1. Summary

Candida tropicalis is an opportunistic fungal pathogen of great clinical relevance [

1,

2,

3], it is considered the second most virulent Candida species after

Candida albicans; the growing resistance to antifungals, especially to azoles, amphotericin B and echinocandins is of great concern. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies

C. tropicalis as a high-risk pathogen, considering it a threat to public health and highlighting the urgent need for research and surveillance [

4,

5,

6]. Thus, the search for novel, effective and safe compounds with antifungal potential against these pathogens, using precise, and reproducible methodologies, is urgent. In this context, plant-based compounds represent an excellent alternative to investigate. To better understand transcriptional mechanisms underlying this adaptive response, RNA-Seq was performed on

C. tropicalis cultures treated with the natural antifungal monoterpene, isoespintanol (ISO) and untreated controls (INO) [

7]. The resulting dataset captures the genome wide transcriptional landscape associated with antifungal exposure and provides a foundation for comparative analyses across Candida species. This work complements existing resources for

Candida albicans and

Candida glabrata by extending transcriptomic knowledge to a less characterized yet clinically relevant species.

2. Data Description

2.1. Background and Summary

Candida tropicalis is a clinically relevant opportunistic yeast widely isolated from bloodstream, urogenital, and invasive infections, where it is particularly associated with high mortality in immunocompromised and critically ill patients [

8,

9]. Unlike other non-

albicans Candida species,

C. tropicalis exhibits increased adherence, biofilm formation, and metabolic plasticity, especially in environments enriched in hydrocarbons and lipids, which makes it both a pathogen and a biotechnologically useful organism. The growing emergence of antifungal resistance, especially to azoles and echinocandins has positioned this species as a priority pathogen for the discovery of alternative therapeutic molecules [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Isoespintanol (2-isopropyl-3,6-dimethoxy-5-methylphenol) is a natural monoterpene phenol isolated from

Oxandra cf. xylopioides, a plant species from the Annonaceae family. It has been reported to exhibit antioxidant, membrane disruptive, and broad-spectrum antifungal properties, including activity against

Candida spp., [

14,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the molecular pathways and stress response mechanisms triggered by ISO in fungal cells remain largely unexplored. Understanding these cellular responses is essential to decipher whether ISO acts by inducing oxidative imbalance, affecting membrane integrity, impairing metabolic pathways, or triggering programmed cell death.

To contribute to address this gap, we generated a comprehensive transcriptomic dataset based on high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

C. tropicalis cultures were exposed to ISO at their minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC

90 = 391.6 µg/mL) for four hours (Stage B), while control cells were grown under identical conditions without treatment (Stage A). For control condition, five independent biological replicates were included and one for treatment totaling six RNA-seq libraries,

Table 1.

Although the experimental design initially considered three biological replicates per group (six RNA-seq libraries in total), the treated yeast cells exhibited remarkably rapid loss of viability due to the fungicidal activity of ISO, resulting in severe cellular stress, and RNA degradation. This led to the successful recovery of only one high quality RNA sample from the treatment condition, in contrast to the five control samples that met RNA integrity and yield requirements (RIN ≥ 5.3; total RNA ≈ 0.5–1.5 µg),

Table 2.

Rather than being a limitation, we considered that this biological constraint underscores the relevance of the dataset, as it captures a rare transcriptional state associated with early lethality and cell collapse under monoterpene induced stress. The dataset therefore provides a valuable resource for investigating rapid antifungal responses, oxidative damage, and cell death pathways in C. tropicalis, and supports future comparative analyses of antifungal mechanisms and resistance evolution.

Total RNA was extracted, verified for purity and integrity sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (150 bp paired end), and aligned against the

C. tropicalis reference genome (Ensembl release GCA000006335v3). Gene expression was quantified and normalized using the TMM method implemented in EdgeR [

17]. Differential expression analysis revealed 186 genes significantly altered between conditions (|log₂FC| > 1, FDR < 0.05), including 159 upregulated and 27 downregulated transcripts,

Figure 1.

Functional annotation indicates activation of oxidative stress defense mechanisms, efflux transporters, mitochondrial responses, and lipid/membrane remodeling pathways consistent with a cellular adaptation to oxidative and membrane targeting stress induced by ISO,

Figure 2.

