Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

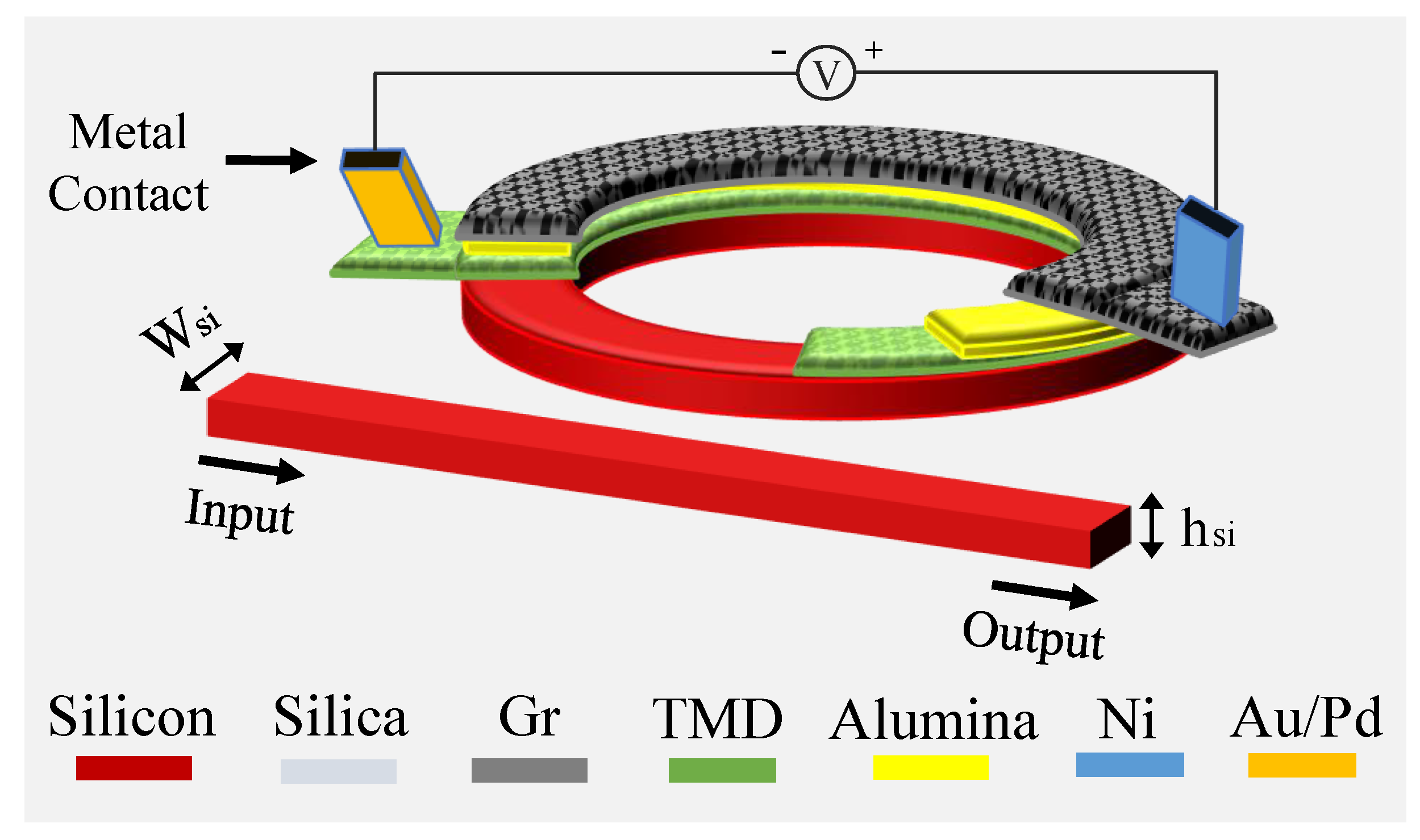

1. Introduction

2. 2D Materials Properties

2.1. Chemical Potential

2.2. Graphene

2.3. TMD

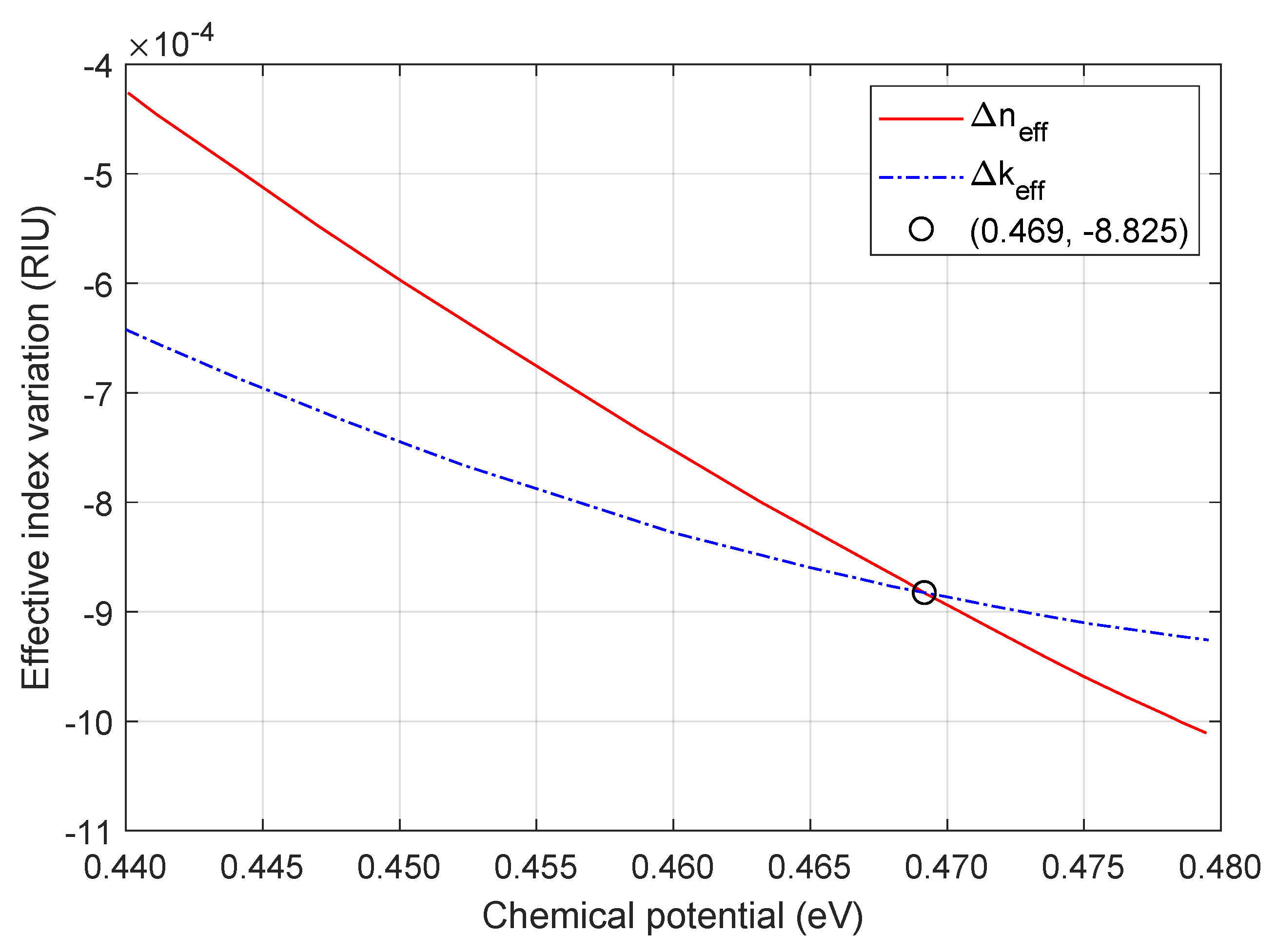

2.4. Effective Index

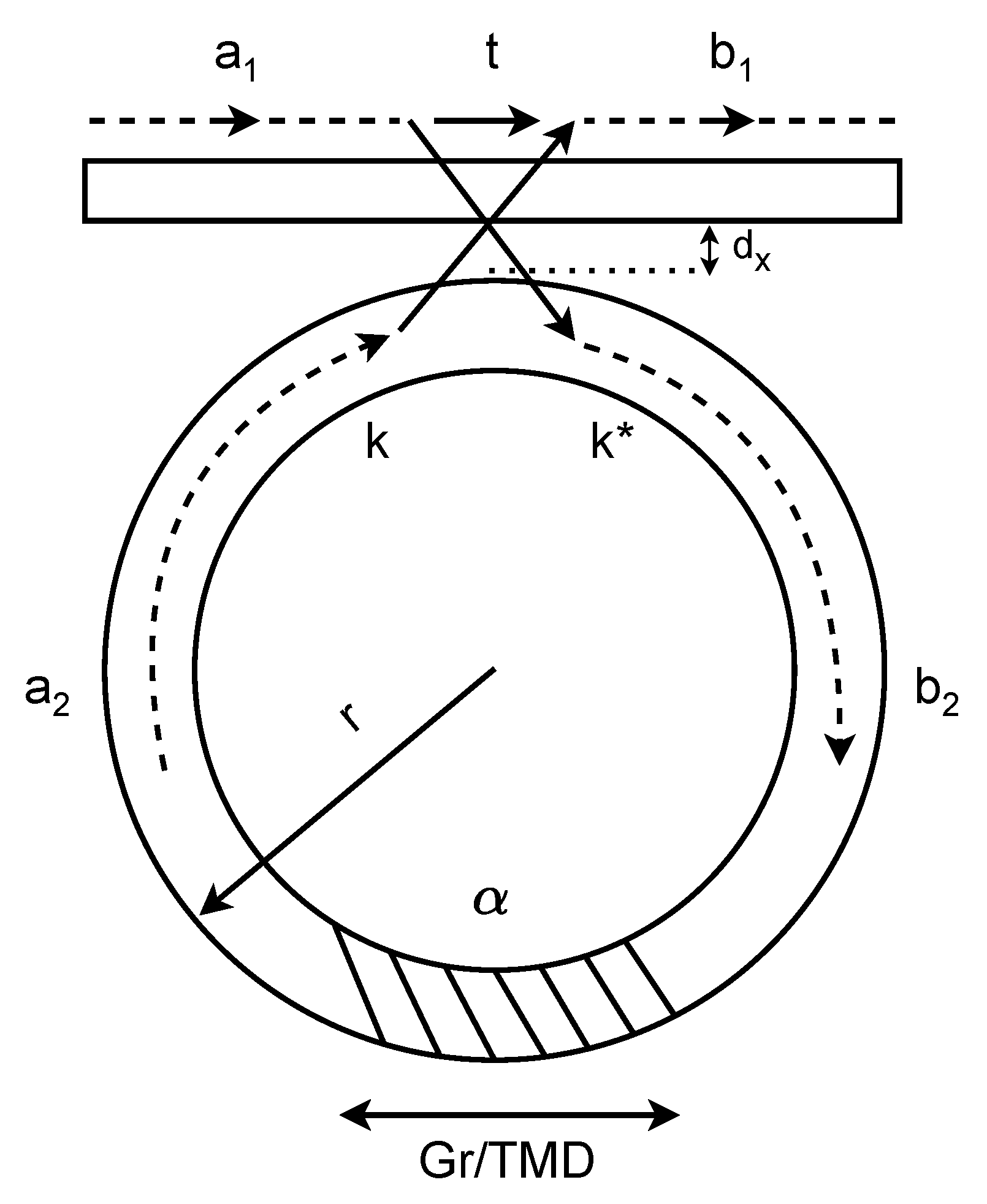

3. Principle of Operation for RRMs

3.1. Critical Coupling

