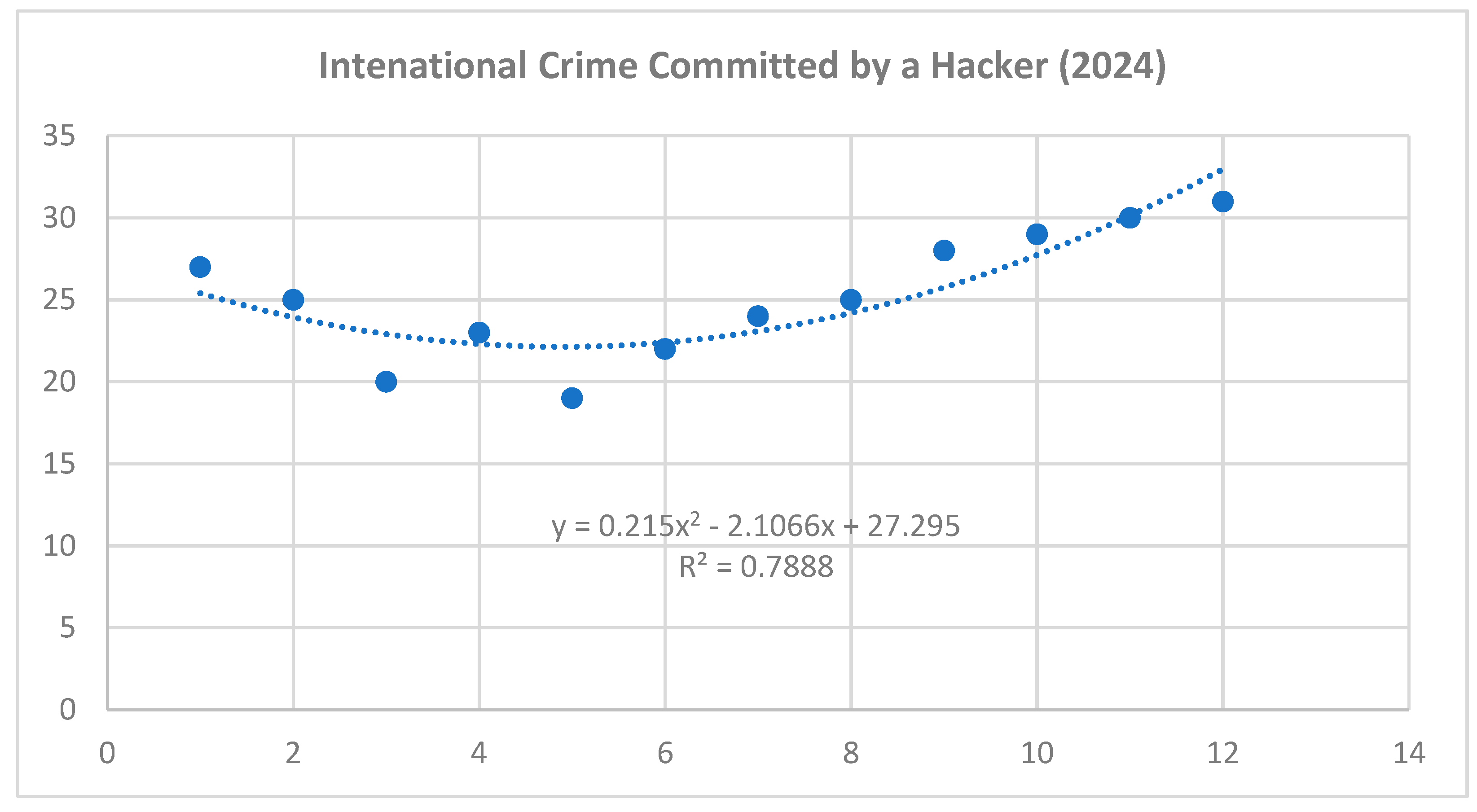

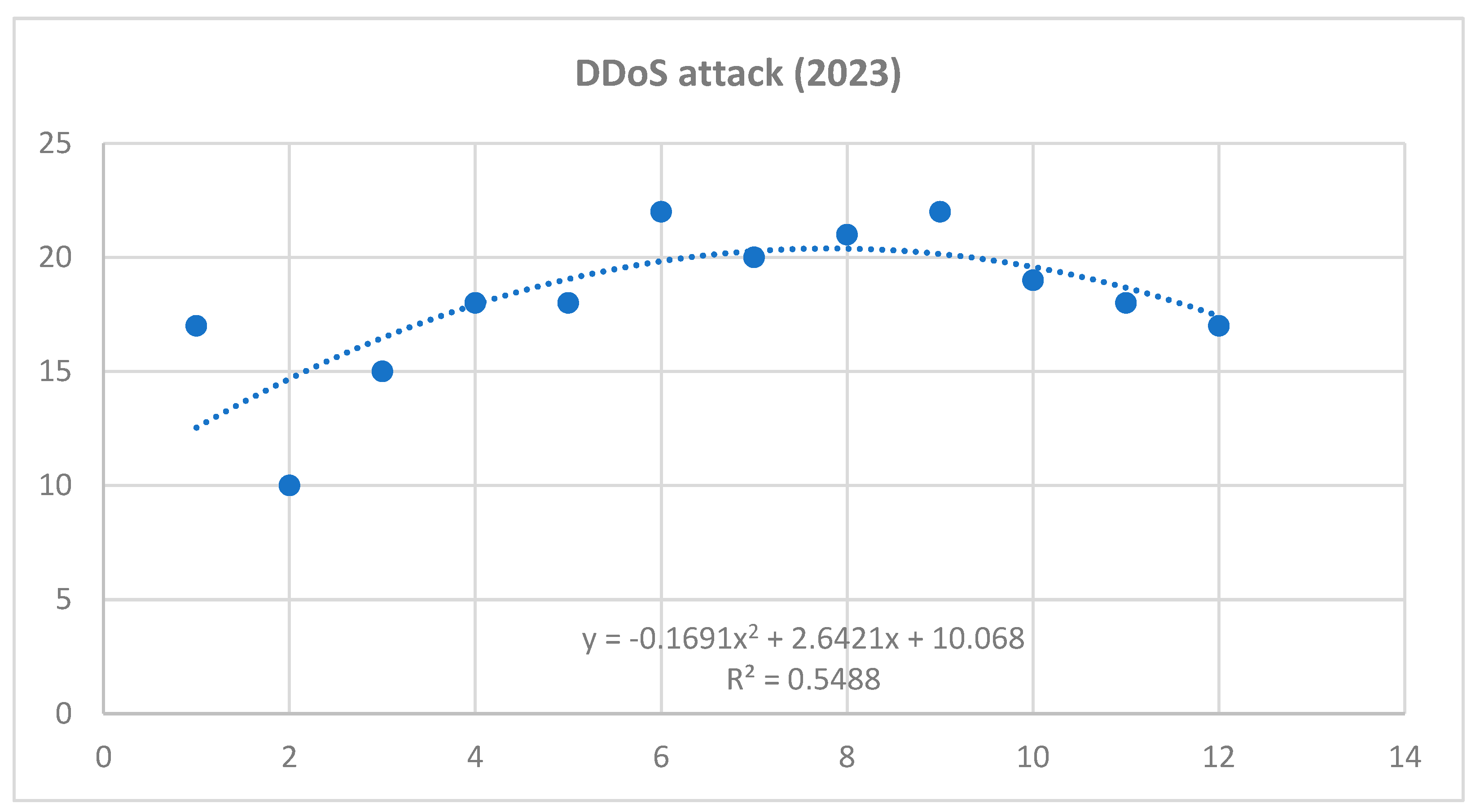

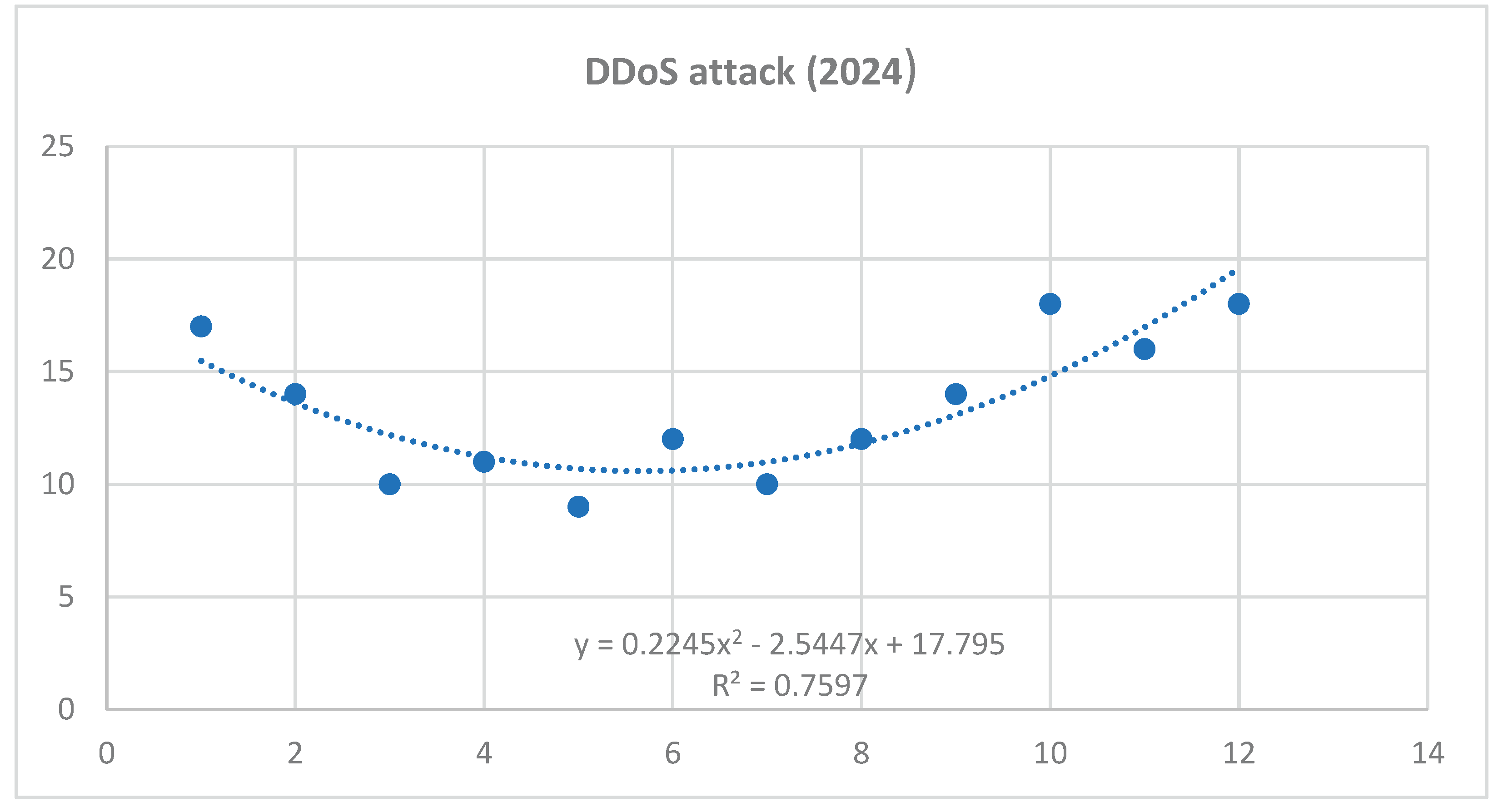

Based on the obtained results of the interaction analysis, we can predict the possible future development of selected cyber threats. For the purposes of our research, we have selected the three most serious threats that have the highest risk scores. It can be stated that the most serious cyber threats are Ransomware, Intentional Crime Committed by a Hacker and DDoS attack. As part of predicting the possible future development of these threats, a polynomial function was applied within the time series. Applying this function provides a more accurate prediction compared to a linear or exponential function. Selected professional studies and statistics were used as a basis for the input data, in which it was possible to analyze data related to the frequency of selected cyber threats in 2021 and 2022.

Prediction: If we want to predict the development of this cyber threat over time, it is necessary to insert the desired month into the polynomial function for x. The measured values in the graph are always for the past 12 months. We made a prediction using polynomial function formulas for 4 months (i.e. until April 2024), when this paperwas finalized (

Figure 3, 5 and 7).