2.2. Technical validation

To guarantee the reliability and reproducibility of this dataset, multiple layers of technical validation were applied across RNA extraction, sequencing, and bioinformatic processing. Total RNA from each biological replicate was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), quantified via Ribogreen fluorometry, and assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Samples yielded RIN above 5.0 [

20], and comparable yields between control (0.785 ± 0.02 µg) and ISO-treated samples (0.797 ± 0.03 µg), demonstrating no bias during extraction. RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA protocol and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 platform, producing over 20 million paired-end reads (150 bp) per sample. FASTQC and MultiQC reports [

21,

22] showed Phred quality scores > Q30 for > 95% of bases, negligible adapter contamination, and stable GC content, confirming high sequencing performance,

Table 3.

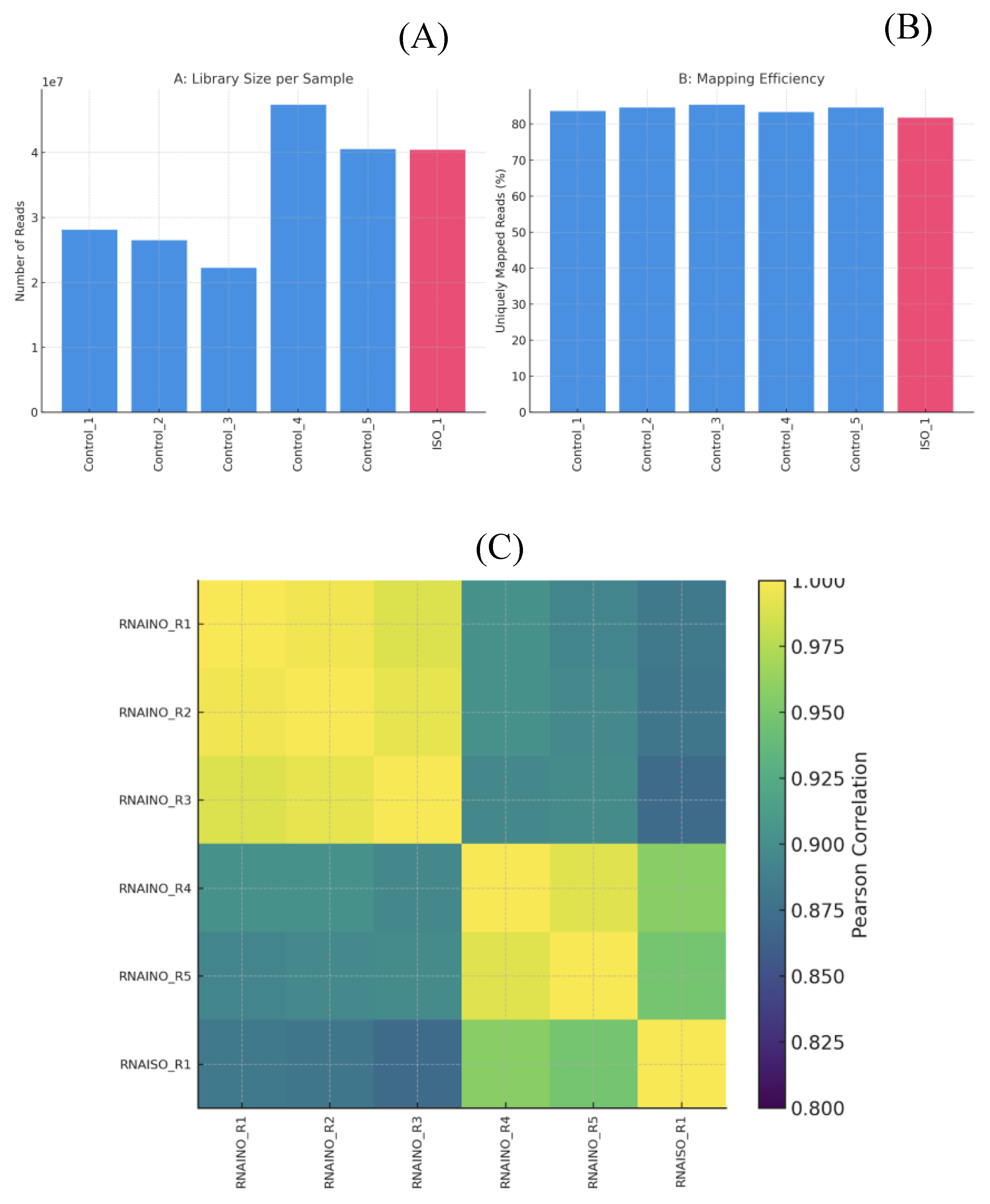

Sequencing libraries generated between 22 and 47 million paired end reads per sample (