4. Performance Metrics

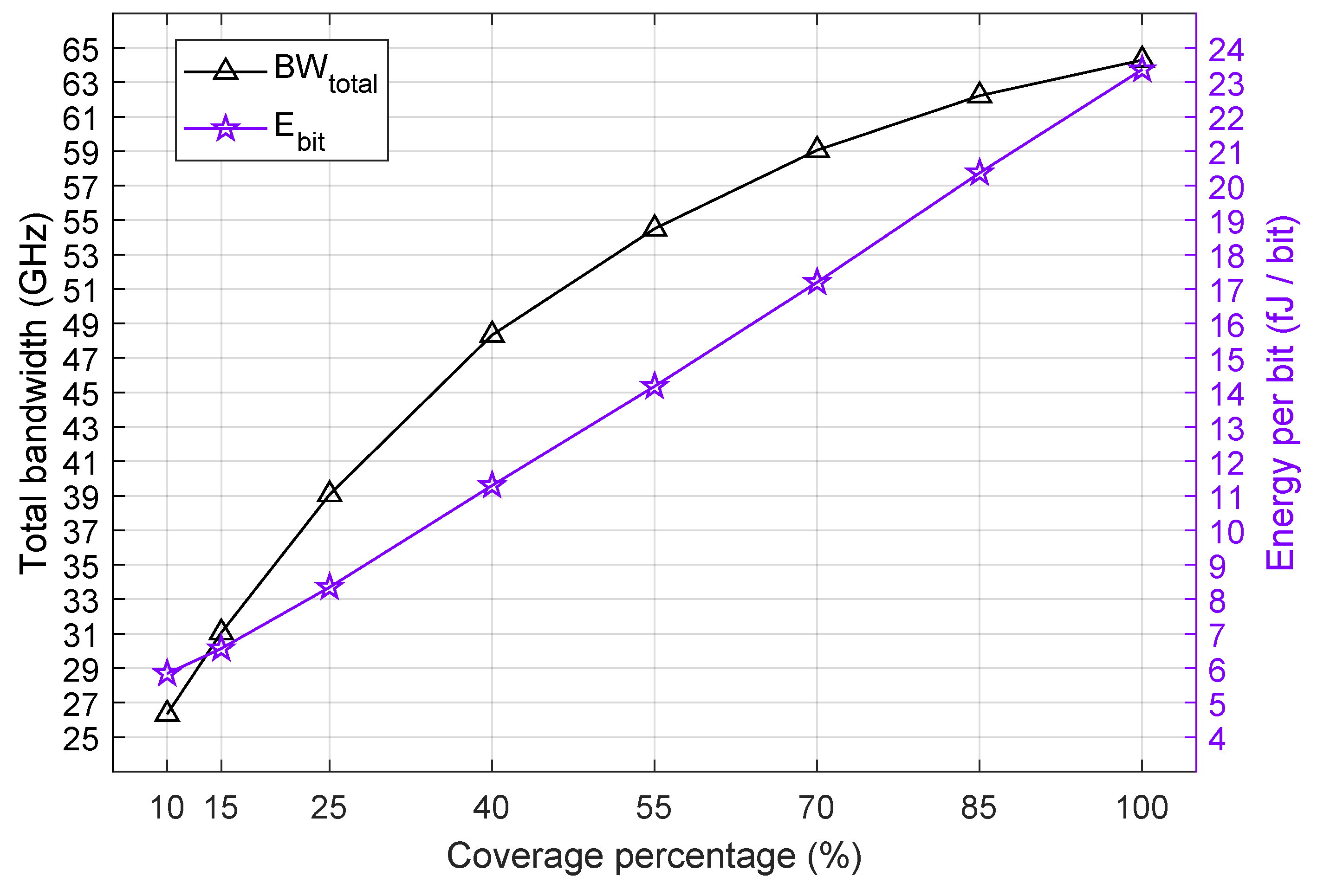

4.1. Bandwidth Analysis

4.2. Energy Consumption Analysis

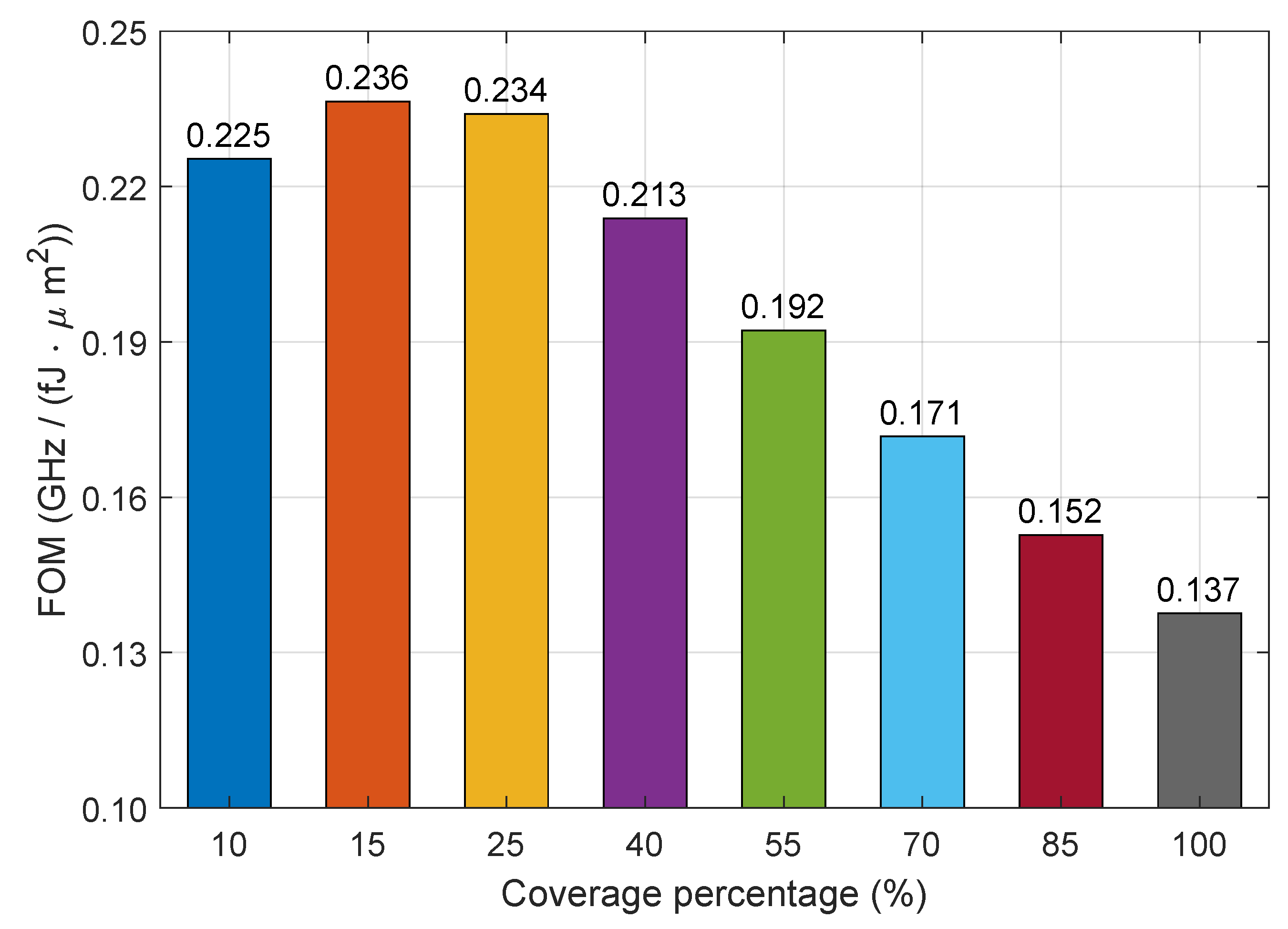

4.3. Figure of Merit

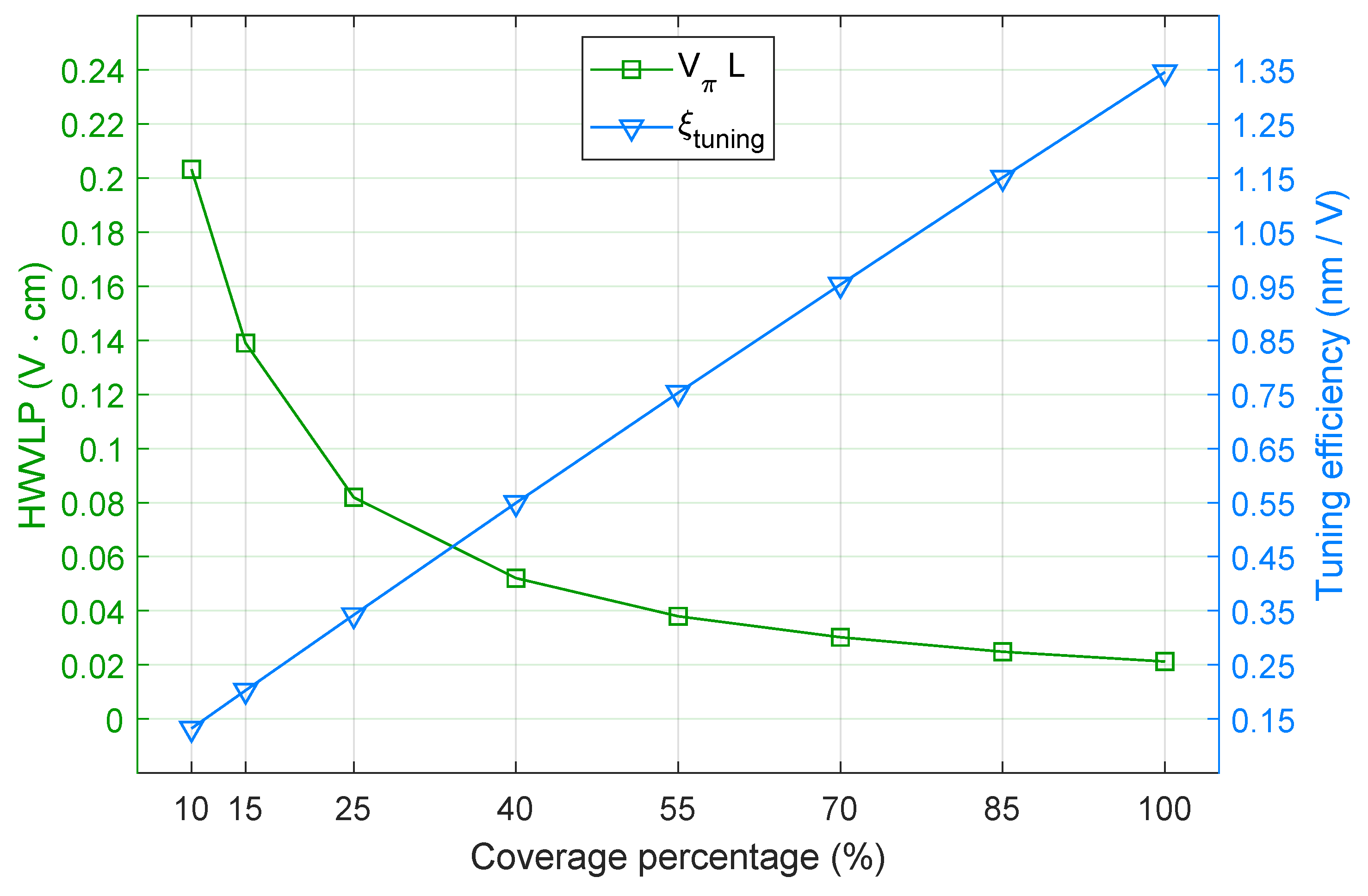

4.4. Modulation Efficiency

5. Simulation Results and Discussions

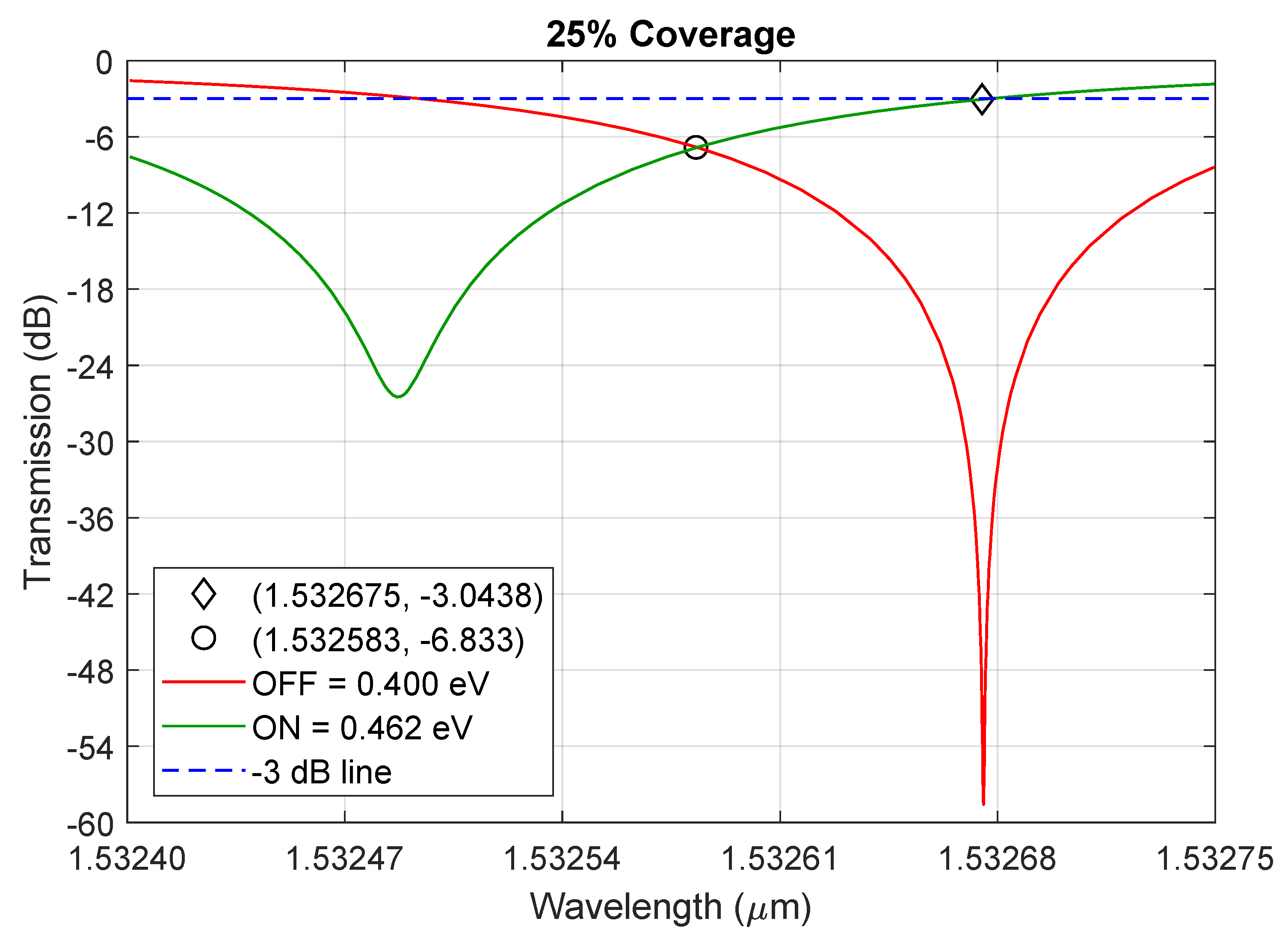

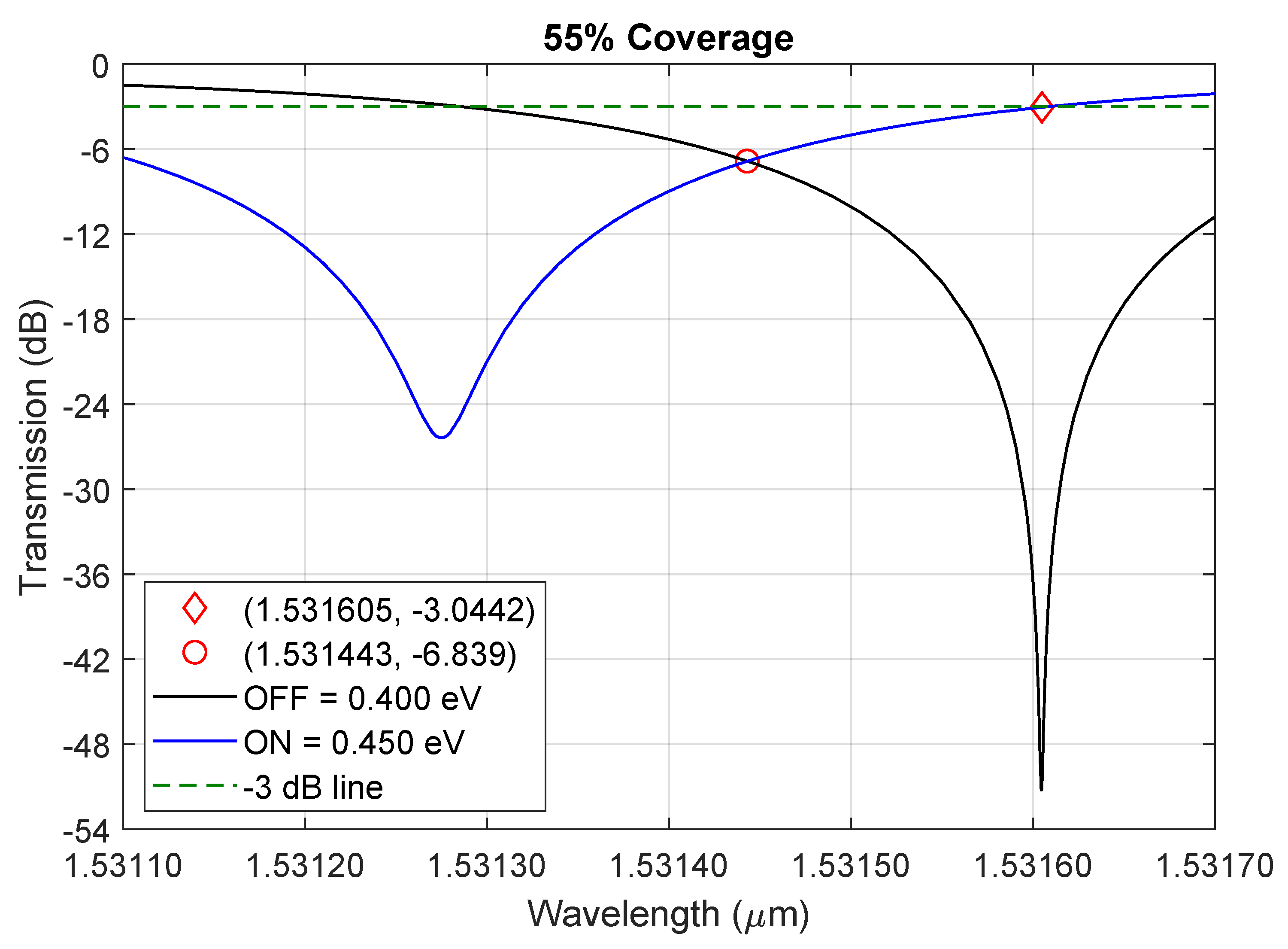