Based on the obtained values, we can say that the development of the cyber threat of ransomware, international crime committed by a hacker and DDoS attack will inrease in the next quarter of 2024. However, these threat remains very significant, as a certain frequency of attacks can be expected (

Table 6).

Figure 2.

Time series for ransomware cyber threat – year 2023 (own source).

Figure 2.

Time series for ransomware cyber threat – year 2023 (own source).

Figure 3.

Time series for ransomware cyber threat – year 2024 (own source).

Figure 3.

Time series for ransomware cyber threat – year 2024 (own source).

Polynomic function for Ransomware attack:

Prediction for year 2025

January 2025: = -0,1266*169 + 3,6426*13 + 16,432 = 42,3904

February 2025: = -0,1266*196 + 3,6426*14 + 16,432 = 42,6148

March 2025: = -0,1266*225+ 3,6426*15 + 16,432 = 42,586

April 2025: = -0,1266*256 + 3,6426*13 + 16,432 = 42,304

Figure 4.

Time series intenational crime committed by a hacker cyber threat – year 2023 (own source).

Figure 4.

Time series intenational crime committed by a hacker cyber threat – year 2023 (own source).

Figure 5.

Time series intenational crime committed by a hacker cyber threat – year 2024 (own source).

Figure 5.

Time series intenational crime committed by a hacker cyber threat – year 2024 (own source).

Polynomic function for DDoS attack:

Prediction for year 2025

January 2025: = 0,215*169 - 2,1066*13 + 27,295 = 36,2442

February 2025: = 0,215*196 - 2,1066*14 + 27,295 = 39,9426

March 2025: = 0,215*225 - 2,1066*15 + 27,295 = 44,071

April 2025: = 0,215*256 - 2,1066*16 + 27,295 = 48,6294

Figure 6.

Time series for DDoS attack cyber threat – year 2023 (own source).

Figure 6.

Time series for DDoS attack cyber threat – year 2023 (own source).

Figure 7.

Time series for DDoS attack cyber threat – year 2024 (own source).

Figure 7.

Time series for DDoS attack cyber threat – year 2024 (own source).

Polynomic function for DDoS attack:

Prediction for year 2024

January 2025: = 0,2245*169 - 2,5447*13 + 17,795 = 22,6544

February 2025: = 0,2245*196 - 2,5447*14 + 17,795 = 26,1712

March 2025: = 0,2245*225 - 2,5447*15 + 17,795 = 30,137

April 2025: = 0,2245*256 - 2,5447*16 + 17,795 = 34,5518

5. Results

Modeling the development of cyber threats using time series can thus help predict the frequency of occurrence of selected cyber threats and thus also implement effective measures that should prevent or mitigate possible adverse impacts. Based on this prediction, it is also possible to compare the severity of cyber threats and their development over time from the point of view of estimating possible financial impacts.

The last step of the prediction is to identify the most serious scenario of a cyber threat and to financially express the possible impacts of this threat on the information environment of the university. To achieve this goal, the Saaty method is applied here. The following

Table 7 is provided to use this method and express the preferences of the individual criteria.

The outcome of this step is to derive the upper right triangular portion of the preference magnitude matrix, which is sometimes referred to as the Saaty matrix or the matrix of relative importance.

Table 8 presents a comparison of selected cyber threat scenarios with the highest levels of risk, measured in terms of impact and financial losses within the vulnerability matrix. The goal of this analysis is to identify one of the most significant cyber threats that could profoundly affect an organization and its information system.

To determine the criteria weights, we use the geometric mean of the rows from the Saaty matrix, with these values listed in the final column. By standardizing these row geometric means, we obtain the standardized weights for our set of criteria.

Based on the analysis conducted using the Saaty method, it is evident that the most serious threat with the potential for the greatest impact on the organization is ransomware (

Table 8).

The next step is to express the financial impact on the organization and its information environment, which is characterized by defined endangered elements. For the purpose of expressing financial damage, an evaluation scale will be used, which is based on the level of cyber threat risk, which was presented in the previous steps.