Figure 3A), ensuring sufficient depth for transcriptome profiling. Reads were aligned to the

C. tropicalis reference genome (Ensembl GCA000006335v3) using Bowtie2 [

23], achieving mapping rates RNA-seq reads were aligned to the

C. tropicalis reference genome (REF GCA_000006335.3).

The distribution of reads mapped to annotated genes, together with the low proportion of rRNA derived sequences, confirmed that the RNA-seq libraries were highly enriched for mRNA and that library preparation was technically consistent (

Figures 3A-B). Mapping efficiency ranged from 81.78% to 85.41% uniquely mapped reads, indicating high quality libraries and minimal contamination or ribosomal RNA interference. The average mapped read length remained consistent across samples (~280–294 bp), confirming the integrity of sequencing and alignment processes (

Table 4),

Figure 3B. The sample to-sample Pearson correlation heatmap (

Figure 3C) shows strong clustering of biological replicates within each condition, indicating high reproducibility of the RNA-seq data. Control and ISO-treated sample form two well defined groups, with intra group correlation values above 0.93. In contrast, inter group correlations are lower, reflecting clear transcriptional differences driven by ISO exposure rather than technical variability.

Differential expression analysis was performed using EdgeR with TMM normalization [

17]. Dispersion trends (common, trended, and tagwise) fell within previously reported ranges for yeast transcriptomes [

24], confirming the suitability of our statistical model (Figure 4

A). MA plots further demonstrated the symmetry of expression changes and highlighted significantly altered genes (FDR < 0.05) (Figure 4

B). P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method [

25] to ensure statistical robustness. Biologically, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) aligned with known antifungal response mechanisms. Up-regulated genes were enriched in pathways associated with oxidative stress mitigation, efflux transporter activation, and cell membrane adaptation, consistent with stress responses previously reported in

Candida spp. under antifungal pressure [

26,

27]

. Heatmap visualization of the top 50 DEGs confirmed a distinct transcriptional reprogramming pattern between treated and untreated groups (Figure 4

C).

Figure 5.

Differential expression validation and visualization of top DEGs. (A) Biological coefficient of variation (BCV) plot showing dispersion estimates across genes using tagwise, common, and trend estimates, confirming appropriate modeling of biological variability in C. tropicalis. (B) MA plot representing log2 fold changes versus average logCPM; red dots indicate significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05). (C) Heatmap of the top 50 DEGs ranked by FDR, standardized by row z-scores of log2(CPM+1). A clear separation is observed between control (RNAINO) and ISO–treated (RNAISO) samples, demonstrating consistent transcriptional reprogramming in response to treatment.

Figure 5.

Differential expression validation and visualization of top DEGs. (A) Biological coefficient of variation (BCV) plot showing dispersion estimates across genes using tagwise, common, and trend estimates, confirming appropriate modeling of biological variability in C. tropicalis. (B) MA plot representing log2 fold changes versus average logCPM; red dots indicate significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05). (C) Heatmap of the top 50 DEGs ranked by FDR, standardized by row z-scores of log2(CPM+1). A clear separation is observed between control (RNAINO) and ISO–treated (RNAISO) samples, demonstrating consistent transcriptional reprogramming in response to treatment.

Collectively, these results confirm that the dataset is technically sound, biologically consistent, and suitable for downstream applications such as antifungal mode of action studies, gene regulatory network modeling, or comparative fungal transcriptomics.

3. Methods

3.1. Fungal Strain, Growth Conditions, and Treatment

Candida tropicalis was cultured in Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (SDB) at 30 °C with shaking at 150 rpm until reaching mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 ≈ 0.8). ISO (2-isopropyl-3,6-dimethoxy-5-methylphenol), previously isolated and characterized from

Oxandra cf. xylopioides [

16], was dissolved in DMSO and applied at a final concentration corresponding to its minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC

90 = 391.6 µg/mL). Cultures were incubated for 4 h under treatment (Stage B), while control cells received an equivalent volume of DMSO (Stage A). Three independent biological replicates were generated per condition.

3.2. RNA Extraction and Quality Assessment

Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg of fungal biomass using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The aqueous phase was recovered after chloroform separation, precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 75% ethanol, and resuspended in RNase-free water. RNA concentration was measured using the Quant-iT™ RiboGreen Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA integrity was assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Nano Kit; only samples with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7.0 were used for library preparation. Yield was consistent between conditions (0.785 ± 0.02 µg Control vs. 0.797 ± 0.03 µg ISO-treated).