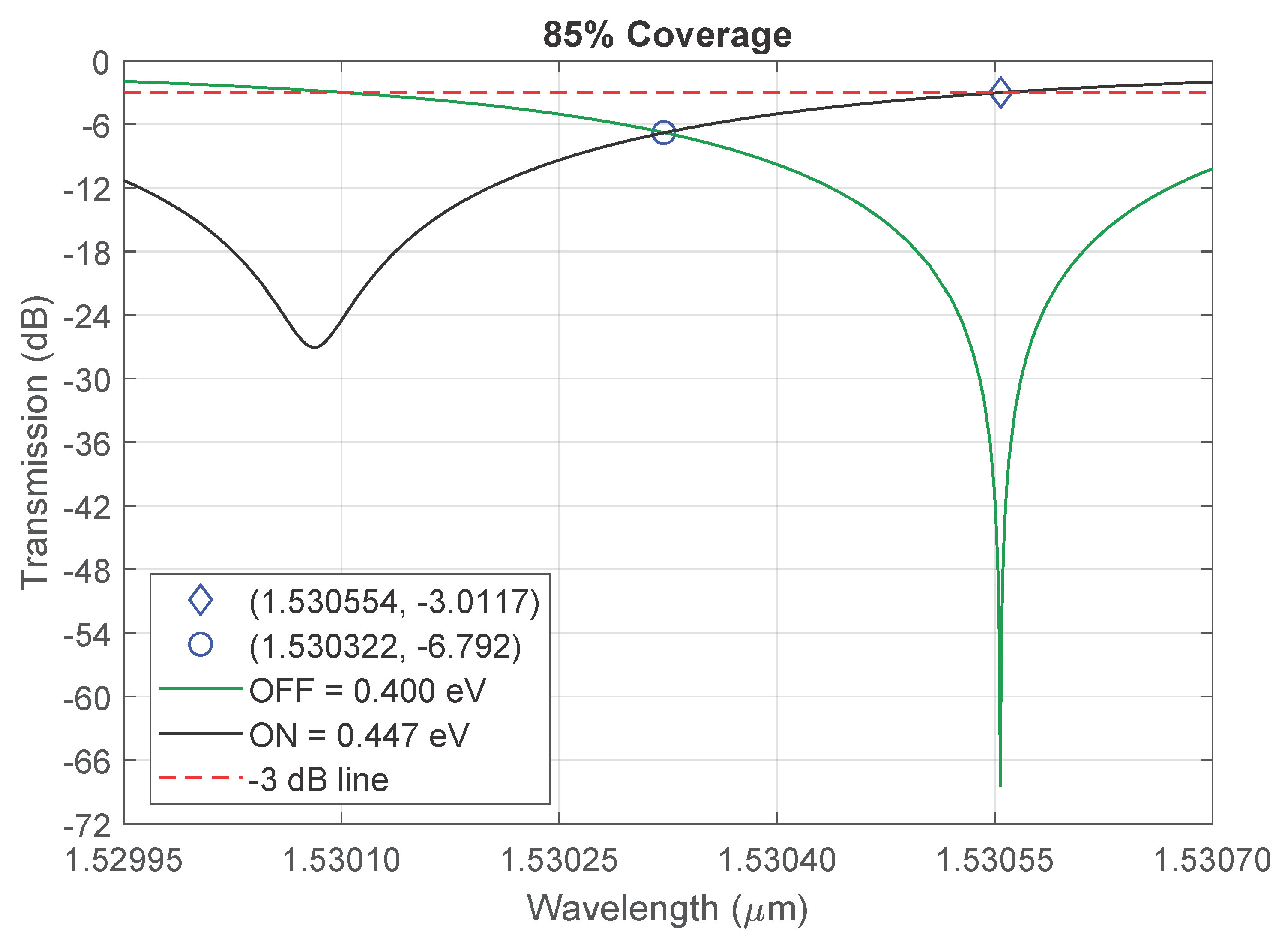

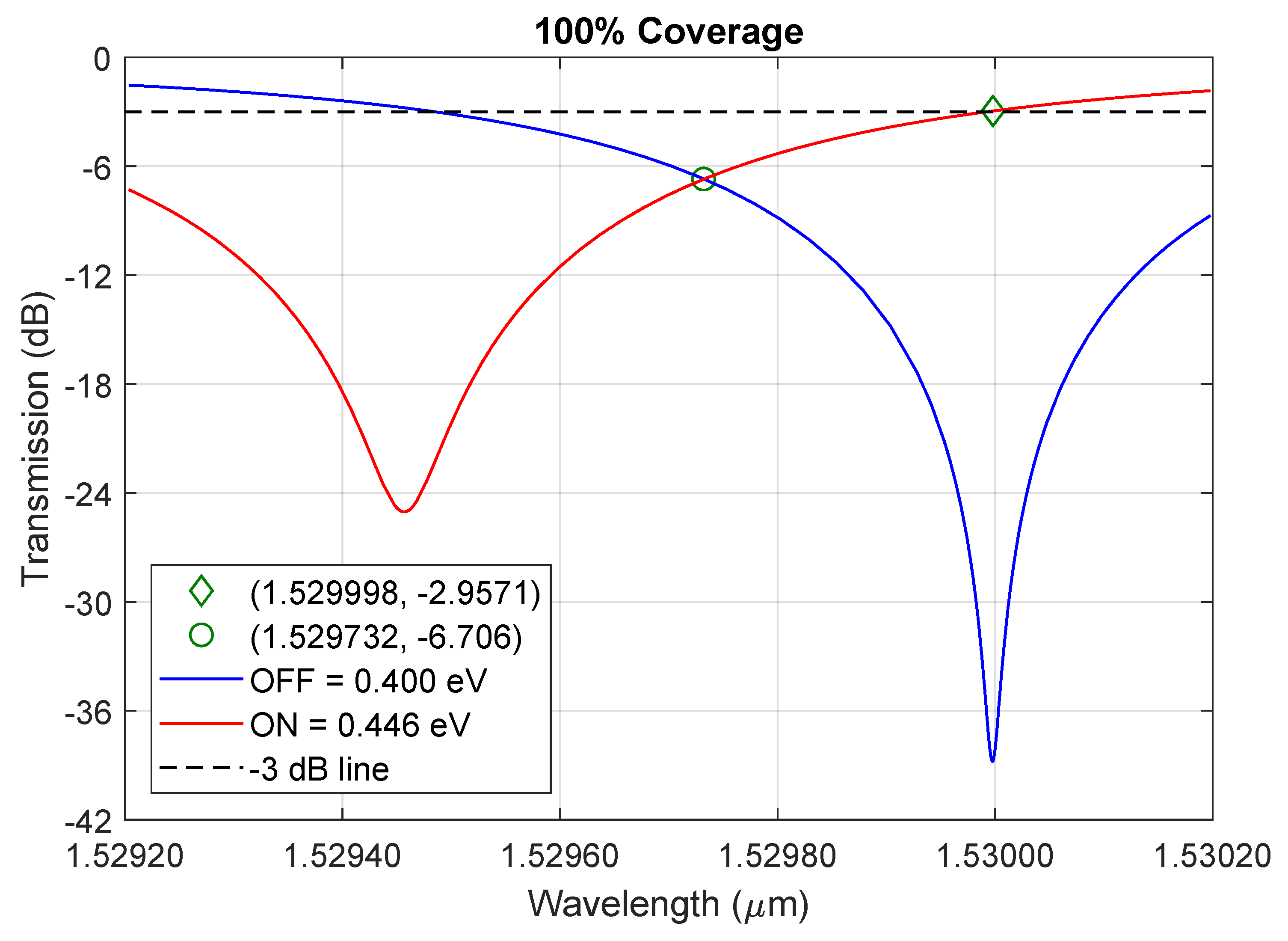

5.1. Curves of Transmission for ON/OFF States

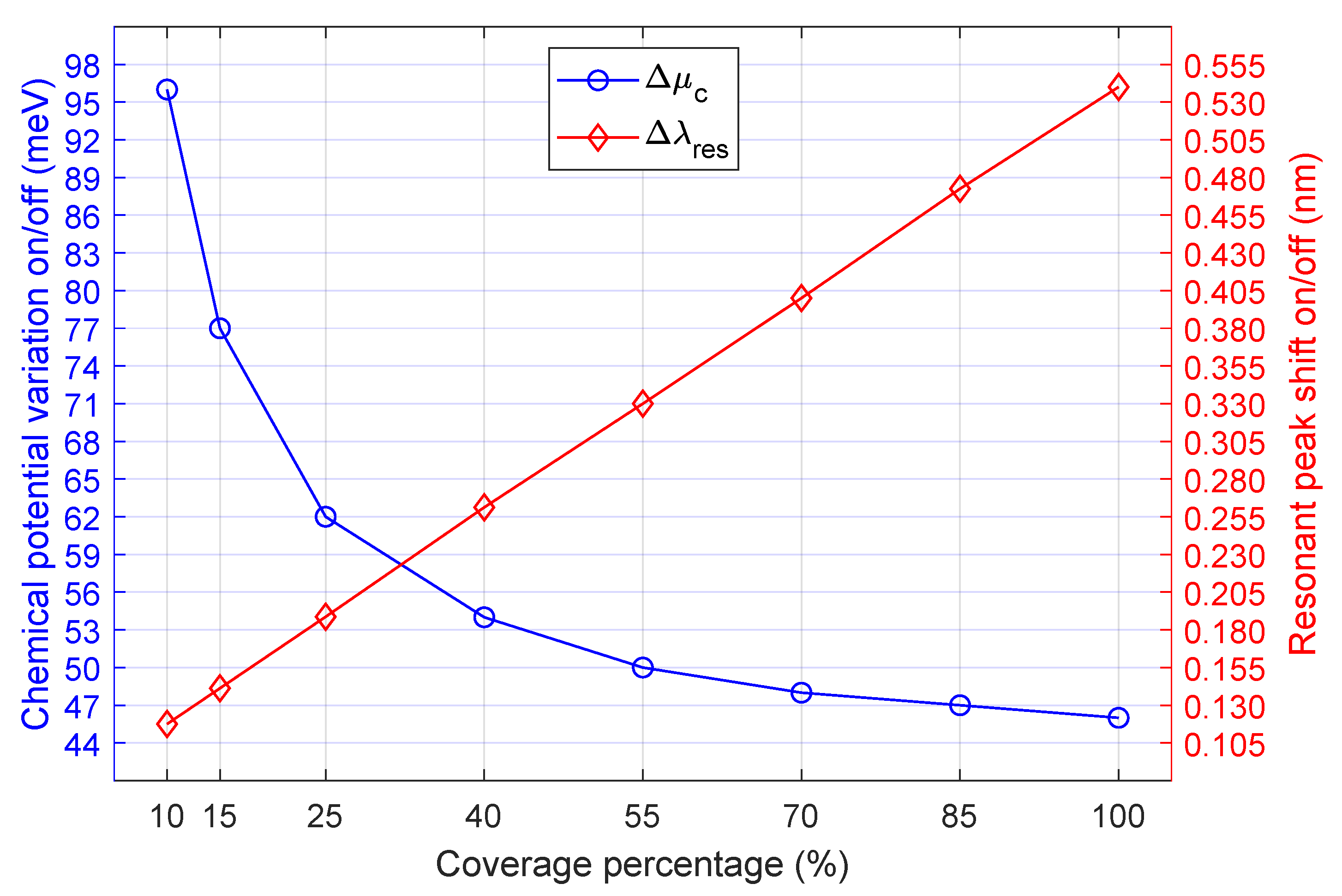

5.2. Power Consumption, Bandwidth and FOM

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardes, F.Y.; Reed, G.T.; Emerson, N.G.; Png, C.E. A submicron depletion-type photonic modulator