The table shows the severity levels of the threat, which is based on the range of the most serious risks, which is listed in the chart for the level of cyber threat. Based on the achieved results, a scale for the level of medium risk is proposed. The minimum value that can be achieved is 66 and the highest that can be assigned in this risk category is 125. The proposed percentage scale for determining possible financial impacts is determined based on the extent of the highest level of risk listed in

Table 9. The procedure for determining the degree of severity is as follows:

in the graph of level of cyber threat risk, the threat that was identified in the Saaty method analysis as the most serious is selected,

for this threat, the sum of all values that appear in the given matrix is performed (i.e. the interaction of the endangered element and the threat),

the total is divided by the number of interactions,

the value obtained by this mathematical operation is assigned a range of values in the table with the appropriate percentage,

this percentage is calculated from the amount that was determined at the beginning of the whole process, i.e. the valuation of the organization,

the resulting amount should cover the costs and financial damages that may be caused by this cyber threat.

The damage that can be caused by this cyber threat should be 40 % of the total amount that can be awarded to the organization and its information. In this case, this amount is 189 148 493,- Euro (

Table 10).

6. Discussion

The proposed mathematical formula for predicting the evolution of cyber threats and their potential financial impacts is founded on the fundamental relationship between threat and risk. This correlation, however, has been enhanced by incorporating the time dimension through the use of time series analysis. The development of cyber threats is highly dynamic, characterized by variability over time and changes in their nature. Many cyber threats, such as ransomware or phishing, encompass various subspecies of these attacks, which can complicate their prediction. The proposed method, designed to assess the possible financial impacts of specific cyber threats, is based on a review of existing literature on the topic (Palson et al., 2020; Eling, 2020; European Union, 2022). To effectively apply this method, it was essential to identify the elements within the organization that are most vulnerable to the effects of cyber threats.

These areas were identified based on research conducted in selected organizations during the dissertation work of one of the authors of this paper. It is important to recognize that cyber threats and their characteristics are likely to undergo significant changes in the future (Subroto and Apriyana, 2019). Consequently, the approaches and methods for predicting the potential development and financial impacts of cyber threats must also evolve. With the emergence and advancement of artificial intelligence, tools grounded in this technology should be integrated into the prediction process. While artificial intelligence presents certain risks, its potential applications in the field of cybersecurity can be substantial (Gulati et al., 2023). Our method aims to reflect this reality, and we envision that further development will occur in the digital realm through the creation of a software tool. The results achieved through the application of our method were consulted and assessed by the ICT department of the university. The ICT department's statement and overall assessment of the achieved results are provided in the appendix of this paper.

6.1. Contribution of the Paper

A possible contribution of this paper can be considered the design of a method for determining the impacts of cyber threats on the information environment of an organization. This method includes taking into account economic, security, IT and financial factors that can have a significant impacts on the functioning of the organization. If these areas are disrupted by the course of a cyber threat, the financial impacts in these areas of the information environment can be very serious. Many approaches in this area have their methodological procedures based on questionnaire surveys (Woods and Simpson, 2017). Some other organizations, especially insurance companies, apply methods of continuous mathematics and statistics (Awiszus et al., 2023). These approaches can certainly be useful, however, they do not take into account the impacts of other areas. It is precisely taking into account other areas that can be a certain extension of existing methods and thus provide a certain extension. Incorporating these areas into the method for determining the financial impacts of cyber threats can therefore provide more accurate results. The proposed method can be used primarily for financial institutions such as insurance companies and banks. It can also be used in the field of cybersecurity to identify potential cyber threats and their financial impacts on an organization's information environment. The results of this analysis can also be useful for organizations and can lead to improvements in their current level of security.

6.2. Implication for Practice

As part of the proposal for a method for assessing the financial impacts of cyber threats on an organization's information environment, the areas that may be most affected by these impacts were determined. These areas represent significant assets of the organization in its information environment that are important for its functioning. Any threat to the functionality of any of these areas can cause significant security problems in the organization. If our method were applied in practice, it could bring significant benefits to the field. This is primarily about realizing the significance of the identified areas and their need for protection. Some of these areas, such as the organization's reputation or the costs of data reconstruction and recovery, are still not sufficiently addressed in our view.