3.3. Library Preparation and RNA Sequencing

RNA-seq libraries were generated using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit following poly-A selection. Library quality and insert size were validated using the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Libraries were pooled equimolarly and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, producing paired-end reads of 150 bp. Each sample yielded > 20 million read pairs. Raw BCL files were converted to FASTQ using Illumina bcl2fastq.

3.4. Preprocessing and Alignment

Sequence quality was evaluated using FastQC [

22], and summary metrics were compiled using MultiQC [

21]. Adapter trimming and low-quality base removal were performed using Trimmomatic. High-quality reads were aligned to the

C. tropicalis reference genome (Ensembl release GCA000006335v3) using Bowtie2 [

23] with default sensitive parameters. Mapping statistics (alignment rate, uniquely mapped reads, rRNA contamination) were extracted using SAMtools and summarized per sample.

3.5. Quantification and Differential Expression Analysis

Aligned reads were quantified at the gene level using HTSeq-count in “union” mode. Gene expression values were normalized using the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method implemented in the EdgeR package. Genes with low counts (< 1 count per million in ≥ 3 samples) were excluded. Differential expression between Stage A (control) and Stage B (ISO-treated) was assessed using EdgeR’s quasi-likelihood F-test. Genes with |log2 fold change| > 1 and FDR < 0.05 [

25] were considered significantly differentially expressed. Functional enrichment was conducted using ShinyGO

https://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/ analysis.

3.6. Data Availability and Reproducibility

All raw FASTQ files, normalized count matrices, sample metadata, and scripts used for analysis are available in the GitHub repository:

4.User Notes

This dataset is suitable for a wide range of downstream analyses in fungal biology, transcriptomics, and antifungal research. Beyond the differential expression analysis described here, users may employ the raw and processed data for Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment to identify biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components affected by ISO exposure. The dataset is also well-suited for reconstructing co-expression networks, inferring regulatory modules, and identifying transcription factors or non-coding RNAs involved in antifungal stress responses.

Furthermore, because the dataset includes raw counts, metadata, and reproducible analysis scripts, it can be used to benchmark normalization strategies (e.g., TMM, TPM, DESeq2), evaluate statistical models for differential expression, or train machine learning models to predict drug susceptibility or resistance in Candida spp. Comparative transcriptomic studies across Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. auris, and C. tropicalis may also benefit from this resource. All files are openly accessible through the linked repository and permanently archived in Mendeley Data. Users are encouraged to cite this dataset when incorporating it into secondary analyses, meta-analyses, or computational modeling. Any modifications or re-use of the data should comply with the CC-BY 4.0 license.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.P., O.I.C.-M. and A.A.-O.; Methodology, K.A.P., O.I.C.-M. and A.A.-O.; Data curation, K.A.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, K.A.P., O.I.C.-M. and A.A.-O.; Writing—review and editing, K.A.P., O.I.C.-M. and A.A.-O.

Funding

KAP acknowledges SECIHTI for a fellowship CVU (227919).

Data Availability Statement

All datasets supporting the findings of this study are available as Supplementary Files accompanying this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Office of the Vice Rector for Research and Outreach at the University of Córdoba for covering the publication costs and the National Center for Genomic Sequencing (Medellín, Colombia) for technical assistance and sequencing services. Thanks to Neifer Martínez and Vanessa Vega for their assistance in preparing the graphical abstract.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Spruijtenburg, B.; De Carolis, E.; Magri, C.; Meis, J. F.; Sanguinetti, M.; de Groot, T.; Meijer, E. F. J. Genotyping of Candida tropicalis Isolates Uncovers Nosocomial Transmission of Two Lineages in Italian Tertiary Care Hospital. Journal of Hospital Infection 2025, 155, 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Suto, Y.; Horiba, K.; Masuda, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Hashino, M.; Kuroda, M.; Fukuda, H. Candida tropicalis Brain Abscess Diagnosed by Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing: A Case Report. Internal Medicine 2025, 5937–25. [CrossRef]