in silicon on insulator. Opt. Express 2005, 13, 8845–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, W.M.J.; Rooks, M.J.; Sekaric, L.; Vlasov, Y.A. Ultra-compact, low RF power, 10 Gb/s silicon Mach-Zehnder modulator. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 17106–17113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, M.R.; Zortman, W.A.; Trotter, D.C.; Young, R.W.; Lentine, A.L. Low-voltage, compact, depletion mode, silicon Mach-Zehnder modulator. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2010, 16, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Akiyama, S.; Imai, M.; Usuki, T. 25-Gb/s broadband silicon modulator with 0.31-V·cm VπL based on forward-biased PIN diodes embedded with passive equalizer. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 32950–32960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, K.; Thomson, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Khokhar, A.Z.; Littlejohns, C.; Byers, J.; Mastronardi, L.M.K.; Husain, K.I.; Gardes, F.Y.; Reed, G.T.; et al. All-silicon carrier accumulation modulator based on a lateral metal-oxide-semiconductor capacitor. Photonics Res. 2018, 6, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberi, M.; Montanaro, A.; Wen, C.; Zhang, J.; Balci, O.; Shinde, S.M.; Sharma, S.; Meersha, A.; Shekhar, H.; Muench, J.E.; et al. Graphene Electro-Absorption Modulators for Energy-Efficient and High-Speed Optical Transceivers, 2025, [2506.03281].