Many organizations still do not realize the significance of reputation in connection with cyber threats and their possible impacts. Data reconstruction and recovery is a topic that is the subject of many studies, however, the financial expression of information and data in an organization is still not fully determined. The application of our method could therefore contribute to greater interest in the financial expression of these areas and also to greater attention that could be paid to them. Another possible benefit for practice is the relatively large applicability of the proposed method across various types of organizations. Given that we tried to implement all significant areas that can be affected by the impacts of cyber threats into the assessment process, its use can be very broad. This method can be applied in private companies with various types of business, but also in public institutions such as offices or schools. The variability of the information environment is quite large, however, the application of this method allows achieving results in almost any information environment.

The application of the proposed method can also be found on the part of organizations themselves that are considering such a type of assessment. A specific organization can therefore conduct an analysis of its own information environment and assess which cyber threats and with what risk it can be affected. The output of this process is then the determination of possible financial damages, which can be a criterion for negotiating, for example, insurance policies or other security measures. The results obtained may also bring a new perspective on the security situation in the organization, which may lead to the implementation and improvement of security mechanisms.

6.3. Implications for Research

The research results can be beneficial for the scientific community, primarily from the perspective of quantifying defined endangered elements and determining possible financial impacts on the organization and its information system. Since this is a transdisciplinary area of interest, the achieved results can find their application primarily in areas such as economics, information and communication technologies or security. The proposed method can bring a new perspective to the field of cybersecurity, primarily for describing and examining the possible impacts of cyber threats on the organization and its information environment. This new perspective can find its application in the scientific community primarily due to capturing the mutual relationships between endangered elements and cyber threats and thus more precisely determining potential financial impacts in the organization. The main result of the proposed method is the determination of significant areas of the information environment, the threat or significant disruption of which by means of a cyber threat can cause significant financial impacts to the organization. These areas are characterized by means of defined endangered elements and their valuation. These elements have a tangible and intangible nature, and therefore their mathematical expression, which is determined within the proposed method, can be very beneficial for the scientific community. The results can also be beneficial for the development of the scientific disciplines of cybersecurity and insurance, especially from the perspective of determining potential financial damage in defined areas of the information environment, which cannot be fully expressed through actuarial methods.

The method for determining the financial impacts of selected cyber threats on an organization and its information environment was designed based on an analysis of existing book and publication outputs. As part of the research, consultations were also conducted with selected institutions whose focus is closely related to the issue being addressed. These include, for example, universities, insurance companies, small and medium-sized organizations or closed working groups. Based on the facts found, a method was designed, the aim of which is to integrate and unify the procedure for determining financial impacts on organizations. This is with regard to the transdisciplinary dimension of the issue and the vastness of the information environment.

6.4. Limitations of the Research

Since the method includes calculations of the financial expression of the possible impacts of cyber threats on the information environment, its application is not suitable for every type of organization. These are primarily organizations that can be considered risky (e.g. for security reasons). For this reason, it may not be suitable for the application of high accuracy. This may be, for example, flight operations. In this case, it is a very risky environment, because identifying potential financial impacts on this type of organization may not be a great advantage. This is mainly due to the large number of security measures and elements used in flight operations. A certain risk may also be posed by a large amount of information and data that must meet a high level of security. Based on these facts, the evaluation of some information and data sources can be quite challenging, which may contribute to the inaccuracy of the results achieved. Another factor that may influence the application of our method is the dynamics of the development of cyber threats. Given that cyber threats develop relatively quickly over time, the application of the proposed method may not always correspond to reality. In practice, such a situation may be manifested in the fact that a financial statement of the potential impacts of cyber threats on a specific organization may be made. However, the security situation in the given sector in which the organization operates may change relatively quickly. This fact may no longer be reflected in any way in the financial statement of the possible impacts of cyber threats. This also creates the probability that in the event of a cyber threat being realized, the measures implemented against these threats will not be sufficient and the financial impacts will be much more extensive.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented the findings of our research, which aimed to develop a method for predicting the financial impacts of cyber threats on an organization’s information environment. Our investigation revealed that this is a highly complex issue that requires the integration of various professional fields, including digital technologies, economics, cybersecurity, and law. We believe that a correlation exists across all these areas regarding the prediction of the development and potential financial consequences of cyber threats.