- Doan, H. T.; Chiu, Y. L.; Cheng, L. C.; Coad, R. A.; Chiang, H. Sen. Candida tropicalis Alters Barrier Permeability and Claudin-1 Organization in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Journal of Physiological Investigation 2025, 68 (1), 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Delma, F. Z.; Spruijtenburg, B.; Meis, J. F.; de Jong, A. W.; Groot, J.; Rhodes, J.; Melchers, W. J. G.; Verweij, P. E.; de Groot, T.; Meijer, E. F. J.; Buil, J. B. Emergence of Flucytosine- Resistant Candida tropicalis Clade, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2025, 31 (7), 1354–1364. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Zhao, R.; Han, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Research Progress on the Drug Resistance Mechanisms of Candida tropicalis and Future Solutions. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2025, 16, 1594226. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K. Y.; Chen, Y. Z.; Zhou, Z. L.; Tsai, J. N.; Tseng, M. N.; Liu, H. L.; Wu, C. J.; Liao, Y. C.; Lin, C. C.; Tsai, D. J.; Chen, F. J.; Hsieh, L. Y.; Huang, K. C.; Huang, C. H.; Chen, K. T.; Chu, W. L.; Lin, C. M.; Shih, S. M.; Hsiung, C. A.; Chen, Y. C.; Sytwu, H. K.; Yang, Y. L.; Lo, H. J. Detection in Orchards of Predominant Azole-Resistant Candida tropicalis Genotype Causing Human Candidemia, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2024, 30 (11), 2323–2332. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Martínez, O. I.; Angulo-Ortíz, A.; Santafé-Patiño, G.; Aviña-Padilla, K.; Velasco-Pareja, M. C.; Yasnot, M. F. Transcriptional Reprogramming of Candida tropicalis in Response to Isoespintanol Treatment. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 1199. [CrossRef]

- Papon, N.; Courdavault, V.; Clastre, M.; Bennett, R. J. Emerging and Emerged Pathogenic Candida Species: Beyond the Candida albicans Paradigm. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9 (9). [CrossRef]

- Zuza-Alves, D. L.; Sila-Rocha, W. P.; Chaves, G. An Update on Candida tropicalis Based on Basic and Clinical Approaches. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Magill, S.-O. E. E. J. Changes in Prevalence of Health Care–Associated Infections. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380 (11), 1085–1086. [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O. A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S. C. A.; Groll, A. H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Revathi, G.; Santolaya, M. E.; White, P. L.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Arendrup, M. C.; Baddley, J.; Barac, A.; Ben-Ami, R.; Brink, A. J.; Grothe, J. H.; Guinea, J.; Hagen, F.; Hochhegger, B.; Hoenigl, M.; Husain, S.; Jabeen, K.; Jensen, H. E.; Kanj, S. S.; Koehler, P.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Lewis, R. E.; Meis, J. F.; Nguyen, M. H.; Pana, Z. D.; Rath, P. M.; Reinhold, I.; Seidel, D.; Takazono, T.; Vinh, D. C.; Zhang, S. X.; Afeltra, J.; Al-Hatmi, A. M. S.; Arastehfar, A.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Bongomin, F.; Carlesse, F.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Chai, L. Y. A.; Chamani-Tabriz, L.; Chiller, T.; Chowdhary, A.; Clancy, C. J.; Colombo, A. L.; Cortegiani, A.; Corzo Leon, D. E.; Drgona, L.; Dudakova, A.; Farooqi, J.; Gago, S.; Ilkit, M.; Jenks, J. D.; Klimko, N.; Krause, R.; Kumar, A.; Lagrou, K.; Lionakis, M. S.; Lmimouni, B. E.; Mansour, M. K.; Meletiadis, J.; Mellinghoff, S. C.; Mer, M.; Mikulska, M.; Montravers, P.; Neoh, C. F.; Ozenci, V.; Pagano, L.; Pappas, P.; Patterson, T. F.; Puerta-Alcalde, P.; Rahimli, L.; Rahn, S.; Roilides, E.; Rotstein, C.; Ruegamer, T.; Sabino, R.; Salmanton-García, J.; Schwartz, I. S.; Segal, E.; Sidharthan, N.; Singhal, T.; Sinko, J.; Soman, R.; Spec, A.; Steinmann, J.; Stemler, J.; Taj-Aldeen, S. J.; Talento, A. F.; Thompson, G. R.; Toebben, C.; Villanueva-Lozano, H.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Weinbergerová, B.; Wiederhold, N.; Willinger, B.; Woo, P. C. Y.; Zhu, L. P. Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candidiasis: An Initiative of the ECMM in Cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Ltd May 1, 2025, pp e280–e293. [CrossRef]