- Neves, D.; Sanches, A.; Nobrega, R.; Mrabet, H.; Dayoub, I.; Ohno, K.; Haxha, S.; Glesk, I.; Jurado-Navas, A.; Raddo, T. Beyond 5G Fronthaul Based on FSO Using Spread Spectrum Codes and Graphene Modulators. MDPI Sensors 2023, 23, 3791–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, D.; Nobrega, R.; Sanches, A.; Navas, A.J.; Glesk, I.; Haxha, S.; Raddo, T. Power consumption analysis of an optical modulator based on different amounts of graphene. Opt. Contin. 2022, 1, 2077–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.A.D.; Neves, D.M.; Nascimento, J.C.; Sanches, A.; Santos, A.F.D.; Cordette, S.J.; Haxha, S.; Jurado-Navas, A.; Raddo, T. Ultra-Efficient Modulators Based on Chalcogenide and Graphene Materials for AI Hyperscalers. In Proceedings of the 2024 SBFoton International Optics and Photonics Conference (SBFoton IOPC). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, I.; Chae, S.H.; Bhatt, G.R.; Tadayon, M.A.; Li, B.; Yu, Y.; Park, C.; Park, J.; Cao, L.; Basov, D.N.; et al. Low-loss composite photonic platform based on 2D semiconductor monolayers. Nat. Photonics 2020, 14, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, I.; Molina, A.G.; Chae, S.H.; Zhou, V.; Hone, J.; Lipson, M. 2D material platform for overcoming the amplitude–phase tradeoff in ring resonators. Optica 2024, 11, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Shang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Guo, K.; Yang, J.; Yan, P. Heterogeneous integrated phase modulator based on two-dimensional layered materials. Photonics Res. 2022, 10, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, I.; Debnath, K.; Dixit, V. Low-energy high-speed graphene modulator for on-chip communication. OSA Contin. 2019, 2, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Shang, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, F.; Dong, B.; Guo, K.; et al. Racetrack resonator based integrated phase shifters on silicon nitride platform. Infrared Phys. Tech. 2022, 125, 104276–104280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Li, E.P.; Hao, R. Tunability Analysis of a Graphene-Embedded Ring Modulator. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2014, 26, 2008–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Hao, R.; Jin, X.F.; Zhang, X.M.; Li, E.P. A Graphene-Enhanced Fiber-Optic Phase Modulator With Large Linear Dynamic Range. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2014, 26, 1867–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Late, D.J.; Kumar, A.; Patel, S.; Singh, J. 2D layered transition metal dichalcogenides (MoS2): Synthesis, applications and theoretical aspects. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 13, 242–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, D.J. Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenides and Metal Oxide Hybrids for Gas Sensing. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2045–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Shital, S.; Yaakobovitz, A.; Niv, A. Shear strain bandgap tuning of monolayer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 223102–223106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, S.; Majumdar, A.; Ahmed, T.; Parappurath, A.; Gill, N.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Gosh, A. High-Efficiency Infrared Sensing with Optically Excited Graphene-Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Heterostructures. Small 2022, 18, 2202626–2202633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Kim, S.; Reo, Y.; Heo, S.; Liu, A.; Noh, Y. Electrical Properties of Electrochemically Exfoliated 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides Transistors for Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2024, 10, 2300691–2300698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, P.; Pang, M.; Xue, Q. Flexible self-powered high-performance ammonia sensor based on Au-decorated MoSe2 nanoflowers driven by single layer MoS2-flake piezoelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2019, 65, 103974–103981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Sohn, I.; Shin, D.; Yoo, J.; Lee, S.; Yoon, H.; Park, J.; Chung, S.; Kim, H. Recent Advances in Functionalization and Hybridization of Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenide for Gas Sensor. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2301063–2301088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Qu, S.; Dong, L. A 130 GHz Electro-Optic Ring Modulator with Double-Layer Graphene. Crystals 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, X.; Avila, E.U.; Geng, B.; Zentgraf, T.; Ju, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. A graphene-based broadband optical modulator. Nature 2011, 474, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, G.W. Dyadic Green’s functions and guided surface waves for a surface conductivity model of graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 06432–06439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosciniak, J.; Tan, D.T.H. Theoretical investigation of graphene-based photonic modulators. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chernikov, A.; Zhang, X.; Rigosi, A.; Hill, H.M.; Zande, A.M.; Chenet, D.A.; Shih, E.; Hone, J. Measurement of the optical dielectric function of monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides: MoS2, MoSe2, WS2, and WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 205442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Du, W.; Chen, H.; Jin, X.; Yang, L.; Li, E. Ultra-compact optical modulator by graphene induced electro-refraction effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 061116–061119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liang, C. The absorption ring modulator based on few-layer graphene. J. Opt. 2019, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Kim, B.; Freitas, A.P.; Mohanty, A.; Zhu, Y.; Bhatt, G.R.; Hone, J.; Lipson, M. High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature. Nanophotonics 2020, 10, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, W.; Heyn, P.D.; Vaerenbergh, T.V.; Vos, K.D.; Selvaraja, S.K.; Claes, T.; Dumon, P.; Bienstman, P.; Thourhout, D.V.; Baets, R. Silicon microring resonators. Laser Photon. Rev. 2012, 6, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midrio, M.; Boscolo, S.; Moresco, M.; Romagnoli, M.; Angelis, C.D.; Locatelli, A.; Capobianco, A.D. Graphene–assisted critically–coupled optical ring modulator. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 23144–23155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Ma, Z.; Maiti, R.; Khan, S.; Khurgin, J.B.; Dalir, H.; Sorger, V.J. Attojoule-efficient graphene optical modulators. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, D130–D140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yariv, A. Critical coupling and its control in optical waveguide–ring resonator systems. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2002, 14, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A. Optical interconnects to electronic chips. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, F59–F70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.S.; Gong, H.; Thong, J.T.L. Low-contact-resistance graphene devices with nickel-etched-graphene contacts. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, A.; Nipane, A.; Choi, M.S.; Hone, J.; Teherani, J.T. Low-Resistance p-Type Ohmic Contacts to Ultrathin WSe2 by Using a Monolayer Dopant. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 2941–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Huang, Y.; Xia, F.; Wang, L.; Ning, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Q.; et al. 5 nm Nanogap Electrodes and Arrays by Super-resolution Laser Lithography. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 4916–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Hoff, B.H.; Maier, S.A.; de Mello, J.C. Scalable Fabrication of Metallic Nanogaps at the Sub-10 nm Level. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2102756–2102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (%) | FWHM (GHz) | FSR (nm) | ER (dB) | (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 28.20 | 44.910 | 52.82 | 745 | 0.9923 |

| 15 | 34.25 | 44.900 | 78.05 | 727 | 0.9907 |

| 25 | 46.10 | 44.880 | 55.53 | 700 | 0.9874 |

| 40 | 64.05 | 44.852 | 54.04 | 670 | 0.9826 |

| 55 | 81.01 | 44.824 | 48.19 | 649 | 0.9780 |

| 70 | 98.80 | 44.796 | 45.18 | 632 | 0.9733 |

| 85 | 116.2 | 44.769 | 65.41 | 617 | 0.9686 |

| 100 | 131.6 | 44.740 | 35.83 | 607 | 0.9646 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).