Predicting the impact of cyber threats is a focus of scientific inquiry for many research organizations worldwide (Bradford, 2015; Biener et al., 2015). The rapid and dynamic evolution of cyber attacks, along with the need for timely responses and preparedness, are critical factors driving further research in this field. However, the digital nature of this environment, where physical laws do not apply, complicates the task of prediction. In our research, we aimed for a comprehensive approach to address this challenge. We believe that our proposed method for predicting the impacts and evolution of cyber threats is grounded in fundamental risk management principles, while also incorporating financial assessments of specific areas within the information environment and considering the time dimension. These combined factors are intended to enhance the accuracy of predicting potential cyber attacks and their financial repercussions for organizations.

The proposed method is particularly relevant for the insurance industry. While actuarial mathematics can be valuable for calculating risk, it has proven less effective in the realm of cyber security for predicting potential financial impacts (The Lawyer, 2010; Zahn and Toregas, 2014). The nature of cyber threats significantly differs from other types of insurance claims, rendering traditional actuarial practices less applicable in this context. This observation is supported by the current scientific community engaged in this area of study. Based on our findings, we believe that insuring organizations against cyber threats can be an effective strategy for mitigating their impact on organizational operations. We have recommendations for implementing our method, which is particularly suited for small and medium-sized organizations. In these environments, it is possible to identify key processes that are critical for assessing the financial impacts of cyber threats. However, applying our method to larger organizations that handle extensive data and complex processes may pose challenges. Accurately determining potential financial impacts requires a substantial amount of financial data, which can be difficult to identify in large companies. Consequently, our method may not be suitable for organizations with numerous processes and systems.

Determining the estimated financial impacts of cyber threats in relation to establishing the optimal level of insurance coverage remains a significant challenge (Woods and Simpson, 2017; Zhaoxin et al., 2022). This is where our proposed method could be effectively applied within the insurance sector. One of the key advantages of this method is its ability to identify endangered elements within an organization—areas that are most susceptible to the effects of cyber threats. By pricing these elements and modeling the potential impacts of such threats, our approach can aid in determining the most appropriate amount of insurance coverage needed.

Acknowledgements

This work is a part of the project RVO/FLKŘ/2024/04.

References

- Zeller, G.; Scherer, M. A Comprehensive Model for Cyber Risk Based on Marked Point Processes and Its Application to Insurance. Eur. Actuar. J. 2021, 12, 33–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, C.A.; et al. Cyber-Risk Management: Technical and Insurance Controls for Enterprise – Level Security. In Information Security. In Information Security Management Handbook; Auerbach Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Majuca, R.P.; et al. The Evolution of Cyberinsurance. Preprint 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, J. Insight Cyber Insurance Market Update. Advisen 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Biener, C.; Eling, M.; Wirfs, J.H. Insurability of Cyber Risk: An Empirical Analysis. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2015, 40, 131–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanosky, S. Examining the Costs and Causes of Cyber Incidents. J. Cybersecurity 2016, 2, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.; Simpson, A. Policy Measures and Cyber Insurance: A Framework. J. Cyber Policy 2017, 2, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacorogna, M.; Kratz, M. Managing Cyber Risk, a Science in the Making. ESSEC Bus. Sch. Res. Pap. 2302. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, U. The Cyber Insurance Market in Sweden. Comput. Secur. 2017, 68, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Mathew, R. Ransomware: Average Ransom Payout Increases to $41,000. Data Breach Today 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoxin, L.; et al. Pricing Cyber Security Insurance. J. Math. Financ. 2022, 12, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, A.; Martinelli, F.; Nanni, S.; Orlando, A.; Yautsiukhin, A. Cyber-Insurance Survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2017, 24, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Lopez, J.; Rice, M.; McElroy, S.; Dandurand, L.; Serrano, O. A Framework for Incorporating Insurance in Critical Infrastructure Cyber Risk Strategies. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2016, 14, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunggal, A. 22 Types of Malware and How to Recognize Them in 2023. UpGuard 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Millaire, P.; et al. Latest Industry Trends in Cyber Security and Cyber Insurance. Report 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Palson, K.; et al. Analysis of the Impact of Cyber Events for Cyber Insurance. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2020, 45, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erola, A.; et al. A System to Calculate Cyber Value-at-Risk. Report 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlík, L. Modeling the Impact of Cyber Threats on an Organization's Information System in the Framework of Cyber-Risk Insurance. Int. J. Math. Model. Methods Appl. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ponemon Institute. 2017 Cost of Data Breach Study – Global Overview; Ponemon Institute: Traverse City, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eling, M. Cyber Risk Research in Business and Actuarial Science. Eur. Actuar. J. 2020, 10, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. EU Cyber-Resilience Act. Preprint.