- Fakhri-Demeshghieh, A.; Yousefipour, A.; Bolouki, Y.; Bigdeli, M. S.; Zamani, E.; Farajkhoda, A.; Salmani, A.; Katiraee, F.; Bokaie, S. Antifungal Resistance of Candida Spp. Isolates From HIV/AIDS Patients in Iran 1999–2024: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kadariswantiningsih, I. N.; Empitu, M. A.; Santosa, T. I.; Alimu, Y. Antifungal Resistance: Emerging Mechanisms and Implications (Review). Molecular Medicine Reports. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rojano, B.; Saez, J.; Schinella, G.; Quijano, J.; Vélez, E.; Gil, A.; Notario, R. Experimental and Theoretical Determination of the Antioxidant Properties of Isoespintanol (2-Isopropyl-3,6-Dimethoxy-5-Methylphenol). J Mol Struct 2008, 877, 1–6.

- Contreras, O.; Angulo, A.; Santafé, G. Mechanism of Antifungal Action of Monoterpene Isoespintanol against Clinical Isolates of Candida tropicalis. Molecules 2022, 27, 5808. [CrossRef]

- Contreras Martínez, O. I.; Ortíz, A. A.; Patiño, G. S. Antifungal Potential of Isoespintanol Extracted from Oxandra xylopioides Diels (Annonaceae) against Intrahospital Isolations of Candida SPP. Heliyon 2022, 8 (10). [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. D.; McCarthy, D. J.; Smyth, G. K. EdgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26 (1), 139–140. [CrossRef]

- Aviña Padilla, Katia; Angulo-Ortiz, Alberto; Contreras-Martinez, Orfa Ines. 2025, “RNA-Seq dataset of Candida tropicalis under antifungal stress”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/tr3rnz67jc.1.

- Wilkinson, M. D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, Ij. J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J. W.; da Silva Santos, L. B.; Bourne, P. E.; Bouwman, J.; Brookes, A. J.; Clark, T.; Crosas, M.; Dillo, I.; Dumon, O.; Edmunds, S.; Evelo, C. T.; Finkers, R.; Gonzalez-Beltran, A.; Gray, A. J. G.; Groth, P.; Goble, C.; Grethe, J. S.; Heringa, J.; t Hoen, P. A. C.; Hooft, R.; Kuhn, T.; Kok, R.; Kok, J.; Lusher, S. J.; Martone, M. E.; Mons, A.; Packer, A. L.; Persson, B.; Rocca-Serra, P.; Roos, M.; van Schaik, R.; Sansone, S. A.; Schultes, E.; Sengstag, T.; Slater, T.; Strawn, G.; Swertz, M. A.; Thompson, M.; Van Der Lei, J.; Van Mulligen, E.; Velterop, J.; Waagmeester, A.; Wittenburg, P.; Wolstencroft, K.; Zhao, J.; Mons, B. Comment: The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci Data 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Fleige, S.; Pfaffl, M. W. RNA Integrity and the Effect on the Real-Time QRT-PCR Performance. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2006, 27(2-3), 126–139. [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32 (19), 3047–3048. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Bioinformatics. 2010. URL: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012, 9 (4), 357–359. [CrossRef]

- Gierliński, M.; Cole, C.; Schofield, P.; Schurch, N. J.; Sherstnev, A.; Singh, V.; Wrobel, N.; Gharbi, K.; Simpson, G.; Owen-Hughes, T.; Blaxter, M.; Barton, G. J. Statistical Models for RNA-Seq Data Derived from a Two-Condition 48-Replicate Experiment. Bioinformatics 2015, 31(22), 3625–3630. [CrossRef]

- Benjaminit, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 1995, 57, 289-300. https://academic.oup.com/jrsssb/article/57/1/289/7035855.

- Morschhäuser, J. The Development of Fluconazole Resistance in Candida albicans – an Example of Microevolution of a Fungal Pathogen. Journal of Microbiology. 2016, 54, 192-201. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Santos, G. C. de O.; Vasconcelos, C. C.; Lopes, A. J. O.; Cartágenes, M. do S. de S.; Filho, A. K. D. B.; do Nascimento, F. R. F.; Ramos, R. M.; Pires, E. R. R. B.; de Andrade, M. S.; Rocha, F. M. G.; Monteiro, C. de A. Candida Infections and Therapeutic Strategies: Mechanisms of Action for Traditional and Alternative Agents. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9, 1351. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).