- Subroto, A.; Apriyana, A. Cyber Risk Prediction Through Social Media Big Data Analytics and Statistical Machine Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, P.; et al. Artificial Intelligence In Cyber Security: Rescue Or Challenge. Rev. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lawyer. Incentives and Barriers of the Cyber Insurance Market in Europe. Report 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn, N.; Toregas, C. Insurance for Cyber Attacks: The Issue of Setting Premiums in Context. Report 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D.; Simpson, A. Policy Measures and Cyber Insurance: A Framework. J. Cyber Policy 2017, 2, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awiszus, K.; et al. Modeling and Pricing Cyber Insurance: Idiosyncratic, Systematic, and Systemic Risk. Eur. Actuar. J. 2023, 13, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Introduction to Time Series Analysis and Forecasting; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, C.; et al. Survey of Accounting; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, S.; Buxmann, P. Pricing Strategies of Software Vendors. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2009, 1, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Scotland. The Impacts of a Cyber Attack – What Cyber Means for Your Environmental, Social & Governance Strategy. Report.

- Tao, F.; et al. The Future of Artificial Intelligence in Cybersecurity: A Comprehensive Survey. EAI Endorsed Trans. Creat. Technol. 2021, 8, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, F.; Sheehan, B.; Fortmann, M.; Kia, A.N.; Mullins, M.; Murphy, F.; Materne, S. Cyber Risk and Cybersecurity: A Systematic Review of Data Availability. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2022, 47, 698–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredt, S. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Financial Sector—Potential and Public Strategies. Front. Artif. Intell. 2019, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, M.; Stephenson, A.; Toscas, P.; Zhu, Z.A. A Multivariate Model to Quantify and Mitigate Cybersecurity Risk. Risks 2020, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, M.; Schnell, W. What Do We Know about Cyber Risk and Cyber Risk Insurance? J. Risk Financ. 2016, 17, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldasoro, I.; Gambacorta, L.; Giudici, P.; Leach, T. Operational and Cyber Risks in the Financial Sector. BIS Work. Pap. 2020, No. 840, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, A. Cyber Risk Quantification: Investigating the Role of Cyber Value at Risk. Risks 2021, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, H.; Mishra, B.; Raghunathan, S. The Effect of Internet Security Breach Announcements on Market Value: Capital Market Reactions for Breached Firms and Internet Security Developers. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 9, 70–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, D.; Nogueira-Leite, D.; Almeida, R.; Cruz-Correia, R. Economic Impact of a Hospital Cyberattack in a National Health System: Descriptive Case Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e41738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assen von der, J.; Franco, M.F.; Dong, M.; Stiller, B. QuantTM: Business-Centric Threat Quantification for Risk Management and Cyber Resilience. Report 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eling, M.; Elvedi, M.; Falco, G. The Economic Impact of Extreme Cyber Risk Scenarios. N. Am. Actuar. J. 2023, 27, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.F.; Künzler, F.; Von Der Assen, J.; Feng, C.; Stiller, B. RCVaR: An Economic Approach to Estimate Cyberattacks Costs Using Data from Industry Reports. Comput. Secur. 2024, 139, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Assalemi, G.; Al-Khateeb, H.; Epiphaniou, G.; Aggoun, A. Super Learner Ensemble for Anomaly Detection and Cyber-Risk Quantification in Industrial Control Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 13279–13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Razzaque, A.; Yousaf, M.; Ali, S.S. A Novel AI-Based Integrated Cybersecurity Risk Assessment Framework and Resilience of National Critical Infrastructure. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 12427–12446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhao, S.; Lu, X. A Novel Fault Diagnosis Method Based on CNN and LSTM and Its Application in Fault Diagnosis for Complex Systems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 1289–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, M.; Wirfs, J. What Are the Actual Costs of Cyber Risk Events? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 272, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).